Hiv pregnant women

Pregnancy and HIV | Office on Women's Health

A diagnosis of HIV does not mean you can't have children. But you can pass HIV to your baby during the pregnancy, while in labor, while giving birth, or by breastfeeding. The good news is that there are many ways to lower the risk of passing HIV to your unborn baby to almost zero.

What can I do before getting pregnant to lower my risk of passing HIV to my baby?

If you plan to become pregnant, talk to your doctor right away. Your doctor can talk with you about how HIV can affect your health during pregnancy and your unborn baby's health. Your doctor can work with you to prepare for a healthy pregnancy before you start trying to become pregnant.

Everyone living with HIV should take HIV medicines to stay healthy. If you are thinking about becoming pregnant and are not taking HIV treatment, it is important that you begin, because this will lower your chances of passing the virus to your baby when you become pregnant.

There are ways for you to get pregnant that will limit your partner's risk of HIV infection. You can ask your doctor about ways to get pregnant and still protect your partner.

I do not have HIV, but my partner does. Can I get pregnant without getting HIV?

Women have a higher risk of HIV infection during vaginal sex than men. If you do not have HIV but your male partner does, the risk of getting HIV while trying to get pregnant can be reduced but not totally eliminated.

Talk to your doctor about HIV medicine you can take (called pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP) to help protect you and your baby from HIV.

You may also want to consider donor sperm or assisted reproductive technology, such as semen washing or in vitro fertilization, to get pregnant. These options can be expensive and may not be covered by your health insurance.

I'm pregnant. Will my baby have HIV?

If you just found out you are pregnant, see your doctor right away. Find out what you can do to take care of yourself and to give your baby a healthy start to life.

With your doctor's help, you can decide on the best treatment for you and your baby before, during, and after the pregnancy. You should also take these steps before and during your pregnancy to help you and your baby stay healthy.

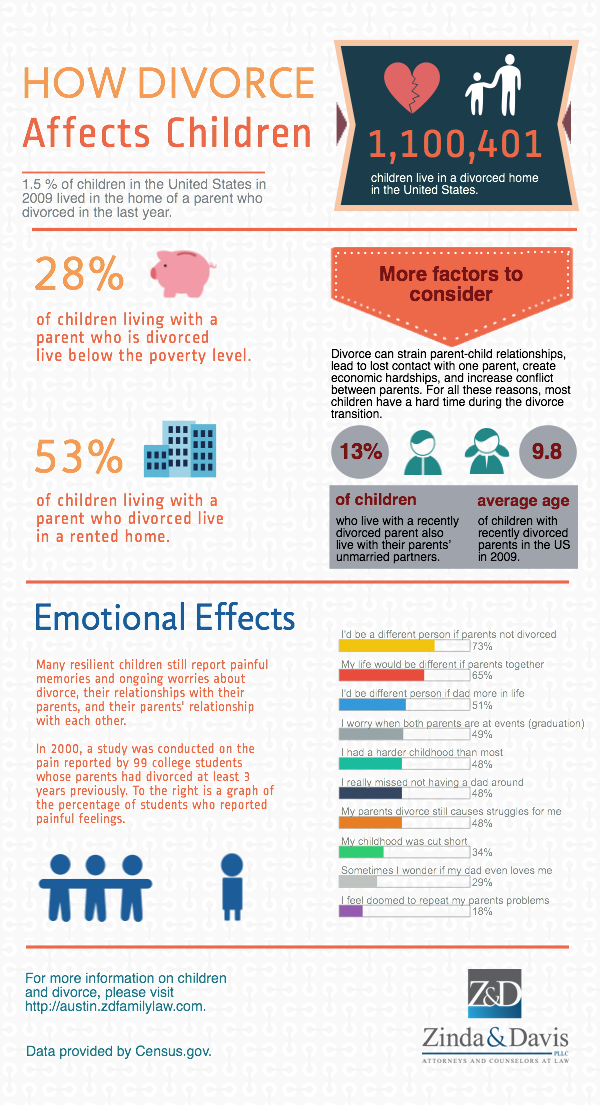

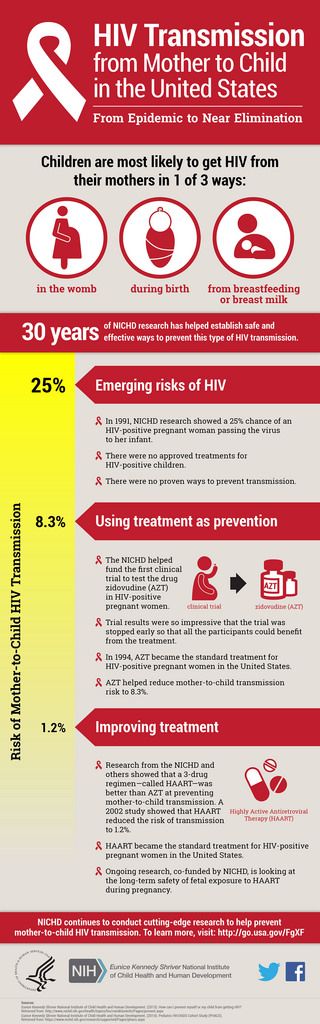

Just because you have HIV doesn't mean your child will get HIV. In the United States, before effective treatment was available, about 25% of pregnant mothers with HIV passed the virus to their babies. Today, if you take HIV treatment and have an undetectable viral load, your risk of passing HIV to your baby is less than 1%.1

What can I do to lower my risk of passing HIV to my baby?

Thanks to more HIV testing and new medicines, the number of children infected with HIV during pregnancy, labor and childbirth, and breastfeeding has decreased by 90% since the mid-1990s.1

The steps below can lower the risk of giving HIV to your baby:

Tell your doctor you want to get pregnant. Your doctor can help you decide if you need to change your treatments to lower your viral load, to help you get pregnant without passing HIV to your partner, and to prevent you from passing the virus to your baby. He or she will also help you get as healthy as possible before you get pregnant to improve your chances of a healthy pregnancy and baby. Don't stop using condoms for STI prevention and another method of birth control for pregnancy prevention until your doctor says you are healthy enough to start trying.

He or she will also help you get as healthy as possible before you get pregnant to improve your chances of a healthy pregnancy and baby. Don't stop using condoms for STI prevention and another method of birth control for pregnancy prevention until your doctor says you are healthy enough to start trying.

Get prenatal care. Prenatal care is the care you receive from your doctor while you are pregnant. You need to work closely with your doctor throughout your pregnancy to monitor your treatment, your health, and your baby's health.

Start HIV treatment. You can start treatment before pregnancy to lower the risk of passing HIV to your baby. If you are already on treatment, do not stop, but do see your doctor right away. Some HIV drugs should not be used while you're pregnant. For other drugs, you may need a different dosage.

Manage side effects. Side effects from HIV medicines can be especially challenging during pregnancy, but it is still important that you take your medicine as directed by your doctor. Talk to your doctor about any side effects you have and about ways to manage them.

Talk to your doctor about any side effects you have and about ways to manage them.

Do not breastfeed. You can pass the virus to your baby through your breastmilk even if you are taking medicine. The best way to avoid passing HIV to your baby is to feed your infant formula instead of breastfeeding.

Make sure your baby is tested for HIV right after birth. You should choose a doctor or clinic experienced in caring for babies exposed to HIV. They will tell you what follow-up tests your baby will need and when. Talk to your doctor about whether your baby may benefit from starting treatment right away.

Ask your pediatric HIV specialist if your baby might benefit from anti-HIV medicines before you know if your baby is HIV-positive or HIV-negative. Research has shown that giving combination HIV drugs to newborns is better at preventing HIV than taking AZT (azidothymidine, an antiretroviral medicine) alone.

Can I take HIV medicine during pregnancy?

HIV-infected pregnant women should take HIV medicines. These medicines can lower the risk of passing HIV to a baby and improve the mother's health.

These medicines can lower the risk of passing HIV to a baby and improve the mother's health.

If you haven't used any HIV drugs before pregnancy and are in your first trimester, your doctor will help you decide if you should start treatment. Here are some things to consider:

- Nausea and vomiting may make it hard to take the HIV medicine early during pregnancy.

- It is possible the medicine may affect your baby. Your doctor will prescribe medicine that is safe to use during pregnancy.

- HIV is more commonly passed to a baby late in pregnancy or during delivery. HIV can be passed early in pregnancy if your viral load is detectable.

- Studies show treatment works best at preventing HIV in a baby if it is started before pregnancy or as early as possible during pregnancy.

If you are taking HIV drugs and find out you're pregnant in the first trimester, talk to your doctor about sticking with your current treatment plan. Some things you can talk about with your doctor include:

Some things you can talk about with your doctor include:

- Whether to continue or stop HIV treatment in the first trimester. Stopping HIV medicine could cause your viral load to go up. If your viral load goes up, the risk of infection also goes up. Your disease also could get worse and cause problems for your baby. So this is a serious decision to make with your doctor.

- What effects your HIV medicines may have on the baby

- Whether you are at risk for drug resistance. This means the HIV medicine you take no longer works against HIV. Never stop taking your HIV medicine without first talking to your doctor.

Can I get help paying for care during pregnancy?

If you are pregnant, Medicaid may pay for your prenatal care. If you are pregnant and living with HIV, Medicaid might pay for counseling, medicine to lower the risk of passing HIV to your baby, and treatment for HIV. Each state makes its own rules regarding Medicaid. Contact your local or county medical assistance, welfare, or social services office to learn more. If you are unable to find that number, search your state's department of health.

If you are unable to find that number, search your state's department of health.

If you don't think you qualify for assistance, check again. Sometimes states change their Medicaid rules. Under the Affordable Care Act, Medicaid eligibility expanded to cover many more people. Also, you may be newly eligible for Medicaid because of increased income limits for prenatal care and HIV treatment for pregnant women.

You may also access care through the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Find a Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program medical care provider near you.

Did we answer your question about HIV and pregnancy?

For more information about HIV and pregnancy, call the OWH Helpline at 1-800-994-9662 or check out the following resources from other organizations:

- HIV Among Pregnant Women, Infants, and Children — Fact sheet from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- HIV and Pregnancy — Information from AIDSinfo.

- Infant feeding and HIV — Publication from UNICEF.

- Elimination of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission (EMCT) in the United States — Fact sheet from CDC.

- One Test. Two Lives. — Campaign information from the CDC.

Sources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). HIV Among Pregnant Women, Infants, and Children.

All material contained on these pages are free of copyright restrictions and maybe copied, reproduced, or duplicated without permission of the Office on Women’s Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Citation of the source is appreciated.

Page last updated: February 18, 2021

EMCT | Pregnant Women, Infants, and Children | Gender | HIV by Group | HIV/AIDS

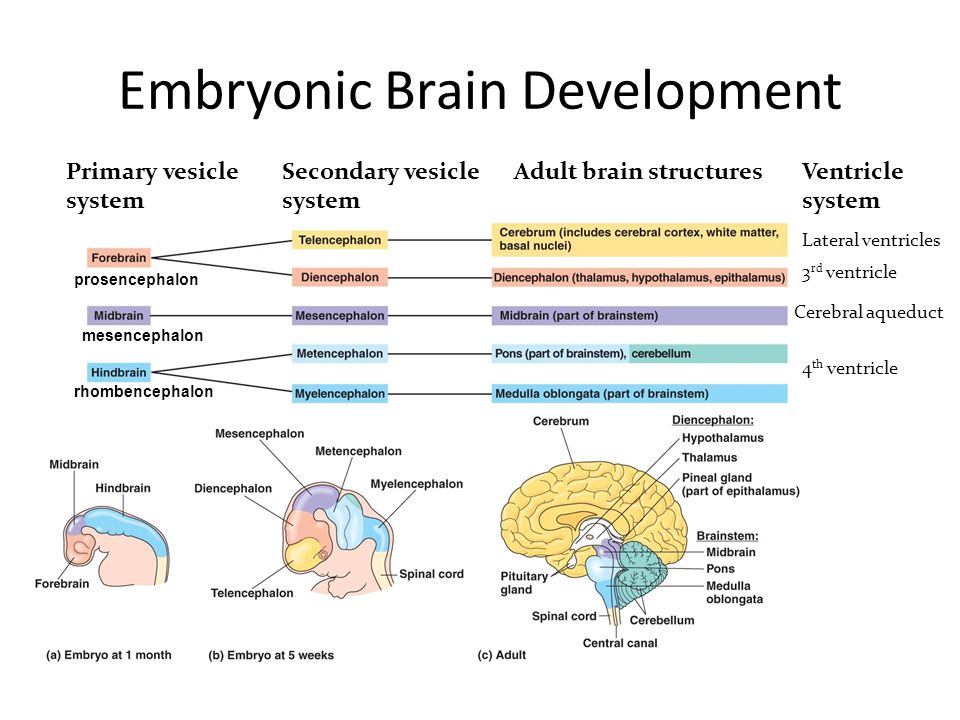

In collaboration with national experts and federal partners, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a new framework directed at the goal of eliminating mother-to-child (perinatal) HIV transmission (EMCT) in the United States. The framework is illustrated in Figure 1 [the numbers in superscript below refer to the corresponding numbered activities in the figure] and differs from the previous approach to PMTCT in its consistent use of public health personnel to 1) assure that HIV care includes comprehensive reproductive health, family planning services and preconception care and that women of childbearing age are HIV tested according to CDC recommendations1; and 2) conduct comprehensive, real-time case finding2 of all HIV-infected pregnant women and their exposed infants. These two large tasks are conducted under the concept of Perinatal HIV Services Coordination (PHSC). PHSC in each state (or jurisdiction) could assure comprehensive, real-time case finding. It may be helpful to have these functions combined with other related activities, such as the prevention of other perinatally acquired infections. With the financial realities facing all levels of government, and the fact that most HIV-infected pregnant women are, in fact, in care, it will not be possible—and may not be necessary—for PHSC to actively monitor each woman, once it has been determined that the woman is in care. On the other hand, for those women recognized as not in care, finding cases in real time would enable the conduct and coordination of the following components of the EMCT framework:

These two large tasks are conducted under the concept of Perinatal HIV Services Coordination (PHSC). PHSC in each state (or jurisdiction) could assure comprehensive, real-time case finding. It may be helpful to have these functions combined with other related activities, such as the prevention of other perinatally acquired infections. With the financial realities facing all levels of government, and the fact that most HIV-infected pregnant women are, in fact, in care, it will not be possible—and may not be necessary—for PHSC to actively monitor each woman, once it has been determined that the woman is in care. On the other hand, for those women recognized as not in care, finding cases in real time would enable the conduct and coordination of the following components of the EMCT framework:

- Comprehensive Care (facilitation of comprehensive clinical and psychosocial HIV services for women and infants3; )

- Case Review and Community Action (FIMR-HIV) to identify and address missed prevention opportunities and local systems issues through continuous quality improvement4;

- Research and long-term monitoring to develop and ensure safe and efficacious PMCT interventions5; and Data reporting for HIV surveillance and EMCT evaluation6.

Reproductive Health, Family Planning Services and Preconception Care

Increased identification of HIV infection prior to pregnancy, and maintenance of more women in care would result in more opportunities to optimize HIV-infected women’s health prior to and between pregnancies, particularly with new guidelines recommending early antiretroviral (ARV) treatment. Proper attention to women’s HIV care inclusive of reproductive health and family planning will support women prevent unintended pregnancy.

Comprehensive real-time case finding

A “case” is a pregnancy in an HIV-infected woman. Case-finding requires both universal HIV testing of pregnant women and a mechanism for detecting pregnancy among women with diagnosed HIV infection and is distinct from traditional HIV surveillance because cases must be identified in real time.

Comprehensive Care

Clinical management for HIV-infected pregnant women and their infants is credited with much of the documented reduction in MCT. Local expertise in clinical care has been nurtured by the support for clinical activities provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), under the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Assuring linkages to these clinical providers is a key function of the PHSC. Under the financial restraints of recent years, jurisdictions will need to determine the degree of their involvement with individual HIV-infected pregnant women. Recent national health-care reform may enhance EMCT through reimbursement for preventive care and by facilitating access to care.

Local expertise in clinical care has been nurtured by the support for clinical activities provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), under the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Assuring linkages to these clinical providers is a key function of the PHSC. Under the financial restraints of recent years, jurisdictions will need to determine the degree of their involvement with individual HIV-infected pregnant women. Recent national health-care reform may enhance EMCT through reimbursement for preventive care and by facilitating access to care.

Because MCT is frequently the result of failures of local health systems, CDC has worked with partners to develop a community-based, continuous quality improvement methodology. This methodology is modeled after the HRSA-funded Fetal-Infant Mortality Review (FIMR) program. CDC funds the FIMR-HIV Prevention Methodology (FHPM) National Resource Centerexternal icon to support scale-up of this methodology in new sites such as health departments funded through CDC’s HIV Prevention cooperative agreements. With consent, FHPM summarizes the experience from the mother’s perspective through an interview and medical records abstraction. This de-identified information is presented to a multidisciplinary case review team to assess missed opportunities related to MCT and to develop recommendations for local system improvements. These recommendations are presented to community action teams of locally recognized persons who are in a position to implement the suggested system improvements. Cases of MCT occur in diverse and ever-changing environments, so utilizing a proven methodology to assess and improve local systems is particularly important. Such systems improvements could also affect other perinatal infections (e.g., hepatitis B infection and syphilis) and maternal and child health services overall.

With consent, FHPM summarizes the experience from the mother’s perspective through an interview and medical records abstraction. This de-identified information is presented to a multidisciplinary case review team to assess missed opportunities related to MCT and to develop recommendations for local system improvements. These recommendations are presented to community action teams of locally recognized persons who are in a position to implement the suggested system improvements. Cases of MCT occur in diverse and ever-changing environments, so utilizing a proven methodology to assess and improve local systems is particularly important. Such systems improvements could also affect other perinatal infections (e.g., hepatitis B infection and syphilis) and maternal and child health services overall.

Research and Long-term Monitoring

The prevention regimens used are evolving and expose thousands of children to antiretroviral medications every year. Research to monitor the long-term safety and efficacy of interventions for both women and ARV-exposed children needs a long-term plan and sustained action.

Data Reporting

Accurate data reporting is necessary to direct the activities described above, and should include surveillance of all infants born to HIV-infected women (“perinatal HIV exposure”). Without exposure reporting, it is challenging if not impossible to understand progress or lack thereof toward the goal of EMCT.

This framework describes how health care and public health systems may interact to eliminate mother-to-child HIV transmission in the United States. Considering the multifaceted approach of the framework, as well as the current strain on resources, reaching elimination will require coordination and active collaboration across multiple agencies at the national, state and local level. However, preventing perinatal transmission at the individual level includes a series of clinical interventions. These interventions are outlined in the Perinatal HIV Prevention Cascade (Figure 2) adapted from the Institute of Medicine 1998 report, Reducing the odds: Preventing perinatal transmission of HIV in the United States.

Figure 1 – Framework to Eliminate Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission (EMCT)

Figure 2 – Perinatal HIV Prevention Cascade

Source Report: Institute of Medicine, 1998

1 Reproductive health and family planning services, preconception care, and universal HIV testing are essential components of EMCT and facilitate 2 comprehensive real-time case finding of all HIV-infected pregnant women. Real-time case finding enables: 3 comprehensive clinical care and social services for women and infants; 4 detailed review of select cases to identify and address missed prevention opportunities and local systems issues through continuous quality improvement; 5 research and long-term follow-up to develop and ensure safe, efficacious interventions for EMCT; 6 thorough data reporting for HIV surveillance and EMCT evaluation.

HIV and pregnancy

Every pregnant woman registered with the antenatal clinic must be tested for HIV twice - at the first visit and in the third trimester. If a positive or doubtful test for antibodies to HIV is detected, the woman is immediately sent for a consultation to the AIDS Center to clarify the diagnosis.

If a positive or doubtful test for antibodies to HIV is detected, the woman is immediately sent for a consultation to the AIDS Center to clarify the diagnosis.

Mother-to-child transmission of HIV is possible during pregnancy, more often in late pregnancy, during childbirth and while breastfeeding.

Without preventive measures, the risk of HIV transmission is up to 30%. The risk of infection of the child increases if the mother was infected within six months before the onset of pregnancy or during pregnancy, and also if the pregnancy occurred in the late stages of HIV infection. The risk increases with a high viral load (the amount of virus in the blood) and low immunity. An increase in the risk of infection of the child occurs with repeated pregnancies.

With proper preventive measures, the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection is reduced to 2%.

In this brochure you will find information on how to reduce the risk of infection of a child and on the timing of dispensary observation of a child at the AIDS Center.

Reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection

When contacting the AIDS Center, a pregnant woman receives advice from an infectious disease specialist, an obstetrician-gynecologist, a pediatrician; passes all the necessary tests (viral load, immune status, etc.), after which the issue of prescribing antiretroviral (ARV) drugs to the woman is decided. When ARV drugs are taken correctly, the amount of virus in the blood decreases and the risk of passing HIV to an unborn child is reduced. The choice of the regimen and the term of prescription of ARV drugs is decided individually. The safety of their use for the fetus and the pregnant woman herself has been proven. The medicines are given out free of charge according to the prescriptions of the doctors of the AIDS Center.

The effectiveness of drugs should be checked by the end of pregnancy (viral load laboratory test).

A pregnant woman must continue to be observed at the antenatal clinic at the place of residence.

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV includes 3 stages:

1 stage. Taking medication by a pregnant woman. Prevention should be started as early as possible, preferably from 13 weeks of gestation, with three drugs and continued until delivery.

Stage 2. Intravenous administration of an ARV drug to a woman during childbirth (“dropper”).

Stage 3. Taking medications for a newborn baby. Taking drugs by a child begins in the first 6 hours after birth (no later than 3 days). Most children receive zidovudine syrup at a dose of 0.4 ml per 1 kg of body weight twice a day (every 12 hours) for 28 days. In special cases, the doctor can add 2 more drugs to the child for prevention: viramune suspension - 3 days, epivir solution - within one week.

Births take place in maternity hospitals where the woman lives. Maternity hospitals in the Kostroma region are provided with all the necessary ARV drugs for prevention. The method of delivery (natural childbirth or caesarean section) is chosen by the general decision of the infectious disease specialist and obstetrician-gynecologist.

The method of delivery (natural childbirth or caesarean section) is chosen by the general decision of the infectious disease specialist and obstetrician-gynecologist.

Breastfeeding is one of the ways of transmission of HIV infection (not only breastfeeding, but also feeding with expressed milk).

Without exception, women with HIV should not breastfeed!

Timing of examination of children born to HIV-infected mothers in the first year of life.

Up to 1 year of age, the child is examined three times:

- In the first 2 days after birth, blood is taken in the maternity hospital for HIV testing by PCR (detects virus particles) and ELISA (detects antibodies - protective proteins produced by the human body for the presence of infection ) for delivery to the AIDS Center.

- At 1 month of life - blood is taken for HIV by PCR in a children's clinic or hospital, in the HIV prevention office at the place of residence (if you have not donated blood at the place of residence, this will need to be done at the AIDS Center at 2 months).

- At the age of 4 months - it is necessary to come to the AIDS Center to examine the child by a pediatrician and to test the blood for HIV by PCR. Also, the doctor may prescribe additional tests for your child (immune status, hematology, biochemistry, hepatitis C, etc.).

If you miss one of the examination dates, do not postpone it until a later time. At the age of 1 month and up to 1 year of life, the child must be tested for HIV by PCR at least 2 times!

What do the test results mean?

Positive blood test for HIV antibodies

All children of HIV-positive mothers are also positive from birth, and this is normal! The mother passes on her proteins (antibodies) in an attempt to protect the baby. Maternal antibodies should leave the blood of a healthy child by 1.5 years (on average).

Positive PCR result

This test directly detects the virus itself, which means that a positive PCR may indicate a possible infection of the child. An urgent appearance of the child in the AIDS Center for rechecking is required.

An urgent appearance of the child in the AIDS Center for rechecking is required.

Negative PCR

A negative result is the best result! Virus not detected.

- A negative PCR on the second day of a child's life indicates that the child most likely did not become infected during pregnancy.

- Negative PCR at 1 month of life says that the child was not infected during childbirth. The reliability of this analysis at the age of one month is about 93%.

- Negative PCR over 4 months of age - the child is not infected with a probability of almost 100%.

Examinations of children from 1 year of age.

If a child already has a negative blood test for HIV by PCR, the main method of research from the age of 1 year is the determination of antibodies to HIV in the child's blood. The average age when the child's blood is completely "cleared" of maternal proteins is 1.5 years.

- At the age of 1, the child donates blood for HIV antibodies at the AIDS Center or at the place of residence.

If a negative test result is obtained, repeat after 1 month and the child can be deregistered ahead of schedule. A positive or questionable result for HIV antibodies requires a retake after 1.5 years.

If a negative test result is obtained, repeat after 1 month and the child can be deregistered ahead of schedule. A positive or questionable result for HIV antibodies requires a retake after 1.5 years. - Over the age of 1.5 years, one negative HIV antibody result is enough to deregister the child if there are previous tests.

Deregistration of children

- Age of the child is over 1 year;

- Presence of two or more negative PCR tests over 1 month of age;

- Two or more negative HIV antibody tests over 1 year of age;

- Not breastfeeding in the last 12 months.

Confirmation of the diagnosis of HIV infection in a child

Confirmation is possible at any age from 1 to 12 months with two positive HIV PCR results.

In children older than 1.5 years, the diagnostic criteria are the same as for adults (presence of a positive blood test for antibodies to HIV).

The diagnosis is confirmed only by specialists from the AIDS Center.

Children with HIV infection are constantly under the supervision of a pediatrician of the AIDS Center, as well as in the children's polyclinic at the place of residence. HIV infection may be asymptomatic, but there comes a time when the doctor will prescribe treatment for the child. Modern drugs can suppress the immunodeficiency virus, thereby eliminating its effect on the body of a growing child. Children with HIV can lead a full life, visit any children's institutions on a general basis.

Vaccination

Children of positive mothers are vaccinated like all other children according to the national calendar, but with two exceptions:

- The polio vaccine must be inactivated (not live).

- Permission for BCG vaccination (vaccination against tuberculosis), which is usually given in the maternity hospital, you will receive from the pediatrician of the AIDS Center

Pediatric department phone: 8-9191397331 (from 0900 to 1500 except Thursdays).

We are waiting for you with your children only on Thursdays from 800 to 1400, on other days (except weekends) you can get a consultation from a pediatrician, find out the results of the child's tests from 0900 to 1600.

Your child's health is in your hands!

If you are HIV-positive and plan to have healthy children, you must visit the AIDS Center before you become pregnant!

If you are diagnosed with HIV infection during pregnancy, contact the AIDS Center as soon as possible in order to start timely preventive measures aimed at reducing the risk of HIV infection in future babies!

Tell friends:

Previous materialWomen and HIVNext materialReminder for planning pregnancy in discordant couples

Pregnancy and childbirth in HIV-positive women

A little more than thirty years have passed since the discovery and description of the human immunodeficiency virus, and in this relatively short period, HIV infection has not only reached the level of an epidemic, but has also significantly changed its prevalence. In recent years, there has been a transition of HIV infection from drug users and persons practicing homosexual contacts to the general population, which leads to an increase in the proportion of women among HIV-infected people. According to the latest data, women of reproductive age make up more than half of all HIV-positive women. The tragedy of recent years has been the increase in the number of HIV-infected pregnant women. In some Russian regions, the frequency of their detection has increased 600 times over the past 10 years.

In recent years, there has been a transition of HIV infection from drug users and persons practicing homosexual contacts to the general population, which leads to an increase in the proportion of women among HIV-infected people. According to the latest data, women of reproductive age make up more than half of all HIV-positive women. The tragedy of recent years has been the increase in the number of HIV-infected pregnant women. In some Russian regions, the frequency of their detection has increased 600 times over the past 10 years.

According to current concepts, the detection of HIV infection in a pregnant woman is an indication for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and not for termination of pregnancy. The desired pregnancy must be maintained, and the doctor must take all necessary steps to successfully carry out drug prophylaxis and other preventive measures.

Without preventive measures, mother-to-child transmission of HIV is 20–40%; the use of special preventive measures reduces the transmission of infection to 1–2%.

Ideally, every HIV-infected woman should receive pregnancy preparation, including reproductive and physical health assessments, STI testing, folic acid administration to both spouses. It is mandatory to consult an infectious disease specialist in order to correct antiretroviral (ARV) therapy. All pregnancy planning activities are carried out three months before the abolition of contraception.

When pregnancy occurs against the background of HIV infection, as well as when HIV infection is first detected during pregnancy, a woman is referred for a consultation by an infectious disease specialist at the Center for the Prevention and Control of AIDS in order to prescribe ARV drugs, taking into account the stage of HIV infection , the state of the patient's immune system and the effect of drugs on the fetus. Such centers operate in all regions of the Russian Federation.

The objective of prescribing ARV drugs during pregnancy is to suppress the reproduction of HIV in the woman's body as much as possible, and, as a result, reduce the risk of HIV transmission to the fetus.

A pregnant woman must clearly understand that the effectiveness of ARV prophylaxis is determined by the conscientiousness of fulfilling all medical prescriptions. It is important not only to strictly adhere to the prescribed regimen for taking medications, but also to regularly visit an infectious disease specialist to study the effectiveness of the prescribed therapy, the state of the immune system and the activity of the infectious process.

Screening is done every four weeks and includes CD4 count, viral load, clinical and biochemical blood tests.

Viral load testing 2 weeks before the expected date of delivery (36-38 weeks) is essential to select the method of delivery. According to WHO recommendations, if the viral load is above 1000 copies of HIV RNA per ml of blood plasma, a planned caesarean section is recommended at the 38th week of pregnancy.

When conducting vaginal delivery, preventive measures are mandatory to reduce the risk of infection of the newborn, including, among other things, continuing to take ARV drugs.