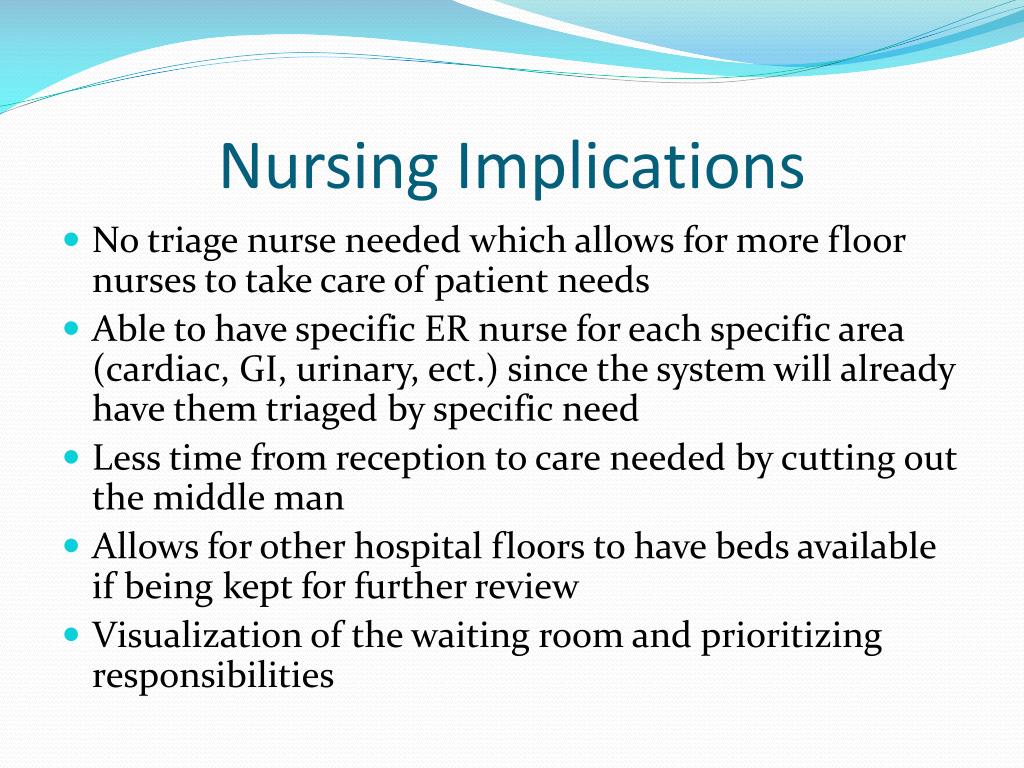

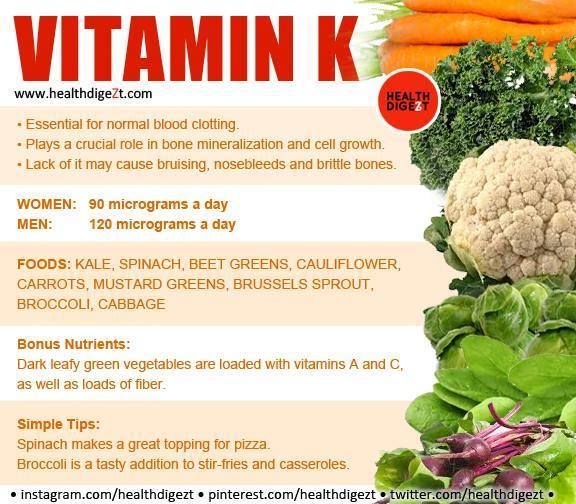

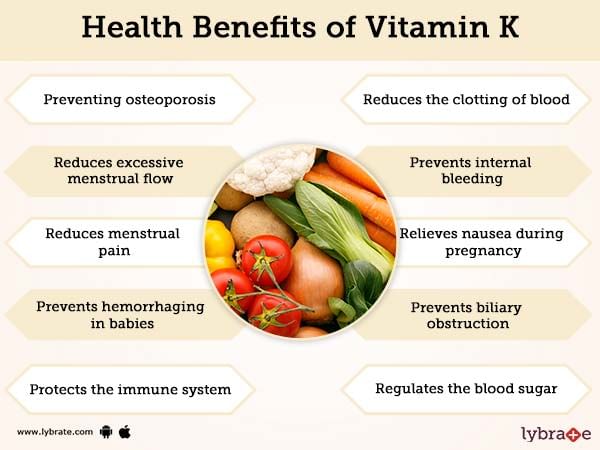

Vitamin k nursing implication

Vitamin K at birth | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Vitamin K at birth | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content5-minute read

Listen

Key facts

- Vitamin K helps your baby’s blood to clot.

- Babies need more vitamin K than they get from their mother during pregnancy or from breast milk.

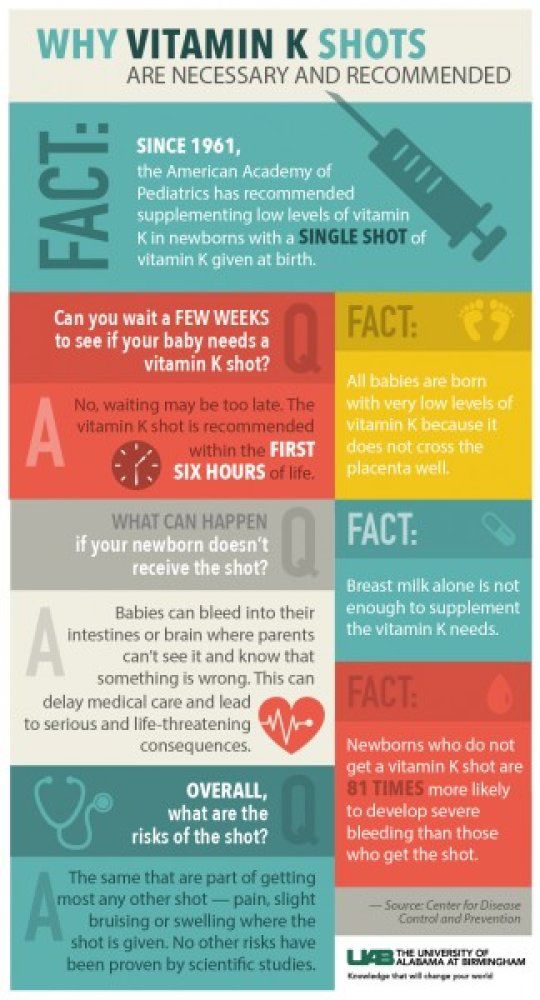

- Parents of all newborns are offered a vitamin K injection for their baby soon after birth.

- This helps prevent babies from becoming vitamin K deficient.

- Without the injection, they are at risk of developing a condition called Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding (known as VKDB).

What is vitamin K?

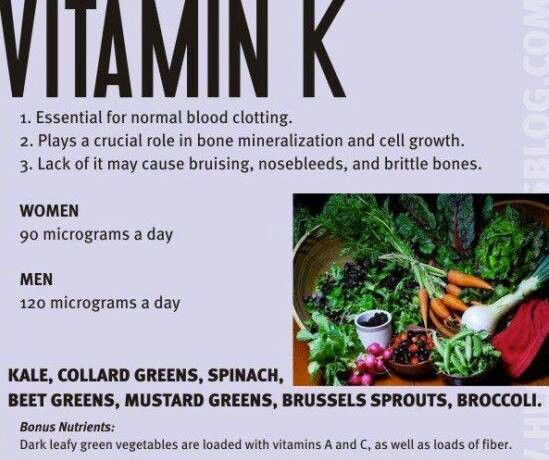

Vitamin K is an essential vitamin, and has an important role in maintaining good health by helping blood to clot. Vitamin K helps prevent serious bleeding.

Why is vitamin K important for my baby?

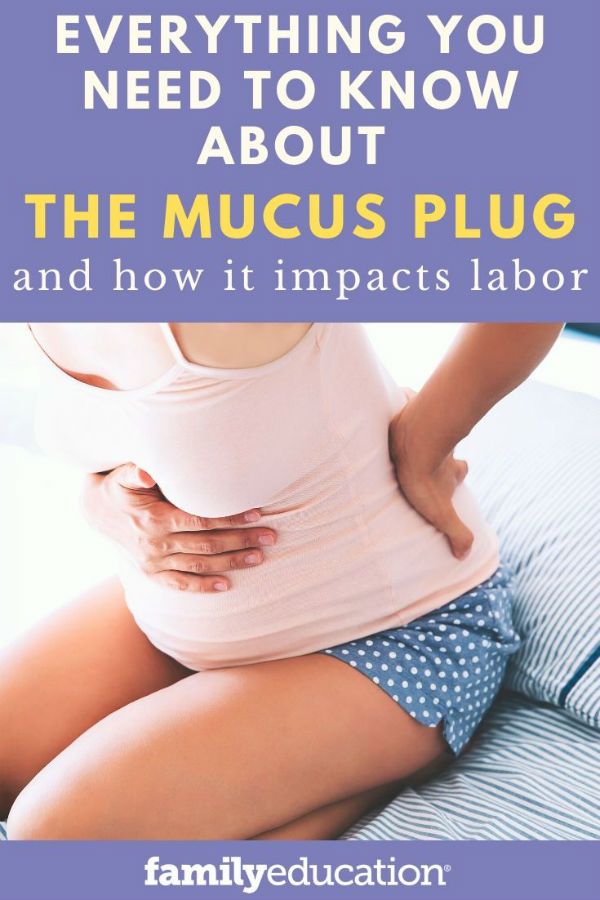

Vitamin K helps your baby’s blood clot and prevents serious bleeding. Babies do not get enough vitamin K naturally from their mother during pregnancy. Breast milk also does not provide babies with enough levels of vitamin K. This can result in vitamin K deficiency in newborns.

If your baby has vitamin K deficiency, they are at risk of developing a disease called Vitamin K Deficiency Bleeding, or VKDB. While VKDB is rare, it can be very serious as it can cause babies to bleed excessively and may cause them to bleed into their brain. This condition may result in brain damage and even death.

How is vitamin K given?

Vitamin K is usually given as a single injection in your baby’s leg muscle shortly after birth. If you prefer that your baby does not get an injection, they can have liquid vitamin K drops into their mouth. It is important to note that oral vitamin K drops are not absorbed as well by the body than injected vitamin K, so 3 doses of oral vitamin K are needed. The first dose is given at birth, the second at 3 to 5 days of age and the third when they are 4 weeks old.

The first dose is given at birth, the second at 3 to 5 days of age and the third when they are 4 weeks old.

Vitamin K injections are preferred over the oral drops for all babies. Some babies aren’t able to have oral vitamin K, such as if the mother was taking certain medications while pregnant, or if your baby is premature, unwell, taking antibiotics or has diarrhoea.

Can all babies have vitamin K?

Yes, all babies can have vitamin K. If your baby is premature or very small, they might need a smaller dose of vitamin K. You can discuss this with your doctor.

How much does vitamin K cost?

Vitamin K injections or drops are free. The cost is covered by the government for all babies born in Australia.

Does vitamin K have any side effects? What should I look out for?

Vitamin K in newborns is not associated with any side effects, and has been given to Australian babies for more than 30 years. Studies have investigated whether there is an association between injected vitamin K and childhood cancers. Doctors and scientists have concluded that vitamin K injections are safe and beneficial for babies, and that there is no link between vitamin K and childhood cancer.

Doctors and scientists have concluded that vitamin K injections are safe and beneficial for babies, and that there is no link between vitamin K and childhood cancer.

If your baby has not had a vitamin K injection or the full 3-dose course of vitamin K oral drops it is important that you look out for:

- unexplained bleeding or bruising

- showing signs of jaundice after they are 3 weeks old

If they show any of these symptoms, see your doctor or midwife immediately.

If your baby has liver problems, they may be at a higher risk of bleeding, even if they have had their recommended dose of vitamin K.

Does my baby need to have vitamin K?

It is your choice whether to give your baby vitamin K or not. However, giving vitamin K to your newborn is an easy way to prevent a very serious disease. Health authorities in Australia and throughout the world recommend giving vitamin K to all newborn babies — even babies who were born prematurely or are sick.

How do I get vitamin K for my baby?

During your pregnancy your doctor or midwife will talk to you about vitamin K, including the pros and cons of giving your baby vitamin K by injection or by mouth. Your doctor or midwife will then note this on your file. Your baby will receive vitamin K soon after birth by a doctor or a midwife, based on your decision.

If you have chosen to give your baby vitamin K by mouth then your baby will need to receive 2 more doses after the dose they receive at birth. The second dose can be given in hospital at the same time as your baby has their newborn screening test, or by your local doctor or healthcare worker. It is important to remember to arrange your baby’s third dose when they are 4 weeks old. This important final dose can also be given by your doctor or health care worker.

If you are having a home birth, be sure to discuss giving your baby vitamin K with your midwife. Homebirth midwives are required to have all essential equipment available for a planned home birth, including vitamin K injections.

Sources:

Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council (Vitamin K for Newborn Babies), South Australian Neonatal Medication Guidelines (Vitamin K), NSW Health (Having a baby - Labour and birth), SA Health (Planned Birth at Home in SA. 2018 Clinical Directive), The Royal Women Hospital Australia (Tests and Medicines for Newborn Babies)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: June 2022

Back To Top

Related pages

- Your baby in the first few days

- Baby's first 24 hours

Need more information?

Vitamin K for newborns | NHMRC

Vitamin K helps blood to clot and is essential in preventing serious bleeding in infants. Vitamin K deficiency bleeding can be prevented by the administration of vitamin K soon after birth. By the age of approximately six months, infants have built up their own supply of vitamin K.

Vitamin K deficiency bleeding can be prevented by the administration of vitamin K soon after birth. By the age of approximately six months, infants have built up their own supply of vitamin K.

Read more on NHMRC – National Health and Medical Research Council website

Vitamin K and newborn babies - Better Health Channel

With low levels of vitamin K, some babies can have severe bleeding into the brain, causing significant brain damage.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

At birth | Sharing Knowledge about Immunisation | SKAI

Most babies get two needles (injections) at birth. One is the hepatitis B vaccine and the other is a vitamin K injection. They are usually given in babies’ legs.

Read more on National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance (NCIRS) website

Children and vitamins

Very few kids actually need to take vitamin and mineral supplements, they can get everything they need from a balanced diet.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Vitamin and mineral supplements - what to know - Better Health Channel

Vitamin and mineral supplements are frequently misused and taken without professional advice. Find out more about vitamin and mineral supplements and where to get advice.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Vitamins & minerals for kids & teens | Raising Children Network

Children need vitamins and minerals for health and development. They can get vitamins and minerals by eating a variety of foods from the five food groups.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Itching during pregnancy

Mild itching is common in pregnancy because of the increased blood supply to the skin, but if the itching becomes severe it can be a sign of a liver condition called 'obstetric cholestasis'.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Baby's first 24 hours

There is a lot going on in the first 24 hours of your baby's life, so find out what you can expect.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

ACD A-Z of Skin - Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy

A-Z OF SKIN Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy BACK TO A-Z SEARCH What is it? Also known as … Recurrent Cholestasis of Pregnancy, Obstetric Cholestasis, Cholestasis of Pregnancy, Recurrent Jaundice of Pregnancy, Cholestatic Jaundice of Pregnancy, Idiopathic Jaundice of Pregnancy, Prurigo gravidarum, Icterus Gravidarum What is it? Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is a rare liver condition which causes an itchy skin

Read more on Australasian College of Dermatologists website

Pregnancy at week 40

Your baby will arrive very soon – if it hasn't already. Babies are rarely born on their due date and many go past 40 weeks.

Babies are rarely born on their due date and many go past 40 weeks.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

OKNeed further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Guidelines for vitamin K prophylaxis in newborns

Position statement

Podcast

Posted: Aug 16, 2018

The Canadian Paediatric Society gives permission to print single copies of this document from our website. For permission to reprint or reproduce multiple copies, please see our copyright policy.

A joint statement with the College of Family Physicians of Canada

Principal author(s)

Eugene Ng, Amanda D. Loewy, Fetus and Newborn Committee

Paediatr Child Health 2018, 23(6):394–397.

Abstract

Newborns are at risk for vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) caused by inadequate prenatal storage and deficiency of vitamin K in breast milk. Systematic review of evidence to date suggests that a single intramuscular (IM) injection of vitamin K at birth effectively prevents VKDB. Current scientific data suggest that single or repeated doses of oral (PO) vitamin K are less effective than IM vitamin K in preventing VKDB. The Canadian Paediatric Society and the College of Family Physicians of Canada recommend routine IM administration of a single dose of vitamin K at 0.5 mg to 1.0 mg to all newborns. Administering PO vitamin K (2.0 mg at birth, repeated at 2 to 4 and 6 to 8 weeks of age), should be confined to newborns whose parents decline IM vitamin K. Health care providers should clarify with parents that newborns are at increased risk of VKDB if such a regimen is chosen. Current evidence is insufficient to recommend routine intravenous vitamin K administration to preterm infants undergoing intensive care.

Health care providers should clarify with parents that newborns are at increased risk of VKDB if such a regimen is chosen. Current evidence is insufficient to recommend routine intravenous vitamin K administration to preterm infants undergoing intensive care.

Keywords: HDNB; Newborn; Prophylaxis; Vitamin K; VKDB

BACKGROUND

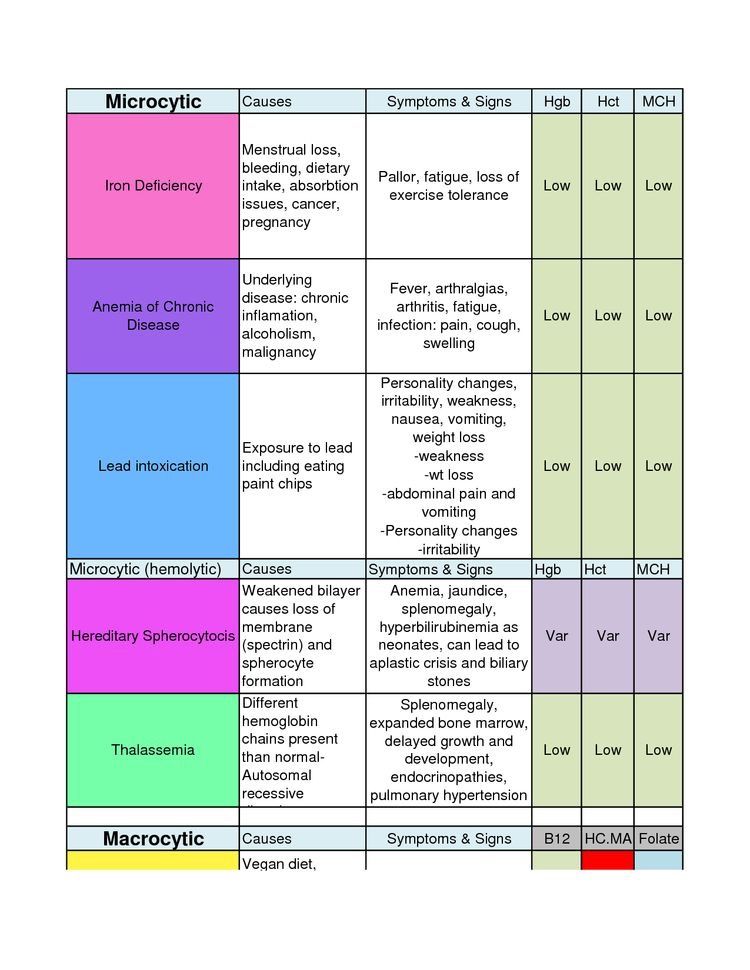

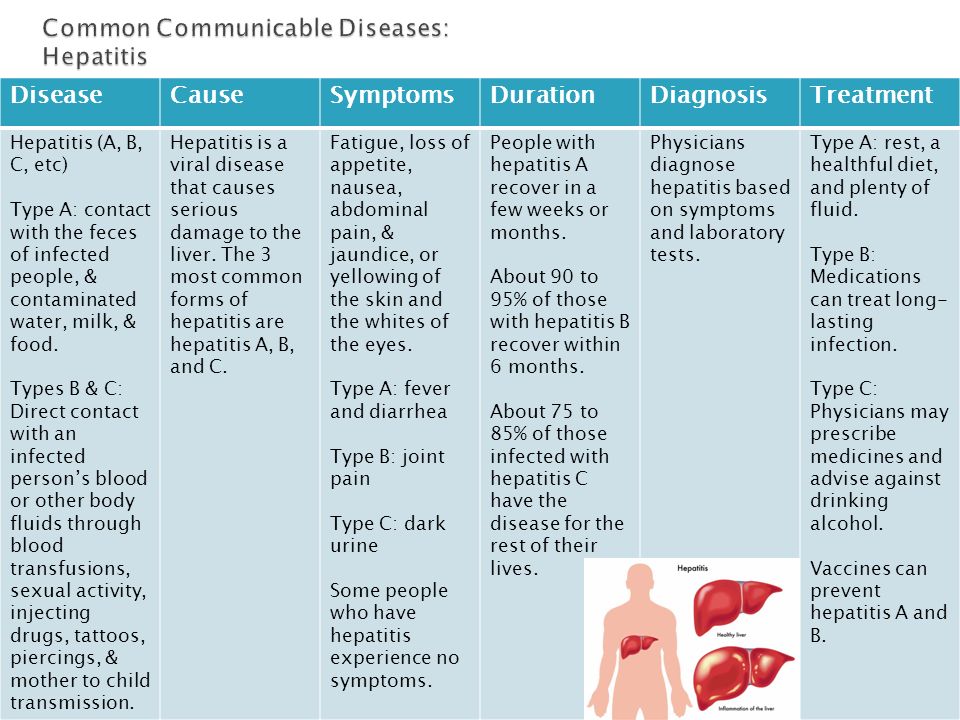

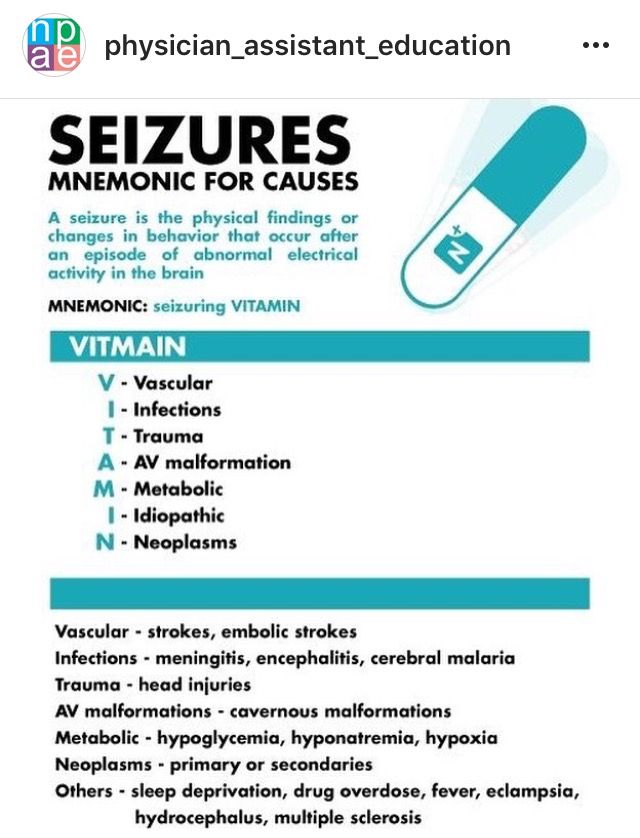

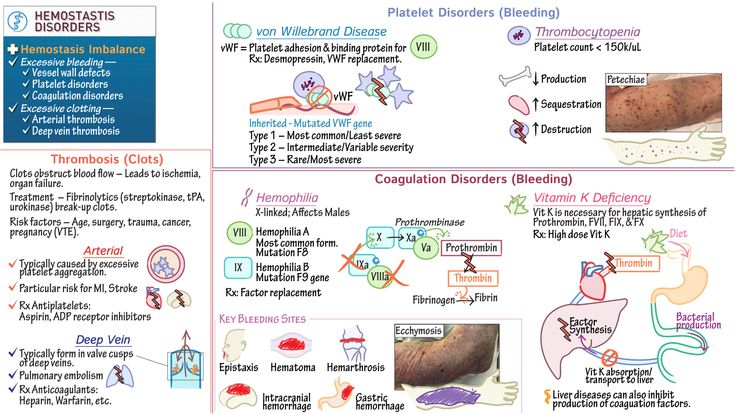

Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn (HDNB) was first identified over a century ago [1], and presents as unexpected bleeding, often with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, ecchymosis and, in many cases, intracranial hemorrhage. In newborns, HDNB is typically caused by vitamin K deficiency due to insufficient prenatal storage of vitamin K, combined with insufficient vitamin K in breast milk. Three types of vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) have been classified: early onset (occurring in the first 24 hours post-birth), classic (occurring at days 2 to 7) and late onset (at 2 to 12 weeks and up to 6 months of age). Early VKDB is commonly associated with maternal medications that inhibit vitamin K activity, such as antiepileptics. Classic VKDB is associated with low intake of vitamin K, and late VKDB with chronic malabsorption and low vitamin K intake [2].

Classic VKDB is associated with low intake of vitamin K, and late VKDB with chronic malabsorption and low vitamin K intake [2].

Since 1961, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has recommended that a single 0.5 mg to 1.0 mg dose of vitamin K be administered intramuscularly (IM) to all newborns shortly after birth to prevent VKDB [3]. The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) has recommended similar prophylactic treatment since 1988, but also proposed that 2.0 mg dose of oral (PO) vitamin K administered within 6 hours of birth, then repeated at 2 to 4 weeks and 6 to 8 weeks of age, was an acceptable alternative [4][5].

The AAP continues to advocate for sole use of IM vitamin K for all newborns. Their recommendation is based on a review of surveillance systems in four countries (Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), which suggested that administering vitamin K PO was less effective than by the IM route and may be associated with higher incidence of failure [6]. Further, a 1993 review from the AAP vitamin K Ad Hoc Task Force effectively dispelled concerns that IM administration of vitamin K was associated with childhood cancers such as leukemia [7].

Further, a 1993 review from the AAP vitamin K Ad Hoc Task Force effectively dispelled concerns that IM administration of vitamin K was associated with childhood cancers such as leukemia [7].

One recent practice review has confirmed that routine administration of IM vitamin K at birth effectively prevents VKDB [8]. However, while clinical decisions should always be based on the best evidence available, potential for harm to the infant must also be considered. Although no significant complications following 420,000 vitamin K injections in newborns have been reported [9], the psychological effects of procedural pain on infants (and parents) are unknown. Pain experienced during the neonatal period may have long-term effects [10][11]. The benefits of routine vitamin K administration have been demonstrated historically, but the most effective mode of delivery is yet to be fully determined [12]. By supporting the PO route for administering vitamin K and a formulation designed for parenteral use, the CPS recommendations of 1988 aimed to secure all the apparent benefits of vitamin K for newborns without incurring unnecessary pain [4][13]. Today, clinicians are more aware than ever of potential deleterious effects from early pain exposure and the need for strategies that minimize procedural pain in the neonate [14].

Today, clinicians are more aware than ever of potential deleterious effects from early pain exposure and the need for strategies that minimize procedural pain in the neonate [14].

PREVENTION OF EARLY AND CLASSIC VITAMIN K DEFICIENCY BLEEDING (VKDB)

To prevent early VKDB, the CPS previously recommended administering PO vitamin K to expectant mothers who are taking medications, notably antiepileptics, which impair vitamin K metabolism [4]. However, a systematic review of the literature on antiepileptic drug use in pregnancy by the American Academy of Neurology, published in 2009, concluded that evidence was insufficient to support vitamin K supplementation in the last weeks of pregnancy to reduce risk for VKDB [15].

Classic VKDB rarely occurs in newborns who have received parenteral vitamin K at birth [12]. Two clinical trials conducted in the 1960s [8][16] compared various doses of IM vitamin K with no prophylaxis on classic VKDB rates. Their results demonstrated clearly that vitamin K prophylaxis effectively reduces VKDB of any severity in the first week of life [17][18].

Their results demonstrated clearly that vitamin K prophylaxis effectively reduces VKDB of any severity in the first week of life [17][18].

PREVENTION OF LATE VKDB

Late (2 to 12 weeks and up to 6 months of age) VKDB, which occurs almost exclusively in breastfed infants, is a serious condition that manifests predominantly as intracranial hemorrhage [2]. No clinical trial to date has evaluated the effect of vitamin K on late VKDB. Epidemiological studies from a number of countries suggest that the incidence of late VKDB has been reduced significantly through implementation of vitamin K prophylaxis programs. PO vitamin K appears to be less effective, however, with higher failure rates compared with IM vitamin K [6][19]–[21].

In countries where PO administration was the primary form of prophylaxis, the incidence of late VKDB varied: from 1.6 per 100,000 infants (in the UK), 1.9 (Japan), 5.1 (Sweden) to 6. 4 (Switzerland) [19]–[22]. Some of these infants may also have had underlying disorders that affected vitamin K metabolism [23]. However, while the true failure rate of vitamin K may not be calculable when based primarily on surveys and surveillance studies, one study from Germany [19] estimated an occurrence of late VKDB cases—despite PO prophylaxis—of 1.4 per 100,000 infants. This failure rate followed a single PO dose, compared with a rate of 0.25 per 100,000 infants following IM administration. A similar study from the UK [20] showed a failure rate of 0.42 per 100,000 infants after administering a single PO dose of vitamin K. The relative risk for VKDB, when comparing PO versus IM vitamin K administration in these two studies, was 28.75 (95% CI 1.64 to 503.45) and 5.97 (95% CI 0.54 to 65.82), respectively [19][20].

4 (Switzerland) [19]–[22]. Some of these infants may also have had underlying disorders that affected vitamin K metabolism [23]. However, while the true failure rate of vitamin K may not be calculable when based primarily on surveys and surveillance studies, one study from Germany [19] estimated an occurrence of late VKDB cases—despite PO prophylaxis—of 1.4 per 100,000 infants. This failure rate followed a single PO dose, compared with a rate of 0.25 per 100,000 infants following IM administration. A similar study from the UK [20] showed a failure rate of 0.42 per 100,000 infants after administering a single PO dose of vitamin K. The relative risk for VKDB, when comparing PO versus IM vitamin K administration in these two studies, was 28.75 (95% CI 1.64 to 503.45) and 5.97 (95% CI 0.54 to 65.82), respectively [19][20].

In Canada, the specific incidence of late VKDB after PO or IM administration of vitamin K remains unknown. Reports from the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (CPSP) between 1997 and 2000 confirmed five cases of late VKDB, including one infant who received no vitamin K and two who received PO vitamin K, yielding an estimated incidence of 1 per 140,000 to 170,000 births [24].

Reports from the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (CPSP) between 1997 and 2000 confirmed five cases of late VKDB, including one infant who received no vitamin K and two who received PO vitamin K, yielding an estimated incidence of 1 per 140,000 to 170,000 births [24].

Without adequate vitamin K intake, an induced protein (PIVKA-II) becomes measurable in blood. This protein disappears by day five of life following PO administration of 1.0 mg of vitamin K at birth [25] and there appears to be no difference in these levels by day 5, whether vitamin K was administered PO or IM [26]. At 4 to 6 weeks of age, however, biochemical signs of vitamin K deficiency (vitamin K1 assay, noncarboxylated prothrombin) were observed in up to 19% of infants who received 2.0 mg of vitamin K PO at birth; by comparison, only 5.5% of infants who received 1.0 mg IM showed biochemical signs of vitamin K deficiency [27]. A mixed micelle formulation for oral delivery of vitamin K may be better absorbed, but one study showed that a higher incidence of vitamin K deficiency occurred when the vitamin was delivered PO, even in this formulation, compared with IM delivery [28]. The common limitation of these studies is a weak clinical correlation between the biochemical indicators and abnormal bleeding in infants.

The common limitation of these studies is a weak clinical correlation between the biochemical indicators and abnormal bleeding in infants.

In summary, the reported successes of using PO vitamin K prophylaxis in neonates [29] are consistently outweighed by data supporting the preferential use of IM over PO vitamin K in newborns. The reasons for additional benefits with IM delivery are not clear, but may pertain to better storage and slow release. Because risk for late VKDB is highest in exclusively breastfed infants, it has been suggested that administering PO vitamin K to lactating mothers could be beneficial [30][31]. One study from Denmark reported that a program of weekly PO vitamin K supplements for infants until they reached 3 months of age reduced the incidence of late VKDB, compared with a single PO dose [32]. However, a repeated PO dose regimen may not be practical because of lower patient compliance [33]. One epidemiological study, which included Australia, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, confirmed that three doses PO of 1 mg vitamin K were less effective than IM vitamin K prophylaxis in neonates, although a daily PO dose of 25 micrograms (from week 1 to 13), after an initial PO dose of 1 mg, may be as effective [6].

It is important to note that injected vitamin K does not completely protect infants from VKDB, especially if they are breastfed and their oral intake of vitamin K is low [34]. Health providers should consider the possibility of vitamin K deficiency at an early stage when evaluating any case of bleeding that occurs in the first six months of life. Appropriate therapy with vitamin K should be instituted when required.

The large number of newborn infants required to conduct a strong prospective study comparing the efficacy of IM versus PO vitamin K (with and without repeated doses) makes it unlikely that such a study will be carried out. Also, given the higher risk for late VKDB after a single PO dose of vitamin K administered post-birth, compared with vitamin K administered IM, and the 50% chance that infants with late VKDB will experience serious intracranial hemorrhage [27], delivering vitamin K by the IM route seems prudent. Repeated PO doses should be reserved for infants whose parents decline injected vitamin K at birth.

VITAMIN K PROPHYLAXIS FOR PRETERM INFANTS

Preterm infants are at higher risk for VKDB, due to hepatic immaturity, delayed gut colonization with microflora and other factors. However, recommendations for vitamin K prophylaxis at birth for preterm infants vary widely in terms of dosage and routes of administration [35], and there is inadequate evidence to support any one clinical practice.

Some centres administer intravenous (IV) vitamin K to preterm infants undergoing intensive care, to avoid the pain inflicted by injection. In one small study of 14 preterm infants [36], a single 0.3 mg/kg ± 0.1 mg/kg dose of IV vitamin K achieved plasma levels at 24 and 120 hours similar to that achieved by PO or IM doses of 1.5 mg [37].

In one clinical trial [38], preterm infants born less than 32 weeks gestational age were randomized to receive a single dose of vitamin K at birth of 0.5 mg IM, or 0.2 mg IM, or 0.2 mg by IV injection. Biochemical indices of vitamin K status were measured at birth, at 5 days and after 2 weeks of achieving full enteral feeds (>150 mL/kg/day). Serum vitamin K1 levels were above physiological norm for all infants on day 5. By day 25, serum vitamin K1 levels had decreased in all infants, but significantly more in those who received IV vitamin K at birth. The pharmacokinetic differences may relate to the lack of sustained vitamin K release from the muscle depot following IV administration, leading to more expedient clearance.

Biochemical indices of vitamin K status were measured at birth, at 5 days and after 2 weeks of achieving full enteral feeds (>150 mL/kg/day). Serum vitamin K1 levels were above physiological norm for all infants on day 5. By day 25, serum vitamin K1 levels had decreased in all infants, but significantly more in those who received IV vitamin K at birth. The pharmacokinetic differences may relate to the lack of sustained vitamin K release from the muscle depot following IV administration, leading to more expedient clearance.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Canadian Paediatric Society continues to recommend the routine administration of vitamin K to newborns, preferably by IM injection, to prevent vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB).

Administering one intramuscular (IM) dose of vitamin K (0.5 mg for infants weighing ≤1,500 g or 1.0 mg for infants weighing >1,500 g) routinely to all newborns within the first 6 hours post-birth and following initial stabilization and appropriate maternal/newborn interaction, is now the recommended best practice.

Implementing strategies that minimize the procedural pain associated with IM injections for all newborns is also recommended.

For parents who decline injection, counselling on the serious health risks of VKDB is advised. If they still decline, health care providers should recommend an oral (PO) dose of 2.0 mg vitamin K at the time of the first feeding, to be repeated at 2 to 4 and 6 to 8 weeks of age.

Health care providers should advise parents that:

- PO vitamin K is less effective than IM vitamin K for preventing VKDB

- Making sure their infant receives all follow-up doses is important, and

- Their infant remains at risk for developing late VKDB (potentially with intracranial hemorrhage) despite use of the parenteral form of vitamin K for PO administration, which is the only alternate formulation available at this time.

For preterm infants undergoing intensive care, limited data suggest that a single IV dose of 0.2 mg at birth may not be as protective against late VKDB as a 0. 2 mg or 0.5 mg dose of vitamin K delivered IM. Therefore, current evidence is insufficient to recommend routine use of IV vitamin K in this population.

2 mg or 0.5 mg dose of vitamin K delivered IM. Therefore, current evidence is insufficient to recommend routine use of IV vitamin K in this population.

An excellent resource for parents on vitamin K prophylaxis, from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, can be found at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/vitamink/index.html.

Acknowledgements

This statement was reviewed by the Community Paediatrics and Drug Therapy and Hazardous Substances Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society. Special thanks are due to members of the Maternity and Newborn Care Program Committee of the College of Family Physicians of Canada, who also reviewed this statement: William Ehman, Kate Miller, Sudha Koppula, Balbina Russillo, Amanda Pendergast, Michelle Abou-Khalil (resident rep), Kevin Desmarais and Heather Baxter.

CANADIAN PAEDIATRIC SOCIETY FETUS AND NEWBORN COMMITTEE

Members: Mireille Guillot MD, Leonora Hendson MD, Ann Jefferies MD (past Chair), Thierry Lacaze-Masmonteil MD (Chair), Brigitte Lemyre MD, Michael Narvey MD, Leigh Anne Newhook MD (Board Representative), Vibhuti Shah MD

Liaisons: Radha Chari MD, The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada; James Cummings MD, Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics; William Ehman MD, College of Family Physicians of Canada; Roxanne Laforge RN, Canadian Perinatal Programs Coalition; Chantal Nelson PhD, Public Health Agency of Canada; Eugene Ng MD, CPS Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Section; Doris Sawatzky-Dickson RN, Canadian Association of Neonatal Nurses

Principal authors: Eugene Ng MD, Canadian Paediatric Society; Amanda Loewy MD, College of Family Physicians of Canada

References

- Townsend CW.

The hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Arch Pediatr 1894;11:559–65.

The hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Arch Pediatr 1894;11:559–65. - Sutor AH. Vitamin K deficiency bleeding in infants and children. Semin Thromb Hemost 1995;21(3):317–29.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. Vitamin K compounds and the water-soluble analogues: Use in therapy and prophylaxis in pediatrics. Pediatrics 1961;28:501–7.

- Canadian Paediatric Society, Fetus and Newborn Committee. The use of vitamin K in the perinatal period. CMAJ 1988;139(2):127–30.

- McMillan D; Canadian Paediatric Society, Fetus and Newborn Committee. Routine administration of vitamin K to newborns. Paediatr Child Health 1997;2(6):429–31.

- Cornelissen M, von Kries R, Loughnan P, Schubiger G. Prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding: Efficacy of different multiple oral dose schedules of vitamin K. Eur J Pediatr 1997;156(2):126–30.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Vitamin K Ad Hoc Task Force. Controversies concerning vitamin K and the newborn.

Pediatrics 1993;91(5):1001–3.

Pediatrics 1993;91(5):1001–3. - Sankar MJ, Chandrasekaran A, Kumar P, Thukral A, Agarwal R, Paul VK. Vitamin K prophylaxis for prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding: A systematic review. J Perinatol 2016;36 (Suppl 1):S29–35.

- von Kries R. Vitamin K prophylaxis – a useful public health measure? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1992;6(1):7–13.

- Taddio A, Goldbach M, Ipp M, Stevens B, Koren G. Effect of neonatal circumcision on pain responses during vaccination in boys. Lancet 1995;345(8945):291–2.

- Taddio A, Katz J, Ilersich AL, Koren G. Effect of neonatal circumcision on pain response during subsequent routine vaccination. Lancet 1997;349(9052):599–603.

- Lane PA, Hathaway WE. Medical progress: Vitamin K in infancy. J Pediatr 1985;106(3):351–9.

- Murdoch LA. The use of vitamin K in the perinatal period. CMAJ 1989;140(1):13–4.

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Fetus and Newborn and Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine.

Prevention and management of procedural pain in the neonate: An update. Pediatrics 2016;137(2):e20154271.

Prevention and management of procedural pain in the neonate: An update. Pediatrics 2016;137(2):e20154271. - Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS, et al.; American Academy of Neurology; American Epilepsy Society. Practice parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy – focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Report of the quality standards subcommittee and therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2009;73(2):142–9.

- Puckett RM, Offringa M. Prophylactic vitamin K for vitamin K deficiency bleeding in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4):CD002776.

- Sutherland JM, Glueck HI, Gleser G. Hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Breast feeding as a necessary factor in the pathogenesis. Am J Dis Child 1967;113(5):524–33.

- Vietti TJ, Murphy TP, James JA, Pritchard JA. Observations on the prophylactic use of vitamin K in the newborn infant.

J Pediatr 1960;56:343–6.

J Pediatr 1960;56:343–6. - von Kries R, Gobel U. Vitamin K prophylaxis and vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in early infancy. Acta Paediatr 1992;81(9):655–7.

- McNinch AW, Tripp JH. Haemorrhagic disease of the newborn in the British Isles: Two year prospective study. BMJ 1991;303(6810):1105–9.

- Takahashi D, Shirahata A, Itoh S, Takahashi Y, Nishiguchi T, Matsuda Y. Vitamin K prophylaxis and late vitamin K deficiency bleeding in infants: Fifth nationwide survey in Japan. Pediatr Int 2011;53(6):897–901.

- Ekelund H. Late haemorrhagic disease in Sweden 1987–89. Acta Paediatr Scand 1991;80(10):966–8.

- von Kries R, Shearer MJ, Gobel U. Vitamin K in infancy. Eur J Pediatr 1988;147(2):106–12.

- McMillan DD, Grenier D, Medaglia A. Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program confirms low incidence of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn in Canada. Paediatr Child Health 2004;9(4):235–8.

- von Kries R, Kreppel S, Becker A, et al.

PIVKA-II levels after prophylactic vitamin K. Arch Dis Child 1987;62:938–40.

PIVKA-II levels after prophylactic vitamin K. Arch Dis Child 1987;62:938–40. - Jorgensen FS, Felding P, Vinther S, Andersen GE. Vitamin K to neonates. Peroral versus intramuscular administration. Acta Paediatr Scand 1991;80(3):304–7.

- Hathaway WE, Isarangkura PB, Mahasandana C, et al. Comparison of oral and parenteral vitamin K prophylaxis for prevention of late hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. J Pediatr 1991;119(3):461–4.

- Schubiger G, Tonz O, Gruter J, Shearer MJ. Vitamin K1 concentration in breastfed neonates after oral or intramuscular administration of a single dose of a new mixed-micellar preparation of phylloquinone. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1993;16(4):435–9.

- Clark FI, James EJ. Twenty-seven years of experience with oral vitamin K1 therapy in neonates. J Pediatr 1995;127(2):301–4.

- Nishiguchi T, Saga K, Sumimoto K, Okada K, Terao T. Vitamin K prophylaxis to prevent neonatal vitamin K deficient intracranial haemorrhage in Shizuoka prefecture.

Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103(11):1078–84.

Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103(11):1078–84. - Greer FR, Marshall SP, Foley AL, Suttie JW. Improving the vitamin K status of breastfeeding infants with maternal vitamin K supplements. Pediatrics 1997;99(1):88–92.

- Hansen KN, Ebbesen F. Neonatal vitamin K prophylaxis in Denmark: Three years’ experience with oral administration during the first three months of life compared with one oral administration at birth. Acta Paediatr 1996;85(10):1137–9.

- Croucher C, Azzopardi D. Compliance with recommendations for giving vitamin K to newborn infants. BMJ 1994;308(6933):894–5.

- Greer FR. Vitamin K in human milk – still not enough. Acta Paediatr 2004;93(4):449–50.

- Clarke P, Mitchell S. Vitamin K prophylaxis in preterm infants: Current practices. J Thromb Haemost 2003;1(2):384–6.

- Raith W, Fauler G, Pichler G, Muntean W. Plasma concentrations after intravenous administration of phylloquinone (vitamin K[1]) in preterm and sick neonates.

Thromb Res 2000;99(5):467–72.

Thromb Res 2000;99(5):467–72. - Stoeckel K, Joubert PH, Gruter J. Elimination half-life of vitamin K1 in neonates is longer than is generally assumed: Implications for the prophylaxis of haemorrhaghic disease of the newborn. Euro J Clin Pharmocol 1996;49(5):421–3.

- Clarke P, Mitchell SJ, Wynn R, et al. Vitamin K prophylaxis for preterm infants: A randomized, controlled trial of 3 regimens. Pediatrics 2006;118(6):e1657–66.

Disclaimer: The recommendations in this position statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. Internet addresses are current at time of publication.

groups A, C, B, the role of the vitamin complex for the body

Vitamins are organic trace elements necessary for the normal functioning of the body. We take them in different situations: after an illness or for prevention, in anticipation of a child or to maintain energy. From an early age, everyone knows that these substances are useful. We will figure out what importance each of the vitamins has and what are the consequences of their deficiency and excess.

From an early age, everyone knows that these substances are useful. We will figure out what importance each of the vitamins has and what are the consequences of their deficiency and excess.

Types of vitamins

The human body requires various organic compounds that serve as bioregulators. Only some substances the body produces on its own, while others need to be obtained from the external environment. This is the first big classification.

It is more common to distinguish species with letter designations. Modern vitaminology knows 13 items:

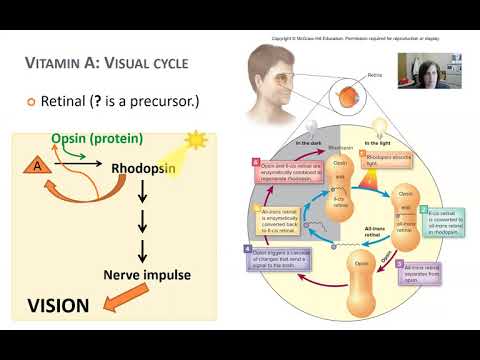

- A - retinol;

- B1 - thiamine;

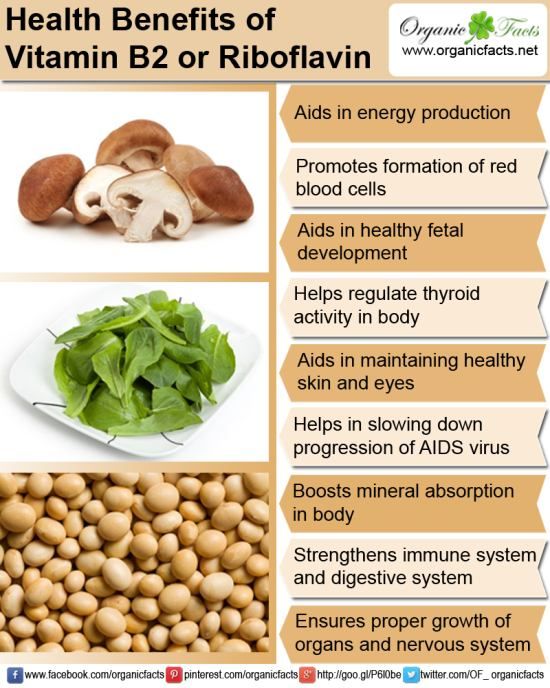

- B2 - riboflavin;

- B3 (PP) - niacin;

- B5 - pantothenic acid; nine0014

- B6 - pyridoxine or adermin;

- B7 - biotin;

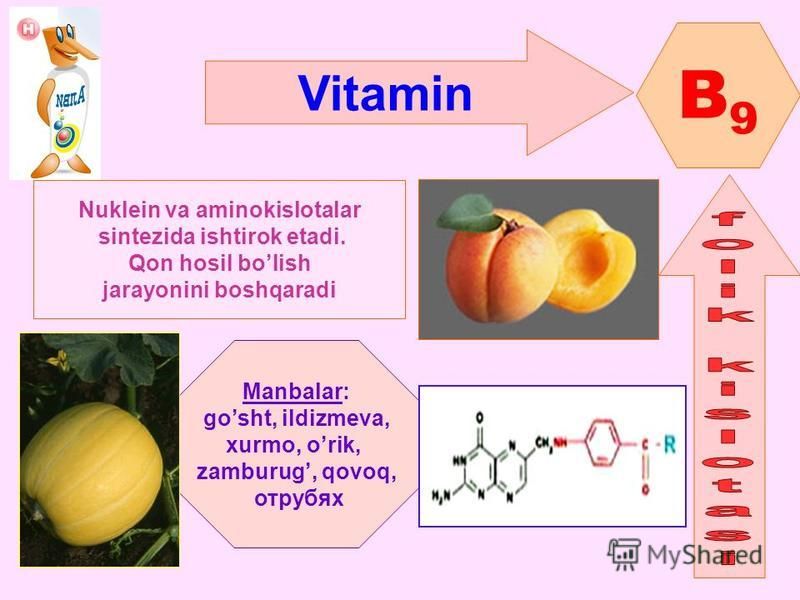

- B9 - folic acid;

- B12 - cyanocobalamin;

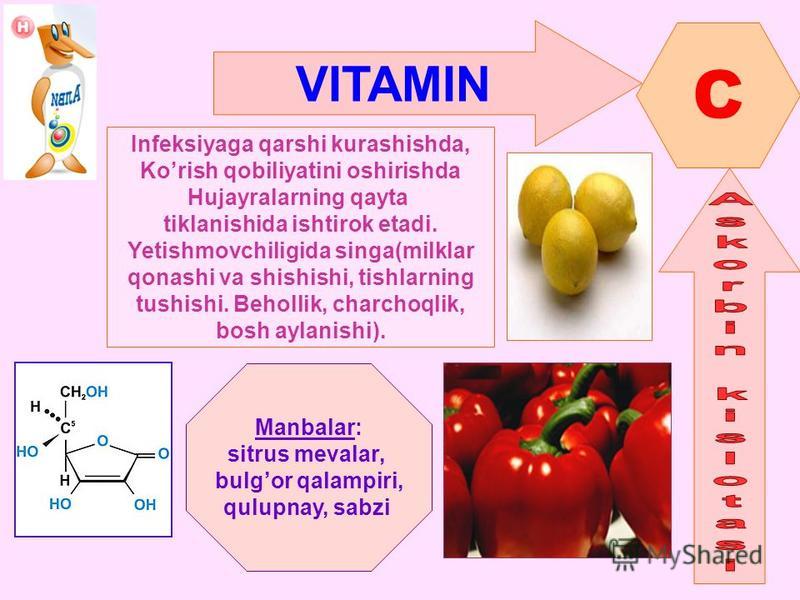

- C - ascorbic acid;

- D - calciferol;

- E - tocopherol;

- K - phylloquinone.

There are also vitamin-like substances - compounds that have similar properties. They are important for catalytic processes and are called nutritional factors. These include Group B elements not listed (B4, B8, B10). nine0003

They are important for catalytic processes and are called nutritional factors. These include Group B elements not listed (B4, B8, B10). nine0003

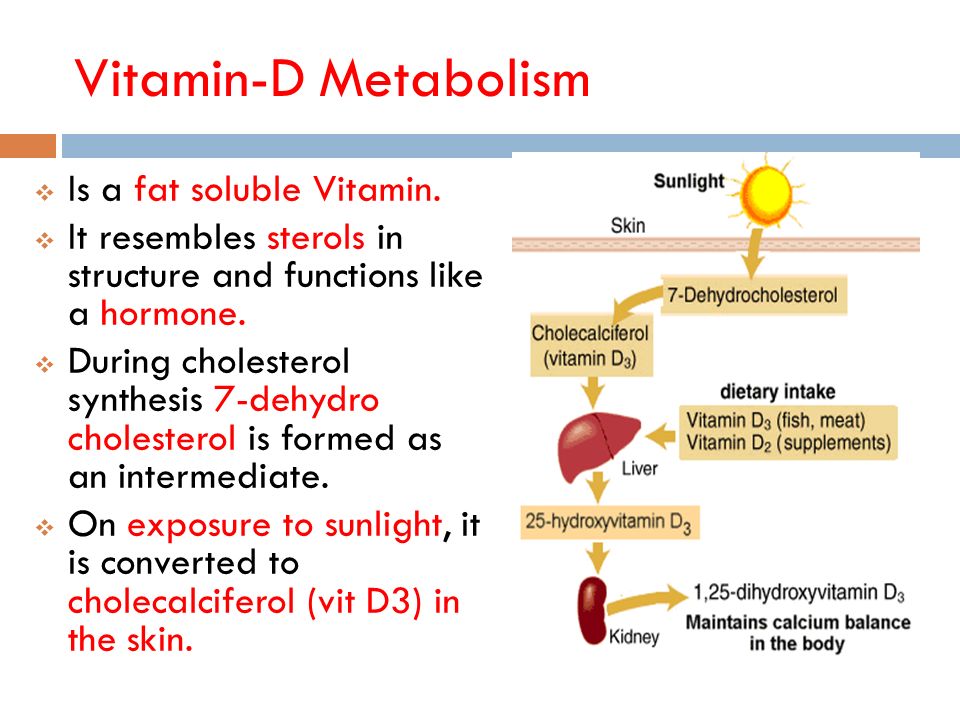

An important classification is by solubility. This sign is important for understanding the mechanism of assimilation, and at the same time - building a scheme for the consumption of mono- or multivitamins.

Water soluble vitamins

As the name implies, each of these substances dissolves in water. This means that when they enter the human body, they come into contact with the liquid, are processed and excreted. Their main properties:

- are actively involved in metabolism;

- do not cause overdose; nine0014

- require constant replenishment.

These include all elements of group B and ascorbic acid. Let's see why they are needed.

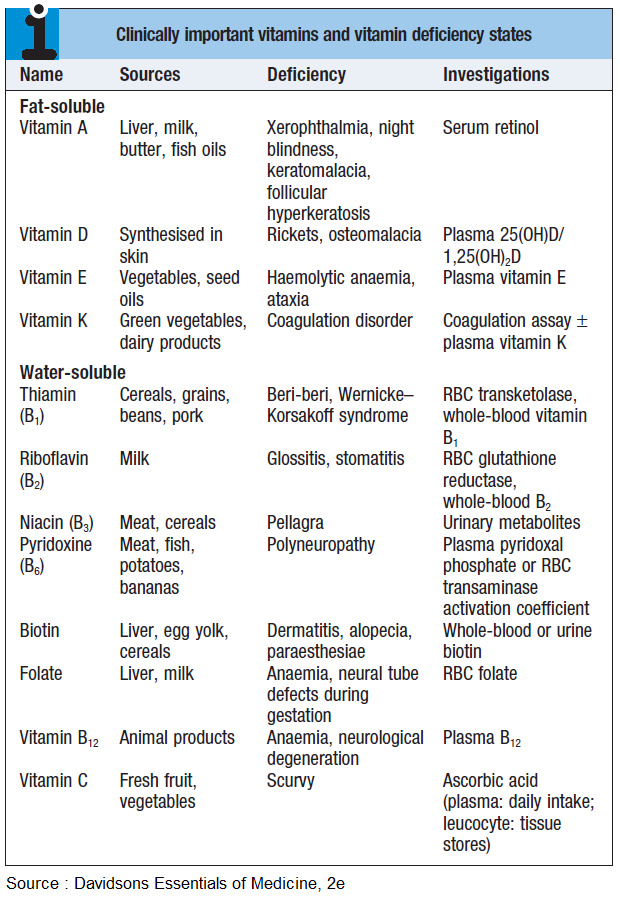

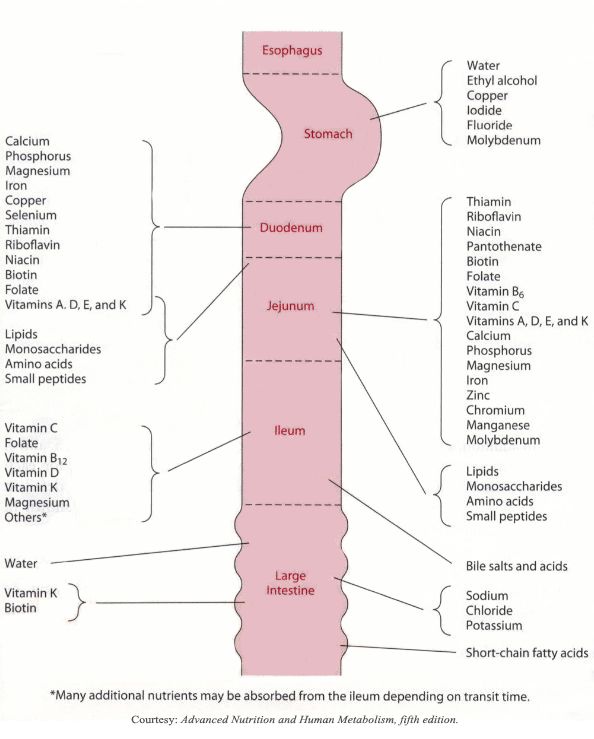

| Vitamin | Role |

| B1 | 1. 2. Carries out neuro-reflex regulation. nine0066 |

| B2 | 1. Regulation of redox processes. 2. Participation in macronutrient metabolism. |

| B3 | 1. Regulates blood circulation. 2. Maintains normal cholesterol levels. |

| B5 | 1. Stimulates the work of the adrenal glands. nine0003 2. Essential for building cages. |

| B6 | 1. Regulates metabolism in neurons. 2. Promotes the synthesis of neurotransmitters. |

| B7 | 1. Regulates carbohydrate metabolism. 2. Requires for cellular respiration. | nine0073

| B9 | Ensures the correct development of the fetus |

| B12 | 1. 2. Promotes blood clotting. |

| C | 1. Increases immunity. 2. Stimulates the endocrine system. |

Fat soluble vitamins

These compounds do not dissolve in water, only in fats. This means that it is easier for them to accumulate in the body. On the one hand, this is what they are good for - you can not be afraid of a shortage. On the other hand, there is a danger of overdose. Therefore, vitamin complexes are best taken only as directed by a doctor.

Fat-soluble substances include:

- retinol;

- calciferol;

- tocopherol; nine0013 phylloquinone.

Unsaturated fatty acids are sometimes included in this category. By analogy, they are called vitamins of group F, but this is not entirely correct.

Consider why adults and children need fat-soluble compounds.

| Vitamin | Role |

| A | 1. 2. Protects against abnormal cell division. 3. Ensures correct light perception. |

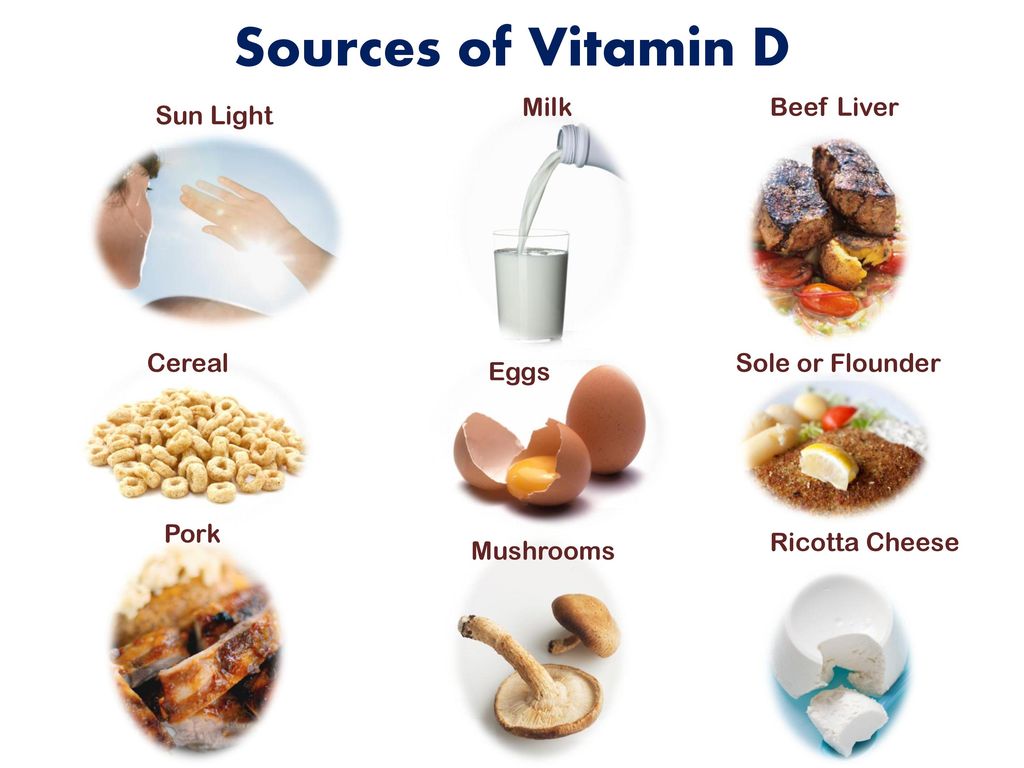

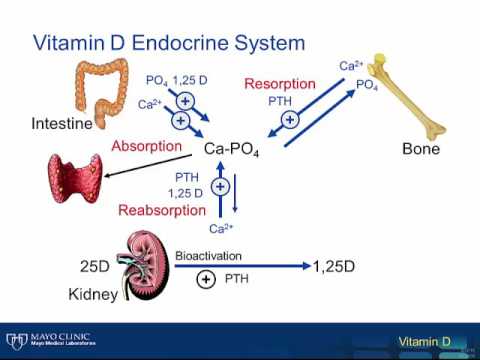

| D | 1. Prevents rickets. 2. Participates in calcium metabolism. |

| E | 1. It is a natural antioxidant. 2. Prevents degenerative processes in the musculoskeletal system. nine0003 3. Involved in protein synthesis. |

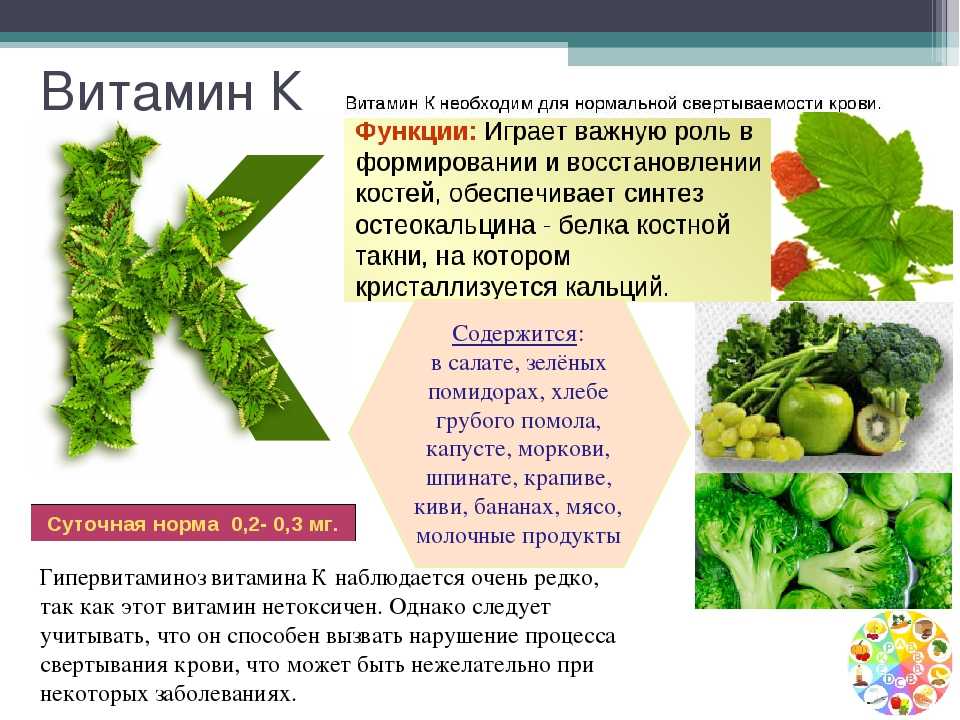

| K | 1. Requires for normal blood clotting. 2. Prevents the development of osteoporosis. |

The role of vitamins for human health

We found out the importance of each vitamin for normal human life. Each of them is indispensable for a particular body system (and often for several). Although these substances are not sources of energy, their lack leads to a general weakening of health. Describing their benefits in general, we especially note:

Describing their benefits in general, we especially note:

- participation in the metabolism of proteins, fats and carbohydrates;

- maintenance of immunity;

- regulation of oxygen supply to cells;

- stimulation of individual systems;

- prevention of most diseases;

- natural prevention of tumors;

- ensuring normal reactions of the nervous system.

They are indispensable during the period of body growth, hormonal changes, pregnancy. In conditions of stress, morbidity and increased loads, they help maintain health and prevent premature aging of the body. nine0003

Natural sources of vitamins

Water-soluble vitamins are excreted regularly in the urine. Deficiency of these beneficial compounds develops more often. Of these, only niacin is produced by the body (with the participation of intestinal microflora).

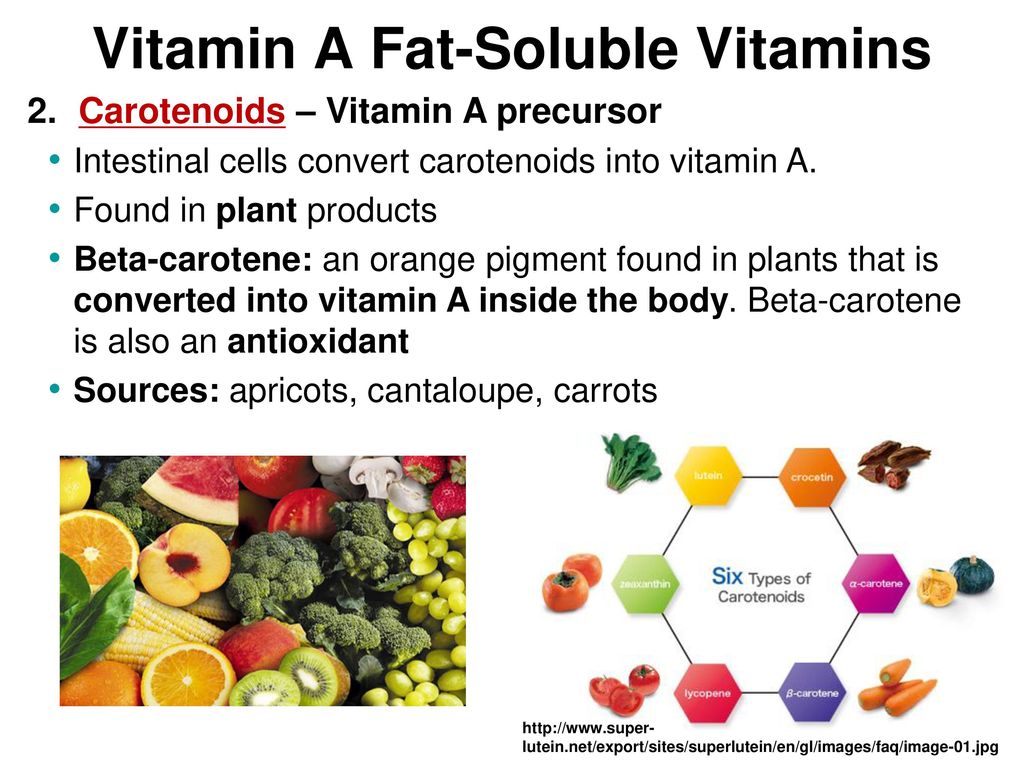

From fat-soluble, a person is able to synthesize calciferol (in the presence of sufficient sunlight) and phylloquinone. Retinol is formed in the body from beta-carotene, so its intake is a prerequisite for internal synthesis. nine0003

Retinol is formed in the body from beta-carotene, so its intake is a prerequisite for internal synthesis. nine0003

All other useful substances with sufficient nutrition can be obtained from food. This includes not only fruits and vegetables, as is commonly believed, but also legumes, cereals, mushrooms, meat and offal, fish, milk, eggs. Each product may contain several required compounds.

Daily requirement for vitamins (tables)

It is necessary not just to get these substances, but in a certain amount. Excess is undesirable, as well as deficiency. There are daily norms for each vitamin, allowing you to choose the optimal proportions of nutrition. nine0003

Norm for a man per day

| Vitamin | Age | |||

| 9-13 years old | 14-18 years old | 19-70 years old | Over 70 years old | |

| A (µg) | 600 | 900 | ||

| B1 (mg) | nine0061 1.2 | |||

| B2 (mg) | 0.9 | 1.3 | ||

| B3 (mg) | 12 | 16 | ||

| B6 (mg) | 1 | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

| B9 (µg) nine0066 | 300 | 400 | ||

| B12 (µg) | 1.8 | 2.4 | ||

| C (mg) | 45 | 75 | 90 | |

| D (units) | 600 | 800 | ||

| E (mg) | 11 | 15 | ||

| K (µg) | 60 | 75 | 120 | |

Norm for a woman per day

| Vitamin | Age | |||

| 9-13 years old | 14-18 years old | nine0002 19-70 years old | Over 70 years old | |

| A (µg) | 600 | 700 | ||

| B1 (mg) | 0. | 1 | 1.1 | |

| B2 (mg) | 0.9 | 1 | 1.1 | |

| B3 (mg) | 12 | 14 | ||

| B6 (mg) | 1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| B9 (µg) | 300 | 400 | ||

| B12 (µg) | 1.8 | nine0361 |||

| C (mg) | 45 | 65 | 75 | |

| D (units) | 600 | 800 | ||

| E (mg) | 11 | 15 | ||

| K (µg) | 60 nine0066 | 75 | 90 | |

Norm for a child per day

| Vitamin | Age | |||

| 0-6 months | 7-12 months | 1-3 years | 4-8 years | |

| A (µg) | 400 | nine0061 300 | 400 | |

| B1 (mg) | 0. | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| B2 (mg) | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| B3 (mg) | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| B6 (mg) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| B9 (µg) | 65 | 80 | 150 | 200 |

| B12 (µg) | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| C (mg) | 40 | 50 | 15 | 25 |

| D (units) | 400 | 600 nine0066 | ||

| E (mg) | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| K (µg) | 2. | 2.5 | 30 | 55 |

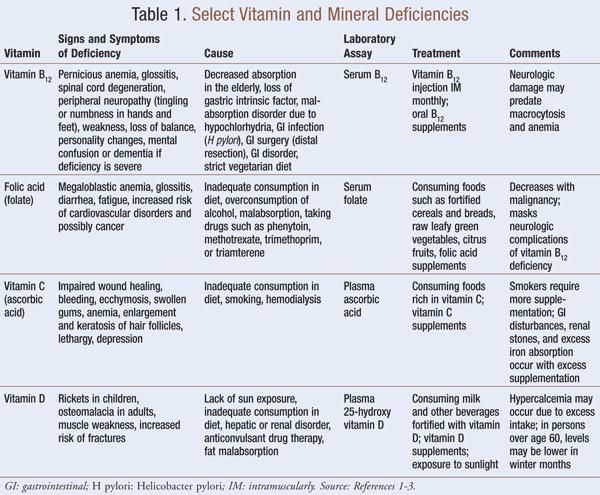

Hypovitaminosis

Hypovitaminosis is a group of pathological conditions caused by a deficiency of one or more vitamins. Types of hypovitaminosis are distinguished according to the lack of what substance they are caused by:

- retinol - night blindness;

- thiamine - take-take;

- niacin - pellagra;

- cyanocobalamin - pernicious anemia;

- ascorbic acid - scurvy;

- calciferol - rickets.

They usually have an unbalanced diet behind them. It can be caused by external conditions (for example, a lack of vegetables and fruits in winter) or a person’s wrong approach to his diet. Selective nutrition often leads to a deficiency of certain compounds. nine0003

Sometimes foods may not contain enough of them. The only thing that can be done in this case is to additionally take mono- or multivitamins.

Avitaminosis

Avitaminosis is a serious condition that occurs against the background of a systematic lack of vitamins. It is usually used as a synonym for hypovitaminosis (which is a mistake), in its true meaning it is a rather rare diagnosis.

Exogenous avitaminosis (caused by starvation) is rare in developed countries. More often endogenous, due to:

- impaired absorption mechanisms;

- inability to digest;

- metabolic disorders, due to which vitamins are destroyed before they reach the tissues.

If the body does not receive the necessary compounds for a long time, irreversible changes occur in it. On his own, a person can do little to prevent this: adjusting the diet and taking vitamin complexes will not work. This requires treatment of the underlying disease. Otherwise, not a single vitamin preparation will be absorbed. nine0003

Hypervitaminosis

Although vitamins are useful and irreplaceable, their excessive consumption leads to intoxication. Water-soluble in this regard is safer: they do not have time to accumulate in such a volume as to poison the body. But fat-soluble ones can do it:

Water-soluble in this regard is safer: they do not have time to accumulate in such a volume as to poison the body. But fat-soluble ones can do it:

- retinol increases intracranial pressure;

- calciferol causes excessive calcium deposits;

- tocopherol weakens bones.

Why bring yourself to such a state? This usually happens unconsciously. Some take multivitamins without thinking that they contain several compounds at once. This means that by filling the deficit of one, you can simultaneously create an overabundance of the other. nine0003

In this regard, monovitamin preparations are safer. Vitamin complexes are best taken as directed by a doctor if multiple hypovitaminosis is diagnosed.

Conclusion

A modern person does not experience difficulties in obtaining food, therefore, he can get all the necessary substances naturally. In periods when health needs additional support, a range of pharmacies comes to the rescue.

It is not enough for the buyer to know what vitamins are and what they are for. It is important to be able to assess the daily requirement, make up for the deficiency and prevent overdose. nine0003

Vitamin K: The Complete Guide to Vitamin K

Contents:

➦ Nutrient Features

➦ Effects of Vitamin K on the Body

➦ Indications for Vitamin K

➦ Top 3 9003 Vitamin K Supplements changes caused in the body by a deficiency of vitamin K?

➦ How much vitamin K should I take?

➦ Where is vitamin K found?

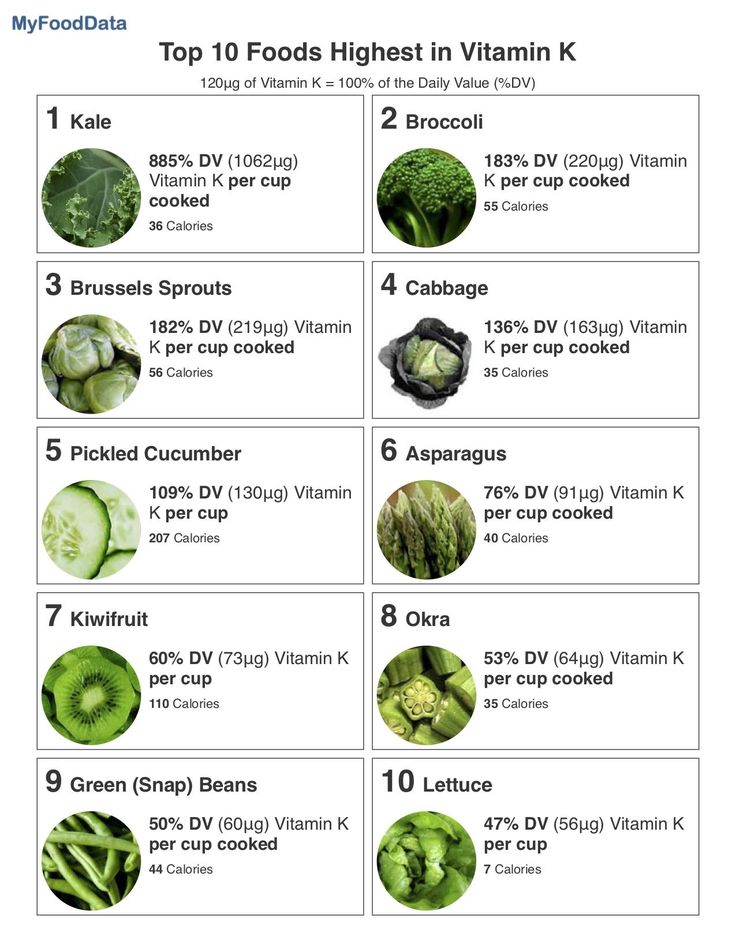

➦ Vitamin K in foods

➦ Vitamin K in supplements

➦ Vitamin K antagonists

➦ Side effects of vitamin K

➦ What to look for when choosing vitamin K

➦ Frequently asked questions about vitamin K

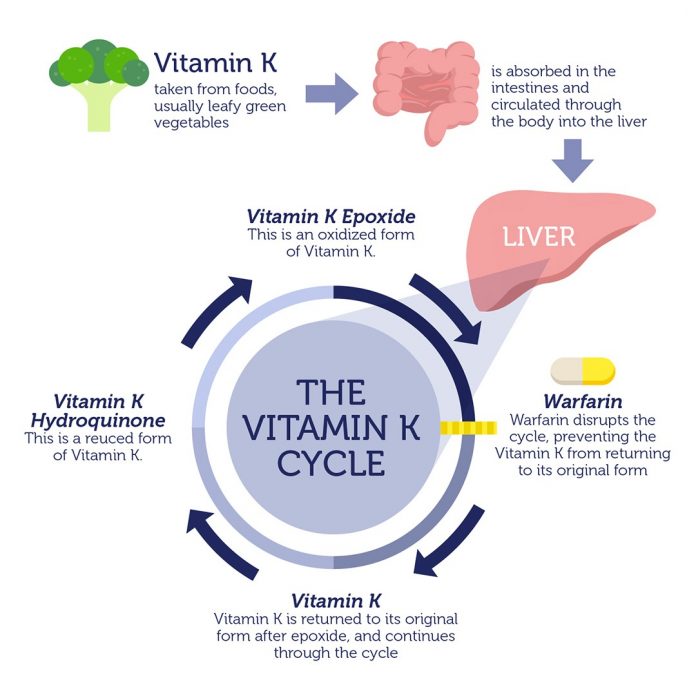

Vitamin K is called a fat-soluble vitamin, one of the 6 most important for proper functioning of our body. Its most famous function is the regulation of blood clotting, which is why it is called the "clotting vitamin". By the way, the letter K in its name comes from the German word koagulation, which means coagulation. nine1099

By the way, the letter K in its name comes from the German word koagulation, which means coagulation. nine1099

Nutrient specifics

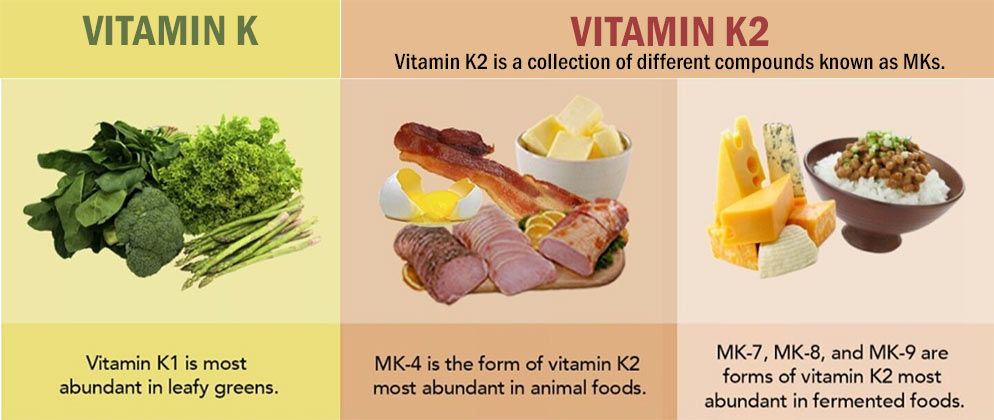

Vitamin K exists in two forms:

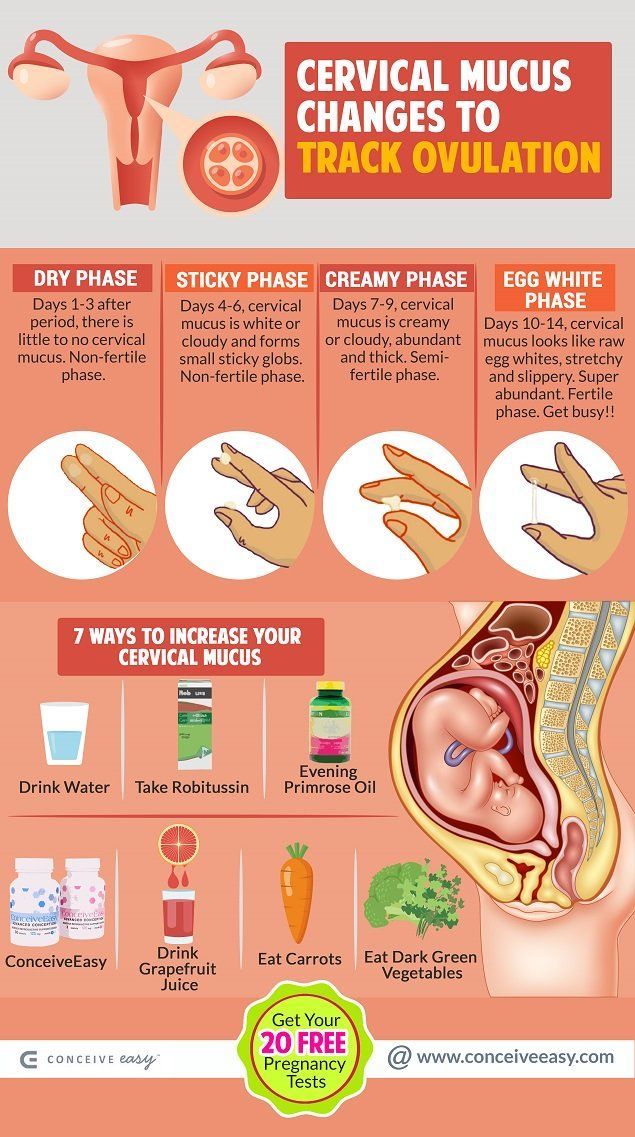

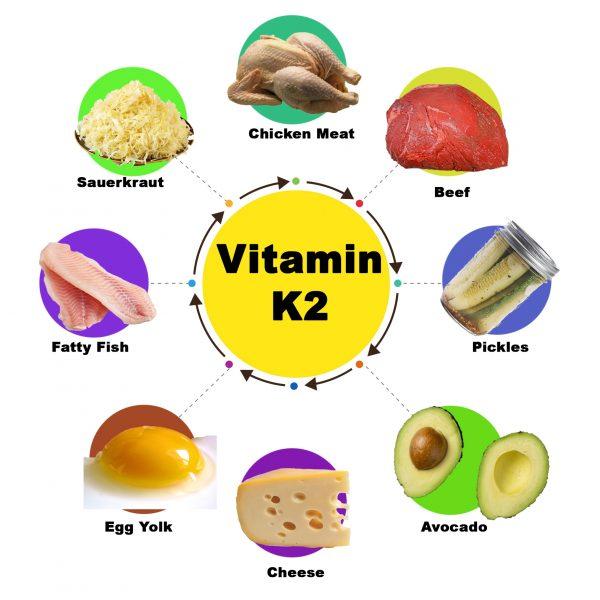

➦ Phylloquinone or vitamin K1 - found in plant foods, mainly in green leafy vegetables.

➦ Menaquinone or vitamin K2 - synthesized from phylloquinone by the intestinal microflora of humans, animals and birds that eat herbs and cereals, therefore it is present in animal products.

➦ Menadione or vitamin K3 is a synthetic vitamin, an artificial analogue of natural representatives of the group of compounds with K-vitamin activity. nine0003

Vitamin K has several natural forms (vitamers), the most studied of which are MK-4, 5, 6, 7 and 13. In general, they are similar in their action and differ in the activity of absorption in the intestine.

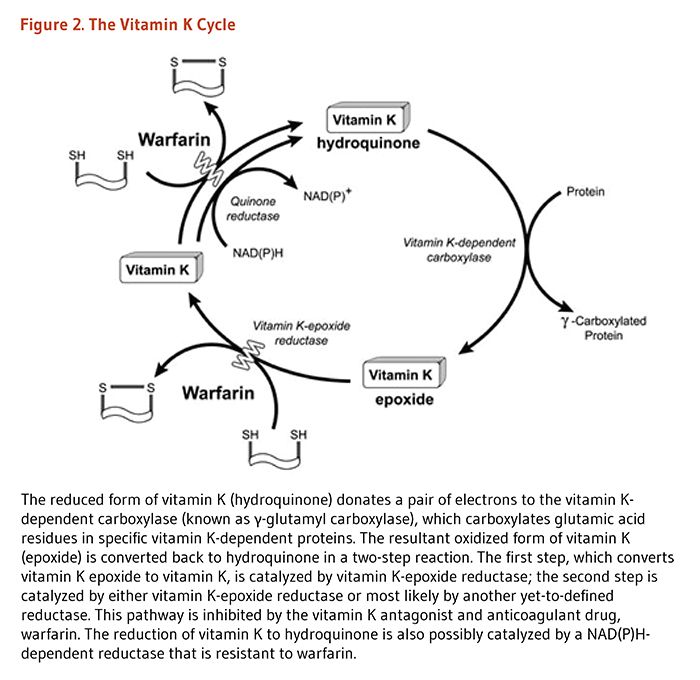

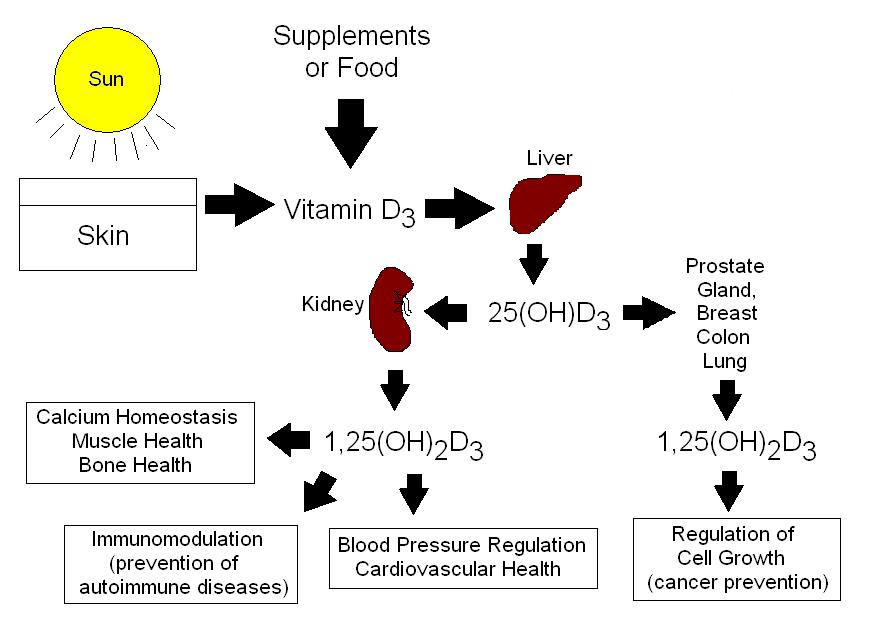

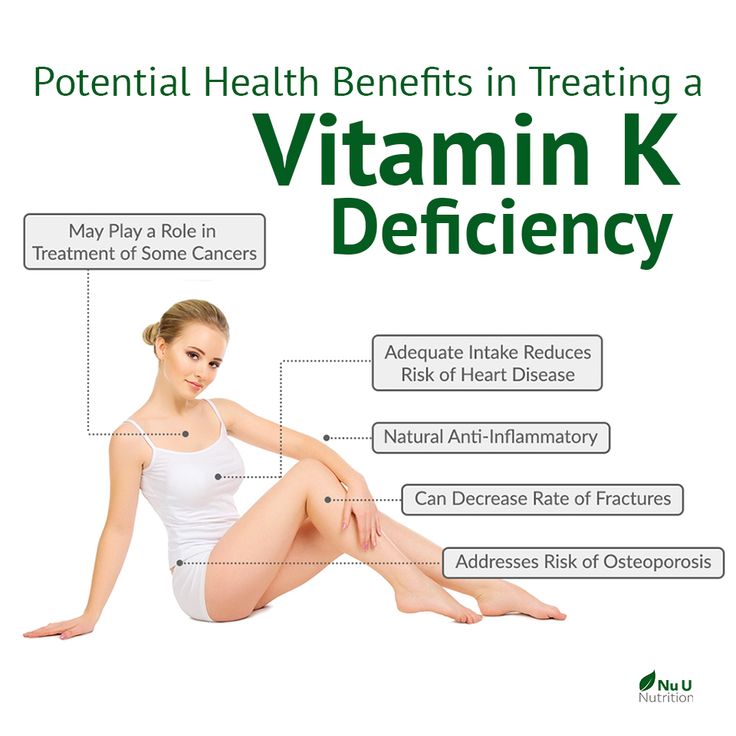

The effect of vitamin K on the body

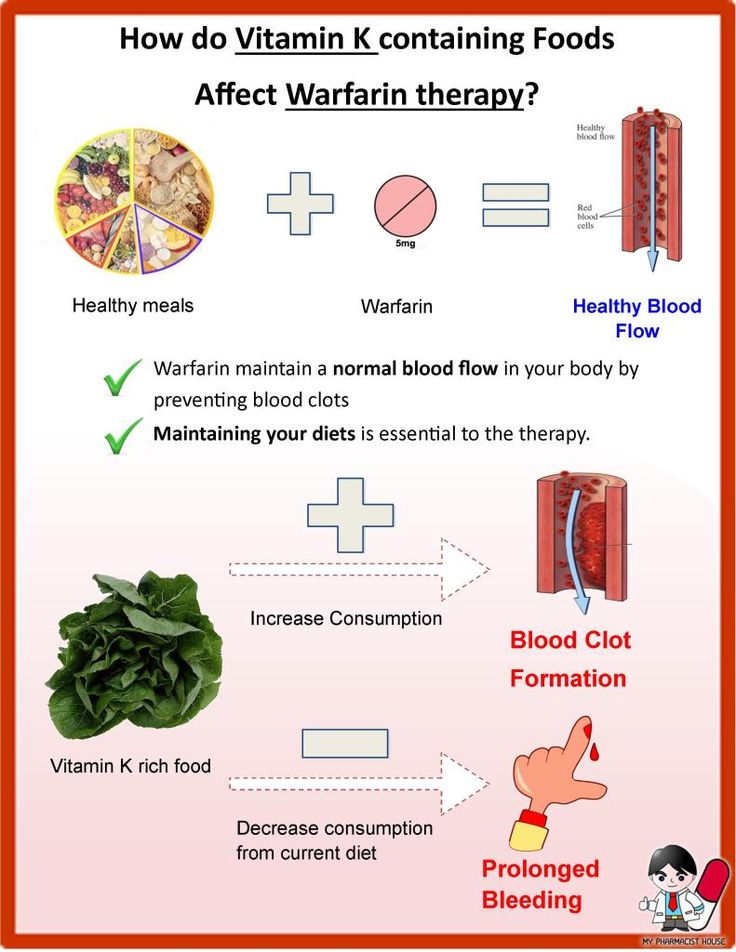

Vitamin K ensures that platelets stick together and form a blood clot, which becomes a natural physical barrier to loss of the body's life force, thus playing a key role in blood clotting. Failures in this mechanism can be potentially life-threatening. nine0003

Failures in this mechanism can be potentially life-threatening. nine0003

It was thanks to this property that the micronutrient was discovered by the Danish scientist Henrik Dam. In 1923, he observed chickens receiving food poor in cholesterol. Several weeks of such nutrition led to multiple hemorrhages in the muscles and other tissues of birds, and during the experiments a substance was found that affects blood clotting.

The second important function of vitamin K is participation in the mineralization of bone tissue, in particular, in the fixation of calcium on the bones. Providing the synthesis of bone tissue protein, on which calcium crystallizes, vitamin K is involved in the formation and restoration of bones. nine0003

The biological role of vitamin K in the body:

- improves the strength of the walls of blood vessels, reducing the risk of blood loss in injuries

- increases endurance to aerobic exercise and stimulates energy production

- normalizes the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract and muscle function 900 kidneys

- has an anti-inflammatory effect

- participates in the synthesis of sphingolipids, which are part of the membranes of nerve cells and sheaths of nerve fibers

- increases insulin production

- exhibits immunomodulatory properties

- protects cells from oxidative damage

Indications for use of vitamin K

Given its important role in blood clotting, it is often prescribed during pregnancy to prevent uterine bleeding. With the ability to increase insulin resistance, this nutrient should be included in the diet of people with diabetes. Due to its anti-inflammatory action, it suppresses the development of rheumatoid arthritis and improves the condition of the joints, therefore it is important for the elderly. nine0003

With the ability to increase insulin resistance, this nutrient should be included in the diet of people with diabetes. Due to its anti-inflammatory action, it suppresses the development of rheumatoid arthritis and improves the condition of the joints, therefore it is important for the elderly. nine0003

In case of reduced blood clotting caused by hypovitaminosis or beriberi K, this vitamin can be prescribed in the form of drops, tablets and injections. For example, an indication for the use of Kanavit is the prevention and treatment of bleeding due to clotting disorders, to inhibit blood clotting factors of various etiologies.

Vitamin K helps maintain the health of blood vessels and the heart, as it prevents the deposition of calcium in the vascular walls and on atherosclerotic plaques. By preventing mineralization of the arteries, it reduces the risk of heart disease, stroke, and heart attack. In a Dutch observational study of 564 postmenopausal women, dietary intake of menaquinone was inversely associated with coronary calcification. nine0003

nine0003

Taking part in the formation of the bone protein osteocalcin, vitamin K intake is important in fractures. It delays the onset of osteoporosis, so it is essential for menopausal women. These data were obtained in 2006 from a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of vitamin K supplementation on bone mineral density and fracture. Most of the trials have been conducted in Japan with postmenopausal women. 12 out of 13 trials found that phytonadione or MK-4 supplementation improved bone mineral density. Today, forms of vitamin K are used as a general therapeutic agent for the treatment of osteoporosis in Japan and other countries. nine0003

One study showed a beneficial effect of this nutrient on cognitive function: healthy people over 70 years of age with the highest blood levels of vitamin K1 showed the highest verbal performance of episodic memory.

Menaquinone-7 prevents tissue calcification, positively affecting the elasticity and firmness of the skin, slowing down the appearance of wrinkles and ptosis. By participating in redox and metabolic processes, it improves cellular respiration, providing a young and healthy appearance of the skin. nine0003

By participating in redox and metabolic processes, it improves cellular respiration, providing a young and healthy appearance of the skin. nine0003

A number of clinical studies have shown that taking vitamin K prevents the formation of cancer cells and even promotes their self-destruction, reducing the risk of developing cancer.

In collaboration with the Institute for Cardiovascular Research in Maastricht (Netherlands), from March 12 to April 11, 2020, British scientists have established a link between vitamin K deficiency and the development of severe forms of coronavirus. This study showed that a significant number of patients with severe forms of Covid-19vitamin K deficiency has been observed. cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, ulcerative colitis and short bowel syndrome

To prevent hemorrhagic disease of the newborn, pediatricians recommend taking 2 mg of vitamin K by mouth at birth and weekly while the baby is breastfeeding.

Top 3 Vitamin K Supplements

What changes does vitamin K deficiency cause in the body?

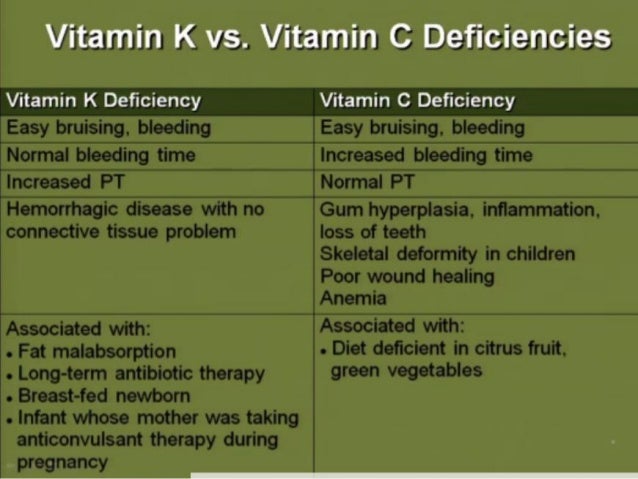

Prolonged deficiency of vitamin K leads to a decrease in prothrombin activity, causes poor blood clotting and can provoke extensive bleeding, crystallization and blockage of blood vessels. nine1099

Because vitamin K is essential for the carboxylation of osteocalcin in bone, a deficiency can affect mineralization, resulting in brittle bones, rheumatoid joint pain, osteoporosis, and other adverse effects.

Low vitamin K levels at birth are a cause of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. In addition, infants cannot produce endogenous synthesis because their intestines are sterile at birth. This is manifested by digestive bleeding, and in severe forms - cerebral bleeding. It is observed only with exclusive breastfeeding. nine0003

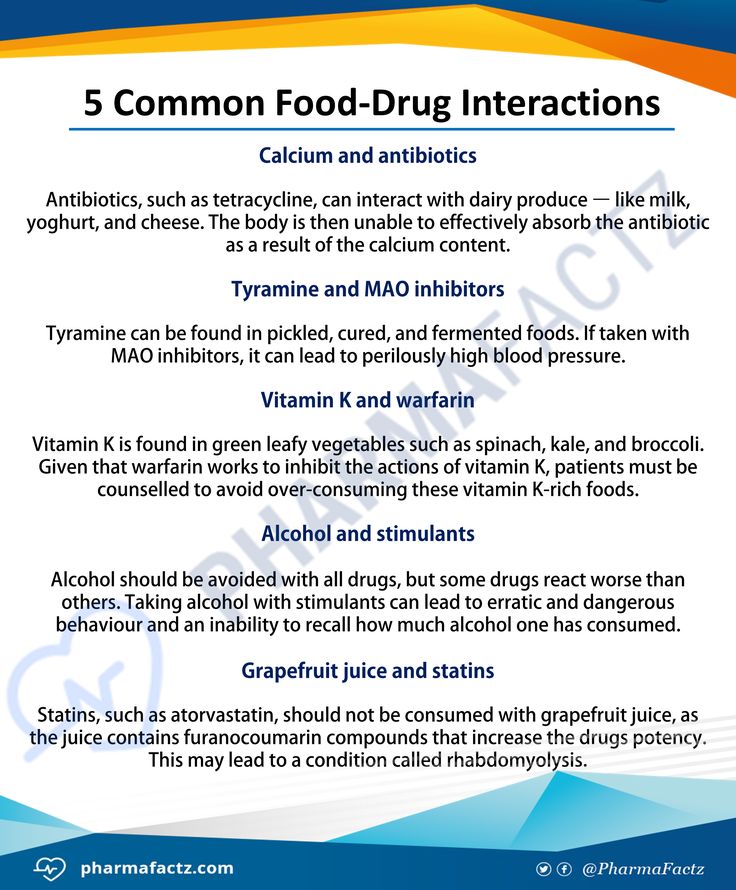

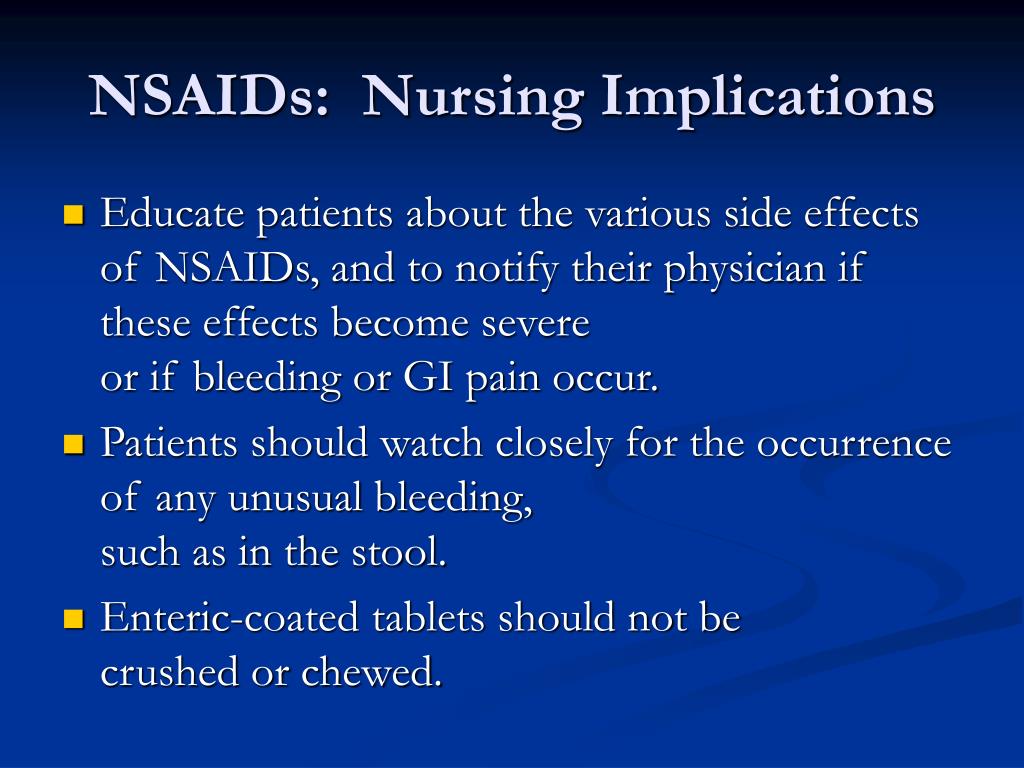

Other causes of this nutrient deficiency include medications that aim to block coagulation: oral anticoagulants or VKAs. The desired effect is an improvement in blood flow, the main complication is an increased risk of bleeding. The reason for the deficiency may be interaction with antibiotics (cephalosporin), antiepileptic drugs, aspirin, iron.

The desired effect is an improvement in blood flow, the main complication is an increased risk of bleeding. The reason for the deficiency may be interaction with antibiotics (cephalosporin), antiepileptic drugs, aspirin, iron.

There is no real interference between VKA and vitamin K in our diet. However, it is currently recommended that patients taking vitamin K supplements limit their intake of foods rich in this nutrient to one serving per day (particularly kale, spinach, broccoli, avocado) and vary as much as possible. Green tea can be consumed regularly, but in small doses and only once a day. nine0003

The classic symptoms of vitamin K deficiency are:

✔ nosebleeds;

✔ hemorrhages;

✔ long-term non-healing skin lesions;

✔ increased fatigue;

✔ osteoporosis;

✔ violation of the digestive tract.

If these signs appear, it is recommended to contact a specialist to undergo an examination for vitamin K levels. If a nutrient deficiency is established, it can be replenished by taking special supplements and vitamin complexes. nine0003

If a nutrient deficiency is established, it can be replenished by taking special supplements and vitamin complexes. nine0003

How much vitamin K to take?

Many doctors believe that with a balanced diet, our body can fully satisfy its needs for this nutrient. However, popular Canadian TV and radio health expert Dr. Kate Rem-Blue, in his famous article "Vitamin K2 and the Calcium Paradox", claims that in the modern diet, a person consumes only about 10 percent of vitamin K and "this is completely insufficient to increase the density bones and improved heart health." nine0003

Unfortunately, the main dietary myth of the 20th century about the dangers of animal fats for blood vessels led to the fact that vitamin K2 began to be expelled from the diet. Skimmed dairy products were welcomed, the replacement of butter with margarine. Animals and birds were no longer fed with green mass, being transferred to feeds devoid of vitamin K1, from which menaquinones are synthesized. All these are factors that provoke a nutrient deficiency in the body.

All these are factors that provoke a nutrient deficiency in the body.

Vitamin K is absorbed in the first part of the small intestine through lipid vesicles. The degree of absorption ranges from 20 to 70%. According to studies, in healthy people, the concentration of phylloquinone in fasting plasma ranges from 0.29up to 2.64 nmol/l. However, it is not clear whether this measure can be used to quantify micronutrient status. Individuals with plasma phylloquinone concentrations slightly below the normal range do not show clinical signs of deficiency, possibly because intestinal menaquinones compensate for phylloquinone.

In most cases, vitamin K status is not routinely assessed, except in individuals who are taking anticoagulants or have bleeding disorders. The only clinically relevant indicator of vitamin K content is prothrombin time (required for blood clotting). nine0003

Adequate vitamin K intake values are not well defined and vary by age and sex. The National Health System (NHS) recommends that adults take approximately 0. 001 mg of vitamin K per kilogram of body weight daily.

001 mg of vitamin K per kilogram of body weight daily.

Calculation of the optimal dosage is still being studied, scientists call the figure from 120 micrograms per day for men and 90 micrograms for women to 200 micrograms for healthy adults. It should not be increased during pregnancy or breastfeeding as this is usually provided by a balanced diet. The need for vitamin K increases with high doses of D3 and calcium. nine0003

The table shows the current Adequate Intake (AI) values for vitamin K in micrograms (mcg). For infants, values are based on average intake of the nutrient by healthy infants and the assumption that infants receive a prophylactic dose of vitamin K at birth.

Adequate vitamin K intake

| Age | Men nine0066 | Women | Pregnancy | Breastfeeding |

| Birth before 6 months | 2. | 2.0 mcg | nine0066 | |

| 7-12 months | 2.5 mcg | 2.5 mcg | ||

| 1-3 years | 30 mcg | 30 mcg | nine0066 | |

| 4-8 years | 55 mcg | 55 mcg | ||

| 9-13 years old | 60 mcg | 60 mcg | nine0061 ||

| 14-18 years old | 75 mcg | 75 mcg | 75 mcg | 75 mcg |

| 19+ years | 120 mcg nine0003 | 90 mcg | 90 mcg | 90 mcg |

US National Health and Nutrition Survey 2011-2012 (NHANES) data show that among children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years, the average daily intake of vitamin K from food is 66 mcg, in adults aged 20 years and older - 122 mcg for women and 138 mcg for men. When considering both foods and supplements, the average daily intake of vitamin K increases to 164 micrograms for women and 182 micrograms for men. nine0003

When considering both foods and supplements, the average daily intake of vitamin K increases to 164 micrograms for women and 182 micrograms for men. nine0003

Some analyzes of NHANES data from 2003-2006 and 2007-2010 raised concerns about average vitamin K intake, as only one-third of the US population had more than a daily requirement. The importance of these results is not yet entirely clear, as they are only an assessment of the need. Finally, food composition databases provide information mainly on phylloquinone, menaquinones, both dietary and due to bacterial production in the gut, most likely also affect vitamin K status.

Where is vitamin K found?

Most vitamin K1 in green vegetables (spinach, broccoli, cruciferous vegetables, asparagus, lettuce, parsley, artichokes, beans, leeks, peas, chard and parsnips), as well as carrots and blueberries. Among the record holders for phylloquinones: cabbage, broccoli, lettuce, watercress, spinach, rapeseed and soybean oils, which contain up to 1000 micrograms of vitamin K per 100-gram serving. In green beans, cucumbers, leeks, peas and olive oil - up to 100 mcg. This compound is also found in calf liver, beef or pork, and dairy products. nine0003

In green beans, cucumbers, leeks, peas and olive oil - up to 100 mcg. This compound is also found in calf liver, beef or pork, and dairy products. nine0003

Vitamin K2 is largely synthesized by intestinal bacteria, but can also be found in certain foods such as fermented foods (cheese, yogurt, milk), liver, fish oil, etc. The content of menaquinone in foods depends on bacterial strains and fermentation conditions. There is a lot of vitamin K2 in natto, a traditional Japanese food made from fermented soybeans. Animals can synthesize MK-4 from menadione, a synthetic form of vitamin K that is sometimes added to poultry and pig feeds. nine0003

Data on the bioavailability of various forms of vitamin K from food are very limited. The degree of absorption of phylloquinone in its free form is approximately 80%, but the rate of absorption from food is much lower. Phylloquinone in plant foods is closely related to chloroplasts and is therefore less bioavailable than from oils or supplements. For example, the body absorbs phylloquinone from spinach only 4-17% more than from a tablet. Consumption of vegetables with some fat improves the absorption of phylloquinone, but the amount absorbed is still lower than that of oils. Limited research indicates that long-chain UA may have higher absorption rates than phylloquinone from green vegetables. nine0003

For example, the body absorbs phylloquinone from spinach only 4-17% more than from a tablet. Consumption of vegetables with some fat improves the absorption of phylloquinone, but the amount absorbed is still lower than that of oils. Limited research indicates that long-chain UA may have higher absorption rates than phylloquinone from green vegetables. nine0003

Because vitamin K is fat soluble, vitamin K foods should be consumed in combination with fat to improve absorption. So, drizzle some olive oil or add diced avocado to green leafy lettuce.

An example of a good food combination would also be:

+ broccoli or kale stewed in olive oil

+ roasted Brussels sprouts with almonds

+ addition to salads and other dishes of parsley.

Vitamin K in foods

| Product name | Vitamin K content per 100g | Percentage of daily requirement |

| Parsley (greens) nine0066 | 1640 mcg | 1367% |

| Watercress (greens) | 542 mcg | 452% |

| Spinach (greens) | 483 mcg | nine0061 |

| Basil (greens) | 415 mcg | 346% |

| Goose liver | 369 mcg | 307% |

| Leaf lettuce (greens) | 173 mcg | 144% |

| Broccoli | 102 mcg | 85% |

| White cabbage | nine0061 63% | |

| Prunes | 59. | 50% |

| Chinese cabbage | 42.9 mcg | nine0002 36% |

| Celery (root) | 41 mcg | 34% |

| Cashew | 34.1 mcg | 28% |

| Avocado nine0003 | 21 mcg | 18% |

| Blueberries | 19.3 mcg | 16% |

| Garnet | 16.4 mcg | nine0061 |

| Cucumbers | 16.4 mcg | 14% |

| Cauliflower | 16 mcg | 13% |

Vitamin K supplement

This nutrient is present in most multivitamin/multimineral supplements, typically at levels less than 75% of the daily intake. It is also available in dietary supplements containing vitamin K alone or in combination with several other elements, often calcium, magnesium and/or vitamin D.

It is also available in dietary supplements containing vitamin K alone or in combination with several other elements, often calcium, magnesium and/or vitamin D.

These preparations generally have a wider range of vitamin K doses than multivitamin or mineral supplements. , providing 4050 mcg (5063% of DV) or other very high amount. Several forms of the micronutrient are used in dietary supplements, including vitamin K1 in the form of phylloquinone or phytonadione (a synthetic form of vitamin K1) and vitamin K2 in the form of MK-4 or MK-7. There is insufficient data on the relative bioavailability of various forms of supplementation of this vitamin. One study found that both phytonadione and MK-7 supplements are well absorbed, but MK-7 has a longer half-life. nine0003

Vitamin K supplements are very common in infants. They compensate for the insufficient intake of the nutrient with breast milk and the non-existent reserves of the newborn. Thus, this supplement limits the risk of hemorrhagic disease in the first months of life.

Dietary supplements containing vitamin K are particularly recommended for the prevention of osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease associated with vascular calcification. The competent authorities recommend not to exceed the dosage of 25 micrograms per day in order to avoid the risk of overdose, the long-term effects of which are not yet known. nine1099

Menadione (vitamin K3) is a synthetic form of vitamin K. However, in laboratory studies in the 1980s and 1990s, it was shown to damage liver cells, so it is no longer used in supplements or fortified foods. Indeed, being three times more active than other forms of vitamin K, it can cause significant side effects (nausea, headache, anemia, etc.).

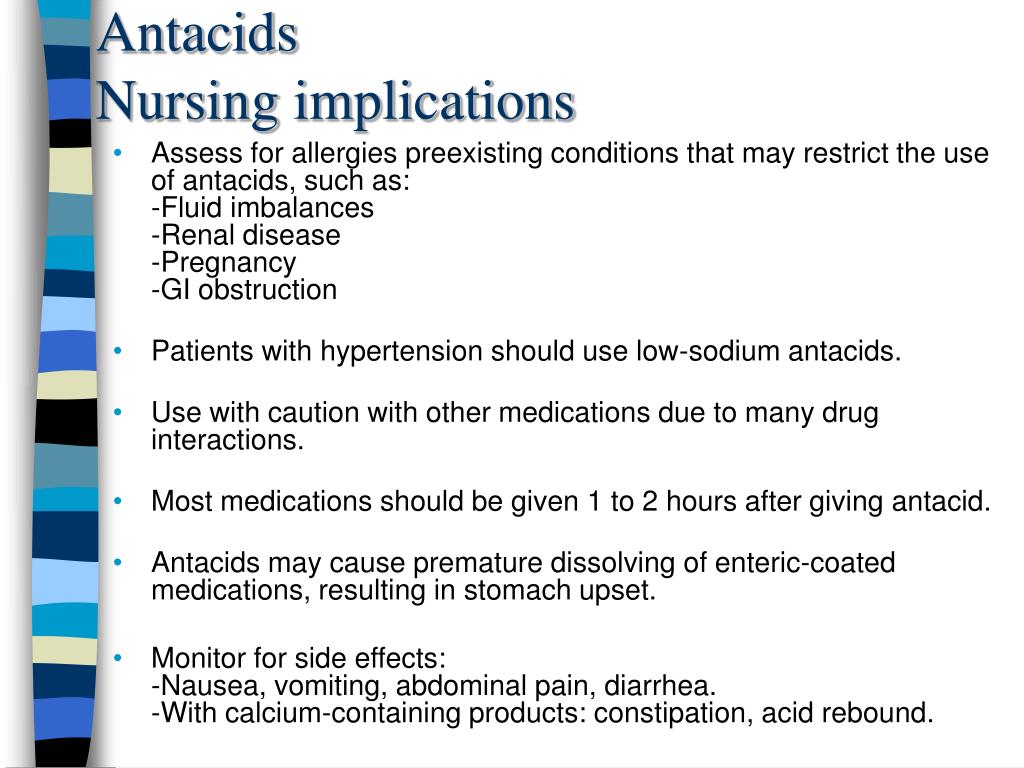

Vitamin K antagonists

nine0002 Among the substances that weaken the action of vitamin K are the following:a) derivatives of 4-hydroxycoumarin - neodicoumarin, sincumar, warfarin;

b) indanedione derivative - phenyline.

Anticoagulants, antacids, antibiotics, aspirin, and medicines for cancer, seizures, and high blood pressure can suppress the effects of vitamin K. The compounds that make up these drugs are conditionally antagonists of vitamin K1.

The compounds that make up these drugs are conditionally antagonists of vitamin K1.

Did you know?

Antibiotic medications can destroy vitamin K-producing bacteria in the gut, potentially lowering vitamin K levels, especially if taken for more than a few weeks. People who have a poor appetite with long-term use of antibiotics are at greater risk of deficiency and may benefit from vitamin K supplementation.

In addition, the activity of vitamin K synthesis and absorption in the intestine is adversely affected by high doses of vitamins A and E.

Side effects of taking vitamin K

Due to its low potential for toxicity, vitamin K has no clear contraindications. No side effects associated with increased intake of vitamin K from food or supplements have been reported in humans or animals.

Common contraindications for vitamin K supplementation in the form of supplements include:

❌ taking anticoagulants, which, unlike menaquinone and phylloquinone, “work” in reverse and promote blood thinning

❌ hereditary hypoprothrombinemia (low level of prothrombin, a blood clotting protein)

❌ kidney failure.

The use of vitamin K also requires caution in newborns and in case of individual intolerance.

There is a case in Ayrshire where a man with an artificial heart was hospitalized after eating Brussels sprouts. Vitamin K, which is found in large quantities in this vegetable, prevented the action of anticoagulant drugs taken by the patient. nine0003

The decision to supplement or discontinue group K drugs should only be made by a physician, as excess of the nutrient due to prolonged high-dose intake can cause increased blood clotting and cause thrombosis.

What to look for when choosing vitamin K

It is useful to combine vitamin K intake with mono- and polyunsaturated fats, calcium, vitamin D3. Due to the fact that vitamin K is an activator of calcium absorption, preparations containing the last three elements help to completely eliminate the deficiency of nutrients important for skeletal growth and maintaining bone strength. nine0003

When deciding on an additional intake of vitamin K, it is necessary to take into account its main property - to influence blood clotting, which is important for people who constantly take anticoagulants.

Regulates metabolism in muscle and nerve tissues.

Regulates metabolism in muscle and nerve tissues.  Supports liver functions.

Supports liver functions.  Regulates skin regenerative processes. nine0003

Regulates skin regenerative processes. nine0003  9

9  9

9  2

2  0

0  0 mcg

0 mcg  5 mcg

5 mcg