Vaccination or vaccine

Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?

Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Home/

- Newsroom/

- Questions and answers/

- item/

- Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?

30 August 2021 | Q&A

Updated on 30 August 2021.

What is vaccination?

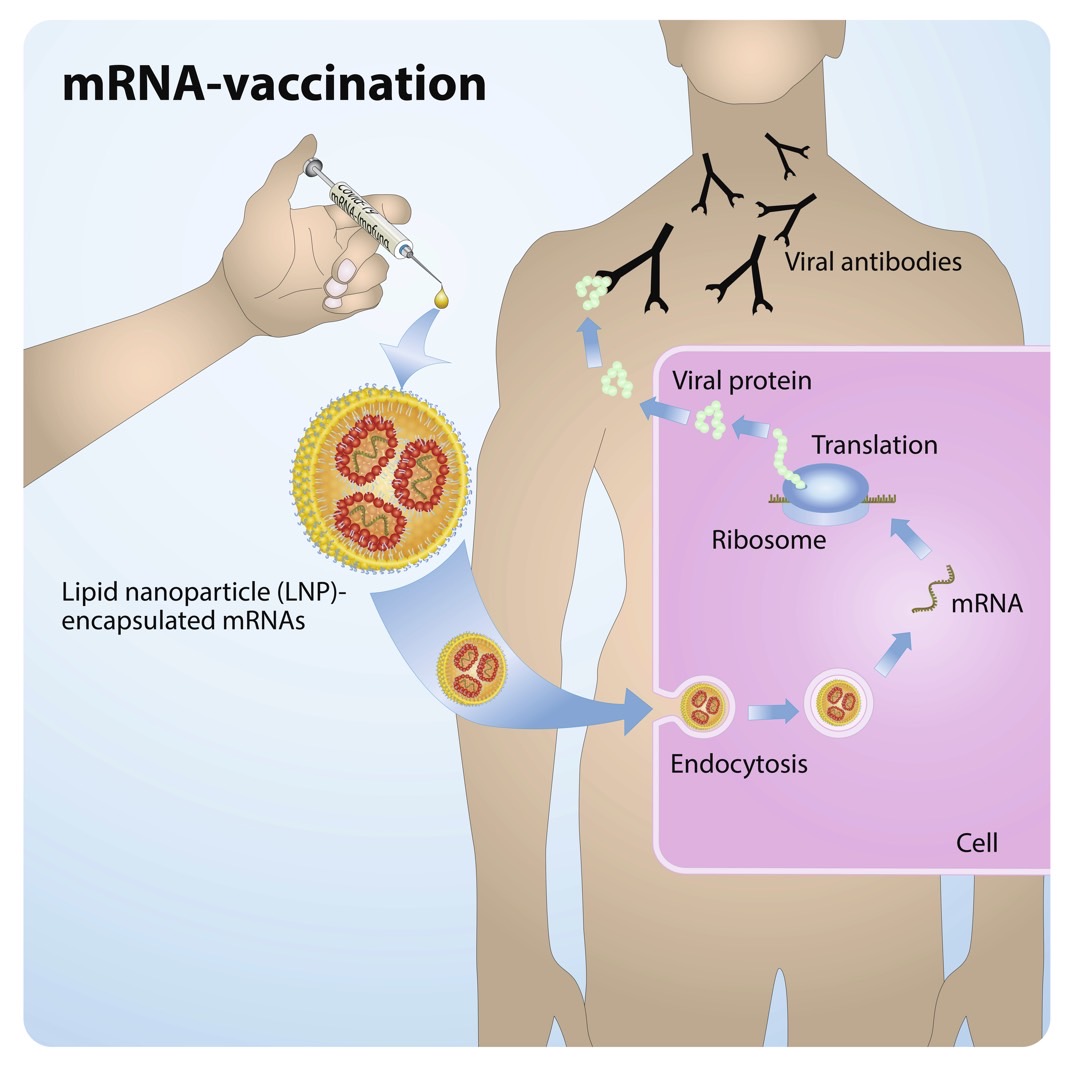

Vaccination is a simple, safe, and effective way of protecting you against harmful diseases, before you come into contact with them. It uses your body’s natural defenses to build resistance to specific infections and makes your immune system stronger.

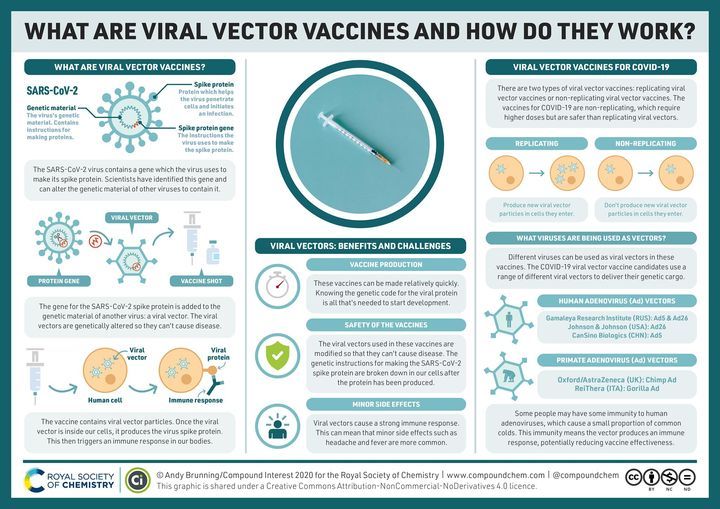

Vaccines train your immune system to create antibodies, just as it does when it’s exposed to a disease. However, because vaccines contain only killed or weakened forms of germs like viruses or bacteria, they do not cause the disease or put you at risk of its complications.

Most vaccines are given by an injection, but some are given orally (by mouth) or sprayed into the nose.

How does a vaccine work?

Vaccines reduce risks of getting a disease by working with your body’s natural defenses to build protection. When you get a vaccine, your immune system responds. It:

-

Recognizes the invading germ, such as the virus or bacteria.

-

Produces antibodies. Antibodies are proteins produced naturally by the immune system to fight disease.

-

Remembers the disease and how to fight it. If you are then exposed to the germ in the future, your immune system can quickly destroy it before you become unwell.

The vaccine is therefore a safe and clever way to produce an immune response in the body, without causing illness.

Our immune systems are designed to remember. Once exposed to one or more doses of a vaccine, we typically remain protected against a disease for years, decades or even a lifetime. This is what makes vaccines so effective. Rather than treating a disease after it occurs, vaccines prevent us in the first instance from getting sick.

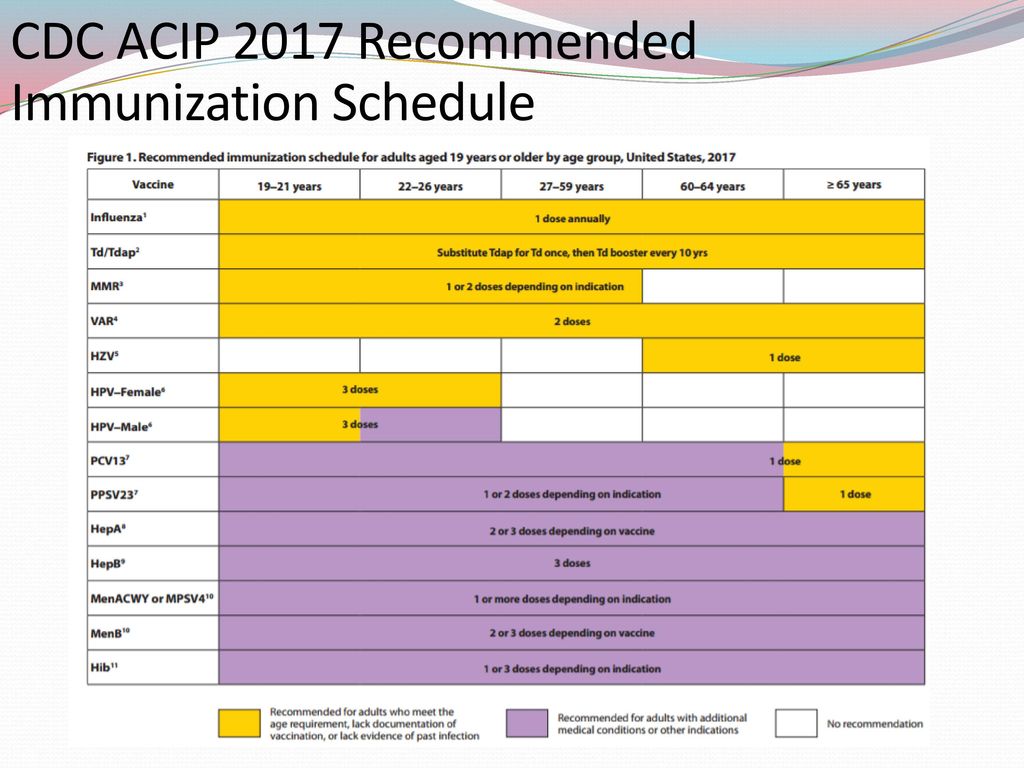

When should I get vaccinated (or vaccinate my child)?

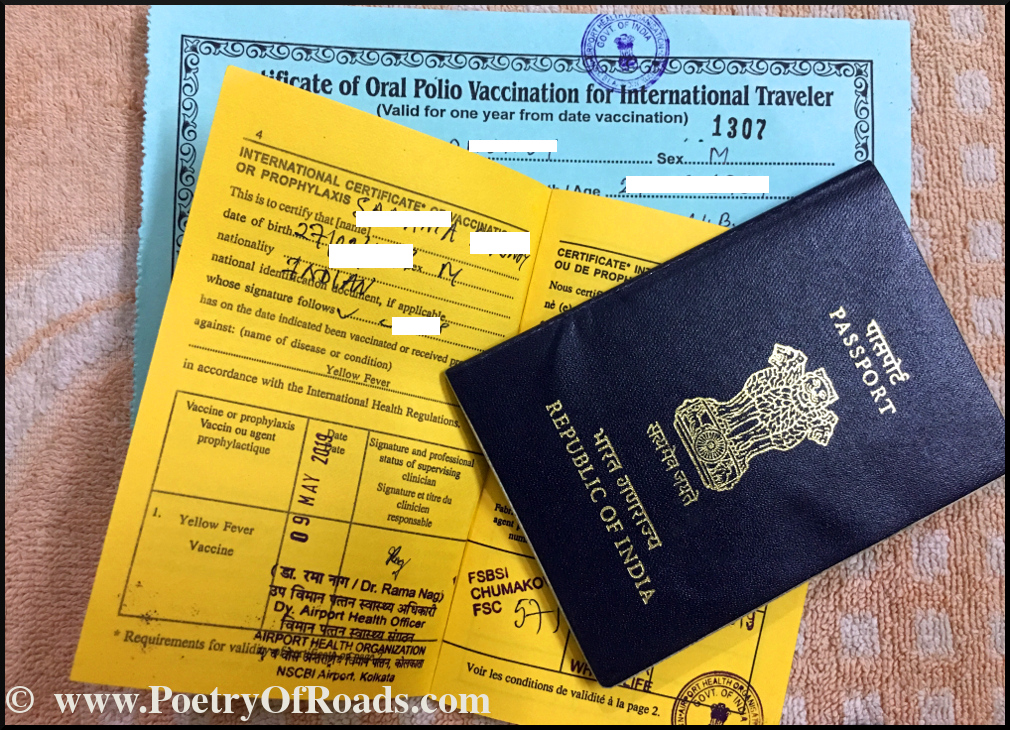

Vaccines protect us throughout life and at different ages, from birth to childhood, as teenagers and into old age. In most countries you will be given a vaccination card that tells you what vaccines you or your child have had and when the next vaccines or booster doses are due. It is important to make sure that all these vaccines are up to date.

It is important to make sure that all these vaccines are up to date.

If we delay vaccination, we are at risk of getting seriously sick. If we wait until we think we may be exposed to a serious illness – like during a disease outbreak – there may not be enough time for the vaccine to work and to receive all the recommended doses.

If you have missed any recommended vaccinations for you or your child, talk to your healthcare worker about catching up.

Why should I get vaccinated?

Without vaccines, we are at risk of serious illness and disability from diseases like measles, meningitis, pneumonia, tetanus and polio. Many of these diseases can be life-threatening. WHO estimates that childhood vaccines alone save over 4 million lives every year.

Although some diseases may have become uncommon, the germs that cause them continue to circulate in some or all parts of the world. In today’s world, infectious diseases can easily cross borders, and infect anyone who is not protected

In today’s world, infectious diseases can easily cross borders, and infect anyone who is not protected

Two key reasons to get vaccinated are to protect ourselves and to protect those around us. Because not everyone can be vaccinated – including very young babies, those who are seriously ill or have certain allergies – they depend on others being vaccinated to ensure they are also safe from vaccine-preventable diseases.

What diseases do vaccines prevent?

Vaccines protect against many different diseases, including:

- Cervical cancer

- Cholera

- COVID-19

- Diphtheria

- Ebola virus disease

- Hepatitis B

- Influenza

- Japanese encephalitis

- Measles

- Meningitis

- Mumps

- Pertussis

- Pneumonia

- Polio

- Rabies

- Rotavirus

- Rubella

- Tetanus

- Typhoid

- Varicella

- Yellow fever

Some other vaccines are currently under development or being piloted, including those that protect against Zika virus or malaria, but are not yet widely available globally.

Not all of these vaccinations may be needed in your country. Some may only be given prior to travel, in areas of risk, or to people in high-risk occupations. Talk to your healthcare worker to find out what vaccinations are needed for you and your family.

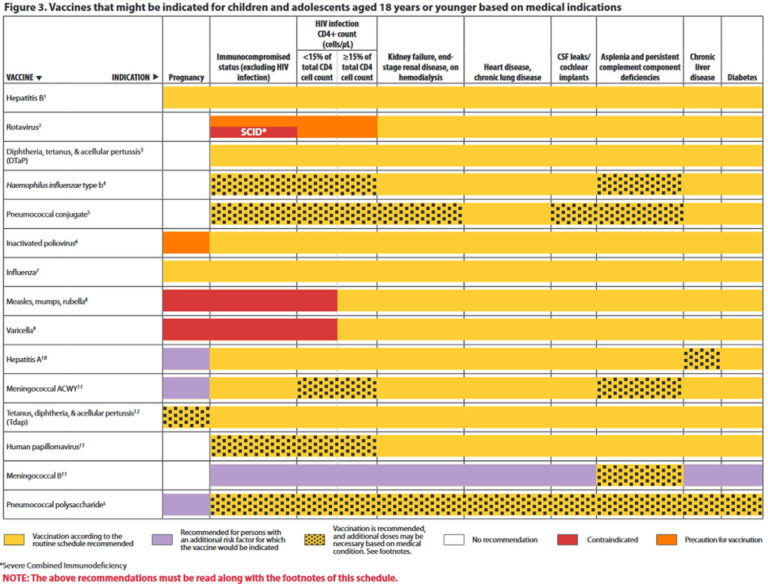

Who can get vaccinated?

Nearly everyone can get vaccinated. However, because of some medical conditions, some people should not get certain vaccines, or should wait before getting them. These conditions can include:

-

Chronic illnesses or treatments (like chemotherapy) that affect the immune system;

-

Severe and life-threatening allergies to vaccine ingredients, which are very rare;

-

If you have severe illness and a high fever on the day of vaccination.

These factors often vary for each vaccine. If you’re not sure if you or your child should get a particular vaccine, talk to your health worker. They can help you make an informed choice about vaccination for you or your child.

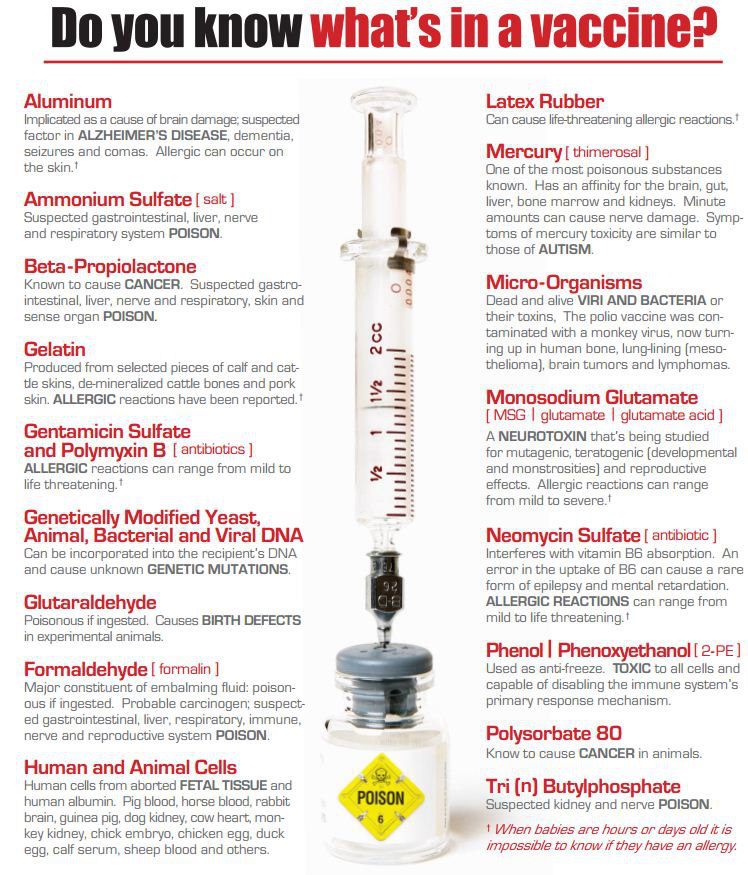

What is in a vaccine?

All the ingredients of a vaccine play an important role in ensuring a vaccine is safe and effective. Some of these include:

-

The antigen. This is a killed or weakened form of a virus or bacteria, which trains our bodies to recognize and fight the disease if we encounter it in the future.

-

Adjuvants, which help to boost our immune response. This means they help vaccines to work better.

-

Preservatives, which ensure a vaccine stays effective.

-

Stabilisers, which protect the vaccine during storage and transportation.

Vaccine ingredients can look unfamiliar when they are listed on a label. However, many of the components used in vaccines occur naturally in the body, in the environment, and in the foods we eat. All of the ingredients in vaccines – as well as the vaccines themselves - are thoroughly tested and monitored to ensure they are safe.

Are vaccines safe?

Vaccination is safe and side effects from a vaccine are usually minor and temporary, such as a sore arm or mild fever. More serious side effects are possible, but extremely rare.

More serious side effects are possible, but extremely rare.

Any licensed vaccine is rigorously tested across multiple phases of trials before it is approved for use, and regularly reassessed once it is introduced. Scientists are also constantly monitoring information from several sources for any sign that a vaccine may cause health risks.

Remember, you are far more likely to be seriously injured by a vaccine-preventable disease than by a vaccine. For example, tetanus can cause extreme pain, muscle spasms (lockjaw) and blood clots, measles can cause encephalitis (an infection of the brain) and blindness. Many vaccine-preventable diseases can even result in death. The benefits of vaccination greatly outweigh the risks, and many more illnesses and deaths would occur without vaccines.

More information about vaccine safety and development is available here.

Are there side effects from vaccines?

Like any medicine, vaccines can cause mild side effects, such as a low-grade fever, or pain or redness at the injection site. Mild reactions go away within a few days on their own.

Mild reactions go away within a few days on their own.

Severe or long-lasting side effects are extremely rare. Vaccines are continually monitored for safety, to detect rare adverse events.

Can a child be given more than one vaccine at a time?

Scientific evidence shows that giving several vaccines at the same time has no negative effect. Children are exposed to several hundred foreign substances that trigger an immune response every day. The simple act of eating food introduces new germs into the body, and numerous bacteria live in the mouth and nose.

When a combined vaccination is possible (e.g. for diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus), this means fewer injections and reduces discomfort for the child. It also means that your child is getting the right vaccine at the right time, to avoid the risk of contracting a potentially deadly disease.

Is there a link between vaccines and autism?

There is no evidence of any link between vaccines and autism or autistic disorders. This has been demonstrated in many studies, conducted across very large populations.

This has been demonstrated in many studies, conducted across very large populations.

The 1998 study which raised concerns about a possible link between measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism was later found to be seriously flawed and fraudulent. The paper was subsequently retracted by the journal that published it, and the doctor that published it lost his medical license. Unfortunately, its publication created fear that led to dropping immunization rates in some countries, and subsequent outbreaks of these diseases.

We must all ensure we are taking steps to share only credible, scientific information on vaccines, and the diseases they prevent.

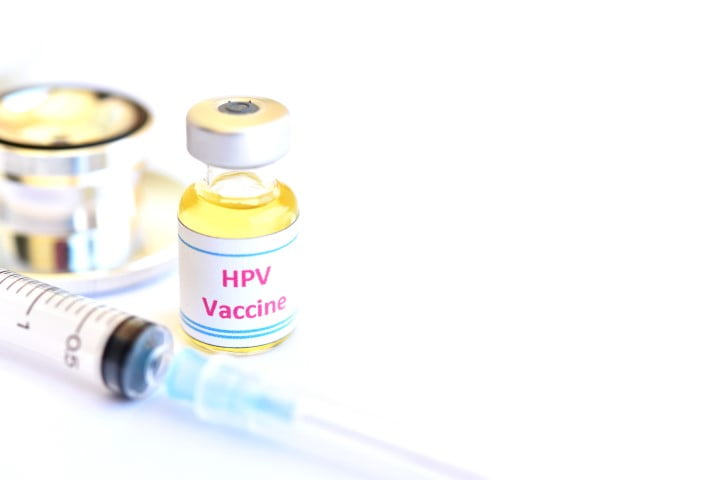

Should my daughter get vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV)?

Virtually all cervical cancer cases start with a sexually transmitted HPV infection. If given before exposure to the virus, vaccination offers the best protection against this disease. Following vaccination, reductions of up to 90% in HPV infections in teenage girls and young women have been demonstrated by studies conducted in Australia, Belgium, Germany, New Zealand, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States of America.

In studies, the HPV vaccine has been shown to be safe and effective. WHO recommends that all girls aged 9–14 years receive 2 doses of the vaccine, alongside cervical cancer screening later in life.

I still have questions about vaccination. What should I do?

If you have questions about vaccines be sure to talk to your healthcare worker. He or she can provide you with science-based advice about vaccination for you and your family, including the recommended vaccination schedule in your country.

When looking online for information about vaccines, be sure to consult only trustworthy sources. To help you find them, WHO has reviewed and ‘certified’ many websites across the world that provide only information based on reliable scientific evidence and independent reviews by leading technical experts. These websites are all members of the Vaccine Safety Net.

Immunization coverage

Immunization coverage- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Home/

- Newsroom/

- Fact sheets/

- Detail/

- Immunization coverage

WHO/H. Dicko

Dicko

A child is being vaccinated orally in Borno state, Nigeria

© Credits

Key facts

- Only 25 vaccine introductions other than COVID-19 vaccine were reported in 2021.

- Global coverage dropped from 86% in 2019 to 81% in 2021

- An estimated 25 million children under the age of 1 year did not receive basic vaccines, which is the highest number since 2009.

- The number of girls not vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV) increased by 3.5 million, compared to 2019.

- In 2021, the number of completely unvaccinated children increased by 5 million since 2019.

Overview

While immunization is one of the most successful public health interventions, coverage has plateaued over the last decade. The COVID-19 pandemic and associated disruptions have strained health systems, with 25 million children missing out on vaccination in 2021, 5.9 million more than in 2019 and the highest number since 2009.

During 2021, about 81% of infants worldwide (105 million infants) received 3 doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP3) vaccine, protecting them against infectious diseases that can cause serious illness and disability or be fatal.

Twenty five vaccine introductions were reported in 2021 (not including COVID-19 vaccine introductions). Although this is an increase from 17 introductions in 2020, it is well below the number of introductions of any year in the past two decades prior to 2020. This slowdown is likely to continue as countries focus on ongoing efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic.

Global immunization coverage 2021

A summary of global vaccination coverage in 2021 follows.

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) causes meningitis and pneumonia. Hib vaccine had been introduced in 192 Member States by the end of 2021. Global coverage with 3 doses of Hib vaccine is estimated at 71%. There is great variation between regions. The WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region and South-East Asia Region are each estimated to have 82% coverage, while it is only 29% in the WHO Western Pacific Region.

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that attacks the liver. Hepatitis B vaccine for infants had been introduced nationwide in 190 Member States by the end of 2021. Global coverage with 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine is estimated at 80%. In addition, 111 Member States introduced nationwide 1 dose of hepatitis B vaccine to newborns within the first 24 hours of life. Global coverage is 42% and is as high as 78% in the WHO Western Pacific Region, while it is only estimated to be at 17% in the WHO African Region.

Hepatitis B vaccine for infants had been introduced nationwide in 190 Member States by the end of 2021. Global coverage with 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine is estimated at 80%. In addition, 111 Member States introduced nationwide 1 dose of hepatitis B vaccine to newborns within the first 24 hours of life. Global coverage is 42% and is as high as 78% in the WHO Western Pacific Region, while it is only estimated to be at 17% in the WHO African Region.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract and can cause cervical cancer in women, other types of cancer, and genital warts in both men and women. Including 5 new introductions, 116 Member States have introduced HPV vaccine by the end of 2021. Since many large countries have not yet introduced the vaccine and vaccine coverage decreased in 2021 in many countries, global coverage with the first dose of HPV among girls is now estimated at 15%. This is a proportionally large reduction from 20% in 2019.

Meningitis A is an infection that is often deadly and leaves 1 in 5 affected individuals with long-term devastating sequelae. Before the introduction of MenAfriVac in 2010 – a revolutionary vaccine – meningitis serogroup A accounted for 80–85% of meningitis epidemics in the African meningitis belt. By the end of 2021, 350 million people in 24 out of the 26 countries in the meningitis belt had been vaccinated with MenAfriVac through campaigns. Thirteen countries had included MenAfriVac in their routine immunization schedule by 2021..

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus, which usually results in a high fever and rash, and can lead to blindness, encephalitis or death. By the end of 2021, 81% of children had received 1 dose of measles-containing vaccine by their second birthday, and 183 Member States had included a second dose as part of routine immunization and 71% of children received 2 doses of measles vaccine according to national immunization schedules.

Mumps is a highly contagious virus that causes painful swelling at the side of the face under the ears (the parotid glands), fever, headache and muscle aches. It can lead to viral meningitis. Mumps vaccine had been introduced nationwide in 123 Member States by the end of 2021.

Pneumococcal diseases include pneumonia, meningitis and febrile bacteraemia, as well as otitis media, sinusitis and bronchitis. Pneumococcal vaccine had been introduced in 154 Member States by the end of 2021, including 2 in some parts of the country, and global third dose coverage was estimated at 51%. There is great variation between regions. The WHO European Region is estimated to have 82% coverage, while it is only 19% in the WHO Western Pacific Region.

Polio is a highly infectious viral disease that can cause irreversible paralysis. In 2021, 80% of infants around the world received 3 doses of polio vaccine. In 2021, the coverage of infants receiving their first dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) in countries that are still using oral polio vaccine (OPV) is estimated at 79%. Targeted for global eradication, polio has been stopped in all countries except for Afghanistan and Pakistan. Until poliovirus transmission is interrupted in these countries, all countries remain at risk of importation of polio, especially vulnerable countries with weak public health and immunization services and travel or trade links to endemic countries.

Targeted for global eradication, polio has been stopped in all countries except for Afghanistan and Pakistan. Until poliovirus transmission is interrupted in these countries, all countries remain at risk of importation of polio, especially vulnerable countries with weak public health and immunization services and travel or trade links to endemic countries.

Rotaviruses are the most common cause of severe diarrhoeal disease in young children throughout the world. Rotavirus vaccine was introduced in 118 countries by the end of 2021, including 2 in some parts of the country. Global coverage was estimated at 49%.

Rubella is a viral disease which is usually mild in children, but infection during early pregnancy may cause fetal death or congenital rubella syndrome, which can lead to defects of the brain, heart, eyes and ears. Rubella vaccine was introduced nationwide in 173 Member States by the end of 2021, and global coverage was estimated at 66%.

Tetanus is caused by a bacterium which grows in the absence of oxygen, for example in dirty wounds or the umbilical cord if it is not kept clean. The spores of C. tetani are present in the environment irrespective of geographical location. It produces a toxin which can cause serious complications or death. Maternal and neonatal tetanus persist as public health problems in 12 countries, mainly in Africa and Asia.

Yellow fever is an acute viral haemorrhagic disease transmitted by infected mosquitoes. As of 2021, yellow fever vaccine had been introduced in routine infant immunization programmes in 36 of the 40 countries and territories at risk for yellow fever in Africa and the Americas. In these 40 countries and territories, coverage is estimated at 47%.

Key challenges

In 2021, 18.2 million infants did not receive an initial dose of DTP vaccine, pointing to a lack of access to immunization and other health services, and an additional 6. 8 million are partially vaccinated. Of the 25 million, more than 60% of these children live in 10 countries: Angola, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan and the Philippines.

8 million are partially vaccinated. Of the 25 million, more than 60% of these children live in 10 countries: Angola, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan and the Philippines.

Monitoring data at subnational levels is critical to helping countries prioritize and tailor vaccination strategies and operational plans to address immunization gaps and reach every person with life-saving vaccines.

WHO response

WHO is working with countries and partners to improve global vaccination coverage, including through these initiatives adopted by the World Health Assembly in August 2020.

Immunization Agenda 2030IA2030 sets an ambitious, overarching global vision and strategy for vaccines and immunization for the decade 2021–2030. It was co-created with thousands of contributions from countries and organizations around the world. It draws on lessons from the past decade and acknowledges continuing and new challenges posed by infectious diseases (e. g. Ebola, COVID-19).

g. Ebola, COVID-19).

The strategy has been designed to respond to the interests of every country and intends to inspire and align the activities of community, national, regional and global stakeholders towards achieving a world where everyone, everywhere fully benefits from vaccines for good health and well-being. IA2030 is operationalized through regional and national strategies and mechanisms to ensure ownership and accountability and a monitoring and evaluation framework to guide country implementation.

- Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy to Leave No One Behind

- Implementing the Immunization Agenda 2030: A Framework for Action

In 2020, the World Health Assembly adopted the global strategy towards eliminating cervical cancer. In this strategy, the first of the 3 pillars requires the introduction of the HPV vaccine in all countries and has set a target of reaching 90% coverage. With introduction currently in 57% of Member States, large investments towards introduction in low and middle-income countries will be required in the next 10 years as well as programme improvements to reach the 90% coverage targets in low and high-income settings alike will be required to reach the 2030 targets.

With introduction currently in 57% of Member States, large investments towards introduction in low and middle-income countries will be required in the next 10 years as well as programme improvements to reach the 90% coverage targets in low and high-income settings alike will be required to reach the 2030 targets.

- Vaccines and immunization

- World Immunization Week

- Global Vaccine Action Plan

- Global Health Observatory (GHO) data - Immunization

- More information on vaccines and immunization

Questions and answers – Vaccines and immunization: Myths and misconceptions

Questions and answers – What is vaccination?

Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?

Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find a country »

- A

- B

- in

- g

- D

- E 9000 R

- C

- T

- U

- F

- x

- C

- h

- Sh

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

003

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Questions and answers /

- Questions and answers /

- Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?

August 30, 2021 | FAQ

Revised August 10, 2021

What is vaccination?

Vaccination is a simple, safe and effective way to protect against diseases before a person comes into contact with their pathogens. Vaccination activates the body's natural defense mechanisms to build resistance to a range of infectious diseases and makes your immune system stronger.

Vaccination activates the body's natural defense mechanisms to build resistance to a range of infectious diseases and makes your immune system stronger.

Like diseases, vaccines train the immune system to produce specific antibodies. However, vaccines contain only killed or attenuated forms of the causative agents of a particular disease - viruses or bacteria - that do not lead to the disease and do not create the risk of complications associated with it.

Most vaccines are given by injection, although some are given by mouth. vaccines (given by mouth), and nasal spray vaccines (given through the nose).

What is the principle of the vaccine?

Vaccines reduce the risk of disease by activating natural defense mechanisms to build immunity to the pathogen. Vaccination provokes the body's immune response. Immune system:

- Recognizes pathogens such as viruses or bacteria.

- Starts production of antibodies. Antibodies are proteins naturally produced by the body's immune system to fight disease.

- Remembers the causative agent of the disease in order to fight it in the future. If this pathogen enters the body again, the immune system will quickly destroy it, preventing the development of the disease.

Thus, vaccination is a safe and rational way to induce an immune response in the body without the need to infect it with a particular disease.

Our immune system has a memory. By receiving one or more doses of a vaccine, we are usually protected against a particular disease for many years, decades, or even a lifetime. This is what makes vaccines so effective. Vaccines keep us from getting sick, which is much better than having to treat the disease when it has already begun.

When should I get vaccinated (or have my child vaccinated)?

Vaccines protect us throughout our lives and at all ages - from birth, through childhood, through adolescence and into old age. In most countries, people are given vaccination cards that tell you what vaccinations an adult or child has received and when the next vaccinations are due. It is important that all indicated vaccinations are up to date.

It is important that all indicated vaccinations are up to date.

By delaying vaccination, we put ourselves at risk of becoming seriously ill. If we wait until the moment when a vaccine is urgently needed - for example, if there is an outbreak of a disease - then it may be too late to get the desired effect of vaccination or all the necessary doses of the vaccine.

Why do I need to be vaccinated?

Without vaccination, we are at risk of serious diseases such as measles, meningitis, pneumonia, tetanus and polio. Many of these diseases are life threatening. The WHO estimates that childhood vaccines alone save more than 4 million lives each year.

Although some diseases are becoming less common, their pathogens continue to circulate in some or all regions of the world. In today's world, infectious diseases can easily cross borders and infect anyone who lacks immunity to them.

There are two main reasons to get vaccinated: to protect yourself and to protect others. Since some people, such as newborns and people with serious illnesses or those with certain allergies, may not be vaccinated, their protection against vaccine-preventable diseases depends on the availability of vaccinations in others.

Since some people, such as newborns and people with serious illnesses or those with certain allergies, may not be vaccinated, their protection against vaccine-preventable diseases depends on the availability of vaccinations in others.

Who should not be vaccinated?

Almost anyone can get vaccinated. However, for people with certain diseases and conditions, some vaccinations are contraindicated or should be deferred to a later date. These diseases and conditions may include:

- chronic diseases or treatments (eg chemotherapy) that suppress the immune system;

- extremely rare acute and life-threatening allergic reactions to vaccine components;

- severe illness at the time of vaccination. However, these children should be vaccinated as soon as they recover. Moderate malaise or subfebrile temperature is not a contraindication for vaccination.

Often these factors need to be considered depending on the type of vaccine. If you are not sure whether you or your child should get a particular vaccine, ask your doctor. Your doctor will help you make an informed decision about your or your child's vaccinations.

Your doctor will help you make an informed decision about your or your child's vaccinations.

What diseases do vaccines protect against?

vaccines protect against a number of diseases, including the following:

- Cervical Cancer

- cholera

- Covid-1

- 9000

- Pertussis

- Pneumonia

- Poliomyelitis

- Rabies

- Rotavirus

- Rubella

- Tetanus

- Typhoid fever

- Varicella

- Yellow fever

A number of vaccines for some other diseases, including Ebola or malaria, are currently under development or experimental use, but these vaccines have not yet been introduced in mass use throughout the world.

Not all vaccinations may be required in your country. Vaccinations for certain diseases may only be required for people traveling to certain countries or who are at increased risk due to their professional activities. Ask your doctor what vaccinations you and your family members need.

Why are vaccinations started at such an early age?

In their daily lives, young children may be in many different places and come into contact with a wide variety of people, thereby being at serious risk of infection. The WHO-recommended immunization schedule allows infants and young children to be protected as early as possible against a range of diseases. Often, infants and young children are most at risk of illness because their immune systems are not yet fully developed and their bodies are less able to fight off infections. Therefore, it is extremely important to vaccinate children according to the recommended schedule.

What is included in the vaccine?

All components of a vaccine play an important role in its safety and efficacy. The composition of vaccines, in particular, includes the following components:

- Antigen. This is a killed or weakened form of any microorganism - a virus or a bacterium - on which our body learns to recognize and destroy the causative agent of the disease if it encounters it in the future.

- Adjuvants that help enhance the body's immune response. Without them, vaccines would be less effective.

- Preservatives to keep vaccines effective.

- Stabilizers to preserve the vaccine during storage and transport.

The names of vaccine components written on vaccine packages can be confusing. However, many of them are naturally present in the body, environment and food. All of the components of vaccines, like the vaccines themselves, are subject to rigorous testing and monitoring for their safety.

Are vaccines safe?

Vaccination is safe and usually causes minor and temporary side effects, such as arm pain or mild fever. More serious side effects are possible, but they are extremely rare.

Any licensed vaccine is rigorously tested through several phases of clinical trials before it is approved for use and regularly evaluated after introduction. Scientists are also constantly monitoring information from a range of sources for signs that a given vaccine may pose a health risk.

It must be remembered that the risk of serious harm to health from a vaccine-preventable disease is much greater than the risk associated with vaccination. For example, tetanus can cause severe pain, convulsions and thrombosis, and measles can lead to encephalitis (infection of the brain) and blindness. Many vaccine-preventable diseases can even be fatal. The benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks, and without vaccines, the world would experience an order of magnitude more illness and death.

My child did not receive the recommended vaccinations on time. Is it too late to get the missing vaccinations?

In most cases, it is never too late to get the missing shots. Ask your doctor how and when you or your child can get the missing shots.

Do vaccines have side effects?

Like all medicines, vaccines can cause mild side effects such as low grade fever and pain or redness at the injection site. These symptoms usually go away on their own within a few days.

Severe or long-term side effects are extremely rare. The chance of experiencing a serious adverse body reaction to a vaccine is 1 in a million.

The safety of vaccines is subject to ongoing monitoring and is continuously monitored for rare adverse reactions.

How are vaccines developed and tested?

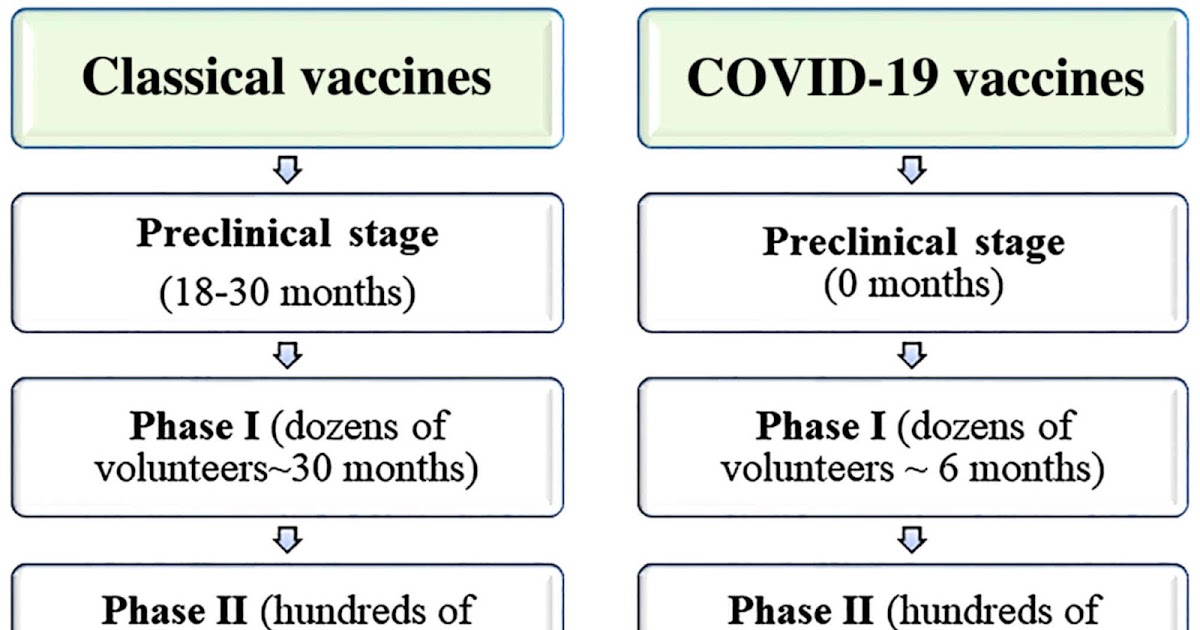

The most commonly used vaccines have been in use for decades, and every year millions of people receive them safely. Like all medicines, every vaccine must undergo extensive, rigorous testing to assess its safety before it can be introduced in countries.

Experimental vaccines are first tested in animals to evaluate their safety and ability to prevent disease. They are then tested in human clinical trials, which consist of three phases.

• During the first phase of the trial, the vaccine is given to a small number of volunteers to evaluate its safety, make sure it generates an immune response, and determine the correct dose.

• During the second phase of the trial, the vaccine is typically administered to hundreds of volunteers, who are closely monitored for any side effects and further evaluation of its ability to generate an immune response. Data on disease outcomes are also collected at this stage, if possible, but these data are usually not sufficient to provide a clear picture of the impact of the vaccine on the disease. Participants in this phase of the trial share the same characteristics (such as age and gender) as the people for whom the vaccine is intended. At this stage, some volunteers receive the vaccine and others do not, allowing comparisons to be made and conclusions about the vaccine to be made.

Data on disease outcomes are also collected at this stage, if possible, but these data are usually not sufficient to provide a clear picture of the impact of the vaccine on the disease. Participants in this phase of the trial share the same characteristics (such as age and gender) as the people for whom the vaccine is intended. At this stage, some volunteers receive the vaccine and others do not, allowing comparisons to be made and conclusions about the vaccine to be made.

• During the third phase of the trial, the vaccine is administered to thousands of volunteers, some of whom receive the study vaccine and some do not, as in the second phase of the trial. The data from both groups are carefully compared to determine whether the vaccine is safe and effective in protecting against the disease it is intended to target.

Following clinical trial results, a number of steps must be taken before a vaccine can be included in a national immunization program, including efficacy, safety, and manufacturing reviews for regulatory approval and public health policy approval.

Following the introduction of the vaccine, careful monitoring continues to be carried out to identify any unexpected unwanted side effects and further evaluate its effectiveness under conditions of regular use in even more people, which will allow understanding how to best use the vaccine to ensure the greatest protective effect. For more information on vaccine development and safety, click here.

Can a child have more than one vaccine at a time?

Scientific evidence shows that the simultaneous administration of several vaccines does not have negative consequences. Every day, children are exposed to several hundred foreign substances that trigger the body's immune response. A simple meal is accompanied by the entry of new microorganisms into the body, and many bacteria live in the nose and mouth.

The ability to combine multiple vaccines (such as diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus) reduces the number of injections and reduces discomfort for the child. In addition, it allows you to know for sure that the child received the right vaccinations at the right time and will not catch a potentially fatal disease.

In addition, it allows you to know for sure that the child received the right vaccinations at the right time and will not catch a potentially fatal disease.

Is there a link between vaccination and autism?

There is no evidence of any association between vaccination and autism spectrum disorders. This conclusion was drawn from the results of many studies conducted on very large groups of people.

In 1998, a study was published raising concerns about a possible link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism, but the study later found a number of serious misrepresentations and falsified information. The journal that published this work later withdrew it, and the doctor who wrote it lost his license to practice medicine. Unfortunately, due to fears caused by this publication, vaccination rates in some countries dropped sharply, which subsequently led to outbreaks of these diseases.

We all have a responsibility to take the necessary steps to disseminate only reliable, science-based information about vaccines and the diseases that vaccines help prevent.

Does my daughter need to be vaccinated against the human papillomavirus (HPV)?

Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by sexually transmitted HPV infection. Vaccination against HPV before a person comes into contact with this virus is the most effective means of protection against this disease. Studies in Australia, Belgium, Sweden, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Sweden showed that vaccination reduced the number of HPV infections among adolescent girls and young women to almost 90%.

Studies have proven the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine. WHO recommends that all girls aged 9–14 years be vaccinated with two doses of the HPV vaccine, and that women be periodically screened for cervical cancer later in life.

I have questions about vaccinations. Who should I contact?

If you have any questions about vaccinations, be sure to ask your doctor. He or she will be able to give you evidence-based information about vaccinations, including the recommended vaccination schedule in your country for you and your family members.

When looking for information about vaccines on the Internet, look only to trusted sources. To help you find these sources, WHO has reviewed and "certified" many websites in many languages around the world to contain only information based on sound scientific evidence and independent analysis by leading technical experts. All of these websites are part of the Vaccine Safety Net (www.vaccinesafetynet.org).

How does WHO contribute to vaccine safety?

WHO works to ensure that all people around the world are protected with safe and effective vaccines. To this end, we help countries build strong vaccine safety systems and apply strict international standards for vaccine regulation.

Together with scientists from around the world, WHO experts continuously monitor to ensure that vaccines are safe. We are also working with partners to assist countries in investigating and reporting potential problems.

Any unexpected side effects reported to WHO are evaluated by an independent panel of experts called the Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety.

What is a vaccine

Do you know what a vaccine is?

Vaccination (inoculation) is the introduction of medical immunobiological preparations into the human body to create specific immunity to infectious diseases.

Let's take a look at each part of this definition to understand what a vaccine is and how it works.

Part 1. Medical immunobiological preparation

All vaccines are medical immunobiological preparations, because they are administered under the supervision of a doctor and contain pathogens (biological) treated using a special technology against which it is planned to create immunity (immuno-).

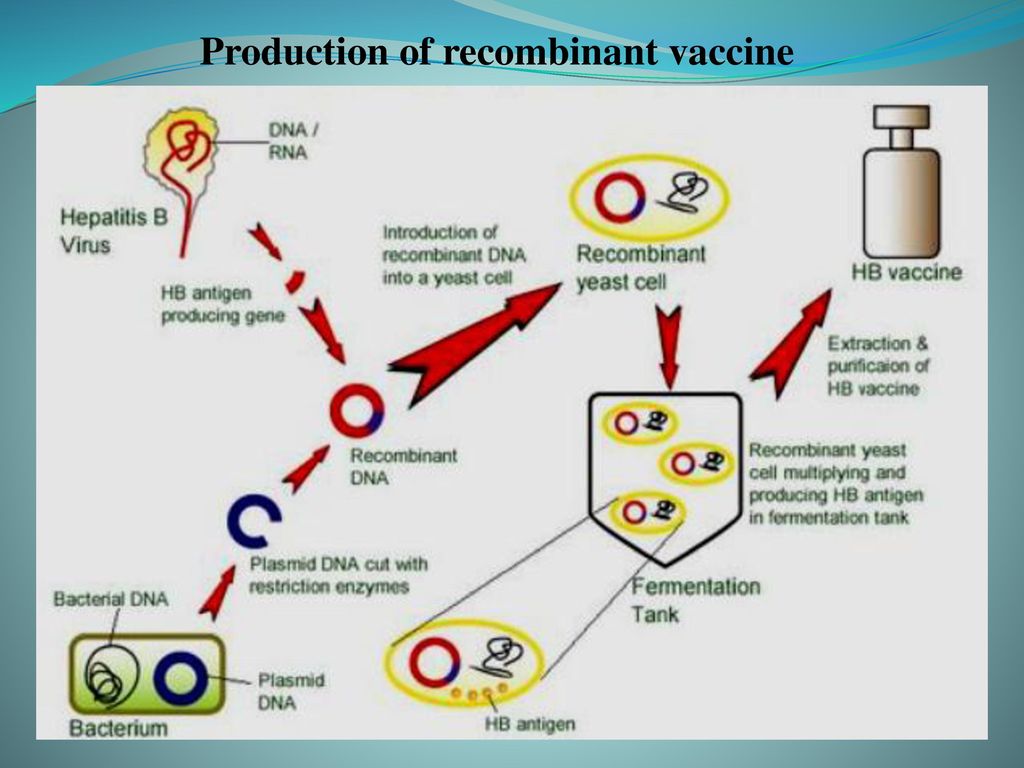

In addition to pathogens or their antigen parts, vaccines sometimes contain special permitted preservatives to maintain the sterility of the vaccine during storage, as well as the minimum allowable amount of those agents that were used to grow and inactivate microorganisms. For example, trace amounts of yeast cells used in the manufacture of hepatitis B vaccines, or trace amounts of egg protein, which are mainly used in the manufacture of influenza vaccines.

Sterility of preparations is ensured by preservatives recommended by the World Health Organization and international drug safety control organizations. These substances are approved for introduction into the human body.

The full composition of the vaccines is indicated in the instructions for their use. If a person has an established severe allergic reaction to any of the components of a particular vaccine, then this is usually a contraindication to its administration.

Part 2. Administration

Various methods are used to introduce the vaccine into the body, their choice is determined by the mechanism of formation of protective immunity, and the method of administration is indicated in the instructions for use.

Click on each method of administration to learn more about it.

Intramuscular route of vaccine administration

The most common route for administering vaccines. A good blood supply to the muscles guarantees both the maximum speed of immunity production and its maximum intensity, since a larger number of immune cells have the opportunity to “get acquainted” with vaccine antigens. The remoteness of the muscles from the skin provides a smaller number of adverse reactions, which, in the case of intramuscular injection, usually come down to only some discomfort during active movements in the muscles within 1-2 days after vaccination.

The remoteness of the muscles from the skin provides a smaller number of adverse reactions, which, in the case of intramuscular injection, usually come down to only some discomfort during active movements in the muscles within 1-2 days after vaccination.

Injection site: It is not recommended to administer vaccines in the buttocks. First, the needles of syringe doses of many vaccines are not long enough to reach the gluteal muscle, while, as is known, in both children and adults, the skin-fat layer can be of considerable thickness. If the vaccine is given in the buttocks, it may be given subcutaneously. It should also be remembered that any injection into the gluteal region is accompanied by a certain risk of damage to the sciatic nerve in people with atypical passage in the muscles.

The preferred site for the introduction of vaccines in children of the first years is the anterior-lateral surface of the thigh in its middle third. This is due to the fact that the muscle mass in this place is significant, despite the fact that the subcutaneous fat layer is less developed than in the gluteal region (especially in children who do not yet walk).

In children older than two years and adults, the preferred site for vaccine administration is the deltoid muscle (muscle thickening in the upper part of the shoulder, above the head of the humerus), due to the small thickness of the skin and sufficient muscle mass to administer 0.5-1.0 ml of the vaccine drug. In children of the first year of life, this place is usually not used due to insufficient development of muscle mass.

Vaccination Technique: Normally, the intramuscular injection is administered perpendicular, ie at a 90 degree angle, to the skin surface.

Advantages: good absorption of the vaccine and, as a result, high immunogenicity and the rate of immunity. Fewer local adverse reactions.

Disadvantages: The subjective perception of intramuscular injections by young children is somewhat worse than with other methods of vaccination.

Oral (i.e. by mouth)

The classic example of an oral vaccine is OPV, the live polio vaccine. Usually, live vaccines that protect against intestinal infections (poliomyelitis, typhoid fever) are administered in this way.

Usually, live vaccines that protect against intestinal infections (poliomyelitis, typhoid fever) are administered in this way.

Oral vaccination technique: a few drops of the vaccine are placed in the mouth. If the vaccine tastes bad, it can be dropped into either a piece of sugar or a cookie.

The advantages of this way of administering the vaccine are obvious: there is no injection, the simplicity of the method, its speed.

Disadvantages Disadvantages of oral administration of vaccines include spillage of the vaccine, inaccuracy in the dosage of the vaccine (part of the drug can be excreted in the feces without working).

Intradermal and dermal

The classic example of a vaccine intended for intradermal administration is BCG. Other examples of intradermal vaccines are live tularemia vaccine and smallpox vaccine. As a rule, live bacterial vaccines are administered intradermally, the spread of microbes from which throughout the body is highly undesirable.

Technique: The traditional site for cutaneous administration of vaccines is either the upper arm (above the deltoid muscle) or the forearm, midway between the wrist and elbow. For intradermal injection, special syringes with special, thin needles should be used. The needle is inserted upward with a cut, almost parallel to the surface of the skin, pulling the skin upward. In this case, it is necessary to make sure that the needle does not penetrate the skin. The correctness of the introduction will be indicated by the formation of a specific “lemon crust” at the injection site - a whitish skin tone with characteristic depressions at the exit site of the ducts of the skin glands. If a "lemon peel" does not form during administration, the vaccine is not administered correctly.

Benefits: Low antigenic load, relatively painless.

Disadvantages: Quite a complex vaccination technique requiring special training. The possibility of incorrectly administering the vaccine, which can lead to post-vaccination complications.

The possibility of incorrectly administering the vaccine, which can lead to post-vaccination complications.

Subcutaneous route of vaccine administration

Quite a traditional way of introducing vaccines and other immunobiological preparations in the territory of the former USSR, well known to all injections "under the shoulder blade". In general, this route is suitable for live and inactivated vaccines, although it is preferable to use it for live vaccines (measles-mumps-rubella, yellow fever, etc.).

Due to the fact that subcutaneous administration may slightly decrease the immunogenicity and the rate of development of the immune response, this route of administration is highly undesirable for the administration of vaccines against rabies and viral hepatitis B.

The subcutaneous route of vaccine administration is desirable for patients with bleeding disorders - the risk of bleeding in such patients after subcutaneous injection is significantly lower than with intramuscular injection.

Technique: The vaccination site can be either the shoulder (the lateral surface of the middle between the shoulder and elbow joints), and the anterior-lateral surface of the middle third of the thigh. With the index and thumb fingers, the skin is taken into a fold and, at a slight angle, the needle is inserted under the skin. If the subcutaneous layer of the patient is significantly expressed, the formation of a fold is not critical.

Benefits: Relatively simple technique, slightly less pain (not significant in children) compared to intramuscular injection. Unlike intradermal administration, a larger volume of vaccine or other immunobiological preparation can be administered. The accuracy of the administered dose (compared to the intradermal and oral route of administration).

Disadvantages: “Deposition” of the vaccine and, as a result, a lower rate of immunity development and its intensity when inactivated vaccines are administered. A greater number of local reactions - redness and induration at the injection site.

A greater number of local reactions - redness and induration at the injection site.

Aerosol, intranasal (i.e. through the nose)

It is believed that this route of vaccine administration improves immunity at the entrance gate of airborne infections (for example, with influenza) by creating an immunological barrier on the mucous membranes. At the same time, immunity created in this way is not stable, and at the same time, general (so-called systemic) immunity may not be sufficient to fight bacteria and viruses that have already entered the body through the barrier on the mucous membranes.

Aerosol Vaccination Technique: a few drops of the vaccine are instilled into the nose or sprayed into the nasal passages using a special device.

The advantages of this route of vaccine administration are clear: as with oral vaccination, aerosol administration does not require an injection; such vaccination creates excellent immunity on the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract.

The disadvantages of intranasal administration of vaccines can be considered a significant spill of the vaccine, loss of the vaccine (part of the drug enters the stomach).

Part 3: Specific immunity

Vaccines protect only against the diseases for which they are intended, this is the specificity of immunity. There are many causative agents of infectious diseases: they are divided into various types and subtypes, and specific vaccines with different possible protection spectra have already been created or are being created to protect against many of them.

So, for example, modern vaccines against pneumococcus (one of the causative agents of meningitis and pneumonia) can contain 10, 13 or 23 strains. And although scientists know about 100 subtypes of pneumococcus, vaccines include the most common in children and adults, for example, the widest spectrum of protection today - of 23 serotypes.

However, it must be borne in mind that a vaccinated person is likely to encounter some rare subtype of a microorganism that is not included in the vaccine and can cause disease, since the vaccine does not form protection against this rare microorganism that is not included in its composition.