How to help a child through grief

Supporting children in times of grief

Speaking of Health

Topics in this Post

- Balance your mental and emotional health

- Child Development

- Children's Health (Pediatrics)

- Behavioral Health

As parents and caregivers of children, it can be challenging to see them struggle or feel hurt, particularly if you're uncertain how to best support them. Regardless of age, grief and loss touch everyone's lives and affects each differently.

As adults attending to your own loss, you can be overwhelmed with the emotional and sometimes physical pain that accompanies the grieving process. The healing journey can start with support from the presence, guidance and encouragement of family and friends.

Invisible grief

Children often are referred to as the forgotten or invisible grievers. You may not always see children’s grief displayed outwardly. Internally, children may feel and react to emotions that are difficult to express.

They might not have the words or understanding of what they feel to communicate or process what they're going through. You may think of children as being resilient. Still, it's only through understanding what they're experiencing and then providing presence, support and coping tools to foster healthy exploration of the emotion and learn from it to build resiliency.

Like adults, children have a wide range of reactions to grief and loss that can be affected by multiple variables. Children’s behavior often can be regressive when feelings are not verbalized. It's important to realize that while a child may not be talking about a loss, they're most certainly thinking about it.

Talking to children about grief

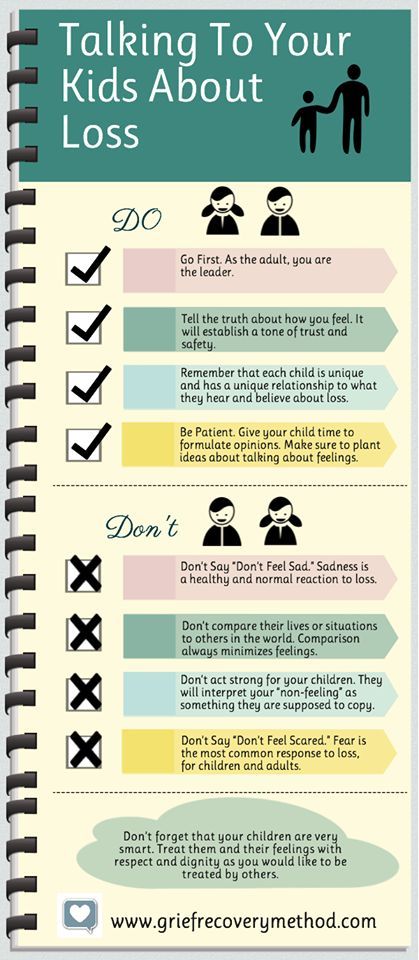

Normalize and validate grief using these strategies:

- Talk about grief to begin awareness.

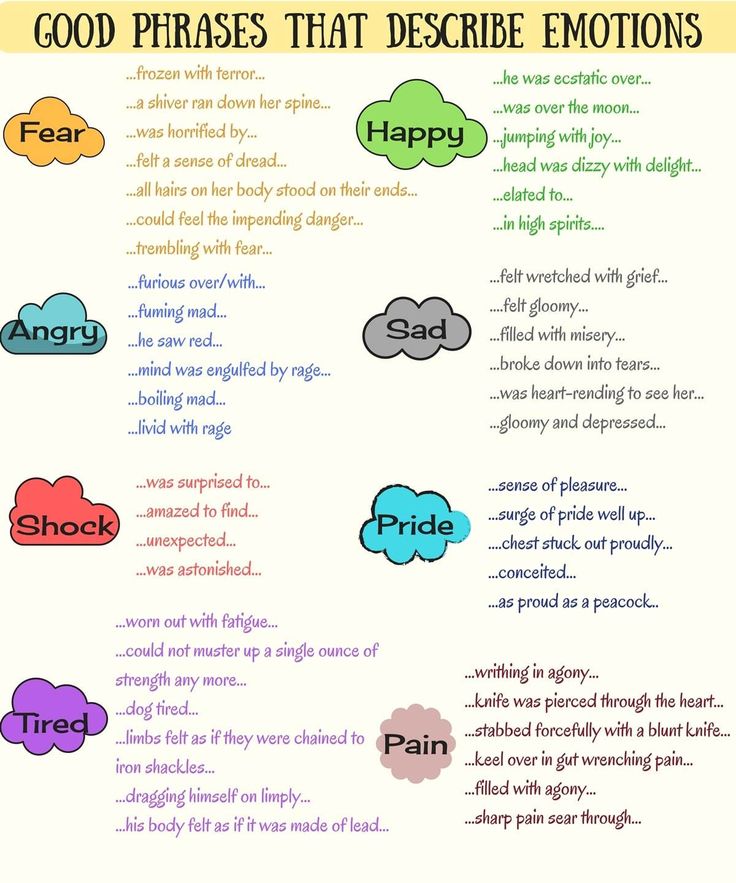

- Share language on how to talk about grief.

- Understand how grief and loss may impact children.

One example of saying this is: "I feel sad since your grandmother passed away. I miss her, and when I think about her, that makes me cry. My tears allow me to let some of my sadness release a bit. After I cry, I still miss her and am sad, but I feel better for a while. Being sad and missing the person is to be expected when they pass on. And releasing the feelings instead of trying to push them away is helpful."

Another example of talking to a sibling is: "I miss your brother so much that I am feeling so many feelings at once. I am sad. I am angry. I am lonesome for him. When I feel that way, it helps me to talk to my friend. She listens and sits with me. When I'm done talking, she may suggest we take a walk or play cards. I still miss your brother and wish he were here with us, but I feel a little better at that moment. Grief hits us differently, but being with others, crying when we need to, and trying different things to feel better all help."

Recurring grief patterns

Grief also is cyclical for children. They may grieve the loss multiple times through different developmental stages in life as understanding deepens. Like adults, children vary in expression and experience of grief. It's important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to grieve.

They may grieve the loss multiple times through different developmental stages in life as understanding deepens. Like adults, children vary in expression and experience of grief. It's important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to grieve.

Parents and caregivers can't protect a child from the pain of loss. Creating a warm, safe and accepting environment for children supports the grief experience and establishes the foundation for healing.

It's important to take your cues from children. Depending on the developmental stage, they may not be able to stay with their emotion for extended amounts of time. You may see children in tears one moment and then playing the next moment. You can learn from children by taking the emotion as it comes and releasing it to move on to another action.

Modeling healthy ways of grieving

Just like other firsts in our lives, we learn by watching and imitating others.

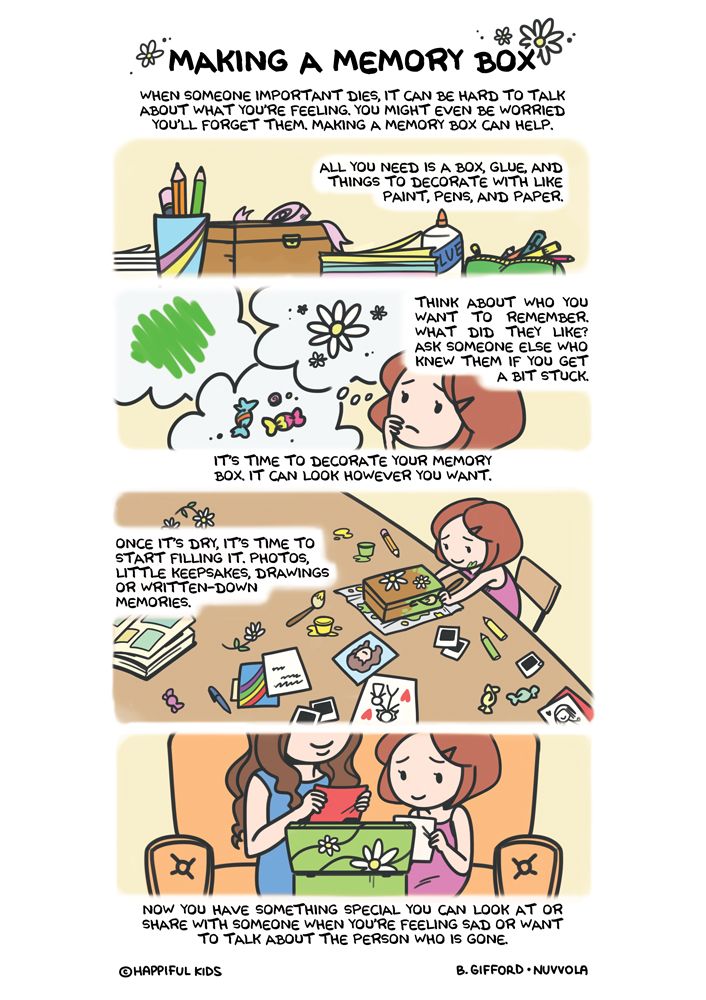

Help make meaning about the loss and normalize talking about grieving the loved one. An important part of grief is finding ways to continue a relationship with the deceased person even though they no longer are present.

An important part of grief is finding ways to continue a relationship with the deceased person even though they no longer are present.

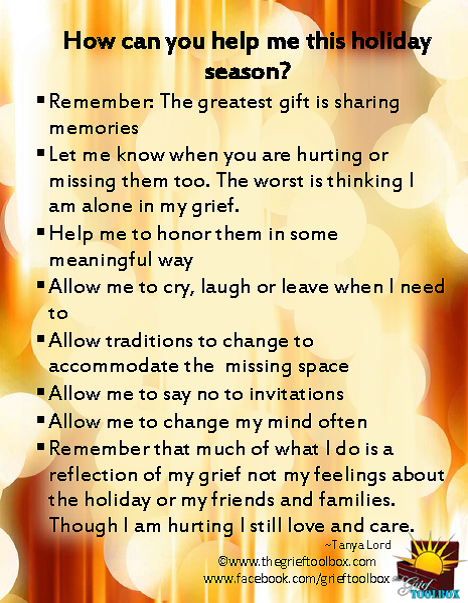

What can that look like daily, on holidays or the anniversary of the death?

Talk with your children about how they're feeling or thinking. Offer answers to questions, but don't overload with more information than what the child is asking or what is developmentally appropriate. It's OK to be honest and direct.

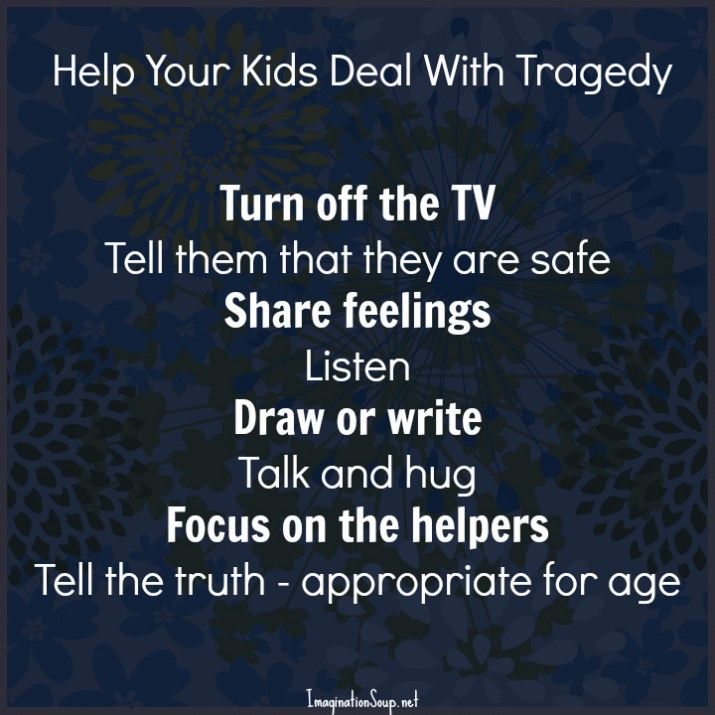

Ways to support a grieving child include:

- Having a consistent and regular routine. Eating well, staying hydrated, doing physical activity and getting good sleep are vital.

- Being patient and gentle, not to add additional stress.

- Allowing for moments of connection and assisting in the expression of grief.

- Providing opportunities to remember and talk about the person who has died.

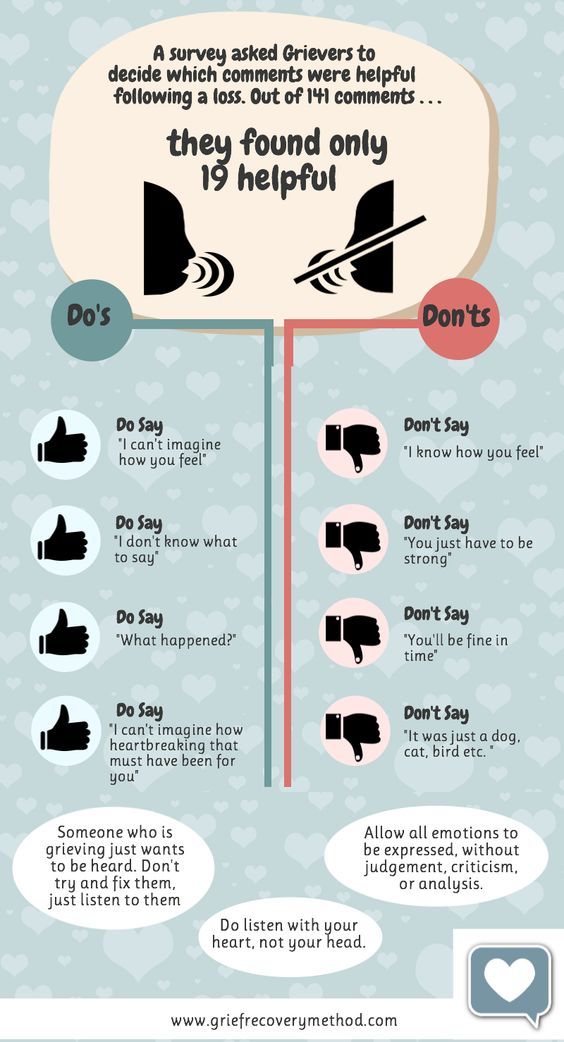

- Listening without judgment or adverse reaction.

- Offering reassurance, teach your children to breathe through their feelings.

- Incorporate mindfulness to notice their feelings right now and let them know it's ok to name the emotions and not fight them.

- Encourage children to notice how the feelings will come and go, sometimes intense and sometimes mild.

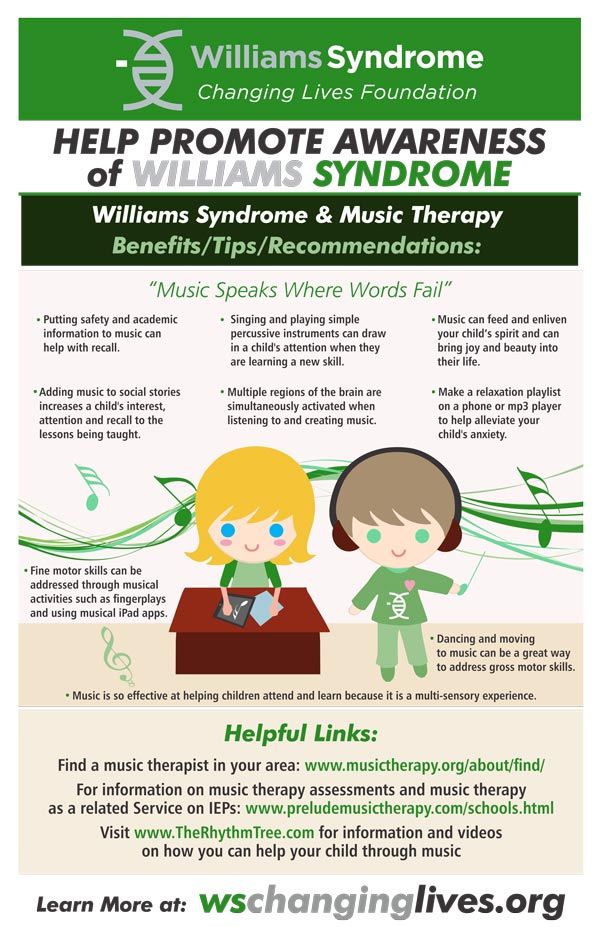

- Creating outlets for healing through time outdoors, arts and crafts, writing or journaling, music, watching a movie, or spending time with friends.

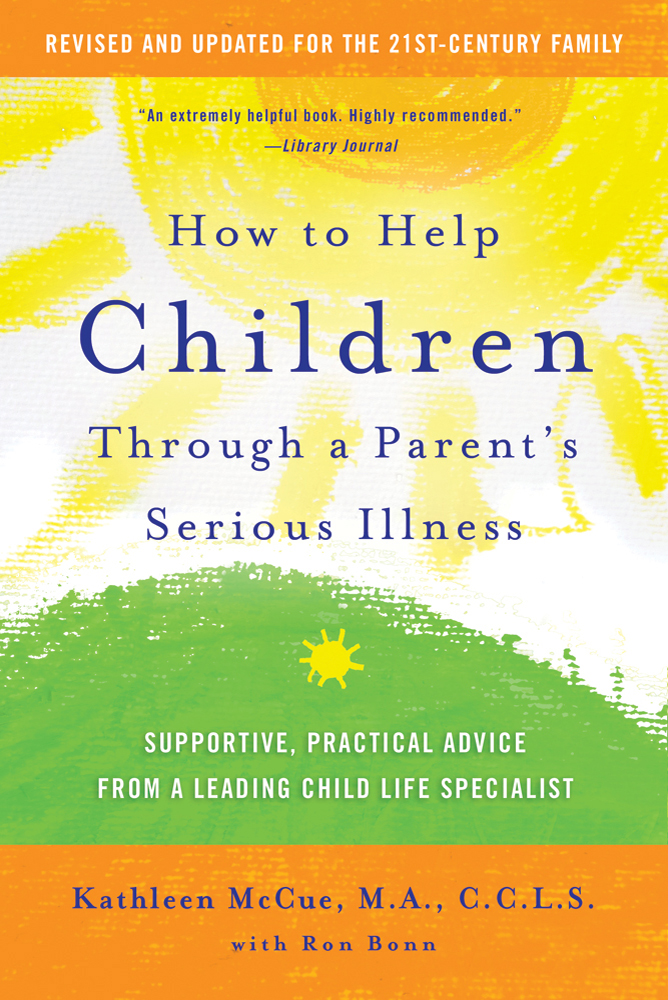

Children may grieve differently than a parent or sibling, and it's important to recognize and accept that. Many good books for children explain the grieving process to help guide conversations and provide language to prompt and answer children's questions.

Lastly, it’s healthy and normal for children to need connection with peers to play, laugh and have time aside from talking about the loss. This is part of the healing and grieving process.

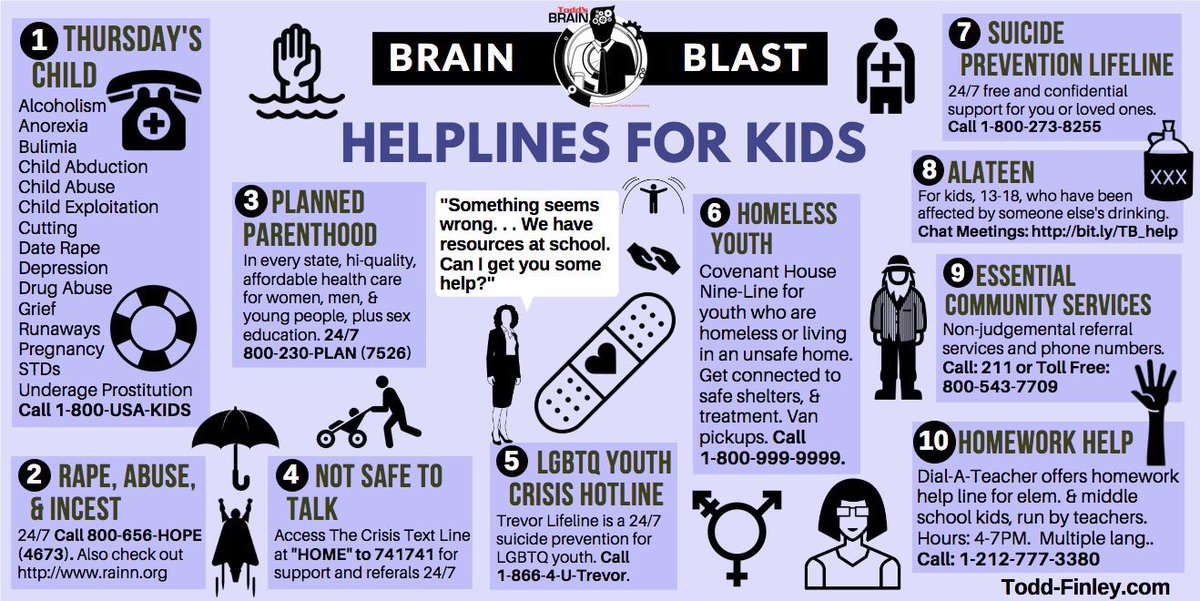

If you feel grief has become complicated for your children, resources are available to help, including grief support groups, your health care team or faith leaders, employee assistance programs through your employer, and professional counseling services.

Grieving isn't about pushing the pain away or getting through it fast and moving on. Grief is a natural and necessary part of healing.

When you honor grief, you heal and grow through grief. You can't take away your children's pain, but it can be an opportunity to teach them to grieve in a good way and watch them learn to heal.

Sarah Cormell is a licensed clinical social worker in Family Medicine in Menomonie, Wisconsin.

For the safety of our patients, staff and visitors, Mayo Clinic has strict masking policies in place. Anyone shown without a mask was either recorded prior to COVID-19 or recorded in a non-patient care area where social distancing and other safety protocols were followed.

Topics in this Post

- Balance your mental and emotional health

- Child Development

- Children's Health (Pediatrics)

- Behavioral Health

Related Posts

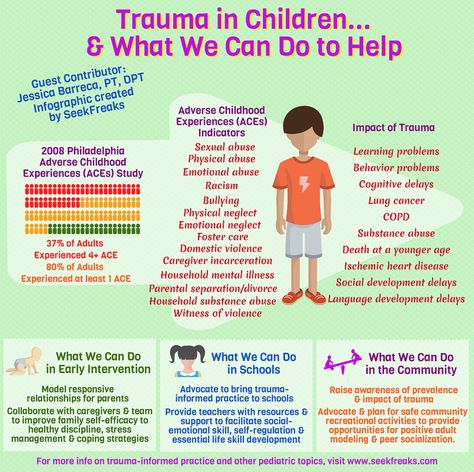

Breaking the adverse childhood experiences cycle

Infants have mental health needs, too

Help! I think my teenager is cutting

Grief and Children

Grief and Children

No. 8; Updated June 2018

8; Updated June 2018

When a family member dies, children react differently from adults. Preschool children usually see death as temporary and reversible, a belief reinforced by cartoon characters who die and come to life again. Children between five and nine begin to think more like adults about death, yet they still believe it will never happen to them or anyone they know.

Adding to a child's shock and confusion at the death of a brother, sister, or parent is the unavailability of other family members, who may be so shaken by grief that they are not able to cope with the normal responsibility of childcare.

Parents should be aware of normal childhood responses to a death in the family, as well as signs when a child is having difficulty coping with grief. It is normal during the weeks following the death for some children to feel immediate grief or persist in the belief that the family member is still alive. However, long-term denial of the death or avoidance of grief can be emotionally unhealthy and can later lead to more severe problems.

A child who is frightened about attending a funeral should not be forced to go, but a plan to honor or remember the person in some way, such as lighting a candle, saying a prayer, making a scrapbook, reviewing photographs, or telling a story, may be helpful to your child's grief process. Children should be allowed to express feelings about their loss and grief in their own way.

Once children accept the death, they are likely to display their feelings of sadness on and off over a long period of time, especially around special times such as birthdays and holidays, but also at unexpected moments. The surviving relatives should spend as much time as possible with the child, making it clear that the child has permission to show his or her feelings openly or freely.

The person who has died was essential to the stability of the child's world, and anger is a natural reaction. The anger may be revealed in boisterous play, nightmares, irritability, or a variety of other behaviors. Often the child will show anger towards the surviving family members.

Often the child will show anger towards the surviving family members.

After a parent dies, many children will act younger than they are. The child may temporarily become more infantile, need attention and cuddling, make unreasonable demands for food, talk baby talk, and even start wetting their beds at night. Younger children frequently believe they are the cause of what happens around them. A young child may believe a parent, grandparent, brother, or sister died because he or she had once wished the person dead when they were angry. The child feels guilty or blames him or herself because the wish came true.

Children who are having serious problems with grief and loss may show one or more of these signs:

- an extended period of depression in which the child loses interest in daily activities and events

- inability to sleep, loss of appetite, prolonged fear of being alone

- acting much younger for an extended period

- excessively imitating the dead person

- believing they are talking to or seeing the deceased family member for an extended period of time

- repeated statements of wanting to join the dead person

- withdrawal from friends

- sharp drop in school performance or refusal to attend school

If these signs persist, professional help may be needed. A child and adolescent psychiatrist or other qualified mental health professional can help the child accept the death and assist the others in helping the child through the mourning process.

A child and adolescent psychiatrist or other qualified mental health professional can help the child accept the death and assist the others in helping the child through the mourning process.

How to help a child survive grief: advice from a psychologist

Categories: Parent meeting, Articles

Tags: psychology,child,parents,family,Teacher

Psychologist's advice

The life path of any person includes both joyful, happy moments, and moments of disappointment, grief. Every child experiences similar feelings from time to time. Let's discuss how adults — parents, teachers — can help a child survive the tragic moments of life

Note that the events that can be called the word "grief" may not exactly coincide for children and adults. So, the loss of a loved one will be a grief for a child, just like for an adult. But besides this, sometimes the death of a beloved pet can become no less grief for a child, something that adults would rather consider a serious nuisance. For a teenager, real grief can be the failure of some business that was very important to him and for which he considered himself responsible, or a quarrel with a close friend, which is perceived as a break in relations forever.

For a teenager, real grief can be the failure of some business that was very important to him and for which he considered himself responsible, or a quarrel with a close friend, which is perceived as a break in relations forever.

We will not consider all these cases, but for now we will only talk about situations of the most severe grief associated with the death of someone close to the child. The severity of grief, the degree and depth of his experience by a child can be different, depending on how the child is prepared for the misfortune that has happened.

Note that in our culture, as in many others, it is not customary to discuss the topic of death. Adults do not discuss it among themselves and, moreover, do not discuss it with children. Often, parents and teachers deliberately try to protect children from any information on this topic, for fear of embarrassing them or provoking suicidal thoughts. However, this position cannot be considered correct. It is in those families where they quite truthfully and clearly answer the child’s questions regarding the topic of death in accessible forms, children are much better prepared for serious losses than in families where adults avoid such conversations in every possible way. Knowledge about death, including its consequences, and awareness of its inevitability is just as necessary a part of preparing for life and a contribution to the psychological development of a child as all other knowledge about the world and life.

Knowledge about death, including its consequences, and awareness of its inevitability is just as necessary a part of preparing for life and a contribution to the psychological development of a child as all other knowledge about the world and life.

Of course, the discussion of such topics requires great tact, caution, taking into account the age of the child, the specifics and traditions of the family, and knowledge of the characteristics of his personality. Therefore, it is reasonable that educators, teachers, psychologists also take their professional part in the education of children.

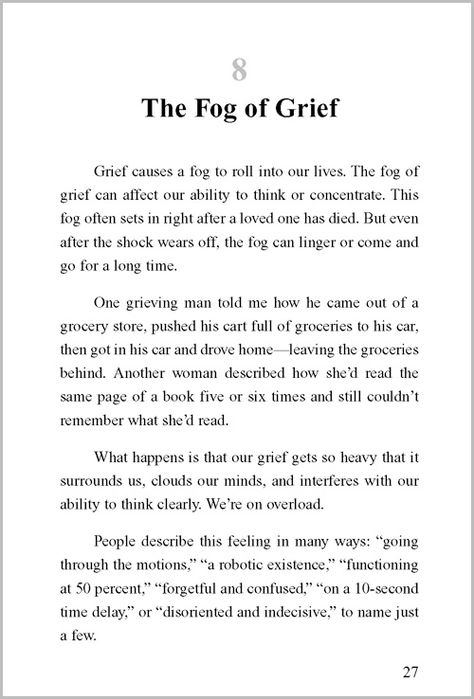

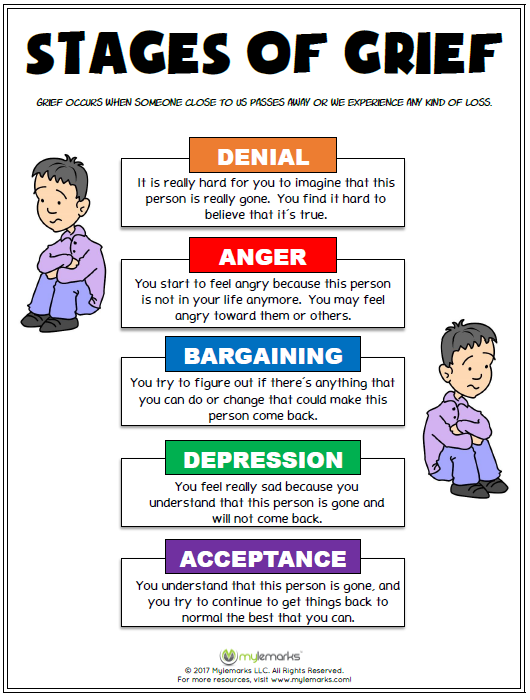

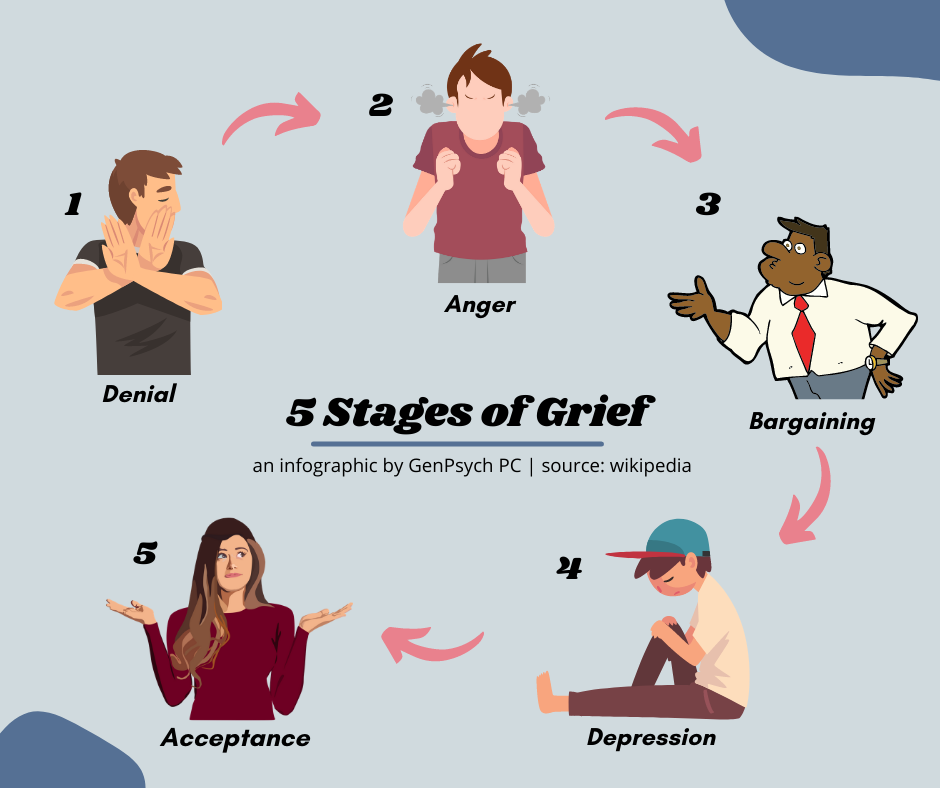

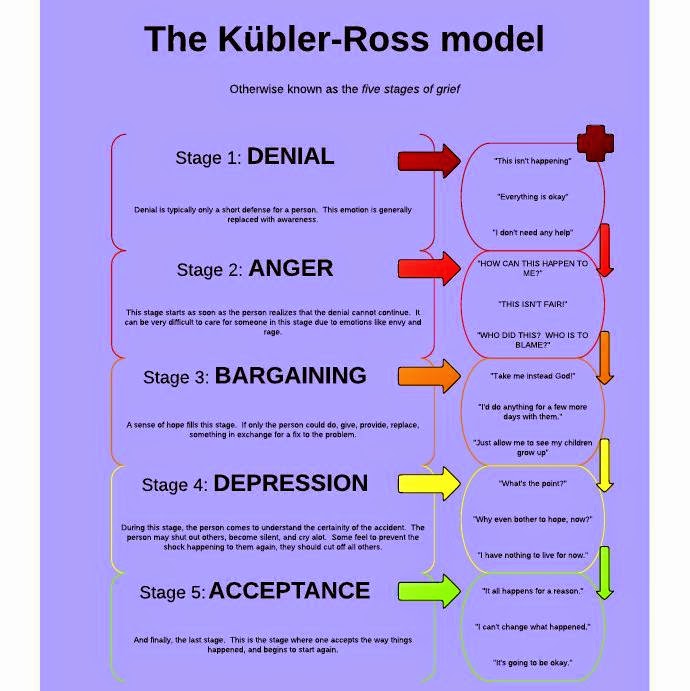

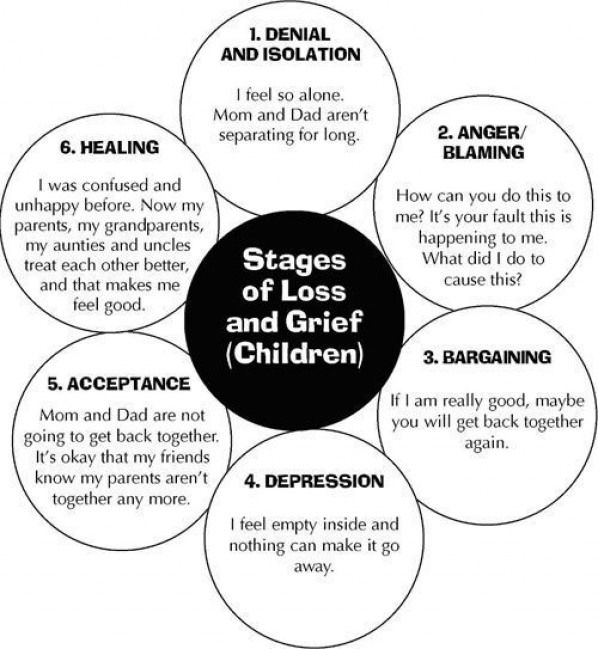

A child's experience of grief, like that of an adult, goes through several stages.

Shock is the very first reaction to death. It can be expressed in silent departure or an attack of tears. The child does not understand what is happening. Trying to distract his attention with something is an unsuccessful strategy. It is much better to express support, understanding, share the pain (hug, let relax, cry, talk about the departed loved one).

Death denial is the next stage of grief. "This can't be happening to me!" - so it can be expressed in words. The child subconsciously cannot believe that a loved one will no longer be there.

search Despair — when the child finally realizes the impossibility of returning the deceased. He again begins to cry, scream, reject the love of other people. Only love and patience can overcome this state. Anger, resentment is expressed in the fact that the child is angry with a loved one who "left" him. "Why me? For what? What is my fault?" - the main ideas of this stage. Small children can start breaking toys, throwing tantrums, pounding on the floor with their feet, a teenager suddenly stops communicating with his mother, “for no reason” beats his younger brother, is rude to the teacher. Anxiety and guilt lead to depression. This is the stage of feeling hopeless, hopeless, despair, bitterness, self-pity. Acceptance stage — the child perceives the loss as an inevitable reality, realizes and comprehends it. Accepts the situation and comes to terms with the loss, whatever it may be. The process of psychological healing and return to normal life begins. How can loved ones help a child? The answer to this question is given by Rosemary Wells in her book, published in London in 1988 (I will quote an excerpt from her book Developmental and Correctional Programs for Working with Primary School Students and Adolescents. Teacher's Book /Ed. I. V. Dubrovina - Moscow-Tula, 1993) 1 . First of all, it is necessary that the experience be shared by all family members. Many agree that mourning is desirable for all family members, including children (maybe except for preschoolers). 2 . The most difficult thing for an adult is to tell a child about the death of a loved one. It's best if someone from your family does it. If this is not possible, then the adult whom the child knows well and whom he trusts should report. At this moment, it is very important to touch the child: take his hands in yours, hug him, take him in your arms. The child must feel that he is still loved and that he will not be rejected. It is also important that the child does not feel guilty about the death of a loved one. 3 . It is desirable that the child talk about his fears, but it is not always easy to encourage him to do so. 4 . When does a child need professional help? Usually parents try to avoid going to a psychiatrist. It also happens the other way around: at the slightest suspicion of the unusual behavior of the child, the parents rush to the doctor, while they need help, not the child. * Be frank but sensitive. Let your body language convey that your child's reaction means a lot to you. “I have very sad news. Grandpa died this morning. * If the children have questions, answer them honestly. Terrible details - should be omitted. “Remember when grandpa had heart surgery? Then he developed pneumonia. * Children will be concerned about your safety, and perhaps their own. If the child asks if he will die, or when you are going to die, then you need to reassure him that you will live long, and he too. “Everyone dies sooner or later. But most people live to a ripe old age. When I die, you will all be adults and live with your children in your own house.” Some children will become too worried about you. They may worry if, for example, you have a cold or you are driving in bad weather. Express empathy to them, and then reassure them by telling them that you always take care of yourself. “You seem to be worried that I might die just like dad. These thoughts scare you. But you and your brother are the most important thing in my life, and therefore you need to know that I take very good care of myself. I always fasten my seat belts and drive very carefully. * "I know how you feel, but Mom would like you to be happy (or eat your dinner)." Any remark indicating to the child that he should not be in such a mood can, at the very least, cause him confusion. In the worst case, the child may feel guilty for not behaving the way a deceased relative would like him to. It’s better to say: “Mom understands that you are sad now. She understands that you don't want to eat. And I understand too. But I'm also sure that mom is waiting for the day when your sadness subsides and you become happier. * "Grandpa is now on an amazing journey that every person embarks on one day." "Grandfather fell asleep forever." Children younger than eight or nine years old think literally, not abstractly. Using other words instead of the words “dead” or “died”, you can confuse the child. He may never want to travel or be afraid to fall asleep. * "Grandma died after she was taken to the hospital." "Grandma died in an accident." Children sometimes end up in the hospital, and something happens to all children sometime. This does not mean that such events are usually followed by death. On the contrary, let your child know that the accident was very serious, and also that injuries and hospitalization usually do not end in death. * “Grandma was sick…” Children are also sick. Confirm that the grandmother was very ill and that the medicines that usually help did not help her because her illness was very serious. * "Don't worry, I'll never die." But how do you explain to a child that dad is dead? It is better to say that you are not going to die to a ripe old age. If a child asks what would happen to him if both mom and dad died, you can explain your plans for providing him with a guardian. At the same time, reassure him that you don't think this is going to happen. * “Two years have already passed since my grandfather died. Everyone has already calmed down, but why are you still upset? The best way to forget is to remember. As contradictory as it may seem, people become better able to take their minds off loss when they have the freedom to remember and mourn for the dead. If you are surprised by the sadness of your child, then it will help you to understand the empathy you expressed. Maybe the sad memories were triggered in the child by the fact that a relative of his friend had died. There are many reasons. Therefore, on the contrary, say: “It is normal that sometimes such sad moments arise in the soul. Igor Savchenko, psychologist The information in this article explains how to help your child after the death of a parent. For any child, the death of a parent is the hardest test. No matter how old your child is, you may want to protect him from the sadness and confusion that you are experiencing. Children, as well as adults, may need help in dealing with loss and adjusting to life after it. Remember that how a child experiences grief depends on their age, understanding of death, and the behavior of others. Young children express their grief differently than adults. While younger children may not fully understand death, adolescents have a more mature understanding of it. Adolescents are at a stage in their lives when their personality, way of thinking and emotions are being formed. After the death of a parent, they can experience a wide range of emotions. Some may feel that their place in the family has changed and take on adult responsibilities. It may be difficult for you to help your child because you yourself are experiencing loss. If you are having trouble communicating with your child, ask for support and help from a family member, friend, social worker, psychologist, or religious or spiritual guide. Here are some ways you can help your child cope with loss. It is natural not to cry in front of your child, but expressing your emotions can serve as an example for your child to cope with difficulties. Share your own feelings about the loss of a loved one. By telling your child how you feel, you will help your child express his feelings as well. If your family holds any religious or spiritual beliefs, it may help to mention your faith in the conversation. When talking about death, avoid phrases such as "gone" or "left". Rituals to honor a loved one can have a calming effect on you and your child. By maintaining old family traditions or creating new ones, you and your family can keep in touch with your loved one. In different cultures and religions, there are rituals to honor someone's memory. Some families have their own rituals, such as getting together and preparing a special meal, planting a garden, visiting favorite places, or celebrating birthdays. Whatever you choose, remember that there is no right or wrong way to honor a loved one. Try to do what will be most comfortable for your family. Whether your child attends a funeral or a farewell ceremony is a decision between you and your child. The opportunity to be present at the funeral will allow the child to experience grief with his family. If your child is attending a funeral, make sure they know what to expect beforehand. You may also want to consider having your child participate in the ceremony. The child can write a letter or draw something and put it in the coffin. He can also make a collage with photos of the parent for the funeral. At the funeral, always remember the child's feelings and check his health. You may want to ask someone your child trusts to occasionally go out with your child for breaks. If the child wants to leave the room, let him do it. After the funeral or farewell ceremony, the child may have new questions about death. Support is available to you and your family, no matter where you are in the world. Talking with Children About Cancer Bereavement Program MSK Counseling Center Spiritual support Books, educational resources and local support programs are available for bereaved parents and children. For more information about these programs, call your social worker or visit www.mskcc.org/experience/patient-support/counseling/talking-with-children/resources The Dougy Center: national center for children and families in grief Red Door Community Books for adults on how to help children and adolescents deal with grief Guiding Your Child Through Grief The Grieving Child: A Parent's Guide Helping Children Cope with the Loss of a Loved One: A Guide for Grown Ups How Do We Tell the Children? A Step-by-Step Guide for Helping Children Two to Teen Cope When Someone Dies Preparing Your Children for Goodbye: A Guidebook for Dying Parents Take My Hand: Guiding Your Child Through Grief Talking about Death: A Dialogue between Parent and Child Books for children about death and grief Always by My Side (Always next to me) Everett Anderson's Goodbye Gentle Willow: A Story for Children about Dying  The final awareness of reality comes, and with it the understanding of loss. The stage of parting with hopes, dreams and plans. Stage of torpor and loss of interest in life. At this stage, teens may have suicidal thoughts.

The final awareness of reality comes, and with it the understanding of loss. The stage of parting with hopes, dreams and plans. Stage of torpor and loss of interest in life. At this stage, teens may have suicidal thoughts.  It is a shared experience that every member of the family understands.

It is a shared experience that every member of the family understands.

Sometimes children become friends precisely on the basis of the similarity of experiences: "Linda and I are friends, because both of us do not have a mother, but only a father."

Grief never goes away. We keep loved ones alive in our memory, and our children really need this. This will allow them to have a positive experience of grief and support them in life.

The child may show an outburst of anger towards an adult who brings sad news. It is not necessary at this moment to persuade the child to pull himself together, because grief that is not experienced in time can return months or years later. Older children prefer loneliness at this moment. Do not argue with them, do not pester them, their behavior is natural and is a kind of psychotherapy.

It is not necessary at this moment to persuade the child to pull himself together, because grief that is not experienced in time can return months or years later. Older children prefer loneliness at this moment. Do not argue with them, do not pester them, their behavior is natural and is a kind of psychotherapy.

The child must be surrounded by physical care: prepare food for him, make a bed, etc. It is not necessary to charge him with adult duties during this period: “You are now a man, do not upset your mother with your tears” (this is sometimes said even to an 8-year-old child) . Holding back tears is unnatural for a baby and even dangerous. But there is no need to make the child cry if he does not want to.

During a period of grief in the family, one should not isolate the child from family worries. All decisions must be made by the whole family.  The needs of the child seem obvious to us, but few adults understand that the child needs recognition of his pain and fears, he needs to express his feelings in connection with the loss of a loved one.

The needs of the child seem obvious to us, but few adults understand that the child needs recognition of his pain and fears, he needs to express his feelings in connection with the loss of a loved one.

It is believed that after the funeral, family life returns to normal: adults return to work, children return to school. It is at this point that the loss becomes most acute. In the first days after the tragedy, children know that any manifestation of feelings is legitimate. As time passes, phenomena such as enuresis, stuttering, nail biting, drowsiness or insomnia may come to replace. It is impossible to give a prescription for each individual case. The main thing is to proceed from the child's need for love and attention to him. If the child refuses to eat, you can offer him to help an adult prepare dinner for the whole family.

How to remove aggressive behavior? Small children can be given various boxes, boxes, balloons, paper that can be crushed, broken and crushed. Older children can be assigned physical work that requires considerable effort, or a long walk or bike ride.

However, one must keep in mind that in a large family, a kind of competition may arise: who expresses his anger more strongly. All of the above does not exclude the fact that a child cannot be allowed to go too far in this ingot. It is impossible to allow one child to be allowed absolutely everything to the detriment of other children.

During many months, even the whole first year, sharp emotional outbursts will overshadow such events as holidays, birthdays. Then the emotional outburst, as a rule, weakens. The loss is not forgotten, but the family learns to manage it.

As alarming symptoms, the following can be distinguished:

- prolonged uncontrollable behavior, acute sensitivity to separation, complete absence of any manifestations of feelings;

- anorexia (refusal of food), insomnia and hallucinations (all of which are more common in adolescents).

Adolescent depression is often anger driven inwards.

General advice: Delayed grief, prolonged or unusual anxiety is alarming. Always disturbing lack of experiences. In these cases, it is worth consulting a psychologist.

Separately, it is necessary to discuss the question: how to talk with a child about the death of a loved one? Recommendations on this subject are given by the famous psychologist Paul Coleman (Coleman P. How to tell a child about ... / Translated from English by O. Tsvetkova. _ M: Publishing House of the Institute of Psychotherapy, 2002.)

How to say  Pneumonia is usually treated, but grandfather was so weak that the drugs did not help, and he died.”

Pneumonia is usually treated, but grandfather was so weak that the drugs did not help, and he died.”  ”

”

Reassure the children by reminding them of other times when they were worried but everything was going well. “Remember how you worried last week when I needed to take antibiotics for bronchitis? But I got better, didn’t I?”

Report your own feelings when you see that the child is sad, but does not tell you anything. “We are having lunch, but mother is not with us. I miss her too."

Most young children are unable to attend wakes and funerals. Decide for yourself whether to take them there with you or not. If they are frightened by the fact that they will see the deceased, then explain to them that mainly adults are present at the funeral, and children do not have to go there. Perhaps it will be useful to conduct a ritual with children: send a balloon “to heaven” or write a short letter to the deceased and burn it. If your child is going to attend a funeral, explain what they will see: “Daddy will be in the coffin. His hands will be folded on his chest. Perhaps he will not look the same as you remember him, because when a person dies, his appearance changes somewhat. Everyone wants to stand in front of the coffin and say farewell to the pope. If you want, you can do it too.” Let your child know how much time you have to spend in the funeral parlour.

Everyone wants to stand in front of the coffin and say farewell to the pope. If you want, you can do it too.” Let your child know how much time you have to spend in the funeral parlour.

If your child sees you crying or getting upset even after a month, then don't pretend that everything is fine with you. “I thought about my grandmother, and I became very sad. Sometimes I really miss her.”

How NOT to say  And she knows that it takes time.”

And she knows that it takes time.”

What exactly made you so sad?”

What exactly made you so sad?”

Recovery after the death of a loved one can take time. Children recover faster if people who care about them know how to support them, meet their needs, know how to comfort and calm, and also are always ready to listen. How to help your child after the death of a parent

Understanding a child's grief

Grief in young children

After the death of a parent, they may have short and strong emotional outbursts. In addition, they may experience physical reactions, such as pain in the body or changes in sleep patterns. Some children may express grief through changes in their behavior. They may have difficulty completing daily tasks or behave in ways they have never behaved before. They may grieve for short periods of time with breaks in between. For example, a child may cry or appear sad, and shortly thereafter ask to go for a walk or start playing. Other children may not show any signs of sadness or grief.

After the death of a parent, they may have short and strong emotional outbursts. In addition, they may experience physical reactions, such as pain in the body or changes in sleep patterns. Some children may express grief through changes in their behavior. They may have difficulty completing daily tasks or behave in ways they have never behaved before. They may grieve for short periods of time with breaks in between. For example, a child may cry or appear sad, and shortly thereafter ask to go for a walk or start playing. Other children may not show any signs of sadness or grief. Adolescents experience grief

Adolescents may need privacy to grieve. Let your child know that they can talk to you and ask for support.

Adolescents may need privacy to grieve. Let your child know that they can talk to you and ask for support. How to help your child

Share your own thoughts and feelings

Talk about death directly

This can mislead the child and make them think that their parent will soon wake up or return. Honesty and directness will help your child understand what happened and learn how to deal with grief. Some families use religious or spiritual beliefs to help the child understand that the parent is not physically present. If you think this might be helpful, ask a religious or spiritual guide for help.

This can mislead the child and make them think that their parent will soon wake up or return. Honesty and directness will help your child understand what happened and learn how to deal with grief. Some families use religious or spiritual beliefs to help the child understand that the parent is not physically present. If you think this might be helpful, ask a religious or spiritual guide for help. Honor the memory of the deceased

Funeral participation

Resources for you and your family

MSK resources

Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) offers a range of resources for grieving families and their friends. You can learn more about these resources at www.mskcc.org/experience/caregivers-support/support-grieving-family-friends

Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) offers a range of resources for grieving families and their friends. You can learn more about these resources at www.mskcc.org/experience/caregivers-support/support-grieving-family-friends

Talking about Cancer with Kids is a program designed to support parents undergoing cancer treatment in raising their children and teens. Our social workers offer family support groups, individual and group counseling, access to resources, and guidance for professionals including school social workers, school psychologists, counselors, teachers, and other staff. For more information, visit www.mskcc.org/experience/patient-support/counseling/talking-with-children

646-888-4889

MSK offers services through the Bereavement Program to help bereaved family members and friends. People who have lost a loved one to cancer may find it helpful to talk to other grieving people. The Departments of Social Work, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Sciences offer support groups and educational programs for people who have lost a loved one to cancer. Services include short courses of individual counseling, resources for bereaved children, adult groups, and access to local resources.

The Departments of Social Work, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Sciences offer support groups and educational programs for people who have lost a loved one to cancer. Services include short courses of individual counseling, resources for bereaved children, adult groups, and access to local resources.

For more information or to join a bereavement support group, call Social Work at 646-888-4889.

646-888-0200

Some bereaved families find they have benefited from expert advice. Our psychiatrists and psychologists work at the bereavement clinic, where they provide counseling and support for individuals, couples and families, and can prescribe medications to help manage depression.

212-639-5982

Our chaplains are ready to listen and support family members, pray, reach out to local clergy or religious groups, simply offer comfort and extend a spiritual helping hand. Any person can apply for spiritual support, regardless of their formal religious affiliation.

Additional resources

Useful websites

www.dougy.org

The Dougy Center provides support for grieving children, teens, young adults and families. The Center provides online resources and programs to support and assist families in grief.

212-647-9700

www.reddoorcommunity.org

Provides meeting places for people living with cancer and their family and friends. Enables people to meet each other to build systems of mutual support. Provides free assistance and organizes communication groups, lectures, seminars and social events. The Red Door Community used to be called Gilda's Club.

The Red Door Community used to be called Gilda's Club. Useful literature

By James P. Emswiler

Author: Helen Fitzgerald

Author: William C. Kroen

By Dan Schaefer and Christine Lyons

Author: Lori Hedderman

Author: Sharon Marshall

By Earl A. Grollman

For children aged 4 to 8

Author: Susan Kerner

For children aged 5 to 8

Author: Lucille Clifton

For children aged 4 to 8

Author: Joyce C.