How to handle an out of control child

How to Stop the Family Anxiety Cycle

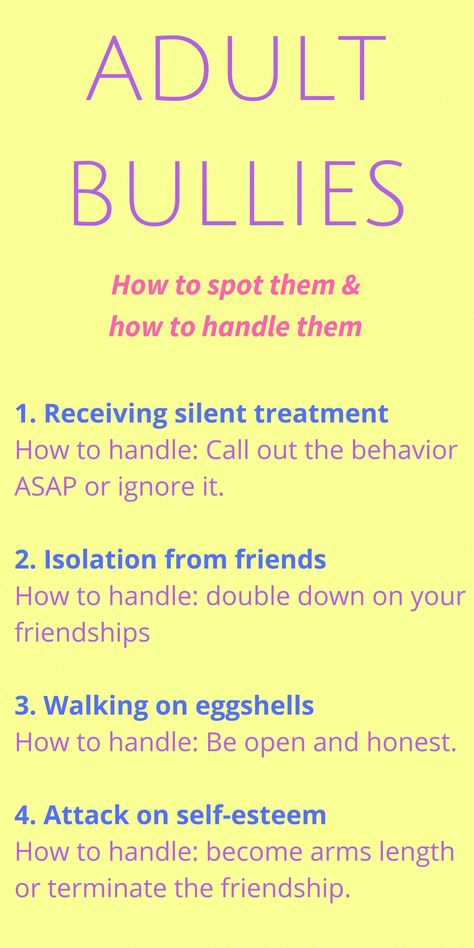

Does your child’s behavior make you feel out of control? Do you find yourself walking on eggshells so that you don’t “set him off?” It might be your five year old who has tantrums and acts out, or perhaps it’s your teenager who fights with you all the time.

Your consequences mean nothing to him, and in fact seem to make him more defiant. Whatever the reason, you’ve got the kid who simply doesn’t react to parenting the way you thought he would.

Debbie Pincus, creator of the Calm Parent: AM & PM, explains how you can change the way your family interacts.

When a child becomes the “anxiety sponge” for the family he or she will often develop some problems.

If you have a “problem” child, you are not alone. Many families struggle with difficult, acting-out kids who act like nothing matters to them, which in turn leaves you feeling baffled and lost. You lose sleep most nights wondering, “How did my family get here? What’s going on and how can we change things so our lives aren’t a battle zone?”

While there are many helpful techniques parents can use with their kids—in fact, Empowering Parents is full of articles that will help you parent more effectively—I’d like to view this problem from a slightly different angle today. So let’s step back and look at the big picture: What really happens when a kid acts out chronically in a family and the attention all goes to them? And how can parents turn this around?

The Big Picture

In order to turn things around with your child, I believe it’s helpful to widen the lenses that we use to view our difficult kids. Let’s say you’re focused on your acting-out child—attempting to fix and change him—only to find that his behavior is worsening. (Or perhaps it changes, but only temporarily.) To a certain extent this happens because you’re looking at your child as the “problem” rather than seeing the way the family operates as a whole.

When you can see your family in this new way you’ll recognize that your child is only part of this unit—a fragment of the whole.

What do I mean by this? Think of it this way: Each family member is only a part of the larger group. Children with problem behaviors are rarely the underlying problem, though some kids are more defiant and rebellious from the start, and therefore more difficult to parent. They may come this way, genetically predisposed to act out more and be rebellious.

They may come this way, genetically predisposed to act out more and be rebellious.

As a result of their difficult behavior, you naturally begin to focus on them. For the most part, kids who act out are symptoms of something much larger—often, it’s an emotional or relationship problem. This does not lay the blame on anyone; it simply means every member of the family group is a contributor in some way.

I believe that if you want to go about changing the problem, you need to get the focus off the “symptomatic” one and instead onto the relationship patterns in the family. I also want to add here that if this is going on in your family, it’s not too late: it’s possible to change your family’s pattern no matter what stage you’re in with your child.

Let’s consider how anxiety travels in a group of people. If Dad comes home from work upset about a deal that didn’t go through, he may automatically take it out on Mom by criticizing her about the messy house. Mom may react to this by shutting down or defending herself, but either way the anxiety has moved to Mom. Next Jack, the two-year-old, seeing or feeling Mom’s distress, starts crying. The anxiety has moved to him. Now Chloe, the six-year-old, experiences this emotional intensity and feels uncomfortable and upset. She runs to her room and starts yelling and acting out.

Next Jack, the two-year-old, seeing or feeling Mom’s distress, starts crying. The anxiety has moved to him. Now Chloe, the six-year-old, experiences this emotional intensity and feels uncomfortable and upset. She runs to her room and starts yelling and acting out.

In this way, anxiety moves from person to person in a family unit. This is a natural and automatic response. Most of the time, rather than disturbing everybody in the family, anxiety seems to settle in one person—often a child. In the family just described, the original anxiety exchange was between the two parents. If they don’t get it worked out over time, the six year old might continue to react to the intensity by acting out more and more—and the adults will begin to focus on her. Not realizing that their child’s response is an expression of anxiety that came from the family unit, they may come to see her as the problem and begin worrying about her. The more she is fretted over, the more anxious and symptomatic she will become—and the more symptomatic she becomes, the more focused they will become on her. The cycle has now been set in motion.

The cycle has now been set in motion.

When a child becomes the “anxiety sponge” for the family he or she will often develop some problems. If the adults put the focus on the child and not on themselves, they never get to resolve their own problems or ineffective patterns—instead, the over-focused child will develop problems. Take into account that when anxiety collects in a person, their brain and body chemistry becomes changed. As a result, the child may show hyperactivity, learning issues, or behavioral or social symptoms. Once a disorder develops, more and more intense focus is drawn to their problems at home and at school. It becomes a vicious cycle that’s hard to stop.

This snowball effect can start simply: Let’s say every time a mother is upset, she offloads her stress by complaining loudly. The father shuts down and withdraws and then the child picks up on his distress. Kids are very tuned in. If you have a child who’s particularly vulnerable to moods, he might absorb or take on the stress and become the sponge. You’ll see him becoming anxious in some way; he’ll be the one with the “symptoms.” While there’s no one to blame for this, it’s ultimately our responsibility as parents to keep an eye out and not let our stuff spill onto our kids.

You’ll see him becoming anxious in some way; he’ll be the one with the “symptoms.” While there’s no one to blame for this, it’s ultimately our responsibility as parents to keep an eye out and not let our stuff spill onto our kids.

How to Stop the Cycle

If you see this cycle happening in your family, the first thing to do is recognize it for what it is. Stop it by taking the intense focus off your acting-out child and pay more attention to yourself and your relationship patterns. Ask yourself some hard questions, like the following: “By putting so much focus on my child, what do I get to avoid in myself and in my own adult relationships?” Consider what he might be expressing through his behavior. Are these expressions of tension in the family, or ineffective relationship patterns that need more attention paid to them?

Remember that your family, not your child, is the emotional unit. This will help you see that you are a part of the problem, and also part of the solution. Work to change what is under your control instead of worrying, over-focusing and trying to control your child. If you begin to see that your child is the symptom-bearer of the family unit rather than a “problem child,” you’ll be more understanding and empathetic rather than angry and frustrated. Don’t get me wrong, you still need to hold him accountable for his poor behavior. But now, instead of seeing him as “broken” or the problem, you’ll hold him to higher expectations.

Work to change what is under your control instead of worrying, over-focusing and trying to control your child. If you begin to see that your child is the symptom-bearer of the family unit rather than a “problem child,” you’ll be more understanding and empathetic rather than angry and frustrated. Don’t get me wrong, you still need to hold him accountable for his poor behavior. But now, instead of seeing him as “broken” or the problem, you’ll hold him to higher expectations.

Don’t get me wrong, when our kids are acting out, we need to hold them accountable rather than anxiously focus and fret about them. What’s the difference between anxious parenting versus being parental? Being responsible and standing our ground is being parental, because we’re doing what our child needs to guide him to a better place. Anxious parenting happens when our emotionality slips in and we start reacting to our child rather than responding to his behavior thoughtfully, and most of the time we don’t even realize we’re doing it.

Pause and ask yourself some important questions.

- Why aren’t I taking a firmer stand right now when I know that would be best?

(Do I want him to like me or validate me? Or am I just trying to contain my child’s anger so my husband doesn’t get mad at him or me?) - Am I acting from my best principles that might cause some short-term pain for some longer-term gain?

- Is the consequence I’m giving my child right now actually a disguised punishment to get back at them for their awful behavior? (Is this really the best way or does it just feel good in the moment because it relieves my distress?)

- Am I afraid to discuss some issues with my spouse? To avoid each other do we instead deflect onto our kids? Are they getting caught in the middle and acting out this adult tension?

Most of the time we think we’re being thoughtful in our responses to our acting-out kids but often we’re actually being reactive, adding fuel to the already hot inferno.

What Can Parents Do?

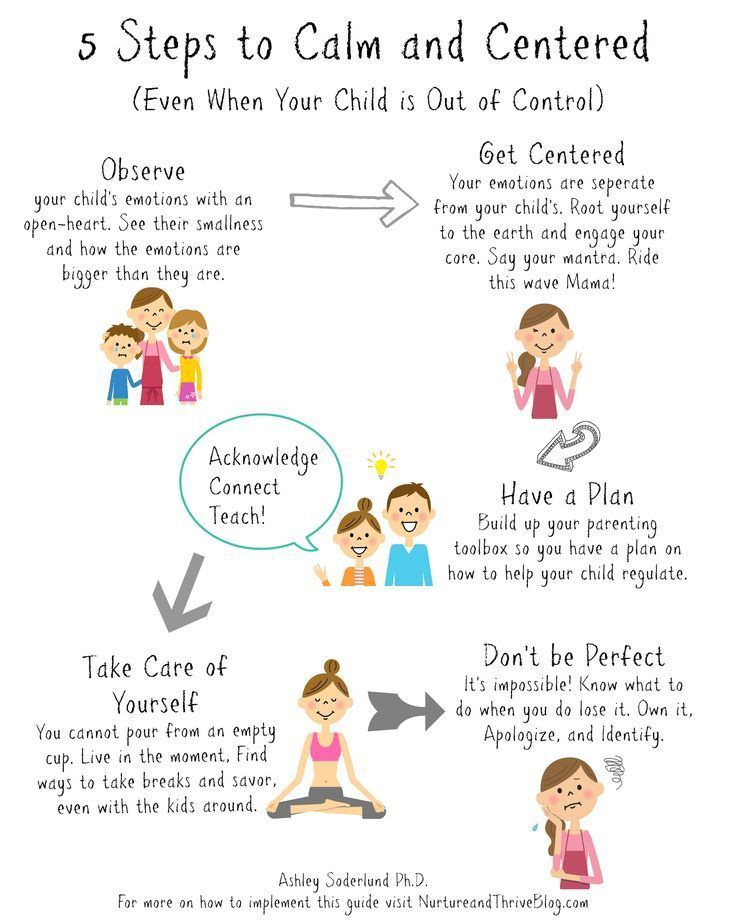

Take care of yourself. Take care of yourself emotionally and physically, so your children don’t end up with that job. Pay attention to and attend to your adult relationships. Instead of being irritable and upset, say what’s on your mind. Resolve issues so that your unresolved anxieties don’t get spilled on to your kids.

Observe. Observe yourself and your relationship patterns: your own thinking, feelings and behavior. See how your family’s (both nuclear and extended) emotional pressures contribute in producing your child’s negative behavior. Consider what’s going on from wider lenses. See the whole family drama.

Set limits and give enforceable consequences. If your child is acting out, set limits and give him enforceable consequences. Take charge, not control. Be parental; don’t parent with an “anxious focus” on your child.

Recognize your own contribution. Start with yourself and go from there. After all, you’re the only one you really have control over in life. Look at what’s in your hands, not what’s not in your child’s hands. Watch what you’re doing and try to be as clear and direct as possible. You’re not responsible for your child’s outcome and you’re not the cause of the problems. If you can look at your contribution then you can change that part of yourself that’s adding to the cycle of anxiety and bad behavior.

After all, you’re the only one you really have control over in life. Look at what’s in your hands, not what’s not in your child’s hands. Watch what you’re doing and try to be as clear and direct as possible. You’re not responsible for your child’s outcome and you’re not the cause of the problems. If you can look at your contribution then you can change that part of yourself that’s adding to the cycle of anxiety and bad behavior.

Try to parent from your principles, rather than from your deepest anxieties. By understanding how your family operates—and how anxiety operates in your family—you can use your principles to guide your thinking and responses. This will help to stop the reactivity that often gets moved from one family member to the next. Your principles, rather than your anxieties, will lead the way. And when you see your child as separate from you, you will also see yourself more clearly and more objectively.

Related Content:

Calm Parenting: How to Get Control When Your Child Makes You Angry

Losing Your Temper with Your Child? 8 Steps to Help You Stay in Control

Out Of Control Kids: This Is The #1 Mistake Parents Make When Arguing With Kids

How do you deal with out of control kids?

The authors of the bestseller How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk have some great ideas that can help any parent. It’s really powerful, impressive advice.

It’s really powerful, impressive advice.

But here’s the odd thing: reading the book, I could have swore I had seen similar ideas before. And I had…

When I was interviewing and researching FBI hostage negotiators.

No, your 9-year-old Jimmy probably isn’t committing serious acts of violence (except maybe against his sister) and your teenager Debbie probably isn’t going barricade (except maybe in her room with the music on full blast) but many of the principles that are effective for dealing with terrorists, bank robbers and evildoers will also work with your children.

Seriously, these fundamental principles of communication can help you deal with anyone. So let’s see what parenting experts and hostage negotiators can teach us, and how it can make for a more peaceful, happier home.

Most importantly, parents often make a mistake at the beginning of their arguments with kids that no hostage negotiator would ever make. And when a conversation starts badly, it’s often downhill from there.

What’s this error?

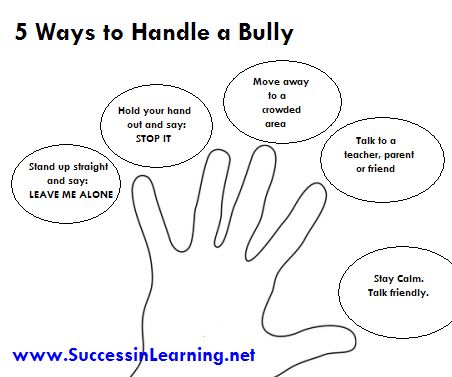

Don’t Deny Their Feelings

The FBI has the bank surrounded. But the robbers have taken hostages. It’s a tense standoff and the bad guys are demanding food be sent in. They say they’re hungry.

The hostage negotiator lifts the phone and says, “Oh, stop it. You just ate. Quit complaining and just cut it out!”

Um, no. An FBI negotiator would never do that. But parents do it with their kids all the time. And the result is often more screaming, more tears, and more hysteria. What’s the problem here?

Denying their feelings.

Now as a parent you can’t be overly permissive and give a kid everything they want. But a hostage negotiator wouldn’t do that either — maybe the bad guys get the food when they ask for it and maybe they don’t. But negotiators wouldn’t say, “You’re not hungry. Cut it out!”

Of course, parents have to deny actions (“No, Billy, we should not see what happens if we use the weedwacker in the living room. ”) But parents often take it a step further and deny what a child is feeling.

”) But parents often take it a step further and deny what a child is feeling.

Human beings don’t like this. I don’t like this. You don’t like this. What’s the typical reaction when you tell an angry person to calm down? “I AM CALM!!!”

And that’s an adult. Do you expect a kid to have more control over their emotions than a full grown person? I didn’t think so.

(For more tips from FBI hostage negotiators on how to get what you want, click here.)

So what’s the right way to start the conversation? Here’s what parenting experts and hostage negotiators agree on…

1) Listen With Full Attention

The child is crying and you’re at your breaking point. It’s easy to reply with something like this:

From How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk:

- “Your retainer can’t hurt that much. After all the money we’ve invested in your mouth, you’ll wear that thing whether you like it or not!”

- “What are you talking about? You had a wonderful party— ice cream, birthday cake, balloons.

Well, that’s the last party you’ll ever have!”

Well, that’s the last party you’ll ever have!” - “You have no right to be mad at the coach. It’s your fault. You should have been on time.”

But denying their feelings like this typically escalates situations.

Think about arguments with your partner. They say, “I feel ignored.” You reply with, “No, you’re not.” How well is that going to go? Exactly. And it’s no different with kids. When people deny our feelings we naturally fight back.

So start with listening. You feel better when people listen to you and it’s the same for kids.

From How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk:

…let someone really listen, let someone acknowledge my inner pain and give me a chance to talk more about what’s troubling me, and I begin to feel less upset, less confused, more able to cope with my feelings and my problem… The process is no different for our children. They too can help themselves if they have a listening ear and an empathic response.

And hostage negotiators agree. The FBI uses what they call the “behavioral change stairway.” And listening is always the first step:

Former FBI Lead International Hostage Negotiator Chris Voss explains the power of listening:

If while you’re making your argument, the only time the other side is silent is because they’re thinking about their own argument, they’ve got a voice in their head that’s talking to them. They’re not listening to you. When they’re making their argument to you, you’re thinking about your argument, that’s the voice in your head that’s talking to you. So it’s very much like dealing with a schizophrenic. If your first objective in the negotiation, instead of making your argument, is to hear the other side out, that’s the only way you can quiet the voice in the other guy’s mind. But most people don’t do that. They don’t walk into a negotiation wanting to hear what the other side has to say. They walk into a negotiation wanting to make an argument.

They don’t pay attention to emotions and they don’t listen.

(To learn the 4 new parenting tips that will make your kids awesome, click here.)

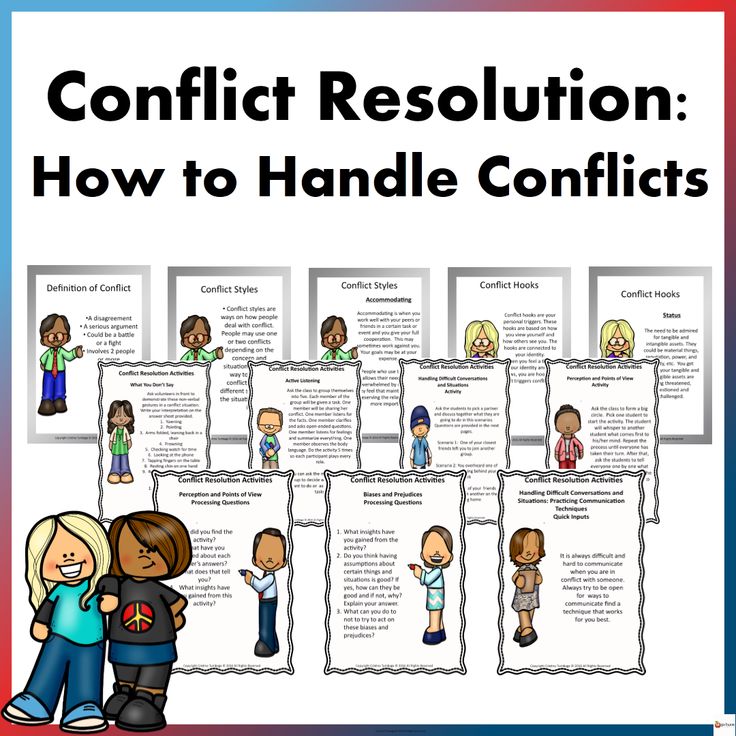

You may notice that the term in that image is actually “active listening.” What’s the active part? That brings us to step 2…

2) Acknowledge Their Feelings

“I know how you feel.”

Don’t say that. When people are emotional and hear, “I know how you feel” they think you’re trying to shut them up. Or they snap back, “No, you don’t.”

Instead of saying you understand, show them you understand. It’s the difference between someone saying to you, “I’m funny” vs. them making you laugh for 30 minutes straight.

So how do you show them you’re listening? FBI hostage negotiators use “paraphrasing.” It’s simple: repeat back to them what they said in your own words. From my interview with Chris Voss:

The idea is to really listen to what the other side is saying and feed it back to them.

It’s kind of a discovery process for both sides. First of all, you’re trying to discover what’s important to them, and secondly, you’re trying to help them hear what they’re saying to find out if what they are saying makes sense to them.

Some parents might say, “But what my teenager is saying is crazy!”

You don’t have to agree with the feelings but acknowledging them is what gets kids (or anyone) to say to themselves, “This person understands me.” And then they can start to see you as being on their side, which is the first step in resolving problems.

FBI behavioral expert Robin Dreeke explains:

The number one strategy I constantly keep in the forefront of my mind with everyone I talk to is non-judgmental validation. Seek someone else’s thoughts and opinions without judging them. People do not want to be judged in any thought or opinion that they have or in any action that they take. It doesn’t mean you agree with someone.

Validation is taking the time to understand what their needs, wants, dreams and aspirations are.

But parents often don’t do this. They launch immediately into advice and lecturing. Clinical psychologists say you can’t do this when arguments are still heated.

And neuroscientists agree. When we deny people’s feelings, the logical parts of their brain literally shut down.

From Compelling People: The Hidden Qualities That Make Us Influential:

When an argument starts, persuasion stops… So what happened in people’s brains when they saw information that contradicted their worldview in a charged political environment? As soon as they recognized the video clips as being in conflict with their worldview, the parts of the brain that handle reason and logic went dormant. And the parts of the brain that handle hostile attacks — the fight-or-flight response — lit up.

And there’s another problem with immediately trying to resolve the argument with a lecture: you don’t give your kid a chance to work the problem out themselves.

From How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk:

When we give children advice or instant solutions, we deprive them of the experience that comes from wrestling with their own problems.

Hostage negotiator Chris Voss says that when you demand people act a certain way, you threaten their autonomy — and so they naturally resist. When you let them arrive at a solution on their own (or with gentle guiding) they’re more likely to comply.

Now this doesn’t mean that everything a child says is okay. You’re still the parent, after all. When kids push the limits and say things like “I hate you!” it’s alright to draw a line.

From How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk:

If “I hate you” upsets you, you might want to let your child know, “I didn’t like what I just heard. If you’re angry about something, tell it to me in another way.

Then maybe I can be helpful.”

(To learn how to win every argument, click here.)

So you’re letting them talk and you’re actively listening. What’s the first step in getting them to calm down?

3) Give Their Feelings A Name

“Labeling” is very powerful. Seeing a child’s anger and simply saying, “Sounds like you’re really angry” can actually make a big difference.

But parents are often reluctant to do this. The parenting experts explain:

Parents don’t usually give this kind of response, because they fear that by giving a name to the feeling they’ll make it worse. Just the opposite is true. The child who hears the words for what she is experiencing is deeply comforted. Someone has acknowledged her inner experience.

(Don’t worry about using the wrong label. Trust me, they’ll correct you. But it still shows you are trying to understand them.)

FBI hostage negotiators feel labeling is one of their most powerful techniques.

Via Crisis Negotiations, Fourth Edition: Managing Critical Incidents and Hostage Situations in Law Enforcement and Corrections:

A good use of emotional labeling would be “You sound pretty hurt about being left. It doesn’t seem fair.” because it recognizes the feelings without judging them. It is a good Additive Empathetic response because it identifies the hurt that underlies the anger the woman feels and adds the idea of justice to the actor’s message, an idea that can lead to other ways of getting justice. A poor response would be “You don’t need to feel that way. If he was messing around on you, he was not worth the energy.” It is judgmental. It tells the subject how not to feel. It minimizes the subject’s feelings, which are a major part of who she is. It is Subtractive Empathy.

And neuroscience research validates that merely putting a label on things helps calm the brain.

From The Upward Spiral:

…in one fMRI study, appropriately titled “Putting Feelings into Words” participants viewed pictures of people with emotional facial expressions.

Predictably, each participant’s amygdala activated to the emotions in the picture. But when they were asked to name the emotion, the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activated and reduced the emotional amygdala reactivity. In other words, consciously recognizing the emotions reduced their impact.

(To learn the 4 rituals that neuroscience says will make you and your family happier, click here.)

So the shouting and crying have subsided a bit. What’s the next step?

4) Ask Questions

With adults, clinical psychologist Al Bernstein recommends asking, “What would you like me to do?”

Once you get the person to stop yelling, you say, “What would you like me to do?” The person has to stop and think at that point. What you want is to move an angry situation toward the possibility of negotiating. You can do that by simply asking, “What would you like me to do?” It moves them from their dinosaur brain to their cortex, and then negotiating is possible.

FBI hostage negotiator Chris Voss takes a similar approach, using a question to make sure you don’t threaten their autonomy.

Now as a parent you know that you can’t always give kids what they want. Sometimes all you can do is let them know that you understand and you’re on their side.

But the mistake parents make is trying to be too logical. This gets away from feelings and turns things into an extended debate.

From How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk:

When children want something they can’t have, adults usually respond with logical explanations of why they can’t have it. Often, the harder we explain, the harder they protest. Sometimes just having someone understand how much you want something makes reality easier to bear.

After listening, acknowledging feelings and labeling, they’ll be calmer. Often, that’s all it takes to be able to reason with them.

But if it’s still a struggle, you want to use this calm to find a way to discover and address the child’s underlying emotional need (“I don’t feel like you trust me”) instead of logically denying unreasonable demands (“I want to stay out until 2AM. ”)

”)

(To learn FBI behavioral techniques for how to get people to like you, click here.)

Okay, we’ve covered a bunch of good stuff. Let’s round it all up and see how this can work for everyone in your life…

Sum Up

Here’s what parenting specialists and FBI hostage negotiators say can help you deal with out of control kids:

- Listen With Full Attention: Everyone needs to feel understood. The big mistake is thinking kids are any different.

- Acknowledge Their Feelings: Paraphrase what they said. Don’t say you understand, show them you do.

- Give Their Feelings A Name: “Sounds like you feel this is unfair.” It calms the brain.

- Ask Questions: You want to resolve their underlying emotional needs, not get into a logical debate.

Certainly there are going to be situations where you don’t always have the time (or the patience) to go through all the steps. It’s not easy. But by listening and focusing on feelings you can make a big difference.

It’s not easy. But by listening and focusing on feelings you can make a big difference.

And these principles can work with everyone in your life. Most human needs and feelings are universal.

In fact, clinical psychologist Al Bernstein recommends talking to every angry person like they’re a child:

People say to me all the time, “You mean I have to treat a grown-up like a three-year-old?” I say, “Yes, absolutely.”

Feelings are messy and so we avoid them. But when it comes to the ones we love we often forget that, in the end, feelings are really all that matter.

Join over 220,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

How To Get People To Like You: 7 Ways From An FBI Behavior Expert

New Neuroscience Reveals 4 Rituals That Will Make You Happy

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful

An out-of-control child: who is to blame and what to do

Children's tantrums, especially in crowded public places, make parents dumbfounded. And it doesn’t matter if your child is rebelling or someone else’s: such a spectacle causes discomfort for everyone around. Why did the baby become uncontrollable? What led to this behavior? What should parents do in a difficult situation? Children's analytical psychotherapist Olga Novichkova answers questions.

And it doesn’t matter if your child is rebelling or someone else’s: such a spectacle causes discomfort for everyone around. Why did the baby become uncontrollable? What led to this behavior? What should parents do in a difficult situation? Children's analytical psychotherapist Olga Novichkova answers questions.

An unruly child does not obey the rules and regulations, resists the requests of adults, does not agree with the parents. Why is this happening? The behavior of a preschooler who protests strongly, not being able (or having no desire) to control his behavior, begins at an earlier age, at the first clash of the child's interests and his teaching of the rules.

Development of the psyche: where is the beginning of the formation of disobedience?

For the first time, a parent encounters a child's rebellion as early as 1-2 years old, when parental requests and rules suddenly begin to be denied by the baby. The child reacts with a violent rejection of the parent's instructions, although until recently he was obedient and "problem-free". Such a rebellion is necessary: it forms the rudiments of one's own opinion and is part of an important stage in the development of the personality - separation from the mother.

Such a rebellion is necessary: it forms the rudiments of one's own opinion and is part of an important stage in the development of the personality - separation from the mother.

Later, at about 2–3 years old, children first show tantrums and the motto “I myself!”. The child cries, screams, vigorously insists on his own and refuses any actions of the parent. At the same time, the desire to do something on their own is combined with disappointment in case of failure, sometimes a feeling of helplessness.

Important: a small person screams, loudly and strongly expresses his opinion, but he is not able to stop on his own, let alone analyze his behavior. He is absorbed in the process, not the goal and its achievement.

The frontal parts of the brain are responsible for self-control, which fully develop only by the age of 12-15, and the pace of their development is individual. We can say that in early childhood they are not sufficiently developed for self-regulation of behavior. Therefore, the presence of a calm adult helps the child in such cases. Only he can calm the rebel, gently insisting on his rules without aggression, which will help him cope with a rush of emotions.

Therefore, the presence of a calm adult helps the child in such cases. Only he can calm the rebel, gently insisting on his rules without aggression, which will help him cope with a rush of emotions.

When to start learning about the rules

From the age of 2-3, there comes a time when it is important for a parent to start and maintain upholding their rules of conduct in society (family is also a society). The rules must be mandatory. Only their observance should be achieved without suppressing the child, without aggression against him. These should be norms known to the child in advance, on which the adult insists, without changing their obligatoriness, depending on, for example, his mood. Thus, the foundation is laid for the child's ability to internally control his own behavior, and the behavior of the parents themselves forms a model of internal attitude to the rules.

The parental strategy of “not paying attention to hysterics” is dangerous: it leads to the fact that the child does not develop understanding and awareness of the rules, norms, and morality.

In children who do not face restrictions, who meet only indulgence from their parents with the complete absence of the need to follow the rules, great anxiety grows: after all, the rules exist so that the little person feels under the protection of a strong (and proven authority) ) adult.

Otherwise, the uncontrollable and unrestrained behavior of a child at an older age (preschooler) will be directed to a protracted clarification of the question of power - who will win whom in the battle "I want".

In other words, if a preschool child is not able to control his behavior in matters of rules and norms, this signals that he cannot keep his behavioral impulse. If by the age of 4 (and even more so at the senior preschool age) in the child’s behavior one can notice a refusal to cooperate with another adult, for example, a teacher, a doctor, this indicates that in the relationship in the first couple in a person’s life “parent-child” there is dissonance. And by this age, it is time to solve the issue of power in her, and the protracted uncontrollable behavior signals that this did not happen.

The importance of the figure of the father

The father helps the child solve important questions about power and obedience to rules. Through respect in this couple, submission to the strong will of the parent in one and having the opportunity to “get” the manifestation of their initiative and desires in something else, the boundaries of behavior are formed in the mind of the child. During this period, fear in relation to one's father is not some kind of deviation or violation (if it passes by school age). It is the father who shows the child who is in charge in their couple, and relations with him form respect for the rules.

In single-parent families, this issue is more difficult to solve, since the mother cannot simultaneously perform both parental functions. But the psyche of a child is much more flexible than an adult, and he can at least partially make up for the absence of his father with the help of other men in his close circle, for example, grandfather.

Thus, the uncontrollable behavior of children is mainly related to their attitude to the rules - the baby must learn whether they can be broken and what will happen if they are not observed. Much here depends on the parental reaction to the manifestations of the child.

The calm, firm and respectful attitude of a parent to the implementation of the rules, respect for the boundaries helps to naturally form within the child the norms of behavior and morality.

What else can make a child uncontrollable

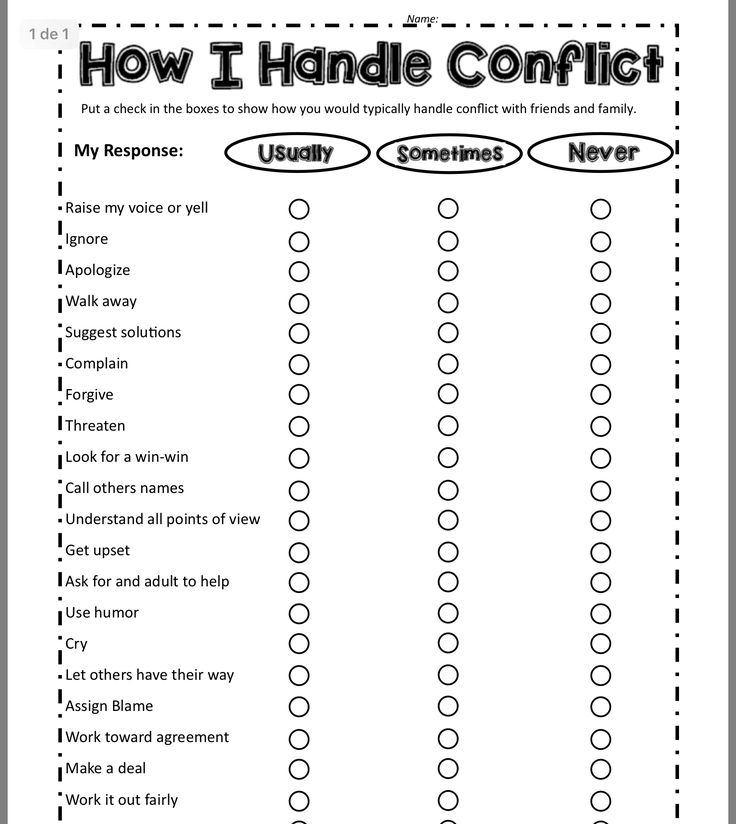

- Behavior of parents. For example, if the parents themselves are often not restrained, prone to screaming and manifestations of tantrums. The child sees an example to follow and sincerely does not understand why parents can, but he cannot behave intemperately. In addition, this creates anxiety in the child: he is left alone with his feelings and affects and loses control and self-regulation even faster.

- Excessive control of parents with a strong-willed character in a child.

In this case, with the help of tantrums and disobedience, a check of the boundaries of what is permitted, a rebellion against the suppression of the independence of a small and strong person can be expressed.

In this case, with the help of tantrums and disobedience, a check of the boundaries of what is permitted, a rebellion against the suppression of the independence of a small and strong person can be expressed. - Serious traumatic history in early childhood. The great grief that the child coped with, having gathered all his mental strength and spending part of his energy on his own development, can make itself felt and cause a wave of aggression and tantrums. At first glance, rebellion is directed at boundaries and rules, but deep down it is a consequence of great anxiety and the inability to lean on someone. This scenario occurs in families with adopted children.

How to help a child who does not know how to manage himself

1. Involve his father in the process of raising a child. Through communication, joint games and activities, children learn hierarchy and subordination.

2. Talk to the child about the feelings and emotions that he is experiencing, link his behavior and the possible cause of the protest. Keep calm and benevolent attitude, contain (that is, be able to withstand) the feelings, emotions, actions of the child, thereby creating support for him.

Keep calm and benevolent attitude, contain (that is, be able to withstand) the feelings, emotions, actions of the child, thereby creating support for him.

3. To develop control over the child's behavior, it is important to give him freedom of expression, supporting and helping the baby at his request - this stimulates the development of the frontal parts of the brain. It is important for an adult to remain for the child the one to whom one can come for help or advice. The parent's attitude of "presence without interference" provides support, but does not take away the initiative.

Interviewed by Anna Demina

Photo: Collection/iStock

Uncontrollable child - Krasnoyarsk regional narcological dispensary No. 1

When your child drives you crazy

There is a wonderful moment in the fairy tale by A. de Saint-Exupery [32]

about the Little Prince,

when the prince is talking to the Fox.

The fox asks him about his planet:

The fox was very surprised:

– On another planet?

- Yes.

– Are there hunters on that planet?

- No.

- How interesting! Are there chickens?

- No.

– There is no perfection in the world! Lis sighed.

Moral: regardless of our desires and aspirations, we will not find perfection in the real world, just as it cannot be in the people living next to us, and in ourselves.

The birth of a child is a wonderful time for parents. Many parents expect and believe that raising and growing a child will bring true pleasure alone. And according to this logic, children will always be obedient and controlled by us like robots until they come of age, or even longer. But, we must understand that children are not robots and there are no ideal children. Children have the right to pampering, tantrums and testing their parents for strength and boundaries. This is fine. For every parent - mom or dad, there are moments when, it would seem, there are no forces. And there is nothing to be ashamed of. What are they to do and how to be? After all, an obedient child does not fall from the sky, is not given away and is not brought up by itself. Education requires great effort, trust, attention and most importantly - love.

But, we must understand that children are not robots and there are no ideal children. Children have the right to pampering, tantrums and testing their parents for strength and boundaries. This is fine. For every parent - mom or dad, there are moments when, it would seem, there are no forces. And there is nothing to be ashamed of. What are they to do and how to be? After all, an obedient child does not fall from the sky, is not given away and is not brought up by itself. Education requires great effort, trust, attention and most importantly - love.

Education, it's no secret to anyone, is formed from an early age, and the main thing here is not to let everything take its course. Often a small child does not obey, yells, hysteria and stamps his feet. This is especially true for children aged 3-4 years. If your child has become “uncontrollable” by this age period, you should not panic, but you should understand the reasons for this behavior and learn to find a common language with the baby. It all depends on the parents and their upbringing algorithms.

It all depends on the parents and their upbringing algorithms.

Three years is the age when a child so wants to feel like an adult and independent, at this age children already have their own “want” and are ready to defend it in front of adults. This is the time of discoveries and finds, the age of awakening fantasy and awareness of oneself as a person. A pronounced feature of this period is crisis of three years . It can be both pronounced and weak, but it must come. When it comes - rejoice - your child is developing normally.

The first signs of the crisis can often be seen as early as 1.5 years old, and its peak falls on the age of about three years (2.5-3.5 years).

In babies, it can manifest itself in different ways, but the main "symptoms" are extreme stubbornness, negativism and self-will:

- Negativism adult. Negativism is addressed to a specific person, and not to the situation and not to the content of the conversation.

- Stubbornness is the child's reaction when he insists on something, not because he really wants it, but because he demanded it.

- Protest - the child rebels against the norms of upbringing established for the child. A protest against the current way of life that has been established up to now and accepted by the child.

- Willfulness , striving for independence.

- Depreciation - the child ceases to appreciate what he appreciated before. Here, insults to adults begin, whom the child has always respected and appreciated, and, here, toys that he loved very much become uninteresting and ugly to him.

- Despotism - the child develops a desire to exercise power in relation to others. The child begins to control most often the mother, and decide where she can go and where not.

What should a parent do? And how to help a child survive a crisis?

It is impossible to guess how long the crisis will last for a three-year-old child. For some children, the crisis age goes unnoticed, while others linger in it for several years. A growing man will face age thresholds more than once, but the crisis of three years is considered an important step on the path of personal growth. Wise parents simply wait out the crisis, because first of all, the burden falls on the psyche of their child. One thing is fundamentally important here - to show the child a causal relationship between his act and the consequences for the child himself.

A growing man will face age thresholds more than once, but the crisis of three years is considered an important step on the path of personal growth. Wise parents simply wait out the crisis, because first of all, the burden falls on the psyche of their child. One thing is fundamentally important here - to show the child a causal relationship between his act and the consequences for the child himself.

Give your child freedom of choice

At the age of three, children expect from others, and especially from their parents, recognition of their independence and independence, even though they themselves are not yet ready for this. Therefore, it is very important for a child at this age to be consulted and asked for his opinion. Do not give your child ultimatums, approach the formulation of your requests or wishes more inventively.

For example, if a child expresses a desire to dress himself, there is nothing wrong with that, just foresee it and start getting ready a quarter of an hour earlier. This will keep both mother and child in a good mood.

This will keep both mother and child in a good mood.

You can also offer a choice between several options, such as eating from a red or yellow plate, walking in the park or playground, etc. The technique of switching attention works well. The child will know that his opinion is important in the family and is considered. For example, you are going to visit your sister, but you suspect that the baby may refuse your offer, then just invite the child to choose the clothes in which he will go to visit. As a result, you will switch the attention of the crumbs to choosing the right outfit, and he will not think about whether he should go with you or not.

Let the baby feel independent

The crisis of three years always manifests itself in a child with increased independence. The kid tries to do everything himself, even despite the fact that his capabilities do not always correspond to his desires. Parents need to be sympathetic to such aspirations. Try to be more flexible in upbringing, do not be afraid to slightly expand the duties and rights of the crumbs, let him feel independence, of course, only within reasonable limits, certain boundaries, nevertheless, must exist. Ask him sometimes for help or give some simple instructions. Never interfere in your child's activities unless he asks you to!

Try to be more flexible in upbringing, do not be afraid to slightly expand the duties and rights of the crumbs, let him feel independence, of course, only within reasonable limits, certain boundaries, nevertheless, must exist. Ask him sometimes for help or give some simple instructions. Never interfere in your child's activities unless he asks you to!

Learn to refuse

Not all parents can refuse their beloved child. However, being able to say a clear “No” is essential for every adult. In any family, boundaries must be set, beyond which it is impossible to go, and the child must know about them. Parents should not deviate from these rules - they are constant! If today is no, then tomorrow is no. And be sure to explain to your child why "no". If “no” is said, screaming and tantrums should not disturb your position.

Be patient

A child's desire to be an adult can be used to your advantage. For example, if you need to cross the road, you can ask the child to transfer you. This is much better than the standard: "So, give me your hand here, now we will cross the road."

This is much better than the standard: "So, give me your hand here, now we will cross the road."

Voice your child's experiences and feelings. This will allow him to better understand his feelings and see that you understand his condition. If you see that the child has fallen and is crying, tell him that he has fallen, hit, it hurts, and therefore he is crying. If the child was playing and broke his favorite toy, say, “You are upset because you broke the toy. You feel sorry for her. That's why you cried." If the child is happy that he managed to do something, just say: “You drew a good drawing and are very happy. You are pleased that you were able to draw such a picture. You are proud." And so on. Voicing emotions and feelings will help the child understand them and better understand himself.

How to respond to children's tantrums?

Children throw tantrums not because they enjoy misbehaving or because they want to annoy their parents. Children scream, stomp their feet and throw themselves on the floor because it works. Capricious, the child tries to achieve his goal and, having received what he wants through tantrums, he will definitely use this method again. It is very important to learn how to extinguish and stop tantrums, otherwise it will become a habit for the baby, and he will begin to use them as manipulation all the time.

Children scream, stomp their feet and throw themselves on the floor because it works. Capricious, the child tries to achieve his goal and, having received what he wants through tantrums, he will definitely use this method again. It is very important to learn how to extinguish and stop tantrums, otherwise it will become a habit for the baby, and he will begin to use them as manipulation all the time.

And with age, he will learn to manipulate his parents much more sophisticatedly. Therefore, how often he will resort to this method depends on the reaction of the parents from the very beginning. But it is never too late to fix everything, it is much worse to never change anything in this aspect.

Try to anticipate the whims of the child in order to prevent them

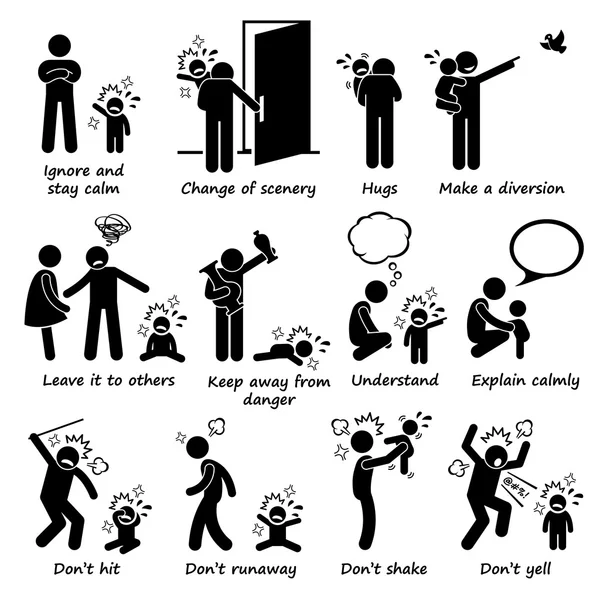

The most common mistake is to wait until his behavior is completely out of control. It is necessary to learn to predict the state of the child, even before an outbreak occurs. Pay attention to the characteristic harbingers of the storm - whimpering, restlessness, tension, and try to distract him at the first sign of irritation. Try to talk to your child in a soothing tone, stroke him, hug him, sing a song.

Try to talk to your child in a soothing tone, stroke him, hug him, sing a song.

Express zero tolerance for tantrums

The child must understand that no one will tolerate his behavior. As soon as the tantrum starts, stop talking to him until he calms down. You should not persuade him, shout, spank - none of these tools usually work. He won't even hear you over his screams. Try not to answer him, it’s better not to even look in his direction, you can defiantly put on headphones - this will make it clear to the baby that his cries are useless. The child throws tantrums in front of the person who reacts to them. You should not show that your child's tantrums excite and interest you. But be sure to tell him that as soon as he calms down, then you are ready to talk to him. And be patient.

Deprive the baby of spectators

For recurring tantrums, it is best to isolate the child as soon as an outbreak occurs. If this happens in a public place, move him to a more private place until he calms down. The most extreme option is the corner. And be sure to refuse him what he loves very much - a cartoon, a walk, games, sweets, etc. The kid must be aware that he does not deserve games and attention with his behavior. The duration of being in a sedative place for different children may be different, but he must remain there for at least two minutes from the moment of sedation. If he starts acting up again, take him back. The most difficult thing here is to keep your own calmness, but it is this that will help the child return to a calm state.

The most extreme option is the corner. And be sure to refuse him what he loves very much - a cartoon, a walk, games, sweets, etc. The kid must be aware that he does not deserve games and attention with his behavior. The duration of being in a sedative place for different children may be different, but he must remain there for at least two minutes from the moment of sedation. If he starts acting up again, take him back. The most difficult thing here is to keep your own calmness, but it is this that will help the child return to a calm state.

Your aversion to tantrums should be permanent

It is very important that you choose a line of behavior during tantrums and stick to it at all times. Then the child will understand that the result of his whims is unchanged. If the child is naughty with other people - a nanny, caregivers, your parents, discuss with them in advance a plan of behavior in such situations, emphasize that adults should not pay attention to whims. Communication with other children should be allowed only in a normal state.

Communication with other children should be allowed only in a normal state.

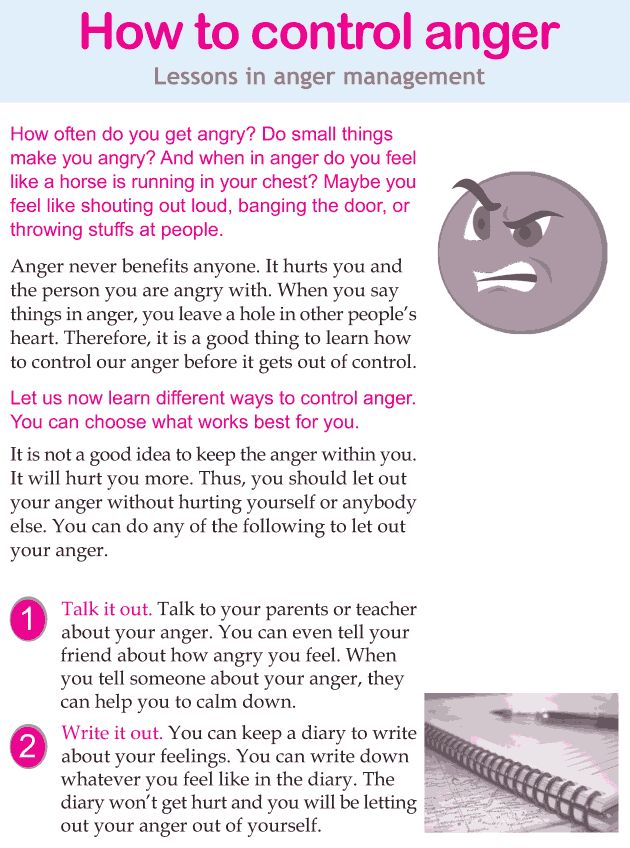

Teach your child how to express dissatisfaction properly

The child must understand that he can get upset, but not through tantrums. So when he and you calm down, talk about how to properly express dissatisfaction. Very often, children simply do not know how to express their condition in a different way, and therefore they begin to act up. Tell him how to express his emotions in words, teach him the appropriate words - angry, sad, tired, angry, upset. And encourage him when he uses these words, praise him.

Tantrum Response Brief:

1. Pull yourself together and take a short pause to collect yourself. You can count up to 10, for example.

2. Ask all “spectators” to leave the room, and if this is not possible, take the child to a quiet place where no one is around.

3. Decide for yourself whether you want (can) allow the child what he asks for. Think well, because maybe for you this is a trifle and unprincipled, but the child is very important and necessary.

Think well, because maybe for you this is a trifle and unprincipled, but the child is very important and necessary.

4. If not, tell your child your requirement in a stern, but always in an even and confident voice. And explain why no.

5. Be prepared for the fact that you will have to "listen" to the crying of a child for some time.

6. Under no circumstances deviate from your demand, repeat it if necessary.

7. When the child calms down, hug him and be sure to tell him how much you love him.

Parents also make mistakes

Error #1. Talk about the person, not the act.

“What a terrible child!”, “That's what bad boys do,” or “You're a bad boy. I don't need one." This seems to be clear to everyone, but for some reason it is still widely used. Don't forget about it!

Error #2. Put your blame on the child.

For example, they guessed that a child who is now running and playing might hit a cup on the edge of the table and still they didn’t remove it. Who is to blame that the cup was broken and for which the child was scolded? Or they allowed the child to stroke a street dog, and she bit. And now the mother scolds the child - don't you know that a dog can bite? The examples are exaggerated, but I think everyone will remember such a situation when you need to scold yourself, and we scold the child.

Who is to blame that the cup was broken and for which the child was scolded? Or they allowed the child to stroke a street dog, and she bit. And now the mother scolds the child - don't you know that a dog can bite? The examples are exaggerated, but I think everyone will remember such a situation when you need to scold yourself, and we scold the child.

Error #3. Use your "adult" advantages.

For example, a toy is taken away and placed high up on a cupboard where the child cannot reach it by himself. This makes him feel inferior (physically so far) and causes deep feelings of resentment and anger. Those who have already done this have noticed that at the moment when the toy is sent to the closet, the child starts screaming terribly and can throw a tantrum. And we do not help him to get out of the conflict correctly, but leave him alone and offer him to think about his behavior.

Error #4. Pressure on the material side of the issue.

This, in general, refers to the use of adult advantages, but I want to highlight this in a separate paragraph. For example, they were going to go for a toy, but there was a quarrel in which the child offended one of the parents. And this parent said that he would not buy a toy if he behaved like that. Yes, this is a quick way to get a child to obey, but at the same time, he does not think about how to respect the feelings of his father or mother, but about how to get his own benefits. When the child grows up a little, in certain situations he will try to remain silent, “so that they buy a toy”, and accumulate anger and resentment inside himself. Is it necessary to explain what will come of this and how, having become independent, a son or daughter will relate to their parents.

For example, they were going to go for a toy, but there was a quarrel in which the child offended one of the parents. And this parent said that he would not buy a toy if he behaved like that. Yes, this is a quick way to get a child to obey, but at the same time, he does not think about how to respect the feelings of his father or mother, but about how to get his own benefits. When the child grows up a little, in certain situations he will try to remain silent, “so that they buy a toy”, and accumulate anger and resentment inside himself. Is it necessary to explain what will come of this and how, having become independent, a son or daughter will relate to their parents.

The conclusion from this paragraph is as follows: in a conflict situation, talk about feelings and teach the child to respect them, to behave correctly in this or that situation. Try not to punish with deprivation of material things due to bad behavior.

Error #5. Aggressive behavior, loss of self-control, use of harsh words, a belt.

From this, the child remembers that if he loses control over the situation, he can lose control over himself, that the one who behaves more aggressively speaks more rudely, etc. is right. This is not to mention the fact that children are often frightened by such a reaction from their parents and immediately "begin to behave normally." Indeed, in such conditions, it is no longer possible to be an equal participant in the situation. A child cannot spank mom or dad, or even yell at them in the same way.

Error #6. Forcing your child to apologize often and for every little thing when you don't do it yourself.

Teaching a child to admit his guilt and ask for forgiveness is possible only by personal example. If you yourself ask for forgiveness from a child when you yell at him or do something wrong, then the child will answer you in the same way and will be able to apologize for his whims and admit that he was wrong.

Error #7. “Do bad things” to the child as a punishment and punish humiliatingly.

“Do bad things” to the child as a punishment and punish humiliatingly.

If it comes to punishment, then remember that it is better to deprive a child of good things than to do him bad things. Those. it is better not to read at night, not to play, etc., than to shout and spank. It is possible to punish a child, but punishment, in no case, should be humiliating and should not take place in front of other people. When a conflict flares up in a crowded place, an approach called "ear education" can be applied. Try it, maybe it will help you.

Lastly, don't forget the golden rule: "Before you say it to your child, say it to yourself." Then there will be an order of magnitude fewer conflicts, they will be more constructive, there will be more respect for parents, the child's self-esteem will be in order, and he will also learn to control himself and his behavior.

The task of parents is to do everything in their power to make the child comfortable not only within the walls of the house, but also in human society as a whole.