How to help your child with ocd and anxiety

The Parents' Role in OCD Treatment

When you’re the parent of an anxious child, you assume that your role is to provide reassurance, comfort, and a sense of safety. Of course you want to support and protect a child who is distressed and, as much as possible, avert her suffering. But in fact, when it comes to a child with an anxiety disorder like obsessive compulsive disorder, trying to shield her from things that trigger her fears can be counterproductive for the child. By doing what comes naturally to a parent, you are inadvertently accommodating the disorder, and allowing it to take over your child’s life.

That’s why parents have a surprisingly important role in treating anxiety disorders in children. The gold standard in pediatric OCD treatment is a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy called exposure and response prevention. The therapy involves “exposing” the child to her anxieties in a gradual and systematic way, so she no longer fears and avoids those objects or situations; “response prevention” means she is not allowed to perform a ritual to manage fears. Because parents become so involved in their children’s OCD, research has shown that including parents in treatment and assigning them as “co-therapists” improves effectiveness.

The fear hierarchy

In therapy the child, parents, and therapist create a “fear hierarchy” in which they collaboratively identify all of the feared situations, rate them on a scale of 0-10, and tackle them one at a time. For example, a child with fears about germs and getting sick would repeatedly confront “contaminated” situations and objects until her fear subsides and she can tolerate the activity. The child would start with a low-level anxiety item, such as touching clean towels, and build to more difficult items such as holding half-eaten food from the trash.

Response prevention involves preventing the child from performing the behavior that serves to decrease the anxiety. For example, a boy with a fear of germs would have to abstain from washing his hands after touching the doorknob, or the garbage. Through gradual exposure he learns that what he “fears” usually does not come true, so that new learning can take place. It also teaches him that he can tolerate uncomfortable feelings.

Through gradual exposure he learns that what he “fears” usually does not come true, so that new learning can take place. It also teaches him that he can tolerate uncomfortable feelings.

Much of the work in CBT involves practice outside of sessions, requiring parents to participate in the treatment. Children are assigned “homework” and asked to continue practicing facing their fears in a variety of settings. Since exposure and response prevention evokes anxiety and requires considerable follow-up, family involvement and support is essential.

For a child with a fear of contamination, the parents may encourage him to do the dishes, or to become a “human vacuum cleaner,” which is what clinicians call picking up small scraps of garbage from the carpet. A child with fears of vomiting might write a comic about “Vomit Man” in session with his therapist, and then practice reciting it aloud to his parents.

The problem with reassurance

But parents have a bigger role than backup when it comes to practicing exposures at home. Since OCD can be a crippling disorder for children, relatives often become excessively involved in a child’s symptoms in order to help the child function. For instance, many children with OCD, as well as other anxiety disorders, seek constant reassurance from family members. Reassurance-seeking is used by children to manage fears, and many parents provide it, even though it’s excessive, in order to make their child feel better in the moment.

Since OCD can be a crippling disorder for children, relatives often become excessively involved in a child’s symptoms in order to help the child function. For instance, many children with OCD, as well as other anxiety disorders, seek constant reassurance from family members. Reassurance-seeking is used by children to manage fears, and many parents provide it, even though it’s excessive, in order to make their child feel better in the moment.

Reassurance-seeking is one of the many forms of “family accommodation.” This phenomenon refers to the manner in which family members participate in the rituals the child uses to manage his anxiety, as well as how they modify personal and family routines in order to accommodate him.

Many children suffering from OCD are unable to tolerate uncertainty, and they ask their parents to provide them with definitive answers. For example, it is not uncommon to hear an anxious child ask their parent “Am I going to get sick from eating this?” or “Is everything going to be okay?” although the answer may have already been provided several times.

Parents can easily become frustrated because they feel like no matter how many times their child’s questions are answered, they are never satisfied. Answering their child’s questions becomes an endless cycle, and the child never learns that he can indeed tolerate the uncertainty.

Accommodating fears

There are many other forms of accommodation. Families may stop taking vacations, going out to restaurants, or even change the way they speak in order to avoid anxiety-provoking situations for their child. They may avoid particular names, numbers, colors, and sounds that trigger anxiety.

“OCD can be very overwhelming to families and can really interfere with how families can normally function,” says Jerry Bubrick, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute who specializes in anxiety and OCD. “The family decisions are made to accommodate the anxiety, rather than the best interests of the family.”

To the family of a patient we’ll call John, a 12-year old boy who was treated at the Child Mind Institute for OCD, this is all too familiar. John had fears about contamination and gaining weight and thus he avoided any food that was considered “unhealthy,” took up to seven showers a day, and didn’t play with his siblings or hug his parents in the belief that they were contaminated.

John had fears about contamination and gaining weight and thus he avoided any food that was considered “unhealthy,” took up to seven showers a day, and didn’t play with his siblings or hug his parents in the belief that they were contaminated.

“We didn’t go out to a restaurant for months,” said John’s mother. “He didn’t have any friends come over. We didn’t have any of our friends come over. Our house was a safe place.”

But accommodating John’s anxiety didn’t stop it from taking over more and more of his life. John’s mother described the peak of his OCD as an extremely challenging time for her family. “It was really hard because it’s like we had lost our son. He was so trapped in the OCD. We couldn’t physically touch him. There was no spontaneity anymore. We couldn’t even sit across the table and talk anymore.”

Reinforcing anxiety

While the parents who accommodate their child are well intentioned, family accommodation is known to reinforce their child’s symptoms. Since anxiety is maintained through avoidance, family members who accommodate their child are causing the symptoms to become even more fixed.

Since anxiety is maintained through avoidance, family members who accommodate their child are causing the symptoms to become even more fixed.

“Before I knew what accommodation was, I thought I was helping,” said John’s mother. “I was heartbroken when I found out the definition of accommodation. I was devastated to know I was feeding the OCD instead of helping John.”

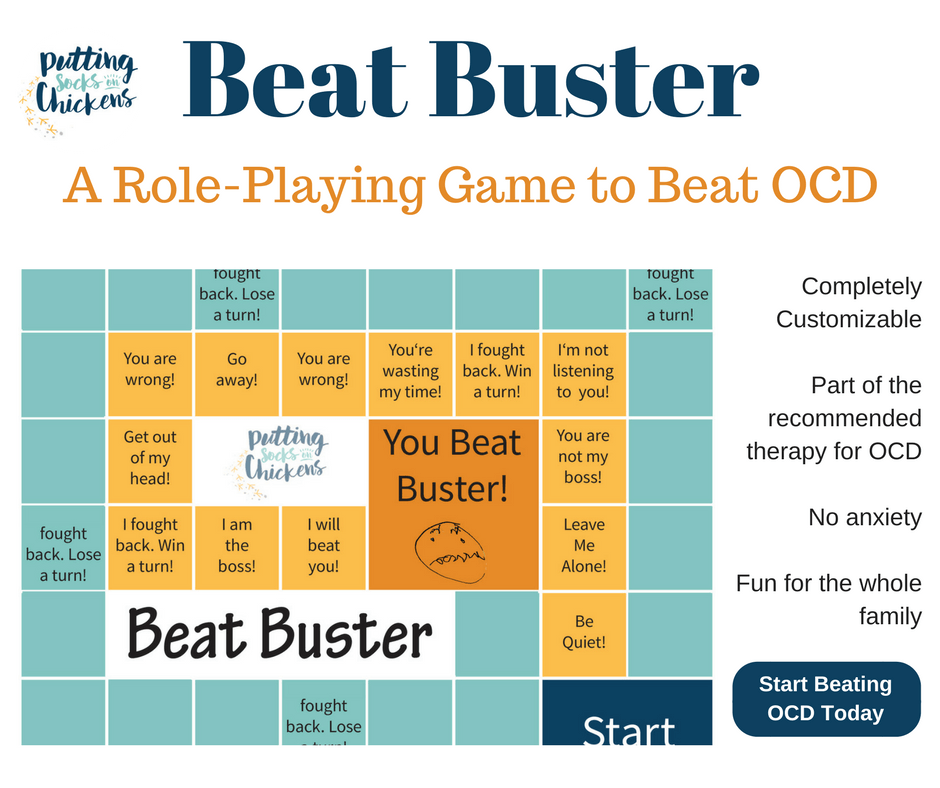

Naming the child’s OCD is one way to reduce the stigma associated with it, and makes the child feel like the anxiety is not who she is. For example, a child may name her OCD “The Bully” or “The Witch.” John’s mother continues: “Divorcing the OCD from John has been huge. Now the family has a common enemy, everyone is in on the battle. Before it was an unnamed invader. Now we know who we’re fighting.”

Building coping skills

Through treatment, parents learn new ways to respond when their children get “stuck” and how to encourage their child to rely on coping skills or to “boss back” their anxiety, instead of relying on their parents to help them through it. The children eventually become much more independent, and the parents may start to realize that anxiety is no longer in charge of their families.

The children eventually become much more independent, and the parents may start to realize that anxiety is no longer in charge of their families.

Grandparents and siblings can also become involved in family accommodation, although they are not typically included in treatment as regularly as parents are.

“Since grandparents and siblings are more a part of the child’s outside world, they may be more likely to accommodate because they want to maintain peace,” said Dr. Bubrick. “They should be a involved in the treatment so they don’t undermine it.”

Helping kids face fears

Through treatment, family members learn to help their children face their fears instead of avoiding them. Instead of comforting the child, it becomes the parent’s job to remind him of the skills he has developed in treatment and to use them in the moment.

“Now I’m helping John and I’m not feeding the OCD,” said John’s mom. A lot of that is letting John know that he has strength to fight the OCD. Reminding him of the strategies instead of making the world better for him.”

Reminding him of the strategies instead of making the world better for him.”

Managing OCD in Your Household

As you already know, when your child has OCD, the entire household is affected. Siblings and parents, alike may have their routines interrupted or feel pressured to accommodate your child with OCD by taking part in rituals. But more than anything, it is important that your child with OCD feel loved and supported, even when that means using “tough love” to enforce homework and exercises assigned by your child’s therapist.

In an effort to strengthen relationships between individuals with OCD and their family members and to promote understanding and cooperation within households, we have developed the following list of useful guidelines for family members to be tailored for individual situations. If you are unsure how to employ or implement some of these guidelines, don’t be afraid to ask your child’s OCD therapist for help — your therapist should be accustomed to working with the entire family when necessary.

1. Recognize signals

This first guideline stresses that family members learn to recognize the “early warning signs” of OCD symptoms. Your child may seem fine from the outside but may suddenly experience a wave of intrusive thoughts, so watch for subtle behavior changes. Remember that these changes can be gradual but overall different from how your child or teen has generally behaved in the past.

Signals to watch for include, but are not limited to:

- Large blocks of unexplained time that your child or teen is spending alone (in the bathroom, getting dressed, doing homework, etc.)

- Doing things again and again (repetitive behaviors)

- Constant questioning of self-judgment; excessive need for reassurance

- Simple tasks taking longer than usual

- Perpetual tardiness

- Increased concern for minor things and details

- Severe and extreme emotional reactions to small things

- Inability to sleep properly

- Staying up late to get things done

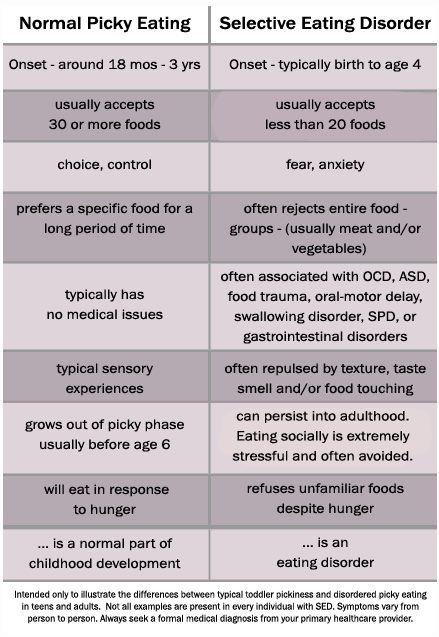

- Significant change in eating habits

- Daily life becomes a struggle

- Increased irritability and indecisiveness

People with OCD usually report that their symptoms get worse the more they are criticized or blamed because these emotions generate more anxiety. It is essential, then, that you learn to view these behaviors as signals of OCD and not as personality traits. This way, you can help your child to combat the symptoms, rather than encouraging your child to hide the symptoms out of shame or fear.

It is essential, then, that you learn to view these behaviors as signals of OCD and not as personality traits. This way, you can help your child to combat the symptoms, rather than encouraging your child to hide the symptoms out of shame or fear.

2. Modify expectations

People with OCD consistently report that change of any kind, even positive change, can be experienced as stressful. It is often during these times that OCD symptoms tend to flare up; however, you can help to moderate stress by modifying your expectations during these times of transition. Family conflict only fuels the fire and promotes symptom escalation (“Just snap out of it!’). Instead, a statement such as: “No wonder your symptoms are worse — look at the changes you are going through,” is validating, supportive, and encouraging. Remind yourself the impact of change will also change; that is, the person with OCD has survived many ups and downs, and setbacks are not permanent.

3. Remember that people get better at different rates

There is a wide variation in the severity of OCD symptoms between individuals. Remember to measure progress according to your child’s own level of functioning, not to that of others. You should encourage your child to push him/herself and to function at the highest level possible; yet, if the pressure to function “perfectly” is greater than a person’s actual ability, it creates more stress which leads to more symptoms. Just as there is a wide variation between individuals regarding the severity of their OCD symptoms, there is also wide variation in how rapidly individuals respond to treatment. Be patient. Slow, gradual improvement may be better in the end if relapses are to be prevented.

Remember to measure progress according to your child’s own level of functioning, not to that of others. You should encourage your child to push him/herself and to function at the highest level possible; yet, if the pressure to function “perfectly” is greater than a person’s actual ability, it creates more stress which leads to more symptoms. Just as there is a wide variation between individuals regarding the severity of their OCD symptoms, there is also wide variation in how rapidly individuals respond to treatment. Be patient. Slow, gradual improvement may be better in the end if relapses are to be prevented.

4. Avoid day-to-day comparisons

You might hear your child say he or she feels like they are “back at the start” during symptomatic times. Or, you might be making the mistake of comparing your child’s progress (or lack thereof) with how he/she functioned before developing OCD. It is important to look at overall changes since treatment began. Day-to-day comparisons are misleading because they don’t represent the bigger picture. When you see “slips,” a gentle reminder that “tomorrow is another day to try” can combat your child or teen’s possible desire to self-destructively label him or herself as a “failure,” “imperfect,” or “out of control,” which could result in a worsening of symptoms!

When you see “slips,” a gentle reminder that “tomorrow is another day to try” can combat your child or teen’s possible desire to self-destructively label him or herself as a “failure,” “imperfect,” or “out of control,” which could result in a worsening of symptoms!

You can make a difference with reminders of how much progress has been made since the worst episode and since beginning treatment. Consider occasionally using a rating scale to have an objective measure of progress that both you and your child can refer back to. For example, ask your child to rate his or her symptoms using a simple 1–10 rating. You can ask things such as, “How would you rate yourself when OCD was at it’s worst? When was that? How is it today? Let’s think about this again in a week.”

5. Recognize “small” improvements

People with OCD often complain that family members don’t understand what it takes to accomplish something such as cutting down a shower by five minutes or resisting asking for reassurance one more time. While these gains may seem insignificant to other family members, it is a very big step for your child. Acknowledgment of these seemingly small accomplishments is a powerful tool that encourages him or her to keep trying. This lets your child know that his or her hard work to get better is being recognized, and can be a powerful motivator.

While these gains may seem insignificant to other family members, it is a very big step for your child. Acknowledgment of these seemingly small accomplishments is a powerful tool that encourages him or her to keep trying. This lets your child know that his or her hard work to get better is being recognized, and can be a powerful motivator.

6. Create a supportive environment

The more you can avoid personal criticism, the better — remember that it is the OCD that gets on everyone’s nerves. Try to learn as much about OCD as you can. Your child still needs your encouragement and your acceptance as a person, but remember that acceptance and support does not mean ignoring the OCD behaviors. Do your best to not participate in compulsions or rituals. In an even tone of voice explain that the compulsions are symptoms of OCD and that you will not assist in carrying them out because you want him or her to resist as well. Gang up on the OCD, not on each other!

7. Set limits, but be sensitive to mood (refer to #14 below)

With the goal of working together to decrease compulsions, family members may find that they have to be firm about:

- Prior agreements regarding assisting with compulsions

- How much time is spent discussing OCD

- How much reassurance is given

- How much the compulsions infringe upon others’ lives

It is commonly reported by individuals with OCD that mood dictates the degree to which they are able to divert obsessions and resist compulsions. Likewise, family members have commented that they can tell when someone with OCD is “having a bad day.” Those are the times when family may need to “back off,” unless there is potential for a life-threatening or violent situation. On “good days” individuals should be encouraged to resist compulsions as much as possible. Limit setting works best when these expectations are discussed ahead of time and not in the middle of a conflict. It is critical to minimize family accommodation to OCD.

Likewise, family members have commented that they can tell when someone with OCD is “having a bad day.” Those are the times when family may need to “back off,” unless there is potential for a life-threatening or violent situation. On “good days” individuals should be encouraged to resist compulsions as much as possible. Limit setting works best when these expectations are discussed ahead of time and not in the middle of a conflict. It is critical to minimize family accommodation to OCD.

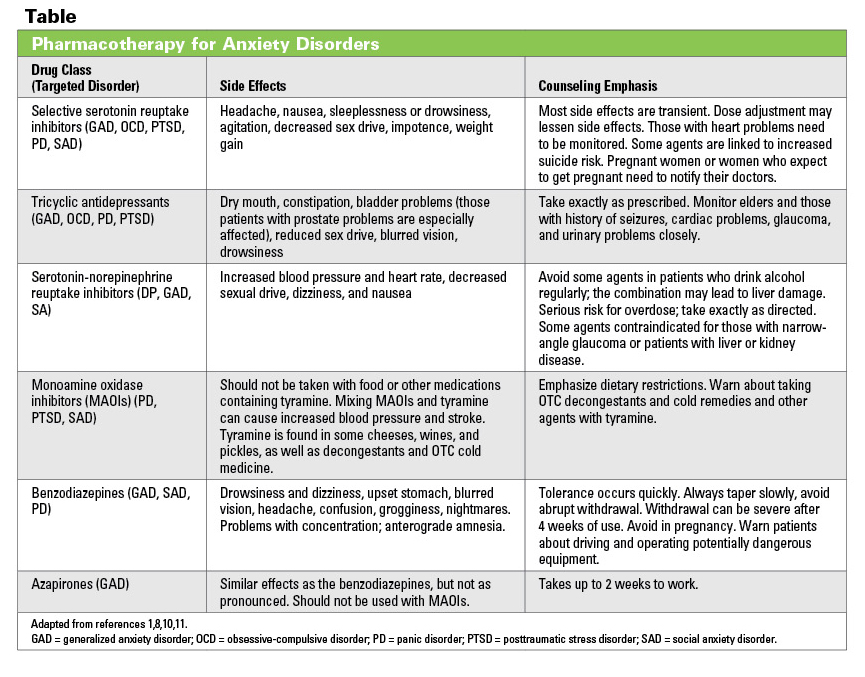

8. Support taking medication as prescribed

Be sure to follow the medication instructions that have been prescribed. Do not make any changes to your child’s dosage without consulting the prescribing physician. If you notice serious side effects and have concerns, tell you doctor immediately. Only trained professionals will know the implications of changing medication dosages or what might happen if medications are stopped abruptly.

9. Keep communication clear and simple

Avoid lengthy rationales and debates when your child or teen is seeking reassurance or asking for accommodation. This is often easier said than done because most people with OCD constantly ask those around them for reassurance: “Are you sure I locked the door?” or “Did I really clean well enough?” You have probably found that the more you try to prove that your child does need not worry, the more he or she disproves you. Even the most sophisticated explanations won’t work. There is always that lingering, “What if?”

This is often easier said than done because most people with OCD constantly ask those around them for reassurance: “Are you sure I locked the door?” or “Did I really clean well enough?” You have probably found that the more you try to prove that your child does need not worry, the more he or she disproves you. Even the most sophisticated explanations won’t work. There is always that lingering, “What if?”

Tolerating this uncertainty is an exposure (which your child should have learned how to manage in their ERP therapy) that may be tough for your child. Recognize that your child is triggered by doubt and label the problem as one of trying to gain total certainty about something that cannot be provided — this is the essence of OCD, and the goal is to accept uncertainty in life — and move on.

10. Separate time is important

Family members often have the natural tendency to feel like they should protect an individual with OCD by being with him or her all of the time. This can be destructive because family members need their private time, as do people with OCD — even children!

Make age-appropriate determinations about how much freedom and independence your child or teen should reasonably have, and give him/her the message that he or she can be left alone and can care for themselves sometimes. OCD cannot run everybody’s life; you have other responsibilities and interests, and your other children and your spouse likely need your attention as well. This not only keeps you and the rest of the family from resenting the OCD. It is also a example to your child or teen with OCD that there is more to life than anxiety. Again, this is a great topic to address with your child’s therapist.

OCD cannot run everybody’s life; you have other responsibilities and interests, and your other children and your spouse likely need your attention as well. This not only keeps you and the rest of the family from resenting the OCD. It is also a example to your child or teen with OCD that there is more to life than anxiety. Again, this is a great topic to address with your child’s therapist.

11. It has become all about the OCD!

Whether it is about asking and providing reassurance to the child with OCD or talking about the desperation and anxiety that the illness causes, families struggle with the challenge of engaging in conversations that are “OCD free,” an experience that feels liberating when achieved. We have found that it is often difficult for family members to stop engaging in conversations around the anxiety because it has become a habit and such a central part of their life. It is okay not to ask, ”How is your OCD today?” Some limits on talking about OCD and various worries is an important part of establishing a more normative routine. It also makes a statement that OCD is not allowed to run the household.

It also makes a statement that OCD is not allowed to run the household.

12. Keep your family routine “normal”

Often families ask how to undo all of the effects of months or years of going along with OCD symptoms and accommodations. For example, to avoid a tantrum, parents may allow their daughter’s contamination fear to dictate who can enter the home, and they may decide to prohibit their other children from inviting any friends over.

While this avoids an initial meltdown, it is also likely to create resentment and animosity, and also establishes the idea that the parents will cave to other OCD demands in the future. How do you break this cycle?

Through negotiation and limit setting, family life and routines can be preserved. Remember, it is in your child’s best interest to tolerate exposure to their fears and to be reminded of their siblings’ and other family member’s needs.

13. Be aware of family accommodation behaviors (refer to #14 below)

First, there must be an agreement between all parties that it is in everyone’s best interest for family members to not participate in rituals or accommodate OCD demands. However, in this effort to help your loved one reduce OCD behaviors, you may be easily perceived as being mean or uncompassionate, even though you are trying to be helpful. It may seem obvious that all family members and your child with OCD are working toward the common goal of symptom reduction, but the ways in which people do this varies. Attending a family educational support group for OCD or seeing a family therapist with expertise in OCD often helps improve family communication and understanding.

However, in this effort to help your loved one reduce OCD behaviors, you may be easily perceived as being mean or uncompassionate, even though you are trying to be helpful. It may seem obvious that all family members and your child with OCD are working toward the common goal of symptom reduction, but the ways in which people do this varies. Attending a family educational support group for OCD or seeing a family therapist with expertise in OCD often helps improve family communication and understanding.

14. Consider using a family contract

The primary objective of a family contract is to get all family members (including your child with OCD) to work together to develop realistic plans for managing the OCD symptoms in behavioral terms. Creating goals as a team reduces conflict, preserves the household, and provides a platform for families to begin to “take back” the household in situations where most routines and activities have been dictated by an individual’s OCD.

By improving communication and developing a greater understanding of each other’s perspectives, it is easier for your child to have family members help him or her reduce OCD symptoms instead of enable them. It is essential that all goals are clearly defined, understood, and agreed upon by any family members involved with carrying out the tasks in the contract. Families who decide to enforce rules without discussing it with the child with OCD first find that their plans tend to backfire. Some families are able to develop a contract by themselves, while most need some professional guidance and instruction. Be sure to reach out for professional assistance if you think you could benefit from it.

It is essential that all goals are clearly defined, understood, and agreed upon by any family members involved with carrying out the tasks in the contract. Families who decide to enforce rules without discussing it with the child with OCD first find that their plans tend to backfire. Some families are able to develop a contract by themselves, while most need some professional guidance and instruction. Be sure to reach out for professional assistance if you think you could benefit from it.

Adapted from guidelines developed by Barbara Livingston Van Noppen, PhD, & Michele Tortora Pato, MD, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California.

Treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder OCD in Israel

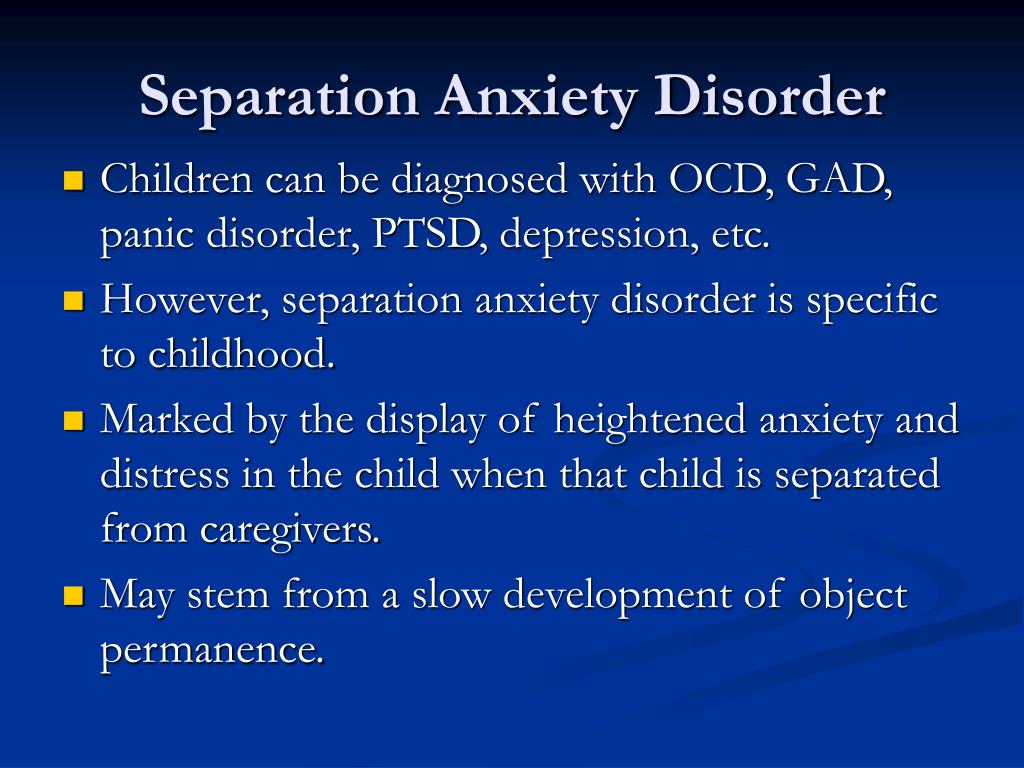

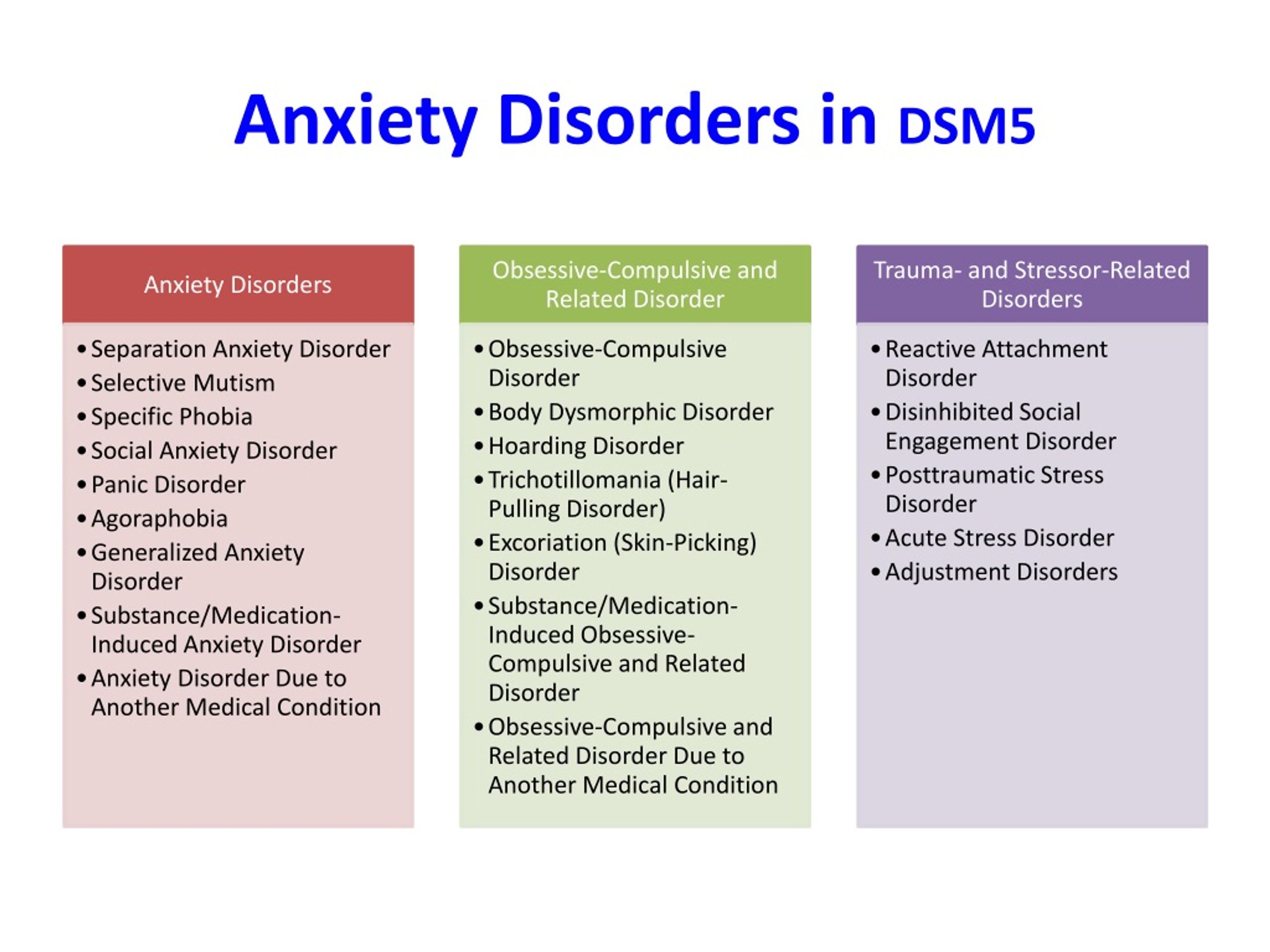

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is also known as obsessive-compulsive disorder. This disorder affects 1% to 4% of children. About half of cases begin in childhood and continue into adulthood.

Anxiety is observed in children suffering from OCD, which manifests itself in a pronounced need to organize the world around them in a special way. They ask to retell what they have already been told many times, or to play the same game many times. nine0003

They ask to retell what they have already been told many times, or to play the same game many times. nine0003

[SLIDER=1661]

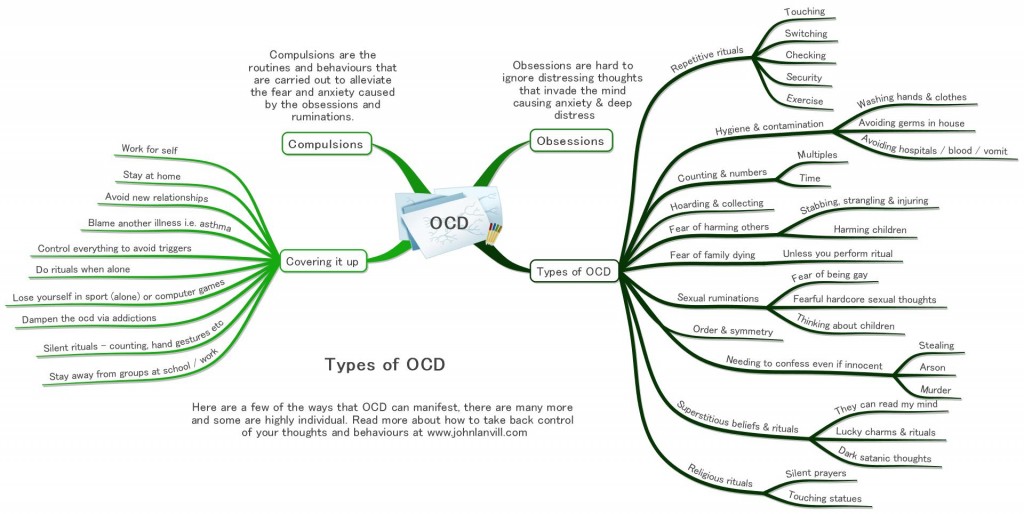

R&D includes 2 components:

-

Obsessions or obsessions. The child constantly pronounces the same thought, returns to the same memories - both in the form of visual images and in the form of inner speech. The child may be constantly disturbed by the obsessive thought of pollution. He constantly wants to wash, avoid dirty places. He may require strict order in the house, symmetry in the arrangement of objects. If something is disturbed in his habits, this causes increased anxiety. The child may also be concerned about their own health and the health of their loved ones. nine0003

-

Compulsive actions or obsessive behavior is the second component of the syndrome. We are talking about repetitive behavioral rituals, which must be observed strictly in a strict order, otherwise, according to the patient, something bad may happen.

Such rituals include constantly washing hands, touching certain things in a certain order with the hands, and much more. It should be noted that children, unlike adult patients, try to tell their parents about their rituals, which increases the chances of recovery. Unfortunately, parents do not always listen to children's experiences, and this contributes to the further development of the disorder. nine0003

Such rituals include constantly washing hands, touching certain things in a certain order with the hands, and much more. It should be noted that children, unlike adult patients, try to tell their parents about their rituals, which increases the chances of recovery. Unfortunately, parents do not always listen to children's experiences, and this contributes to the further development of the disorder. nine0003

When diagnosing obsessive-compulsive disorder, the Matspen Center conducts a comprehensive study of the patient's mental state to identify or exclude another concomitant disease. A complete physical examination of the patient is also carried out in order to determine contraindications to certain medications, as well as to establish possible physical prerequisites for the development of OCD.

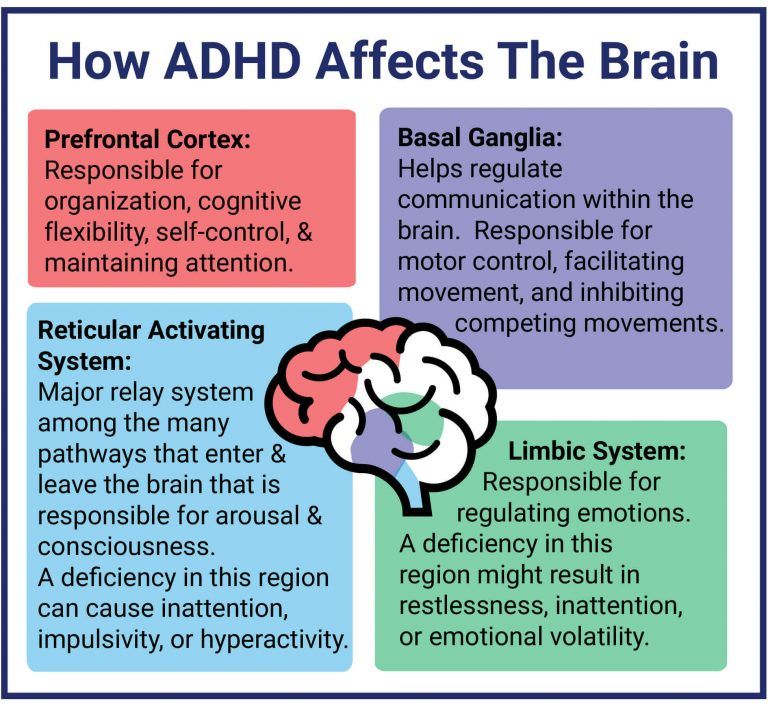

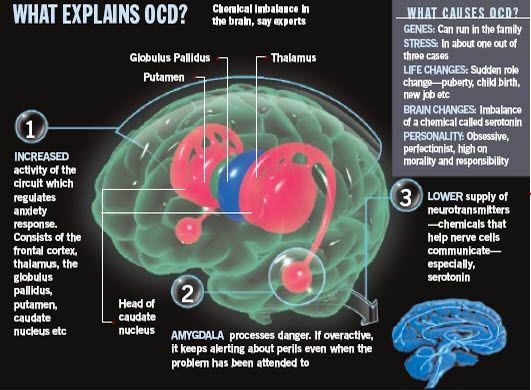

The main cause of OCD in a child may be structural or functional changes in the functioning of the anterior lobe of the brain - the ventral-medial pre-frontal cortex. This part of the brain is responsible for repetitive actions, rituals in human behavior. The pathology associated with the development of addictions to repetitive actions is also localized there. This area is associated with areas responsible for emotions, anxiety, thoughts and desires. In this way, a brain functional network is created that supports OCD. This cause can be revealed during fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). nine0003

This part of the brain is responsible for repetitive actions, rituals in human behavior. The pathology associated with the development of addictions to repetitive actions is also localized there. This area is associated with areas responsible for emotions, anxiety, thoughts and desires. In this way, a brain functional network is created that supports OCD. This cause can be revealed during fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). nine0003

why it happens and how to treat it

OCD in children: why it happens and how to treat it© Anastasia Ryzhkova

Psychiatrist Elisey Osin talks about obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Elisey Osin

Child psychiatrist nine0003

OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) in children is a serious illness for parents. Endless rituals - knock 5 times, swipe, ask the same question 25 times, etc. - can cause irritation that only increases guilt, fear and powerlessness.

Endless rituals - knock 5 times, swipe, ask the same question 25 times, etc. - can cause irritation that only increases guilt, fear and powerlessness.

The most acute and frequent questions of parents about OCD are answered by child psychiatrist Elisey Osin, an expert at the Vykhod Foundation.

- What is OKR? How to recognize it? nine0003

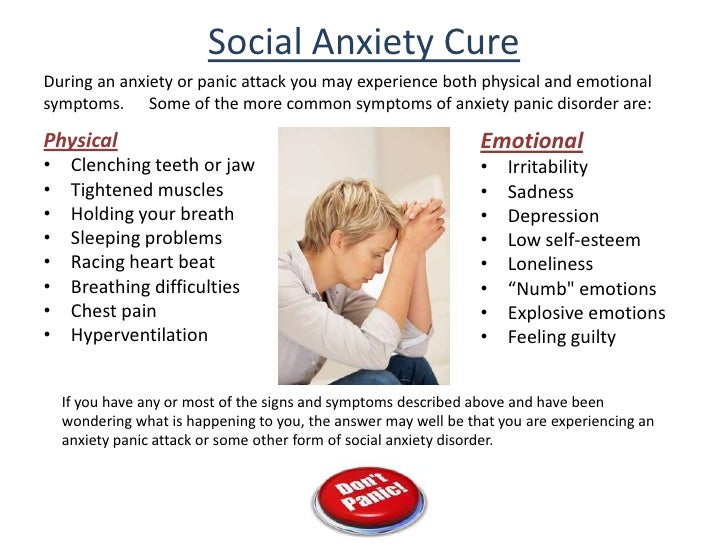

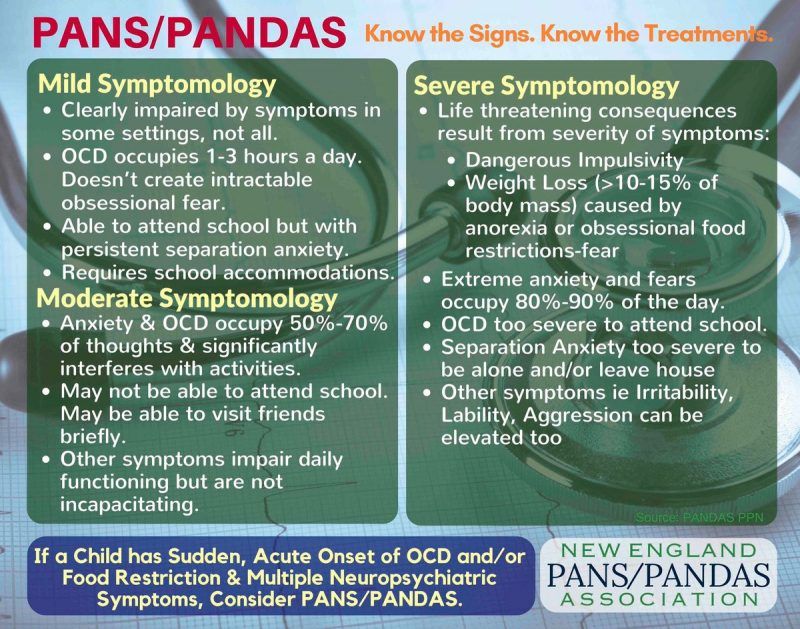

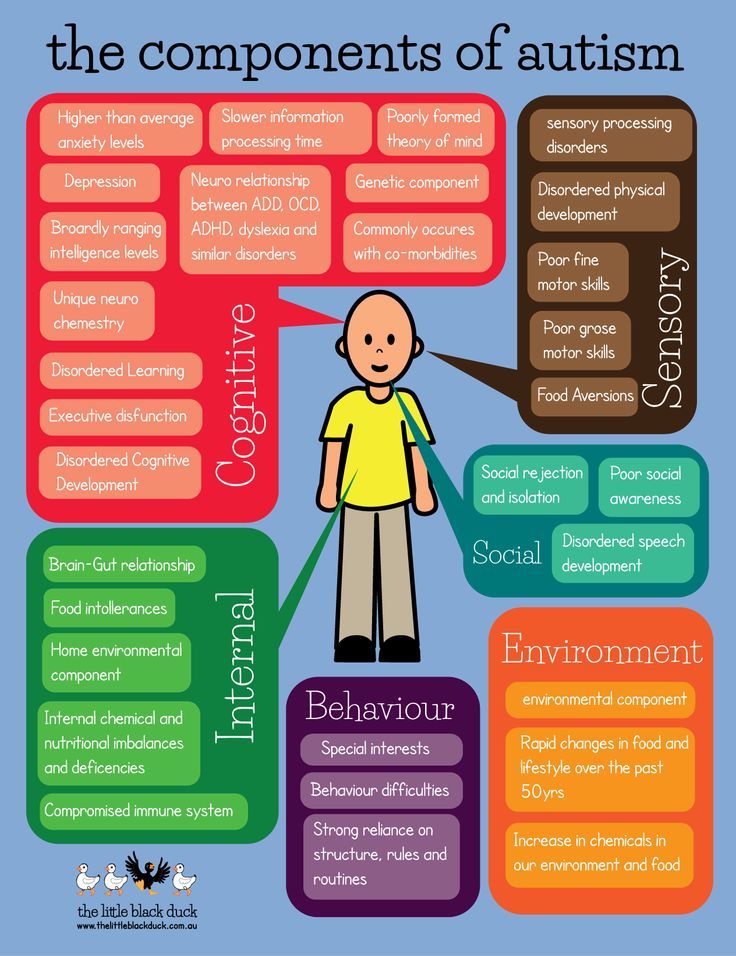

- OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder is a disorder that consists of thoughts, memories, images (obsessions) obsessively invading a person's mental activity, which come again and again and cause anxiety or discomfort; and repetitive actions, rituals (compulsions) that a person needs to reduce the discomfort or anxiety associated with obsessive thoughts and experiences.

Obsessive thoughts in OCD create a lot of stress, anxiety, tension, and greatly interfere with daily life. And it's not just the experience of "whether I closed the doors or turned off the iron. " Obsessions can be very different: they can be very frightening, for example, a child may think that a loved one wants to kill him, or, conversely, he himself can kill a loved one, or that he has become contaminated internally or externally from contact with some objects ; and there are obsessions that are not frightening, but very disturbing, for example, when a child needs to count something or repeat a certain number of times. nine0003

" Obsessions can be very different: they can be very frightening, for example, a child may think that a loved one wants to kill him, or, conversely, he himself can kill a loved one, or that he has become contaminated internally or externally from contact with some objects ; and there are obsessions that are not frightening, but very disturbing, for example, when a child needs to count something or repeat a certain number of times. nine0003

Rituals for OCD have a protective function. I go to wash my hands or I go to my parents to make sure again and again that everything will be fine, I will not die, I will not get sick. If I wash my hands three times three times, if I turn the key, if I go up to my mother and my mother says exactly these words, just like that, everything will be fine. The essence of the ritual is not very important, the function is important: everything will be fine, I will not experience this discomfort, I will not cry, I will not get infected today, I will not become dirty, I will not . .. nine0003

.. nine0003

- How to understand that this is not a childish fantasy, but OCD?

- Fantasies are usually pleasant for a child: he creates imaginary worlds, and this does not cause him stress. Children with OCD experience a lot of stress. And repetitive actions do not cause pleasure, they are designed to reduce anxiety.

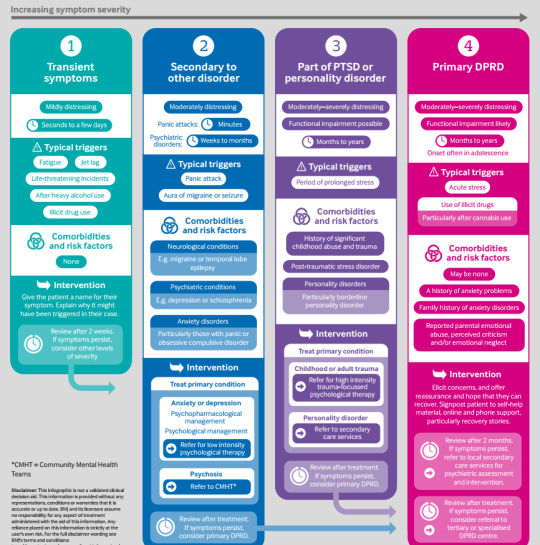

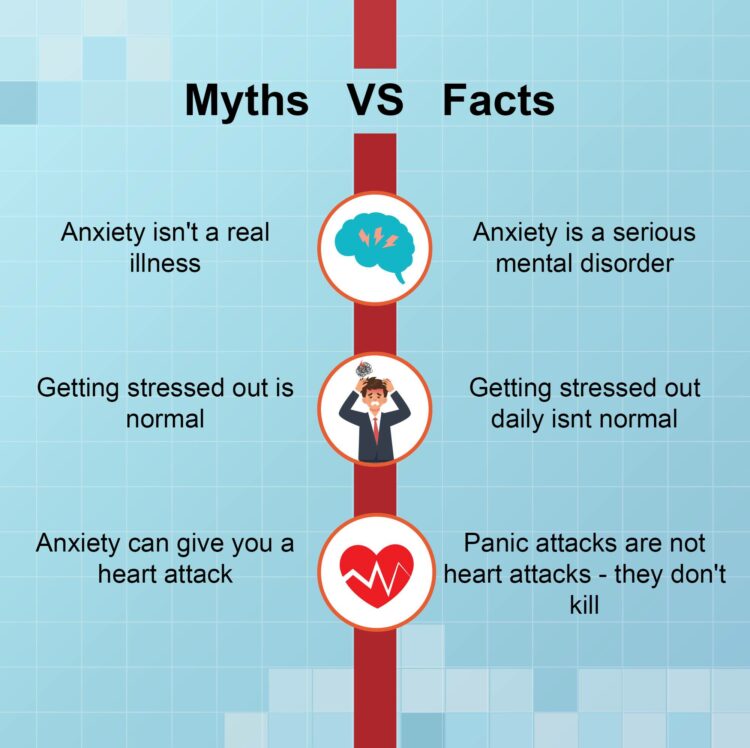

- How to distinguish OCD from other conditions that are also accompanied by obsessions and fears? For example, from increased anxiety, psychological trauma? nine0003

- In post-traumatic disorders, obsessive experiences are associated with the situation of trauma, you can trace the moment of their occurrence.

Anxiety itself is a disorder. A person with increased anxiety lives poorly, he thinks all the time that something can happen. A child who is experiencing increased anxiety needs help. Anxiety interferes with development. If you constantly think about your own safety, you cannot function normally. It is necessary to understand what causes this increased anxiety and work with the causes of anxiety. nine0003

It is necessary to understand what causes this increased anxiety and work with the causes of anxiety. nine0003

How do you differentiate “normal” anxiety from OCD? According to the result: they give actions aimed at relieving anxiety, the effect or not. If you checked the doors three times when leaving the house and calmed down, there are no difficulties - this is a normal interaction with the world, which is not always safe. If there is no calming, if you have to engage in complex rituals to cope with anxiety, if it interferes with daily life, it is possible that this is an obsessive-compulsive disorder. nine0003

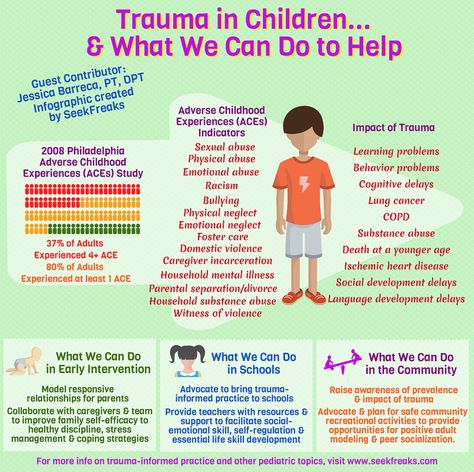

— What can cause OCD in children?

- It is very rare to single out one reason. Most often, several factors in the development of OCD are identified.

Predisposition to develop OCD. There is no direct link between parent and child OCD. But if mom or dad has OCD, then the child has a significantly higher risk of developing OCD. Studies show that families of children with OCD are noticeably more likely to have various forms of anxiety disorders. nine0003

Studies show that families of children with OCD are noticeably more likely to have various forms of anxiety disorders. nine0003

There are some characteristics of thinking associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. People analyze the world in a certain way, and everyone has certain distortions; people with OCD have very specific distortions, very specific cognitive errors.

Apparently, certain parenting styles contribute to the development of cognitive distortions. It is possible that intense or very prolonged stress can contribute to the development of OCD. nine0003

Sometimes OCD and its symptoms can be caused by the presence of a streptococcal infection in the body.

— How exactly can OCD in a child be related to upbringing? Conditionally, are the parents to blame for yelling / criticizing - and now they brought the child to a nervous breakdown?

The cognitive distortions inherent in OCD can occur when a child is made to take responsibility not only for their own actions, but also for their own thoughts. Cognitive error, when a person feels responsible for their own thoughts, is one of the important factors in OCD. nine0003

Cognitive error, when a person feels responsible for their own thoughts, is one of the important factors in OCD. nine0003

Example. The child screams: “Mom, I hate you, I want you to feel bad, why did you forbid me to play the tablet?”. Mom says: “How can you think like that, you can’t think like that, when such thoughts come to your mind - you are bad! It is a great sin to think like that, you have no right to think like that.”

Notice the difference with "don't you dare talk about your mother like that." The ban on "speaking" is a ban on action, not a ban on thoughts, and it has the right to exist, because the child broadcasts the threat of violence - and this should be discussed with children. nine0003

The cognitive distortions inherent in OCD can be caused by evaluating certain thoughts as unacceptable or sinful. They try to force the child to take control over what he has no control over - over his own thoughts, and the child begins to experience great discomfort when forbidden thoughts come to him.

How should parents behave in the given situation? It is better to discuss with the child his and your feelings, not thoughts! Voice them and look for an acceptable way of expressing them. nine0003

- We have a normal family. We do not yell at the child and do not humiliate him, but he is still anxious, afraid of the dark and suffers from obsessive thoughts. Why is that?

“Because OCD doesn’t just come from upbringing—it’s also a biological disorder. In addition, it is not always necessary to offend a child or yell at him in order to trigger severe anxiety in him. It is enough to convey to him the idea that everything that we think necessarily returns to us. That the world reacts to our thoughts and changes depending on them. One of the causes of OCD is a sense of responsibility for something that is out of your control - for your own thoughts, as I said. nine0003

- Well, if the child's behavior is seriously similar to OCD, what exactly should parents do?

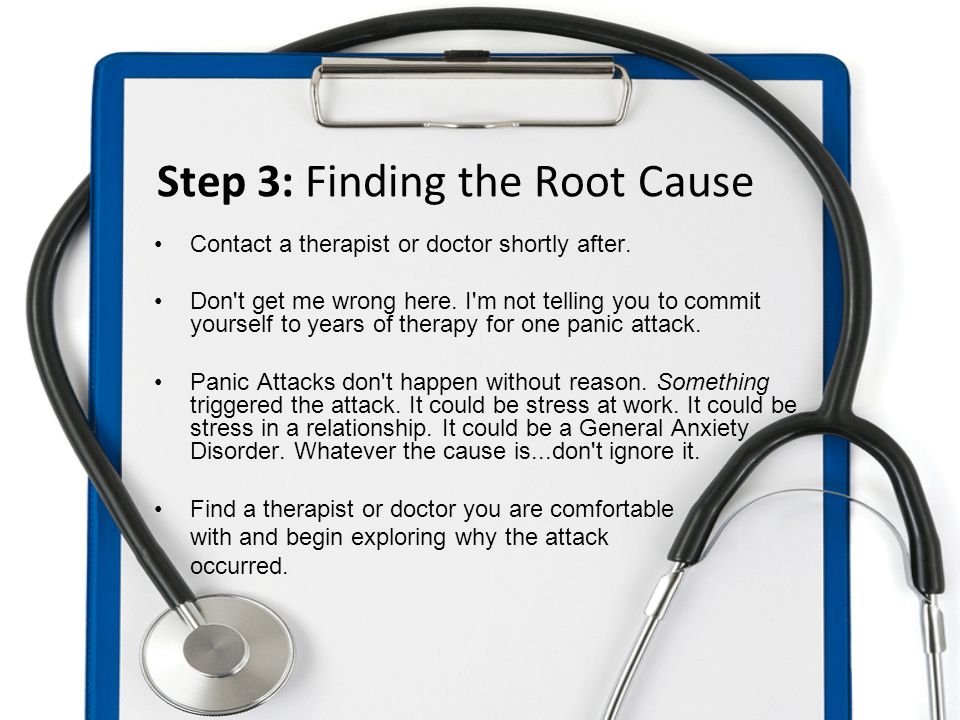

- First . Run diagnostics. See a specialist to determine if what is happening to the child is OCD or another disorder. This could be a psychotherapist working with mood disorders and anxiety, a psychologist working with cognitive behavioral therapy, or a psychiatrist. Whether it is necessary to conduct any instrumental examinations, whether it is necessary to take a blood test for the presence of a streptococcal infection in the body, the doctor will decide. The doctor will also determine the severity of the situation, as well as whether the child has depression. OCD and depression often go hand in hand. It is important to understand whether a child thinks, for example, about suicide, whether he also experiences depressed mood, melancholy in addition to obsessions, or his difficulties are limited to OCD symptoms. nine0003

Run diagnostics. See a specialist to determine if what is happening to the child is OCD or another disorder. This could be a psychotherapist working with mood disorders and anxiety, a psychologist working with cognitive behavioral therapy, or a psychiatrist. Whether it is necessary to conduct any instrumental examinations, whether it is necessary to take a blood test for the presence of a streptococcal infection in the body, the doctor will decide. The doctor will also determine the severity of the situation, as well as whether the child has depression. OCD and depression often go hand in hand. It is important to understand whether a child thinks, for example, about suicide, whether he also experiences depressed mood, melancholy in addition to obsessions, or his difficulties are limited to OCD symptoms. nine0003

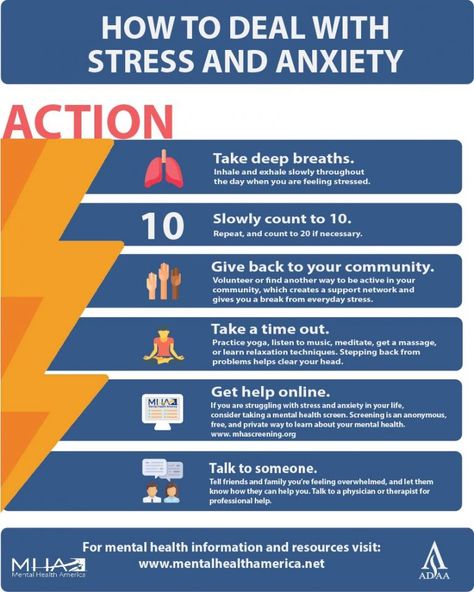

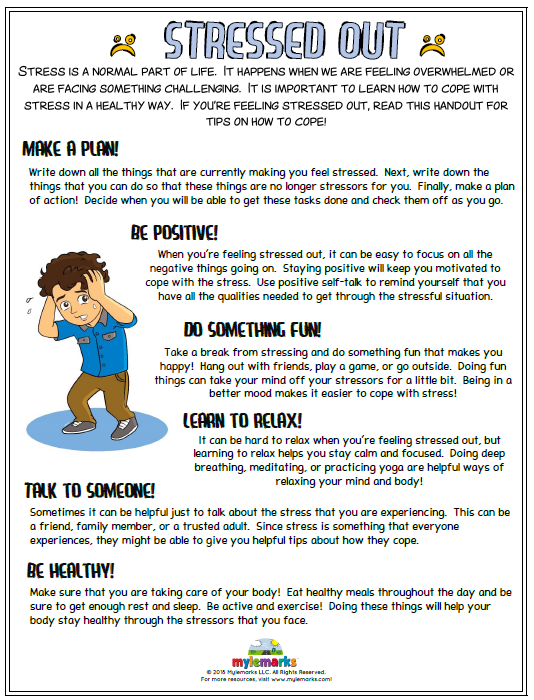

Second. Determine the optimal treatment regimen. Treatment is prescribed depending on the degree of stress experienced by the child. In some situations, the only treatment will be to reassure the parents, give advice on organizing the day, discuss with the child what is happening to him, and teach simple relaxation techniques.

In some situations, the only treatment will be to reassure the parents, give advice on organizing the day, discuss with the child what is happening to him, and teach simple relaxation techniques.

In complex cases, we go in three directions at the same time - we prescribe medications, begin psychotherapy, and conduct intensive family education in order to clarify the nature of the disorder. nine0003

If obsessive-compulsive disorder is complicated by something else—depression with suicidal behavior, highly violent behavior—the situation may sometimes require hospitalization, not because of the OCD itself, but because of the accompanying problems. Or more intensive pharmacological treatment is needed, not only with antidepressants, but also with mood stabilizers.

Third. Treatment, psychotherapy, work with parents. nine0003

— Doctors often prescribe pills for OCD. Can't do without them?

Can't do without them?

The symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder vary from person to person. Doctors look at how much stress the manifestations of OCD cause, how much they interfere. Sometimes the stress is mild, expressed only in anxiety, and this can be seen at the first meeting - by the way parents and the child talk about it. Then drug treatment may not be needed at all - psychotherapy is enough. But it happens that OCD affects a child very strongly: he is constantly in anxiety, constantly in rituals, cannot calm down, it is clearly hard for him. In such a situation, we usually try to use all the possibilities for help, including drug treatment. The right medications are a relatively quick, very effective, and fairly safe way to deal with some of the worst experiences a child has with OCD. nine0003

— Can you get rid of OCD with mild herbal sedatives?

There are no studies on the use of herbal medicines for OCD. In my opinion, getting rid of OCD with herbal sedatives is the same as getting rid of OCD with homeopathy, mud therapy, aromatherapy. If there is relief, it means that something else has worked, and not herbs. For example, parents began to pay more attention to the child, while giving soothing herbs, created a therapeutic environment. Or, in addition to herbs, they began to go to a psychotherapist. nine0003

In my opinion, getting rid of OCD with herbal sedatives is the same as getting rid of OCD with homeopathy, mud therapy, aromatherapy. If there is relief, it means that something else has worked, and not herbs. For example, parents began to pay more attention to the child, while giving soothing herbs, created a therapeutic environment. Or, in addition to herbs, they began to go to a psychotherapist. nine0003

- How to understand that the doctor to whom the child was brought is competent and will not prescribe antidepressants unnecessarily?

- The function necessary for a doctor is the ability to explain why he thought this way and not otherwise, why he prescribed this particular medicine and not another. If a doctor says he prescribes a drug simply because he has ten years of experience and six years of medical education and you don't, he doesn't really explain anything. Personally, I would avoid interactions with such a doctor. nine0003

nine0003

If a doctor says: “I made such and such a diagnosis, because, according to modern criteria ...” and, for example, points to a diagnostic manual, this is normal, this is correct. A trusted doctor is willing to share at least a little of his thoughts. This, in fact, is not difficult to do within a fifteen-minute inspection.

It is desirable that the doctor's considerations be given out, at least briefly, in writing, so that after the meeting the parents can re-read them, think over everything, discuss it, turn to another doctor for a second opinion, raise the modern qualifications of diseases, read the literature and compare it with the fact what they were told. nine0003

- What is the best way for parents to respond to a child's behavior? It is difficult not to get annoyed when a child waves his arms strangely for the hundredth time / counts sips of water / asks the question “will our plane crash” and at the same time no consolation and reassurance work.

- First. Be sure to ask for help. OCD is a well-studied and well-understood disorder, and it can be successfully treated.

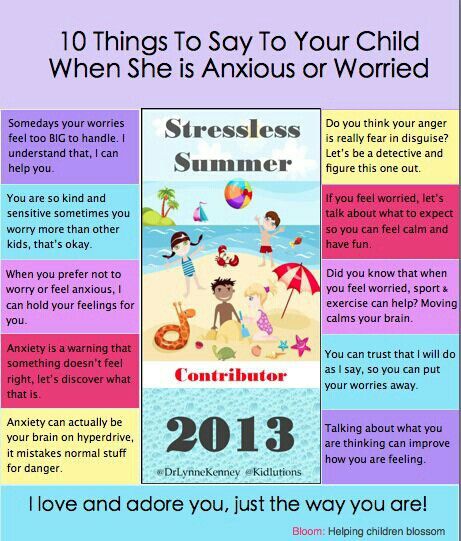

nine0092 Second. Avoid extremes. First, do not participate in rituals (for example, do not repeatedly dissuade a person that he will die, or that his hands are not dirty), because this only encourages ritualized behavior: the child feels that he is not in control situation and needs adults to cope with anxiety and discomfort. Secondly, avoid devaluing what is happening to the child, for example, phrases like “what are you driving, it’s all nonsense”, “what did you come up with there”, “you are generally sick” or “you are normal, and everything is with you OK". nine0003

Third. The main message for a child with OCD should be: “I am with you, I see what is happening to you. I am on your side and I will help you. What's going on in your head really torments you, but it's only in your head. Together we will find a way to deal with this, we will find help.” This is a difficult message because it will mean slightly different things in each situation. For example, somewhere it’s just to hug a child, somewhere it’s to remind about the relaxation techniques that he has learned, somewhere it’s to practice these techniques with him. Sometimes good psychologists working with OCD involve the child's loved ones, as if taking them as partners in therapy, allowing them to go from the beginning of therapy to regaining control over themselves with the client (child). nine0003

Together we will find a way to deal with this, we will find help.” This is a difficult message because it will mean slightly different things in each situation. For example, somewhere it’s just to hug a child, somewhere it’s to remind about the relaxation techniques that he has learned, somewhere it’s to practice these techniques with him. Sometimes good psychologists working with OCD involve the child's loved ones, as if taking them as partners in therapy, allowing them to go from the beginning of therapy to regaining control over themselves with the client (child). nine0003

- What parents of a child with OCD should not do in any case?

- First. Don't take OCD personally. For some people, obsessions can be directed at other people, for example, “Mom, do you love me?”, “Mom, will you give me to anyone?”, “Mom, am I bad?”

Second. Provocative or aggressive behavior is unacceptable: "If you say that again, I'll give you up!", "If you say that again, I'll really poison you!", "You got me!". This will only lead to an increase in the problems of the child. nine0003

This will only lead to an increase in the problems of the child. nine0003

Physical aggression, despite the apparent instantaneous effectiveness (some parents practice it, unfortunately), in the future can lead to auto-aggression. For example, parents hit a child who cannot cross the threshold, and he took a step. Parents created intense emotions for the child that overcame his anxiety, but did not remove his fear. And a person learns to cope with his anxieties and fears with the help of pain. At worst, this can lead to him hurting himself in order to cope with his anxiety. nine0003

Third. In no case should you refuse treatment.

OCD can sometimes be quiet and unobtrusive to others. For example, a teenager spends a little more time in the bathroom, the child repeats the same thing several times, he has strange habits, and relatives perceive this as eccentricity. Because of this, it seems that there is nothing to worry about, there is no need to treat. At the same time, a terrible struggle can take place inside a person for the absence of discomfort, very unpleasant or interfering obsessions come to his mind, which may not be clearly manifested outwardly, but for a child or teenager this is everyday hell. Or the child is too punctual, arrives on time, tries to do everything according to the rules, studies “excellently”, and in such a situation, parents begin to doubt the need for treatment. While the desire to do everything perfectly is one of the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. nine0003

At the same time, a terrible struggle can take place inside a person for the absence of discomfort, very unpleasant or interfering obsessions come to his mind, which may not be clearly manifested outwardly, but for a child or teenager this is everyday hell. Or the child is too punctual, arrives on time, tries to do everything according to the rules, studies “excellently”, and in such a situation, parents begin to doubt the need for treatment. While the desire to do everything perfectly is one of the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. nine0003

Sometimes the basis of the refusal to treat a child is the parents' own internal anxiety. It can be expressed in the conviction that "chemistry" (pharmaceuticals) is harmful, and only what has grown in the garden or in the forest is useful. This is nothing more than their own attempt to control the processes of life and death, because of which parents refuse to help their children (do not give them the medicine they need).

Some parents refuse to take their children to therapy because going to therapy is admitting that there are problems in your family. And because of the fear or prejudice of parents, children do not receive the help they need. nine0003

- How to tell relatives and teachers about the child's condition?

- The family in a broad sense (grandparents, uncles, aunts) needs training. The family should be taken to counseling therapists or a psychiatrist, or given OCD literature to read. If there are questions left, they did not understand something, bring them again to a meeting with the doctor so that everyone has a clear and distinct picture of what is happening to the person.

The situation is more complicated for school teachers. Teachers have power over children, and much depends on the personality of the teacher and how he treats the child. If there is contact with the teacher, you need to talk to him in the same way as with relatives. That is, to tell what kind of diagnosis it is, that we are taking medication, that it will be easier, that, of course, it is not dangerous. The more openness in such a situation, the better.

That is, to tell what kind of diagnosis it is, that we are taking medication, that it will be easier, that, of course, it is not dangerous. The more openness in such a situation, the better.

Some teachers may not be very distant and do not want to read and learn anything, they may be afraid of a special child in the class. With such a person it is better to talk simply about increased anxiety, they say, he is very exciting with us, we go to a psychologist. nine0003

- How to help a child not be afraid that peers will find out about his condition, that he will be called "mental", teased?

“This is clearly the task of the teacher and the school administration. Children can endure fantastically difficult things if there is a clear teacher's position. I saw a child with a very serious disorder, he had vocalisms, he shouted out “Damn!”, “Damn!” many times during the lesson. The teacher was aware, he knew what it was like for a child to receive treatment, and he spoke to the class several times. The conversation was conventionally as follows: “Vasya has poor eyesight - he is sitting in front; The doctor told Masha that she needed to go to the toilet - she would go to the toilet without asking, when it was convenient for her; and Petya sometimes shouts out, he does it involuntarily, you don’t need to pay attention to it. If you tease Petya, you will make Petya worse, offend him, we don’t do that at home. ” The same goes for educators. Children are amazingly flexible creatures, and they behave the way they were taught. nine0003

The conversation was conventionally as follows: “Vasya has poor eyesight - he is sitting in front; The doctor told Masha that she needed to go to the toilet - she would go to the toilet without asking, when it was convenient for her; and Petya sometimes shouts out, he does it involuntarily, you don’t need to pay attention to it. If you tease Petya, you will make Petya worse, offend him, we don’t do that at home. ” The same goes for educators. Children are amazingly flexible creatures, and they behave the way they were taught. nine0003

It is very important for the child himself to understand that he is not alone in this situation.

If a child is bullied, then you need to behave as you would with any bullying, regardless of its cause. Bullying does not depend on the characteristics of the child, but on relationships in the classroom and at school, on the norms of interaction adopted there. This must be dealt with and worked on, regardless of the child's diagnosis and, in general, the presence of a diagnosis.

We will send you the important and best materials in a week.

You can additionally set up a mailing list in your account.

I agree to the processing of my personal data

This site collects user metadata (cookies, IP addresses and location data).