Vaccination is not immunization

Deciding to Vaccinate Your Child: Common Concerns

Español (Spanish) | Print

Most parents choose to vaccinate their children according to the recommended schedule. But some parents may still have questions about vaccines.

Vaccines protect against diseases

Different types of vaccines work in different ways to offer protection. With all types of vaccines, your body will remember how to fight that virus in the future. It typically takes a few weeks after vaccination for the body to build up that protection.

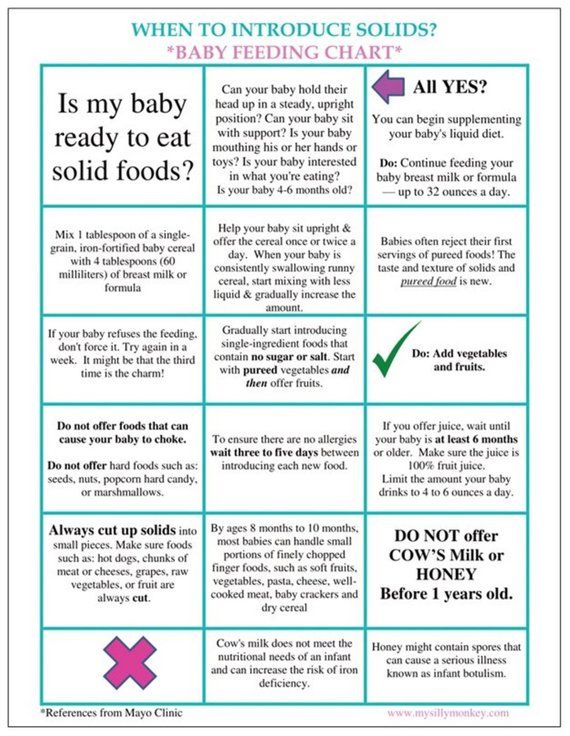

Strengthening your baby’s immune system

Immunity is the body’s way of preventing disease. Your baby’s immune system is not fully developed at birth which can put your baby at a greater risk for infection. Vaccines reduce your child’s risk of infection by working with the body’s natural defenses to help safely develop protection against disease.

Children are exposed to thousands of germs every day. This happens through the food they eat, air they breathe, and things they put in their mouth.

Babies are born with immune systems that can fight most germs, but there are some serious and even deadly diseases they can’t handle. That’s why they need vaccines to strengthen their immune system.

Vaccines use very small amounts of antigens to help your child’s immune system recognize and learn to fight serious diseases. Antigens are parts of germs that cause the body’s immune system to go to work.

Learn more about how vaccines work with the body’s immune system and different types of immunity.

Vaccine ingredients

Today’s vaccines use only the ingredients they need to be as safe and effective as possible. All ingredients of vaccines play necessary roles either in making the vaccine, triggering the body to develop immunity, or in ensuring that the final product is safe and effective. Some of these include:

- Adjuvants help boost the body’s response to a vaccination. (Also found in antacids, antiperspirants, etc.

)

) - Stabilizers help keep a vaccine effective after it is manufactured. (Also found in foods such as Jell-O® and resides in the body naturally)

- Formaldehyde is used to prevent contamination by bacteria during the vaccine manufacturing process. It resides in body naturally (more in body than vaccines). (Also found in environment, preservatives, and household products.)

- Thimerosal is also used during the manufacturing process but is no longer an ingredient in any vaccine except multi-dose vials of the flu vaccine. Single dose vials of the flu vaccine are available as an alternative. No reputable scientific studies have found an association between thimerosal in vaccines and autism.

Some websites may claim that ingredients are harmful, make sure you seek information from credible sources.

Vaccines are safe

Before a new vaccine is ever given to people, extensive lab testing is done. Once testing in people begins, it can sometimes take years before clinical studies are complete and the vaccine is licensed.

Once testing in people begins, it can sometimes take years before clinical studies are complete and the vaccine is licensed.

Once a vaccine is licensed, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), CDC, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and other federal agencies routinely monitor its use and investigate any potential safety concerns.

CDC and the FDA take many steps to make sure vaccines are very safe both before and after the public begins using the vaccine. Making sure vaccines are safe is a priority for CDC.

Mild side effects are expected

Vaccines, like medicine, can have some side effects. But most people who get vaccinated have mild or no side effects. The most common side effects may include fever, tiredness, body aches, and redness, swelling, and tenderness at the site where the shot was given. Mild reactions usually go away on their own within a few days. Serious, long lasting side effects are extremely rare.

If you have questions or concerns about a vaccine, talk with your child’s doctor. Learn about the safety of each recommended vaccine.

Why your child should get vaccinated

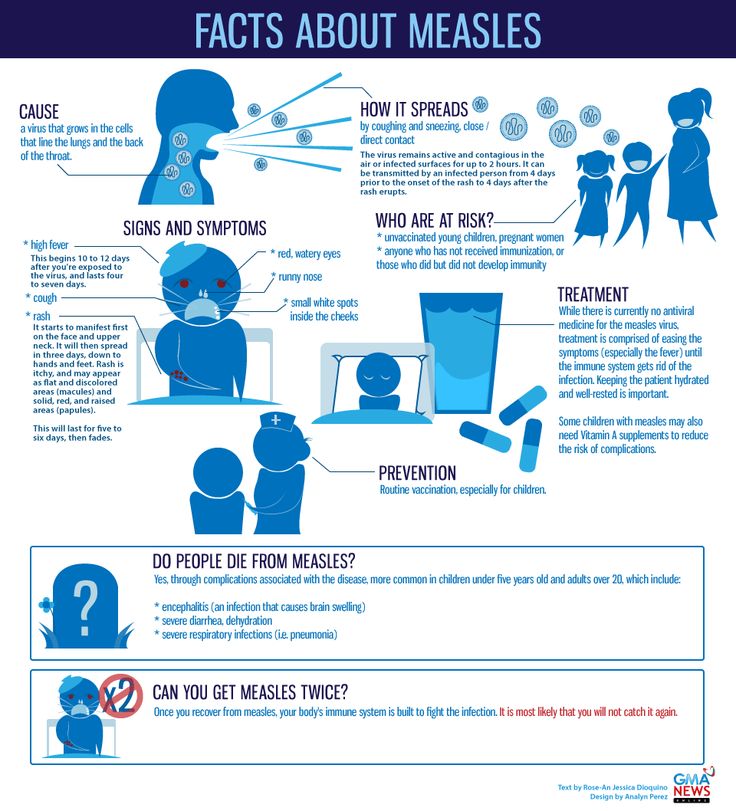

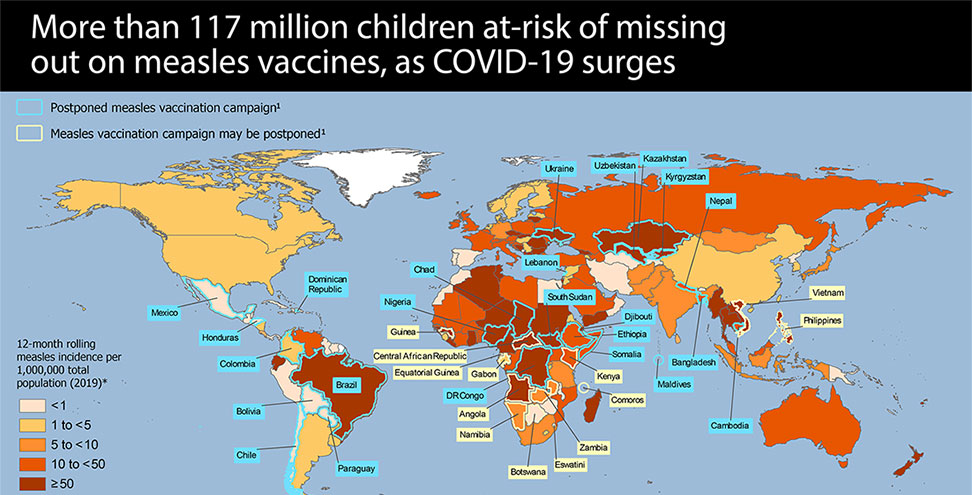

Vaccines can prevent serious diseases that once killed or harmed many infants, children, and adults. Without vaccines, your child is at risk for serious illness or even death from diseases like measles and whooping cough.

MEASLES: The United States had more than 1,200 cases of measles in 2019. This was the greatest number of cases reported in the U.S. since 1992 and since measles was declared eliminated in 2000.

It is always better to prevent a disease than to treat it after it occurs.

- Vaccination is a highly effective, safe, and easy way to help keep your family healthy.

- The timing of vaccination is based on how your child’s immune system responds to vaccines at various ages and how likely your child may be exposed to disease.

- Vaccines are tested to ensure they are safe and effective for children to receive at the recommended ages.

CDC vaccine information statements (VISs) explain both the benefits and risks of a vaccine. VISs are available for each vaccine.

The Vaccines for Children (VFC) Program

Common Vaccine Safety Concerns

Top of Page

Addressing vaccine hesitancy - PMC

1. Public Health Agency of Canada . Canadian immunization guide. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2016. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/canadian-immunization-guide.html. Accessed 2017 Nov 10. [Google Scholar]

2. Greenwood B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1645):20130433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Public Health Agency of Canada . Vaccine preventable disease surveillance report to December 31, 2015. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2017. Available from: www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/vaccine-preventable-disease-surveillance-report-december-31-2015/vaccine-preventable-disease-eng.pdf. Accessed 2018 Apr 20. [Google Scholar]

Available from: www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/vaccine-preventable-disease-surveillance-report-december-31-2015/vaccine-preventable-disease-eng.pdf. Accessed 2018 Apr 20. [Google Scholar]

4. Public Health Agency of Canada . The Chief Public Health Officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada 2013 — immunization and vaccine preventable diseases — staying protected. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2013. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/chief-public-health-officer-report-on-state-public-health-canada-2013-infectious-disease-never-ending-threat/immunization-and-vaccine-preventable-diseases-staying-protected.html. Accessed 2018 Apr 18. [Google Scholar]

5. Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DL. “Herd immunity”: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):911–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Dubé E, Gagnon D, Ouakki M, Bettinger JA, Guay M, Halperin S, et al. Understanding vaccine hesitancy in Canada: results of a consultation study by the Canadian Immunization Research Network. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dubé E, Gagnon D, Ouakki M, Bettinger JA, Guay M, Halperin S, et al. Understanding vaccine hesitancy in Canada: results of a consultation study by the Canadian Immunization Research Network. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, Clemens J, Datta SK, John TJ, et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(2):81–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Dubé E, Bettinger JA, Fisher WA, Naus M, Mahmud SM, Hilderman T. Vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and refusal in Canada: challenges and potential approaches. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2016;42(12):246–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Gowda C, Dempsey AF. The rise (and fall?) of parental vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1755–62. Epub 2013 Jun 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Public Health Agency of Canada . Vaccine coverage in Canadian children: results from the 2013 Childhood National Immunization Coverage Survey (CNICS) Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

11. Public Health Agency of Canada . Vaccination coverage goals and vaccine preventable disease reduction targets by 2025. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2017. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization-vaccine-priorities/national-immunization-strategy/vaccination-coverage-goals-vaccine-preventable-diseases-reduction-targets-2025.html?wbdisable=true#1.1.2. Accessed 2018 Feb 1. [Google Scholar]

12. Scheifele DW, Halperin SA, Bettinger JA. Childhood immunization rates in Canada are too low: UNICEF. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19(5):237–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Public Health Agency of Canada . Pertussis (whooping cough) Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/vaccine-preventable-diseases/pertussis-whooping-cough/health-professionals.html. Accessed 2018 Apr 18. [Google Scholar]

14. National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases . Disease debrief: mumps. Winnipeg, MB: National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases; 2017. Available from: nccid.ca/debrief/mumps. Accessed 2018 Apr 18. [Google Scholar]

National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases . Disease debrief: mumps. Winnipeg, MB: National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases; 2017. Available from: nccid.ca/debrief/mumps. Accessed 2018 Apr 18. [Google Scholar]

15. MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4. Epub 2015 Apr 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Busby C, Jacobs A, Muthukumaran R. Commentary 477. In need of a booster: how to improve childhood vaccination coverage in Canada. Toronto, ON: CD Howe Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

17. Leask J. Target the fence-sitters. Nature. 2011;473(7348):443–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization. World Health Organization . Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: www.who.int.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf. Accessed 2017 Nov 30. [Google Scholar]

Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: www.who.int.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf. Accessed 2017 Nov 30. [Google Scholar]

20. EKOS Research Associates Inc . Survey of parents on key issues related to immunization. Final report. Ottawa, ON: EKOS Research Associates Inc; 2011. Available from: www.ekospolitics.com/articles/0719.pdf. Accessed 2018 Feb 1. [Google Scholar]

21. Greenberg J, Dubé E, Driedger M. Vaccine hesitancy: in search of the risk communication comfort zone. PLoS Curr. 2017;9 ecurrents.outbreaks. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Edwards KM, Hackell JM, Committee on Infectious Diseases. Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine Countering vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20162146. pii: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Kata A. Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm—an overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3778–89. Epub 2011 Dec 13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anti-vaccine activists, Web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm—an overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3778–89. Epub 2011 Dec 13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Wheeler M, Buttenheim AM. Parental vaccine concerns, information source, and choice of alternative immunization schedules. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1782–9. Epub 2013 Jul 30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. British Columbia Immunization Committee Professional Education Working Group . Immunization communication tool for immunizers. Vancouver, BC: Provincial Health Services Authority; 2013. Available from: www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Guidelines%20and%20Forms/Guidelines%20and%20Manuals/Immunization/Vaccine%20Safety/BCCDCICT_300315.pdf. Accessed 2017 Nov 30. [Google Scholar]

26. Henrikson NB, Opel DJ, Grothaus L, Nelson J, Scrol A, Dunn J, et al. Physician communication training and parental vaccine hesitancy: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):70–9. Epub 2015 Jun 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):70–9. Epub 2015 Jun 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Autism Science Foundation . Making the CASE for vaccines: a new model for talking to parents about vaccines. New York, NY: Autism Science Foundation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

28. Diekema DS. Provider dismissal of vaccine-hesitant families: misguided policy that fails to benefit children. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(12):2661–2. Epub 2013 Sep 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, Cheater F, Bedford H, Rowles G. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;(12):154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Trivedi D. Cochrane review summary: face-to-face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2014;15(4):339–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Talking with parents about vaccines for infants. Bethesda, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/downloads/talk-infants-508.pdf. Accessed 2018 Apr 18. [Google Scholar]

Bethesda, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/downloads/talk-infants-508.pdf. Accessed 2018 Apr 18. [Google Scholar]

32. Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Salas HS, Devere V, et al. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037–46. Epub 2013 Nov 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. MacDonald N, Finlay J. Working with vaccine-hesitant parents. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(5):265–7. [Google Scholar]

34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Parents’ guide to childhood immunizations: frequently asked questions. Bethesda, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. Available from: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/tools/parents-guide/parents-guide-part4.html. Accessed 2017 Nov 3. [Google Scholar]

35. Alberta Health Services . Common questions about immunizations and immunity. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services; 2017. Available from: http://immunizealberta.ca/i-need-know-more/common-questions/immunizations-and-immunity. Accessed 2017 Nov 10. [Google Scholar]

Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services; 2017. Available from: http://immunizealberta.ca/i-need-know-more/common-questions/immunizations-and-immunity. Accessed 2017 Nov 10. [Google Scholar]

36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Infant immunizations FAQs. Bethesda, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. Available from: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/parents/parent-questions.html. Accessed 2017 Oct 27. [Google Scholar]

37. World Health Organization . Questions and answers on immunization and vaccine safety. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: www.who.int/features/qa/84/en. Accessed 2017 Nov 10. [Google Scholar]

38. Alberta Health Services . Common questions about vaccine safety. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Health Services; 2017. Available from: immunizealberta.ca/i-need-know-more/common-questions/vaccine-safety. Accessed 2017 Nov 10. [Google Scholar]

39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Talking with parents about vaccines for infants. Strategies for healthcare providers. Bethesda, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Available from: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patiented/conversations/downloads/talk-infants-color-office.pdf. Accessed 2017 Nov 3. [Google Scholar]

Talking with parents about vaccines for infants. Strategies for healthcare providers. Bethesda, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Available from: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/patiented/conversations/downloads/talk-infants-color-office.pdf. Accessed 2017 Nov 3. [Google Scholar]

40. Healy CM, Pickering LK. How to communicate with vaccine-hesitant parents. Pediatrics. 2011;127(Suppl 1):S127–33. Epub 2011 Apr 18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Immunize Canada . Questions and answers. Ottawa, ON: Immunize Canada; 2018. Available from: immunize.ca/questions-and-answers. Accessed 2019 Jan 29. [Google Scholar]

42. Immunization Action Coalition . Quick answers to tough questions: vaccine talking points for healthcare professionals. Saint Paul, MN: Immunization Action Coalition; 2017. Available from: www.immunize.org/catg.d/s8030.pdf. Accessed 2017 Nov 5. [Google Scholar]

43. Institute of Medicine (US) Immunization Safety Review Committee . Immunization safety review: vaccines and autism. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Immunization safety review: vaccines and autism. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

44. MacDonald NE, Law BJ. Canada’s eight-component vaccine safety system: a primer for health care workers. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22(4):e13–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Canadian Medical Protective Association . Duties and responsibilities. Expectations of physicians in practice. How to address vaccine hesitancy and refusal by patients or their legal guardians. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Medical Protective Association; 2017. Available from: www.cmpa-acpm.ca/en/advice-publications/browse-articles/2017/how-to-address-vaccine-hesitancy-and-refusal-by-patients-or-their-legal-guardians. Accessed 2019 Jan 24. [Google Scholar]

46. Public Health Agency of Canada . A parent’s guide to vaccination. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018. Available from: www.canada.ca/content/dam/phacaspc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/parent-guide-vaccination/pgi-gpv-eng. pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 24. [Google Scholar]

pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 24. [Google Scholar]

47. Canadian Paediatric Society . Choosing not to vaccinate your child? Know your risks and responsibilities. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2016. Available from: www.caringforkids.cps.ca/uploads/handout_images/CFK_tearsheet-ENG(post).pdf. Accessed 2019 Jan 24. [Google Scholar]

48. Moore DL, editor. Your child’s best shot: a parent’s guide to vaccination. 4th ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

49. Frew PM, Lutz CS. Interventions to increase pediatric vaccine uptake: an overview of recent findings. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2503–11. Epub 2017 Sep 26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Glanz JM, Wagner NM, Narwaney KJ, Shoup JA, McClure DL, McCormick EV, et al. A mixed methods study of parental vaccine decision making and parent-provider trust. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(5):481–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Saitoh A, Saitoh A, Sato I, Shinozaki T, Kamiya H, Nagata S. Effect of stepwise perinatal immunization education: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2017;35(12):1645–51. Epub 2017 Feb 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saitoh A, Saitoh A, Sato I, Shinozaki T, Kamiya H, Nagata S. Effect of stepwise perinatal immunization education: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2017;35(12):1645–51. Epub 2017 Feb 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Hu Y, Chen Y, Wang Y, Song Q, Li Q. Prenatal vaccination education intervention improves both the mothers’ knowledge and children’s vaccination coverage: evidence from randomized controlled trial from eastern China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(6):1–8. Epub 2017 Feb 21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Opel DJ, Mangione-Smith R, Robinson JD, Heritage J, DeVere V, Salas HS, et al. The influence of provider communication behaviors on parental vaccine acceptance and visit experience. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):1998–2004. Epub 2015 Mar 19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Let’s talk about protection. Enhancing childhood vaccination uptake. Communication guide for healthcare providers. Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2016. Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/lets-talk-about-protection-vaccination-guide.pdf. Accessed 2017 Dec 30. [Google Scholar]

Stockholm, Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2016. Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/lets-talk-about-protection-vaccination-guide.pdf. Accessed 2017 Dec 30. [Google Scholar]

55. Maglione MA, Das L, Raaen L, Smith A, Chari R, Newberry S, et al. Safety of vaccines used for routine immunization of US children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):325–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Betsch C, Sachse K. Debunking vaccination myths: strong risk negations can increase perceived vaccination risks. Health Psychol. 2013;32(2):146–55. Epub 2012 Mar 12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Scherer LD, Shaffer VA, Patel N, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Can the vaccine adverse event reporting system be used to increase vaccine acceptance and trust? Vaccine. 2016;34(21):2424–9. Epub 2016 Apr 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Thomson A, Watson M. Vaccine hesitancy: a vade mecum v1.0. Vaccine. 2016;34(17):1989–92. Epub 2016 Jan 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2016;34(17):1989–92. Epub 2016 Jan 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Kempe A, Daley MF, McCauley MM, Crane LA, Suh CA, Kennedy AM, et al. Prevalence of parental concerns about childhood vaccines: the experience of primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(5):548–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Horne Z, Powell D, Hummel JE, Holyoak KJ. Countering antivaccination attitudes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(33):10321–4. Epub 2015 Aug 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e835–42. Epub 2014 Mar 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Shelby A, Ernst K. Story and science: how providers and parents can utilize storytelling to combat anti-vaccine misinformation. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1795–801. Epub 2013 Jun 28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Connors JT, Slotwinski KL, Hodges EA. Provider-parent communication when discussing vaccines: a systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;33:10–5. Epub 2016 Nov 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;33:10–5. Epub 2016 Nov 15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Benin AL, Wisler-Scher DJ, Colson E, Shapiro ED, Holmboe ES. Qualitative analysis of mothers’ decision-making about vaccines for infants: the importance of trust. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1532–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Taddio A, McMurtry CM, Shah V, Riddell RP, Chambers CT, Noel M, et al. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ. 2015;187(13):975–82. Epub 2015 Aug 24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Dubé E, Gagnon D, Zhou Z, Deceuninck G. Parental vaccine hesitancy in Quebec (Canada) PLoS Curr. 2016;8 ecurrents.outbreaks. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Smith PJ, Humiston SG, Marcuse EK, Zhao Z, Dorell CG, Howes C, et al. Parental delay or refusal of vaccine doses, childhood vaccination coverage at 24 months of age, and the Health Belief Model. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 2):135–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Betsch C. Advocating for vaccination in a climate of science denial. Nat Microbiol. 2017;(2):17106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Betsch C. Advocating for vaccination in a climate of science denial. Nat Microbiol. 2017;(2):17106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Gagneur A, Lemaître T, Carrier N, Farrands A, Petit G. Post-partum vaccination promotion intervention using motivational interviewing techniques improves vaccination coverage during infancy. stract presented at: European Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases 2016; 2016 May 10–14; Brighton, UK. [Google Scholar]

70. Quadri-Sheriff M, Hendrix KS, Downs SM, Sturm LA, Zimet GD, Finnell SM. The role of herd immunity in parents’ decision to vaccinate children: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):522–30. Epub 2012 Aug 27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?

Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 O

- P

- R

- S

- T

- Y

- F

- X

- C

- h

- Sh

- Sh

- K.

- E

- U

- I

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- Newsletter

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- A

- B

- B

- g

- D

- E

- F

- K

- L

- N

- P

- R

- C

- T

- U

- x

- h

- Sh

- 9000 nine0005

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting nine0005

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Highlights "

- About WHO »

- General director

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Questions and answers /

- Questions and answers /

- Vaccines and immunization: What is vaccination?

August 30, 2021 | FAQ

Revised August 10, 2021

What is vaccination?

Vaccination is a simple, safe and effective way to protect against diseases before a person comes into contact with their pathogens. Vaccination activates the body's natural defense mechanisms to build resistance to a range of infectious diseases and makes your immune system stronger. nine0285

Vaccination activates the body's natural defense mechanisms to build resistance to a range of infectious diseases and makes your immune system stronger. nine0285

Like diseases, vaccines train the immune system to produce specific antibodies. However, vaccines contain only killed or attenuated forms of the causative agents of a particular disease - viruses or bacteria - that do not lead to the disease and do not create the risk of complications associated with it.

Most vaccines are given by injection, although some are given by mouth. vaccines (given by mouth), and nasal spray vaccines (given through the nose).

What is the principle of the vaccine? nine0285

Vaccines reduce the risk of disease by activating natural defense mechanisms to build immunity to the pathogen. Vaccination provokes the body's immune response. Immune system:

- Recognizes pathogens such as viruses or bacteria.

- Starts production of antibodies. Antibodies are proteins naturally produced by the body's immune system to fight disease.

- Remembers the causative agent in order to deal with it in the future. If this pathogen enters the body again, the immune system will quickly destroy it, preventing the development of the disease. nine0005

Thus, vaccination is a safe and rational way to induce an immune response in the body without the need to infect it with a particular disease.

Our immune system has a memory. By receiving one or more doses of a vaccine, we are usually protected against a particular disease for many years, decades, or even a lifetime. This is what makes vaccines so effective. Vaccines keep us from getting sick, which is much better than having to treat the disease when it has already begun. nine0285

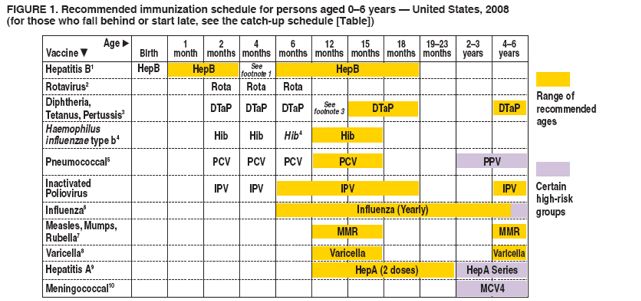

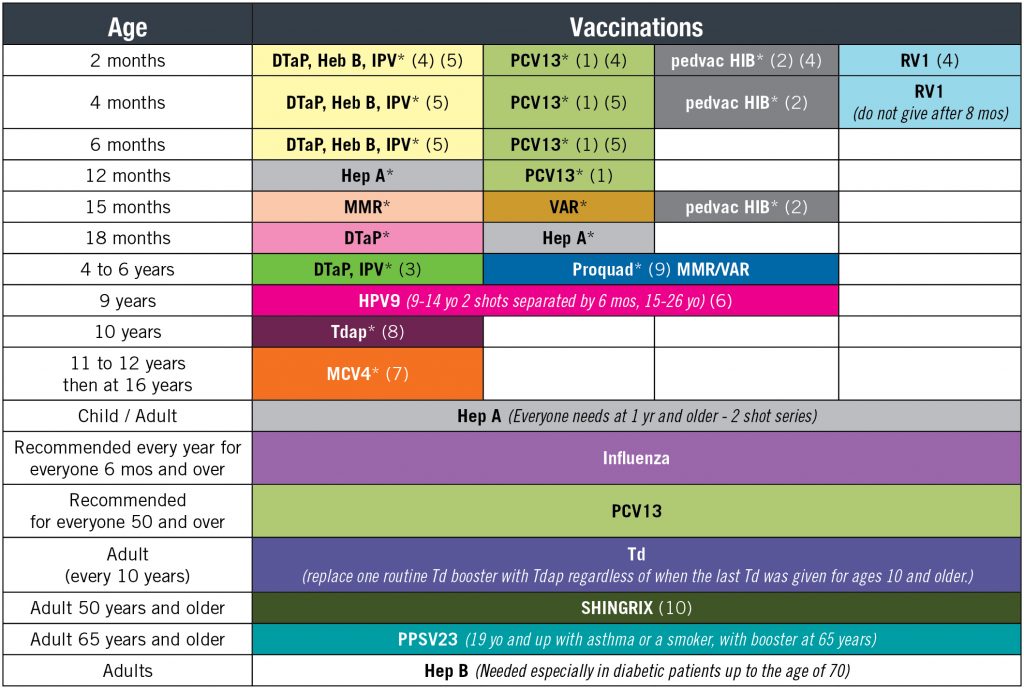

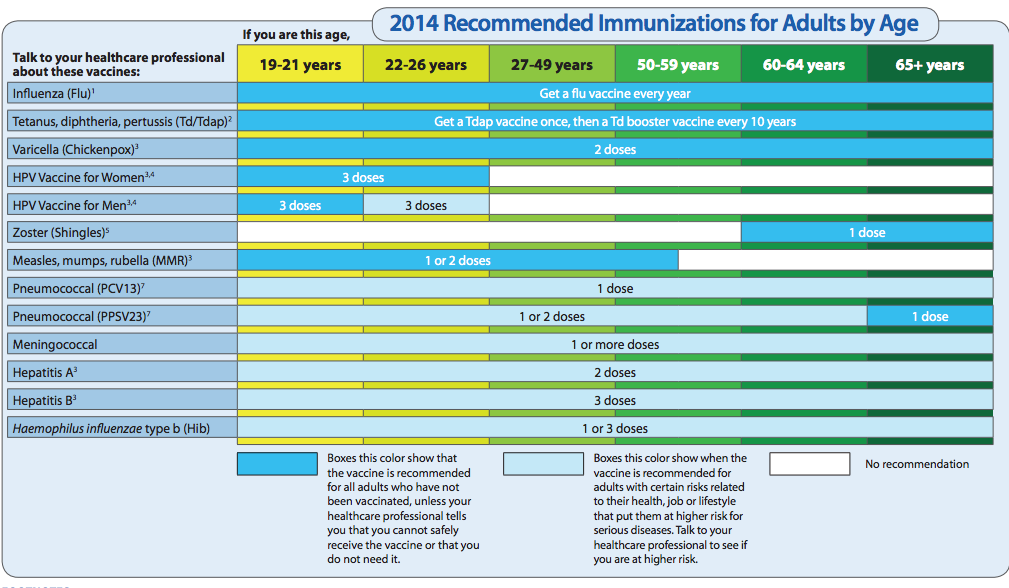

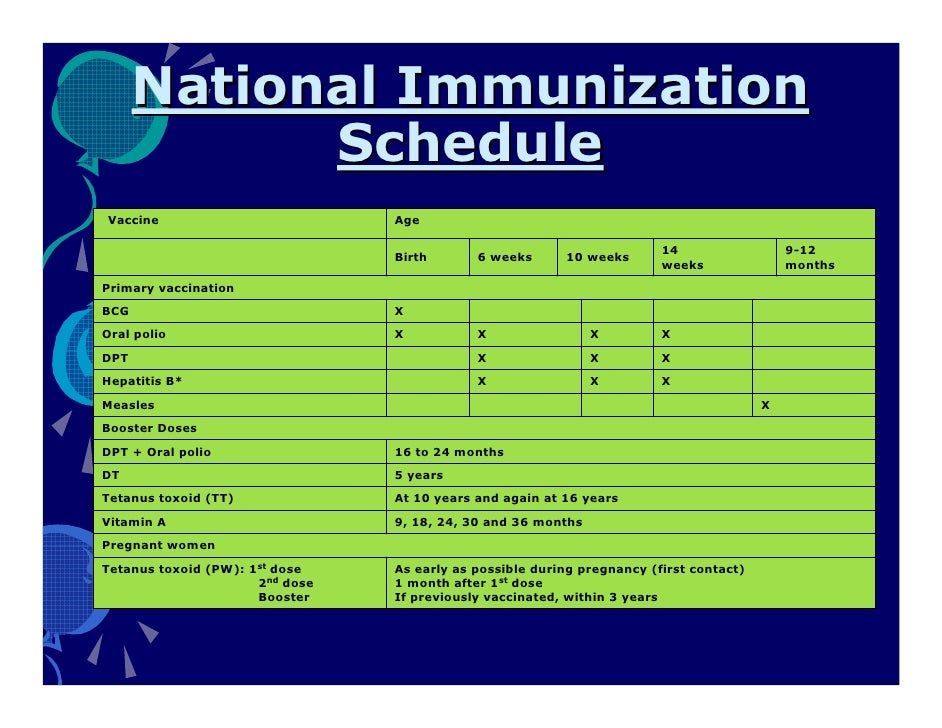

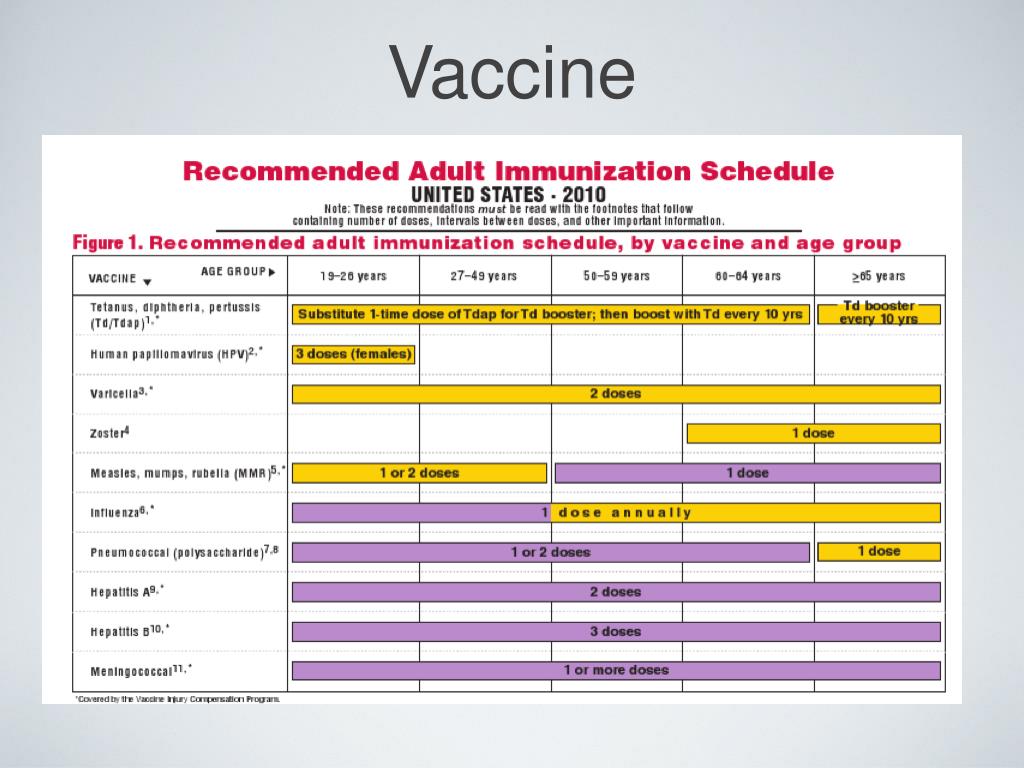

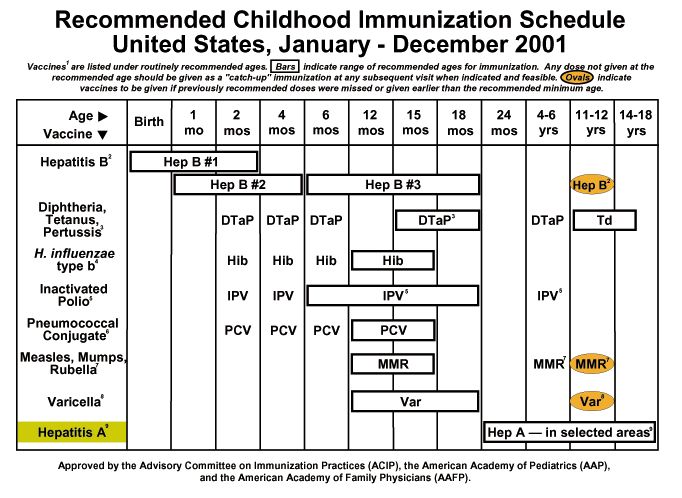

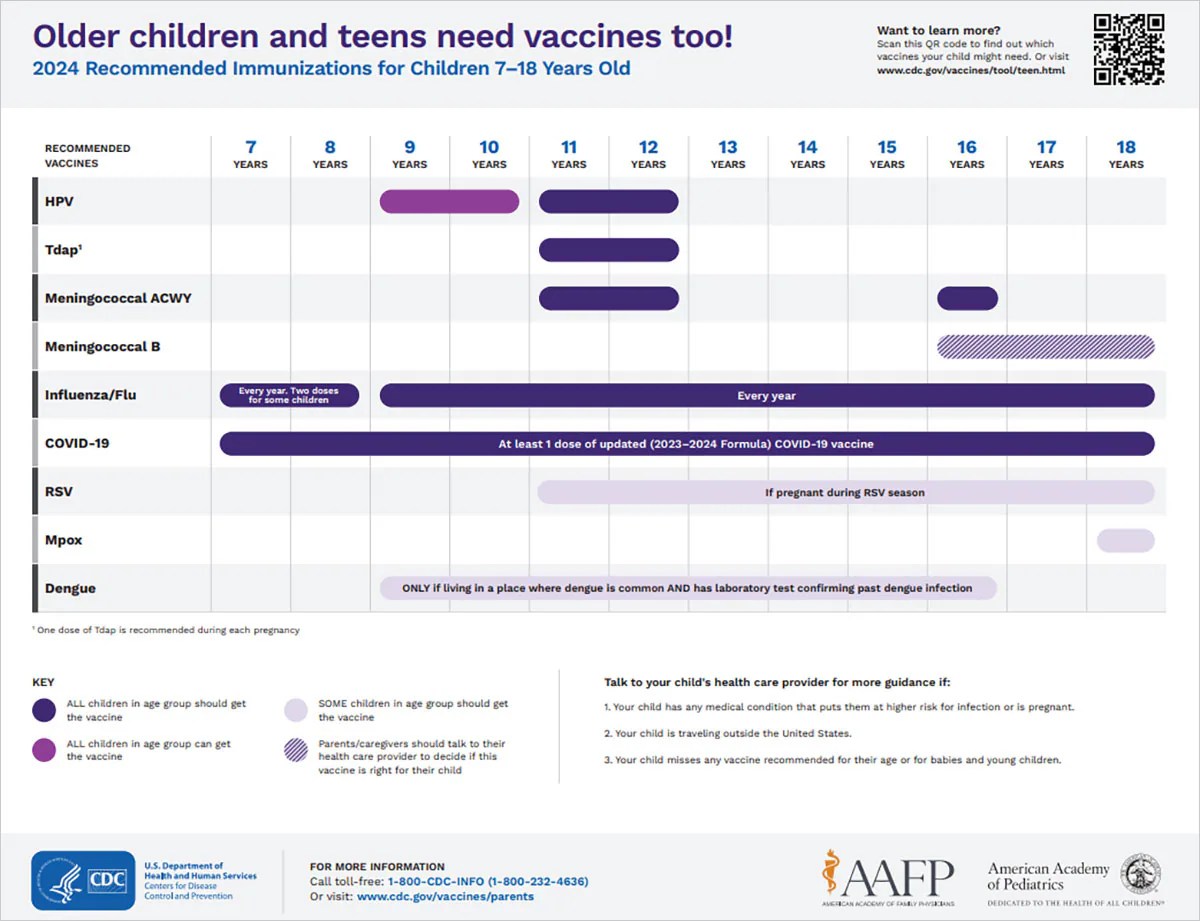

When should I get vaccinated (or have my child vaccinated)?

Vaccines protect us throughout our lives and at all ages - from birth, through childhood, through adolescence and into old age. In most countries, people are given vaccination cards that show which vaccinations an adult or child has received and when the next vaccinations are due. It is important that all indicated vaccinations are up to date.

It is important that all indicated vaccinations are up to date.

By delaying vaccination, we put ourselves at risk of becoming seriously ill. If we wait until the moment when a vaccine is urgently needed - for example, if an outbreak of a disease has begun - then it may be too late to get the desired effect of vaccination or all the necessary doses of the vaccine. nine0149

Why do I need to be vaccinated?

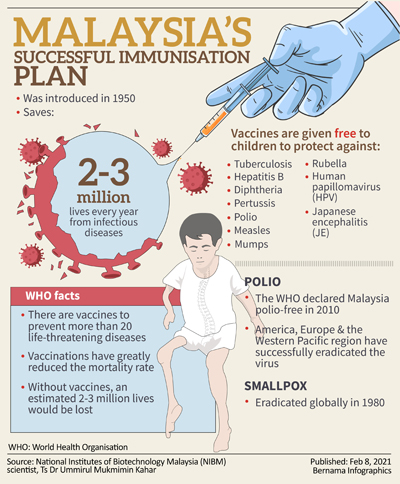

Without vaccination, we are at risk of serious diseases such as measles, meningitis, pneumonia, tetanus and polio. Many of these diseases are life threatening. The WHO estimates that childhood vaccines alone save more than 4 million lives each year.

Although some diseases are becoming less common, their pathogens continue to circulate in some or all regions of the world. In today's world, infectious diseases can easily cross borders and infect anyone who lacks immunity to them. nine0285

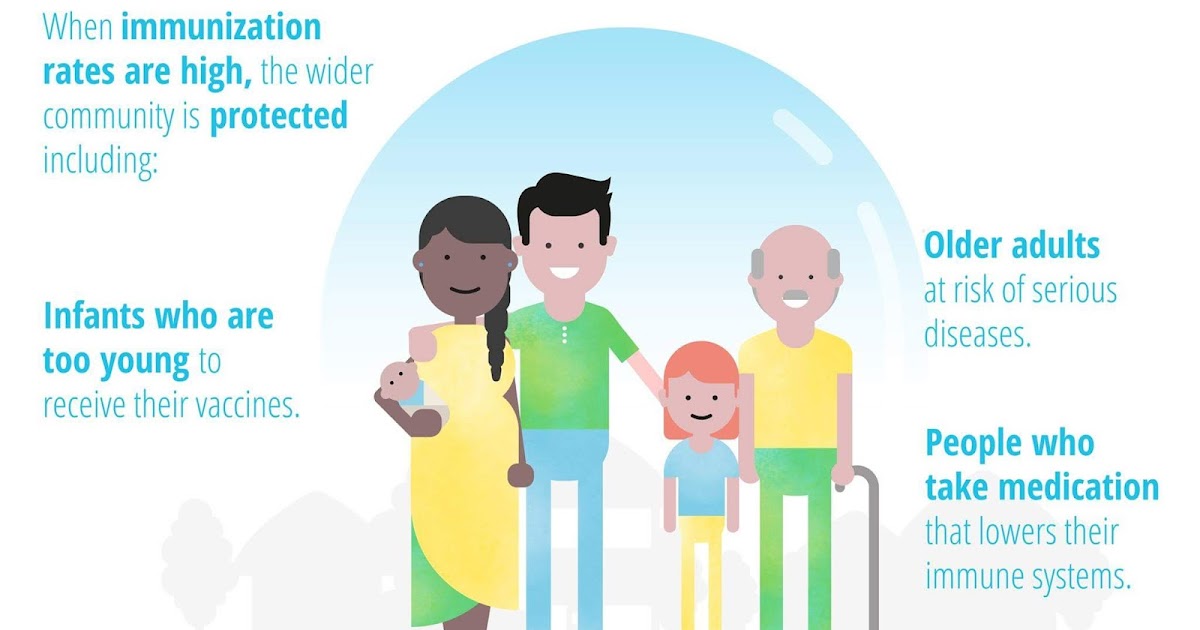

There are two main reasons to get vaccinated: to protect yourself and to protect others. Since some people, such as newborns and people with serious illnesses or those with certain allergies, may not be vaccinated, their protection against vaccine-preventable diseases depends on the availability of vaccinations in others.

Since some people, such as newborns and people with serious illnesses or those with certain allergies, may not be vaccinated, their protection against vaccine-preventable diseases depends on the availability of vaccinations in others.

Who should not be vaccinated?

Almost anyone can get vaccinated. However, for people with certain diseases and conditions, some vaccinations are contraindicated or should be deferred to a later date. These diseases and conditions may include:

- chronic diseases or treatments (eg chemotherapy) that suppress the immune system;

- extremely rare acute and life-threatening allergic reactions to vaccine components;

- severe illness at the time of vaccination. However, these children should be vaccinated as soon as they recover. Moderate malaise or subfebrile temperature is not a contraindication for vaccination.

Often these factors need to be taken into account depending on the type of vaccine. If you are not sure whether you or your child should get a particular vaccine, ask your doctor. Your doctor will help you make an informed decision about your or your child's vaccinations. nine0285

Your doctor will help you make an informed decision about your or your child's vaccinations. nine0285

What diseases do vaccines protect against?

vaccines protect against a number of diseases, including the following:

- Cervical Cancer

- Cholera

- Covid-1

- Hepatitis B 9000

- Pertussis

- Pneumonia

- Poliomyelitis

- Rabies

- Rotavirus

- Rubella

- Tetanus

- Typhoid fever

- Varicella

- Yellow fever

A number of vaccines for some other diseases, including Ebola or malaria, are currently under development or experimental use, but these vaccines have not yet been introduced in mass use throughout the world.

Not all vaccinations may be required in your country. Vaccinations against certain diseases may only be required for people who travel to certain countries or who are at increased risk due to their professional activities. Ask your doctor what vaccinations you and your family members need. nine0285

Ask your doctor what vaccinations you and your family members need. nine0285

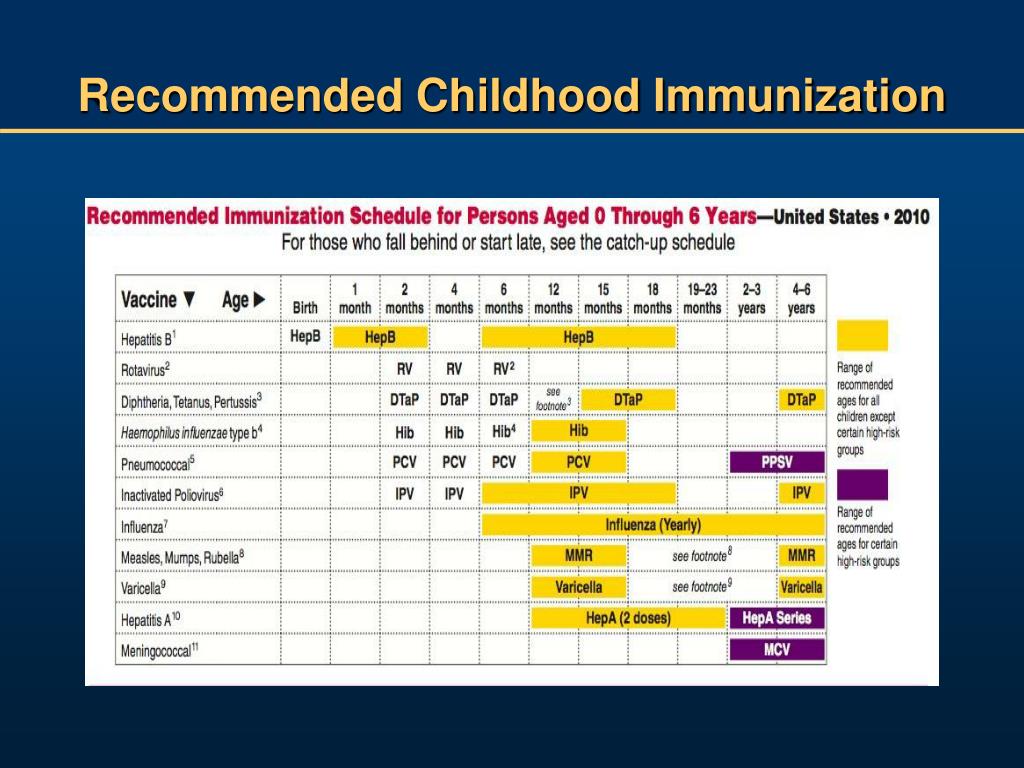

Why are vaccinations started at such an early age?

In their daily lives, young children may be in many different places and come into contact with a wide variety of people, thereby being at serious risk of infection. The WHO-recommended immunization schedule allows infants and young children to be protected as early as possible against a range of diseases. Often, infants and young children are most at risk of illness because their immune systems are not yet fully developed and their bodies are less able to fight off infections. Therefore, it is extremely important to vaccinate children according to the recommended schedule. nine0149

What is included in the vaccine?

All of the components that make up a vaccine play an important role in its safety and effectiveness. The composition of vaccines, in particular, includes the following components:

- Antigen. This is a killed or weakened form of any microorganism - a virus or a bacterium - on which our body learns to recognize and destroy the causative agent of the disease if it encounters it in the future.

- Adjuvants that help enhance the body's immune response. Without them, vaccines would be less effective. nine0005

- Preservatives to keep vaccines effective.

- Stabilizers to preserve the vaccine during storage and transport.

The names of vaccine ingredients written on vaccine packages can be confusing. However, many of them are naturally present in the body, environment and food. All of the components of vaccines, like the vaccines themselves, are subject to rigorous testing and monitoring for their safety.

Are vaccines safe?

Vaccination is safe and usually causes minor and temporary side effects, such as arm pain or mild fever. More serious side effects are possible, but they are extremely rare.

Any licensed vaccine is rigorously tested through several phases of clinical trials before it is approved for use and regularly evaluated after introduction. Scientists are also constantly monitoring information from a range of sources for signs that a given vaccine may pose a health risk. nine0285

nine0285

It must be remembered that the risk of serious harm to health from a vaccine-preventable disease is much greater than the risk associated with vaccination. For example, tetanus can cause severe pain, convulsions and thrombosis, and measles can lead to encephalitis (infection of the brain) and blindness. Many vaccine-preventable diseases can even be fatal. The benefits of vaccination far outweigh the risks, and without vaccines, the world would experience an order of magnitude more illness and death. nine0149

My child did not receive the recommended vaccinations on time. Is it too late to get the missing vaccinations?

In most cases, it is never too late to get the missing shots. Ask your doctor how and when you or your child can get the missing shots.

Do vaccines have side effects?

Like all medicines, vaccines can cause mild side effects such as low grade fever and pain or redness at the injection site. These symptoms usually go away on their own within a few days. nine0149

nine0149

Severe or long-term side effects are extremely rare. The chance of experiencing a serious adverse body reaction to a vaccine is 1 in a million.

The safety of vaccines is subject to ongoing monitoring and is continuously monitored for rare adverse reactions.

How are vaccines developed and tested?

The most commonly used vaccines have been in use for decades, and every year millions of people receive them safely. Like all medicines, every vaccine must undergo extensive, rigorous testing to assess its safety before it can be introduced in countries. nine0285

Experimental vaccines are first tested in animals to evaluate their safety and ability to prevent disease. They are then tested in human clinical trials, which consist of three phases.

• During the first phase of the trial, the vaccine is given to a small number of volunteers to evaluate its safety, make sure it generates an immune response, and determine the correct dose.

• During the second phase of the trial, the vaccine is typically administered to hundreds of volunteers who are closely monitored for any side effects and further evaluation of its ability to generate an immune response. Data on disease outcomes are also collected at this stage whenever possible, but these data are usually not sufficient to provide a clear picture of the impact of the vaccine on the disease. Participants in this phase of the trial share the same characteristics (such as age and gender) as the people for whom the vaccine is intended. At this stage, some volunteers receive the vaccine and others do not, allowing comparisons to be made and conclusions about the vaccine to be made. nine0149

• During the third phase of the trial, the vaccine is administered to thousands of volunteers, some of whom receive the study vaccine and some do not, as in the second phase of the trial. The data from both groups are carefully compared to determine whether the vaccine is safe and effective in protecting against the disease it is intended to target.

Following clinical trial results, a number of steps must be taken before a vaccine can be included in a national immunization program, including efficacy, safety, and manufacturing reviews for regulatory approval and public health policy approval. nine0285

After the introduction of the vaccine, careful monitoring continues to be carried out to identify any unexpected unwanted side effects and further evaluate its effectiveness in the context of regular use in even more people, which will allow understanding how to best use the vaccine to ensure the greatest protective effect. For more information on vaccine development and safety, click here.

Can a child have more than one vaccine at a time? nine0285

Scientific evidence shows that the simultaneous administration of several vaccines does not have negative consequences. Every day, children are exposed to several hundred foreign substances that trigger the body's immune response. A simple meal is accompanied by the entry of new microorganisms into the body, and many bacteria live in the nose and mouth.

The ability to combine multiple vaccines (eg diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus) reduces the number of injections and reduces discomfort for the child. In addition, it allows you to know for sure that the child received the right vaccinations at the right time and will not catch a potentially fatal disease. nine0285

Is there a link between vaccination and autism?

There is no evidence of any association between vaccination and autism spectrum disorders. This conclusion was drawn from the results of many studies conducted on very large groups of people.

In 1998, a study was published raising concerns about a possible link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism, but the study later found a number of serious misrepresentations and falsified information. The journal that published this work later withdrew it, and the doctor who wrote it lost his license to practice medicine. Unfortunately, due to fears caused by this publication, vaccination rates in some countries dropped sharply, which subsequently led to outbreaks of these diseases. nine0285

nine0285

We all have a responsibility to take the necessary steps to disseminate only reliable, science-based information about vaccines and the diseases that vaccines help prevent.

Does my daughter need to be vaccinated against the human papillomavirus (HPV)?

Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by sexually transmitted HPV infection. Vaccination against HPV before a person comes into contact with this virus is the most effective means of protection against this disease. Studies in Australia, Belgium, Sweden, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Sweden showed that vaccination reduced the number of HPV infections among adolescent girls and young women to almost 90%.

Studies have proven the safety and efficacy of the HPV vaccine. WHO recommends that all girls aged 9–14 years be vaccinated with two doses of the HPV vaccine, and that women be periodically screened for cervical cancer later in life.

I have questions about vaccinations. Who should I contact?

Who should I contact?

If you have any questions about vaccinations, be sure to ask your doctor. He or she will be able to give you evidence-based information about vaccinations, including the recommended vaccination schedule in your country for you and your family members. nine0285

When looking for information about vaccines on the Internet, look only to trusted sources. To help you find these sources, WHO has reviewed and "certified" many websites in many languages around the world to contain only information based on sound scientific evidence and independent analysis by leading technical experts. All of these websites are part of the Vaccine Safety Net (www.vaccinesafetynet.org). nine0285

How does WHO contribute to vaccine safety?

WHO works to ensure that all people around the world are protected with safe and effective vaccines. To this end, we help countries build strong vaccine safety systems and apply strict international standards for vaccine regulation.

Together with scientists from around the world, WHO experts continuously monitor to ensure that vaccines are safe. We are also working with partners to assist countries in investigating and reporting potential problems. nine0149

Any unexpected side effects reported to WHO are evaluated by an independent panel of experts called the Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety.

Coronavirus vaccine did not help. Why is this possible? – DW – 10/18/2021

COVID-19 vaccination Photo: Wytrazek/Zoonar/picture alliance

SocietyGermany

Astrid Prange | Natalya Pozdnyakova

October 18, 2021

Some people have contracted the coronavirus despite being fully vaccinated. How did this happen and why did the vaccine not protect them from covid? DW has collected the facts on which the Germans rely.

https://p.dw.com/p/41kIK

Advertising

Infection with coronavirus and the manifestation of all symptoms of the disease, despite full immunization, that is, two vaccinations, are among those rare cases when the vaccine was ineffective. But are they evidence that it is not necessary to be vaccinated, because it will not help anyway? nine0285

But are they evidence that it is not necessary to be vaccinated, because it will not help anyway? nine0285

No. The statements often found in social networks that a vaccine that did not protect against infection is proof of the weak effect of vaccines are incorrect. It is only true that none of the coronavirus vaccines available to humanity provides 100% protection.

How effective are vaccines?

According to the German Robert Koch Institute (RKI), the average effectiveness of vaccines approved for use in Germany for people aged 18-59 has reached 83 percent in the past nine months. For people over the age of 60, about 82 percent. Protection against a severe course of the disease when using the vaccine was 9 for these age groups, respectively.5% and 93%.

Immunologist Kristine Falk Photo: Anja Frick/DGfI The time factor influences the protection against coronavirus obtained as a result of vaccination. "So far, there is not a single person who was vaccinated earlier than a year ago. Therefore, we cannot say exactly how long the vaccine lasts," Christine Falk, president of the German Society for Immunology, explains in an interview with DW. But what is known now for sure: the number of antibodies decreases 6-9 months after vaccination. "It wouldn't bother me if we didn't have the delta variant, which is more contagious than all previous coronavirus mutations," says Falk. nine0285

Therefore, we cannot say exactly how long the vaccine lasts," Christine Falk, president of the German Society for Immunology, explains in an interview with DW. But what is known now for sure: the number of antibodies decreases 6-9 months after vaccination. "It wouldn't bother me if we didn't have the delta variant, which is more contagious than all previous coronavirus mutations," says Falk. nine0285

In what cases can a vaccination fail?

"If the immune defense formed as a result of vaccination cannot resist spike antigens with the help of antibodies, the virus is able to overcome this defense, gain a foothold in the cell and cause an infection in the nasopharynx," says an immunologist from the Institute of Transplant Immunology at the Hannover Medical School. There is a case where the vaccine did not work."

According to the RKI report, only 0.56 percent of patients out of 67,661 (number recorded between February 1 and October 1, 2021) who did not respond to vaccinations experienced severe disease. The number of deaths among patients who were not helped by the vaccine against COVID-19, is 1.06 percent. For comparison: during the first wave of coronavirus in Germany, when there were no vaccinations yet, the RKI estimated the fatality rate - that is, the number of deaths from covid - at almost 6.2 percent.

The number of deaths among patients who were not helped by the vaccine against COVID-19, is 1.06 percent. For comparison: during the first wave of coronavirus in Germany, when there were no vaccinations yet, the RKI estimated the fatality rate - that is, the number of deaths from covid - at almost 6.2 percent.

In addition, the RKI report states: "Among the 722 deaths of patients who, despite being vaccinated against coronavirus, fell ill with covid and died, 75 percent were over 80 years of age. This reflects the risk of high mortality from this disease - regardless of the effectiveness of the vaccine among the indicated age group". nine0285

Has the number of ineffective vaccinations increased?

Yes. According to the RKI, in late September - early October of this year, among people aged 18 to 59 years, 8224 cases were registered when the vaccine did not help. This figure has increased by 7.2 percent - if you look at the entire period of time since the start of the vaccination campaign in Germany. The number of vaccinated patients in this age group, who have a severe disease, is 2.2 percent since the beginning of the year.

The number of vaccinated patients in this age group, who have a severe disease, is 2.2 percent since the beginning of the year.

The over 60 age group is also on the rise. The number of ineffective vaccinations among patients with covid symptoms since the start of the vaccination campaign is about 10.1 percent. Over the past four weeks, this is 7015 cases. The number of patients over 60 years old who ended up in the intensive care unit despite being vaccinated is about 6 percent since the beginning of the year.

According to the RKI, this development was expected as more people get vaccinated, but the virus continues to spread. nine0285

Are the unvaccinated responsible for vaccine failure?

No. But their behavior greatly affects the spread of the coronavirus, the pandemic, and the strain on national health systems.

"The increase in hospital admissions, according to the RKI's weekly reports, is almost exclusively among unvaccinated patients over 60," says immunologist Kristine Falk.

If the number of infections increases in autumn, the unvaccinated will be the first to be at risk. But those who have been vaccinated can also easily become infected, Falk warns, because the virus has not gone anywhere, it has become even more.

However, immune protection is not the same for all people. And if, after a certain time after vaccination, immunity gradually weakens, there are several reasons for this. Among the important factors are age, the presence of chronic diseases, the intervals between vaccinations and the vaccine itself. Especially often old people and cancer patients face this. nine0285

This is why the Permanent Commission on Vaccination (Stiko) recommended on 7 October that people over 70 years of age get a third vaccination. Additional vaccinations will also be offered to staff in hospitals and nursing homes. More than a million people in Israel have already received their third dose of the coronavirus vaccine.

How can the interval between vaccinations affect the effectiveness of vaccination?

Most Israelis are vaccinated with the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine, with an interval of 21 days between the first and second shots.