How is child soldiers being stopped

Twenty Years of Stopping the Use of Child Soldiers • Stimson Center

February 12th is the International Day against the Use of Child Soldiers, known as Red Hand Day, which marks the anniversary of the 2002 entry into force of the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict – a landmark treaty banning the use of child soldiers. Over the past twenty years, 172 countries have ratified the Optional Protocol, and significant progress has been made to stop the use of child soldiers. Still, the work is far from over. Between 2005 and 2020, at least 93,000 children were recruited and used by parties to conflict, including over 8,500 children in 2020 alone.

Ending the use of child soldiers is an enduring challenge, and one that’s intrinsically linked to the global arms trade. Many of the state and non-state forces that recruit and use child soldiers rely on weapons and military assistance from some of the world’s leading arms exporters, including the United States. As a result, arms exporters and military assistance providers have significant leverage that can be used to encourage recipient states to stop using child soldiers by conditioning access to military hardware and training.

The United States has a unique piece of legislation designed to encourage governments to stop recruiting and using child soldiers. The Child Soldiers Prevention Act (CSPA) requires the Secretary of State to publish an annual list of countries whose armed forces, police or other security forces, or government-backed armed groups recruit or use child soldiers. Countries included on this list, known as the CSPA list, are prohibited from receiving certain types of U.S. military assistance, training, and defense equipment in the following fiscal year.

Unfortunately, the law has not lived up to its full potential. Stimson has analyzed implementation of the CSPA for more than a decade, through the CSPA Implementation Tracker. The Tracker is an online tool featuring interactive data visualizations capturing 12 years of arms sales and military assistance data, profiles of countries’ child soldiers practices, and information on the CSPA itself. As the only public source of consolidated information on the CSPA’s history, application, and impact, the Tracker can enhance public understanding of this critically important piece of legislation, assist in efforts to monitor and enhance its implementation, and ultimately contribute to strengthening U.S. efforts to end the use of child soldiers worldwide.

As the only public source of consolidated information on the CSPA’s history, application, and impact, the Tracker can enhance public understanding of this critically important piece of legislation, assist in efforts to monitor and enhance its implementation, and ultimately contribute to strengthening U.S. efforts to end the use of child soldiers worldwide.

Since the CSPA took effect in 2009, the State Department has identified 21 countries that recruit or use child soldiers or that support armed groups that do so. While the CSPA could have barred these countries from receiving certain types of U.S. arms sales and military assistance, Stimson’s research reveals that 97% of these prohibitions have been waived under a special “national interest” provision in the law allowing the President to exempt violators from sanction – permitting more than $6.7 billion in arms and assistance to flow to governments complicit in the recruitment and use of child soldiers.

The regular use of “national interest” waivers has continued under the Biden administration. During President Biden’s first year in office, the State Department identified 15 countries with security forces or government-backed groups that recruit or use child soldiers, which was the largest number of CSPA-listed countries in a single year. However, President Biden waived CSPA prohibitions for nine of these 15 countries. As a result, eight countries complicit in the recruitment or use of child soldiers are slated to receive a combined total of over $512 million in military assistance this fiscal year (not including arms sales, for which data is not yet publicly available). By contrast, just two countries were barred from receiving $1.65 million in combined military assistance.

During President Biden’s first year in office, the State Department identified 15 countries with security forces or government-backed groups that recruit or use child soldiers, which was the largest number of CSPA-listed countries in a single year. However, President Biden waived CSPA prohibitions for nine of these 15 countries. As a result, eight countries complicit in the recruitment or use of child soldiers are slated to receive a combined total of over $512 million in military assistance this fiscal year (not including arms sales, for which data is not yet publicly available). By contrast, just two countries were barred from receiving $1.65 million in combined military assistance.

The Biden administration should send a signal to governments included on the CSPA list that continued violations of international law will not be tolerated. The Biden administration should implement the CSPA to the fullest extent and use U.S. military assistance and arms sales to leverage much-needed change in the continued use of child soldiers.

What America Can Do to Stop the Practice of Child Soldiers • Stimson Center

In February, President Donald Trump identified human trafficking as a key issue of concern for U.S. domestic and foreign policies, and stated that his administration would make it a priority to stop the epidemic. Yet on September 30, President Trump waived nearly all sanctions that would prevent certain countries that use child soldiers from receiving U.S. military assistance and weapons. Such a move diminishes the impact that U.S. policy tools can have on combating a particularly heinous form of human trafficking—the recruitment and use of children in armed conflict.

In a major opportunity to use powerful leverage to encourage foreign governments to stop the horrific practice of recruiting and using child soldiers, the Trump administration again proved unwilling to take this commitment seriously. The Child Soldiers Prevention Act of 2008 (CSPA) aims to encourage foreign governments to stop recruiting and using children in armed conflict by leveraging traditionally coveted U. S. arms transfers and military assistance. Specifically, the law requires the secretary of state to identify countries that recruit and use child soldiers, and prohibits these countries from receiving seven categories of military assistance that fall under both Departments of State and Defense accounts, to include: direct commercial sales, excess defense articles, foreign military financing, foreign military sales, international military and education training assistance, peacekeeping operations assistance (PKO) and Section 1206 assistance.

S. arms transfers and military assistance. Specifically, the law requires the secretary of state to identify countries that recruit and use child soldiers, and prohibits these countries from receiving seven categories of military assistance that fall under both Departments of State and Defense accounts, to include: direct commercial sales, excess defense articles, foreign military financing, foreign military sales, international military and education training assistance, peacekeeping operations assistance (PKO) and Section 1206 assistance.

In 2017, the State Department identified eight countries that recruit and use children in their national militaries or government-supported armed groups: The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. The president, however, can choose to waive the CSPA’s prohibitions—in part or in full—and allow these identified countries to continue to receive U.S. weapons and military assistance. The 2017 list itself was controversial and marked the Trump administration’s first missed opportunity to seriously address the issue of child soldiers, as the list omits Afghanistan, Iraq and Myanmar—three countries with notorious and perpetual use of child soldiers.

The Trump administration’s second strike on child soldiers is evident in the issuing of the national security waivers. In a presidential memorandum, Trump waived CSPA prohibitions for five of the eight countries identified on the State Department’s child soldiers list. In so doing, Trump effectively gave a pass to governments that routinely exploit children in their national militaries or government-supported armed groups.

The administration waived all prohibited arms and assistance to Mali and Nigeria, authorizing at least $1.4 million in U.S. military assistance despite their records of child soldier recruitment and use. The administration also waived PKO assistance to the DRC and South Sudan. Somalia had PKO assistance, international military education and training assistance, as well as assistance that would have been prohibited under the CSPA but that is used for 10 U.S.C. § 333—foreign security forces: authority to build capacity waived. These waivers will allow the provision of $3 million in peacekeeping operations assistance for the DRC, more than $110 million in peacekeeping operations and military training for Somalia, and $25 million in peacekeeping operations for South Sudan. In a shift from previous years, the Trump administration did not waive international military and education training assistance for the DRC, thereby blocking $375,000 in assistance requested for FY18.

In a shift from previous years, the Trump administration did not waive international military and education training assistance for the DRC, thereby blocking $375,000 in assistance requested for FY18.

Although Sudan, Syria and Yemen did not receive waivers, they are currently not slated to receive any sanctionable assistance from the United States in FY18.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration’s failure to take a stand against the abusers of children is not unique. During the Obama administration, the United States routinely waived the CSPA’s prohibitions and authorized more than $315 million in arms sales and more than $1.2 billion in military assistance to countries with known human rights abuses against children in armed conflict. The Obama administration withheld approximately $8 million in arms sales and $56 million in military assistance—amounting to roughly 2.6 percent of the total amount of arms sales and less than 5 percent of the amount of military assistance that would otherwise have been prohibited by the CSPA. With this year’s waivers, the Trump administration has continued a familiar pattern, authorizing nearly $140 million in military assistance, or ninety-nine percent of U.S. military assistance that would have otherwise been prohibited by the CSPA.

With this year’s waivers, the Trump administration has continued a familiar pattern, authorizing nearly $140 million in military assistance, or ninety-nine percent of U.S. military assistance that would have otherwise been prohibited by the CSPA.

The Trump administration appears poised to carry on the Obama administration’s unfortunate legacy as it pertains to preventing the recruitment and use of child soldiers. In this way, the Trump administration risks abandoning its promise to get tough on the human trafficking issues. Many of the countries on the CSPA list are repeat offenders, and the continued provision of waivers—particularly full waivers—undermines the CSPA’s intended purpose. Until the Trump administration uses the waivers as intended, when there is a legitimate national security issue at stake, governments on the CSPA list will continue to receive the wrong message—namely that they can exploit vulnerable children with impunity.

This article originally appeared in The National Interest on November 6, 2017.

No to the use of child soldiers, no to genocide

Lieutenant General Roméo Dallaire, 1994 ©LGenDallaire

About the Author

Romeo Dallaire and Shelley Whitman

Lieutenant General Romeo Dallaire is the founder of the Child Soldiers Protection Initiative and is a former Force Commander of the UN Relief Mission in Rwanda. Shelley Whitman is Executive Director of the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldier Initiative.

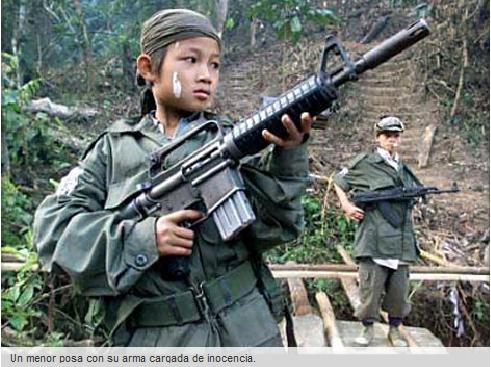

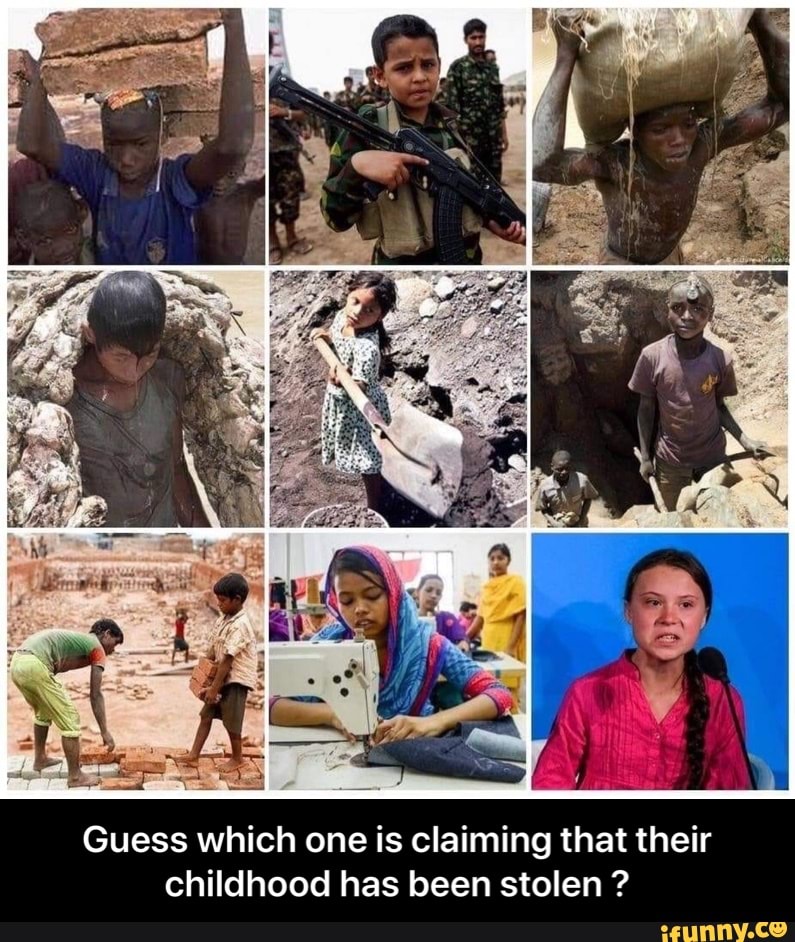

We live in an age where the level of human suffering as a result of interstate conflicts seems to be increasing exponentially. Building the political momentum for a timely, indiscriminate response to human suffering remains a critical challenge (MacFarlane and Weiss, 2000). At the heart of the problem of human suffering is the plight of vulnerable categories of the population, especially children. Of all the threats that characterize contemporary conflicts, one of the most far-reaching and one of the most disturbing trends of our time is the use of children as soldiers. If in the past children were forced to fight despite their young age, now they are forced to fight precisely because of their young age.

If in the past children were forced to fight despite their young age, now they are forced to fight precisely because of their young age.

New approaches to conflict prevention must include an assessment of the importance we place on child protection. As Graça Machel stated, "Our joint efforts cannot ensure the protection of children. This must be changed, we must provide opportunities to confront the problems that cause them to suffer" (2001, p. XI). Perhaps our failure to prevent and respond appropriately to conflict is directly related to our failure to protect children and prevent them from being deliberately used in armed conflict.

Early warning

The Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine, adopted in 2005, is designed to help prevent conflict. Based on the idea of early recognition of red flags, R2P aims to get the global community to take proactive action to prevent mass atrocities. The United Nations envisions building “'early warning capabilities' to inform in a timely and decisive manner” (Guéhenno, Ramcharan and Mortimer, 2010). If we know and understand information about the preparation of massive atrocities at an early stage, we can use this crucial opportunity to prepare a more effective response.

If we know and understand information about the preparation of massive atrocities at an early stage, we can use this crucial opportunity to prepare a more effective response.

"There does not appear to be a full understanding within the United Nations system that the nature and urgency of situations leading to genocide require a unique analysis and approach that justifies the granting of special powers clearly in line with this goal" (quoted in Akhavan , 2011, p. 21). The R2P Doctrine explicitly aims to prevent mass atrocities and genocide, in line with the "narrow but deeply thought out" approach referred to by United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon:

Our R2P concept is thus narrow but deeply thought out. Its scope is narrow, and it aims to prevent four crimes and violations that were agreed upon by world leaders in 2005. Extending this principle to other scourges, such as HIV-AIDS… would undermine the consensus reached in 2005 and change the idea beyond recognition, undermining its usefulness in practice. At the same time, our response must be thoughtful, using the full arsenal of crime prevention and human protection tools available within the United Nations system, its partners at the regional and subregional levels and civil society organizations, and, not least from Member States themselves (2008).

At the same time, our response must be thoughtful, using the full arsenal of crime prevention and human protection tools available within the United Nations system, its partners at the regional and subregional levels and civil society organizations, and, not least from Member States themselves (2008).

There needs to be a comprehensive set of early warning indicators that the global community can use to inform real action. The recruitment of children into the armed forces and the use of child soldiers are within the scope of the responsibility to protect but are not yet used as an early warning sign. It has the potential to galvanize global support while responding to Ban Ki-moon's call for a "narrow yet thoughtful approach."

In April 2012, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon established the United Nations Internal Review Panel in Sri Lanka. The Panel's report concluded that there was a "systemic failure" in United Nations action. It was also noted that some of the mistakes noted were similar to those made in Rwanda. In accordance with the recommendations of the Group, under the leadership of United Nations Under-Secretary-General Jan Eliasson, work was organized to develop a plan to implement these recommendations, which is known as the Action Plan for the implementation of the "Human Rights First" initiative. Now we need to translate it into concrete actions. The "Human Rights First" initiative aims to prevent large-scale violations of human rights.

In accordance with the recommendations of the Group, under the leadership of United Nations Under-Secretary-General Jan Eliasson, work was organized to develop a plan to implement these recommendations, which is known as the Action Plan for the implementation of the "Human Rights First" initiative. Now we need to translate it into concrete actions. The "Human Rights First" initiative aims to prevent large-scale violations of human rights.

With the adoption of resolution 2171 (2014), the United Nations Security Council declared its intention to more effectively engage the mechanisms of the United Nations system to ensure that early warning of impending bloodshed entails early and concrete preventive action (United Nations, year 2014). An example of such measures is the prioritization of child protection in peace and security programs, which can be a warning of a possible genocide.

Priority security issue?

The ineffectiveness of the current measures to prevent the use of child soldiers is due to the fact that insufficient attention is paid to the protection of children and the prevention of the recruitment of minors into the armed forces and their use in armed conflicts, and in fact such measures are provided for by international peace treaties: " Since the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989, 180 peace agreements have been concluded between various warring parties. Only ten of these agreements contained provisions specifically addressing the issue of child soldiers” (Whitman, Zayed and Conradi, 2014). Attention to avoiding the use of child soldiers is of paramount importance compared to the protection of all children, as the use of child soldiers is one of the elements of early recognition of red flags.

Only ten of these agreements contained provisions specifically addressing the issue of child soldiers” (Whitman, Zayed and Conradi, 2014). Attention to avoiding the use of child soldiers is of paramount importance compared to the protection of all children, as the use of child soldiers is one of the elements of early recognition of red flags.

The world community generally reacts to the use of children as soldiers after it becomes known, and it is necessary to focus on preventive measures. By focusing on issues of disarmament, demobilization, social rehabilitation and reintegration of members of armed groups rather than eradicating the use of child soldiers, the international community has tried and is trying to fix what is broken, not to protect what is whole. Until this issue is given more attention on the security agenda, the international community will continue to miss great opportunities to end child recruitment into armed groups (Whitman, Zayed and Conradi, 2014).

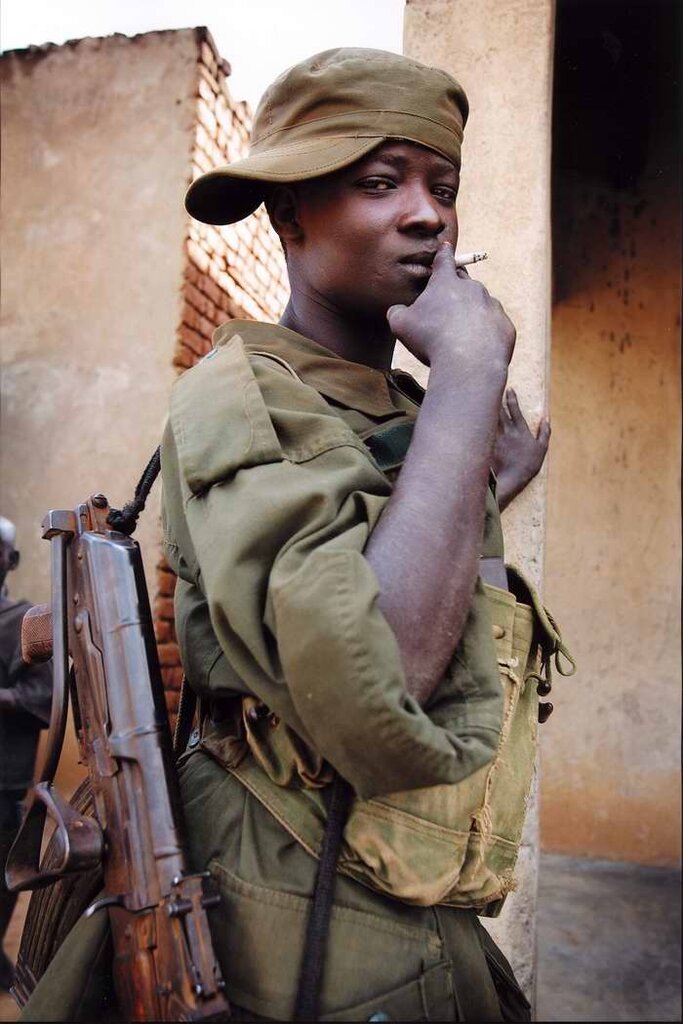

Rwanda, 1994

In 1994, I commanded the forces of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR). I already had to write extensively about the genocide during this period, but I did not analyze in detail the relationship between the use of child soldiers in armed groups and Rwanda's gradual slide towards genocide. I did not understand, along with the rest of the international community, that the use of child soldiers was a sign of imminent mass atrocities and genocide, but later I began to consider this phenomenon in the context of my work on the implementation of the Romeo Dallaire initiative to protect child soldiers.

I already had to write extensively about the genocide during this period, but I did not analyze in detail the relationship between the use of child soldiers in armed groups and Rwanda's gradual slide towards genocide. I did not understand, along with the rest of the international community, that the use of child soldiers was a sign of imminent mass atrocities and genocide, but later I began to consider this phenomenon in the context of my work on the implementation of the Romeo Dallaire initiative to protect child soldiers.

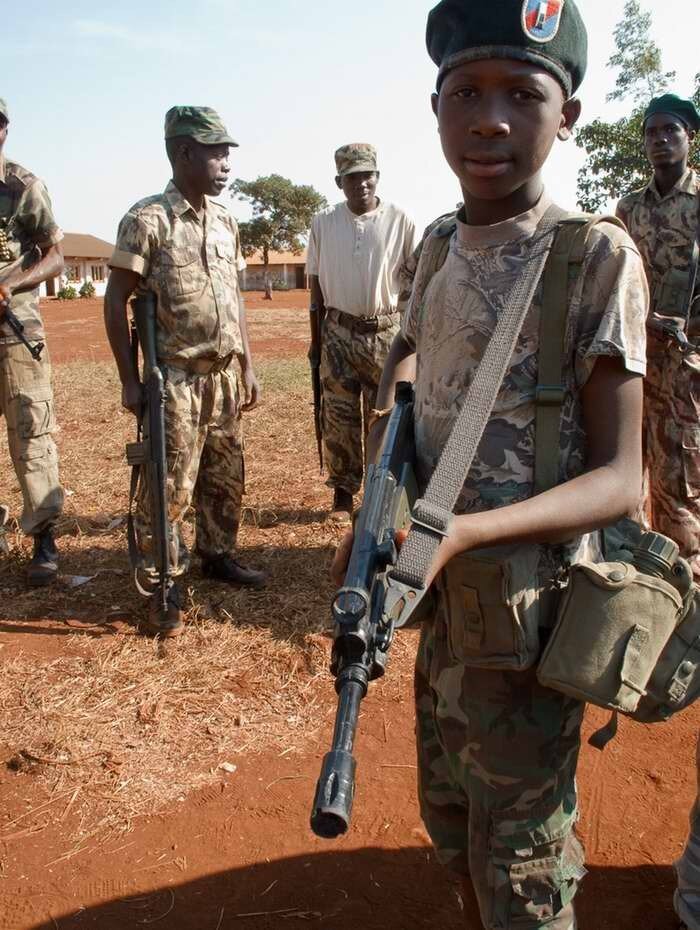

On August 4, 1993, the Arusha Peace Agreement was signed. My main task was to collect information and send reports on compliance with the peace agreement. I remember what struck me the most during my first visit to representatives of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) - they had very young soldiers. In 1990, the RPF had only 3,000 fighters, but by 1993 their army had grown to 22,000. This was largely due to a shortage of personnel and a limited population to recruit fighters into the RPF. Child soldiers observed discipline, they were well fed, they were treated normally. We did not send separate reports on the use of child soldiers, although we noted in the technical report for 1993 that the soldiers were "very young". In addition, we were not aware of this problem and prepared for it.

Child soldiers observed discipline, they were well fed, they were treated normally. We did not send separate reports on the use of child soldiers, although we noted in the technical report for 1993 that the soldiers were "very young". In addition, we were not aware of this problem and prepared for it.

Between October 1990 and August 1993, the strength of Rwandan Armed Forces (RAF) grew from 5,000 to 28,000. At that time, migrant workers and the unemployed were easily recruited into the RVS. By November 1993, columns of men began to march in the streets, they were not in military uniform, all in baggy pants and shirts in the colors of the flag of the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (NRDDR). They were members of "Interahamwe" , a youth organization of the extremist party NRDDR . It would seem that they had to be under 18 years old, as members of any youth political movement. But many were clearly older. Later we realized that these senior comrades were "leaders".

In December 1993, I received a letter signed by members of the RVS. They warned that youth movements were dangerous. In January 1994, as street demonstrations grew, we began to notice that Interahamwe attracts more and more minors. Our informant, whose name was Jean-Pierre, informed us that he was assigned to train members of Interahamwe to kill people. You could see, he said, how minors were recruited and trained to kill Tutsis. He turned to UNAMIR for assistance in organizing the seizure of weapons caches so that these weapons would not fall into the hands of the militants. Otherwise, he explained, it would be impossible to stop the massacres.

Activists Interahamwe , those who gave orders, were given firearms, and minors were given machetes. Collecting machetes from minors is much easier than securing the surrender of firearms. For minors, machetes are common agricultural equipment. We visited several training bases. There were many minors at all the bases, all in civilian clothes.

In addition, in January 1994, a UNAMIR military observer reported that he had seen teachers instruct children to go home and ask their parents what ethnicity they belonged to. Teachers expressed concern about this new instruction, as it indicated preparations for genocide. Children under the age of 14 do not have identity cards, so this new directive allowed anyone to know which students were Tutsi. This should have been a very alarming signal, but at that time no one attached any importance to this.

By mid-April 1994, when the crimes of genocide became widespread, the Interahamwe movement actively used minors, they were assigned to kill people and set up ambushes on the roads. The use of minors was an integral part of the tactical and strategic plans of the extremists. If this critical wake-up call were heeded, assistance and resources could be organized to protect minors, which would eliminate or seriously reduce the ability of extremists to commit the crime of genocide.

Conclusion

Understanding that the use of child soldiers is a sign of preparation for massive atrocities provides greater opportunities to address problems through structural measures. In weak and unstable states, children are more easily lured into criminal activity. This happens due to the same factors as the recruitment of child soldiers: there are many minors, they have nothing else to do, they are in a desperate financial situation, they do not have a full education or did not study at all, there are no hopes for a well-paid job, they constantly live in a climate of violence and degradation that is typical of failed states.

Numerous examples of the participation of minors in mass atrocities and genocide are known - from the activities of the Hitler Youth during the Second World War to executions on the killing fields in Cambodia and the genocide in Rwanda. The phenomenon is not new, but so far the understanding of the link between the use of child soldiers and opportunities to create more effective early warning mechanisms has not led to practical measures. This approach can lead to actions to strengthen child protection mechanisms, from training and education to community outreach, reform of safety structures and the revitalization of the best investment projects for disadvantaged communities. Expanding the system of early warning mechanisms aimed at identifying the facts of the use of child soldiers, giving them priority, preventing these facts - all this, perhaps, will be the practical step that has not yet been taken by the world community, but which can lead to long-term systemic changes. .

This approach can lead to actions to strengthen child protection mechanisms, from training and education to community outreach, reform of safety structures and the revitalization of the best investment projects for disadvantaged communities. Expanding the system of early warning mechanisms aimed at identifying the facts of the use of child soldiers, giving them priority, preventing these facts - all this, perhaps, will be the practical step that has not yet been taken by the world community, but which can lead to long-term systemic changes. .

Notes

Akhavan, Payam (2011). Preventing genocide: measuring success by what does not happen. Criminal Law Forum , vol. 22, Nos. 1 and 2 (March), pp. 1-33.

Ban, Ki-moon (2008). Address at event on "Responsible Sovereignty: International Cooperation for a Changed World". Berlin, July 15. The publication is available on the website

http://www.un.org/sg/selected-speeches/statement_full.asp?statID=1631.

Guéhenno, Jean-Marie, Bertram G. Ramcharan, and Edward Mortimer (2010). UN Early Warning and Responses to Mass Atrocities. Meeting Summary. 23 Mar. Global Center for the Responsibility to Protect. The publication can be found on the website

http://www.globalr2p.org/media/files/un-early-warning-and-responses-to-mass-atrocities.pdf.

MacFarlane, Stephen Neil, and Thomas G. Weiss (2000). Political Interest and Humanitarian Action. Security Studies , Vol. 10, No.1 (Fall), pp. 112-142. The publication can be consulted at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09636410008429422#.Vfrq3d9VhBd.

Machel, Graça (2001). The Impact of War on Children . New York: Palgrave.

United Nations (2014). Security Council, adopting resolution 2171 (2014), Pledges Better Use of System-Wide approach to Conflict prevention. The publication is available at http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11528.doc.htm

Whitman, Shelly, Tanya Zayed, and Carl Conradi (2014). Child Soldiers: A Handbook for Security Sector Actors . 2nd ed., Halifax: the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative.

Child Soldiers: A Handbook for Security Sector Actors . 2nd ed., Halifax: the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative.

Stéphane Jean

Supporting national justice and security institutions: the role of United Nations peacekeeping operations

While less than 10 per cent of the United Nations police, justice and corrections officers represent the total number of personnel involved in peacekeeping operations, their work remains fundamental to the achievement of sustainable peace and security, as well as for the successful fulfillment of the mandates of such missions.

Shamila Nair-Beduel

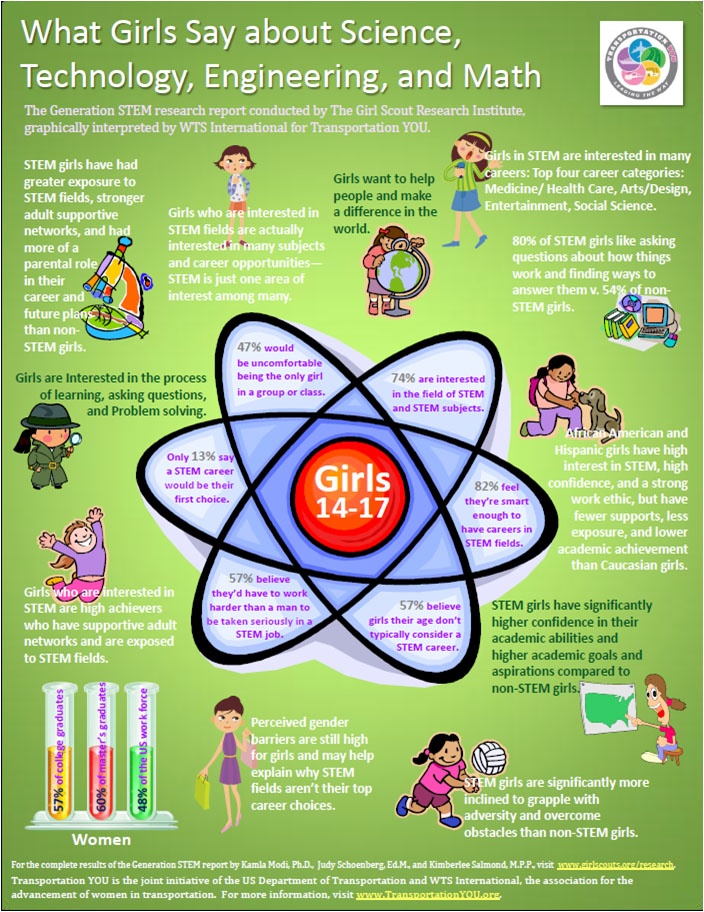

Lack of gender equality in science is a common problem

How are we going to deal with the complex challenges of today, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, water scarcity, virus outbreaks and the rapid development of artificial intelligence, if we cannot use all of our best minds, wherever they are?

Qu Dongyu

Pulses in the spotlight: the roots of sustainable agriculture and food security

Pulses have a high genetic diversity, which provides the opportunity to obtain the necessary traits to adapt to future climate scenarios by breeding varieties that are resistant to climate change . Science, technology and innovation are critical to meeting this pressing need.

Science, technology and innovation are critical to meeting this pressing need.

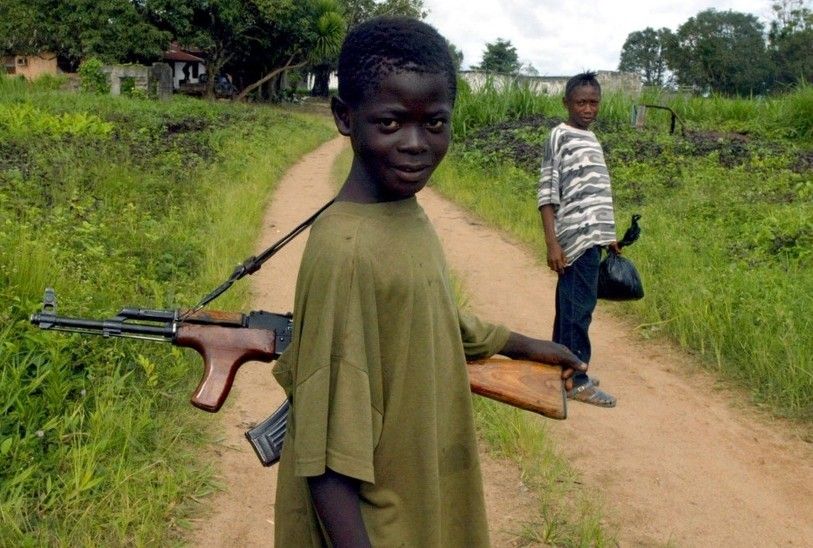

Five thousand child soldiers were demobilized last year

Children are still the main victims of modern armed conflicts. Tens of thousands of them are involved in combat operations. They are killed by bullets and anti-personnel mines. Child soldiers are often turned into suicide bombers. This is stated in the new UN report.

“In today's civil conflicts, children are recruited to take part in hostilities. Many non-state armed groups recruit large numbers of minors. Children and adolescents are increasingly being coerced into acts of violence, including being forced to commit acts of terrorism and participate in executions,” the new report says. In Syria, Iraq, Mali and Nigeria, a huge number of children serve in the ranks of non-state armed groups. This, according to the authors of the report, is a whole army of the “lost generation”. Today, many simply underestimate the scale of this tragedy.

This, according to the authors of the report, is a whole army of the “lost generation”. Today, many simply underestimate the scale of this tragedy.

On February 12, UNICEF initiated the International Day Against the Use of Child Soldiers. The international community has repeatedly declared its readiness to end the recruitment of minors into the ranks of armed groups. Last year, five thousand children were released from the armed forces and non-governmental armed groups. Many of the demobilized teenagers participated in reintegration programs into civilian life. But tens of thousands of young men and women are still in the ranks of the belligerents.

In addition, demobilized children face enormous difficulties in civilian life. In some post-conflict states, child soldiers are handed over to military tribunals without providing them with either psychological or legal assistance.

UN Photo

Child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

On February 12, UNICEF celebrates the International Day Against the Use of Child Soldiers. The international community has repeatedly declared its readiness to end the recruitment of minors into the ranks of armed groups. Last year, five thousand children were released from the armed forces and non-governmental armed groups. Many of the demobilized teenagers participated in reintegration programs into civilian life. But tens of thousands of young men and women are still in the ranks of the belligerents.

The international community has repeatedly declared its readiness to end the recruitment of minors into the ranks of armed groups. Last year, five thousand children were released from the armed forces and non-governmental armed groups. Many of the demobilized teenagers participated in reintegration programs into civilian life. But tens of thousands of young men and women are still in the ranks of the belligerents.

In addition, demobilized children face enormous difficulties in civilian life. In some post-conflict states, child soldiers are handed over to military tribunals without providing them with either psychological or legal assistance.

“The process of demobilizing children from armed groups and armed forces must be accompanied by a comprehensive reintegration process that includes medical care and psychosocial support, as well as educational programs. If this process does not receive strong political and financial support, then, unfortunately, in many conflict situations, adolescents can be re-recruited,” said Virginia Gamba, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict.

There has been some success in combating the recruitment of child soldiers, said Virginia Gamba, but she said boys and girls continue to be recruited and abducted, forced to fight or serve as militants and soldiers.

These children face horrendous abuse that is likely to have severe physical and psychological consequences for them throughout their lives. We must show these children that they have a future outside of conflict zones

“These children are facing horrendous abuse that is likely to have severe physical and psychological consequences throughout their lives. We have an obligation to show these children that they have a future outside of conflict zones, that they can live in peace and security and fulfill their dreams,” said Virginia Gamba.

According to the United Nations, 20 conflict-affected countries reported cases of children participating in hostilities last year. The UN Secretary-General's 2016 annual report contains a "black list" of parties to conflicts that recruit child soldiers.