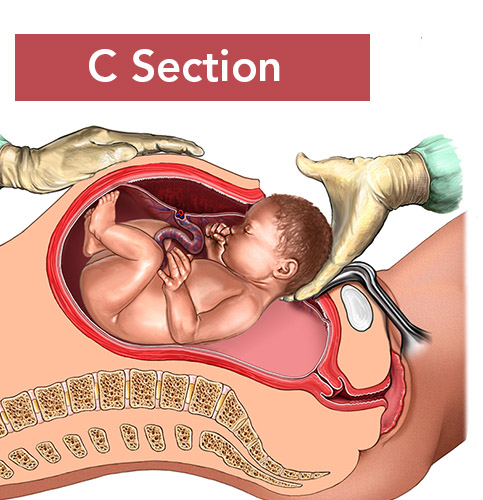

C section name

cesarean section | Description, History, & Risks

- Related Topics:

- birth surgery

See all related content →

Summary

Read a brief summary of this topic

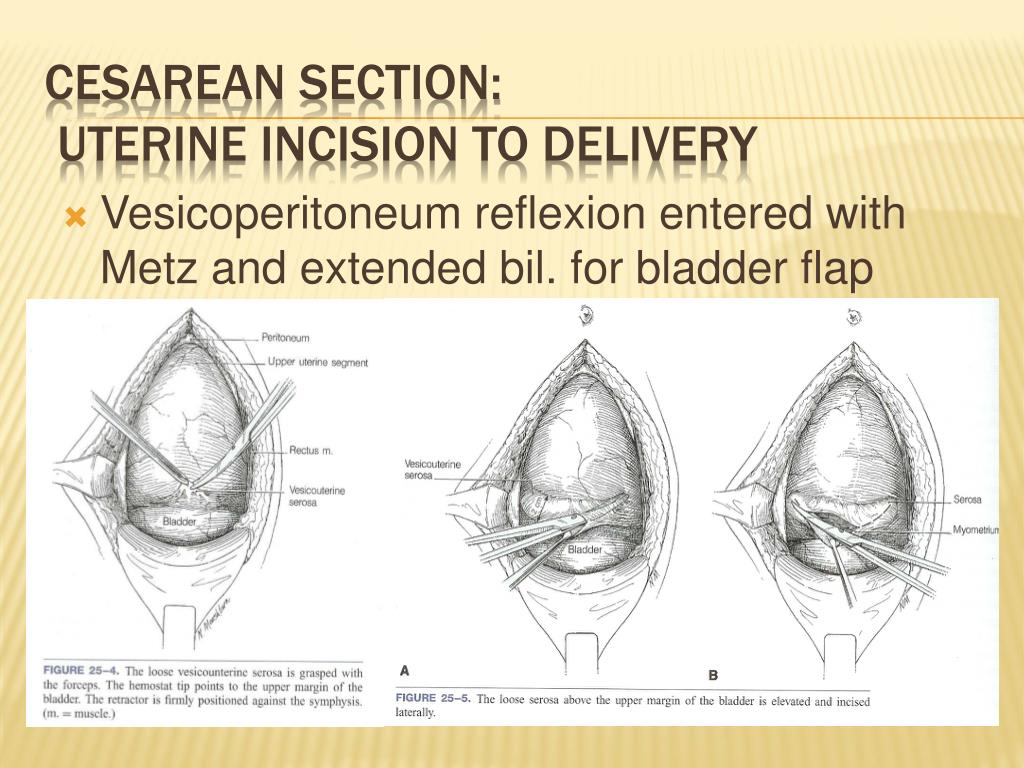

cesarean section, also called C-section, cesarean also spelled caesarian, surgical removal of a fetus from the uterus through an abdominal incision.

History

Little is known of either the origin of the term or the history of the procedure. According to ancient sources, whose veracity has been challenged, the procedure takes its name from a branch of the ancient Roman family of the Julii whose cognomen, Caesar (Latin caedere, “to cut”), originated from a birth by this means. Roman law (Lex Caesarea) mandated the cutting out from the womb a child whose mother had died during labour. A common misperception holds that Julius Caesar himself was born in this fashion. However, since Caesar’s mother, Aurelia, is believed to have been alive when he was a grown man, it is widely held that he could not have been born in this way. The law was followed initially to comply with Roman ritual and religious custom, which forbade the burial of pregnant women, but the procedure was later pursued specifically in an attempt to save the child’s life.

Read More on This Topic

birth: Cesarean section

When a child cannot be delivered through the vagina, it may be necessary to resort to cesarean section, a procedure in...

The first documented cesarean section on a living woman was performed in 1610; she died 25 days after the surgery. Abdominal delivery was subsequently tried in many ways and under many conditions, but it almost invariably resulted in the death of the mother from sepsis (infection) or hemorrhage (bleeding). Even in the first half of the 19th century, the recorded mortality was about 75 percent, and fetal craniotomy—in which the life of the child is sacrificed to save that of the mother—was usually preferred. Eventually, however, improvements in surgical techniques, antibiotics, and blood transfusion and antiseptic procedures so reduced the mortality that cesarean section came to be frequently performed as an alternative to normal childbirth.

Eventually, however, improvements in surgical techniques, antibiotics, and blood transfusion and antiseptic procedures so reduced the mortality that cesarean section came to be frequently performed as an alternative to normal childbirth.

Medical uses

In modern obstetrical care, cesarean section usually is performed when the life of either the mother or the child would be endangered by attempting normal delivery. The medical decision is based on physical examination, special tests, and patient history. The examination includes consideration of any diseases the mother may have had in the past and disorders that may have arisen because of pregnancy. Special tests that might be performed include fetal scalp blood analysis and fetal heart rate monitoring. Common indications for cesarean section include obstructed labour, failure of labour to progress, placenta praevia (development of the placenta in an abnormally low position near the cervix), fetal distress, gestational diabetes mellitus, and improper positioning of the fetus for delivery. In addition, cesarean section is often used if the birth canal is too small for normal delivery. Sometimes when a woman has had a child by cesarean section, any children born after the first cesarean section are also delivered by that method, but vaginal delivery is often possible.

In addition, cesarean section is often used if the birth canal is too small for normal delivery. Sometimes when a woman has had a child by cesarean section, any children born after the first cesarean section are also delivered by that method, but vaginal delivery is often possible.

Risks

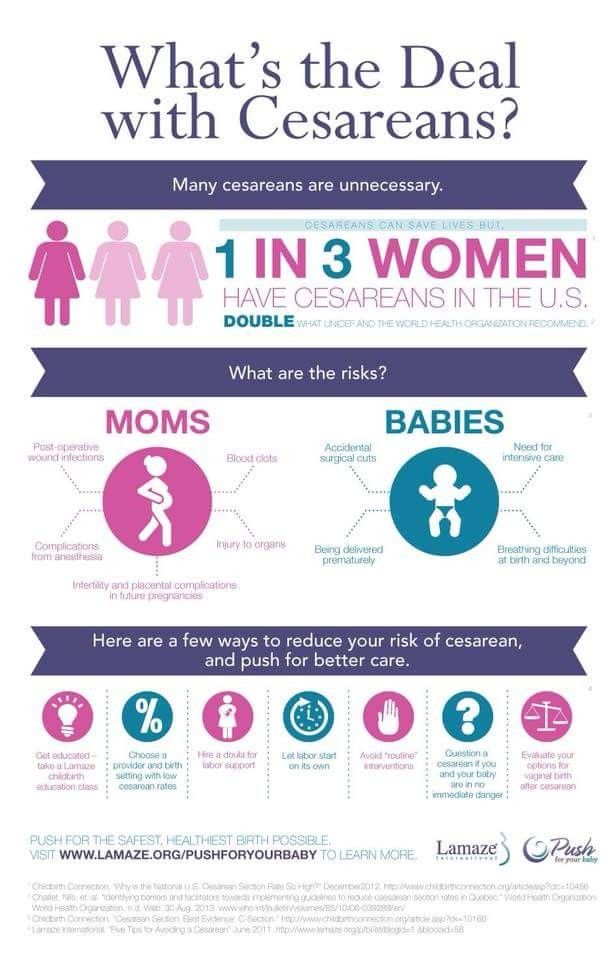

The risks of cesarean section are low but real. The operation constitutes major surgery. Compared with the risks of normal vaginal delivery, it is more dangerous for the mother. The risk of complications—such as infection, hemorrhage, blood clots, and injury to the bladder or intestines—is greater. If the baby is delivered by cesarean section planned in advance of labour, the infant can be premature, and it has been suggested that elective cesarean section may rob the infant of hormones and other substances released by the mother during labour. Researchers have also identified a correlation between infant birth by cesarean section and increased risk of asthma and childhood obesity.

In addition, infants born by cesarean section have been shown to harbour atypical types of bacteria in the gut relative to babies born vaginally. These atypical bacterial populations frequently include potentially harmful microorganisms that are a common cause of opportunistic infections in hospital environments. Although, over time, the microbiome in affected infants becomes more similar to that in infants delivered vaginally, early differences in the microbiome may impact infant health or contribute to health issues that arise later.

These atypical bacterial populations frequently include potentially harmful microorganisms that are a common cause of opportunistic infections in hospital environments. Although, over time, the microbiome in affected infants becomes more similar to that in infants delivered vaginally, early differences in the microbiome may impact infant health or contribute to health issues that arise later.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

Issues

In 1985 the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended an optimal cesarean section rate of 10 to 15 percent within a given population; if performed above this rate, the procedure was found by WHO to place an excessive burden on the resources necessary for the proper prenatal and postnatal care of mother and child, thereby increasing the number of women and infants exposed to the risks associated with the operation. Despite the recommendations set forth by WHO, by the late 20th century the incidence of cesarean section in the United States had risen dramatically, largely as a result of an increase in the number of malpractice suits brought against obstetricians for failing to operate if there was an indication of trouble in delivery. In the first decade of the 21st century, the rate of cesarean section far exceeded WHO’s recommendation in many other countries as well, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, France, and Italy. The rate had also increased in countries such as India, China, and Brazil.

In the first decade of the 21st century, the rate of cesarean section far exceeded WHO’s recommendation in many other countries as well, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, France, and Italy. The rate had also increased in countries such as India, China, and Brazil.

This article was most recently revised and updated by Kara Rogers.

Cesarean Section - A Brief History: Part 1

Cesarean section has been part of human culture since ancient times and there are tales in both Western and non-Western cultures of this procedure resulting in live mothers and offspring. According to Greek mythology Apollo removed Asclepius, founder of the famous cult of religious medicine, from his mother's abdomen. Numerous references to cesarean section appear in ancient Hindu, Egyptian, Grecian, Roman, and other European folklore. Ancient Chinese etchings depict the procedure on apparently living women. The Mischnagoth and Talmud prohibited primogeniture when twins were born by cesarean section and waived the purification rituals for women delivered by surgery.

The Mischnagoth and Talmud prohibited primogeniture when twins were born by cesarean section and waived the purification rituals for women delivered by surgery.

The extraction of Asclepius from the abdomen of his mother Coronis by his father Apollo. Woodcut from the 1549 edition of Alessandro Beneditti's De Re Medica.

Yet, the early history of cesarean section remains shrouded in myth and is of dubious accuracy. Even the origin of "cesarean" has apparently been distorted over time. It is commonly believed to be derived from the surgical birth of Julius Caesar, however this seems unlikely since his mother Aurelia is reputed to have lived to hear of her son's invasion of Britain. At that time the procedure was performed only when the mother was dead or dying, as an attempt to save the child for a state wishing to increase its population. Roman law under Caesar decreed that all women who were so fated by childbirth must be cut open; hence, cesarean. Other possible Latin origins include the verb "caedare," meaning to cut, and the term "caesones" that was applied to infants born by postmortem operations. Ultimately, though, we cannot be sure of where or when the term cesarean was derived. Until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the procedure was known as cesarean operation. This began to change following the publication in 1598 of Jacques Guillimeau's book on midwifery in which he introduced the term "section." Increasingly thereafter "section" replaced "operation."

Ultimately, though, we cannot be sure of where or when the term cesarean was derived. Until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the procedure was known as cesarean operation. This began to change following the publication in 1598 of Jacques Guillimeau's book on midwifery in which he introduced the term "section." Increasingly thereafter "section" replaced "operation."

One of the earliest printed illustrations of Cesarean section. Purportedly the birth of Julius Caesar. A live infant being surgically removed from a dead woman. From Suetonius' Lives of the Twelve Caesars, 1506 woodcut.

During its evolution cesarean section has meant different things to different people at different times. The indications for it have changed dramatically from ancient to modern times. Despite rare references to the operation on living women, the initial purpose was essentially to retrieve the infant from a dead or dying mother; this was conducted either in the rather vain hope of saving the baby's life, or as commonly required by religious edicts, so the infant might be buried separately from the mother. Above all it was a measure of last resort, and the operation was not intended to preserve the mother's life. It was not until the nineteenth century that such a possibility really came within the grasp of the medical profession.

Above all it was a measure of last resort, and the operation was not intended to preserve the mother's life. It was not until the nineteenth century that such a possibility really came within the grasp of the medical profession.

Cesarean section performed on a living woman by a female practitioner. Miniature from a fourteenth-century "Historie Ancienne."

There were, though, sporadic early reports of heroic efforts to save women's lives. While the Middle Ages have been largely viewed as a period of stagnation in science and medicine, some of the stories of cesarean section actually helped to develop and sustain hopes that the operation could ultimately be accomplished. Perhaps the first written record we have of a mother and baby surviving a cesarean section comes from Switzerland in 1500 when a sow gelder, Jacob Nufer, performed the operation on his wife. After several days in labor and help from thirteen midwives, the woman was unable to deliver her baby. Her desperate husband eventually gained permission from the local authorities to attempt a cesarean. The mother lived and subsequently gave birth normally to five children, including twins. The cesarean baby lived to be 77 years old. Since this story was not recorded until 82 years later historians question its accuracy. Similar skepticism might be applied to other early reports of abdominal delivery þ those performed by women on themselves and births resulting from attacks by horned livestock, during which the peritoneal cavity was ripped open.

The mother lived and subsequently gave birth normally to five children, including twins. The cesarean baby lived to be 77 years old. Since this story was not recorded until 82 years later historians question its accuracy. Similar skepticism might be applied to other early reports of abdominal delivery þ those performed by women on themselves and births resulting from attacks by horned livestock, during which the peritoneal cavity was ripped open.

The female pelvic anatomy. From Andreas Vesalius' De Corporis Humani Fabrica, 1543.

The history of cesarean section can be understood best in the broader context of the history of childbirth and general medicine þ histories that also have been characterized by dramatic changes. Many of the earliest successful cesarean sections took place in remote rural areas lacking in medical staff and facilities. In the absence of strong medical communities, operations could be carried out without professional consultation. This meant that cesareans could be undertaken at an earlier stage in failing labor when the mother was not near death and the fetus was less distressed. Under these circumstances the chances of one or both surviving were greater. These operations were performed on kitchen tables and beds, without access to hospital facilities, and this was probably an advantage until the late nineteenth century. Surgery in hospitals was bedeviled by infections passed between patients, often by the unclean hands of medical attendants. These factors may help to explain such successes as Jacob Nufer's.

Under these circumstances the chances of one or both surviving were greater. These operations were performed on kitchen tables and beds, without access to hospital facilities, and this was probably an advantage until the late nineteenth century. Surgery in hospitals was bedeviled by infections passed between patients, often by the unclean hands of medical attendants. These factors may help to explain such successes as Jacob Nufer's.

By dint of his work in animal husbandry, Nufer also possessed a modicum of anatomical knowledge. One of the first steps in performing any operation is understanding the organs and tissues involved, knowledge that was scarcely obtainable until the modern era. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries with the blossoming of the Renaissance, numerous works illustrated human anatomy in detail. Andreas Vesalius's monumental general anatomical text De Corporis Humani Fabrica, for example, published in 1543, depicts normal female genital and abdominal structures. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries anatomists and surgeons substantially extended their knowledge of the normal and pathological anatomy of the human body. By the later 1800s, greater access to human cadavers and changing emphases in medical education permitted medical students to learn anatomy through personal dissection. This practical experience improved their understanding and better prepared them to undertake operations.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries anatomists and surgeons substantially extended their knowledge of the normal and pathological anatomy of the human body. By the later 1800s, greater access to human cadavers and changing emphases in medical education permitted medical students to learn anatomy through personal dissection. This practical experience improved their understanding and better prepared them to undertake operations.

At the time, of course, this new type of medical education was still only available to men. With gathering momentum since the seventeenth century, female attendants had been demoted in the childbirth arena. In the early 1600s, the Chamberlen clan in England introduced obstetrical forceps to pull from the birth canal fetuses that otherwise might have been destroyed. Men's claims to authority over such instruments assisted them in establishing professional control over childbirth. Over the next three centuries or more, the male-midwife and obstetrician gradually wrested that control from the female midwife, thus diminishing her role.

Section 1. Section name………………………………………..

-

Name subsection……….…………………………………

-

Name subsection...………………………………………...

-

Name point…………………………………………

-

Name point…………………………………………

-

-

Name subsection …………..………………………………

Conclusions…………………………………………………………………….

Section 2. Title of Section………………………………………..

2.1. Subsection title …………………………………………….

2.1.1. Item Name…………………………………………….

2.2. Subsection title …………………………………………….

Conclusions……………………………………………………………………..

Section 3. Title of section……………………………………… …...

3.1. Subsection name……………………………………………..

3.2. Subsection name……………………………………………..

3. 2.1. Item name …………………………………………….

2.1. Item name …………………………………………….

Conclusions…………………………………………………………………….

CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………....

LIST USED LITERATURE……………………....

LIST SOURCES USED……………………...

Optional structural components

LIST OF CONDITIONAL ABBREVIATIONS

GLOSSARY

APPENDIX

Requirements for the design of the main text

Font main text - Times New Roman, 14; section headings - Times New Roman, 14, bold, all caps; subheadings - Times New Roman, 14, bold, normal; paragraph headings - Times New Roman, 14, normal. alignment main text - by width, headings - in the center. Indentation of the first line of the main text 1.25 cm. Initials when specifying surnames must be separated by inseparable spaces (Ctrl+Shift+space), for example: V.I. Vernadsky. Non-breaking spaces the letters ‘g. ’ are separated and ‘v.’ when specifying dates, for example: 1972, XVIII in.).

’ are separated and ‘v.’ when specifying dates, for example: 1972, XVIII in.).

tables, diagrams, drawings and other graphic images are numbered inside each section and subsection. For example, drawing 1.1, table 2.3, etc. In this case, the word table written without abbreviations, and the word drawing shrinking fig. Word table written at the top right of the table. stitching its name is written below. Illustrations and tables should be placed below text immediately after the mention or on next page. Bulky tables and drawings are best placed in applications. Text does not follow saturate with other fonts. Whole illustrative material is being typed in italics; analyzed unit stands out bold . The author and title of the work are submitted in parentheses. For example: " Wide stripes light , still cold, swimming in dewy grass, stretching and with a cheerful air, as if trying show that it did not bother them, steel go to bed by land » (A. Chekhov. Happiness). « Near the cape itself, on the other side of the river, in the water fanged stones , and all the summer time the village is filled with noise, as if they never cease here wind "(V. Astafiev. Starodub).

Chekhov. Happiness). « Near the cape itself, on the other side of the river, in the water fanged stones , and all the summer time the village is filled with noise, as if they never cease here wind "(V. Astafiev. Starodub).

Values language units that are object of study, served in single quotes ‘…’ (the first is typed through Alt + 0145, the second - via Alt + 0146), for example: nogata ‘small monetary unit in ancient Rus'. Quotes are being processed using quotation marks (Russian is used variant of quotes "..."). If the quote contains your inner quotes, then they look like “…” (the first one is typed via Alt+0147, the second via Alt+0148). For example: "The opposition between 'process' and “object” cannot have in linguistics no universal force, no single criterion, not even a clear meaning" [2, p. 168].

Insert section break

Word for Microsoft 365 Word for Microsoft 365 for Mac Word for the web Word 2021 Word 2021 for Mac Word 2019Word 2019 for Mac Word 2016 Word 2016 for Mac Word 2013 Word 2010 Word 2007 Word Starter 2010 More. ..Less

..Less

Section breaks are used to separate and format documents. For example, you can break sections into chapters and add formatting to each chapter, such as columns, columns, and page borders.

Adding a section break

-

Select where to start the new chapter.

-

Navigate to > layout .

-

Select the desired section break type:

-

Next page Section break starts a new section on the next page.

-

Current page Section break starts a new section on the same page. This type of section break is often used to change the number of columns without starting a new page.

-

Even page Section break starts a new section on the next large page.

-

Odd page Section break starts a new section on the next odd page.

-

Important: Office 2010 is no longer supported . Move to Microsoft 365 to work remotely from any device and continue to receive support.

Update

Insert section break

-

Select where to start the new section.

-

Navigate to the Breaks > page of the markup.

-

Section break you want to add:

-

To start a new section on the next page, select Next Page .

-

To start a new section on the current page, select Current Page .

Tip: Continuous section breaks can be used to create pages with different numbers of columns.

-

To start a new section on the next odd or even page, select Even page or Odd page .

-

Inserting a section break

-

Select where to start the new section.

-

Navigate to > markup and select the desired section break type.

-

Next page Start a new section on the next page.

-

Current page Starts a new section on the current page. This section break is useful in documents with columns. It allows you to change the number of columns without starting a new page.

-

Even page Begin a new section on the next even page. For example, if you insert an "Even Page" break at the end of page 3, the next section will start on page 4.

-