What is cultural aspect

Understanding and Changing the Social World

Skip to content

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish material culture and nonmaterial culture.

- List and define the several elements of culture.

- Describe certain values that distinguish the United States from other nations.

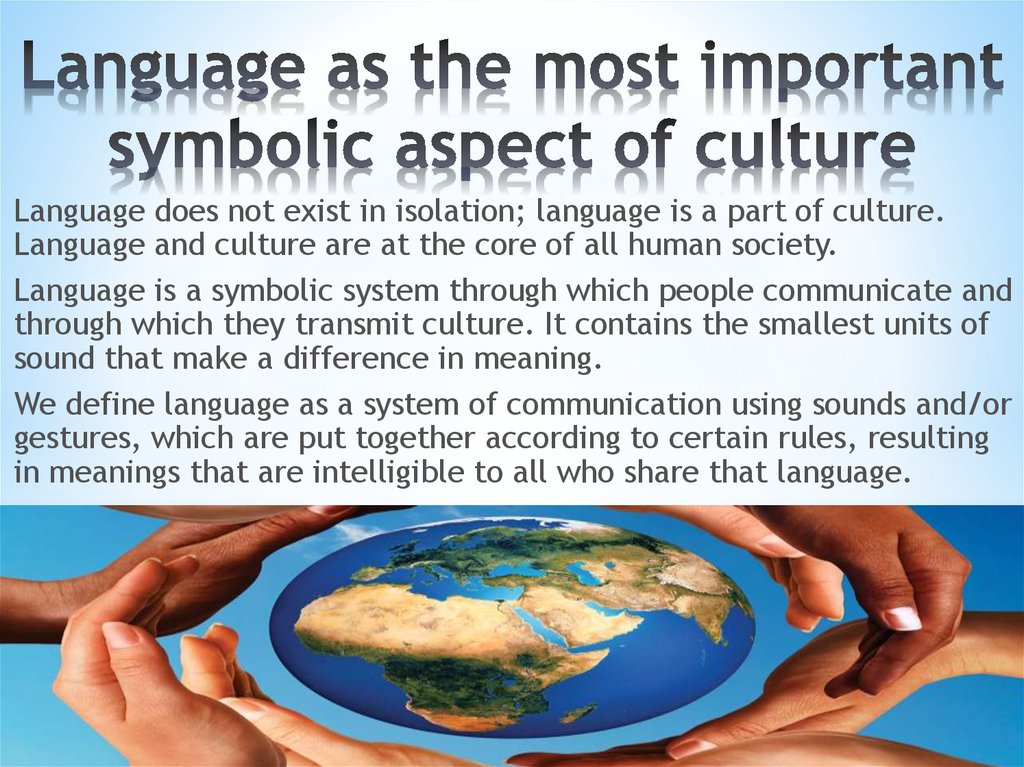

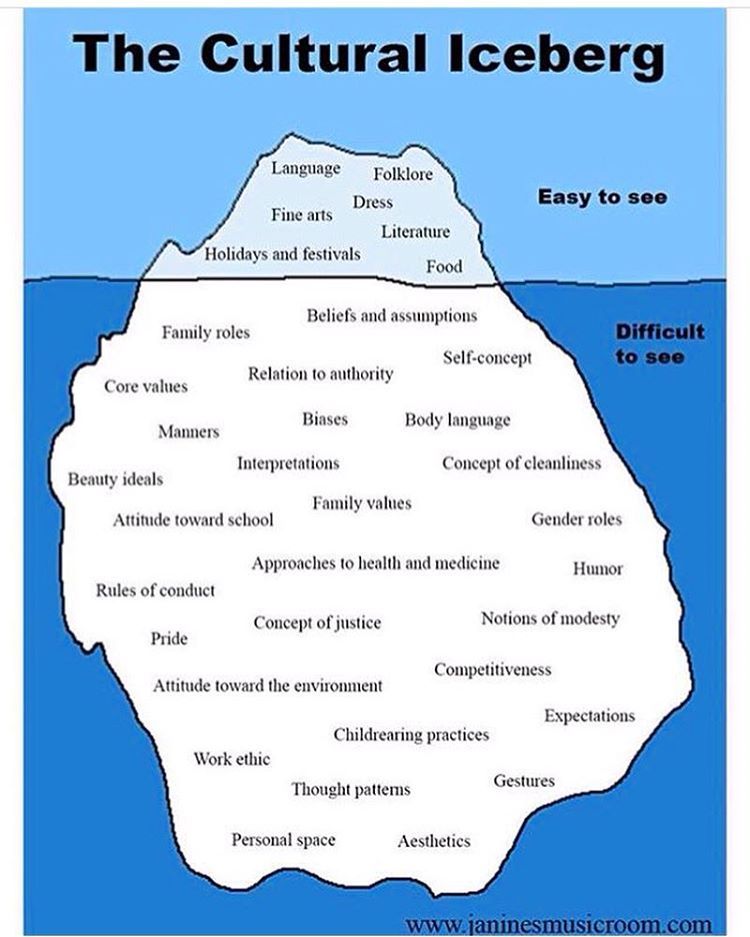

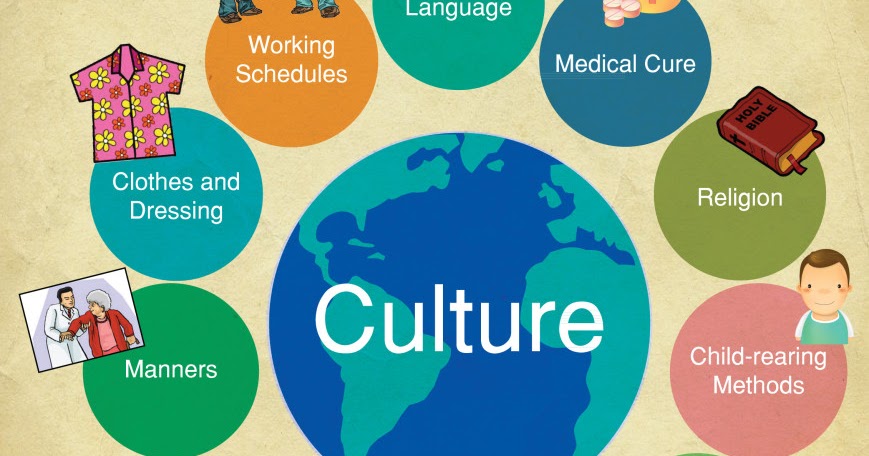

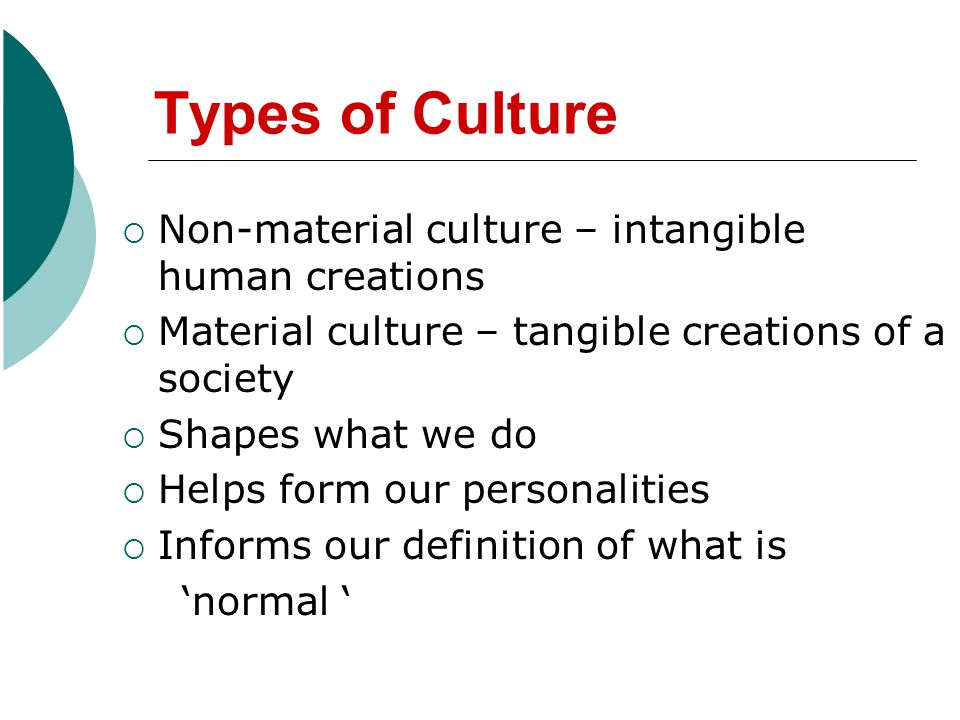

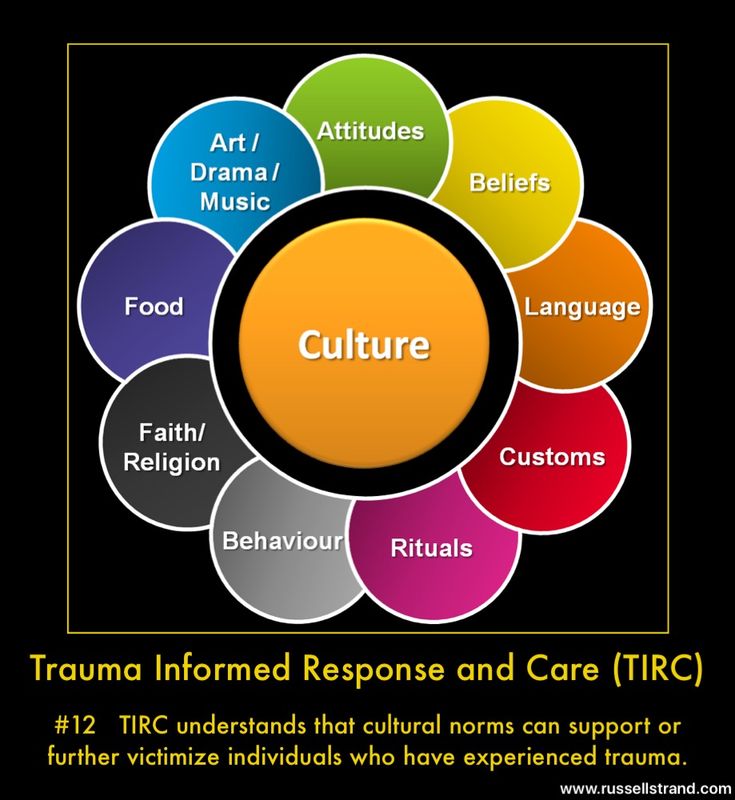

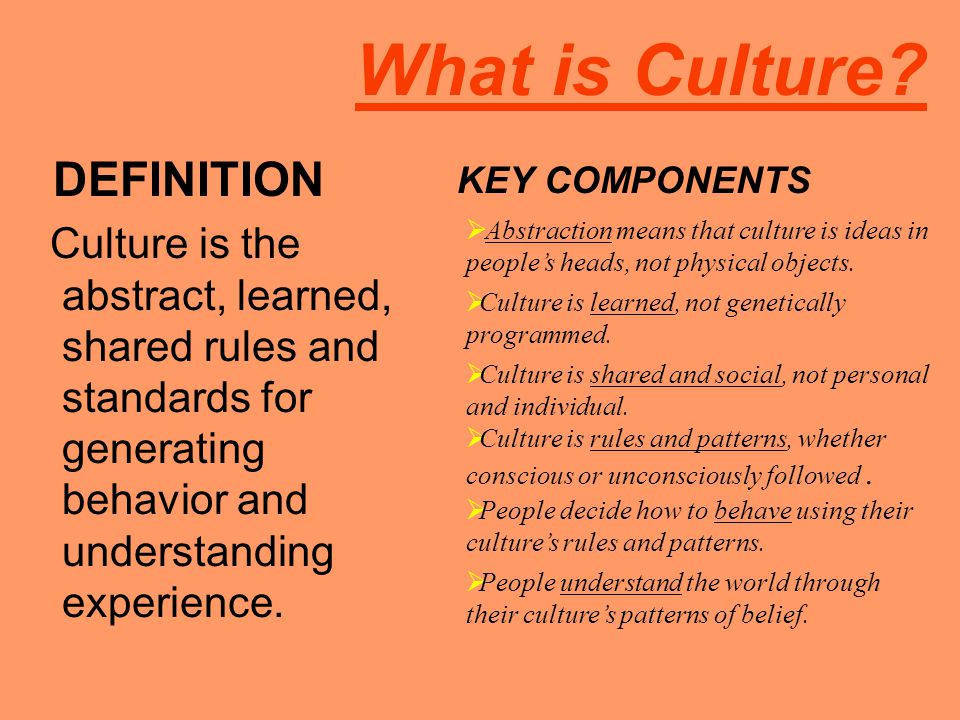

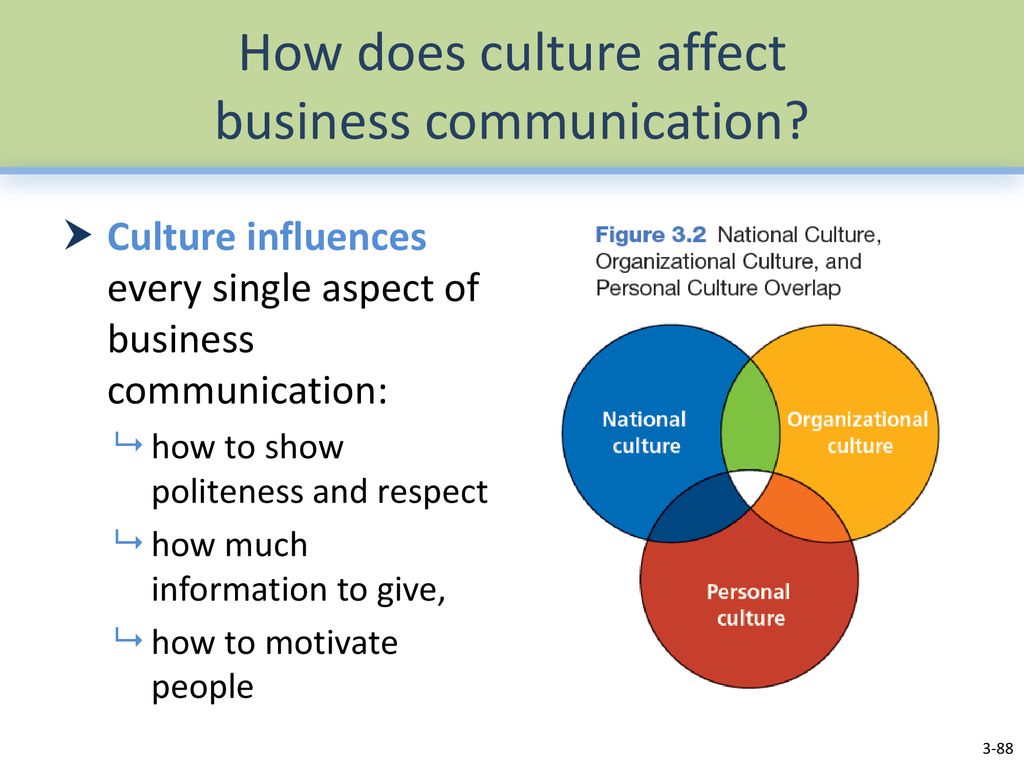

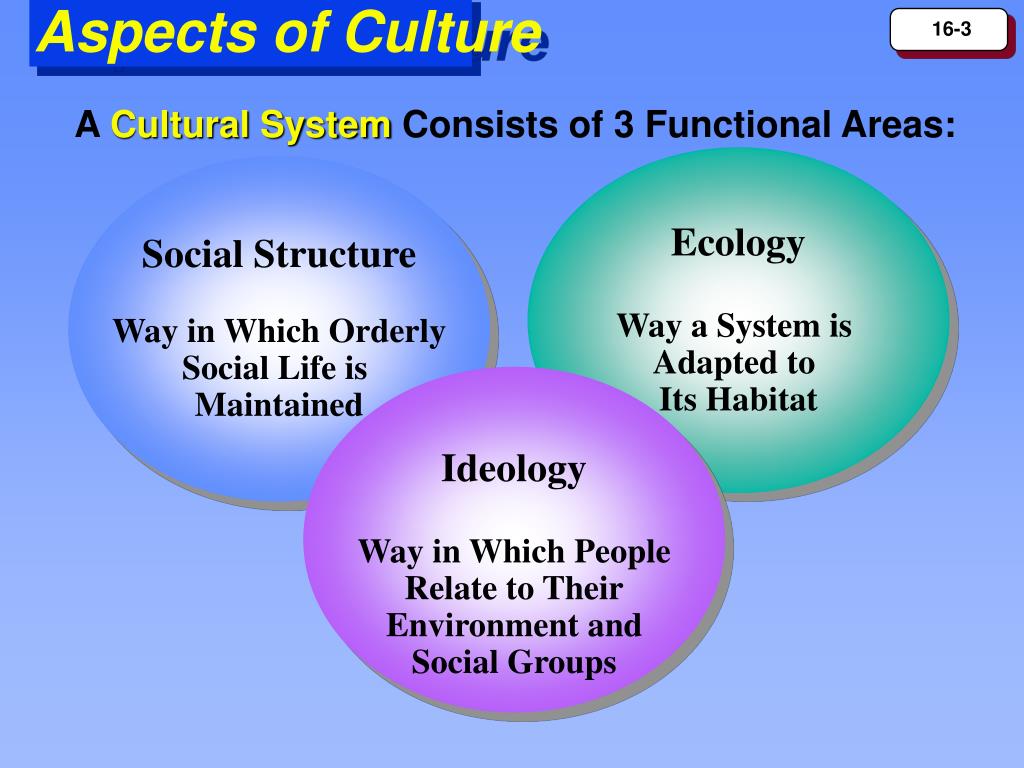

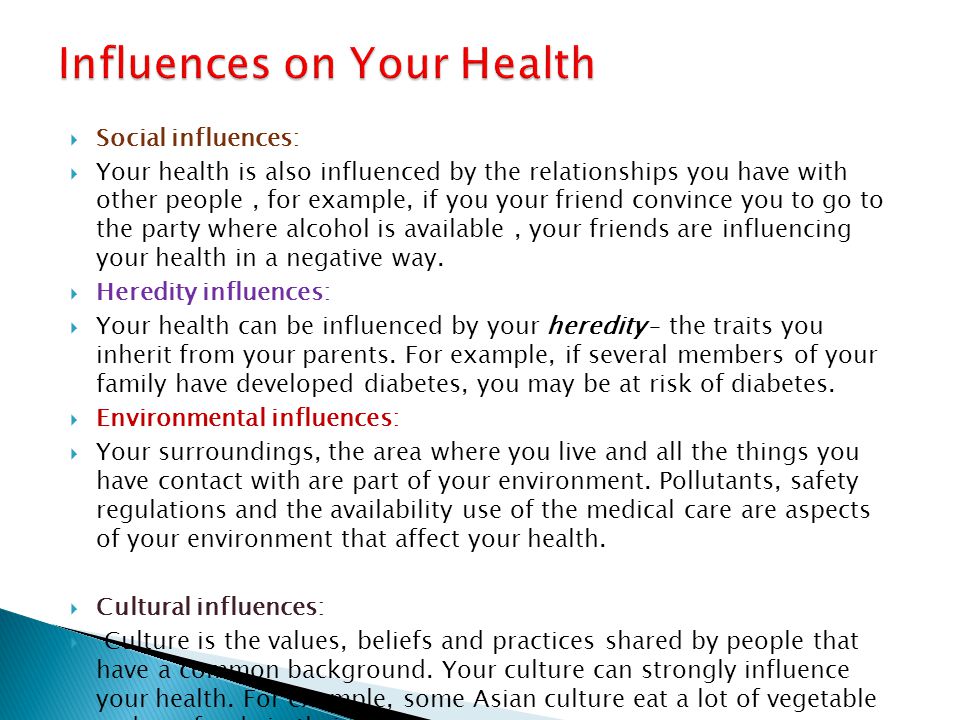

Culture was defined earlier as the symbols, language, beliefs, values, and artifacts that are part of any society. As this definition suggests, there are two basic components of culture: ideas and symbols on the one hand and artifacts (material objects) on the other. The first type, called nonmaterial culture also known as symbolic culture, includes the values, beliefs, symbols, and language that define a society. The second type, called material culture, includes all the society’s physical objects, such as its tools and technology, clothing, eating utensils, and means of transportation. These elements of culture are discussed next.

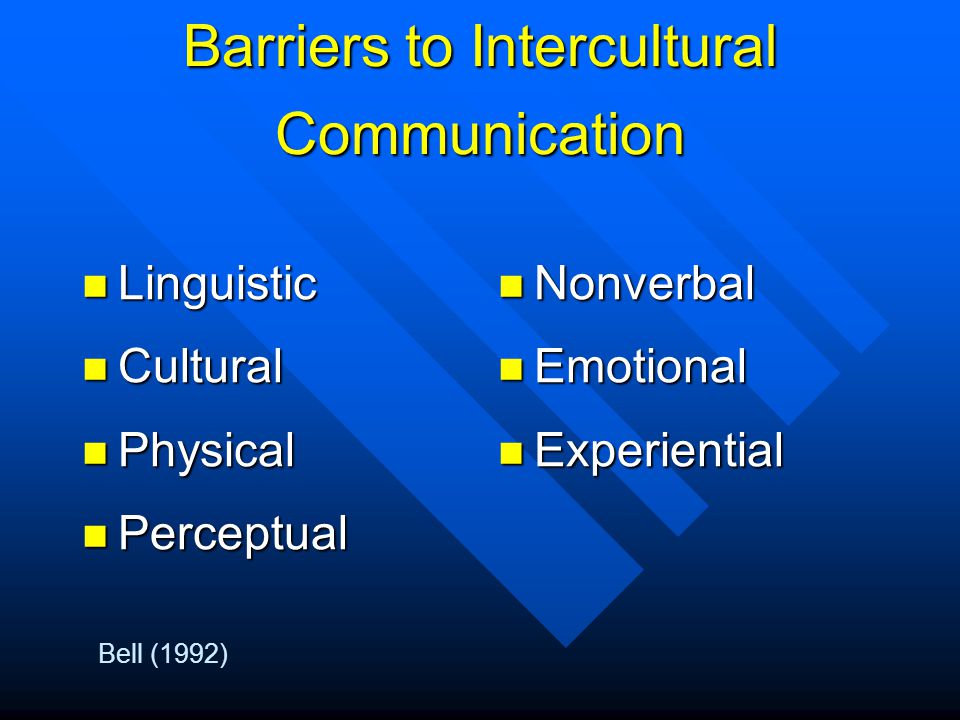

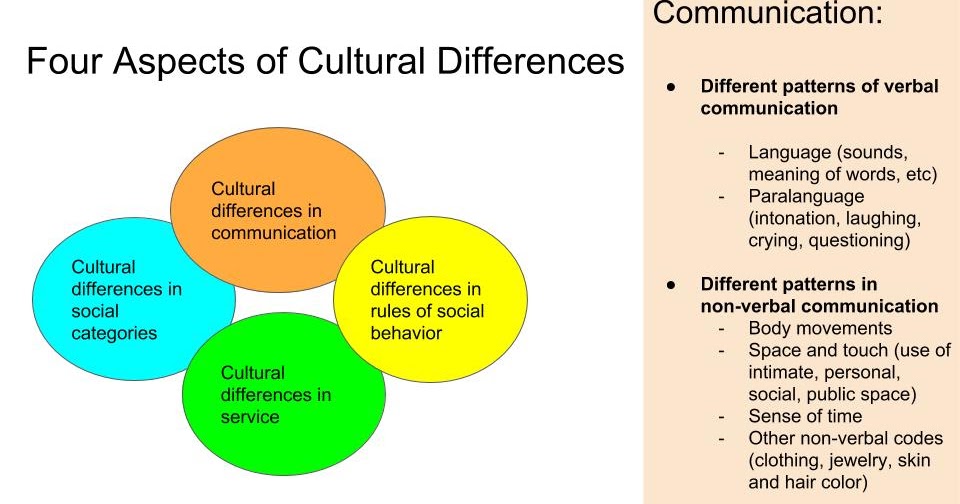

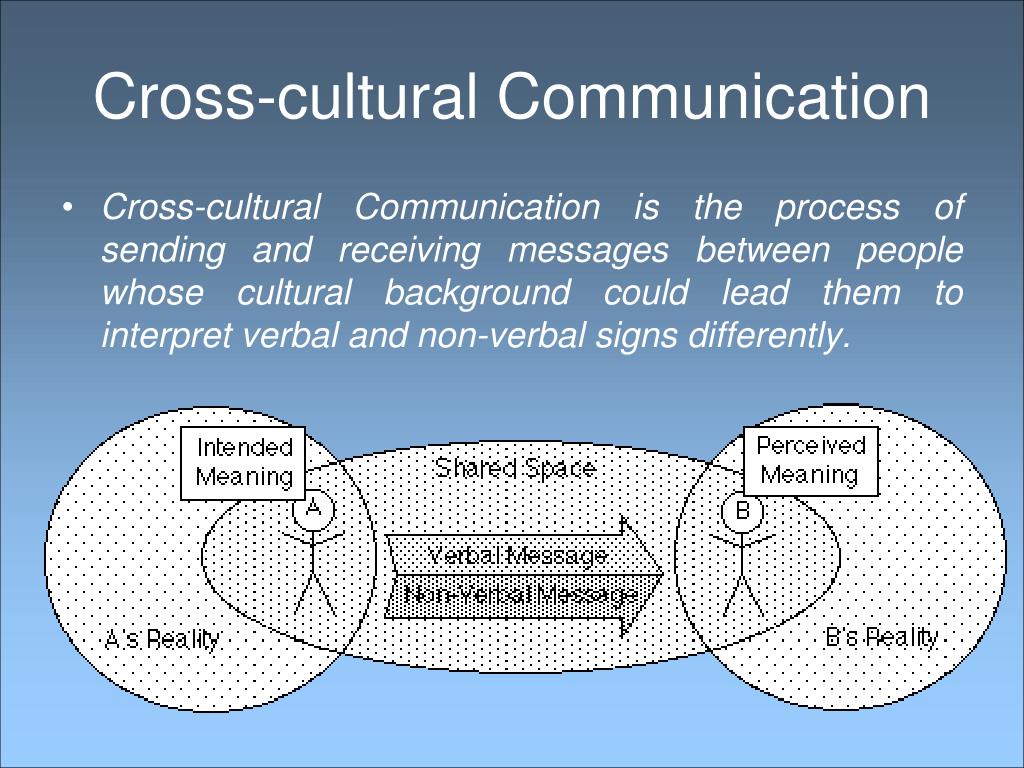

Symbols

Every culture is filled with symbols, or things that stand for something else and that often evoke various reactions and emotions. Some symbols are actually types of nonverbal communication, while other symbols are in fact material objects. As the symbolic interactionist perspective discussed in Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” (Links to an external site.) emphasizes, shared symbols make social interaction possible.

Let’s look at nonverbal symbols first. A common one is shaking hands, which is done in some societies but not in others. It commonly conveys friendship and is used as a sign of both greeting and departure. Probably all societies have nonverbal symbols we call gestures, movements of the hands, arms, or other parts of the body that are meant to convey certain ideas or emotions. However, the same gesture can mean one thing in one society and something quite different in another society (Axtell, 1998). In the United States, for example, if we nod our head up and down, we mean yes, and if we shake it back and forth, we mean no. In Bulgaria, however, nodding means no, while shaking our head back and forth means yes! In the United States, if we make an “O” by putting our thumb and forefinger together, we mean “OK,” but the same gesture in certain parts of Europe signifies an obscenity. “Thumbs up” in the United States means “great” or “wonderful,” but in Australia it means the same thing as extending the middle finger in the United States. Certain parts of the Middle East and Asia would be offended if they saw you using your left hand to eat, because they use their left hand for bathroom hygiene.

In the United States, for example, if we nod our head up and down, we mean yes, and if we shake it back and forth, we mean no. In Bulgaria, however, nodding means no, while shaking our head back and forth means yes! In the United States, if we make an “O” by putting our thumb and forefinger together, we mean “OK,” but the same gesture in certain parts of Europe signifies an obscenity. “Thumbs up” in the United States means “great” or “wonderful,” but in Australia it means the same thing as extending the middle finger in the United States. Certain parts of the Middle East and Asia would be offended if they saw you using your left hand to eat, because they use their left hand for bathroom hygiene.

Some of our most important symbols are objects. Here the U.S. flag is a prime example. For most Americans, the flag is not just a piece of cloth with red and white stripes and white stars against a field of blue. Instead, it is a symbol of freedom, democracy, and other American values and, accordingly, inspires pride and patriotism. During the Vietnam War, however, the flag became to many Americans a symbol of war and imperialism. Some burned the flag in protest, prompting angry attacks by bystanders and negative coverage by the news media.

During the Vietnam War, however, the flag became to many Americans a symbol of war and imperialism. Some burned the flag in protest, prompting angry attacks by bystanders and negative coverage by the news media.

As these examples indicate, shared symbols, both nonverbal communication and tangible objects, are an important part of any culture but also can lead to misunderstandings and even hostility. These problems underscore the significance of symbols for social interaction and meaning.

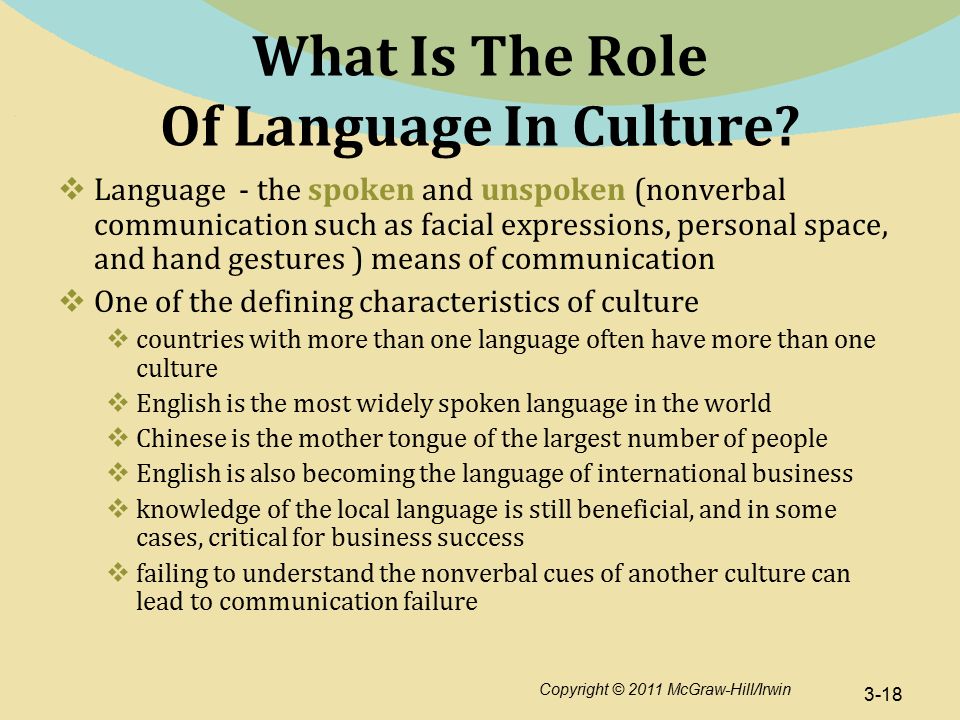

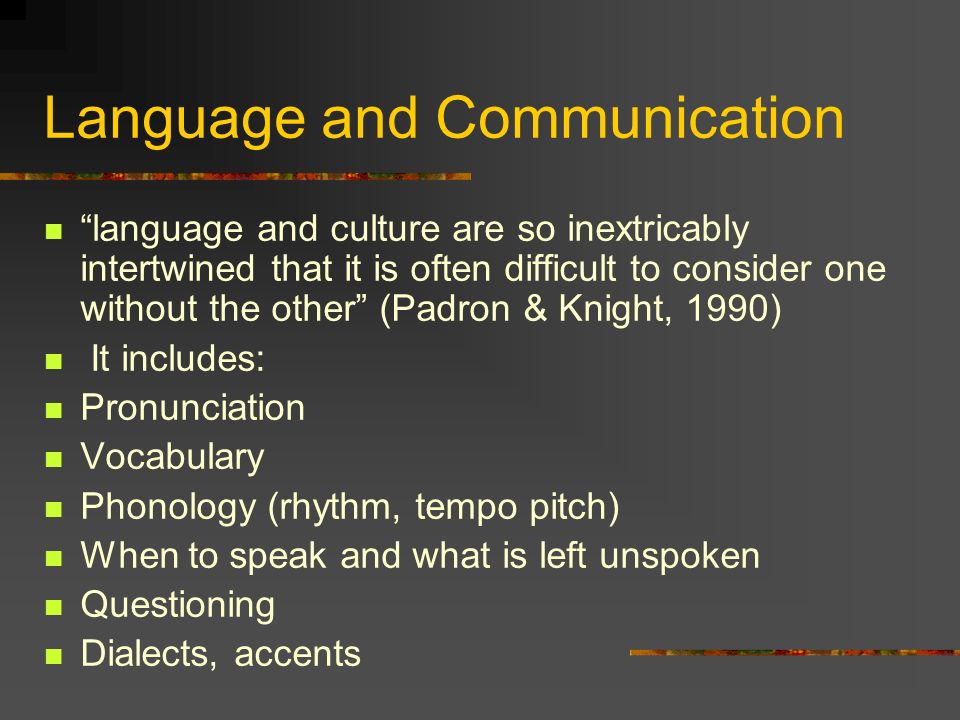

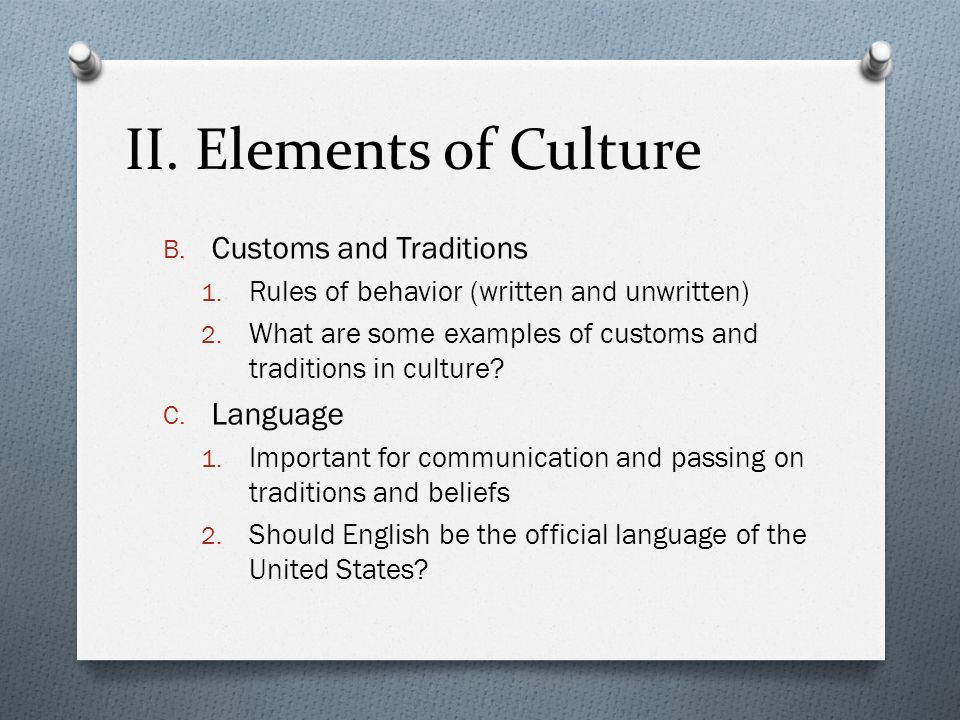

Language

Perhaps our most important set of symbols is language. In English, the word chair means something we sit on. In Spanish, the word silla means the same thing. As long as we agree how to interpret these words, a shared language and thus society are possible. By the same token, differences in languages can make it quite difficult to communicate. For example, imagine you are in a foreign country where you do not know the language and the country’s citizens do not know yours. Worse yet, you forgot to bring your dictionary that translates their language into yours, and vice versa, and your iPhone battery has died. You become lost. How will you get help? What will you do? Is there any way to communicate your plight?

Worse yet, you forgot to bring your dictionary that translates their language into yours, and vice versa, and your iPhone battery has died. You become lost. How will you get help? What will you do? Is there any way to communicate your plight?

As this scenario suggests, language is crucial to communication and thus to any society’s culture. Children learn language from their culture just as they learn about shaking hands, about gestures, and about the significance of the flag and other symbols. Humans have a capacity for language that no other animal species possesses. Our capacity for language in turn helps make our complex culture possible.

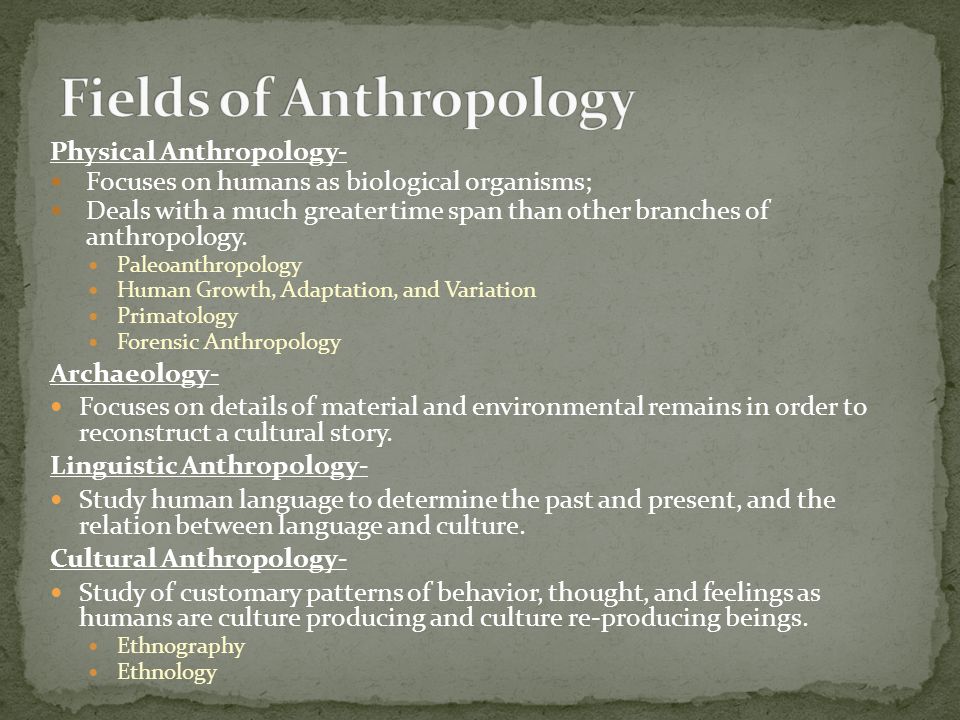

To what extent does language influence how we think and how we perceive the social and physical worlds? The famous but controversial Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, named after two linguistic anthropologists, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, argues that people cannot easily understand concepts and objects unless their language contains words for these items (Whorf, 1956). They explained that language structures thought. Language thus influences how we understand the world around us. For example, people in a country such as the United States that has many terms for different types of kisses (e.g. buss, peck, smack, smooch, and soul) are better able to appreciate these different types than people in a country such as Japan, which, as we saw earlier, only fairly recently developed the word kissu for kiss.

They explained that language structures thought. Language thus influences how we understand the world around us. For example, people in a country such as the United States that has many terms for different types of kisses (e.g. buss, peck, smack, smooch, and soul) are better able to appreciate these different types than people in a country such as Japan, which, as we saw earlier, only fairly recently developed the word kissu for kiss.

Another illustration of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is seen in sexist language, in which the use of male nouns and pronouns shapes how we think about the world (Miles, 2008). In older children’s books, words like fireman and mailman are common, along with pictures of men in these jobs, and critics say they send a message to children that these are male jobs, not female jobs. If a teacher tells a second-grade class, “Every student should put his books under his desk,” the teacher obviously means students of both sexes but may be sending a subtle message that boys matter more than girls. For these reasons, several guidebooks promote the use of nonsexist language (Maggio, 1998). Table 3.1 “Examples of Sexist Terms and Nonsexist Alternatives” (Links to an external site.) provides examples of sexist language and nonsexist alternatives.

For these reasons, several guidebooks promote the use of nonsexist language (Maggio, 1998). Table 3.1 “Examples of Sexist Terms and Nonsexist Alternatives” (Links to an external site.) provides examples of sexist language and nonsexist alternatives.

Table 3.1 Examples of Sexist Terms and Nonsexist Alternatives

| Term | Alternative |

|---|---|

| Businessman | Businessperson, executive |

| Fireman | Fire fighter |

| Chairman | Chair, chairperson |

| Policeman | Police officer |

| Mailman | Letter carrier, postal worker |

| Mankind | Humankind, people |

| Man-made | Artificial, synthetic |

| Waitress | Server |

| He (as generic pronoun) | He or she; he/she; s/he |

| “A professor should be devoted to his students” | “Professors should be devoted to their students” |

Norms

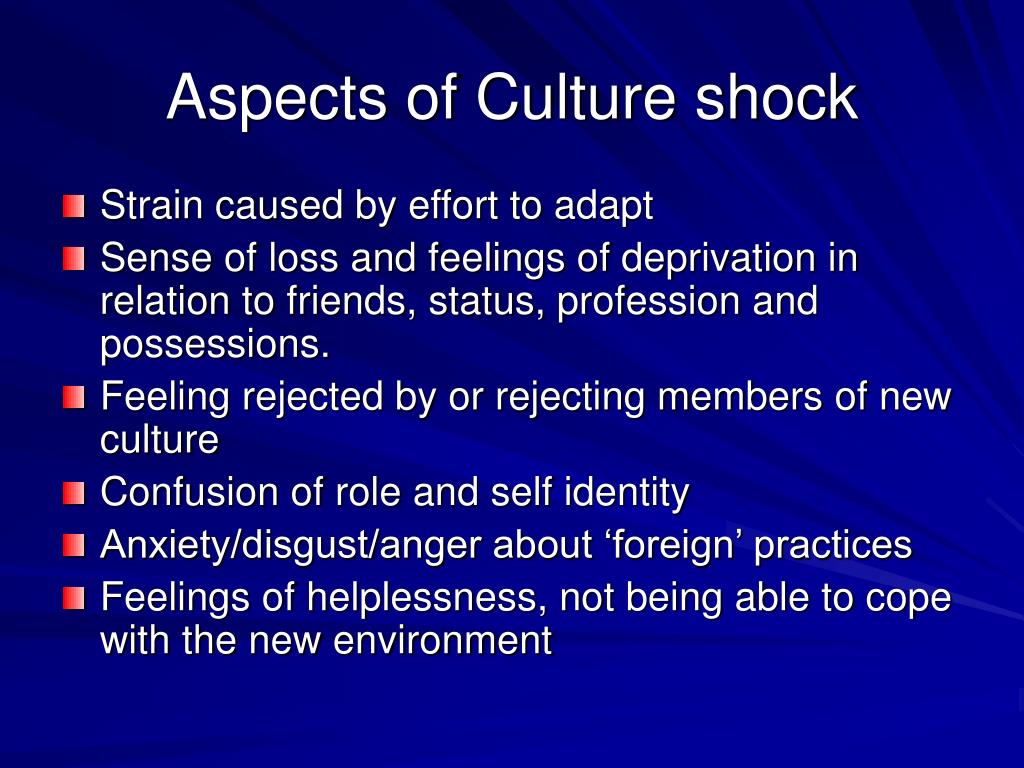

Cultures differ widely in their norms, or standards and expectations for behaving. We already saw that the nature of drunken behavior depends on society’s expectations of how people should behave when drunk. Norms of drunken behavior influence how we behave when we drink too much.

•Norms are the formal and informal rules regarding what kinds of behavior are acceptable and appropriate within a culture.

•Norms are specific to a culture, time period, and situation.

Norms are often divided into two types, formal norms and informal norms. Formal norms, also called mores (MOOR-ayz) and laws, refer to the standards of behavior considered the most important in any society. Examples in the United States include traffic laws, criminal codes, and, in a college context, student behavior codes addressing such things as cheating and hate speech. Informal norms, also called folkways and customs,refer to standards of behavior that are considered less important but still influence how we behave. Table manners are a common example of informal norms, as are such everyday behaviors as how we interact with a cashier and how we ride in an elevator.

Informal norms, also called folkways and customs,refer to standards of behavior that are considered less important but still influence how we behave. Table manners are a common example of informal norms, as are such everyday behaviors as how we interact with a cashier and how we ride in an elevator.

Many norms differ dramatically from one culture to the next. Some of the best evidence for cultural variation in norms comes from the study of sexual behavior (Edgerton, 1976). Among the Pokot of East Africa, for example, women are expected to enjoy sex, while among the Gusii a few hundred miles away, women who enjoy sex are considered deviant. In Inis Beag, a small island off the coast of Ireland, sex is considered embarrassing and even disgusting; men feel that intercourse drains their strength, while women consider it a burden. Even nudity is considered terrible, and people on Inis Beag keep their clothes on while they bathe. The situation is quite different in Mangaia, a small island in the South Pacific. Here sex is considered very enjoyable, and it is the major subject of songs and stories.

Here sex is considered very enjoyable, and it is the major subject of songs and stories.

While many societies frown on homosexuality, others accept it. Among the Azande of East Africa, for example, young warriors live with each other and are not allowed to marry. During this time, they often have sex with younger boys, and this homosexuality is approved by their culture. Among the Sambia of New Guinea, young males live separately from females and engage in homosexual behavior for at least a decade. It is felt that the boys would be less masculine if they continued to live with their mothers and that the semen of older males helps young boys become strong and fierce (Edgerton, 1976).

Other evidence for cultural variation in norms comes from the study of how men and women are expected to behave in various societies. For example, many traditional societies are simple hunting-and-gathering societies. In most of these, men tend to hunt and women tend to gather. Many observers attribute this gender difference to at least two biological differences between the sexes. First, men tend to be bigger and stronger than women and are thus better suited for hunting. Second, women become pregnant and bear children and are less able to hunt. Yet a different pattern emerges in some hunting-and-gathering societies. Among a group of Australian aborigines called the Tiwi and a tribal society in the Philippines called the Agta, both sexes hunt. After becoming pregnant, Agta women continue to hunt for most of their pregnancy and resume hunting after their child is born (Brettell & Sargent, 2009).

First, men tend to be bigger and stronger than women and are thus better suited for hunting. Second, women become pregnant and bear children and are less able to hunt. Yet a different pattern emerges in some hunting-and-gathering societies. Among a group of Australian aborigines called the Tiwi and a tribal society in the Philippines called the Agta, both sexes hunt. After becoming pregnant, Agta women continue to hunt for most of their pregnancy and resume hunting after their child is born (Brettell & Sargent, 2009).

Rituals

Different cultures also have different rituals, or established procedures and ceremonies that often mark transitions in the life course. As such, rituals both reflect and transmit a culture’s norms and other elements from one generation to the next. Graduation ceremonies in colleges and universities are familiar examples of time-honored rituals. In many societies, rituals help signify one’s gender identity. For example, girls around the world undergo various types of initiation ceremonies to mark their transition to adulthood. Among the Bemba of Zambia, girls undergo a month-long initiation ceremony called the chisungu, in which girls learn songs, dances, and secret terms that only women know (Maybury-Lewis, 1998). In some cultures, special ceremonies also mark a girl’s first menstrual period. Such ceremonies are largely absent in the United States, where a girl’s first period is a private matter. But in other cultures the first period is a cause for celebration involving gifts, music, and food (Hathaway, 1997).

Among the Bemba of Zambia, girls undergo a month-long initiation ceremony called the chisungu, in which girls learn songs, dances, and secret terms that only women know (Maybury-Lewis, 1998). In some cultures, special ceremonies also mark a girl’s first menstrual period. Such ceremonies are largely absent in the United States, where a girl’s first period is a private matter. But in other cultures the first period is a cause for celebration involving gifts, music, and food (Hathaway, 1997).

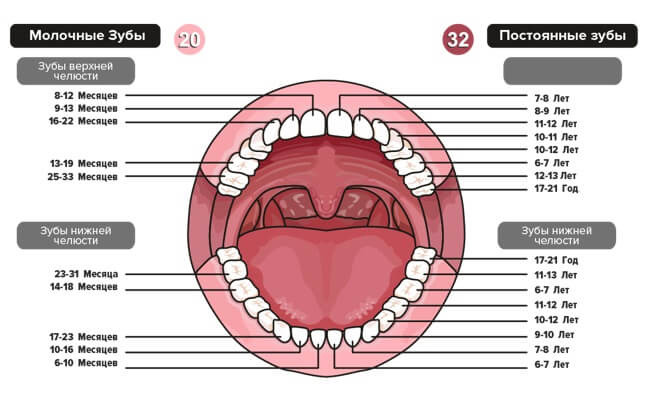

Are rituals more common in traditional societies than in industrial ones such as the United States? Consider the Nacirema, studied by anthropologist Horace Miner more than 50 years ago (Miner, 1956). In this society, many rituals have been developed to deal with the culture’s fundamental belief that the human body is ugly and in danger of suffering many diseases. Reflecting this belief, every household has at least one shrine in which various rituals are performed to cleanse the body. Often these shrines contain magic potions acquired from medicine men. The Nacirema are especially concerned about diseases of the mouth. Miner writes, “Were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums bleed, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them” (p. 505). Many Nacirema engage in “mouth-rites” and see a “holy-mouth-man” once or twice yearly.

Often these shrines contain magic potions acquired from medicine men. The Nacirema are especially concerned about diseases of the mouth. Miner writes, “Were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums bleed, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them” (p. 505). Many Nacirema engage in “mouth-rites” and see a “holy-mouth-man” once or twice yearly.

Spell Nacirema backward and you will see that Miner was describing American culture. As his satire suggests, rituals are not limited to preindustrial societies. Instead, they function in many kinds of societies to mark transitions in the life course and to transmit the norms of the culture from one generation to the next.

Changing Norms and Beliefs

Our examples show that different cultures have different norms, even if they share other types of practices and beliefs. It is also true that norms change over time within a given culture. Two obvious examples here are hairstyles and clothing styles. When the Beatles first became popular in the early 1960s, their hair barely covered their ears, but parents of teenagers back then were aghast at how they looked. If anything, clothing styles change even more often than hairstyles. Hemlines go up, hemlines go down. Lapels become wider, lapels become narrower. This color is in, that color is out. Hold on to your out-of-style clothes long enough, and eventually they may well end up back in style.

When the Beatles first became popular in the early 1960s, their hair barely covered their ears, but parents of teenagers back then were aghast at how they looked. If anything, clothing styles change even more often than hairstyles. Hemlines go up, hemlines go down. Lapels become wider, lapels become narrower. This color is in, that color is out. Hold on to your out-of-style clothes long enough, and eventually they may well end up back in style.

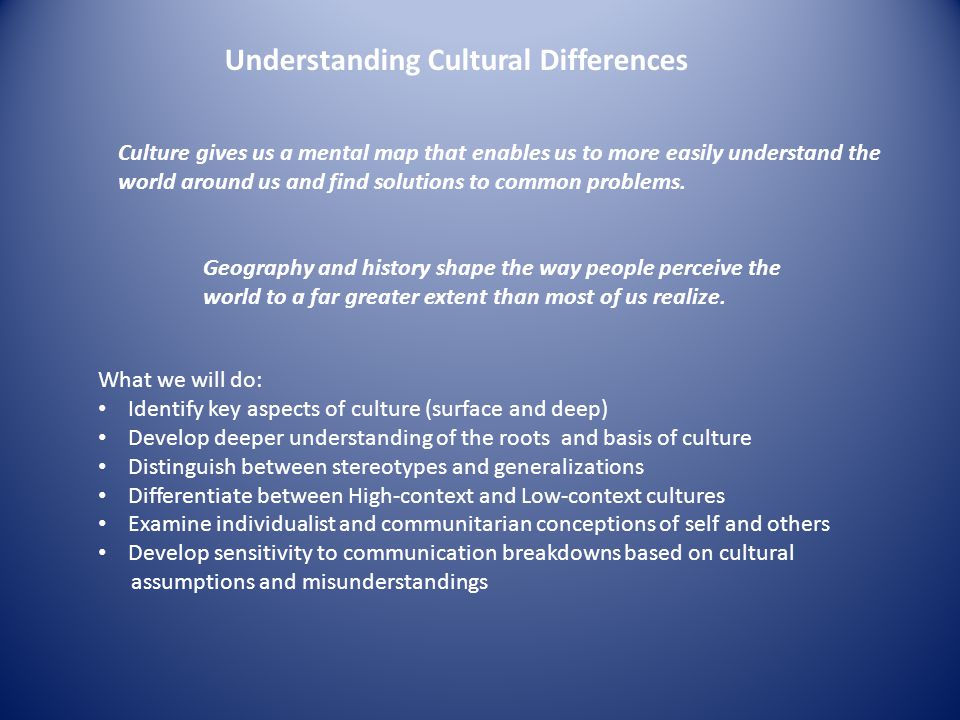

Values

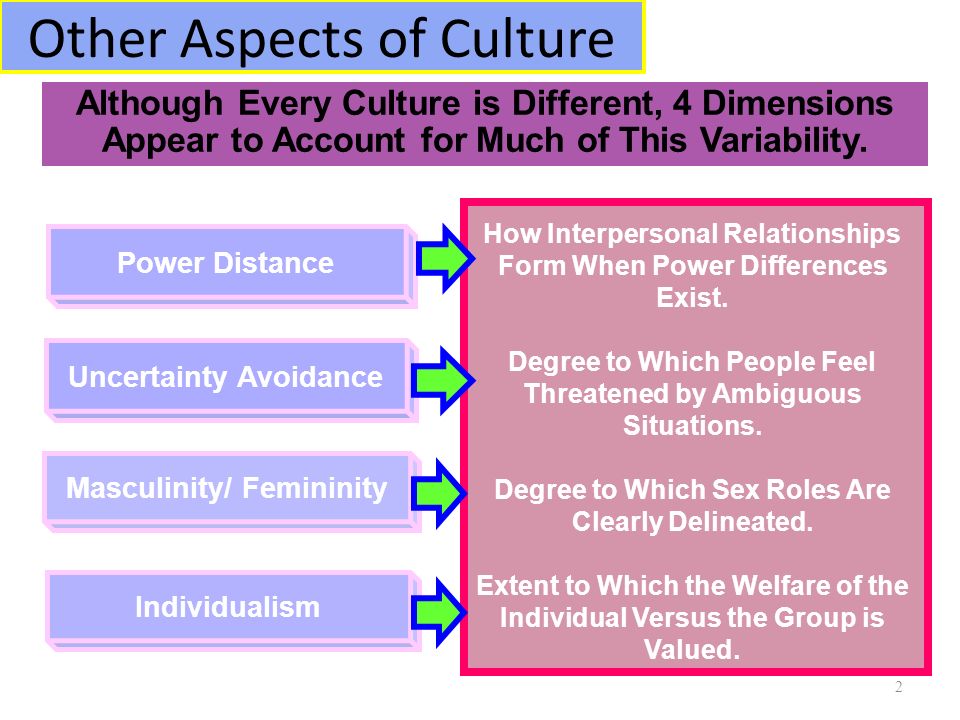

Values are another important element of culture and involve judgments of what is good or bad and desirable or undesirable. A culture’s values shape its norms. In Japan, for example, a central value is group harmony. The Japanese place great emphasis on harmonious social relationships and dislike interpersonal conflict. Individuals are fairly unassertive by American standards, lest they be perceived as trying to force their will on others (Schneider & Silverman, 2010). When interpersonal disputes do arise, Japanese do their best to minimize conflict by trying to resolve the disputes amicably. Lawsuits are thus uncommon; in one case involving disease and death from a mercury-polluted river, some Japanese who dared to sue the company responsible for the mercury poisoning were considered bad citizens (Upham, 1976).

Lawsuits are thus uncommon; in one case involving disease and death from a mercury-polluted river, some Japanese who dared to sue the company responsible for the mercury poisoning were considered bad citizens (Upham, 1976).

Individualism in the United States

In the United States, of course, the situation is quite different. The American culture extols the rights of the individual and promotes competition in the business and sports worlds and in other areas of life. Lawsuits over the most frivolous of issues are quite common and even expected. Phrases like “Look out for number one!” abound. If the Japanese value harmony and group feeling, Americans value competition and individualism. Because the Japanese value harmony, their norms frown on self-assertion in interpersonal relationships and on lawsuits to correct perceived wrongs. Because Americans value and even thrive on competition, our norms promote assertion in relationships and certainly promote the use of the law to address all kinds of problems.

The Work Ethic

Another important value in the American culture is the work ethic. By the 19th century, Americans had come to view hard work not just as something that had to be done but as something that was morally good to do (Gini, 2000). The commitment to the work ethic remains strong today: in the 2008 General Social Survey, 72% of respondents said they would continue to work even if they got enough money to live as comfortably as they would like for the rest of their lives.

Artifacts

The last element of culture is the artifacts, or material objects, that constitute a society’s material culture. In the most simple societies, artifacts are largely limited to a few tools, the huts people live in, and the clothing they wear. One of the most important inventions in the evolution of society was the wheel.

Source: Data from Standard Cross-Cultural Sample.

Although the wheel was a great invention, artifacts are much more numerous and complex in industrial societies. Because of technological advances during the past two decades, many such societies today may be said to have a wireless culture, as smartphones, netbooks and laptops, and GPS devices now dominate so much of modern life. The artifacts associated with this culture were unknown a generation ago. Technological development created these artifacts and new language to describe them and the functions they perform. Today’s wireless artifacts in turn help reinforce our own commitment to wireless technology as a way of life, if only because children are now growing up with them, often even before they can read and write.

Because of technological advances during the past two decades, many such societies today may be said to have a wireless culture, as smartphones, netbooks and laptops, and GPS devices now dominate so much of modern life. The artifacts associated with this culture were unknown a generation ago. Technological development created these artifacts and new language to describe them and the functions they perform. Today’s wireless artifacts in turn help reinforce our own commitment to wireless technology as a way of life, if only because children are now growing up with them, often even before they can read and write.

Sometimes people in one society may find it difficult to understand the artifacts that are an important part of another society’s culture. If a member of a tribal society who had never seen a cell phone, or who had never even used batteries or electricity, were somehow to visit the United States, she or he would obviously have no idea of what a cell phone was or of its importance in almost everything we do these days. Conversely, if we were to visit that person’s society, we might not appreciate the importance of some of its artifacts.

Conversely, if we were to visit that person’s society, we might not appreciate the importance of some of its artifacts.

Key Takeaways

- The major elements of culture are symbols, language, norms, values, and artifacts.

- Language makes effective social interaction possible and influences how people conceive of concepts and objects.

- Major values that distinguish the United States include individualism, competition, and a commitment to the work ethic.

References

Axtell, R. E. (1998). Gestures: The do’s and taboos of body language around the world. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brettell, C. B., & Sargent, C. F. (Eds.). (2009). Gender in cross-cultural perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Brown, R. (2009, January 24). Nashville voters reject a proposal for English-only. The New York Times, p. A12.

Bullough, V. L., & Bullough, B. (1977). Sin, sickness, and sanity: A history of sexual attitudes. New York, NY: New American Library.

Dixon, J. C. (2006). The ties that bind and those that don’t: Toward reconciling group threat and contact theories of prejudice. Social Forces, 84, 2179–2204.

Edgerton, R. (1976). Deviance: A cross-cultural perspective. Menlo Park, CA: Cummings.

Erikson, K. T. (1976). Everything in its path: Destruction of community in the Buffalo Creek flood. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Gini, A. (2000). My job, my self: Work and the creation of the modern individual. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, M. R. (2007). The sounds of silence. In J. M. Henslin (Ed.), Down to earth sociology: Introductory readings (pp. 109–117). New York, NY: Free Press.

Harris, M. (1974). Cows, pigs, wars, and witches: The riddles of culture. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Hathaway, N. (1997). Menstruation and menopause: Blood rites. In L. M. Salinger (Ed.), Deviant behavior 97/98 (pp. 12–15). Guilford, CT: Dushkin.

Laar, C. V., Levin, S., Sinclair, S., & Sidanius, J. (2005). The effect of university roommate contact on ethnic attitudes and behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 329–345.

Maggio, R. (1998). The dictionary of bias-free usage: A guide to nondiscriminatory language. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Maybury-Lewis, D. (1998). Tribal wisdom. In K. Finsterbusch (Ed.), Sociology 98/99 (pp. 8–12). Guilford, CT: Dushkin/McGraw-Hill.

Miles, S. (2008). Language and sexism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Miner, H. (1956). Body ritual among the Nacirema. American Anthropologist, 58, 503–507.

Murdock, G. P., & White, D. R. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology, 8, 329–369.

R. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology, 8, 329–369.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2005). Allport’s intergroup contact hypothesis: Its history and influence. In J. F. Dovidio, P. S. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 262–277). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Ray, S. (2007). Politics over official language in the United States. International Studies, 44,235–252.

Schneider, L., & Silverman, A. (2010). Global sociology: Introducing five contemporary societies (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Shook, N. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Interracial roommate relationships: An experimental test of the contact hypothesis. Psychological Science, 19, 717–723.

Shook, N. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Roommate relationships: A comparison of interracial and same-race living situations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 11, 425–437.

Upham, F. K. (1976). Litigation and moral consciousness in Japan: An interpretive analysis of four Japanese pollution suits. Law and Society Review, 10, 579–619.

Whorf, B. (1956). Language, thought and reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

License

Share This Book

Share on Twitter

What is culture? | Live Science

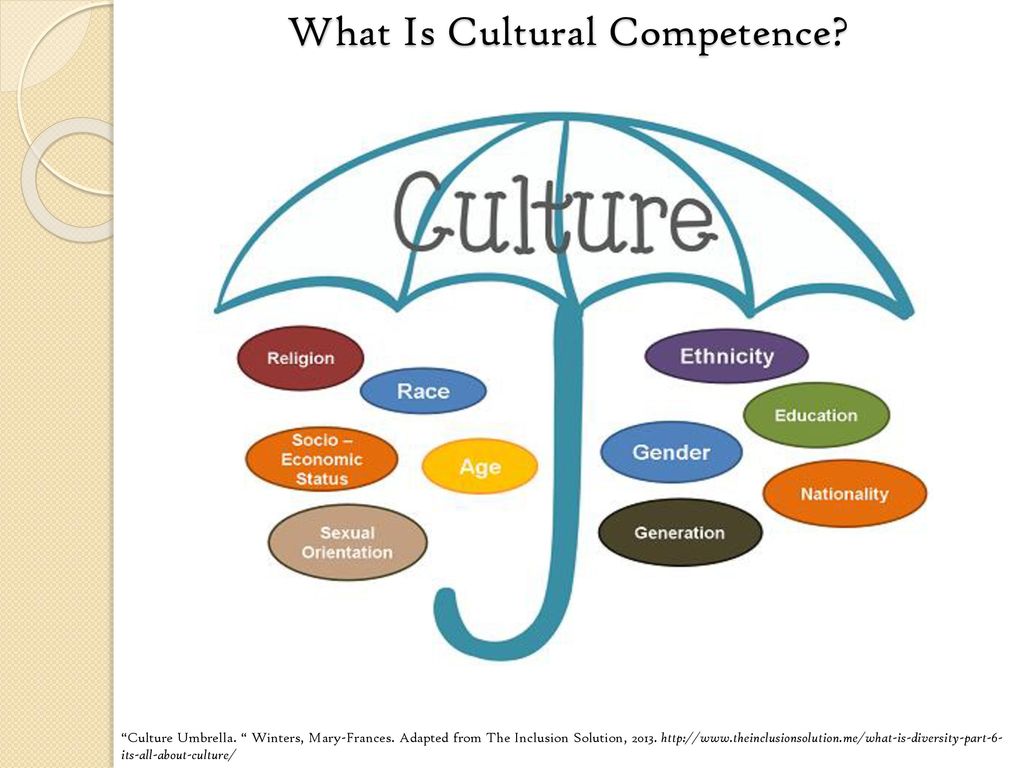

Thai people floating a lamp in Yee Peng festival in Chiang Mai,Thailand. (Image credit: Natnan Srisuwan via Getty Images)Culture is the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts.

The Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition goes a step further, defining culture as shared patterns of behaviors and interactions, cognitive constructs and understanding that are learned by socialization. Thus, culture can be seen as the growth of a group identity fostered by social patterns unique to the group.

"Culture encompasses religion, food, what we wear, how we wear it, our language, marriage, music, what we believe is right or wrong, how we sit at the table, how we greet visitors, how we behave with loved ones and a million other things," Cristina De Rossi, an anthropologist at Barnet and Southgate College in London , told Live Science.

Many countries, such as France, Italy, Germany, the US, India, Russia and China are noted for their rich cultures, the customs, traditions, music, art and food being a continual draw for tourists.

The word "culture" derives from a French term, which in turn derives from the Latin "colere," which means to tend to the earth and grow, or cultivation and nurture, according to Arthur Asa Berger . "It shares its etymology with a number of other words related to actively fostering growth," De Rossi said.

Western culture

The fall of the Roman Empire helped shape Western culture. (Image credit: Harald Nachtmann via Getty Images)

(Image credit: Harald Nachtmann via Getty Images)

The term "Western culture" has come to define the culture of European countries as well as those that have been heavily influenced by European immigration, such as the United States, according to Khan University . Western culture has its roots in the Classical Period of the Greco-Roman era (the fourth and fifth centuries B.C.) and the rise of Christianity in the 14th century. Other drivers of Western culture include Latin, Celtic, Germanic and Hellenic ethnic and linguistic groups.

Any number of historical events have helped shape Western culture during the past 2,500 years. The fall of Rome, often pegged to A.D. 476, cleared the way for the establishment of a series of often-warring states in Europe, according to Stanford University historian Walter Scheidel, each with their own cultures. The Black Death of the 1300s cut the population of Europe by one-third to one-half, rapidly remaking society. As a result of the plague, writes Ohio State University historian John L. Brooke, Christianity became stronger in Europe, with more focus on apocalyptic themes. Survivors in the working class gained more power, as elites were forced to pay more for scarce labor. And the disruption of trade routes between East and West set off new exploration, and ultimately, the incursion of Europeans into North and South America.

As a result of the plague, writes Ohio State University historian John L. Brooke, Christianity became stronger in Europe, with more focus on apocalyptic themes. Survivors in the working class gained more power, as elites were forced to pay more for scarce labor. And the disruption of trade routes between East and West set off new exploration, and ultimately, the incursion of Europeans into North and South America.

Today, the influences of Western culture can be seen in almost every country in the world.

Eastern culture

Buddhism is a big part of some Eastern cultures. Here is the Buddhist temple Seigantoji at Nachi Falls, Japan. (Image credit: Getty/ Saha Entertainment)

Eastern culture generally refers to the societal norms of countries in Far East Asia (including China, Japan, Vietnam, North Korea and South Korea) and the Indian subcontinent. Like the West, Eastern culture was heavily influenced by religion during its early development, but it was also heavily influenced by the growth and harvesting of rice, according to a research article published in the journal Rice in 2012. In general, in Eastern culture there is less of a distinction between secular society and religious philosophy than there is in the West.

In general, in Eastern culture there is less of a distinction between secular society and religious philosophy than there is in the West.

However, this umbrella covers an enormous range of traditions and histories. For example, Buddhism originated in India, but it was largely overtaken by Hinduism after the 12th century, according to Britannica .

As a result, Hinduism became a major driver of culture in India, while Buddhism continued to exert influence in China and Japan. The preexisting cultural ideas in these areas also influenced religion. For example, according to Jiahe Liu and Dongfang Shao , Chinese Buddhism borrowed from the philosophy of Taoism, which emphasizes compassion, frugality and humility.

Centuries of interactions — both peaceful and aggressive — in this region also led to these cultures influencing each other. Japan, for example, controlled or occupied Korea in some form between 1876 and 1945. During this time, many Koreans were pressured or forced into giving up their names for Japanese surnames, according to History. com .

com .

Latin culture

People dressed up for Dia de los Muertos (Image credit: Harald Nachtmann via Getty Images)

The geographic region encompassing "Latin culture" is widespread. Latin America is typically defined as those parts of Central America, South America and Mexico where Spanish or Portuguese are the dominant languages. These are all places that were colonized by or influenced by Spain or Portugal starting in the 1400s. It is thought that French geographers used the term "Latin America" to differentiate between Anglo and Romance (Latin-based) languages, though some historians, such as Michael Gobat, author of "The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy and Race" (American Historical Review, Voll 118, Issue 5, 2013), dispute this.

Latin cultures are thus incredibly diverse, and many blend Indigenous traditions with the Spanish language and Catholicism brought by Spanish and Portuguese colonizers. Many of these cultures were also influenced by African cultures due to enslaved Africans being brought to the Americas starting in the 1600s, according to the African American Registery . These influences are particularly strong in Brazil and in Caribbean nations.

Many of these cultures were also influenced by African cultures due to enslaved Africans being brought to the Americas starting in the 1600s, according to the African American Registery . These influences are particularly strong in Brazil and in Caribbean nations.

Latin culture continues to evolve and spread. A good example is Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, a holiday dedicated to remembering the departed that is celebrated on Nov. 1 and Nov. 2. Day of the Dead dates back to before Christopher Columbus landed in North America, but was moved to its current celebration date by Spanish colonizers, who merged it with the Catholic All Saints Day.

Mexican immigrants to the United States brought the holiday with them, and in the 1970s, artists and activities brought focus to Día de los Muertos as a way of celebrating their Chicano (Mexican-American) heritage, according to the Smithsonian American Art Museum . The holiday is now well-known in the United States.

Middle Eastern culture

A Middle Eastern family eats dinner together. (Image credit: Getty/ Jasmin Merdan)

Roughly speaking, the Middle East encompasses the Arabian peninsula as well as the eastern Mediterranean. The North African countries of Libya, Egypt and Sudan are also sometimes included, according to Britannica . The term "Middle Eastern culture" is another umbrella that encompasses a huge diversity of cultural practices, religious beliefs and daily habits. The region is the birthplace of Judaism, Christianity and Islam and is home to dozens of languages, from Arabic to Hebrew to Turkish to Pashto.

While there is significant religious diversity in the Middle East, the predominant religion by numbers is Islam, and Islam has played a large role in the cultural development of the region. Islam originated in what is today Saudi Arabia in the early seventh century. An influential moment for the culture and development of the Middle East came after the death of the religion's founder, Muhammad, in 632, according to the Metropoliton Museum .

Some followers believed the next leader should be one of Muhammad's friends and confidants; others believed leadership must be passed through Muhammad's bloodline. This led to a schism between Shia Muslims, those who believed in the importance of the bloodline, and Sunni Muslims, who believed leadership should not pass through the family. Today, about 85% of Muslims are Sunni, according to the Council on Foreign Relations . Their rituals and traditions vary somewhat, and divisions between the two groups often fuel conflict.

Middle Eastern culture has also been shaped by the Ottoman Empire, which ruled a U-shaped ring around the eastern Mediterranean between the 14th and early 20th centuries, according to Britannica. Areas that were part of the Ottoman Empire are known for distinctive architecture drawn from Persian and Islamic influences.

African culture

An African mother from a Maasai tribe sits with her baby next to her dwelling in Kenya, Africa. (Image credit: hadynyah/Getty Images)

(Image credit: hadynyah/Getty Images)

Africa has the longest history of human habitation of any continent: Humans originated there and began to migrate to other areas of the world around 400,000 years ago, according to the Natural History Museum in London. Tom White, who serves as the museum's senior curator of non-insect invertebrates, and his team were able to discover this by studying Africa's ancient lakes and the animals that lived in them. As of the time of this article, this research provides the oldest evidence for hominin species in the Arabian peninsula.

African culture varies not only between national boundaries, but within them. One of the key features of this culture is the large number of ethnic groups throughout the 54 countries on the continent. For example, Nigeria alone has more than 300 tribes, according to Culture Trip . Africa has imported and exported its culture for centuries; East African trading ports were a crucial link between East and West as early as the seventh century, according to The Field Museum . This led to complex urban centers along the eastern coast, often connected by the movement of raw materials and goods from landlocked parts of the continent.

This led to complex urban centers along the eastern coast, often connected by the movement of raw materials and goods from landlocked parts of the continent.

It would be impossible to characterize all of African culture with one description. Northwest Africa has strong ties to the Middle East, while Sub-Saharan Africa shares historical, physical and social characteristics that are very different from North Africa, according to Britannica .

Some traditional Sub-Saharan African cultures include the Maasai of Tanzania and Kenya, the Zulu of South Africa and the Batwa of Central Africa. The traditions of these cultures evolved in very different environments. The Batwa, for example, are one of a group of ethnicities that traditionally live a forager lifestyle in the rainforest. The Maasai, on the other hand, herd sheep and goats on the open range.

What is cultural appropriation?

Oxford Reference describes cultural appropriation as: "A term used to describe the taking over of creative or artistic forms, themes, or practices by one cultural group from another. "

"

An example might be a person who is not Native American wearing a Native American headdress as a fashion accessory. For example, Victoria's Secret was heavily criticized in 2012 after putting a model in a headdress reminiscent of a Lakota war bonnet, according to USA Today . These headdresses are laden with meaningful symbolism, and wearing one was a privilege earned by chieftains or warriors through acts of bravery, according to the Khan Academy . The model also wore turquoise jewelry inspired by designs used by Zuni, Navajo and Hopi tribes in the desert Southwest, illustrating how cultural appropriation can lump together tribes with very different cultures and histories into one stereotyped image.

More recently, in 2019, Gucci faced a similar backlash for selling an item named "the indy full turban" which caused considerable anger from the Sikh community, according to Esquire . Harjinder Singh Kukreja, a Sikh restaurateur and influencer, wrote to Gucci on Twitter , stating: "the Sikh Turban is not a hot new accessory for white models but an article of faith for practising Sikhs. Your models have used Turbans as ‘hats’ whereas practising Sikhs tie them neatly fold-by-fold. Using fake Sikhs/Turbans is worse than selling fake Gucci products."

Your models have used Turbans as ‘hats’ whereas practising Sikhs tie them neatly fold-by-fold. Using fake Sikhs/Turbans is worse than selling fake Gucci products."

Constant change

No matter what a culture looks like, one thing is for certain: Cultures change. "Culture appears to have become key in our interconnected world, which is made up of so many ethnically diverse societies, but also riddled by conflicts associated with religion, ethnicity, ethical beliefs, and, essentially, the elements which make up culture," De Rossi said. "But culture is no longer fixed, if it ever was. It is essentially fluid and constantly in motion."

This makes it difficult to define any culture in only one way. While change is inevitable, most people see value in respecting and preserving the past. The United Nations has created a group called The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to identify cultural and natural heritage and to conserve and protect it. Monuments, buildings and sites are covered by the group's protection, according to the international treaty, the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage . This treaty was adopted by UNESCO in 1972.

Monuments, buildings and sites are covered by the group's protection, according to the international treaty, the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage . This treaty was adopted by UNESCO in 1972.

Additional reporting by Live Science Contributors Alina Bradford, Stephanie Pappas and Callum McKelvie.

Callum McKelvie is features editor for All About History Magazine. He has a both a Bachelor and Master's degree in History and Media History from Aberystwyth University. He was previously employed as an Editorial Assistant publishing digital versions of historical documents, working alongside museums and archives such as the British Library. He has also previously volunteered for The Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum, Gloucester Archives and Gloucester Cathedral.

Cultural aspect of human activity

UDK 008

A. Ya. Sciences, Prof., Chief Researcher, Russian Research Institute of Cultural and Natural Heritage. D. S. Likhacheva E-mail: [email protected]

D. S. Likhacheva E-mail: [email protected]

CULTURAL ASPECT OF HUMAN ACTIVITY

the profile of symbolization of products of activity, which is connected with the conditionality of any activity by culture and its principles of social relations.

Keywords: culture, activity, value orientations, dominant forms of social organization, activities, forms of symbolization of products of activity

For citation: Flier, A. Ya. arts. - 2019. - No. 1 (57). - S. 35-41.

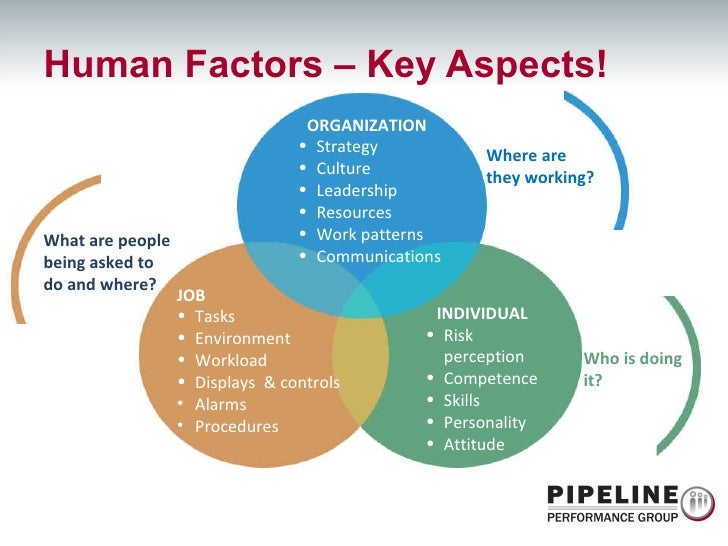

It is difficult to single out culture as a self-sufficient phenomenon, since it permeates all types of human activity, often dissolving in them without traces visible to an outside observer. Culture is present in everything that is done by man, said, written or provided by him. In the end, culture is just a form of organization of matter, however, the most complex of all known to this day. It is even more complicated than the human mind, since it combines the minds, wills and interests of several people at once (a certain number of people) in their joint activity, understanding or consumption. At the same time, culture is neither the goal nor the cause of activity, but only a means, a factor that ensures the collective nature of its implementation or consumption of its results, as well as its semantic interpretation. Technologically, the activity itself can be both group and individual, but in the last0003

At the same time, culture is neither the goal nor the cause of activity, but only a means, a factor that ensures the collective nature of its implementation or consumption of its results, as well as its semantic interpretation. Technologically, the activity itself can be both group and individual, but in the last0003

In this case, the results are used by the group consumer.

No poet writes poems in some unknown language, but always chooses a language that other people can read and understand. No matter how extravagant the form of any work, it is always calculated to be approved by a select group of consumers, however small. This is all the more true for the products of any material activity of people and the results of their social and organizational activity. All products are made for someone, to be used by other people. This is the special principle of human activity, which distinguishes him from an animal that does everything primarily for itself, its female, and at best for its young, but never for anyone else. And the suitability of the results of the activities of some people for use

And the suitability of the results of the activities of some people for use

35

culture provides them with others. This is one of its main functions.

But it is also a universal measure of culture. By the extent to which the fruits or results of the activities of some people are acceptable for consumption or understanding by other people, one can judge and say a lot about the culture of both the former and the latter.

One of the main provisions of the Normative theory of culture is the maxim that culture is not a branch of activity that produces its own specific product, but a universal modality that permeates all branches of activity and introduces into them the possibility of collective implementation of this activity or the consumption of its results, a certain orderliness, as well as some symbolism associated with the system of value orientations [see. about it: 9]. Culture is a system of relationships between people that contributes to their mutual understanding and the implementation of joint activities or the consumption of its products.

With all the variety of activities and their technologies that have developed in history, it is possible to single out some universal parameters introduced into any activity by culture, which also develop and change in the course of time. According to them, one can judge the degree of “culturality” of this activity, i.e., its conditionality by the culture and system of values that prevail in a particular society and in a particular era. It seems that at least three such parameters can be distinguished in the activity:

1. The dominant form of social organization of subjects of activity.

2. Dominant order of business.

3. Dominant profile of product/outcome symbolization.

It should be emphasized that all these parameters are mobile in each society and change with each epoch, but they reflect the specifics of culture characteristic of a given society

in each period of its history, and the general social conditionality of the entire system of activities and the system of values that prevailed in every historical period. Let's consider them in order.

Let's consider them in order.

First. The dominant form of social organization of actors, which is most revealingly dictated by history.

In the primitive era, in fact, there was only one form of social organization - ethnic or, more precisely, emerging ethnic. The early primitive tribal community was more like a population, and the main bond of the community of people was precisely their genetic relationship (real or imagined), and the cultural acceptability of the products of activity was built mainly on a totemic basis. Ours is what belongs to our ancestral totem, carries its symbolism, corresponds to the tastes of our ancestors, etc. It was according to this principle that people were differentiated into “us” and “them”, as well as the products of their activity.

With the unification of clans into tribes, naturally, the consanguineous principle of division into friends and foes became incorrect; members of the tribe already belonged to several genera. Then the actual ethnic principle of association prevailed, based on a common language, mythology, customs and other manifestations of local culture. Ours are fellow tribesmen who speak the same language as the entire tribe, who believe in the same myths, adhere to the same customs, etc. Not ours are foreigners who have everything different. Naturally, the products of activity were accepted if they corresponded to our ethno-cultural stereotypes, and rejected if they were culturally alien [see. about it: 1; 6]. In the primitive era, the most effective tool for controlling the consciousness and behavior of a person was his interest in membership in an ethno-tribal collective and the fear of expulsion from it. Hence the importance of ethno-

Ours are fellow tribesmen who speak the same language as the entire tribe, who believe in the same myths, adhere to the same customs, etc. Not ours are foreigners who have everything different. Naturally, the products of activity were accepted if they corresponded to our ethno-cultural stereotypes, and rejected if they were culturally alien [see. about it: 1; 6]. In the primitive era, the most effective tool for controlling the consciousness and behavior of a person was his interest in membership in an ethno-tribal collective and the fear of expulsion from it. Hence the importance of ethno-

36

tribal social organization, especially since there was no alternative to it.

In the agrarian era, the range of forms of social associations of people has expanded significantly. In addition to the already well-known ethnic form of association, political, confessional, class, and professional forms also appeared. Of course, due to this or that combination of external factors, one or the other could dominate, however, the confessional form of uniting people based on their belonging to a single religion and church community received the most statistically significant social significance. The semantic dichotomy of one's own/them in this era most often resulted in the opposition of a co-religionist/non-believer. In any case, this opposition was the most important in the agrarian period of history. Even a foreigner, speaking a different language, but professing the same faith as the person who evaluates him, was already his own; was perceived as an ethnically close person (for example, Orthodox Greeks, Serbs and Georgians in Ancient Russia).

The semantic dichotomy of one's own/them in this era most often resulted in the opposition of a co-religionist/non-believer. In any case, this opposition was the most important in the agrarian period of history. Even a foreigner, speaking a different language, but professing the same faith as the person who evaluates him, was already his own; was perceived as an ethnically close person (for example, Orthodox Greeks, Serbs and Georgians in Ancient Russia).

In the agrarian era, the greatest ideological conditioning of all aspects of human life was observed than in other periods of history. And the most effective way to control the consciousness and behavior of a person was an appeal to the religious foundations of his existence. Accordingly, the confessional form of organization of people at that time was the main, existentially dominant.

Of course, there were exceptions to this rule. For example, European Antiquity in the pre-Christian period adhered mainly to the ethnic or political identification of people. But this era is generally not very typical for the agrarian history of other peoples of the Earth [see. about it, for example: 4; 7], which makes it unique. We know Antiquity mainly from the masterpieces of architecture, sculpture, and philosophy. But in terms of social and religious development in classical antiquity, much of the late primitive archaism was also preserved (especially in Greece). In pe-

But this era is generally not very typical for the agrarian history of other peoples of the Earth [see. about it, for example: 4; 7], which makes it unique. We know Antiquity mainly from the masterpieces of architecture, sculpture, and philosophy. But in terms of social and religious development in classical antiquity, much of the late primitive archaism was also preserved (especially in Greece). In pe-

During the Middle Ages, this archaism was overcome.

Thus, in different parts of the Earth in the agrarian era, the confessional form of people's associations dominated, which in fact was also political. Accordingly, the products of activity were accepted mainly when they carried the symbolism of “our” religion, and were rejected otherwise. Of course, there were exceptions here too, but this approach prevailed statistically.

In the industrial era, the whole spectrum of different bases for associations of people, which had developed in the previous agrarian period, was preserved. But another basis gradually became dominant - the political one (although the confessional one retained its influence for a long time). The dichotomy of friend/foe now looked like a compatriot/foreigner. A compatriot could have any origin, profess any religion, etc., the main thing is that he faithfully serve the Fatherland. Let us recall the Russian nobility of the 18th - 19th centuries, it included Germans, Scots, French, etc., who were both Lutherans and Catholics, etc. But this no longer mattered. Service to the new Fatherland was the main identification sign of a person of this period.

But another basis gradually became dominant - the political one (although the confessional one retained its influence for a long time). The dichotomy of friend/foe now looked like a compatriot/foreigner. A compatriot could have any origin, profess any religion, etc., the main thing is that he faithfully serve the Fatherland. Let us recall the Russian nobility of the 18th - 19th centuries, it included Germans, Scots, French, etc., who were both Lutherans and Catholics, etc. But this no longer mattered. Service to the new Fatherland was the main identification sign of a person of this period.

An effective tool for controlling the consciousness and behavior of a person in the industrial era was an appeal to his political loyalty to the authorities. A person is associated with the state he serves, therefore the national-political form of the social organization of people was the most adequate at that time.

In this era, the concept of a nation was born. In our country, the Stalinist understanding of the nation as the highest phase of ethnic development (tribe - nationality - nation) is still in use [see. about this: 8], hence the nationality of a person is understood as his ethnic origin (according to his parents). In the rest of the world, a different understanding of the nation as an association of fellow citizens of a country is widespread. Hence the national

about this: 8], hence the nationality of a person is understood as his ethnic origin (according to his parents). In the rest of the world, a different understanding of the nation as an association of fellow citizens of a country is widespread. Hence the national

37

Nationalization is a transition to state ownership, the League of Nations and the United Nations are associations of states, not ethnic groups. It was the nation as a political association of fellow citizens that turned into the main form of social organization of people during the industrial era. Accordingly, the preferred products of activity are domestic goods, and not foreign ones. In the United States, the slogan “If you are an American, then buy American goods” was in use at one time.

Now in the post-industrial era, the national identity of a person no longer matters. Modern means of communication allow him to live in England and work in Australia. Paris now has more Africans than Europeans. The friend/foe dichotomy is now based not on a person's nationality, but on his profession and looks like a colleague/specialist of a different profile. People unite more around a common work than on any other basis. This is the main cultural principle of organizing people in the modern era, supported by multiculturalism, globalization, etc. It is significant that the economic side of life has become a more effective way to control a person’s consciousness and behavior than ideology, and therefore the appeal to his professional interests is now the main social management tool.

People unite more around a common work than on any other basis. This is the main cultural principle of organizing people in the modern era, supported by multiculturalism, globalization, etc. It is significant that the economic side of life has become a more effective way to control a person’s consciousness and behavior than ideology, and therefore the appeal to his professional interests is now the main social management tool.

At the same time, it must be remembered that throughout the entire post-primitive history, several forms of social organization existed in parallel in communities. And, of course, in this or that community, for various reasons, some other form than those described could temporarily dominate; for example, estate-but-class, which has always been very influential. But this form of social organization was hostile to the majority of the population, who constantly fought against it (uprisings of slaves, peasant riots, revolutions). After all, democracy is what it is

victory over class differentiation of mankind. In a democracy, a person's belonging to any class does not matter, everyone is equal before the law. From this point of view, the communist doctrine, declaring another variant of the estate-class social organization, does not fit into the main trend of the historical development of mankind.

In a democracy, a person's belonging to any class does not matter, everyone is equal before the law. From this point of view, the communist doctrine, declaring another variant of the estate-class social organization, does not fit into the main trend of the historical development of mankind.

It would seem that all this is completely speculative reasoning. What difference does it make according to what principle people unite, the main thing is what and how they do. But it turns out that the basis for their association decisively affects what and how they do, the whole system of their value preferences. This is one of the most important channels of cultural regulation of the principles and results of people's activities. The influence of culture as a modality on human activity is manifested very clearly here. What brings people together determines the subject of their activity.

Second. The dominant order of activities, which also reflected the prevailing attitudes of the culture of the era. Two orders of activity can be distinguished here: the tradition that dominated the primitive and agrarian eras, and the innovation that dominated the industrial and post-industrial eras. Although these two principles are in opposition to each other, in fact, in any era, both existed. The only question is the relative predominance of either one or the other in the practice of a certain era and a certain class of producers.

Two orders of activity can be distinguished here: the tradition that dominated the primitive and agrarian eras, and the innovation that dominated the industrial and post-industrial eras. Although these two principles are in opposition to each other, in fact, in any era, both existed. The only question is the relative predominance of either one or the other in the practice of a certain era and a certain class of producers.

Tradition as an order of activity reflects the attitude towards repeating what has already proven itself to be a suitable way of making a product that is successful in its social functions. This order of activity has received the greatest distribution in the peasant environment. And accordingly, tradition dominated in the primitive era, when the entire tribe was essentially engaged in peasant labor, and in the agrarian era, when rural producers made up the absolute majority of the population.0002 Tradition is an eternal repetition both in material production and in spiritual [12]. Existence is a repetition of what was once created by the gods, and, accordingly, human activity must reproduce the order dictated from above. This does not mean that all the activities of the people of these eras were reduced only to repeating something of the past, but such a repetition was considered the most reliable way to obtain the desired result. It should only be noted that if in the primitive era tradition prevailed both in technologies and in the typology of the product produced, then in agrarian tradition it primarily concerned the typology (observed form) of the product, and the technology for its manufacture was no longer so controlled and was slowly developing .

Existence is a repetition of what was once created by the gods, and, accordingly, human activity must reproduce the order dictated from above. This does not mean that all the activities of the people of these eras were reduced only to repeating something of the past, but such a repetition was considered the most reliable way to obtain the desired result. It should only be noted that if in the primitive era tradition prevailed both in technologies and in the typology of the product produced, then in agrarian tradition it primarily concerned the typology (observed form) of the product, and the technology for its manufacture was no longer so controlled and was slowly developing .

Another type of order in activity was innovation, that is, the constant development of both the typology and the technology of the product being produced. An innovator regularly invents something new. The social carriers of this approach to activity in ancient times were artisans and merchants, and now they are scientists, entrepreneurs and engineers. These types of figures actively developed and asserted themselves in the industrial era, and in the post-industrial era they gained complete social predominance. If in the industrial era more new types of products (or their new forms) appeared, then in the post-industrial era, innovation in technology began to prevail. Development and progress are already considered as an end in itself of activity, far from being always conditioned by actual human needs. This does not mean that there is no place for tradition in modern activity, but it has faded into the background.

These types of figures actively developed and asserted themselves in the industrial era, and in the post-industrial era they gained complete social predominance. If in the industrial era more new types of products (or their new forms) appeared, then in the post-industrial era, innovation in technology began to prevail. Development and progress are already considered as an end in itself of activity, far from being always conditioned by actual human needs. This does not mean that there is no place for tradition in modern activity, but it has faded into the background.

Of course, innovation is associated with scientific and technological progress, and it is impossible to say what is the cause and what is the effect. Innovative activity, of course, requires much greater intellectual effort than traditional activity, and this, too, is a manifestation of the general development of human culture, which has become more intellectual over the centuries. At the same time, one should not expect that with time all of humanity will switch to innovative forms of labor. For many reasons, part of the population will always work according to traditionalist patterns. But they will be in a clear minority and will not have a big impact on social life.

For many reasons, part of the population will always work according to traditionalist patterns. But they will be in a clear minority and will not have a big impact on social life.

Thus, the history of human activity and the change of orders in it are closely connected with the historical evolution of culture, which itself is also sometimes interpreted as activity [6].

Third. The dominant profile of the symbolization of products/results of activities is a reflection of the practical results of activities in the symbolic forms of culture. This phenomenon, of course, also evolved from era to era, expressing the most relevant meanings and interpretations of the products of activity for its time.

In the primitive era, the world was perceived through the prism of its origin (the dominant doctrine of cosmogenesis in this community [10]), and the products of activity symbolized mainly “our” origin of each thing by marking it with the symbolism of “our” totem. Everything was built on the dichotomy of ours / not ours.

In the agrarian era, under the conditions of a total religious interpretation of everything that exists, the symbolization of the products of the activities of communities was mainly based on the sacred/profane dichotomy [see, for example: 3]. It was important to emphasize the piety of this or that product and the fact that it was made “correctly” by a believer. Equally important was the selection of strictly religious (sacred) products in terms of function and meaning and distinguishing them from the profane.

In the industrial era, the symbolization of the products of the community's activity began to be based mainly on signs of the social prestige of a particular product, and starting from the Middle Ages, on the degree of its fashionability, i.e., the correspondence of its forms to the most prestigious examples of its time. Fashion was born in an elite culture, but during the XIX - XX centuries.

39

spread to all social cultures, becoming a universal sign of prestige [see, for example: 2]. Cultural symbolization mainly reflected the dichotomy of prestige/not prestige, which was reduced to the opposition of fashionable/not fashionable.

Cultural symbolization mainly reflected the dichotomy of prestige/not prestige, which was reduced to the opposition of fashionable/not fashionable.

In the post-industrial era, it seems that the cultural symbolization of the products of activity reflects mainly the dichotomy of the modern/archaic [see. about it, for example: 11]. Of course, modern forms are preferred, but this does not mean that archaic ones are rejected in principle; as a subject of stylization in certain contexts they are acceptable. But authentic archaism has a place only in a museum, and in today's life only its stylizations are permissible, archaic in form, but modern in function. This is the setting of modern culture, and the dominant symbolization of modern products of activity fully reflects this.

Thus, the basic principles of culture as a modality that permeates all sectoral types of human activity affect the processes of self-organization of mankind, self-regulation of human activity and the actual symbolization and interpretation of the products of this activity as the results of a person’s social activity aimed at satisfying the interests of the person himself.

Here, the main trends in the development of activities under the influence of culture were considered. At the same time, one should not think that all mankind has been and will be engaged in activities only within the framework of these tendencies. For various reasons, part of the population is oriented towards alternative modes of activity and exists perfectly within their borders. But these alternative regimes also evolve in history and adapt to dominant trends, so the influence of culture takes place here too, albeit in a peculiar form.

One way or another, but with the help of the means discussed above and some other, less important ones, culture regulates the consciousness and behavior of people, keeping them within the framework of value orientations historically established in a particular community. It must be said that the value orientations of most peoples are very close to each other, which makes it very easy for culture to solve many problems of intercultural dialogue. Differences in value orientations are clearly visible only among peoples at different stages of social development. But the process of development of modes of activity under the influence of culture was precisely the subject of our consideration in this article.

Differences in value orientations are clearly visible only among peoples at different stages of social development. But the process of development of modes of activity under the influence of culture was precisely the subject of our consideration in this article.

1. Alekseev, V. P. Formation of mankind / V. P. Alekseev. - Moscow: Politizdat, 1984. - 462 p.

2. Bart, R. Fashion system. Articles on the semiotics of culture / R. Bart. - Moscow: Publishing house im. Sabashnikov, 2003. - 512 p.

3. Binevsky, IA The dialectic of the sacred and the profane in the European socio-cultural process: author. dis. ... cand. philosophy Sciences / I. A. Binevsky. - Moscow: MosGU, 2012. - 32 p.

4. Greydina, NL Antiquity from A to Z: words-ref. / N. L. Greidina, A. A. Melnichuk. - Moscow: East-West AST, 2008. - 384 p.

5. Kagan, MS Human activity (Experience of system analysis) / MS Kagan. - Moscow: Politizdat, 1974. - 328 p.

6. Kosven, MO Essays on the history of primitive culture / MO Kosven. - Moscow: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1957. - 240 p.

- Moscow: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1957. - 240 p.

7. Losev, AF Antiquity as a type of culture / AF Losev, MA Chistyakova, T. Yu. Borodai. - Moscow: Nauka, 1998. - 336 p.

8. Malakhov, VS Nationalism as a political ideology: textbook. allowance / V. S. Malakhov. -Moscow: Book. house "University", 2004. - 320 p. 9shikige/. - Date of access: 12/28/2018.

40

10. Frankfort, G. On the Threshold of Philosophy. Spiritual quest of an ancient man / G. Frankfort, G. A. Frankfort, J. Wilson, T. Jacobsen. - Moscow: Progress, 1984. - 238 p.

11. Khachaturyan, VM “Second Life” of the Archaic: Archaizing Tendencies in the Civilization Process / VM Khachaturyan. - Moscow: Academia, 2009. - 290 p.

12. Eliade, M. The myth of the eternal return. Archetypes and repeatability / M. Eliade. - St. Petersburg: Aleteyya, 1998. - 258 p.

Received: 02/04/2019

A. Flier

Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor, Chief Researcher of the Russian Research Institute for Cultural and Natural Heritage. named after D. S. Likhachev E-mail: [email protected]

named after D. S. Likhachev E-mail: [email protected]

HUMAN ACTIVITY CULTURAL ASPECT

Abstract. The article examines the influence of culture on the process of human activity, the historical change in the dominant forms of social organization of stakeholders, the dominant order of the activity itself and the dominant profile of symbolization of the products of activity, which is due to the conditionality of any activity culture and its principles of social relations.

Keywords: Culture, activity, value orientations, the dominant forms of social organization, orders of activity, forms of sym-bolization of the products of activity

For citing: Flier A. 2019. Human Activity Cultural Aspect. Culture and Arts Herald. No 1 (57): 35-41.

References

1. Alekseev V. 1984. Stanovleniye chelovechestva [The formation of humanity]. Moscow: Politizdat. 462 p. (In Russ.).

2. Barthes R. 2003. Sistema mody. Stat'i po semiotike kul'tury [Fashion system. Articles on the semiotics of culture]. Moscow: Izda-tel'stvo im. Sabashnikovykh. 512 p. (In Russ.).

Articles on the semiotics of culture]. Moscow: Izda-tel'stvo im. Sabashnikovykh. 512 p. (In Russ.).

3. Binevskii I. 2012. Dialektika sakral'nogo i profannogo v evropeyskom sotsiokul'turnom protsesse [The dialectic of the sacred and profane in the European socio-cultural process]. Moscow: MosGU. 32 p. (In Russ.).

4. Greidina N., Melnichuk A. 2008. Antichnost' ot A do YA [Antiquity from A to Z]. Moscow: Vostok-Zapad AST. 384 p. (In Russ.).

5. Kagan M. 1974. CHelovecheskaya deyatel'nost' (Opyt sistemnogo analiza) [Human activity (Experience in systems analysis)]. Moscow: Politizdat. 328p. (In Russ.).

6. Kosven M. 1957. Ocherki istorii pervobytnoy kul'tury [Essays on the history of primitive culture]. Moscow: Izd-vo AN SSSR. 240p. (In Russ.).

7. Losev A., CHistiakova M., Borodai T. 1998. Antichnost' kak tip kul'tury [Antiquity as a type of culture]. Moscow: Science. 336 p. (In Russ.).

8. Malakhov V. 2004. Natsionalizm kak politicheskaya ideologiya [Nationalism as a political ideology]. Moscow: Knizhnyy dom "Universitet". 320p. (In Russ.).

Moscow: Knizhnyy dom "Universitet". 320p. (In Russ.).

9. Flier A. 2019. Philosophical prolegomena to the normative theory of culture [Electronic resource]. Kul'tura kul'tury [Culture of culture]. No 1. Available from: http://cult-cult.ru/the-philosophical-prolegomena-to-a-normative-theory-of-culture/ (accessed: 12/28/2018). (In Russ.).

10. Frankfort H., Frankfort H. A., Wilson J., Jacobsen T. 1984. V preddverii filosofii. Dukhovnye iskaniya drevnego cheloveka [On the threshold of philosophy. Spiritual quest of ancient man]. Moscow: Progress. 238p. (In Russ.).

11. Khachaturian M. 2009. "Vtoraya zhizn'" arkhaiki: arkhaizuyushchie tendentsii v tsivilizatsionnom protsesse [Archaic "Second Life": archaizing tendencies in the civilization process]. Moscow: Academy. $290 (In Russ.).

12. Eliade M. 1998. Mif o vechnom vozvrashchenii. Arkhetipy i povtoryaemost' [The myth of the eternal return. Archetypes and Repeatability]. St. Petersburg: Aleteyya. 258p. (In Russ. ).

).

Received 02/04/2019

41

Cultural industries: two aspects of understanding | Lazareva

1. Astafieva O.N., Razlogov K.E. Culturology: subject and structure [Electronic resource] // Culturological journal. 2010. No. 1. URL: http://www.cr-journal.ru/rus/journals/2.html (date of access: 10/15/2017).

2. Anheier H., Isar Y. The Cultural Economy. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2008. 400 p.

3. Zelentsova E.V. Formation and development of creative industries in modern culture: analysis of foreign experience: dis. ... cand. cultural studies. Moscow, 2008. 153 p.

4. Bokova A.V. Cultural, creative, creative industries as a phenomenon of modern culture: the experience of conceptualization: dis. ... cand. philosophy Sciences. Tomsk, 2016. 174 p.

5. Horkheimer M., Adorno T. Dialectics of education. Philosophical fragments / transl. with him. M. Kuznetsova. Moscow ; St. Petersburg: Medium Yuventa, 1997. 312 p.

6. Landry C. Creative city / per. from English. V. Gnedovsky, M. Khrustaleva. Moscow: Klassika-XXI, 2005. 399 p.

Creative city / per. from English. V. Gnedovsky, M. Khrustaleva. Moscow: Klassika-XXI, 2005. 399 p.

7. Hawkins J. Creative economy: how to turn ideas into money / per. from English. I. Shcherbakova. Moscow: Klassika-XXI, 2011. 256 p.

8. Florida R. Creative class: people who change the future / per. from English. A. Konstantinov. Moscow: Klassika-XXI, 2005. 430 p.

9. Flier A.Ya. Cultural industries in history and modernity: types and technologies [Electronic resource] // Humanitarian information portal "Knowledge. Understanding. Skill". 2012. No. 3. URL: http://zpu-journal.ru/e-zpu/2012/3/Flier_Cultural-Industries/ (date of access: 10/15/2017).

10. Hezmondalsh D. Cultural industries / per. from English. I. Kushnareva. Moscow: Ed. House of the Higher School of Economics, 2014. 453 p.

11. Potts J.D., Cunningham S.D., Hartley J., Ormerod P. Social Network Markets : a New Definition of the Creative Industries // Journal of Cultural Economics. 2008 Vol. 32(3). P. 166-185.

32(3). P. 166-185.

12. Vasnetsky A.A., Zuev S.E. Cultural industries as a significant policy factor [Electronic resource] // Power. 2010. No. 4. URL: http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/kulturnye-industrii-kak-znachimyy-faktorpolitiki (date of access: 10/15/2017).

13. Brown J. Cultural industries: Identification of the cultural resources of the territory [Electronic resource]: Presentation at the seminar "Cultural industries / Identification of the cultural resources of the territory" (July 14-18, 2003, Petrozavodsk) // Institute of Cultural Policy. URL: http://www.cpolicy.ru/analytics/64.html (date of access: 10/15/2017).

14. Bogatyreva E.A. The time factor in the formation of cultural industries [Electronic resource] // Culturological journal. 2012. No. 1. URL: http://www.cr-journal.ru/rus/journals/118.html (date of access: 10/15/2017).

15. Zelentsova E.V. From creative industries to creative economy // Management consulting. 2009. No. 3. S. 190-199.

16. Meteleva E.R. Evaluation of the socio-economic effect of the development of urban clusters of creative and cultural industries // ETAP: Economic theory, analysis, practice. 2011. No. 3. S. 26-43.

Meteleva E.R. Evaluation of the socio-economic effect of the development of urban clusters of creative and cultural industries // ETAP: Economic theory, analysis, practice. 2011. No. 3. S. 26-43.

17. Likhanina E.N. Creative and creative industries as a socio-cultural condition for the development of a modern industrial city // Bulletin of the Kemerovo State University of Culture and Arts. 2015. No. 4(33-1). pp. 70-78.

18. Measuring the Economic Contribution of Cultural Industries : A Review and Assessment of Current Methodological Approaches. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012. 109 p.

19. Lebedeva N.M., Tatarko A.N. Culture as a factor of social progress. Moscow: Yustitsinform, 2009. 408 p.

20. Creative industries in the city: challenges, projects and solutions: Sat. scientific articles of students and teachers of the National Research University Higher School of Economics / ed. ed. Yu.O. Papushina, M.V. Matetska. St. Petersburg: Levsha, 2012.