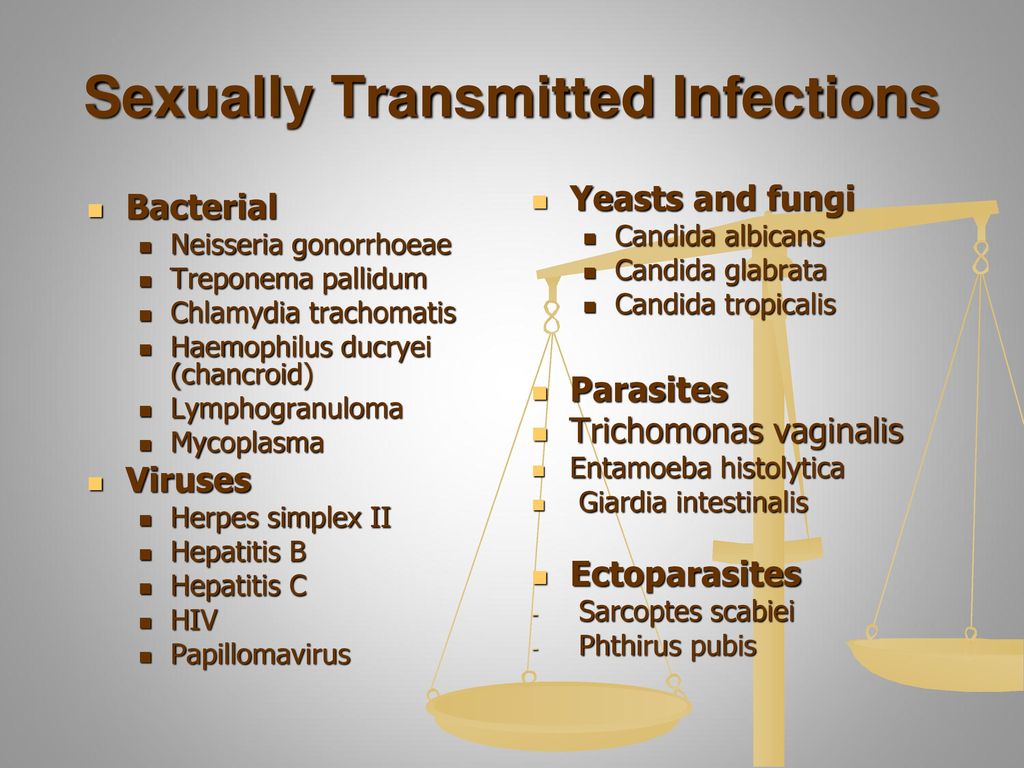

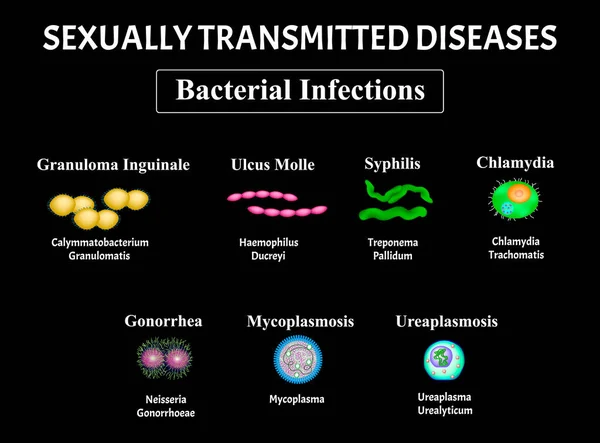

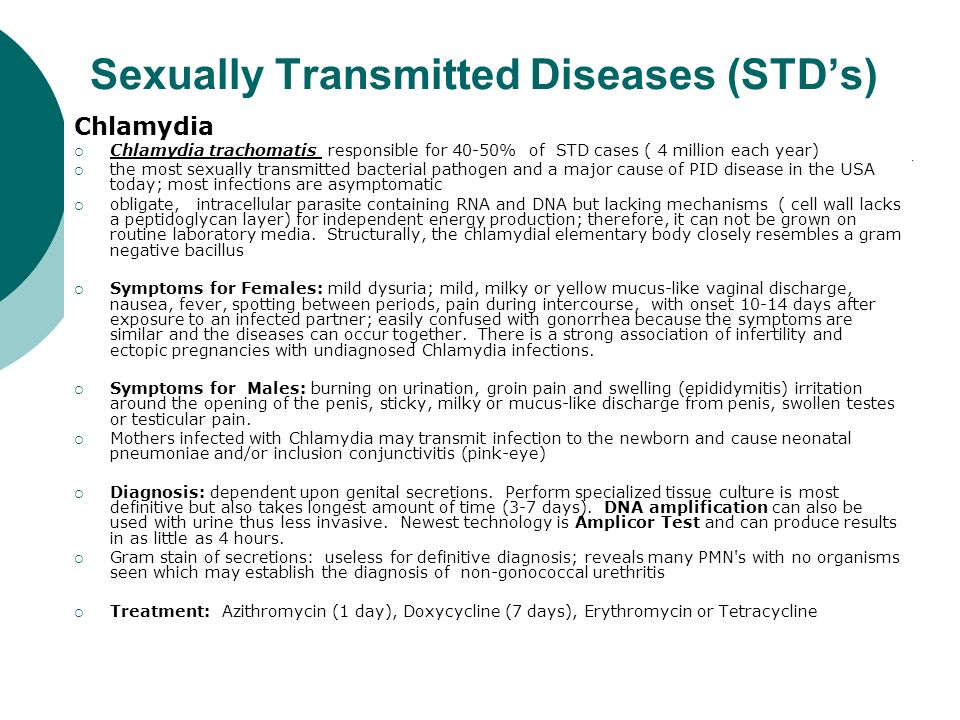

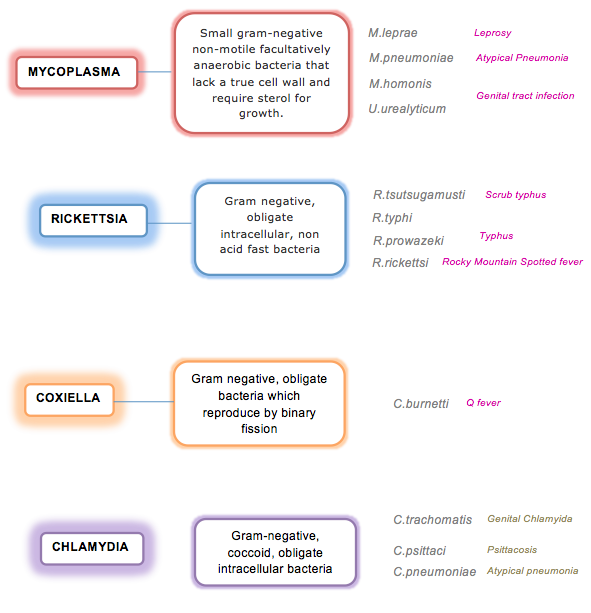

What is the bacteria that causes chlamydia

Detailed STD Facts - Chlamydia

What is chlamydia?

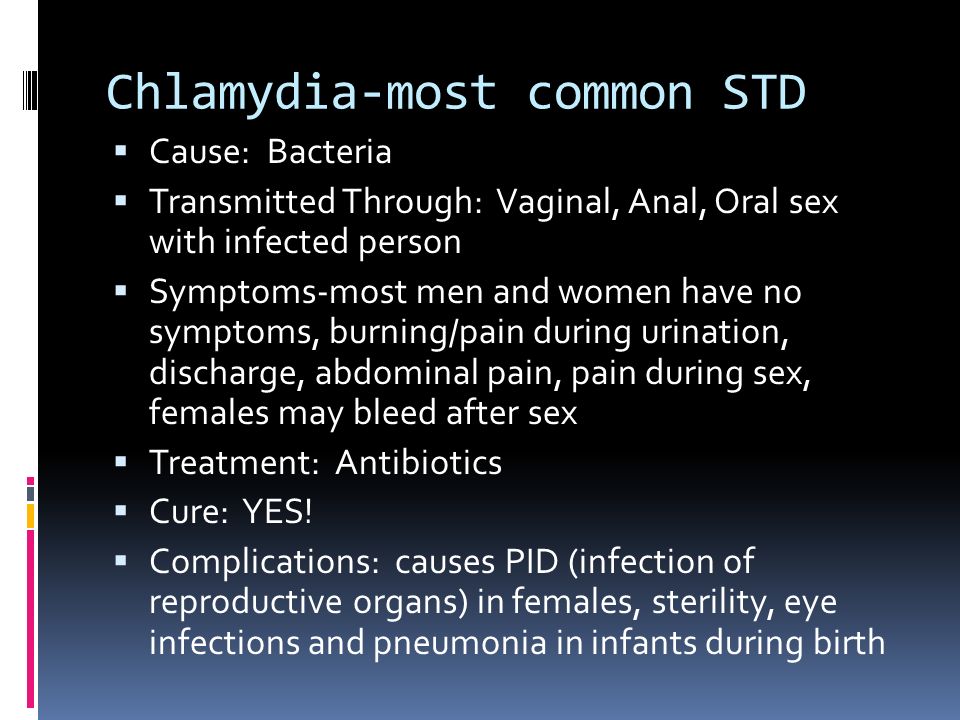

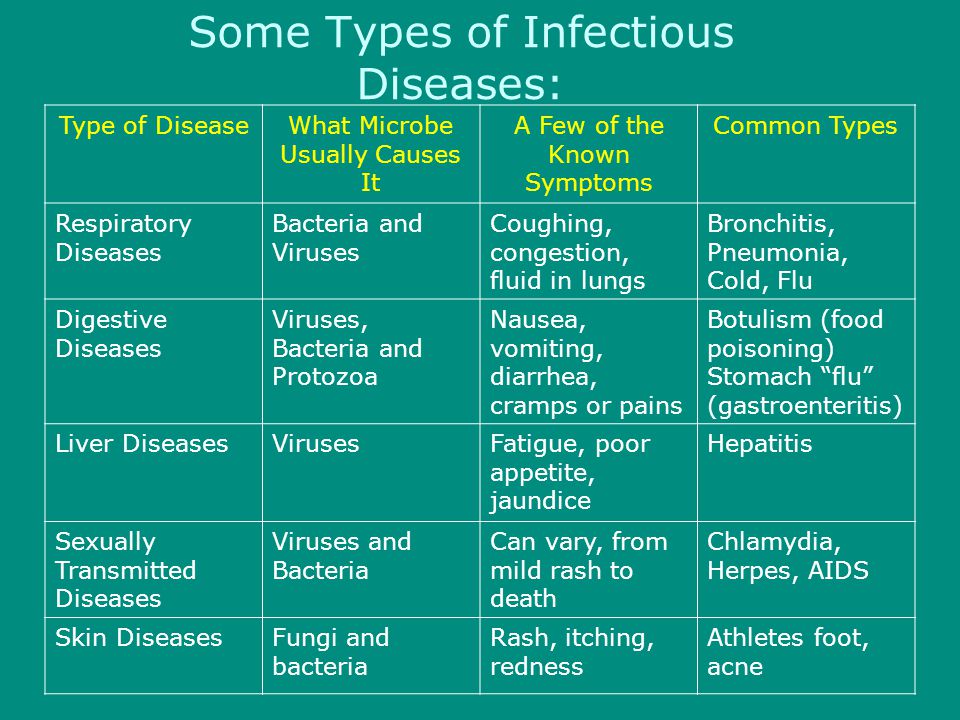

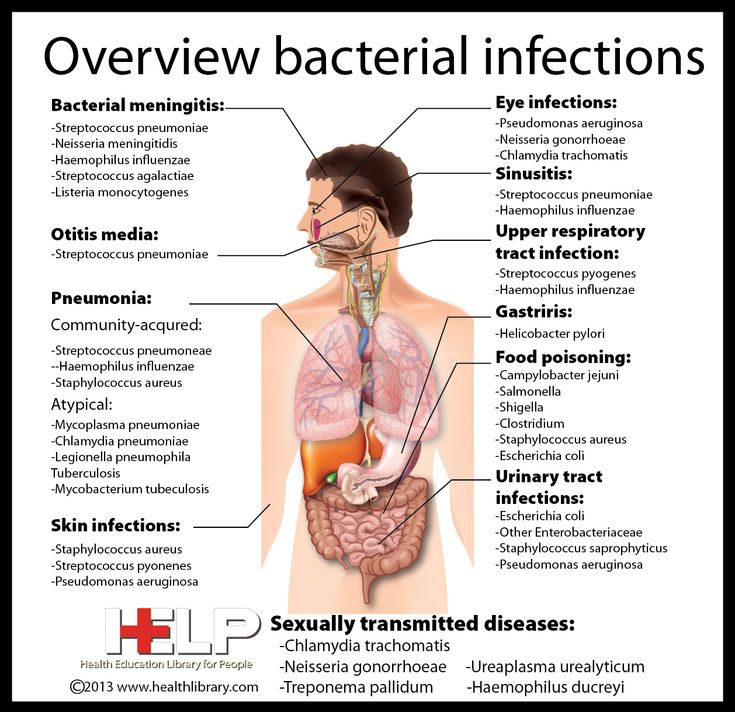

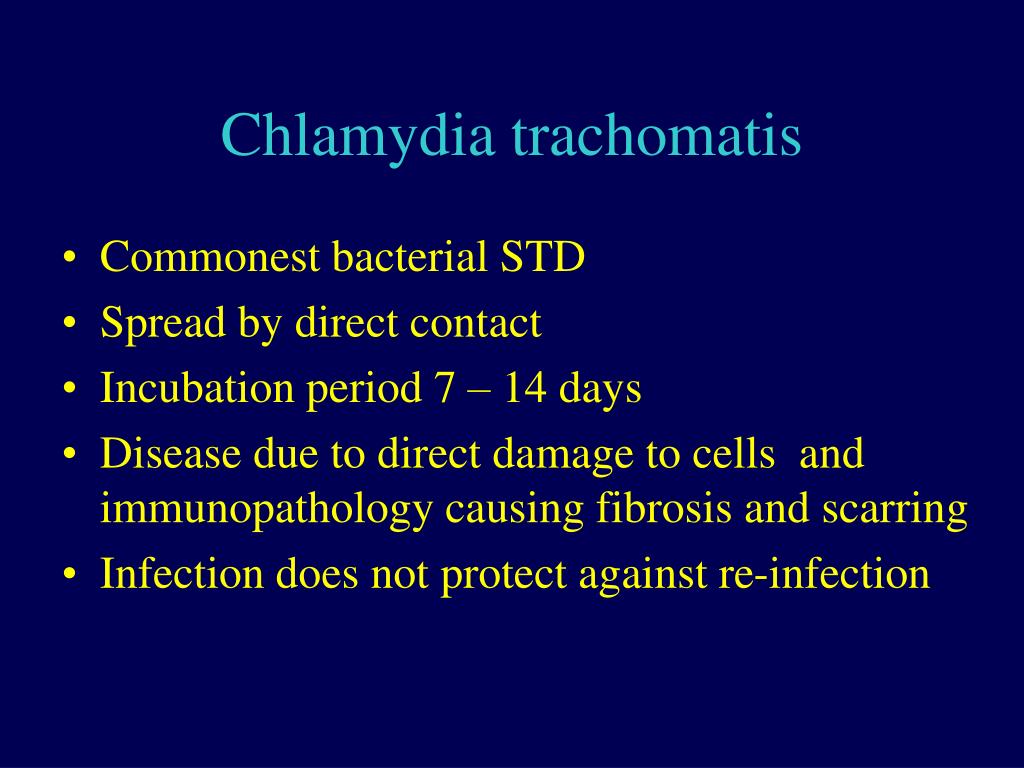

Chlamydia is a common STD caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. It can cause cervicitis, urethritis, and proctitis.

In women, these infections can lead to:

- pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),

- tubal factor infertility,

- ectopic pregnancy, and

- chronic pelvic pain.

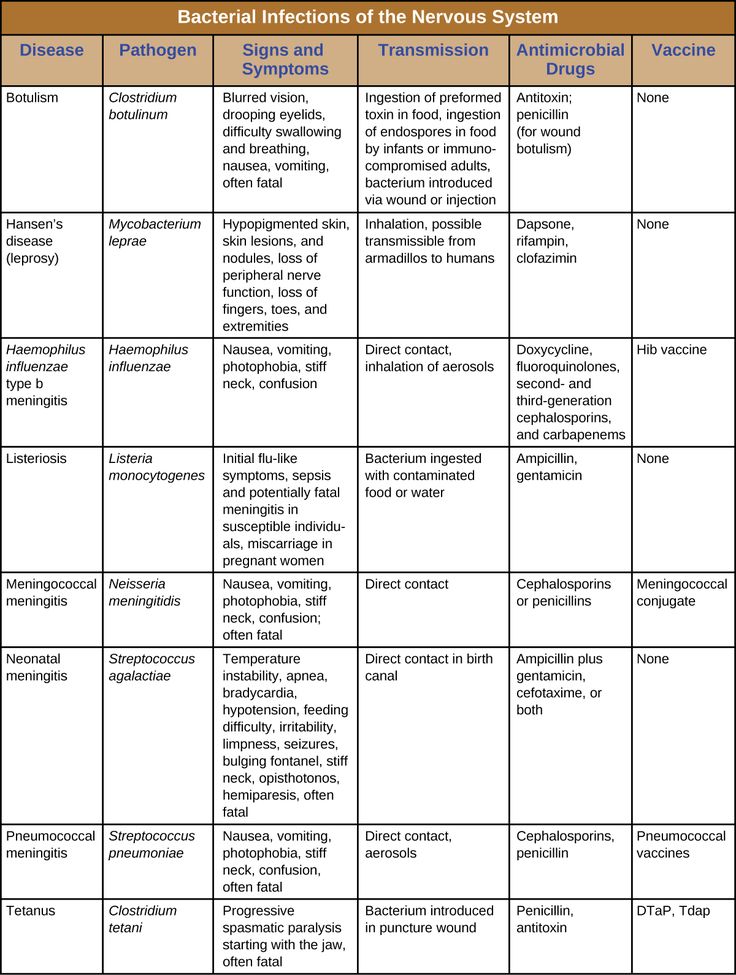

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is another type of STD caused by C. trachomatis. LGV is the cause of recent proctitis outbreaks among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) worldwide.1,2

How common is chlamydia?

CDC estimates that there were four million chlamydial infections in 2018.3 Chlamydia is also the most frequently reported bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the United States.4 It is difficult to account for many cases of chlamydia. Most people with the infection have no symptoms and do not seek testing. Chlamydia is most common among young people. Two-thirds of new chlamydial infections occur among youth aged 15-24 years.3 Estimates show that 1 in 20 sexually active young women aged 14-24 years has chlamydia.5

Disparities persist among racial and ethnic minority groups. In 2020, chlamydia rates for African Americans/Blacks were six times that of Whites.4 Chlamydia is also common among MSM. Among MSM screened for rectal chlamydial infection, positivity ranges from 3.0% to 10.5%.6,7 Among MSM screened for pharyngeal chlamydial infection, positivity has ranges from 0.5% to 2.3%.7.8

How do people get chlamydia?

Chlamydia spreads through vaginal, anal, or oral sex with someone with the infection. Semen does not have to be present to get or spread the infection.

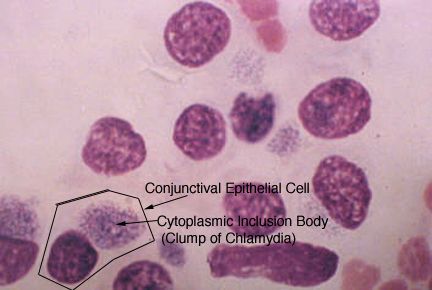

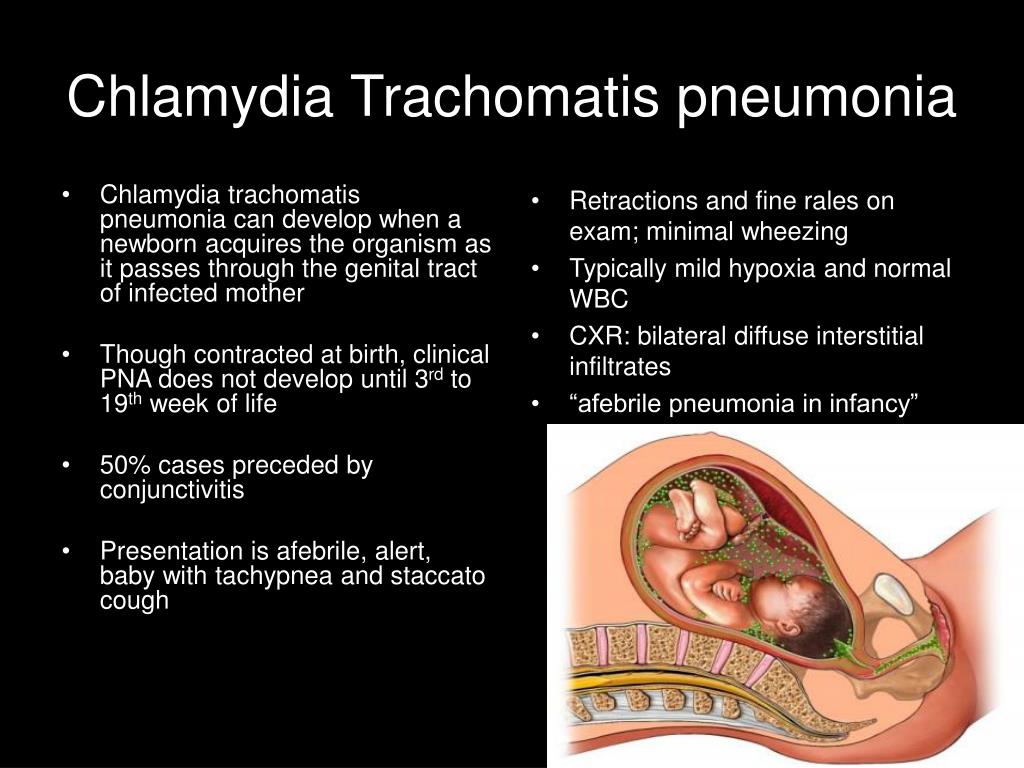

Pregnant people can give chlamydia to their baby during childbirth. This can cause ophthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis) or pneumonia in some infants. 9-12 Rectal or genital infection can persist one year or longer in infants infected at birth.13 However, sexual abuse should be a consideration among young children with vaginal, urethral, or rectal infection beyond the neonatal period.

9-12 Rectal or genital infection can persist one year or longer in infants infected at birth.13 However, sexual abuse should be a consideration among young children with vaginal, urethral, or rectal infection beyond the neonatal period.

People treated for chlamydia can get the infection again if they have sex with a person with chlamydia.14

Who is at risk for chlamydia?

Sexually active people can get chlamydia through vaginal, anal, or oral sex without a condom with a partner who has chlamydia. It is a very common STD, especially among young people.3

Sexually active young people are at high risk of getting chlamydia for behavioral, biological, and cultural reasons. Some don’t always use condoms.15 Some may move from one monogamous relationship to another during the likely infectivity period of chlamydia. This can increase the risk of transmission.16 Teenage girls and young women may have cervical ectopy (where cells from the endocervix are present on the ectocervix). 17 Cervical ectopy may increase susceptibility to chlamydial infection. High chlamydia prevalence among young people also may reflect barriers to accessing STD prevention services. These barriers can include lack of transportation, cost, and perceived stigma.16-20

17 Cervical ectopy may increase susceptibility to chlamydial infection. High chlamydia prevalence among young people also may reflect barriers to accessing STD prevention services. These barriers can include lack of transportation, cost, and perceived stigma.16-20

MSM are also at risk for infection since chlamydia can spread by oral or anal sex. Among MSM screened for rectal infection, positivity ranges from 3.0% to 10.5%.6.7 Among MSM screened for pharyngeal infection, positivity ranges from 0.5% to 2.3%.7.8

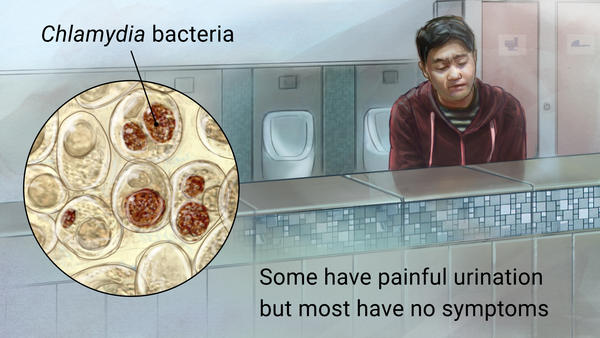

What are the symptoms of chlamydia?

Some refer to chlamydia as a “silent” infection. This is because most people with the infection have no symptoms or abnormal physical exam findings. Studies find that the proportion of people with chlamydia who develop symptoms vary by setting and study methodology. Two modeling studies estimate that about 10% of men and 5-30% of women with a confirmed infection develop symptoms.21. 22 The incubation period of chlamydia is unclear. Given the relatively slow replication cycle of the organism, symptoms may not appear until several weeks after exposure in people who develop symptoms.

22 The incubation period of chlamydia is unclear. Given the relatively slow replication cycle of the organism, symptoms may not appear until several weeks after exposure in people who develop symptoms.

In women, the bacteria initially infect the cervix. This may cause signs and symptoms of cervicitis (e.g., mucopurulent endocervical discharge, easily induced endocervical bleeding). It also can infect the urethra. This may cause signs and symptoms of urethritis (e.g., pyuria, dysuria, urinary frequency). Infection can spread from the cervix to the upper reproductive tract (i.e., uterus, fallopian tubes), causing PID. PID may be asymptomatic (“subclinical PID”)23 or acute, with typical symptoms of abdominal and/or pelvic pain. Signs of cervical motion tenderness and uterine or adnexal tenderness also may occur during examination.

Men with symptoms typically have urethritis, with a mucoid or watery urethral discharge and dysuria. Some men develop epididymitis (with or without symptomatic urethritis) with unilateral testicular pain, tenderness, and swelling. 24

24

Chlamydia can infect the rectum in men and women. This can happen either directly (through receptive anal sex), or via spread from the cervix and vagina in a woman.25, 26 While these infections often have no symptoms, they can cause symptoms of proctitis (e.g., rectal pain, discharge, and/or bleeding).26-28

Conjunctivitis can occur in both men and women through contact with infected genital secretions.29

While chlamydia can also spread to the throat by having oral sex, there are typically no symptoms. It also does not appear to be an important cause of pharyngitis.26

What health problems can result from chlamydia?

The initial damage that chlamydia causes is often unnoticed. However, infections can lead to serious health problems with both short- and long-term effects.

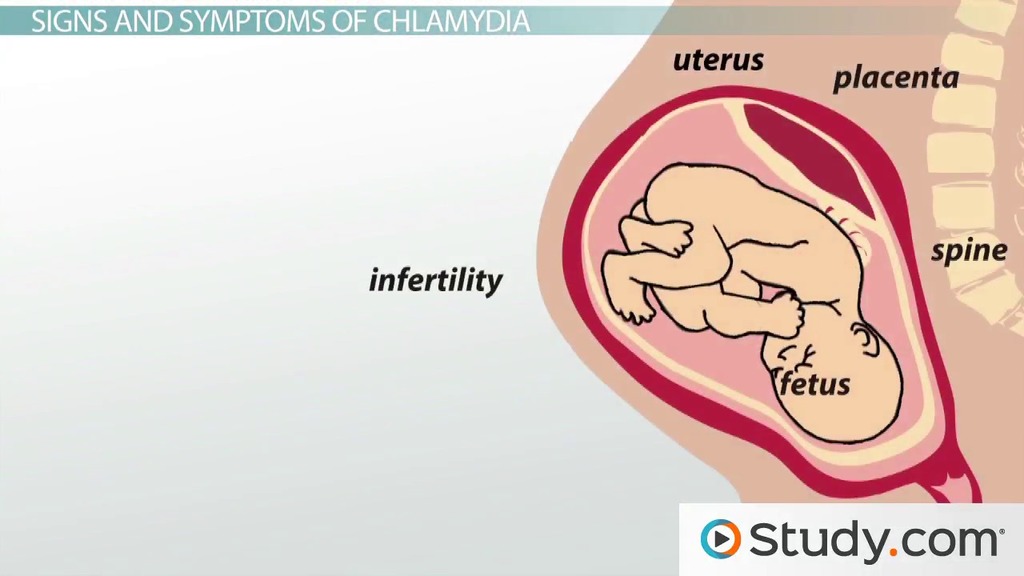

If a woman does not receive treatment, chlamydia can spread into the uterus or fallopian tubes, causing PID. Symptomatic PID occurs in about 10-15% of women who do not receive treatment. 30,31 However, chlamydia can also cause subclinical inflammation of the upper genital tract (“subclinical PID”). Both acute and subclinical PID can cause long-term damage to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and surrounding tissues. The damage can lead to chronic pelvic pain, tubal factor infertility, and potentially fatal ectopic pregnancy.32,33

30,31 However, chlamydia can also cause subclinical inflammation of the upper genital tract (“subclinical PID”). Both acute and subclinical PID can cause long-term damage to the fallopian tubes, uterus, and surrounding tissues. The damage can lead to chronic pelvic pain, tubal factor infertility, and potentially fatal ectopic pregnancy.32,33

Some patients with PID develop perihepatitis, or “Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome”. This syndrome includes inflammation of the liver capsule and surrounding peritoneum, which can cause right upper quadrant pain.

In pregnant people, untreated chlamydia can lead to pre-term delivery,34 ophthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis), and pneumonia in the newborn.

Reactive arthritis can occur in men and women, following infection with or without symptoms. This is sometimes part of a triad of symptoms (with urethritis and conjunctivitis) formerly referred to as Reiter’s Syndrome.35

What about chlamydia and HIV?

Untreated chlamydia may increase a person’s chances of getting or transmitting HIV. 36

36

How does chlamydia affect a pregnant person and their baby?

In newborns, untreated chlamydia can cause:

- pre-term delivery,34

- ophthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis),

- and pneumonia.

Prospective studies show that chlamydial conjunctivitis and pneumonia occur in 18-44% and 3-16%, respectively, of infants born to those with chlamydia. 9-12 Neonatal prophylaxis against gonococcal conjunctivitis routinely performed at birth does not effectively prevent chlamydial conjunctivitis.37-39

Screening for and treating chlamydia in pregnant people is the best way to prevent disease in infants. At the first prenatal visit and during the third trimester, screen:

- All pregnant people under age 25; and

- All pregnant people 25 years and older at increased risk for chlamydia (e.g., those who have a new or more than one sex partner).

Retest those with infection four weeks and three months after they complete treatment. 40

40

Who to test for chlamydia?

Anyone with the following genital symptoms should not have sex until they see a healthcare provider:

- A discharge

- A burning sensation when peeing

- Unusual sores, or a rash

Anyone having oral, anal, or vaginal sex with a partner recently diagnosed with an STD should see a healthcare provider.

Because chlamydia usually has no symptoms, screening is necessary to identify most infections. Screening programs can reduce rates of adverse sequelae in women.31,41 CDC recommends yearly chlamydia screening of all sexually active women younger than 25. CDC also recommends screening for older women with risk factors, such as new or multiple partners, or a sex partner who has a sexually transmitted infection.40 Screen and treat those who are pregnant as noted in “How does chlamydia affect a pregnant person and their baby?” Women who are sexually active should discuss their risk factors with a healthcare provider to determine if more frequent screening is necessary.

Routine screening is not necessary for men. However, consider screening sexually active young men in clinical settings with a high prevalence of chlamydia. This can include adolescent clinics, correctional facilities, and STD clinics. Consider this when resources permit and do not hinder screening efforts in women.40

Screen sexually active MSM who have insertive intercourse for urethral chlamydial infection. Also screen MSM who have receptive anal intercourse for rectal infection at least yearly. Screening for pharyngeal infection is not recommended. MSM, including those with HIV, should receive more frequent chlamydia screening at 3- to 6-month intervals, if risk behaviors persist or if they or their sexual partners have multiple partners.40

At the initial HIV care visit, providers should test all sexually active people for chlamydia. Test at least each year during HIV care. A patient’s healthcare provider might determine more frequent screening is necessary, based on the patient’s risk factors. 42

42

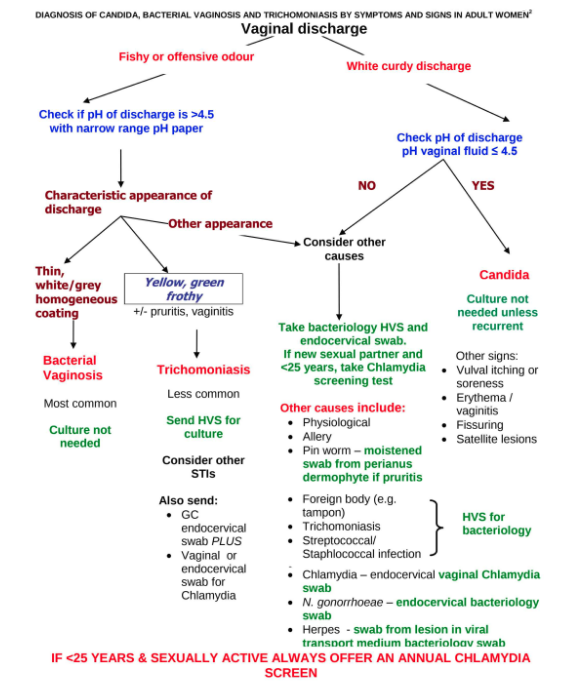

How is chlamydia diagnosed?

Diagnose chlamydia with nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), cell culture, and other types of tests. NAATs are the most sensitive tests to use on easy-to-obtain specimens. This includes vaginal swabs (either clinician- or patient-collected) or urine.43

To diagnose genital chlamydia in women using a NAAT, vaginal swabs are the optimal specimen. Urine is the specimen of choice for men. Urine is an effective alternative specimen type for women.43 Self-collected vaginal swab specimens perform as well as other approved specimens using NAATs.44 Patients may prefer self-collected vaginal swabs or urine-based screening to more invasive specimen collection.45 Adolescent girls may be good candidates for self-collected vaginal swab- or urine-based screening.

Diagnose rectal or pharyngeal infection by testing at the anatomic exposure site. While useful for these specimens, culture is not widely available. Additionally, NAATs have better sensitivity and specificity compared with culture for detecting C. trachomatis at non-genital sites.46-48 Most tests, including NAATs, are not FDA-cleared for use with rectal or pharyngeal swab specimens. NAATs have better sensitivity and specificity compared with culture for the detection of C. trachomatis at rectal sites.46-48 However, some laboratories have met set requirements and have validated NAAT testing on rectal and pharyngeal swab specimens.

Additionally, NAATs have better sensitivity and specificity compared with culture for detecting C. trachomatis at non-genital sites.46-48 Most tests, including NAATs, are not FDA-cleared for use with rectal or pharyngeal swab specimens. NAATs have better sensitivity and specificity compared with culture for the detection of C. trachomatis at rectal sites.46-48 However, some laboratories have met set requirements and have validated NAAT testing on rectal and pharyngeal swab specimens.

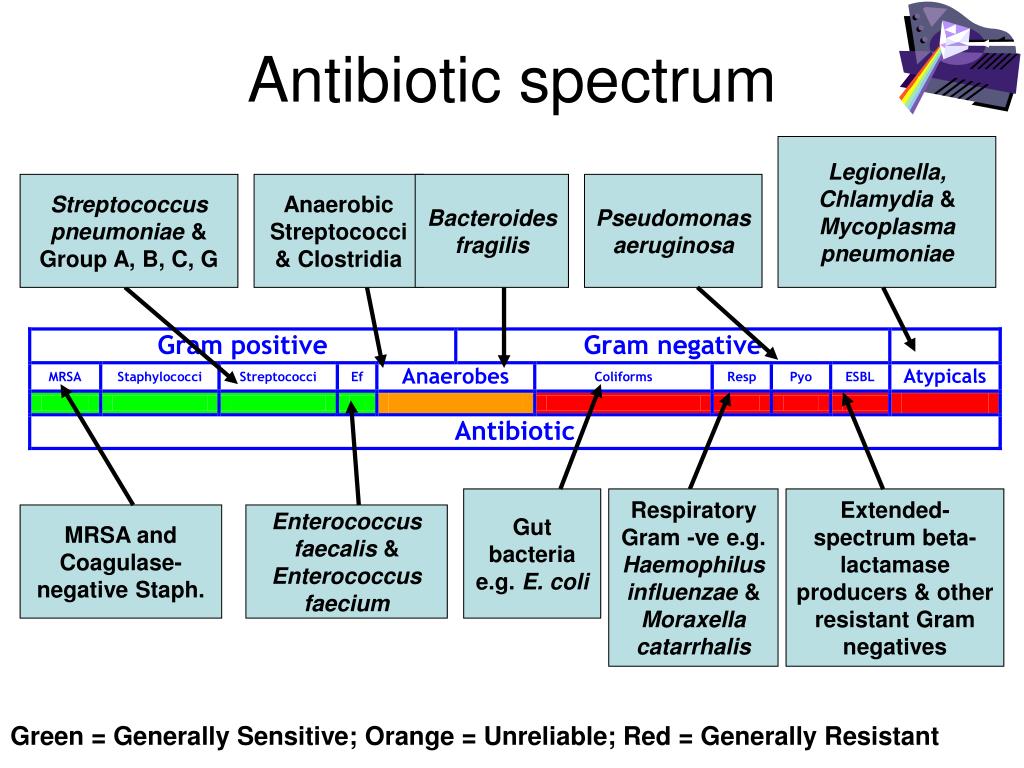

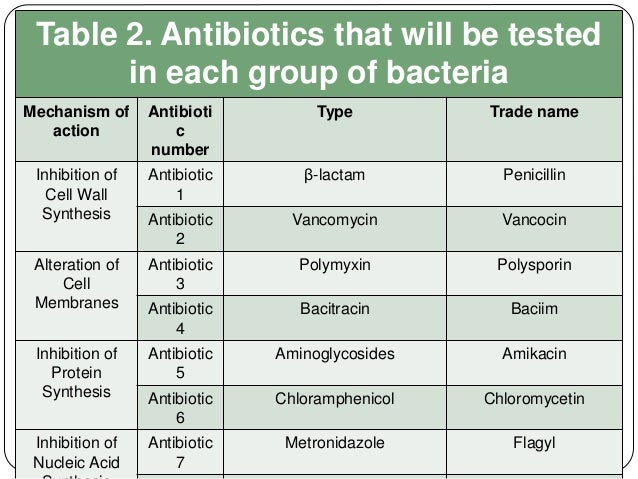

What is the treatment for chlamydia?

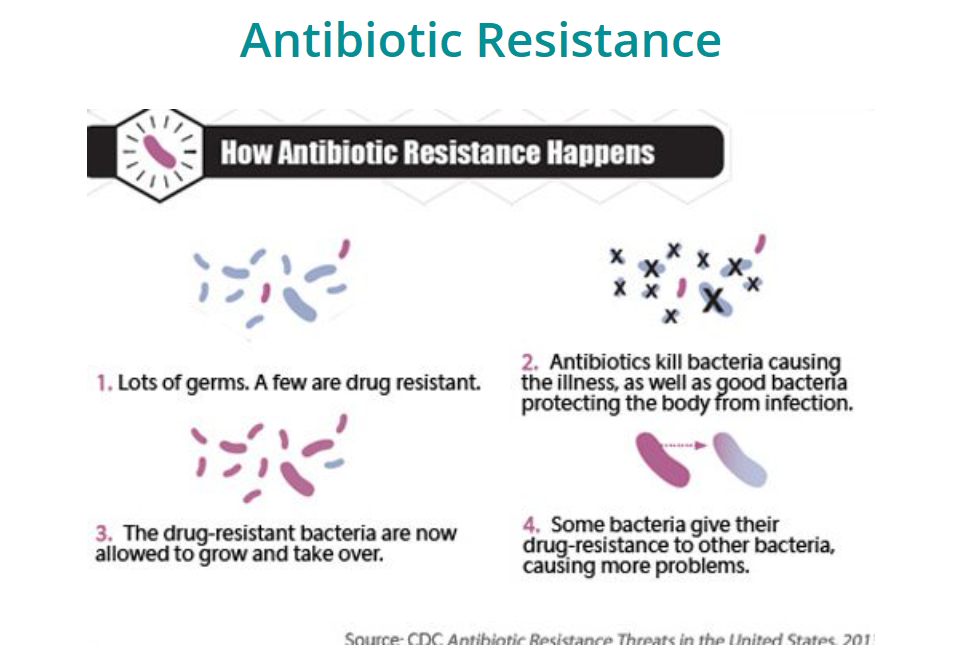

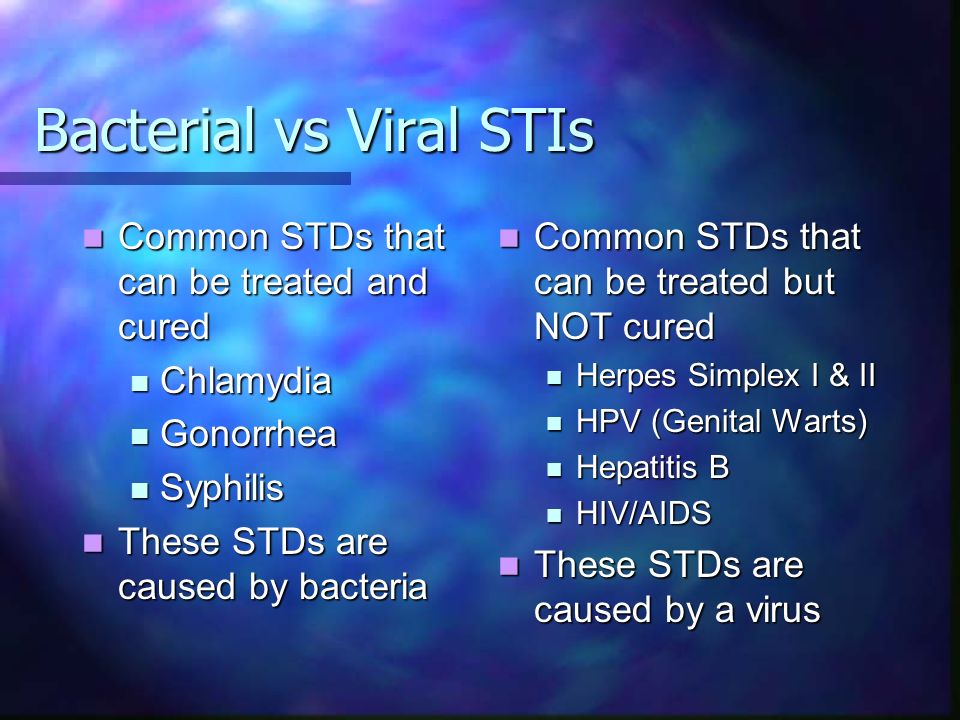

Antibiotics can easily cure chlamydia. Treatment options are the same, whether a person also has HIV or not.

Patients treated with single-dose antibiotics should not have sex for seven days. Patients treated with a seven-day course of antibiotics should not have sex until they complete treatment, and their symptoms are gone. This helps prevent spreading the infection to sex partners. It is important to take all medicine prescribed to cure chlamydia. Medicine should not be shared with anyone. Although treatment will cure the infection, it will not repair any long-term damage done by the disease. If a person’s symptoms continue for more than a few days after receiving treatment, a healthcare provider should reevaluate them.

Medicine should not be shared with anyone. Although treatment will cure the infection, it will not repair any long-term damage done by the disease. If a person’s symptoms continue for more than a few days after receiving treatment, a healthcare provider should reevaluate them.

Repeat infection with chlamydia is common.49 Women whose sex partners do not receive appropriate treatment are at high risk for re-infection. Having multiple chlamydial infections increases a woman’s risk of serious reproductive health problems (e.g., PID and ectopic pregnancy).50,51 A healthcare provider should retest those with chlamydia about three months after treatment of an initial infection. Retesting is necessary even if their partners receive successful treatment.40

Infants with chlamydia may develop conjunctivitis and/or pneumonia.10 Healthcare providers can treat infection in infants with antibiotics.

What about partners?

People treated for chlamydia should tell their recent sex partners so the partner can see a healthcare provider. “Recent” partners include anyone the patient had anal, vaginal, or oral sex with in the 60 days before symptom onset or diagnosis. This will help protect the partner from health problems and prevent re-infection.

“Recent” partners include anyone the patient had anal, vaginal, or oral sex with in the 60 days before symptom onset or diagnosis. This will help protect the partner from health problems and prevent re-infection.

Patients treated with single-dose antibiotics should not have sex for seven days. Patients treated with a seven-day course of antibiotics should not have sex until they complete treatment, and their symptoms go away.

For tips on talking to partners about sex and STD testing, visit www.gytnow.org/talking-to-your-partner/

In some states, healthcare providers may give people with chlamydia extra medicine or prescriptions to give to their sex partner(s). This is called “expedited partner therapy”, or “EPT.” Clinical trials comparing EPT to asking the patient to refer their partners in for treatment find that EPT leads to fewer re-infections in the index patient and more partner treatment.52 EPT is another strategy providers use to manage the partners of people with chlamydial infection. Partners should still seek medical care, regardless of whether they receive EPT. For more information about EPT, including the legal status in a specific area, see Legal Status of Expedited Partner Therapy.

How can chlamydia be prevented?

Condoms, when used correctly, every time someone has sex can reduce the risk of getting or giving chlamydia.53 The only way to completely avoid chlamydia is to not have vaginal, anal, and oral sex. Another option is being in a long-term, mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and does not have chlamydia.

References

1. O’Farrell N, Morison L, Moodley P, et al. Genital ulcers and concomitant complaints in men attending a sexually transmitted infections clinic: implications for sexually transmitted infections management. Sexually transmitted diseases 2008;35:545-9.

2. White JA. Manifestations and management of lymphogranuloma venereum. Current opinion in infectious diseases 2009;22:57-66.

3. Kreisel KM, Spicknall IH, Gargano JW, Lewis FM, Lewis RM, Markowitz LE, Roberts H, Satcher Johnson A, Song R, St. Cyr SB, Weston EJ, Torrone EA, Weinstock HS. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: Prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sex Transm Dis 2021; in press.

4. CDC. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2020. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; April 2022.

5. Torrone E, Papp J, Weinstock H. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infection Among Persons Aged 14–39 Years — United States, 2007–2012. MMWR 2014;63:834-8.

6. Marcus JL, Bernstein KT, Stephens SC, et al. Sentinel surveillance of rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea among males–San Francisco, 2005-2008. Sexually transmitted diseases 2010;37:59-61.

7. Pinsky L, Chiarilli DB, Klausner JD, et al. Rates of asymptomatic nonurethral gonorrhea and chlamydia in a population of university men who have sex with men. Journal of American college health : J of ACH 2012;60:481-4.

8. Park J, Marcus JL, Pandori M, Snell A, Philip SS, Bernstein KT. Sentinel surveillance for pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea among men who have sex with men–San Francisco, 2010. Sexually transmitted diseases 2012;39:482-4.

9. Frommell GT, Rothenberg R, Wang S, McIntosh K. Chlamydial infection of mothers and their infants. The Journal of pediatrics 1979;95:28-32.

10. Hammerschlag MR, Chandler JW, Alexander ER, English M, Koutsky L. Longitudinal studies on chlamydial infections in the first year of life. Pediatric infectious disease 1982;1:395-401.

11. Heggie AD, Lumicao GG, Stuart LA, Gyves MT. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in mothers and infants. A prospective study. American journal of diseases of children (1960) 1981;135:507-11.

12. Schachter J, Grossman M, Sweet RL, Holt J, Jordan C, Bishop E. Prospective study of perinatal transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1986;255:3374-7.

13. Bell TA, Stamm WE, Wang SP, Kuo CC, Holmes KK, Grayston JT. Chronic Chlamydia trachomatis infections in infants. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1992;267:400-2.

14. Batteiger BE, Tu W, Ofner S, et al. Repeated Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections in adolescent women. The Journal of infectious diseases 2010;201:42-51.

15. Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2011. Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries (Washington, DC : 2002) 2012;61:1-162.

16. Kraut-Becher JR, Aral SO. Gap length: an important factor in sexually transmitted disease transmission. Sexually transmitted diseases 2003;30:221-5.

17. Singer A. The uterine cervix from adolescence to the menopause. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1975;82:81-99.

18. Cunningham SD, Kerrigan DL, Jennings JM, Ellen JM. Relationships between perceived STD-related stigma, STD-related shame and STD screening among a household sample of adolescents. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health 2009;41:225-30.

19. Elliott BA, Larson JT. Adolescents in mid-sized and rural communities: foregone care, perceived barriers, and risk factors. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine 2004;35:303-9.

20. Tilson EC, Sanchez V, Ford CL, et al. Barriers to asymptomatic screening and other STD services for adolescents and young adults: focus group discussions. BMC public health 2004;4:21.

21. Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Preventive medicine 2003;36:502-9.

22. Korenromp EL, Sudaryo MK, de Vlas SJ, et al. What proportion of episodes of gonorrhoea and chlamydia becomes symptomatic? International journal of STD & AIDS 2002;13:91-101.

23. Wiesenfeld HC, Sweet RL, Ness RB, Krohn MA, Amortegui AJ, Hillier SL. Comparison of acute and subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Sexually transmitted diseases 2005;32:400-5.

24. Berger RE, Alexander ER, Monda GD, Ansell J, McCormick G, Holmes KK. Chlamydia trachomatis as a cause of acute “idiopathic” epididymitis. The New England journal of medicine 1978;298:301-4.

25. Barry PM, Kent CK, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Results of a program to test women for rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea. Obstetrics and gynecology 2010;115:753-9.

26. Jones RB, Rabinovitch RA, Katz BP, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis in the pharynx and rectum of heterosexual patients at risk for genital infection. Annals of internal medicine 1985;102:757-62.

27. Quinn TC, Goodell SE, Mkrtichian E, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis proctitis. The New England journal of medicine 1981;305:195-200.

28. Thompson CI, MacAulay AJ, Smith IW. Chlamydia trachomatis infections in the female rectums. Genitourinary medicine 1989;65:269-73.

29. Kalayoglu MV. Ocular chlamydial infections: pathogenesis and emerging treatment strategies. Current drug targets Infectious disorders 2002;2:85-91.

30. Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD, Low N, Xu F, Ness RB. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. The Journal of infectious diseases 2010;201 Suppl 2:S134-55.

31. Oakeshott P, Kerry S, Aghaizu A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of screening for Chlamydia trachomatis to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease: the POPI (prevention of pelvic infection) trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2010;340:c1642.

32. Cates W, Jr., Wasserheit JN. Genital chlamydial infections: epidemiology and reproductive sequelae. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1991;164:1771-81.

33. Westrom L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, Hagdu A, Thompson SE. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility. A cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sexually transmitted diseases 1992;19:185-92.

34. Rours GI, Duijts L, Moll HA, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection during pregnancy associated with preterm delivery: a population-based prospective cohort study. European journal of epidemiology 2011;26:493-502.

European journal of epidemiology 2011;26:493-502.

35. Carter JD, Inman RD. Chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis: hidden in plain sight? Best practice & research Clinical rheumatology 2011;25:359-74.

36. Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sexually transmitted infections 1999;75:3-17.

37. Bell TA, Sandstrom KI, Gravett MG, et al. Comparison of ophthalmic silver nitrate solution and erythromycin ointment for prevention of natally acquired Chlamydia trachomatis. Sexually transmitted diseases 1987;14:195-200.

38. Chen JY. Prophylaxis of ophthalmia neonatorum: comparison of silver nitrate, tetracycline, erythromycin and no prophylaxis. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 1992;11:1026-30.

39. Isenberg SJ, Apt L, Wood M. A controlled trial of povidone-iodine as prophylaxis against ophthalmia neonatorum. The New England journal of medicine 1995;332:562-6.

The New England journal of medicine 1995;332:562-6.

40. Workowski, KA, Bachmann, LH, Chang, PA, et. al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep 2021; 70(No. 4): 1-187.

41. Scholes D, Stergachis A, Heidrich FE, Andrilla H, Holmes KK, Stamm WE. Prevention of pelvic inflammatory disease by screening for cervical chlamydial infection. The New England journal of medicine 1996;334:1362-6.

42. CDC. Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Recommendations of CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control 2003;52:1-24.

43. APHL. Laboratory Diagnostic Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Consultation Meeting Summary Report. January 13-15, 2009. Atlanta, GA.

January 13-15, 2009. Atlanta, GA.

44. Schachter J, Chernesky MA, Willis DE, et al. Vaginal swabs are the specimens of choice when screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: results from a multicenter evaluation of the APTIMA assays for both infections. Sexually transmitted diseases 2005;32:725-8.

45. Doshi JS, Power J, Allen E. Acceptability of chlamydia screening using self-taken vaginal swabs. International journal of STD & AIDS 2008;19:507-9.

46. Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis rectal infections. Journal of clinical microbiology 2010;48:1827-32.

47. Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, Reisner SL, et al. Asymptomatic gonorrhea and chlamydial infections detected by nucleic acid amplification tests among Boston area men who have sex with men. Sexually transmitted diseases 2008;35:495-8.

48. Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, Shayevich C, Klausner JD. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sexually transmitted diseases 2008;35:637-42.

Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sexually transmitted diseases 2008;35:637-42.

49. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sexually transmitted diseases 2009;36:478-89.

50. Hillis SD, Owens LM, Marchbanks PA, Amsterdam LF, Mac Kenzie WR. Recurrent chlamydial infections increase the risks of hospitalization for ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1997;176:103-7.

51. Bakken IJ, Skjeldestad FE, Lydersen S, Nordbo SA. Births and ectopic pregnancies in a large cohort of women tested for Chlamydia trachomatis. Sexually transmitted diseases 2007;34:739-43.

52. Trelle S, Shang A, Nartey L, Cassell JA, Low N. Improved effectiveness of partner notification for patients with sexually transmitted infections: systematic review. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2007;334:354.

BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2007;334:354.

53. Holmes KK, Levine R, Weaver M. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2004;82:454-61.

Chlamydia Infections | Chlamydia | Chlamydia Symptoms

On this page

Basics

- Summary

- Start Here

- Diagnosis and Tests

Learn More

- Related Issues

See, Play and Learn

- Images

Research

- Clinical Trials

- Journal Articles

Resources

- Find an Expert

For You

- Children

- Women

- Patient Handouts

What is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is a common sexually transmitted disease. It is caused by bacteria called Chlamydia trachomatis. It can infect both men and women. Women can get chlamydia in the cervix, rectum, or throat. Men can get chlamydia in the urethra (inside the penis), rectum, or throat.

It is caused by bacteria called Chlamydia trachomatis. It can infect both men and women. Women can get chlamydia in the cervix, rectum, or throat. Men can get chlamydia in the urethra (inside the penis), rectum, or throat.

How do you get chlamydia?

You can get chlamydia during oral, vaginal, or anal sex with someone who has the infection. A woman can also pass chlamydia to her baby during childbirth.

If you've had chlamydia and were treated in the past, you can get re-infected if you have unprotected sex with someone who has it.

Who is at risk of getting chlamydia?

Chlamydia is more common in young people, especially young women. You are more likely to get it if you don't consistently use a condom, or if you have multiple partners.

What are the symptoms of chlamydia?

Chlamydia doesn't usually cause any symptoms. So you may not realize that you have it. People with chlamydia who have no symptoms can still pass the disease to others. If you do have symptoms, they may not appear until several weeks after you have sex with an infected partner.

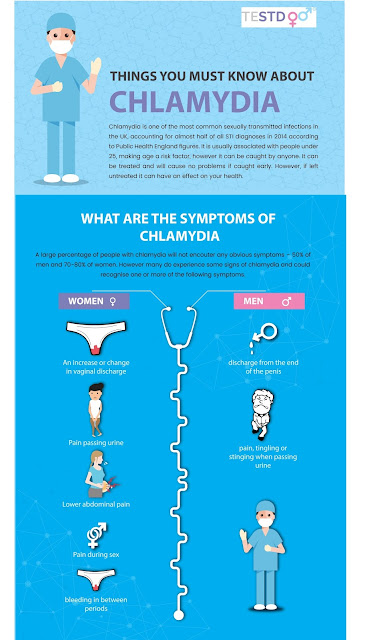

Symptoms in women include:

- Abnormal vaginal discharge, which may have a strong smell

- A burning sensation when urinating

- Pain during intercourse

If the infection spreads, you might get lower abdominal pain, pain during sex, nausea, or fever.

Symptoms in men include:

- Discharge from your penis

- A burning sensation when urinating

- Burning or itching around the opening of your penis

- Pain and swelling in one or both testicles (although this is less common)

If the chlamydia infects the rectum (in men or women), it can cause rectal pain, discharge, and/or bleeding.

How is chlamydia diagnosed?

There are lab tests to diagnose chlamydia. Your health care provider may ask you to provide a urine sample. For women, providers sometimes use (or ask you to use) a cotton swab to get a sample from your vagina to test for chlamydia.

Who should be tested for chlamydia?

You should go to your health provider for a test if you have symptoms of chlamydia, or if you have a partner who has a sexually transmitted disease. Pregnant women should get a test when they go to their first prenatal visit.

Pregnant women should get a test when they go to their first prenatal visit.

People at higher risk should get checked for chlamydia every year:

- Sexually active women 25 and younger

- Older women who have new or multiple sex partners, or a sex partner who has a sexually transmitted disease

- Men who have sex with men (MSM)

What other problems can chlamydia cause?

In women, an untreated infection can spread to your uterus and fallopian tubes, causing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID can cause permanent damage to your reproductive system. This can lead to long-term pelvic pain, infertility, and ectopic pregnancy. Women who have had chlamydia infections more than once are at higher risk of serious reproductive health complications.

Men often don't have health problems from chlamydia. Sometimes it can infect the epididymis (the tube that carries sperm). This can cause pain, fever, and, rarely, infertility.

Both men and women can develop reactive arthritis because of a chlamydia infection. Reactive arthritis is a type of arthritis that happens as a "reaction" to an infection in the body.

Reactive arthritis is a type of arthritis that happens as a "reaction" to an infection in the body.

Babies born to infected mothers can get eye infections and pneumonia from chlamydia. It may also make it more likely for your baby to be born too early.

Untreated chlamydia may also increase your chances of getting or giving HIV/AIDS.

What are the treatments for chlamydia?

Antibiotics will cure the infection. You may get a one-time dose of the antibiotics, or you may need to take medicine every day for 7 days. Antibiotics cannot repair any permanent damage that the disease has caused.

To prevent spreading the disease to your partner, you should not have sex until the infection has cleared up. If you got a one-time dose of antibiotics, you should wait 7 days after taking the medicine to have sex again. If you have to take medicine every day for 7 days, you should not have sex again until you have finished taking all of the doses of your medicine.

It is common to get a repeat infection, so you should get tested again about three months after treatment.

Can chlamydia be prevented?

The only sure way to prevent chlamydia is to not have vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

Correct usage of latex condoms greatly reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of catching or spreading chlamydia. If your or your partner is allergic to latex, you can use polyurethane condoms.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Chlamydia - CDC Fact Sheet (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) - PDF

- Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

- Epididymitis (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research) Also in Spanish

- Chlamydia (VisualDX)

- ClinicalTrials.

gov: Chlamydia Infections (National Institutes of Health)

gov: Chlamydia Infections (National Institutes of Health)

- Article: Very High Incidence of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Treponema pallidum.

..

.. - Article: Application of nanopore adaptive sequencing in pathogen detection of a patient...

- Article: Determinants and prediction of Chlamydia trachomatis re-testing and re-infection within 1.

..

.. - Chlamydia Infections -- see more articles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Also in Spanish

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- Chlamydia (For Parents) (Nemours Foundation)

- Chlamydia (Department of Health and Human Services, Office on Women's Health) Also in Spanish

Chlamydia in men and women: treatment, symptoms.

Contents

Pathogenesis of chlamydia

Is it possible to get chlamydia through everyday life?

Risk Factors

Statistics on the disease

chlamydia - Symptoms

The first signs of chlamydia

The main symptoms of chlamydia in women

The main symptoms of chlamydia in men

Symptoms of chlamydia0003

How is chlamydia transmitted?

Types of chlamydia

Diagnosis of chlamydia

Pathogenesis of chlamydia

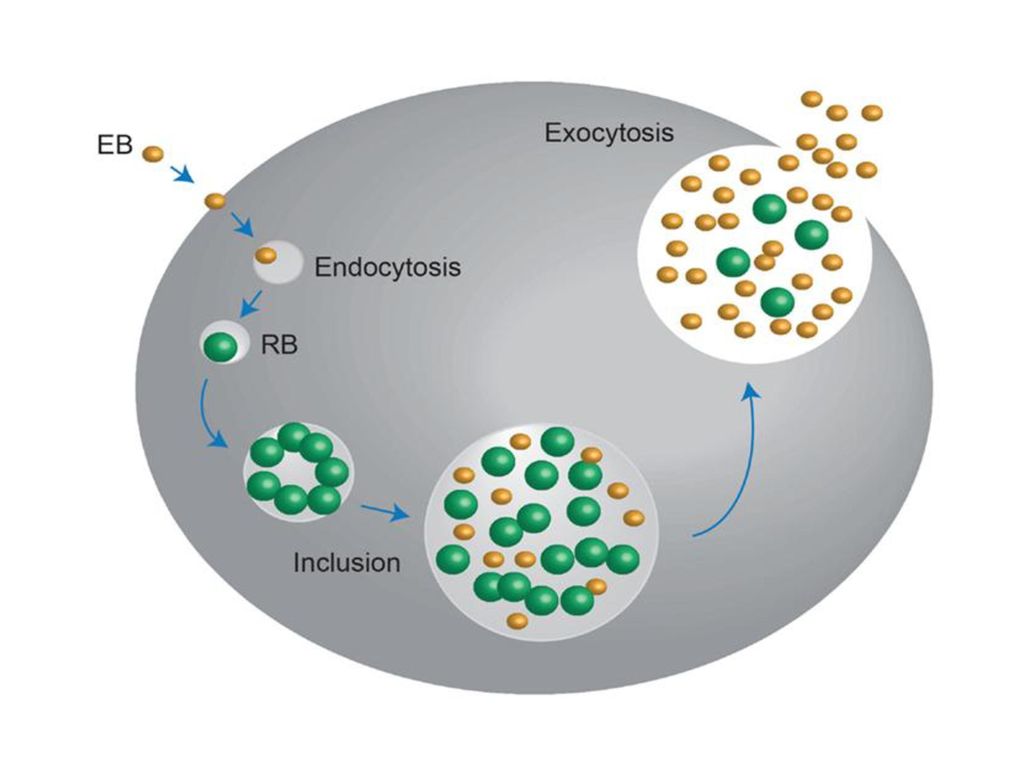

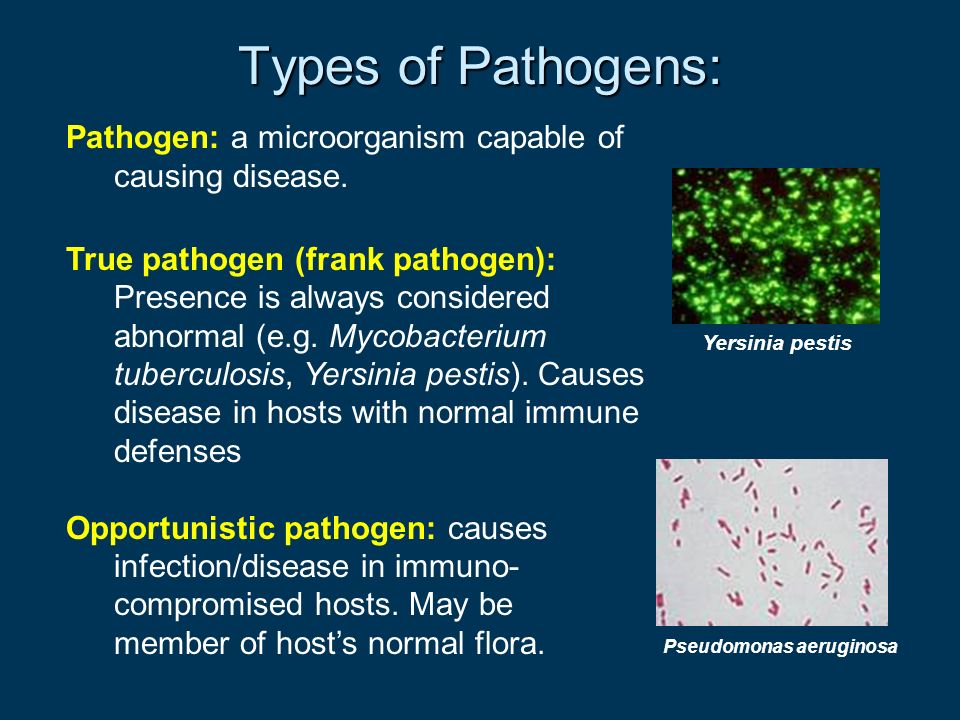

This sexually transmitted disease is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. This pathogenic, that is, pathogenic microorganism, like many related to it, is an obligate intracellular parasite. To put it simply, it cannot reproduce without being in a cage. Therefore, in order to cause disease, he needs to get there.

The infection goes like this:

- first, the bacterium attaches itself to the walls of the host cell;

- , surrounded by a shell, climbs inside and begins to multiply;

- after some time, the host dies, and the pathogen spreads throughout the body.

The first female organ that is affected by chlamydia is the uterus, and the male organ is the urethra, that is, the urethra.

Is it possible to get chlamydia by household means?

Chlamydia is transmitted mainly through sexual contact from an infected partner to a healthy one. Theoretically, this can happen at the household level, but certain conditions are needed for the reproduction of a pathogenic microorganism:

- no UV access;

- humidity must be high enough;

- temperature up to +20 degrees Celsius.

Chlamydia, once on a household item, can remain active for 48 hours, so it is theoretically possible to become infected. In families with low social responsibility, the pathogen is transmitted through household items and bedding. In practice, such cases, when all three factors coincide, are extremely rare. However, the disease can be obtained through contaminated dishes if there are wounds in the mouth.

Risk factors

Urogenital infection is transmitted sexually. But a sick mother can infect the baby during delivery. Also risk factors are:

- unprotected sex - refusal to use contraception;

- promiscuity in relationships of an intimate nature - frequent change of casual sexual partners;

- alcoholism and drug addiction.

It also increases the risk of disease in young people who start sexual life too early.

Today, chlamydia is a widespread infection. But it is interesting that it occurs no more often than other sexually transmitted diseases. For example, outbreaks of gonorrhea and other diseases belonging to this group are much more common.

Women are most susceptible to chlamydia, although men are also not immune:

- People who have had unprotected sex for the first time when they were very young and still continue to do so are at particular risk.

- Girls and women “with reduced social responsibility” risk their health the most.

Studies show that almost 100 million people are infected every year.

Chlamydia symptoms

This is a very insidious disease, since the infected person does not always suspect about its course. And he can remain in the dark for a long time, because the incubation period of this infection:

- minimum - 5 days;

- maximum is a month.

Those patients who managed to detect the disease in time were more fortunate, because the treatment of chlamydia is easier and more effective at an early stage.

Sometimes the pathological process proceeds with pronounced symptoms. Some of them are the same for both sexes. Most often, patients complain of fever and pain in the intimate area.

Early signs of chlamydia

Since the target organs are located in the lower back, prolonged and long-lasting pain in this area can signal chlamydia. Very often, such painful sensations, which can be observed in both men and women, are the first symptom.

There are manifestations that are more typical for men. For example, the patient should be wary if he found:

- pus impurities in the urine;

- swelling of the genital organs, accompanied by redness.

It is necessary to sound the alarm in cases where these symptoms do not stop for a long time. This means that pathogenic bacteria caused inflammation of the urethra.

Main symptoms of chlamydia in women

A woman infected with chlamydia will be able to understand that she is sick if:

- will see vaginal discharge with a repulsive odor on the pad;

- it comes to bleeding that appears when the patient has not yet begun critical days.

Pain that occurs during trips to the toilet can also serve as a signal that you need to make an appointment with a doctor as soon as possible.

Main symptoms of chlamydia in men

Men who have chlamydia often feel the urge to go to the bathroom to urinate. Doing this procedure is usually very painful for him. Worse, the pain may not be localized in the penis, but flow to other organs - for example:

Doing this procedure is usually very painful for him. Worse, the pain may not be localized in the penis, but flow to other organs - for example:

- for the prostate;

- bladder;

- sometimes on the intestines.

Like women, men are sometimes tormented by discharge, red due to the admixture of blood.

Symptoms of chlamydia in children

Usually, the causative bacterium enters the eyes of newborn children, as a result of which one of the mucous membranes, the conjunctiva, becomes inflamed. In this condition, the child's eyes:

- swell;

- blush;

- watery.

Respiratory chlamydia in an older child can be recognized by signs such as:

- cough and difficulty breathing;

- bluing of the skin;

- temperature increase.

In some cases, children have the same symptoms of chlamydia as adults - that is, frequent urination and scabies in the intimate area.

Consequences of chlamydia

In women who have been ill with chlamydia, the menstrual cycle often goes astray. But there are also more dangerous consequences for health, the worst of which is infertility:

- Often in the affected organs, that is, the ovaries, the uterus and the tubes leading to it, partitions - adhesions are formed.

- Their appearance leads to the fact that the egg cannot penetrate the uterus and be fertilized.

- Therefore, even after successful intercourse, such sick women rarely manage to become pregnant. And if she conceives a child, she cannot bear it for a long time.

Many of the women inflamed the inner surface of the uterus - this syndrome is called endometriosis.

Men fare no better - those who have had chlamydia:

- swelling of the prostate occurs;

- proliferation of fibrous tissue occurs;

- in some cases they suffer from Reiter's syndrome.

This condition is complex, because, in addition to the urethra, inflammatory processes occur in the joints and eyes.

Causes of chlamydia

Chlamydia often occurs due to multiple promiscuous relationships. They are infected by those who do not use protective equipment during intercourse.

Many children, especially young children, get chlamydia in a different way:

- When an infected mother gives birth, the child picks up pathogenic bacteria.

- This happens when the baby makes its way through her birth canal.

- But he becomes infected with chlamydia not only at birth, but also during breastfeeding, because the bacteria can enter his body with mother's milk.

In such cases, one speaks of vertical transmission of the infection. How to treat chlamydia in infants, the pediatrician will tell.

How is chlamydia transmitted?

Sexual contact is the most common way of transmitting chlamydia, but not the only one. You can get this infection if you touch an infected surface, and then shake someone's hand or touch an object. That is, the disease is also transmitted by contact-household means, although it is extremely rare.

That is, the disease is also transmitted by contact-household means, although it is extremely rare.

Types of chlamydia

Venereologists distinguish several types of this disease. It is subdivided depending on which organ it affects. Sometimes the focus of infection may be outside the reproductive system. For example, a pathogenic microbe can get into:

- nose;

- eyes;

- ears;

- lungs.

In the latter case, it is called respiratory. Mostly this chlamydia affects children.

That variety of it, which adversely affects the genitourinary system, is called urogenital. In women, because of it, they become inflamed:

- bladder;

- cervix;

- external and internal genital organs - vulva and vagina.

In a male patient with pathology, the prostate gland, prostate and urethra are affected.

Chlamydia diagnostics

It is possible to identify the presence or absence of a disease in a patient only by taking tests from him:

- for women, this swab is taken from the vagina;

- in men - from the opening leading to the urethra.

The materials collected from the patient are taken to the laboratory, where one part is sown on a special nutrient medium, and on the other, a PCR reaction is carried out. Such tests are done very quickly, so their results can be found out the very next day after applying. The deadline for receiving them is the second day after the patient arrives for diagnosis.

Chlamydia causes a very dangerous sexually transmitted disease. Even if it does not manifest itself in any way, you need to see a doctor and be examined. If it is detected, the doctor will give recommendations on how to cure chlamydia. And in order not to get infected with it, it is recommended to refrain from relationships "on the side" and do not forget to put on condoms before having sex.

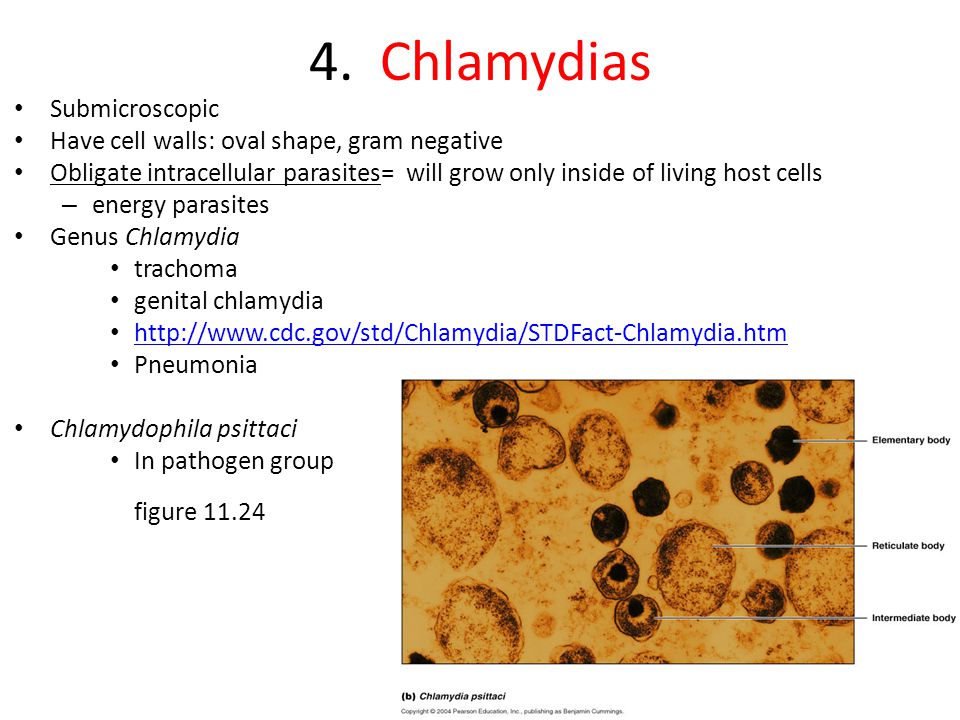

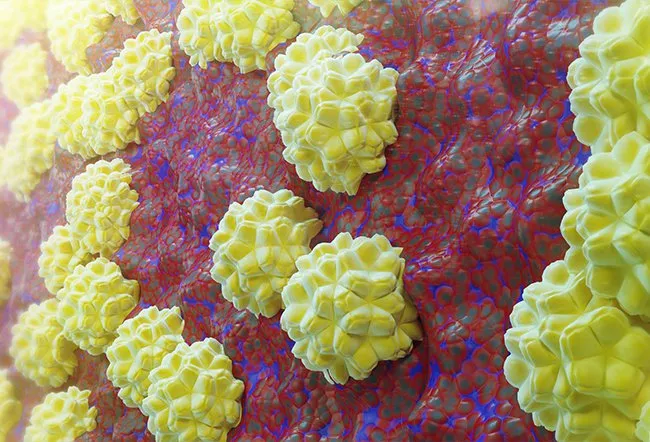

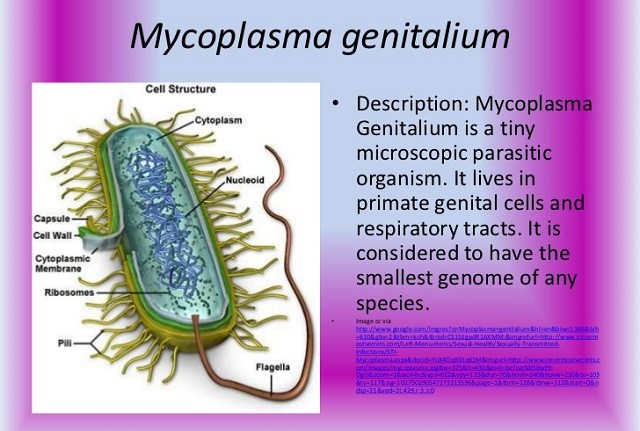

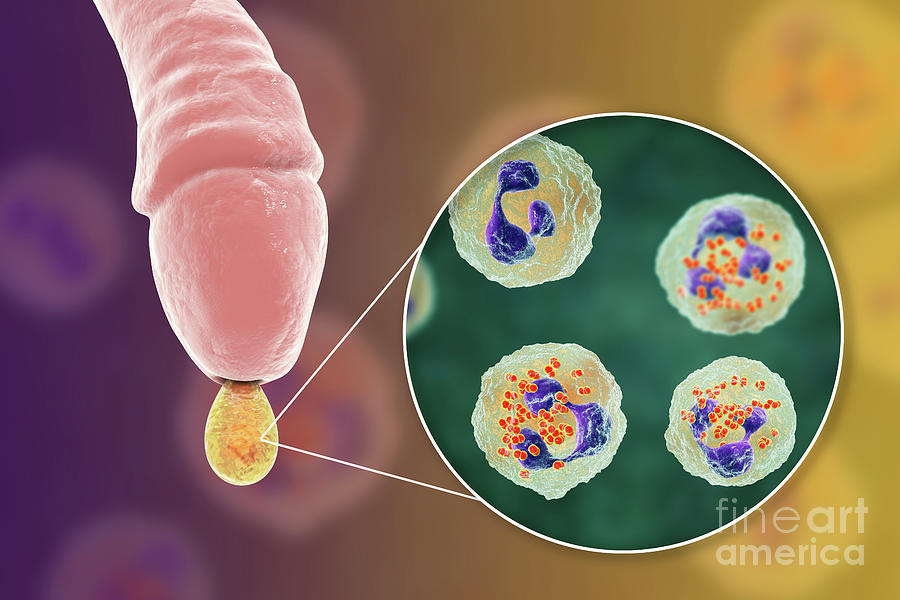

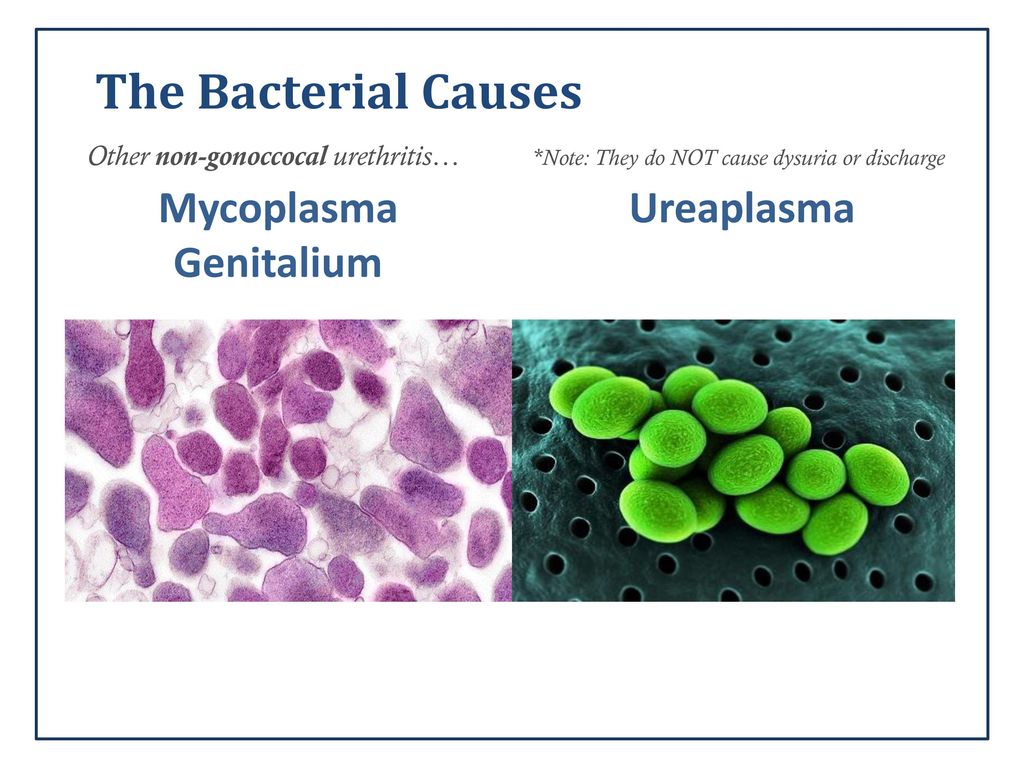

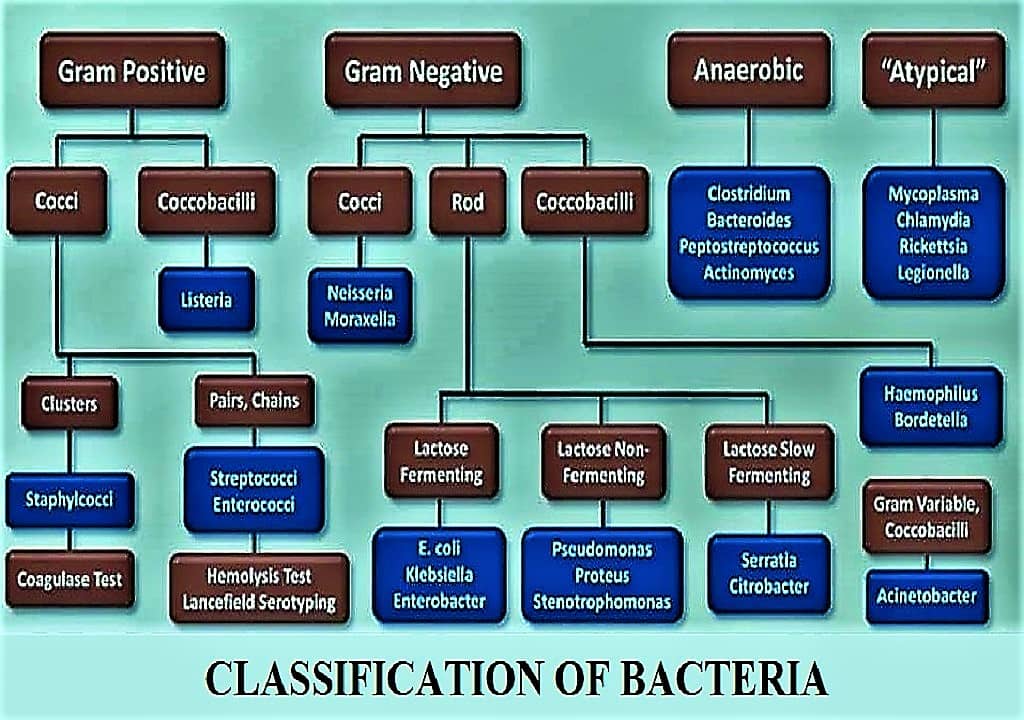

Biological properties of chlamydia

Chlamydia are small gram-negative, immobile, obligately parasitic bacteria, reticular bodies (RT) of which can be of various shapes - oval, crescent, in the form of bipolar rods and coccobacilli and have a size of 300 to 1000 nm, and elementary bodies (ET) of oval shape can have a size in diameter of 250 - 500 nm. ET chlamydia have infectious properties, antigenoactive, capable of penetrating into a sensitive cell, where a unique cycle of chlamydia development occurs. Preceding Chlamydia ET, larger RTs do not have a consistent size and structure. They don't have a nucleoid. They are also called “immature” or vegetative particles. They are not infectious.

ET chlamydia have infectious properties, antigenoactive, capable of penetrating into a sensitive cell, where a unique cycle of chlamydia development occurs. Preceding Chlamydia ET, larger RTs do not have a consistent size and structure. They don't have a nucleoid. They are also called “immature” or vegetative particles. They are not infectious.

Chlamydia reproduce only inside membrane-bound vacuoles in the cytoplasm of human, mammalian and avian cells. Reproduction occurs during a unique developmental cycle consisting in the transformation of small forms of ETs into larger RTs that undergo division. Chlamydia are pathogenic. They have the main features of bacteria: they contain two types of nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) and ribosomes. The cell wall of chlamydia does not contain muramic acid or contains it in trace amounts.

The development of molecular biology has led to the discovery of new microorganisms with a developmental cycle characteristic of chlamydia. Determination of the genome of already known species of chlamydia contributed to the revision of their nomenclature.

According to modern approaches of gene systematics for describing bacterial taxa at the level of species, genera and families, the classification of chlamydia and chlamydia-like microorganisms is based on the presence of >95% homology in the nucleotide sequence of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes for all members of the genus and >90% for the family . Thus, previously unclassified microorganisms with a development cycle similar to chlamydia were isolated into four additional families within the Chlamydiales order - Chlamydiaceae, Parachlamydiaceae, Simkaniaceae, Waddliaceae. The question as to whether the order of Chlamydiales should be considered as a class is currently open. This is due to the small number of Chlamydia species that are included in the Chlamydiales order.

The most radical changes have taken place in the taxonomy of the family Chlamydiaceae, which currently has two genera, Chlamydia and Chlamydophila. They also differ from each other in a number of phenotypic traits.

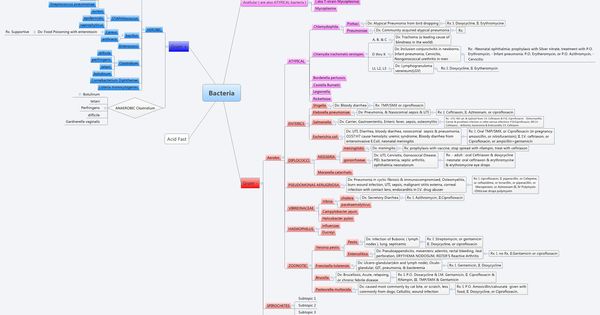

Representatives of the genus Chlamydia have extrachromosomal elements similar in structure. They are able to accumulate glycogen in inclusions. Once in the cell of the host organism, their EBs tend to merge into one common large inclusion, the biological meaning of which is the exchange of genetic information, and this, in turn, causes a large genetic variability of the pathogen. The genus Chlamydia includes three species: the long-known Chlamydia trachomatis and two new species, Chlamydia muridarum and Chlamydia suis. According to the new classification, Chlamydia trachomatis is an exclusively human parasite that causes trachoma, urogenital diseases, some forms of arthritis, conjunctivitis and neonatal pneumonia. Chlamydia trachomatis has two biovars: trachoma (14 serovars) and LGV (4 serovars).

The species Chlamydia muridarum has until recently been regarded as the third biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis. Chlamydia muridarum causes disease in rodents from the Muridae family.

Chlamydia suis was first isolated from the pig (Sus scrofa). Various strains of Chlamydia suis are capable of causing conjunctivitis, enteritis, and pneumonia in animals.

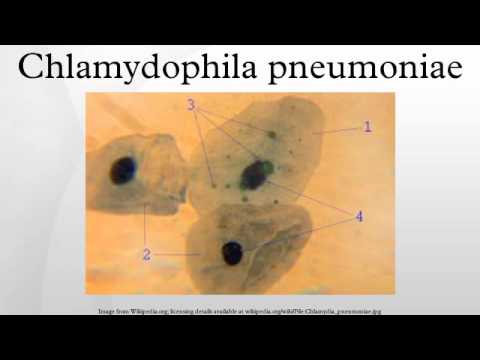

Representatives of the genus Chlamydophila show evolutionary affinity in the structure of various genes, including genes for the ribosomal operon and outer membrane proteins (OMR and OMP 2). The genus Chlamydophila includes long-known species - Chlamydophila psittaci, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pecorum, Chlamydophila abortus, Chlamydophila caviae and Chlamydophila felis.

Chlamydophila pecorum (formerly Chlamydia pecorum) is an animal pathogen.

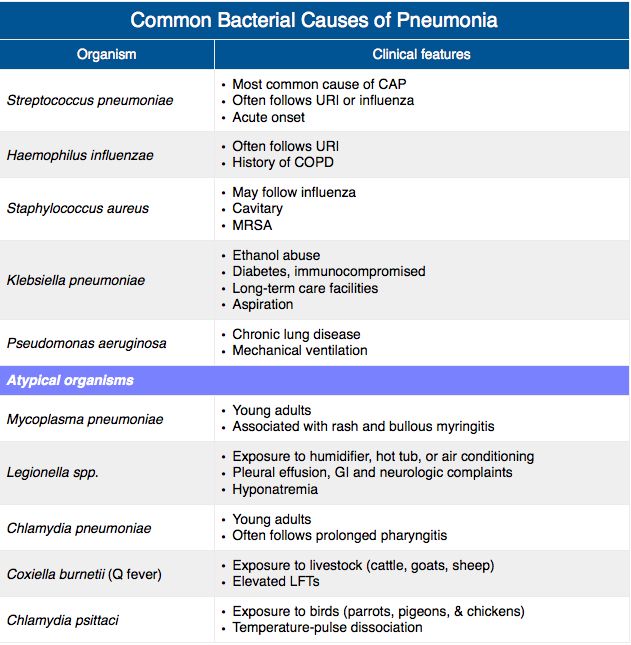

Chlamydophila pneumoniae (formerly Chlamydia pneumoniae) is the causative agent of respiratory infections in animals and humans. This species has three TWAR biovars, the koala (Koala) and the equine (Equine). Regardless of whether strains of Chlamydophila pneumoniae parasitize in animals or humans, they all have similar genetic and antigenic characteristics. TWAR strains are causative agents of respiratory tract diseases in humans. They are capable of causing predominantly acute or chronic bronchitis and pneumonia. Recently, more and more data has been accumulating, indicating a possible relationship between Chlamydophila pneumoniae and the development of atherosclerosis and bronchial asthma.

TWAR strains are causative agents of respiratory tract diseases in humans. They are capable of causing predominantly acute or chronic bronchitis and pneumonia. Recently, more and more data has been accumulating, indicating a possible relationship between Chlamydophila pneumoniae and the development of atherosclerosis and bronchial asthma.

Chlamydophila psittaci (former name Chlamydia psittaci) until recently included 4 groups of pathogens that differed significantly both genetically and phenotypically and caused diseases in humans and animals. According to the new classification, Chlamydophila psittaci includes strains that can only cause disease in birds. All of these strains can be transmitted to humans and cause psittacosis. The species Chlamydophila psittaci includes 8 serovars.

Chlamydophila abortus cause disease in animals. The literature describes cases of sporadic abortions in women working with sheep, caused by Chlamydophila abortus - gestational psittacosis.

Chlamydophila felis causes rhinitis and conjunctivitis in domestic cats. Zoonotic infections caused by this microorganism in humans have been reported and manifested as conjunctivitis.

Chlamydophila caviae was first isolated from guinea pig conjunctiva. It has been shown in laboratory conditions that this microorganism can cause genital infections in guinea pigs that are similar in their manifestations to analogous diseases in humans.

Representatives of the Parachlamydiaceae family grow well on Vero cell culture, stain variably by Gram, are not recognized by monoclonal antibodies specific for the LPS antigen complex of the Chlamydiaceae family, and are parasites of amoebae. Differences in the nucleotide sequence of the genes of Parachlamydiaceae and Chlamydiaceae in general is 10-20%. The family includes one genus, the only representative of which is Parachlamydia acanhamoebae.

Currently, the family Simkaniaceae includes one genus Simkama, which is represented by a single species and strain, Simkania negevensis. The natural host of Simcanii is still unknown. However, data from serological research methods and PCR analysis indicate that this microorganism is widely distributed in humans. Simkania negevensis is not recognized by monoclonal antibodies specific for the LPS antigen complex of the Chlamydiaceae family.

The natural host of Simcanii is still unknown. However, data from serological research methods and PCR analysis indicate that this microorganism is widely distributed in humans. Simkania negevensis is not recognized by monoclonal antibodies specific for the LPS antigen complex of the Chlamydiaceae family.

Waddlia chondrophila (strain WSU 86-1044) is the only member of the Waddliaceae family. The nucleotide sequence of the 16S rDNA of strain WSU 86-1044 shows 84.7-85.3% homology with the corresponding representatives of the genes of various chlamydial strains.

Fundamental changes made to the classification of members of the order Chlamydiales should be taken into account in the first place in the diagnosis of chlamydial infection. This is due to the fact that all species belonging to the Chlamydiaceae family have a similar lipopolysaccharide antigen structure and are recognized by monoclonal antibodies specific to the alphaKdo-(2-8)-alphaKdo-(2-4)-alphaKdo LPS trisaccharide fragment. In this regard, many of them in the PIF and serological methods are identified as Chlamydia trachomatis.

In this regard, many of them in the PIF and serological methods are identified as Chlamydia trachomatis.

The major protein antigens displayed on the surface of EBs, including the 40 kDa cysteine-saturated protein (MOMP or OMP) and the 60-kDa cysteine-saturated protein (OMP 2), also show significant structural similarity across different species of the Chlamydiaceae family. Therefore, in methods based on the recognition of these antigens, as in the case of LPS antigens, all species of the Chlamydiaceae family are identified as Chlamydia trachomatis.

Based on the fact that the species of the Chlamydiaceae family differ from each other only by differences in the nucleotide sequence of some genes (namely, 16S and 23S rRNA), on which, in fact, the taxonomy is based, it becomes obvious that the correct diagnosis of the causative agent of chlamydial infection is possible only when using methods based on the detection of the pathogen genome.

Since different types of chlamydia have different development cycles and different sensitivities to conventional chlamydial drugs, misdiagnosis of the chlamydial pathogen can lead to problems in the treatment of chlamydia.

Despite the fact that the life cycle of chlamydia is well covered in the literature, the mechanisms of regulation of the intracellular development of chlamydia are still unknown. Many researchers believe that in addition to the unique development cycle, chlamydia differ from other pathogens in that they have the ability to persist and form atypical forms. In the process of reproduction of chlamydia, an asynchronous development of infection is observed - the simultaneous presence of all stages of the reproduction cycle of chlamydia.

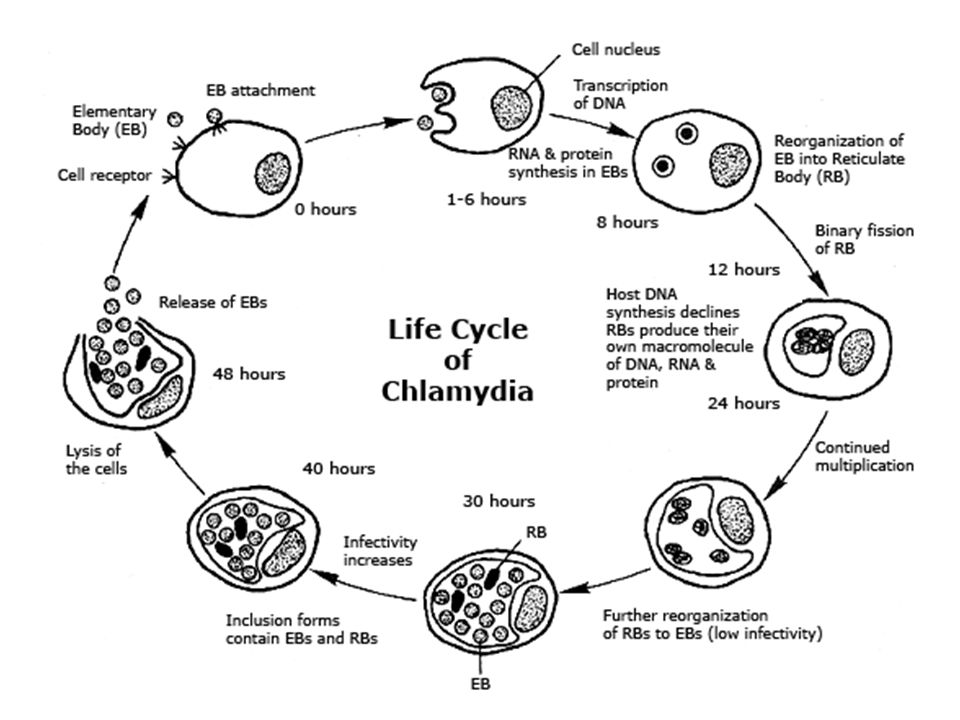

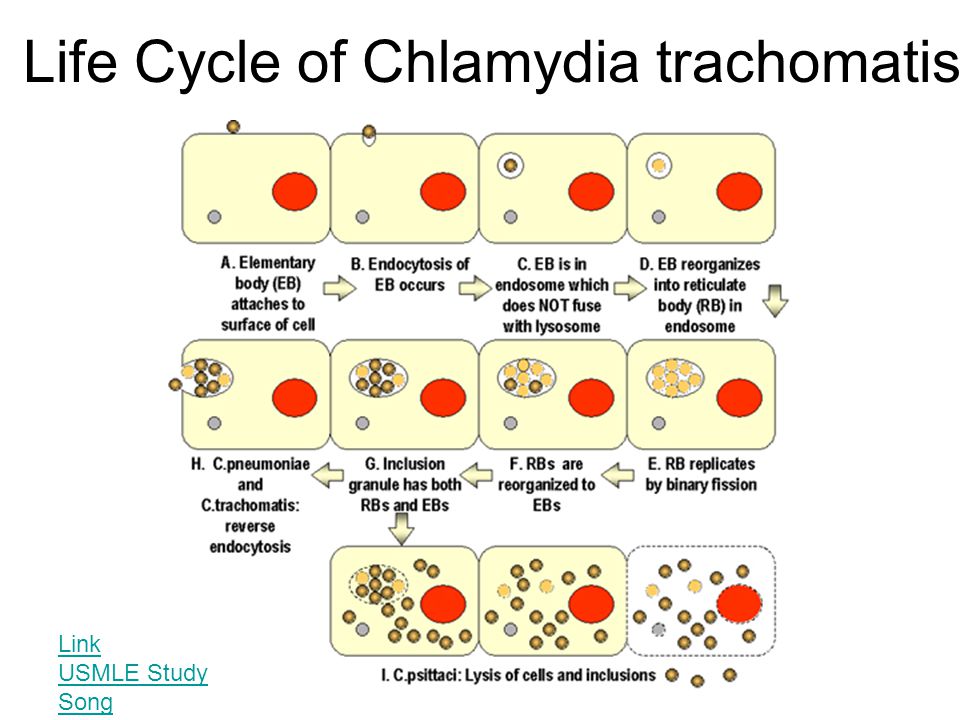

The development cycle of chlamydia can be conditionally divided into several stages.

1. Elemental body adsorption; 2. Penetration of the elementary body into the cell; 3. Reorganization of the elementary body into the reticular body; 4. Division of the reticular body; 5. Maturation of reticular bodies into elementary ones; 6. Accumulation of reticular bodies in the endosome; 7. Release of chlamydia from the cell.

At the first stage of the infectious process, ET of chlamydia is adsorbed on the plasma membrane of a sensitive host cell with the participation of electrostatic forces. The introduction of chlamydia into the cell occurs by endocytosis. Plasmalemma regions with ET adsorbed on them invaginate into the cytoplasm with the formation of phagocytic vacuoles. This stage takes 7-10 hours.

The introduction of chlamydia into the cell occurs by endocytosis. Plasmalemma regions with ET adsorbed on them invaginate into the cytoplasm with the formation of phagocytic vacuoles. This stage takes 7-10 hours.

Further, at the second stage, within 6-8 hours, infectious EBs are reorganized into metabolically active non-infectious, vegetative, intracellular forms - RT, capable of growth and division. These intracellular forms, which are microcolonies, are called chlamydial inclusions - Halberstedter-Prowachek bodies. Within 18-24 hours of development, they are localized in the cytoplasmic vesicle formed from the membrane of the host cell. An inclusion may contain from 100 to 500 ET of chlamydia.

At the next stage, within 36-42 hours, the process of maturation takes place, through transitional (intermediate bodies), and transformation of RT by division into ET. EBs exit the infected cell by destroying it. This ends the life cycle of chlamydia. The released EBs, which are extracellular, in 48-72 hours again penetrate into new host cells, and a new cycle of chlamydia development begins. In the event of unfavorable metabolic conditions, this process can be delayed for a longer period.

In the event of unfavorable metabolic conditions, this process can be delayed for a longer period.

In the case of an asymptomatic chlamydial infection, ET is released from the infected cell through a narrow rim of the cytoplasm. In this case, the cell can maintain its viability.

The protective reaction of the host organism at the initial stage of infection is carried out with the participation of polymorphonuclear lymphocytes. Polyclonal activation of B-lymphocytes plays a significant role in the protection of the body. In the blood serum and secretory fluids in chlamydia, immunoglobulins of the classes IgM, IgA, IgG are found. However, T-helpers, which activate the phagocytic activity of macrophages, still play the leading role in protection against chlamydial infection.

The use of ultrastructural analysis methods made it possible to prove the possibility of chlamydia persistence in epithelial cells and fibroblasts infected with mucous membranes. Chlamydia are taken up by peripheral monocytes and thus spread throughout the body. Monocytes settle in tissues and turn into tissue macrophages (in the joints, blood vessels and in the region of the heart). Tissue macrophages can remain viable for several months. Being at the same time an antigenic stimulator, they contribute to the formation of fibrous granulomas in healthy tissue. Chlamydia or their fragments can be released from cells and cause the formation of specific antibodies, regardless of whether the chlamydial antigen is detected at the site of infection.

Monocytes settle in tissues and turn into tissue macrophages (in the joints, blood vessels and in the region of the heart). Tissue macrophages can remain viable for several months. Being at the same time an antigenic stimulator, they contribute to the formation of fibrous granulomas in healthy tissue. Chlamydia or their fragments can be released from cells and cause the formation of specific antibodies, regardless of whether the chlamydial antigen is detected at the site of infection.

The structure of the cell wall of chlamydia corresponds to the general principle of construction of gram-negative bacteria.

Chlamydia cell wall consists of inner cytoplasmic and outer membranes, each of which has a double structure. This ensures the strength of the chlamydia cell wall. The antigenic properties of chlamydia are determined by the inner membrane, which is represented by lipopolysaccharides. The so-called outer membrane proteins (OMP) are integrated into it. The main protein of the outer membrane - Major Outer Membrane Protein (MOMP) accounts for 60% of the total protein. The rest of the antigenic structure is represented by proteins of the outer membrane of the second type - OMP 2.

The rest of the antigenic structure is represented by proteins of the outer membrane of the second type - OMP 2.

All chlamydia have a common group, genus-specific antigen (lipopolysaccharide complex, the reactive half of which is 2-keto-3-deoxyoctanoic acid), which is used in the diagnosis of the disease by immunofluorescent methods using specific antibodies (Table 1).

Table 1 Chlamydia antigens (P.A. Mardh, 1990)

| Antigen | Composition | Note |

| Genus-specific (common for all types of chlamydia: Chlamydiapsittaci, Chlamydiatrachomatis, Chlamydiapneumoniae) | Liposaccharide | Three different antigenic domains |

| Species-specific (different for all types of chlamydia: Chlamydia psittaci, Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae) | Proteins | More than 18 different components of 155 kDa in Chlamydia trachomatis, epitopes in 40 kDa protein, hsp-60 heat shock protein |

| Type specific (different for Chlamydiatrachomatis serovars) | Proteins | Epitopes in 40 kDa protein (MOMP), 30 kD protein serotypes A and B |

MOMP and OMP 2 proteins contain species- and serotype-specific epitopes. However, they also contain regions with high similarity among species (genus-specific epitopes), which makes it possible for cross-reactions to occur. The basic cell membrane protein and other cysteine-rich proteins are linked by disulfide bonds.

However, they also contain regions with high similarity among species (genus-specific epitopes), which makes it possible for cross-reactions to occur. The basic cell membrane protein and other cysteine-rich proteins are linked by disulfide bonds.

Five genes of disulfide-linked isomerases have been found that may play a role in the restructuring of cysteine-rich proteins during ET differentiation in RT. In Chlamydia trachomatis, 9 genes encoding surface membrane proteins have been identified, in Chlamydia pneumonia – 18.

In 1998 R.S. Stephens et al reported the sequencing of the Chlamydia trachomatis genome. The genome of chlamydia is small and makes up no more than 22% of the genome of Escherichia coli strain K12.

Genome analysis made it possible to isolate 895 genes that code for various proteins. The similarity with previously studied proteins of other bacteria helped to determine the functional purpose of 604 (68%) encoded proteins. Thus, 35 (4%) proteins were similar to proteins found in other bacteria. In the remaining 255 (28%) proteins, the sequences were different from those previously studied. Their analysis showed that 256 (29%) chlamydial proteins within one genome are grouped into 58 families. A similar grouping of proteins occurs in bacteria that have a small genome, such as mycoplasmas and Haemophilus influenzae.

In the remaining 255 (28%) proteins, the sequences were different from those previously studied. Their analysis showed that 256 (29%) chlamydial proteins within one genome are grouped into 58 families. A similar grouping of proteins occurs in bacteria that have a small genome, such as mycoplasmas and Haemophilus influenzae.

For a long time it was believed that chlamydia have a characteristic defect in a number of enzyme systems and are not able to independently oxidize glutamine and pyruvate, as well as to carry out phosphorylation and efficient oxidation of glucose. It was also assumed that chlamydia are obligate intracellular energy parasites that use the metabolic energy of the eukaryotic cell with the help of ATP and other macroergic compounds. It is now known that chlamydia are able to synthesize ATP, albeit in small quantities, through glycolysis and the breakdown of glycogen.

In the process of adapting to intracellular parasitism, Chlamydia have developed unique structures and biosynthetic mechanisms that have no analogues in other bacteria. They failed to detect the highly conserved FtsZ gene, which is responsible for the formation of a cell septa during cell division and is absolutely essential for the cell division of all prokaryotes. Chlamydia also lack peptidoglycan, a cell wall component found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. But at the same time, the chlamydia genome contains genes encoding proteins that are necessary for its complete synthesis.

They failed to detect the highly conserved FtsZ gene, which is responsible for the formation of a cell septa during cell division and is absolutely essential for the cell division of all prokaryotes. Chlamydia also lack peptidoglycan, a cell wall component found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. But at the same time, the chlamydia genome contains genes encoding proteins that are necessary for its complete synthesis.

Previously, scanning electron microscopy on the surface of chlamydia revealed dome-shaped structures penetrated by microfilaments. Microfilaments leave the center, reach the inclusion membrane and penetrate it. The function of this structure is associated with the transport of nutrients from the eukaryotic cell to the parasite. The discovery in the chlamydia genome of the genes encoding the apparatus for the 3rd type of secretion, which determines the virulence of gram-negative bacteria, suggested that this formation transmits a signal from the parasite to the eukaryotic cell.