How long was the one child policy in china

China's 'one-child policy' left at least 1 million bereaved parents childless and alone in old age, with no one to take care of them

A child’s death is devastating to all parents. But for Chinese parents, losing an only child can add financial ruin to emotional devastation.

That’s one conclusion of a research project on parental grief I’ve conducted in China since 2016.

From 1980 to 2015, the Chinese government limited couples to one child only. I have interviewed over 100 Chinese parents who started their families during this period and have since lost their only child – whether to illness, accident, suicide or murder. Having passed reproductive age at the time of their child’s death, these couples were unable to have another child.

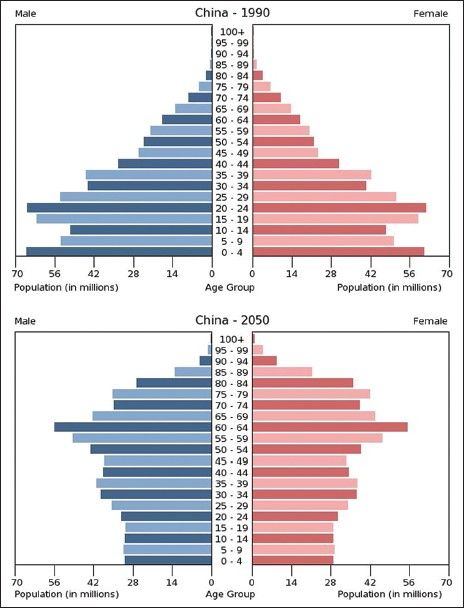

In 2015, the Chinese government raised the birth limit to two, an effort to reverse declining birthrates and to rejuvenate an aging population. In May 2021, it announced that Chinese families could have up to three children.

The new “three-child policy” received generally lukewarm responses in China. Many Chinese couples say they prefer not to have multiple children due to the rising cost of child rearing, how it would complicate women’s professional aspirations and declining preference for a son.

The childless parents I interviewed told me they felt forgotten as their government moves further away from the birth-planning policy that left them bereaved, alone and precarious in their old age – in a country where children are the main safety net for the elderly.

Having and losing an only child

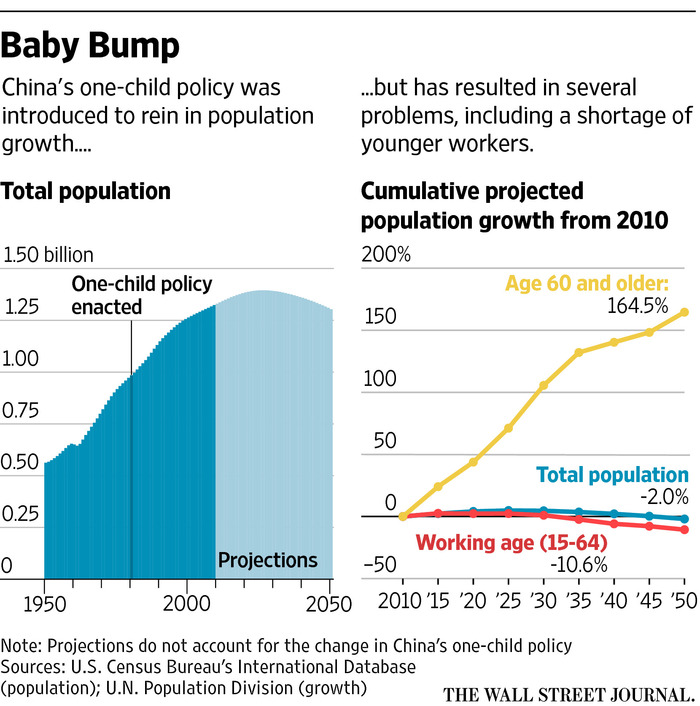

China’s one-child policy was a massive social engineering project launched to slow down rapid population growth and aid economic development efforts.

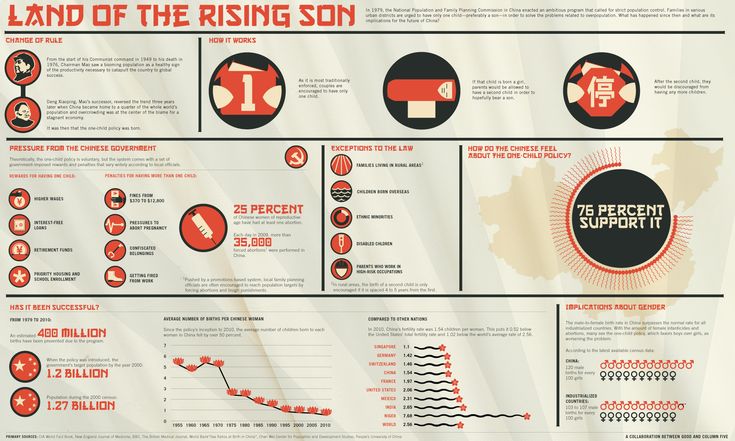

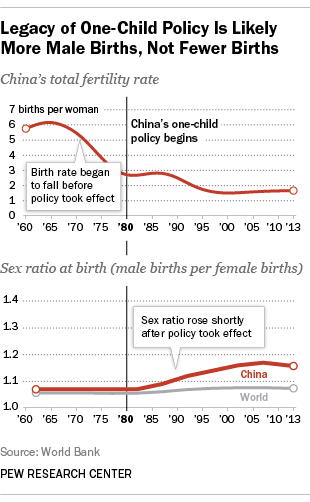

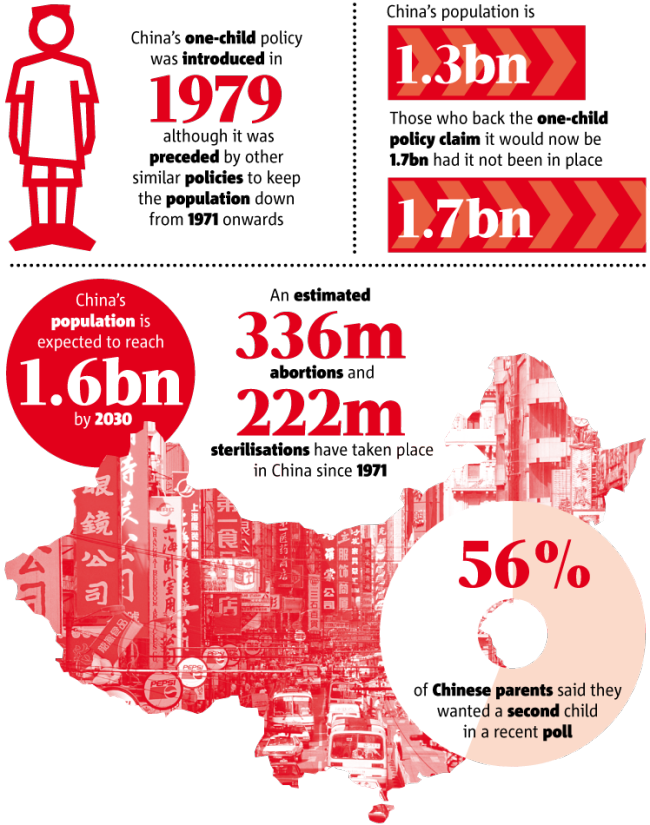

Until the early 1970s, most Chinese women had at least five children. By 1979, China’s population had nearly reached 1 billion – up from 542 million in 1949. The Chinese government claimed that the one-child limit prevented 400 million births in China, although this calculation has been disputed as an exaggeration.

A family strolls in Beijing, 1972. AP Photo/Horst Faas

AP Photo/Horst Faas The birth limit was unpopular at first.

“Back then, we wanted to have more children,” said a bereaved mother who was in her 60s when I interviewed her in 2017. “My parents had an even harder time accepting that we were allowed to have only one child.”

To enforce the unpopular one-child policy, the Chinese authorities designed strict measures, including mandatory contraception and, if all else failed, forced abortion.

Those who violated the policy paid a financial penalty, and children from unauthorized births often could not be registered for citizenship status and benefits. Parents who worked for the government – and under China’s economic system, many urban workers did – risked losing their job if they had more than one child.

Several bereaved mothers told me that they had gotten pregnant with a second or third child in the 1980s or 1990s but had an abortion for fear of job loss.

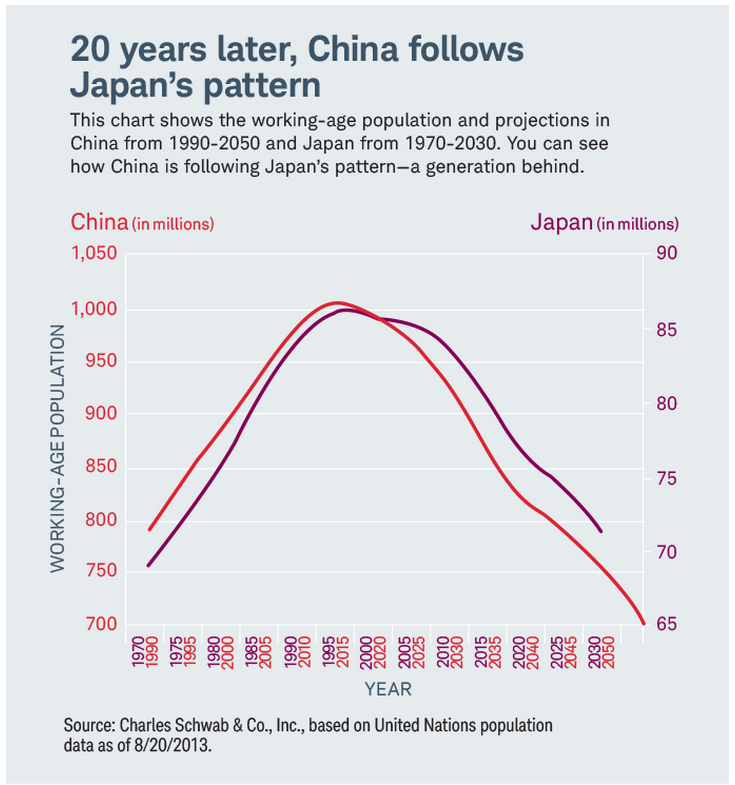

The one-child policy, while painful, contributed to an age structure that benefited the economy: The large working-age population born before and after it grew rapidly compared to the country’s younger and older dependent population.

This “demographic dividend” accounted for 15% of China’s economic growth between 1982 and 2000, according to a 2007 United Nations working paper.

An uncertain old age

Yet China’s one-child policy also created a risk for couples: the possibility of becoming childless in old age.

The original caption of this 1994 photo accompanying an article on China’s one-child policy was: ‘A baby is fed by its mother. The child is probably never to have a sister or brother.’ Peter Charlesworth/LightRocket via Getty Images“Families with an only child are walking on a tightrope. Every family can fall off the tightrope at any moment” if they lose their only child, one bereaved mother explained to me.

“We are the unlucky ones,” she said.

In China, where the pension and health care systems are patchy and highly stratified, adult children are the main safety net for many aging parents. Their financial support is often necessary after retirement.

It is estimated that 1 million Chinese families had lost their only child by 2010. These childless, bereaved parents, now in their 50s and 60s, face an uncertain future.

Due to the country’s longstanding tradition of filial piety, children also have a moral obligation to support their aging parents. Parental care is actually the legal responsibility of children in China; it is written into the Chinese Constitution.

This safety net does not exist for parents who lost the only child the government would let them have.

Help, but not enough

Over the past decade, groups of bereaved parents have negotiated with the Chinese authorities to demand financial support and access to affordable elder care facilities. Those I interviewed said they had fulfilled their obligation as citizens by abiding by the one-child rule and felt the government now had the responsibility to take care of them in their old age.

A bereaved parent of the one-child era shows a picture of her late son. William Wan/The Washington Post via Getty Images

William Wan/The Washington Post via Getty Images Eventually, the authorities responded to their grievances.

Starting in 2013, the government has initiated multiple programs for bereaved parents, most notably a monthly allowance, hospital care insurance and in some regions subsidized nursing home care.

However, bereaved parents told me that these programs were insufficient to meet their elder care needs.

For example, adult children often take care of their parents during hospitalization, bathing them and buying meals. Private care aides can charge up to US$46 a day, or 300 yuan, to do these tasks. In regions that now provide government-paid hospital care insurance for childless parents, most plans cover between $15.50 to $31 – about 100 to 200 yuan – daily for a care aide, based on my research.

Other people I interviewed worried about the high cost and limited availability of quality nursing homes in many regions. China’s elder care facilities cannot meet the demand of its aging population, and living in these facilities is not covered by insurance.

China’s controversial one-child policy is history, but its legacy may depend on how the Chinese authorities treat the grieving parents left in its wake.

[The Conversation’s Politics + Society editors pick need-to-know stories. Sign up for Politics Weekly.]

One-child policy | Definition, Start Date, Effects, & Facts

Top Questions

What is the one-child policy?

The one-child policy was a program in China that limited most Chinese families to one child each. It was implemented nationwide by the Chinese government in 1980, and it ended in 2016. The policy was enacted to address the growth rate of the country’s population, which the government viewed as being too rapid. It was enforced by a variety of methods, including financial incentives for families in compliance, contraceptives, forced sterilizations, and forced abortions.

When was the one-child policy introduced?

September 25, 1980, is often cited as the official start of China’s one-child policy, although attempts to curb the number of children in a family existed prior to that. Birth control and family planning had been promoted from 1949. A voluntary program introduced in 1978 encouraged families to have only one or two children. In 1979 there was a push for families to limit themselves to one child, but that was not evenly enforced across China. The Chinese government issued a letter on September 25, 1980, that called for nationwide adherence to the one-child policy.

Birth control and family planning had been promoted from 1949. A voluntary program introduced in 1978 encouraged families to have only one or two children. In 1979 there was a push for families to limit themselves to one child, but that was not evenly enforced across China. The Chinese government issued a letter on September 25, 1980, that called for nationwide adherence to the one-child policy.

Why is the one-child policy controversial?

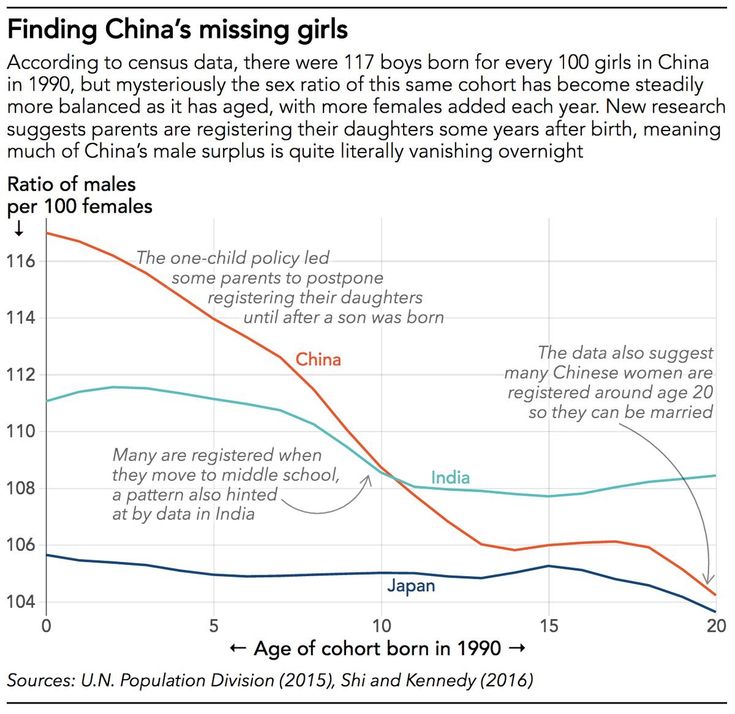

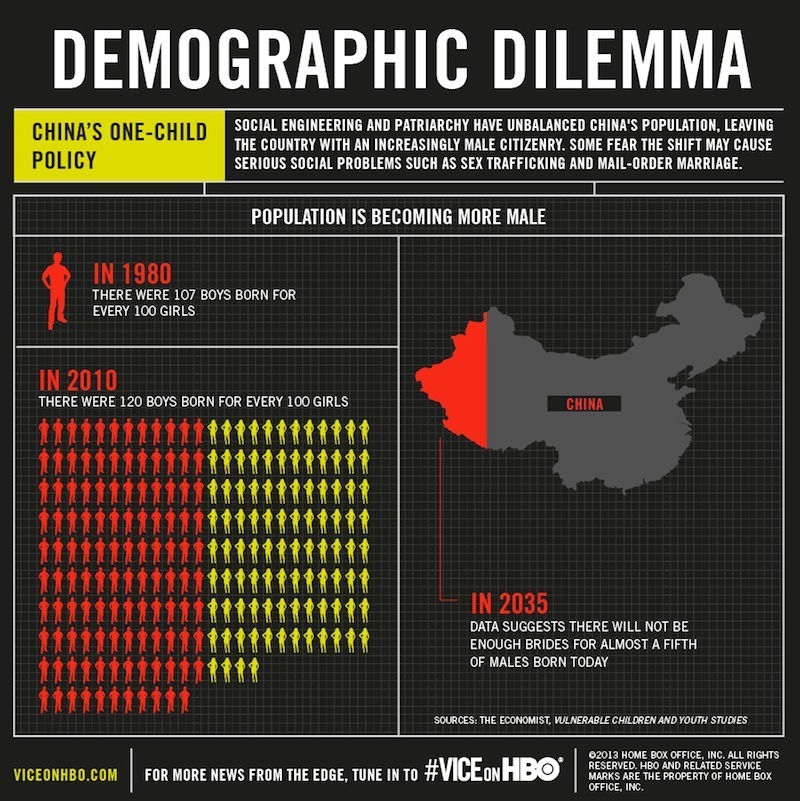

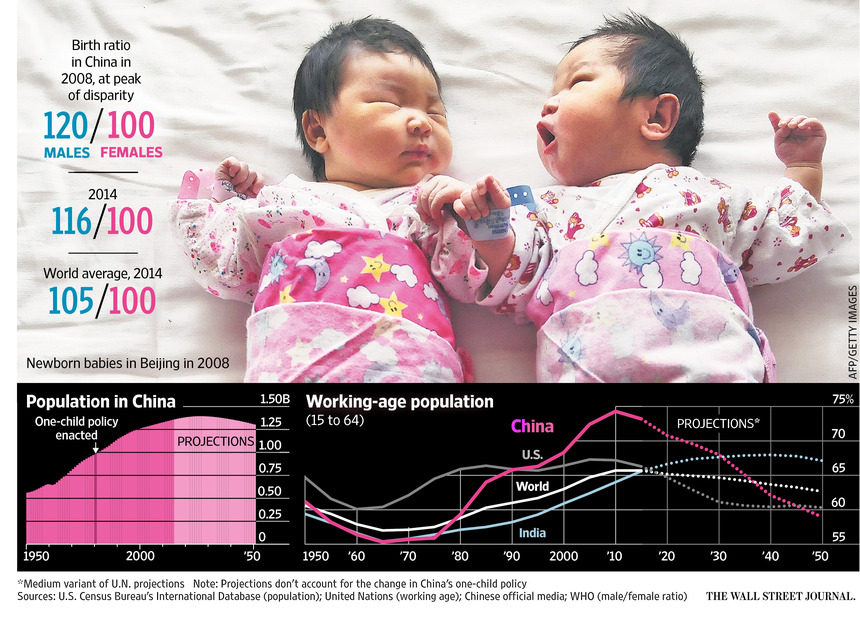

China’s one-child policy was controversial because it was a radical intervention by government in the reproductive lives of citizens, because of how it was enforced, and because of some of its consequences. Although some of the government’s enforcement methods were comparatively mild, such as providing contraceptives, millions of Chinese had to endure methods such as forced sterilizations and forced abortions. Long-term consequences of the policy included a substantially greater number of males than females in China and a shrinking workforce.

When did the one-child policy end?

The end of China’s one-child policy was announced in late 2015, and it formally ended in 2016. Beginning in 2016, the Chinese government allowed all families to have two children, and in 2021 all married couples were permitted to have as many as three children.

What are the consequences of the one-child policy?

There have been many consequences to China’s one-child policy. The country’s fertility rate and birth rate both decreased after 1980; the Chinese government estimated that some 400 million births had been prevented. Because sons were generally favoured over daughters, the sex ratio in China became skewed toward men, and there was a rise in the number of abortions of female fetuses along with an increase in the number of female babies killed or placed in orphanages.

After the one-child policy ended in 2016, China’s birth and fertility rates remained low, leaving the country with a population that was aging rapidly and a workforce that was shrinking. With data from China’s 2020 census highlighting an impending demographic and economic crisis, the Chinese government announced in 2021 that married couples would be allowed to have as many as three children.

With data from China’s 2020 census highlighting an impending demographic and economic crisis, the Chinese government announced in 2021 that married couples would be allowed to have as many as three children.

one-child policy, official program initiated in the late 1970s and early ’80s by the central government of China, the purpose of which was to limit the great majority of family units in the country to one child each. The rationale for implementing the policy was to reduce the growth rate of China’s enormous population. It was announced in late 2015 that the program was to end in early 2016.

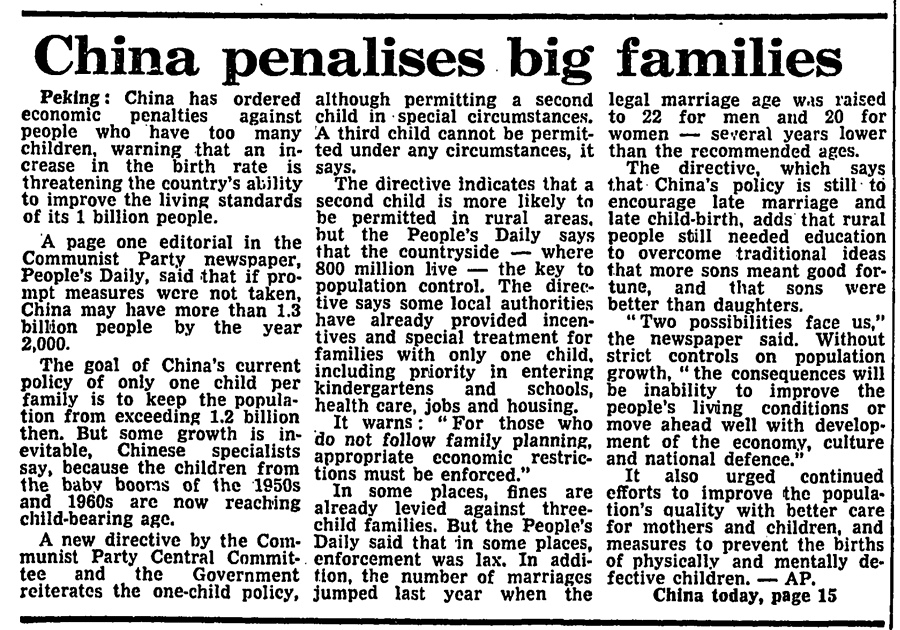

China began promoting the use of birth control and family planning with the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, though such efforts remained sporadic and voluntary until after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. By the late 1970s China’s population was rapidly approaching the one-billion mark, and the country’s new pragmatic leadership headed by Deng Xiaoping was beginning to give serious consideration to curbing what had become a rapid population growth rate. A voluntary program was announced in late 1978 that encouraged families to have no more than two children, one child being preferable. In 1979 demand grew for making the limit one child per family. However, that stricter requirement was then applied unevenly across the country among the provinces, and by 1980 the central government sought to standardize the one-child policy nationwide. On September 25, 1980, a public letter—published by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to the party membership—called upon all to adhere to the one-child policy, and that date has often been cited as the policy’s “official” start date.

A voluntary program was announced in late 1978 that encouraged families to have no more than two children, one child being preferable. In 1979 demand grew for making the limit one child per family. However, that stricter requirement was then applied unevenly across the country among the provinces, and by 1980 the central government sought to standardize the one-child policy nationwide. On September 25, 1980, a public letter—published by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to the party membership—called upon all to adhere to the one-child policy, and that date has often been cited as the policy’s “official” start date.

The program was intended to be applied universally, although exceptions were made—e.g., parents within some ethnic minority groups or those whose firstborn was handicapped were allowed to have more than one child. It was implemented more effectively in urban environments, where much of the population consisted of small nuclear families who were more willing to comply with the policy, than in rural areas, with their traditional agrarian extended families that resisted the one-child restriction. In addition, enforcement of the policy was somewhat uneven over time, generally being strongest in cities and more lenient in the countryside. Methods of enforcement included making various contraceptive methods widely available, offering financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities for those who complied, imposing sanctions (economic or otherwise) against those who violated the policy, and, at times (notably the early 1980s), invoking stronger measures such as forced abortions and sterilizations (the latter primarily of women).

In addition, enforcement of the policy was somewhat uneven over time, generally being strongest in cities and more lenient in the countryside. Methods of enforcement included making various contraceptive methods widely available, offering financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities for those who complied, imposing sanctions (economic or otherwise) against those who violated the policy, and, at times (notably the early 1980s), invoking stronger measures such as forced abortions and sterilizations (the latter primarily of women).

The result of the policy was a general reduction in China’s fertility and birth rates after 1980, with the fertility rate declining and dropping below two children per woman in the mid-1990s. Those gains were offset to some degree by a similar drop in the death rate and a rise in life expectancy, but China’s overall rate of natural increase declined.

What is the one-child policy. Let's explain in simple words - The secret of the company

The requirement to give birth to no more than one child per family lasted in China for more than 30 years. But it had a few concessions. The second child could be born by the villagers - provided that the first child was born a girl - and representatives of risky professions. If the older child was disabled or had developmental problems, the parents could give birth to another. Also, the restrictions did not apply to representatives of ethnic minorities and multiple pregnancies. nine0003

But it had a few concessions. The second child could be born by the villagers - provided that the first child was born a girl - and representatives of risky professions. If the older child was disabled or had developmental problems, the parents could give birth to another. Also, the restrictions did not apply to representatives of ethnic minorities and multiple pregnancies. nine0003

The one-child policy included a system of incentives and preferences for one-child families and their offspring, as well as the promotion of contraception and the denial of childbearing.

Penalties for breaking the policy varied by year, region, and nationality to which the family belonged. In some parts of the country, family planning officials were particularly brutal, forcing women to undergo abortions or sterilizations. Civil servants who violated the risk of a serious demotion or lose their jobs. nine0003

In addition, for the birth of children "in excess of the norm" families were obliged to pay "social fees" - large fines. If the fine for children was not paid, the child was not officially registered, so he could not generally access most social services, such as health care and education. Sometimes the authorities even took away "extra" children.

If the fine for children was not paid, the child was not officially registered, so he could not generally access most social services, such as health care and education. Sometimes the authorities even took away "extra" children.

Usage example

« The one-child policy has radically changed the composition of China's population. So now they have a population that is basically too old, too masculine and, in the long run, perhaps too small.” nine0016

(Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist May Fong talks about the consequences of China's population policy.)

History

Since the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, its authorities have encouraged large families. The leader of the country, Mao Zedong, believed that the future of the economy depended on the growth of the labor force. Contraceptives and abortion were banned.

In 1949, 120 million people lived in China, by 1953 583 million, and by the end of 1975 the population was close to a billion. nine0003

nine0003

After the Great Chinese Famine of 1959-1961, the government began to consider slowing down the population growth rate and launched the "Later Less Less" campaign. And when Deng Xiaoping came to power, the country began to carry out propaganda to reduce the number of children in the family.

- In 1978, a voluntary program appeared that offered to reduce the number of children in a family to two. A year later, the limit was reduced to one child, and in 1980 the program became mandatory.

- B 19In 1982, the requirement to plan a family was written into the Chinese Constitution.

- In 1995, the Chinese were forbidden to know the gender of their unborn child.

- In 2013, families with at least one parent as an only child were allowed to have two children.

- In 2015, the one-child policy was officially changed to the two-child policy.

- In 2021, families were allowed to have three children, and they also decided to stimulate the birth rate with cash payments.

Consequences

The one-child policy has indeed succeeded in curbing population growth—according to the PRC government estimates, it has helped to prevent the birth of about 400 million people. And the focus of parents on one child made it possible to give children a better education and more resources.

But the same policy has many disadvantages. The desire to have a son led to a large number of refusals of daughters and abortions if the screening showed the female sex of the fetus. And even to cases of female infanticide (infanticide). As a result, there are now too many men in China: for every 100 women, there are (depending on the area) from 106 to 130 men. nine0003

The population of the PRC is rapidly aging and the working population is declining. The authorities have already had to raise the retirement age. Many old people remain completely in the care of the state, since their only children have died.

In 2022, the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences predicts that China's population will decline for the first time since 1961.

The article was checked by:

How China abandoned the "one family - one child" rule

According to her, since the proclamation of the PRC in 19In 1949, the ruling party approved a population policy plan calling on the Chinese to have more children. In many aspects, it was similar to the demographic policy of the USSR.

Until the 1970s, the Chinese authorities encouraged the Chinese to have several children, and the following statement was written on the birth certificate of each child: "One is too little, two is not enough, and three is just right." However, by the end of the decade, the government thought about family planning and decided that the optimal number of children for an exemplary couple was two. And on June 19In 1979, an official order was issued "at the local level to apply practical measures to support married couples with one child."

By the end of 1981, the Chinese population reached a billion people, and soon the authorities of the Celestial Empire proclaimed that the goal of China's population policy would be "birth control and improving the quality of the population. "

"

In 1995, China's population policy encouraged couples to have fewer but healthier children. The Chinese government had a policy calling for couples to have only one child, but allowed couples to have two children under special conditions. nine0003

By 2000, in some regions of China, especially in economically developed cities, family planning policy became less rigid: for example, a couple could have two children if both mother and father were the only children in their families (and after 2013 - if at least one parent).

In October 2015, planned changes to the current one-child law were published, allowing all families without exception to have two children. The law came into force on January 1, 2016. nine0003

According to Ms. Song Xiaomei, over the years of reforms and population policy, China has managed to develop the health care system, reduce child mortality and raise the status of women in society. However, until today, a Chinese woman who has decided to give birth to a child is afraid of losing her job or losing her salary after leaving the decree. Many women in such a situation prefer a career to a family and refuse a second child. To remedy the situation, the Chinese authorities passed several laws at once. For example, "On population and family planning", according to which the newlyweds are given a month's leave, the same amount is given to the husband to care for his wife and newborn, and maternity leave was 128-156 days

Many women in such a situation prefer a career to a family and refuse a second child. To remedy the situation, the Chinese authorities passed several laws at once. For example, "On population and family planning", according to which the newlyweds are given a month's leave, the same amount is given to the husband to care for his wife and newborn, and maternity leave was 128-156 days

Another law, "Employment Promotion" requires local people's governments to create conditions for fair competition in the labor market and the elimination of discrimination against certain categories of workers, guaranteeing the equal right to work for men and women. Employers do not have the right to refuse to hire women on the basis of gender or set higher requirements for women when hiring. An exception is certain types of work or positions for which women cannot be accepted in accordance with labor protection rules for the weaker sex. nine0003

In addition, employers may not include conditions in an employment contract that restrict the right of female workers to marry and have children.

At the same time, if a woman cannot be at the workplace due to pregnancy, the employer must resolve this issue according to her application, but not demote. If necessary, you can change her workplace, but you can not harm the health of a pregnant woman and an unborn child.

At the same time, the problem of generational conflict has become especially acute in modern China, and in the case of the Celestial Empire, it is not so much about "fathers and children" as about "daughters-in-law and mother-in-law," said Liu Shizen, a professor at the China Youth University of Political Science. nine0003

According to her, harmony in the family largely depends on the relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law. Misunderstanding between them brings discomfort to other family members, has a negative impact on the development of children, and even leads to divorce. And the global transformation of society, including changes in the political, economic, cultural and moral spheres, only adds fuel to the fire.

According to statistics, 82 percent of Chinese families experience intergenerational conflicts due to different methods and views on raising children, and only two percent adhere to common views on this matter. When a child is not yet three years old, disagreements between mothers and grandmothers are not much different from ours: how to swaddle, how to put to bed, what to feed and how to treat. The real fundamental disputes begin later. nine0003

For example, for the older generation, material wealth and health are the highest goal. Grandmothers believe that young children do not need education. And young parents are sure that the child needs to develop abilities. Mom wants the child to play more on the street, and grandparents, as soon as they see at least some kind of danger, immediately forbid him to play, often carry him along the street in his arms and do not let him run so that he does not suddenly fall.

Now in China, many young couples have to give their children to be raised by grandparents.