How trauma affects child development

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

Children whose families and homes do not provide consistent safety, comfort, and protection may develop ways of coping that allow them to survive and function day to day. For instance, they may be overly sensitive to the moods of others, always watching to figure out what the adults around them are feeling and how they will behave. They may withhold their own emotions from others, never letting them see when they are afraid, sad, or angry. These kinds of learned adaptations make sense when physical and/or emotional threats are ever-present. As a child grows up and encounters situations and relationships that are safe, these adaptations are no longer helpful, and may in fact be counterproductive and interfere with the capacity to live, love, and be loved.

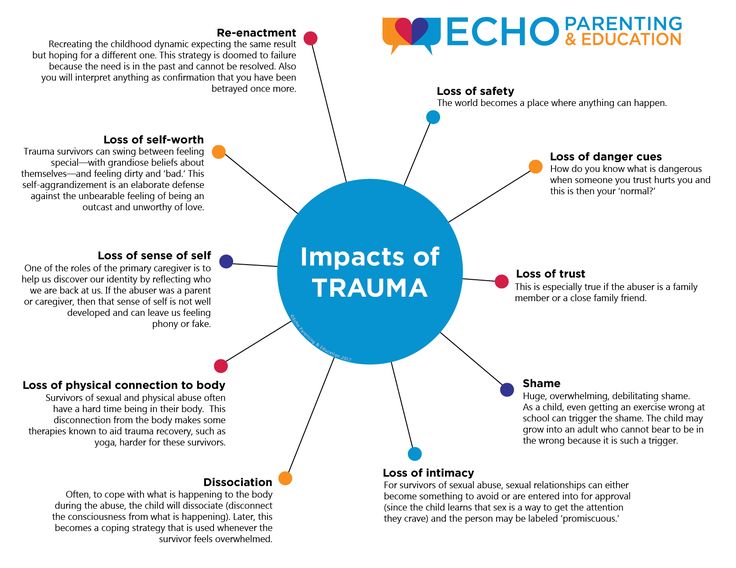

Complex trauma can affect children in a multitude of ways. Here are some common effects.

Attachment and Relationships

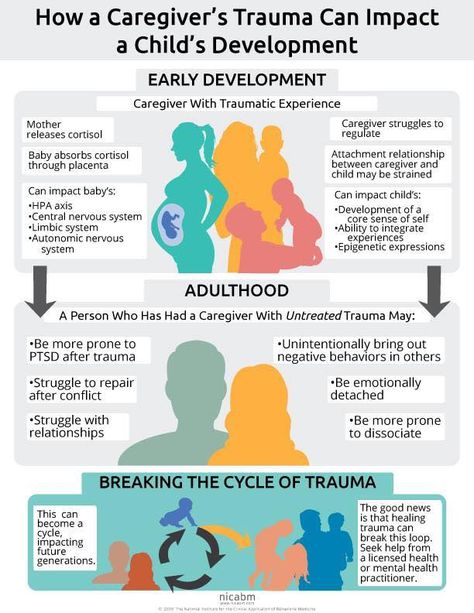

The importance of a child’s close relationship with a caregiver cannot be overestimated. Through relationships with important attachment figures, children learn to trust others, regulate their emotions, and interact with the world; they develop a sense of the world as safe or unsafe, and come to understand their own value as individuals. When those relationships are unstable or unpredictable, children learn that they cannot rely on others to help them. When primary caregivers exploit and abuse a child, the child learns that he or she is bad and the world is a terrible place.

The majority of abused or neglected children have difficulty developing a strong healthy attachment to a caregiver. Children who do not have healthy attachments have been shown to be more vulnerable to stress. They have trouble controlling and expressing emotions, and may react violently or inappropriately to situations. Our ability to develop healthy, supportive relationships with friends and significant others depends on our having first developed those kinds of relationships in our families. A child with a complex trauma history may have problems in romantic relationships, in friendships, and with authority figures, such as teachers or police officers.

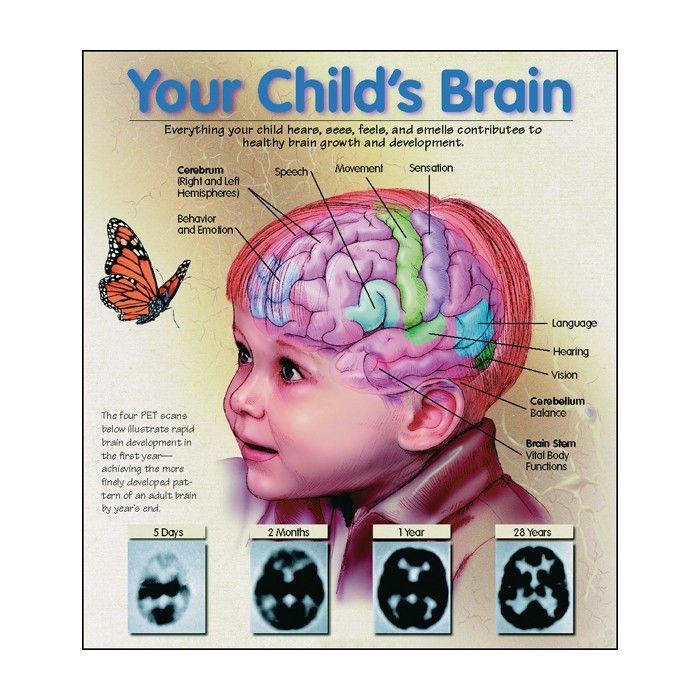

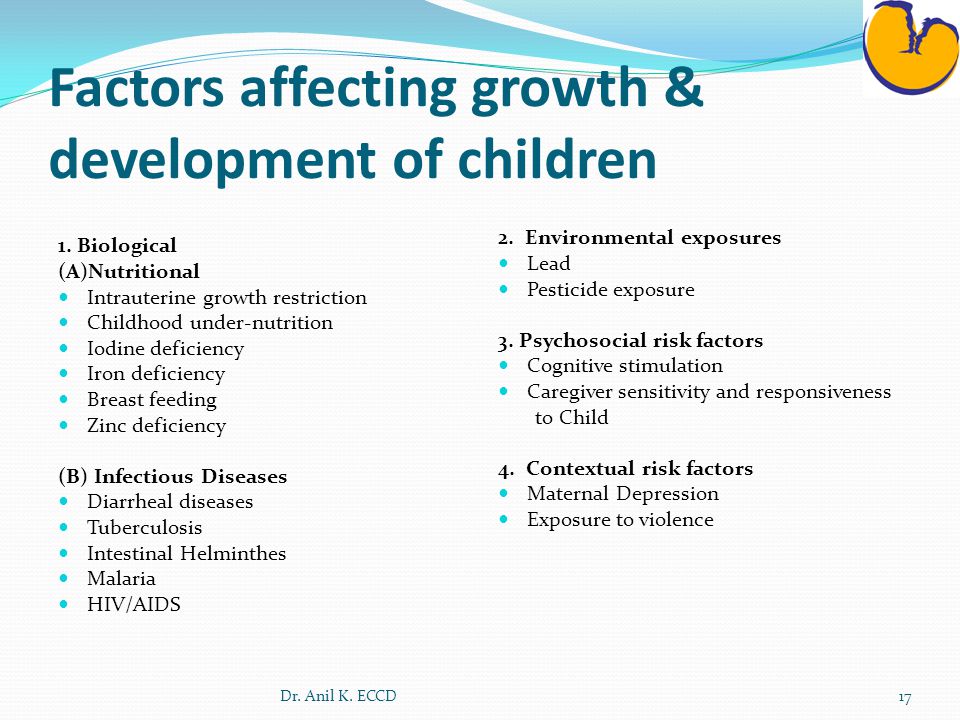

Physical Health: Body and Brain

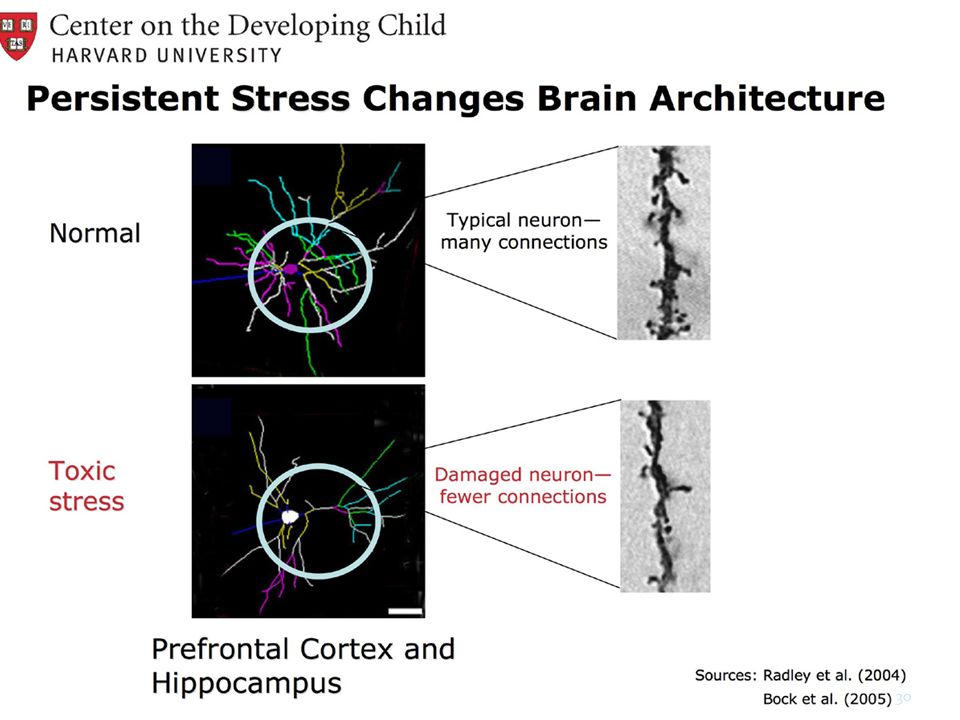

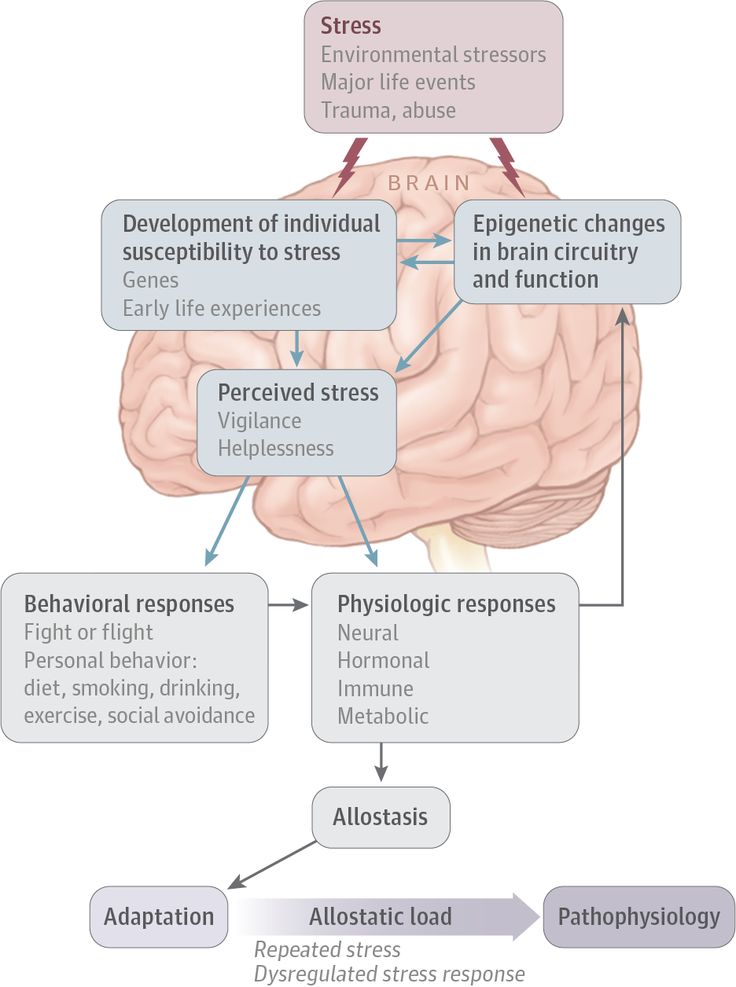

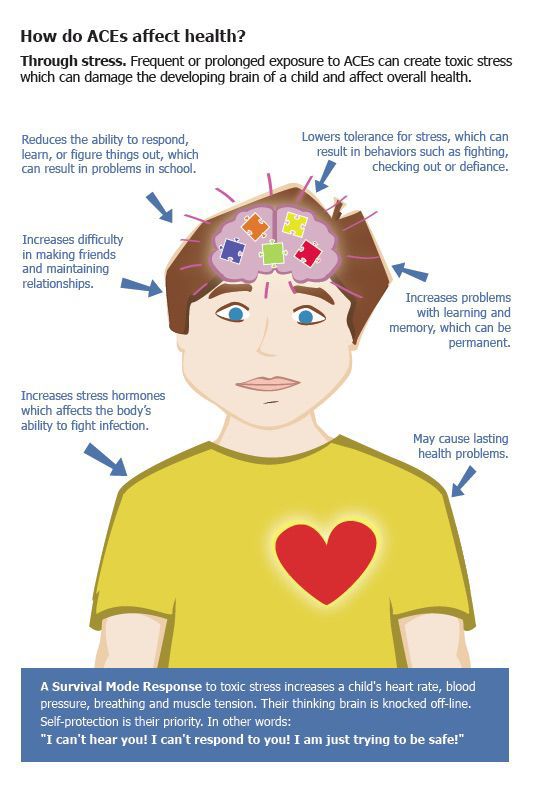

From infancy through adolescence, the body’s biology develops. Normal biological function is partly determined by environment. When a child grows up afraid or under constant or extreme stress, the immune system and body’s stress response systems may not develop normally. Later on, when the child or adult is exposed to even ordinary levels of stress, these systems may automatically respond as if the individual is under extreme stress. For example, an individual may experience significant physiological reactivity such as rapid breathing or heart pounding, or may "shut down" entirely when presented with stressful situations. These responses, while adaptive when faced with a significant threat, are out of proportion in the context of normal stress and are often perceived by others as “overreacting” or as unresponsive or detached.

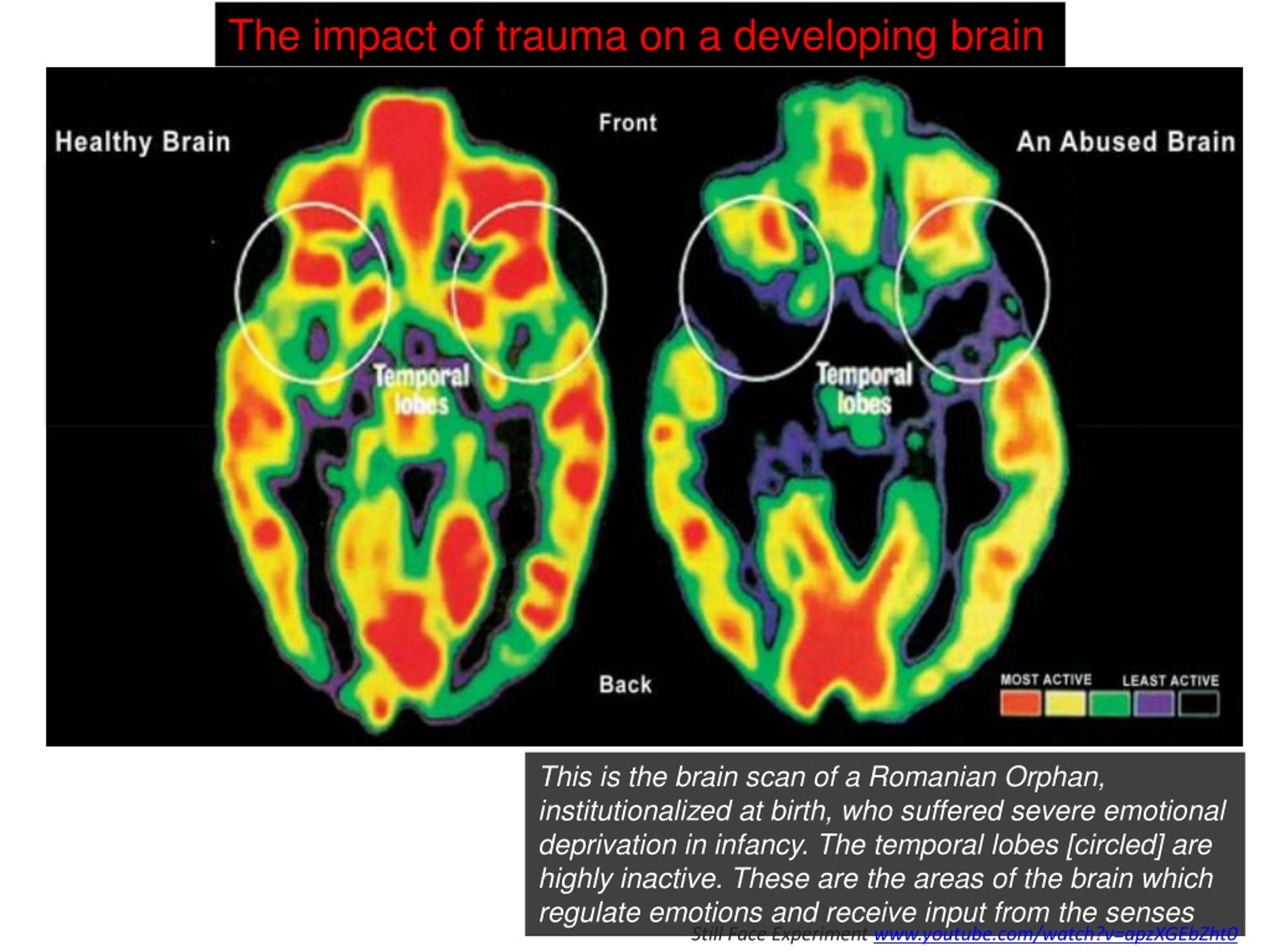

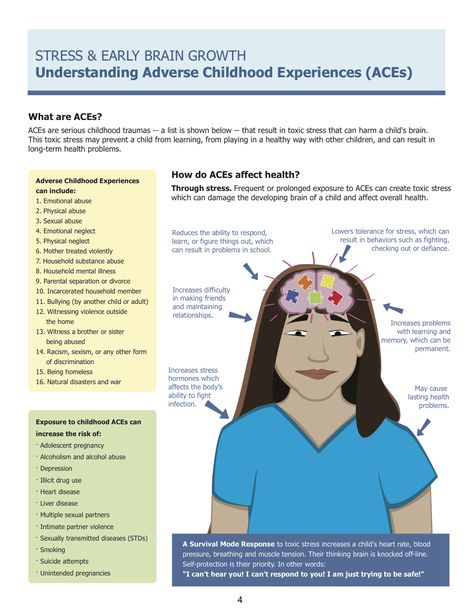

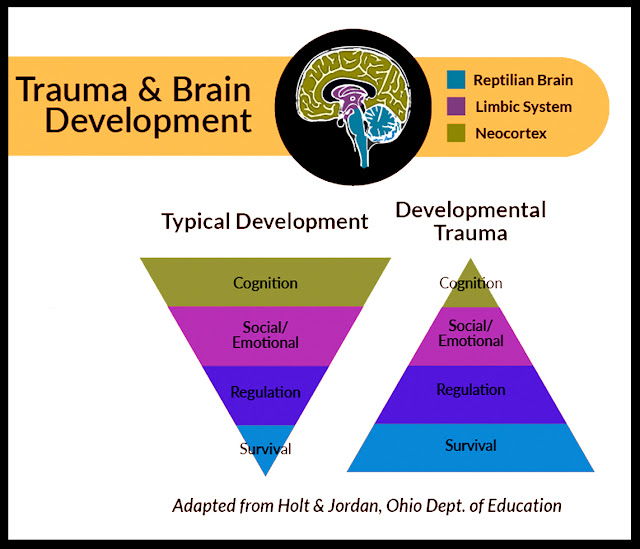

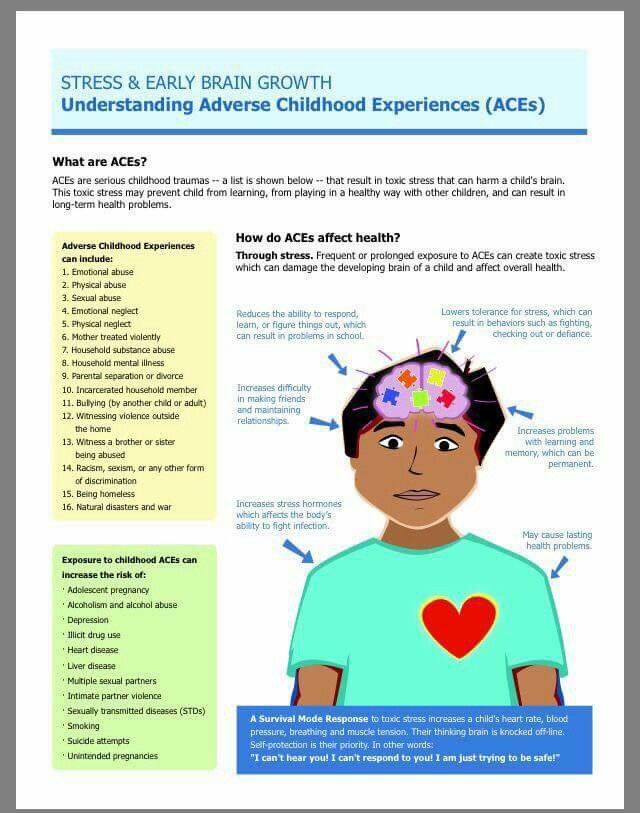

Stress in an environment can impair the development of the brain and nervous system. An absence of mental stimulation in neglectful environments may limit the brain from developing to its full potential. Children with complex trauma histories may develop chronic or recurrent physical complaints, such as headaches or stomachaches. Adults with histories of trauma in childhood have been shown to have more chronic physical conditions and problems. They may engage in risky behaviors that compound these conditions (e.g., smoking, substance use, and diet and exercise habits that lead to obesity).

Children with complex trauma histories may develop chronic or recurrent physical complaints, such as headaches or stomachaches. Adults with histories of trauma in childhood have been shown to have more chronic physical conditions and problems. They may engage in risky behaviors that compound these conditions (e.g., smoking, substance use, and diet and exercise habits that lead to obesity).

Complexly traumatized youth frequently suffer from body dysregulation, meaning they over-respond or under-respond to sensory stimuli. For example, they may be hypersensitive to sounds, smells, touch or light, or they may suffer from anesthesia and analgesia, in which they are unaware of pain, touch, or internal physical sensations. As a result, they may injure themselves without feeling pain, suffer from physical problems without being aware of them, or, the converse – they may complain of chronic pain in various body areas for which no physical cause can be found.

Emotional Responses

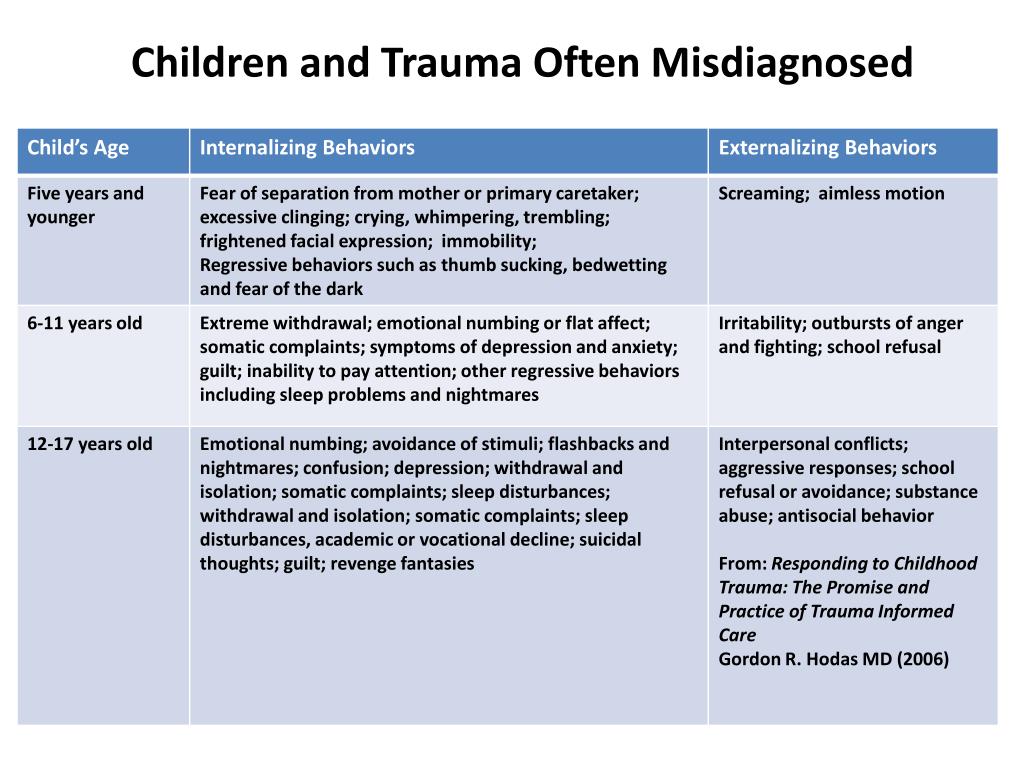

Children who have experienced complex trauma often have difficulty identifying, expressing, and managing emotions, and may have limited language for feeling states. They often internalize and/or externalize stress reactions and as a result may experience significant depression, anxiety, or anger. Their emotional responses may be unpredictable or explosive. A child may react to a reminder of a traumatic event with trembling, anger, sadness, or avoidance. For a child with a complex trauma history, reminders of various traumatic events may be everywhere in the environment. Such a child may react often, react powerfully, and have difficulty calming down when upset. Since the traumas are often of an interpersonal nature, even mildly stressful interactions with others may serve as trauma reminders and trigger intense emotional responses. Having learned that the world is a dangerous place where even loved ones can’t be trusted to protect you, children are often vigilant and guarded in their interactions with others and are more likely to perceive situations as stressful or dangerous. While this defensive posture is protective when an individual is under attack, it becomes problematic in situations that do not warrant such intense reactions.

They often internalize and/or externalize stress reactions and as a result may experience significant depression, anxiety, or anger. Their emotional responses may be unpredictable or explosive. A child may react to a reminder of a traumatic event with trembling, anger, sadness, or avoidance. For a child with a complex trauma history, reminders of various traumatic events may be everywhere in the environment. Such a child may react often, react powerfully, and have difficulty calming down when upset. Since the traumas are often of an interpersonal nature, even mildly stressful interactions with others may serve as trauma reminders and trigger intense emotional responses. Having learned that the world is a dangerous place where even loved ones can’t be trusted to protect you, children are often vigilant and guarded in their interactions with others and are more likely to perceive situations as stressful or dangerous. While this defensive posture is protective when an individual is under attack, it becomes problematic in situations that do not warrant such intense reactions. Alternately, many children also learn to “tune out” (emotional numbing) to threats in their environment, making them vulnerable to revictimization.

Alternately, many children also learn to “tune out” (emotional numbing) to threats in their environment, making them vulnerable to revictimization.

Difficulty managing emotions is pervasive and occurs in the absence of relationships as well. Having never learned how to calm themselves down once they are upset, many of these children become easily overwhelmed. For example, in school they may become so frustrated that they give up on even small tasks that present a challenge. Children who have experienced early and intense traumatic events also have an increased likelihood of being fearful all the time and in many situations. They are more likely to experience depression as well.

Dissociation

Dissociation is often seen in children with histories of complex trauma. When children encounter an overwhelming and terrifying experience, they may dissociate, or mentally separate themselves from the experience. They may perceive themselves as detached from their bodies, on the ceiling, or somewhere else in the room watching what is happening to their bodies. They may feel as if they are in a dream or some altered state that is not quite real or as if the experience is happening to someone else. Or they may lose all memories or sense of the experiences having happened to them, resulting in gaps in time or even gaps in their personal history. At its extreme, a child may cut off or lose touch with various aspects of the self.

They may feel as if they are in a dream or some altered state that is not quite real or as if the experience is happening to someone else. Or they may lose all memories or sense of the experiences having happened to them, resulting in gaps in time or even gaps in their personal history. At its extreme, a child may cut off or lose touch with various aspects of the self.

Although children may not be able to purposely dissociate, once they have learned to dissociate as a defense mechanism they may automatically dissociate during other stressful situations or when faced with trauma reminders. Dissociation can affect a child’s ability to be fully present in activities of daily life and can significantly fracture a child’s sense of time and continuity. As a result, it can have adverse effects on learning, classroom behavior, and social interactions. It is not always evident to others that a child is dissociating and at times it may appear as if the child is simply “spacing out,” daydreaming, or not paying attention.

Behavior

A child with a complex trauma history may be easily triggered or “set off” and is more likely to react very intensely. The child may struggle with self-regulation (i.e., knowing how to calm down) and may lack impulse control or the ability to think through consequences before acting. As a result, complexly traumatized children may behave in ways that appear unpredictable, oppositional, volatile, and extreme. A child who feels powerless or who grew up fearing an abusive authority figure may react defensively and aggressively in response to perceived blame or attack, or alternately, may at times be overcontrolled, rigid, and unusually compliant with adults. If a child dissociates often, this will also affect behavior. Such a child may seem “spacey”, detached, distant, or out of touch with reality. Complexly traumatized children are more likely to engage in high-risk behaviors, such as self-harm, unsafe sexual practices, and excessive risk-taking such as operating a vehicle at high speeds. They may also engage in illegal activities, such as alcohol and substance use, assaulting others, stealing, running away, and/or prostitution, thereby making it more likely that they will enter the juvenile justice system.

They may also engage in illegal activities, such as alcohol and substance use, assaulting others, stealing, running away, and/or prostitution, thereby making it more likely that they will enter the juvenile justice system.

Cognition: Thinking and Learning

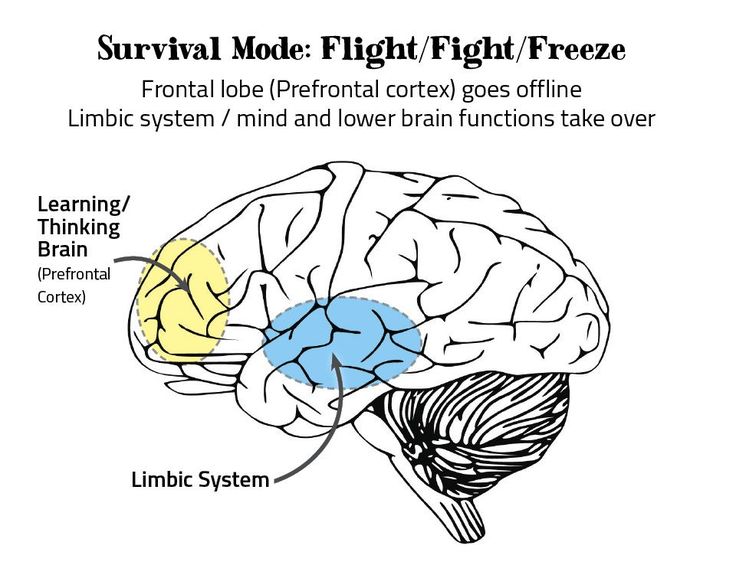

Children with complex trauma histories may have problems thinking clearly, reasoning, or problem solving. They may be unable to plan ahead, anticipate the future, and act accordingly. When children grow up under conditions of constant threat, all their internal resources go toward survival. When their bodies and minds have learned to be in chronic stress response mode, they may have trouble thinking a problem through calmly and considering multiple alternatives. They may find it hard to acquire new skills or take in new information. They may struggle with sustaining attention or curiosity or be distracted by reactions to trauma reminders. They may show deficits in language development and abstract reasoning skills. Many children who have experienced complex trauma have learning difficulties that may require support in the academic environment.

Self-Concept and Future Orientation

Children learn their self-worth from the reactions of others, particularly those closest to them. Caregivers have the greatest influence on a child’s sense of self-worth and value. Abuse and neglect make a child feel worthless and despondent. A child who is abused will often blame him- or herself. It may feel safer to blame oneself than to recognize the parent as unreliable and dangerous. Shame, guilt, low self-esteem, and a poor self-image are common among children with complex trauma histories.

To plan for the future with a sense of hope and purpose, a child needs to value him- or herself. To plan for the future requires a sense of hope, control, and the ability to see one’s own actions as having meaning and value. Children surrounded by violence in their homes and communities learn from an early age that they cannot trust, the world is not safe, and that they are powerless to change their circumstances. Beliefs about themselves, others, and the world diminish their sense of competency. Their negative expectations interfere with positive problem-solving, and foreclose on opportunities to make a difference in their own lives. A complexly traumatized child may view himself as powerless, “damaged,” and may perceive the world as a meaningless place in which planning and positive action is futile. They have trouble feeling hopeful. Having learned to operate in “survival mode,” the child lives from moment-to-moment without pausing to think about, plan for, or even dream about a future.

Their negative expectations interfere with positive problem-solving, and foreclose on opportunities to make a difference in their own lives. A complexly traumatized child may view himself as powerless, “damaged,” and may perceive the world as a meaningless place in which planning and positive action is futile. They have trouble feeling hopeful. Having learned to operate in “survival mode,” the child lives from moment-to-moment without pausing to think about, plan for, or even dream about a future.

Long-Term Health Consequences

Traumatic experiences in childhood have been linked to increased medical conditions throughout the individuals’ lives. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study is a longitudinal study that explores the long-lasting impact of childhood trauma into adulthood. The ACE Study includes over 17,000 participants ranging in age from 19 to 90. Researchers gathered medical histories over time while also collecting data on the subjects’ childhood exposure to abuse, violence, and impaired caregivers. Results indicated that nearly 64% of participants experienced at least one exposure, and of those, 69% reported two or more incidents of childhood trauma. Results demonstrated the connection between childhood trauma exposure, high-risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, unprotected sex), chronic illness such as heart disease and cancer, and early death.

Results indicated that nearly 64% of participants experienced at least one exposure, and of those, 69% reported two or more incidents of childhood trauma. Results demonstrated the connection between childhood trauma exposure, high-risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, unprotected sex), chronic illness such as heart disease and cancer, and early death.

Economic Impact

The cumulative economic and social burden of complex trauma in childhood is extremely high. Based upon data from a variety of sources, a conservative annual cost of child abuse and neglect is an estimated $103.8 billion, or $284.3 million per day (in 2007 values). This number includes both direct costs—about $70.7 billion—which include the immediate needs of maltreated children (hospitalization, mental health care, child welfare systems, and law enforcement) and also indirect costs—about $33.1 billion—which are the secondary or long-term effects of child abuse and neglect (special education, juvenile delinquency, mental health and health care, adult criminal justice system, and lost productivity to society).

A recent study examining confirmed cases of child maltreatment in the United States found the estimated total lifetime costs associated with child maltreatment over a 12-month period to be $124 billion. In the 1,740 fatal cases of child maltreatment, the estimated cost per case was $1.3 million, including medical expenses and productivity loss. For the 579,000 non-fatal cases, the estimated average lifetime cost per victim of child maltreatment was $210,012, which includes costs relating to health care throughout the lifespan, productivity losses, child welfare, criminal justice, and special education. Costs for these nonfatal cases of child maltreatment are comparable to other high-cost health conditions (i.e., $159,846 for stroke victims and $181,000 to $253,000 for those with Type 2 diabetes).

In addition to these costs are the “intangible losses” of pain, sorrow, and reduced quality of life to victims and their families. Such immeasurable losses may be the most significant cost of child maltreatment.

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

How Early Childhood Trauma Is Unique

Traumatic events have a profound sensory impact on young children. Their sense of safety may be shattered by frightening visual stimuli, loud noises, violent movements, and other sensations associated with an unpredictable, frightening event. The frightening images tend to recur in the form of nightmares, new fears, and actions or play that reenact the event. Lacking an accurate understanding of the relationship between cause and effect, young children believe that their thoughts, wishes, and fears have the power to become real and can make things happen. Young children are less able to anticipate danger or to know how to keep themselves safe, and so are particularly vulnerable to the effects of exposure to trauma. A 2-year-old who witnesses a traumatic event like his mother being battered may interpret it quite differently from the way a 5-year-old or an 11-year-old would. Children may blame themselves or their parents for not preventing a frightening event or for not being able to change its outcome. These misconceptions of reality compound the negative impact of traumatic effects on children's development.

These misconceptions of reality compound the negative impact of traumatic effects on children's development.

Young children who experience trauma are at particular risk because their rapidly developing brains are very vulnerable. Early childhood trauma has been associated with reduced size of the brain cortex. This area is responsible for many complex functions including memory, attention, perceptual awareness, thinking, language, and consciousness. These changes may affect IQ and the ability to regulate emotions, and the child may become more fearful and may not feel as safe or as protected.

Young children depend exclusively on parents/caregivers for survival and protection—both physical and emotional. When trauma also impacts the parent/caregiver, the relationship between that person and the child may be strongly affected. Without the support of a trusted parent/caregiver to help them regulate their strong emotions, children may experience overwhelming stress, with little ability to effectively communicate what they feel or need. They often develop symptoms that parents/caregivers don't understand and may display uncharacteristic behaviors that adults may not know how to appropriately respond to.

They often develop symptoms that parents/caregivers don't understand and may display uncharacteristic behaviors that adults may not know how to appropriately respond to.

Symptoms and Behaviors

As with older children, young children experience both behavioral and physiological symptoms associated with trauma. Unlike older children, young children cannot express in words whether they feel afraid, overwhelmed, or helpless. Young children suffering from traumatic stress symptoms generally have difficulty regulating their behaviors and emotions. They may be clingy and fearful of new situations, easily frightened, difficult to console, and/or aggressive and impulsive. They may also have difficulty sleeping, lose recently acquired developmental skills, and show regression in functioning and behavior.

| Children aged 0-2 exposed to trauma may | Children aged 3-6 exposed to trauma may |

|---|---|

|

|

Protective Factors: Enhancing Resilience

The effects of traumatic experiences on young children are sobering, but not all children are affected in the same way, nor to the same degree. Children and families possess competencies, psychological resources, and resilience--often even in the face of significant trauma--that can protect them from long-term harm. Research on resilience in children demonstrates that an essential protective factor is the reliable presence of a positive, caring, and protective parent or caregiver, who can help shield children against adverse experiences. They can be a consistent resource for their children, encouraging them to talk about their experiences, and they can provide reassurance to their children that the adults in their lives are working to keep them safe.

The impact of physical trauma on the mental development of children

home

Parents

How to raise a child?

The impact of physical trauma on the mental development of children

- Tags:

- Expert advice

- 1-3 years

- 3-7 years

- 7-12 years old

- mental development

The inner world of a child consists of bright, happy and dear pictures. Unfortunately, one day, trauma can invade a joyful and serene existence. A road accident or a terrorist attack, a severe burn or one's own illness, the death of a loved one or his illness ... Terrible, cruel and ridiculous, always unexpected, an injury brings with it physical losses, which, against the background of an experienced threat to life, are often accompanied by psychological trauma.

Unfortunately, one day, trauma can invade a joyful and serene existence. A road accident or a terrorist attack, a severe burn or one's own illness, the death of a loved one or his illness ... Terrible, cruel and ridiculous, always unexpected, an injury brings with it physical losses, which, against the background of an experienced threat to life, are often accompanied by psychological trauma.

Post-traumatic stress disorder may be accompanied by depression, somatic complaints, phobias, conduct disorder (aggressiveness), eating and sleep problems. At the same time, children are afraid to be alone and require the constant presence of an adult. They avoid visiting places associated with the tragedy, and any slight hint of trauma causes them violently expressed negativism or other symptoms (for example, complaints of abdominal pain, etc.). The consequences of psychological trauma are also manifested in the child's play activity, which in these cases is characterized by regressive and stereotypical elements with an obsessively repetitive plot, one way or another connected with the tragedy (playing in the house with elements of the death of one of the members of the puppet family, playing "friends" with their absence, etc. ). At the same time, the child’s range of interests sharply narrows, which is characterized by such statements: “I don’t play outdoor games anymore, because I’m not lucky anyway.” Subsequently, alienation and a desire for loneliness appear. All this ultimately leads to a regression in the mental development of the child. The regressive trend often affects the development of the child, school performance decreases, attention problems appear, excessive looseness, panic states, excessive alertness and tension.

). At the same time, the child’s range of interests sharply narrows, which is characterized by such statements: “I don’t play outdoor games anymore, because I’m not lucky anyway.” Subsequently, alienation and a desire for loneliness appear. All this ultimately leads to a regression in the mental development of the child. The regressive trend often affects the development of the child, school performance decreases, attention problems appear, excessive looseness, panic states, excessive alertness and tension.

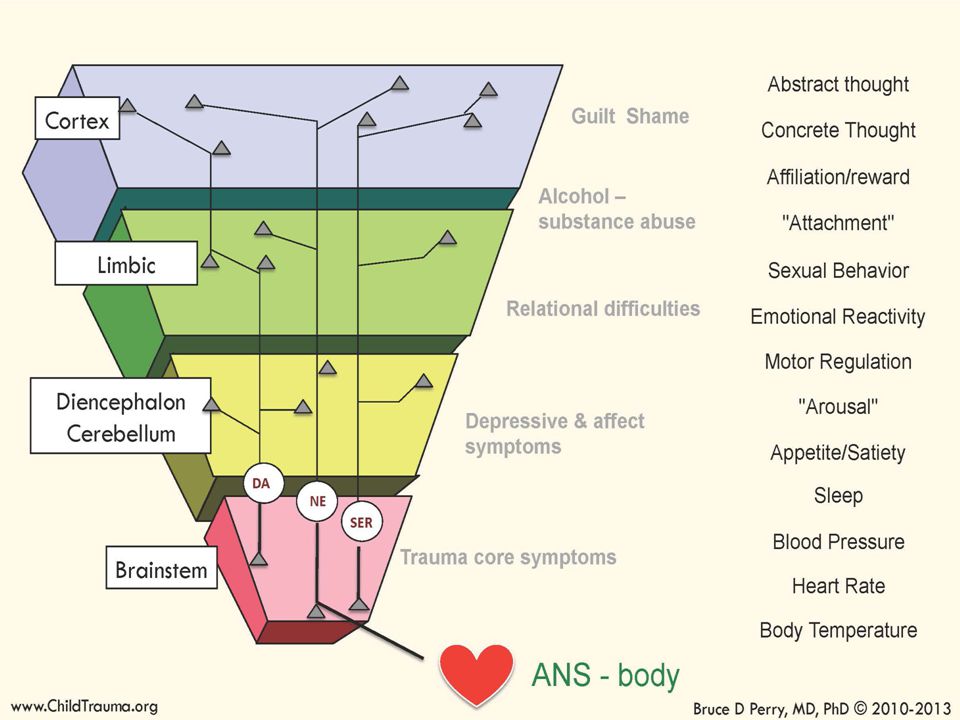

The physiology of psychological trauma boils down to the fact that in a normal, non-stressful situation, any person in the cerebral cortex processes external stimuli, thus there is a constant "monitoring" of the situation with its full awareness and control. In a stressful situation (including acquired physical trauma), and in the face of mortal danger, the human body does not have time for the usual processing of information through the cerebral cortex. And then more simple and primitive, instinctive protective mechanisms of behavior are triggered, controlled by the lower subcortical parts of the brain (subcortex of the brain), which carry out endocrine regulation and control of emotional reactions and states. This mechanism can be denoted by the well-known in psychology phrase ''fight or flight'' (fight or fly away). This reaction of the human body to danger is normal and protective. A painful condition in a child can occur only when his body, as it were, "fixes" on this kind of reaction and perceives any situation as stressful.

This mechanism can be denoted by the well-known in psychology phrase ''fight or flight'' (fight or fly away). This reaction of the human body to danger is normal and protective. A painful condition in a child can occur only when his body, as it were, "fixes" on this kind of reaction and perceives any situation as stressful.

In some cases, especially if the child was directly involved in the tragic event, he often develops post-traumatic stress. At the same time, he is haunted by obsessive and often repeated terrible pictures of the tragedy, which he is not able to get rid of; constantly tormented by nightmares, feelings of anxiety and anxiety.

Misha is 4 years old. His disease - cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus, arose from the fact that the parents paid little attention to the child, and he drank a liquid poisoning the body ... Naturally, hospitals, doctors, operations with many anesthesia appeared in the child's life, which influenced the development of various kinds of fears. The child is afraid to go to bed, afraid of the process of falling asleep. He stopped trusting his relatives, does not make tactile contact with his parents. Subsequently, all this led to the fact that aggression began to predominate in the child's play activity in most cases ... In such a situation, parents do not have to wait for immediate help from a psychologist, since the child needs to get used to him.

The child is afraid to go to bed, afraid of the process of falling asleep. He stopped trusting his relatives, does not make tactile contact with his parents. Subsequently, all this led to the fact that aggression began to predominate in the child's play activity in most cases ... In such a situation, parents do not have to wait for immediate help from a psychologist, since the child needs to get used to him.

For such a child, it is the psychologist who should become, in a way, a big wise friend, to whom the child, getting used to, can touch, hug, play with and entrust all his secrets. The work of such a plan has a long-term character, but it is precisely its earlier start that helps to increase its productivity. All this taken together, as well as the above-described features of children's response to a defect, lead to malfunctions in the usual functioning of the body, paralyze life and destroy the child's personality.

Yulia is 14 years old. Until the age of 12, Yulia was an ordinary healthy child: she went to school, talked with friends. The transferred cold influenced the fact that Yulia developed a disease of the musculoskeletal system: rheumatoid arthritis. This situation was complicated by the fact that the girl is in adolescence, which has its own experiences, the presence of its own inner world and attitudes towards everything that happens. So, Julia withdrew into herself and left contacts with her peers. The girl was promptly assisted by a psychologist, as a result of which she began to adequately perceive herself with her own characteristics of the disease.

The transferred cold influenced the fact that Yulia developed a disease of the musculoskeletal system: rheumatoid arthritis. This situation was complicated by the fact that the girl is in adolescence, which has its own experiences, the presence of its own inner world and attitudes towards everything that happens. So, Julia withdrew into herself and left contacts with her peers. The girl was promptly assisted by a psychologist, as a result of which she began to adequately perceive herself with her own characteristics of the disease.

A child can experience psychological shock, even if he was only an eyewitness to a tragic event (physical injury to another loved one), and not a direct participant in it. At the same time, the strength of his emotions is so high that it knocks down all the well-established mechanisms of psychological defense. The child disappears as a sense of security and integrity of his own body, as well as a sense of confidence in himself and in loved ones. Fortunately, for most of the children, especially for those who were not direct participants in the tragedy, the consequences of such an event can be limited to a natural reaction of fear. After a while, these children return to normal life, accepting losses as an integral part of this life, and learn to distract from them. The acquired physical defect is especially acutely experienced by the child. A child's perception of an event as traumatic is very individual and depends on his personality, the degree of involvement in this event, his previous experience of perceiving and overcoming the consequences of a physical defect and dramatic situations.

After a while, these children return to normal life, accepting losses as an integral part of this life, and learn to distract from them. The acquired physical defect is especially acutely experienced by the child. A child's perception of an event as traumatic is very individual and depends on his personality, the degree of involvement in this event, his previous experience of perceiving and overcoming the consequences of a physical defect and dramatic situations.

Many parents whose child has suffered a trauma do not understand the meaning and need for psychological help. They think and say something like this: “Well, you have become attached to the child, let him come to his senses! And, in general, there is no need for him to remember this horror! It may be easier not to talk or remember about the tragic incident, but this creates the preconditions for the “raw” fear to settle in the child’s soul for a long time, and maybe forever! This is due to the peculiarities of the perception of young children. Adults tend to believe that small children do not understand anything about what is happening around them and cannot react like older children and adults to various stressful situations, and therefore they carefully hide the true state of things from children. This situation in psychology is called the "veiled" problem. Thus, significant adults begin to attribute to the child features and character traits that he did not possess before the acquisition of physical trauma, and does not possess after its occurrence. At the same time, the problems that have arisen in a child are carefully hidden from him, veiled by his parents, which in turn leaves an indelible imprint on the formation of his personality and the pattern of behavioral manifestations. Such a child is not ready to fight for his place in the sun, with his own trauma, but, on the contrary, expects a miracle, like in a fairy tale. In the future, this situation will also affect the behavior of an adult formed person, who will look everywhere and everywhere for easier ways to solve certain problems.

Adults tend to believe that small children do not understand anything about what is happening around them and cannot react like older children and adults to various stressful situations, and therefore they carefully hide the true state of things from children. This situation in psychology is called the "veiled" problem. Thus, significant adults begin to attribute to the child features and character traits that he did not possess before the acquisition of physical trauma, and does not possess after its occurrence. At the same time, the problems that have arisen in a child are carefully hidden from him, veiled by his parents, which in turn leaves an indelible imprint on the formation of his personality and the pattern of behavioral manifestations. Such a child is not ready to fight for his place in the sun, with his own trauma, but, on the contrary, expects a miracle, like in a fairy tale. In the future, this situation will also affect the behavior of an adult formed person, who will look everywhere and everywhere for easier ways to solve certain problems.

Yes, indeed, due to their still immature intellect, young children are unable to comprehend the degree of danger to which they or their loved ones are exposed. But due to their special attachment to their mother and other relatives, they are very sensitive to their emotional state and it is through the prism of the emotions of loved ones that they perceive the situation as dangerous or not dangerous. Attempts to completely hide the essence of what happened from the child can lead him to a dead end and increase feelings of anxiety. For a small child, the sudden disappearance of loved ones, especially the mother, or their long absence is a stressful factor in itself, and in the event of an injury or illness of the mother, it is doubly stressful. As a rule, the reaction of children to stress is manifested in changes in the nature of their motor activity, appetite and sleep. In many ways, the situation of overcoming physical trauma depends on the behavior of the parents themselves. It is very often difficult for parents to distinguish between a child’s natural fear reaction and a pathological one, so many of them do not seek help from a psychologist for a long time after a trauma. They very emotionally and hard accept the physical trauma of the child, deeply empathizing with him, and even identify themselves with him, or, conversely, fall into a depressive state. Because of this, parents are unable to adequately assess the emotional state of their own child. They only fix changes in his emotional state, but do not connect them with the trauma that has occurred; often hide the history of trauma from psychologists, not attaching much importance to it, or because of a sense of their own guilt, as a result of which they lose valuable time needed to restore the child's psyche. When the external protection in the face of the parents breaks down, the child is forced to defend himself. If he can’t cope with this, then he sends an SOS signal so that at least someone pays attention to him. And then he either starts to stutter, or becomes very aggressive, or starts to eat or sleep badly.

It is very important that primary psychological assistance in one or another optimal form chosen by the specialist be provided immediately after the injury in order to increase the degree of awareness of what happened in the affected child. It is important for parents to know: the more often the psychologist and the child return to the situation that caused the physical injury, the easier it is for the child to get rid of the often occurring fears and consequences of physical injury. If such work is carried out simultaneously, or in a remote period, its effectiveness is reduced. This is due to the fact that to some extent the child has already experienced this or that traumatic situation on his own. The consequences of such experiences lead to the fact that the child withdraws into himself and, at times, the impact of the psychologist on the emotional state of the child does not bring the desired results. In the language of physiology, awareness of what happened, as it were, allows you to “move” fears from the lower parts of the brain directly into the cerebral cortex itself, which makes them (fears) more amenable to subsequent psycho-correction.

It is important for parents to know: the more often the psychologist and the child return to the situation that caused the physical injury, the easier it is for the child to get rid of the often occurring fears and consequences of physical injury. If such work is carried out simultaneously, or in a remote period, its effectiveness is reduced. This is due to the fact that to some extent the child has already experienced this or that traumatic situation on his own. The consequences of such experiences lead to the fact that the child withdraws into himself and, at times, the impact of the psychologist on the emotional state of the child does not bring the desired results. In the language of physiology, awareness of what happened, as it were, allows you to “move” fears from the lower parts of the brain directly into the cerebral cortex itself, which makes them (fears) more amenable to subsequent psycho-correction.

All this convincingly shows that trauma causes great damage to the mental development of the child. Affected children (as well as adults), having experienced trauma once, need special assistance, including both drug treatment and various types of psychotherapy (depending on the age and individual characteristics of the patient). Timely psychological assistance can become a trigger for the development of a full-fledged personality, capable of independently overcoming various difficult life situations in the future.

Affected children (as well as adults), having experienced trauma once, need special assistance, including both drug treatment and various types of psychotherapy (depending on the age and individual characteristics of the patient). Timely psychological assistance can become a trigger for the development of a full-fledged personality, capable of independently overcoming various difficult life situations in the future.

Yuliya Krivodonova

What are childhood "traumas" and how to recognize them in adulthood

When a parent limits a child in contact with others and controls his social circle, the child may feel lonely, isolated from the outside world. Under such conditions, socialization and the development of independence are impossible. With verbal aggression and threats (for example, "I will refuse you"), the child will cease to trust the world and begin to perceive everything as hostile.

If parents themselves grew up in violence, then these destructive patterns can automatically be transferred to their attitude towards children. Therefore, it is first of all important to recognize and correct your own experience.

Therefore, it is first of all important to recognize and correct your own experience.

We are made up of the behavior patterns of our parents.

“Sexual abuse is not only a sexual act, but also a neglectful attitude of parents towards a child's sexuality,” explains Veronica. This can lead to rejection of one's body, cause repeated violence (a person can either commit it himself or again find himself in the role of a victim). “If the child’s physical and psychological boundaries are violated, this affects his entire adult life, and the negative experience will be repeated again and again,” says Irina.

Why do we not remember some traumatic childhood events?

“When a person is traumatized in childhood, he represses it later in life. Thus, the psyche is protected, blocks painful information, ”explains Irina Mansurova. But even without remembering the causes of the injury, an adult will still feel its consequences - depression, guilt, etc. “The child also needs to somehow adapt, and one of the ways to do this is to dissociate the situation. For example, a child lives with parents who are addicted to alcohol. He has nowhere else to live - what will he do? Dissociate and anesthetize the affected part of the soul. It will block some memories, thoughts and images, as this reduces pain sensitivity. Subsequently, such people do not get hurt: they do not feel anything at all. The child gets used not to hear, not to feel and not to see: dissociation allows him to survive, and the psyche will use various methods so as not to collapse, ”says Veronika Doringer.

“The child also needs to somehow adapt, and one of the ways to do this is to dissociate the situation. For example, a child lives with parents who are addicted to alcohol. He has nowhere else to live - what will he do? Dissociate and anesthetize the affected part of the soul. It will block some memories, thoughts and images, as this reduces pain sensitivity. Subsequently, such people do not get hurt: they do not feel anything at all. The child gets used not to hear, not to feel and not to see: dissociation allows him to survive, and the psyche will use various methods so as not to collapse, ”says Veronika Doringer.

Repression

Often a severely traumatized person represses some or all of their past. He simply cannot remember events from his childhood, sometimes only some strongly emotionally charged events come up in his memory.

Loss of trust in the world

Avoidance of any trusting relationship. The logic of this choice is simple: "If there is no relationship, then I can avoid pain. " Such a person eschews even friendship because of the anxiety that he will be betrayed, therefore he deliberately avoids intimacy, which over time can lead to loneliness and depression. Any harbinger of emotional intimacy that can cause psychic pain will be blocked.

" Such a person eschews even friendship because of the anxiety that he will be betrayed, therefore he deliberately avoids intimacy, which over time can lead to loneliness and depression. Any harbinger of emotional intimacy that can cause psychic pain will be blocked.

Tendency to toxic relationships

People who were severely traumatized as children often enter into destructive relationships as adults. Their partners may be emotionally unavailable, married, violent, or have a narcissistic personality disorder. After ending one toxic relationship, a person will be drawn into others, attracting such partners over and over again. To get out of the vicious circle will help work through the trauma with a psychotherapist.

Difficulties with perception of other people's emotions

A person cannot recognize the true emotions and feelings of another person, because he projects his thoughts and feelings onto him.

How to start working with childhood trauma?

“When people with traumatic experiences raise their children, they are brought back to their traumas. They remember how their parents acted in any situations and do not understand their actions,” explains Veronica. Experiencing once again a painful experience, it is difficult to be emotionally included. Therefore, it is important that the parent first learns to help himself. Working through trauma is a long-term process that requires precision and subtlety. One of the best ways is Gestalt therapy. No short-term approaches, webinars and courses will help get rid of psychological trauma: a couple of meetings will not be able to heal, on the contrary, you can aggravate the situation. This should be done by a qualified psychotherapist.

They remember how their parents acted in any situations and do not understand their actions,” explains Veronica. Experiencing once again a painful experience, it is difficult to be emotionally included. Therefore, it is important that the parent first learns to help himself. Working through trauma is a long-term process that requires precision and subtlety. One of the best ways is Gestalt therapy. No short-term approaches, webinars and courses will help get rid of psychological trauma: a couple of meetings will not be able to heal, on the contrary, you can aggravate the situation. This should be done by a qualified psychotherapist.

It's never too late to start working on yourself if you feel you need help. You should not go to a specialist, even if you had a traumatic experience as a child, but nothing bothers you as an adult, which means that your psyche has coped with it. It often happens that people who talk about having childhood trauma actually don't have it. A person with such an experience will not talk about it, and sometimes he does not even understand that something happened in his childhood that left an imprint in his mind.