How did lewis hine help child labor

How Photography Ended Child Labour in the USA

Gina Mussio

28 October 2016

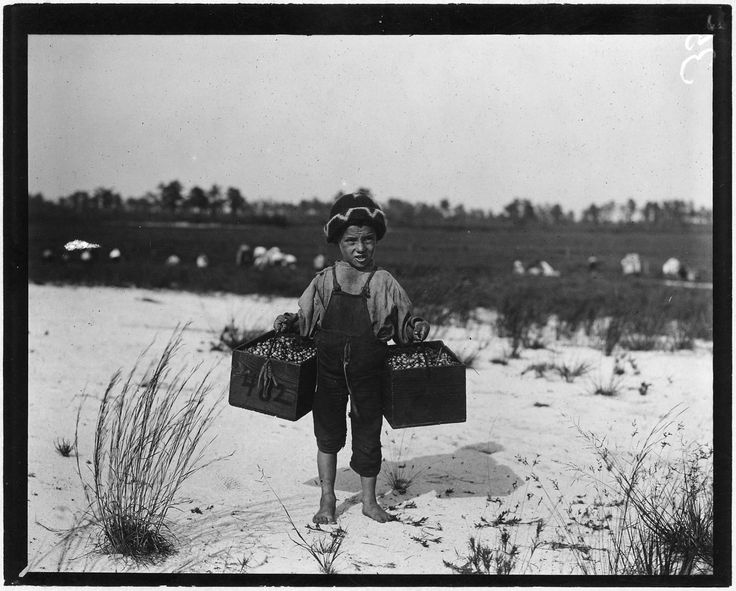

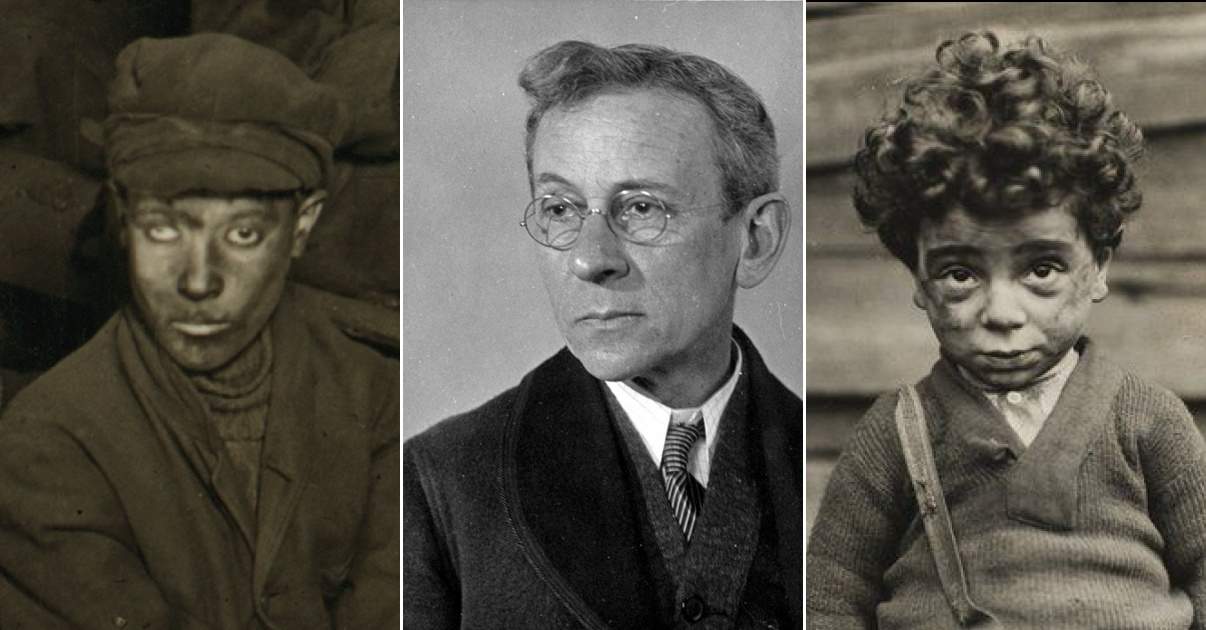

Photography is a powerful art form. It’s caused us to change the way we view things and continues to change what we know to be true. Lewis Hine might be one of the form’s greatest actors for change: through his work the American photographer has changed American consciences, using his camera as a tool to document the harsh conditions of American workers, particularly children – and ultimately bringing about reform in U.S. child labor laws.

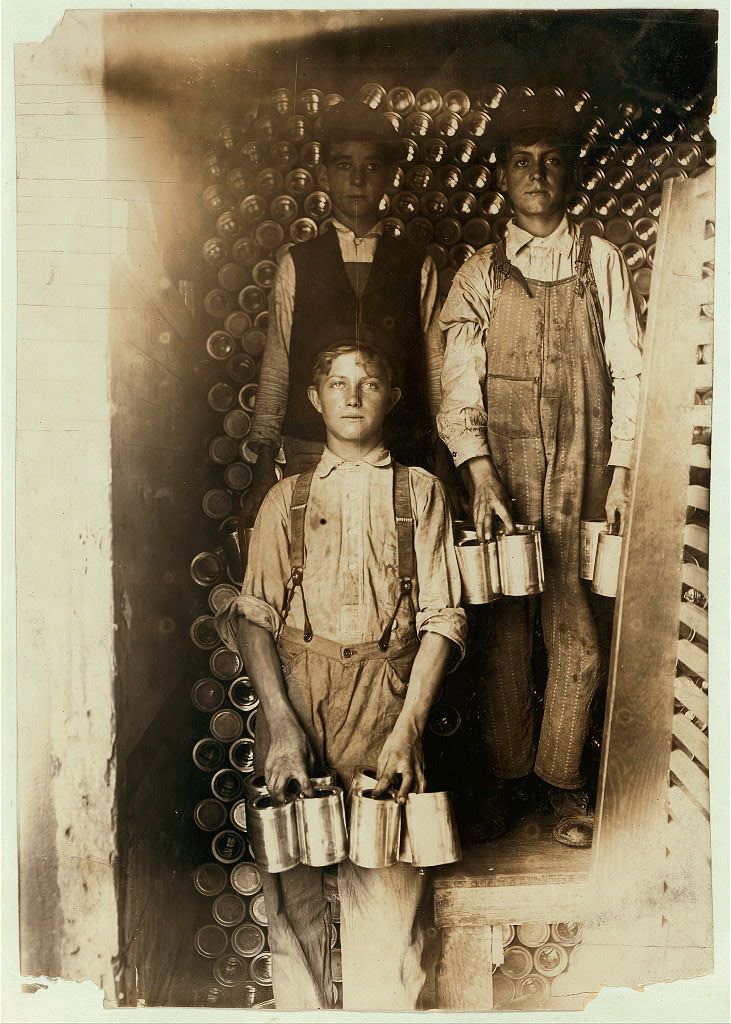

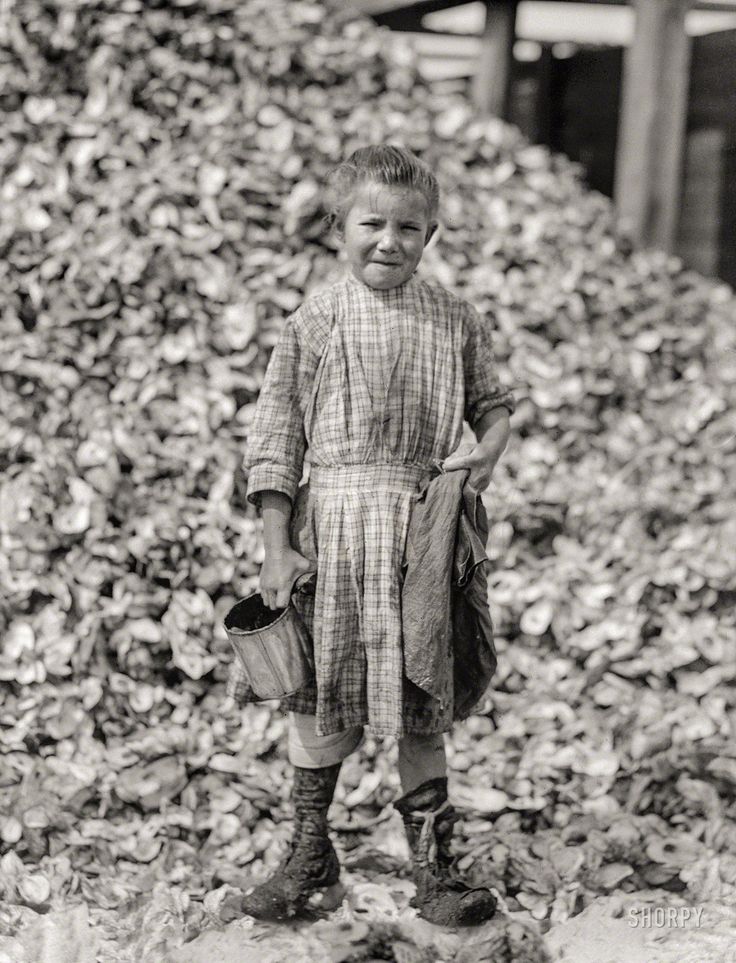

Lewis Hine, ‘Maud and Grade Daly, five and three years old, shrimp pickers, Bay St Louis, Mississippi | Courtesy of Library of Congress

Born in 1874 in Wisconsin, Hine didn’t start off as a photographer. After his graduation from the University of Chicago in 1901 he taught botany and nature studies at the Ethical Culture School in New York City. It was there, after a colleague suggested he use photography as a tool for his classes, that Lewis Hine as a photographer was born.

With a constant interest in social welfare and reform movements, Hine was particularly drawn to the conditions of immigrants in the United States. In 1905 he began his first documentary series on immigration, focusing on the waves of newly arrived immigrants at Ellis Island. He photographed this ‘new immigration’, the recent influx of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, from 1904 until 1909. The families that left Ellis Island and poured into cities, factories and farms heavily influenced his subsequent work in child welfare and the social conditions of the American working class.

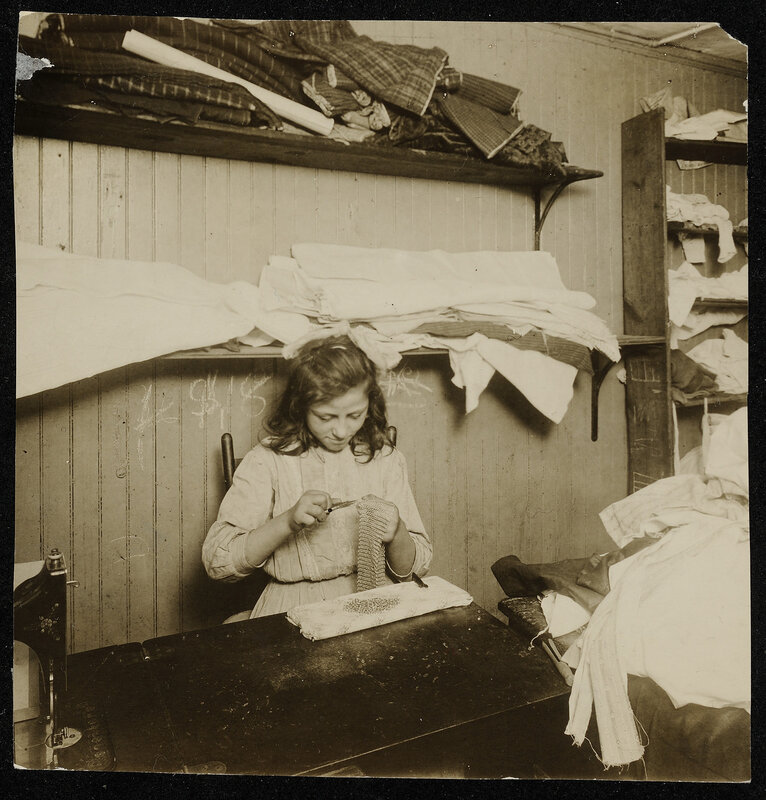

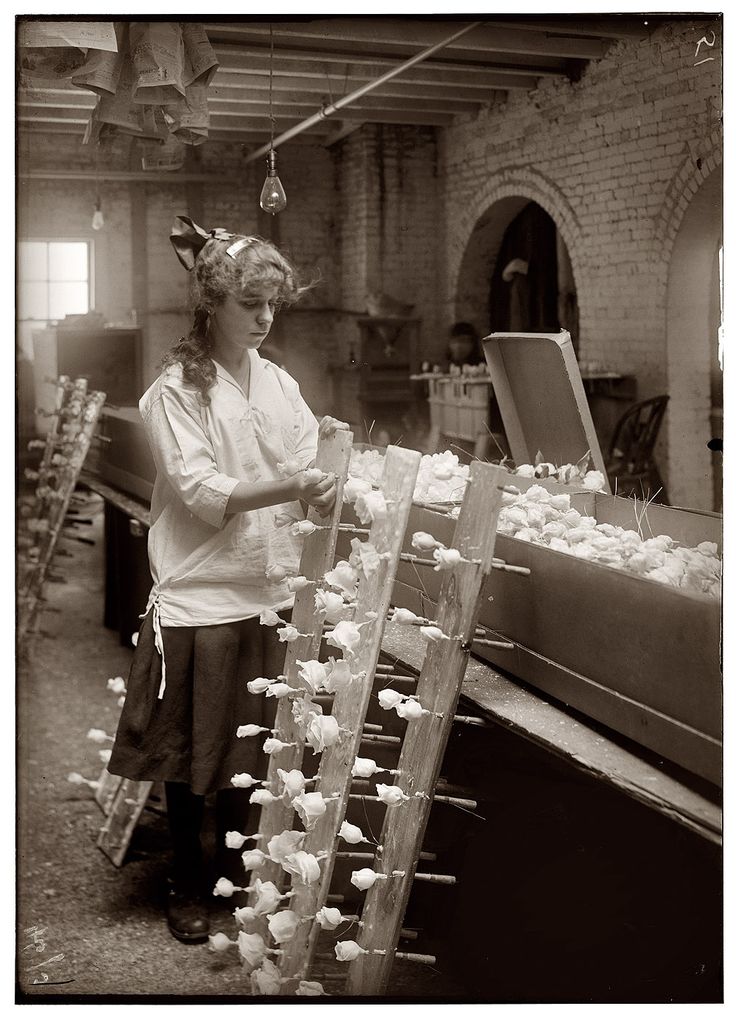

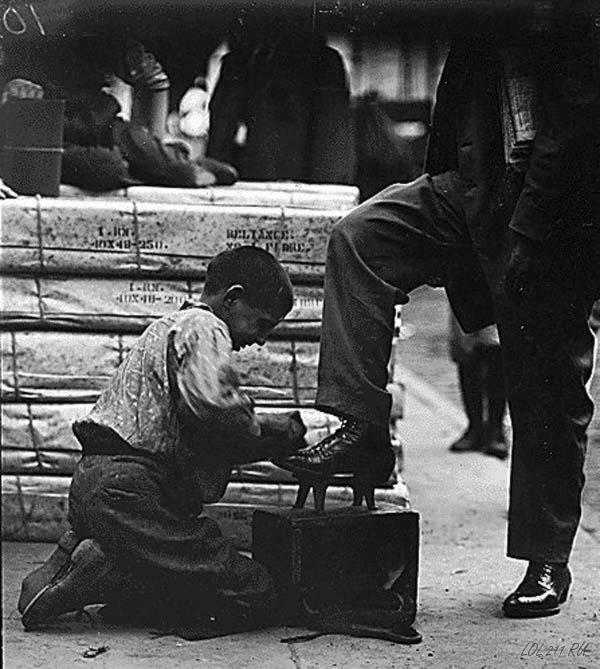

Often photographers and photojournalists find a cause to support with their photography, Lewis Hine found photography to support his cause. Hine traveled the country, taking pictures of children working in factories, mines, farms, and shops. He interviewed and photographed children working as newsboys, sales ‘men’ and seafood workers.

Lewis Hine, Group of Breaker Boys | Courtesy of UMBC Photographers & Collections Index

He was a good teacher, used to working with children, and gained their trust quickly. If a child didn’t know his or her age or refused to give it, he surreptitiously measured their height using the buttons on his vest and calculated the age accordingly.

If a child didn’t know his or her age or refused to give it, he surreptitiously measured their height using the buttons on his vest and calculated the age accordingly.

In one photo caption of a young girl with two pig-tailed braids looking straight at the camera, Hine wrote: ‘One of the spinners in Whitnel Cotton Mill. She was 51 inches high. Has been in the mill one year. Sometimes works at night. Runs 4 sides – 48 cents a day. When asked how old she was, she hesitated, then said, ‘I don’t remember’, then added confidentially, ‘I’m not old enough to work, but do just the same’. Out of 50 employees, there were ten children about her size’. Another photograph, taken in Jersey City, New Jersey, shows a small body crumpled across two stairs, newspapers being used as a makeshift pillow; a young newsboy is taking a break for some sleep.

In 1910 there were approximately two million children under the age of 15 working in the U.S. But by the early 1900s child labor was beginning to be seen by many as child slavery. Hine said, ‘There is work that profits children, and there is work that brings profit only to employers. The object of employing children is not to train them, but to get high profits from their work’.

Hine said, ‘There is work that profits children, and there is work that brings profit only to employers. The object of employing children is not to train them, but to get high profits from their work’.

Lewis Hine, Seven year old Rosie, oyster shucker, Bluffton, South Carolina, 1913 | Courtesy of Library of Congress

Hine’s documentary project and passion for reform continued to grow and in 1908 he quit teaching to work as an investigative photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), an organization established to abolish child labor. Hine was one of many photographers hired by the organization to investigate and gather evidence of the squalid conditions many children worked in. His photos formed exhibitions, were made into slides for lectures and printed in magazine articles and pamphlets, directly influencing the state of children in the U.S.

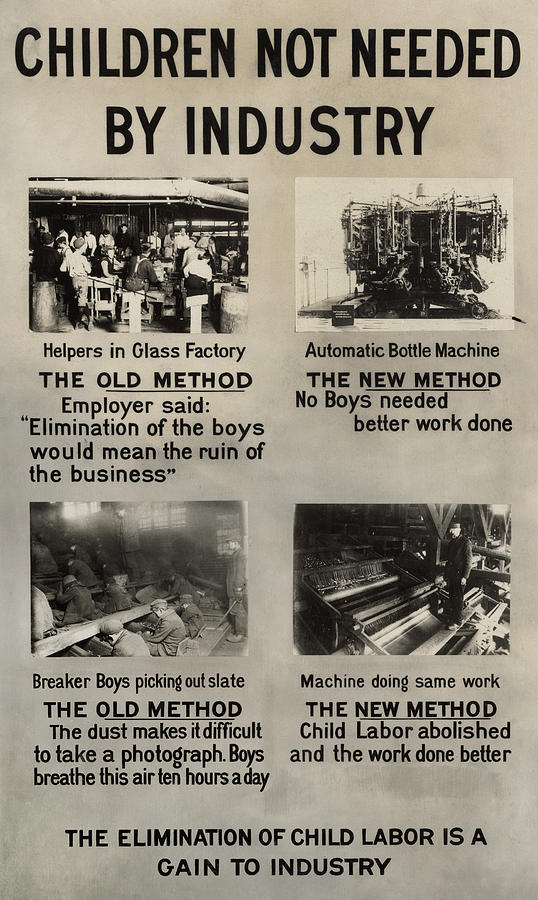

Eventually these efforts led the Children’s Bureau to be transferred to the Department of Labor, an important step in the fight against child labor. Finally in 1916 Congress passed the Keating-Owens Act, establishing a minimum age of 14 for workers in manufacturing and 16 for workers in mining and an eight-hour workday maximum, among other things. Unfortunately this law was deemed unconstitutional in that congressional control of interstate commerce did not control conditions of labor. While it was a blow to the child labou movement, by 1920 the number of child workers was nearly half of that in 1910.

Finally in 1916 Congress passed the Keating-Owens Act, establishing a minimum age of 14 for workers in manufacturing and 16 for workers in mining and an eight-hour workday maximum, among other things. Unfortunately this law was deemed unconstitutional in that congressional control of interstate commerce did not control conditions of labor. While it was a blow to the child labou movement, by 1920 the number of child workers was nearly half of that in 1910.

Lewis Hine, Child Labourer | Courtesy of Library of Congress

Hine continued to work for social reform over the years, photographing for sociological studies, magazines and for the American Red Cross in Europe right after World War I. In 1926 he went back to Ellis Island to update his record, observing and documenting what reforms had and had not been made.

Hine once said, ‘There were two things I wanted to do. I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected; I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated’. His records of child laborers were stark proof of what needed to be corrected and his following project sought to bring out the dignity in work. He spent all of 1930 documenting the construction of the Empire State Building, taking hundreds of photos of the workers and work conditions. In 1932 he compiled his records into an exhibition and a book titled Men at Work.

His records of child laborers were stark proof of what needed to be corrected and his following project sought to bring out the dignity in work. He spent all of 1930 documenting the construction of the Empire State Building, taking hundreds of photos of the workers and work conditions. In 1932 he compiled his records into an exhibition and a book titled Men at Work.

By that point, interest in Hine’s work was dying down, his age and individuality working against him in his later years. While many of his submissions were rejected, Hine kept at it, still using his art to raise questions and fight for social reform. In 1939, a year before his death, Hine found renewed respect for his social photography with a large exhibition of his work at the Riverside Museum in New York and in the 1980s the NCLC created the Lewis Hine Award to honor the investigative photographer. Still today the award is given annually to ten recipients for their extraordinary service to young people.

Today Hine’s work, a collection of more than 5,100 photographs and 355 glass negatives, are housed in the Library of Congress. Hine’s photographs were instrumental for the state of American workers and American children, ultimately helping to reform the child labor laws in the U.S. His use of free speech and free press influenced and awakened Americans’ consciences, effectively proving that the camera can be a powerful tool to promote social change.

Hine’s photographs were instrumental for the state of American workers and American children, ultimately helping to reform the child labor laws in the U.S. His use of free speech and free press influenced and awakened Americans’ consciences, effectively proving that the camera can be a powerful tool to promote social change.

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel – and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way.

That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Epic Trips, Mini Trips and Sailing Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travellers and friends who want to explore the world together.

That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Epic Trips, Mini Trips and Sailing Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travellers and friends who want to explore the world together.Epic Trips are deeply immersive 8 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and enough down time to really relax and soak it all in. Our Mini Trips are small and mighty - they squeeze all the excitement and authenticity of our longer Epic Trips into a manageable 3-5 day window. Our Sailing Trips invite you to spend a week experiencing the best of the sea and land in the Caribbean and the Mediterranean.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm – and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet.

That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.The Photographer Who Fought to End Child Labor

From the moment I first saw her portrait, I was captivated by Millie Cornaro—bonnet strings dangling, busy hands held together, that impish smile.

Get Inspired Enjoy stories about art, and news about Getty exhibitions and events, with our free e-newsletter Subscribe nowHer expression is one that I see on my students’ faces, on my own children’s faces. They look up from their work, ready for play, for a laugh, checking to see if you’ll join in or steer them back to the task at hand. Ten-year-old Millie’s task had nothing to do with classwork; she picked cranberries.

Cranberry Picker, New Jersey, 1913, Lewis Hine. Gelatin silver print, 15 × 12 3/16 in. Getty Museum, 84.XM.221.12

Day in and day out, until the job was done, and her family moved on to the next harvest. It didn’t matter that Millie and many children like her missed weeks, even months of school. In this photograph, taken by Lewis Hine on September 28, 1910, a sparkle of Millie's personality shines through, despite the physical discomfort and tedium of the job. It is this persistence of the “human spirit,” as Hine called it, that “is the big thing after all.” Hine's ability to show that spirit while revealing the terrible nature of child labor is what drew me to him as a photographer.

It didn’t matter that Millie and many children like her missed weeks, even months of school. In this photograph, taken by Lewis Hine on September 28, 1910, a sparkle of Millie's personality shines through, despite the physical discomfort and tedium of the job. It is this persistence of the “human spirit,” as Hine called it, that “is the big thing after all.” Hine's ability to show that spirit while revealing the terrible nature of child labor is what drew me to him as a photographer.

Lewis Hine and his advocacy for working kids are the subjects of my new picture book, The Traveling Camera: Lewis Hine and the Fight to End Child Labor, illustrated by Michael Garland and published by Getty Publications. Hine took photographs for the National Child Labor Committee from 1906 to 1918, documenting the large numbers of young people in the labor force and the harsh conditions under which they worked. His pictures attracted national attention and assisted in the passage of child labor laws.

Sadie Pfeiffer, Spinner in Cotton Mill, negative 1908; print about 1920s–1930s, Lewis Hine. Gelatin silver print, 11 × 14 1/16 in. Getty Museum, 84.XM.967.15

It’s hard to find children in the historical record, let alone poor, working-class, minority, or immigrant children. Hine, though, took thousands of photographs of kids, catching moments like the one he shared with Millie: eye-to-eye, mid-exchange, mid-task. And he went to great lengths to do it, traveling around the country and using disguises to sneak into some work sites.

When children read The Traveling Camera, they visit textile mills and coal mines, and they meet Millie and other children who are based on real kids that Hine photographed. Readers also get to know Hine himself, not only through Michael Garland's wonderful illustrations but from direct quotations.

Hine had a poetic voice and a great sense of humor, and his students at the Ethical Culture School in New York City—where he taught before becoming a full-time photographer—thought he was an excellent actor. About his decision to leave teaching, he said, “I was merely changing the educational efforts from the classroom to the world.”

About his decision to leave teaching, he said, “I was merely changing the educational efforts from the classroom to the world.”

Lewis Hine illustration from The Traveling Camera: Lewis Hine and the Fight to End Child Labor © 2021 J. Paul Getty Trust / Text © Alexandra S. D. Hinrichs / Illustrations © Michael Garland

I decided to write the story in first person from Hine’s perspective, and in free verse, which seemed like an obvious choice given the lyrical language Hine used in his articles and letters. As children and the adults who read with them enjoy hearing poetry and exploring the beautiful and detailed illustrations, they can find their way into many different conversations.

Some topics are obvious: the differences between the lives of the children depicted in the story and those of young readers now, how child labor laws have improved, but also the continued existence of child labor today. When I visit classrooms, we talk about how we have each likely eaten something produced, in part, with child labor, especially if it contains chocolate or palm oil. We talk about why 2021 was proclaimed by the United Nations the year to end child labor, and why the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in child labor.

We talk about why 2021 was proclaimed by the United Nations the year to end child labor, and why the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in child labor.

Some topics are natural extensions, such as the power of art to help achieve social justice and the responsibility that comes with taking pictures. And we imagine putting ourselves in another’s shoes, be that today or at another time. After all, that’s the gift of reading.

The Traveling Camera

Lewis Hine and the Fight to End Child Labor

$17.99/£13.99

Learn more about this publication

90,000 CHILD LABOR IN THE USA - For our Soviet Motherland! — LiveJournal ?-

- Children's work in the USA

-

005

Lewis Hine is an American photographer who turned the US government's attitude towards child labor upside down with his photographs.

He was the pioneer and godfather of social photography. In his youth, for some time, Lewis himself worked in a furniture factory, studied at the universities of Chicago, New York and Columbia. In 1903, while taking a course in botany and natural studies in New York, Lewis was given a camera to use in recording the learning process and student activities. At 1905 Hine comes to an inner need to create a series of documentary works, the theme of which was the immigrants to Ellis Island. In 1908, he accepted an offer from the National Child Labor Committee to become their staff photographer. For eight years, Lewis Hine travels around America and records violations of labor laws in relation to children. He visits plants and factories, takes notes on working conditions, writes down the names of children and their ages, and if he succeeded, he recorded all these violations with a camera.

He was the pioneer and godfather of social photography. In his youth, for some time, Lewis himself worked in a furniture factory, studied at the universities of Chicago, New York and Columbia. In 1903, while taking a course in botany and natural studies in New York, Lewis was given a camera to use in recording the learning process and student activities. At 1905 Hine comes to an inner need to create a series of documentary works, the theme of which was the immigrants to Ellis Island. In 1908, he accepted an offer from the National Child Labor Committee to become their staff photographer. For eight years, Lewis Hine travels around America and records violations of labor laws in relation to children. He visits plants and factories, takes notes on working conditions, writes down the names of children and their ages, and if he succeeded, he recorded all these violations with a camera.

Hein's photographs from this expedition have been used to illustrate lectures, magazine articles and exhibitions.

The photographs he took and the so-called field notes helped the National Committee on Child Labor to prove the existing plight of children and the impossible conditions for their work. During and after World War I, Lewis Hine focused on photographic work of the American Red Cross and their relief work in Europe.

The photographs he took and the so-called field notes helped the National Committee on Child Labor to prove the existing plight of children and the impossible conditions for their work. During and after World War I, Lewis Hine focused on photographic work of the American Red Cross and their relief work in Europe. [ Spoiler (click to open) ]

In the 1920s and early 1930s, Hine made a series of "worker portraits" that emphasized the human contribution to modern industry. In 1930 Hine photographed the construction of the Empire State Building. He worked in dangerous areas of an unfinished skyscraper, taking on all the hardships and risks of the builders of the building. In order to get better compositional photographs, Hine photographed in a specially designed basket that was hung over 1,000 feet above Fifth Avenue. In his works, Hine always sought to show the dignity of labor and the dignity of a working, working person. He said that these people are like the heroes of their time and the country should know them by sight.

Lewis Hine entered the history of photography as a person who formed a new type of fine photographic art, this is documentary and social photography. Hine was recognized during his lifetime, he worked all over America, wasting no time in order to leave in history the types of people who worked, worked and built their country. He is called the timeless humanist of art. His photographs are honest, humane and correct. The uniquely crafted composition, with exactly the “same” arrangement of people, light and form solutions, give us the opportunity to see and feel the entire emotional palette that the American working people experienced in the period before the Great Depression.

Lewis Hine | Perpendicular World

Skip to main contentTags

Children

Art

Body

Lewis Hine

Photography as a tool to combat child labor

This girl worked in a textile factory in Lincolnton, North Carolina. She said she was 10 years old. Nov. 1908

She said she was 10 years old. Nov. 1908 To many modern Westerners, child labor seems cruel and uncivilized. However, in all pre-industrial societies there was no definite boundary between childhood and adulthood, and children worked in the same way as adults, it was part of their education.

In Europe during the Middle Ages, childhood, as we now imagine it, lasted only a few years. At about 7 years old, a peasant child began working on a farm, while urban children were sent to learn some craft as apprentices. There was no such thing as adolescence. A person was recognized as an adult, with all the rights and obligations at the age of 13 - 15 years.

Of course, there were schools, but the school day was incomplete and there could be students of different ages in the same class. Printing did not exist then, and paper was expensive, so the students did not have any teaching aids or the opportunity to take notes during the lessons. The students simply listened to the teacher, who gave the same lectures year after year. In the class, both beginners and regular students were on the same bench.

In the class, both beginners and regular students were on the same bench.

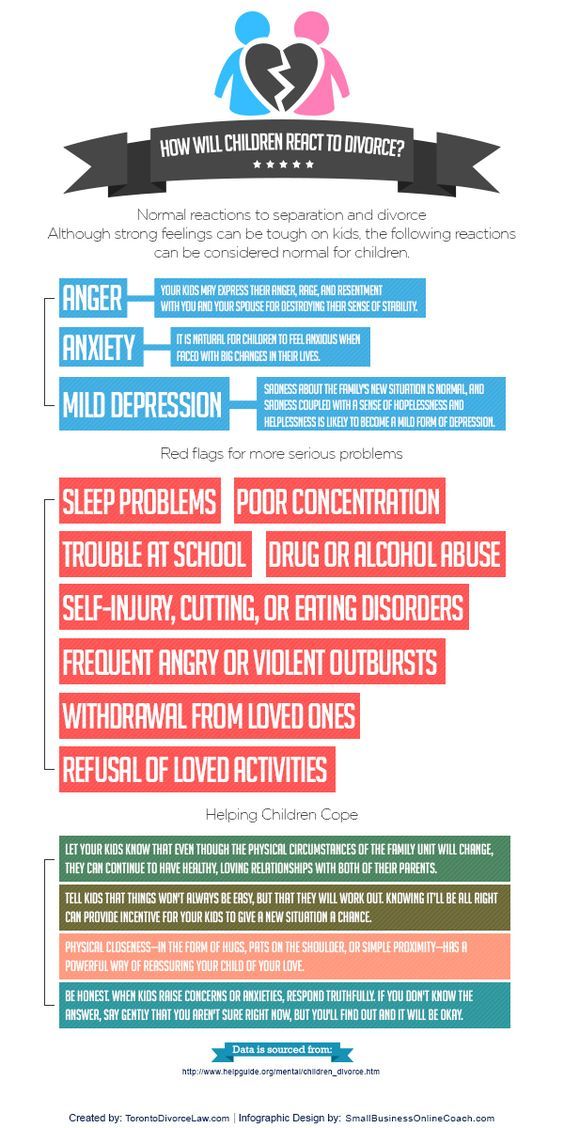

In the United States after the Civil War (1861-1865), rapid industrialization led to increased child labor and new jobs for children. According to the 1870 national census, about one in eight children in the United States worked. By 1900, about 1,750,000 children were working, or one in six. Sixty percent of them were agricultural workers, the remaining 40 percent worked in industry. More than half of the working children were from immigrant families.” At the same time, in pre-industrial and rural Canada, children were needed for the work of their families. Immigrant children in Canada worked as farm laborers and domestic workers.” Old stereotypes persisted that child labor was segregated by gender. The boys worked in sawmills and coal mines, the girls worked in the textile and clothing industry.”

At the end of the 19th century, opposition to the use of child labor intensified. At that time, child labor was still considered economically viable and ethically acceptable, but as industrialization progressed, it was increasingly perceived as uncivilized. However, many working-class parents saw little benefit in sending their children to school instead of work.

However, many working-class parents saw little benefit in sending their children to school instead of work.

It is commonly believed that laws restricting or prohibiting child labor, like the 8-hour workday, are the result of union struggles. However, the first to fight against child labor were mainly philanthropists from the upper and middle classes, clergymen and politicians.

The crusade against child labor unfolded in most Western countries at the end of the nineteenth century. The social fabric of the time called for action against "social evils" and the adoption of child labor laws. However, child labor laws were unlikely to be effective as they did not actually operate. Compulsory school laws have been more effective, and the child labor debate has been more educational. Governments, educators, politicians and philanthropists have joined in the effort to move children from factories to schools.

Although agriculture accounted for 60 percent of child labour, this campaign strangely bypassed it. Although the use of child labor in industry seemed cruel to children, at the same time, the work of children in agriculture was considered in keeping with American traditions. It was believed that the work of children in agriculture was safer for their health, although this argument did not stand up to scrutiny.

Although the use of child labor in industry seemed cruel to children, at the same time, the work of children in agriculture was considered in keeping with American traditions. It was believed that the work of children in agriculture was safer for their health, although this argument did not stand up to scrutiny.

What were the working conditions of children working in industry compared to agriculture? Research shows that in France, industrialization made the work of some children more difficult, as the working day in factories was longer and more structured. On the other hand, rural life in late nineteenth-century France was harsh and primitive. In addition, young men from rural areas were more likely to be recruited into the military than young men from urban areas, which contributed to child labor in agriculture.

However, in my opinion, such double standards are more of a moralistic nature. The bourgeois philanthropists of that time were afraid of delinquency in the cities, especially among the urban working youth, and therefore set about "rescuing" working children from exploitation.

In the United States, the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) was formed in 1904 through the efforts of politicians, philanthropists, and clergy, in particular the Reverend Edgar Gardner Murphy of the Episcopal Church. The photographs of the sociologist and photographer Lewis Weekes Hine (September 26, 1874 - November 3, 1940 d.)

The committee helped organize local committees in every state where child labor was used, held traveling exhibitions, and was the first organized reform movement to make extensive use of photo propaganda. In 1915, the Committee published 416 newspapers and distributed more than four million propaganda leaflets. The advocacy contributed to changing attitudes regarding the use of child labor. Photographer Lewis Hine was one of the NCLC activists. In 1908 Hine left his job as a teacher and devoted his entire career to photography and working as a reporter for the NCLC.

Over the years, Hine photographed thousands of children and teenagers working for money. For each photo, he added information about the location of the shooting, sometimes the age of the children and added comments. Currently, these photos are widely disseminated on the Internet.

For each photo, he added information about the location of the shooting, sometimes the age of the children and added comments. Currently, these photos are widely disseminated on the Internet.

Campaigns like the NCLC campaign have succeeded in moving children from factories to schools. The increase in school attendance by children has been one of the factors in reducing the use of child labor.

Studies in Sweden, Denmark and Chicago show that the adoption of compulsory school laws was one of the measures to combat the exploitation of child labor. 1880 to 19In 2014 in Norway, the number of school days increased by 50 percent, which also contributed to a reduction in the use of child labor, since at that time most children worked for money during their non-school hours.

However, it is worth noting that in Western countries compulsory schooling was introduced not only in order to combat the exploitation of child labor. Some countries introduced compulsory schooling long before industrialization.