What is the belly button connected to

What's really going on behind your belly button

Story highlights

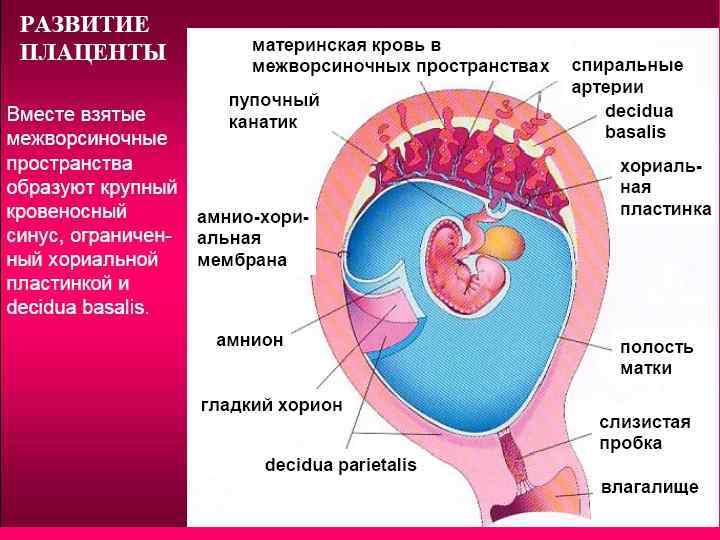

The umbilical cord is made up of one large vein and two smaller arteries

After birth, the veins and arteries in the cord close up and form ligaments

Our belly button is a reminder for life that once we were attached to and dependent on our mother, floating like a little astronaut in our liquid universe.

The cord, and in particular the remaining belly button, has always been fascinating to humans and we still embark on some interesting traditions to celebrate and aid the physical separation of the umbilical cord.

The umbilical cord is probably the baby’s first toy, as they are sometimes caught on ultrasound playing around with it.

Cutting the cord at birth is one of the most common surgical procedures in the word today and at some point almost every human on earth has undergone this.

Recent scientific evidence has made us rethink how soon this should occur after birth, with evidence the baby can receive as much as another 80-100ml (almost a third of its total blood volume) if we just delay clamping and cutting the cord for three or more minutes after the birth.

Not only do babies get more blood this way but this extra blood volume has a positive impact on child development.

Shutterstock

Wait to cut umbilical cord, experts urge

The umbilical cord forms very early on in pregnancy and basically gets longer due to the increasing baby movements until it reaches around 50-70cm. And babies who move a lot tend to have longer cords.

I’ve always wondered: Why is the sea salty?

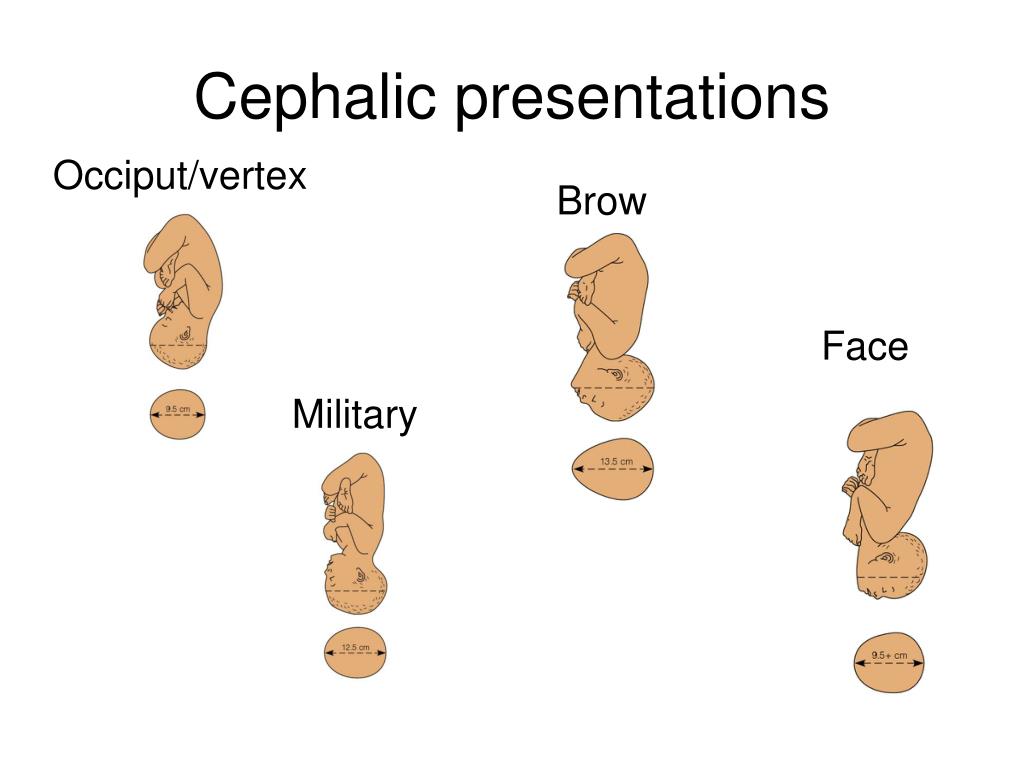

The umbilical cord is made up of one large vein and two smaller arteries. The vein carries the oxygen-filled blood from the mother to the baby. The arteries carry the oxygen-depleted blood and waste products from the baby back to the mother. The cord inserts into the placenta so it’s not directly connected to the mother’s circulation.

A cross-section of an umbilical cord

MriMan/Shutterstock/Shutterstock / MriMan The placenta acts like a very sophisticated filtering system. In order to protect the blood vessels from compression while the baby moves about, or when it is being born, the cord is filled with a jellylike substance called Wharton’s jelly. Think of it as nature’s airbags. This is why most of the time when the cord is around a baby’s neck at birth (a common event) it’s not a problem.

Think of it as nature’s airbags. This is why most of the time when the cord is around a baby’s neck at birth (a common event) it’s not a problem.

At some point after the birth the cord ceases its important function of taking blood back and forth between the mother and baby. Once cut and clamped it withers away into a firm black stump over the first week of life before falling off and leaving that much adored belly button.

Blood extracted from cord blood at University College London Hospital (UCLH) in March 2017.

Mosaic/ WellcomeThe life-saving treatment that's being thrown in the trash

You may have discussed with friends whether you have an “inny” or an “outty” and during pregnancy women often marvel at the exposure and flattening of their own belly button as their uterus expands with the growing baby.

People joke about belly button fluff and some decorate this part of their body with piercings and jewels. But is more going on beneath this shriveled reminder of our beginning on this earth?

I’ve always wondered: Why is the flu virus so much worse than the common cold virus?

After the baby is born and takes that first breath, blood is shunted to the lungs, which have been reasonably quiet up to that point as they have been filled with fluid. An amazing switch happens in the circulation with the two arteries constricting to stop the flow of blood to the placenta and then the vein slowly collapsing.

An amazing switch happens in the circulation with the two arteries constricting to stop the flow of blood to the placenta and then the vein slowly collapsing.

Internally the veins and arteries in the cord close up and form ligaments, which are tough connective tissues. These ligaments divide up the liver into sections and remain attached to the inside of the belly button.

The part of the umbilical arteries closest to the belly button degenerates into ligaments that serve no real purpose but the more internal part becomes part of the circulatory system and is found in the pelvis supplying blood to parts of the bladder, ureters and ductus deferens (a tube sperm moves through in males).

Why we love to be scared

Rarely a canal remains that connects the bladder to the belly button. This leads to urine leaking out of the belly button and this is an abnormality that would need to be surgically repaired following birth.

Join the conversation

Ever noticed that when you stick a finger in your belly button you can feel tingling around your bladder and pelvic area? Now you know why. What was once a highway of blood from mother to baby turns into ligaments and some continued connection to blood supply deep inside your body.

What was once a highway of blood from mother to baby turns into ligaments and some continued connection to blood supply deep inside your body.

So next time someone tells you not to navel gaze you will have a smart come back about just how amazing the navel really is.

Hannah Dahlen is a professor of midwifery at Western Sydney University.

Republished under a Creative Commons license from The Conversation.

Your Belly Button: Things You Didn't Know About Your Navel

When was the last time you gazed at your navel? The belly button deserves more attention thanks to all the secrets it's hiding.

Oksana Kuzmina/Shutterstock

Your belly button marks where the umbilical cord used to be

The belly button marks the area where the umbilical cord used to be attached, says Christopher S. Baird, PhD, assistant professor of physics at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, TX.

Baird, PhD, assistant professor of physics at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, TX.

When a baby is in the womb, the umbilical cord attaches to the navel at one end and your placenta—an organ that develops during pregnancy that’s attached to the uterus—at the other. The umbilical cord transports nutrients from the mother to the baby.

Once a baby is born, the umbilical cord becomes useless. The body responds to the transition by closing up the point where the umbilical cord connected to the body. The result: A belly button. Check out the surprising purpose of 8 weird body parts.

andy_coleman83/Shutterstock

Not all mammals have a belly button

You would expect all mammals to have a belly button, but there are some exceptions. One of note: Marsupials (like kangaroos and wombats). When it comes to marsupials, the fetus is incubated for much less time, so their need for in-utero nutrition is less. After birth, they crawl up to mom’s pouch and latch on to a nipple, and do the rest of their fetal development there. Yes, your dog or cat has one—you just may not have noticed them because they’re usually smooth or flat and covered by fur.

After birth, they crawl up to mom’s pouch and latch on to a nipple, and do the rest of their fetal development there. Yes, your dog or cat has one—you just may not have noticed them because they’re usually smooth or flat and covered by fur.

Jerome Scholler/Shutterstock

Most are “innies”

While most belly buttons begin as outies, the majority fold in during the healing process to form innies, with only 10 percent of people holding onto their outies through adulthood. That said, if you’re unhappy with yours, chances of it naturally switching are slim to none as an adult. Here are some strange facts about the things you’ve always wondered about your body.

Billion Photos/Shutterstock

It’s teeming with bacteria

Despite its proximity to you, the belly button goes largely ignored, unless you adorn it with body jewelry or are fond of midriffs. But it’s actually one of several body parts that accumulate weird gunk. A 2012 study in the journal PLOS One found that there are at least 67 groups of bacteria organisms found in each belly button, with six different types making up the majority in more than 80 percent of people.

But it’s actually one of several body parts that accumulate weird gunk. A 2012 study in the journal PLOS One found that there are at least 67 groups of bacteria organisms found in each belly button, with six different types making up the majority in more than 80 percent of people.

nimon/Shutterstock

Belly button plastic surgery is a big deal

Not everyone is keen on their belly button, which is why belly button plastic surgery is kind of a big deal. (The procedure is called an umbilicoplasty.) It turns out that we have a general preference for navel aesthetics. In one study in 2017 in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, an oval-shaped belly button was deemed the most attractive. Make sure you know the scientific explanations behind 25 quirky body reactions.

Beatriz Vera/Shutterstock

It’s controversial

Despite the growing Western trend of belly button exposure, it hasn’t always been that way, and, in some cultures, it’s still considered taboo. In Western culture, the belly button was considered indecent in the past—that’s why Barbara Eden in I Dream of Jeannie covered up hers. Cher was the first to expose her belly button on TV in 1975, according to a story in The Atlantic.

In Western culture, the belly button was considered indecent in the past—that’s why Barbara Eden in I Dream of Jeannie covered up hers. Cher was the first to expose her belly button on TV in 1975, according to a story in The Atlantic.

chaowalit jaiyen/Shutterstock

People take their cues about you based on your belly buttonThe science of attraction is real, and it extends to navel-gazing. According to a paper in The FASEB Journal, people prefer navels that are T-shaped or oval, and vertical with a little hooding. While outies are considered unattractive, it may come of surprise that innies that are too deep are also given the cold shoulder. The author also says that a woman’s navel is used to determine her reproductive potential as well, though whether or not that assessment is true remains to be seen. These are the biggest unsolved mysteries about the human body.

Bokeh Blur Background/Shutterstock

Belly button lint is pretty gross

Certainly not the most enjoyable part of the belly button, lint is made up of stray fibers from clothing or a towel (thanks to drying off post-shower), along with dead skin cells and body hair. According to a 2018 paper in Scientific Reports, abdominal hair directs the lint into this reservoir throughout the day. Pretty cool! Check out these other explanations for gross substances on your body.

shmel/Shutterstock

Pregnancy changes innies to outies

While people born with outies can experience a shift to an innie early in childhood, there’s one instance where the general rule of thumb goes the opposite direction. The expanding abdomen of pregnancy can pop some innie belly buttons out during the second or third trimester, reports the Cleveland Clinic. After delivery, mothers can likely expect their belly button to return to its typical shape.

Maridav/Shutterstock

The belly button is an erogenous zone

Media has done a great job of hyping up this body part as sexually explicit, but the navel’s heightened sensitivity may also attribute to its status as sensual. “Simply viewing the belly button area can be a sexual trigger, psychologist Leon F. Seltzer, PhD, writes in Psychology Today. “From heterosexual man’s point of view, seeing the exposed navel and surrounding area can be very attractive. It accentuates a woman’s waistline, her curves and brings out the beauty and fertility of a woman’s body.” Here are 20 obscure facts you never knew about your own body.

Sources

- Christopher S. Baird, PhD, assistant professor of physics at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, TX.

- American Pregnancy Association: “Umbilical Cord Care.”

- University College London: “Question of the Week: Do All Animals Have Belly Buttons?”

- University of California Museum of Paleontology: “Marsupial Mammals.

”

” - American Museum of Natural History: “Microbiome Monday: The Ecosystem In Your Belly Button.”

- PLOS One: “A Jungle in There: Bacteria in Belly Buttons are Highly Diverse, But Predictable.”

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: “Prospective, Double-Blind Evaluation of Umbilicoplasty Technique Using Conventional and Crowdsourcing Methods.”

- The Atlantic: Taylor Swift and the Fraught History of Navel-Gazing.”

- The FASEB Journal: “Umbilicus as a Fitness Signal in Humans.”

- Cleveland Clinic: “Why Do Some Women’s Belly Buttons Pop Out During Pregnancy?”

- Scientific Reports: “Modeling the Production of Belly Button Lint.”

- Psychology Today: “What’s So Sexy About Belly Buttons?”

Originally Published: October 04, 2019

Alexa Erickson

Alexa Erickson is a lifestyle and news writer currently working with Reader's Digest, SHAPE Magazine, and various other publications. She loves writing about science news, health, wellness, food and drink, beauty, fashion, home decor, and her travels. Visit her site Living by Lex.

She loves writing about science news, health, wellness, food and drink, beauty, fashion, home decor, and her travels. Visit her site Living by Lex.

What happens to the navel when growing up - SakhaLife

08/28/2018

13:30

31395

Beauty & Health

All mammals are born attached to their mother by the umbilical cord. After this connection is broken, the navel is tightened and becomes invisible, and only in people it remains for the rest of their lives, Rambler reports. What happens to this part of the body when a person grows up?

During the first hours of life

As you know, after birth, on their own or with the help of a midwife, the child takes the first breath, and the blood through his veins passes to the lungs, which previously did not perform their functions. The alveoli open up, the arteries constrict, and the flow of blood to the placenta stops, the umbilical cord vein slowly withers. Now obstetricians cut this connecting element of the baby and mother.

Now obstetricians cut this connecting element of the baby and mother.

Neonatologists from the Northern State Medical University, Russia explain in the Neonatology Practice Guide that at this point, the internal veins and arteries in the umbilical cord close and form ligaments, which are tough connective tissue. These ligaments remain attached to the inside of the navel. Some of the remaining umbilical arteries become part of the circulatory system and supply blood to the bladder, ureters, and vas deferens in male infants.

Domestic doctors also warn that sometimes babies have a vessel that previously connected the bladder to the umbilical cord. In this case, urine is periodically released from the navel of the child, and then this pathology is operated on as planned.

In childhood

In most cases, umbilical hernia occurs in children at an early age - up to 5 years. Representatives of the American Academy of Pediatrics, in a memo for young colleagues, explain that normally, after the umbilical cord falls off in newborns, the umbilical ring closes and the hole is obliterated by scar connective tissue.

But if the navel node is swollen, redness is noticeable on the skin, this means that the increase in intra-abdominal pressure has contributed to the release of intestinal loops, the greater omentum and peritoneum into the paraumbilical space. The occurrence of intra-abdominal pressure can have a variety of reasons, ranging from the development of constipation in a child to Harler's disease. But the enlarged and inflamed navel takes on a normal appearance and minimal boundaries after surgical treatment. It is called hernioplasty and is performed using local tissue or mesh implants.

It should be noted that the formation of an umbilical hernia in a child is in no way connected with the technique of processing the umbilical cord at the time of birth.

In later life

Throughout adult life, a person rarely pays attention to his navel. He usually remembers this part of the body when intestinal or stomach pain radiates into it.

Another option is to carry out ordinary hygiene procedures, as a result of which obvious dirt is suddenly washed out of the umbilical fossa. Even people who take a shower every day have encountered this phenomenon, and this has interested scientists. A group of epidemiologists from North Carolina State University at Chapel Hill, USA, studied the navel for a whole year. To do this, they invited 60 volunteers - men and women aged 30 to 60 years, of average income, who observe daily standard water procedures. From each of them swabs were taken from the navel, which were then subjected to biochemical and genetic analysis.

Even people who take a shower every day have encountered this phenomenon, and this has interested scientists. A group of epidemiologists from North Carolina State University at Chapel Hill, USA, studied the navel for a whole year. To do this, they invited 60 volunteers - men and women aged 30 to 60 years, of average income, who observe daily standard water procedures. From each of them swabs were taken from the navel, which were then subjected to biochemical and genetic analysis.

Based on the results of the study, scientists concluded that about 2368 different bacteria live in the umbilical pits of volunteers. Moreover, more than 1,500 species of them are microorganisms unfamiliar to science, usually not found on the human body. But how is this possible? And why didn't these microbes cause any disease in humans?

American epidemiologists have made the assumption that over the course of life, under the influence of the environment and taking into account the fact that human clothing covers the umbilical pits, bacteria collect and even multiply in them in all people. Since a person maintains a connection between the navel, stomach and intestines, these microorganisms do not fully, but exert their influence on these organs. However, it does not harm the body, but on the contrary, it “accustoms” the gastrointestinal tract to its toxins, improving its performance and increasing overall immunity. That is, a person's navel is one of the involuntary guardians of his health.

Since a person maintains a connection between the navel, stomach and intestines, these microorganisms do not fully, but exert their influence on these organs. However, it does not harm the body, but on the contrary, it “accustoms” the gastrointestinal tract to its toxins, improving its performance and increasing overall immunity. That is, a person's navel is one of the involuntary guardians of his health.

Source: https://doctor.rambler.ru/news/40660233-chto-proishodit-s-pupkom-pri-vzroslenii

#health#navel

If you saw an interesting event, send photos and videos to our Whatsapp

+7 (999) 174-67-82

If you notice a typo in the text, just select this fragment and press Ctrl + Enter to inform the editor about it. Thank you!

Top

The wonderful world of the navel: where does the wool come from?

- Jason Goldman

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Image copyright, Getty

Image caption,Perhaps the formation of umbilical pellets helps to cleanse the navel of bacteria

Why do some people have a clean navel during the day, while others have to extract a fluffy lump from it every evening? The correspondent was looking for the answer to this question BBC Future .

Here's what you need to know about navel balls - hairballs that form in the navel: they are most common in middle-aged hairy men, especially those who have recently put on weight.

Dr. Carl Krushelnicki of the University of Sydney came to this conclusion. Dr. Carl, as his fans call him, hosts a science radio show. One of the listeners once asked him a question where the umbilical pellets come from. Krushelnicki thought about it and decided to conduct an Internet study, according to the results of which he concluded that umbilical hair occurs mainly in middle-aged men with a lot of body hair. For this research, in 2002, he was awarded the Ig Nobel Prize, awarded "for achievements that make you first laugh, and then think."

For this research, in 2002, he was awarded the Ig Nobel Prize, awarded "for achievements that make you first laugh, and then think."

In addition to the online study, Krushelnytsky and a group of colleagues collected umbilical hair samples from volunteers and asked them to wash the hair around the navel. It turned out that water procedures really prevent the formation of spools.

(More BBC Future articles in Russian)

Dr. Carl and colleagues may not be the world's leading experts in the field, but their explanation for umbilical hair formation is at least intuitive. The hair around the navel, in their opinion, plays the role of a one-way ratchet - it picks up the smallest fibers of fabric from the inside of the clothes and moves them to the navel.

The older the clothes, the less pilling

Krushelnicki is not the only one interested in the mechanism of navel hair. In 2009, researcher Georg Steinhauser of the Technical University of Vienna wrote an article on the same topic in the journal Medical Hypotheses. For reasons known only to himself, Steinhauser collected his own umbilical pellets every evening for three years. Although, according to his assurances, he is quite clean and takes a shower every day, at the end of the day, a ball of wool invariably forms in Steinhauser's navel.

For reasons known only to himself, Steinhauser collected his own umbilical pellets every evening for three years. Although, according to his assurances, he is quite clean and takes a shower every day, at the end of the day, a ball of wool invariably forms in Steinhauser's navel.

Altogether, Steinhauser collected 503 of these pellets weighing less than a gram. On average, each lump weighed 1.82 mg, although seven samples exceeded the weight of 7.2 mg, and the winner was the 9.17-milligram giant.

Image copyright, Getty

Photo caption,The color of the umbilical coat usually matches the predominant color of the hairs that make up the fur

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of Story Podcast

"The spools were obviously cotton lint, since they were the same color as the clothes I wore on any particular day," Steinhauser wrote. Moreover, the size of the pellets was smaller when wearing suit shirts, as well as old T-shirts - in the latter case, this is probably due to the fact that there were already very few villi left on the fabric.

Steinhauser came to the same conclusion as Krushelnicki: the hair growing around the navel is responsible for the formation of the pellets. He suggested that it was the hairs that collected the villi from the clothes, and then sent them to the navel. "Hair scales act like fishhooks," the researcher wrote.

When Steinhauser shaved the hair around the navel, he found that, as in the case of Dr. Carl's volunteers, it was enough to stop the process of navel hair formation.

But Steinhauser went even further. He analyzed the chemical composition of the pellet that formed in his navel after wearing a white 100% cotton T-shirt. If the sample consisted entirely of lint from a T-shirt, the analysis would show only cellulose in the pellet. However, the researcher found the presence of other particles - dust, skin flakes, fat and protein cells, as well as sweat.

He analyzed the chemical composition of the pellet that formed in his navel after wearing a white 100% cotton T-shirt. If the sample consisted entirely of lint from a T-shirt, the analysis would show only cellulose in the pellet. However, the researcher found the presence of other particles - dust, skin flakes, fat and protein cells, as well as sweat.

Apparently the belly hairs don't care what to pick up. Based on these results, Steinhauser concluded that those of us who "produce" navel hair should have cleaner navels in general, since other types of pollution are also eliminated in the process of removing the pellets.

Although not all scientists devote their time and energy to the study of the causes of the formation of umbilical pellets (perhaps Krushelnicki and Steinhauser are generally the only researchers who are interested in this topic), a serious study is now being carried out at the University of North Carolina to understand what else can be found in the human navel.

Department of Biology Fellow Rob Dunn established the Belly Button Diversity Project with the university's Center for Behavioral Biology. In 2011, Dunn and colleagues collected navel hair samples from more than 500 volunteers attending the Science Online conference in Raleigh, North Carolina, and the Darwin Day event at the city's natural science museum. The researchers were not interested in villi - they wanted to study the microflora of the navel. "The navel is one of the closest habitats to us, but it remains relatively little known," the scientists said.

Since that very first study (and the researchers have collected more samples since), Dunn's team has uncovered an astonishing microbiological diversity of the navel - a veritable treasure trove of microscopic life forms.

Adaptation to life in the navel

In the first batch of 60 samples, scientists found at least 2368 species of microorganisms. They suspect that the real figure is likely to be even higher. But the number of bacteria found is more than twice the diversity of bird or ant species that inhabit North America.

They suspect that the real figure is likely to be even higher. But the number of bacteria found is more than twice the diversity of bird or ant species that inhabit North America.

However, most of the species found are rare, with 2128 found in the navels of five or fewer test subjects. In fact, the largest number of bacterial species was present in the navel of a single volunteer.

Photo copyright, Getty

Photo caption,Umbilical pellets also form in those who shower every day. Although the researchers were unable to detect a single bacterial species that was typical of the umbilical flora of all subjects, eight species were found in the navels of at least 70% of the volunteers. The total number of organisms of these species accounted for almost half of the total number of all bacteria found.

The researchers also found three species of archaea, bacteria commonly found in extreme environments. Interestingly, two of the three species were found in the navel of the same volunteer, who admitted he hadn't showered in years.

Where did such a variety of umbilical flora come from? Dunn's team suspects that eight of the most typical species of bacteria have adapted to life on human skin - or perhaps in the navel itself - while other species only occasionally visit the distant navel shores.

Scientists draw an analogy with the diversity of fish species at the mouth of a river. Permanent residents have adapted to this environment, while other species that can swim in the river for a short time are not adapted to long-term survival in local conditions. Similarly, a disproportionate number of trees of certain species in rainforests adapt to the local climate. Other species, although able to grow in tropical soil, are not able to form colonies.

While the diversity of microorganisms makes it impossible to predict which types of bacteria can be found in an individual's navel, researchers are able to suggest which types are most common.

So, even if your navel does not form pellets, you should not be sad - it is still a very densely populated area, life is in full swing there.