How disability may affect child development

Facts About Developmental Disabilities | CDC

Español (Spanish)

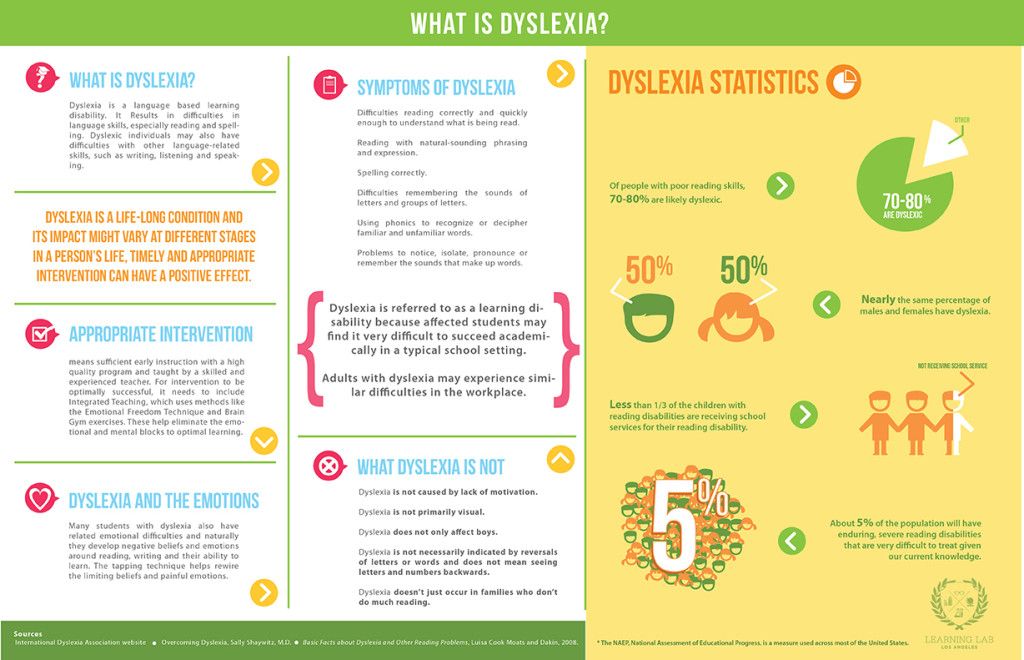

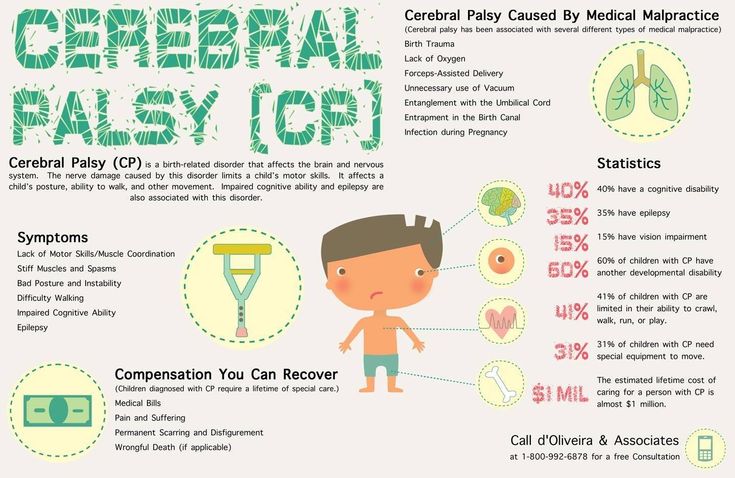

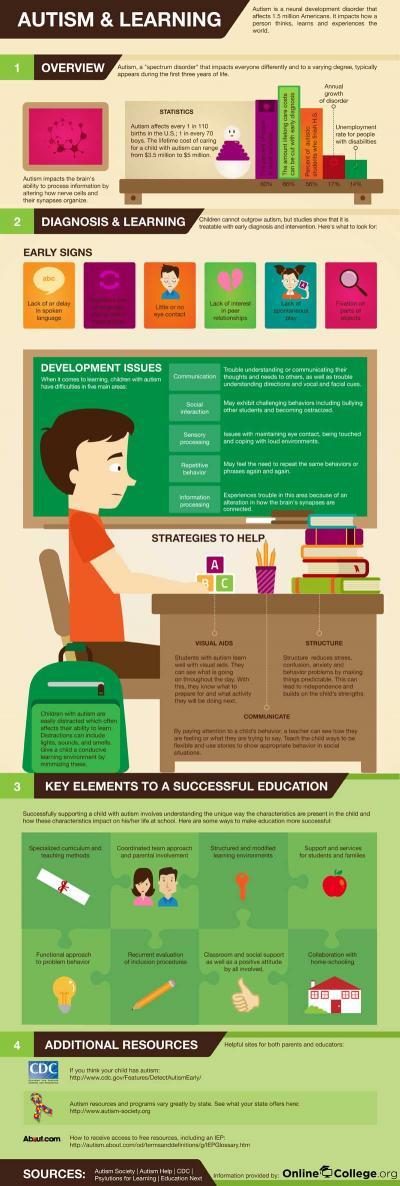

Developmental disabilities are a group of conditions due to an impairment in physical, learning, language, or behavior areas. These conditions begin during the developmental period, may impact day-to-day functioning, and usually last throughout a person’s lifetime.1

Developmental Milestones

Developmental monitoring is an active, ongoing process of watching a child grow and encouraging conversations between parents and providers about a child’s skills and abilities. Developmental monitoring involves observing how your child grows and whether your child meets the typical developmental milestones, or skills that most children reach by a certain age, in playing, learning, speaking, behaving, and moving.

Parents, grandparents, early childhood education providers, and other caregivers can participate in developmental monitoring. CDC’s Learn the Signs. Act Early. program has developed free materials, including CDC’s Milestone Tracker app, to help parents and providers work together to monitor your child’s development and know when there might be a concern and if more screening is needed. You can use a brief checklist of milestones to see how your child is developing. If you notice that your child is not meeting milestones, talk with your doctor or nurse about your concerns and ask about developmental screening. Learn more about CDC Milestone Tracker app, milestone checklists, and other parent materials.

When you take your child to a well visit, your doctor or nurse will also do developmental monitoring. The doctor or nurse might ask you questions about your child’s development or will talk and play with your child to see if they are developing and meeting milestones.

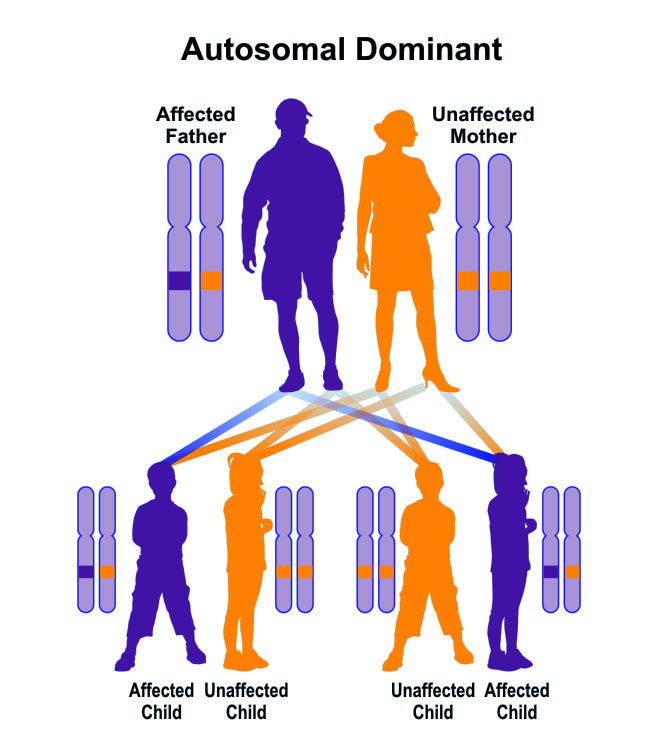

Your doctor or nurse may also ask about your child’s family history. Be sure to let your doctor or nurse know about any conditions that your child’s family members have, including ASD, learning disorders, intellectual disability, or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

If your child is not meeting the milestones for his or her age, talk to your child’s doctor and share your concerns.

Skills such as taking a first step, smiling for the first time, and waving “bye bye” are called developmental milestones.

Developmental Monitoring and Screening

Developmental screening takes a closer look at how your child is developing.

Developmental screening is more formal than developmental monitoring. It is a regular part of some well-child visits even if there is not a known concern.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends developmental and behavioral screening for all children during regular well-child visits at these ages:

- 9 months

- 18 months

- 30 months

In addition, AAP recommends that all children be screened specifically for ASD during regular well-child visits at these ages:

- 18 months

- 24 months

Screening questionnaires and checklists are based on research that compares your child to other children of the same age. Questions may ask about language, movement, and thinking skills, as a well as behaviors and emotions. Developmental screening can be done by a doctor or nurse, or other professionals in healthcare, community, or school settings. Your doctor may ask you to complete a questionnaire as part of the screening process. Screening at times other than the recommended ages should be done if you or your doctor have a concern. Additional screening should also be done if a child is at high risk for ASD (for example, having a sibling or other family member with ASD) or if behaviors sometimes associated with ASD are present. If your child’s healthcare provider does not periodically check your child with a developmental screening test, you can ask that it be done.

Developmental screening can be done by a doctor or nurse, or other professionals in healthcare, community, or school settings. Your doctor may ask you to complete a questionnaire as part of the screening process. Screening at times other than the recommended ages should be done if you or your doctor have a concern. Additional screening should also be done if a child is at high risk for ASD (for example, having a sibling or other family member with ASD) or if behaviors sometimes associated with ASD are present. If your child’s healthcare provider does not periodically check your child with a developmental screening test, you can ask that it be done.

Developmental monitoring observes how your child grows and changes over time and whether your child meets the typical developmental milestones.

References

- Developmental Disabilities: Delivery of Medical Care for Children and Adults. I. Leslie Rubin and Allen C. Crocker. Philadelphia, Pa, Lea & Febiger, 1989.

Disability and Child Development: Integrating the Concepts

Introduction

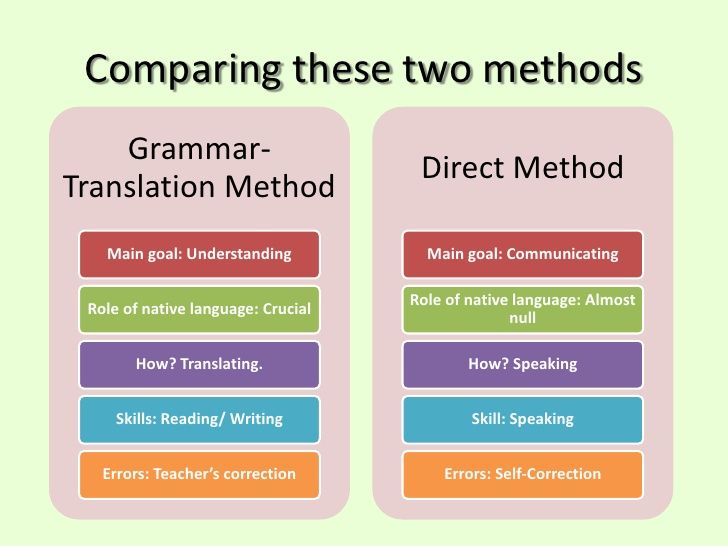

"Neurodevelopmental disabilities" refer to a diverse group of conditions and disorders that begin in the early years of children's lives, and influence their development, often for life. As professionals working in the field of developmental disability we may fail to recognize and link two important and related concepts - "development" and "disability". Theorists writing about human development have traditionally done so from the perspective of "normal" or "typical" development, with little attention to the many variations that include "disability". In the same way, schools of thought about the "treatment" of childhood (developmental) disability have focused primarily on managing the impairments that underlie the disabilities, with less attention paid to the ways that treatment can promote "normal" development (Rosenbaum, 2009).

The purpose of this Keeping Current is to review the concern that, rather than being integrated, these two streams of thought have traditionally run more or less in parallel. To do this, we first explore briefly the main tenets of several key 20th century concepts of child development. Next, we consider the assumptions underlying a number of developmental intervention approaches. Finally, drawing on modern frameworks of health and function, as well as on Ecological Systems Theory and Dynamic Systems Theory, we offer perspectives on contemporary thinking that provide an opportunity to synthesize these ideas. We also suggest new ways to conceptualize and implement intervention services to integrate "development" and "disability" more effectively.

To do this, we first explore briefly the main tenets of several key 20th century concepts of child development. Next, we consider the assumptions underlying a number of developmental intervention approaches. Finally, drawing on modern frameworks of health and function, as well as on Ecological Systems Theory and Dynamic Systems Theory, we offer perspectives on contemporary thinking that provide an opportunity to synthesize these ideas. We also suggest new ways to conceptualize and implement intervention services to integrate "development" and "disability" more effectively.

Theme I: Development

A modern definition of development refers to "systematic continuities and changes in an individual that occur between conception and death" (Shaffer, Wood, & Willoughby, 2002). All individuals develop continually in their own way and at their own pace. Consequently, everyone has a unique developmental trajectory and outcome. Historically, however, the definition of development has been somewhat rigid and prescriptive, with assumptions about the nature and timing of normal developmental pathways, and by implication seeing variations of these patterns as evidence of abnormality (Rosenbaum, 2006).

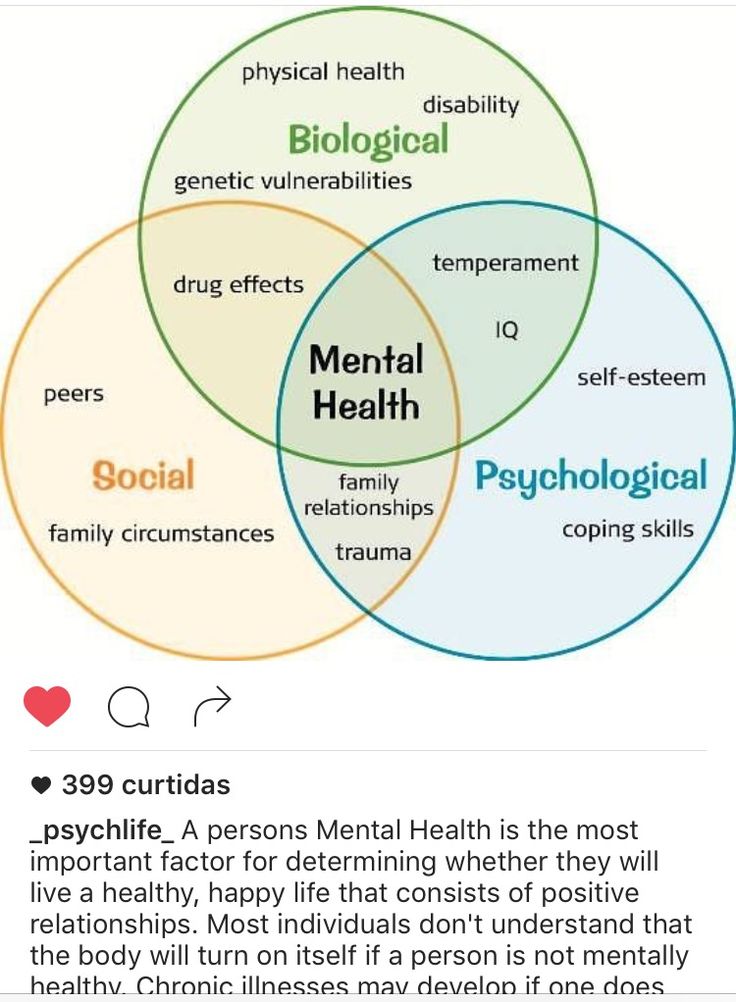

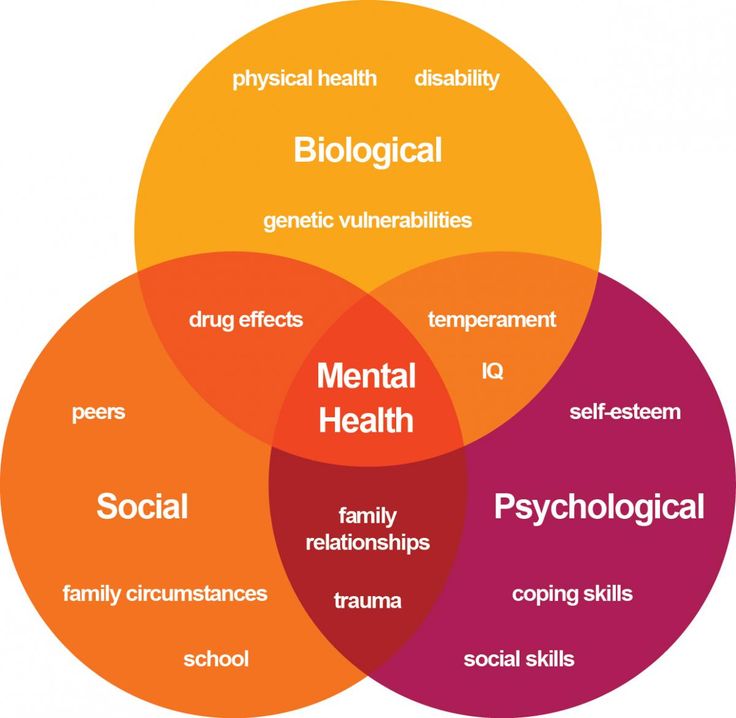

There are many theories about how development emerges throughout childhood. These explain ideas about cognitive, behavioural, biological, and personality development. Traditional theories about development (such as Piaget's theory of cognitive development [Inhelder, Sinclair, & Bovet, 1974], Gesell's Ethological theory [Gesell & Amatruda, 1947], Erikson's psychosocial theory and learning theories [1964]) generally view development as the process that takes place in "normal" individuals. Based on observations of milestones reached in "normal" people, these theories also tend to focus on one type of influence (for example, biological, parental, or environmental factors) resulting in a "right" developmental path. None of these theories explicitly uses disability as a factor to test or illustrate the robustness of the theory by applying it to situations outside the norm.

Learning theorists were among the first to expand their thinking beyond the idea that there is one universally applicable correct path for development. According to Bandura (1992), humans have a few innate processes which are either present at birth or develop shortly thereafter. The emergence of other behaviours is dependent on a number of factors. An individual's state of development is the result of their behaviour, internal events (such as beliefs, expectations, self-perception, goals, intentions, physical structures, sensory and neural systems) and the external environment, including social influences, roles in society and the physical environment (Bandura, 1992).

According to Bandura (1992), humans have a few innate processes which are either present at birth or develop shortly thereafter. The emergence of other behaviours is dependent on a number of factors. An individual's state of development is the result of their behaviour, internal events (such as beliefs, expectations, self-perception, goals, intentions, physical structures, sensory and neural systems) and the external environment, including social influences, roles in society and the physical environment (Bandura, 1992).

One element common to these developmental theories is the relatively narrow way they view influences on development. This contrasts sharply with current understanding of development that views a developmental outcome as the product of a seemingly infinite number of processes. These ideas are discussed in more detail below.

Theme II: Disability and its Management

There are many opinions about the best approaches to the treatment of childhood developmental disabilities. Historically, a wide variety of theoretically-based treatment approaches have been proposed. The way professionals and society in general, view disability has been continually evolving. With advances in our understanding of biomedicine, new theories are always emerging, in turn spawning new treatment models that may someday become a standard treatment.

Historically, a wide variety of theoretically-based treatment approaches have been proposed. The way professionals and society in general, view disability has been continually evolving. With advances in our understanding of biomedicine, new theories are always emerging, in turn spawning new treatment models that may someday become a standard treatment.

For decades, neurologically-based interventions for children with neurodisabilities have been founded on the idea of disability as a sensorimotor problem. Examples of this type of treatment approach include muscle re-education, Vojta therapy, sensory integration, and the most popular neurological model of treatment for motor disorders, neurodevelopmental treatment. The main objective of these treatment programs (usually implicit rather than stated formally) is to address "impairments" (World Health Organization [WHO], 2002) and hopefully resolve the underlying problem. The common aspect of many of these long-accepted treatment approaches is that they look at a child with a disability as a child with a problem. They assess the child and their difficulties and then try to find ways to improve the outcomes. The traditional focus has been primarily on interventions that address the underlying biomedical impairments.

They assess the child and their difficulties and then try to find ways to improve the outcomes. The traditional focus has been primarily on interventions that address the underlying biomedical impairments.

A recent evolution in thinking has begun to gain currency in the treatment and management of childhood disabilities. This perspective reflects a shift beyond therapies that try to fix the problem, toward approaches that promote activity and participation in a child's daily life activities. This way of thinking is not primarily concerned with ensuring that things be done "normally", but strives instead to enable the child to function to the best of their ability, whatever that ability may look like.

The Integration of Disability and Development

Considering the potential scope for interaction between concepts of "developmental disability" and of "child development", it is surprising how little has been written about their intersection. The works of developmental theorists are particularly disappointing in this regard. None of the prominent theories mentioned above has taken a close look at what happens to development when something goes wrong, or how disability might affect developmental trajectories. Nor have developmental differences been used to test developmental theories. This is a significant gap in the developmental literature, because a developmental theory which could truly be applied universally should have to be able to accommodate those with disabilities.

None of the prominent theories mentioned above has taken a close look at what happens to development when something goes wrong, or how disability might affect developmental trajectories. Nor have developmental differences been used to test developmental theories. This is a significant gap in the developmental literature, because a developmental theory which could truly be applied universally should have to be able to accommodate those with disabilities.

Intervention strategies generally attempt to do one of two things. Put very simply, they aim either to fix the problem or to encourage function to emerge in spite of the problem. In the literature describing most of the treatment approaches referred to above, there is little mention of the consequences of disability on areas of development other than sensorimotor systems (Rosenbaum, 2009). There is even less mention of how these developmental and functional difficulties might be prevented (Rosenbaum, 2008).

The Next Generation of Concepts

The way we think about disability and development has begun to change. With these changes come new possibilities for approaching the treatment of children with disabilities. These new ideas look at health and development broadly, seeing them as complex webs of interaction rather than as simple chains of timed events. Bronfenbrenner (1992) was perhaps the first developmentalist to characterize development in this way, but he was not alone. Dynamic Systems Theory (Thelen, 1995) has also embraced the idea of multiple factors interacting to create a developmental outcome. In many ways, the WHO's new framework of Health, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF; WHO, 2002), mirrors the ideas of Bronfenbrenner and Dynamic Systems Theory, using components of health status as the outcome rather than characteristics of development. These ideas are discussed briefly below.

With these changes come new possibilities for approaching the treatment of children with disabilities. These new ideas look at health and development broadly, seeing them as complex webs of interaction rather than as simple chains of timed events. Bronfenbrenner (1992) was perhaps the first developmentalist to characterize development in this way, but he was not alone. Dynamic Systems Theory (Thelen, 1995) has also embraced the idea of multiple factors interacting to create a developmental outcome. In many ways, the WHO's new framework of Health, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF; WHO, 2002), mirrors the ideas of Bronfenbrenner and Dynamic Systems Theory, using components of health status as the outcome rather than characteristics of development. These ideas are discussed briefly below.

A: Ecological Systems Theory

The most important contribution to the field of human development from psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner's writing is his suggestion that it is not one or a few processes that determine how an individual will develop, but rather the interaction of many processes across time and space. Bronfenbrenner's theory emphasizes how a person's biological characteristics interact with environmental forces to shape their development. His idea is that genetic material does not produce finished traits but interacts with environmental experiences to determine developmental outcomes. This way of thinking allows one to recognize that many characteristics that are attributed largely to heritability (such as height) can be impacted by environmental systems (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). At the same time, the idea of interaction suggests that similar environmental conditions will lead to different outcomes in different people (Bronfenbrenner, 1992).

Bronfenbrenner's theory emphasizes how a person's biological characteristics interact with environmental forces to shape their development. His idea is that genetic material does not produce finished traits but interacts with environmental experiences to determine developmental outcomes. This way of thinking allows one to recognize that many characteristics that are attributed largely to heritability (such as height) can be impacted by environmental systems (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994). At the same time, the idea of interaction suggests that similar environmental conditions will lead to different outcomes in different people (Bronfenbrenner, 1992).

Bronfenbrenner does not explain the consequences of specific influences. He does not go so far as to say which influences should be avoided, which influences should be sought out, and which influences are irrelevant for a particular child. This type of information is critical if one wishes to evaluate the impact of a disability on various aspects of a child's development. What he does offer is a model that suggests the possibility that there may be many points of entry when looking to improve the life situation and developmental well-being of an individual with a disability.

What he does offer is a model that suggests the possibility that there may be many points of entry when looking to improve the life situation and developmental well-being of an individual with a disability.

B: Dynamic Systems Theory

Analogous to Bronfenbrenner's ideas, Thelen's way of thinking about development understands movement as resulting from the merging of several processes and constraints within both the individual and their environment (Thelen, 1995). A certain motor pattern will be preferred in any given context, because while other movement patterns may be possible, they are less likely to be seen because they are less efficient, or are more difficult to perform. Movement patterns will change over time as the constraints in the person and their environment change. While each individual will find their own unique way of doing things, preferred patterns will be similar, as the environmental and biomechanical constraints are similar. (One might think of the infinite variety of ways professional baseball hitters stand at the plate. There is clearly no one "normal" way to be successful as a batter!)

There is clearly no one "normal" way to be successful as a batter!)

Dynamic Systems Theory allows one to look at disability in a new light. It suggests that a quest for normality in movement patterns may be inappropriate. If an individual will naturally develop a motor behaviour that works best for them, even if that pattern is associated with disability, should it be inhibited and treated, or accepted as a characteristic of that individual? This way of thinking allows therapists to accept atypical behaviours as appropriate for a specific individual, and to work with their clients to develop any solution to the problem of completing a desired activity that works for that person, even if it is not performed "normally".

C: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is a multipurpose framework and classification system developed by the WHO. It recognizes that diagnosis does not automatically translate directly into functional status, prognosis, or level of care and services provided. The ICF is used to describe and measure health, not to give a diagnosis or prognosis (WHO, 2002).

The ICF is used to describe and measure health, not to give a diagnosis or prognosis (WHO, 2002).

The value of ICF over other ways of describing and evaluating disability and functioning is related to the interconnectedness of the elements. Whereas diagnosis classically depends on "ruling out" competing possibilities, the ICF encourages people to "rule in" relevant elements of an individual's situation. The ICF framework has a number of components (such as, health condition or disease, dimensions of body function and structure, activity at the personal level and participation in society) that interact with each other. This allows for many points of entry when intervening to enhance activity or participation. In addition, the two contextual elements (environmental and personal factors) remind people to recognize the individuality of each person and the uniqueness of their situation, as well as the role of environmental influences on people's lives. Evaluation and modification of environmental factors can be used to narrow the gap between capacity (a person's best abilities) and performance (what they usually do). Consideration of personal factors allows one to tailor interventions that focus on areas of importance to the individual.

Consideration of personal factors allows one to tailor interventions that focus on areas of importance to the individual.

In viewing function as the result of interactions between health conditions and personal and environmental contextual factors, the ICF suggests ways to improve all levels of human functioning. One need not focus exclusively on any one component, but rather use as many strategies as are relevant to that situation, particularly when the efficacy of a specific treatment approach is limited. In designing treatment programs with the ICF in mind, one can combine interventions to try to improve many aspects of human functioning, often simultaneously, and thus enhance a person's functional status at all three levels.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In an era of systemic models and frameworks, we believe that there are great opportunities to expand traditional thinking about disability beyond the biomedical dimensions of these conditions. We would argue that it is important to promote function and child development with a wider focus on what is acceptable (beyond 'normal"). We believe that therapists and intervention programs should make a concerted effort to encourage children with disabilities to participate in whatever ways are optimal for them. Such an approach challenges us to move beyond the traditional emphasis on "repair" and "normality" in favour of broader goals that promote function, participation and engagement in life.

We believe that therapists and intervention programs should make a concerted effort to encourage children with disabilities to participate in whatever ways are optimal for them. Such an approach challenges us to move beyond the traditional emphasis on "repair" and "normality" in favour of broader goals that promote function, participation and engagement in life.

There are enormous research opportunities inherent in this emerging approach to our work with children with disabilities and their families. These include assessing the relationships between changes in the biomedical aspects of children's disabilities and the impact of these changes on activity, participation, quality of life and satisfaction with treatments. Much remains to be done both to create therapeutic paradigms built on these current models, and to evaluate the effectiveness of new theories and systems, so that today's new ideas are well supported tomorrow with solid evidence.

Disability

Disability- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 About

- P

- P

- With

- T

- in

- F

- x

- 9000.

- Sh.

- B

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

- Popular Topics

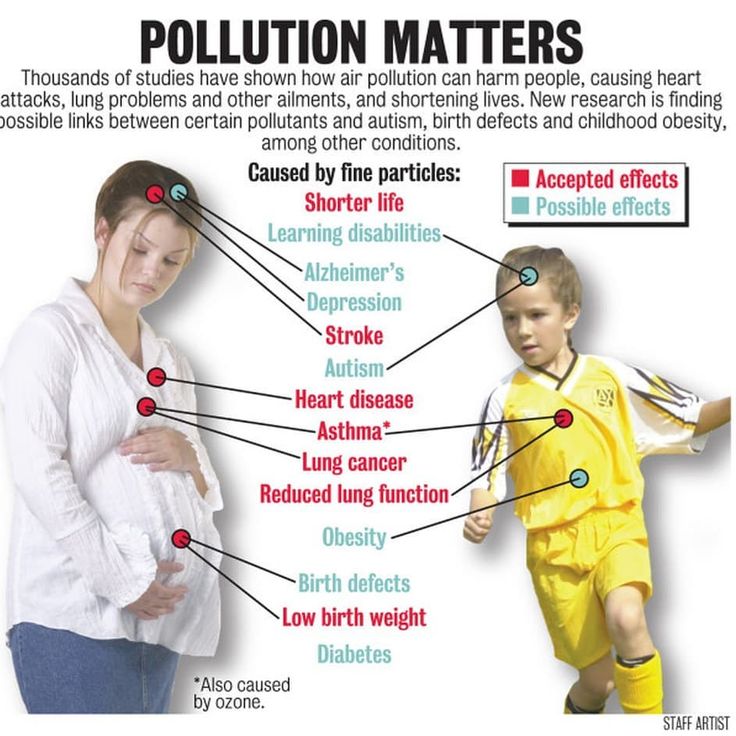

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- Newsletter

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find a country »

- A

- B

- C

- g

- d

- E

- ё

- С

- and

- th

- to

- L

- N 9000 T

- in

- F

- x

- 9000 WHO in countries » nine0003

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A nine0005

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO Data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Highlights " nine0005

- About WHO »

- General director

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/ nine0004 Disability

WHO/Y. Shimizu

Shimizu

© A photo

Key Facts

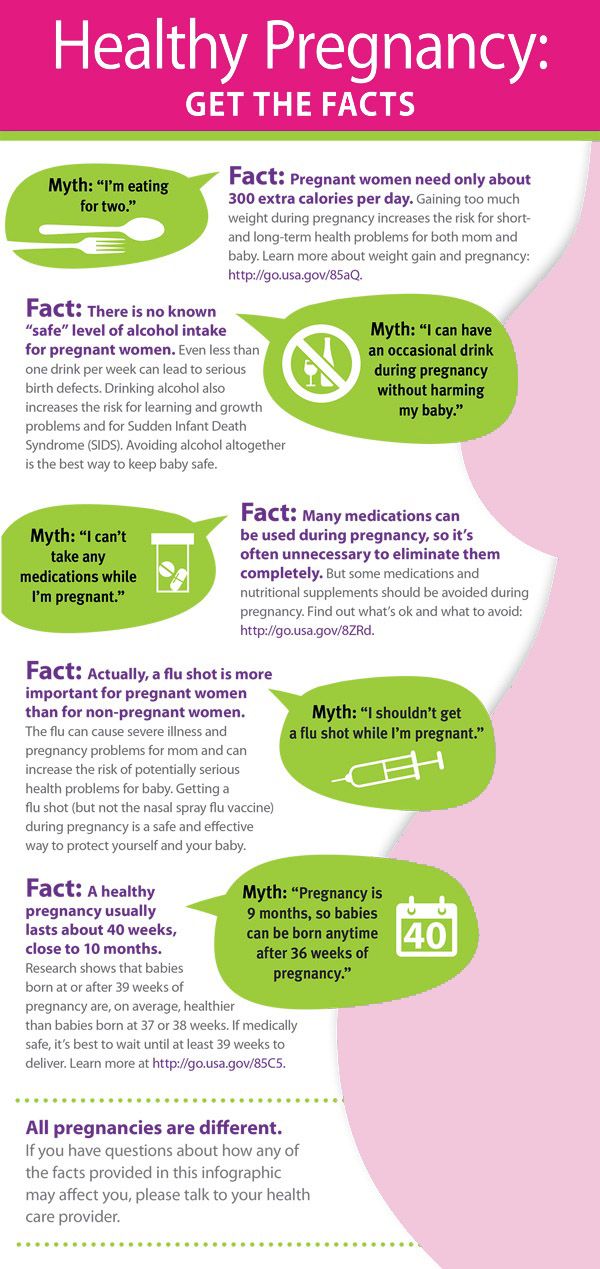

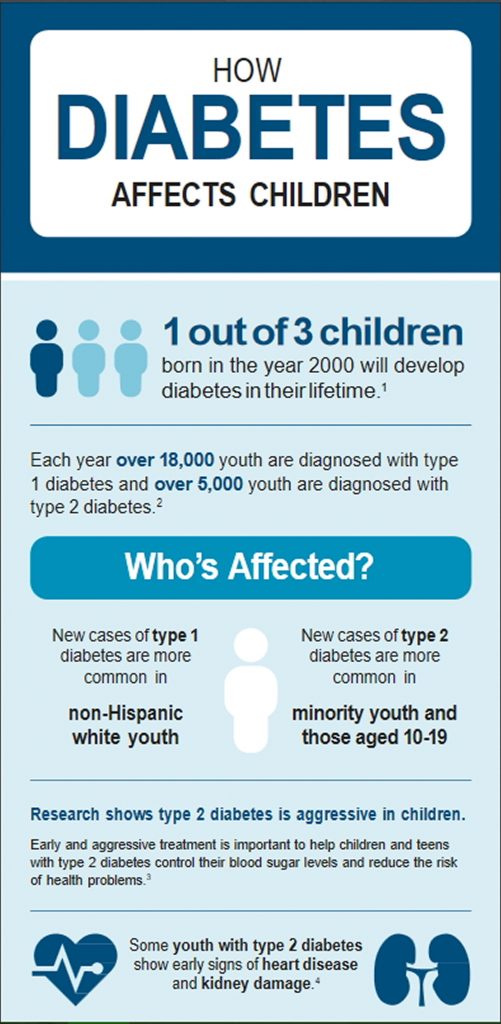

- It is estimated that 1.3 billion people, or one in six people in the world, suffer from a significant disability.

- Some people with disabilities die before people without disabilities, and this life expectancy gap can be up to 20 years.

- People with disabilities are twice as likely to develop conditions such as depression, asthma, diabetes, stroke, obesity and dental disease. nine0005

- People with disabilities are almost six times more likely to be unable to use health facilities due to a lack of accessibility.

- People with disabilities are 15 times more likely to experience inaccessibility and cost of transportation compared to people without disabilities.

- Inequitable conditions in which people with disabilities find themselves, including stigmatization, discrimination, poverty, lack of education and employment, as well as restrictions imposed by the health system itself, lead to unequal opportunities for protecting the health of people with disabilities.

nine0005

nine0005

General information

Disability is a common phenomenon faced by many people in their life. It is the result of an interaction between certain health conditions (dementia, blindness, spinal cord injury, etc.) and a number of environmental factors and individual factors. Currently, it is estimated that 1.3 billion people, or 16% of the global population, suffer from significant health disabilities. Increasing prevalence of noncommunicable diseases and the aging of the population leads to an increase in their numbers. People with disabilities represent a diverse population whose life experiences and health needs are influenced by factors such as gender, age, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, race and ethnicity, and economic status. Compared to the rest of the population, people with disabilities die earlier, have poorer health outcomes and face more restrictions in daily activities. nine0285

Factors that exacerbate health inequities

Health inequities are caused by the unequal conditions in which people with disabilities live.

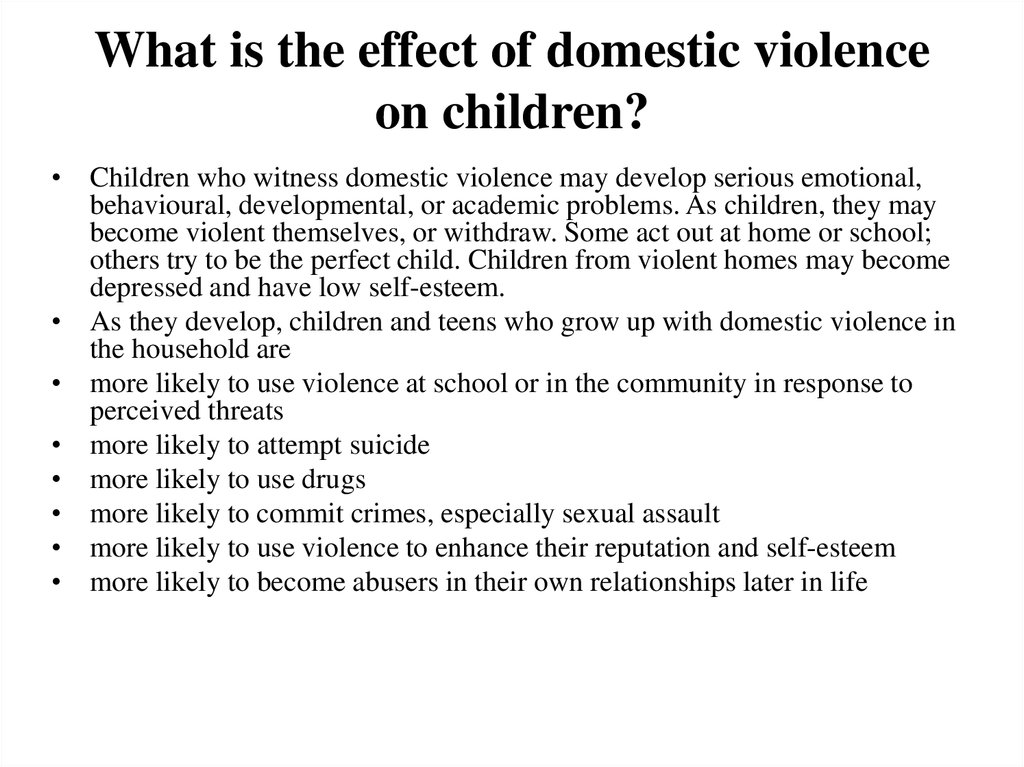

Structural factors. People with disabilities face prejudice due to their disability, stigmatization and discrimination in all areas of life, which affects their physical and mental health. Legislation and policies can deprive such people of the right to make their own decisions and allow for a range of harmful practices in the health sector, including forced sterilization, involuntary hospitalization and treatment and even placement in specialized closed institutions. nine0285

Social determinants of health. Factors such as poverty, lack of education and employment, and difficult living conditions increase the risk of poor health and neglect of people with disabilities. medical care. People with disabilities who are not covered by formal social support mechanisms can only receive health care and participate in public life with the support of their family members, which puts them at a disadvantage not only the people with disabilities themselves, but also the people who care for them (most of whom are women and girls). nine0285

nine0285

Risk factors. People with disabilities are more likely to be exposed to noncommunicable disease risk factors such as smoking, unhealthy diets, alcohol use and physical inactivity. This is mainly explained because they are often not covered by public health interventions.

Health system. People with disabilities face restrictions in accessing all types of health care. Thus, lack of knowledge, negative attitudes and discriminatory treatment by health workers; the impossibility of unhindered access to medical institutions and obtaining information; ignorance about the issue of disability and the absence of mechanisms for collecting and analyzing relevant data - all these phenomena exacerbate unfair disparities health care opportunities for this population. nine0285

International documents

Countries are required by international human rights law and, in some cases, domestic law to address health inequities faced by people with disabilities. The principle of justice with regard to health for people with disabilities is addressed in two international instruments.

The principle of justice with regard to health for people with disabilities is addressed in two international instruments.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities places an obligation on States Parties to provide people with disabilities with the same range, quality and level of free or low-cost health care services as others. nine0285

World Health Assembly resolution WHA74.8 on the highest attainable standard of health for people with disabilities calls on Member States to ensure that people with disabilities receive effective health services within the framework of universal health coverage; equal protection in emergencies; and equal access to intersectoral public health interventions.

Health for all

Disability mainstreaming is essential to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and global health priorities for the health of all. nine0285

Universal health coverage is impossible without providing people with disabilities with quality health services on an equal basis with other people. Devoting resources to universal health coverage for people with disabilities will improve position not only of individuals, but of the population as a whole.

Devoting resources to universal health coverage for people with disabilities will improve position not only of individuals, but of the population as a whole.

For every US dollar spent on developing noncommunicable disease prevention and management programs that reach people with disabilities, a return of almost US$ 10 can be realized. nine0285

People with disabilities should be included in the prevention and response to health emergencies, as they are more likely to experience the direct and indirect effects of such emergencies. So, during the COVID-19 pandemic, when people with disabilities living in closed institutions were literally cut off from society, facts were established that they were prescribed excessive medication and sedatives, kept in locked premises, as well as cases of self-harm among residents of such institutions (1).

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen higher death rates among people with intellectual disabilities (2) , who are also less likely to receive intensive care (3) .

The goals of improving public health by combating air and water pollution, ensuring road safety and combating violence against women can only be achieved if public health measures are will generally be carried out taking into account the needs, skills and abilities of people with disabilities. nine0285

Women with disabilities are two to four times more likely to experience intimate partner violence than women without disabilities (4) .

The WHO report on health equity for people with disabilities presents 40 key actions that countries need to take to strengthen health systems and reduce inequities in health care. health care faced by people with disabilities. To do this, governments of all countries and all partners in the health sector can perform three tasks. First, they must take into account the principle of fairness in relation to health for people with disabilities in all areas of the health sector. Second, they can involve people with disabilities in decision-making processes. Third, they can track the coverage of health sector interventions and their effectiveness in meeting the needs of people with disabilities. nine0362

Third, they can track the coverage of health sector interventions and their effectiveness in meeting the needs of people with disabilities. nine0362

WHO's work

WHO's work is to ensure that people with disabilities have equitable access to effective health care; taking their interests into account as part of efforts to improve health emergency preparedness and response to them; and inclusion of people with disabilities in public health interventions across sectors to ensure the highest attainable standard of health. To achieve this goal, WHO:

- guides and supports the efforts of Member States to ensure that people with disabilities are taken into account in the organization and planning of health systems;

- promotes the collection and dissemination of data and information on disability;

- develops policy documents, including recommendations for better disability inclusion in the health sector;

- strengthens the capacity of policy makers and service organizations in health systems; nine0005

- promotes strategies to ensure that people with disabilities are informed about their health status and that health personnel uphold and protect their rights and dignity;

- contributes to the implementation of the United Nations Strategy for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (UNDIS), which aims to promote “sustainable and transformative progress towards mainstreaming the inclusion of persons with disabilities across all components work of the United Nations”; and

- provides Member States and development partners with up-to-date evidence, analysis and guidance on disability mainstreaming in the health sector.

References

- Brennan, C.S., 2020, COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor.

- Williamson, E.J., et al., Risks of COVID-19 hospital admission and death for people with learning disability: population based cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. BMJ, 2021. 374: p. n1592.

- Baksh, R.A., et al., Understanding inequalities in COVID-19 outcomes following hospital admission for people with intellectual disability compared to the general population: a matched cohort study in the UK. BMJ Open, 2021. 11(10): p. e052482.

- Dunkle, K., et al., Disability and violence against women and girls . 2018, UKaid: London.

How to solve the problem of refusals to assign disabilities to children?

A working meeting was held in the Federation Council on the problems of assigning the appropriate status to children with disabilities. The decision to study this issue was made at the 372nd meeting of the Chamber on the initiative of the Deputy Chairman of the Federation Council Committee on Constitutional Legislation and State Construction Lyudmila Bokova .

The senator said that a number of regions are receiving complaints about the difficulties that have arisen this year with the registration of disability for minors. There is a growing number of cases when institutions of medical and social expertise, based on the results of medical and diagnostic measures, refuse to assign the status of a "disabled child" to children who were considered disabled for several years and received the necessary social protection and rehabilitation on the basis of this. “Failure to receive the proper level of rehabilitation will greatly affect the health of the child,” emphasized Ludmila Bokova .

See also

Disabled children urgently need support — L. Bokova

L. Bokova: We will deal with the problem of refusal to assign disability to minors

L. Bokova: Discussion of a new version of the order concerning children with disabilities should be held with the participation of experts at the site of the Federation Council

Bokova: Discussion of a new version of the order concerning children with disabilities should be held with the participation of experts at the site of the Federation Council

“Today, as they explain to us, state institutions remove the status of a disabled child due to the absence of “conditions for recognizing a citizen as disabled” at the time of examination. This is the interpretation of the order of the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection No. 664n of September 29, 2014 "On the classifications and criteria used in the implementation of medical and social examination", according to which not only qualitative, but also quantitative assessments of persistent violations of body functions were introduced. On the basis of these assessments, the degree of impairment of body functions is assigned, allowing one or another group of disability to be obtained. nine0285

nine0285

According to the senator, such an approach, on the one hand, makes it possible to more accurately classify violations of bodily functions, on the other hand, it deprives some children and their parents of the necessary social protection.

The Federation Council supports the decision of the Ministry of Justice of Russia to cancel Order 664n of the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of the Russian Federation "On the classifications and criteria used in the implementation of medical and social examination of citizens by federal state institutions of medical and social examination." Senators are in favor of discussing a new, more comprehensive draft of the relevant order at the site of the Federation Council with the participation of experts. nine0285

This was stated by the Deputy Chairman of the Federation Council Committee on Constitutional Legislation and State Building Lyudmila Bokova at a meeting of the Council for Disabled People under the Federation Council.