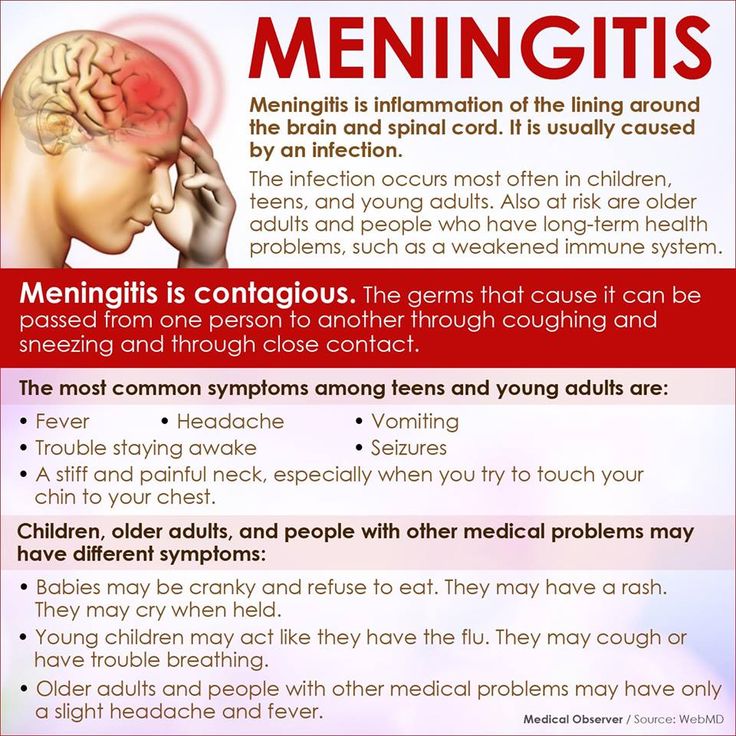

Does meningitis cause rash

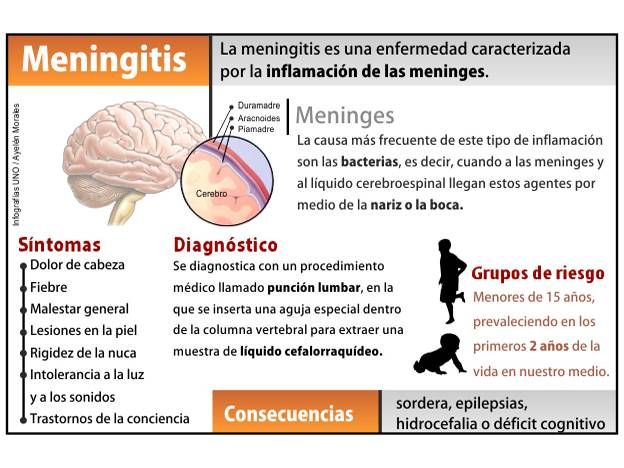

Meningitis - Symptoms - NHS

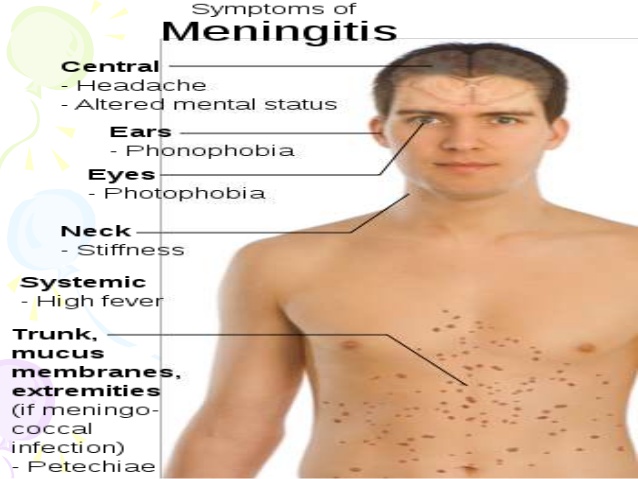

Symptoms of meningitis can appear in any order. Some may not appear at all. In the early stages, there may not be a rash, or the rash may fade when pressure is applied.

You should get medical help immediately if you're concerned about yourself or your child.

Trust your instincts and do not wait for all the symptoms to appear or until a rash develops.

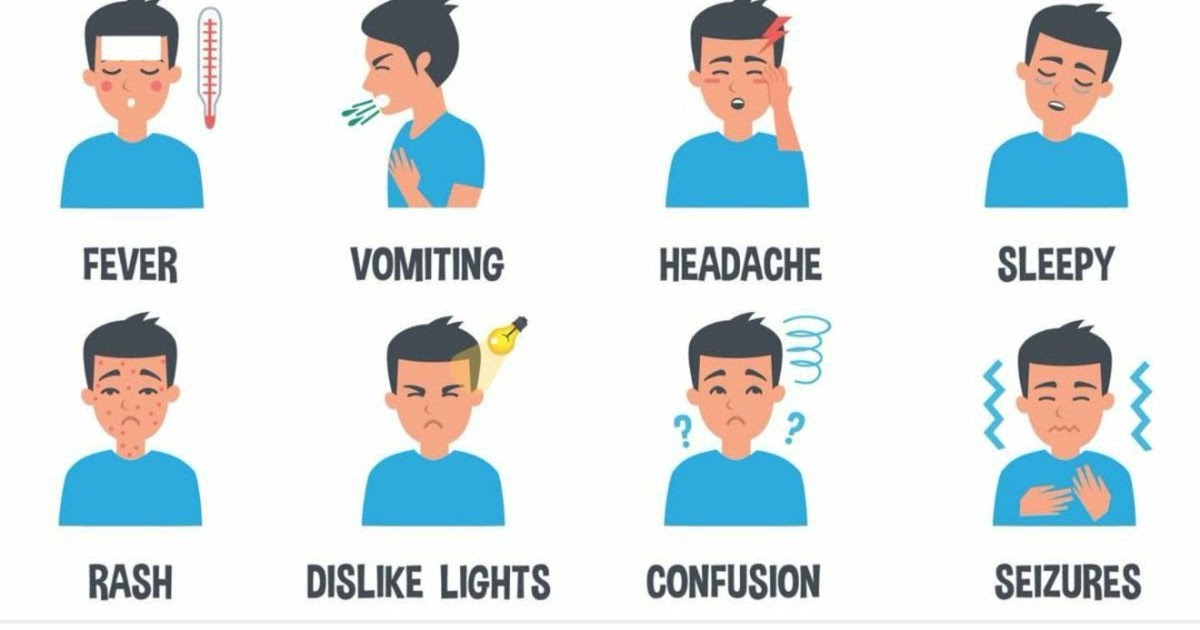

Symptoms of meningitis and sepsis include:

- a high temperature

- cold hands and feet

- vomiting

- confusion

- breathing quickly

- muscle and joint pain

- pale, mottled or blotchy skin (this may be harder to see on brown or black skin)

- spots or a rash (this may be harder to see on brown or black skin)

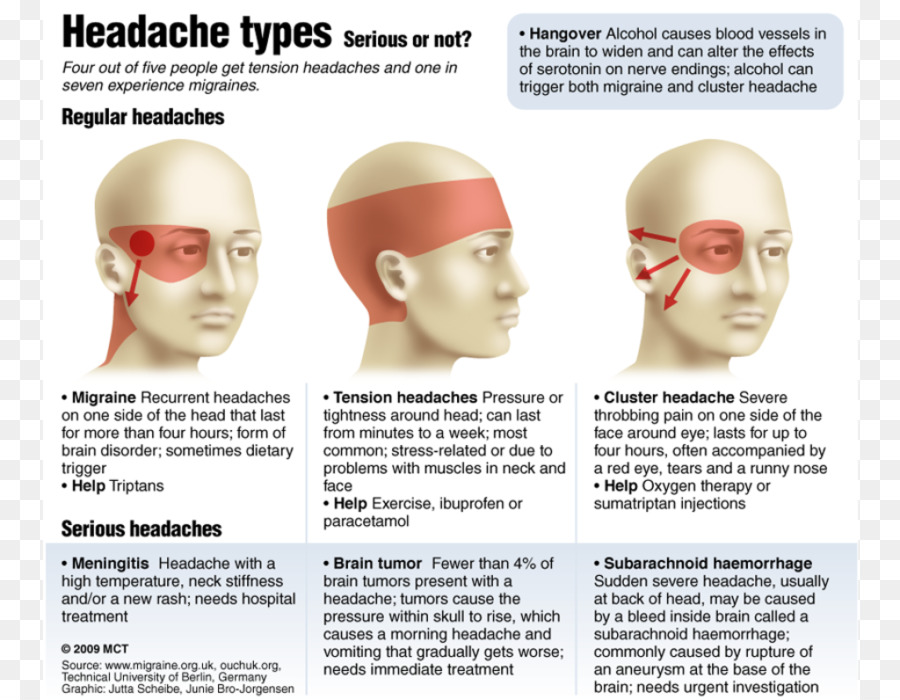

- headache

- a stiff neck

- a dislike of bright lights

- being very sleepy or difficult to wake

- fits (seizures)

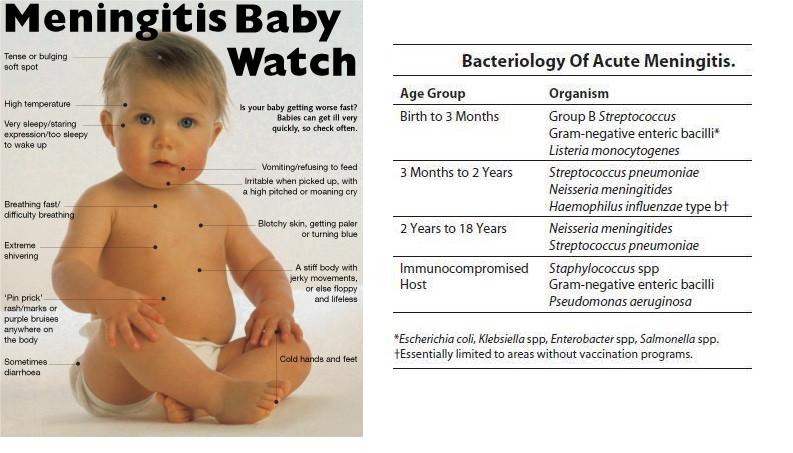

Babies may also:

- refuse feeds

- be irritable

- have a high-pitched cry

- have a stiff body or be floppy or unresponsive

- have a bulging soft spot on the top of their head

Someone with meningitis or sepsis can get a lot worse very quickly.

Call 999 for an ambulance or go to your nearest A&E immediately if you think you or someone you look after could have meningitis or sepsis.

Call NHS 111 for advice if you're not sure if it's anything serious.

If you’ve had medical advice and are still worried or any symptoms get worse, get medical help again.

The rash usually starts as small, red pinpricks before spreading quickly and turning into red or purple blotches.Credit:

Mediscan / Alamy Stock Photo https://www.alamy.com/meningococcal-rash-image1683649.html?pv=1&stamp=2&imageid=83D4AFC7-AC4B-4271-B09C-727E90532943&p=17774&n=0&orientation=0&pn=1&searchtype=0&IsFromSearch=1&srch=foo%3dbar%26st%3d0%26pn%3d1%26ps%3d100%26sortby%3d2%26resultview%3dsortbyPopular%26npgs%3d0%26qt%3dATB0C2%26qt_raw%3dATB0C2%26lic%3d3%26mr%3d0%26pr%3d0%26ot%3d0%26creative%3d%26ag%3d0%26hc%3d0%26pc%3d%26blackwhite%3d%26cutout%3d%26tbar%3d1%26et%3d0x000000000000000000000%26vp%3d0%26loc%3d0%26imgt%3d0%26dtfr%3d%26dtto%3d%26size%3d0xFF%26archive%3d1%26groupid%3d%26pseudoid%3d788068%26a%3d%26cdid%3d%26cdsrt%3d%26name%3d%26qn%3d%26apalib%3d%26apalic%3d%26lightbox%3d%26gname%3d%26gtype%3d%26xstx%3d0%26simid%3d%26saveQry%3d%26editorial%3d1%26nu%3d%26t%3d%26edoptin%3d%26customgeoip%3d%26cap%3d1%26cbstore%3d1%26vd%3d0%26lb%3d%26fi%3d2%26edrf%3d0%26ispremium%3d1%26flip%3d0%26pl%3d

It does not fade if you press the side of a clear glass firmly against the skin.

Credit:

Alamy Stock Photo https://www.alamy.com/testing-of-meningococcal-rash-image589611.html?pv=1&stamp=2&imageid=6C8D2A33-C874-43AF-A58B-398C0D9552AF&p=17774&n=0&orientation=0&pn=1&searchtype=0&IsFromSearch=1&srch=foo%3dbar%26st%3d0%26pn%3d1%26ps%3d100%26sortby%3d2%26resultview%3dsortbyPopular%26npgs%3d0%26qt%3dA8FF2B%26qt_raw%3dA8FF2B%26lic%3d3%26mr%3d0%26pr%3d0%26ot%3d0%26creative%3d%26ag%3d0%26hc%3d0%26pc%3d%26blackwhite%3d%26cutout%3d%26tbar%3d1%26et%3d0x000000000000000000000%26vp%3d0%26loc%3d0%26imgt%3d0%26dtfr%3d%26dtto%3d%26size%3d0xFF%26archive%3d1%26groupid%3d%26pseudoid%3d195878%26a%3d%26cdid%3d%26cdsrt%3d%26name%3d%26qn%3d%26apalib%3d%26apalic%3d%26lightbox%3d%26gname%3d%26gtype%3d%26xstx%3d0%26simid%3d%26saveQry%3d%26editorial%3d1%26nu%3d%26t%3d%26edoptin%3d%26customgeoip%3d%26cap%3d1%26cbstore%3d1%26vd%3d0%26lb%3d%26fi%3d2%26edrf%3d0%26ispremium%3d1%26flip%3d0%26pl%3d

The rash can be harder to see on brown or black skin. Check paler areas, such as the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, roof of the mouth, tummy, whites of the eyes or the inside of the eyelids.

Check paler areas, such as the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, roof of the mouth, tummy, whites of the eyes or the inside of the eyelids. Credit:

Meningitis Research UK https://hscic365.sharepoint.com/sites/Pilot/NHSUK/Health%20AZ/Forms/AllItems.aspx?id=%2Fsites%2FPilot%2FNHSUK%2FHealth%20AZ%2FHealth%20A%2DZ%2FA%2DZ%20content%20audit%2FM%2FMeningitis%2FImage%20and%20section%20review%2007%202019%2FRe%5FPhotography%20of%20the%20meningitis%20rash%2Eeml&parent=%2Fsites%2FPilot%2FNHSUK%2FHealth%20AZ%2FHealth%20A%2DZ%2FA%2DZ%20content%20audit%2FM%2FMeningitis%2FImage%20and%20section%20review%2007%202019

If a rash does not fade under a glass, it can be a sign of sepsis (sometimes called septicaemia or blood poisoning) caused by meningitis and you should call 999 straight away.

Page last reviewed: 25 October 2022

Next review due: 25 October 2025

What is the 'meningitis rash'?

When we think of meningitis, we may think of the so-called ‘meningitis rash’ – a red or purple marking on the body which remains present when pressed with a glass.

However, the rash does not always appears in cases of meningitis, and the word ‘rash’ itself may be misleading. Information and Support Officer Katherine Carter explains more.What is the meningitis rash?

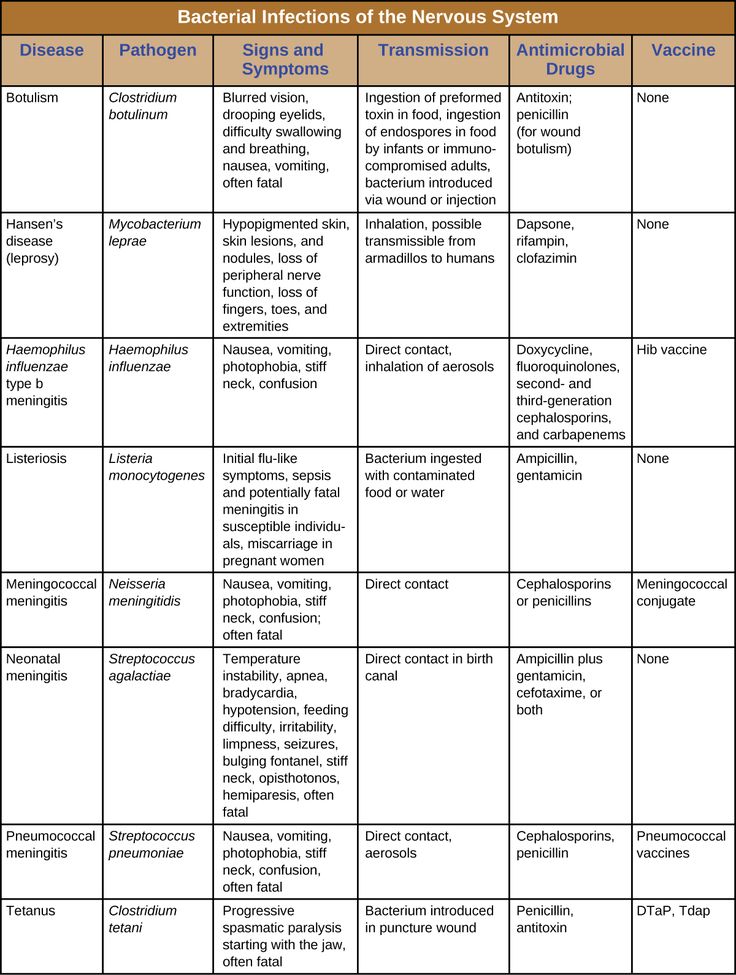

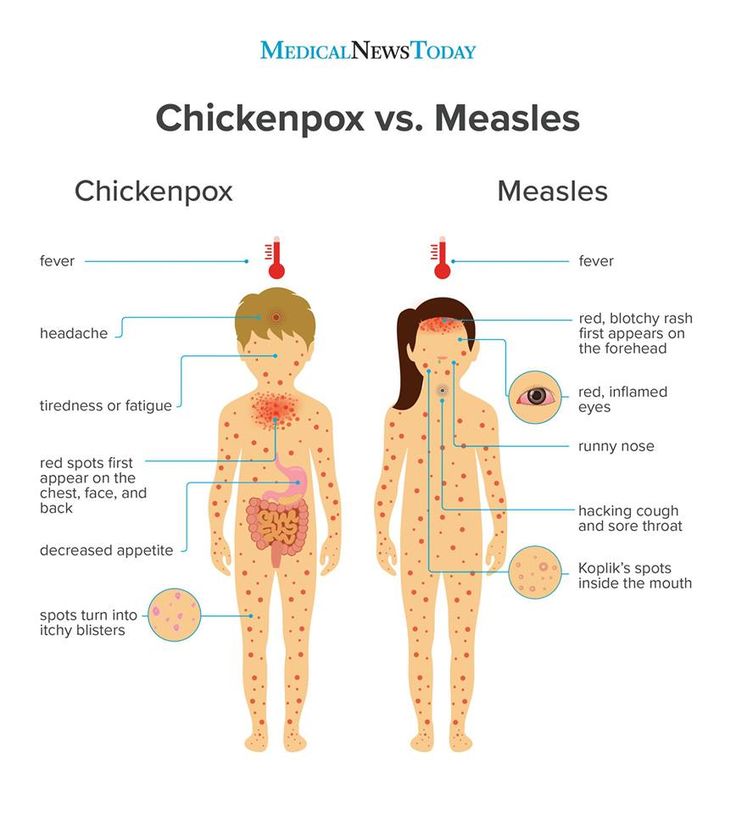

However, the rash does not always appears in cases of meningitis, and the word ‘rash’ itself may be misleading. Information and Support Officer Katherine Carter explains more.What is the meningitis rash?Meningitis and septicaemia can be caused by many different bugs, including viruses and fungi, but most cases of severe meningitis and septicaemia are caused by bacteria. Meningococcal bacteria in particular are the most common cause of the meningitis rash.

These bacteria can be very common and are mostly harmless, but in some people this bacteria invade the body via the back of the nose and throat, causing severe illness and even death. Sadly we don’t yet understand why some people get ill from a bacteria that is harmless to most of us.

Once the bacteria have invaded the back of the nose and throat, they travel through the bloodstream. As this happens, the bacteria rapidly multiply and produce toxins which travel around the body causing damage to blood vessels and organs. As the blood vessels get damaged, blood starts to ‘leak’ into the surrounding tissue, often causing what looks like a ‘rash’ to appear on the skin. However, this does not always appear.

As the blood vessels get damaged, blood starts to ‘leak’ into the surrounding tissue, often causing what looks like a ‘rash’ to appear on the skin. However, this does not always appear.

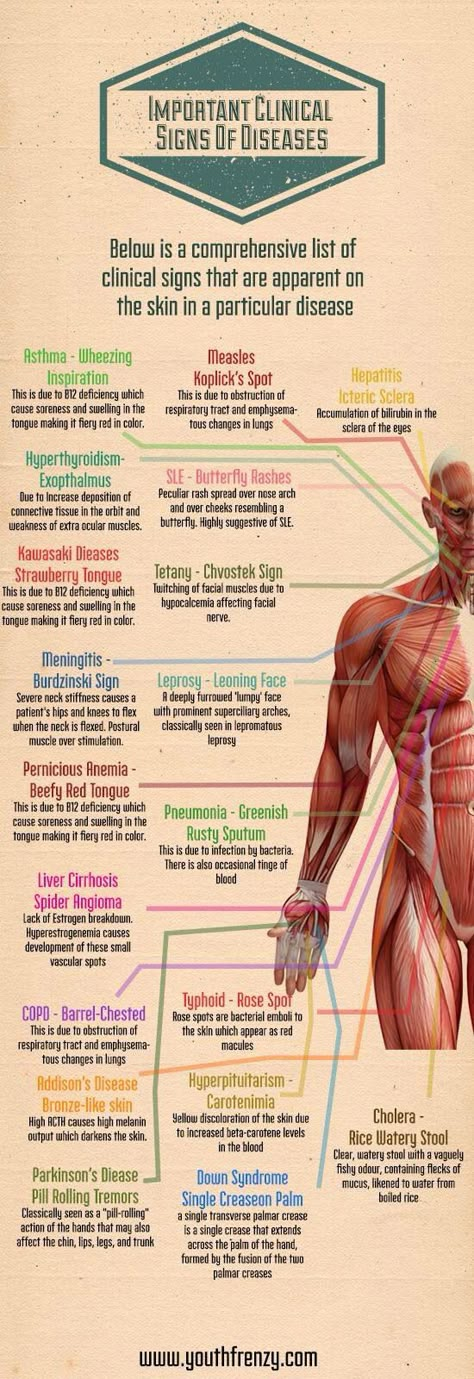

This rash can be one of the clearest and most specific signs of meningococcal meningitis and septicaemia to recognise – hence why you have probably heard of it. However, meningococcal rashes can be extremely diverse, and look different on different skin types. The rate of progression can also vary greatly.

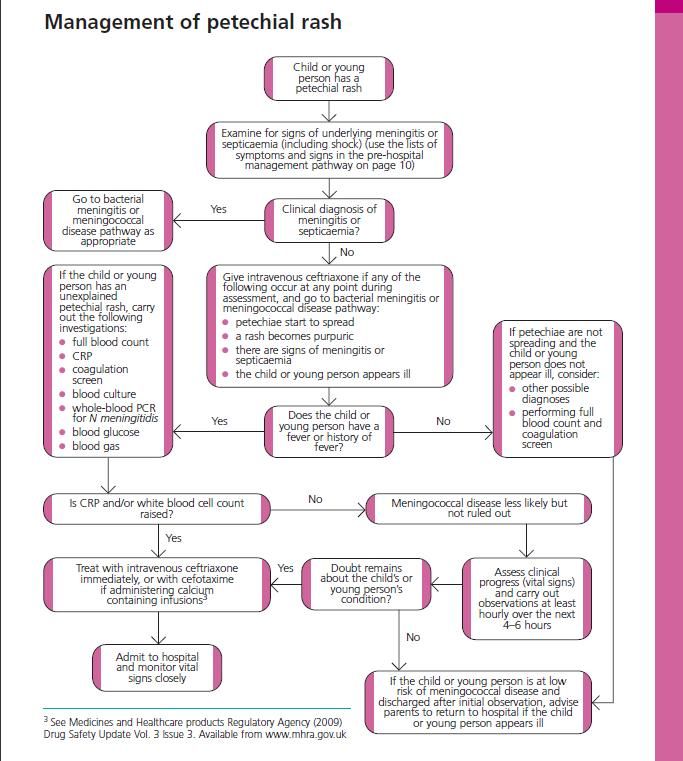

- A petechial rash looks like pin-prick red or purple spots on the skin, and can resemble flea bites.

- A purpuric rash looks more like bruising, showing up as reddish-purple areas on the skin.

A rapidly evolving petechial or purpuric ‘rash’ is a marker of very severe disease. As part of the MRF helpline team, I have had a parent describe a rapidly evolving rash as “like someone using a biro to draw all over the skin”. If you, or someone you know, appears to be suffering from a rash of this kind, please seek medical help immediately.

If you, or someone you know, appears to be suffering from a rash of this kind, please seek medical help immediately.

Isolated and dispersed pin-prick spots may first appear, so it is important to search the whole body for small petechiae, or red and purple spots. Petechiae are 1 to 2 mm in diameter and commonly appear in clusters in areas where pressure occurs from elastic in underwear, nappies or stocking. The rash can be more difficult to see on dark skin, but may be visible in paler areas, especially the soles of the feet, palms of the hands, abdomen, or on the inside of the eyelid or roof of the mouth.

The 'glass test' can be used to determine if a rash is or is not a symptom of meningitis.

What does the ‘glass test’ do?

Many people are familiar with the so-called “tumbler test” or “glass test”, whereby a glass or other clear surface is pressed onto the rash. If it disappears when pressed, this is known as a blanching rash. The meningitis “rash” can start as a blanching rash, but nearly always develops into a non-blanching red, purple or brownish petechial rash or purpura, meaning it will not disappear when pressed.

The meningitis “rash” can start as a blanching rash, but nearly always develops into a non-blanching red, purple or brownish petechial rash or purpura, meaning it will not disappear when pressed.

In response to the blood vessels leaking as the disease progresses, the body produces an overwhelming clotting response, which stops oxygen from reaching the extremities. This results in extensive purpuric areas, usually called ‘purpura fulminans’, which look like large bruises over the skin and can be very dark in colour.

The extremities are normally worst affected: often the feet and hands (but can extend over a whole arm or leg) and sometimes the ears, nose or lip. Devastatingly, as the extremities become starved of oxygen, they can become blackened which can lead to scarring and amputation.

What should I do if someone has lots of other meningitis symptoms, but no rash?Most patients with overwhelming meningococcal septicaemia develop a rash - it is one of the clearest and most important signs to recognise. However, in cases of meningitis the rash can be very scanty, blanching, atypical or even absent. When we talk about meningitis, we often think ‘rash’, but it is incredibly important to know that a rash won’t always appear.

However, in cases of meningitis the rash can be very scanty, blanching, atypical or even absent. When we talk about meningitis, we often think ‘rash’, but it is incredibly important to know that a rash won’t always appear.

Please remember that a very ill person needs medical help even if there are only a few spots, a rash that fades, or no rash at all. Trust your instincts, someone who has meningitis or septicaemia could become seriously ill very quickly. Get medical help immediately if you suspect meningitis or septicaemia – rash or no rash!

Meningococcal infection and its prevention

Meningococcal infection occupies an important place in infectious pathology and continues to be relevant for the Republic of Belarus

Meningococcal infection affects only people. The causative agent - meningococcus - is transmitted by airborne droplets, as well as, for example, with the flu. This microbe lives in the nasal cavity and can be transmitted from person to person by sneezing, coughing and even talking. This is a very serious disease that can develop among full health in a matter of hours and minutes. Children are more often ill, and generalized forms of the disease in 80% of cases occur in children under 2 years of age. Sometimes it is not possible to save a sick child. nine0003

This is a very serious disease that can develop among full health in a matter of hours and minutes. Children are more often ill, and generalized forms of the disease in 80% of cases occur in children under 2 years of age. Sometimes it is not possible to save a sick child. nine0003

The incubation period (the period from the moment meningococcus enters the body until the first signs of the disease appear) can last from several hours to 10 days. It all depends on the age and immune status of the patient.

The microbe itself is relatively unstable in the external environment. Outside of a person, he dies within 30 minutes. Fresh air, direct sunlight, ultraviolet radiation and disinfectants are especially detrimental to meningococcus.

This disease is characterized by a very acute onset, one might say in the midst of full health or after a slight runny nose. The temperature rises sharply to very high numbers, the child complains of a severe headache, at first a single, and then indomitable vomiting appears. Young children, who cannot yet complain, may have regurgitation, lethargy, refusal of the breast.

Young children, who cannot yet complain, may have regurgitation, lethargy, refusal of the breast.

The main symptom of the fulminant form and the appearance of an infectious agent in the blood (meningococcemia) is a rash on the child's skin. Rash with meningitis in children is one of the most characteristic symptoms. Initially, it may be morbilliform in nature - in the form of small red spots and papules. After some time, such a rash disappears and a hemorrhagic rash characteristic of meningococcal infection appears. Pinpoint hemorrhages appear first in the feet and legs of the child, and then spread higher to the trunk and other parts of the body. On pale skin, they resemble a picture of a starry sky. nine0003

- Note that meningococcal rash does not go away with pressure. If a rash appears on the face, eyelids, oral mucosa, auricles, or at the very beginning of the disease, this is an unfavorable factor and is typical for severe forms of the disease. The rash will increase.

And it is precisely in the presence of it that it is necessary to re-call the doctor, since the primary diagnosis before the rash can be set as an acute respiratory disease.

And it is precisely in the presence of it that it is necessary to re-call the doctor, since the primary diagnosis before the rash can be set as an acute respiratory disease.

This form of meningitis is dangerous because toxic-septic shock can develop due to hemorrhage in vital organs and, above all, in the adrenal glands. This shock causes death in 5-10 percent of patients. Therefore, the sooner parents seek medical help, and the sooner an appropriate diagnosis is made, the greater the chance of saving the patient. But in any case, hospitalization will be required and parents do not need to refuse it.

- What are the preventive measures for meningococcal disease? nine0016

You just need to carefully monitor the child's condition and, if warning signs appear, immediately seek medical help.

Oddly enough, the best prevention of meningitis is to strengthen the immune system - walks in the fresh air, rational nutrition and hardening. Equally important is personal hygiene. Thorough hand washing is very important to avoid infection. Teach your children to wash their hands frequently, especially before eating, after being in a public place, and after they have touched animals. nine0003

Thorough hand washing is very important to avoid infection. Teach your children to wash their hands frequently, especially before eating, after being in a public place, and after they have touched animals. nine0003

And most importantly, do not try to treat the baby yourself. In many ways, the results of the treatment of meningitis depend on the time that has passed since the onset of the first symptoms and the start of therapy. Only a specialist is able to correctly assess the situation and select treatment tactics.

Prevention of meningitis in children is primarily the prevention of airborne infection of the child. For children aged 1 to 3 years, the main danger is adults, and first of all, relatives. The most dangerous age for meningitis is up to 5 years, and in many respects the health of the child depends on his parents. If one of the older family members has a cough, runny nose, nasal congestion, think about the child - do not approach him, or put on a four-layer gauze bandage, covering both the nose and mouth. nine0003

nine0003

- Meningococcus is one of the weakest microbes, it dies very quickly outside the human body, especially from the action of ultraviolet rays of sunlight. Regular ventilation of the premises and sufficient sunlight can quickly get rid of these microbes in the air. Thus, you need to take care of good lighting in your child's room. The nursery should always be ventilated and washed clean.

Among other preventive measures, it is recommended to have fewer contacts during the period of the seasonal rise in the incidence of influenza and ARVI, to attend social events less frequently. All festive events (christenings) associated with the birth of a child must be carried out outside the apartment where he is. nine0003

And most importantly, don't try to treat yourself. The results of treatment of meningococcal infection largely depend on the time interval between the onset of the first symptoms and the start of therapy. Only a specialist can correctly assess the situation and choose the tactics of treatment.

If hospitalization is suggested by a health worker, do not refuse it, your child's life may depend on it.

A complete and balanced diet enriched with vitamins and microelements, playing sports, hardening the body also contribute to the body's resistance to infection. nine0016

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- Newsletter nine0205

- S

- B

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases nine0016

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data » nine0016

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Highlights "

- About WHO »

- General director

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee nine0016

- Main page/

- Media Center/

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Meningitis

Key Facts- Meningitis is a highly lethal disease with severe long-term complications.

- Meningitis remains one of the world's biggest health problems.

- Meningitis epidemics occur around the world, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

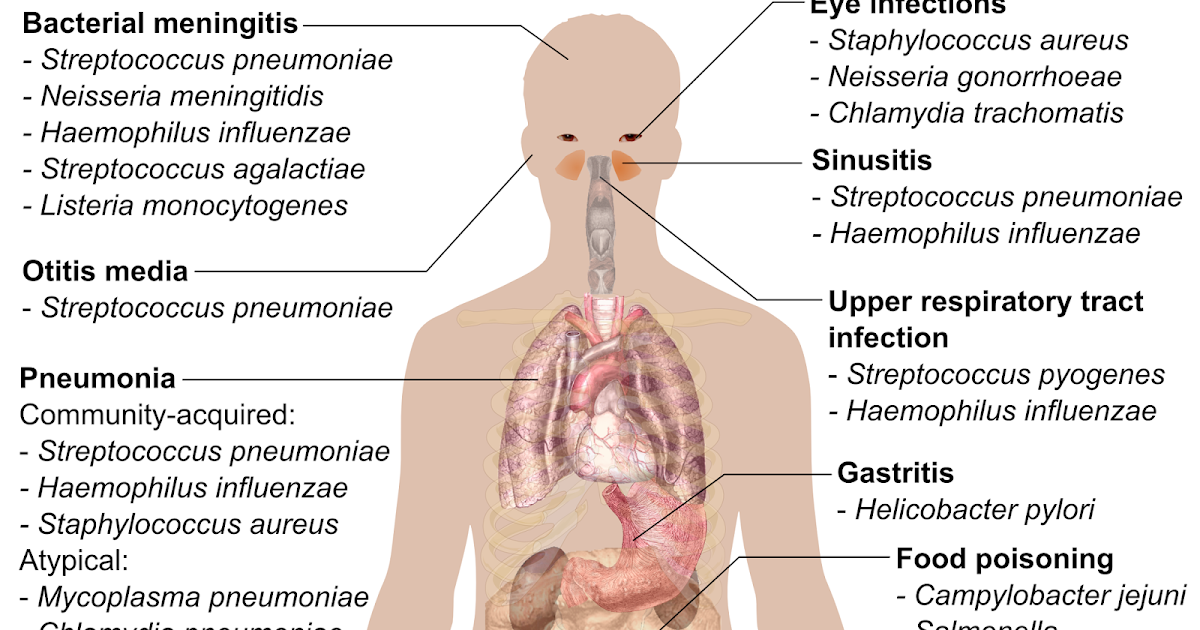

- Meningitis can be caused by many organisms, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites.

- Bacterial meningitis is of particular concern. Approximately one in ten people die from this type of meningitis, and one in five develop severe complications.

- Vaccines that are safe and inexpensive are the most effective way to provide long-term protection against disease. nine0046 , some viruses, such as enteroviruses and mumps, some fungi, especially c ryptococcus , as well as parasites, such as amoeba.

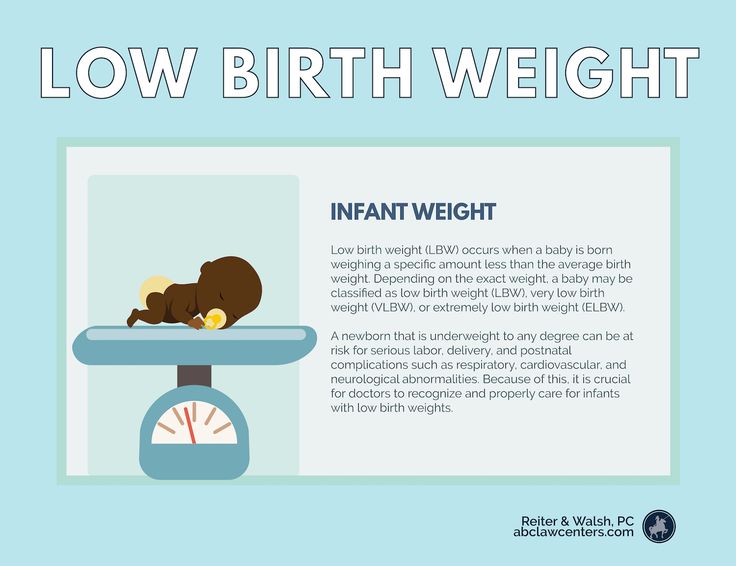

Who is at risk?Meningitis affects people of all ages, but young children are most at risk. Newborns are most at risk for group B streptococcus, young children for meningococcus, pneumococcus and haemophilus influenzae .

Adolescents and young adults are more at risk for meningococcal disease, while older people are at greater risk for pneumococcal disease.

Adolescents and young adults are more at risk for meningococcal disease, while older people are at greater risk for pneumococcal disease. People from all regions of the world are at risk of meningitis. The greatest burden of the disease occurs in sub-Saharan Africa, known as the "African meningitis belt", which is characterized by a particularly high risk of epidemics of meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis.

Risk is greatest in close contact settings, such as crowds, refugee camps, crowded living quarters, or student, military, and other professional environments. Immunodeficiency associated with HIV infection or complement deficiency, immunosuppression, active or passive smoking can also increase the risk of developing various types of meningitis. nine0003

Mechanisms of transmissionMechanisms of transmission depend on the type of pathogen. Most of the bacteria that cause meningitis, such as meningococcus, pneumococcus, and haemophilus influenzae, are present in the human nasopharyngeal mucosa.

They are spread by airborne droplets through respiratory and throat secretions. Group B streptococcus is often present in the intestinal or vaginal mucosa and can be passed from mother to child during childbirth. nine0003

They are spread by airborne droplets through respiratory and throat secretions. Group B streptococcus is often present in the intestinal or vaginal mucosa and can be passed from mother to child during childbirth. nine0003 Carriage of these organisms is usually harmless and leads to the development of immunity to infection, but in some cases an invasive bacterial infection can develop, causing meningitis and sepsis.

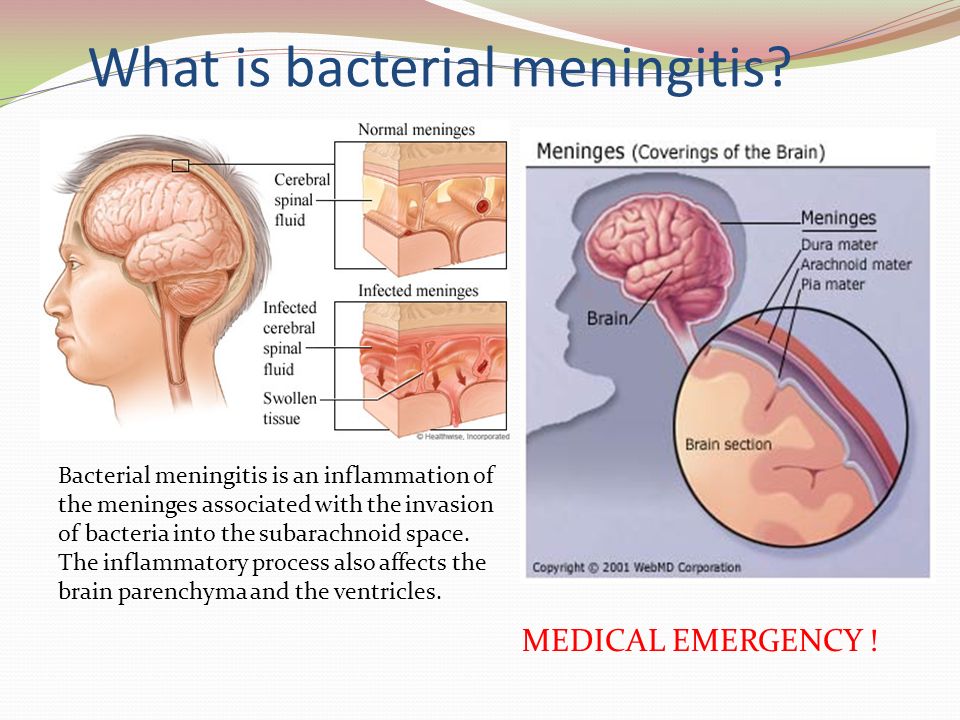

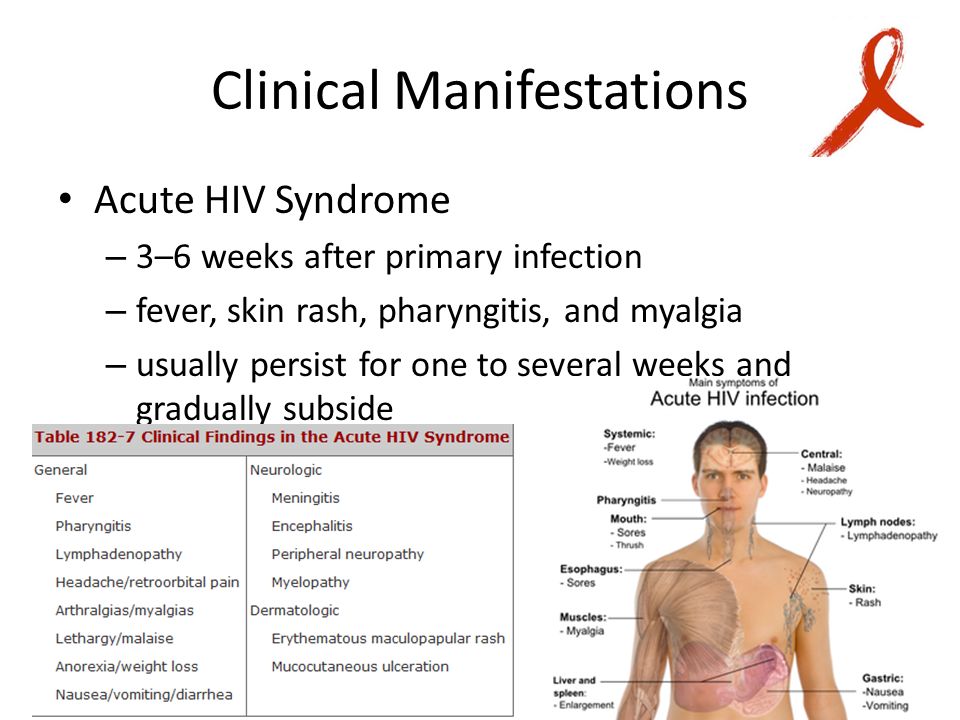

Clinical signs and symptomsDepending on the causative agent, the incubation period can vary and range from two to 10 days for bacterial meningitis. Because bacterial meningitis often accompanies sepsis, the clinical signs and symptoms described apply to both. pathologies. nine0003

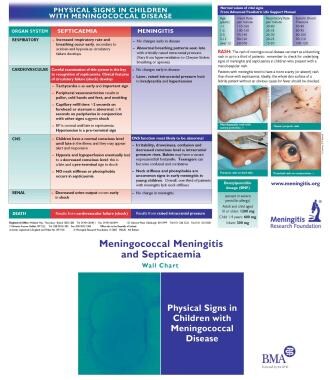

Clinical signs and symptoms:

- Strong headaches

- Distribution of the back of the head or pain in the neck

- Strong increase in body temperature

- Sveta -powered

- Snowstock, coma

- cold extremities

- vomiting

Infants may experience the following symptoms:

- decreased appetite

- drowsiness, lethargy, coma

- Irritability, crying when moving

- Difficult breathing, wheezing

- High body temperature

- Muscles of the back of the head

- swollen fontanel

- Typroble high screams

- vomit

PreventionThe most effective way to reduce the burden of disease and mitigate the negative public health impact of meningitis is to provide long-term protection against the disease through vaccination.

nine0003

nine0003 At risk for meningococcal meningitis and group B streptococcal meningitis, antibiotics are also used prophylactically. In epidemics of meningococcal meningitis, both vaccination and antibiotics are used.

1. VaccinationRegistered vaccines against meningococci, pneumococci and h aemophilus influenzae have been on the market for many years. Several different strains (also called serotypes or serogroups) of these bacteria are known, and vaccines are targeted to develop immunity to the most dangerous of them. Over time, great strides have been made in terms of coverage of different strains and availability of vaccines, but a universal vaccine against all these pathogens has not yet been developed. nine0003

Meningococci

There are 12 serogroups of meningococci, of which serogroups A, B, C, W, X and Y are the most common causative agents of meningitis.

There are three types of vaccines: and outbreak response:

- Such vaccines allow long-term immunity to be formed and also prevent the carriage of the infection, thereby reducing the spread of the infection and forming herd immunity.

nine0016

nine0016 - They are effective in protecting children under two years of age from getting sick.

- These vaccines are available in different forms:

- monovalent vaccines (serogroup A or C)

- quadrivalent vaccines (serogroups A, C, W, Y).

- combination vaccines (serogroup C meningococcus and h aemophilus influenzae type b)

- Protein-based vaccines against serogroup B meningococci. carriage and transmission of infection and thus do not lead to the formation of herd immunity. nine0016

- Polysaccharide vaccines are safe and effective in children and adults but provide little protection to infants. Formed immunity is short-lived, and herd immunity is not formed, since vaccination does not prevent carriage. These vaccines are still being used to control outbreaks, but are being replaced by conjugate vaccines.

Global public health response: eliminating epidemics of meningitis caused by group A meningococcus in the meningitis belt of Africa

Prior to the introduction of group A meningococcal conjugate vaccine in mass vaccination campaigns (since 2010) and its inclusion in the routine immunization schedule (since 2016) in countries in the African meningitis belt, this pathogen caused 80-85% all epidemics of meningitis.

As of April 2021, 24 out of 26 meningitis belt countries have conducted mass prevention campaigns among children aged 1-29 (nationally or in high-risk areas), and half of these, this vaccine has been included in national routine immunization schedules. Among the vaccinated population, the incidence of serogroup A meningitis decreased by more than 99%, and since 2017, no case of the disease caused by serogroup A meningococcus. In order to avoid a resurgence of epidemics, it is essential to continue to work on the inclusion of this vaccine in the routine immunization schedule and to maintain high vaccination coverage.

As of April 2021, 24 out of 26 meningitis belt countries have conducted mass prevention campaigns among children aged 1-29 (nationally or in high-risk areas), and half of these, this vaccine has been included in national routine immunization schedules. Among the vaccinated population, the incidence of serogroup A meningitis decreased by more than 99%, and since 2017, no case of the disease caused by serogroup A meningococcus. In order to avoid a resurgence of epidemics, it is essential to continue to work on the inclusion of this vaccine in the routine immunization schedule and to maintain high vaccination coverage. Sporadic cases and outbreaks of meningitis due to meningococcal serogroups other than serogroup B continue to be reported. Introduction of polyvalent meningococcal conjugate vaccines is a public health priority, the solution of which will allow to achieve the elimination of epidemics of bacterial meningitis in the African meningitis belt. nine0003

Pneumococcus

More than 97 pneumococcal serotypes are known, 23 of which cause most cases of pneumococcal meningitis.

- Conjugate vaccines are effective from 6 weeks of age to prevent meningitis and other severe pneumococcal infections and are recommended for infants and children under 5 years of age and, in some countries, adults over 65 years of age, as well as representatives of certain risk groups. Two conjugate vaccines are used that protect against pneumococcal serotypes 10 and 13. New conjugate vaccines designed to protect against more pneumococcal serotypes are currently currently under development or already approved for adult vaccination. Work continues on the development of protein-based vaccines. nine0016

- There is a polysaccharide vaccine designed to protect against 23 serotypes, but like other polysaccharide vaccines, it is considered less effective than conjugate vaccines. It is mainly used for vaccination against pneumonia among people over 65 years of age, as well as representatives of certain risk groups. It is not suitable for vaccinating children under 2 years of age and is less effective in preventing meningitis.

Haemophilus influenzae

There are 6 known serotypes haemophilus influenzae , of which serotype b is the main causative agent of meningitis.

- There are conjugate vaccines that provide specific immunity to h aemophilus influenzae serotype b (Hib). They are highly effective in preventing Hib disease and are recommended for inclusion in schedules of routine vaccinations for newborns.

Group B streptococcus

10 serotypes of group B streptococci are known, of which streptococci types 1a, 1b, II, III, IV and V are the most common causative agents of meningitis. In mothers and newborns.

2. Antibiotic prophylaxis (chemoprophylaxis)

Meningococci

Prompt administration of antibiotics to close contacts of people with meningococcal disease reduces the risk of transmission. Outside the African meningitis belt, chemoprophylaxis is recommended for family members of patients in close contact with them. In the countries of the meningitis belt, it is recommended to prescribe chemoprophylaxis to persons who had close contacts with patients in the absence of an epidemic. The drug of choice is ciprofloxacin; as an alternative ceftriaxone is given. nine0003

In the countries of the meningitis belt, it is recommended to prescribe chemoprophylaxis to persons who had close contacts with patients in the absence of an epidemic. The drug of choice is ciprofloxacin; as an alternative ceftriaxone is given. nine0003

Group B streptococcus

Many countries recommend screening mothers whose children are at risk for group B streptococcus. group B infections in newborns, mothers at risk during childbirth are given penicillin intravenously.

Diagnosis

Meningitis is initially diagnosed by clinical examination followed by lumbar puncture. In some cases, bacteria can be seen in the cerebrospinal fluid under a microscope. Diagnosis is supported or confirmed culture of cerebrospinal fluid or blood samples, rapid tests, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. To select the right infection control measures, it is important to identify the serogroup of the pathogen and to test for its sensitivity to antibiotics. Molecular typing and whole genome sequencing can reveal more differences between strains and provide valuable information for making decisions about the necessary anti-epidemic drugs. events. nine0003

Molecular typing and whole genome sequencing can reveal more differences between strains and provide valuable information for making decisions about the necessary anti-epidemic drugs. events. nine0003

Treatment

Meningitis without adequate treatment is fatal in about half of patients and should therefore always be considered an emergency. All patients with meningitis are hospitalized. Usually within 24 hours of starting treatment isolation of patients is not recommended.

In bacterial meningitis, treatment with appropriate antibiotics should be started as soon as possible. Ideally, a lumbar puncture should be performed before starting a course of antibiotics, as antibiotics can make culture difficult. research of cerebrospinal fluid. However, it is also possible to determine the type of pathogen by examining a patient's blood sample, and prompt initiation of treatment remains a priority. A wide range of antibiotics are used to treat meningitis. including penicillin, ampicillin and ceftriaxone. During epidemics of meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis, ceftriaxone is the drug of choice. nine0003

including penicillin, ampicillin and ceftriaxone. During epidemics of meningococcal and pneumococcal meningitis, ceftriaxone is the drug of choice. nine0003

Complications and consequences of the disease

One in five patients with bacterial meningitis may experience long-term consequences of the disease. These include hearing loss, seizures, weakness in the limbs, visual impairment, speech impairment, memory impairment, communication difficulties, and scars and consequences of amputation of limbs in case of sepsis.

Support and follow-up

The consequences of meningitis can have a tremendous negative impact on a person's life, family and community, both financially and emotionally. Sometimes complications such as deafness, learning difficulties, or behavioral problems are not recognized by parents, guardians or healthcare professionals and therefore remain untreated. nine0003

The consequences of previous meningitis often require long-term treatment. The permanent psychosocial impact of disability acquired as a result of meningitis may create a need in patients for medical care, assistance in the field of education, as well as social and human rights support. Despite the heavy burden of the consequences of meningitis on patients, their families and communities, access to services and support for these conditions is often inadequate, especially in low and middle income countries. Persons with disabilities due to previous meningitis and their families should be encouraged to seek services and advice from local and national disability societies and other organizations disability-oriented, where they can be given life-saving counseling on their rights, economic opportunities and social life so that people who become disabled due to meningitis can live a fulfilling life. nine0003

The permanent psychosocial impact of disability acquired as a result of meningitis may create a need in patients for medical care, assistance in the field of education, as well as social and human rights support. Despite the heavy burden of the consequences of meningitis on patients, their families and communities, access to services and support for these conditions is often inadequate, especially in low and middle income countries. Persons with disabilities due to previous meningitis and their families should be encouraged to seek services and advice from local and national disability societies and other organizations disability-oriented, where they can be given life-saving counseling on their rights, economic opportunities and social life so that people who become disabled due to meningitis can live a fulfilling life. nine0003

Surveillance

Surveillance, from case detection to investigation and laboratory confirmation, is essential to successful control of meningococcal meningitis. The main objectives of surveillance are:

The main objectives of surveillance are:

- detection and confirmation of disease outbreaks;

- monitoring of incidence trends, including the distribution and evolution of serogroups and serotypes;

- disease burden assessment; nine0016

- monitoring of pathogen resistance to antibiotics;

- monitoring of circulation, distribution and evolution of individual strains;

- evaluating the effectiveness of meningitis control strategies, in particular vaccination programs.

WHO action

WHO, with the support of multiple partners, developed a global roadmap to achieve the 2030 meningitis targets. In 2020, the strategy was endorsed in the first-ever World Assembly resolution healthcare, dedicated to meningitis, and was unanimously supported by WHO Member States. nine0003

The roadmap sets out a global goal to make the world free of meningitis, with three ambitious goals:

- elimination of epidemics of bacterial meningitis;

- 50% reduction in vaccine-preventable bacterial meningitis cases and 70% mortality;

- Reduce the incidence of meningitis-related disability and improve the quality of life for people who have had any type of meningitis.

The roadmap outlines the overall plan to achieve these goals through concerted action in five interrelated areas:

- prevention and control of epidemics, focusing on developing new low-cost vaccines, achieving high immunization coverage, improving epidemic prevention and response strategies;

- diagnosis and treatment with a focus on rapid confirmation of diagnosis and optimal medical care;

- disease surveillance to inform decisions in the prevention and control of meningitis;

- care and support for survivors of meningitis, with a focus on early detection and increased access to care and support for complications of meningitis; nine0016

- advocacy and community outreach to raise awareness about meningitis, engage countries in the fight against the disease, and ensure people's right to prevention, treatment and aftercare.

As part of another related initiative, WHO, in consultation with Member States, is working on an intersectoral global action plan on epilepsy and other neurological disorders to address multiple challenges and gaps in areas of care and service for people with epilepsy and other neurological disorders worldwide. The protection of the rights of people with disabilities is also recognized and addressed in the WHO Global Action Plan on Disability, prepared in in line with the provisions of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), as well as in the landmark resolution on achieving the highest standard of health for people with disabilities adopted by the 74th World Health Assembly. nine0003

The protection of the rights of people with disabilities is also recognized and addressed in the WHO Global Action Plan on Disability, prepared in in line with the provisions of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), as well as in the landmark resolution on achieving the highest standard of health for people with disabilities adopted by the 74th World Health Assembly. nine0003

Although the meningitis roadmap focuses on all types of meningitis, it primarily focuses on the main causative agents of acute bacterial meningitis (meningococcus, pneumococcus, haemophilus influenzae and group B streptococcus). In 2019, these bacteria were responsible for more than half of the 250,000 deaths from all forms of meningitis. They are also the causative agents of other serious diseases such as sepsis and pneumonia. For each of these pathogens infections, vaccines either already exist or, as in the case of group B streptococcus, are expected in the coming years.