Can 2 year olds walk

Walking (Gait) Abnormalities | Boston Children's Hospital

A gait abnormality is an unusual walking pattern. Many young children may have an abnormal gait for a period of time as they grow and learn to walk.

Many parents worry about their children’s unusual walking patterns, however, gait abnormalities are a regular part of physical development. The vast majority of kids grow out of gait abnormalities without medical treatment.

When do babies start walking?

Babies typically start walking when they are around 1 year old. From there, they spend the next several years developing balance and leg strength.

The following age ranges are considered average for developmental milestones. Some children reach these milestones earlier and some reach them later. If you are concerned about your baby’s physical development, talk with your pediatrician.

Developmental milestones

- Around 6 months, most babies can sit with support and roll over

- Around 9 months, most babies learn to crawl.

- Around 9-12 months, most babies will pull themselves up to standing by holding onto furniture. Babies at this stage can walk with support but can't yet walk on their own.

- By 11-16 months, most babies will start to walk without support.

- By 2 years, most toddlers can go up stairs one at a time and jump in place.

- By 3 years, most children can go up stairs reciprocally and stand on one foot.

- By 4 years, most children can go down stairs reciprocally and hop on one foot.

What are the most common types of pediatric gait abnormalities?

The most common types of gait abnormalities in children are intoeing and outtoeing.

- Intoeing is walking with the feet turned inward.

- Outtoeing is walking with the feet turned outward.

Intoeing and outtoeing are usually not painful.

Several common conditions can cause your child’s feet to turn inward or outward in their early years, including tibial torsion and femoral rotation (described below). Each of these conditions typically improve on their own during childhood.

Each of these conditions typically improve on their own during childhood.

What causes pediatric gait abnormalities?

Tibial torsion

Tibial torsion is the turning of a child’s lower leg (tibia) either inward (internal tibial torsion) or outward (external tibial torsion). The condition often improves without treatment, usually before a child turns 4.

Some children with tibial torsion wear a night brace between 18 to 30 months old, but this is not common. Doctors only consider surgery for tibial torsion if a child still has the condition when they are 8 to 10 years old and having significant walking problems.

Femoral version

Femoral version describes a child’s upper leg bone (femur) that twists inward or outward. Inward twisting of the femur (femoral anteversion) causes the feet to point inward. Signs of femoral anteversion usually first become noticeable when a child is between 2 to 4 years old, a time when inward rotation from the hip tends to increase. The condition usually gets better without treatment.

The condition usually gets better without treatment.

Outward twisting of the femur is called femoral retroversion and causes the feet to point outward. It is less common than femoral anteversion. In some cases, femoral retroversion may delay a child’s walking, however, the condition often gets better without medical intervention.

Doctors consider surgery for femoral anteversion or femoral retroversion only if a child is older than 9 and has a very severe condition that causes a lot of tripping and an unsightly gait.

Bowlegs and knock knees

Bowlegs is an outward curve of the legs at the knees. Knock knees is an inward curve of the legs at the knees. Both bowlegs and knock knees are common stages of development and usually self-correct as a child grows.

Flatfeet

Flatfeet are normal in infants and young children. Children have flat feet when the arches in their feet have not yet developed and their entire feet press against the floor. The arches develop throughout childhood until about age 10.

The arches develop throughout childhood until about age 10.

Metatarsus adductus

Metatarsus adductus is a common positional deformity that causes a child's feet to bend inward from the middle of the foot to the toes. In severe cases, it may resemble clubfoot. The condition improves on its own most of the time.

Babies with severe metatarsus adductus may need treatment, which usually involves special exercises, casts, or special corrective shoes. These treatments have a high rate of success in babies from 6 to 9 months old.

Limping

Sudden limping is most likely due to pain caused by a minor, easily treated injury. Splinters, blisters, or tired muscles are common culprits. Less often, limping can involve a more serious problem such as a sprain, fracture, dislocation, joint infection, or autoimmune arthritis. In rare cases, a limp may be the first sign of a tumor.

Non-painful chronic limping may be sign of developmental problem, such as a leg length discrepancy or hip dysplasia or a neuromuscular problem, such as cerebral palsy.

Toe walking

Toe walking is a common gait abnormality, particularly in young children who are just starting to walk. In most cases, this will resolve on its own over time without intervention. However, children who walk normally for a period and then later begin to walk on their toes, or children with tightness of their Achilles tendons, should be evaluated by a physician.

Many cases of persistent toe-walking run in families or are caused by tight muscles. Treatment may involve observation, physical therapy, bracing, casting, or surgery. In some cases, toe-walking may indicate a neuromuscular disorder such as cerebral palsy or it could be a sign of developmental dysplasia of the hip or leg length discrepancy.

How are gait abnormalities diagnosed?

Your child’s doctor will perform a physical exam and watch your child as they walk or run. They may look to see whether your child’s legs are shaped the same or differently. They may also ask if your child shows any signs of being in pain when they walk and whether any members of your close family have had long-term walking problems.

Other diagnostic procedures may include:

- X-ray: A diagnostic test that produces images of internal tissues, bones, and organs that can be used to look at bone structure and alignment.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): A diagnostic procedure that produces detailed images of soft tissues and structures within the body. This test is sometimes used to rule out any associated abnormalities of the spinal cord and nerves.

- Computerized Tomography scan (also called a CT or CAT scan): A diagnostic imaging procedure that shows detailed images of the bones and joints.

How are pediatric gait abnormalities treated?

In most cases, a child with an abnormal gait is observed over the course of several years. The doctor will monitor your child’s walking patterns to ensure their legs continue to develop and their walking patterns become more typical over time. Fortunately, most causes of gait abnormalities will resolve without any intervention as a child grows.

If a gait abnormality is caused by an injury or developmental condition, your child’s doctor will treat that condition. Treatment for gait abnormalities that do not resolve may include surgery and is something to discuss with your doctor.

How we care for gait abnormalities at Boston Children’s Hospital

The Lower Extremity Program at Boston Children's Hospital offers comprehensive assessment, diagnosis, and treatment for children of all ages with conditions affecting their lower limbs. We have extensive experience treating disorders of the feet, ankles, knees, legs, and hips. Whether the patient is an infant, child, or adolescent, our goal is to help children live full, independent lives.

When do babies start walking, and how does it develop? (illustrated)

© 2020-2022 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

Most babies start walking independently within 2-3 months of learning to stand up by themselves. But there are other signs, and there is no single developmental timeline that all babies follow. In fact, the onset of walking is extremely variable, with some babies walking before 9 months, and others waiting until they are 18 months or older.

In fact, the onset of walking is extremely variable, with some babies walking before 9 months, and others waiting until they are 18 months or older.

When do babies start walking? In the United States today, the average age of independent walking is approximately 12 months. Researchers report similar timing for babies in a number of other countries, including Argentina, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, South Africa, and Turkey. On average, babies in these countries take their first, unassisted steps at around 12-13 months (WHO 2006a; Ertem et al 2018).

But there are cultures where most babies begin walking months earlier – or many months later. And even within a single society, the range of individual variation can be huge. For example, in a study tracking the development of 220 children in Switzerland, a few babies began walking independently at 8.5 months. And some babies didn’t walk until they were nearly 20 months old. Yet all of those children experienced healthy, normal outcomes. The timing of independent walking was unrelated the children’s later motor development and cognitive ability (Jenni et al 2013).

The timing of independent walking was unrelated the children’s later motor development and cognitive ability (Jenni et al 2013).

Of course, that isn’t always the case. Sometimes delays in the onset of walking are caused by medical conditions or developmental disorders. But most late walkers don’t have these problems.

So what’s normal? What should we expect? How can we tell if a baby is ready to walk, and what makes some babies begin walking earlier than others? Here’s an overview, beginning with the motor skills that babies must master before they start walking on their own.

Before they can walk, babies need to develop the strength and coordination to maintain an upright posture on their own. They also need to be able to bear most of their weight – at least momentarily – on one foot. So babies are moving closer to independent walking when they achieve these motor milestones:

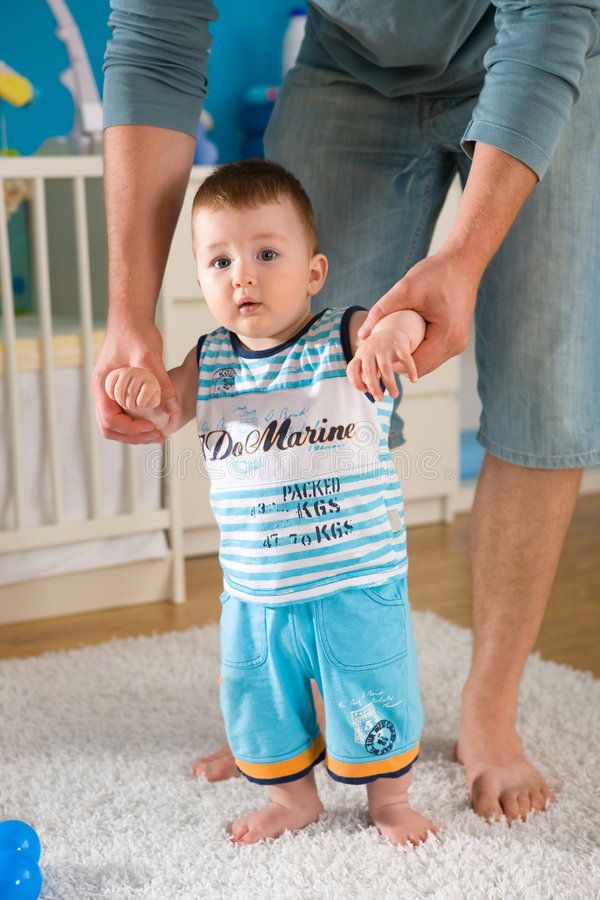

Milestone: Pulling oneself up into a standing position (by gripping furniture, or holding onto someone)Typically, babies develop this ability about 4 months before they take their first, independent steps (Ertem et al 2018). During early attempts, a baby will be able to remain standing for only a few seconds, and you will notice that the baby’s legs are stiff and straight (as they are in this photo). But as the baby gets stronger, he or she will be able to stand comfortably — with knees slightly flexed — while holding on.

During early attempts, a baby will be able to remain standing for only a few seconds, and you will notice that the baby’s legs are stiff and straight (as they are in this photo). But as the baby gets stronger, he or she will be able to stand comfortably — with knees slightly flexed — while holding on.

At this stage, babies have the strength to shift their weight from one leg to the other. If you hold a baby by the hands, he can walk forward. If a baby grabs onto a piece of furniture (like a couch or sofa), she can “cruise,” or move along sideways. When will a baby with these abilities begin walking independently?

Studies suggest that independent walking tends to emerge about 3 months later (WHO 2006a; Ertem et al 2018), but there’s no strict sequence that all babies follow. Some babies begin walking with support relatively early — even before they have learned to crawl. For these babies, the next stage might be independent walking. But babies might also shift their focus to crawling (WHO 2006b).

But babies might also shift their focus to crawling (WHO 2006b).

How long after learning to stand unassisted do babies begin to walk? International studies suggest that most babies start walking within 2-3 months of learning to stand (Ertem et al 2018). But it isn’t the absolute passage of time that matters so much. It’s the sheer amount of practice and hard work.

When babies are learning to walk independently, they fall down. A lot. Some babies don’t seem to mind much. They enthusiastically throw themselves into the project, and learn to walk rather quickly — sometimes within a few days of learning to stand.

What about crawling? Do babies have to crawl before they can walk?Absolutely not. In fact, some babies never crawl. Read more about it in my article “When do babies crawl, and how does crawling develop: An illustrated guide.”

When can babies walk with support?International research suggests that approximately 50% of all babies have begun walking with support by the age of 9. 5 months (WHO 2006a; Ertem et al 2018). But local norms differ.

5 months (WHO 2006a; Ertem et al 2018). But local norms differ.

In cultures where parents actively teach their babies to walk, infants may begin assisted walking by 7-8 months (e.g., Super 1976). By contrast, in places where parents take a more hands-off approach, the average onset of walking with support is later – closer to 10.5 months (WHO 2006a). And in societies where babies remain physically restrained throughout the day – in carriers, slings, cradles, and other devices – babies don’t begin walking until much later.

When do babies make the transition to independent walking?As noted in the introduction, there is a wide range of variation here. Some babies begin before they are 9 months old. Others take 18 months or more. Why is there so much variation, and what sort of factors predict whether a child will walk earlier or later?

Human bipedalism is a difficult trick to learn. Babies face many obstacles, including their own bodies. For instance, a baby with skinny legs – and a higher muscle-to-fat- ratio – will have an easier time fighting gravity, and may begin walking sooner than a plumper, less muscular infant (Adolf 2008). The timing of walking also depends on opportunities for movement and practice.

The timing of walking also depends on opportunities for movement and practice.

In general, babies who get more exercise – time outside a sling, crib, or cradle – tend to achieve motor milestones earlier in life. More specifically, babies learn to walk earlier if they get lots of practice with “assisted walking” — taking steps forward while someone holds their hands.

Motivation is probably important, too. For example, researchers have found that babies are more likely to start learning to walk if they show an interest in accessing distant objects, such as toys (Karasik et al 2011).

And something as mundane as clothing can make a difference. Experimental research confirms that it’s harder for babies to walk when they are wearing diapers. The bulk gets in the way – forcing them to waddle with their legs farther apart – and babies are more likely to lose their balance and fall (Cole et al 2012).

Together, these factors can help explain why babies vary as individuals. They can also shed light on some of the dramatic differences we observe between cultures.

They can also shed light on some of the dramatic differences we observe between cultures.

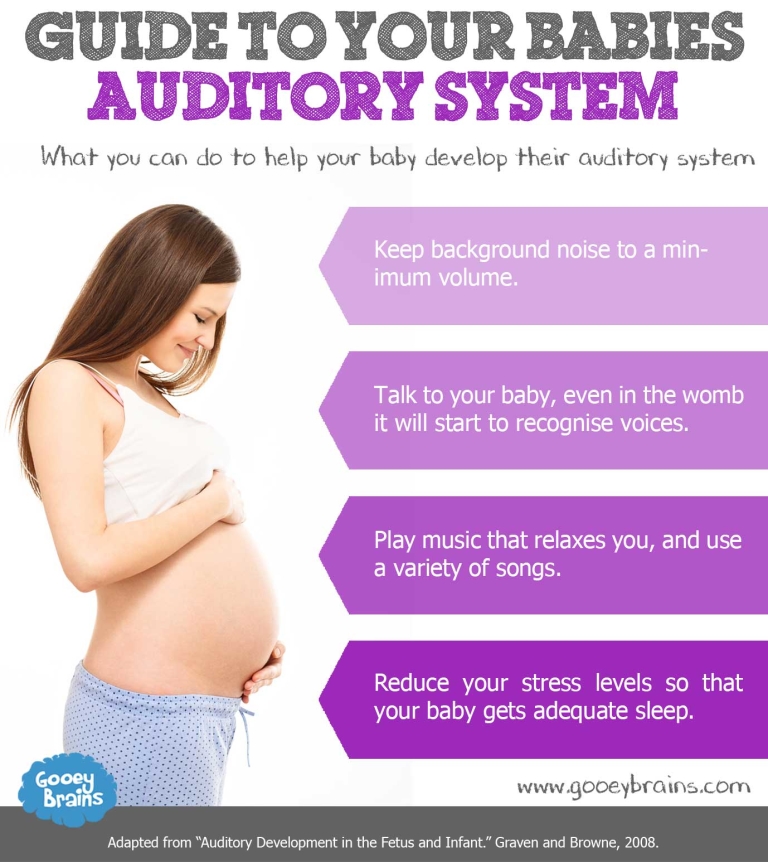

Consider the Kipsigis of Kenya, people who raise crops and herd cattle. In this culture, parents actively encourage infants to develop motor skills essential for walking. It begins with something called the stepping reflex: Hold a newborn baby upright – allowing his or her feet to touch the ground – and the baby will appear to take alternating steps. As if the baby is ready to walk!

Of course, the baby isn’t really ready to walk, not yet. Young babies lack the muscle development, coordination, and body proportions to walk successfully when they are very young. And if we simply ignore this stepping response, the behavior will eventually fade. In Western countries, for example, the stepping response usually disappears by the time babies are 8 weeks old.

But the Kipsigis don’t ignore the stepping reflex. Instead, they turn it into a game. Supporting babies by the armpits, mothers bounce their babies on their laps, stimulating the stepping reflex.

Instead, they turn it into a game. Supporting babies by the armpits, mothers bounce their babies on their laps, stimulating the stepping reflex.

The games start when babies are about one month old, and babies experience daily practice. By the time they are 7-8 months old, infants are strong enough to begin walking (with support) on the ground. There is never a point when babies lose the stepping response. Instead, there is a continuous, gradual development of ever-stronger stepping (Super 1976).

When researchers tested a similar approach on babies living in the United States, they noticed the same thing: Babies didn’t lose the stepping response over time, not when they were encouraged to practice it (Zelazo 1983). And in both groups — Kipsigis and Americans — researchers observed a relationship between practice and the timing of walking. Babies who practiced step-walking tend to walk independently at an earlier age (Super 1976; Zelazo 1983).

So parents can stimulate the development of walking through exercise and play. In fact, even “tummy time” has been linked with the development of walking. The more time young babies spend on their tummies, the earlier they tend to reach the motor milestones of assisted walking and independent walking (Carson et al 2022).

In fact, even “tummy time” has been linked with the development of walking. The more time young babies spend on their tummies, the earlier they tend to reach the motor milestones of assisted walking and independent walking (Carson et al 2022).

Moreover, the reverse is true as well: When babies experience higher levels of movement restriction – by being held, swaddled, strapped into a chair, or otherwise immobilized during the day – they begin walking later (Adolph and Robinson 2013; Carson et al 2022).

For an extreme case, consider the Ache of Paraguay, people who practiced hunting and gathering until the late 20th century. When they were living in the old, traditional way, the Ache carried their babies almost constantly. They regarded their environment – the Amazonian rain forest – to be too dangerous to set infants down. So Ache babies didn’t get opportunities to practice walking, and, as a result, children didn’t learn to walk until they were approximately 24 months old (Kaplan and Dove 1987).

I call this an extreme case, but “extreme” is a relative term: It depends on what populations you use for comparison. The Ache aren’t the only hunter-gatherers who avoided setting their babies on the ground. And people in other societies follow customs that restrict infant movement. For instance, throughout Central Asia, babies spend long hours each day restrained in a traditional cradle called a “gahvora” (Karasik et al 2018). In different times and places, it might have been pretty common for babies to miss out on the sort of experiences that lead to early walking. And that should make us re-evaluate our ideas about what constitutes “normal” development.

It doesn’t make sense to talk about “normal” timing in a vacuum, as if local differences in the environment don’t matter.

Can “walking toys” help babies learn to walk?Another name for “walking toys” is “locomotor toys” — toys that are designed to be pushed, pulled, or rolled. What happens if you provide a baby with such toys — like a “popper” push toy, which pops plastic balls when you roll it along the ground? It isn’t clear that this will motivate a baby who isn’t yet walking to take his or her first steps. But push toys and pull toys might encourage early walkers to keep at it longer.

But push toys and pull toys might encourage early walkers to keep at it longer.

In a study of 40 walking babies (average age: 15 months), Justine Hoch and her colleagues assigned half of them to spend time in a room with a caregiver and several locomotor toys. The other half spent time with a caregiver in the same room, but without toys. The researchers recorded the infants’ movements, and found that babies in both groups walked around in equal amounts. But the babies provided with locomotory toys walked in longer bouts — taking more steps before coming to a halt. They were also more likely to explore every part of the playroom, and to stray farther from their caregivers (Hoch et al 2019).

What about baby walkers? Why do experts warn parents against using them?A baby walker is a rigid frame, on wheels, with a seat suspended in the middle. When an infant is placed in the seat, his or her toes reach the ground, and the baby is able to move independently by pushing off in various directions.

It might sound like a shortcut for learning to walk, but it isn’t. On the contrary, when infants use baby walkers, they frequently adopt abnormal postures and gait patterns. For instance, they may lean backwards, walk on tiptoes, or fail to control the movement of their heads (Schecter et al 2019). They aren’t actually practicing the movements they need to master to learn to walk.

Moreover, the trend across studies is either neutral or negative. Some studies have found that baby walkers confer no motor skill advantages. Others have reported distinct disadvantages — that infants who use walkers tend to be slower to reach motor milestones, including crawling, standing alone, and walking independently (Badihian et al 2017; Schecter et al 2019; Bezgin et al 2021).

But the most important problem concerns safety. Baby walkers are linked with high rates of injury. Accidents are often caused by babies falling down the stairs while in a walker, and there are other hazards too. Infants have fallen out of their walkers. They’ve injured themselves by reaching for objects that are heavy, sharp, or burning-hot. And the injuries can be serious – concussions, lacerations, bone fractures. Some infants have died (Sims et al 2018).

Infants have fallen out of their walkers. They’ve injured themselves by reaching for objects that are heavy, sharp, or burning-hot. And the injuries can be serious – concussions, lacerations, bone fractures. Some infants have died (Sims et al 2018).

Given these dangers – and the lack of developmental benefits – the American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended a ban on the manufacture and sale of baby walkers (American Academy of Pediatrics 2001), and baby walkers have been banned in Canada since 2004 (Skinner et al 2010).

When should a parent be concerned that a baby isn’t walking? At what point is a child considered to have developmental delay?Organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics (APP) recommend that you talk with your doctor if your baby can’t walk by the age of 18 months. And that’s good advice. Sometimes, delayed walking is a sign of a physical problem, so it’s good to investigate early, and take action. In a review of more than 400 “late walkers”, nearly one-third of the cases were attributable to some kind of underlying clinical or neurological condition (Chaplais and McFarlane 1984).

But keep in mind: Most babies who haven’t yet begun walking at 18 months do not suffer from developmental problems. Not if they are otherwise healthy.

More reading about baby developmental milestonesAs we’ve seen, babies don’t learn to walk on a fixed time schedule. The timing can vary dramatically from one individual to the next. The same is true for many other motor skills. To learn more about it, see my article on baby motor milestones.

In addition, check out my guide to the development of crawling, as well as these articles about baby development:

- When do babies say their first words?

- Can babies sign before they speak?

- Do babies feel empathy?

- Can babies sense stress in others?

- Can babies tell when their parents are fighting?

- Moral sense: Babies prefer underdogs and do-gooders

- Stress in babies: How to keep babies calm, happy, and emotionally healthy

- How friendly eye contact can make infants tune in — and mirror your brain waves.

References: When do babies start walking?

Note to the scholarly: If you want to dive into the scientific literature about walking, be sure to check out the work of Karen Adolph and Lana Karasik.

Adolph heads a research team at New York University. Many of her lab’s publications can be downloaded for free from the NYU infant action lab. Karasik is currently at the City University, CUNY. You can find her publications is at the Karasik Lab of Culture & Development.

Adolph KE. 2008. Motor and physical development: Locomotion. In M. M. Haith & J. B. Benson, (Eds.), Encyclopedia of infant and early childhood development (pp. 359-373). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Adolph KE and Robinson SR. 2013. The road to walking: What learning to walk tells us about development. In P. Zelazo (Ed), Oxford handbook of developmental psychology (pp. 403-443). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. 2001. Injuries associated with infant walkers. Pediatrics. 108(3):790-2.

2001. Injuries associated with infant walkers. Pediatrics. 108(3):790-2.

Badihian S, Adihian N, Yaghini O. 2017. The Effect of Baby Walker on Child Development: A Systematic Review. Iran J Child Neurol. 11(4):1-6.

Bezgin S, Uzun Akkaya K, Çelik Hİ, Duyan Çamurdan A, Elbasan B. 2021. Evaluation of the effects of using a baby walker on trunk control and motor development. Turk Arch Pediatr. 56(2):159-163.

Carson V, Zhang Z, Predy M, Pritchard L, and Hesketh KD. 2022. Longitudinal associations between infant movement behaviours and development. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 19(1):10.

Chaplais JD and Macfarlane JA. 1984. A review of 404 ‘late walkers’. Arch

Dis Child. 59(6): 512–516.

Cole WG, Lingeman JM, Adolph KE. 2012. Go naked: diapers affect infant walking. Dev Sci. 15(6):783-90.

Hoch JE, O’Grady SM, Adolph KE. 2019. It’s the journey, not the destination: Locomotor exploration in infants. Dev Sci. 22(2):e12740.

Kaplan H and Dove H. 1987. Infant development among the Ache of eastern Paraguay. Developmental Psychology, 23(2): 190–198.

Developmental Psychology, 23(2): 190–198.

Karasik LB, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Ossmy O, and Adolph KE. 2018. The ties that bind: Cradling in Tajikistan. PLoS ONE, 13(10): e0204428–18.

Karasik LB, Tamis-LeMonda CS, and Adolph KE 2011. Transition from crawling to walking and infants’ actions with objects and people. Child Development, 82, 1199-1209.

Jenni OG, Chaouch A, Caflisch J, and Rousson V. 2013. Infant motor milestones: poor predictive value for outcome of healthy children. Acta Paediatrica 102 (4): e181

Schecter R, Das P, Milanaik R. 2019. Are Baby Walker Warnings Coming Too Late?: Recommendations and Rationale for Anticipatory Guidance at Earlier Well-Child Visits. Glob Pediatr Health. 6:2333794X19876849.

Sims A, Chounthirath T, Yang J, Hodges NL, Smith GA. 2018. Infant Walker-Related Injuries in the United States. Pediatrics. 142(4):e20174332

Skinner R, Ugnat AM, Grenier D. 2010. Baby products and injuries in Canada: Is it still an issue? Paediatr Child Health. 15(8):490.

15(8):490.

Super CM. 1976. Environmental effects on motor development: the case of “African infant precocity”. Dev Med Child Neurol. 18(5):561-7.

WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. 2006a. Assessment of sex differences and heterogeneity in motor milestone attainment among populations in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 450:66-75.

Zelazo PR 1983. The development of walking: New findings and old solutions. Journal of Motor Behavior 15: 99-137.

Content of “When do babies start walking” last modified 8/2/2022. Portions of the text derive from an earlier version of this article, written by the same author.

Image credits for “When do babies start walking”:

image of toddler’s and parent’s legs by Halfpoint/ istock

image of baby standing independently with arms in the air by Prostock-studio / shutterstock

image of baby girl pulling herself up into a standing position by grasping a kitchen chair by Ekaterina Pokrovsky/shutterstock

image of infant seated in a green baby walker by Drovnin / shutterstock

image of mother helping baby walk by eggeeggjiew / istock

Development of a child from 2 years to 2.

5 years of life: what a child should be able to do

5 years of life: what a child should be able to do For a child from 2 years to 2 years and 6 months: what he should be able to do

- After the child is 2 years old, his vocabulary will quickly begin to increase, and by the age of 3 it will reach 800 words. If there is no progress in increasing the vocabulary, then this is the period when it is worth contacting a speech therapist and a neurologist.

- Speech at this age is predominantly situational. The child gradually adopts the norms and rules of behavior, learns to follow them, but does not always do it with pleasure. However, there are rules in every family (brush your teeth, take off your street shoes, wash your face, etc.) and it is important that parents insist on following them. Therefore, parents need to decide on the rules of the family and follow them themselves.

What a child can do from 2 years to 2 years and 6 months:

- Signals physiological needs, attempts to use the potty independently.

If the diaper has not been removed yet, then this is a great age to remove it.

If the diaper has not been removed yet, then this is a great age to remove it. - Knows how to wash hands, dry them with a towel, but does it formally.

- Knows how to eat on his own, but at the same time he can ask for “finishing”, since the child, having received a small amount of food, may lose interest in it; uses a spoon, improves this skill in the game and while eating.

- Wants to do adult things with adults: cook dinner, wash the floor, but this does not mean that the child will do this all the time; It is important for parents not to refuse the help of the child.

- With a little help from adults, be able to dress and undress, but the period of unwillingness to dress and undress on their own (especially in the autumn-winter period) remains quite stable.

- Knows how to play alongside peers (the child can take the initiative, play with other children, but does not yet like to share toys).

- Moves from whispering to speaking loudly.

In the field of physical development and motor skills:

- Runs, performs rhythmic jumps.

- Climbing stairs with support.

- Throws and catches the ball from a short distance, rolls and kicks the ball.

- Draws straight lines, circles, squiggles.

- Builds a tower with 5-6 cubes.

- Recognizes and names primary colors.

Physiological curves of the spine are determined during this period. The remaining milk teeth appear, which allows you to chew properly. The achieved physical fitness is already so great that walking, overcoming obstacles, climbing and descending stairs, walking backwards and jumping is not a problem for the baby.

At about 2.5 years old, the child notices anatomical differences between the sexes.

Child skills at 2 years old:

- Walks and runs, walks down stairs, step by step, holding onto handrails.

- Knows how to kick, roll, throw the ball.

- Knows about 200 words, including the names of basic colors.

- Names the objects shown in the pictures.

- Helps adults, participates in household chores; draws lines, circles, zigzags.

Child skills at 2 years and 6 months:

- Walks up and down stairs without help from adults.

- Speaks in simple sentences.

- The leading activity is play, the child explores the world through the game.

- Recognizes the path to places where he often goes, such as his grandmother or the children's clinic.

- Begins to distinguish male and female, but focuses on external signs: clothes, voice. Gender-role identification is not yet constant, the child rather repeats after the adult who he is: a boy, a girl.

- Has a growing need for independence (he wants to do many things alone).

Your child is beginning to understand concepts such as time and opposites, such as big/small and day/night. Begins to point to body parts based on what they do, learns to sort objects and match shapes, colors. Begins to remember what things look like, for example: apples are round, cucumbers are green.

Begins to point to body parts based on what they do, learns to sort objects and match shapes, colors. Begins to remember what things look like, for example: apples are round, cucumbers are green.

Child memory:

- The objects themselves are remembered better than their names.

- The ability to think about the missing object appears.

- Mostly motor and emotional memory present.

- Arbitrary memory appears, which is the start to the development of imagination.

Child height from 2 years to 2 years and 6 months - norms for boys and girls

- Girls: 86 to 92 cm.

- Boys: 86 to 93 cm.

Child weight 2 years to 2 years and 6 months - Boys and girls norms

- Girls: 12.1 to 13.2 kg.

- Boys: 12.6 to 13.6 kg.

The average weight of a two-year-old child is 12 kg for girls and 13 kg for boys. However, many children at this age weigh +/-3 kg above average, and this is completely normal. Be prepared that at the age of 2 to 3 years, the baby will add about 200 g per month.

However, many children at this age weigh +/-3 kg above average, and this is completely normal. Be prepared that at the age of 2 to 3 years, the baby will add about 200 g per month.

Mental development of a child from 2 years to 2 years and 6 months

The mental development of a child from 2 years old makes it possible for parents to more clearly observe the developing character traits of the baby. The reactions of the child become more diverse, which indicates that he develops and learns different forms of response to certain situations. The child takes a role model from his parents and relatives and acquaintances whom he often sees.

The character of the child will be formed for many years, but now parents can support the development of some qualities and even correct them to make life easier for the child in society. Remember that character is formed in the first 3-5 years.

In the emotional sphere, the life of a two-year-old child becomes a little easier, on the one hand, as the baby begins to be more independent, but on the other hand, he still cannot do a lot of things himself, which causes a new storm of emotions.

The ability to wait a while or endure a little discomfort is greatly increased. The child is approaching the "crisis of three years", and the reaction to the parent's "no" or "no" can be very strong, but this does not mean that parents should not say these words. The main thing is that the bans should be consistent and predictable for the child: if you can’t take the phone today, then you can’t take it tomorrow either.

In this age period, after 2 years, it is important to form the boundaries of acceptable behavior:

- The child must clearly understand when “it is impossible never”, in which - “it is impossible if ...”, and in which “it is possible”.

- "It is possible" should sound more often from the lips of parents than "it is impossible".

- These boundaries should be communicated by all adults with whom the child lives.

At this stage of development, the baby is still very strongly attached to his parents, especially to his mother, with whom he is in the same emotional field, and is very dependent on his mother's emotional state. It is important for a child to be accepted by parents, especially a mother, rejection is perceived as a "collapse of the world."

It is important for a child to be accepted by parents, especially a mother, rejection is perceived as a "collapse of the world."

The kid begins to establish a qualitatively different contact with peers, with the participation of an adult, he can already begin to play with them.

The child is learning self-control, although there are still emotional outbursts during which he may hit, bite or throw a toy at someone. The kid loves to be in the center of attention, to fool around and imitate, to arouse interest. One of the periods in which the child goes through the understanding of what "boundaries" are. The process of assimilation of "mine" - "someone else's" begins. So, he can lend another baby a toy and immediately start demanding it back. Claiming another child's toy because they liked it.

Child care from 2 years to 2 years 6 months

Here I would like to emphasize the special importance of proper nutrition, because the diet of a two-year-old child is becoming more and more similar to the diet of older children.

For proper development, the baby should eat 5 times a day, preferably at intervals of 3-4 hours. Well, if children have a fixed meal time, then it is easier for the body to control the feeling of hunger and satiety.

Young children have a high energy requirement as a result of increased physical activity and body growth. Therefore, properly selected grain products should be the main source of energy.

A two-year-old can and should eat all types of grains (except children with celiac disease), his digestive system is old enough to cope with the digestion of such products. Therefore, instant baby cereals at this age are not the best solution, but only a habit that should be changed.

Another food group that forms the basis of nutrition for young children is milk and dairy products. Two-year-olds should consume 2-3 servings of milk and dairy products. After all, they are the main source of healthy protein, as well as calcium.

Some experts believe that children 2 years of age and older should limit their intake of high-fat foods to protect them from future cardiovascular disease.

Vegetables and fruits are another important group. Small children are recommended to eat 150-200 g of fruit per day. It can be bananas, apples, persimmons, peaches, apricots (everything that contains a minimum amount of acid). Vegetables should be consumed with every meal - it can be boiled beets, carrots, potatoes, cabbage.

It is also worth paying attention to eating eggs, which are a source of iron, complete protein and nutrients such as choline, vitamin B, which are responsible for the proper functioning of the brain, affecting concentration, memory and learning.

A two-year-old child should eat fish and seafood 1-2 times a week, especially of marine origin, in addition to essential fatty acids, they contain iodine, which stimulates the cells of the immune system.

Another important point is that children in the second year of life may refuse to eat the offered food to the end. Do not force the child to eat, as this forms the wrong eating habits. Feeding a child should be based on a principle that must always be remembered: parents decide what their child will eat, and the child decides how much he will eat.

Feeding a child should be based on a principle that must always be remembered: parents decide what their child will eat, and the child decides how much he will eat.

When a child starts walking and how to help him

October 12, 2019LikbezAdvice

At one and a half, it's still not too late. Have patience.

Share

0When the child should go

Pediatricians agree on some things. The average child takes Your Baby's First Steps with their first step at 12 months. The key word here is average. And your unique one has every right (approved by pediatricians and physiologists) to go to a different age.

The limits of the norm in this case vary quite widely - from 8 months to one and a half years.

Many parents are proud that their children start walking earlier than most. It seems to them that this speaks of the development of the child. But this is just a far-fetched excuse to amuse their parental vanity.

The age at which the child will go is related to his development, physical or intellectual abilities in exactly the same way as the shape of the nose or the color of the hair. In plain text, no way. Someone is red, someone has gray eyes, and someone went on their own at 8 months.

However, there are still certain situations when a delay in starting to walk should alert.

When to start worrying

First, a healthy child must somehow take the first independent step before 20 months Child development: Early walker or late walker of little consequence. By this age, the children have grown strong enough that it was given to them without much effort. If the child refuses to walk or does it only with support, it is necessary to contact the pediatrician. You may need additional examinations from other specialized specialists - an orthopedist or a neuropathologist.

Secondly, the big picture is important 14 Month Old Not Walking: Should I Worry. It's one thing if the child does not walk, but his motor functions are obviously developing: he confidently rolls over, sits down, reaches for toys, crawls, tries to rise against the wall of the crib or climb onto the sofa, jumps enthusiastically when you hold him by the hands. And it’s quite another if his physical activity seems insufficient to you. This is also a serious reason to additionally consult a doctor.

It's one thing if the child does not walk, but his motor functions are obviously developing: he confidently rolls over, sits down, reaches for toys, crawls, tries to rise against the wall of the crib or climb onto the sofa, jumps enthusiastically when you hold him by the hands. And it’s quite another if his physical activity seems insufficient to you. This is also a serious reason to additionally consult a doctor.

If none of these situations apply to you and your children, relax. The child will definitely start walking as soon as he is ready for it.

What determines when a child goes

By and large, this is a lottery. No pediatrician will undertake to predict the exact dates, even observing a specific baby from birth and knowing everything about the family history. However, there are some regularities that allow us to make assumptions.

Here are the main factors that can influence (but not necessarily) the age at which a child takes his first independent steps.

Genetics

If dad or mom started walking at an early age, it is likely that children will inherit this feature. The reverse is also true. If, for example, a father preferred to crawl for up to a year and a half, his son may choose the same tactic.

Weight and Build

Plumper and heavier children find it harder to get on their feet and balance than their leaner, more muscular pals.

Some personality traits

Getting to your feet and taking the first step without support is quite a risky undertaking. Some children act on the principle of "head into the pool": they simply remove their hands from the wall or sofa and step into the unknown. Of course, they fall, sometimes it hurts, but they try again. Perhaps this propensity for risky behavior is part of their nature 10 Things to Know About Walking, which will stay with them forever.

Other infants, on the other hand, behave in a more balanced way - they walk only when they are sure that they can cope with this task. Caution and the ability to calculate their own strengths can also be innate features of their personality.

Caution and the ability to calculate their own strengths can also be innate features of their personality.

Duration of pregnancy

Children who were born prematurely, as a rule, begin to walk a little later than their peers.

How to help your child take the first step and begin to walk confidently

It is impossible to force children to go to a certain date. Walking, for all its seeming simplicity, is a very complex and energy-intensive process: what does it take to maintain balance on one leg at the moment when the other takes a step. The body of the child must mature for this stage. But you can help Ways to Help Baby Learn to Walk. True, you will have to start long before the first step.

What to do at 2 months

Around this age, babies first try to roll over. Encourage this movement. Lay out your child more often in a soft, safe space filled with bright toys - so that you want to look at them and, possibly, get them.

Encourage children to spend more time on their stomachs. Trying to raise your head and look at the world around you strengthens the muscles of your back and neck, which play an important role in maintaining balance while walking.

Trying to raise your head and look at the world around you strengthens the muscles of your back and neck, which play an important role in maintaining balance while walking.

What to do at 4-6 months

The period when the child learns to sit up and possibly crawl. Provide a place to explore the world: let the children spend more time not in a crib or playpen, but on the floor - spread out some blankets and lay out toys. Trying to reach objects is a great workout for small muscles.

What to do at 6-8 months

The child is already sitting confidently, or even crawling. Give him tasks for dynamics: for example, roll a bright ball on the floor so that you want to catch it. Such a ball hunt trains the vestibular apparatus and coordination.

Another exercise with the same goal looks like this: put the child with his back to you and gently rock.

What to do around 8 months old

As babies become stronger and more curious, they tend to break away from their usual gender. For example, get a toy lurking on the couch. Or try to climb on mom (dad), holding on to trousers or a bathrobe with your hands.

For example, get a toy lurking on the couch. Or try to climb on mom (dad), holding on to trousers or a bathrobe with your hands.

Encourage these movements. Put your favorite bear cubs out in a conspicuous place. Or, when the child is sitting, invitingly stretch your hands towards him from the height of your own height, without bending down, to encourage him to reach out to you.

If you see that the child is ready to get up, help him to do it. And then show how to bend your knees to get back on the safe floor.

During this period, it would be good to buy a stationary game center, which you can play with just getting up. This encourages children to spend more time standing up.

What to do at 9-10 months

Teach your child to stand without support. At least a couple of seconds. To do this, at a time when he is holding on to something, offer to take his favorite or new toy. This will force him to take his hands off the support.

A slightly more advanced exercise: help the child to his feet, and then give a plastic stick as a support. Carefully move the object - the baby will start to follow him. A stroller can also play the role of a wand: put it next to it during a walk, let it grab the frame and slowly move forward.

Heavy stable toys on wheels (toy lawn mowers, carts) will also be a good simulator: by pushing them in front of them, children learn to do step by step.

What to do at 10 months and older

At this age, many children can already walk. But often they are afraid of a large open space around. Make sure that the child has the opportunity to move “along the wall” - that is, in a maximum of a step or two, move from one support to another. This will create a sense of security.

To get children to go out into the open, you can use a regular gymnastics hoop. Throw it on the child, giving him the opportunity to lean on his hands, and lead the hoop to the center of the room.