Therapy for abortion

When post-abortion emotions need unpacking

Catherine Beckett, an American Counseling Association member with a private practice in Portland, Oregon, has made it a habit to avoid using “must” phrases with clients. “It sends a message to the client about what they’ve experienced,” says Beckett, who specializes in grief counseling. “I don’t ever want to say, ‘Oh, you must feel so guilty,’ or ‘You must feel so isolated,’ because that may not be the case at all.”

A case in point: when clients reveal in counseling that they have had an abortion at some point in their past. Some clients consider that experience to be just another piece of their life story, free of any negative associations. For others, the experience can evoke a range of issues, from spiritual and familial turmoil to attachment difficulties and feelings of loss. When dealing with such a highly charged topic, counselors must be prepared to put their own personal views aside to support clients who fall into either camp — and those who present a range of emotions in between.

Research cited by an American Psychological Association task force found that the majority of women who elect to have an abortion will not experience mental health difficulties afterward (see apa.org/pi/women/programs/abortion/). In February 2017, JAMA Psychiatry published a study titled “Women’s mental health and well-being 5 years after receiving or being denied an abortion.” The study observed 956 women over the course of five years, including 231 who initially were turned away from abortion facilities. Among the authors’ conclusions: “In this study, compared with having an abortion, being denied an abortion may be associated with greater risk of initially experiencing adverse psychological outcomes. Psychological well-being improved over time so that both groups of women eventually converged. These findings do not support policies that restrict women’s access to abortion on the basis that abortion harms women’s mental health.”

Even though most women will not experience long-term mental health problems after an abortion, some may still endure feelings of loss or encounter other negative emotions caused by external factors such as culture or family. For certain clients, a past abortion experience, whether it took place one month ago or decades ago, can be at the root of a range of issues — low self-esteem, relationship problems, disenfranchised grief — that surface during counseling sessions.

For certain clients, a past abortion experience, whether it took place one month ago or decades ago, can be at the root of a range of issues — low self-esteem, relationship problems, disenfranchised grief — that surface during counseling sessions.

Beckett notes that most of the women she works with aren’t questioning their decision to have an abortion but rather “struggling to process it and place it in the narrative of their own lives in a way that feels comfortable.”

“As a practitioner, you should know about [abortion] and understand that within the population you’re seeing, it’s probably in their story,” says Jennie Brightup, a licensed clinical marriage and family therapist in private practice outside of Wichita, Kansas. “You need to be prepared to know how to work with it.”

Counselors should approach the revelation of an abortion just like any other experience or issue that clients may have in their histories, Brightup says. “Have an open mind. Allow it to be something that can be a problem for your client. See that it could be an issue … [and] have some knowledge about how to treat it.”

See that it could be an issue … [and] have some knowledge about how to treat it.”

‘You think you’re alone’

The Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive health research organization, estimates that in 2014 (the most recent data available), 926,200 abortions were performed among women between the ages of 15 and 44 in the United States. This comes out to a rate of 14.6 abortions per 1,000 women.

The institute notes that this marks America’s lowest abortion rate since the process was legalized nationwide by the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973. The U.S. abortion rate has seen a steady decline after peaking in 1980 and 1981 at close to 30 abortions per 1,000 women. Using the 2014 data, the Guttmacher Institute extrapolates that 5 percent of U.S. women will have an abortion by age 20; 19 percent will have an abortion by age 30; and 24 percent will have an abortion by age 45.

Abortion is more common than many people, including mental health practitioners, think, says Trudy Johnson, a licensed marriage and family therapist who presented on “Choice Processing and Resolution: Bringing Abortion After-Care Into the 21st Century” at ACA’s 2012 Conference & Expo in San Francisco. Johnson, who had an abortion in college, says that for many people, processing the abortion experience is “a slow burn. It doesn’t affect you until later on. [Many] women have had an abortion, but you think you’re alone. You don’t feel you get to grieve it. … It’s a gut-level thing, a tender place. Many have never told a soul,” says Johnson, who specializes in trauma resolution, including abortion-related issues.

Johnson, who had an abortion in college, says that for many people, processing the abortion experience is “a slow burn. It doesn’t affect you until later on. [Many] women have had an abortion, but you think you’re alone. You don’t feel you get to grieve it. … It’s a gut-level thing, a tender place. Many have never told a soul,” says Johnson, who specializes in trauma resolution, including abortion-related issues.

Connecting issues

For clients who have yet to process and place a past abortion into their self-narrative, it can feel like a sadness that they can’t quite pinpoint or define. “It’s kind of like a phantom pain. It’s there, but you don’t know why,” Johnson says.

Clients with a variety of presenting issues may have unprocessed emotions surrounding a past abortion that could be compounding their struggles, Johnson says. These issues can include:

- Depression and anxiety

- Complicated grief

- Anger

- Shame and guilt (especially shame that is undefined or has no apparent cause)

- Self-loathing and self-esteem issues

- Relationship issues (including destructive relationships)

- Destructive behaviors (including substance abuse)

For certain clients, their unprocessed emotions can feel like a weight they have carried and buried deep within themselves for a long time without sharing it with anyone, Johnson says.

Johnson recalls one client who initially came for couples counseling with her husband but eventually started seeing Johnson for individual counseling. During a session, Johnson recognized that the woman was becoming upset, so she handed her a blanket and pillow for comfort. The client put the blanket over her head, obscuring her face, and disclosed that she had had an abortion 18 years prior. Her family had shamed her for the decision, and her feelings of shame were still so overwhelming that putting the blanket over her head was the only way she could bring herself to talk about the experience, Johnson recounts.

“You just can’t imagine the shame that [some of] these clients carry,” says Johnson, a private practitioner who splits her time between Arizona and Tennessee. “They just have to talk about it. We, as professionals, can be that safe place.”

Clients who have had abortions sometimes question whether they have the right to grieve because there was a choice involved to terminate their pregnancies, says Beckett, who is an adjunct faculty member in the doctoral counseling program at Oregon State University. The concept of the experience of disenfranchised grief — those who are not supported in their grief because it is not culturally recognized or validated — applies in these instances, Beckett says. In fact, the disenfranchisement can be both external (a loss not recognized by the client’s culture) and internal (a loss that the client, individually, does not recognize).

The concept of the experience of disenfranchised grief — those who are not supported in their grief because it is not culturally recognized or validated — applies in these instances, Beckett says. In fact, the disenfranchisement can be both external (a loss not recognized by the client’s culture) and internal (a loss that the client, individually, does not recognize).

“People do not have the same kind of support and validation [to grieve a loss] when they’re disenfranchised, and that is a huge part of abortion grief,” Beckett says. “The emotional aftermath is so impacted by spiritual, political and ethical values and beliefs. That will really color how they process it and how much they’re able to reach out and get support. This all needs to go into our assessment of a client. What was their experience, but also how are they talking to themselves about it? All of that should inform how we offer support.”

Broaching the subject

Practitioners might want to consider asking clients (female and male) about pregnancy loss, including abortion, on intake forms. Brightup asks clients about past pregnancy loss in a genogram exercise she does in the first few sessions of counseling. If the client mentions an abortion, she simply makes a note and keeps going. It is not a topic she feels a need to jump on immediately, she says, and she doesn’t want to risk retraumatizing clients or prompting them to talk about it if they are not ready. Some clients may not mention an abortion on an intake form or genogram because they don’t consider it a loss or associate it with trauma, Brightup says. Others have buried the issue so deep that they don’t think about it or feel that it is worth mentioning, she adds.

Brightup asks clients about past pregnancy loss in a genogram exercise she does in the first few sessions of counseling. If the client mentions an abortion, she simply makes a note and keeps going. It is not a topic she feels a need to jump on immediately, she says, and she doesn’t want to risk retraumatizing clients or prompting them to talk about it if they are not ready. Some clients may not mention an abortion on an intake form or genogram because they don’t consider it a loss or associate it with trauma, Brightup says. Others have buried the issue so deep that they don’t think about it or feel that it is worth mentioning, she adds.

“When you’re hearing their story, you can find places to check in and ask questions. Most of the time, I allow them to come around and tell me. It’s a core secret. If you feel [judgmental] to them, they’ll never tell you and they’ll run [stop coming to therapy],” says Brightup, a certified eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapist.

Practitioner language is also important, Beckett notes. “For some people, asking [if they have an abortion in their past] is giving them permission to talk about it. And the way we ask about it may give them clues about whether or not it is safe to talk to us about it,” she says. “For example, there’s a difference between, ‘Is this something you have experience with?’ and ‘Well, you haven’t had an abortion, have you?’”

Even the word “abortion” can provoke an intense reaction for some clients, Johnson says. In some cases, she will use the phrase “pregnancy termination” or even “the A word” with clients who feel triggered and begin to close themselves off.

“You might need to say it differently,” Johnson advises. “Abortion immediately turns it into a political, socially charged [issue]. Changing the terminology helps it to be safer.”

The key is to foster a safe, trusted bond so that clients will feel free to bring the topic up themselves when they are ready, Johnson says. “The most important thing is building a relationship of safety,” she emphasizes.

“The most important thing is building a relationship of safety,” she emphasizes.

Different points on a path

Clients who disclose having an abortion in their past may vary widely on how they feel about the procedure and how much they have processed those feelings.

“There are clients who will come in and do not report having any mental health issues related to their abortion experience. Understand that they’re out there. But the other side is out there too,” Brightup says. Practitioners must be prepared to work with clients who express either sentiment — or a range of feelings in between.

Counselors should watch their clients’ body language and other cues, especially in cases in which a client is emphatic or even defensive when talking about an abortion. It is wise to unpack the client’s experience and associated feelings over time, Brightup says.

If counselors disagree with a client’s assertions concerning how she feels about the procedure, “you can lose the client because they won’t come back [to therapy],” she says. “Agree with their narrative. In little pieces, once they trust you, you can come back to the story and probe a little, ask a few questions as gently and carefully as you can.”

“Agree with their narrative. In little pieces, once they trust you, you can come back to the story and probe a little, ask a few questions as gently and carefully as you can.”

Some clients will have fit the abortion into their self-narrative and moved on, whereas others won’t be as far along in the journey. Still others will have worked through their feelings surrounding the procedure in a healthy way previously but may find themselves struggling with it again as they move into another life stage such as pregnancy or motherhood, Beckett says.

This was the case for one of Beckett’s clients who sought counseling because she was struggling with powerful emotions that had resurfaced. The client had undergone an abortion when she was 17. Later in her life, she had a daughter, and that daughter was now turning 17 herself. Even though her daughter wasn’t facing any type of decision regarding pregnancy or abortion, her age triggered feelings in the client that needed more therapeutic attention.

The client’s abortion had been illegal at the time where she lived, so she had felt compelled to keep it a secret, Beckett explains. The client realized her daughter was now the age she had been when she had an abortion. “The mother saw, for the first time, how young she [had been] and how desperately she had needed love and support at the time, and she didn’t get it,” Beckett says. The realization was “exquisitely painful” for the client, but at the same time, it brought “a new level of compassion for her 17-year-old self,” Beckett recounts.

“She took a great deal of comfort in knowing that if her daughter were to get pregnant, it would be an entirely different experience. Her daughter would have the support of her family and better care,” Beckett says.

The hard work of unpacking

Just as clients will differ in the work they have done — or haven’t done — to process the emotions surrounding an abortion, the support and interventions they might need from a counselor will also vary.

“People grieve very differently, and we need to be ready to support people however they are doing it,” Beckett says. “Some people are going to want to take action or give back somehow. Others will respond to more creative processes or ritual creation. Others will want a quiet, safe place to process.”

Normalizing a client’s experience can be a much-needed first step. Beckett says that talking about how common abortion is, and the fact that many people feel a need to process their feelings afterward, can bring relief to clients. Practitioners can also help clients reframe their thoughts to realize that feelings of relief after the procedure are common, as is a fear of judgment and a sense of isolation that can accompany that fear.

“Figure out what this particular client’s experience is and then, if appropriate, offer normalization of that,” Beckett says. “Support them to determine what is needed to move them toward greater comfort and peace. Offer them ideas and support around getting those things that they need. ”

In Brightup’s experience, post-abortion work with clients often falls into four quadrants:

- Reconciling how clients feel about themselves

- Engaging in grief work around how clients perceive and feel about the loss (if they do indeed view it as a loss)

- Working through clients’ spiritual issues or any inner tensions related to “rules” that were broken

- Working on clients’ relationships and how they relate to people: Are there areas that need healing?

From there, practitioners should tailor their approaches to meet each client’s individual needs and pacing, Brightup says. She often uses sand tray therapy as a tool to help clients talk about post-abortion loss and find closure. Journaling, writing letters or poems, creating art and engaging in other creative outlets can also be helpful, she says. Certain clients may respond to creating some kind of physical memorial or taking time out of a counseling session to do a remembrance with just the two of you, Brightup adds.

Beckett agrees that counselors should collaborate with clients to find a ritual or activity that works for them. Although many clients will make progress through talk therapy or by connecting in group work to those who have had similar experiences, others will feel a need to take some kind of action, Beckett says. Creating memorials and rituals, writing letters or participating in other creative interventions can help these clients to process their emotions and experiences.

For one of Beckett’s clients, healing involved creating a special ritual on what would have been her child’s due date. Each year, the client would be intentional about spending time with a child — whether a niece or a nephew or the child of a friend — who was the same age that her child would have been.

“She came in pretty soon after her abortion, and she knew she needed help to process it,” Beckett says. “She wasn’t questioning the decision, but she was having trouble [with the fact] that her life would move forward but the life of the baby she had not had wouldn’t move forward. She wrote a letter to that baby expressing her caring and regret and explaining why she felt she couldn’t bring him or her into the world. Every year on her due date, she would find a way to connect with a child she knew that would be that age. She would spend time with that child and make it a good day for them.”

Whereas this intervention helped this particular client to find peace, “for other clients, the thought of that would seem hellish,” Beckett stresses. “There’s no prescription for this. It’s a process of figuring out what is still remaining and needs to be released. Talk with the

client to find creative ways to be able to do that.”

Counselors can help clients navigate areas in which they feel emotionally stuck, Beckett explains. For example, one of her clients was struggling even though she had worked through many of the emotions she had experienced after an abortion. The client had three children, and when she became pregnant with a fourth, she and her partner made the decision to terminate the pregnancy.

“There was one part that she couldn’t get OK with: ‘I see myself as someone who takes care of others,’” Beckett says. “That’s where we focused: How did she define ‘taking care’? How did this decision threaten her self-concept? We dove into that area and she eventually realized that terminating the pregnancy was taking care of her fourth child. That was the best way to take care of that child, instead of bringing the child into an already-overwhelmed system that wouldn’t have been able to provide what the child needed.”

Johnson finds narrative therapy a useful approach when focusing on post-abortion issues with clients. Giving them the freedom to tell the story of their abortion — how old they were, how it happened, who came with them that day — can be powerful, she says. Sometimes clients won’t remember the details about their abortion because they’ve blocked them out, Johnson says, but as they open up and talk about the experience in therapy, they often start to recall things.

“This has been in their head for years. When they finally start talking about it, they go on and on because that’s [often] what they need,” Johnson says. “You can see the layers coming off as they’re processing it verbally, the whole story. … Letting them talk about the details and tell their story is a starting point.”

When relevant, Johnson also helps clients identify all the points of grief connected to the abortion beyond the loss of a pregnancy. For example, clients might have experienced a breakup with their romantic partners or the breakdown of a relationship with their parents or other family members either leading up to or after the abortion. Giving clients permission to grieve and accept the loss of these things is an important step, Johnson says.

There are “so many layers to this. The main thing [for counselors] is being a safe place. The impact of a hidden abortion could really be affecting the outcome of your therapy if it’s not addressed. Be aware that there could be this issue under all of the other stuff [the presenting issues],” Johnson says.

“Treat this as a disenfranchised and complicated grief situation, and take out all the political mess and pros and cons,” she continues. “The client has already made a choice. Let’s forget about that and just work on the grief. They’re not the same person that they were when they made the choice. They’re a different person now, so they need to have permission to revisit that time in their life and be free of it. The therapist is kind of a vessel of freedom for that, and it’s a wonderful place. … You’re helping them overcome the bondage, pain and grief that’s been with them for so long.”

Putting personal feelings aside

Abortion remains one of the most politically and socially polarizing issues in modern-day America. Despite this — or, in some cases, because of this — certain clients are going to need to work through issues related to abortion in the counseling office. A practitioner’s role is to be a support through it all, regardless of his or her own personal views on the topic.

Brightup urges counselors to rely on their training, which includes setting personal opinions aside and being what the client needs.

Creating a neutral and welcoming space for clients to talk about such a sensitive topic is paramount, Johnson agrees. “If you don’t have any experience working in this area, you can do more damage without meaning to,” she says. “Or, for some people, there’s a hidden implication that if you help a client through feelings related to an abortion, you’re condoning abortion.” That is simply not true, she stresses.

Beckett agrees. “Clients need a safe and nonjudgmental space to share [about their abortion experience], and that’s hard for some counselors based on their own belief system. It’s not going to be easy for all counselors — that affirmation of [the client’s] right to grieve. [But] a client needs support to determine what is needed to move them toward greater comfort and peace. Offer them ideas and support around getting those things that they need. ”

****

Disclosing an innermost secret

As clients process post-abortion emotions, they may struggle with the decision to tell others, including a current or former partner. What should a counselor’s role be in that process? Read more in our online-exclusive article: wp.me/p2BxKN-54z

****

Related resources

- For more on the mandate for counselors to practice competent, nonjudgmental care, refer to the 2014 ACA Code of Ethics at counseling.org/knowledge-center/ethics/code-of-ethics-resources. ACA members with specific questions can schedule a free ethics consultation by calling 800-347-6647 ext. 321 or emailing [email protected].

- Interested in networking with other ACA members on this and other related issues? ACA has interest networks that focus on women’s issues, grief and bereavement, sexual wellness and other topics. Find out more at counseling.org/aca-community/aca-groups/interest-networks.

- The Professional Counselor journal article, summer 2019 (page 100, Volume 9/Issue 2): “Supporting Women Coping With Emotional Distress After Abortion“

****

Bethany Bray is a staff writer and social media coordinator for Counseling Today. Contact her at [email protected].

Letters to the editor: [email protected]

****

Opinions expressed and statements made in articles appearing on CT Online should not be assumed to represent the opinions of the editors or policies of the American Counseling Association.

Mandatory Counseling For Abortion | Guttmacher Institute

Evidence You Can Use

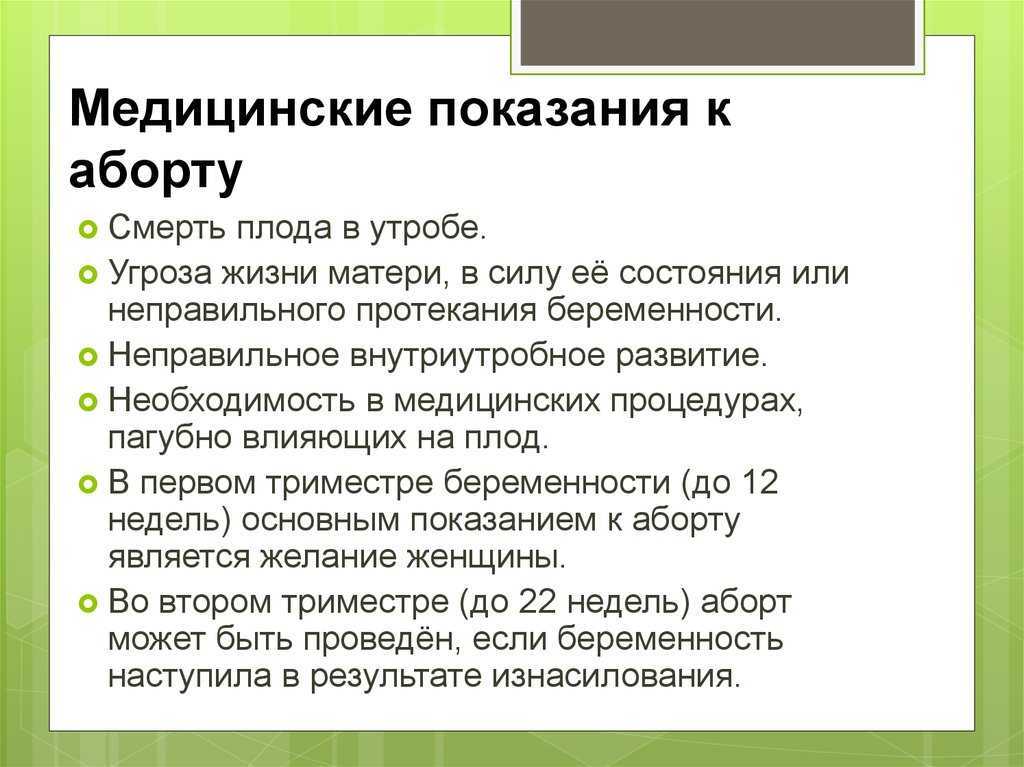

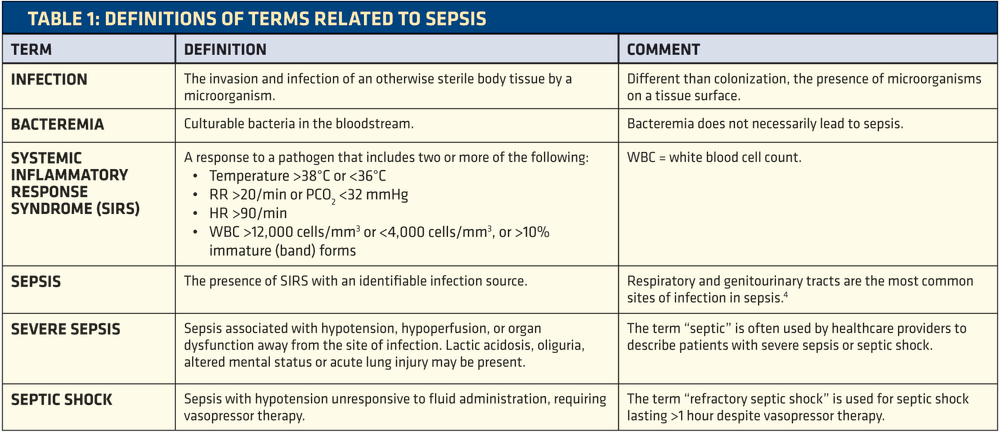

Background

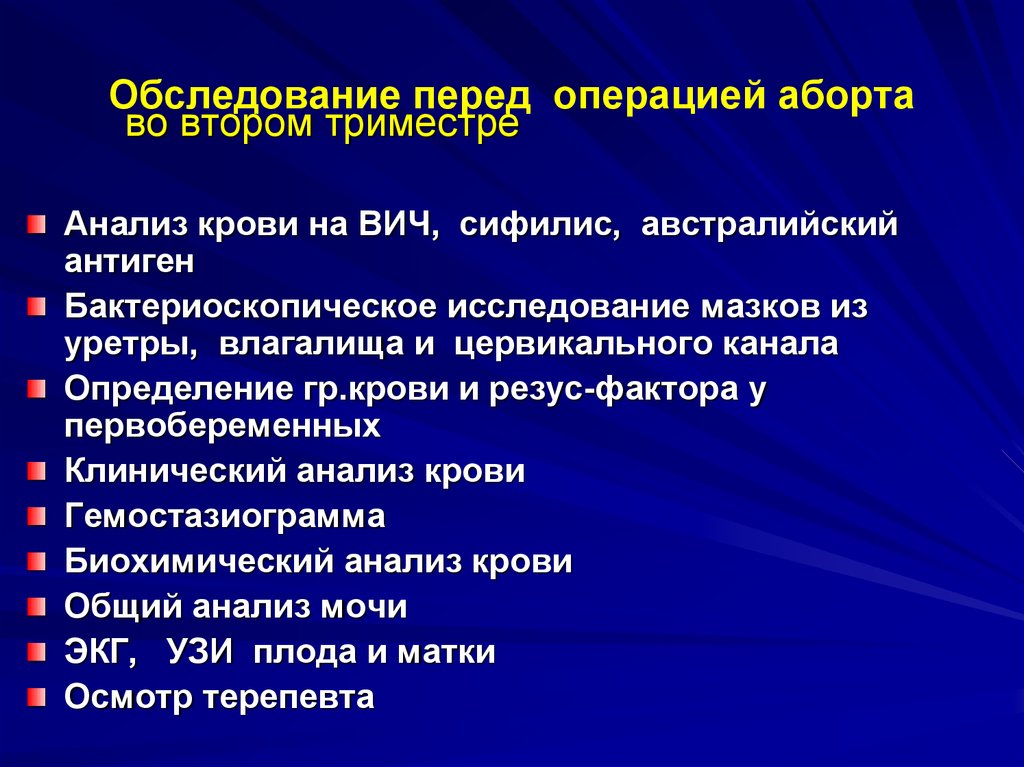

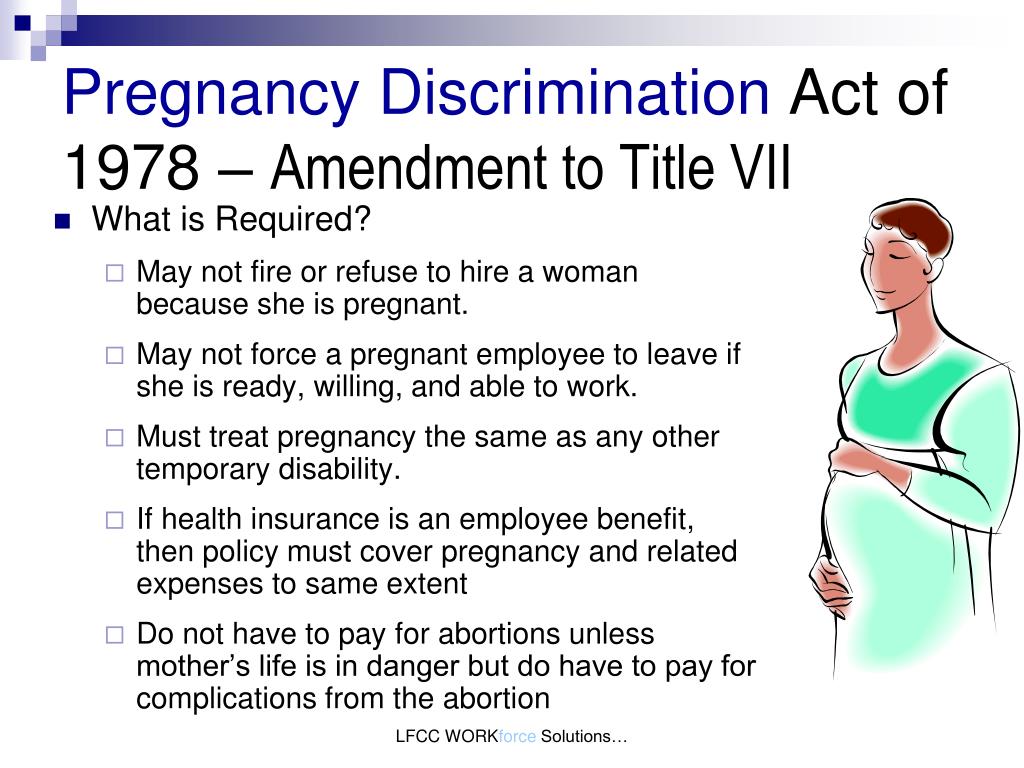

Abortion is a safe and legal medical procedure that does not require expanded counseling. Abortion providers—like all medical providers—are ethically bound to provide patients with information about options, procedure details and any other information a provider deems pertinent after assessing each patient’s unique health needs and circumstances. Providers are also required to obtain informed consent, which means they must verify that patients possess the capacity to make decisions about their care, that their participation in these decisions is voluntary, and that they receive adequate and appropriate information.

Providers are also required to obtain informed consent, which means they must verify that patients possess the capacity to make decisions about their care, that their participation in these decisions is voluntary, and that they receive adequate and appropriate information.

However, some states have specific abortion counseling provisions, and many of these laws require providers to give inaccurate or misleading information to women seeking abortion care in order to dissuade them from obtaining an abortion. These requirements violate the principles of informed consent, intrude on the provider-patient relationship, and infringe patients’ right to receive relevant, accurate and unbiased information prior to obtaining medical care so they can make sound decisions about their treatment.

State Laws and Policies

For a chart of current laws and policies in each state related to mandatory counseling for abortion, see Counseling and Waiting Periods for Abortion.

For information on state laws and policies related to other sexual and reproductive health and rights issues, see State Laws and Policies, issue-by-issue fact sheets updated monthly by the Guttmacher Institute’s policy analysts to reflect the most recent legislative, administrative and judicial actions.

Relevant Data and Analysis

Abortion Providers’ Adherence to Ethics for Consent

Abortion providers operate under medical principles of informed consent and are bound by the same code of medical ethics as doctors who do not perform abortions.

- The American Medical Association (AMA) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) affirm that providers have an ethical and legal duty to obtain voluntary and informed consent from patients.1,2 ACOG asserts that “seeking informed consent…respects a patient’s moral right to bodily integrity.”2

- According to ethical principles for abortion care developed by the National Abortion Federation, it is the role of any abortion provider to “ascertain before providing an abortion that the patient…has freely chosen to end her pregnancy, is prepared to do so and has not been coerced in any way.”3

Women’s Certainty About Abortion

Women who obtain an abortion are sure of their decision.

- A study of Wisconsin’s 2013 mandatory preabortion ultrasound law found that 93% of women were certain of their decision to obtain an abortion, both before and after the law was implemented.4

- In a nationally representative survey of abortion patients conducted in 2008, 92% of women reported they had made up their mind to have an abortion prior to making an appointment.5

- Ninety-nine percent of abortion patients in a 2008 clinic study reported that they were “sure” or “kind of sure” of their decision to have an abortion, and 98% reported that “abortion is a better choice for me at this time than having a baby.”6

- Standards of care dictate that a woman facing an unintended pregnancy should receive information about all of her options—prenatal care and delivery; infant care, foster care, or adoption; and pregnancy termination—in a nonjudgmental manner.3,7

Inaccurate Information on Mental Health

State-mandated counseling sometimes includes inaccurate information on the mental health consequences of having an abortion.

- Some states require abortion providers to tell women that an abortion may lead to a PTSD-like condition they call “postabortion stress syndrome.” The American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association do not recognize this condition, and there is no evidence it exists.8,9

- An expert panel convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in 2018 concluded that having an abortion does not increase a person’s risk of mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.10

- A 2014 study found that among women seeking an abortion in Utah, the proportion who falsely believed that abortion causes depression or anxiety increased from 24% to 34% after receiving inaccurate state-developed counseling on the mental health risk of an abortion.11

- Many studies have shown that abortion does not increase women’s risk of mental health problems.

12,13 Two reviews of the evidence by the American Psychological Association in 1989 and 2006 concluded that an abortion of an unintended pregnancy during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy “does not pose a psychological hazard for most women.” More specifically, the risk of mental health problems is no greater if a woman who has an unintended pregnancy has an elective first-trimester abortion than if she carries the pregnancy to term.8,14

12,13 Two reviews of the evidence by the American Psychological Association in 1989 and 2006 concluded that an abortion of an unintended pregnancy during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy “does not pose a psychological hazard for most women.” More specifically, the risk of mental health problems is no greater if a woman who has an unintended pregnancy has an elective first-trimester abortion than if she carries the pregnancy to term.8,14 - Results from a recent longitudinal study of Dutch women who had had an abortion found no link between abortion and negative mental health outcomes. Instead, mental health problems among study participants were associated with being in an unstable relationship when pregnant, experiencing negative life events in the past year, or having a history of mental health problems.15

- Women may experience a range of emotions after an abortion, and many report feeling satisfied or relieved.16 Adolescents are no more likely than older women to experience negative mental health outcomes after an abortion.

17 The best indication of a woman’s mental health after an abortion is her mental health before the abortion.8

17 The best indication of a woman’s mental health after an abortion is her mental health before the abortion.8 - There is no evidence of “postabortion stress syndrome,” but there is a body of evidence on the potential negative mental health outcomes associated with giving birth. Postpartum depression affects approximately 15% of women who give birth,18 and results of a recent longitudinal study of a cohort of Wisconsin women found that unplanned births are associated with poor mental health outcomes in later life.19

- The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has designated unintended pregnancy as a risk factor for depression during and after pregnancy.20

Inaccurate Information on Fetal Pain

Some states require abortion patients to receive inaccurate information on the ability of a fetus to feel pain at 20 weeks’ gestation.

- Some states require providers to tell patients that the fetus may be able to feel pain during an abortion procedure, which is a highly disputed assertion.

Depending on the state, this counseling may be required for all abortions or only for those at 20 weeks’ gestation or beyond.

Depending on the state, this counseling may be required for all abortions or only for those at 20 weeks’ gestation or beyond. - According to ACOG, there is “no legitimate scientific data or information that supports the statement that a fetus experiences pain at 20 weeks’ gestation.”21

- A 2005 comprehensive literature review by researchers from the University of California, San Francisco concluded that “fetal perception of pain is unlikely before the third trimester.”22 A fetus does not develop cortical function (“required for conscious perception of pain”) until 29–30 weeks’ gestation, and, without a psychological understanding of pain and the consciousness to know that stimuli are unpleasant, a fetus cannot experience pain. This literature review also cited increased risk to the pregnant woman as a reason not to administer anesthesia and analgesia to a fetus during an abortion.

Inaccurate Counseling on Medication Abortion Reversal

Some states require abortion counseling to include inaccurate information on the possibility of reversing a medication abortion.

- Starting in 2015, a few states began to adopt counseling requirements that include statements claiming a medication abortion can be “reversed” by taking a high dose of progesterone after mifepristone is administered.23

- No rigorous evidence supports the contention that a medication abortion can be reversed.

- These laws are primarily based on a case study published in 2012 about six abortion patients who had taken mifepristone—but not misoprostol, the second drug in the approved two-stage regimen—and were then given high doses of progesterone.24 The study did not adhere to basic best practices for research.25,26 For example, the authors did not apply for ethical approval and did not use a control group. A more recent observational study of more than 500 abortion patients conducted by some of the same authors27 has similar methodological shortcomings.28,29

- Scientists and doctors have not replicated the findings and have no reason to think that the method used in this case study should be practiced.

Specifically, ACOG asserts that abortion “reversal” treatments are not based on scientific evidence and do not adhere to clinical standards.26 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not evaluated the claim that medication abortion can be reversed.

Specifically, ACOG asserts that abortion “reversal” treatments are not based on scientific evidence and do not adhere to clinical standards.26 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not evaluated the claim that medication abortion can be reversed. - Medication abortion is most effective when the patient follows the evidence-based protocol and takes both drugs. Up to half of all women who take only mifepristone experience a continuing pregnancy.26

Inaccurate Information on the Risks of Abortion

Some state-mandated abortion counseling includes inaccurate information linking abortion to an increased risk of breast cancer or future infertility. However, the only risk proven to be associated with abortion are the minor risks involved in the actual procedure.

- Some states require that counseling materials include inaccurate claims that abortion poses long-term health risks. Experts dismiss these claims.

- In 2003, the National Cancer Institute published a report categorically dismissing any causal link between abortion and breast cancer.30 This position has been affirmed by ACOG and other medical associations.31

- Abortions performed in the first trimester pose virtually no long-term risk of such problems as infertility, ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, congenital malformation, or preterm or low-birth-weight delivery.32,33

- An expert panel convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in 2018 concluded that “requiring providers to inform women about risks that are not supported and are even invalidated by scientific research violates the accepted standards of informed consent.”10

- Abortion procedures themselves carry some risks, but they are extremely low. Abortion-related fatalities are very rare, occurring at a rate of 0.7 per every 100,000 procedures.

34 A first-trimester abortion is one of the safest medical procedures and carries minimal risk—less than 0.5%—of major complication requiring hospital care.35,36 While the risk of complications is higher after 12 weeks of pregnancy, the absolute risk of abortion is low when skilled practitioners are involved.

34 A first-trimester abortion is one of the safest medical procedures and carries minimal risk—less than 0.5%—of major complication requiring hospital care.35,36 While the risk of complications is higher after 12 weeks of pregnancy, the absolute risk of abortion is low when skilled practitioners are involved.

Data Center

Recent State Action On This Issue

States that have addressed this issue over the past three years are listed below.

E: State enacted a relevant measure

V: State vetoed measure

A: State adopted measure in at least one chamber

States that require women to receive counseling before having an abortion

| Kansas (2017) | E |

| Missouri (2017) | A |

| Oklahoma (2017) | E |

| Texas (2017, 2019) | A |

States that require counseling on the possibility of reversing a medication abortion

| Arkansas (2019) | E |

| Indiana (2017) | A |

| Kansas (2019) | A, V |

| Kentucky (2019) | E |

| Nebraska (2019) | E |

| North Dakota (2019) | E |

| Ohio (2019) | A |

| Oklahoma (2019) | E |

| Utah (2017) | E |

| Wisconsin (2019) | V |

References

1. American Medical Association, Opinion 2.1.1: Informed consent, 2016, https://www.ama-assn.org/about-us/code-medical-ethics.

American Medical Association, Opinion 2.1.1: Informed consent, 2016, https://www.ama-assn.org/about-us/code-medical-ethics.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Informed consent, ACOG Committee Opinion No. 439, Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2009, 114(2):401–408, http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Ethics/Informed-Consent.

3. National Abortion Federation, Ethical principles for abortion care, 2011, http://prochoice.org/wp-content/uploads/NAF_Ethical-_Principles.pdf.

4. Upadhyay UD et al., Evaluating the impact of a mandatory pre-abortion ultrasound viewing law: a mixed methods study, PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(7):e0178871.

5. Moore A, Frohwirth L and Blades N, What women want from abortion counseling in the United States: a qualitative study of abortion patients in 2008, Social Work in Health Care, 2011, 50(6):424–442.

6. Foster DG et al., Attitudes and decision making among women seeking abortions at one U.S. clinic, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2012, 44(2):117–124.

7. Dailard C, Out of compliance? Implementing the Infant Adoption Awareness Act, Guttmacher Policy Review, 2004, 7(3):10–14, http://www.guttmacher.org/about/gpr/2004/08/out-compliance-implementing-infant-adoption-awareness-act.

8. American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion, Report of the APA Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion, 2008, http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/abortion/index.aspx.

9. Brief of ACOG et al. as Amici Curiae in support of Plaintiffs-Appellants, Hope Clinic for Women v. Adams, No. 1-10-1463, Ill. App. Ct., 2011, http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Directories/Libra....

10. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States, Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2018.

11. Berglas NF et al., State-mandated (mis)information and women’s endorsement of common abortion myths, Women’s Health Issues, 2017, 27(2):129–135.

12. Cohen SA, Still true: abortion does not increase women’s risk of mental health problems, Guttmacher Policy Review, 2013, 16(2):13–17, https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2013/06/still-true-abortion-does-not-increase-womens-risk-mental-health-problems.

13. Foster DG et al., A comparison of depression and anxiety symptom trajectories between women who had an abortion and women denied one, Psychological Medicine, 2015, 45(10):2073–2082.

14. Statement of Professor Nancy Adler, University of California at San Francisco on behalf of the APA, U.S. House Committee on Government Operations, Mar. 16, 1989.

15. Ditzhuijzen JV et al., Correlates of common mental disorders among Dutch women who have had an abortion: a longitudinal cohort study, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2017, 49(2):123–131, https://www. guttmacher.org/journals/psrh/2017/05/correlates-common-mental-disorders-among-dutch-women-who-have-had-abortion.

guttmacher.org/journals/psrh/2017/05/correlates-common-mental-disorders-among-dutch-women-who-have-had-abortion.

16. Major B et al., Psychological responses of women after first-trimester abortion, Archives of General Psychiatry, 2000, 557:777–784.

17. Warren JT, Harvey SM and Henderson JT, Do depression and low self-esteem follow abortion among adolescents? Evidence from a national study, Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 2010, 42(4):230–235, https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/psrh/full/4223010.pdf.

18. APA, Postpartum Depression, 2007, http://www.apa.org/pi/women/resources/reports/postpartum-depression.aspx.

19. Herd P et al., The implications of unintended pregnancies for mental health in later life, American Journal of Public Health, 2016, 106(3):421–429.

20. Siu AL and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Screening for depression in adults: U. S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement, Journal of the American Medical Association, 2016, 315(4):380–387, http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2484345.

S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement, Journal of the American Medical Association, 2016, 315(4):380–387, http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2484345.

21. Statement of ACOG, U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, Pain of the Unborn hearing, Nov. 1, 2005.

22. Lee SJ et al., Fetal pain: a systematic multidisciplinary review of the evidence, Journal of the American Medical Association, 2005, 294(8):947–954.

23. Nash E et al., 2015 year-end state policy roundup, News in Context, Jan. 4, 2016, https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2016/01/2015-year-end-state-policy-roundup.

24. Delgado G and Davenport ML, Progesterone use to reverse the effects of mifepristone, Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 2012, 46(12):e36.

25. Louisiana Department of Public Health, Legislative Report on 2016 House Concurrent Resolution 87, 2017, http://www. dhh.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/LegisReports/HCR87RS20161.pdf.

dhh.louisiana.gov/assets/docs/LegisReports/HCR87RS20161.pdf.

26. ACOG, Facts are important: Medication abortion “reversal” is not supported by science, 2017, https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Government-Relations-and-Outre….

27. Delgado G et al., A case series detailing the successful reversal of the effects of mifepristone using progesterone, Issues in Law & Medicine, 2018, 33(1):3–14.

28. Sherman C, Medical community slams study pushing “abortion reversal” procedure, Vice News, Apr. 5, 2018, https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/a3yjd5/medical-community-slams-study-pushing-abortion-reversal-procedure.

29. Walker M, Will latest “abortion reversal” case series change practice?, MedPage Today, Apr. 4, 2018, https://www.medpagetoday.com/obgyn/pregnancy/72156.

30. National Cancer Institute, Summary report: early reproductive events and breast cancer workshop, 2003, http://www. cancer.gov/types/breast/abortion-miscarriage-risk#summary-report.

cancer.gov/types/breast/abortion-miscarriage-risk#summary-report.

31. ACOG, Induced abortion and breast cancer risk, ACOG Committee Opinion No. 434, Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2009, 113(6):1417–1418, http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Induced-Abortion-and-Breast-Cancer-Risk.

32. Gold RB and Nash E, State abortion counseling policies and the fundamental principles of informed consent, Guttmacher Policy Review, 2007, 10(4):6–13, https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2007/11/state-abortion-counseling-policies-and-fundamental-principles-informed-consent.

33. ACOG, Frequently asked questions: induced abortion, 2015, http://www.acog.org/~/media/For%20Patients/faq043.pdf.

34. Zane S et al., Abortion-related mortality in the United States, 1998–2010, Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2015, 126(2):258–265, https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4554338/.

nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4554338/.

35. Upadhyay UD et al., Incidence of emergency room visits and complications after abortion, Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2015, 125(1):175–183.

36. White K, Carroll E and Grossman D, Complications from first-trimester aspiration abortion: a systematic review of the literature, Contraception, 2015, 92(5):422–438.

Supporting Resources

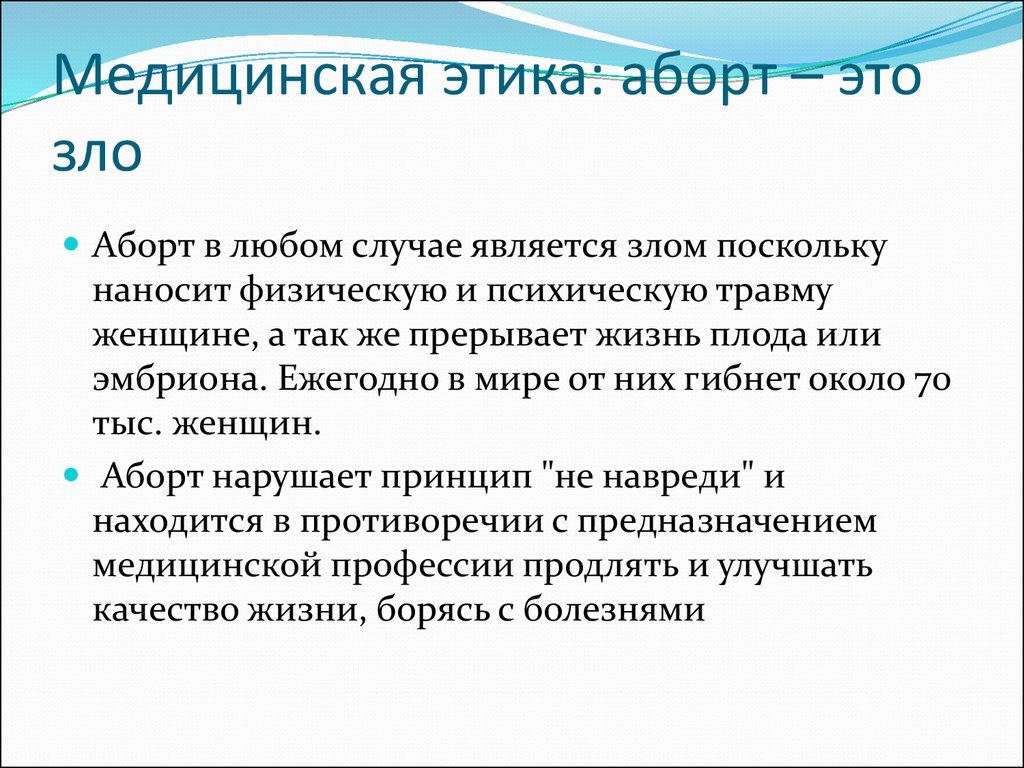

Termination of pregnancy from the point of view of a medical psychologist

A modern woman is very different from her great-grandmother. The main difference is the possibility of reproductive choice, which our ancestors did not have.

The priorities of contemporaries are arranged differently, career, desire for personal growth, travel. The whole world is open to a woman today, and the birth of a child does not always fit into her plans.

It often happens that pregnancy just happens at the wrong time. Lack of material base, education, work, loneliness often push a woman to terminate a pregnancy.

According to statistics, there are more than 55 million abortions worldwide. More than half a million is made in Russia. Despite the fact that with the development of medicine, mortality from abortions in clinical settings is minimized, such cases do occur. 30% of maternal deaths in Russia are associated with abortion.

Abortion is the only operation that does not cure diseases and is contrary to the very nature of a woman. This is an interruption of the natural process. No matter how long, and no matter what method it is produced, it never passes without a trace for the physical and psychological health of a woman. Often women do not think about the real dangers of abortion and consider it a means of contraception.

Abortion translated from Latin - abortus - "miscarriage".

Can only be performed in a specialized medical clinic with a license, exclusively by a specialist doctor. Every woman has the right to independently decide on the issue of motherhood, which is enshrined in federal law No. 323 "On the fundamentals of protecting the health of citizens in the Russian Federation"

323 "On the fundamentals of protecting the health of citizens in the Russian Federation"

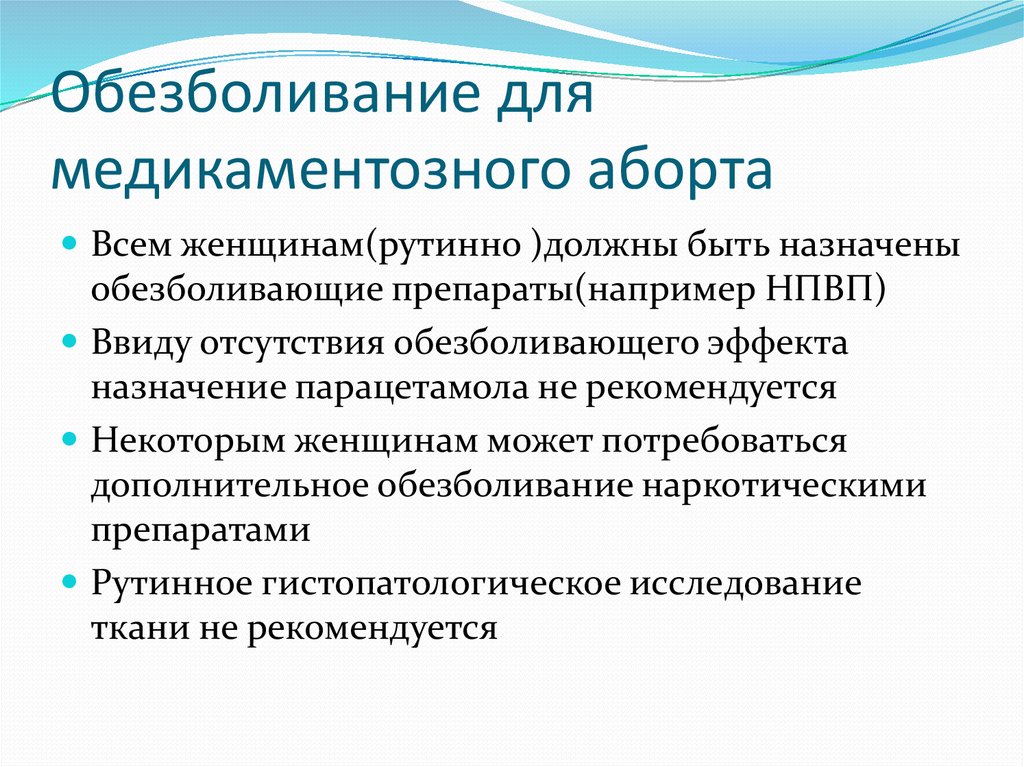

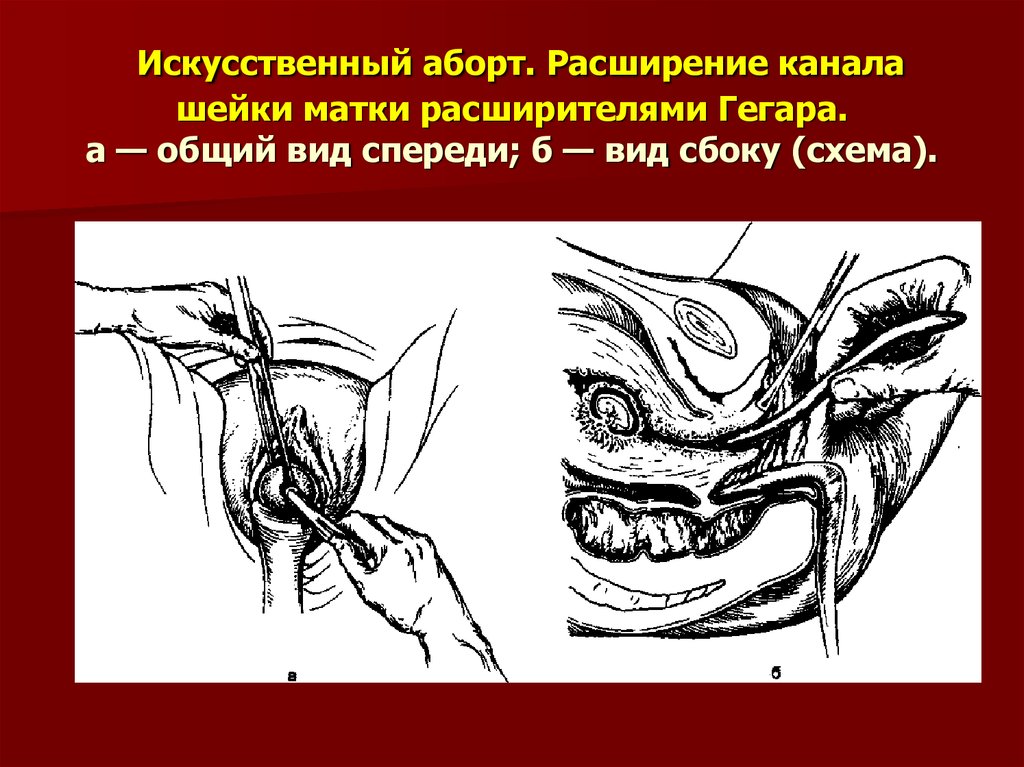

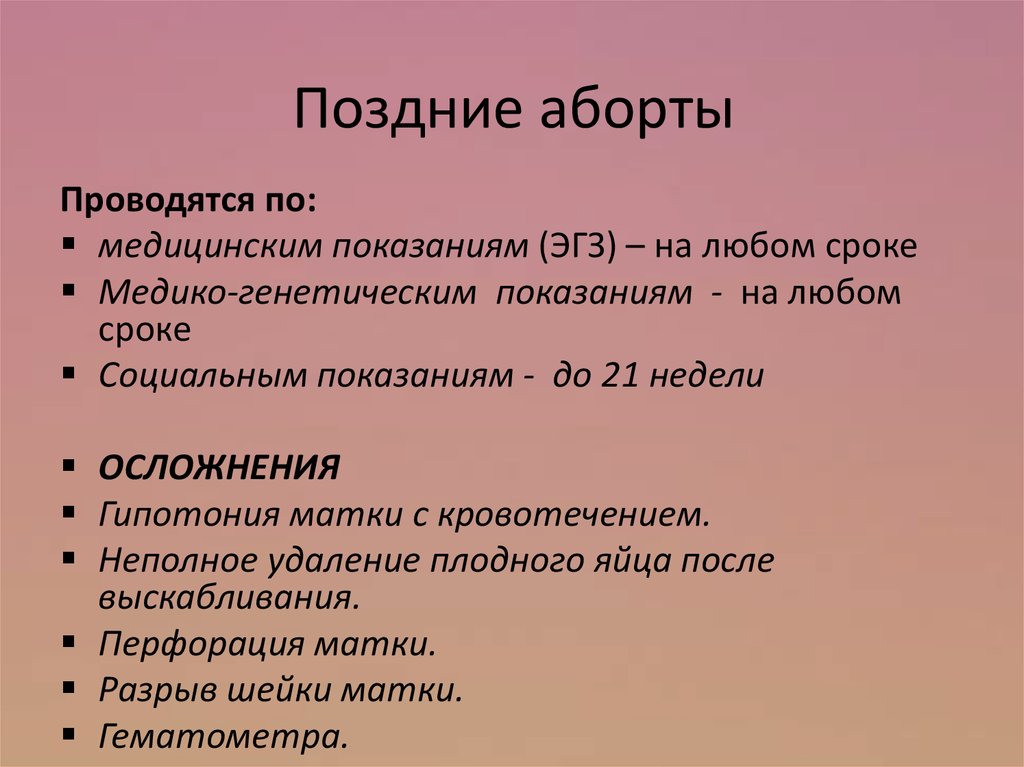

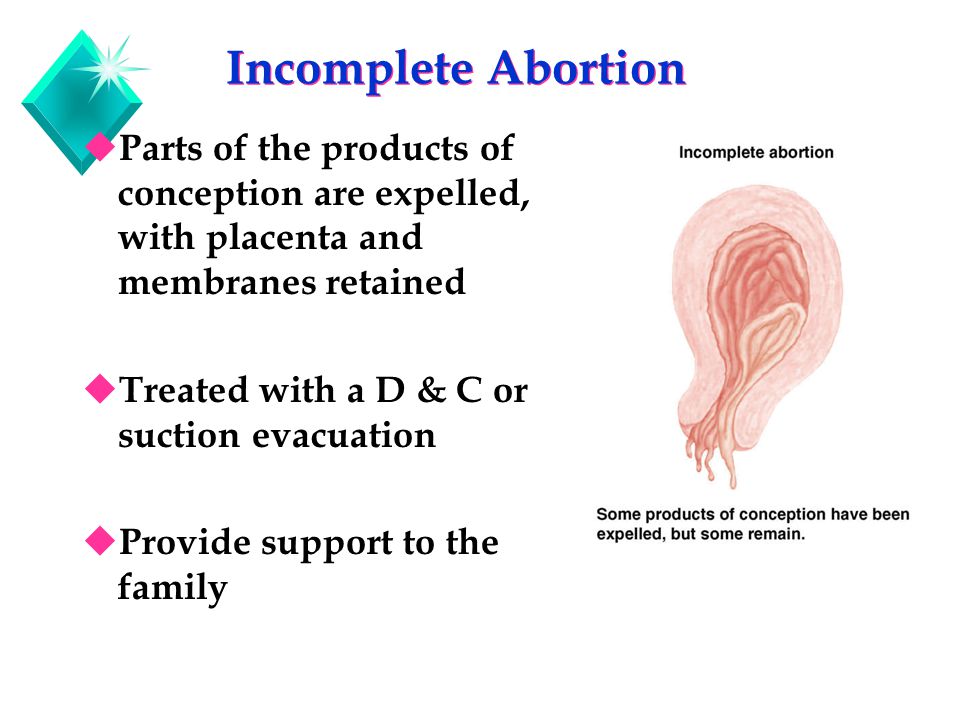

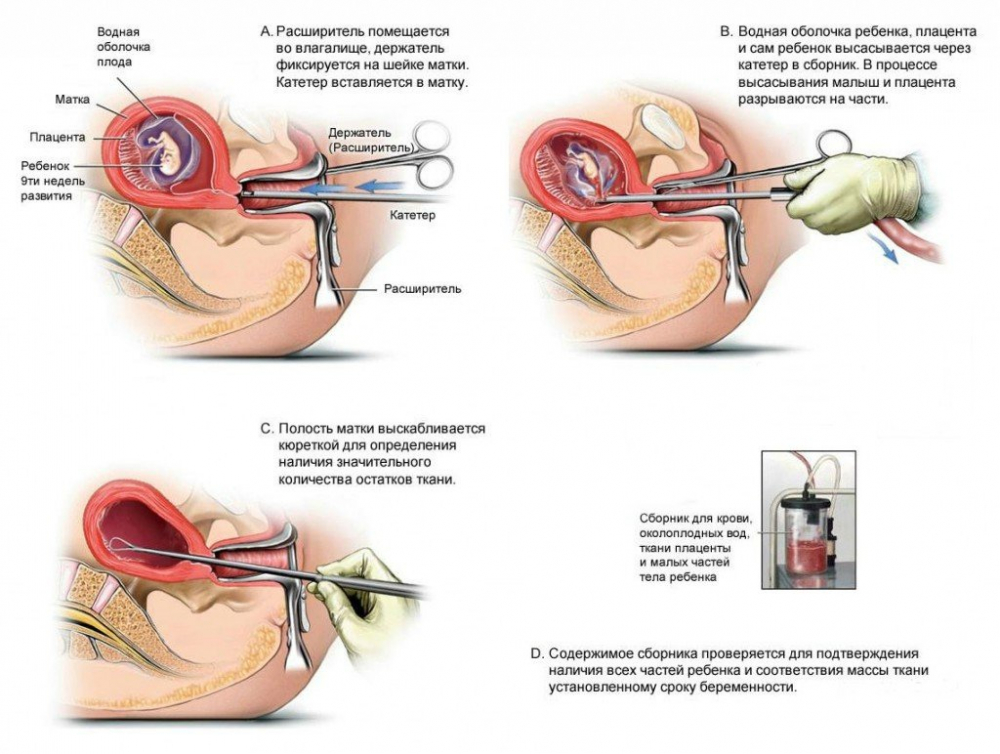

Three methods of artificial termination of pregnancy are used. The most common of these is the "scraping" method, today WHO has recognized it as obsolete. In second place is the vacuum aspiration method or mini-abortion and medical abortion.

The most common method of abortion "curettage" can cause great complications already during the operation. Such an abortion is performed almost blindly, and artificial opening of the uterus can result in her injury. This abortion can cause severe bleeding, and the most serious consequence of such an abortion may be the removal of the uterus.

This termination of pregnancy is carried out under anesthesia, therefore, it is necessary to remember the possible consequences of the use of anesthesia. In addition to the risk of an allergic reaction, there may be a heart rhythm failure, respiratory failure, a violation of the functions of the liver and other internal organs.

Vacuum aspiration is a less traumatic way for a woman to terminate a pregnancy, but the risk of anesthesia remains.

Medical abortion is performed for up to 9 weeks, on an outpatient basis and up to 12 weeks in an inpatient setting, requires virtually no anesthesia. But it also deals a significant blow to the hormonal system of a woman. Uterine bleeding may also occur or the abortion will be incomplete. In this case, vacuum extraction and treatment will be required.

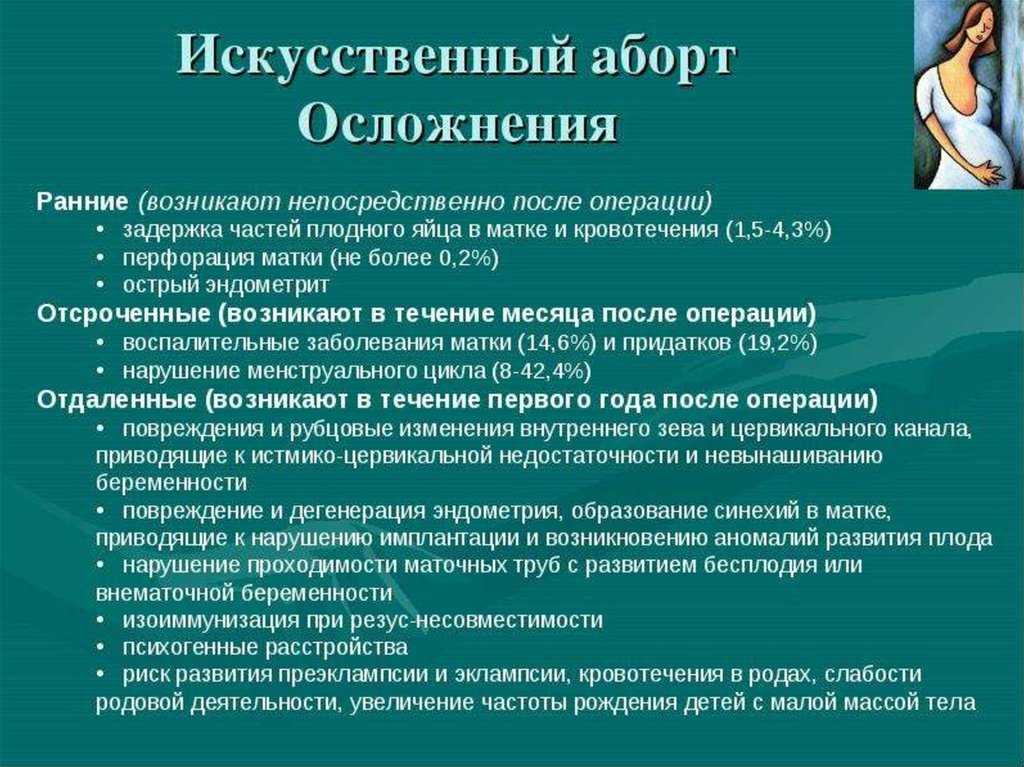

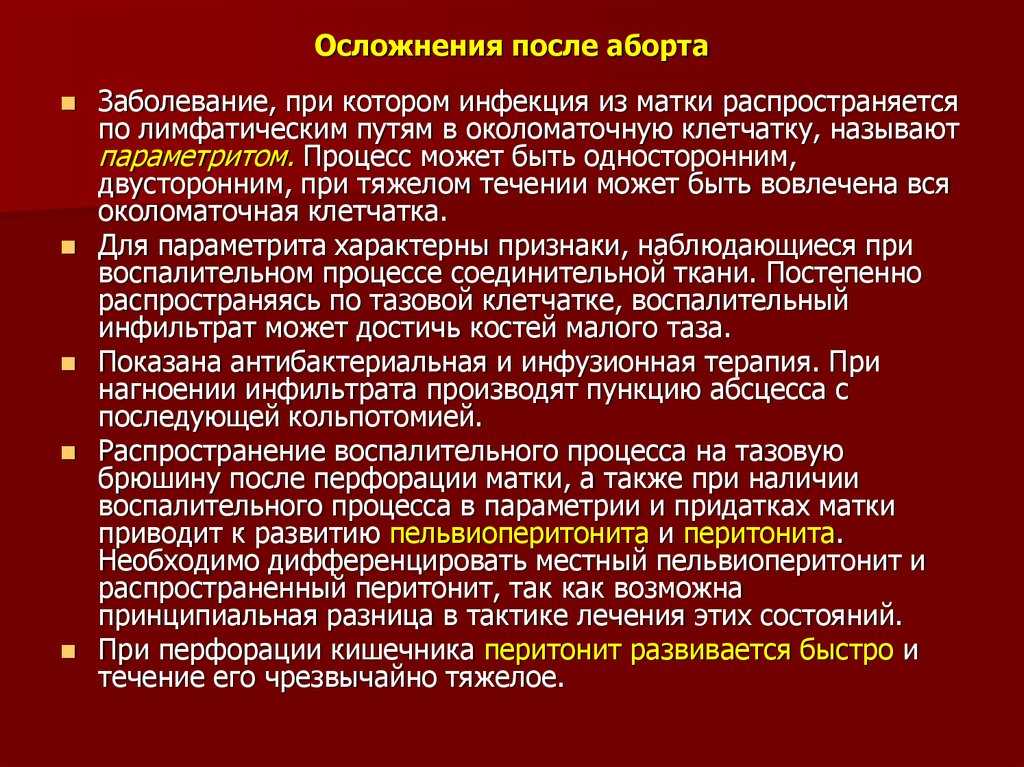

During and after an abortion, various complications are possible.

Early complications of abortion

- profuse bleeding,

- rupture of the uterine walls,

- filling of the uterine cavity with blood,

- the occurrence of painful contractions,

- incomplete removal of the dead fetus.

There are later consequences of abortion. They can appear in the first weeks after the abortion.

- sepsis,

- metroendometritis (inflammatory processes on the mucosa and muscles of the uterus),

- adnexitis (inflammation of the appendages).

Long-term complications of abortion may occur even several years after the abortion. Each abortion undermines the health of a woman and never goes completely without a trace.

- menstrual disorders,

- amenorrhea,

- obstruction of the fallopian tubes,

- endometriosis,

- inflammation of the genital organs,

- difficulties in conception and pregnancy,

- ectopic pregnancy,

- miscarriage,

- premature birth and complications in them,

- infertility,

- increased risk of breast cancer,

- increased risk of developing uterine tumors.

In case of termination of the first pregnancy, the body can change the “carrying program” of the pregnancy to the “miscarriage program”. And the subsequent, already desired pregnancy will end in spontaneous abortion at an early stage. The body will launch a new program, and the pregnancy will not be saved.

A woman going for an abortion does not think about the fact that she may be forever deprived of the happy opportunity to become a mother. Termination of pregnancy cannot go unnoticed by the whole organism as a whole. First of all, it affects the menstrual cycle and the work of the ovaries. But, in addition to the ovaries, there is a violation in the work of such organs as the thyroid gland, adrenal glands, pituitary gland. There comes an imbalance of hormonal, immune, renal and hepatic functions, regulation of blood pressure, blood volume. The woman becomes irritable, sleep worsens, fatigue increases. That is, there is an "ideal state" for the penetration of any infection that provokes the development of infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Termination of pregnancy cannot go unnoticed by the whole organism as a whole. First of all, it affects the menstrual cycle and the work of the ovaries. But, in addition to the ovaries, there is a violation in the work of such organs as the thyroid gland, adrenal glands, pituitary gland. There comes an imbalance of hormonal, immune, renal and hepatic functions, regulation of blood pressure, blood volume. The woman becomes irritable, sleep worsens, fatigue increases. That is, there is an "ideal state" for the penetration of any infection that provokes the development of infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Very often, when deciding to have an abortion, a woman is aware of the possible consequences for her body, but does not want to know about the consequences for her psyche.

Artificial termination of pregnancy is contrary to the very nature of man. The body does not know if it is carrying a wanted or unwanted pregnancy. The “program of childbearing” laid down in the woman strives to preserve the pregnancy. No matter how the pregnancy is terminated, it is unnatural for the woman's body.

No matter how the pregnancy is terminated, it is unnatural for the woman's body.

Abortion causes not only physical but also psychological damage to a woman's body. After an abortion, a woman often experiences mental discomfort. 60% of women develop post-abortion syndrome - PAS. In addition, it is necessary to take into account the moral and ethical harm of abortion. Even those who do not believe in God consider this procedure a sin and experience pangs of conscience and guilt.

What is PAS - a set of mental consequences and illnesses that can result from an abortion.

PAS can occur immediately after an abortion and manifest itself in the form of such experiences as a feeling of emptiness, loss, grief. Often women feel guilty, become irritable, aggressive. Anxiety and depressive disorders can often develop.

Abortion is the strongest stress for a woman's psyche. In fact, this is the death of a child, even if not yet born. This feeling is reinforced by the fact that the woman herself made the choice in favor of an abortion.

Every woman who terminates a pregnancy feels guilty. Abortion is generally condemned by society, condemnation from the staff, misunderstanding of loved ones, articles and videos on the Internet only increase the feeling of guilt. After an abortion, a woman is left alone with herself. As a rule, she always understands that all the reasons why she refused to give birth (except for medical reasons) are better called excuses.

When pregnancy comes, a woman feels something inside herself, she feels that this is her child, she can imagine how he will grow and develop, what he would become when he was born. She subconsciously feels that he wanted to be born, but she did not give it to him.

Conditions such as panic and helplessness accompany PAS during the first time after an abortion. After a perfect abortion, there remains a deep feeling that everything, nothing can be returned, no one will help. Relatives often do not know how to behave, and the phrases “you will still give birth”, “now is not the best time for children”, “where would you live with him” and others cause only anger and irritation.

A woman has many questions to which there are no answers. How to be further? Do you speak to loved ones? How will your relationship with your husband develop? How will this affect children? Will I still be able to get pregnant and give birth? What “punishment” will I bear for my sin?

When you decide to have an abortion and sign your consent, no one gives you a list of answers to these questions.

Aggression, irritability, anger, "hardening", intolerance. These qualities can manifest themselves both in the first days after an abortion, and after a fairly long time. Sometimes women talk about how they cannot communicate with pregnant women and feel annoyed when they meet strangers on the street. Some say that even commercials showing small children have become unpleasant to them. All this often leads to the fact that a woman is fenced off from the environment, reduces communication with loved ones to a minimum.

Violation of relationships in a couple up to physical and psychological disgust. Abortion will forever stand in the relationship between a man and a woman. Guilt may be the third in such a pair for many years. The future of an aborted couple is often in question.

Abortion will forever stand in the relationship between a man and a woman. Guilt may be the third in such a pair for many years. The future of an aborted couple is often in question.

An unplanned pregnancy is not the fault of only the woman or only the man. Very often, partners begin to mutually blame each other for what happened. A woman often blames a man for pushing her to have an abortion. Many couples break up after an abortion. Many women say that after an abortion it is difficult to physically let a man near them. Libido decreases, it becomes more difficult for a woman to achieve orgasm, in rare cases anorgasmia, frigidity, vaginismus develop.

Negative attitudes towards people and life events in general can persist for a long time after an abortion. Even after a few years, a woman may feel guilty about having an abortion, for example, carrying a desired pregnancy. Because she saved this child, but did not allow the previous one to be born. Some admit that when they become pregnant and give birth to a child after an abortion, instead of warm feelings, they sometimes experience irritation and anger.

The hormonal system is the basis of the woman's psyche. When pregnancy occurs, it is rebuilt so that a woman can bear and give birth to a child. If the pregnancy is terminated, serious disturbances occur in the hormonal system, the woman loses the ability to control her own emotions and feelings.

Endless mood changes, depression, conflicts, insomnia, breaking of consciousness and the existing model of perception of the world - all these are the mental consequences of abortion.

According to the law, every pregnant woman has the right to make her own decision: to give birth or not. But, before deciding to take such a step, every woman should weigh everything well and think it over, because the consequences of an abortion can appear even many years after the operation itself.

Abortion will not solve your financial or housing problems.

Abortion will not solve family problems.

Abortion will not make you happier.

Abortion is always a choice against life.

Think, maybe this child will become your joy and support in the future.

(c) Yulia Afanasyeva. Leading psychologist GBUZ "UMRD"

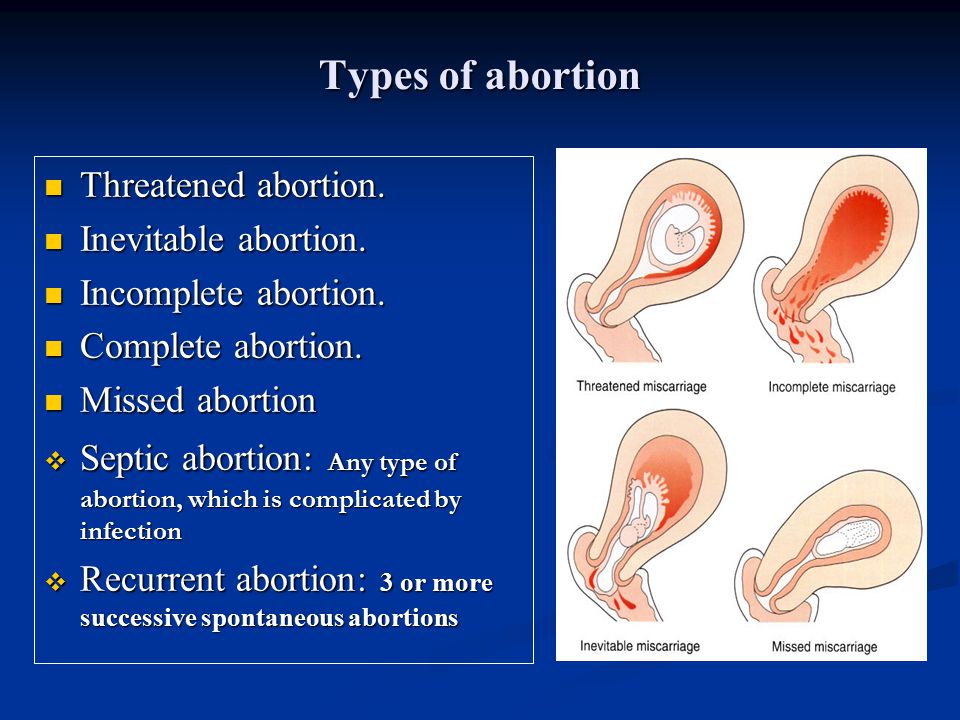

Therapy of threatened abortion in the first trimester | Zaidieva Z.S., Magomethanova D.M.

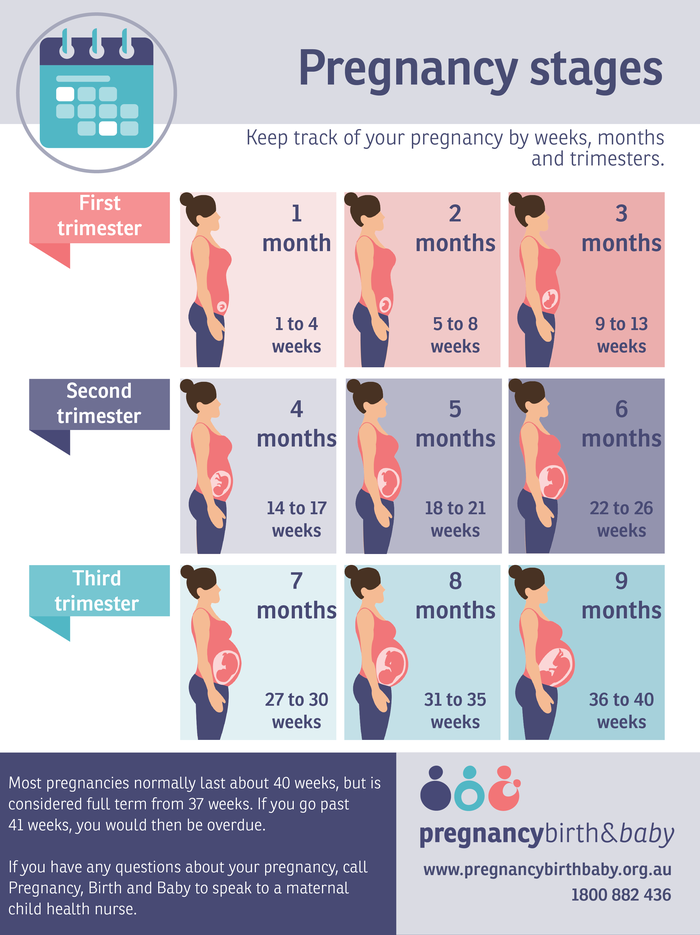

The etiological structure of various gestational complications, including early termination of pregnancy, is diverse [1,4,5,7,8]. The causal mechanisms that determine the development of pathology in each individual case, other things being equal, are still under study. The first trimester of pregnancy is the most significant, since during this period embryogenesis, the formation of the placenta and the complex relationship between mother and fetus take place. The threat of abortion in the first trimester often complicates the normal course of these processes, which can lead to spontaneous abortions, the development of placental insufficiency, intrauterine fetal suffering [3,5,12]. Despite the large number of scientific studies [1,2,3,6,8] devoted to this problem, to date, issues related to the management of this contingent of pregnant women, especially at the first, most critical stages of gestation, remain unresolved.

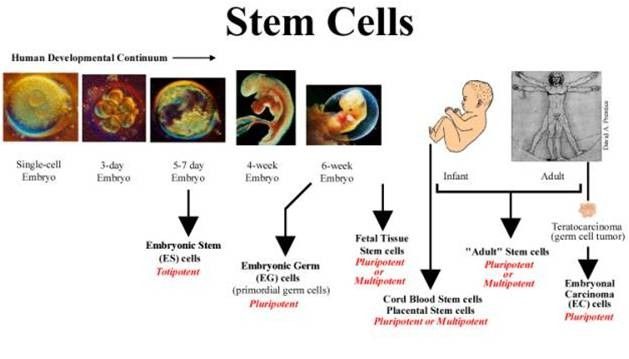

At the current stage of scientific research, many researchers come to the conclusion that there is a close relationship and mutual regulation between the endocrine and immune systems in the early stages of implantation [4,5,8,10,11,12]. It is undeniable that progesterone plays a very important role in a woman's body. Even before the onset of pregnancy, it causes decidual transformation of the endometrium, preparing it for the implantation of a fertilized egg, and during the gestation period it promotes the growth and vascularization of the myometrium, reduces the excitability of the uterus by neutralizing the action of oxytocin, suppresses tissue immunological reactions, etc. [1,5,6,13 ]. It has been proven that progesterone contributes to the full secretory transformation of the endometrium, which is necessary for the introduction of the blastocyst. In addition, during pregnancy, gestagens ensure the growth and development of the myometrium, its vascularization and relaxation by leveling the effect of oxytocin and reducing the synthesis of prostaglandins [3,7,8,14].

Complications at the initial stages of gestation can be the result of both defective steroidogenesis and insufficiency of the endometrial receptor apparatus. For successful implantation of the embryo, it is necessary to coordinate the readiness of the endometrium for implantation with the development of the embryo (the so-called “implantation window”) [3,6,8]. In such situations, the therapeutic approach should take into account the etiology of the formation of an inferior luteal phase and level out unfavorable predisposing factors. In a chronic inflammatory process in the uterus and appendages, in addition to the appointment of individually selected etiological therapy, immunomodulatory therapy, hormonal correction is necessary, which allows normalizing the state of the endometrium and ensuring adequate blastogenesis and placentation.

Progesterone plays a key role in preparing the uterine mucosa for implantation. It is generally accepted that for a normal pregnancy outcome, a woman's immune system must recognize it. During a normal pregnancy, progesterone receptors are present in peripheral blood lymphocytes, and the proportion of cells containing such receptors increases with increasing gestational age. In the event of a threatened abortion, the proportion of cells containing progesterone receptors is significantly lower than in healthy women at the same gestational age. A number of scientists believe that an increase in the number of progesterone receptors during pregnancy may be caused by the presence of an embryo, which acts as a chorionic alloantigenic (foreign) stimulator [6,9,eleven].

During a normal pregnancy, progesterone receptors are present in peripheral blood lymphocytes, and the proportion of cells containing such receptors increases with increasing gestational age. In the event of a threatened abortion, the proportion of cells containing progesterone receptors is significantly lower than in healthy women at the same gestational age. A number of scientists believe that an increase in the number of progesterone receptors during pregnancy may be caused by the presence of an embryo, which acts as a chorionic alloantigenic (foreign) stimulator [6,9,eleven].

According to A.R. Genazzani [10], about 15% of all pregnancies end in spontaneous abortion, which is one of the most common complications of pregnancy. According to statistics, about one in four pregnant women experience one or more spontaneous miscarriages.

They talk about habitual miscarriage if there have been three or more repeated spontaneous miscarriages. This pathology, according to V.M. Sidelnikova [5], occurs in approximately 1–3% of all women. At the same time, the risk of miscarriage after three repeated spontaneous miscarriages reaches 55%. In most cases (50–60%), miscarriages are caused by hormonal disorders, structural abnormalities of the chromosomes of the embryo, infections, endocrine disorders, anatomical defects in the mother, etc. Many researchers [1,3,5,7,14] believe that most miscarriages with an unclear etiology may be caused by an abnormal immune response of the mother's body to the paternal antigens of the fetus. There is now increasing evidence that progesterone appears to play an important role in normalizing the immune response in the early stages of pregnancy. With a normal pregnancy, the corpus luteum, and later the placenta, produce a sufficient amount of progesterone. In its presence, activated lymphocytes produce a special protein - progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF), which has an anti-abortion effect.

At the same time, the risk of miscarriage after three repeated spontaneous miscarriages reaches 55%. In most cases (50–60%), miscarriages are caused by hormonal disorders, structural abnormalities of the chromosomes of the embryo, infections, endocrine disorders, anatomical defects in the mother, etc. Many researchers [1,3,5,7,14] believe that most miscarriages with an unclear etiology may be caused by an abnormal immune response of the mother's body to the paternal antigens of the fetus. There is now increasing evidence that progesterone appears to play an important role in normalizing the immune response in the early stages of pregnancy. With a normal pregnancy, the corpus luteum, and later the placenta, produce a sufficient amount of progesterone. In its presence, activated lymphocytes produce a special protein - progesterone-induced blocking factor (PIBF), which has an anti-abortion effect.

As you know, while maintaining pregnancy against the background of luteal insufficiency, primary placental insufficiency is further formed. For its prevention, full preparation for pregnancy and proper management of patients with threatening and habitual miscarriage are necessary.

For its prevention, full preparation for pregnancy and proper management of patients with threatening and habitual miscarriage are necessary.

For the treatment of threatened and habitual miscarriage, it is practical and highly effective to directly affect progesterone receptors by replenishing the lack of endogenous progesterone with the help of drugs - progestogens. A modern effective progestogen drug is Duphaston (dydrogesterone), in the structure of which the methyl group in position 10 is located in the a-position, hydrogen at carbon 9is in the b-position, in addition, there is a double bond between carbohydrates 6 and 7. Changing the configuration of the molecule leads to the fact that Duphaston is easily absorbed when administered orally. Dydrogesterone at a dose of 20–30 mg induces a full-fledged secretion phase in the endometrium. Animal studies confirm the high ability of dydrogesterone to maintain pregnancy.

Duphaston is a potent orally effective progestogen that is close in its molecular structure and pharmacological action to endogenous progesterone and therefore has a high affinity (affinity) for progesterone receptors.

Unlike many progestogens, it is not a derivative of testosterone, its structure differs from the structure of most synthetic progestogens, as a result of which it does not cause any of the side effects characteristic of most of these drugs.

The advantages of the chemical structure of dydrogesterone are the higher bioavailability of the drug after oral administration and the absence of metabolites with androgenic or estrogenic activity. The main metabolite of Duphaston is 20 a-dihydroxydydrogesterone, which also has progestogenic activity.

Recent evidence has shown that the anti-abortion effects of progesterone during early pregnancy are also due to modulation of the maternal immune response. It has been proven that in the presence of Duphaston, activated lymphocytes synthesize a protein (a blocking factor induced by progesterone). The latter prevents inflammatory and secondary thrombotic reactions of trophoblast rejection by increasing asymmetric non-toxic blocking antibodies, as well as blocking the degranulation of natural killer cells and by inducing T-lymphocyte-2 (Th3) dependent cytokines, shifting the balance towards Th3 cells, i. e. cytoprotective immune response [4,7]. Compensating for the insufficiency of the luteal phase in case of a threatened or habitual termination of pregnancy, Duphaston also has a relaxing effect on the muscles of the uterus.

e. cytoprotective immune response [4,7]. Compensating for the insufficiency of the luteal phase in case of a threatened or habitual termination of pregnancy, Duphaston also has a relaxing effect on the muscles of the uterus.

Unlike other synthetic progestogens, Duphaston does not cause feminization of the male fetus and does not have side effects on liver function and blood clotting, such manifestations as acne, deepening of the voice, hirsutism and masculinization of the genital organs of the female fetus, has no metabolic effects (for example , changes in the lipid spectrum of blood and glucose concentration), and also does not affect the activity of the pituitary-ovarian system and does not cause atrophy of the adrenal glands.

One tablet of Duphaston contains 10 mg of dydrogesterone. After oral administration of dihydrogesterone, 63% of the administered dose is eliminated in the urine, with 85% of this amount excreted within 24 hours. Almost complete renal excretion of the administered dose ends after 72 hours.

In case of a threatened miscarriage, it is recommended to include in the treatment complex the intake of 40 mg of this drug at a time, then 10 mg every 8 hours until the symptoms of abortion disappear. With a habitual miscarriage, 10 mg of Dufaston are prescribed 2 times a day until the 18–20th week of pregnancy.

There is increasing evidence that the immunomodulatory effects of hormones are essential for maintaining normal endometrial function. The results of studies conducted by A.R. Genazzani [10] show the role of the immune system during pregnancy and, in particular, an increase in the number of progesterone receptors on lymphocytes as pregnancy progresses. In the presence of progesterone or its Duphaston analogue, lymphocytes produce a progesterone-induced blocking factor. As a result of the immunological effects of PIBF, the activity of T-helper cells of type II (Th3), which contribute to the normal course of pregnancy, increases, and the activity of T-helper cells of type I (TM), which has an adverse effect on pregnancy, decreases. The authors showed that dydrogesterone (Duphaston) is also able to shift the Th3 / Th2 ratio in a favorable direction and thereby increase the likelihood of a successful pregnancy. This effect has been confirmed in two clinical studies showing that dydrogesterone reduces the incidence of spontaneous abortion in women with a threatened miscarriage or a history of recurrent miscarriage.

The authors showed that dydrogesterone (Duphaston) is also able to shift the Th3 / Th2 ratio in a favorable direction and thereby increase the likelihood of a successful pregnancy. This effect has been confirmed in two clinical studies showing that dydrogesterone reduces the incidence of spontaneous abortion in women with a threatened miscarriage or a history of recurrent miscarriage.

In-depth studies on the role of PIBF in maintaining pregnancy were carried out by J. Szekeres-Bartho et al. [13,14]. It is generally accepted that for a normal pregnancy outcome, it is necessary that the immune system be able to recognize it. In a normal pregnancy, progesterone receptors are present in peripheral blood lymphocytes, and the proportion of cells containing such receptors increases with increasing gestational age. However, in women at high risk of premature termination of pregnancy, the proportion of cells containing progesterone receptors is significantly lower than in healthy women at the same stage of pregnancy. After a transplant or blood transfusion, the number of cells containing progesterone receptors is comparable to that in pregnant women. This suggests that in pregnant women, an increase in the number of progesterone receptors on lymphocytes may be caused by the presence of the fetus, which acts as an alloantigenic stimulator. In the presence of progesterone, these lymphocytes produce a specific 34-kD mediator protein, or PIBF. The concentration of PIBF increases with increasing gestational age, but disappears after 40 weeks with a normal pregnancy. Thanks to the immunological influence of PIBF, pregnancy is maintained. PIBF changes the balance of cytokines in the immune system. However, there are two types of cytokines: cytokines produced by Th2 T helper cells, which have an adverse effect on pregnancy, and cytokines produced by Th3 T helper cells, which contribute to the normal course of pregnancy. In the presence of PIBF, there is a shift towards the predominance of Th3 cytokines. A simultaneous decrease in the production of Th2 cytokines entails a decrease in the activity of natural killer cells (NKC) and a normal pregnancy outcome.

After a transplant or blood transfusion, the number of cells containing progesterone receptors is comparable to that in pregnant women. This suggests that in pregnant women, an increase in the number of progesterone receptors on lymphocytes may be caused by the presence of the fetus, which acts as an alloantigenic stimulator. In the presence of progesterone, these lymphocytes produce a specific 34-kD mediator protein, or PIBF. The concentration of PIBF increases with increasing gestational age, but disappears after 40 weeks with a normal pregnancy. Thanks to the immunological influence of PIBF, pregnancy is maintained. PIBF changes the balance of cytokines in the immune system. However, there are two types of cytokines: cytokines produced by Th2 T helper cells, which have an adverse effect on pregnancy, and cytokines produced by Th3 T helper cells, which contribute to the normal course of pregnancy. In the presence of PIBF, there is a shift towards the predominance of Th3 cytokines. A simultaneous decrease in the production of Th2 cytokines entails a decrease in the activity of natural killer cells (NKC) and a normal pregnancy outcome. Against the background of taking Duphaston, there is a significant increase in the concentration of PIBF-positive lymphocytes, which entails the above-described changes in the immune system aimed at maintaining pregnancy. In the absence of PIBF, the concentration of TM cytokines increases and, at the same time, natural killer cells are activated, which increases the likelihood of abortion.

Against the background of taking Duphaston, there is a significant increase in the concentration of PIBF-positive lymphocytes, which entails the above-described changes in the immune system aimed at maintaining pregnancy. In the absence of PIBF, the concentration of TM cytokines increases and, at the same time, natural killer cells are activated, which increases the likelihood of abortion.

With the threat of miscarriage or premature birth, the level of PIBF is significantly lower than during a normal pregnancy. With a lack of PIBF, the activity of natural killer cells increases by about 4 times. It is now believed that the increased activity of the ECC is one of the factors causing early termination of pregnancy.

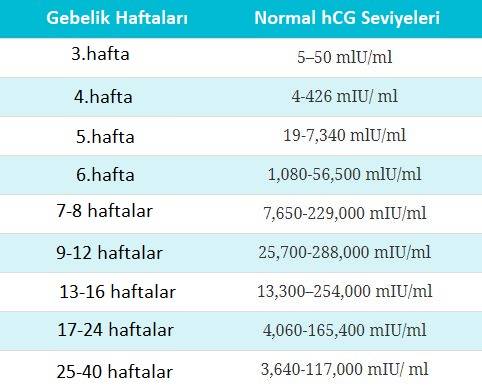

M.Y. El-Zibdeh [9] publishes data on the results of two studies, the purpose of which was to find out whether it is possible to improve the outcome of pregnancy with the help of dydrogesterone in women suffering from recurrent miscarriage. 114 women with a history of recurrent miscarriage (mean number of previous miscarriages 3. 3) were randomly divided into three groups and received: dydrogesterone (Duphaston) orally 10 mg twice a day; or human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) intramuscularly at 5000 IU every 4 days; or received no treatment. Therapy was started immediately after pregnancy was confirmed and stopped at 12 weeks' gestation. In the group of women taking Duphaston, the frequency of abortions significantly (p<0.05) decreased compared to the control group by 27%, in the hCG group - by 16.6% (p<0.05). In the group taking Duphaston, the abortion rate was 14.6%, in the hCG group - 16.6%, in the control group - 20%. Duphaston was well tolerated by patients. The frequency of pregnancy complications was approximately the same in all three groups.

3) were randomly divided into three groups and received: dydrogesterone (Duphaston) orally 10 mg twice a day; or human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) intramuscularly at 5000 IU every 4 days; or received no treatment. Therapy was started immediately after pregnancy was confirmed and stopped at 12 weeks' gestation. In the group of women taking Duphaston, the frequency of abortions significantly (p<0.05) decreased compared to the control group by 27%, in the hCG group - by 16.6% (p<0.05). In the group taking Duphaston, the abortion rate was 14.6%, in the hCG group - 16.6%, in the control group - 20%. Duphaston was well tolerated by patients. The frequency of pregnancy complications was approximately the same in all three groups.

In another study by M.Y. El-Zibdeh [9] studied the effectiveness of the drug Duphaston in the onset of miscarriage. Bleeding in early pregnancy is common and occurs in 30–50% of all pregnancies. In the author's opinion, the cause of bleeding should be determined before starting treatment. It is necessary to know which of their patients is at risk. An increased risk of miscarriage is observed in the following situations: the age of the mother is over 35; father's age over 53; the presence of genetic defects in one of the parents; spontaneous miscarriages or the birth of a dead child in history; the birth of children with congenital developmental anomalies. A total of 146 pregnant women with mild to moderate bleeding were included in the study. The patients were divided into two groups by random sampling. In one group, in addition to standard treatment, women received Duphaston (dydrogesterone) 10 mg twice a day. The second group was the control. Treatment with the drug was stopped 1 week after the bleeding stopped. Treatment was canceled with an increase in the intensity of bleeding, signs of discharge of the contents of the fetal membrane, an increase in body temperature, no signs of growth of the fetal bladder after a week of observation, insufficiently pronounced or absent fetal pole with a fetal bladder size of 25 mm or more, or no cardiac activity.

It is necessary to know which of their patients is at risk. An increased risk of miscarriage is observed in the following situations: the age of the mother is over 35; father's age over 53; the presence of genetic defects in one of the parents; spontaneous miscarriages or the birth of a dead child in history; the birth of children with congenital developmental anomalies. A total of 146 pregnant women with mild to moderate bleeding were included in the study. The patients were divided into two groups by random sampling. In one group, in addition to standard treatment, women received Duphaston (dydrogesterone) 10 mg twice a day. The second group was the control. Treatment with the drug was stopped 1 week after the bleeding stopped. Treatment was canceled with an increase in the intensity of bleeding, signs of discharge of the contents of the fetal membrane, an increase in body temperature, no signs of growth of the fetal bladder after a week of observation, insufficiently pronounced or absent fetal pole with a fetal bladder size of 25 mm or more, or no cardiac activity. The frequency of abortions significantly decreased (p<0.05) in the group of women treated with Duphaston compared with the control group. Pregnancy ended with timely delivery in 75% of the subjects in the group taking Duphaston and in 66.6% in the control group. The incidence of pregnancy complications, including preeclampsia, intrauterine growth retardation, bleeding or congenital malformations, was almost the same in both groups.