Early pre eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia - NHS

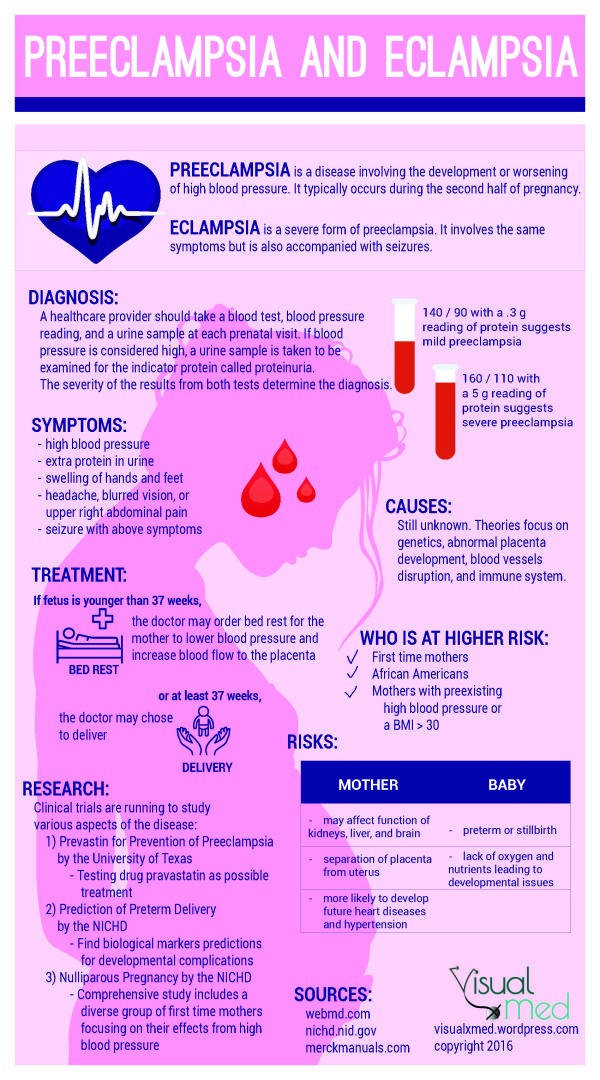

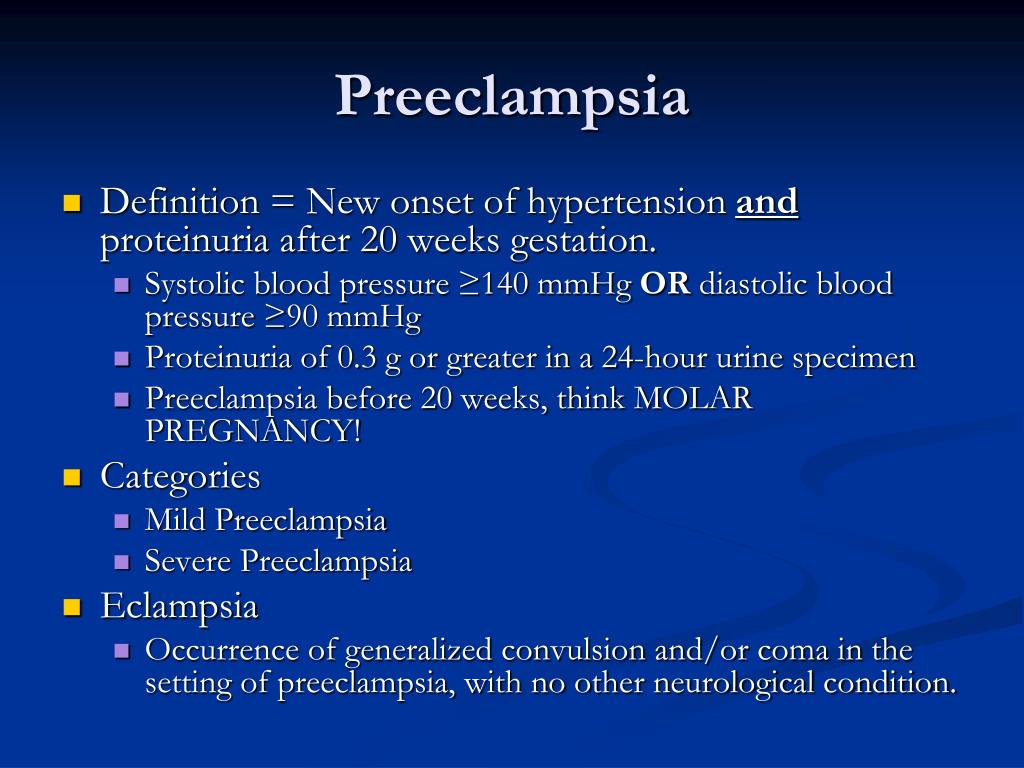

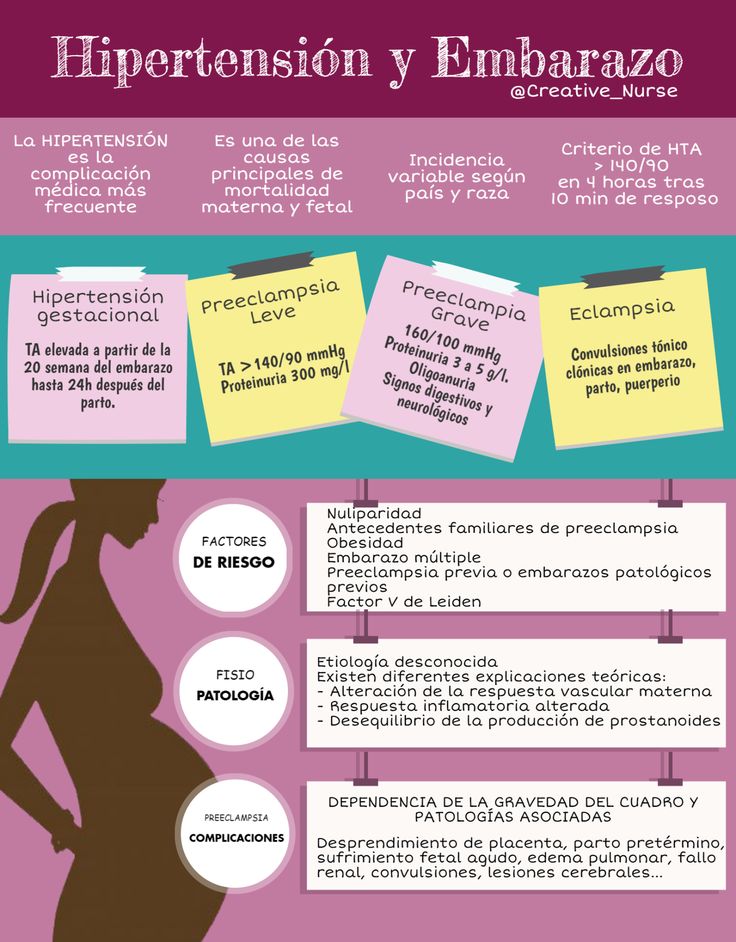

Pre-eclampsia is a condition that affects some pregnant women, usually during the second half of pregnancy (from 20 weeks) or soon after their baby is delivered.

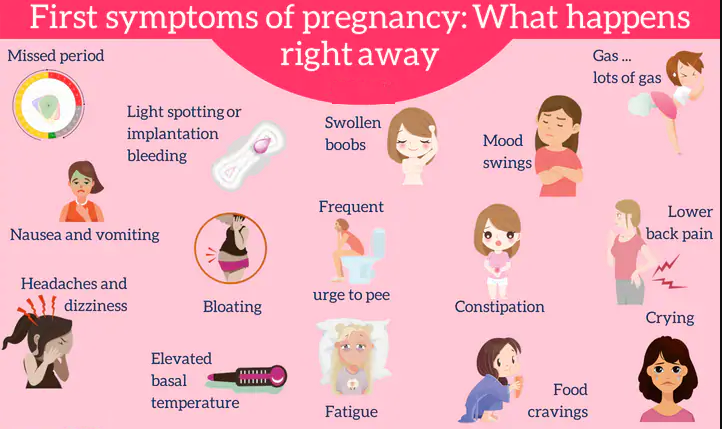

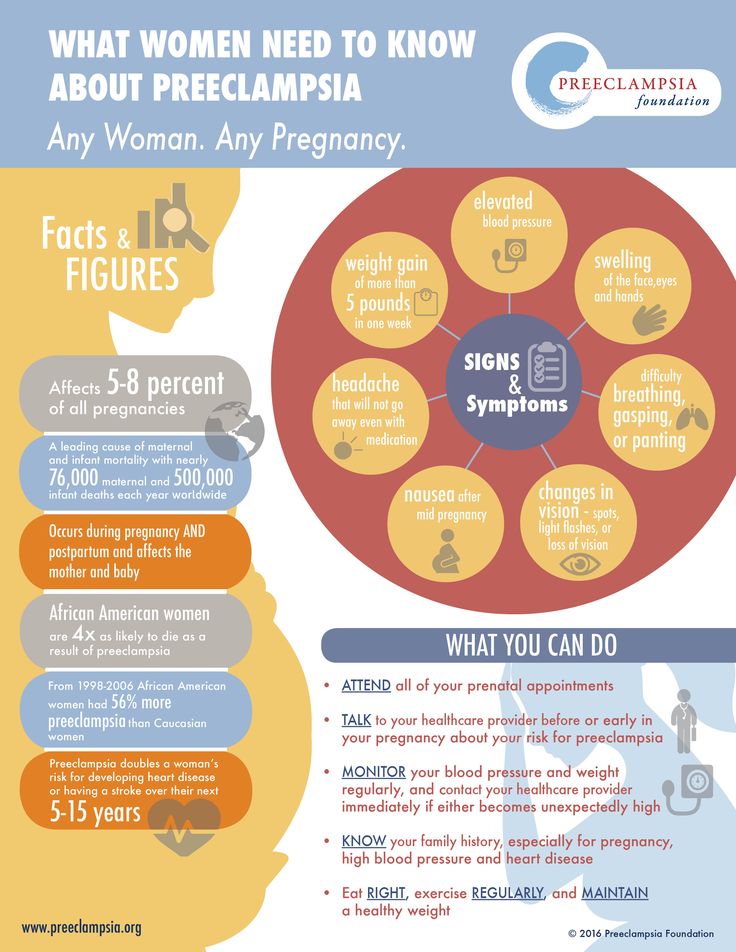

Symptoms of pre-eclampsia

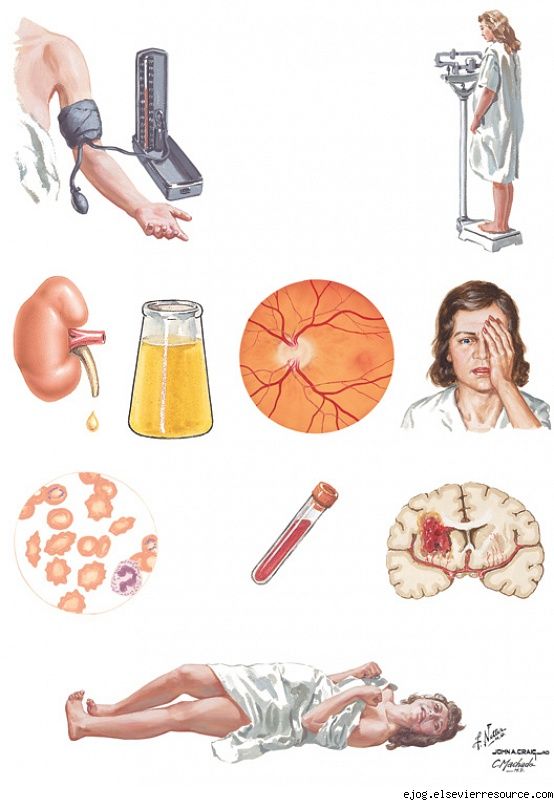

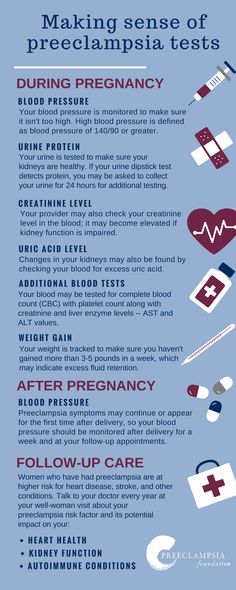

Early signs of pre-eclampsia include having high blood pressure (hypertension) and protein in your urine (proteinuria).

It's unlikely that you'll notice these signs, but they should be picked up during your routine antenatal appointments.

In some cases, further symptoms can develop, including:

- severe headache

- vision problems, such as blurring or flashing

- pain just below the ribs

- vomiting

- sudden swelling of the face, hands or feet

If you notice any symptoms of pre-eclampsia, seek medical advice immediately by calling your midwife, GP surgery or NHS 111.

Although many cases are mild, the condition can lead to serious complications for both mother and baby if it's not monitored and treated.

The earlier pre-eclampsia is diagnosed and monitored, the better the outlook for mother and baby.

Video: what is pre-eclampsia and what are the warning signs?

In this video, a midwife explains the warning signs of pre-eclampsia.

Media last reviewed: 1 September 2020

Media review due: 1 September 2023

Who's affected?

There are a number of things that can increase your chances of developing pre-eclampsia, such as:

- having diabetes, high blood pressure or kidney disease before you were pregnant

- having an autoimmune condition, such as lupus or antiphospholipid syndrome

- having high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia in a previous pregnancy

Other things that can slightly increase your chances of developing pre-eclampsia include:

- a family history of pre-eclampsia

- being 40 years old or more

- it's more than 10 years since your last pregnancy

- expecting multiple babies (twins or triplets)

- having a body mass index (BMI) of 35 or more

If you have 2 or more of these together, your chances are higher.

If you're thought to be at a high risk of developing pre-eclampsia, you may be advised to take a 75 to 150mg daily dose of aspirin from the 12th week of pregnancy until your baby is born.

What causes pre-eclampsia?

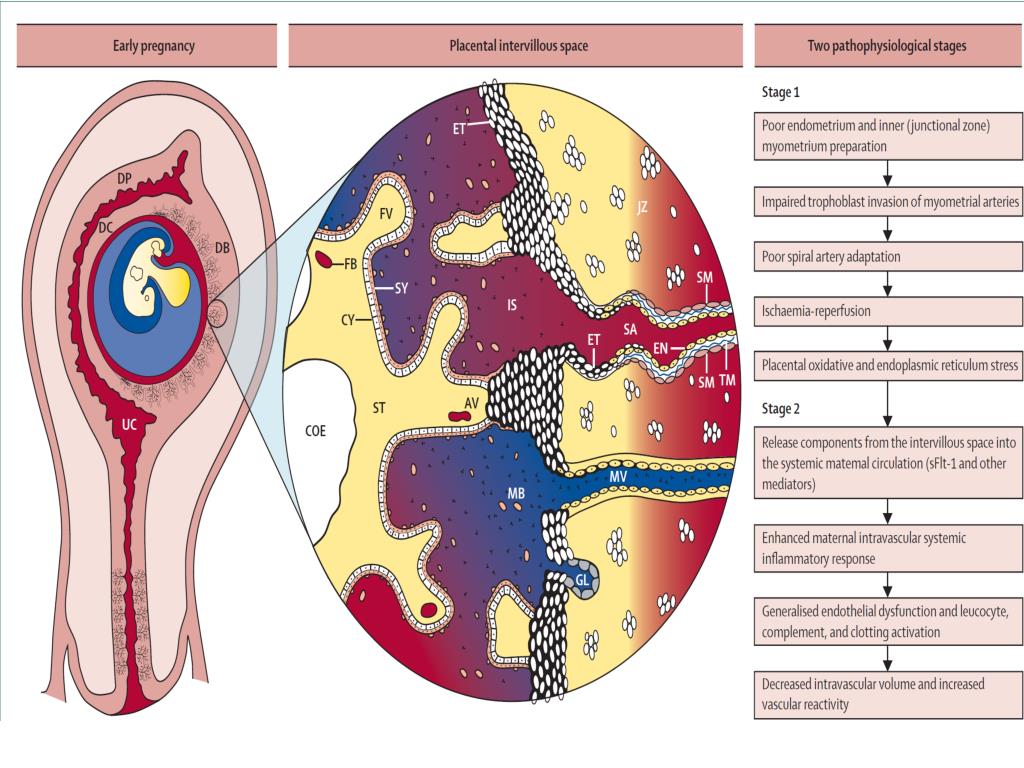

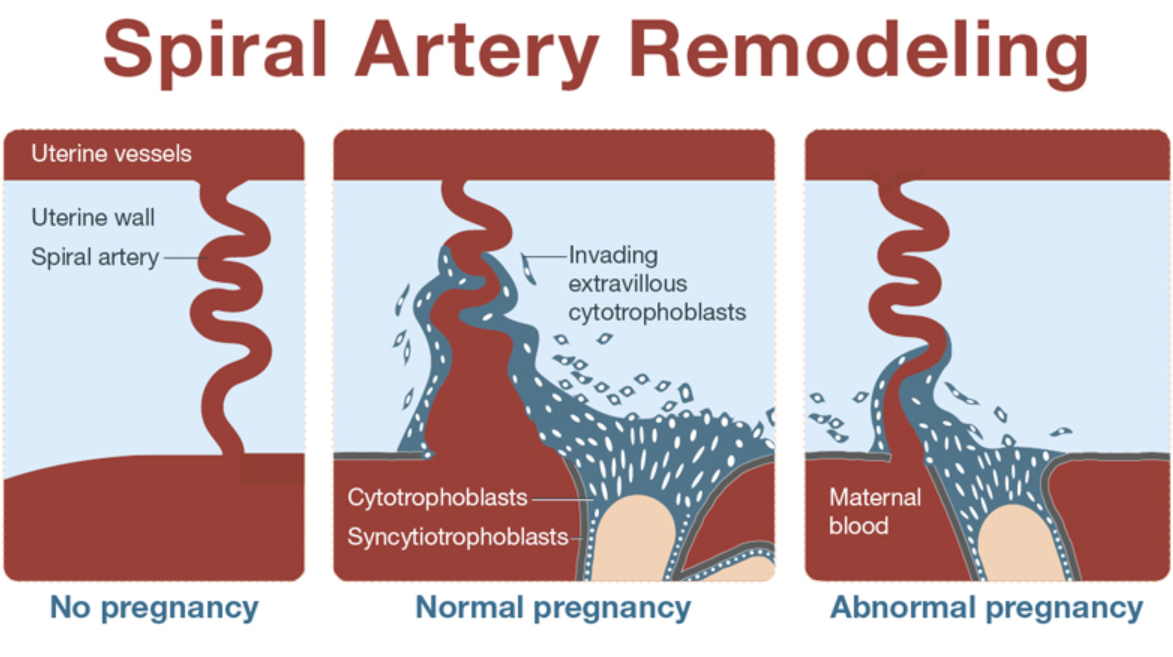

Although the exact cause of pre-eclampsia is not known, it's thought to occur when there's a problem with the placenta, the organ that links the baby's blood supply to the mother's.

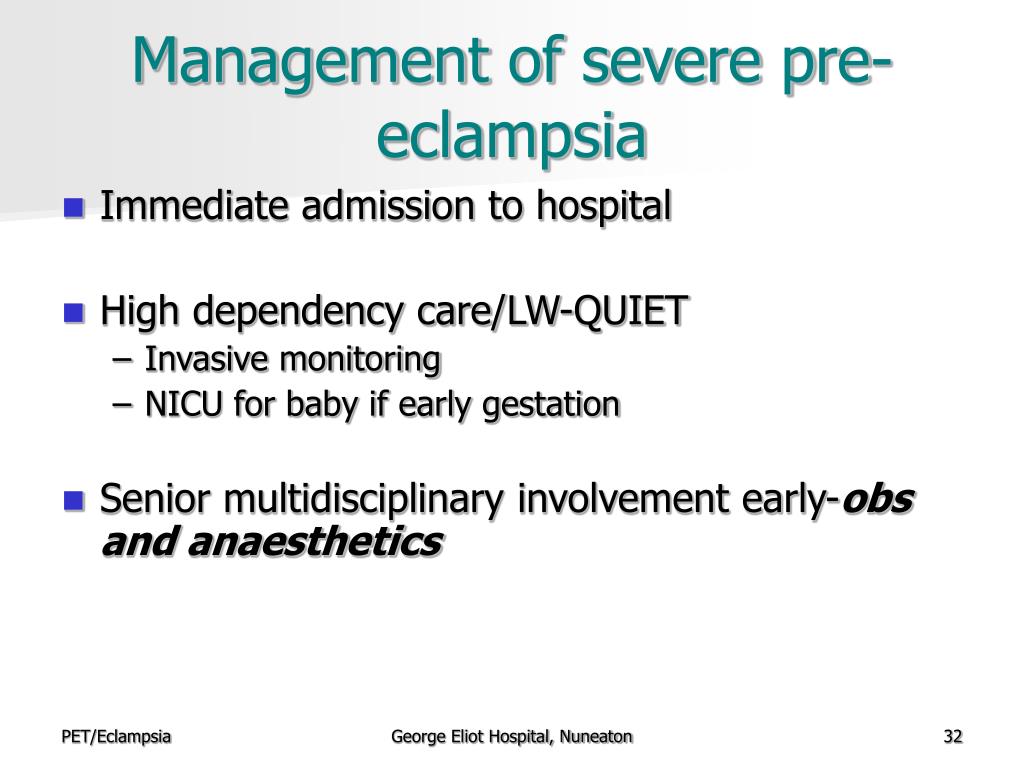

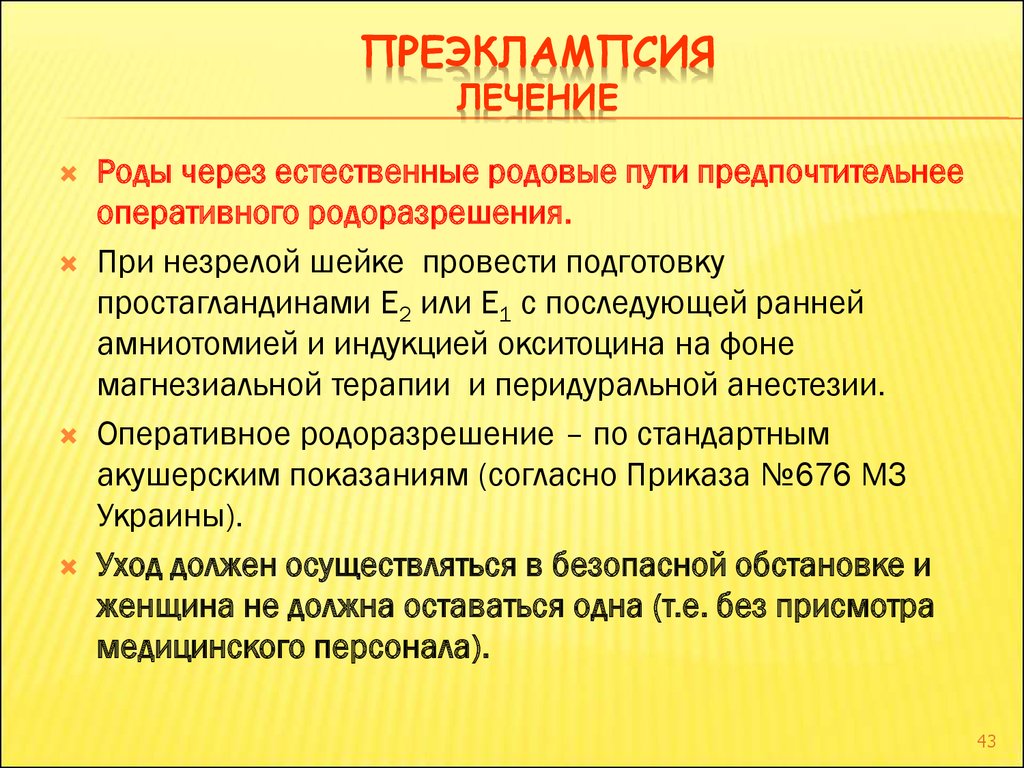

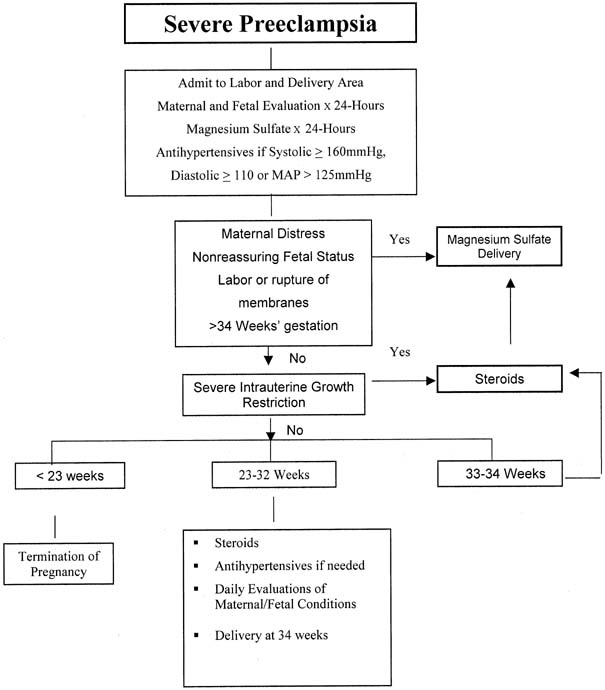

Treating pre-eclampsia

If you're diagnosed with pre-eclampsia, you should be referred for an assessment by a specialist, usually in hospital.

While in hospital, you'll be monitored closely to determine how severe the condition is and whether a hospital stay is needed.

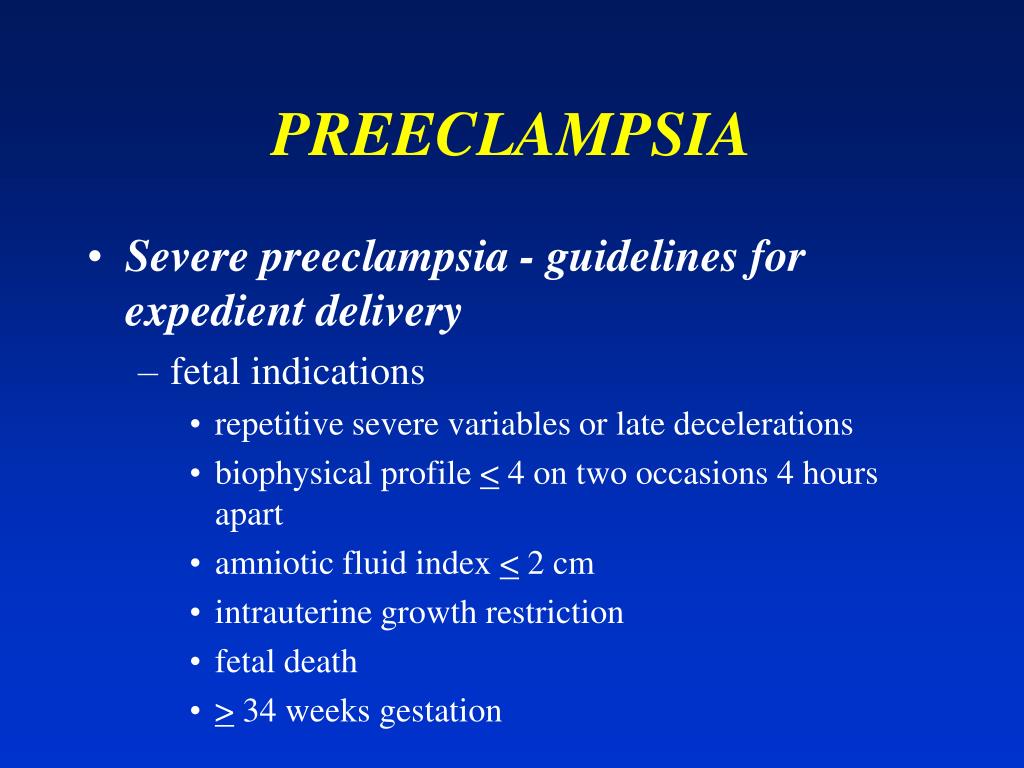

The only way to cure pre-eclampsia is to deliver the baby, so you'll usually be monitored regularly until it's possible for your baby to be delivered.

This will normally be at around 37 to 38 weeks of pregnancy, but it may be earlier in more severe cases.

At this point, labour may be started artificially (induced) or you may have a caesarean section.

You'll be offered medicine to lower your blood pressure while you wait for your baby to be delivered.

Complications

Although most cases of pre-eclampsia cause no problems and improve soon after the baby is delivered, there's a risk of serious complications that can affect both the mother and her baby.

There's a risk that the mother will develop fits called "eclampsia". These fits can be life threatening for the mother and baby, but they're rare.

Page last reviewed: 28 September 2021

Next review due: 28 September 2024

Preeclampsia - Symptoms and causes

Overview

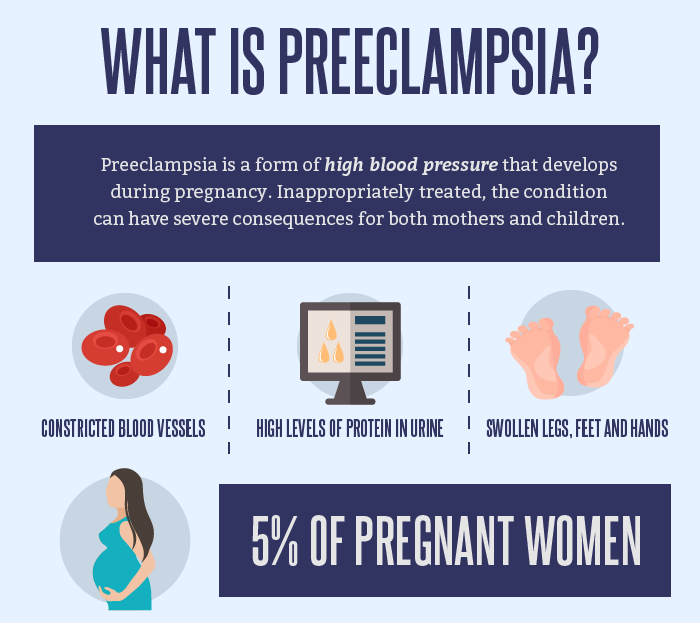

Preeclampsia is a complication of pregnancy. With preeclampsia, you might have high blood pressure, high levels of protein in urine that indicate kidney damage (proteinuria), or other signs of organ damage. Preeclampsia usually begins after 20 weeks of pregnancy in women whose blood pressure had previously been in the standard range.

With preeclampsia, you might have high blood pressure, high levels of protein in urine that indicate kidney damage (proteinuria), or other signs of organ damage. Preeclampsia usually begins after 20 weeks of pregnancy in women whose blood pressure had previously been in the standard range.

Left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious — even fatal — complications for both the mother and baby.

Early delivery of the baby is often recommended. The timing of delivery depends on how severe the preeclampsia is and how many weeks pregnant you are. Before delivery, preeclampsia treatment includes careful monitoring and medications to lower blood pressure and manage complications.

Preeclampsia may develop after delivery of a baby, a condition known as postpartum preeclampsia.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

Symptoms

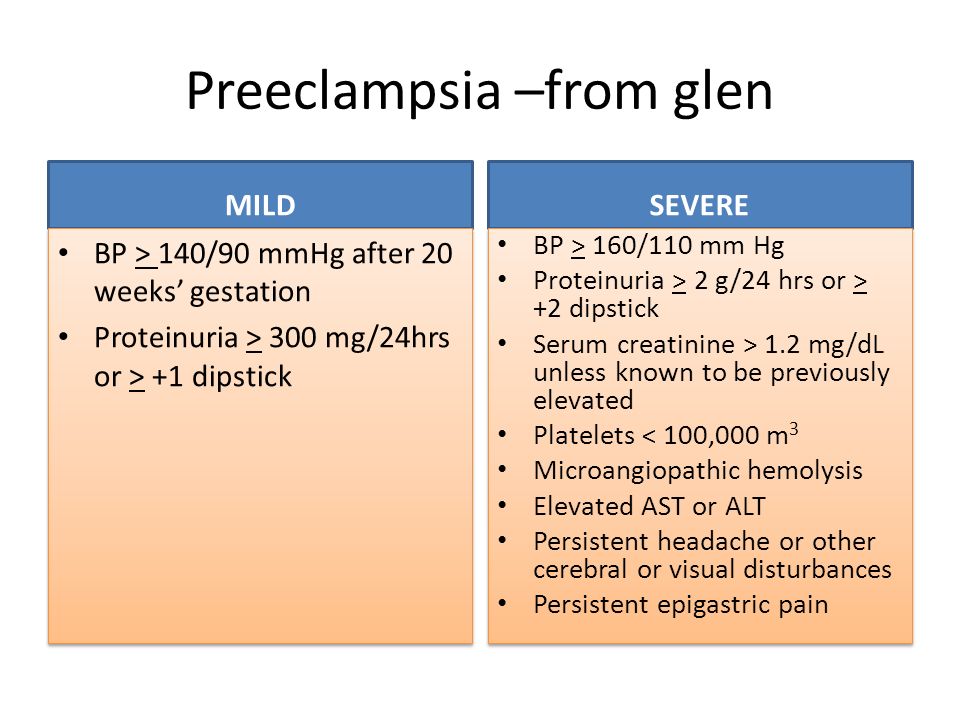

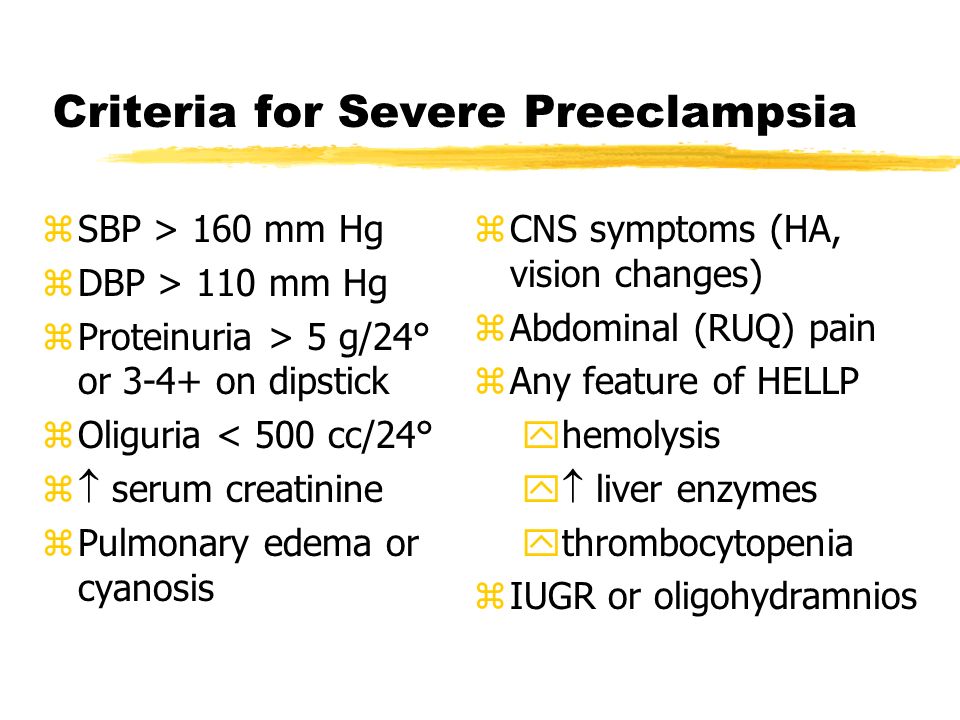

The defining feature of preeclampsia is high blood pressure, proteinuria, or other signs of damage to the kidneys or other organs. You may have no noticeable symptoms. The first signs of preeclampsia are often detected during routine prenatal visits with a health care provider.

You may have no noticeable symptoms. The first signs of preeclampsia are often detected during routine prenatal visits with a health care provider.

Along with high blood pressure, preeclampsia signs and symptoms may include:

- Excess protein in urine (proteinuria) or other signs of kidney problems

- Decreased levels of platelets in blood (thrombocytopenia)

- Increased liver enzymes that indicate liver problems

- Severe headaches

- Changes in vision, including temporary loss of vision, blurred vision or light sensitivity

- Shortness of breath, caused by fluid in the lungs

- Pain in the upper belly, usually under the ribs on the right side

- Nausea or vomiting

Weight gain and swelling (edema) are typical during healthy pregnancies. However, sudden weight gain or a sudden appearance of edema — particularly in your face and hands — may be a sign of preeclampsia.

When to see a doctor

Make sure you attend your prenatal visits so that your health care provider can monitor your blood pressure. Contact your provider immediately or go to an emergency room if you have severe headaches, blurred vision or other visual disturbances, severe belly pain, or severe shortness of breath.

Contact your provider immediately or go to an emergency room if you have severe headaches, blurred vision or other visual disturbances, severe belly pain, or severe shortness of breath.

Because headaches, nausea, and aches and pains are common pregnancy complaints, it's difficult to know when new symptoms are simply part of being pregnant and when they may indicate a serious problem — especially if it's your first pregnancy. If you're concerned about your symptoms, contact your doctor.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Causes

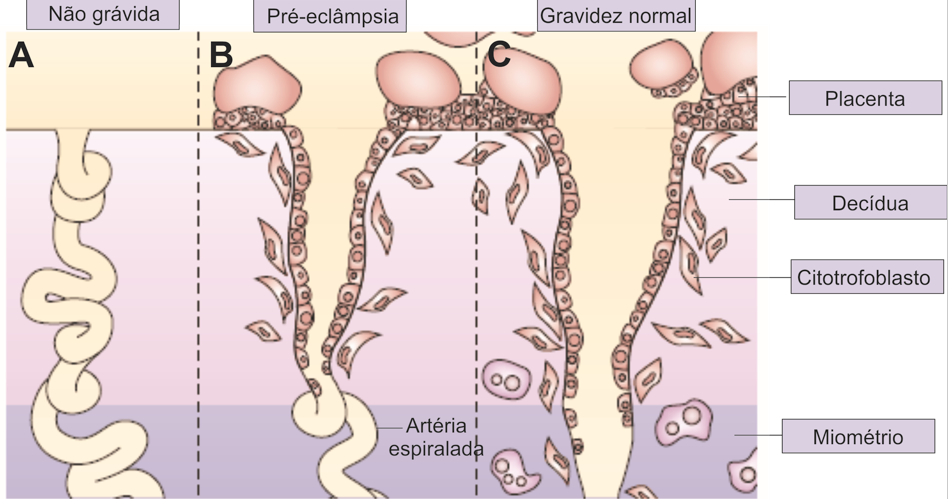

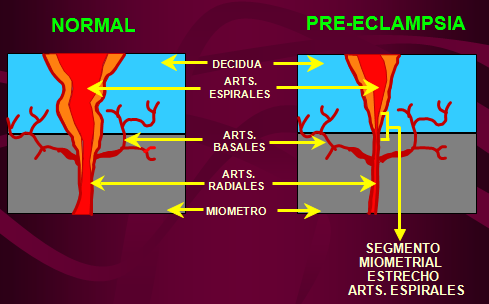

The exact cause of preeclampsia likely involves several factors. Experts believe it begins in the placenta — the organ that nourishes the fetus throughout pregnancy. Early in a pregnancy, new blood vessels develop and evolve to supply oxygen and nutrients to the placenta.

In women with preeclampsia, these blood vessels don't seem to develop or work properly. Problems with how well blood circulates in the placenta may lead to the irregular regulation of blood pressure in the mother.

Problems with how well blood circulates in the placenta may lead to the irregular regulation of blood pressure in the mother.

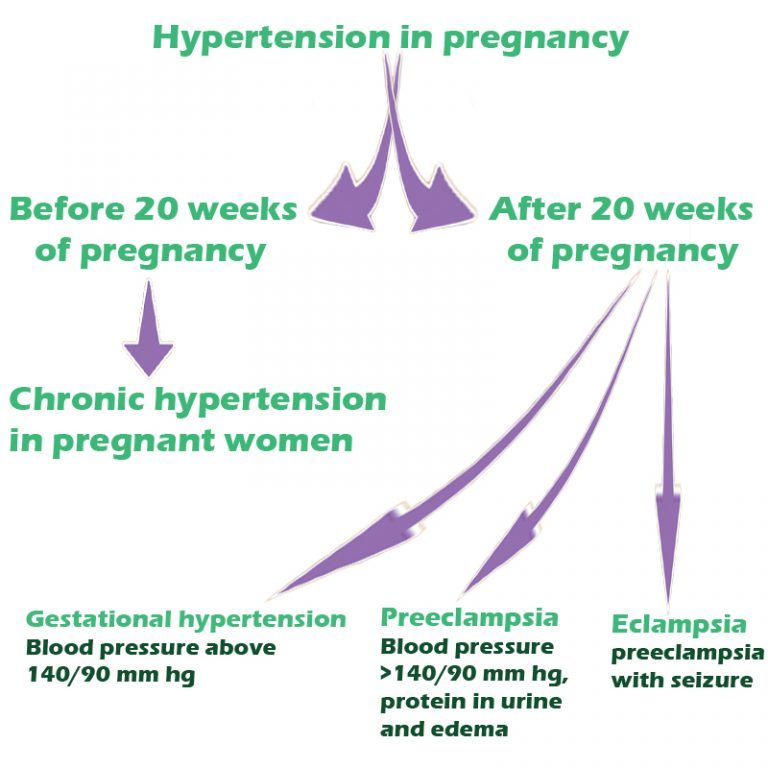

Other high blood pressure disorders during pregnancy

Preeclampsia is one high blood pressure (hypertension) disorder that can occur during pregnancy. Other disorders can happen, too:

- Gestational hypertension is high blood pressure that begins after 20 weeks without problems in the kidneys or other organs. Some women with gestational hypertension may develop preeclampsia.

- Chronic hypertension is high blood pressure that was present before pregnancy or that occurs before 20 weeks of pregnancy. High blood pressure that continues more than three months after a pregnancy also is called chronic hypertension.

- Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia occurs in women diagnosed with chronic high blood pressure before pregnancy, who then develop worsening high blood pressure and protein in the urine or other health complications during pregnancy.

Risk factors

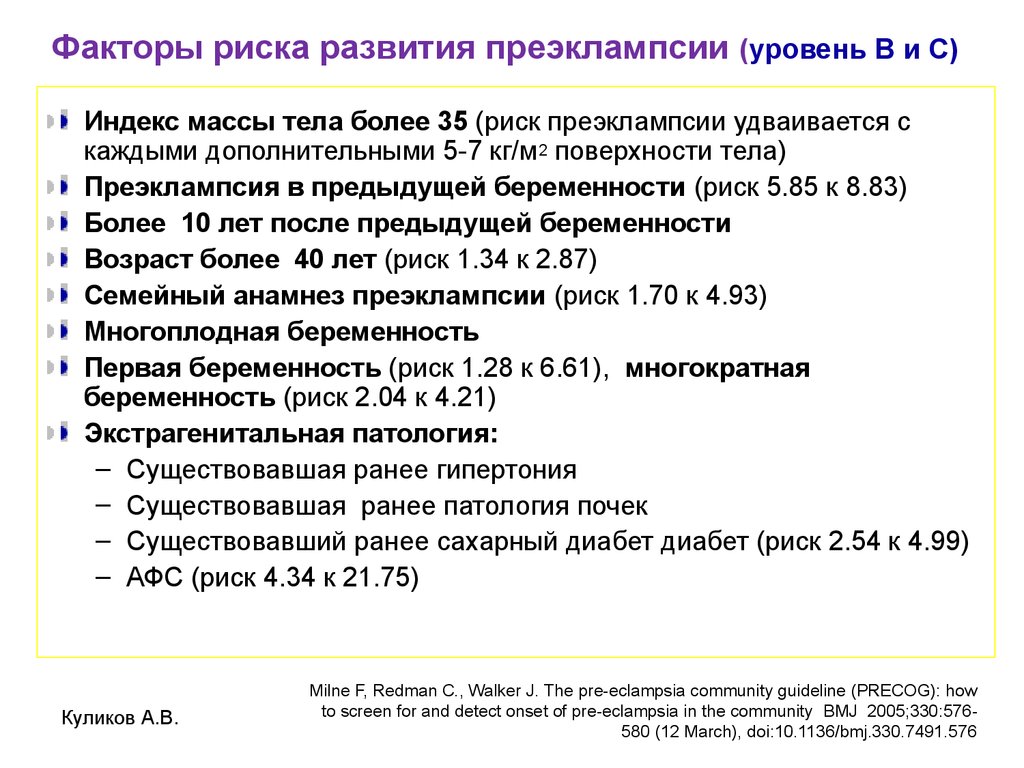

Conditions that are linked to a higher risk of preeclampsia include:

- Preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy

- Being pregnant with more than one baby

- Chronic high blood pressure (hypertension)

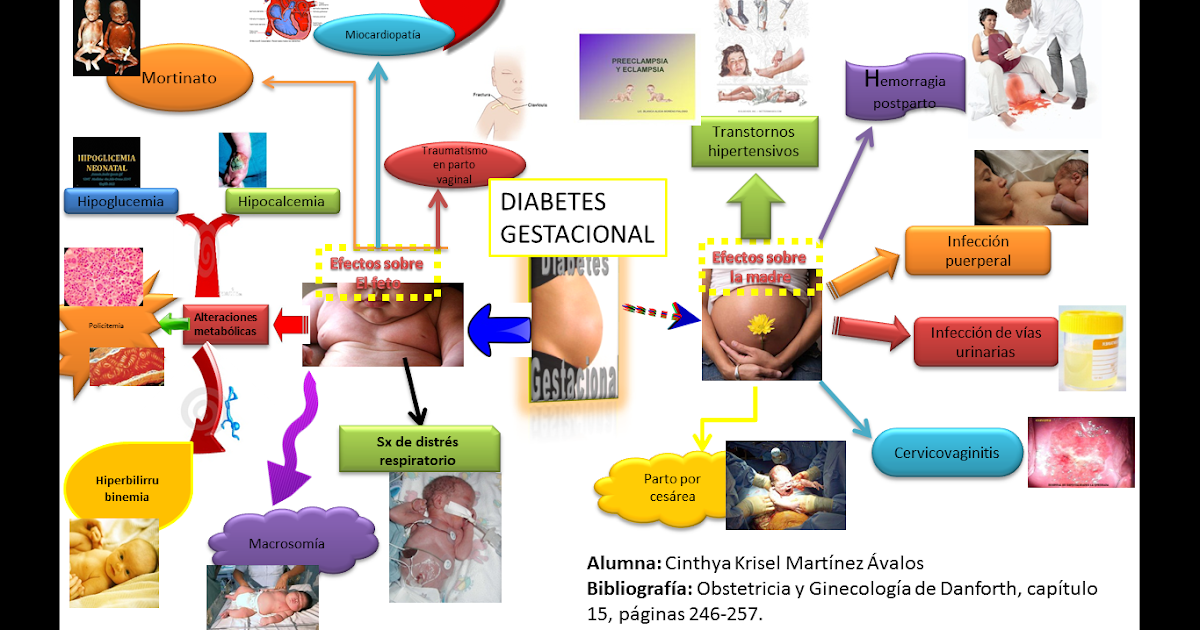

- Type 1 or type 2 diabetes before pregnancy

- Kidney disease

- Autoimmune disorders

- Use of in vitro fertilization

Conditions that are associated with a moderate risk of developing preeclampsia include:

- First pregnancy with current partner

- Obesity

- Family history of preeclampsia

- Maternal age of 35 or older

- Complications in a previous pregnancy

- More than 10 years since previous pregnancy

Other risk factors

Several studies have shown a greater risk of preeclampsia among Black women compared with other women. There's also some evidence of an increased risk among indigenous women in North America.

A growing body of evidence suggests that these differences in risk may not necessarily be based on biology. A greater risk may be related to inequities in access to prenatal care and health care in general, as well as social inequities and chronic stressors that affect health and well-being.

Lower income also is associated with a greater risk of preeclampsia likely because of access to health care and social factors affecting health.

For the purposes of making decisions about prevention strategies, a Black woman or a woman with a low income has a moderately increased risk of developing preeclampsia.

Complications

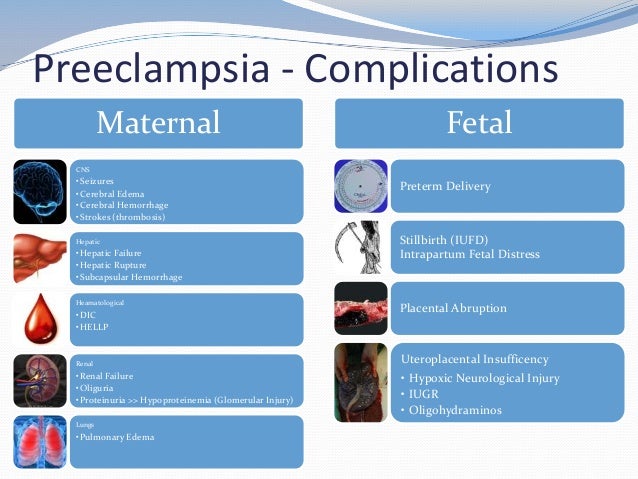

Complications of preeclampsia may include:

- Fetal growth restriction. Preeclampsia affects the arteries carrying blood to the placenta. If the placenta doesn't get enough blood, the baby may receive inadequate blood and oxygen and fewer nutrients. This can lead to slow growth known as fetal growth restriction.

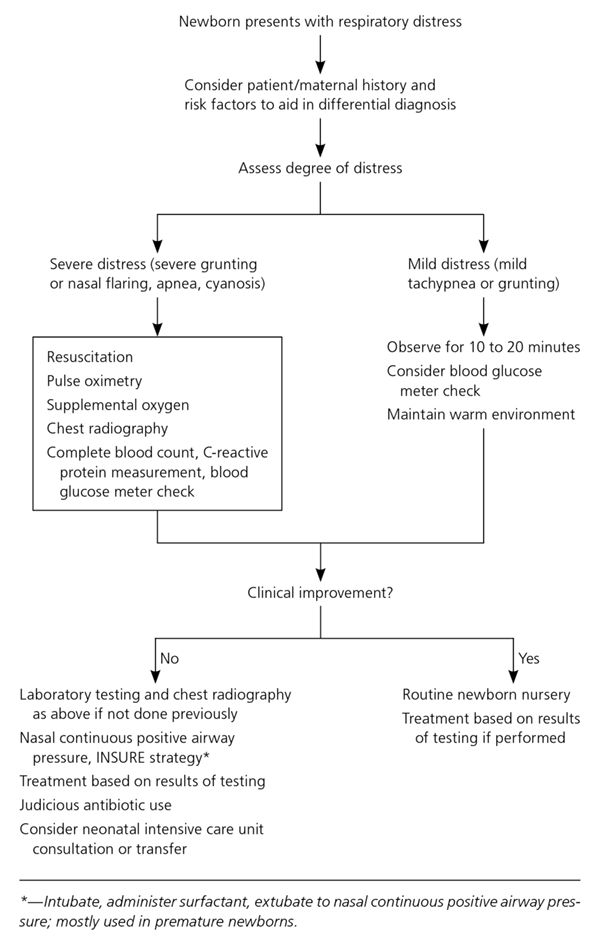

- Preterm birth.

Preeclampsia may lead to an unplanned preterm birth — delivery before 37 weeks. Also, planned preterm birth is a primary treatment for preeclampsia. A baby born prematurely has increased risk of breathing and feeding difficulties, vision or hearing problems, developmental delays, and cerebral palsy. Treatments before preterm delivery may decrease some risks.

Preeclampsia may lead to an unplanned preterm birth — delivery before 37 weeks. Also, planned preterm birth is a primary treatment for preeclampsia. A baby born prematurely has increased risk of breathing and feeding difficulties, vision or hearing problems, developmental delays, and cerebral palsy. Treatments before preterm delivery may decrease some risks. - Placental abruption. Preeclampsia increases your risk of placental abruption. With this condition, the placenta separates from the inner wall of the uterus before delivery. Severe abruption can cause heavy bleeding, which can be life-threatening for both the mother and baby.

-

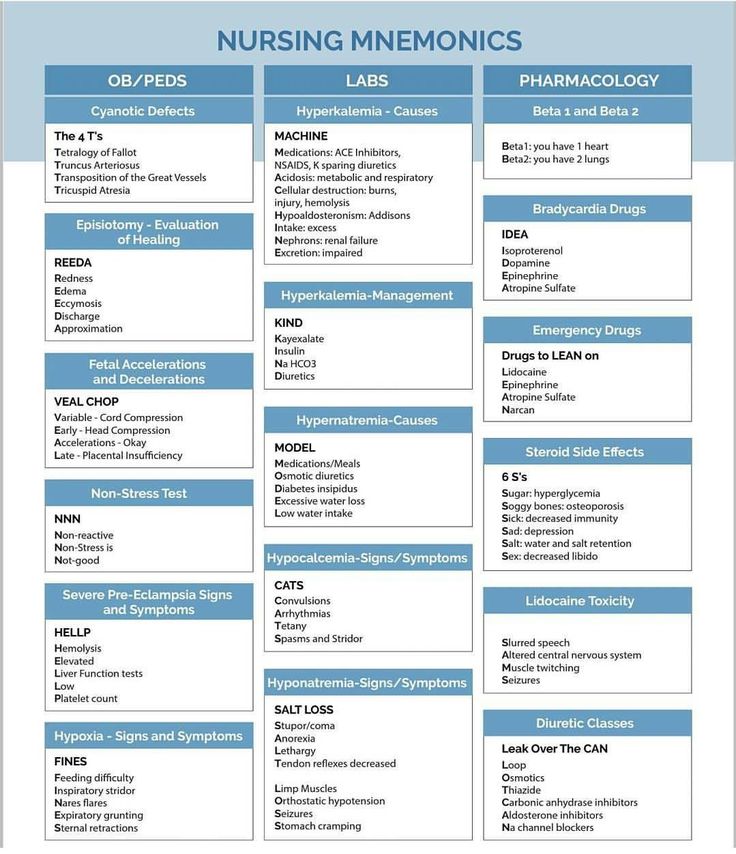

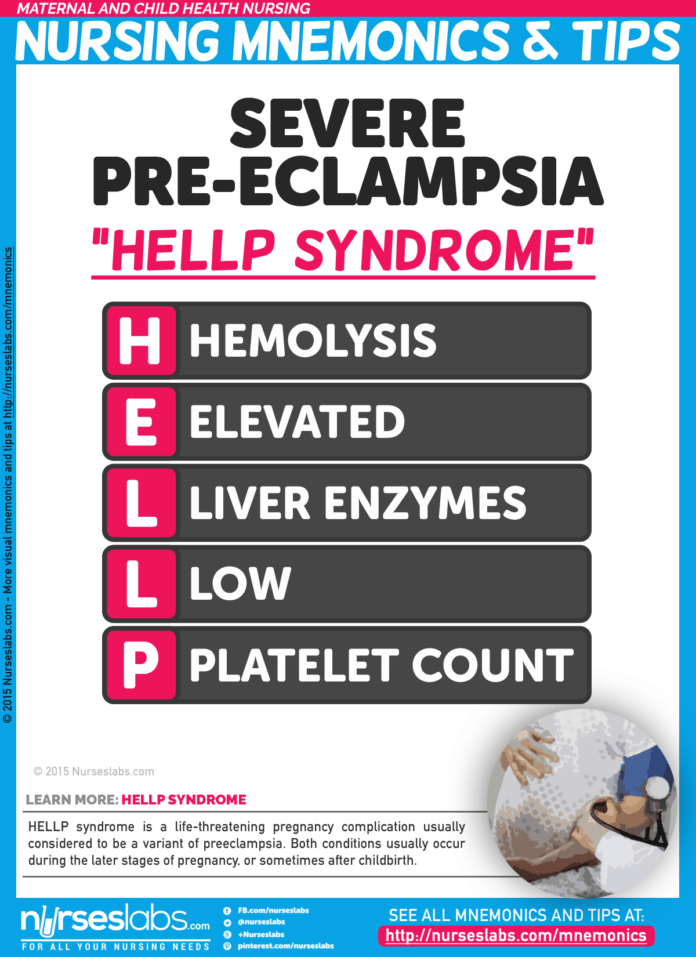

HELLP syndrome. HELLP stands for hemolysis (the destruction of red blood cells), elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count.

This severe form of preeclampsia affects several organ systems. HELLP syndrome is life-threatening to the mother and baby, and it may cause lifelong health problems for the mother.

This severe form of preeclampsia affects several organ systems. HELLP syndrome is life-threatening to the mother and baby, and it may cause lifelong health problems for the mother.Signs and symptoms include nausea and vomiting, headache, upper right belly pain, and a general feeling of illness or being unwell. Sometimes, it develops suddenly, even before high blood pressure is detected. It also may develop without any symptoms.

-

Eclampsia. Eclampsia is the onset of seizures or coma with signs or symptoms of preeclampsia. It is very difficult to predict whether a patient with preeclampsia will develop eclampsia. Eclampsia can happen without any previously observed signs or symptoms of preeclampsia.

Signs and symptoms that may appear before seizures include severe headaches, vision problems, mental confusion or altered behaviors.

But, there are often no symptoms or warning signs. Eclampsia may occur before, during or after delivery.

But, there are often no symptoms or warning signs. Eclampsia may occur before, during or after delivery. - Other organ damage. Preeclampsia may result in damage to the kidneys, liver, lung, heart, or eyes, and may cause a stroke or other brain injury. The amount of injury to other organs depends on how severe the preeclampsia is.

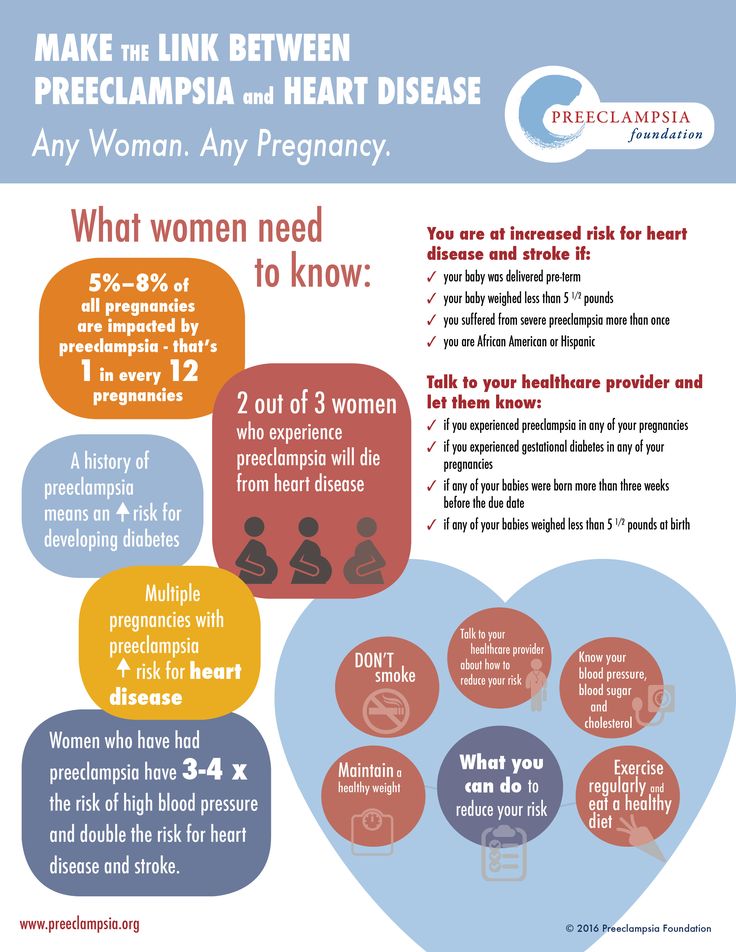

- Cardiovascular disease. Having preeclampsia may increase your risk of future heart and blood vessel (cardiovascular) disease. The risk is even greater if you've had preeclampsia more than once or you've had a preterm delivery.

Prevention

Medication

The best clinical evidence for prevention of preeclampsia is the use of low-dose aspirin. Your primary care provider may recommend taking an 81-milligram aspirin tablet daily after 12 weeks of pregnancy if you have one high-risk factor for preeclampsia or more than one moderate-risk factor.

It's important that you talk with your provider before taking any medications, vitamins or supplements to make sure it's safe for you.

Lifestyle and healthy choices

Before you become pregnant, especially if you've had preeclampsia before, it's a good idea to be as healthy as you can be. Talk to your provider about managing any conditions that increase the risk of preeclampsia.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

News from Mayo Clinic

Products & Services

pathobiology paradigms and clinical practice » Obstetrics and Gynecology

Pre-eclampsia (PE) remains the leading cause of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity. Over the past decades, ideas about the heterogeneous nature of this syndrome have expanded. PE can manifest before 34 weeks (early onset) and after 34 weeks (late onset), during labor or in the postpartum period. It has been shown that early and late PE may have different pathophysiology. Early-onset PE, unlike late-onset PE, is usually accompanied by ischemic disorders in the placenta and fetal growth retardation. Late PE is associated with low-gradient chronic inflammation, higher body mass index, and insulin resistance. Within the framework of the concept of personalized medicine, future directions of research on the prediction and prevention of PE should be based on the identification and refinement of PE subtypes, taking into account the influence of maternal constitutional factors to stratify patients based on specific biomarkers. nine0003

Late PE is associated with low-gradient chronic inflammation, higher body mass index, and insulin resistance. Within the framework of the concept of personalized medicine, future directions of research on the prediction and prevention of PE should be based on the identification and refinement of PE subtypes, taking into account the influence of maternal constitutional factors to stratify patients based on specific biomarkers. nine0003

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is a complication of pregnancy characterized by the presence of arterial hypertension and renal dysfunction, which can manifest as heterogeneous disorders, and also have an adverse effect on the condition of the mother and/or the fetus [1].

Currently, hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are divided into chronic arterial hypertension, gestational arterial hypertension, preeclampsia that occurred de novo after 20 weeks of pregnancy or accumulated on previous hypertension. In addition, the expediency of distinguishing “white coat” hypertension as a separate condition is being actively discussed [2]. nine0003

nine0003

PE occurs in 2–8% of pregnancies and is the leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality [3, 4]. Maternal mortality is 12 times higher with the development of PE before 28 weeks of gestation. Currently, a classification of gestational hypertension and PE has been developed depending on the gestational age at the time of diagnosis or, in some cases, at the time of delivery (early and late PE). At the same time, the period of 34 weeks is most often considered as a reference [5], since it correlates with impaired placentation in the early stages. Early PE is associated with higher rates of neonatal morbidity and mortality; Late-onset PE accounts for 75–80% of all cases of PE and is a major contributor to late preterm birth as well as maternal mortality and severe morbidity. nine0003

Despite the fact that many researchers have studied various aspects in detail, the pathogenesis of PE remains not entirely clear, and the expected success in predicting, preventing and treating PE has not been achieved [6]. This is probably due to the fact that PE is the final clinical manifestation of disorders of various origins. It seems that the nature of the disease is different if it developed before 34 weeks or at almost full-term pregnancy. However, many researchers, as a rule, do not separate these two conditions, which lead to fundamentally different outcomes. However, the "combination" of early and late PE in research and development of clinical strategies may complicate further study of the pathophysiology of this syndrome and the achievement of significant clinical results. nine0003

This is probably due to the fact that PE is the final clinical manifestation of disorders of various origins. It seems that the nature of the disease is different if it developed before 34 weeks or at almost full-term pregnancy. However, many researchers, as a rule, do not separate these two conditions, which lead to fundamentally different outcomes. However, the "combination" of early and late PE in research and development of clinical strategies may complicate further study of the pathophysiology of this syndrome and the achievement of significant clinical results. nine0003

This review analyzes the changes that have undergone modern concepts of the pathophysiology of PE over the past two decades, provides evidence to support the hypothesis of the existence of two phenotypes - early and late PE, and also considers the existing opportunities and promising areas of research on the prediction, prevention and treatment of PE .

It is now clear that PE, along with preterm birth, fetal growth restriction (FGR), antenatal fetal death, and other gestational conditions responsible for maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality, is not a single disease but a multifactorial syndrome. All of the above conditions were designated by the term "major obstetric syndromes" [7], which are associated with insufficiently deep placentation, which may be associated with varying degrees of reduced remodeling and obstructive damage to the spiral arteries in the junction area or in the myometrium (Table 1) [8] ]. The introduction of the term "major obstetric syndromes" was intended to explain the failures of work on the prediction and prevention of obstetric diseases, drawing the attention of researchers and clinicians to the etiological heterogeneity of conditions that have common pathogenetic pathways [9].

All of the above conditions were designated by the term "major obstetric syndromes" [7], which are associated with insufficiently deep placentation, which may be associated with varying degrees of reduced remodeling and obstructive damage to the spiral arteries in the junction area or in the myometrium (Table 1) [8] ]. The introduction of the term "major obstetric syndromes" was intended to explain the failures of work on the prediction and prevention of obstetric diseases, drawing the attention of researchers and clinicians to the etiological heterogeneity of conditions that have common pathogenetic pathways [9].

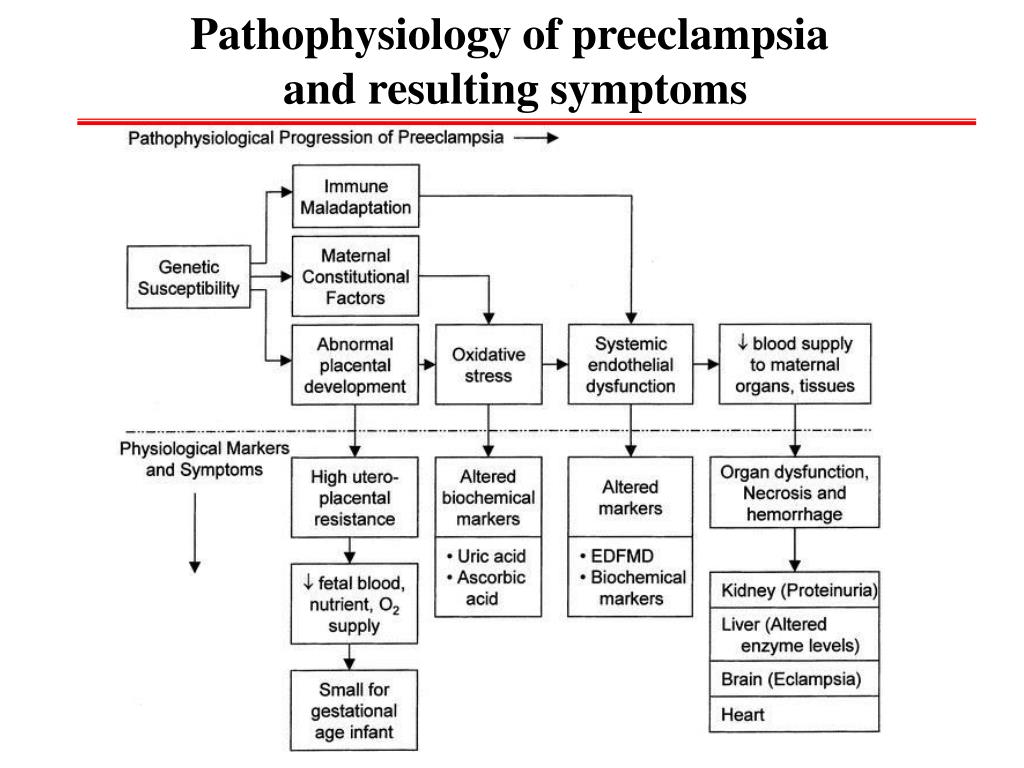

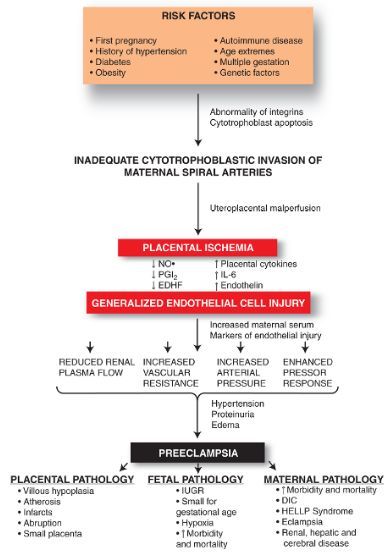

Basic research has shown that PE is associated with a systemic inflammatory response, endothelial dysfunction, imbalance of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors, and metabolic disorders [10-12]. The starting point of these pathological processes is considered to be defective trophoblast invasion [8].

The two-stage model for the development of PE suggests that as a result of reduced perfusion (stage 1), the placenta produces substances that, interacting with predisposing maternal factors (genetic, constitutional, environmental factors, etc. ), lead to clinical manifestations of PE (2- i stage) [13]. However, questions are still being discussed regarding the links between these two stages, the final manifestation of which is the clinical manifestation of PE. According to the two-stage developmental model, the clinical manifestations of PE are the final stage of early placentation disorders and adaptation of the spiral arteries. Subsequently, a three-stage model was proposed, in which the first stage is insufficient immune adaptation of the maternal organism to the fetus. Immune susceptibility to the fetus occurs immediately after implantation. Decidua NK cells accumulate during the luteal phase of the conception cycle, at which time T cells are already able to show their activity. Probably, immunoregulation is activated in the earliest stages of pregnancy. Thus, already in the process of coitus, exposure to paternal seminal fluid and sperm contributes to the development of tolerance to paternal antigens that can be expressed in the fetus.

), lead to clinical manifestations of PE (2- i stage) [13]. However, questions are still being discussed regarding the links between these two stages, the final manifestation of which is the clinical manifestation of PE. According to the two-stage developmental model, the clinical manifestations of PE are the final stage of early placentation disorders and adaptation of the spiral arteries. Subsequently, a three-stage model was proposed, in which the first stage is insufficient immune adaptation of the maternal organism to the fetus. Immune susceptibility to the fetus occurs immediately after implantation. Decidua NK cells accumulate during the luteal phase of the conception cycle, at which time T cells are already able to show their activity. Probably, immunoregulation is activated in the earliest stages of pregnancy. Thus, already in the process of coitus, exposure to paternal seminal fluid and sperm contributes to the development of tolerance to paternal antigens that can be expressed in the fetus. In this regard, it seems quite logical to expand the model of PE development to four stages [14] by including the preconception stage in it. However, not in all cases it is possible to trace the described stages [13]. For example, in some women with hypersensitivity due to the presence of underlying vascular inflammation, PE may develop directly in the last stage ("maternal" PE). It is also well known that impaired placentation can cause IGR without manifestations of PE. Thus, the earlier stages do not always inevitably lead to the final stage (the development of PE). The preconception stage will only occur when there is a short interval between coitus and conception with the same partner [14]. nine0003

In this regard, it seems quite logical to expand the model of PE development to four stages [14] by including the preconception stage in it. However, not in all cases it is possible to trace the described stages [13]. For example, in some women with hypersensitivity due to the presence of underlying vascular inflammation, PE may develop directly in the last stage ("maternal" PE). It is also well known that impaired placentation can cause IGR without manifestations of PE. Thus, the earlier stages do not always inevitably lead to the final stage (the development of PE). The preconception stage will only occur when there is a short interval between coitus and conception with the same partner [14]. nine0003

Clinical heterogeneity of preeclampsia:

- concept of phenotypes

- early and late start

Recently, the concept of the heterogeneous nature of PE has been significantly expanded. Early and late onset PE (Table 2), recurrent and non-recurrent forms, forms with severe and moderate course, with and without IGR, with proteinuria and without proteinuria, with extremely high blood pressure are actively discussed [6]. Evidence has emerged supporting the view that there are two different phenotypic manifestations of PE: early, or placental, and late, or maternal, which seems to be extremely important from the point of view of developing clinical strategies and planning research studies (Table 3). nine0003

Evidence has emerged supporting the view that there are two different phenotypic manifestations of PE: early, or placental, and late, or maternal, which seems to be extremely important from the point of view of developing clinical strategies and planning research studies (Table 3). nine0003

The frequency of early PE varies from 5 to 20% of all cases of PE. The consequences for the fetus and mother are due to damage to the placenta. These are the most severe clinical variants of the course of the disease, the development of which is associated with maladjustment of the immune system, impaired placentation and is characterized by such manifestations as early activation of the sympathoadrenal system, increased levels of endothelial dysfunction markers, insufficient trophoblast invasion, and incomplete transformation of the spiral uterine arteries. This phenotype is associated with IGR, detected by ultrasound biometry, insufficient placental perfusion, recorded using Doppler blood flow in the uterine arteries, where an abnormal shape of the curve is noted with the presence of a dicrotic notch and an increased pulsation index [16], pathological blood flow in the umbilical cord arteries, the degree of violation of which correlates with the severity of placental lesions [17], as well as the small size of the placenta at the time of delivery with characteristic histopathological abnormalities [18]. The course of pregnancy is complicated by severe hypertension and proteinuria, IGR, and ends with induced preterm labor. In fact, in early pregnancy, any hypertensive disorder associated with FGR meets the criteria for PE. The inclusion of FGR in the concept of early PE may further develop into the construction of a new concept of FGR, both with and without hypertension, as a disease with early impaired placentation. nine0003

The course of pregnancy is complicated by severe hypertension and proteinuria, IGR, and ends with induced preterm labor. In fact, in early pregnancy, any hypertensive disorder associated with FGR meets the criteria for PE. The inclusion of FGR in the concept of early PE may further develop into the construction of a new concept of FGR, both with and without hypertension, as a disease with early impaired placentation. nine0003

Late PE is the most common (more than 80% of all cases of PE) and is usually associated with "maternal investment": metabolic syndrome (glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, obesity), chronic hypertension or kidney disease and is rarely accompanied by IUGR. The mass and surface area of the placenta in the development of late PE are increased. Doppler examination of the uterine arteries often does not show any particular changes [19].

Epidemiological study 503 179In primigravida, the ratio of early to late PE was 15:1, and late PE (18,594 cases) correlated with increased maternal body mass index (BMI), while no such association was noted for early PE (1215 cases) [19] . A similar pattern was observed in another study. So, in 38,052 patients with PE and obesity, the ratio of early and late PE turned out to be 11:1, and the frequency of late PE increased with the amount of weight gain at an initially high BMI, while the frequency of early PE remained constant and did not depend on the magnitude BMI [20]. nine0003

A similar pattern was observed in another study. So, in 38,052 patients with PE and obesity, the ratio of early and late PE turned out to be 11:1, and the frequency of late PE increased with the amount of weight gain at an initially high BMI, while the frequency of early PE remained constant and did not depend on the magnitude BMI [20]. nine0003

In addition to these facts, evidence for two PE phenotypes comes from studies showing that visceral obesity defines a pro-inflammatory state with endothelial dysfunction that enhances pro-inflammatory stimuli from the placenta in late pregnancy. The use of uterine artery Doppler in combination with sFlt / PlGF assessment at 24 weeks showed high sensitivity in predicting PE with placental disorders and IUGR, but was not able to predict PE with normal placental function in the absence of IUGR. Finally, a comparison of morphological characteristics showed differences between placentas obtained from women with PE and IGR compared with PE without IGR (Table 3) [18]. nine0003

nine0003

Biochemical and placental factors

Analysis of biochemical and placental determinants revealed their differences in early and late PE. Thus, it has been established that the following changes are characteristic of “early” PE: 1) an increase in the ratio of type 1 plasminogen inhibitor to type 2 (PAI-1/PAI-2), a marker of trophoblast dysfunction [26]; 2) a higher concentration in the placenta of 8-isoprostaglandin F2α, a marker of oxidative stress [26]; 3) higher concentration of elastase, a soluble marker of neutrophil activation [27]; 4) increased blood concentration of retinol-binding protein-4, adipokine, involved in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and inflammation [28]. nine0003

At the same time, an increase in blood levels of adiponectin , an adipokine with anti-inflammatory action, was found only in patients with late PE [29].

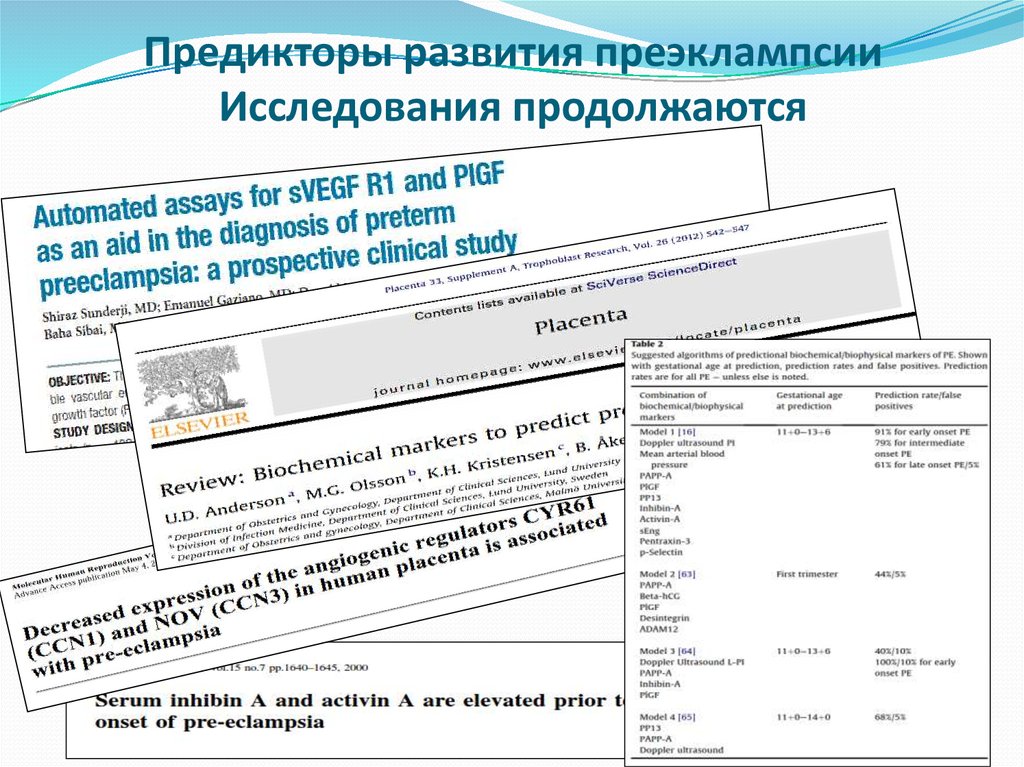

A similar pattern is observed in the concentration of angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors and markers of the functioning of the placenta. Thus, early PE is characterized by: 1) a higher blood concentration of the soluble form of the VEGF receptor of the first type (sVEGFR-1, sFlt-1) [29]; 2) reduced blood concentration of angiogenic factors, placental growth factor (PlGF) or low ratio of PlGF and soluble endoglin (sEng) in the second trimester of pregnancy [30]; 3) an increase in the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio [29], an increase in the blood concentration of PP13, a protein produced mainly by syncytiotrophoblast [31].

Thus, early PE is characterized by: 1) a higher blood concentration of the soluble form of the VEGF receptor of the first type (sVEGFR-1, sFlt-1) [29]; 2) reduced blood concentration of angiogenic factors, placental growth factor (PlGF) or low ratio of PlGF and soluble endoglin (sEng) in the second trimester of pregnancy [30]; 3) an increase in the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio [29], an increase in the blood concentration of PP13, a protein produced mainly by syncytiotrophoblast [31].

Early PE is more characterized by placental injury associated with insufficient maternal perfusion and uteroplacental vascular disease, as well as chronic inflammation. In addition, there is a significant decrease in the volume of the placenta and the surface area of the terminal villi, and placental infarctions, decidua arteriopathy, and premature maturation of the villi are also more common. When studying the placentas of patients with late PE, no significant changes were found [32]. nine0003

Hemodynamic differences between early and late PE

Recently, a search has been made for the dependence of the onset of the clinical manifestation of PE on the hemodynamic profile of the mother. It was found that the hemodynamic features of the mother in early PE are characterized by increased peripheral vascular resistance and low cardiac output, while late PE is characterized by low peripheral resistance and increased cardiac output. These clinical aspects may have a significant impact on differentiated approaches to diagnosis and treatment, as well as on the stratification of cardiovascular risk in these women after delivery [33]. The authors showed that a few weeks before the onset of clinical manifestations of PE in normo- and hypertensive women with identified disorders in the Doppler of the uterine arteries, one can observe high vascular resistance in combination with low cardiac output. Obviously, these data contradict the results of previous studies, which did not analyze the dependence of the hemodynamic characteristics of patients on the timing of the clinical manifestations of PE. The authors also noted that in early and late PE, hemodynamic differences are also associated with differences in the geometry and function of the left ventricle.

It was found that the hemodynamic features of the mother in early PE are characterized by increased peripheral vascular resistance and low cardiac output, while late PE is characterized by low peripheral resistance and increased cardiac output. These clinical aspects may have a significant impact on differentiated approaches to diagnosis and treatment, as well as on the stratification of cardiovascular risk in these women after delivery [33]. The authors showed that a few weeks before the onset of clinical manifestations of PE in normo- and hypertensive women with identified disorders in the Doppler of the uterine arteries, one can observe high vascular resistance in combination with low cardiac output. Obviously, these data contradict the results of previous studies, which did not analyze the dependence of the hemodynamic characteristics of patients on the timing of the clinical manifestations of PE. The authors also noted that in early and late PE, hemodynamic differences are also associated with differences in the geometry and function of the left ventricle. At the same time, conducting randomized trials on the effectiveness of various types of treatment aimed at reducing peripheral resistance and improving the hemodynamic profile, in comparison with the effect on blood pressure alone, may contribute to a differentiated selection, determination of the timing and duration of therapy. nine0003

At the same time, conducting randomized trials on the effectiveness of various types of treatment aimed at reducing peripheral resistance and improving the hemodynamic profile, in comparison with the effect on blood pressure alone, may contribute to a differentiated selection, determination of the timing and duration of therapy. nine0003

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia - consecutive stages of the same process?

It is traditionally considered that eclampsia unfolds in a linear sequence from moderate and severe PE to seizures, is the last climactic phase, the most severe form of PE that occurs in the absence of timely prevention of seizures [34]. At the same time, there are works that challenge the traditional paradigm of eclampsia as a predictable and potentially preventable condition. In contrast to headache, which occurs shortly before seizures, less than half of patients have signs or symptoms of HE before seizures. The occurrence of eclampsia does not always clearly correlate with the degree of proteinuria or the magnitude of arterial hypertension. In 60%, seizures were the first symptom of PE. Almost all patients had hypertension after seizures, but not all before seizures. With eclampsia, cerebrovascular damage occurs, convulsions are of a special "non-traditional" nature. This, apparently, explains the low effectiveness of traditional anticonvulsants, which usually affect the function of neurons, in comparison with magnesium sulfate, which affects vascular tone. However, it remains unclear the category of patients with PE in whom damage to the cerebral vessels leading to the development of eclampsia can occur. nine0003

In 60%, seizures were the first symptom of PE. Almost all patients had hypertension after seizures, but not all before seizures. With eclampsia, cerebrovascular damage occurs, convulsions are of a special "non-traditional" nature. This, apparently, explains the low effectiveness of traditional anticonvulsants, which usually affect the function of neurons, in comparison with magnesium sulfate, which affects vascular tone. However, it remains unclear the category of patients with PE in whom damage to the cerebral vessels leading to the development of eclampsia can occur. nine0003

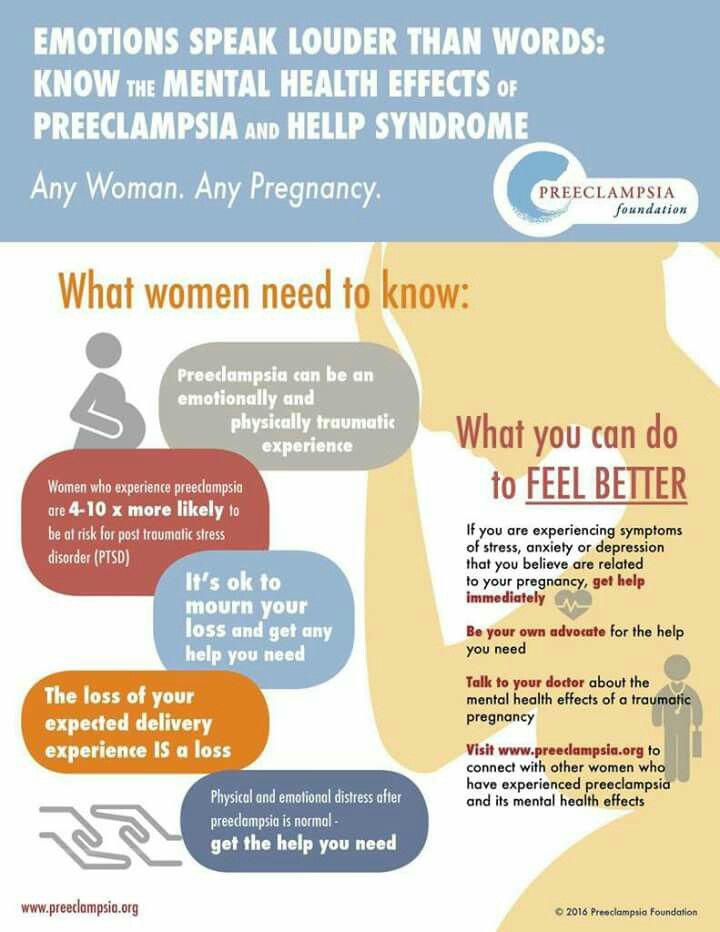

Pre-eclampsia is a pathology not only during pregnancy

With the development of biomedical research, ideas about PE have transformed from a disease during pregnancy, characterized by a combination of hypertension and renal dysfunction, to a heterogeneous multisystem disorder that affects the health of mother and child during subsequent life, which confirms the “Barker hypothesis” about the possibility of perinatal programming of adult diseases [35]. Women with a history of PE have a higher risk of premature death from coronary heart disease, other vascular diseases, including hypertension, stroke, venous thromboembolism, renal failure, type II diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and behavioral disorders. Children born to mothers with PE are more prone to hypertension, insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus, neurological problems, stroke, and psychiatric disorders throughout life [36]. nine0003

Women with a history of PE have a higher risk of premature death from coronary heart disease, other vascular diseases, including hypertension, stroke, venous thromboembolism, renal failure, type II diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and behavioral disorders. Children born to mothers with PE are more prone to hypertension, insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus, neurological problems, stroke, and psychiatric disorders throughout life [36]. nine0003

Clinical aspects of ET in the context of the development of molecular medicine: prediction, prevention, diagnosis, treatment

In recent years, the concept of so-called personalized medicine has been actively developed, which is considered as an important direction in the development of clinical medicine [37, 38]. Post-genomic studies aimed at the development of biological markers (at the level of the genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome) are a powerful impetus for the development of diagnostics that allows stratification of patients, predicting the risks of developing and clinical course of PE, as well as developing regimens for directed (targeted) treatment. nine0003

nine0003

The prediction of PE has improved mainly due to the identification of angiogenic/anti-angiogenic factors, although the sensitivity and specificity of such tests are still not optimal, and the heterogeneity of associated clinical risks makes it difficult to extend a single test in early pregnancy to the entire population of women. The so-called omics methodology has the potential to discover new biomarkers, and proteomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic approaches have begun to reveal many new candidates for evaluating their significance. At the same time, upon the onset of pregnancy, the possibilities for modifying the developed pathological processes, detected mainly by accurate biomarkers, remain a controversial and, possibly, unattainable task. The potential for more accurate preconceptual risk identification and subsequent risk modification represents a highly attractive alternative to preventing PE. Determination of PlGF levels in women with suspected PE is likely to become an integral component of clinical care that improves the detection and management of PE. nine0003

nine0003

The contribution of genetic factors to the development of PE is supported by family history data, although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Maternal constitutional and environmental factors may influence through epigenetic programming of the gametes, placenta, and fetus. Violation of genomic imprinting in the placental tissue, leading to a redistribution of the expression of paternal genes in relation to maternal ones, is also considered as a predisposing factor for the development of PE. nine0003

The study of gene-gene, gene-environment relationships and the underlying epigenetic mechanisms [38] associated with the programming of trophoblast cells, as well as how this correlates with placental disorders and systemic manifestations of various PE phenotypes. These phenotypes include HELLP syndrome and other placental complications such as isolated IUGR. Knowledge of this could guide future specific interventions in the periconceptional period and early pregnancy to model beneficial effects during placental formation in high-risk women, such as reducing excessive inflammation and oxidative stress (using statins or metformin), improving endothelial health [5] . nine0003

nine0003

Studies have shown the possibility of reducing the incidence of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy after low-dose periconceptional aspirin [39]. Heparin therapy, which suppresses excessive development of trophoblast, can be considered as a favorable preventive intervention in some groups of patients [40]. To resolve the issue of the possibility of therapeutic support for the process of optimal remodeling of the spiral arteries, it is necessary to conduct large comparative studies related to the study of the placental bed. In addition, pharmacological approaches for the correction of anti-angiogenic conditions in late PE seem promising. Epigenetic modification of fetal vascular tissues during pregnancy complicated by PE may also be associated with future reproductive status and cardiovascular health [41]. Men and women exposed to PE in utero, as well as women born with a low birth weight for a given gestational age, have an increased risk of developing PE during pregnancy [42], a higher risk of arterial hypertension, signs of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases in relatively early age [43]. nine0003

nine0003

Gut microbiota, which represents the endogenous human intestinal microflora, is an important “organ” that provides nutrition, regulates epithelial development, and provides signals for innate immunity [44]. There are interesting biological studies showing that probiotics can appropriately modulate the gastrointestinal system and influence low-intensity systemic inflammation [45]. An additional pathway by which probiotics may modulate the risk of PE is their role in reducing homocysteinemia, which is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes [46]. There is a growing number of studies that draw parallels between organ damage in metabolic syndrome with inflammasomes and the microbiome [47]. nine0003

At the preconception stage of observation, it is important to develop available methods for predicting the recurrence of early hypertensive complications of pregnancy [48]. Proteomic identification of clinically significant prognostic biomarkers during pregnancy becomes quite feasible [49]. Moreover, it is necessary to develop criteria for the severity of PE that would objectively identify women with a differentiated risk of adverse outcomes. It is extremely important to conduct randomized controlled trials to establish recommendations for the management of severe PE with an early onset of clinical manifestation. nine0003

Moreover, it is necessary to develop criteria for the severity of PE that would objectively identify women with a differentiated risk of adverse outcomes. It is extremely important to conduct randomized controlled trials to establish recommendations for the management of severe PE with an early onset of clinical manifestation. nine0003

Research is needed to develop proteomic and matabolic panels that, in combination with clinical parameters, would evaluate the clinical acceptability of predictive tests for PE in early pregnancy. When patients of the “high risk” group are identified, it becomes possible to stratify observation during pregnancy, using a personalized approach for mother and fetus, early diagnosis, timely interventions, while saving significant financial resources. Based on the analysis of epidemiological data on the long-term outcomes of PE and the underlying mechanisms, as well as an understanding of the etiology of the process, it is possible to develop strategies for the prevention and monitoring of women with a history of PE. nine0003

nine0003

Conclusion

PE is the final clinical manifestation of pregnancy disorders of various origins. Data from biological, clinical and epidemiological studies support the view that there are two different phenotypic manifestations of PE: early, or placental, and late, or maternal, which must be considered by both clinicians and scientists. Molecular medicine will soon be able to provide strong evidence for the existence of PE biomarkers. Recognizing the contribution of epigenetics to placental gene expression will be a key first step in identifying genes associated with PE. Within the framework of the concept of personalized medicine, future directions of research on the prediction and prevention of PE should be based on the identification and refinement of subtypes of PE, taking into account the influence of maternal constitutional factors to stratify patients based on specific biomarkers. In this regard, it seems very encouraging to conduct post-genomic studies, in particular metabolomics, which will allow identifying the origin of PE and, thus, will contribute to the selection of target groups for therapeutic and prophylactic measures. nine0003

nine0003

Khodzhaeva Zulfiya Sagdullaevna, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Chief Researcher of the 1st Obstetric Department of Pathology of Pregnancy, FGBU NCAGiP named after. academician V.I. Kulakov of the Ministry of Health of Russia

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Academician Oparina, 4. E-mail: [email protected]

Kholin Aleksey Mikhailovich academician V.I. Kulakov of the Ministry of Health of Russia

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. Academician Oparina, 4. E-mail: [email protected]

Vikhlyaeva Ekaterina Mikhailovna, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Corresponding Member. RAMS, chief researcher of the Federal State Budgetary Institution NTsAGiP them. academician V.I. Kulakov of the Ministry of Health of Russia

Address: 117997, Russia, Moscow, st. E-mail: [email protected]

preeclampsia

Every mother-to-be wants her pregnancy to become a time of joyful expectation. But the fear of preeclampsia can darken the joy.

But the fear of preeclampsia can darken the joy.

nine0003

What is preeclampsia?

Pre-eclampsia is a potentially life-threatening disease that occurs during pregnancy and affects multiple organ systems and is characterized by high maternal blood pressure and protein in the urine, or in the absence of the latter, dysfunction of other organ systems. This can affect both you and your unborn child. If the risk of preeclampsia is known in advance, it can be prevented. nine0003

How common is preeclampsia?

Most women have a normal pregnancy. At the same time, pre-eclampsia is a relatively common disease during pregnancy, which occurs in two out of a hundred women in Estonia.

When does preeclampsia occur?

Preeclampsia occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy or up to six weeks after delivery. Most often, preeclampsia occurs between the 32nd and 36th weeks of pregnancy. The earlier in pregnancy the disease occurs, the more severe its course, and the more dangerous it is for the mother and child. nine0003

The earlier in pregnancy the disease occurs, the more severe its course, and the more dangerous it is for the mother and child. nine0003

What causes preeclampsia?

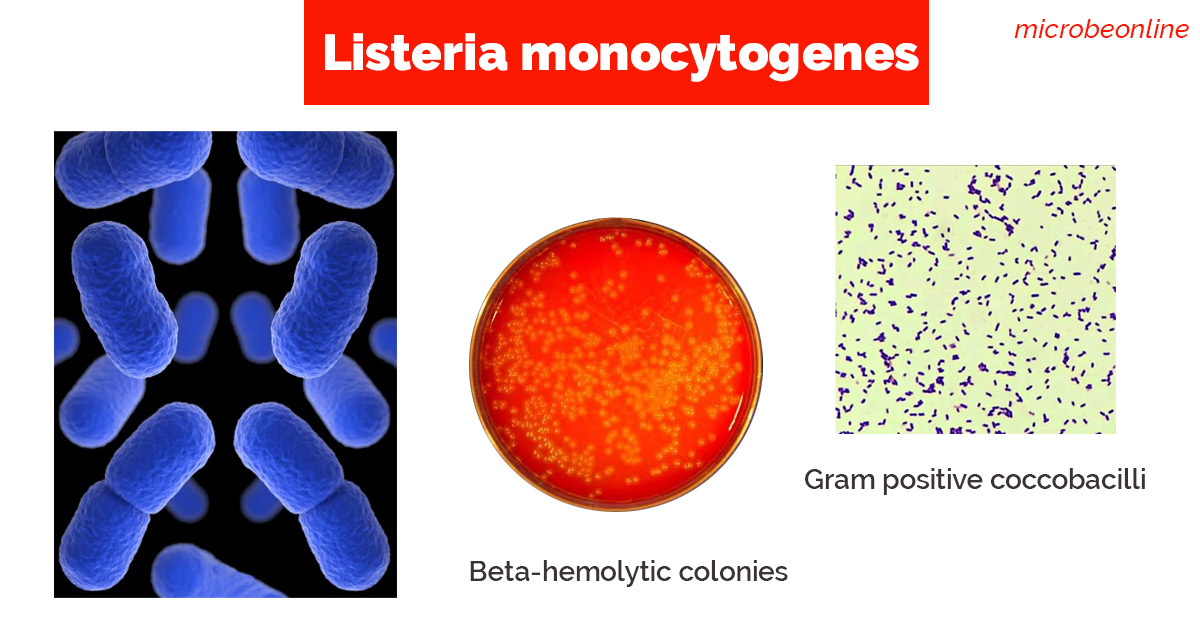

The exact causes of pre-eclampsia are unknown, but it is believed that they lie in a violation of the attachment of the developing placenta to the uterus, as a result of which there is no reliable connection between the circulatory systems of the mother and child. At the same time, a rapidly developing fetus requires oxygen and nutrients from the mother's circulatory system for its growth. If oxygen deficiency occurs in the developing placenta, toxic substances are released into the mother's circulatory system, which damage the lining of the mother's blood vessels. This is how a systemic lesion of the internal organs of the mother is formed. In order to save the lives of mother and child, the child must be born. If this happens at a very early stage of pregnancy, the baby is not yet ready for extrauterine life. nine0003

nine0003

How will this affect me?

Mostly mild form of the disease occurs at the end of pregnancy and the prognosis is good. But sometimes pre-eclampsia can get worse very quickly and begin to threaten the lives of the mother and child. Preeclampsia also has a long-term effect on a woman's health, as it doubles the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the future. Most women with preeclampsia are hospitalized, and often their children have to be born prematurely. If the health of the mother or child is at risk, labor is induced or a caesarean section is performed. nine0003

How will this affect my child?

Most children remain healthy even when their mothers have severe preeclampsia. But sometimes preeclampsia can threaten the life and health of both the fetus and the newborn. Maternal preeclampsia doubles the risk of a surviving child suffering from cerebral palsy, that is, brain damage that results in delayed physical and sometimes mental development. In addition, surviving children are more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes in the future. In preeclampsia, there is not enough oxygen and nutrients for the growth of the fetus, and intrauterine growth retardation occurs. Since the only treatment for preeclampsia is childbirth, sometimes the pregnancy has to be terminated. Until the 34th week of pregnancy, the lungs of the fetus have not yet fully developed, and steroid injections are given to the pregnant woman to stimulate them. nine0003

In addition, surviving children are more likely to develop cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes in the future. In preeclampsia, there is not enough oxygen and nutrients for the growth of the fetus, and intrauterine growth retardation occurs. Since the only treatment for preeclampsia is childbirth, sometimes the pregnancy has to be terminated. Until the 34th week of pregnancy, the lungs of the fetus have not yet fully developed, and steroid injections are given to the pregnant woman to stimulate them. nine0003

How to recognize preeclampsia?

Unfortunately, in most women, the symptoms of the disease appear only at an advanced stage.

- Chronic headache not responding to painkillers

- Severe nausea and vomiting

- Visual disturbances, tinnitus

- Pain in the right hypochondrium

- Feeling short of breath, shortness of breath

- Infrequent urge to urinate (less than 500 ml per day)

- Edema of hands, face and eyelids

- Rapid weight gain (more than 1 kg per week)

If you experience any of the above symptoms, contact your obstetrician, gynecologist or hospital doctor on call.

Am I at risk?

Although all pregnant women can develop preeclampsia, some women are more at risk than others.

You are more at risk if

- this is your first pregnancy;

- you had preeclampsia during a previous pregnancy;

- your sister or mother had preeclampsia;

- Your body mass index is 35 kg/m 2 or more;

- You are at least 40 years old;

- the time between births was more than 10 years;

- You are expecting twins;

- You have become pregnant in vitro; nine0024

- you have any medical problem, such as hypertension, kidney problems, lupus, diabetes;

- You developed diabetes during this pregnancy.

At what stage of pregnancy is screening performed?

Pre-eclampsia screening can be performed in all three trimesters.

- First trimester, 11-13 weeks +6 (OSCAR)

- Second trimester, 19-21 weeks +6 weeks (as part of fetal anatomy screening)

- Third trimester, 34-36 weeks (as part of a growth and fetal study)

A three-stage screening test for preeclampsia can prevent it from occurring or move it to a later stage of pregnancy.

How reliable is screening for preeclampsia? nine0042

In the first trimester, the OSCAR test can identify women at risk of developing early preeclampsia with 76% accuracy before the 37th week of pregnancy. Among pregnant twins, all women who can develop early preeclampsia can be identified before the 37th week of pregnancy.

In the second trimester, fetal anatomy screening can identify women at risk of developing early preeclampsia with an accuracy of 85% before the 37th week of pregnancy. nine0003

In the third trimester, growth and fetal ultrasound can identify women at risk for developing late preeclampsia after 37 weeks of pregnancy with 85% accuracy.

Why should I assess my risk for preeclampsia?

The best way to assess the risk of early preeclampsia is in the first trimester with the OSCAR test, when at-risk women will benefit from the preeclampsia-preventing effect of aspirin. Studies have shown that small doses of aspirin before the 16th week of pregnancy in 62% of cases reduce the risk of early preeclampsia, which may require delivery before the 37th week. Therefore, women with an increased risk of preeclampsia are advised to take 150 milligrams of aspirin once a day, in the evenings, until the 36th week of pregnancy. The goal of prophylactic treatment for women at high risk of preeclampsia is either to avoid the development of preeclampsia or to postpone its occurrence until later in pregnancy, when the child is ready for birth. nine0003

Studies have shown that small doses of aspirin before the 16th week of pregnancy in 62% of cases reduce the risk of early preeclampsia, which may require delivery before the 37th week. Therefore, women with an increased risk of preeclampsia are advised to take 150 milligrams of aspirin once a day, in the evenings, until the 36th week of pregnancy. The goal of prophylactic treatment for women at high risk of preeclampsia is either to avoid the development of preeclampsia or to postpone its occurrence until later in pregnancy, when the child is ready for birth. nine0003

In the second trimester, fetal anatomy screening can reassess the OSCAR risk for preeclampsia or recommend screening for preeclampsia in women who were not assessed for preeclampsia by OSCAR.

In the third trimester, ultrasound examination of the growth and condition of the fetus can assess the risk of late preeclampsia. This is very important as 75% of preeclampsia cases develop after the 37th week of pregnancy. This makes it possible to more intensively examine women with an increased risk of preeclampsia and to detect the disease in a timely manner, as well as to prepare the baby's lungs for an early birth. nine0003

This makes it possible to more intensively examine women with an increased risk of preeclampsia and to detect the disease in a timely manner, as well as to prepare the baby's lungs for an early birth. nine0003

How is preeclampsia screened?

Screening for pre-eclampsia consists of an appointment with a nurse and an ultrasound examination by a gynecologist. The nurse interviews the pregnant woman, measuring her blood pressure, height and weight, and doing a blood test. The gynecologist performs an ultrasound examination and measures the blood flow indices of the uterine arteries feeding the placenta. Based on the blood test values of hormone levels and associated risk factors for preeclampsia, blood pressure parameters, body mass index and uterine arterial blood flow indices, the gynecologist uses a special computer program to assess the individual risk of early or late preeclampsia. nine0003

- The risk of preeclampsia can be assessed in one day.