How much money do parents spend on their child

How Much Does It Cost to Raise a Child in the U.S.?

Raising a child can be an emotionally rewarding experience. But it can also be very costly. Statistics from the Brookings Institution, an economic think tank, show that the average middle-income family with two children will spend $310,605 to raise a child born in 2015 up to age 17. That’s a significant jump from the figure published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which estimated the overall cost to be $233,610 in 2017 (using 2015 dollars).

Brookings, which cited higher inflation for the rise, assumed an inflation rate of 4% from 2021 to 2032 when it calculated the new cost of raising a child.

If starting a family is in your plans, or if you already have kids, understanding the costs can make shaping your financial plan easier. We highlight some of the key costs associated with raising children, including housing (the top cost), food, childcare, and others.

Key Takeaways

- Middle-income parents will spend an average of $310,605 by the time a child born in 2015 turns 17 years old in 2032.

- The largest expense associated with raising a child is housing, followed by food.

- The cost of childcare varies widely and depends on where you live.

- The good news is that each additional child costs less, thanks to economies of scale.

- The cost of raising a child doesn’t include costs associated with education.

Housing: 32% of Income

The largest expense associated with the cost of raising children is housing. This can easily make up a sizable chunk of a parent’s budget, especially when you factor in mortgage or rent payments, taxes, insurance, repairs, utilities, maintenance, and basic household goods.

According to Consumer Expenditures Data for 2020, the typical household spends a mean amount of $21,409.19 on housing per year. Meanwhile, U.S. Census Bureau data shows that the median household income in the United States was $67,521 in 2020. Going by these numbers, you could assume that families with children spend roughly 32% of their income on housing.

These numbers offer a broad idea of how much families pay for housing. However, it’s important to keep in mind that housing costs can vary based on a number of factors, including:

- Geographic area

- Type of dwelling (single-family home, townhouse, condominium, etc.)

- Whether the family rents or owns their home

- Size of the home as it corresponds to family size (i.e., number of bedrooms required based on the number of children and adults)

- Age of the home

Economic conditions can also influence the cost of housing for families. When housing prices rise, that can make it more expensive for families to purchase a home. Likewise, rising inflation can push up rental prices along with increased prices for other consumer goods.

Housing assistance programs can help by providing money to supplement the cost of rent for eligible lower-income families.

Food: 27% of Income

Sustenance tends to be the next major cost for parents. The amount that a family spends varies. It is based on the number of children in the home, household income, geographic region, and preferred diet.

The USDA offers some perspective on how much families may spend on food. Each month, the USDA issues monthly reports on food costs at four different levels: thrifty, low-cost, moderate-cost, and liberal. These reports consider different household sizes with children of different ages. The reference family consists of a male and a female adult ages 19 to 50 and two children in the 6- to 8-year-old range and the 9- to 11-year-old range.

Here’s how the average food spending numbers for the reference family add up on a monthly basis, as of July 2022:

- Thrifty plan: $951.70

- Low-cost plan: $1,025.90

- Moderate plan: $1,276.90

- Liberal plan: $1,543.40

At the low end, a typical family of four spends about $11,500 per year on food at home. At the high end, they spend more than $18,500 per year on food. That’s around 27% of their income if you’re going by the median household income of $67,521 mentioned earlier.

Spending money on food away from home, including dine-in meals at restaurants, takeout meals, and snacks purchased at convenience stores, can inflate food costs for families.

Childcare: 12% to 29% of Income

Childcare costs can easily take up a sizable part of parents’ budgets each year. The cost of childcare in the U.S. ranges from $5,436 to $24,243 annually, according to 2020 figures from the Economic Policy Institute. How much you pay for childcare can depend on the type of care needed, the number of children who require care, and where your family lives.

For instance, Washington, D.C., residents pay the most. Infant care costs $24,243 annually, which represents about 29% of the median family income for parents in the area. Meanwhile, parents in Mississippi pay the least. Annual childcare amounts to $5,436 for an infant and $4,784 for a 4-year-old in that state. That represents roughly 12% of the median family income for the state.

Day care centers may give a discount if you have more than one child enrolled.

What Else Do Families Spend Money on?

Aside from housing, food, childcare and education, there are other costs associated with raising children that are important to budget for. Some of the most common things that parents may pay for to raise kids include:

- Transportation

- Healthcare and insurance

- Clothing

- Extracurricular activities

- Sports and hobbies

- School fees for field trips, activities, fundraisers, etc.

- Family trips or vacations

Some of these items could be considered necessary, while others may be wants. How much you spend on these things (if you do at all) can depend on the number of kids you have and what your budget allows. It’s important, though, to consider each and every budget item when determining your personal cost of raising children.

$310,605

The total cost to raise a child born in 2015 to age 17 after you factor in an inflation rate of 4%.

The Good and Bad News

There is some good news when it comes to the cost of raising a child in America. Economies of scale also apply to the number of children you have. The USDA points out that each additional child costs less because siblings can share a bedroom and a family can buy food in larger, more cost-effective quantities. And while your offspring might not necessarily like it, clothing and toys can be handed down, and older siblings can often babysit younger ones.

Now for the bad news: The numbers we mentioned above don’t account for the cost of a college education. Higher education can add to the total for parents who help pay for their children’s college costs. How much you pay for college can depend on whether your child:

- Attends a two- or four-year school

- Goes to a public or private university

- Is charged in-state or out-of-state tuition rates (at public universities)

The average annual cost (in-state) for the 2021–2022 academic year comes in at $22,690 for a public college and $51,690 for a private college, according to the College Board. Keep in mind that these figures include the cost of tuition, fees, and room and board. That means saving early and taking advantage of 529 plans or other investment vehicles to keep kids from graduating with a large amount of debt.

Strategies to Reduce Costs When Having a Child

Raising a child can be an emotional roller coaster. Ask any parent, and they’ll probably tell you that there are ups and downs. We understand that the costs associated with the responsibilities of being a parent and raising a child can be draining. So we’ve highlighted a list of tips that you may want to consider to help you reduce your expenses:

- Plan ahead. It’s important to have a good plan in place. This principle is very important with anything you do that costs you money. If you want to have a child and/or are expecting, it’s important to get your affairs in order sooner rather than later. Good planning can keep you one step ahead of the game.

- Set aside money for your child. Save money in an account meant just for your child in the same way you would for a rainy day, a major purchase, or retirement. It could be a savings account or a long-term investment vehicle. Dip into this fund if and only when the need arises for expenses related to your child. You should also take advantage of special accounts like 529 plans.

- Look for parent-friendly tax credits and deductions that can reduce your tax liability or help you get some money back, like the Child Tax Credit.

- Less is often more. Using some restraint can help you cut down costs, especially in the beginning. After all, babies don’t need much other than food, clothing, and a place to sleep.

- Think about the must-haves for your kids rather than the needs. You can probably do without anything that falls into the latter category. Ask yourself whether your 12-year-old really needs the latest gaming console when the last one works perfectly fine.

- Think sustainably. Consider recycling and secondhand. Consider reaching out to family and friends about any clothing that they’re no longer using. Use cloth diapers rather than disposable ones. This will not only help you save money but also can help you reduce your carbon footprint.

What is the average cost of raising a child in the United States?

While it can vary due to geography and the cost of childcare, $310,605 is the average amount spent on raising a child born in 2015 to age 17. This amount does not include the cost of paying for higher education, which can easily add $80,000 to $100,000+ per child to the total.

How do the expenses of child rearing break down?

Housing is the biggest expense associated with raising kids, followed by paying for food. Following those two categories of expenses, parents spend the most on childcare, transportation, healthcare, clothing, and miscellaneous spending.

What are the major costs of raising a child in the U.

The major cost of raising a child is housing. This is followed by food. However, some of the other key expenses that most parents don’t think about right off the bat include education.

How can I reduce the costs of raising my children?

Some of the best ways to reduce the costs of raising a child or children include proper planning and saving exclusively for the little ones. Other tips include looking for parent-friendly tax benefits and keeping a less-is-more attitude in mind. Parents can also keep a check on their budgets by recycling and using secondhand clothing. And of course, try to do away with the wants and stick with the must-haves, as the former are often dispensable.

Which state has the lowest childcare costs?

According to the Economic Policy Institute, the state with the lowest childcare costs is Mississippi. Parents pay an average of $5,436 for an infant and $4,784 for a 4-year-old in childcare each year.

The Bottom Line

Nobody wants to think of their children as just an expense, but the financial side of child rearing can’t be ignored. Understanding the numbers can help you determine if you can afford to have children if you don’t have them yet. And if you already have kids, being cost-conscious can help you to make smarter financial decisions so that you can stretch every dollar.

The Cost of Raising a Child

Posted by Mark Lino, Economist at the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion in Food and Nutrition

Feb 18, 2020

Families Projected to Spend an Average of $233,610 Raising a Child Born in 2015.USDA recently issued Expenditures on Children by Families, 2015. This report is also known as “The Cost of Raising a Child.” USDA has been tracking the cost of raising a child since 1960 and this analysis examines expenses by age of child, household income, budgetary component, and region of the country.

Based on the most recent data from the Consumer Expenditures Survey, in 2015, a family will spend approximately $12,980 annually per child in a middle-income ($59,200-$107,400), two-child, married-couple family. Middle-income, married-couple parents of a child born in 2015 may expect to spend $233,610 ($284,570 if projected inflation costs are factored in*) for food, shelter, and other necessities to raise a child through age 17. This does not include the cost of a college education.

Where does the money go? For a middle-income family, housing accounts for the largest share at 29% of total child-rearing costs. Food is second at 18%, and child care/education (for those with the expense) is third at 16%. Expenses vary depending on the age of the child.

As families often need more room to accommodate children, housing is the largest expense.We did the analysis by household income level, age of the child, and region of residence. Not surprising, the higher a family’s income the more was spent on a child, particularly for child care/education and miscellaneous expenses.

Expenses also increase as a child ages. Overall annual expenses averaged about $300 less for children from birth to 2 years old, and averaged $900 more for teenagers between 15-17 years of age. Teenagers have higher food costs as well as higher transportation costs as these are the years they start to drive so insurance is included or a maybe a second car is purchased for them.

Regional variation was also observed. Families in the urban Northeast spent the most on a child, followed by families in the urban West, urban South, and urban Midwest. Families in rural areas throughout the country spent the least on a child—child-rearing expenses were 27% lower in rural areas than the urban Northeast, primarily due to lower housing and child care/education expenses.

Child-rearing expenses are subject to economies of scale. That is, with each additional child, expenses on each declines. For married-couple families with one child, expenses averaged 27% more per child than expenses in a two-child family. For families with three or more children, per child expenses averaged 24% less on each child than on a child in a two-child family. This is sometimes referred to as the “cheaper by the dozen” effect. Each additional child costs less because children can share a bedroom; a family can buy food in larger, more economical quantities; clothing and toys can be handed down; and older children can often babysit younger ones.

This report is one of many ways that USDA works to support American families through our programs and work. It outlines typical spending by families from across the country, and is used in a number of ways to help support and education American families. Courts and state governments use this data to inform their decisions about child support guidelines and foster care payments. Financial planners use the information to provide advice to their clients, and families can access our Cost of Raising a Child calculator, which we update with every report on our website, to look at spending patterns for families similar to theirs. This Calculator is one of many tools available on MyMoney.gov, a government research and data clearinghouse related to financial education.

This year we released the report at a time when families are thinking about their plans for the New Year. We’ve been focusing on nutrition-related New Year’s resolutions – or what we are referring to as Real Solutions - on our MyPlate website, ChooseMyPlate.gov. This report and the updated calculator can help families as they focus on financial health resolutions. This report will provide families with a greater awareness of the expenses they are likely to face while raising children.

In addition to the report and the calculator, we also have a dedicated section on ChooseMyPlate.gov that provides tips and tools to aid families and individuals in making healthy choices while staying on a budget. For strategies beyond food, our friends at MyMoney.gov offer a wealth of information to help Americans plan for their financial future.

For more information on the Annual Report on Expenditures on Children by Families, also known as the cost of raising a child, go to: www. fns.usda.gov/resource/expenditures-children-families-reports-all-years.

*Projected inflationary costs are estimated to average 2.2 percent per year. This estimate is calculated by averaging the rate of inflation over the past 20 years.

Editor’s Note (March 8, 2017): The comparison of rural vs. urban northeast child care and education value has been updated.

Visit the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s MyMoney.gov for more resources to ensure financial well-being this New Year’s season!Category/Topic: Food and Nutrition

Tags: children choosemyplate. gov CNPP Cost of Raising a Child economics Expenditures on Children by Families Food and Nutrition mymoney.gov MyPlate Research

How to teach adopted children how to manage money

A child who grew up in an orphanage may not know anything about the value of money, that its quantity is limited, that it is earned by labor and belongs to someone. Therefore, adopted children can take and spend other people's money without asking, without realizing their misconduct.

Many of them learn their rights and parental duties quickly and perfectly… But very selectively: they remember what their parents “owe” to them. Grown up children know well: foster parents receive money for their maintenance, and they expect that this money will be spent on what they want and demand.

Not knowing the prices and not knowing how to plan expenses, children may ask for more and more, as if there will always be enough money.

In order to teach a child the right attitude to money, you need to learn a few rules.

During the adaptation period - special conditions

It is not worth it, especially at the very beginning of the adaptation period, to take your child to shops with a large assortment of goods and buy everything he wants. No matter how much you want to arrange a grand celebration for an orphan, it is better to refrain from excesses. First of all, to keep his eyes open. A huge variety of toys or goodies can cause a child who is not used to such abundance, a lot of stress.

In addition to unpleasant reactions, such a “holiday” may turn into delayed difficulties for parents in the near future. After all, the holiday once ends, and weekdays begin, for which the adopted child will not be ready. Having perceived the holiday as a new way of life, he will resist any manifestations of "everyday existence".

Borders

Foster children quickly learn the science of demanding: “You owe/must buy me!”. Moreover, in their requirements, they are not able to take into account the volume of the family budget and correlate them with their desires. Dimensionless unreasonable demands should be extinguished in the bud, according to the tone expressed to the parents “You owe / owe me”.

If a child tells a parent something like "This is my money," it is permissible to give him an excursion into child psychology. A child - neither blood nor adopted - is simply unable to be his own master. If children could manage their own money, there would be no need for parents and guardians: orphanages would give their pupils what they were entitled to and would let them go home before reaching adulthood. Unfortunately, practice shows that even graduates of orphanages often extremely unreasonably and rapidly spend the amounts given to them upon leaving the institution and remain on a starvation ration.

Another important principle of respecting the boundaries - no "trading"! For assessments, actions to maintain one's own regimen and hygiene, and household chores - all this cannot be paid for by a child, especially one who has experience as an orphan. Children quickly pick up "market relations" in the family as an opportunity to manipulate adults, getting what they want from them. If a parent starts paying a child for good school grades, very soon the interest in learning will be replaced by an interest in “earning money”, and the “salary” itself can be enough for a quarter of twos, if it is enough for chocolate and chewing gum.

Parents will have to take care of themselves much more carefully than before the adoption of the child. For example, to make it a habit not to leave money and valuables anywhere, so as not to tempt the child, not to provoke him to steal. After all, it is much easier and more pleasant to start teaching good things while everyone has a positive charge towards each other than to correct the “difficulties” of behavior, entangled in conflicts and unpleasant feelings.

Graduality

The principle of gradualness is important to observe in mastering any science. Learning to appreciate and spend money also needs to be done gradually.

First, when visiting stores with your child, you need to explain to him the value and usefulness of certain goods, pay attention to the composition, quality, and shelf life. At the next stage, it is useful to involve the child in the discussion of the acquisition of those things, the need for which is doubtful. Such an inclusion will help him create his own ideas about the expediency of purchases, about the ratio of price and quality.

In parallel with the discussion, it is useful to give the child some amounts for expenses, determining the part that he can spend on what he wants, and the other part - for the needs of the family (bread, battery, light bulb, glue). The older the child and the higher his ability to spend the money received wisely, the larger the amounts given out can be. But poorly thought-out expenses should not be “punished” by a decrease in subsidies - they must be discussed: why this or that thing was bought; whether the purchase was really necessary; why then was not enough for something necessary; how to redistribute funds. Thus, the child will be able to form their own internal constraints.

Learn to appreciate material values and labor

Children in the orphanage do not have their own things, so they cannot learn to appreciate them. A laundry item is not always returned to the child who wore it. Yes, and the laundry itself, like all other household work, remains out of sight for them.

Foster children may deliberately damage and "lose" their belongings in order to get new ones. The child seems to be sure that everything is “taken from the store”, and parents are obliged to buy what he asks. In this case (where possible), he should be given the opportunity to fix (repair, clean, etc.) himself, to bring the damaged item or do without the lost one.

Children from orphanages do not imagine the entire chain of production of many products and goods, so the value of most of them escapes the child. We have to explain such seemingly obvious things as the production of bread or the appearance of light in a light bulb.

It is also necessary to explain the value of labor, which completely eludes children from orphanages. Having learned to appreciate human labor, the child will look at money differently: as the equivalent of labor.

Open

The financial affairs of the family should not be a secret for a child. An adopted child is a member of the family just like the rest. If he is removed from discussing the main points in the life of the family, he will not feel fully accepted, will not strive to do something for the home and family. Why delve into everyday issues if the parents decide everything themselves?

Evaluation of success

Managing a budget is as much a skill as playing a musical instrument. Perhaps even more difficult. Any skill takes time to master and consolidate. In this difficult process, a positive assessment, especially from loved ones, helps a lot. When parents notice at least a small success of a child, this becomes a powerful incentive for him to further development.

Money and feelings - in different pockets

And the last. Money "loves" calm handling, prudence and rationality. If the foster family has difficulties in understanding due to the careless actions of the child and a conflict is brewing, it is better to gather all the will into a fist and wait. Money issues are not resolved on emotions. Let the child, without consulting, buy a toy that is too expensive - this is his decision and his means. The job of parents is only to help the child comprehend the mistake and cope with its consequences on his own.

Elena Turlina

Children and money: how much pocket money does a child need and should he control what he spends it on?

I am Mom

06. 10.2022, 10:04

Tatyana Pisareva

Photo: Pixabay

The school year began, and children more often have a desire to buy something: Pies in school canteen, a new line or a trendy T-shirt. How much pocket money should a child have, is it acceptable to pay for diligent study or housework, is it necessary to control what a child spends money on - sooner or later every parent asks himself these questions. How to solve this problem in an ordinary family? Understanding "MK Estonia".

Schoolchildren in Moscow and the Moscow region will be taught the correct handling of money in grades 1-9 from September, TASS reported. Financial literacy will be given attention in the lessons of mathematics, the world around us, social studies, geography and computer science. In Estonian schools, the younger generation is not yet taught money tricks in such a volume, with the exception of classroom hours and campaigns to improve financial literacy.

According to the 2020 data of the Ministry of Education, young people in Estonia receive information about finances primarily from their parents and relatives (95%), as well as on the Internet (82%). In general, there is little talk about money in families in Estonia – for example, 40% of young people have never discussed budget or economic news with their families. However, Estonian students are very independent in organizing their financial affairs - 87% decide what to spend their money on, 82% are responsible for their money matters, 75% have a bank card.

“Why do you need so much money?”

Parents usually begin to hear requests for pocket money when they start school. The child has more independence, as well as more temptations.

„Well, what will you buy, Kitty? Well? After all, you have no imagination, ”Ostap Bender teased Ippolit Matveevich in“ 12 Chairs ”, which drove the latter into a frenzy. Many parents argue in the same way, who believe that children do not need pockets at all - they will buy everything they need anyway, and if you give children money, they will waste them on nonsense. But is it?

A study commissioned by the Swedbank Financial Clearing House in 2020 by Norstat, which involved 1,104 parents of children aged 5 to 23, provided a detailed answer to the question of what children buy with their pocket money.

According to a study, teenagers aged 5 to 19 spend most of their pocket money on sweets. Children under 10 also use their pocket money to buy toys, 11–15 year olds spend pocket money not only on treats but also on entertainment, and for 16–19 year olds, clothes and shoes are another important expense item besides sweets. . 40% of children aged 5-6 save money to buy toys. Adolescents aged 7-19 save the most pocket money for the purchase of such equipment as a smartphone, computer, tablet, etc. 20-23-year-olds save mainly for the purchase of equipment and travel.

Don't be silent about money

According to Victoria Saard, SEB's Private Clients Sales Manager, children grow up to be more independent if they are taught from an early age the value of money and how to use it wisely. Parents are the best teachers and role models in dealing with money.

“Teaching a child to be financially self-reliant is much more beneficial than just giving them cash,” Saard says. “Therefore, it is important to start as early as possible, and parents could try to explain to the child the nature of money as soon as he becomes interested in it. Three-year-olds are happy to collect coins in a piggy bank to exchange them for lollipops in the store. Older children can already be taught good habits with the help of ordinary pocket money.

The biggest disservice you can do your child is to keep quiet about money. It gives the kid the wrong message that money is either not important or should be feared and never mentioned.”

Parents play an important role in teaching money wisdom and shaping attitudes towards money, says Mari-Liis Jaeger, head of the Swedbank Institute of Finance. Only 21% of parents had a thorough conversation with their child about the value, use, planning and saving of money before giving pocket money. 15% of parents believe that life will teach the child.

Experts advise to involve children in family finances in accordance with their understanding. A younger child may well learn that it is not necessary to buy a candy or a toy every time he goes to the store. An older child can take part in the discussion of the family budget with great pleasure and understand where the money goes: if we pay utilities and bills, then this amount will remain for food and other expenses.

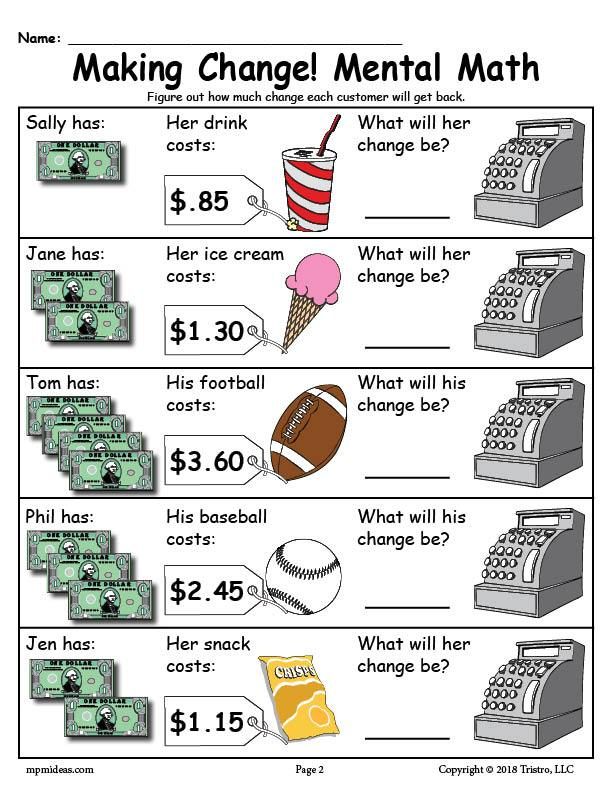

How much to give?

Disputes often break out in social networks, what amount is considered the most adequate as pocket money. Of course, it is impossible to calculate the ideal amount either with a calculator or a heated argument: each family takes into account different factors when solving this problem: someone takes into account school performance and / or housework, someone gives pocket money with the condition that the child he will pay for the services of a tutor or buy himself clothes. And, of course, age plays an important role.

Pocket money is given regularly, once or twice a month, only from the age of 11, says Mari-Liis Jaeger, head of the Swedbank Institute of Finance. Pocket money is usually the only income for a child, and the regularity of receiving it, both the agreed amounts and the terms, helps the child learn how to handle money and think about how to plan his expenses and save for desires.

A study commissioned by the Swedbank Financial Clearinghouse showed that children aged 11–15 receive pocket money most often for grades and well-done housework, while children aged 5–6 receive pocket money for good behaviour.

940 people took part in a recent poll organized by Swedbank on Facebook. According to this survey, 14% of parents give their children up to 10 euros per month, 35% - 11-20 euros, 12% - 21-30 euros, 4% - 41-50 euros and 7% - more than 50 euros per month. 6% of parents do not give pocket money to their children, 10% put money on a children's card from time to time, 1% prefer to give cash.

Survey organized by SEB shows that the vast majority of children aged 7-10 (65%) receive pocket money up to 20 euros, almost half of children aged 11-14 also have pocket money up to 20 euros per month. At the same time, the amount of pocket money for 15-17-year-olds is mostly (63%) in the range of 21-80 euros per month.

The child is older, the control is less

The younger the children, the more parents worry about the financial situation of their child.

Many children take their first steps in self-management of their finances when they go to school - usually that's when they start getting regular pocket money and start using a bank card. Using a bank card is safer, easier and easier to control for both parents and children compared to cash, experts say. The parent can set both daily and monthly limits for cash withdrawals and payments in the store using a bank card. If it happens that the child loses a bank card, the money will not be lost - the lost card can be blocked and a new one can be ordered by phone.

„An excellent helper in teaching children financial skills is an Internet bank or a mobile application, with the help of which children can manage their own money by paying with a card. For example, you can check the account balance immediately after making a payment and see how much was spent in the current month, advises Victoria Saard. – Another advantage is bank statements. If you have agreed with your child how much of his income he plans to spend on daily needs and how much to save for the purchase of something more expensive, after a month or another agreed period of time, you can analyze together whether the agreement is being observed, what expenses were unnecessary and how much you could save money without them. It's also good to let kids spend their pocket money as they see fit sometimes so they can learn from their mistakes. It is better if they make a few mistakes per euro than to learn from much larger sums in the future.”

Personal experience - children

Artem, 15 years old

I receive 15 euros per card every month and, of course, I would like to receive more, because it is difficult to put aside such an amount for something really valuable - cool headphones, for example. But it happens that parents pay a bonus - for example, as a sign of encouragement, if there were only good grades during the month. Or they offer to do some work for a fee - for example, wash our car.

Marina, 10 years old

My parents put money on my card every month and put all the money I get for my birthday, but I almost never spend my money, because dad and mom buy me anyway, which I really -really want to.

Mia, 15 years old

I don't always have time to eat at home, sometimes training, sometimes a language school, sometimes a music school. That's why I spend a lot of my money on food. Probably, this is not very correct, because the parents are already obliged to feed the child, and pocket money should go to my personal needs. Parents transfer 20–30 euros per month.

Pavel, 7 years old

My mother gives me 5 euros every Monday. I can buy something in the cafeteria because school food is not always tasty.

Kristina, 18 years old

At my age, it's already embarrassing to ask for pocket money, because you can hear - go and earn money yourself. I try to earn money, I help kids I know with lessons, their parents pay. Well, sometimes parents throw up twenty, but irregularly.

Personal experience - adults

Victoria

In grades 1-2, a child could ask for and receive some money. In the 3rd-4th grade, we gave him 5 euros a week, he still spent little, but at the same time he collected money for big purchases. Last school year in the 5th grade, the amount of pocket money was 10 euros per week, this year it will be the same.

Kristina

Children aged 9 and 13. Both receive 20 euros at the beginning of the month and decide for themselves whether to save or collect. The older one prefers to save, while the younger one distributes the money so that it lasts until the end of the month.