Chlamydia test pregnancy

Screening for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea During Pregnancy: A Health Technology Assessment - CADTH Report / Project in Briefs

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

CADTH Report / Project in Briefs [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2011-.

CADTH Report / Project in Briefs [Internet].

Show details

- Contents

Search term

Created: November 2018.

Key Messages

Compared with other screening strategies, universal chlamydia and gonorrhea screening at entry into prenatal care plus at another time during pregnancy, appears to result in the highest number of new infections and reinfections being detected, which could lead to better health outcomes.

It is unclear which specimen type — urine, endocervical, or vaginal — offers better chlamydia and gonorrhea detection rates.

The cost-effectiveness of a screening program depends on:

- ◦

whether or not the health outcomes of, and associated costs related to, the pregnant person and the infant are considered only during the pregnancy and the postpartum period, and not beyond this time, in which case all screening programs are unlikely to be cost-effective

- ◦

whether or not the general population is at high risk of infection, the cost of pediatric infection treatment is high, or chlamydia or gonorrhea infections cause adverse pregnancy outcomes (an association that is currently unclear), in which case universal screening could be a cost-effective strategy

- ◦

whether or not infection consequences such as pelvic inflammatory disease and infant blindness during the lifetime of the pregnant person and the infant are considered, in which case universal screening in both the first and third trimesters could also be a cost-effective strategy.

Universal screening could help minimize stigma and discrimination, and therefore improve screening compliance.

The clinical evidence was limited in quantity and quality, which resulted in limitations to the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Context

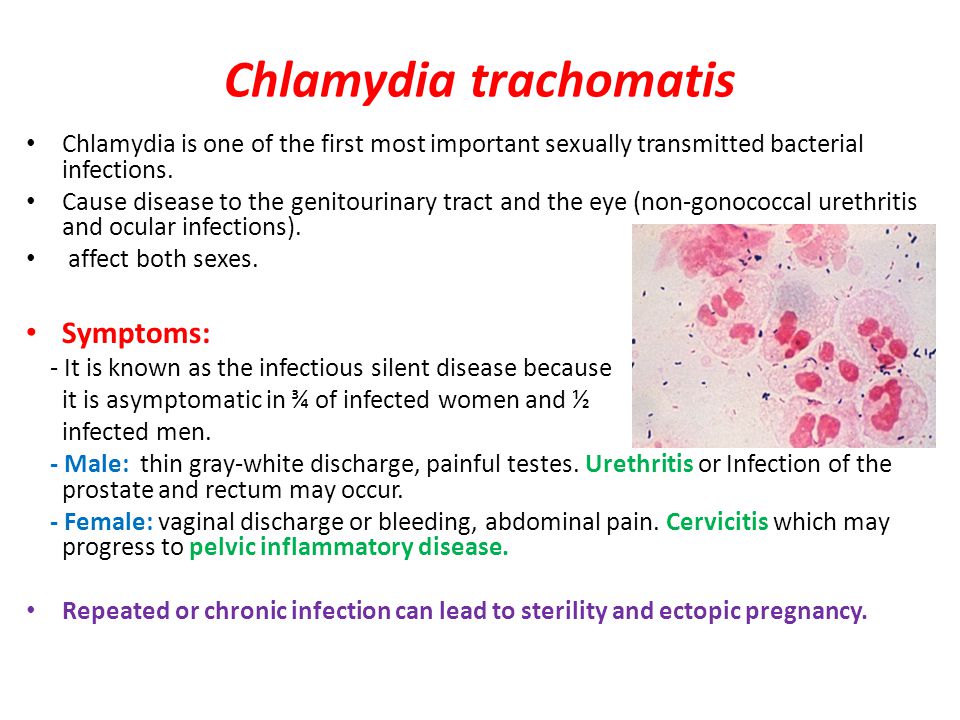

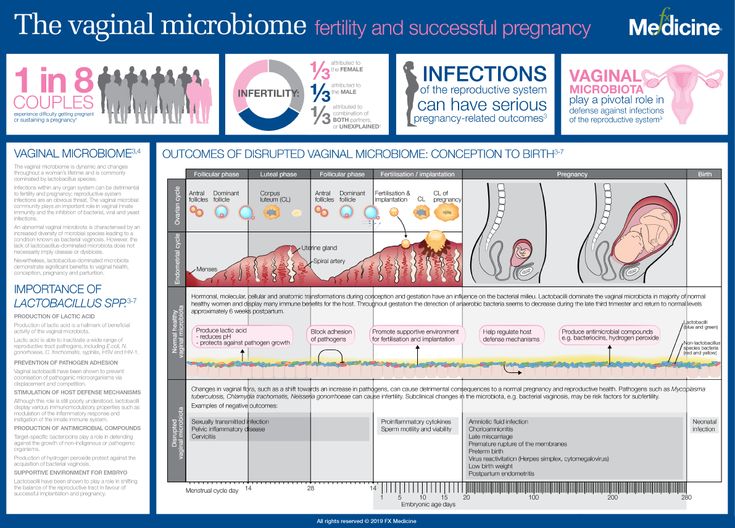

Chlamydia (which is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis) and gonorrhea (which is caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae) are the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infections in Canada. In pregnant persons, these infections can result in serious health complications if left untreated, including spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, infant death in the first week of life, preterm delivery, and low birth weight. Both chlamydia and gonorrhea can be transmitted to babies during childbirth, which can cause babies to later develop conjunctivitis (an eye infection) in the case of gonorrhea, and conjunctivitis and/ or pneumonia in the case of chlamydia.

Technology

Screening pregnant persons for chlamydia and gonorrhea ensures that the infection, if present, can be treated before it causes health risks to the parent and the baby. There are many potential approaches to screening: different screening tests can be used (e.g., a variety of different nucleic acid amplification tests or a cell culture test) and different specimens can be used (i.e., a urine sample, or a vaginal or cervical swab). Screening can be provided universally to all pregnant persons or in a targeted manner to those identified as being at high risk of infection. And screening can be provided once or multiple times during pregnancy and at different times during pregnancy.

There are many potential approaches to screening: different screening tests can be used (e.g., a variety of different nucleic acid amplification tests or a cell culture test) and different specimens can be used (i.e., a urine sample, or a vaginal or cervical swab). Screening can be provided universally to all pregnant persons or in a targeted manner to those identified as being at high risk of infection. And screening can be provided once or multiple times during pregnancy and at different times during pregnancy.

Issue

The rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea infection are rising despite numerous prevention and treatment strategies. An assessment of the clinical effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, and perspectives and experiences of pregnant persons, their partners, and health care providers will help provide guidance on the optimal approach to screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea during pregnancy.

Methods

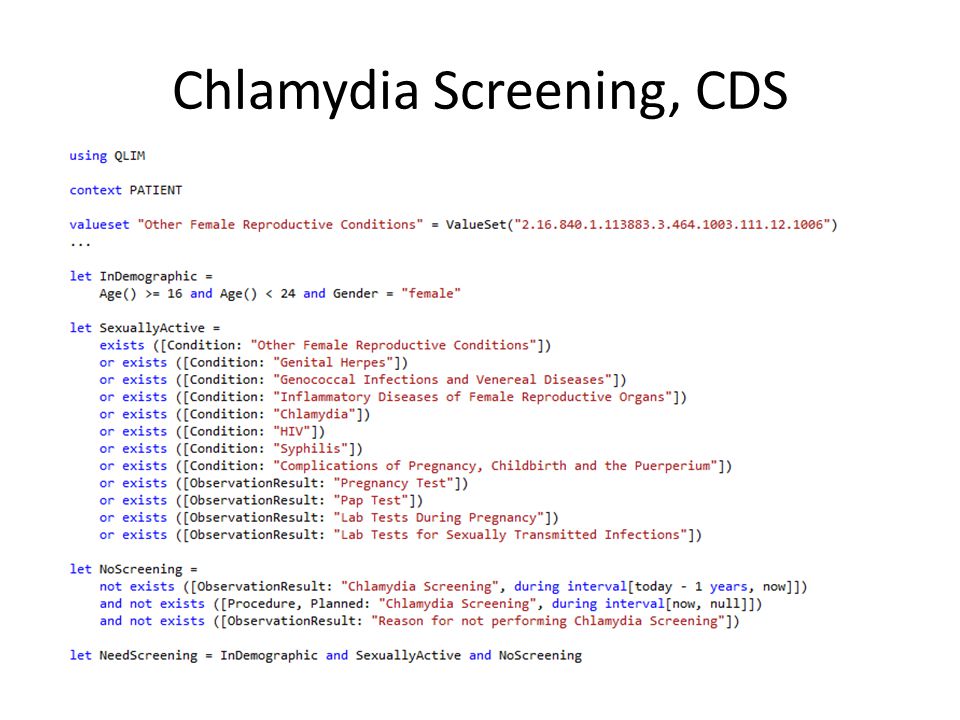

CADTH conducted a systematic review of comparative clinical studies on the detection yield, clinical utility, and harms of different screening strategies for detecting chlamydia and/or gonorrhea during pregnancy. An economic analysis was also undertaken to determine the most cost-effective screening strategy in pregnant persons and their infants up to the postpartum period. A review of the perspectives and experiences of pregnant persons, their partners, and their health care providers when it comes to undergoing screening for sexually transmitted infections was also conducted.

An economic analysis was also undertaken to determine the most cost-effective screening strategy in pregnant persons and their infants up to the postpartum period. A review of the perspectives and experiences of pregnant persons, their partners, and their health care providers when it comes to undergoing screening for sexually transmitted infections was also conducted.

Results

Clinical Review

The clinical review suggests that universal chlamydia and gonorrhea screening strategies are likely to be more effective than targeted ones (i.e., based on age or other risk factors) because pregnant persons who are infected will not be identified and treated if they do not meet targeted screening criteria. It also suggests, overall, that providing a second universal screening test during pregnancy, in addition to one given at the initial prenatal care visit, might result in more infections being detected compared with screening only at entry into prenatal care. This is because the second screening test may detect a new infection or reinfection. It is not clear if early detection and treatment improves neonatal outcomes.

It is not clear if early detection and treatment improves neonatal outcomes.

Economic Review

Universal screening in the first and third trimesters appears to be the costliest strategy, although it could generate the most health benefit. The cost-effectiveness is dependent on the potential magnitude of harm from undiagnosed chlamydia and gonorrhea infections, and the costs associated with managing these outcomes. If the outcomes only up to the postpartum period are considered, the clinical benefit of universal screening would be considered marginal. But when outcomes over a lifetime time horizon are considered, universal screening could be the most cost-effective screening strategy, given the additional benefit that could be realized for the pregnant person, the person’s child, and even to the person’s partner over the longer time period.

Patients’ Preferences and Experiences

The review of the preferences and experiences of patients found that a universal approach to chlamydia and gonorrhea screening may be perceived as less stigmatizing and discriminatory, and might therefore improve participation rates in screening programs.

DISCLAIMER: This material is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose; this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or for the application of professional judgment in any decision-making process. Users may use this document at their own risk. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or currency of the contents of this document. CADTH is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use of this document and is not responsible for any third-party materials contained or referred to herein. Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Health Canada, Canada’s provincial or territorial governments, other CADTH funders, or any third-party supplier of information.

This document is subject to copyright and other intellectual property rights and may only be used for non-commercial, personal use or private research and study.

This document is subject to copyright and other intellectual property rights and may only be used for non-commercial, personal use or private research and study.

Copyright © 2011- CADTH.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Bookshelf ID: NBK538784PMID: 30883074

Contents

- PubReader

- Print View

- Cite this Page

- PDF version of this page (267K)

In this Page

- Context

- Technology

- Issue

- Methods

- Results

Similar articles in PubMed

- Risk assessment and other screening options for gonorrhoea and chlamydial infections in women attending rural Tanzanian antenatal clinics.

[Bull World Health Organ. 1995]

[Bull World Health Organ. 1995] - Review Screening for Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae During Pregnancy: A Health Technology Assessment[ 2018]

- Cost-effectiveness of universal screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in US jails.[J Urban Health. 2004]

- Review Screening for Chlamydial Infection[ 2001]

- Provider barriers prevent recommended sexually transmitted disease screening of HIV-infected men who have sex with men.[Sex Transm Dis. 2014]

See reviews...See all...

Recent Activity

ClearTurn OffTurn On

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

See more...

Screening for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea During Pregnancy: A Health Technology Assessment - CADTH Report / Project in Briefs

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

CADTH Report / Project in Briefs [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2011-.

CADTH Report / Project in Briefs [Internet].

Show details

- Contents

Search term

Created: November 2018.

Key Messages

Compared with other screening strategies, universal chlamydia and gonorrhea screening at entry into prenatal care plus at another time during pregnancy, appears to result in the highest number of new infections and reinfections being detected, which could lead to better health outcomes.

It is unclear which specimen type — urine, endocervical, or vaginal — offers better chlamydia and gonorrhea detection rates.

The cost-effectiveness of a screening program depends on:

- ◦

whether or not the health outcomes of, and associated costs related to, the pregnant person and the infant are considered only during the pregnancy and the postpartum period, and not beyond this time, in which case all screening programs are unlikely to be cost-effective

- ◦

whether or not the general population is at high risk of infection, the cost of pediatric infection treatment is high, or chlamydia or gonorrhea infections cause adverse pregnancy outcomes (an association that is currently unclear), in which case universal screening could be a cost-effective strategy

- ◦

whether or not infection consequences such as pelvic inflammatory disease and infant blindness during the lifetime of the pregnant person and the infant are considered, in which case universal screening in both the first and third trimesters could also be a cost-effective strategy.

Universal screening could help minimize stigma and discrimination, and therefore improve screening compliance.

The clinical evidence was limited in quantity and quality, which resulted in limitations to the cost-effectiveness analysis.

Context

Chlamydia (which is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis) and gonorrhea (which is caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae) are the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infections in Canada. In pregnant persons, these infections can result in serious health complications if left untreated, including spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, infant death in the first week of life, preterm delivery, and low birth weight. Both chlamydia and gonorrhea can be transmitted to babies during childbirth, which can cause babies to later develop conjunctivitis (an eye infection) in the case of gonorrhea, and conjunctivitis and/ or pneumonia in the case of chlamydia.

Technology

Screening pregnant persons for chlamydia and gonorrhea ensures that the infection, if present, can be treated before it causes health risks to the parent and the baby. There are many potential approaches to screening: different screening tests can be used (e.g., a variety of different nucleic acid amplification tests or a cell culture test) and different specimens can be used (i.e., a urine sample, or a vaginal or cervical swab). Screening can be provided universally to all pregnant persons or in a targeted manner to those identified as being at high risk of infection. And screening can be provided once or multiple times during pregnancy and at different times during pregnancy.

There are many potential approaches to screening: different screening tests can be used (e.g., a variety of different nucleic acid amplification tests or a cell culture test) and different specimens can be used (i.e., a urine sample, or a vaginal or cervical swab). Screening can be provided universally to all pregnant persons or in a targeted manner to those identified as being at high risk of infection. And screening can be provided once or multiple times during pregnancy and at different times during pregnancy.

Issue

The rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea infection are rising despite numerous prevention and treatment strategies. An assessment of the clinical effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, and perspectives and experiences of pregnant persons, their partners, and health care providers will help provide guidance on the optimal approach to screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea during pregnancy.

Methods

CADTH conducted a systematic review of comparative clinical studies on the detection yield, clinical utility, and harms of different screening strategies for detecting chlamydia and/or gonorrhea during pregnancy. An economic analysis was also undertaken to determine the most cost-effective screening strategy in pregnant persons and their infants up to the postpartum period. A review of the perspectives and experiences of pregnant persons, their partners, and their health care providers when it comes to undergoing screening for sexually transmitted infections was also conducted.

An economic analysis was also undertaken to determine the most cost-effective screening strategy in pregnant persons and their infants up to the postpartum period. A review of the perspectives and experiences of pregnant persons, their partners, and their health care providers when it comes to undergoing screening for sexually transmitted infections was also conducted.

Results

Clinical Review

The clinical review suggests that universal chlamydia and gonorrhea screening strategies are likely to be more effective than targeted ones (i.e., based on age or other risk factors) because pregnant persons who are infected will not be identified and treated if they do not meet targeted screening criteria. It also suggests, overall, that providing a second universal screening test during pregnancy, in addition to one given at the initial prenatal care visit, might result in more infections being detected compared with screening only at entry into prenatal care. This is because the second screening test may detect a new infection or reinfection. It is not clear if early detection and treatment improves neonatal outcomes.

It is not clear if early detection and treatment improves neonatal outcomes.

Economic Review

Universal screening in the first and third trimesters appears to be the costliest strategy, although it could generate the most health benefit. The cost-effectiveness is dependent on the potential magnitude of harm from undiagnosed chlamydia and gonorrhea infections, and the costs associated with managing these outcomes. If the outcomes only up to the postpartum period are considered, the clinical benefit of universal screening would be considered marginal. But when outcomes over a lifetime time horizon are considered, universal screening could be the most cost-effective screening strategy, given the additional benefit that could be realized for the pregnant person, the person’s child, and even to the person’s partner over the longer time period.

Patients’ Preferences and Experiences

The review of the preferences and experiences of patients found that a universal approach to chlamydia and gonorrhea screening may be perceived as less stigmatizing and discriminatory, and might therefore improve participation rates in screening programs.

DISCLAIMER: This material is made available for informational purposes only and no representations or warranties are made with respect to its fitness for any particular purpose; this document should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or for the application of professional judgment in any decision-making process. Users may use this document at their own risk. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, or currency of the contents of this document. CADTH is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or injury, loss, or damage arising from or relating to the use of this document and is not responsible for any third-party materials contained or referred to herein. Subject to the aforementioned limitations, the views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Health Canada, Canada’s provincial or territorial governments, other CADTH funders, or any third-party supplier of information.

This document is subject to copyright and other intellectual property rights and may only be used for non-commercial, personal use or private research and study.

This document is subject to copyright and other intellectual property rights and may only be used for non-commercial, personal use or private research and study.

Copyright © 2011- CADTH.

Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Bookshelf ID: NBK538784PMID: 30883074

Contents

- PubReader

- Print View

- Cite this Page

- PDF version of this page (267K)

In this Page

- Context

- Technology

- Issue

- Methods

- Results

Similar articles in PubMed

- Risk assessment and other screening options for gonorrhoea and chlamydial infections in women attending rural Tanzanian antenatal clinics.

[Bull World Health Organ. 1995]

[Bull World Health Organ. 1995] - Review Screening for Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhoeae During Pregnancy: A Health Technology Assessment[ 2018]

- Cost-effectiveness of universal screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in US jails.[J Urban Health. 2004]

- Review Screening for Chlamydial Infection[ 2001]

- Provider barriers prevent recommended sexually transmitted disease screening of HIV-infected men who have sex with men.[Sex Transm Dis. 2014]

See reviews...See all...

Recent Activity

ClearTurn OffTurn On

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

See more...

Chlamydia - KVD №2

What is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is a common sexually transmitted infection (STI). The disease is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis (Chlamydia trachomatis), which affects the female genital area and is the cause of non-gonococcal urethritis in men. Manifestations of chlamydia are usually minor or absent, but serious complications develop. Complications can cause irreparable damage to the body, including infertility - all this proceeds very secretly. nine0005

The disease is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis (Chlamydia trachomatis), which affects the female genital area and is the cause of non-gonococcal urethritis in men. Manifestations of chlamydia are usually minor or absent, but serious complications develop. Complications can cause irreparable damage to the body, including infertility - all this proceeds very secretly. nine0005

Chlamydia also causes penile discharge in infected men.

Chlamydia transmission routes

Chlamydia can be transmitted through:

- vaginal or anal contact with an infected partner;

- less common with oral sex;

- use of sex toys with an infected partner;

- infection of a newborn during childbirth from a sick mother.

Absolutely all sexually active people can get chlamydia. The greater the number of sexual partners, the greater the risk of infection. The risk of infection is especially high in girls, because their cervix is not fully formed. About 75% of new cases occur in women under 25 years of age. By the age of 30, approximately 50% of sexually active women have had chlamydia. In sexually active men, the risk of infection is highest between the ages of 20 and 24. nine0005

About 75% of new cases occur in women under 25 years of age. By the age of 30, approximately 50% of sexually active women have had chlamydia. In sexually active men, the risk of infection is highest between the ages of 20 and 24. nine0005

You cannot get chlamydia through kisses, hugs, dishes, baths, towels.

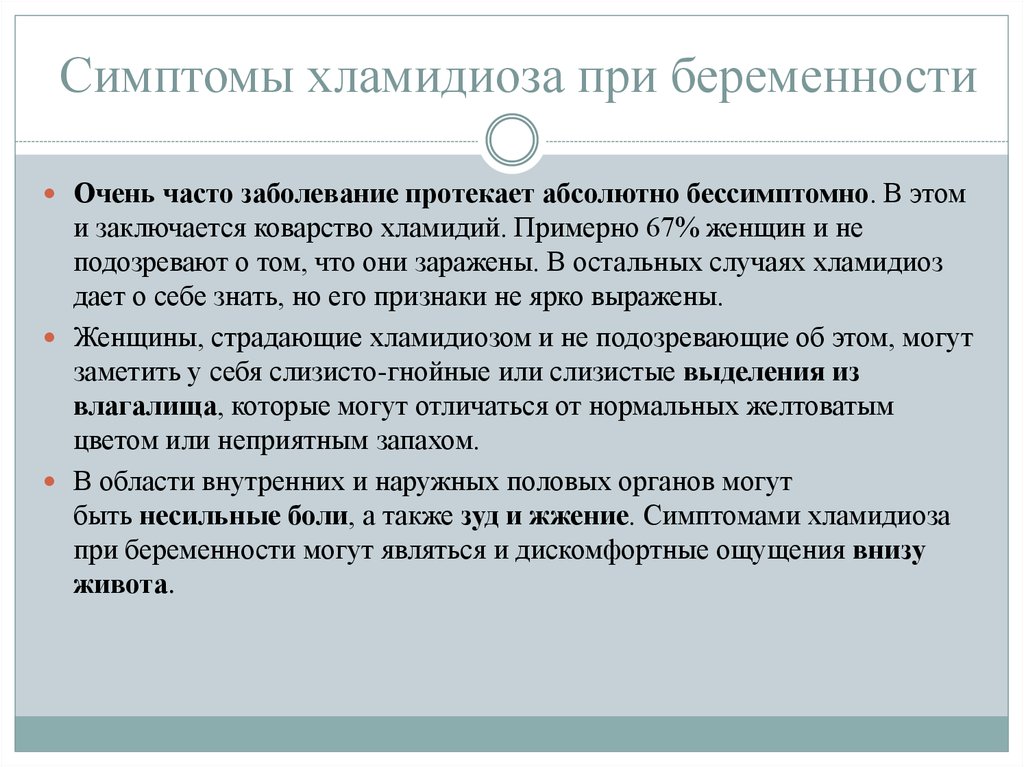

Manifestations of chlamydia

Chlamydia is very secretive. About 75% of infected women and 50% of infected men are asymptomatic. If manifestations of the disease develop, then this occurs approximately 1 to 3 weeks after infection.

In women, chlamydia first affects the cervix and urethra (urinary canal).

Manifestations:

- unusual vaginal discharge; nine0014

- pain or discomfort when urinating;

If the infection penetrates to the appendages, manifestations are possible:

- pain in the lower abdomen;

- pain in the lumbar region;

- nausea;

- slight increase in temperature;

- pain during intercourse or bleeding after it;

- bleeding between periods.

Symptoms in men:

- clear or cloudy discharge from the penis; nine0014

- pain or discomfort when urinating;

- there may be burning and itching in the area of the outlet of the urethra;

- rarely pain and/or swelling of the testicles.

Men or women who have anal sex with an infected partner can infect the rectum, resulting in inflammation, pain, discharge, or bleeding from the rectum.

Chlamydia can cause sore throat (pharyngitis) in men and women who have oral contact with an infected partner. nine0005

What complications can develop if chlamydia is not treated?

If the disease is not treated, serious short-term and persistent complications develop. Like the disease itself, complications often occur insidiously.

In women with untreated chlamydia, infection can spread from the urethra to the fallopian tubes (the tubes that carry the egg from the ovaries to the uterus) - this causes (in 40% of cases) the development of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID causes permanent damage to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and surrounding tissues. Chronic pelvic pain, infertility and ectopic pregnancy are the result of PID. nine0005

PID causes permanent damage to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and surrounding tissues. Chronic pelvic pain, infertility and ectopic pregnancy are the result of PID. nine0005

Women with chlamydia are more susceptible to HIV infection, the risk increases by almost 5 times.

To prevent serious consequences of chlamydia, annual chlamydia screening is required for all sexually active women 25 years of age and younger. An annual examination is necessary for women over 25 who are at risk (new sexual partner, multiple sexual partners). All pregnant women should be screened for chlamydia. nine0005

Complications of chlamydia are rare in men. The infection sometimes extends to the epididymis and causes pain, fever, and, rarely, male infertility (sterility).

Rarely, chlamydial infection can cause inflammation of the joints in combination with skin lesions, inflammation of the eyes and urinary tract - this is the so-called Reiter's syndrome.

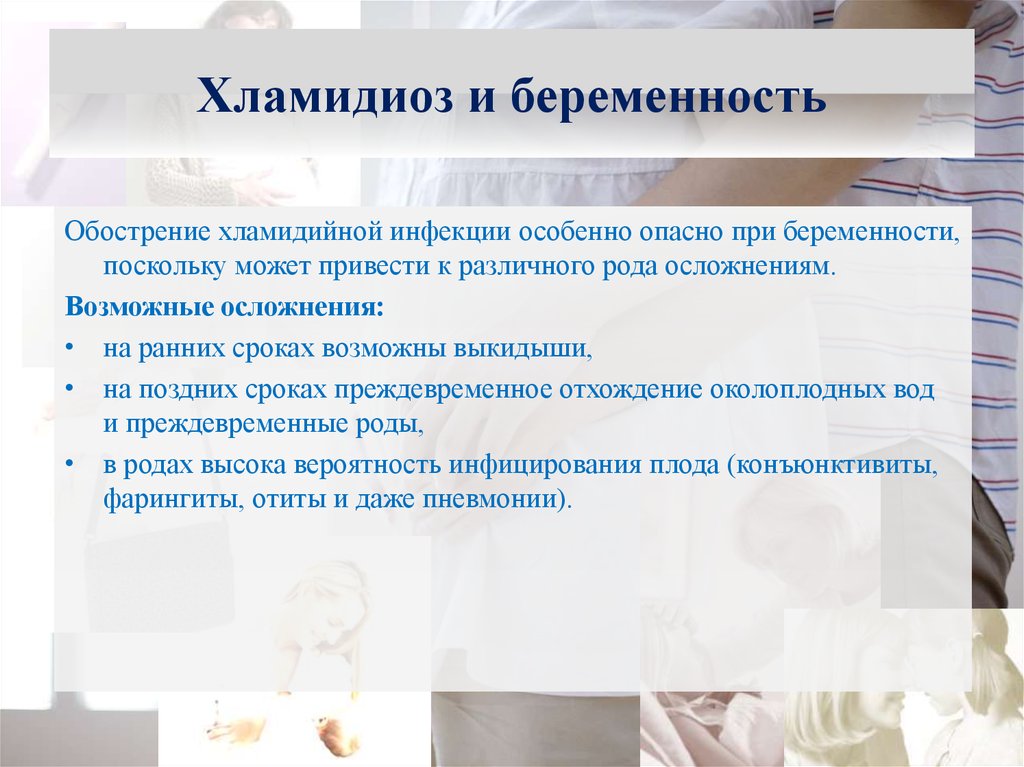

The effect of chlamydia on a pregnant woman and her child

Chlamydia in pregnant women increases the risk of miscarriage, premature detachment of the placenta. Newborns from infected mothers can get eye and lung infections. A lung infection (pneumonia) can be fatal to a newborn. nine0005

Newborns from infected mothers can get eye and lung infections. A lung infection (pneumonia) can be fatal to a newborn. nine0005

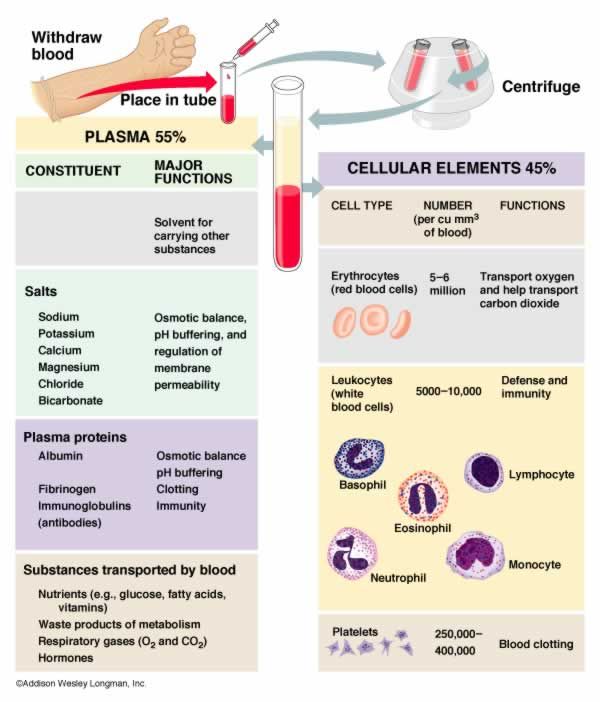

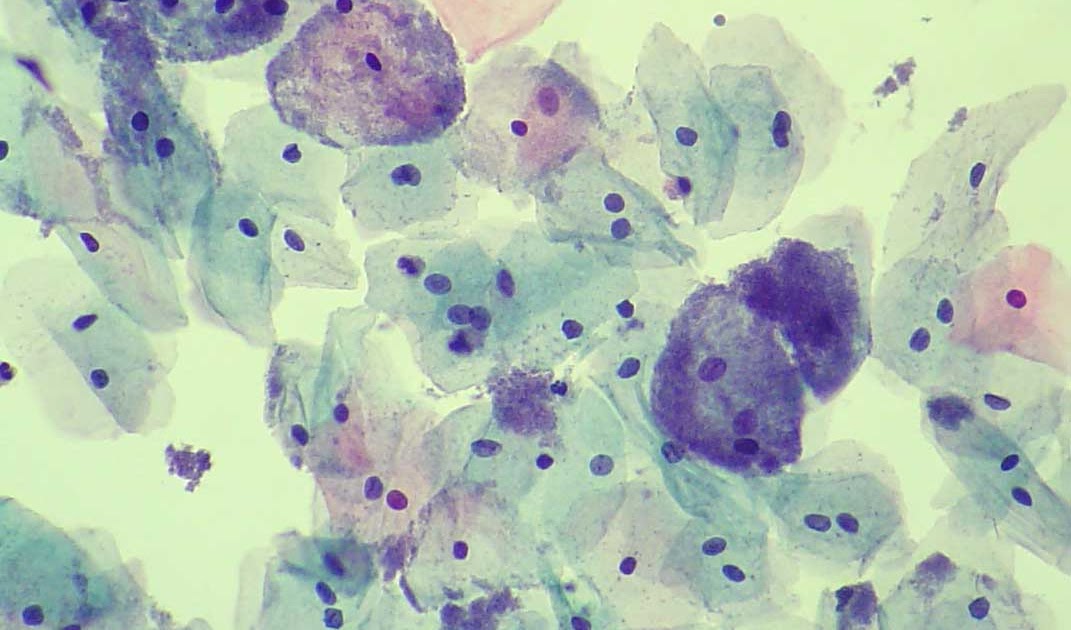

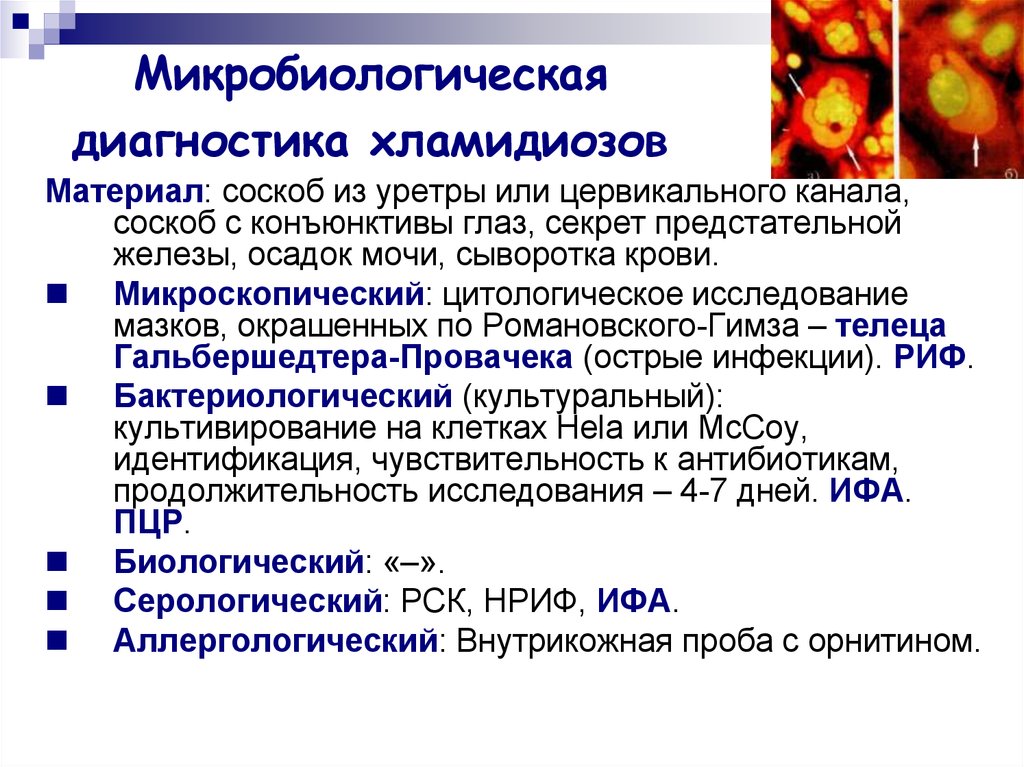

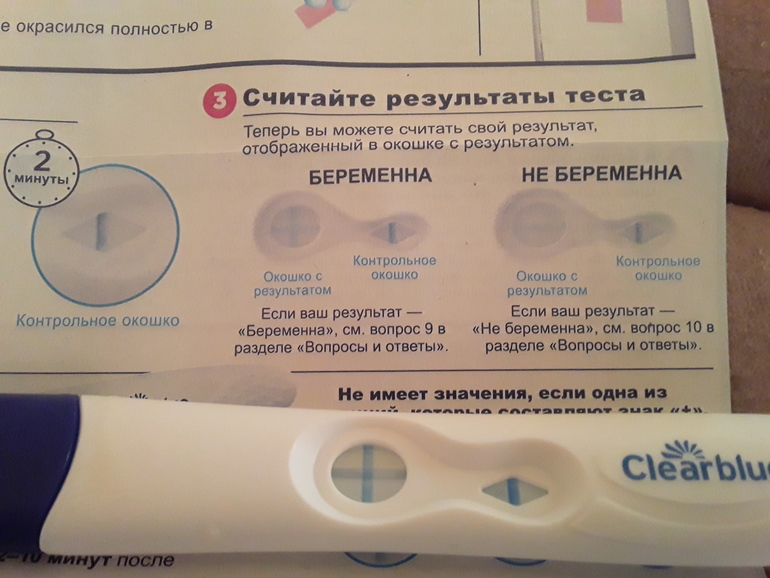

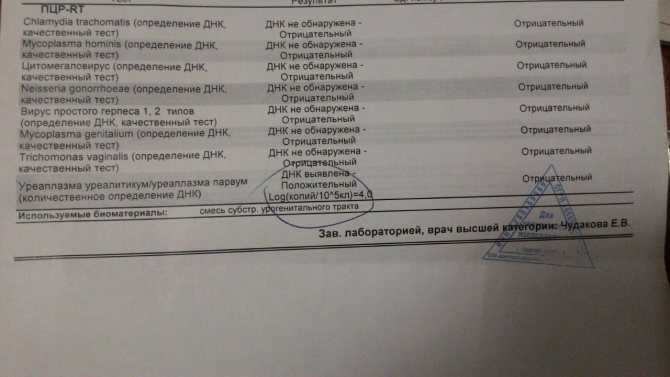

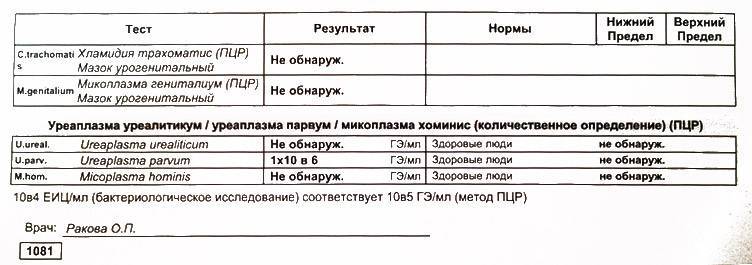

Diagnosis of chlamydia

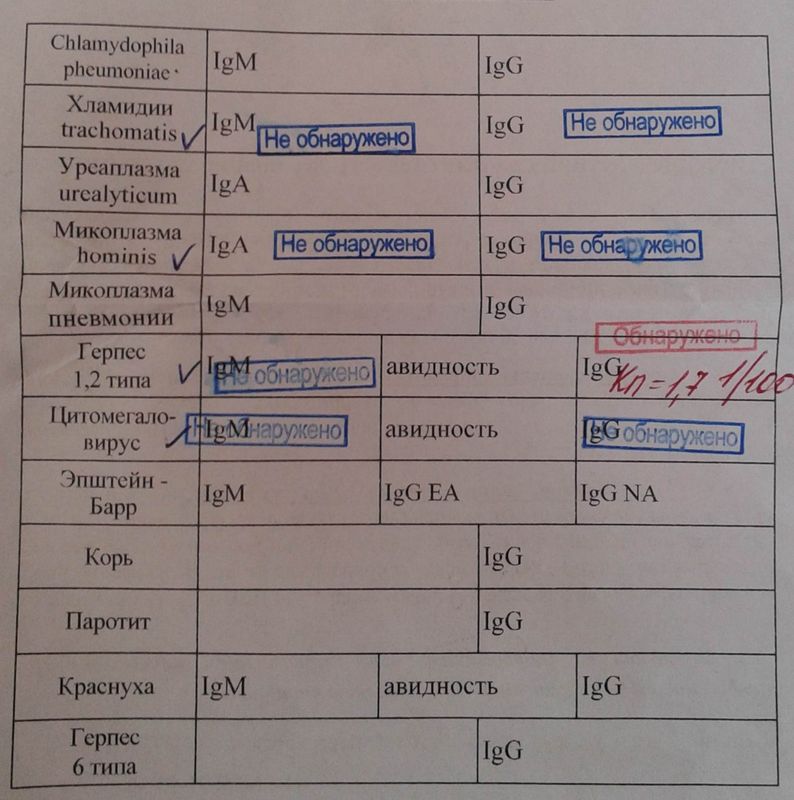

Diagnosis includes observation of the patient's clinical symptoms, testing for chlamydia smears from the cervix, scraping from the urinary canal, the first morning urine. Most often, the study is carried out by PCR (polymerase chain reaction). Swabs and scrapings may cause minor discomfort.

In addition, a blood test by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) for the presence of immunity to chlamydia is carried out, this auxiliary test often helps to establish an accurate diagnosis. nine0005

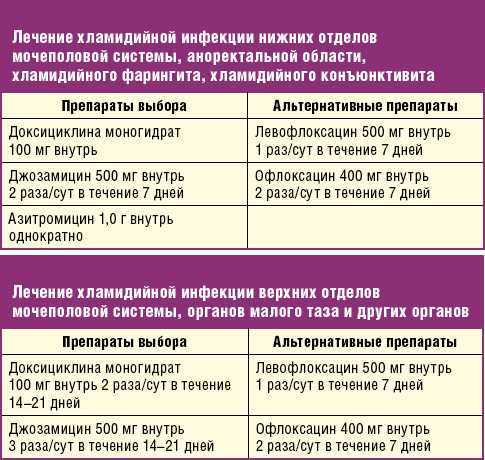

Treatment of chlamydia

Treatment of chlamydia is with oral antibiotics. To prevent re-infection, all sexual partners must be found, examined and treated. Patients with chlamydia should refrain from unprotected sex during treatment, otherwise it is possible to re-infect the sexual partner. Unfortunately, after successful treatment, re-infection with chlamydia is possible, since a strong immunity to this microorganism does not develop. Repeated infection of women with chlamydia leads to a significant increase in the risk of serious complications, including infertility. A re-examination is carried out 4 weeks after treatment. nine0005

Repeated infection of women with chlamydia leads to a significant increase in the risk of serious complications, including infertility. A re-examination is carried out 4 weeks after treatment. nine0005

Prevention of chlamydia

The best way to prevent sexually transmitted infections is through long-term sexual contact with one healthy sexual partner. Latex male condoms, when used correctly, drastically reduce the risk of transmission.

Annual chlamydia screening required for all sexually active women 25 years of age and younger. An annual examination is also necessary for women over 25 who are at risk (new sexual partner, multiple sexual partners). All pregnant women should be screened for chlamydia. nine0005

Any manifestations, such as pain or discomfort when urinating, unusual rash, discharge are a signal to stop sexual intercourse and immediately examine in a specialized clinic - KVD. If the patient is found to have chlamydia (or any other STI), he must inform his sexual partners so that they also undergo a full examination and appropriate treatment. This will reduce the risk of developing serious complications and prevent the possibility of re-infection. nine0005

This will reduce the risk of developing serious complications and prevent the possibility of re-infection. nine0005

Patients with chlamydia should refrain from unprotected sex during treatment, otherwise the sexual partner may be re-infected.

Chlamydia in women - Institute of Health

Urogenital chlamydia is a highly contagious (contagious) sexually transmitted infection. In Russia, more than 1.5 million people fall ill every year. Sexually active men and women aged 20-40 years are most often ill. Now this disease has increased among adolescents aged 13-17. The source of infection is persons with overt and latent disease. The infection is transmitted sexually and non-sexually (domestic), intrauterine and at birth. nine0005

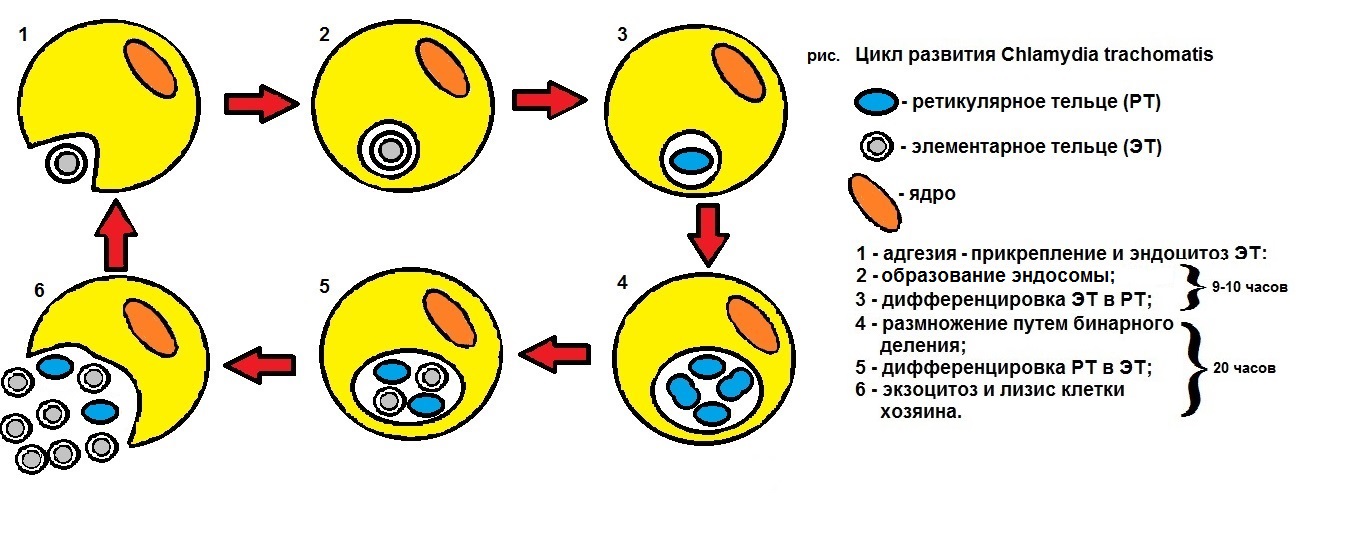

Features

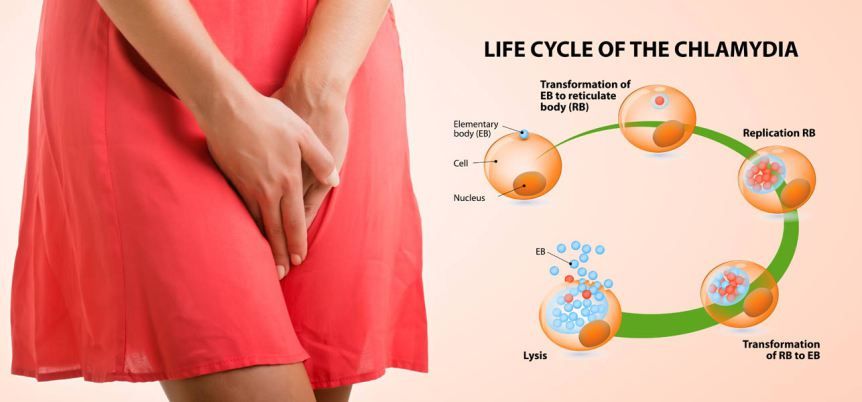

The causative agent of urogenital chlamydia is Chlamydia trachomatis (D-K serotypes). This parasite, incapable of life outside the body, is a gram-negative bacterium containing DNA and RNA. Chlamydia are capable of binary fission during reproduction, are sensitive to antibiotics. The incubation period is from 5-7 days to 3-6 weeks. Asymptomatic course is noted in 60-80% of cases.

The incubation period is from 5-7 days to 3-6 weeks. Asymptomatic course is noted in 60-80% of cases.

Symptoms

Clinical manifestations of chlamydia infection are diverse. The symptoms of the disease also depend on the state of the immune system, the localization of the lesion, the virulence of chlamydia. However, even with an asymptomatic course of the disease, ascending infection of the uterus and appendages is not excluded. nine0005

- Salpingitis and salpingoophoritis (usually with an erased long-term course without a tendency to worsen): severe pain in the lower abdomen, fever sometimes up to 38 degrees, sometimes urination disorders, bloating, dyspepsia.

- Endometritis: fever, lower abdominal pain, serous-purulent discharge.

- Infertility (sometimes this is the only complaint of the patient)

Diagnosis

A set of diagnostic measures is required to identify the infection. nine0005

- Bacteriological examination

- PCR

- Blood serology

Modern diagnostic methods:

- Chlamydia test using PCR (polymerase chain reaction).

Accuracy - 100%.

Accuracy - 100%. - Culture for bacteria. Accuracy - 70%.

- Enzyme immunoassay. Accuracy - 50%.

- Vaginal swab. Accuracy - 15%. nine0014

Finally, modern diagnostics actively uses ultrasound. The procedure most accurately detects the pathology of the tissues of the genital organs, typical for chlamydia.

In any case, the more accurate the diagnosis, the earlier it is started.

Treatment

Treatment of urogenital chlamydia is carried out with antibacterial drugs, treatment is mandatory for both the woman and her partner. In order to prevent candidiasis against the background of antibacterial treatment, antimycotic drugs are prescribed. In chronic recurrent chlamydia, immunomodulators must be selected. Control studies are carried out 3-4 weeks after treatment and then for three menstrual cycles. nine0005

Please note! Self-medication is unacceptable! Incorrect selection of the drug can turn the disease into a chronic stage.

Learn more