Where is the pelvic located

Anatomy, Function of Bones, Muscles, Ligaments

What is the female pelvis?

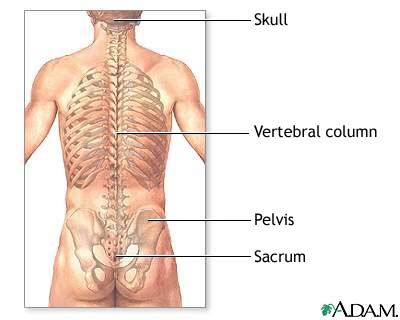

The pelvis is the lower part of the torso. It’s located between the abdomen and the legs. This area provides support for the intestines and also contains the bladder and reproductive organs.

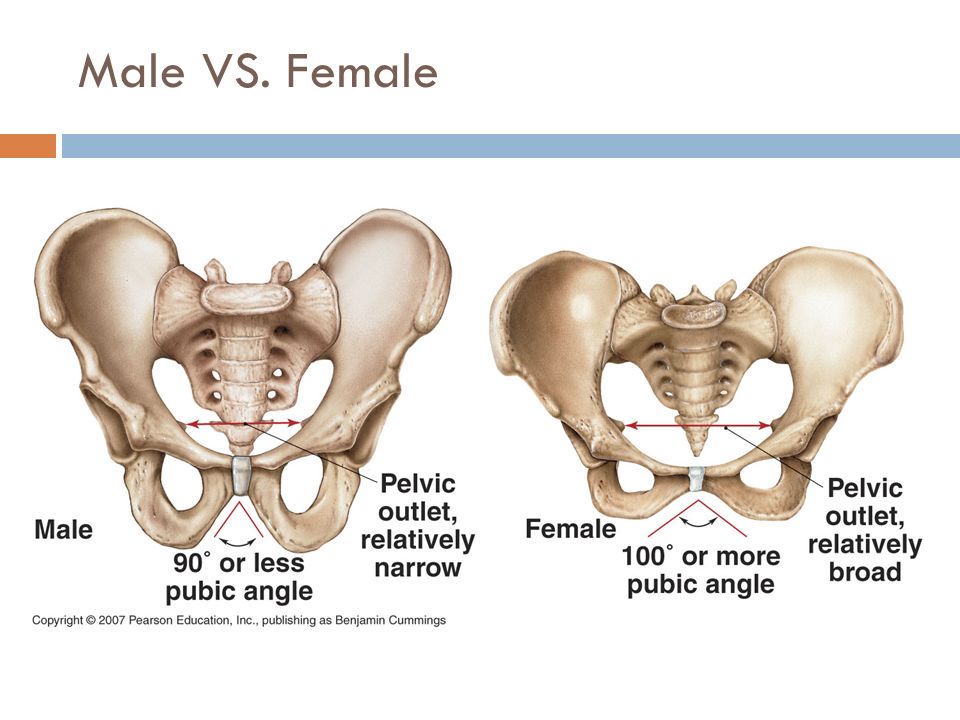

There are some structural differences between the female and the male pelvis. Most of these differences involve providing enough space for a baby to develop and pass through the birth canal of the female pelvis. As a result, the female pelvis is generally broader and wider than the male pelvis.

Below, learn more about the bones, muscles, and organs of the female pelvis.

Female pelvis anatomy and function

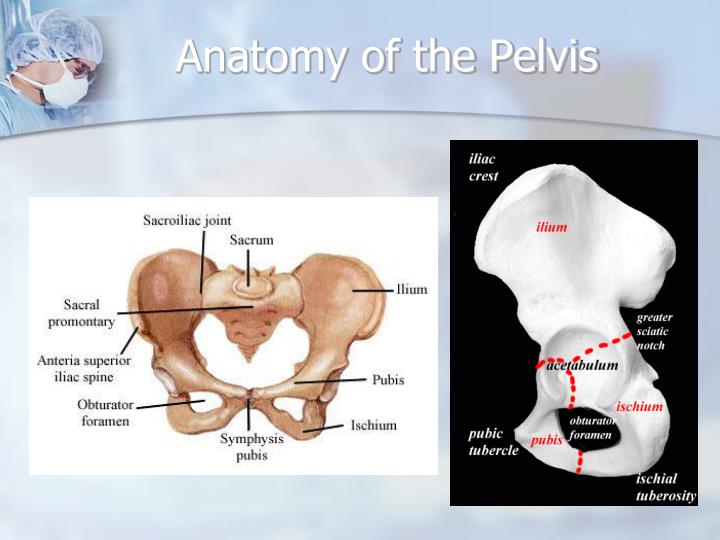

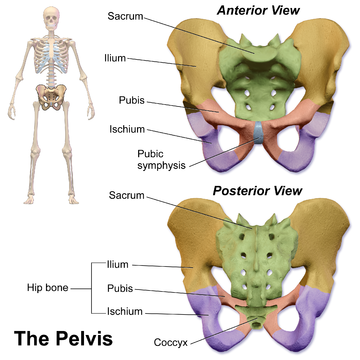

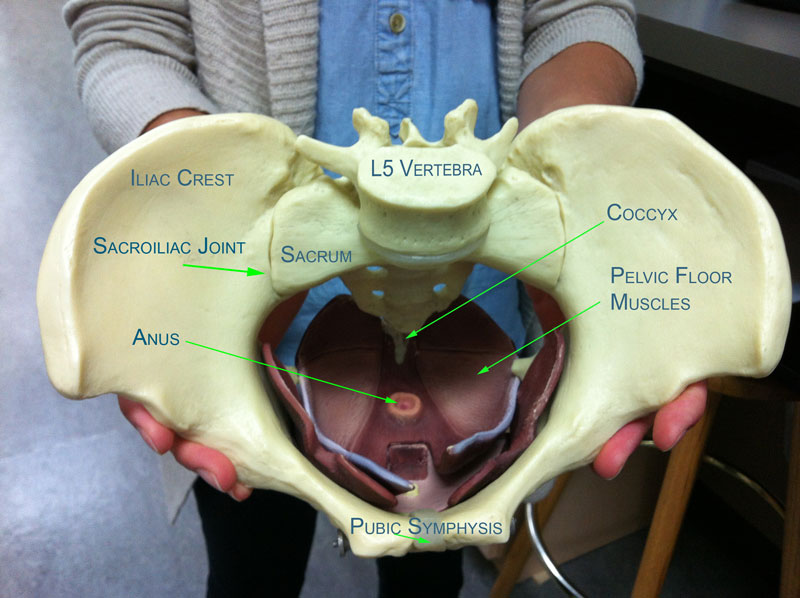

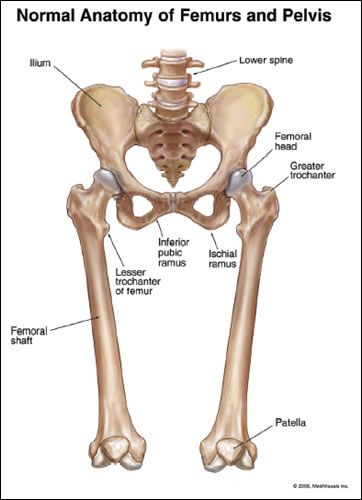

Female pelvis bones

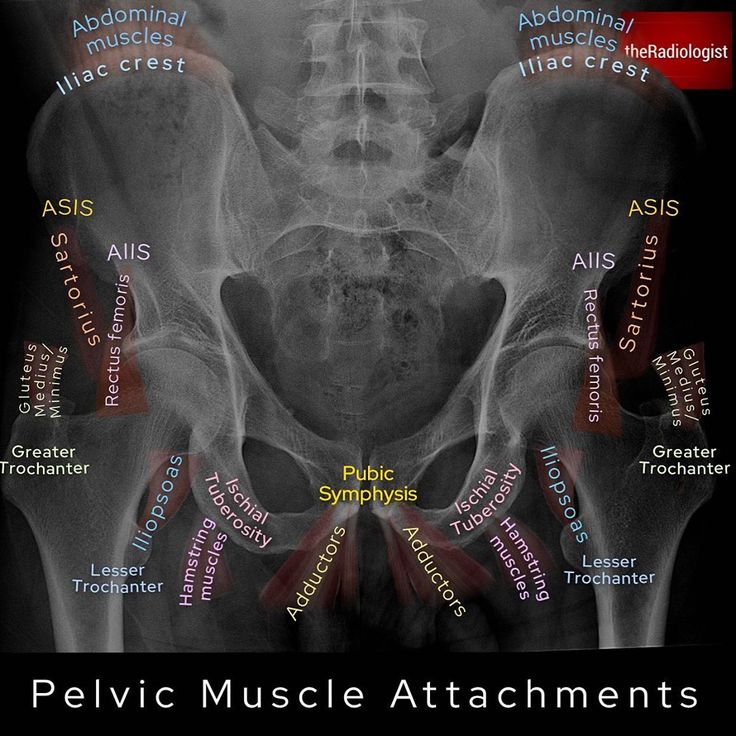

Hip bones

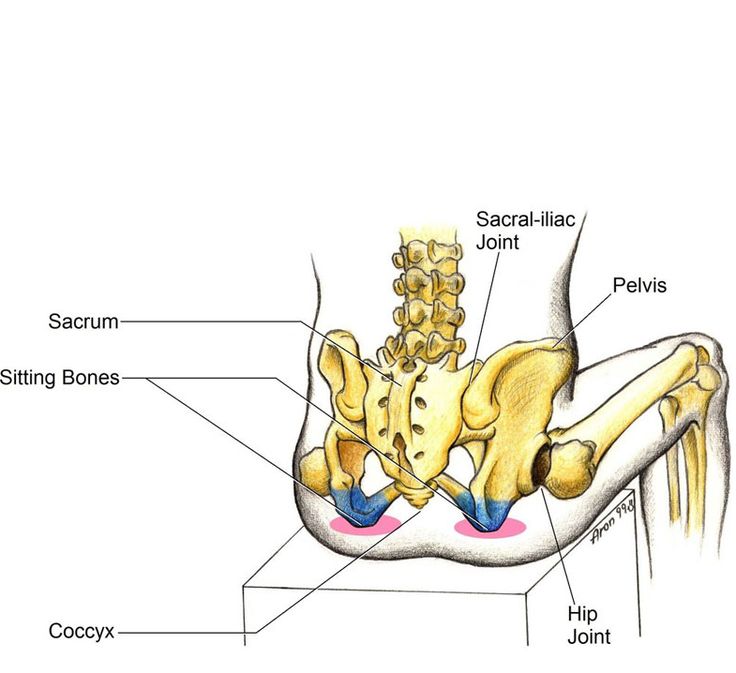

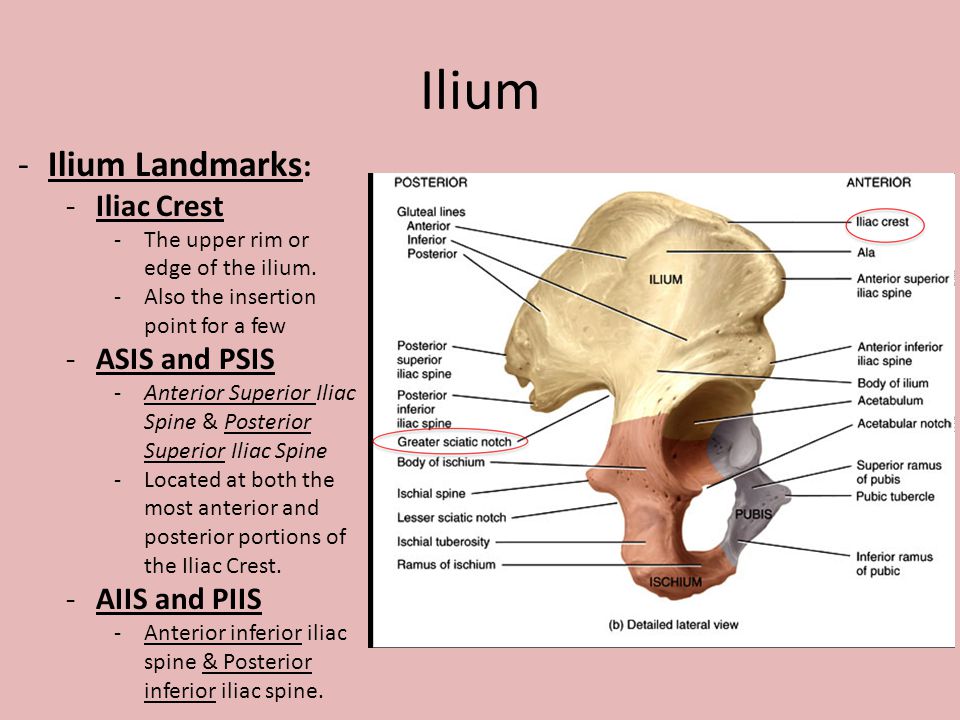

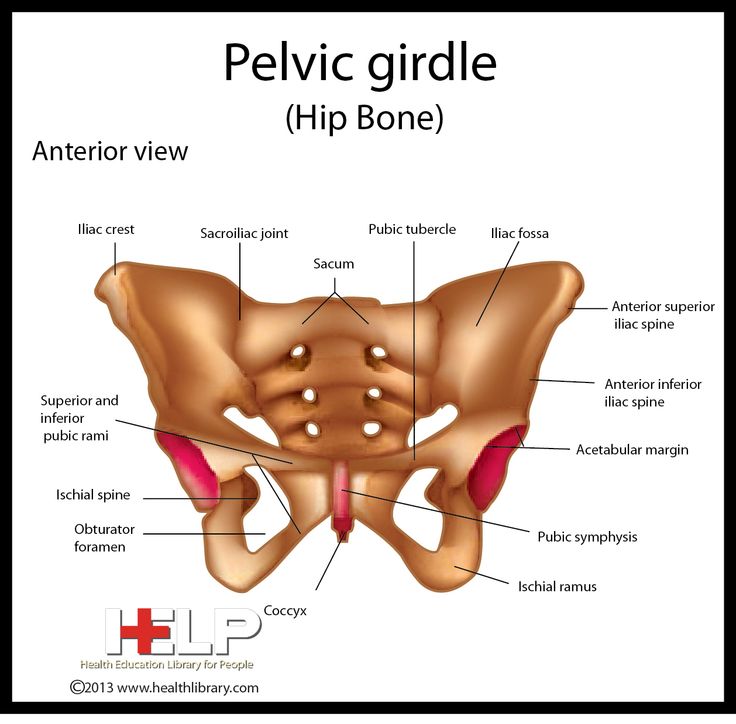

There are two hip bones, one on the left side of the body and the other on the right. Together, they form the part of the pelvis called the pelvic girdle.

The hip bones join to the upper part of the skeleton through attachment at the sacrum. Each hip bone is made of three smaller bones that fuse together during adolescence:

- Ilium. The largest part of the hip bone, the ilium, is broad and fan-shaped. You can feel the arches of these bones when you put your hands on your hips.

- Pubis. The pubis bone of each hip bone connects to the other at a joint called the pubis symphysis.

- Ischium. When you sit down, most of your body weight falls on these bones. This is why they’re sometimes called sit bones.

The ilium, pubis, and ischium of each hip bone come together to form the acetabulum, where the head of the thigh bone (femur) attaches.

Sacrum

The sacrum is connected to the lower part of the vertebrae. It’s actually made up of five vertebrae that have fused together. The sacrum is quite thick and helps to support body weight.

Coccyx

The coccyx is sometimes called the tailbone. It’s connected to the bottom of the sacrum supported by several ligaments.

The coccyx is made up of four vertebrae that have fused into a triangle-like shape.

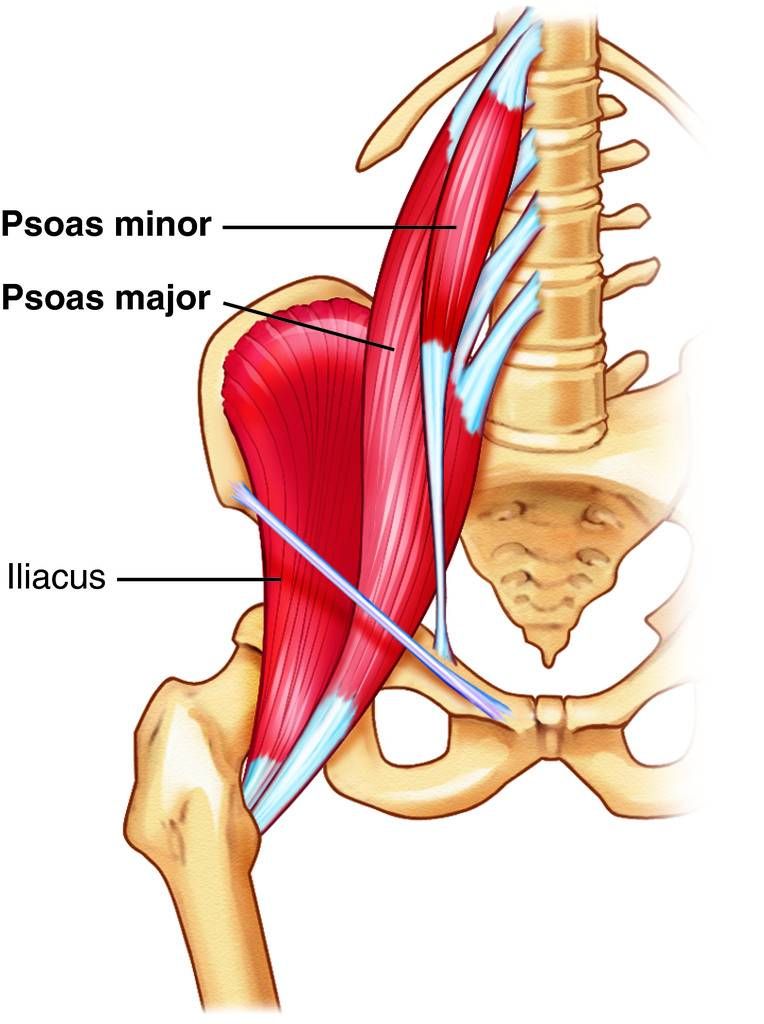

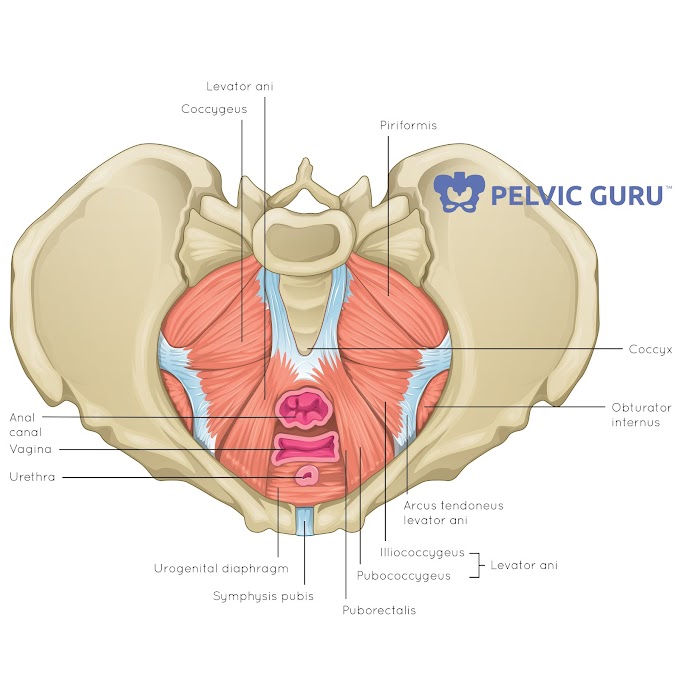

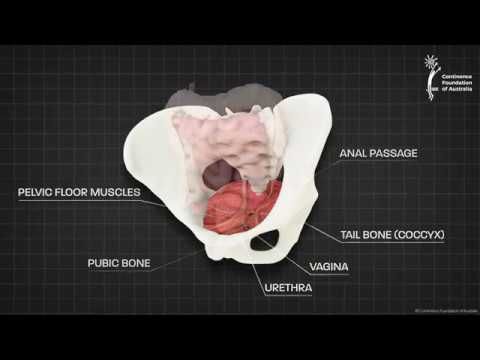

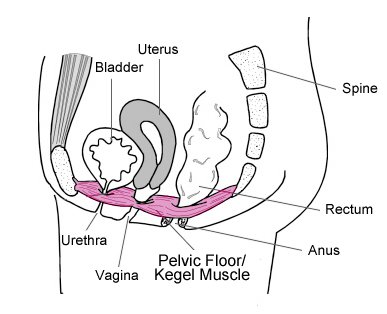

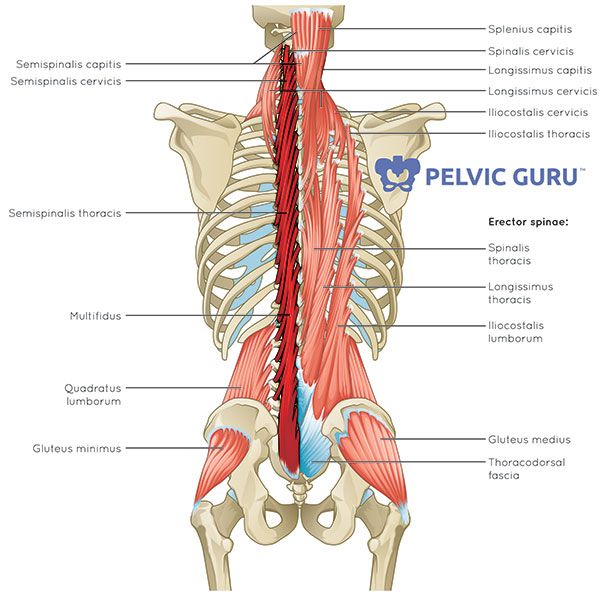

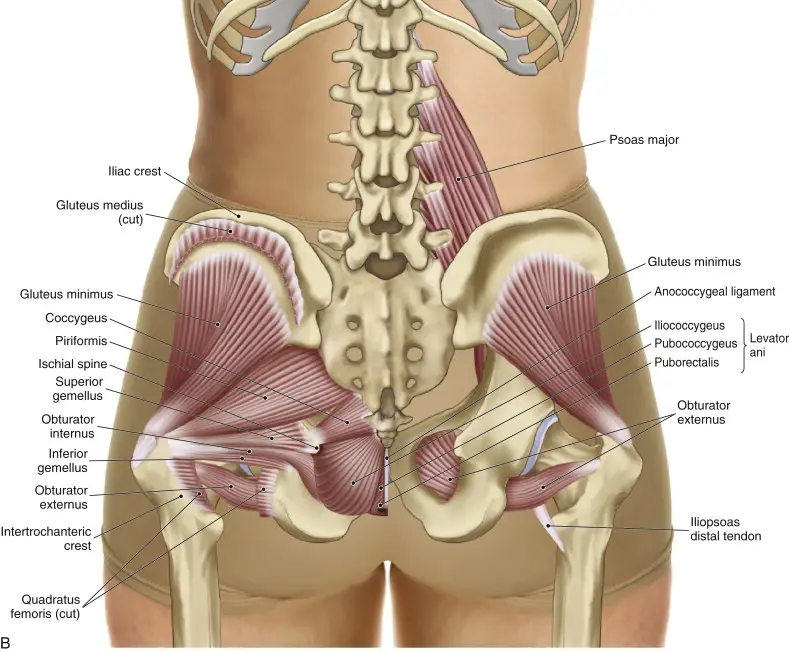

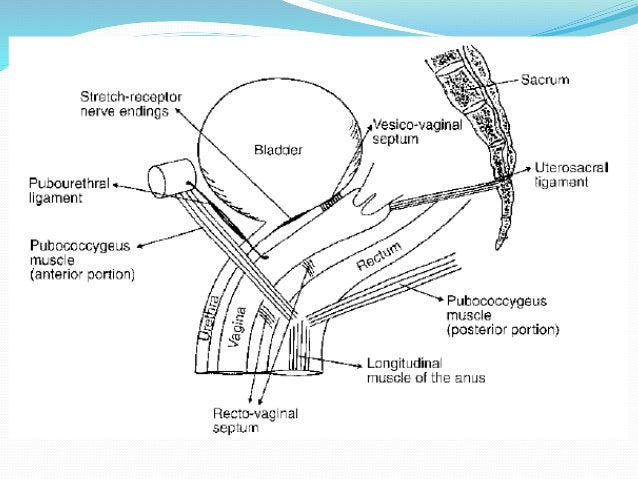

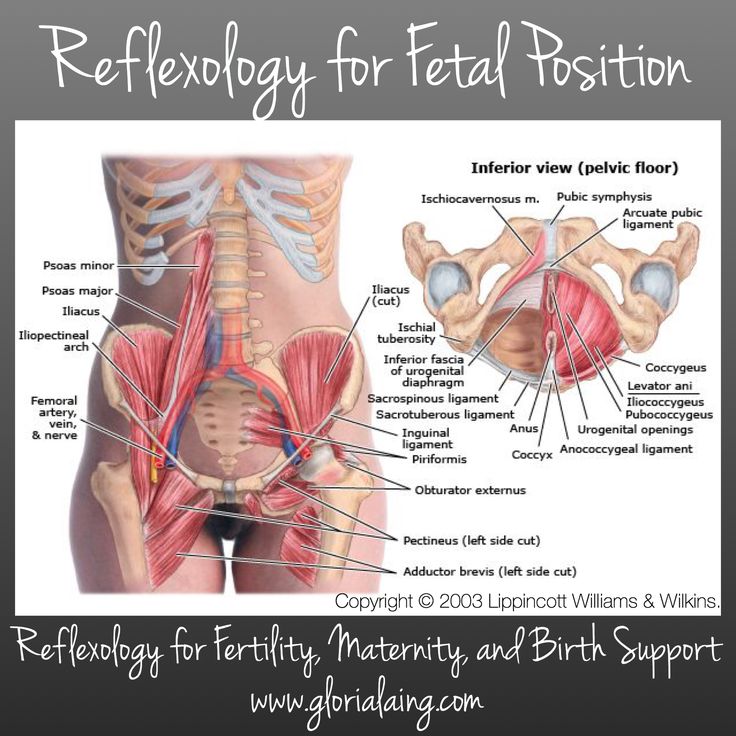

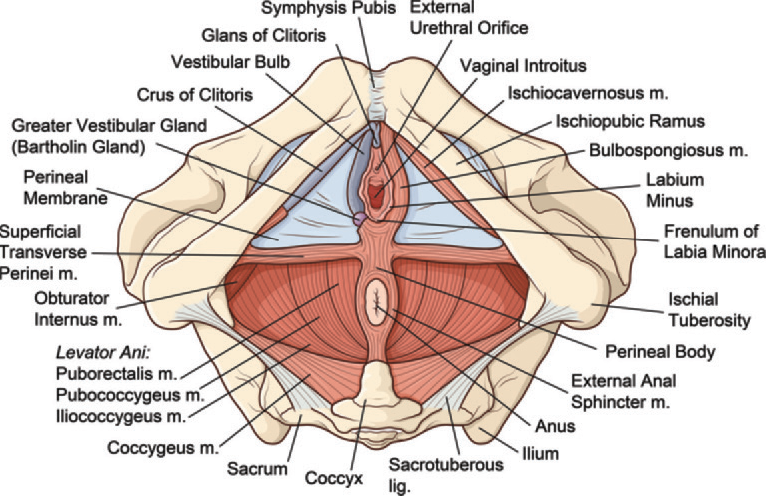

Female pelvis muscles

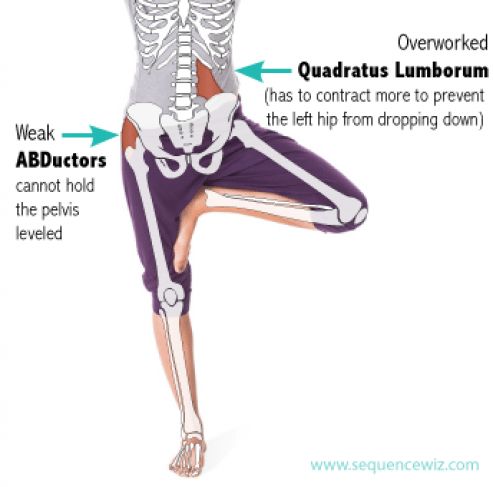

Levator ani muscles

The levator ani muscles are the largest group of muscles in the pelvis. They have several functions, including helping to support the pelvic organs.

The levator ani muscles consist of three separate muscles:

- Puborectalis. This muscle is responsible for holding in urine and feces. It relaxes when you urinate or have a bowel movement.

- Pubococcygeus. This muscle makes up most of the levator ani muscles. It originates at the pubis bone and connects to the coccyx.

- Iliococcygeus. The iliococcygeus has thinner fibers and serves to lift the pelvic floor as well as the anal canal.

Coccygeus

This small pelvic floor muscle originates at the ischium and connects to the sacrum and coccyx.

Female pelvis organs

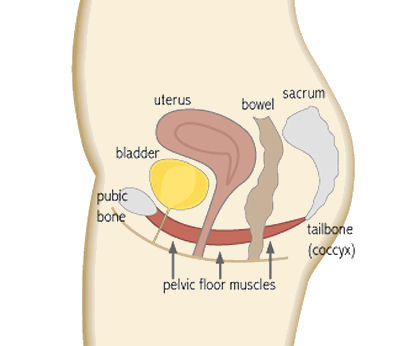

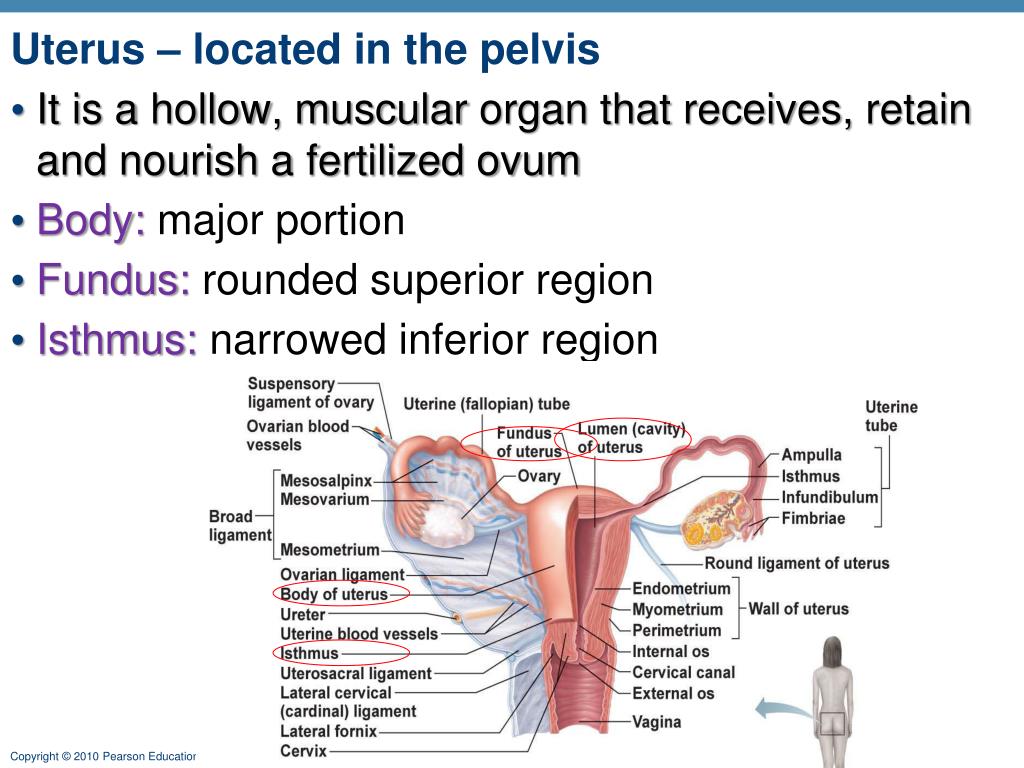

Uterus

The uterus is a thick-walled, hollow organ where a baby develops during pregnancy.

During the reproductive years, the lining of the uterus sheds every month during menstruation if you don’t become pregnant.

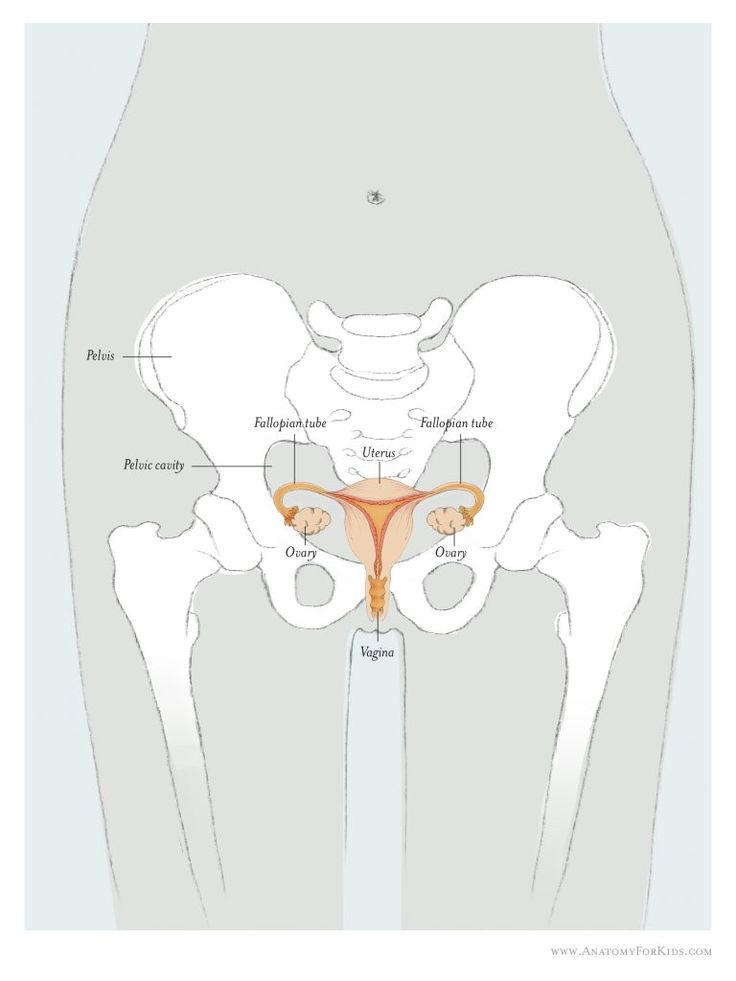

Ovaries

There are two ovaries located on either side of the uterus. The ovaries produce eggs and also release hormones, such estrogen and progesterone.

Fallopian tubes

The fallopian tubes connect each ovary to the uterus. Specialized cells in the fallopian tubes use hair-like structures called cilia to help direct eggs from the ovaries toward the uterus.

Cervix

The cervix connects the uterus to the vagina. It’s able to widen, allowing sperm to pass into the uterus.

In addition, thick mucus produced in the cervix can help to prevent bacteria from reaching the uterus.

Vagina

The vagina connects the cervix to the exterior female genitalia. It’s also called the birth canal, as the baby passes through the vagina during delivery.

Rectum

The rectum is the lowest part of the large intestine. Feces collects here until exiting through the anus.

Feces collects here until exiting through the anus.

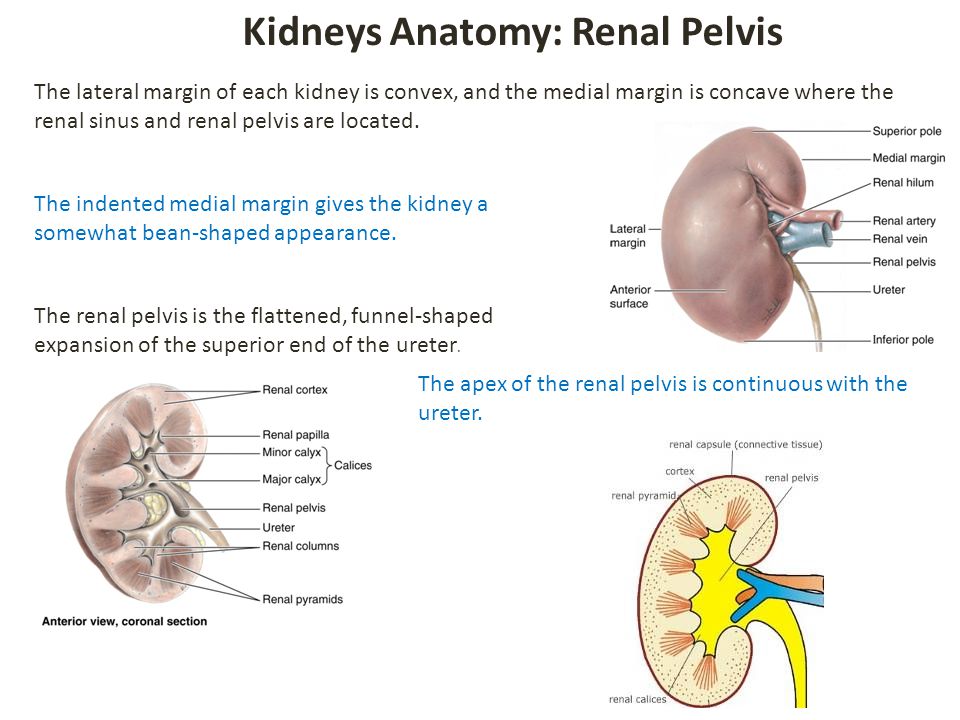

Bladder

The bladder is the organ that collects and stores urine until it’s released. Urine reaches the bladder through tubes called ureters that connect to the kidneys.

Urethra

The urethra is the tube that urine travels through to exit the body from the bladder. The female urethra is much shorter than the male urethra.

Female pelvis ligaments

Broad ligament

The broad ligament supports the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. It extends to both sides of the pelvic wall.

The broad ligament can be further divided into three components that are linked to different parts of the female reproductive organs:

- mesometrium, which supports the uterus

- mesovarium, which supports the ovaries

- mesosalpinx, which supports the fallopian tubes

Uterine ligaments

Uterine ligaments provide additional support for the uterus. Some of the main uterine ligaments include:

Some of the main uterine ligaments include:

- the round ligament

- cardinal ligaments

- pubocervical ligaments

- uterosacral ligaments

Ovarian ligaments

The ovarian ligaments support the ovaries. There are two main ovarian ligaments:

- the ovarian ligament

- the suspensory ligament of the ovary

Female pelvis diagram

Explore this interactive 3-D diagram to learn more about the female pelvis:

Female pelvis conditions

The pelvis contains a large number of organs, bones, muscles, and ligaments, so many conditions can affect the entire pelvis or parts within it.

Some conditions that can affect the female pelvis as a whole include:

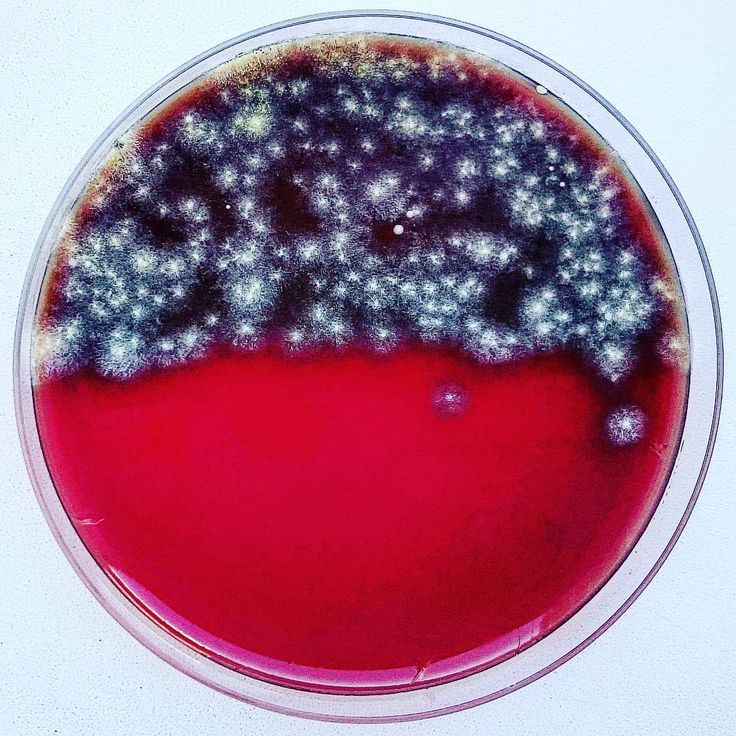

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID is an infection that occurs in the female reproductive system. While it’s often caused by a sexually transmitted infection, other infections can also cause PID. Untreated PID can lead to complications, such as infertility or ectopic pregnancy.

- Pelvic organ prolapse. Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when the muscles in the pelvis can no longer support its organs, such as the bladder, uterus, or rectum. This can cause one or more of these organs to press down on the vagina. In some cases, this can cause a bulge to form outside of the vagina.

- Endometriosis. Endometriosis occurs when the tissue that lines the inside walls of the uterus (endometrium) begins to grow outside of the uterus. The ovaries, fallopian tubes, and other tissues in the pelvis are typically affected by the condition. Endometriosis can lead to complications, including infertility or ovarian cancer.

Symptoms of a pelvic condition

Some common symptoms of a pelvic condition can include:

- pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis

- a feeling of pressure or fullness in the pelvis

- unusual or foul-smelling vaginal discharge

- pain during sex

- bleeding in between periods

- painful cramping during or before periods

- pain during bowel movements or when urinating

- a burning feeling when urinating

Tips for a healthy pelvis

The female pelvis is a complex, important part of the body. Follow these tips to keep it in good health:

Follow these tips to keep it in good health:

Stay on top of your reproductive health

See a gynecologist for a yearly health screen. Things like pelvic exams and Pap smears can aid in identifying pelvic conditions or infections early.

You can get a free or low-cost pelvic exam at your local Planned Parenthood clinic.

Practice safe sex

Use barriers — such as condoms or dental dams — during sexual activity, especially with a new partner, to avoid infections that could lead to PID.

Try pelvic floor exercises

These types of exercises can help to strengthen the muscles in the pelvis, including those around the bladder and vagina.

Stronger pelvic floor muscles can aid in preventing things like incontinence or organ prolapse. Here’s how to get started.

Never ignore unusual symptoms

If you’re experiencing anything unusual in your pelvic area, such as bleeding between periods or unexplained pelvic pain, make an appointment with your doctor. Left untreated, some pelvic conditions can have lasting impacts on your health and fertility.

Left untreated, some pelvic conditions can have lasting impacts on your health and fertility.

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Female Pelvic Cavity - StatPearls

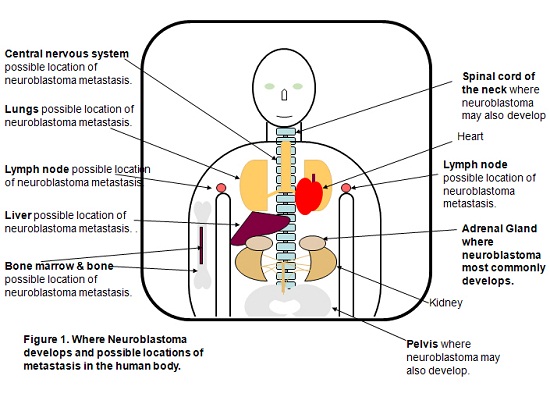

Introduction

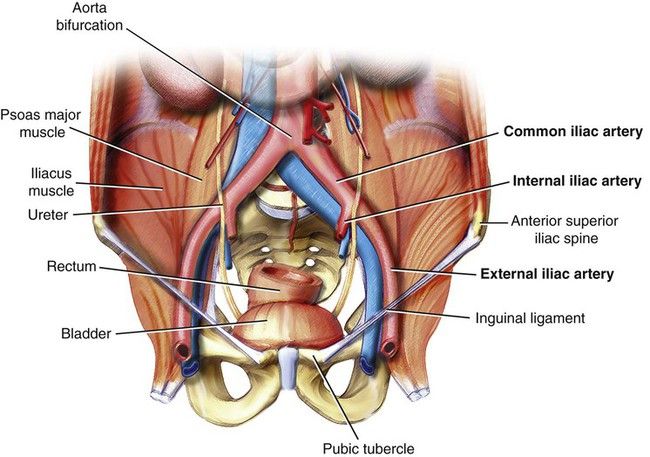

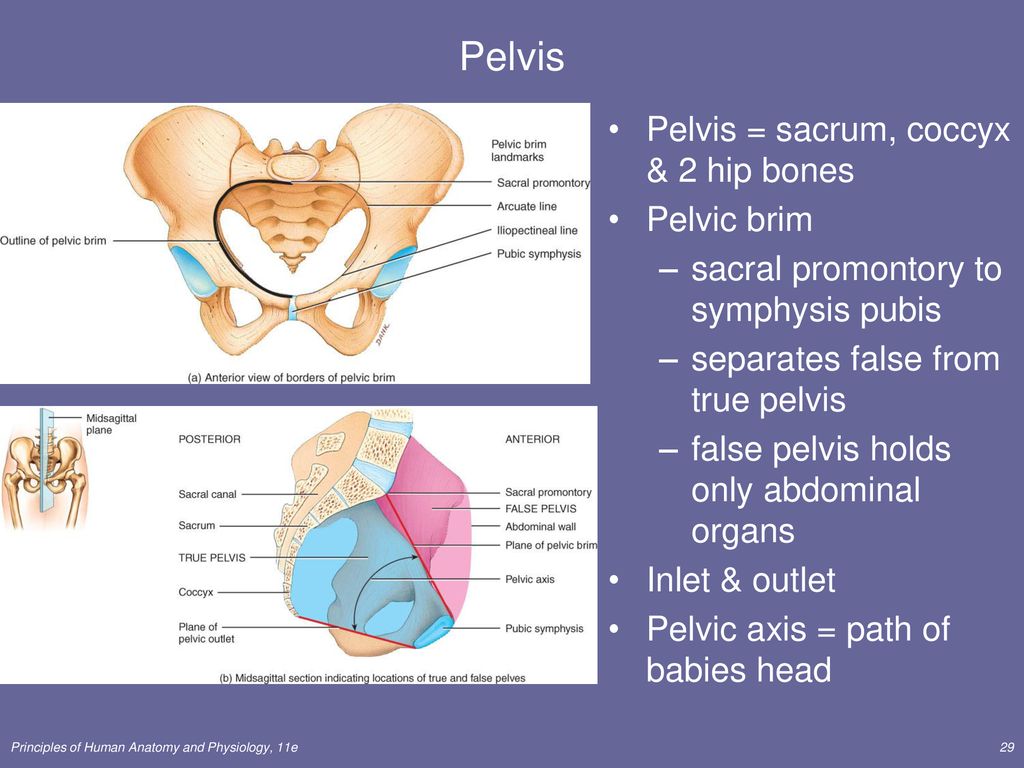

The pelvic cavity is a bowl-like structure that sits below the abdominal cavity. The true pelvis, or lesser pelvis, lies below the pelvic brim (Figure 1). This landmark begins at the level of the sacral promontory posteriorly and the pubic symphysis anteriorly. The space below contains the bladder, rectum, and part of the descending colon. In females, the pelvis also houses the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. Knowledge of anatomy unique to females is essential for all clinicians, especially those in the field of obstetrics and gynecology.

Structure and Function

The uterus sits in the center of the female pelvic cavity (Figure 2.) The most common position of the uterus in the pelvic cavity is anteverted and anteflexed.[1] "Version" refers to the angle between the cervix and the vagina. An anteverted uterus appears "tipped forward" in the pelvic cavity. A retroverted uterus is "tipped backward." Retroversion is a normal variant but can lead to dyspareunia. Additionally, retroversion of a gravid uterus correlates with higher rates of vaginal bleeding and spontaneous abortion.[2]

An anteverted uterus appears "tipped forward" in the pelvic cavity. A retroverted uterus is "tipped backward." Retroversion is a normal variant but can lead to dyspareunia. Additionally, retroversion of a gravid uterus correlates with higher rates of vaginal bleeding and spontaneous abortion.[2]

"Flexion" is the term for the angle between the cervix and uterine body. Anteflexed means the uterus is bent forward. Retroflexed means the uterus bends backward. Occasionally, retroflexion is seen after cesarean section and may be due to scar tissue that attaches the uterine body to the abdominal wall, causing the fundus to bend posteriorly.[3] However, the data supporting this theory is limited.

Anterior to the uterus is the bladder, with rectum located posteriorly. Between the uterus and the rectum is the recto-uterine space, also known as the posterior cul-de-sac. It is a potential space prone to fluid collection. Small amounts of physiologic fluid accumulate during ovulation and menses. Pathologic causes of fluid collection in the recto-uterine pouch include pelvic abscesses, drop metastasis from gastrointestinal malignancies, and endometriosis. In certain situations, if fluid accumulation is severe, this space can be drained by performing a culdocentesis, which is accomplished by inserting a needle through the posterior fornix of the upper vagina to access the posterior cul-de-sac.

Pathologic causes of fluid collection in the recto-uterine pouch include pelvic abscesses, drop metastasis from gastrointestinal malignancies, and endometriosis. In certain situations, if fluid accumulation is severe, this space can be drained by performing a culdocentesis, which is accomplished by inserting a needle through the posterior fornix of the upper vagina to access the posterior cul-de-sac.

The posterior cul-de-sac communicates with the retroperitoneal space of the abdomen via the right and left epiploic gutters. The right gutter leads to the hepatorenal space, also known as Morrison's pouch. The right epiploic gutter also allows the spread of pelvic pathogens into the subphrenic space. Occasionally infection of the subphrenic space can occur, leading to adhesions on the capsule of the liver. This pathology is known as Fitz-Curtis-Hugh syndrome or gonococcal perihepatitis.

The left epiploic gutter leads to the splenorenal pouch. Due to the leftward position of the rectum, pelvic pathology is less likely to spread to the abdomen via the left epiploic communication. [4]

[4]

Embryology

The organs of the female reproductive tract each have a unique embryological origin. The exact embryological timeline in which these organs develop is still open to debate because most embryologic studies use animal models with different gestational ages. However, there is a consensus that the ovaries are the first to develop. They arise from the surface of the mesonephros at the gonadal ridge.[5] Later in development, the ovaries descend into the pelvis with guidance from the gubernaculum. The inferior aspect of the gubernaculum subsequently becomes the round ligament of the uterus and terminates at the labia majora.

In females, the absence of a Y chromosome allows the uterus to form. It derives from the Müllerian ducts, also known as the paramesonephric ducts. These ducts fuse to form the uterus, fallopian tubes, and cervix. Some studies suggest that the paramesonephric ducts also give rise to the upper vagina while other studies indicate that the vagina exclusively derives from the urogenital sinus epithelium. [6] In males, a substance coded for on the Y chromosome, known as the anti-Mullerian hormone, prevents the formation of internal female reproductive organs.

[6] In males, a substance coded for on the Y chromosome, known as the anti-Mullerian hormone, prevents the formation of internal female reproductive organs.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial

The anterior branch of the internal iliac artery supplies most of the female reproductive organs. The uterine artery supplies the majority of the uterus (Figure 3). The lower uterine segment has a dual blood supply that includes branches of the vaginal artery. The ovaries are an exception because they receive blood from the ovarian arteries, which descend from the abdominal aorta.

The superior vesicle artery supplies the upper bladder. In females, the vaginal artery supplies the lower bladder. Both arteries are also branches of the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery.

The rectum receives vascular supply via three vessels. The superior rectal artery is the terminal branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. The middle rectal is a branch of the internal iliac artery. The inferior rectal is a branch of the pudendal artery.

The inferior rectal is a branch of the pudendal artery.

Venous

The venous supply of pelvic organs follows the arterial supply. The uterine vein receives blood from the uterus and drains into the internal iliac vein. The ovarian veins receive blood from the ovaries. The right ovarian vein drains its contents directly into the inferior vena cava, while the left ovarian vein drainage is into the left renal vein. The increased length of the left ovarian vein makes it more susceptible to compression, especially during pregnancy.[7] Ovarian vein compression can lead to pelvic venous compression syndrome. The resulting pelvic vasculature congestion is a cause of chronic pelvic pain and may occur in non-pregnant patients as well.

The left-sided venous supply is also unique because the left internal iliac artery travels from its right-sided origin at the inferior vena cava towards a leftward destination in the pelvis. The longer path makes the left internal iliac more prone to compression and may explain why venous thromboembolism in pregnancy most commonly occur in the left iliac and iliofemoral veins. [8] Additionally, the leftward position of the sigmoid colon causes a gravid uterus to tip toward the right, which is thought to increase the risk of iliac vessel compression further.

[8] Additionally, the leftward position of the sigmoid colon causes a gravid uterus to tip toward the right, which is thought to increase the risk of iliac vessel compression further.

Lymphatics

The lymphatic network of the pelvis is complex but is essential to understand when staging and treating gynecologic malignancies. Generally, the pelvic organs drain into the internal and external iliac lymph nodes (Figure 5).

The lymphatic drainage of the uterus is more complicated and remains somewhat ambiguous.[9] Some researchers suggest it may involve pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes.[10] A more recent study from 2017 suggests that the uterus has two primary routes of lymphatic drainage, an upper pathway that drains to the external iliac and/or obturator lymph nodes and a lower pathway that drains to the internal iliac and/or presacral lymph nodes.[11]

The ovaries are an exception to the other female pelvic organs because they do not drain to pelvic lymph nodes. Their lymphatic drainage follows their blood supply; therefore they drain directly to the paraaortic lymph nodes.

Their lymphatic drainage follows their blood supply; therefore they drain directly to the paraaortic lymph nodes.

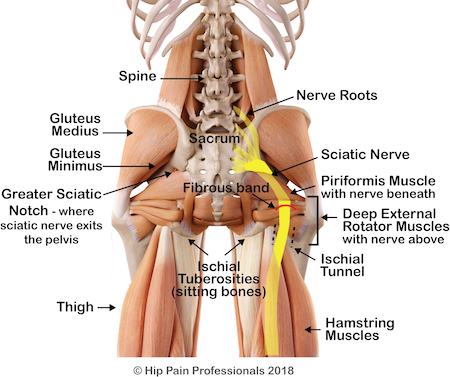

Nerves

The female reproductive organs have both autonomic and sensory innervation. Beginning with the autonomic nervous system, sympathetic fibers exit at the level of T10 to L2 to form the superior hypogastric plexus, which divides into the left and right hypogastric nerve at approximately the level of the sacral promontory. The parasympathetic nerve fibers exit at the level of S2 to 4 and meet up with the sympathetic nervous system at the right and left hypogastric nerves. The right and left hypogastric nerves then migrate inferiorly to form the inferior hypogastric plexus. After this point, the nerve fibers follow blood vessels to their target organs. The inferior hypogastric plexus also receives sensory information from the uterus.

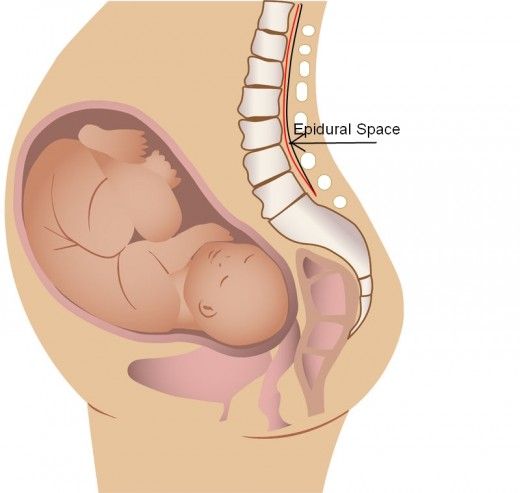

The ovarian nerve innervates the ovary. Although previously thought only to contain sensory fibers, recent animal studies suggest this nerve also carries autonomic fibers that may play a role in hormone secretion and constriction of ovarian vessels. [12][13][14] Recent studies suggest that the cervix and upper vagina also have autonomic innervation; however, the role of autonomic innervation in this region remains unclear.[15][16] Sensory innervation to the cervix and upper vagina has been more widely studied and receives supply by the pelvic splanchnic nerves. The pudendal nerve supplies the sensory innervation of the lower vagina. Pudendal nerve blocks can be used to provide local pain relief to laboring women by using the ischial spines as landmarks. Although once the treatment of choice for labor pain, it is no longer commonly used due to the widespread use of epidural anesthesia.[17]

[12][13][14] Recent studies suggest that the cervix and upper vagina also have autonomic innervation; however, the role of autonomic innervation in this region remains unclear.[15][16] Sensory innervation to the cervix and upper vagina has been more widely studied and receives supply by the pelvic splanchnic nerves. The pudendal nerve supplies the sensory innervation of the lower vagina. Pudendal nerve blocks can be used to provide local pain relief to laboring women by using the ischial spines as landmarks. Although once the treatment of choice for labor pain, it is no longer commonly used due to the widespread use of epidural anesthesia.[17]

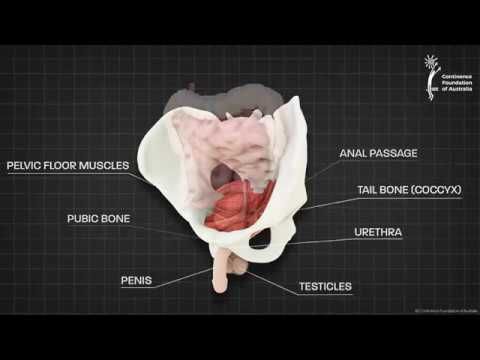

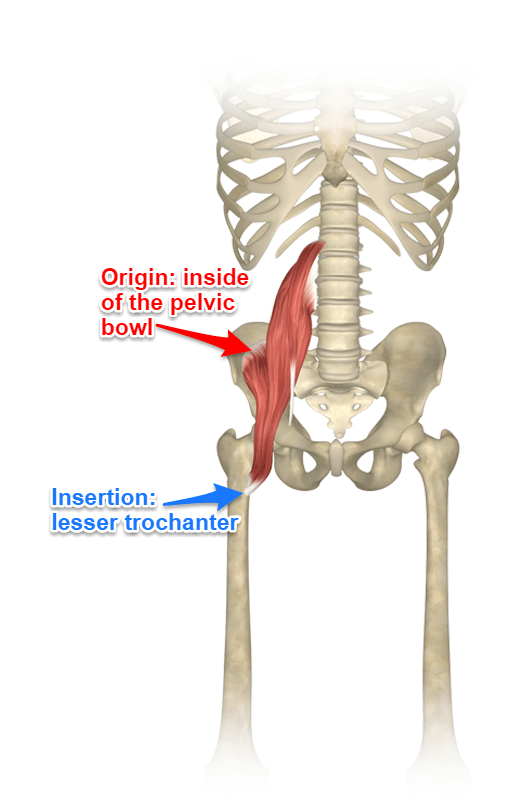

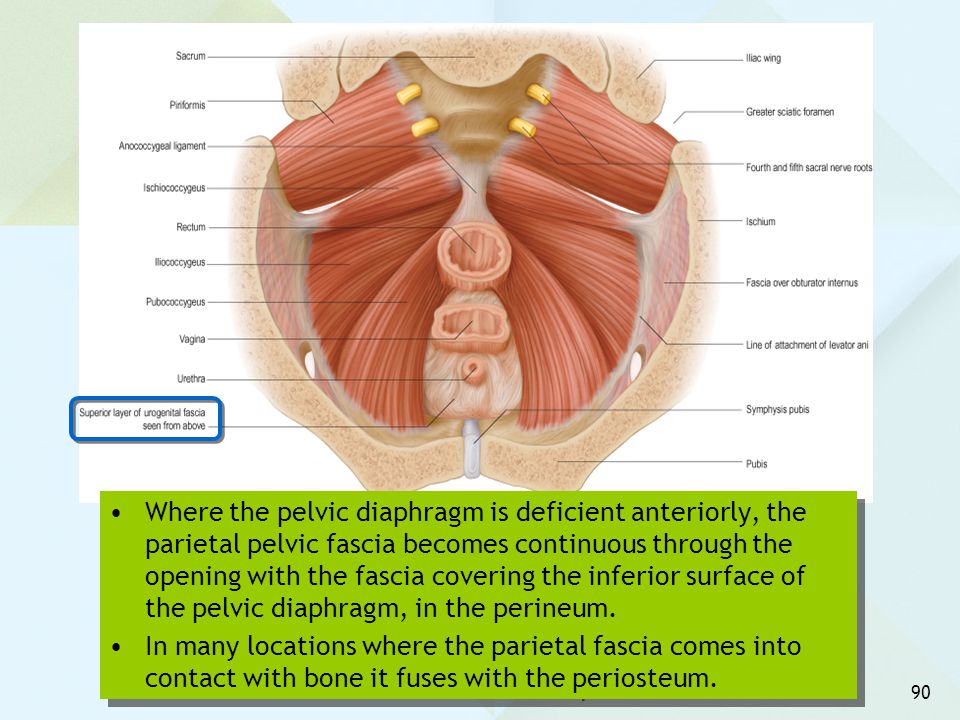

Muscles

The inferior border of the pelvic cavity is the pelvic diaphragm. It is made up of a group of muscles. From posterior to anterior, these muscles include:

Piriformis

Coccygeus

Iliococcygeus

Pubococcygeus

Puborectalis

The fibers of the iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis make up the levator ani muscle. Because of its proximity to the vagina, the pubococcygeus and puborectalis are the most commonly injured muscles during vaginal deliveries.[18] The obturator internus muscles make up the peripheral borders of the pelvis but are not among the muscles of the pelvic floor.

Because of its proximity to the vagina, the pubococcygeus and puborectalis are the most commonly injured muscles during vaginal deliveries.[18] The obturator internus muscles make up the peripheral borders of the pelvis but are not among the muscles of the pelvic floor.

Ligaments

Three ligaments anchor the uterus. The uterosacral ligament supports the uterus posteriorly, and the pubocervical ligament anchors the uterus anteriorly. The transverse cervical ligament supports the uterus laterally. Unlike the anterior and posterior planes that contain the bladder and rectum respectively, the lateral plane lacks supporting structures other than the transverse cervical ligament. It is for this reason that this ligament also has the name of the "cardinal" ligament. The transverse ligament also differs from other supporting ligaments of the uterus because it is the only ligament that contains a vasculature structure, the uterine artery.

The ovary also has ligamentous support. The utero-ovarian ligament, also known as the ovarian ligament, extends from the ovary to the uterine body. The ovary is supported superiorly by the infundibulopelvic ligament, also known as the suspensory ligament of the ovary. This ligament descends from the lateral aspect of the abdominal wall and contains the ovarian neurovascular bundle.

The utero-ovarian ligament, also known as the ovarian ligament, extends from the ovary to the uterine body. The ovary is supported superiorly by the infundibulopelvic ligament, also known as the suspensory ligament of the ovary. This ligament descends from the lateral aspect of the abdominal wall and contains the ovarian neurovascular bundle.

The broad ligament overlies the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. It is the inferior most extension of the parietal peritoneum and has three divisions based on location. The lateral most aspect of the broad ligament is the "mesovarium" and overlies the ovaries. The "mesosalpinx" covers the fallopian tubes. The largest portion of the broad ligament is the "mesometrium" and overlies the uterus.

Physiologic Variants

The uterine and ovarian arteries supply the majority of the female reproductive tract. The uterine artery, like many pelvic arteries, has a variable presentation. It most commonly arises from the anterior branch of the internal iliac artery and shares a common trunk with the obliterated umbilical artery. [19] One study that analyzed imaging from 218 patients reported this presentation in 80.7 % of cases.[20] The same study reported the uterine artery branched directly off of the internal iliac in 13.6% of cases, making this the most common variation. The second and third most common variations they found were direct branching from the superior gluteal artery and internal pudendal artery, respectively. These variations are necessary to be aware of during surgery as well as during uterine artery embolization.

[19] One study that analyzed imaging from 218 patients reported this presentation in 80.7 % of cases.[20] The same study reported the uterine artery branched directly off of the internal iliac in 13.6% of cases, making this the most common variation. The second and third most common variations they found were direct branching from the superior gluteal artery and internal pudendal artery, respectively. These variations are necessary to be aware of during surgery as well as during uterine artery embolization.

Ovarian artery variants are less common, but case reports exist that detail unique aberrations. One case report found an aberrant ovarian artery arising from the external iliac artery.[21] Another study reported an ovarian artery that branched directly from the common iliac artery.[22] These variations are thought to be due to abnormal descent of the ovaries into the pelvis during embryological development and may also correlate to other differences.[23]

Surgical Considerations

Several anatomical relationships are essential for surgeons to be aware of when operating in the female pelvis. For example, during a cesarean section, the bladder should always be identified to avoid iatrogenic cystotomy. This cautionary measure is especially the case in patients that have had a prior cesarean section because scar tissue can cause the bladder to adhere to the anterior uterine wall.

For example, during a cesarean section, the bladder should always be identified to avoid iatrogenic cystotomy. This cautionary measure is especially the case in patients that have had a prior cesarean section because scar tissue can cause the bladder to adhere to the anterior uterine wall.

During any uterine surgery, identification of the uterine artery is vital. If cut, massive bleeding can ensue. During abdominal hysterectomies, the uterine artery is typically “skeletonized” so that its path along the uterus is clearly identifiable to the operating team.

If hemorrhage does occur, knowledge of pelvic vasculature becomes crucial. If the bleeding vessel cannot be clearly identified, the internal iliac should be clamped below the origin of the superior gluteal artery. This method is preferred so that necrosis of the gluteal muscle does not occur.

When operating deeper in the female pelvis, identification of the ureter is also crucial. There are three major locations where this structure may exist. Beginning superiorly, the ureters descend into the pelvis posterior to the infundibulopelvic ligaments. The ureters maintain this relationship until approximately the level of the iliac vessels, where they begin to travel more medially.

Beginning superiorly, the ureters descend into the pelvis posterior to the infundibulopelvic ligaments. The ureters maintain this relationship until approximately the level of the iliac vessels, where they begin to travel more medially.

As the ureters continue to travel inferiorly, the next important landmark is the transverse cervical ligament. The ureters dive under this structure. Awareness of this relationship is of considerable importance when performing a hysterectomy. A popular pneumonic used by medical students is, "water under the bridge."

After passing under the transverse cervical ligament, the ureters continue to travel medially toward the bladder. Their insertion into the inferior aspect of the bladder is the third major location they should undergo positive identification intraoperatively. The insertion points are also visible from inside the bladder itself, during cystoscopy; this is sometimes performed after pelvic surgery if an injury to the bladder is suspected.

Injury to the bladder can also occur during pelvic surgery from the vaginal approach. When operating in this plane, injury to the rectum is also a possibility because at this level the rectum is directly posterior to the vagina (Figure 6.) Avoiding bladder and rectal injury becomes increasingly difficult if the patient has pelvic organ prolapse, such as cystocele or rectocele.

When performing surgery on the fallopian tubes, such as during a tubal ligation or tubal anastomosis, the location of the round ligament should be determined. Due to the similarity in structure and location, the round ligament can be mistaken for a fallopian tube. Unlike the round ligaments, however, the fallopian tubes have fimbriae, a characteristic can be used to differentiate between these two structures intraoperatively.

Clinical Significance

Clinical correlates related to female pelvic anatomy can be summarized as follows:

The standard position of the uterus is anteverted and anteflexed.

Abnormal positioning of the uterus is associated with pathology. Retroversion, for example, is a cause of dyspareunia. Additionally, retroversion of a gravid uterus is associated with higher rates of spontaneous abortion.

Abnormal positioning of the uterus is associated with pathology. Retroversion, for example, is a cause of dyspareunia. Additionally, retroversion of a gravid uterus is associated with higher rates of spontaneous abortion.The posterior cul-de-sac, located between the uterus and the rectum, is a potential space prone to fluid collection. Physiologic fluid accumulates during menses and ovulation. If fluid collection is pathologic, this space can undergo drainage via culdocentesis.

The posterior cul-de-sac communicates with the abdomen via the left and right epiploic gutters, which allows the spread of pelvic pathogens into the abdominal cavity. Due to the leftward position of the rectum, infections usual take the path of the right epiploic gutter. The right epiploic gutter leads to potential spaces surrounding the liver. These include the hepatorenal space, also known as Morrison’s pouch, and the subphrenic space. Infection of the subphrenic space secondary to a gonococcal pelvic infection is termed Fitz-Curtis-Hugh syndrome or gonococcal perihepatitis.

The increased length of the left ovarian vein makes it more susceptible to compression, especially during pregnancy. Compression of this vessel sometimes leads to pelvic venous compression syndrome and is a cause of chronic pelvic pain in both pregnant and non-pregnant patients.

Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy is most commonly left-sided and occur in the iliofemoral vessels, which is thought to be because of pelvic vessel engorgement in combination with the increased path the left iliac vein takes across the pelvis. These factors make this vessel more susceptible to compression by a gravid uterus.

Understanding the lymphatic drainage of the female reproductive tract is important when tracking the spread of gynecologic malignancies. Generally, the female reproductive organs drain to the internal and external iliac lymph nodes. A notable exception is the ovaries, which drain to the paraaortic lymph nodes.

The pudendal nerve receives sensory innervation to the lower vagina.

Historically, pudendal nerve blocks were used to alleviate labor pains. However, pudendal nerve blocks are no longer commonly practiced due to the wide-spread use of epidural anesthesia.

Historically, pudendal nerve blocks were used to alleviate labor pains. However, pudendal nerve blocks are no longer commonly practiced due to the wide-spread use of epidural anesthesia.The muscles of the pelvic floor are susceptible to injury during vaginal deliveries. The most commonly injured muscles are the pubococcygeus and puborectalis muscles due to their proximity to the vagina.

The pelvic vasculature contains many physiologic variants that are important for surgeons to know. Interventional radiologists should also be knowledgeable of variants, particularly during uterine artery embolization to treat fibroids. The uterine artery most commonly arises from the anterior branch of the internal iliac and shares a trunk with the obliterated umbilical artery. The most common variation is direct branching from the internal iliac.

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

Figure

Compilation of 6 images detailing anatomy of female pelvic cavity. Contributed by Gray's Anatomy Plates (Public Domain)

References

- 1.

Roach MK, Andreotti RF. The Normal Female Pelvis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Mar;60(1):3-10. [PubMed: 28005593]

- 2.

Weekes AR, Atlay RD, Brown VA, Jordan EC, Murray SM. The retroverted gravid uterus and its effect on the outcome of pregnancy. Br Med J. 1976 Mar 13;1(6010):622-4. [PMC free article: PMC1639005] [PubMed: 1252851]

- 3.

Sanders RC, Parsons AK. Anteverted retroflexed uterus: a common consequence of cesarean delivery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014 Jul;203(1):W117-24. [PubMed: 24951223]

- 4.

Turco G, Chiesa GM, de Manzoni G. [Echographic anatomy of the greater peritoneal cavity and its recesses]. Radiol Med. 1988 Jan-Feb;75(1-2):46-55. [PubMed: 3279472]

- 5.

Yao HH. The pathway to femaleness: current knowledge on embryonic development of the ovary.

Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005 Jan 31;230(1-2):87-93. [PMC free article: PMC4073593] [PubMed: 15664455]

Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005 Jan 31;230(1-2):87-93. [PMC free article: PMC4073593] [PubMed: 15664455]- 6.

Robboy SJ, Kurita T, Baskin L, Cunha GR. New insights into human female reproductive tract development. Differentiation. 2017 Sep - Oct;97:9-22. [PMC free article: PMC5712241] [PubMed: 28918284]

- 7.

Jeanneret C, Beier K, von Weymarn A, Traber J. Pelvic congestion syndrome and left renal compression syndrome - clinical features and therapeutic approaches. Vasa. 2016;45(4):275-82. [PubMed: 27428495]

- 8.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: Thromboembolism in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jul;132(1):e1-e17. [PubMed: 29939938]

- 9.

Coleman RL, Frumovitz M, Levenback CF. Current perspectives on lymphatic mapping in carcinomas of the uterine corpus and cervix. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006 May;4(5):471-8. [PubMed: 16687095]

- 10.

Burke TW, Levenback C, Tornos C, Morris M, Wharton JT, Gershenson DM. Intraabdominal lymphatic mapping to direct selective pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer: results of a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol. 1996 Aug;62(2):169-73. [PubMed: 8751545]

- 11.

Geppert B, Lönnerfors C, Bollino M, Arechvo A, Persson J. A study on uterine lymphatic anatomy for standardization of pelvic sentinel lymph node detection in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 May;145(2):256-261. [PubMed: 28196672]

- 12.

Uchida S, Kagitani F. Autonomic nervous regulation of ovarian function by noxious somatic afferent stimulation. J Physiol Sci. 2015 Jan;65(1):1-9. [PMC free article: PMC4276811] [PubMed: 24966153]

- 13.

Pastelín CF, Rosas NH, Morales-Ledesma L, Linares R, Domínguez R, Morán C. Anatomical organization and neural pathways of the ovarian plexus nerve in rats. J Ovarian Res. 2017 Mar 14;10(1):18.

[PMC free article: PMC5351206] [PubMed: 28292315]

[PMC free article: PMC5351206] [PubMed: 28292315]- 14.

Cruz G, Fernandois D, Paredes AH. Ovarian function and reproductive senescence in the rat: role of ovarian sympathetic innervation. Reproduction. 2017 Feb;153(2):R59-R68. [PubMed: 27799628]

- 15.

Mónica Brauer M, Smith PG. Estrogen and female reproductive tract innervation: cellular and molecular mechanisms of autonomic neuroplasticity. Auton Neurosci. 2015 Jan;187:1-17. [PMC free article: PMC4412365] [PubMed: 25530517]

- 16.

Mowa CN. Uterine Cervical Neurotransmission and Cervical Remodeling. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2017;18(2):120-124. [PubMed: 27001061]

- 17.

Schrock SD, Harraway-Smith C. Labor analgesia. Am Fam Physician. 2012 Mar 01;85(5):447-54. [PubMed: 22534222]

- 18.

Memon HU, Handa VL. Vaginal childbirth and pelvic floor disorders. Womens Health (Lond). 2013 May;9(3):265-77; quiz 276-7. [PMC free article: PMC3877300] [PubMed: 23638782]

- 19.

Peters A, Stuparich MA, Mansuria SM, Lee TT. Anatomic vascular considerations in uterine artery ligation at its origin during laparoscopic hysterectomies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep;215(3):393.e1-3. [PubMed: 27287682]

- 20.

Chantalat E, Merigot O, Chaynes P, Lauwers F, Delchier MC, Rimailho J. Radiological anatomical study of the origin of the uterine artery. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014 Dec;36(10):1093-9. [PubMed: 24052200]

- 21.

Kwon JH, Kim MD, Lee KH, Lee M, Lee MS, Won JY, Park SI, Lee DY. Aberrant ovarian collateral originating from external iliac artery during uterine artery embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013 Feb;36(1):269-71. [PubMed: 22565531]

- 22.

Kim WK, Yang SB, Goo DE, Kim YJ, Chang YW, Lee JM. Aberrant ovarian artery arising from the common iliac artery: case report. Korean J Radiol. 2013 Jan-Feb;14(1):91-3. [PMC free article: PMC3542308] [PubMed: 23323036]

- 23.

Rahman HA, Dong K, Yamadori T.

Unique course of the ovarian artery associated with other variations. J Anat. 1993 Apr;182 ( Pt 2):287-90. [PMC free article: PMC1259840] [PubMed: 8376204]

Unique course of the ovarian artery associated with other variations. J Anat. 1993 Apr;182 ( Pt 2):287-90. [PMC free article: PMC1259840] [PubMed: 8376204]

Pelvis / Female Anatomy

Pelvis

The small pelvis is the lower half of the pelvis of a woman, in which the uterus with appendages, the bladder and rectum, blood vessels and nerves are located. The organs of the small pelvis are fixed to the walls of the pelvis with the help of ligaments and fascia. For ease of understanding, this design can be compared to a suspension bridge.

Front and back - bridge supports (pubis and sacrum). A bridge (vagina) is stretched between them. Ropes (bundles) stretch from the upper part of the supports to the bridge. From the back support (sacrum) - sacro-uterine ligaments. From the anterior support (pubis) - pubo-urethral ligaments.

The bridge (vagina) can be compared to the membrane of a trampoline, and the ligaments of the pelvis to its springs.

The bladder lies on the anterior wall of the vagina like in a hammock.

The main pelvic fascia is the pubocervical fascia. This is a connective tissue sheet between the anterior wall of the vagina and the bladder. This fascia is the hammock, trampoline, or suspension bridge. She fascia is stretched from front to back with the help of the described ligaments, and on the sides is attached to the walls of the pelvis.

Defects in the ligamentous and/or fascial structures that occur during childbirth lead to various types of prolapse of the pelvic organs.

The most important supporting ligament is the sacro-uterine, which fixes the entire structure from above. With its defect, the connection between the bridge and its rear support is lost. The pubocervical fascia, having lost support from above, breaks away from the walls of the pelvis. There is a prolapse of the uterus and the anterior wall of the vagina. Therefore, the most common type of prolapse (omission) is anteroapical (a combination of prolapse of the uterus and the anterior wall of the vagina).

The pubo-urethral ligament plays an important role in the urinary continence mechanism. It fixes the urethra in the middle third, limits its mobility. A defect in this ligament causes abnormal mobility of the urethra and disrupts the mechanism of urinary retention.

Corresponding to this anatomical organ:

- Diseases

- Endometriosis

- Uterine prolapse

- Rectocele

- Operations

- Infiltrate resection

- Surgery for complications

- Enterocele correction

- Rectocele correction

- Correction of the entrance to the vagina

- Laparoscopic sacrovaginopexy

- OPUR

- Sacrospinal hysteropexy

The pelvis as a whole, its dimensions are

Updated: 10/26/2022

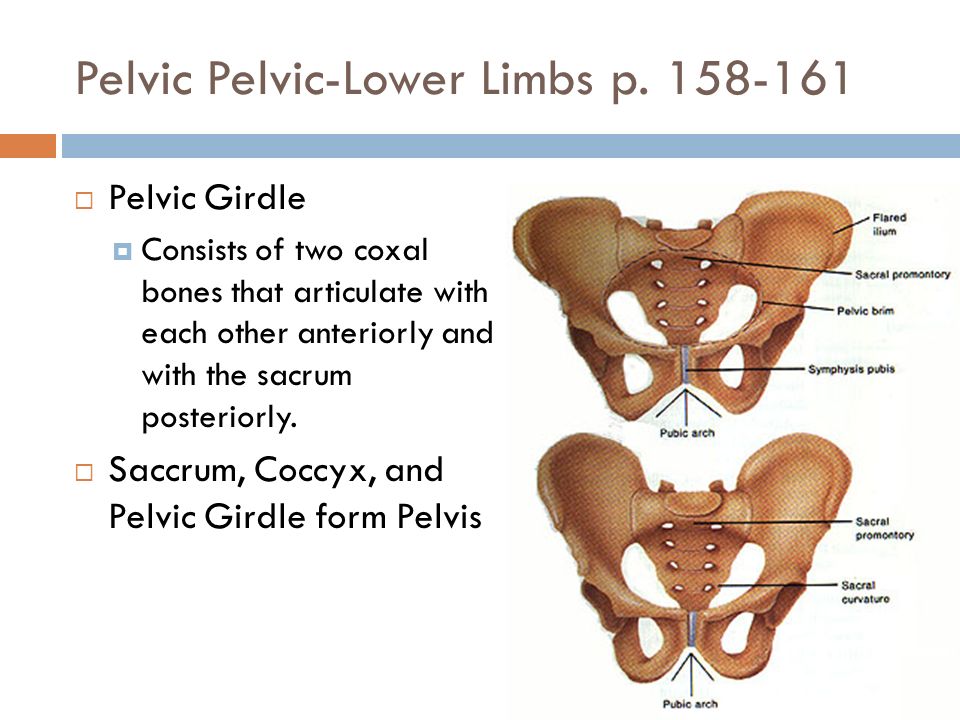

The pelvis (pelvis) in the form of a bone ring formed by the connection of the pelvic bones with each other and with the sacrum, serves to connect the trunk with the free lower limbs. It is divided into 2 sections: the upper, wide - the large pelvis and the lower, narrow - the small pelvis.

It is divided into 2 sections: the upper, wide - the large pelvis and the lower, narrow - the small pelvis.

Large pelvis is part of the abdominal cavity, bounded laterally by the deployed wings of the ilium. In front, it has no bony walls, and behind it is limited by the lumbar vertebrae.

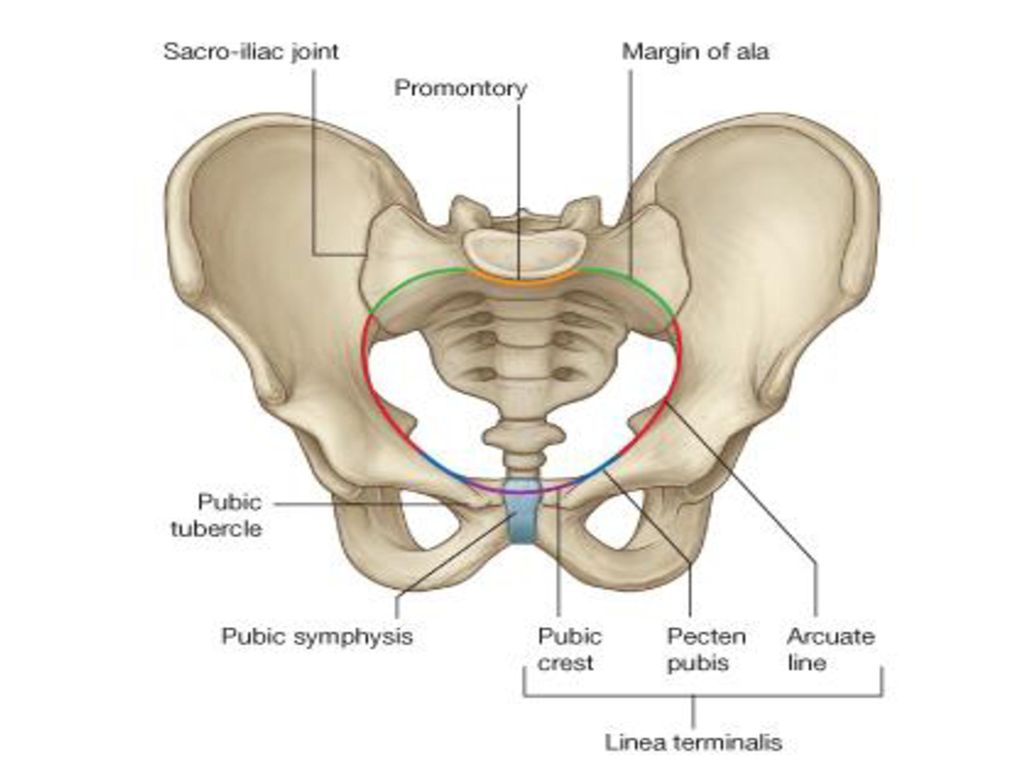

The greater pelvis is separated from the lesser pelvis by a boundary line formed by the promontory, the arched edge of the ilium, the superior rami of the pubis, and the superior margin of the pubic symphysis. The opening thus limited is called the entrance or the upper aperture of the small pelvis, below which lies its cavity.

Anteriorly, the wall of the small pelvis is short and is formed by the pubic bones and their joints, as well as the obturator membranes. Behind the wall is long and consists of the sacrum and coccyx. The lateral walls of the small pelvis are formed by the bodies of three bones adjacent to the acetabulum, branches of the pubic and ischial bones, as well as ligaments that run from the sacrum to the ischial tuberosities and awns. The exit from the cavity of the small pelvis or the lower aperture is closed by the muscles and fascia of the perineum.

The exit from the cavity of the small pelvis or the lower aperture is closed by the muscles and fascia of the perineum.

Sex differences begin to appear at the onset of puberty. The bones of the female pelvis are smoother and thinner. The wings of the ilium in women are deployed to the sides. The upper aperture of the small female pelvis has a transverse-oval shape, while in the male pelvis it is longitudinally oval. The cape of the male pelvis protrudes more forward. The pelvic surface of the sacrum is more concave, while in women, on the contrary, the sacrum is relatively wider and at the same time more flat. The exit from the small pelvis in men is much narrower than in women. The ischial tubercles, which limit the lower aperture in women, are further apart, and the coccyx protrudes less forward. The subpubic angle in women is obtuse and arch-shaped, while in men it is more acute. The pelvic cavity in men is funnel-shaped, in women the pelvis is cylindrical.

Skeleton of the free lower limb

The free lower limb consists of the following parts: femur, tibia and foot. The skeleton of these departments is formed by the femur, two bones of the lower leg and the bones of the foot. On the lower limb is the largest sesamoid bone - the patella.

The skeleton of these departments is formed by the femur, two bones of the lower leg and the bones of the foot. On the lower limb is the largest sesamoid bone - the patella.

Femur

The femur (femur) is the largest tubular bone in the human skeleton. It refers to the long levers of movement.

At the proximal end of the femur is the articular head, which has a round shape. There is a small rough fossa on it - the place of attachment of the ligament of the femoral head. Lateral to the head is the neck, which forms an obtuse angle with the axis of the femoral body. On the border of the neck and body of the femur, there are two bony protrusions called the greater and lesser skewers. Muscles are attached to them. In front, the skewers are connected by an intertrochanteric line, and behind - by an intertrochanteric ridge. The body of the femur is somewhat convex anteriorly and has a triangular-rounded shape; on its back side there is a trace of attachment of the thigh muscles - a rough line consisting of two lips - lateral and medial.

The distal end of the femur is thickened and bears two round, folded back, lateral and medial condyles. With a strictly vertical position of the femur, the medial condyle protrudes more downward than the lateral one. But, since in its natural position the femur is oblique, and its lower end is closer to the midline than the upper one, the condyles are on the same level. On the anterior surface of the condyles is a slight concavity for the patella. Posteriorly and inferiorly, the condyles are separated by a deep intercondylar fossa. On the side of each condyle above its articular surface is a rough epicondyle.

Pelvic bones, their structure, connections. Taz in general. age and gender characteristics. dimensions.

The pelvic bones and the sacrum, connecting with the help of the sacroiliac joints and the pubic symphysis, form the pelvis, pelvis. . The pelvis is a bone ring, inside of which there is a cavity containing internal organs: the rectum, bladder, etc. With the participation of the pelvic bones, the trunk is also connected to the free lower limbs. The pelvis is divided into two sections: upper and lower. The upper section is the large pelvis, and the lower section is the small pelvis. The large pelvis is separated from the small pelvis by a boundary line, which is formed by the cape of the sacrum, the arcuate line of the ilium, the crests of the pubic bones and the upper edges of the pubic symphysis.

The pelvis is divided into two sections: upper and lower. The upper section is the large pelvis, and the lower section is the small pelvis. The large pelvis is separated from the small pelvis by a boundary line, which is formed by the cape of the sacrum, the arcuate line of the ilium, the crests of the pubic bones and the upper edges of the pubic symphysis.

The large pelvis, pelvis major, is bounded behind by the body of the fifth lumbar vertebra, on the sides by the wings of the ilium. In front, the large pelvis has no bony walls. The pelvic cavity is the lower part of the abdominal cavity.

The small pelvis, pelvis minor, is a narrowed downward bone canal (cavity). The upper opening of this canal, the upper pelvic aperture, apertura pelvis superior, is the entrance to the small pelvis and is limited by the boundary line. The exit from the small pelvis is the lower pelvic aperture, apertura pelvis inferior, limited behind by the coccyx, on the sides by the sacrotuberous ligaments, ischial tubercles, branches of the ischial bones, lower branches of the pubic bones, and in front by the lower branches of the pubic bones. The posterior wall of the pelvic cavity is formed by the pelvic surface of the sacrum and the anterior surface of the coccyx. The anterior wall is represented by the lower and upper branches of the pubic bones and the pubic symphysis. From the sides, the cavity of the small pelvis is limited by the inner surface of the pelvic bones below the border line, sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. On the right and on the left there are obturator openings, each closed by a fibrous plate - the obturator membrane, membrdna obturatoria, which is the ligament of the pelvic bone itself.

The posterior wall of the pelvic cavity is formed by the pelvic surface of the sacrum and the anterior surface of the coccyx. The anterior wall is represented by the lower and upper branches of the pubic bones and the pubic symphysis. From the sides, the cavity of the small pelvis is limited by the inner surface of the pelvic bones below the border line, sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. On the right and on the left there are obturator openings, each closed by a fibrous plate - the obturator membrane, membrdna obturatoria, which is the ligament of the pelvic bone itself.

Connected by the pubic symphysis, the lower branches of the pubic bones close the pelvic ring in front.

In the structure of the pelvis of an adult, sexual characteristics are clearly expressed. The pelvis in women is lower and wider than in men. The distance between the spines and iliac crests in women is greater, since the wings of the iliac bones are more deployed to the sides. Thus, the cape in women protrudes less than in men, so the upper aperture of the female pelvis is more rounded than that of the male. In women, the sacrum is wider and shorter than in men, the ischial tuberosities are turned to the sides, the distance between them is greater than in men. The angle of convergence of the lower branches of the pubic bones in women is more than 90° (pubic arch), and in men it is 70-75° (subpubic angle).

In women, the sacrum is wider and shorter than in men, the ischial tuberosities are turned to the sides, the distance between them is greater than in men. The angle of convergence of the lower branches of the pubic bones in women is more than 90° (pubic arch), and in men it is 70-75° (subpubic angle).

The size and shape of the pelvis are of great importance for the birth process. Knowing the average size of the entrance and exit from the small pelvis is necessary to predict the course of labor. Direct The size of the entrance to the small pelvis - true, or gynecological, conjugate, conjugdta vera, seu conjugata gyneco-°gi-ca (Fig. 93, 94), usually equal to 11 cm, is the distance between the cape and the most protruding posterior point pubic symphysis.

The transverse diameter, diameter transversa, of the entrance to the small pelvis is the distance between the most distant points of the boundary line that delimits the small pelvis from the large one. This size is about 13 cm. The oblique diameter, diameter obliqua, of the entrance to the small pelvis is 12 cm. It is the distance between the sacroiliac joint, on the one hand, and the iliopubic eminence, on the other.

The oblique diameter, diameter obliqua, of the entrance to the small pelvis is 12 cm. It is the distance between the sacroiliac joint, on the one hand, and the iliopubic eminence, on the other.

The right direction and size of the exit from the pelvic cavity is equal to the distance between the inner edges of the ischial tuberosities (11 cm). The dimensions of the large pelvis are also of practical importance, namely the distance between the two upper anterior iliac spines - distantia spindrum, which is 25-27 cm, and the distance between the most distant points of the wings of the ilium - distantia cristarum - 28-30 cm.

Pelvis as a whole. Age and sex differences, the size of the female pelvis.

The pelvis is generally divided into large and small along the border through the sacral cape (formed by the anterior part of the base of the sacrum and the body of the Y lumbar vertebra), through the arcuate lines of the ilium, crests of the pubic bones and the upper edge of the pubic symphysis - the entire border is called the boundary line. The cavity the pelvis is occupied by internal organs and muscles, from below it is limited by the pelvic and urogenital diaphragms. Outside the pelvis are the muscles of the lower girdle.

The cavity the pelvis is occupied by internal organs and muscles, from below it is limited by the pelvic and urogenital diaphragms. Outside the pelvis are the muscles of the lower girdle.

In the small pelvis, there are: the upper aperture (inlet), the cavity with wide and narrow parts, the lower aperture (outlet). The upper aperture coincides with the borderline, the lower one passes behind through the top of the coccyx, on the sides through the sacrotuberous ligaments, ischial tubercles, ischial branches, in front along the edge of the inferior pubic branches and the lower edge of the pubic symphysis. On the front wall of the small pelvis there are obturator openings with the same canals, on the side walls - large and small ischial openings, limited by the same bone notches and sacrotuberous, sacrospinous ligaments.

Age differences in the structure of the pelvis are determined by changes in the angle of inclination and the degree of curvature of the sacrum and coccyx. Individual fluctuations in the angle of inclination of the pelvis (for men - within 50-55 o, for women - 55-60 o) vary depending not only on gender, but also on the position of the body. In a sports or military stance, the angle of inclination increases as much as possible, in a sitting position it decreases as much as possible. Significant age-related fluctuations are also observed in terms of ossification of the bones of the pelvic ring.

Individual fluctuations in the angle of inclination of the pelvis (for men - within 50-55 o, for women - 55-60 o) vary depending not only on gender, but also on the position of the body. In a sports or military stance, the angle of inclination increases as much as possible, in a sitting position it decreases as much as possible. Significant age-related fluctuations are also observed in terms of ossification of the bones of the pelvic ring.

Sex differences are manifested in the following:

female pelvis, and especially its cavity, wide and low, with a cylindrical shape; male - narrow and high with a conical cavity;

· women's promontory protrudes slightly into the cavity, forming an oval-shaped entrance; the cape in men protrudes strongly, forming an entrance in the form of a card heart;

female sacrum is wide and short with a slightly concave, almost flat pelvic surface; male - narrow and long, strongly curved along the pelvic surface;

subpubic angle in women - more than 90 degrees, in men - 70-75 degrees;

· the wings of the ilium in women are more turned outwards, while in men they are more vertical;

The linear dimensions of the female pelvis predominate over those of men.

In the large pelvis in women, three transverse and one longitudinal dimensions are distinguished:

· interspinous dimension, as a direct distance of 23-25 cm between the anterior superior iliac spines;

intercrest dimension, as a straight distance of 26-28 cm between the most distant points of the iliac crests;

intertrochanteric size, as a straight distance of 30-33 cm between the most distant points of the greater trochanters;

All dimensions of the large pelvis are measured with a thickness caliper in a living woman, since these bone formations are easily palpable. By the size of the large pelvis and its shape, one can indirectly judge the shape of the small pelvis.

In the small pelvis, transverse, oblique, longitudinal dimensions (diameters) are distinguished, which in each part of the pelvis (upper, lower apertures, cavity) are also measured between certain bone landmarks. So, for example, the transverse diameter of the entrance is the distance of 12-13 cm between the most distant points of the arcuate line on the ilium; oblique diameter - a distance of 12 cm between the sacroiliac joint of one side and the iliac-pubic eminence of the opposite side; direct size of 11 cm, as the distance between the cape and the most protruding posterior point of the pubic symphysis. Direct exit size of 9cm is the distance between the tip of the coccyx and the lower edge of the pubic symphysis; the transverse size of the outlet is 11 cm - the distance between the ischial tubercles. If you connect the midpoints of all direct sizes, you get a wire axis of the small pelvis - a gentle curve, concave facing the symphysis. This is the direction of movement of the child being born.

Direct exit size of 9cm is the distance between the tip of the coccyx and the lower edge of the pubic symphysis; the transverse size of the outlet is 11 cm - the distance between the ischial tubercles. If you connect the midpoints of all direct sizes, you get a wire axis of the small pelvis - a gentle curve, concave facing the symphysis. This is the direction of movement of the child being born.

The pelvis as a whole

The pelvis (Fig. . 9) is formed by two pelvic bones, the sacrum with the coccyx and their joints. It is a container and protection for many internal organs: the uterus, bladder, rectum, etc. The pelvis is divided by the boundary line into the small and large pelvis. The large pelvis is bounded by the wings of the ilium, the small pelvis by the ischium and pubic bones, sacrum, coccyx, pubic symphysis, ligaments of the pelvis and obturator membranes. Allocate age and sex differences in the structure of the pelvis. The female pelvis is much wider and shorter than the male. This is achieved by the development of the wings of the ilium, a flatter sacrum, an increase in the subpubic angle (obtuse in women), etc. Anatomical data on the structural features and dimensions of the female pelvis are taken into account in obstetrics.

This is achieved by the development of the wings of the ilium, a flatter sacrum, an increase in the subpubic angle (obtuse in women), etc. Anatomical data on the structural features and dimensions of the female pelvis are taken into account in obstetrics.

Fig. 9. Dimensions of the female pelvis (cut in the sagittal plane): 1 - straight diameter (exit from the small pelvis), 2 - pelvic tilt angle, 3 - diagonal conjugate, 4 - straight diameter (pelvic cavity), 5 - true (gynecological) conjugate , 6 - anatomical conjugate (direct size of the entrance to the small pelvis), 7 - large sciatic foramen, 8 - sacrospinous ligament, 9 - small sciatic foramen, 10 - sacrotuberous ligament.

Hip joint (art. coxae) - fig. 10.

10. Hip joint, opened frontally: 1 - femoral head, 2 pelvic bone, 3 - articular cartilage, 4 - articular cavity, 5 - femoral head ligament, 6 - transverse acetabular ligament, 7 - articular capsule, 8 - circular zone , 9 - acetabular lip.

Classification. Simple, bowl-shaped, multi-axial joint.

Structure. Formed by the acetabulum of the pelvic bone and the head of the femur. Articular cavity increases cartilaginous lip, labrum acetabulare. The capsule is attached along the circumference of the acetabulum, and on the femur - along the intertrochanteric line (in front) and along the neck of the femur parallel to the intertrochanteric crest (rear). Inside the joint cavity is located ligament of the femoral head , which connects the head with the notch of the acetabulum, strengthens the joint, softens shocks during movement, conducts blood vessels to the femoral head. External ligaments of the joint: iliofemoral, pubic-femoral, ischio-femoral, circular zone (ligg. iliofemorale, pubofemorale, ischiofemorale, zona orbicularis).

Functions .It allows movements around three axes, but their volume is less than in the shoulder joint. Flexion and extension is possible around the frontal axis: when flexed, the thigh moves forward and presses against the stomach (such maximum flexion is possible due to the peculiarities of the attachment of the synovial membrane of the joint capsule - it does not attach to the femur from behind), while extending the thigh moves back. Around the sagittal axis, the leg is adducted and abducted relative to the midline of the body. Rotation (inward and outward) is possible around the vertical axis.

Around the sagittal axis, the leg is adducted and abducted relative to the midline of the body. Rotation (inward and outward) is possible around the vertical axis.

Knee joint (art. genus) - fig. 11.

Classification. The joint is complex, complex, condylar in shape, biaxial.

Structure. One of the largest and most complex human joints. It is formed by the articular surfaces of the condyles and the patella surface of the femur, the upper articular surface of the tibia and the articular surface of the patella, articulating only with the femur. The capsule is attached along the edges of the articular surfaces of the patella, condyles of the femur and tibia. The joint is supplemented with intra-articular cartilage: lateral and medial menisci (meniscus lateralis et medialis). The shape of the lateral and medial menisci is different, they increase the congruence of the articulating bones, provide reliability in support, and improve the biomechanical capabilities of the joint. The anterior horns of the meniscus are interconnected by transverse ligament of the knee, lig. transversum genus . The knee joint has many synovial bursae, the main of which are suprapatellar, deep infrapatellar and prepatellar bursae complex. Strengthened by ligaments: internal - anterior and posterior cruciate (ligg. cruciata genus anterius et posterius) and external - collateral tibia and fibula (ligg. collaterale tibiale et fibulare). The patella has its own ligament - lig. patellae.

The anterior horns of the meniscus are interconnected by transverse ligament of the knee, lig. transversum genus . The knee joint has many synovial bursae, the main of which are suprapatellar, deep infrapatellar and prepatellar bursae complex. Strengthened by ligaments: internal - anterior and posterior cruciate (ligg. cruciata genus anterius et posterius) and external - collateral tibia and fibula (ligg. collaterale tibiale et fibulare). The patella has its own ligament - lig. patellae.

Fig. 11. Knee joint, right. Opened. Front view. The joint capsule has been removed. 1 - patellar surface, 2 - lateral condyle, 3 - medial condyle, 4 - posterior cruciate ligament, 5 - anterior cruciate ligament, 6 - transverse ligament of the knee, 7 - medial meniscus, 8 - tibial collateral ligament, 9- ligament of the patella, 10 - patella, 11 - head of the fibula, 12 - tibiofibular joint (anterior ligament of the head of the patella), 13 - lateral condyle of the tibia, 14 - lateral meniscus, 15 - peroneal collateral ligament.

Functions The joint can move around two axes: frontal and vertical. Around the frontal axis, flexion and extension of the lower leg occurs. Around the vertical axis (subject to knee flexion), rotation of the lower leg is possible.

Anatomy: The pelvis as a whole, its dimensions

In the formation of the pelvis, pelvis, the pelvic bones, the sacrum with the coccyx and the ligamentous apparatus take part (see Fig. 40). The pelvis is divided into large, pelvis major, and small, pelvis minor. The border between them is the border line, linea terminalis, running from the cape to the arcuate line and further to the pubic tubercle. The small pelvis has two openings: the upper one, apertura pelvis superior, limited by the boundary line, and the lower one, apertura pelvis inferior, bounded behind by the coccyx, from the sides by the ischial tubercles, sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, in front by the branches of the ischial and pubic bones.

There are two extreme forms of the structure of the female pelvis: one form is characterized by a predominance of longitudinal size, the other - transverse. The size of the male pelvis is 1.5-2 cm smaller than the female one. Deviations in the size of the pelvis depend on the age, body type and size of the subject. Individual features of the external differences in the pelvis may relate to the shape and size of the sacrum, innominate bones, the degree of severity of the cape of the sacrum, etc. Various painful conditions have a great influence on the shape of the pelvis - rickets, spinal deformity, etc. Age-related differences in the pelvis depend on the angle of inclination of the pelvis and degree of curvature of the sacrum.

The size of the male pelvis is 1.5-2 cm smaller than the female one. Deviations in the size of the pelvis depend on the age, body type and size of the subject. Individual features of the external differences in the pelvis may relate to the shape and size of the sacrum, innominate bones, the degree of severity of the cape of the sacrum, etc. Various painful conditions have a great influence on the shape of the pelvis - rickets, spinal deformity, etc. Age-related differences in the pelvis depend on the angle of inclination of the pelvis and degree of curvature of the sacrum.

See also:

- Insulin in myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus. The value of glucose-insulin mixture in diabetes and heart attack

- Access, subchondroplasty technique of the knee

- Problems of the organization of pulmonary surgery. Relationship between thoracic surgery and oncology

- Economic evaluation in medicine. Healthcare inputs and outputs

- Benefits of Bay oil for hair.