How to get a male pregnant

Can men become pregnant: What to know

A person who was born male and is living as a man cannot get pregnant. However, some transgender men and nonbinary people can.

In most cases, including cis-men who have sex with men, male pregnancy is not possible. New research in uterine transplants may mean that male pregnancy could be a possibility in the future, though.

In this article, we will discuss the difference between sex and gender before explaining more about transgender and male pregnancy.

Anyone who has a uterus and ovaries could become pregnant and give birth.

People who are born male and living as men cannot get pregnant. A transgender man or nonbinary person may be able to, however.

It is only possible for a person to be pregnant if they have a uterus. The uterus is the womb, which is where the fetus develops. Male reproductive organs include testicles and a penis but no uterus.

The terms “man” and “woman” refer to a person’s gender, which encompasses the socially constructed characteristics that differentiate the traditional binary sexes — male and female.

Unlike a person’s biological sex, which an individual’s reproductive organs and secondary sex characteristics define, genetics alone do not determine a person’s gender.

A person’s gender may include specific social roles, norms, and expectations that differentiate men and women.

These characteristics are subjective, and they differ among societies, social classes, and cultures. The gender by which a person identifies depends on the individual.

Gender is much more fluid than biological sex.

Typically, people are assigned male or female at birth. Those who identify with the gender that society associates with their biological sex are “cisgender” men and women.

Cisgender men who have sex with cisgender men cannot get pregnant.

However, not everyone identifies with the gender role that is associated with their designated sex. For instance, a person who was assigned female at birth (AFAB) but identifies as a man may refer to themselves as a “transgender” man or a gender nonconforming individual.

Many AFAB people who identify as men or gender nonconforming people retain their ovaries and uterus, which allows them to get pregnant and give birth.

People who have a uterus and ovaries can become pregnant and give birth.

However, some AFAB people may take testosterone. Testosterone therapy helps suppress the effects of estrogen while stimulating the development of masculine secondary sex characteristics, including:

- muscle growth

- redistribution of body fat

- increased hair growth on the body and face

- deeper voice

Research suggests that menstruation usually ends within 12 months after starting testosterone therapy and often within 6 months, which can make conceiving more difficult but not impossible.

Although testosterone therapy does not make people infertile, a person may have a higher chance of placental abruption, preterm labor, anemia, and hypertension.

In a 2014 study, researchers surveyed 41 transgender men and gender nonconforming AFAB individuals who became pregnant and gave birth.

Of the individuals who reported using testosterone before pregnancy, 20% became pregnant before their menstrual cycle returned.

The authors of this study concluded that prior testosterone use did not lead to significant differences in pregnancy, delivery, or birth outcomes.

The authors also noted that a higher percentage of transgender men who reported previous testosterone use had a cesarean delivery compared with those who had no history of testosterone use.

These findings do not suggest that testosterone therapy makes people incapable of vaginal delivery, as 25% of the transgender men who had a cesarean delivery chose to do so based on their comfort levels and preferences.

However, there is limited research regarding transgender pregnancy, so it is unclear how testosterone may affect a person’s fertility or pregnancy.

In a 2019 case study, researchers documented the experience of one 20-year-old transgender man who became pregnant 2 months after he discontinued testosterone therapy.

After 40 weeks, he gave birth to a healthy baby after an uncomplicated labor.

The authors stated that he chestfed for 12 weeks before restarting testosterone therapy.

People who have had a bilateral mastectomy or other chest surgeries may not be able to chestfeed.

Transgender men and AFAB individuals who do not identify as female may elect to undergo a range of medical treatments and surgical procedures during the transition process.

Examples of gender-affirming surgical procedures for transgender men include:

- Male chest reduction or “top surgery”: This procedure involves the removal of both breasts and any underlying breast tissue.

- Hysterectomy: A hysterectomy refers to the removal of the internal female reproductive organs, including the ovaries and uterus.

- Phalloplasty: During this procedure, a surgeon constructs a neopenis from skin grafts.

- Metoidioplasty: This treatment uses a combination of surgery and hormone therapy to enlarge the clitoris and make it function as a penis.

If a person has undergone a partial hysterectomy — which involves the removal of the womb but not the ovaries, cervix, and fallopian tubes — it is possible for the fertilized egg to latch onto the fallopian tubes or the abdomen, resulting in an ectopic pregnancy.

However, this is exceedingly rare, and according to a 2015 review, there are only 71 cases on record since 1895.

Gender does not determine who can become pregnant.

People who identify as men can, and do, become pregnant and give birth, if they possess a uterus and ovaries.

Can Men Get Pregnant? Outcomes for Transgender and Cisgender Men

Is it possible?

Yes, it’s possible for men to become pregnant and give birth to children of their own. In fact, it’s probably a lot more common than you might think. In order to explain, we’ll need to break down some common misconceptions about how we understand the term “man.” Not all people who were assigned male at birth (AMAB) identify as men. Those who do are “cisgender” men. Conversely, some people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) identify as men. These folks may be “transgender” men or transmasculine people.

Those who do are “cisgender” men. Conversely, some people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) identify as men. These folks may be “transgender” men or transmasculine people.

Transmasculine is used to describe an AFAB individual who identifies or presents toward the masculine side of the spectrum. This person may identify as a man or any number of other gender identities including nonbinary, genderqueer, or agender.

Many AFAB folks who identify as men or who don’t identify as women have the reproductive organs necessary to carry a child. There are also emerging technologies that may make it possible for AMAB individuals to carry a child.

Your reproductive organs and hormones may change what pregnancy looks like, but your gender isn’t — and shouldn’t be — considered a limiting factor.

If you have a uterus and ovaries

Some people who have a uterus and ovaries, are not on testosterone, and identify as men or as not as women may wish to become pregnant. Unless you’ve taken testosterone, the process of pregnancy is similar to that of a cisgender woman. Here, we’ll focus on the process of carrying a child and giving birth for AFAB folks who have a uterus and ovaries, and are,or have been, on testosterone.

Unless you’ve taken testosterone, the process of pregnancy is similar to that of a cisgender woman. Here, we’ll focus on the process of carrying a child and giving birth for AFAB folks who have a uterus and ovaries, and are,or have been, on testosterone.

Conception

For those who opt to take testosterone, menses typically stop within six months of starting hormone replacement therapy (HRT). In order to conceive, a person will need to stop the use of testosterone. Still, it isn’t entirely unheard of for people who are on testosterone to become pregnant from having unprotected vaginal sex. Due to a lack of research and variations in individual physiology, it’s still not entirely clear how effective testosterone use is as a method of pregnancy prevention. Kaci, a 30 year-old trans man who has undergone two pregnancies, says that many doctors falsely tell people starting testosterone that it will make them infertile. “While there’s very little research that’s been conducted on gender non-conforming pregnancies or the effects of HRT on fertility, [the] data [that] is available happens to be overwhelmingly positive. ” Take the results of one 2013 report, for example. The researchers surveyed 41 transgender men and transmasculine folks who had stopped taking testosterone and became pregnant. They found that most respondents were able to conceive a child within six months of stopping testosterone. Five of these people conceived without having first resumed menstruation.

” Take the results of one 2013 report, for example. The researchers surveyed 41 transgender men and transmasculine folks who had stopped taking testosterone and became pregnant. They found that most respondents were able to conceive a child within six months of stopping testosterone. Five of these people conceived without having first resumed menstruation.

Conception can happen in many ways, including sexual intercourse and through the use of assisted reproductive technologies (AST). AST may involve using sperm or eggs from a partner or donor.

Pregnancy

Researchers in the aforementioned 2013 survey didn’t find any significant differences in pregnancy between those who did and didn’t use testosterone. Some folks did report hypertension, preterm labor, placental interruption, and anemia, but these numbers were consistent with those of cisgender women. Interestingly, none of those respondents who reported anemia had ever taken testosterone. Anemia is common among cisgender women during pregnancy. However, pregnancy can be a challenging time emotionally.

Anemia is common among cisgender women during pregnancy. However, pregnancy can be a challenging time emotionally.

Transgender men and transmasculine folks who become pregnant often experience scrutiny from their communities.

As Kaci points out, “There’s nothing inherently feminine or womanly about conception, pregnancy, or delivery. No body part, nor bodily function, is inherently gendered. If your body can gestate a fetus, and that’s something you happen to want — then it’s for you, too.” People who experience gender dysphoria may find that these feelings intensify as their body changes to accommodate the pregnancy. The social association of pregnancy with womanhood and femininity can also lead to discomfort. Ceasing the use of testosterone may also exacerbate feelings of gender dysphoria. It’s important to note that discomfort and dysphoria aren’t a given for all trans folks who become pregnant. In fact, some people find that the experience of being pregnant and giving birth enhances their connection to their body.

The emotional impact of pregnancy is entirely dictated by each individual’s personal experience.

Delivery

The survey administrators found that a higher percentage of folks who reported testosterone use prior to conception had a cesarean delivery (C-section), though the difference wasn’t statistically significant. It’s also worth noting that 25 percent of people who had a C-section elected to do so, possibly due to discomfort or other feelings around vaginal delivery.

The researchers concluded that pregnancy, delivery, and birth outcomes didn’t differ according to prior testosterone use.

Although more research is necessary, this suggests that the outcomes for transgender, transmasculine, and gender non-conforming folks are similar to that of cisgender women.

Postpartum

It’s important that special attention be given to the unique needs of transgender people following childbirth. Postpartum depression is of particular concern. Studies show that 1 in 7 cisgender women experience postpartum depression. Given that the trans community experiences much higher rates of mental health conditions, they may also experience postpartum depression in higher numbers. The method of feeding a newborn is another important consideration. If you’ve elected to have a bilateral mastectomy, you may not be able to chestfeed. Those who haven’t had top surgery, or have had procedures such as periareolar top surgery, may still be able to chestfeed.

Postpartum depression is of particular concern. Studies show that 1 in 7 cisgender women experience postpartum depression. Given that the trans community experiences much higher rates of mental health conditions, they may also experience postpartum depression in higher numbers. The method of feeding a newborn is another important consideration. If you’ve elected to have a bilateral mastectomy, you may not be able to chestfeed. Those who haven’t had top surgery, or have had procedures such as periareolar top surgery, may still be able to chestfeed.

Still, it’s up to each individual to decide whether chestfeeding feels right for them.

Although there has yet to be a study on transgender men and lactation, exogenous testosterone has long been used as a method for suppressing lactation. This suggests that those who do take testosterone while chestfeeding may experience a decreased production in milk. With this in mind, it’s important to consider whether delaying your return to testosterone use is the right choice for you.

If you no longer have or were not born with a uterus

To our knowledge, there has not yet been a case of pregnancy in an AMAB individual. However, advances in reproductive technology could make this a possibility in the near future for folks who have had hysterectomies and those who were not born with ovaries or a uterus.

Pregnancy via uterus transplant

The first baby born from a transplanted uterus arrived in Sweden during October of 2014. While this procedure is still in its early experimental stages, several other babies have been born through this method. Most recently, a family in India welcomed a baby from a transplanted womb, the first such case in the country. Of course, like many such technologies, this method was developed with cisgender women in mind. But many have begun to speculate that this procedure could also apply to transgender women and other AMAB folks. Dr. Richard Paulson, the former president of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, suggested that uterine transplants for trans women and AMAB folks are more or less possible now. He added, “There would be additional challenges, but I don’t see any obvious problem that would preclude it.” It’s likely that supplementation to replicate hormonal phases during pregnancy would be necessary. Cesarean section would also be necessary for those who have undergone gender confirmation surgery.

He added, “There would be additional challenges, but I don’t see any obvious problem that would preclude it.” It’s likely that supplementation to replicate hormonal phases during pregnancy would be necessary. Cesarean section would also be necessary for those who have undergone gender confirmation surgery. Pregnancy via abdominal cavity

It has also been suggested that it may be possible for AMAB folks to carry a baby in the abdominal cavity. People have made this leap based on the fact that a very tiny percentage of eggs are fertilized outside of the womb in what is known as an ectopic pregnancy. However, ectopic pregnancies are incredibly dangerous for the gestational parent and typically require surgery. A significant amount of research would need to be done to make this a possibility for folks who don’t have a uterus, and even then, it seems incredibly unlikely that this would be a viable option for a hopeful parent.The bottom line

With our understanding constantly evolving, it’s important to honor the fact that one’s gender doesn’t determine whether they can become pregnant. Many men have had children of their own, and many more will likely do so in the future.

Many men have had children of their own, and many more will likely do so in the future.

It’s crucial not to subject those who do become pregnant to discrimination, and instead find ways to offer safe and supportive environments for them to build their own families.

Likewise, it seems feasible that uterus transplants and other emerging technologies will make it possible for AMAB individuals to carry and give birth to children of their own. The best thing we can do is to support and care for all people who choose to become pregnant, regardless of their gender and the sex they were assigned at birth.

Share on Pinterest

KC Clements is a queer, nonbinary writer based in Brooklyn, NY. Their work deals with queer and trans identity, sex and sexuality, health and wellness from a body positive standpoint, and much more. You can keep up with them by visiting their website, or by finding them on Instagram and Twitter.

Preparing a man for conception - clinic "Family Doctor".

- Home >

- About clinic >

- Publications >

- Preparing a man for conception

Preparation for conception is necessary for both a woman and a man. This is because the child receives 50% of the genetic material from each parent. So, for the birth of a healthy child, his parents must be healthy.

Many factors can affect the male reproductive system. First of all, bad habits should be mentioned, which include smoking and alcohol abuse, as well as constant stress and chronic lack of sleep. It is also the presence of sexually transmitted infections, exacerbation of chronic prostatitis, hormonal disorders, taking certain medications and steroids, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, overheating of the groin and perineum, etc.

When planning a conception, a man needs to exclude the impact of all of the above factors in three months and cure diseases and infections, because. the full cycle of sperm renewal takes three months.

the full cycle of sperm renewal takes three months.

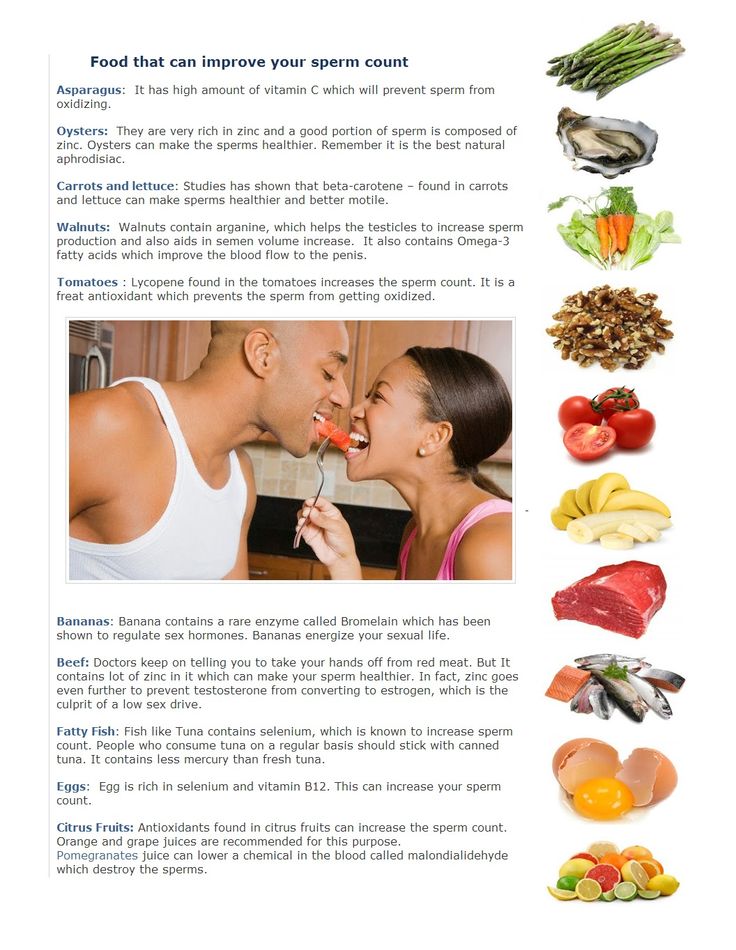

What can you do to improve the quality of your sperm = the genetic material of your unborn child?

1. Remember that sperm do not like overheating. Therefore, it is advisable to cancel visits to baths and saunas, to keep the seat heating in the car turned on for too long.

2. Reduce weight if you are obese. For men, a waist circumference in centimeters (at the level of the navel) over 94 cm = obese. In adipose tissue, testosterone is converted to estrogens, many inflammatory factors are produced, and this can also lead to type 2 diabetes, etc. Which, as you understand, are not the best companions for easily injured sperm!

3. Exclude sugary carbonated drinks, dyes, trans fats, confectionery from the diet.

4. Do not abuse alcohol. Alcohol, in addition to a direct toxic effect on spermatozoa, reduces the body's ability to absorb zinc, which is necessary for normal spermatogenesis.

5. Stop smoking. According to numerous studies, up to 50% of couples suffering from idiopathic infertility, after stopping smoking, find a long-awaited baby.

6. Try to be less nervous and sleep more.

7. Do not take medicines without a doctor's prescription (many drugs can significantly impair sperm quality). From here follows the rule: treat your chronic diseases before the moment of pregnancy planning.

In order to understand how fertile you are, you need to come to a consultation with a urologist-andrologist. It is advisable to have at least a spermogram with you. The rest of the list of examinations will be consulted by a doctor of the aforementioned specialty. It is better for a married couple to undergo an examination in parallel so that the treatment does not work out late, because. after the age of 35, a woman loses the ability to bear children faster than a man, and many couples miss the moment just because the man does not want to visit medical institutions.

To make an appointment with a specialist, call the single contact center in Moscow +7 (495) 775 75 66, fill out the online appointment form or contact the receptionist of the Family Doctor clinic.

Return to the list of publications

Physicians

About doctor Record

Annenkov Andrey Viktorovich

urologist, PhD

Clinic on Novoslobodskaya

Clinic on Usacheva

Clinic on Ozerkovskaya

About doctor Record

top

Is male pregnancy possible in nature? — T&P

The most famous example of “male pregnancy” is still the story of Thomas Beaty, a transgender man who retained his uterus and gave birth to three children.

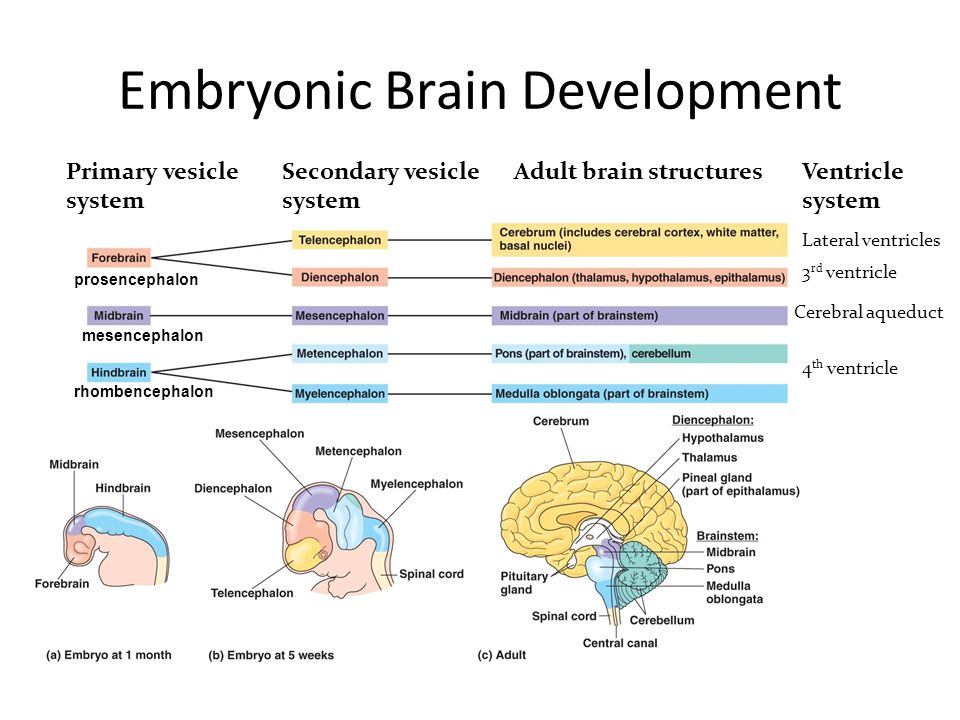

For several decades, biomedical scientists have been looking for ways that will allow a man to endure and give birth to a child without a sex change. This could be a new solution to the problem of infertility, and would also truly equalize men and women in rights. The Ivan Limbakh Publishing House publishes a book by sociologist Irina Aristarkhova "Hospitality of the Matrix: Philosophy, Biomedicine, Culture" translated by Daniil Zhayvoronok, which deals with the problems of new reproductive practices and gender identity. T&P publishes an excerpt about whether men need the function of childbearing and how close the world is to such a turn.

For several decades, biomedical scientists have been looking for ways that will allow a man to endure and give birth to a child without a sex change. This could be a new solution to the problem of infertility, and would also truly equalize men and women in rights. The Ivan Limbakh Publishing House publishes a book by sociologist Irina Aristarkhova "Hospitality of the Matrix: Philosophy, Biomedicine, Culture" translated by Daniil Zhayvoronok, which deals with the problems of new reproductive practices and gender identity. T&P publishes an excerpt about whether men need the function of childbearing and how close the world is to such a turn.

Biomedical Discourse of Male Pregnancy

Matrix Hospitality: Philosophy, Biomedicine, Culture

Over the past two decades, some eminent and eminent biomedical experts in various parts of the world have been explaining the feasibility of male pregnancy or taking it seriously (Walters 1991; Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998; Winston 1998; Gosden 2000). From a biomedical point of view, male pregnancy can be understood as another form of ectogenesis. As the long history of supporting ectogenetic research shows, male pregnancy is also seen as a solution to the problem of infertility and, increasingly and more specifically, as an issue of the legal rights of men (especially homosexual and transgender men) to reproduce. William Walters, Executive Clinical Director at the Royal Melbourne Women's Hospital and co-author of a book with Peter Singer (1982), is a prominent proponent of ectogenesis. Walters specializes in transsexuality and describes those who may be interested in male pregnancy: “[Biological males] expressing an interest or strong desire to have a child of their own include (i) transgender men who have become women, (ii) homosexuals in a monogamous relationship , (iii) single heterosexual males with strong maternal instincts, and (iv) married males whose wives are infertile or fertile but have serious health conditions that are unfavorable for childbearing” (Walters 1991, 739).

From a biomedical point of view, male pregnancy can be understood as another form of ectogenesis. As the long history of supporting ectogenetic research shows, male pregnancy is also seen as a solution to the problem of infertility and, increasingly and more specifically, as an issue of the legal rights of men (especially homosexual and transgender men) to reproduce. William Walters, Executive Clinical Director at the Royal Melbourne Women's Hospital and co-author of a book with Peter Singer (1982), is a prominent proponent of ectogenesis. Walters specializes in transsexuality and describes those who may be interested in male pregnancy: “[Biological males] expressing an interest or strong desire to have a child of their own include (i) transgender men who have become women, (ii) homosexuals in a monogamous relationship , (iii) single heterosexual males with strong maternal instincts, and (iv) married males whose wives are infertile or fertile but have serious health conditions that are unfavorable for childbearing” (Walters 1991, 739).

Currently, abdominal pregnancy and uterine transplantation are considered to be the main ways to achieve human male pregnancy in the future. It is worth noting that both of these possibilities treat pregnancy as a matter of "where" - that is, finding a suitable place to introduce a fertilized embryo into a male body. This problem is often presented as a major impediment to male pregnancy, reinforcing the understanding of the womb/womb as "just a smart incubator", as Gosden puts it, that could easily be replaced. Before we take a closer look at both of these possibilities for human male pregnancy, I will briefly outline the current state of biomedical research regarding this issue.

Teresi and Mcauliffe (1998) collected extensive information on Australian, New Zealand and British studies of male pregnancy in animals. It is important to note that most of these studies derive their justification from references to the benefits of biomedicine, which have nothing to do with male pregnancy, but rather deal with problems of embryonic development, evolutionary biology, fertility treatment, and so on. These examples, however, support my contention that the main question of pregnancy remains the question of where: where can a male baboon or mouse embryo be implanted and how long can that embryo survive inside the abdominal cavity without being expelled or reabsorbed. Spatial restrictions for the placement and development of the embryo, observed in animals, are given as one of the objections to the possibility of male pregnancy: “It is obvious. The placental sac and the baby at term will weigh about twenty-five pounds. And during all the months of growth, this bag can twist and turn” (Hallatt, cited in: Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 180). Despite these limitations, a male baboon carried an implanted embryo for four months, according to Dr. Jacobsen, a renowned fertility specialist credited with developing amniocentesis to check for genetic abnormalities. Jacobsen concludes that "the miracle of our discovery" was the realization that "a fertilized egg can be autonomous, producing all the hormones it needs for development" (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177).

These examples, however, support my contention that the main question of pregnancy remains the question of where: where can a male baboon or mouse embryo be implanted and how long can that embryo survive inside the abdominal cavity without being expelled or reabsorbed. Spatial restrictions for the placement and development of the embryo, observed in animals, are given as one of the objections to the possibility of male pregnancy: “It is obvious. The placental sac and the baby at term will weigh about twenty-five pounds. And during all the months of growth, this bag can twist and turn” (Hallatt, cited in: Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 180). Despite these limitations, a male baboon carried an implanted embryo for four months, according to Dr. Jacobsen, a renowned fertility specialist credited with developing amniocentesis to check for genetic abnormalities. Jacobsen concludes that "the miracle of our discovery" was the realization that "a fertilized egg can be autonomous, producing all the hormones it needs for development" (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177). Jacobsen also reported a successful abdominal pregnancy in a male chimpanzee (Andrews 1984, 261). A pregnant male mouse carried a fetus in her testicles for twelve days to "perfect condition," adds David Kirby of Oxford University, and it was only the lack of elasticity and space inside the testicles that stopped the development of the embryo (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177). With successful implantation and gestation in the male baboon and mouse, Harding concludes, like Jacobsen, "hormonally, the embryo is completely autonomous" (Harding, cited in Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 179). This means that a human male does not even have to undergo hormone therapy in order to become pregnant. Once the placenta develops, the "autonomous" creature will produce its own steroids on its own.

Jacobsen also reported a successful abdominal pregnancy in a male chimpanzee (Andrews 1984, 261). A pregnant male mouse carried a fetus in her testicles for twelve days to "perfect condition," adds David Kirby of Oxford University, and it was only the lack of elasticity and space inside the testicles that stopped the development of the embryo (Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 177). With successful implantation and gestation in the male baboon and mouse, Harding concludes, like Jacobsen, "hormonally, the embryo is completely autonomous" (Harding, cited in Teresi and Mcauliffe 1998, 179). This means that a human male does not even have to undergo hormone therapy in order to become pregnant. Once the placenta develops, the "autonomous" creature will produce its own steroids on its own.

The biomedical community thus assumes that if male pregnancy is ever possible, it will take place in the abdominal cavity. There is practically no discussion about the effect on surrounding organs. When it comes to pregnancy, the male body, like the female body, comes to be seen as a passive "bag of tissue" and an empty space just waiting to be filled through in vitro fertilization or some other type of assisted reproductive technology. The possibility of abdominal pregnancy in men is based not only on the limited number of male pregnancies in animals, but also on successful abdominal (i.e. ectopic) pregnancies in women. Abdominal pregnancies in women occur outside of their "place" they are supposed to, that is, they are ectopic. Today, most researchers are calling for a "wait and see" approach to ectopic pregnancies in previously infertile women or those who have passed the placental fixation stage without complications, "because it is impossible to predict which of the spontaneous abdominal pregnancies will develop in a relatively favorable way in order to produce a normal, healthy baby, the expectant approach to all abdominal pregnancies can be argued, especially when the carrier has a long history of infertility" (Walters 1991, 738-739).

There is practically no discussion about the effect on surrounding organs. When it comes to pregnancy, the male body, like the female body, comes to be seen as a passive "bag of tissue" and an empty space just waiting to be filled through in vitro fertilization or some other type of assisted reproductive technology. The possibility of abdominal pregnancy in men is based not only on the limited number of male pregnancies in animals, but also on successful abdominal (i.e. ectopic) pregnancies in women. Abdominal pregnancies in women occur outside of their "place" they are supposed to, that is, they are ectopic. Today, most researchers are calling for a "wait and see" approach to ectopic pregnancies in previously infertile women or those who have passed the placental fixation stage without complications, "because it is impossible to predict which of the spontaneous abdominal pregnancies will develop in a relatively favorable way in order to produce a normal, healthy baby, the expectant approach to all abdominal pregnancies can be argued, especially when the carrier has a long history of infertility" (Walters 1991, 738-739). The wording is important here: instead of focusing on the prevalence of failures, life-threatening cases, the focus has shifted to a relatively small number of successful cases, which paves the way for the biomedical future of male pregnancy.

The wording is important here: instead of focusing on the prevalence of failures, life-threatening cases, the focus has shifted to a relatively small number of successful cases, which paves the way for the biomedical future of male pregnancy.

For Roger Gosden, another researcher who seriously considers human male pregnancy, it is a distinct, if risky, possibility (Gosden 2000, 193–197). Gosden offers various grounds for male pregnancy: the father may be the recipient of the fetus until the mother's uterus is ready to receive it; male pregnancy can replace a surrogate or artificial pregnancy, which will mean lower costs and resolution of legal problems; it will bind the child and the father at a very early stage of development. Gosden, however, concludes that at present, "given the availability of safe alternatives, there is no need to construct an ectopic male pregnancy," where "safe alternatives" refers to traditional maternal pregnancy. Concerns about the safety of male pregnancy are notable, as Gosden seems to view father involvement in childbearing as highly scientifically probable. In his work, he also shows that the lack of research in this area in comparison with ectogenesis (its other species) is more the result of a "cultural gap" that refuses to recognize its possibility than a biological improbability: apparently, to get funding for the study of ectogenetic systems, even as far-flung and futuristic as male pregnancy, it is much easier than to study male pregnancy as such (Gosden 2000, 193–197).

In his work, he also shows that the lack of research in this area in comparison with ectogenesis (its other species) is more the result of a "cultural gap" that refuses to recognize its possibility than a biological improbability: apparently, to get funding for the study of ectogenetic systems, even as far-flung and futuristic as male pregnancy, it is much easier than to study male pregnancy as such (Gosden 2000, 193–197).

Walters, one of the early advocates of the possibility of male pregnancy, when discussing biomedical alternatives to infertility, seriously considers abdominal pregnancy for women: “Due to the possibility of abdominal pregnancy to end in the birth of a normal healthy child, it is understandable that some well-informed infertile couples consider this method of childbirth as solutions to their problems... There is no doubt that artificially induced abdominal pregnancy has legal and psychological benefits for infertile women who would otherwise have to consider surrogacy. In this way, her (the couple. - I. A.) understandable anxiety about the surrogate mother giving up the child at birth will be eliminated ”(Walters 1991, 733, 737).

In this way, her (the couple. - I. A.) understandable anxiety about the surrogate mother giving up the child at birth will be eliminated ”(Walters 1991, 733, 737).

The "site" commonly cited as suitable for implantation in the abdominal cavity is the omentum (one of the tissue folds of the peritoneum, a membrane that supports and envelops the organs of the peritoneum), since it seems impractical to allow a fertilized embryo to wander around the body. The human embryo needs to be immersed in tissues rather than superficially attached to them (it is noteworthy that implantation in humans is deeper than in other animals). Therefore, the omentum is chosen as a place where it can be implanted, where the blood supply and placenta can be developed and growth is ensured. Since men may not provide the necessary amount of hormones for the successful development of the embryo, they may need to undergo hormone therapy. In addition to many other drugs that correct their bodies to facilitate this process, they may need immunosuppressants, especially in the period before the placenta is fully developed. As previously shown in the case of male pregnancy in animals, the researchers believe that this should not be a big problem, since, they argue, the embryo in the first weeks of its development is more or less a self-sufficient creature. And just as it develops outside the body after artificial insemination and before implantation, the same will happen inside a man. Another possibility is that the embryo, once contact with the male body is established, will facilitate the production of the necessary hormones, just as it does in the female body through the placental surface.

As previously shown in the case of male pregnancy in animals, the researchers believe that this should not be a big problem, since, they argue, the embryo in the first weeks of its development is more or less a self-sufficient creature. And just as it develops outside the body after artificial insemination and before implantation, the same will happen inside a man. Another possibility is that the embryo, once contact with the male body is established, will facilitate the production of the necessary hormones, just as it does in the female body through the placental surface.

Male Pregnancy Project 1999-2002 Li Mingwei and Virgil Wong

The second option for male pregnancy is transplantation, and is based on animal and human uterine transplantation studies (Altchek 2003; Bedaiwy et al. 2008 ; Gauthier et al. 2008). One of the notable characteristics of uterine transplantation is that researchers present and treat it as a rare temporary transplant, as the uterus is not a vital organ, unlike the liver, kidney, and even the eyes. This means that after the baby is born, the uterus can be removed. In addition, due to hysterectomy, human wombs are almost constantly "available" and can be used relatively "cheaply". Gosden suggests that transplanting the uterus into the father's body would be beneficial for the baby, as the dense uterine walls provide a "safe" environment, and the risk of abnormalities in ectopic births exceeds 50 percent (Gosden 2000, 196). It is well known that the relative utility of uterine transplant research stems from the fact that not all cultural and religious contexts consider surrogacy or assisted reproduction acceptable. For example, one famous attempt at uterine transplantation was carried out in Saudi Arabia, and some argue that this is not surprising given the negative cultural attitudes towards surrogacy and assisted reproduction (Fageeh et al. 2002). Since women with ovaries, as well as women with ovarian tissues, benefit from ovarian tissue transplantation and in vitro fertilization in the postmenopausal period, there is agreement among biomedical scientists that it is only a matter of time before the uterus is transplanted into the woman and the embryo is implanted.

This means that after the baby is born, the uterus can be removed. In addition, due to hysterectomy, human wombs are almost constantly "available" and can be used relatively "cheaply". Gosden suggests that transplanting the uterus into the father's body would be beneficial for the baby, as the dense uterine walls provide a "safe" environment, and the risk of abnormalities in ectopic births exceeds 50 percent (Gosden 2000, 196). It is well known that the relative utility of uterine transplant research stems from the fact that not all cultural and religious contexts consider surrogacy or assisted reproduction acceptable. For example, one famous attempt at uterine transplantation was carried out in Saudi Arabia, and some argue that this is not surprising given the negative cultural attitudes towards surrogacy and assisted reproduction (Fageeh et al. 2002). Since women with ovaries, as well as women with ovarian tissues, benefit from ovarian tissue transplantation and in vitro fertilization in the postmenopausal period, there is agreement among biomedical scientists that it is only a matter of time before the uterus is transplanted into the woman and the embryo is implanted. and delivered on time. Thus, in this case, the rationale is that if a woman or a female animal is capable of this, then so is a man. It is noteworthy that the scientific language describes both of these problems in a very straightforward manner, which serves to increase the biomedical possibility of male pregnancy. The womb transplant is described as: medicate, inject, cut, remove, mix, grow, remove, inject, medicate, bear, cut, and become a mother. The male body is just another abdominal cavity, a simple implantation incubator.

and delivered on time. Thus, in this case, the rationale is that if a woman or a female animal is capable of this, then so is a man. It is noteworthy that the scientific language describes both of these problems in a very straightforward manner, which serves to increase the biomedical possibility of male pregnancy. The womb transplant is described as: medicate, inject, cut, remove, mix, grow, remove, inject, medicate, bear, cut, and become a mother. The male body is just another abdominal cavity, a simple implantation incubator.

However, many problems and complications surround both abdominal and womb transplant pregnancy. Just as in the case of abdominal pregnancy in women, the risk to the life of a pregnant man will be great. The vast majority of ectopic pregnancies end in surgery, provided that such a pregnancy is detected at an early stage and the operation is still possible. Otherwise, an ectopic pregnancy can be fatal. Other common complications are genetic abnormalities, developmental disorders and, if the child survives, a significantly reduced quality of life. Since the child is limited by adjacent organs, the head and body may not form properly. However, again we are told that since there are cases of healthy, normal children being born as a result of ectopic pregnancies, there is a (however small) possibility of successful pregnancy in men (Walters 1991). Most of the proponents of male pregnancy cited here (Gosden 2000; Walters 1991) refer to it as stemming from the needs of men who have "strong maternal instincts" and exhibit "effeminate" behavior - as "transgender", "feminine" or hormonalized during pregnancy. . These perspectives once again reveal pregnancy as a maternal attitude (even when discussing male pregnancy) and an attitude of hospitality. Thus, apart from the need for internal tissues "like a womb" (like an omentum), or the need for a uterine transplant, that is, apart from searching for an "empty space" inside the male body, the idea of male pregnancy has the potential to change, thanks to the mother's attitude of hospitality and that what this attitude makes possible is the perception of what it means to be a man.

Since the child is limited by adjacent organs, the head and body may not form properly. However, again we are told that since there are cases of healthy, normal children being born as a result of ectopic pregnancies, there is a (however small) possibility of successful pregnancy in men (Walters 1991). Most of the proponents of male pregnancy cited here (Gosden 2000; Walters 1991) refer to it as stemming from the needs of men who have "strong maternal instincts" and exhibit "effeminate" behavior - as "transgender", "feminine" or hormonalized during pregnancy. . These perspectives once again reveal pregnancy as a maternal attitude (even when discussing male pregnancy) and an attitude of hospitality. Thus, apart from the need for internal tissues "like a womb" (like an omentum), or the need for a uterine transplant, that is, apart from searching for an "empty space" inside the male body, the idea of male pregnancy has the potential to change, thanks to the mother's attitude of hospitality and that what this attitude makes possible is the perception of what it means to be a man.

In summary, biomedical experts who view male pregnancy as the outcome and next (logical?) step of their own practice place it in the same rubric as research on uterine transplantation and preterm birth, while agreeing that bioethically is a much more complex issue. It has become much more relevant and openly discussed in homosexual and transgender communities (Walters 1991; Sparrow 2008). Although Gosden never mentions homosexuality and suggests male pregnancy as a solution to the heterosexual family's problems with fulfilling it natural when a woman is unable or unwilling to bear a child herself, in other discourses, the terminology of reproductive "rights" and "freedoms" for homosexual and transgender men has significantly influenced this discussion, shifting the emphasis from sacred duty or pre-established need in nuclear heterosexual reproduction to the right to have a child for men.

Bioethical discourses on the possibility of male pregnancy

In the bioethical literature, the problem of male pregnancy is associated with the discourse of the "right" to receive additional reproductive services. The logic here is simple: if we spend so much time and effort helping women who would otherwise not be able to conceive and bear children, then we need to help men too. Assisted reproductive technologies should not discriminate against anyone: neither the poor nor the rich; neither healthy nor sick or people with developmental features; neither white nor non-white; neither women nor men. This argument seems to be quite valid, especially in cases where those who wish to receive such services must pay for them out of their own pocket, thus reinforcing the individual right to "autonomy" and "freedom of choice".

The logic here is simple: if we spend so much time and effort helping women who would otherwise not be able to conceive and bear children, then we need to help men too. Assisted reproductive technologies should not discriminate against anyone: neither the poor nor the rich; neither healthy nor sick or people with developmental features; neither white nor non-white; neither women nor men. This argument seems to be quite valid, especially in cases where those who wish to receive such services must pay for them out of their own pocket, thus reinforcing the individual right to "autonomy" and "freedom of choice".

Another justification for male pregnancy in bioethics is the market economic model. According to this logic, male pregnancy, like other assisted reproductive services, will be a normal business model doing some work for families and individuals, just like an adoption agency and an assisted reproduction clinic. Currently, unmarried men can pay for surrogacy services in some US states. Both Walters (1991) and Gosden (2000) argue that male pregnancy can reduce the number of complications (especially emotional, legal, and financial) associated with surrogacy. If an unmarried woman (gay or not) wishes to receive in vitro fertilization (IVF) services using frozen sperm to have children of her own, then she can do so, and a man whose desire to have a biological child in this system is guaranteed through egg donation and surrogacy (considering, of course, that he is quite wealthy and IVF will work for a surrogate mother), can also receive such a service.

Both Walters (1991) and Gosden (2000) argue that male pregnancy can reduce the number of complications (especially emotional, legal, and financial) associated with surrogacy. If an unmarried woman (gay or not) wishes to receive in vitro fertilization (IVF) services using frozen sperm to have children of her own, then she can do so, and a man whose desire to have a biological child in this system is guaranteed through egg donation and surrogacy (considering, of course, that he is quite wealthy and IVF will work for a surrogate mother), can also receive such a service.

The Male Pregnancy Project 1999–2002 Lee Mingway and Virgil Wong

Although the definitions of feminine and masculine are becoming more and more complex in biomedical and bioethical discourses, they still rest, interestingly enough, on the fact that which is regarded as the "science" of "sexual differentiation". The legal terminology pertaining to it has shifted from primary and secondary "sexual characteristics" such as penis/testicles and uterus/vagina/breasts to "masculine behaviour", "biological male" and "chromosomal male" (Walters 1991, 199; Sparrow 2008). Each new definition seeks to overcome the shortcomings found in the previous one. The problem with definitions usually comes up when economic, political, and health inequalities are recognized for transgender, transgender, biogender, bisexual, intergender, intersex, and homosexual communities and individuals (Roscoe 1991).

Each new definition seeks to overcome the shortcomings found in the previous one. The problem with definitions usually comes up when economic, political, and health inequalities are recognized for transgender, transgender, biogender, bisexual, intergender, intersex, and homosexual communities and individuals (Roscoe 1991).

Sparrow (2008) wrote an excellent essay that takes male pregnancy seriously from a bioethical perspective. However, despite Sparow's recognition of legal, economic, and medical inequalities, his main bioethical argument against male pregnancy is still based on the notion of biology as "destiny." Thus, according to Sparow, the suggestion that men have the right to be pregnant is a mockery of the "natural order of things," especially since some women want but cannot get pregnant. However, such a claim, in turn, undermines women's claim to these technologies as their "natural" right in addition to their "cultural" rights. Therefore, Sparow argues, such reasoning is a perversion of the concept of "reproductive freedom" and "rights" and makes a joke of women's rights, especially since male pregnancy is not based on "normal human life cycle" "reproductive biology facts" or "normal reproduction context" and is a "frivolous or banal project" (Sparrow 2008, 287). His argument against male pregnancy reveals that women's claims to a fundamental "right" to assisted reproduction are often based on cultural or political arguments—even if "nature" is used to support them—and argues for women's specific rights at the expense of other groups. (including animals). When it comes to men, however, the social and collective needs and contexts surrounding pregnancy are invoked, and the "collective" and "social" are favored over individual rights to pregnancy (Squier 1995).

His argument against male pregnancy reveals that women's claims to a fundamental "right" to assisted reproduction are often based on cultural or political arguments—even if "nature" is used to support them—and argues for women's specific rights at the expense of other groups. (including animals). When it comes to men, however, the social and collective needs and contexts surrounding pregnancy are invoked, and the "collective" and "social" are favored over individual rights to pregnancy (Squier 1995).

As Walters (1991) points out, along with others, the biggest beneficiaries of IVF and assisted reproductive medicine research are (white) affluent women. Squier (1994 and 1995) also notes that we often forget that current biomedical research is not politically and culturally neutral. Therefore, Sparow's argument that male pregnancy is not is a normal reproductive context and therefore should not be supported is untenable, as the same charge can be leveled against current biomedical research on infertility in general: a significant amount of scientific and government resources are directed to support the treatment of infertility in privileged women, who, in turn, can support such research through social, cultural and political pressure on the relevant institutions.