When do babies start deep sleeping

Baby sleep: what to expect at 2-12 months

Baby sleep needs

Babies need sleep to grow and develop well. But babies’ sleep needs vary, just as the sleep needs of older children and adults do. Your baby might be doing well with more or less sleep than other babies the same age.

Your baby’s mood and wellbeing is often a good guide to whether your baby is getting enough sleep. If your baby is:

- wakeful and grizzly, they might need more sleep

- wakeful and contented, they’re probably getting enough sleep.

How baby sleep changes from 2 to 12 months

As they get older, babies:

- sleep less in the daytime

- are awake for longer between naps

- have longer night-time sleeps and wake less at night

- need less sleep overall.

2-3 months: what to expect from baby sleep

At this age, babies sleep on and off during the day and night. Most babies sleep for 14-17 hours in every 24 hours.

Young babies sleep in cycles that last 50-60 minutes. In young babies, each cycle is made up of active sleep and quiet sleep. Babies move around and grunt during active sleep, and sleep deeply during quiet sleep.

At the end of each cycle, babies wake up for a little while. They might grizzle or cry. They might need help to settle for the next sleep cycle.

At 2-3 months, babies start developing night and day sleep patterns. This means they tend to start sleeping more during the night.

Around 3 months: what to expect from baby sleep

Babies keep developing night and day sleep patterns.

Their sleep cycles consist of:

- light sleep, when baby wakes easily

- deep sleep, when baby is sound asleep and very still

- dream sleep, when baby is dreaming.

Sleep cycles also get longer, which might mean less waking and resettling during sleep. At this age, some babies might regularly be having longer sleeps at night – for example, 4-5 hours.

Most babies still sleep for 14-17 hours in every 24 hours.

3-6 months: what to expect from baby sleep

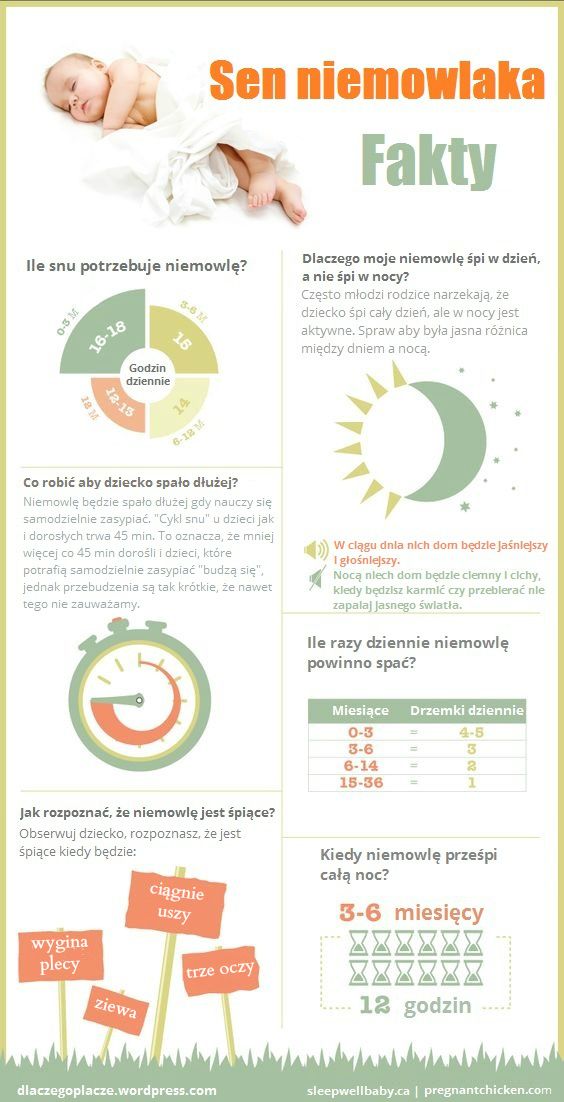

At this age, most babies sleep for 12-15 hours every 24 hours.

Babies might start moving towards a pattern of 2-3 daytime sleeps of up to two hours each.

And night-time sleeps get longer at this age. For example, some babies might be having long sleeps of six hours at night by the time they’re six months old.

But you can expect that your baby will still wake at least once each night.

6-12 months: what to expect from baby sleep

Babies sleep less as they get older. By the time your baby is one year old, baby will probably sleep for 11-14 hours every 24 hours.

Sleep during the night

From about six months, most babies have their longest sleeps at night.

Most babies are ready for bed between 6 pm and 10 pm. They usually take less than 40 minutes to get to sleep, but some babies take longer.

At this age, baby sleep cycles are closer to those of grown-up sleep – which means less waking at night. So your baby might not wake you during the night, or waking might happen less often.

But many babies do wake during the night and need an adult to settle them back to sleep. Some babies do this 3-4 times a night.

Sleep during the day

At this age, most babies are still having 2-3 daytime naps that last for between 30 minutes and 2 hours.

6-12 months: other developments that affect sleep

From around six months, babies develop many new abilities that can affect their sleep or make them more difficult to settle:

- Babies learn to keep themselves awake, especially if something interesting is happening, or they’re in a place with a lot of light and noise.

- Settling difficulties can happen at the same time as crawling. You might notice your baby’s sleep habits changing when baby starts moving around more.

- Babies learn that things exist, even when they’re out of sight. Now that your baby knows you exist when you leave the bedroom, baby might call or cry out for you.

- Separation anxiety is when babies get upset because you’re not around. It might mean your baby doesn’t want to go to sleep and wakes up more often in the night. As babies mature they gradually overcome this worry.

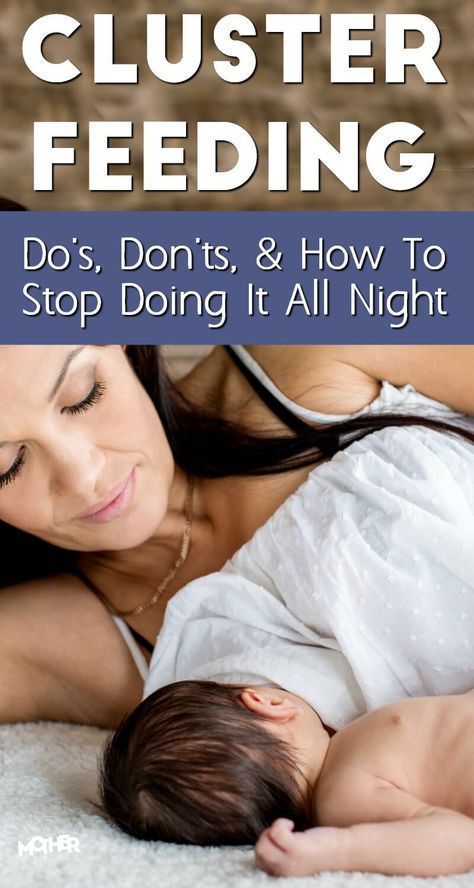

6-12 months: night-time feeding

From around six months of age, if your baby is developing well, it’s OK to think about night weaning and phasing out night feeds. But if you’re comfortable with feeding your baby during the night, there’s no hurry to phase out night feeds.

You can choose what works best for you and your baby.

A rollover feed is a late feed somewhere between 10 pm and midnight. Some parents find that rollover feeds help babies sleep longer towards morning. If this works for you and your baby, it’s fine to give baby a rollover feed.

Concerns about baby sleep

If you’re concerned about your baby’s sleep, it can be a good idea to track your baby’s sleep for a week or so. This can help you get a clear picture of what’s going on.

This can help you get a clear picture of what’s going on.

You can do this by drawing up a simple chart with columns for each day of the week. Divide the days into hourly blocks, and colour the intervals when your baby is asleep. Keep your chart for 5-7 days.

Once completed, the chart will tell you things like:

- when and how much sleep your baby is getting

- how many times your baby is waking during the night

- how long your baby is taking to settle after waking.

You can also record how you tried to resettle your baby and what worked or didn’t work.

Then you can compare the information in your chart with the general information about baby sleep needs above:

- How does your child compare to other babies the same age? If your baby is wakeful and grizzly and getting much less sleep than others, your baby might need more opportunities for sleep.

- How many times is your baby over six months old waking up during the night? If it’s 3-4 times a night or more, you might be feeling very tired.

You might want to think about phasing out some of your baby’s sleep habits.

You might want to think about phasing out some of your baby’s sleep habits.

If you decide you need to see a professional for help with your baby’s sleep, take your chart with you.

If you’re concerned about your baby’s sleep, it’s a very good idea to see a child health professional for help. You could start by talking with your GP or child and family health nurse.

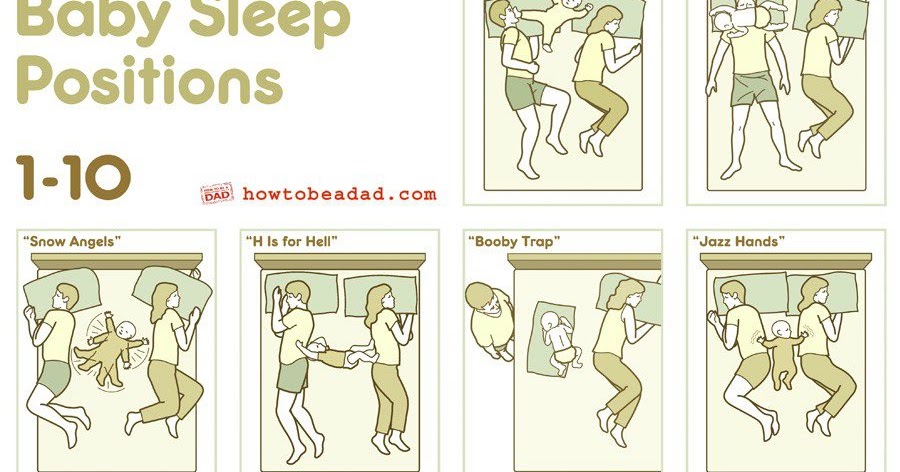

How baby sleep patterns affect grown-ups

Babies and grown-ups need sleep for wellbeing, but babies sleep differently from adults. Most parents of babies under six months of age get up in the night to feed and settle their babies. For many, this keeps going after six months.

Some parents are OK with getting up a lot at night as long as they have enough support and they can catch up on sleep at other times. For others, getting up in the night over the long term has a serious effect on them and their family lives.

The quality of your sleep can affect your health and your mood. Being exhausted can make it hard to give your baby positive attention during the day. And your relationship with your baby and the time and attention you give baby during the day can affect the quality and quantity of baby’s sleep.

And your relationship with your baby and the time and attention you give baby during the day can affect the quality and quantity of baby’s sleep.

So it’s important that you get some help if you’re not getting enough sleep. You could start by asking family or friends for help. And if you feel that lack of sleep is affecting you mentally or emotionally, it’s a very good idea to talk with your GP or another health professional.

There’s a strong link between baby sleep difficulties and symptoms of postnatal depression in women and postnatal depression in men. But the link isn’t there if parents of babies with sleep difficulties are getting enough sleep themselves.

Languages other than English

- Arabic (PDF: 471kb)

- Dari (PDF: 469kb)

- Karen (PDF: 298kb)

- Persian (PDF: 420kb)

- Simplified Chinese (PDF: 502kb)

- Vietnamese (PDF: 324kb)

Baby sleep patterns for the science-minded

© 2018 Gwen Dewar, Ph.

D., all rights reserved

D., all rights reservedBaby sleep patterns vary from infant to infant, and they change over time. So there is no one, universal chart or instruction manual that can predict when and how your baby will sleep.

But scientific research can help us understand the range of variation, and the general trends.

Here I provide a timeline of quick facts, followed by a longer article that will help you understand what can speed up — or slow down — the development of baby sleep patterns.

I’ll also help answer questions like “how much sleep does a baby need?” and “when do babies start sleeping through the night?”

A developmental timeline of baby sleep patterns

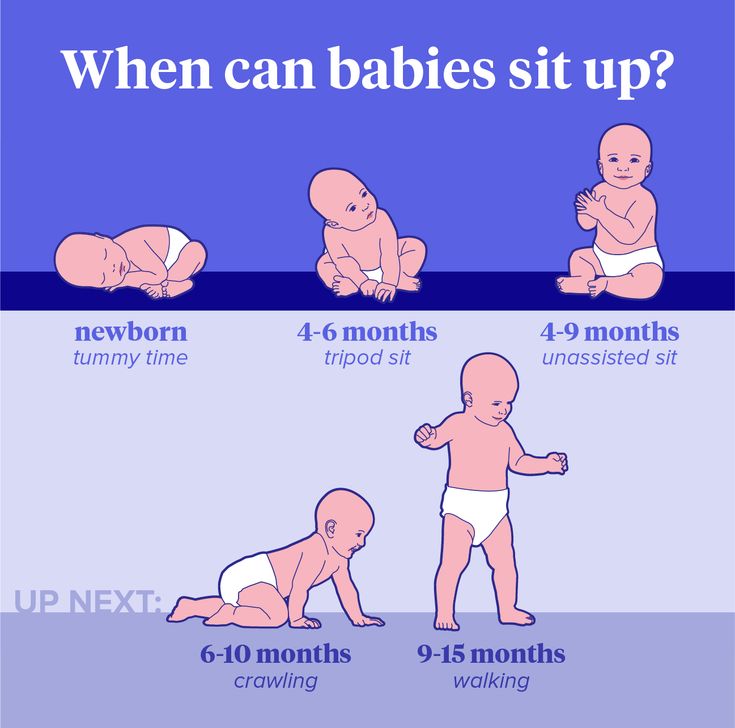

0-3 months. Newborns sleep in short bouts scattered throughout the 24-hour day. As the days pass, they gradually develop a tendency to sleep more at night.

Total sleep duration varies; about half of all infants get between 13 and 16 hours of sleep every 24 hours.

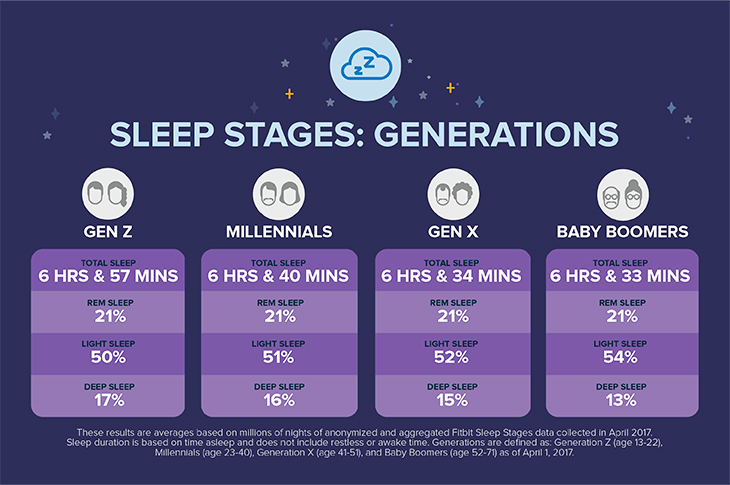

Overall, their sleep is light and restless. Unlike older children and adults, young babies usually lapse into REM, or rapid eye movement sleep, immediately after dozing off, and they spend a lot more sleep time in REM than we do.

Unlike older children and adults, young babies usually lapse into REM, or rapid eye movement sleep, immediately after dozing off, and they spend a lot more sleep time in REM than we do.

They move around a lot, and sometimes even vocalize. Learn more in my article about newborn baby sleep patterns.

3-4 months. Baby sleep patterns are becoming more adult-like. Infants no longer plunge directly into REM after falling asleep, and their sleep cycles begin to include longer stretches of slow-wave, “deep” sleep (Schechtman et al 1994).

In addition, babies are more likely to sleep for extended periods at night.

For example, in one study, approximately 50% of parents reported infant sleep bouts lasting 5 hours or more (Henderson et al 2010).

But multiple daytime naps are still common, and there is still a lot of individual variation. For most babies this age, total sleep duration is likely in the range of 12-16 hours.

5-6 months. Around this age, most parents report that their babies are sleeping without interruption at night for 5 hours or more, and many claim their babies sleep for more than 10 hours at night (Mindell et al 2016; Iglowstein; Jiang et al 2007).

Nevertheless, it’s not unusual for parents to report that their babies awaken at least once during the night, and some babies don’t settle into 5+ hour sleep bouts until they are considerably older (see below).

Babies typically take several naps during the day, and average total sleep duration remains in the range of 12-16 hours.

7-12 months. If your baby still isn’t sleeping for at least 5 hours at a stretch, you’re in good company. In one study of American infants, more than 15% of parents reported that their 12 month old babies hadn’t yet reached this milestone (Henderson et al 2010).

But for most families, nights have quieted down. It isn’t that these babies don’t experience night wakings. On the contrary, it’s normal for infants this age to awaken 3-4 times each night. But many babies have learned to fall back to sleep quietly on their own, so that their parents aren’t even aware that their infants had awakened (Goodlin-Jones et al 2001; Dias et al 2018).

By the end of the first year, babies tend to spend less time napping. But naps appear to remain helpful, and babies typically take one or two each day. Most babies continue to get sleep approximately 12-16 hours every 24 hours.

Factors that affect the timeline — or temporarily shake things up

Baby sleep patterns are shaped by a mix of genetic and environmental factors. For instance, in two studies of 6-month old babies, almost half the individual variation in nighttime sleep duration could be explained by genetic factors (Dionne et al 2015; Touchette et al 2013).

By contrast, individual differences in the trajectory of napping — whether babies decreased napping from 6 months onward — were almost entirely explained by environmental factors, like whether parents promote or discourage napping.

How do genes influence baby sleep patterns? One route is by shaping infant temperament. If your baby tends to be less adaptable and more irritable, it’s going to be harder to quiet him or her down, and studies confirm that such babies sleep less overall (Weissbluth and Liu 1983; Van Tassel 1985; Scher et al 1992; Sadeh et al 1994; Scher et al 1998).

It’s also likely that some babies need less sleep than others, and that specific aspects of sleep — like how easily an infant is awakened — are shaped by genes.

But it’s clear that parents can affect baby sleep patterns. We’ve already noted the effects parents have on napping. In addition, parents can influence the development of circadian rhythms, and help babies learn to resettle themselves after waking at night (see below).

Finally, it appears that baby sleep patterns vary from one country to the next. For example, studies suggest that babies in Japan and Italy tend to sleep less than their counterparts in Switzerland and Canada (Kohyama et al 2011; Bruni et al 2014; Iglostein et al 2003; Mindell et al 2010).

And motor milestones — like learning to crawl, learning to stand, and learning to walk — tend to disrupt baby sleep patterns (Atun-Einy Scher 2016; Scher and Cohen 2015). If your baby is mastering a new physical skill, you might observe temporary changes.

Digging deeper: What makes baby sleep patterns different from our own, and how can we help babies develop more mature sleep habits?

The foregoing summary offers some quick answers. But it pays to learn more about baby sleep patterns. It can help you avoid mistakes, and support the development of more mature sleep rhythms.

Here’s a look at baby sleep patterns in greater detail — focusing on circadian rhythms, sleep stages, sleep cycles, night wakings, and sleep duration.

Circadian rhythms: How long does it take for babies to synchronize with the natural, 24-hour day?

Young babies are notorious for sleeping and waking at awkward times. In part, this is because their circadian rhythms — recurring, 24-hour cycles of physiological activity — aren’t synchronized with the natural rhythms of daylight and darkness.

You may have heard that it takes 3-4 months for babies to develop mature circadian rhythms. But research confirms that the timing varies, and that babies synchronize sooner when we provide them with the right environmental cues.

Light has the biggest impact on your baby’s “inner clock,” so use it wisely.

During the day, expose your baby to natural, bright light. And as evening approaches, dim the artificial lights, and take care to avoid nighttime exposure to blue light, which is especially disruptive of sleep. Research suggests that newborns sleep for longer stretches at night when their parents stick with a policy of “lights out” after 9pm (Iwata et al 2017).

In addition, involve your baby in your daily activities, and avoid the temptation to turn nighttime feedings into social events.

When you attend to your baby in the middle of the night, be soothing, but avoid engaging your baby with eye contact and conversation. Keep the lights off, and your behavior low key.

Sleep stages and sleep cycles: How do baby sleep patterns unfold over the course of the night, and when are infants most likely to awaken?

To answer this, it helps to review what adult sleep is like.

For us, sleep isn’t a single continuous state of coma-like unconsciousness. We pass through a series of sleep stages, beginning with light sleep, progressing to deep sleep, and ending with rapid eye movement sleep, or REM — the sleep stage associated with busy brain activity, dreaming, and the loss of muscle tone.

We don’t move around during REM unless we suffer from certain sleep disorders.

The whole sequence takes approximately 90-100 minutes, after which we either awaken or repeat the cycle. Sleep lab research shows that we’re especially prone to awaken during or immediately after REM (Akerstedt et al 2002).

But throughout each sleep cycle, we also experience multiple arousals — brief, partial awakenings.

These are a normal part of sleep, fleeting “check ins” that help the brain keep tabs on potential threats. If there is nothing to attract our interest or concern, the arousal process is aborted, and the brain goes back to sleep.

For infants, things are much the same.

Babies experience distinct sleep stages, including an infant version of REM, called “active sleep.”

They also experience many brief arousals during the night, fleeting moments of drowsy wakefulness that you might not even notice.

And these arousals are especially common during the baby equivalent of REM, sometimes called “active sleep” (Grigg-Damberger et al 2007; Montemitro et al 2008).

But baby sleep patterns differ in crucial ways.

Baby sleep cycles are shorter — on average, about 50-60 minutes long (Jenni and Carskadon 2000; Jenni et al 2004; Grigg-Damberger 2017). And for the youngest babies — those under 3 months of age — the average sleep cycle looks like this:

- Active sleep (REM)

- Transitional sleep

- Quiet sleep

That is, babies begin a sleep bout in REM, next switch into a sleep stage called transitional sleep, and then finally arrive at a sleep stage called “quiet sleep” (Parslow et al 2003).

Another difference is that babies spend a lot more time in REM than we do.

Whereas average adult spends only 20% of total sleep time in REM, for newborns the percentage is higher than 50% (Grigg-Damberger 2017). Time spent in REM declines as babies get older, but the change my come slowly. For some 9-month-old babies, REM still makes up 50% of their total sleep hours (Montemitro et al 2008).

But perhaps the most consequential difference for new parents is that baby sleep patterns can deceive us. During REM and transitional sleep, babies can sometimes appear to be awake.

As noted, we adults don’t move around during REM. We experience sleep paralysis. But for young babies — especially babies under the age of 3 months — REM is a much more physically active state.

They twitch, wiggle, stretch, and thrash. They may frown or smile, or launch into a burst of sucking movements. They may vocalize too (Grigg-Damberger 2017; Barbeau and Weiss 2017).

So babies in REM may appear deceptively awake, and the same can be said for babies in transitional sleep. During transitional sleep, newborns become more likely to vocalize, and sometimes even open their eyes (Barbeau and Weiss 2017).

During transitional sleep, newborns become more likely to vocalize, and sometimes even open their eyes (Barbeau and Weiss 2017).

It’s really only during “quiet sleep” that young babies present us with reliable cues that they are asleep: Aside from the occasional sigh, their breathing becomes slow and regular, and they scarcely move at all. But young babies spend only a minority of their time in quiet sleep — approximately 20 minutes per sleep cycle (Grigg-Damberger 2017).

This can lead the exhausted parent to make an understandable but unfortunate mistake: You misread your baby’s cues, and end up disrupting your infant’s sleep.

It happens innocently enough.

You hear your baby whimper. You observe movement. You might even see that your baby’s eyes are open. So you bow to the inevitable, and swoop in to soothe him or her.

You start talking, or you pick your baby up.

It seems like a good idea at the time. Isn’t it better to be proactive, to jump in before your baby has become really noisy or agitated?

But your basic premise was faulty. Your baby wasn’t awake, but rather in REM or transitional sleep. Or perhaps what you mistook for waking was one of those brief arousals — a fleeting moment of drowsy wakefulness that would quickly transitioned back into sleep if you’d left your baby alone.

Your baby wasn’t awake, but rather in REM or transitional sleep. Or perhaps what you mistook for waking was one of those brief arousals — a fleeting moment of drowsy wakefulness that would quickly transitioned back into sleep if you’d left your baby alone.

Either way, you’ve intervened unnecessarily, and added a night waking to the schedule that might not otherwise have happened. And you may have denied your baby the experience of falling back to sleep on his or her own, without any fuss or distress.

If you make this mistake regularly, you may be teaching your baby to turn brief arousals into full-blown waking sessions — and to expect lots of interaction with you.

To avoid this, be patient and observant before responding to your baby at night.

Get to know your baby’s quirks. And be aware that your social cues — especially the sound of your voice — can have particular powerful effect. Babies can awaken quickly when they hear us talk.

In fact, researchers note that babies “arouse more easily in response to their mother’s voice than to a smoke alarm” (Grigg-Damberger et al 2007).

Why do babies spend so much time sleeping light?

It might seem like Mother Nature made a terrible mistake. Wouldn’t it be better if our babies slept soundly and deeply all night? But REM may be important for a baby’s brain development (Siegel 2005). According to one theory, it could be a time for the brain to test its wiring — including the nerves that run to the skeletal muscles.

In addition, it’s likely that active sleep — and a tendency to awaken easily — helps protect babies from oxygen deprivation.

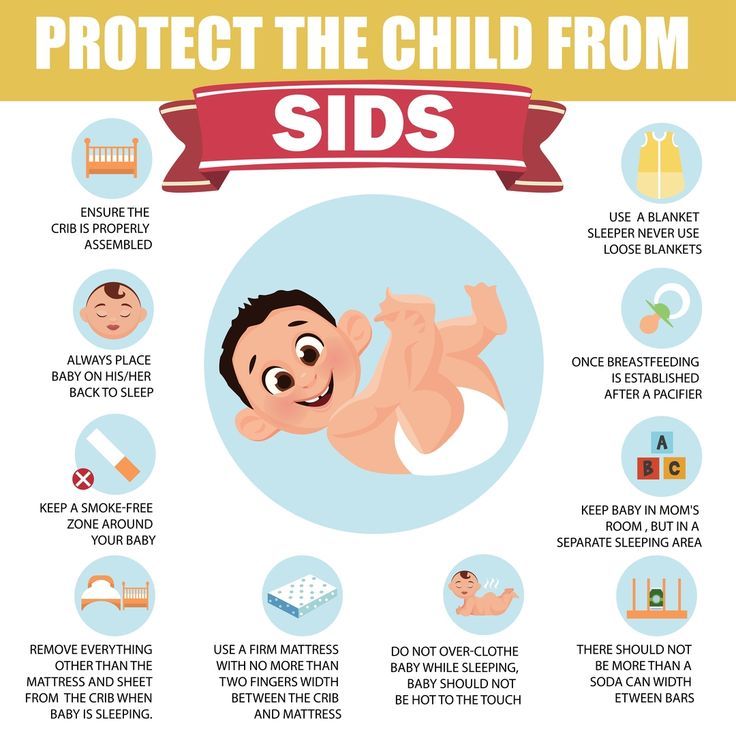

When a sleeping individual isn’t getting enough oxygen, it’s crucial to wake up immediately. Being slow to respond puts babies at higher risk for sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS.

So there is a crucial survival advantage to sleeping light, and that’s what REM sleep delivers.

Researchers have demonstrated this in experiments on sleeping infants. They subjected the babies to mild reductions in oxygen. Would the infants promptly awaken?

Babies did arouse quickly — if they had been in REM sleep. But if the oxygen levels dropped while babies were in quiet sleep, the outcome was different. Babies aroused more slowly, or failed to awaken altogether (Parslow et al 2003; Richardson et al 2007).

But if the oxygen levels dropped while babies were in quiet sleep, the outcome was different. Babies aroused more slowly, or failed to awaken altogether (Parslow et al 2003; Richardson et al 2007).

It appears, then, that long bouts of quiet sleep could be hazardous, at least for infants young enough to be at risk for SIDS. For the first 6 months, sleeping relatively light — and being easily aroused — is a good thing. It makes babies safer.

As a result, we must be thoughtful when we’re evaluating sleep advice. A given tactic isn’t automatically desirable because it results in babies sleeping more deeply or for longer stretches of time.

On the contrary, experts recommend some practices because they support more frequent arousals in young infants.

For example, babies who are breastfed tend to experience more frequent arousals than babies who are formula-fed. Researchers suspect this is one reason why breastfed infants have lower rates of SIDS (Horne et al 2004b; Franco et al 2000).

You can read more about environmental risk factors for SIDS — and sleep practices to avoid — here.

So how much sleep do babies need?

This is a surprisingly difficult question to answer, especially for younger babies.

We know what international surveys tell us about typical baby sleep patterns. Among parents with babies under the age of 3 months, approximately 50% say their infants sleep between 13-16 hours over the course of a 24 hour day (Iglowstein et al 2003; Bruni; Netsi et al 2017; Kohyama et al 2011).

This might suggest that 13-16 hours is what most young babies need. But the surveys have limitations.

First, they are based on parental reports, which can be inaccurate. When scientists measure sleep objectively, they find disparities between parental perceptions and reality. Parents tend to overestimate total sleep duration, and underestimate the frequency of night wakings (Goodlin-Jones et al 2001; Galland et al 2016).

Second, even if we could be certain about the numbers, the numbers wouldn’t constitute proof about what babies need. Maybe the babies in these surveys aren’t getting enough sleep. Or maybe they’re getting too much.

Maybe the babies in these surveys aren’t getting enough sleep. Or maybe they’re getting too much.

What’s needed is research that addresses the health consequences of sleep, and unfortunately such research is in short supply (Paruthi et al 2016).

Citing this lack of evidence, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine has declined to issue any specific recommendations about sleep duration for babies under the age of 4 months (Paruthi et al 2016).

For older babies (4-12 months), the Academy notes that some studies have found links between emotional or behavioral problems and short sleep. On this basis, the Academy advises that 4- to 12-month-old babies are at a lower risk for problems if they get between 12-16 hours of sleep every 24 hours (Paruthi et al 2016).

For more information, see my page about baby sleep requirements, as well as this Parenting Science sleep chart.

What about sleeping through the night? When do babies begin sleeping in long, uninterrupted nighttime bouts?

Understandably, parents want their babies to “sleep through the night. ” But, as we’ve already noted, nobody truly sleeps through the night — not in the sense of remaining in a constant sleep state for hours on end.

” But, as we’ve already noted, nobody truly sleeps through the night — not in the sense of remaining in a constant sleep state for hours on end.

Instead, what’s normal — both for babies and adults — is to experience many partial arousals throughout the night, and to occasionally wake up, if only very briefly.

Researchers have captured this in video recordings: Babies under the age of 12 months awaken, on average, 3-4 times a night (Goodlin-Jones et al 2001).

So it isn’t realistic to expect your baby to stop awakening at night. Nor would that be a good idea. As we’ve seen, arousals serve an important function.

Instead, a more reasonable goal is for your baby to settle down at night for at least 5 hours at a stretch. When your baby experiences an arousal, he or she quickly falls back to sleep — without your assistance.

That’s what’s really going on when parents say their babies sleep for long periods of time. The infants are experiencing normal arousals and night wakings, but their parents aren’t aware of these interruptions. Babies are staying quiet, and returning to sleep on their own.

Babies are staying quiet, and returning to sleep on their own.

So when does this happen? At what age do babies keep quiet for at least 5 hours? Between, say, midnight and 5am?

The answer is that it varies.

Some babies achieve this milestone at two months postpartum. But most babies don’t get there until 4-6 months, or even later.

We can see this pattern in a study that tracked 75 American infants over time. Jacqueline Henderson and her colleagues asked their parents to keep sleep diaries — 6 days per month — throughout the first 12 months postpartum.

Most parents didn’t record long stretches of sleep, not when their babies were very young. At two months, only 8% of parents reported that their babies were sleeping uninterrupted between the hours of midnight and 5am.

But by 4 months, approximately 50% of parents made this claim. And by 5-6 months, the majority of parents — about 70% — said their babies were sleeping without any perceived interruptions during these potentially crucial hours. At 12 months, the percentage had increased to 84% (Henderson et al 2010).

At 12 months, the percentage had increased to 84% (Henderson et al 2010).

But what if your baby isn’t a “good sleeper”? Is there something you can do to improve baby sleep patterns?

We’ve already seen that you can help your baby develop mature circadian rhythms.

If your baby isn’t sleeping well at night, make sure your baby is getting the right environmental cues — bright light during the day, darkness before bedtime, and a boring, peaceful nighttime atmosphere. This will help your baby get sleepy at the right time — and spend more time sleeping at night.

We’ve also seen that there are mistakes parents can make during the night — mistakes that can prevent babies from learning to fall back to sleep on their own.

If you can resist the urge to interact with a baby who seems to be waking — and wait to make sure the baby isn’t really asleep, or about to go back to sleep without your assistance — you’ll help your baby learn to sleep for longer periods.

In addition, you can troubleshoot for common sleep problems. Check out my overview of the causes of infant sleep problems, as well as my Parenting Science article about illnesses and physical ailments that can disrupt baby sleep patterns.

Check out my overview of the causes of infant sleep problems, as well as my Parenting Science article about illnesses and physical ailments that can disrupt baby sleep patterns.

And keep these tips in mind:

1. Remember that soothing, supportive, emotional communication is the key to getting babies settled.

Whether your baby shares a room with you, or sleeps elsewhere, you can make it a point reassure and calm your baby before bedtime. Being sensitive and responsive to your baby’s moods is called “emotional availability,” and studies show that it has an important impact on the way infants sleep. When parents show emotional availability at bedtime, babies wind down more easily, and they experience fewer sleep problems (Teti et al 2010; Jian and Teti 2015).

2. If you baby doesn’t seem to be sleepy at bedtime, don’t try to force it.

Getting pushy doesn’t make babies any sleepier. If anything, it makes them more excitable. And you don’t want your baby to associate bedtime with conflict. That can be a difficult lesson to unlearn!

That can be a difficult lesson to unlearn!

So instead, try the technique known as “positive routines and faded bedtime,” which you can read about here. It’s a method for resetting your infant’s inner clock, and overcoming bedtime resistance.

3. If your baby seems to cry inconsolably, or seems otherwise distressed, discuss this with your doctor.

It’s not clear if excessive, inconsolable crying disrupts baby sleep patterns, but it definitely stresses out parents. And when parents are stressed out, they suffer more sleep problems. Read more about inconsolable crying and its possible causes in this Parenting Science article.

4. Watch out for those late naps.

Naps are good for babies, but poorly-timed naps can cause trouble. A long snooze in the late afternoon can delay drowsiness for hours, wrecking havoc with your baby’s bedtime.

References: Baby sleep patterns

For a complete list of the studies and publications cited in this article, click here.

Written content last modified 4/2018; new image added 3/2022

image of father holding sleepy infant by monkeybusinessimages / istock

Small portions of the text appeared in an older article, “Baby sleep patterns: A guide for the science minded,” last published in 2014.

90,000 child does not go into a deep dream09/15/2015

82612

92

Mode of the child

Article

Tatyana Chkhikvishvili

Tatyana Chkhquishvili

Head of the Online Programs, Psychologist, Consultant for SNO and GV

Mom of two children

When does a child get deep sleep? What are the functions of deep sleep? How do you know if your baby is sleeping enough at this stage? Our article will tell about it.

Child's crises calendar

When a child develops deep sleep

Deep and very deep sleep in a child are the stages of non-REM sleep. These two stages are often referred to as delta sleep. In newborns, due to the immaturity of the brain, at first there is no slow sleep. So far, there is only its prototype - the so-called restful sleep. That is, the newborn does not have a stage of deep sleep. Brain maturation in children occurs at different times, at different speeds. On average, the slow-wave sleep phase, and as an integral part of it, the deep sleep stage, appears in infants at the age of 1-3 months. You can read more about this in our article Sleep Phases in Children.

In newborns, due to the immaturity of the brain, at first there is no slow sleep. So far, there is only its prototype - the so-called restful sleep. That is, the newborn does not have a stage of deep sleep. Brain maturation in children occurs at different times, at different speeds. On average, the slow-wave sleep phase, and as an integral part of it, the deep sleep stage, appears in infants at the age of 1-3 months. You can read more about this in our article Sleep Phases in Children.

Deep sleep - how to determine?

Babies sleep much better than adults. In this stage of sleep, children do not perceive sounds, light, touch, and temperature changes. As an experiment, children in the deep sleep stage were given a loud hissing sound through headphones. There were no signs of waking up or coming out of deep sleep, even if the sound volume reached 123 dB. This is an extremely loud sound, comparable in volume to the loudest human scream.

If you pick up the arm of a deep-sleeping baby and let it go, you will feel that it is completely relaxed, “like a rag”. When you let her go, she will fall helplessly, and the baby will not react to it in any way. At this stage of sleep, the baby can be transferred to another place, changed clothes, brought from frost to warmth, or vice versa - he will continue to sleep soundly. However, the deep sleep stage is not too long - about 20 minutes. After this time, the child will come out of deep sleep and, in case of discomfort, will respond to it by awakening.

When you let her go, she will fall helplessly, and the baby will not react to it in any way. At this stage of sleep, the baby can be transferred to another place, changed clothes, brought from frost to warmth, or vice versa - he will continue to sleep soundly. However, the deep sleep stage is not too long - about 20 minutes. After this time, the child will come out of deep sleep and, in case of discomfort, will respond to it by awakening.

Why deep sleep is needed

- Deep sleep is responsible for the body's physical rest, relieves accumulated fatigue, provides energy recovery, and "reboots" the body.

- Another important function of deep sleep is that it restores and "charges" the immune system, which is very important for the health of the baby.

- For full physical recovery and strengthening of the immune system, children need sufficient presence of the stage of deep sleep.

There is a misconception that it is normal for children to sleep exclusively on superficial sleep. This is partly true, because The sleep structure of newborns does not include a stage of deep sleep. But this is true only for very young children, in the first 1-3 months of life. After this age, it is very important for the child's body to have deep sleep.

This is partly true, because The sleep structure of newborns does not include a stage of deep sleep. But this is true only for very young children, in the first 1-3 months of life. After this age, it is very important for the child's body to have deep sleep.

When sleep is deepest

From approximately 19:00 to 1:00 am, the proportion of deep sleep in a person's sleep pattern is highest. In the second half of the night, deep sleep is almost absent. Sleep becomes superficial and fast. Man, like all living things on earth, obeys nature, his circadian rhythms dictate their own laws.

If a child (and an adult too) sleeps too little in the first half of the night, he or she will not get this important deep sleep. This shortage cannot be fully compensated for by longer sleep in the morning, since sleep in the first and second half of the night is different in structure and function. Therefore, it is very important to ensure that the child goes to bed early at night.

Does the child get enough deep sleep?

The main criterion for a sufficient amount of deep sleep is the well-being and behavior of the child. If a child wakes up well rested, joyful and cheerful, and maintains this mood throughout the day, falling asleep without tears, most likely, he sleeps quite enough.

What affects deep sleep

In addition to the physiologically determined limitation of the time of deep sleep, the control of emotional load has an important influence on the representation of the stage of deep sleep in the overall structure of sleep. If a child has an excess of impressions, emotions, experiences, this has a tremendous impact on his brain. As a protective measure, the proportion of fast, REM sleep, which is responsible for processing information, restoring the nervous system, and relieving psycho-emotional stress, increases. This is due to a decrease in the proportion of deep sleep. As a result, with a seemingly sufficient duration of sleep, the child does not receive the physical recovery he needs, wakes up insufficiently rested, quickly gets tired and accumulates fatigue.

Therefore, it is important that the child receives sufficient physical activity for a long sleep, but not excessive emotional activity. You should limit visits to crowded, noisy places and intensive communication with new people, especially in the evening. Also, watching TV, cartoons, interacting with various gadgets and interactive toys has a great load on the nervous system of children. It is recommended to minimize this exposure during the day and avoid it completely during the time before sleep.

#phasesleep

', nextArrow: '', responsive: [{breakpoint: 1199, settings: {arrows: !1, infinite: !1, slidesToShow: 1}}] }) })Elena Muradova

Founder of BabySleep, first sleep consultant in Russia and CIS

Sleep phases | REM and deep phases of sleep in newborns

09/15/2015

151313

185

Child mode

Author of the article

Tatiana Chkhikvishvili 903

0002 Head of online programs, psychologist, consultant on sleep and breastfeedingMother of two children

Newborn sleep and sleep phases in children during the first months of life differ from adult sleep. What are the phases of a baby's sleep, when there is a transition to an adult sleep model, what happens after a change in the sleep pattern - this article tells.

What are the phases of a baby's sleep, when there is a transition to an adult sleep model, what happens after a change in the sleep pattern - this article tells.

0–4 months. Improve sleep in 3 weeks

Sleep before birth

Unborn babies spend most of their time sleeping. It is even possible that they are dreaming. Unfortunately, scientists do not have accurate information about exactly how babies sleep in their mother's stomach.

The first days of life

Immediately after birth, babies continue to sleep a lot, spending almost all the time sleeping. In newborns, sleep is divided into two phases:

- active sleep;

- restful sleep.

Active sleep already in the first days after birth is transformed into REM sleep, similar to the phase of REM sleep in adults. REM sleep is also called the REM stage - from the English "Rapid Eye Movement", which means "sleep with rapid eye movements. "

"

REM sleep

In adults, REM sleep accounts for 15–25% of sleep, while in infants, REM sleep is about 40–50%. This is necessary for the growth and development of the child's brain - it is in the phase of REM sleep that dreams give the brain visual images, training the brain and stimulating its growth.

REM sleep provides the function of psychological protection, relieves psycho-emotional stress, filters information, reboots the brain, and ensures brain growth.

The proportion of REM sleep decreases as the child grows:

Gradual maturation - 1-3 months

Another form of baby sleep is restful sleep, which later transforms into non-REM sleep, similar to adult sleep. Brain maturation takes place in different ways, all children have their own, individual speed. Non-REM sleep requires higher brain maturity, which is why it occurs later than REM sleep. This happens on average in 1-3 months.

Non-REM sleep consists of the following stages:

- Entering sleep

- Superficial sleep

- Deep sleep

Deep sleep

Deep sleep in babies is much better than in adults. Children practically do not react to sounds, light, touch and temperature. This stage of sleep in young children lasts about 20 minutes. Deep sleep is responsible for restoring energy. It "reboots" the body, relieves accumulated fatigue, gives physical rest, restores and "charges" the immune system.

In order to fully recover physically and strengthen the immune system, children need a sufficient presence of the stage of deep sleep - contrary to a fairly common misconception that children up to almost a year old should sleep exclusively on superficial sleep.

Falling asleep after 4 months

Now, when falling asleep, babies “walk the steps of sleep”, successively passing through all stages of sleep.

Sleep stages of the child after 3-4 months:

- sleep entry;

- superficial sleep;

- deep dream;

- fast sleep.

That is why if you try to shift a grown-up child who has just fallen asleep, he will most likely wake up immediately - his dream was superficial.

40-minute naps

Sleep phases make up a child's sleep cycle. After 3-4 months, it is similar to the adult sleep cycle, but has a much shorter duration - about 40 minutes.

A baby's 40-minute sleep cycle often ends with the baby waking up. This is necessary to monitor and assess its condition. Is everything in order, is it not hot, not cold, is the baby hungry?

If everything is in order, the baby immediately falls asleep again, and often parents do not even notice this micro-awakening. If something is wrong, the baby declares his needs.

Such awakenings between sleep cycles occur every night in adults.