How does child labor affect us today

Child labour | UNICEF

Programme

Nearly 1 in 10 children are subjected to child labour worldwide, with some forced into hazardous work through trafficking.

UNICEF/UN0263808/Lister

Economic hardship exacts a toll on millions of families worldwide – and in some places, it comes at the price of a child’s safety. Roughly 160 million children were subjected to child labour at the beginning of 2020, with 9 million additional children at risk due to the impact of COVID-19.

This accounts for nearly 1 in 10 children worldwide. Almost half of them are in hazardous work that directly endangers their health and moral development.

Children may be driven into work for various reasons. Most often, child labour occurs when families face financial challenges or uncertainty – whether due to poverty, sudden illness of a caregiver, or job loss of a primary wage earner.

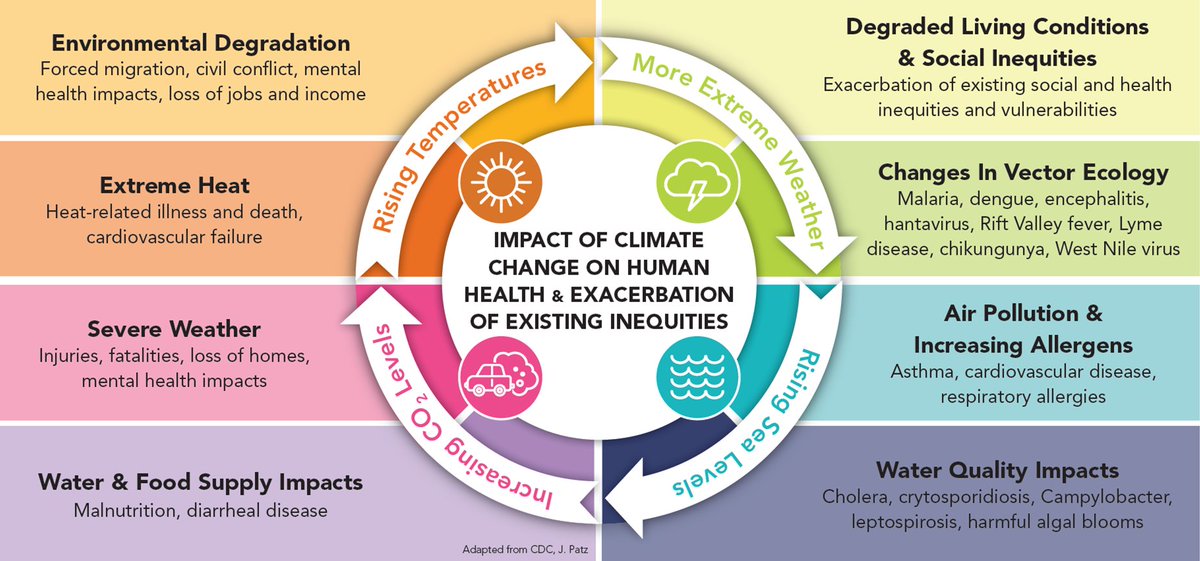

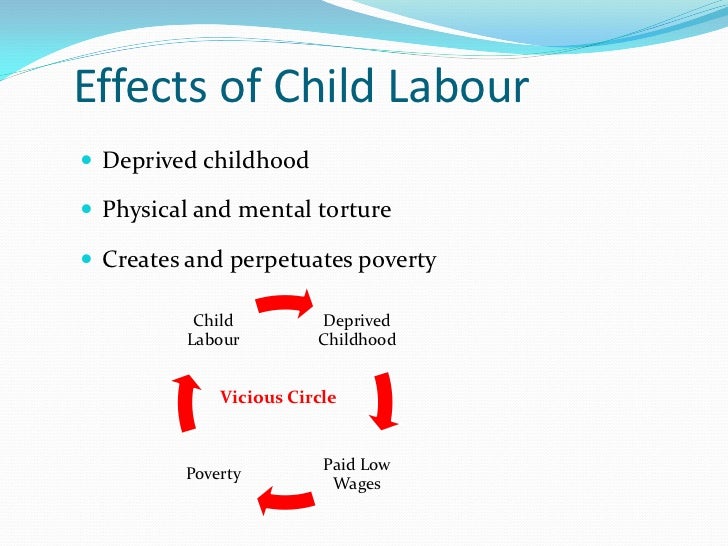

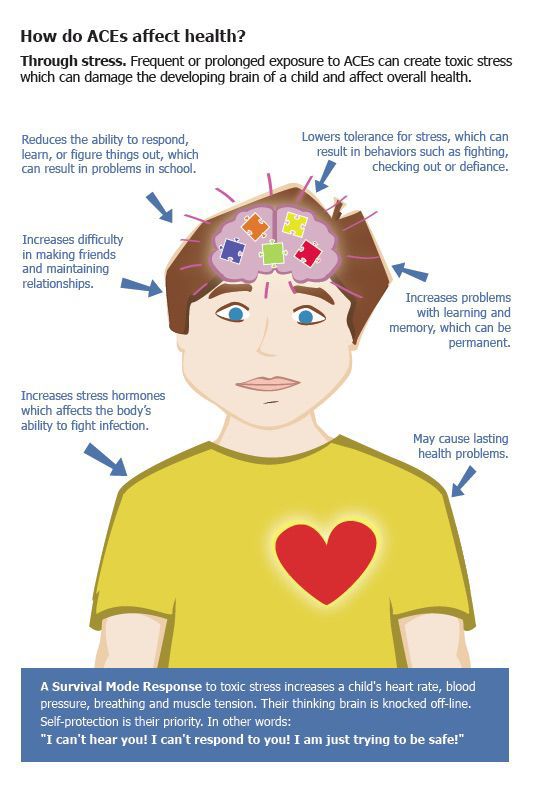

The consequences are staggering. Child labour can result in extreme bodily and mental harm, and even death. It can lead to slavery and sexual or economic exploitation. And in nearly every case, it cuts children off from schooling and health care, restricting their fundamental rights and threatening their futures.

Migrant and refugee children – many of whom have been uprooted by conflict, disaster or poverty – also risk being forced into work and even trafficked, especially if they are migrating alone or taking irregular routes with their families.

Trafficked children are often subjected to violence, abuse and other human rights violations. And some may be forced to break the law. For girls, the threat of sexual exploitation looms large, while boys may be exploited by armed forces or groups.

Children on the move risk being forced into work or even trafficked – subjected to violence, abuse and other human rights violations.

Whatever the cause, child labour compounds social inequality and discrimination, and robs girls and boys of their childhood. Unlike activities that help children develop, such as contributing to light housework or taking on a job during school holidays, child labour limits access to education and harms a child’s physical, mental and social growth. Especially for girls, the “triple burden” of school, work and household chores heightens their risk of falling behind, making them even more vulnerable to poverty and exclusion.

Unlike activities that help children develop, such as contributing to light housework or taking on a job during school holidays, child labour limits access to education and harms a child’s physical, mental and social growth. Especially for girls, the “triple burden” of school, work and household chores heightens their risk of falling behind, making them even more vulnerable to poverty and exclusion.

Key facts

- The number of children in child labour has risen to 160 million worldwide – an increase of 8.4 million children in the last four years – with 9 million additional children at risk due to the impact of COVID-19.

- Progress to end child labour has stalled for the first time in 20 years, reversing the previous downward trend that saw child labour fall by 94 million between 2000 and 2016.

- The incidence of hazardous work in countries affected by armed conflict is 50% higher than the global average.

- 30 million children live outside their country of birth, increasing their risk of being trafficked for sexual exploitation and other work.

UNICEF’s response

UNICEF/UNI281125/Herwig Children largely from the ethnic Dom community learn in a UNICEF-supported centre in Jordan, in 2019. With many of their families living in poverty, these children become especially vulnerable to negative coping mechanisms, like working on the street. Centres play a key role in identifying children who face challenges and helping them to enroll in formal and non-formal education.

UNICEF works to prevent and respond to child labour, especially by strengthening the social service workforce. Social service workers play a key role in recognizing, preventing and managing risks that can lead to child labour. Our efforts develop and support the workforce to identify and respond to potential situations of child labour through case management and social protection services, including early identification, registration and interim rehabilitation and referral services.

We also focus on strengthening parenting and community education initiatives to address harmful social norms that perpetuate child labour, while partnering with national and local governments to prevent violence, exploitation and abuse.

With the International Labour Organization (ILO), we help to collect data that make child labour visible to decision makers. These efforts complement our work to strengthen birth registration systems, ensuring that all children possess birth certificates that prove they are under the legal age to work.

Children removed from labour must also be safely returned to school or training. UNICEF supports increased access to quality education and provides comprehensive social services to keep children protected and with their families.

To address child trafficking, we work with United Nations partners and the European Union on initiatives that reach 13 countries across Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America.

More from UNICEF

COVID-19 and child labour

A time of crisis, a time to act

See the full report

A second chance: out of juvenile detention and in school

How virtual courts can create a more child-friendly justice system

Read the story

Mobile teams provide support to traumatized families

Child protection specialists in Ukraine such as Olga are helping fleeing mothers and their children cope with trauma and an uncertain future

See the story

Trying to make sense of a senseless war

UNICEF is supporting families devastated by war in Ukraine. Spokesperson James Elder reflects on what he has seen so far

Spokesperson James Elder reflects on what he has seen so far

Read the story

Resources

Health Issues | The University of Iowa Labor Center

Physical Differences between Children and Adults May Increase Children’s Work-related Risks

Working conditions that are safe and healthy for adults may not be safe and healthy for children because of their physical differences. Risks may be greater for children at various stages of development and may have long-term effects. Factors that may increase the health, safety, and developmental risk factors for children include:

Match Factory Worker

India, 1993

Photo: David Parker

- Rapid skeletal growth

- Development of organs and tissues

- Greater risk of hearing loss

- Developing ability to assess risks

- Greater need for food and rest

- Higher chemical absorption rates

- Smaller size

- Lower heat tolerance

Injuries among Young Workers

One quarter of economically active children suffer injuries or illnesses while working, according to an International Labor Organization survey of 26 countries.

Each year, as many as 2.7 million healthy years of life are lost due to child labor, especially in agriculture.

Many of the industries that employ large numbers of young workers in the United States have higher-than-average injury rates for workers of all ages, such as grocery stores, hospitals, nursing homes, and agriculture.

Why do young workers have more accidents than adults?

Metal Worker

India, 1995

Photo: David Parker

- “Unskilled” and labor-intensive jobs may be risky.

- Training and supervision may be inadequate.

- Work may be illegal and inappropriate.

- Lesser experience at work can increase the risk of accidents.

Poverty: An Additional Risk Factor

- Low-income youth are more likely to work in high-risk occupations such as agriculture, mining, and construction.

- Poverty-related health problems (e.g., malnutrition, fatigue, anemia) increase the risks and consequences of work-related hazards and may lead to permanent disabilities and premature death.

Psychosocial Effects of Child Labor

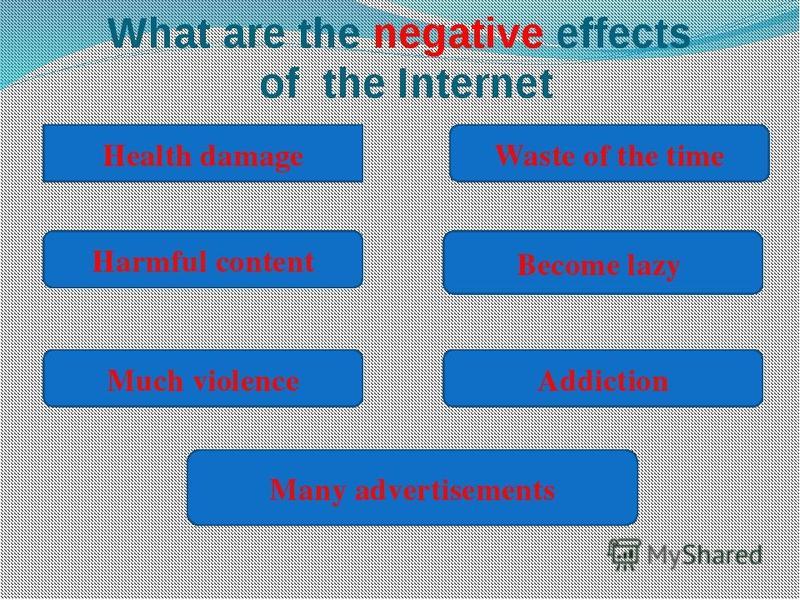

- Long hours of work on a regular basis can harm children’s social and educational development.

- U.S. adolescents who work more than 20 hours per week have reported more problem behaviors (e.g., aggression, misconduct, substance use), and sleep deprivation and related problems (falling asleep in school). They are more likely to drop out of school and complete fewer months of higher education.

- The unconditional worst forms of child labor (e.g., slavery, soldiering, prostitution, drug trafficking) may have traumatic effects, including longer term health and socioeconomic effects.

Hazards of Agricultural Child Labor

Photo: David Parker

Studies in many countries have shown that children working in agriculture suffer particularly high rates of injury. In the Philippines, for example, a survey found that children in agriculture had five times greater risk of injury compared with children working in other industries. (Castro 2010)

(Castro 2010)

Several conditions cause the relatively high rates of injuries, health problems, and fatalities among agricultural child laborers:

- Exposure to pesticides

- Working with machinery and sharp tools

- Lack of clean water, hand-washing facilities, and toilets

- Beginning to work at very early ages, often between 5-7 years of age

- Less restrictive standards for agricultural work

Educational materials containing information on Health Issues regarding Child Labor, including Adult Education—Core Workshop on Child Labor and K-12 Teachers’ Materials, are available through this web site. These materials include Power Point presentations, instructors’ manuals, activities, and handouts. You may adapt these materials to your group’s needs.

World Day Against Child Labor - Background

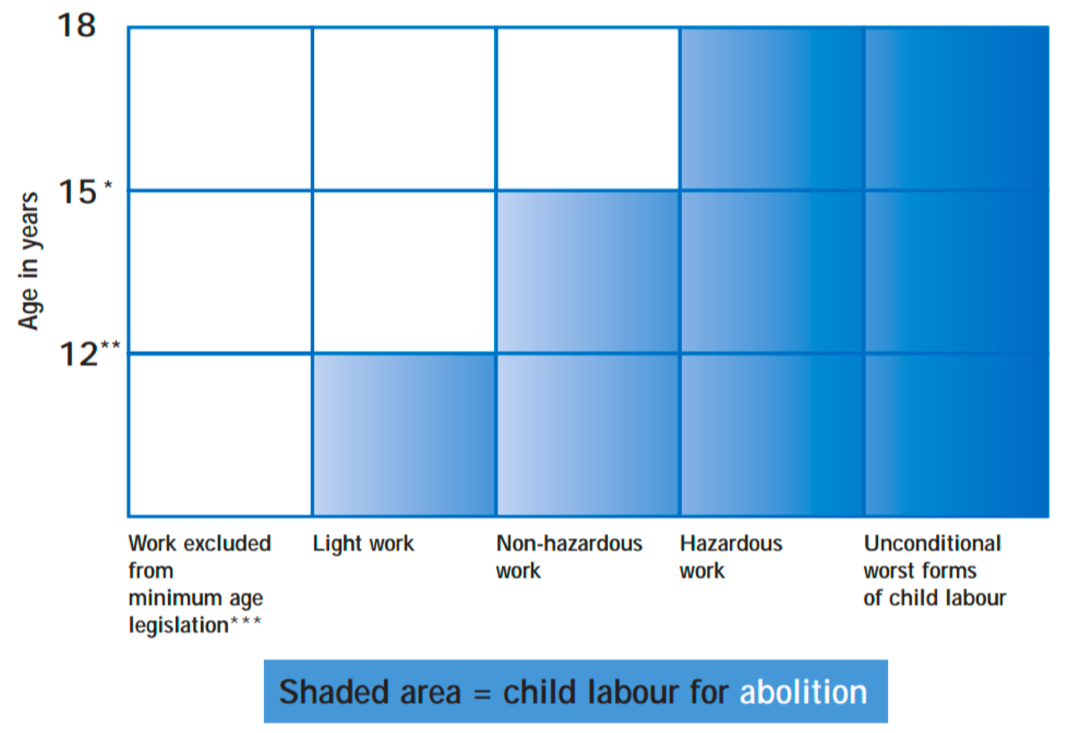

All children have the right to be protected from working in hazardous conditions that could harm their health and education. Figure ILO

Figure ILO

The International Labor Organization (ILO) first celebrated World Day against Child Labor in 2002.

Its purpose is to draw attention to this problem and the need for measures to eliminate it. Every year on June 12, governments, employers' and workers' organizations, civil society representatives, and millions of people around the world join forces to fight child labour.

In 2015, 17 Sustainable Development Goals were adopted and Goal 8 calls for an end to forced labor and all forms of child labor by 2030. We must work together to achieve this goal.

Child labor

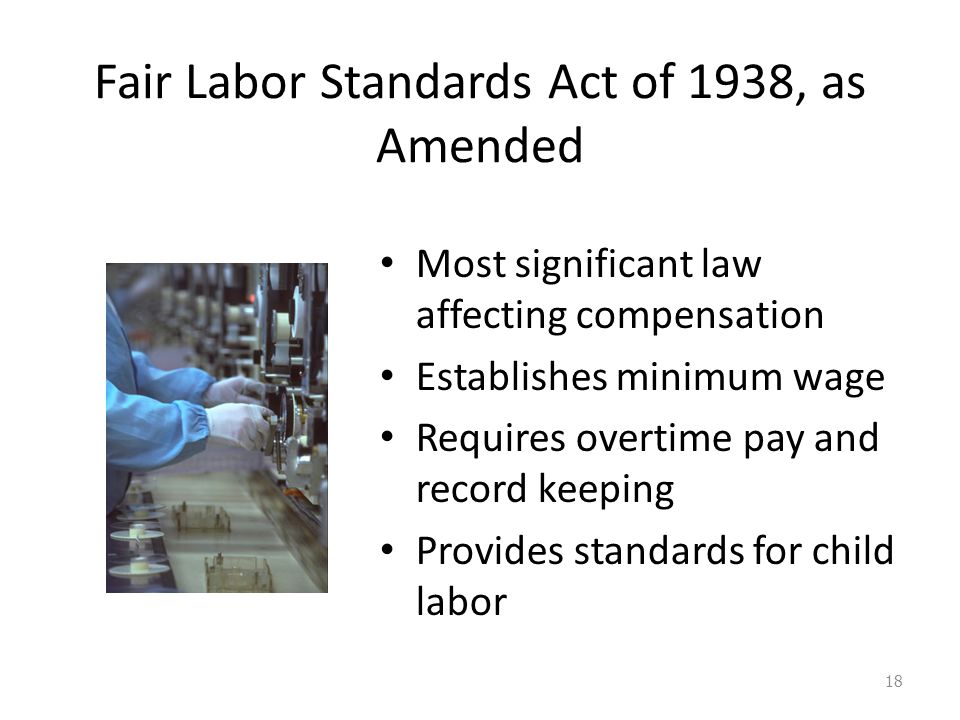

One of the main objectives of the International Labor Organization when it was founded in 1919 was the abolition of child labor. Historically, the main instrument by which the ILO has sought to achieve the goal of abolishing child labor has been the adoption and enforcement of labor standards embodying the concept of a minimum age for employment or work. In addition, since 1919, the ILO has traditionally assumed in its standard-setting activities that minimum age standards should be linked to schooling. Approved at 1973, the Minimum Age Convention (Convention No. 138) embodies this tradition by providing that the minimum age for entry into employment should not be lower than the minimum age for completion of compulsory schooling.

Approved at 1973, the Minimum Age Convention (Convention No. 138) embodies this tradition by providing that the minimum age for entry into employment should not be lower than the minimum age for completion of compulsory schooling.

The adoption by the ILO in 1999 of Convention No. 182 consolidated the global consensus on the abolition of child labour. Convention No. 182 provided the necessary focus without overriding the overall goal set out in Convention No. 138 of the effective abolition of child labour. Moreover, the concept of worst forms allows for prioritization and can be used as a first step towards addressing the underlying problem of child labour. This concept also helps focus attention on the impact of work on children, as well as the work they do.

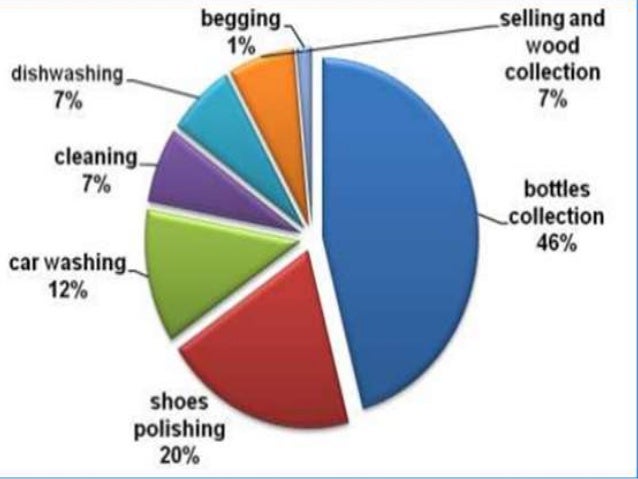

Child labor, which is condemned by the international community, can be divided into three categories:

Not every activity performed by children should be classified as a type of child labor that should be eliminated. The participation of children or adolescents in work that does not affect their health and development or interfere with their schooling is generally seen as something positive. This includes activities such as helping parents around the house, helping out with the family business, or earning pocket money outside school hours and during school holidays. Such activities contribute to the development of children and the well-being of their families; they give them skills and experience and help prepare them to become productive members of society during their adult lives.

The participation of children or adolescents in work that does not affect their health and development or interfere with their schooling is generally seen as something positive. This includes activities such as helping parents around the house, helping out with the family business, or earning pocket money outside school hours and during school holidays. Such activities contribute to the development of children and the well-being of their families; they give them skills and experience and help prepare them to become productive members of society during their adult lives.

Child labor, which is condemned by the international community, can be divided into three categories:

- Indisputably the worst forms of child labor, which are internationally defined as slavery, child trafficking, bonded labor and other forms of forced labor, forced recruitment of children for use in armed conflicts, for the purposes of prostitution and pornography, as well as other illegal activities;

- labor performed by a child who has not reached the minimum age established for this type of work (in accordance with national legislation and on the basis of accepted international standards), which thus may interfere with the education of the child and his all-round development;

work that endangers the physical, mental or moral well-being and development of a child, either because of its nature or the conditions in which it is performed, which is known as "dangerous and harmful work".

- New global estimates and trends are presented in three categories: economically active children, child labor and children in hazardous and hazardous work.

The emerging global picture is thus very encouraging: child labor is declining, and the rate of decline is greater the more hazardous the work and the greater the vulnerability of children in these types of work.

One of the most effective ways to prevent the involvement of young children in hard work is to set age limits, according to which children can legally work and offer their services in the employment market. The main principles of the ILO Convention concerning the minimum age in employment and work are listed below.

- Hazardous work

Any form of work that is likely to harm the physical, mental or moral health of children, their safety or morals should not be performed by persons under 18 years of age. - Basic minimum age

The minimum age for employment must not be before the completion of compulsory schooling, which is usually 15 years.

- Light work

Children between the ages of 13 and 15 may do light work as long as it does not endanger their health or safety or interfere with their education, career guidance and training.

A better conceptual understanding of the problem of child labor has been provided at the same time as a better understanding of the outline of the problem and the causes that give rise to it. The 2002 global report noted that the vast majority of child labor (70%) is concentrated in the agricultural sector, and the informal sector accounts for the bulk of child labor compared to other sectors of the economy. In addition, gender plays a significant role in determining the different types of jobs that girls and boys perform. For example, girls are more involved in domestic work, while boys are very well represented in mines and mines. The situation worsens when many countries exclude home-based work from regulation.

Our understanding of the causes of child labor has become more refined as the problem has been examined from different scientific points of view. It has been very fruitful to consider the problem of child labor as a product of market forces - supply and demand, when the behavior of employers as well as individual households is taken into account. Undoubtedly, poverty and economic shocks play an important, if not key, role in defining the market for child labor. In turn, child labor contributes to the perpetuation of poverty. For example, according to the latest empirical research carried out by the World Bank in Brazil, entering the labor market at an early age reduces lifetime earnings by about 13-20%, which significantly increases the likelihood of remaining poor later in life.

It has been very fruitful to consider the problem of child labor as a product of market forces - supply and demand, when the behavior of employers as well as individual households is taken into account. Undoubtedly, poverty and economic shocks play an important, if not key, role in defining the market for child labor. In turn, child labor contributes to the perpetuation of poverty. For example, according to the latest empirical research carried out by the World Bank in Brazil, entering the labor market at an early age reduces lifetime earnings by about 13-20%, which significantly increases the likelihood of remaining poor later in life.

However, poverty is not a sufficient explanation for child labor, and it certainly cannot explain some of the by far worst forms of child labor. A human rights perspective is needed to focus the approach on issues of discrimination and social exclusion, which are the contributing factors to this phenomenon. The most vulnerable groups affected by child labor are often those populations that experience various forms of discrimination and social exclusion: girls, ethnic minorities, indigenous and tribal peoples, lower class or caste people, persons with disabilities, displaced individuals and populations in remote areas.

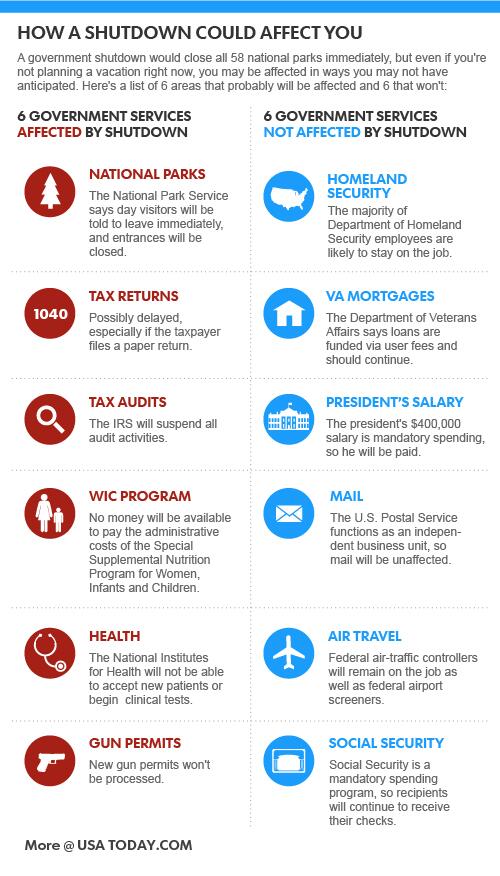

In 2002, the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Children unanimously endorsed a mainstream approach to place child labor on the development agenda. This means setting ambitious new goals for the global movement against child labor. Politically, this means that the issue of child labor is on the agenda of finance and planning ministries, because ultimately the global child labor movement must convince governments to take action to end child labor. The abolition of child labor becomes a set of policy options rather than a technocratic exercise. Moreover, everyday realities, characterized by instability and crisis, challenge attempts to achieve progress.

Child labor in Europe: a continuing challenge - Human Rights Comments -

© 2013 Volunteer Weekly

Many observers believed that child labor in Europe was a thing of the past. However, there is very strong evidence that child labor is still a significant problem and that it may increase with the advent of the economic crisis. Governments should monitor this situation and use the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the European Social Charter as recommendations for preventive and corrective action.

Governments should monitor this situation and use the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the European Social Charter as recommendations for preventive and corrective action.

In times of economic downturn, vulnerable people always suffer more than others. Therefore, the association between a decline in economic growth and an increase in child labor is not surprising. Due to the recession, many European countries have drastically reduced social assistance. And as unemployment rises, many families have found no other solution than to send their children to work.

Harmful and dangerous work

The prevalence of child labor in developing countries is a well-known problem: according to the International Labor Organization, more than 250 million children between the ages of 5 and 14 are currently working. However, when we began to analyze the situation in Europe, we found in my Office that there was very little information on this subject. In fact, it seems that this topic is taboo. However, we were able to gather enough information to paint a rather bleak picture.

However, we were able to gather enough information to paint a rather bleak picture.

According to UNESCO, 29% of children aged 7-14 work in Georgia. In Albania this figure is 19%. The government of the Russian Federation estimates that up to 1 million children work in the country. However, data are not yet available for most other countries. In Italy, a 2013 study shows that 5.2% of children under the age of 16 are employed.

Many of those children who work throughout Europe are engaged in highly hazardous work in agriculture, construction, small businesses or on the street. This is reported, for example, for Albania, Bulgaria, Georgia, Moldova, Romania, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine and Montenegro. Working in agriculture can involve dangerous equipment and tools, carrying heavy loads, and using harmful pesticides. And working on the streets leads to the fact that children are harassed and exploited.

In Bulgaria, child labor appears to be very common in the tobacco industry and some children work up to 10 hours a day. According to reports from Moldova, directors of schools, farms and agricultural cooperatives have signed agreements that require students to help with the harvest.

According to reports from Moldova, directors of schools, farms and agricultural cooperatives have signed agreements that require students to help with the harvest.

Other countries at risk are those that have been hit hard by austerity measures: Cyprus, Greece, Italy and Portugal. Quite a few children are reported to work long hours in the United Kingdom as well.

Roma children are at particular risk throughout Europe. Another particularly vulnerable group is unaccompanied migrants under the age of 18 coming from developing countries.

What to do

- Governments urgently need to focus on child labor issues, investigate, collect data and monitor. Most countries have legislation in place but do not track current practice.

- The guiding principle should be the best interests of the child, as provided for in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the standards of the European Social Charter.

- Authorities should carefully assess the potential impact on child labor of budget cuts in education and training.

- They should also analyze the impact on child labor due to cuts in social services and family support: the main reason why children are forced to work is poverty.

- Labor inspection institutions should be able to carry out their work properly.

- States must actively combat the sale of children for forced labor and exploitation. Those seven member states of the Council of Europe that have not yet ratified the Convention against Trafficking in Human Beings should do so, and all member states should cooperate with the GRETA monitoring group.

What will be the future of these children?

I am deeply concerned that so little attention has been paid to the risks of child labor in Europe. In most countries, officials are aware of this problem, but few are willing to deal with it. The very fact that data and figures are almost non-existent or very approximate is in itself a source of concern. It is impossible to fight a problem without knowing its extent, nature and consequences.

Of particular concern is that the need to work interferes with children's schooling: this quickly begins to affect their academic performance and many of them eventually leave school. And this only reproduces the vicious circle of poverty. A country can develop only when it chooses education for children, not work.

Many concrete measures need to be taken. Last year we saw one of these actions taken in Turkey, where the government passed a law that raises the compulsory education age to 17 in order to minimize the risk of labor exploitation. We need more initiatives like this.

When the problem of child labor is not addressed, it only jeopardizes the future of these children. This raises the question of what our societies will look like in the future when these children grow up without the opportunity to play and learn at school, and instead are exposed to various health risks from a very young age. We must act now for the future of these children and our own societies.