Progress of labor

Stages of Labor - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

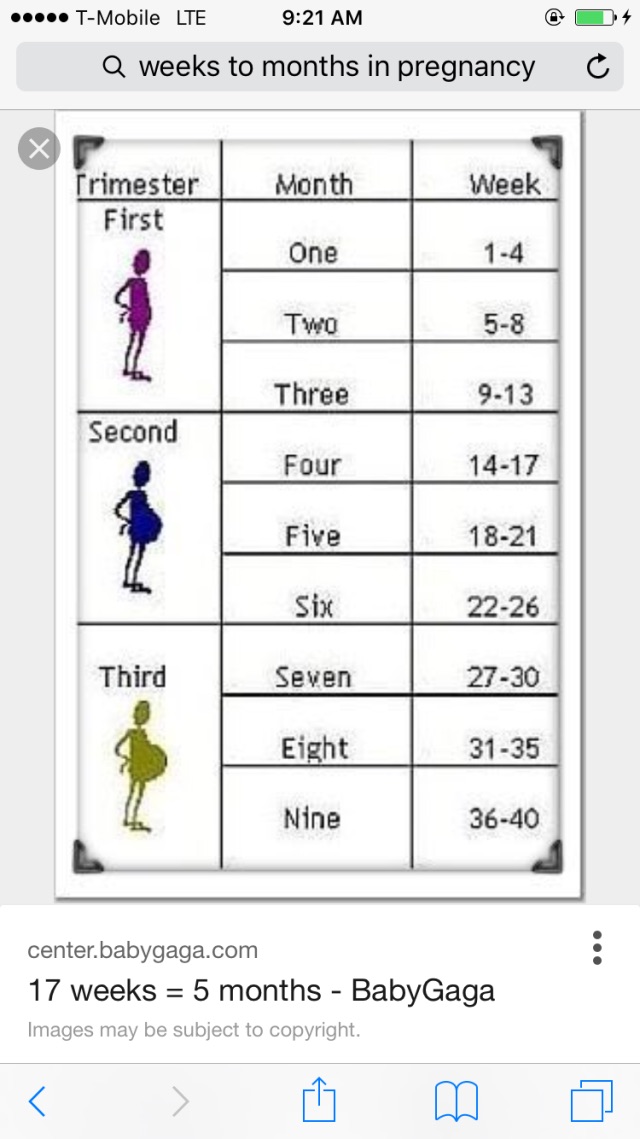

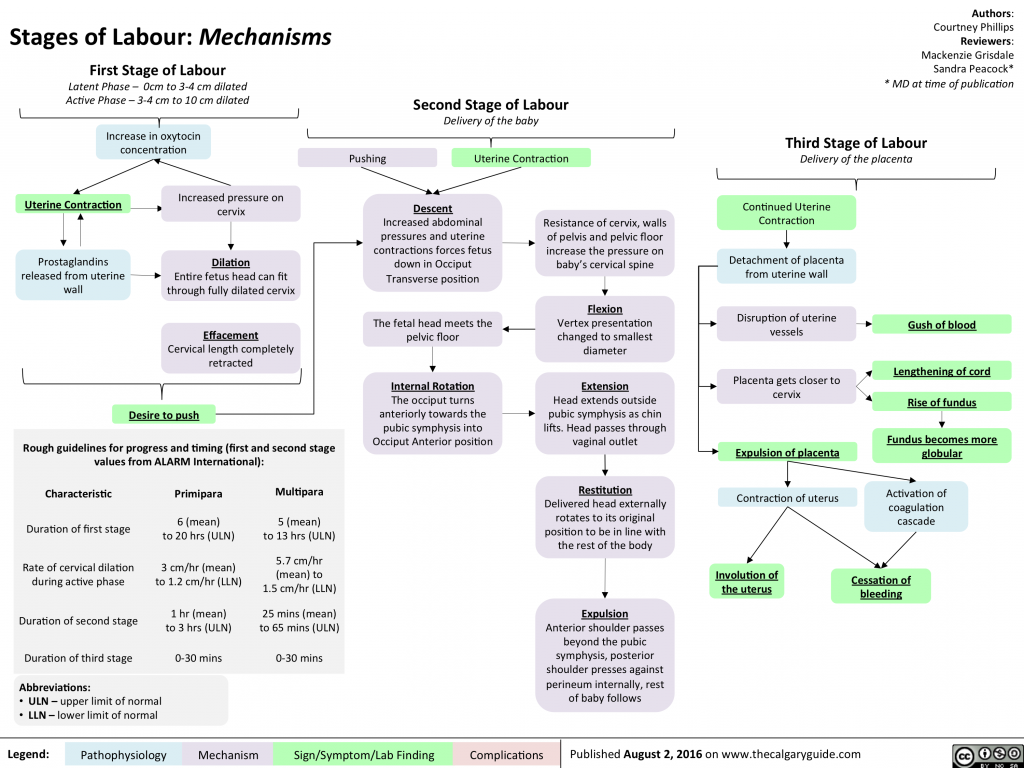

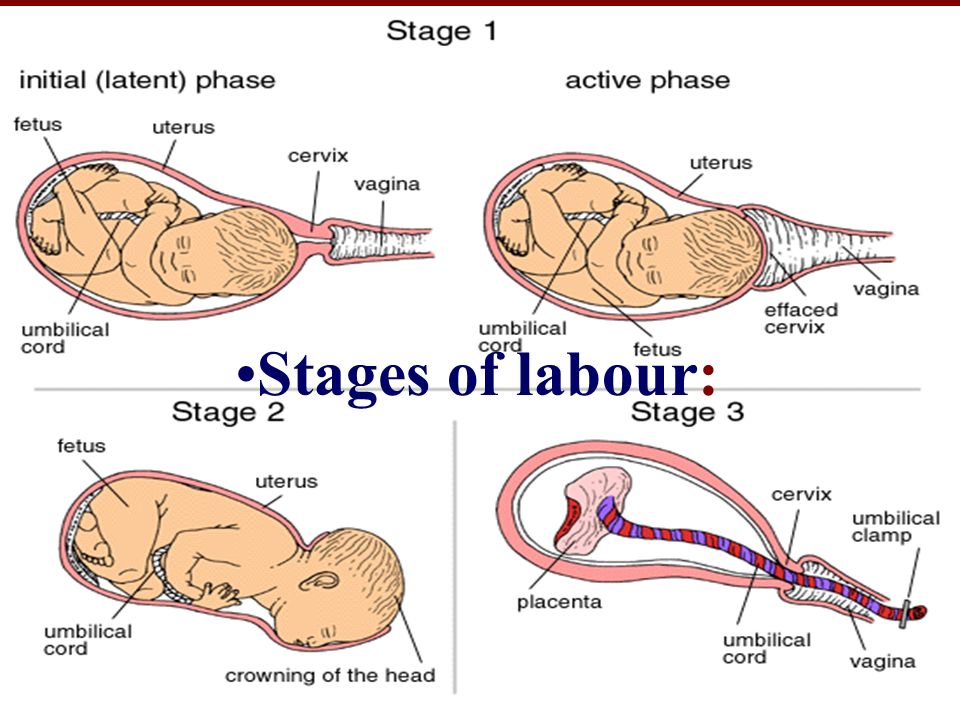

Labor is a process that subdivides into three stages. The first stage starts when labor begins and ends with full cervical dilation and effacement. The second stage commences with complete cervical dilation and ends with the delivery of the fetus. The third stage initiates after the fetus is delivered and ends when the placenta is delivered. This activity outlines the stages of labor and its relevance to the interprofessional team in managing women in labor.

Objectives:

Summarize the three stages of labor.

Describe potential complications that may arise during each stage of labor.

Identify what therapies may be targeted at the different stages of labor to result in better patient outcomes.

Review the importance of accurate communication between the interprofessional team members regarding the stages of labor, leading to improved patient outcomes.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

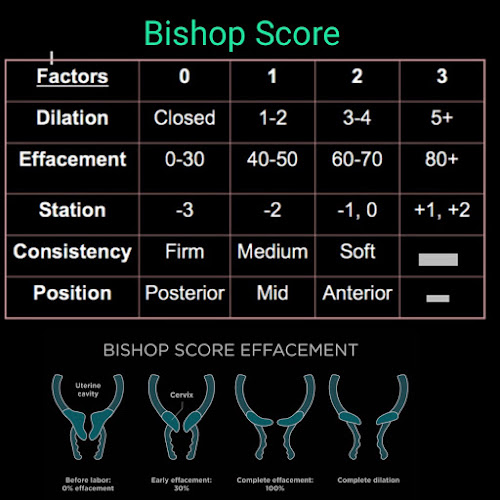

Labor is the process through which a fetus and placenta are delivered from the uterus through the vagina.[1] Human labor divides into three stages. The first stage is further divided into two phases. Successful labor involves three factors: maternal efforts and uterine contractions, fetal characteristics, and pelvic anatomy.[1] This triad is classically referred to as the passenger, power, and passage.[1] Clinicians typically use multiple modalities to monitor labor. Serial cervical examinations are used to determine cervical dilation, effacement, and fetal position, also known as the station. Fetal heart monitoring is employed nearly continuously to assess fetal well-being throughout labor. Cardiotocography is used to monitor the frequency and adequacy of contractions. Medical professionals use the information they obtain from monitoring and cervical exams to determine the patient's stage of labor and monitor labor progression.

Initial Evaluation and Presentation of Labor

Women will often self-present to obstetrical triage with concern for the onset of labor. Common chief complaints include painful contractions, vaginal bleeding/bloody show, and fluid leakage from the vagina. It is up to the clinician to determine if the patient is in labor, defined as regular, clinically significant contractions with an objective change in cervical dilation and/or effacement.[1] When women first present to the labor and delivery unit, vital signs, including temperature, heart rate, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and blood pressure, should be obtained and reviewed for any abnormalities. The patient should be placed on continuous cardiotocographic monitoring to ensure fetal wellbeing. The patient's prenatal record, including obstetric history, surgical history, medical history, laboratory, and imaging data, should undergo review. Finally, a history of present illness, review of systems, and physical exam, including a sterile speculum exam, will need to take place.

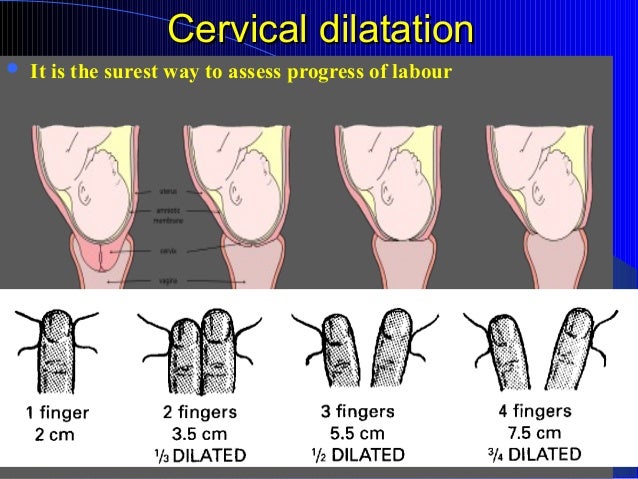

During the sterile speculum exam, clinicians will look for signs of rupture of membranes such as amniotic fluid pooling in the posterior vaginal canal. If the clinician is unsure whether or not a rupture of membranes has occurred, additional testing such as pH testing, microscopic exam looking for ferning of the fluid, or laboratory testing of the fluid can be the next step.[2] Amniotic fluid has a pH of 7.0 to 7.5, which is more basic than normal vaginal pH. A sterile gloved exam should be done to determine the degree of cervical dilation and effacement. The measurement of cervical dilation is made by locating the external cervical os and spreading one's fingers in a ‘V’ shape, and estimating the distance in centimeters between the two fingers. Effacement is measured by estimating the percentage remaining of the length of the thinned cervix compared to the uneffaced cervix. During the cervical exam, confirmation of the presenting fetal part is also necessary. Bedside ultrasound can be employed to confirm the presentation and position of the fetal presenting part. Particular mention should be noted in the case of breech presentation due to its increased risks regarding fetal morbidity and mortality compared with the cephalic presenting fetus.

Particular mention should be noted in the case of breech presentation due to its increased risks regarding fetal morbidity and mortality compared with the cephalic presenting fetus.

Management of Normal Labor

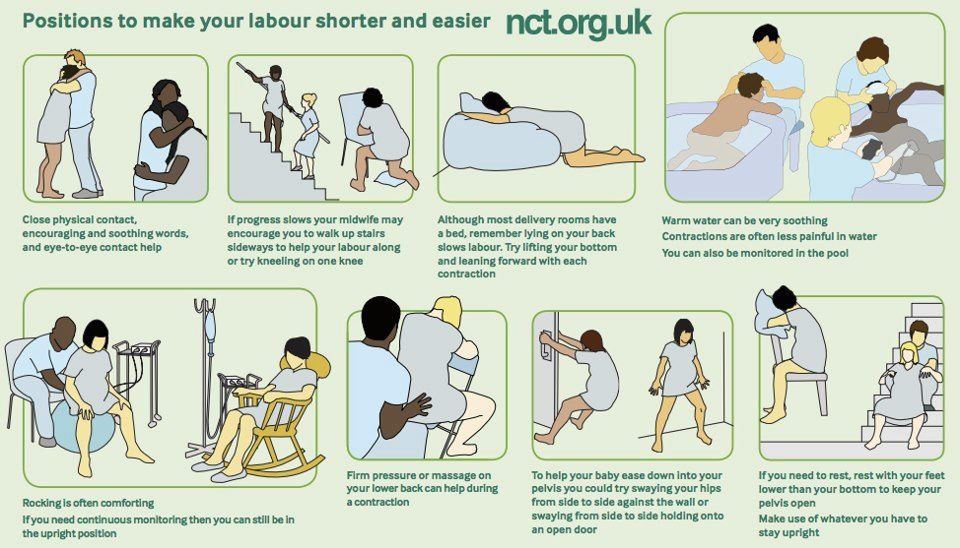

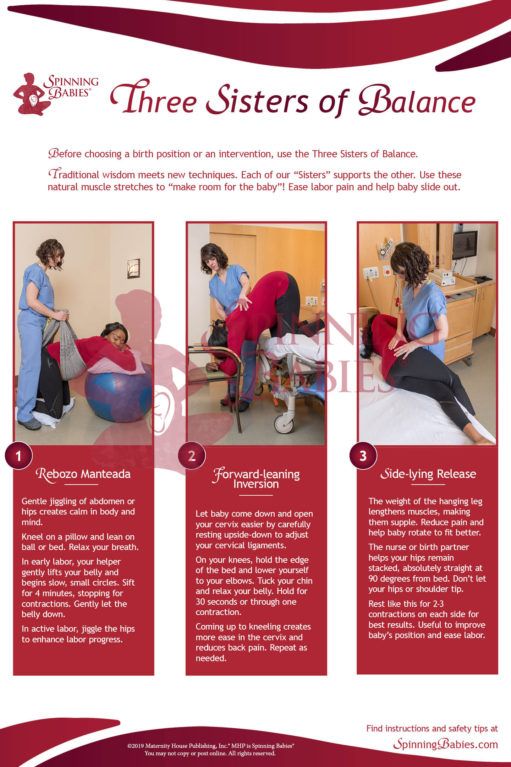

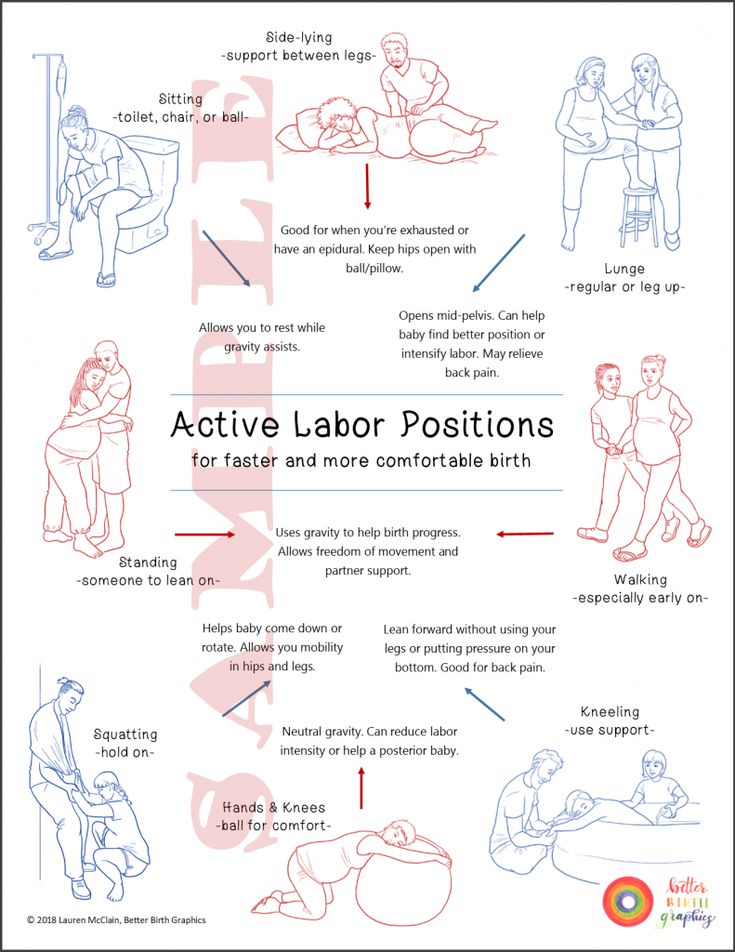

Labor is a natural process, but it can suffer interruption by complicating factors, which at times necessitate clinical intervention. The management of low-risk labor is a delicate balance between allowing the natural process to proceed while limiting any potential complications.[3] During labor, cardiotocographic monitoring is often employed to monitor uterine contractions and fetal heart rate over time. Clinicians monitor fetal heart tracings to evaluate for any signs of fetal distress that would warrant intervention as well as the adequacy or inadequacy of contractions. Vital signs of the mother are taken at regular intervals and whenever concerns arise regarding a clinical status change. Laboratory testing often includes the hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelet count and is sometimes repeated following delivery if significant blood loss occurs. Cervical exams are usually performed every 2 to 3 hours unless concerns arise and warrant more frequent exams. Frequent cervical exams are associated with a higher risk of infection, especially if a rupture of membranes has occurred. Women should be allowed to ambulated freely and change positions if desired.[3] An intravenous catheter is typically inserted in case it is necessary to administer medications or fluids. Oral intake should not be withheld. If the patient remains without food or drink for a prolonged period of time, intravenous fluids should be considered to help replace losses but do not need to be used continuously on all laboring patients.[3] Analgesia is offered in the form of intravenous opioids, inhaled nitrous oxide, and neuraxial analgesia in those who are appropriate candidates.[4] Amniotomy is considered on an as-needed basis for fetal scalp monitoring or labor augmentation, but its routine use should be discouraged.[3] Oxytocin may be initiated to augment contractions found to be inadequate.

Cervical exams are usually performed every 2 to 3 hours unless concerns arise and warrant more frequent exams. Frequent cervical exams are associated with a higher risk of infection, especially if a rupture of membranes has occurred. Women should be allowed to ambulated freely and change positions if desired.[3] An intravenous catheter is typically inserted in case it is necessary to administer medications or fluids. Oral intake should not be withheld. If the patient remains without food or drink for a prolonged period of time, intravenous fluids should be considered to help replace losses but do not need to be used continuously on all laboring patients.[3] Analgesia is offered in the form of intravenous opioids, inhaled nitrous oxide, and neuraxial analgesia in those who are appropriate candidates.[4] Amniotomy is considered on an as-needed basis for fetal scalp monitoring or labor augmentation, but its routine use should be discouraged.[3] Oxytocin may be initiated to augment contractions found to be inadequate.

First Stage of Labor

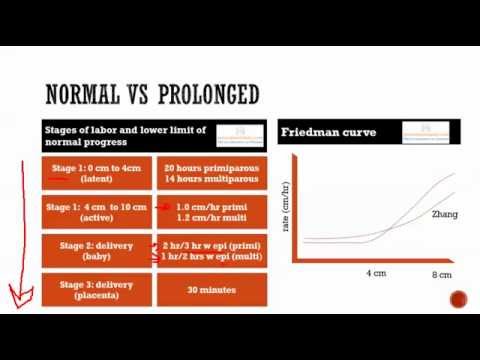

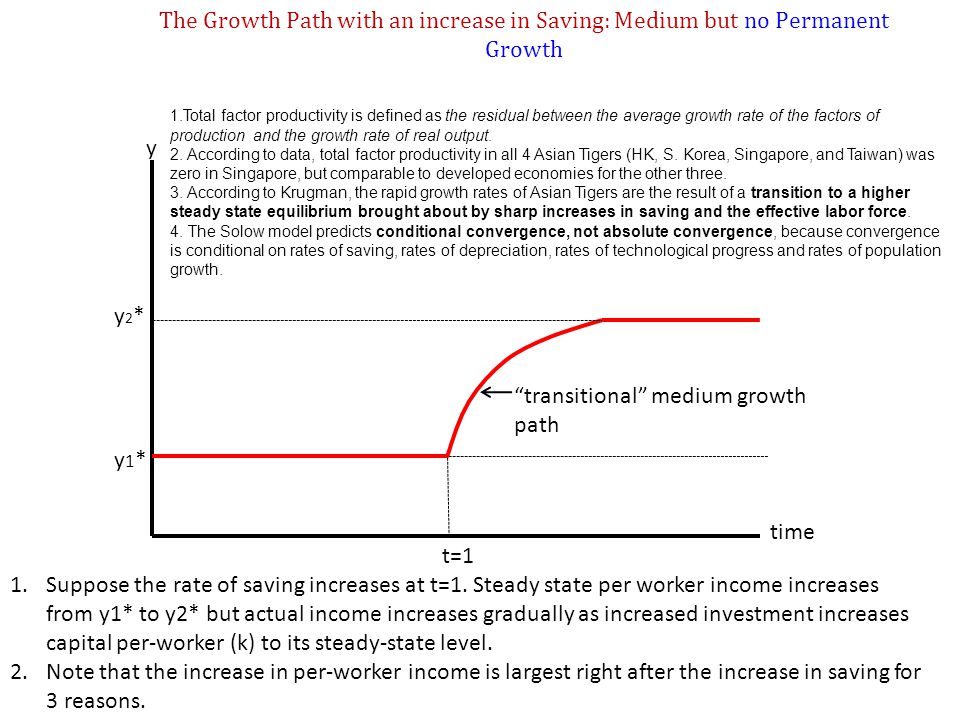

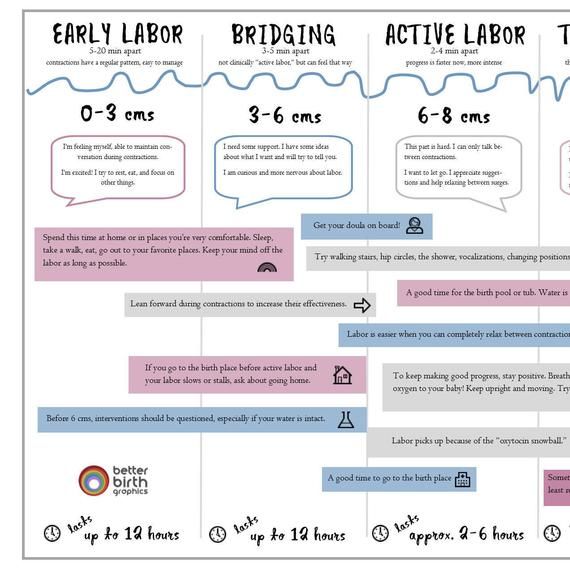

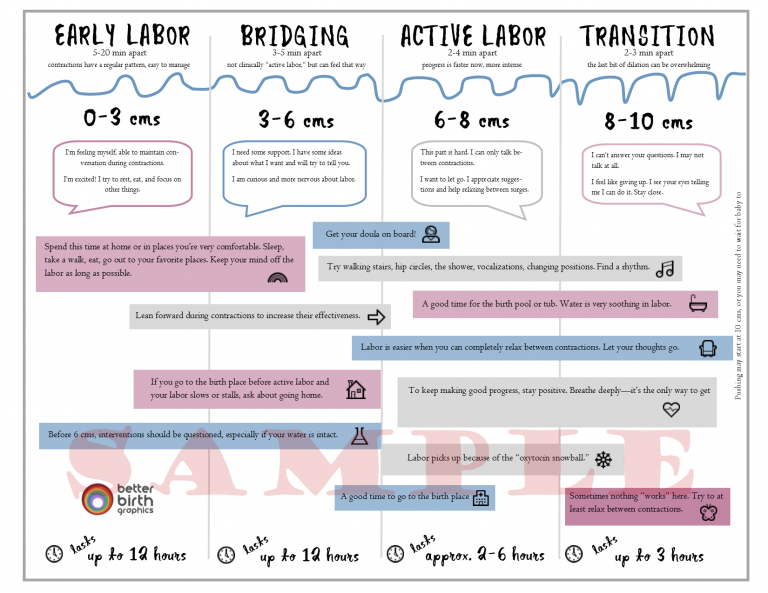

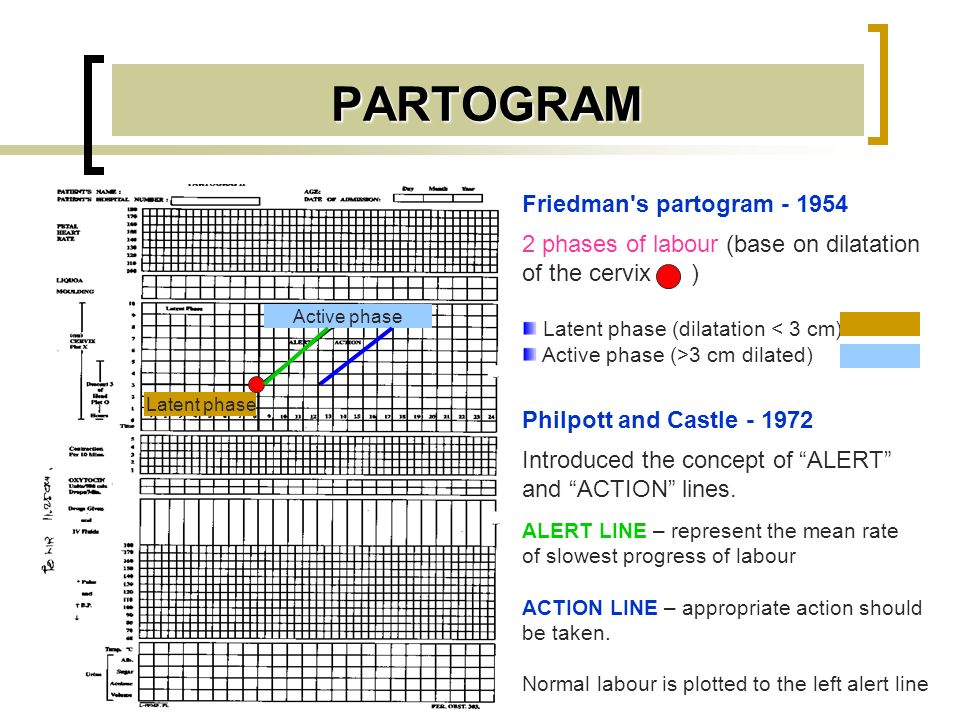

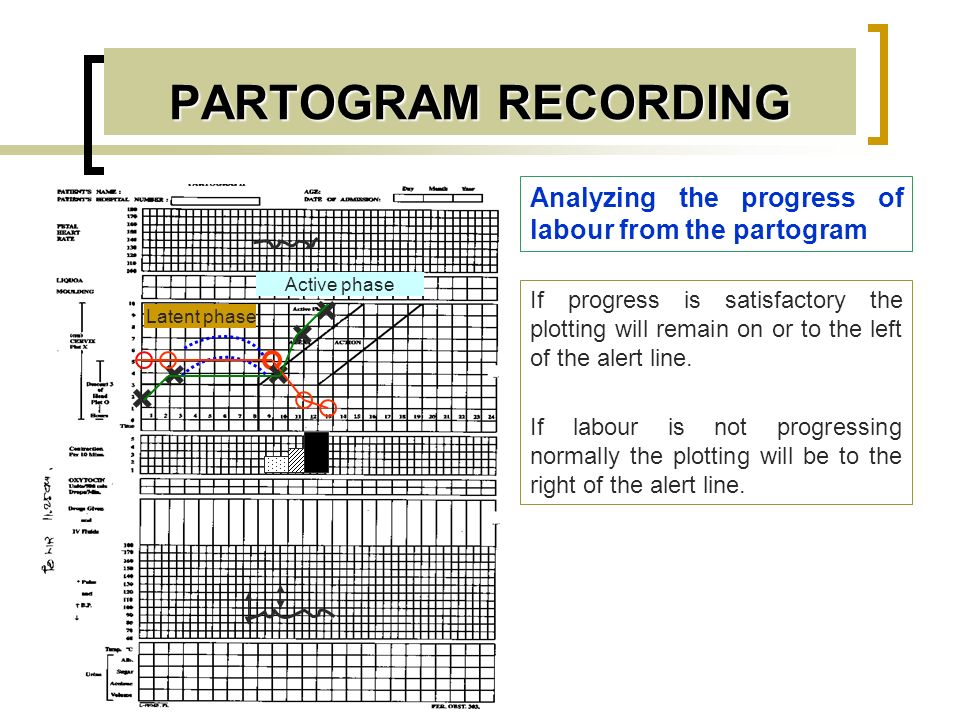

The first stage of labor begins when labor starts and ends with full cervical dilation to 10 centimeters.[1] Labor often begins spontaneously or may be induced medically for a variety of maternal or fetal indications.[5] Methods of inducing labor include cervical ripening with prostaglandins, membrane stripping, amniotomy, and intravenous oxytocin.[5] Although precisely determining when labor starts may be inexact, labor is generally defined as beginning when contractions become strong and regularly spaced at approximately 3 to 5 minutes apart.[1] Women may experience painful contractions throughout pregnancy that do not lead to cervical dilation or effacement, referred to as false labor. Thus, defining the onset of labor often relies on retrospective or subjective data. Friedman et al. were some of the first to study labor progress and defined the beginning of labor as starting when women felt significant and regular contractions.[6] He graphed cervical dilation over time and determined that normal labor has a sigmoidal shape. Based on the analysis from his labor graphs, he proposed that labor has three divisions. First, a preparatory stage marked by slow cervical dilation, with large biochemical and structural changes. This is also known as the latent phase of the first stage of labor. Second, a much shorter and rapid dilational phase is also known as the active phase of the first stage of labor. Third, a pelvic division phase, which takes place during the second stage of labor.[1]

Based on the analysis from his labor graphs, he proposed that labor has three divisions. First, a preparatory stage marked by slow cervical dilation, with large biochemical and structural changes. This is also known as the latent phase of the first stage of labor. Second, a much shorter and rapid dilational phase is also known as the active phase of the first stage of labor. Third, a pelvic division phase, which takes place during the second stage of labor.[1]

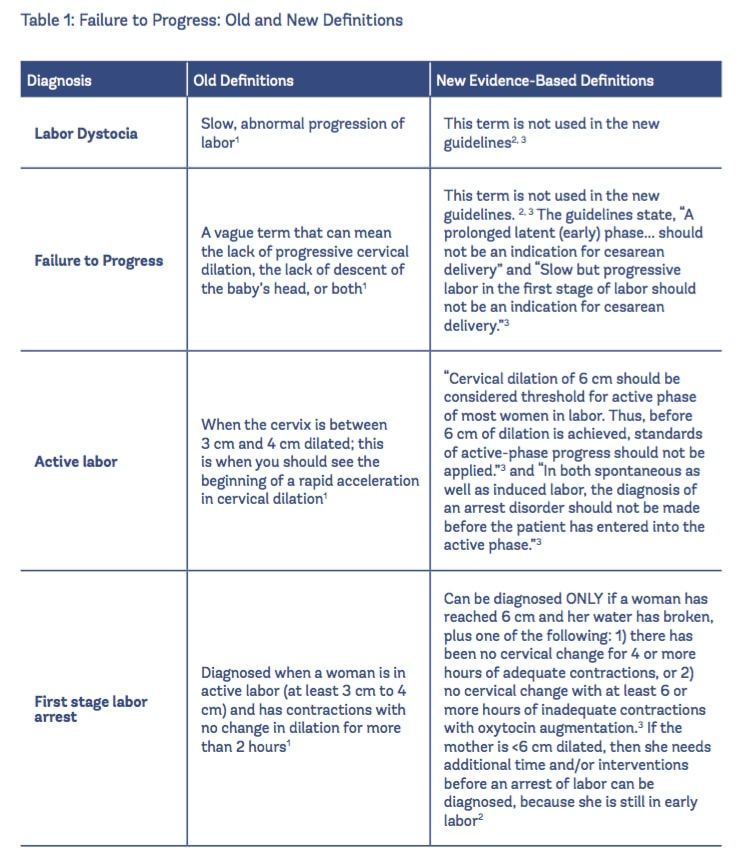

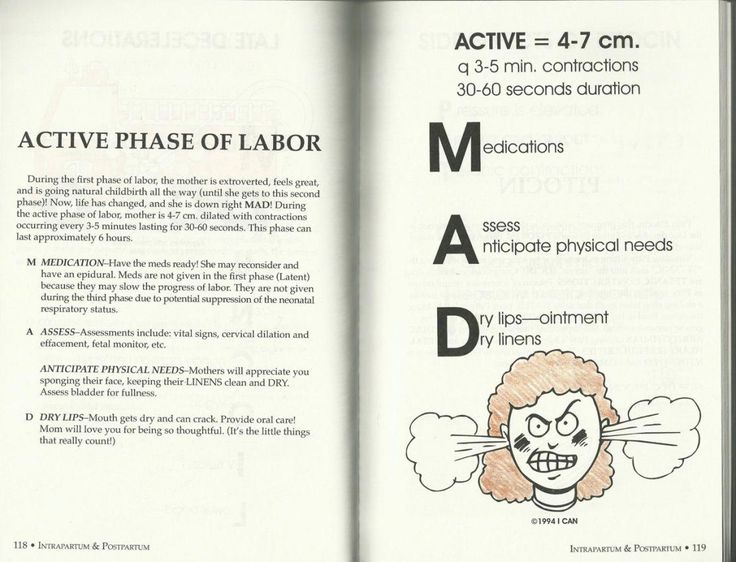

The first stage of labor is further subdivides into two phases, defined by the degree of cervical dilation. The latent phase is commonly defined as the 0 to 6 cm, while the active phase commences from 6 cm to full cervical dilation. The presenting fetal part also begins the process of engagement into the pelvis during the first stage. Throughout the first stage of labor, serial cervical exams are done to determine the position of the fetus, cervical dilation, and cervical effacement. Cervical effacement refers to the cervical length in the anterior-posterior plane. When the cervix is completely thinned out, and no length is left, this is referred to as 100 percent effacement.[1] The station of the fetus is defined relative to its position in the maternal pelvis. When the bony fetal presenting part is aligned with the maternal ischial spine, the fetus is 0 station. Proximal to the ischial spines are stations -1 centimeter to -5 centimeters, and distal to the ischial spines is +1 to +5 station.[1] The first stage of labor contains a latent phase and an active phase. During the latent phase, the cervix dilates slowly to approximately 6 centimeters. The latent phase is generally considerably longer and less predictable with regard to the rate of cervical change than is observed in the active phase. A normal latent phase can last up to 20 hours and 14 hours in nulliparous and multiparous women, respectively, without being considered prolonged.[1] Sedation can increase the duration of the latent phase of labor.[7] The cervix changes more rapidly and predictably in the active phase until it reaches 10 centimeters and cervical dilation and effacement are complete.

When the cervix is completely thinned out, and no length is left, this is referred to as 100 percent effacement.[1] The station of the fetus is defined relative to its position in the maternal pelvis. When the bony fetal presenting part is aligned with the maternal ischial spine, the fetus is 0 station. Proximal to the ischial spines are stations -1 centimeter to -5 centimeters, and distal to the ischial spines is +1 to +5 station.[1] The first stage of labor contains a latent phase and an active phase. During the latent phase, the cervix dilates slowly to approximately 6 centimeters. The latent phase is generally considerably longer and less predictable with regard to the rate of cervical change than is observed in the active phase. A normal latent phase can last up to 20 hours and 14 hours in nulliparous and multiparous women, respectively, without being considered prolonged.[1] Sedation can increase the duration of the latent phase of labor.[7] The cervix changes more rapidly and predictably in the active phase until it reaches 10 centimeters and cervical dilation and effacement are complete. Active labor with more rapid cervical dilation generally starts around 6 centimeters of dilation. During the active phase, the cervix typically dilates at a rate of 1.2 to 1.5 centimeters per hour. Multiparas, or women with a history of prior vaginal delivery, tend to demonstrate more rapid cervical dilation.[1] The absence of cervical change for greater than 4 hours in the presence of adequate contractions or six hours with inadequate contractions is considered the arrest of labor and may warrant clinical intervention.[7]

Active labor with more rapid cervical dilation generally starts around 6 centimeters of dilation. During the active phase, the cervix typically dilates at a rate of 1.2 to 1.5 centimeters per hour. Multiparas, or women with a history of prior vaginal delivery, tend to demonstrate more rapid cervical dilation.[1] The absence of cervical change for greater than 4 hours in the presence of adequate contractions or six hours with inadequate contractions is considered the arrest of labor and may warrant clinical intervention.[7]

Second Stage of Labor

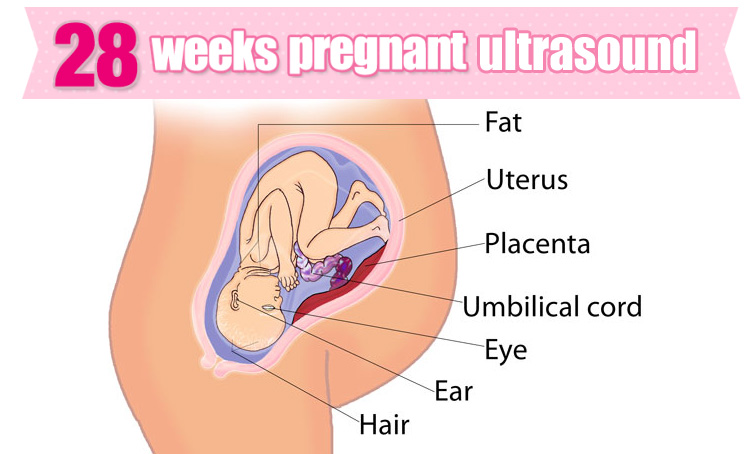

The second stage of labor commences with complete cervical dilation to 10 centimeters and ends with the delivery of the neonate. This was also defined as the pelvic division phase by Friedman. After cervical dilation is complete, the fetus descends into the vaginal canal with or without maternal pushing efforts. The fetus passes through the birth canal via 7 movements known as the cardinal movements. These include engagement, descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension, external rotation, and expulsion. [1] In women who have delivered vaginally previously, whose bodies have acclimated to delivering a fetus, the second stage may only require a brief trial, whereas a longer duration may be required for a nulliparous female. In parturients without neuraxial anesthesia, the second stage of labor typically lasts less than three hours in nulliparous women and less than two hours in multiparous women. In women who receive neuraxial anesthesia, the second stage of labor typically lasts less than four hours in nulliparous women and less than three hours in multiparous women.[1] If the second stage of labor lasts longer than these parameters, then the second stage is considered prolonged. Several elements may influence the duration of the second stage of labor, including fetal factors such as fetal size and position, or maternal factors such as pelvis shape, the magnitude of expulsive efforts, comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes, age, and history of previous deliveries.[8]

[1] In women who have delivered vaginally previously, whose bodies have acclimated to delivering a fetus, the second stage may only require a brief trial, whereas a longer duration may be required for a nulliparous female. In parturients without neuraxial anesthesia, the second stage of labor typically lasts less than three hours in nulliparous women and less than two hours in multiparous women. In women who receive neuraxial anesthesia, the second stage of labor typically lasts less than four hours in nulliparous women and less than three hours in multiparous women.[1] If the second stage of labor lasts longer than these parameters, then the second stage is considered prolonged. Several elements may influence the duration of the second stage of labor, including fetal factors such as fetal size and position, or maternal factors such as pelvis shape, the magnitude of expulsive efforts, comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes, age, and history of previous deliveries.[8]

Third Stage of Labor

The third stage of labor commences when the fetus is delivered and concludes with the delivery of the placenta. Separation of the placenta from the uterine interface is hallmarked by three cardinal signs, including a gush of blood at the vagina, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and a globular shaped uterine fundus on palpation.[1] Spontaneous expulsion of the placenta typically takes between 5 to 30 minutes.[1] A delivery time of greater than 30 minutes is associated with a higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage and may be an indication for manual removal or other intervention.[1] Management of the third stage of labor involves placing traction on the umbilical cord with simultaneous fundal pressure to effect faster placental delivery.

Separation of the placenta from the uterine interface is hallmarked by three cardinal signs, including a gush of blood at the vagina, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and a globular shaped uterine fundus on palpation.[1] Spontaneous expulsion of the placenta typically takes between 5 to 30 minutes.[1] A delivery time of greater than 30 minutes is associated with a higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage and may be an indication for manual removal or other intervention.[1] Management of the third stage of labor involves placing traction on the umbilical cord with simultaneous fundal pressure to effect faster placental delivery.

Function

The function of the stages of labor is to create a universal definition that medical professionals can use to communicate with each other about labor. The stages of labor can be used to help determine where the patient is on the labor spectrum. Clarifying the stages of labor has helped create guidelines, which define normal and abnormal trends in labor. Clinical management also gears toward the various stages of labor.

Clinical management also gears toward the various stages of labor.

Issues of Concern

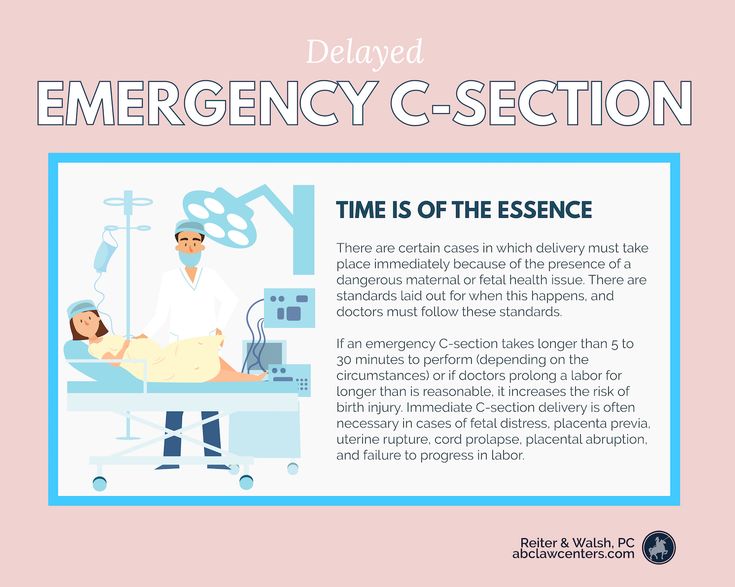

Complications may arise during any of the stages of labor to result in abnormal labor. During the first stage, women may experience the arrest of parturition, necessitating cesarian delivery, which may carry greater maternal or fetal risk. Second stage complications include a variety of complications related to the trauma of the delivery process to either the fetus or the mother. The fetus can suffer acidemia, shoulder dystocia, bony fractures, nerve palsies, scalp hematomas, and anoxic brain injuries. Similarly, the mother can develop a host of traumatic complications ranging from uterine rupture, vaginal laceration, cervical laceration, uterine hemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism, and death. The third stage of labor may encounter complications from hemorrhage, cord avulsion, retained placenta, or incomplete removal of the placenta.[5]

Clinical Significance

Defining the stages of labor with a specific beginning and end has allowed clinicians to study labor trends and to create labor curves. For example, in the 1950s, Dr. Friedman created a graphical representation of the rate of normal labor during latent and active labor using observed clinical data.[9] These, in turn, can be used to determine if a woman is progressing through labor as expected and helping to identify abnormal labor. Friedman observed that labor typically has a sigmoidal shape when measured by cervical dilation over time. During the active phase of labor, cervical dilation occurs at a rate of 1 centimeter or more per hour. If dilation occurs much slower, the patient may be at risk for abnormal labor or arrest of labor.[10]

For example, in the 1950s, Dr. Friedman created a graphical representation of the rate of normal labor during latent and active labor using observed clinical data.[9] These, in turn, can be used to determine if a woman is progressing through labor as expected and helping to identify abnormal labor. Friedman observed that labor typically has a sigmoidal shape when measured by cervical dilation over time. During the active phase of labor, cervical dilation occurs at a rate of 1 centimeter or more per hour. If dilation occurs much slower, the patient may be at risk for abnormal labor or arrest of labor.[10]

If a woman is found not progressing through the first stage of labor as expected, this could lead to the diagnosis of the arrest of dilation or descent, which could result in cesarean delivery. The findings of Dr. Friedman have recently been challenged, and the current consensus is the normal latent phase of labor lasts longer than was previously observed.[8] The criteria for the stages of labor create a universal language that allows healthcare professionals to communicate with one another about patient care accurately. Also, specific interventions are tailored to particular stages of labor to try to create better patient outcomes. For example, active management in the third stage of labor is carried out by placing immediate traction on the umbilical cord and administering intravenous oxytocin, which correlates with a lower risk of postpartum hemorrhage.[11] Clinicians will continue to use the stages of labor to guide labor management and study labor patterns to improve patient care.

Also, specific interventions are tailored to particular stages of labor to try to create better patient outcomes. For example, active management in the third stage of labor is carried out by placing immediate traction on the umbilical cord and administering intravenous oxytocin, which correlates with a lower risk of postpartum hemorrhage.[11] Clinicians will continue to use the stages of labor to guide labor management and study labor patterns to improve patient care.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

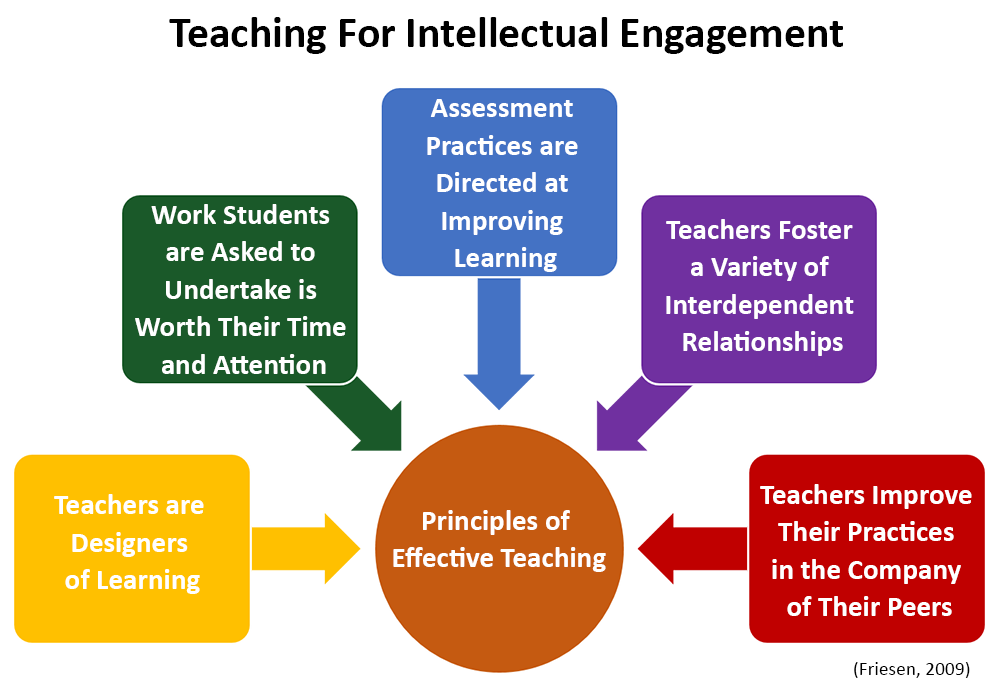

The stages of labor describe a complex physiologic process that starts when labor beings and ends with the delivery of the fetus and placenta. Labor is usually monitored clinically with multiple modalities by an interprofessional team. The process of labor can proceed as typically expected with certain cardinal events and time parameters or can encounter complications and delays, which may require identification and medical intervention.

The role of the interprofessional team in monitoring and caring for women during labor is critically important in keeping women safe and improving outcomes during the labor process.

A wide variety of medical professionals such as nurses, midwives, pharmacists, family physicians, anesthesiologists, and obstetrician/gynecologists may be involved in a woman’s labor process. Close communication is needed between these professionals to create an atmosphere of safety and patient-centered care. Midwives often manage labor and delivery and work closely with physicians when complications arise, requiring physician intervention, such as Caesarian section or operative delivery. Pharmacists ensure that patients receive the proper analgesics, tocolytics, and other medications that may be needed during or following labor. Anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists administer epidurals for analgesia and are available for general endotracheal anesthesia when necessary. Nurses monitor the patient’s vital signs, contractions, cervical exams, pain scores, administer medications, recognize complications, and update the physician or midwife responsible for the patient. Each labor is unique, but an interprofessional approach prenatally and during labor can be used to improve patient outcomes and provide patient-centered care, as each provider class works collaboratively to ensure communication lines remain open between different disciplines on the health care team [Level 5]

A Canadian retrospective cohort study of 1238 women found that an interprofessional team approach to obstetrical care was shown to provide better patient outcomes by decreasing the rate of cesarian sections and length of hospital stays for women. [12] [Level 4]

[12] [Level 4]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Nurses are intimately involved in monitoring and caring for laboring women. Nurses administer and titrate medications during labor, such as oxytocin. Nurses monitor the vital signs, pain scores, and labor progression of women and fetuses closely and are responsible for recognizing and then notifying physicians and midwives when abnormalities arise.

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Liao JB, Buhimschi CS, Norwitz ER. Normal labor: mechanism and duration. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2005 Jun;32(2):145-64, vii. [PubMed: 15899352]

- 2.

van der Ham DP, van Melick MJ, Smits L, Nijhuis JG, Weiner CP, van Beek JH, Mol BW, Willekes C. Methods for the diagnosis of rupture of the fetal membranes in equivocal cases: a systematic review.

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011 Aug;157(2):123-7. [PubMed: 21482018]

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011 Aug;157(2):123-7. [PubMed: 21482018]- 3.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 766 Summary: Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Feb;133(2):406-408. [PubMed: 30681540]

- 4.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 209: Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Mar;133(3):e208-e225. [PubMed: 30801474]

- 5.

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Aug;114(2 Pt 1):386-397. [PubMed: 19623003]

- 6.

Zhang J, Troendle J, Mikolajczyk R, Sundaram R, Beaver J, Fraser W. The natural history of the normal first stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Apr;115(4):705-710. [PubMed: 20308828]

- 7.

Zhang J, Landy HJ, Ware Branch D, Burkman R, Haberman S, Gregory KD, Hatjis CG, Ramirez MM, Bailit JL, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Hibbard JU, Hoffman MK, Kominiarek M, Learman LA, Van Veldhuisen P, Troendle J, Reddy UM.

, Consortium on Safe Labor. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Dec;116(6):1281-1287. [PMC free article: PMC3660040] [PubMed: 21099592]

, Consortium on Safe Labor. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Dec;116(6):1281-1287. [PMC free article: PMC3660040] [PubMed: 21099592]- 8.

Cheng YW, Caughey AB. Defining and Managing Normal and Abnormal Second Stage of Labor. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017 Dec;44(4):547-566. [PubMed: 29078938]

- 9.

Pitkin RM. Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol 1955;6:567-89. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Feb;101(2):216. [PubMed: 12576240]

- 10.

Kilpatrick SJ, Laros RK. Characteristics of normal labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Jul;74(1):85-7. [PubMed: 2733947]

- 11.

Güngördük K, Olgaç Y, Gülseren V, Kocaer M. Active management of the third stage of labor: A brief overview of key issues. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Sep;15(3):188-192. [PMC free article: PMC6127474] [PubMed: 30202630]

- 12.

Harris SJ, Janssen PA, Saxell L, Carty EA, MacRae GS, Petersen KL.

Effect of a collaborative interdisciplinary maternity care program on perinatal outcomes. CMAJ. 2012 Nov 20;184(17):1885-92. [PMC free article: PMC3503901] [PubMed: 22966055]

Effect of a collaborative interdisciplinary maternity care program on perinatal outcomes. CMAJ. 2012 Nov 20;184(17):1885-92. [PMC free article: PMC3503901] [PubMed: 22966055]

Signs, Progression & What To Expect

What to expect during labor and delivery.How does labor work?

As your pregnancy begins to wrap up, your body will prepare for labor and delivery. This is the process through which your baby will be born. Labor is often different for each person. Some have quick labors and some long, difficult labors. Other people may even experience labor that stalls or stops, leading to medical intervention.

Early labor

The average labor lasts 12 to 24 hours for a first birth and is typically shorter (eight to 10 hours) for other births. Throughout this time, you’ll experience three stages of labor. The first stage of labor is usually the longest and it ranges from when you first go into labor until your cervix is open. The beginning of this stage is called early labor. Early labor is described as dilating from 0 to 6 centimeters.

The beginning of this stage is called early labor. Early labor is described as dilating from 0 to 6 centimeters.

Active labor

As you progress and your contractions become stronger, you’ll move into the second part of the first stage of labor called active labor. Active labor is dilating from 6 to 8 centimeters and then transitioning into the second stage as you dilate 8 to 10 centimeters. Your contractions will become even stronger during active labor and your cervix will open up quickly. The second stage of labor is when you push. This is the phase of your labor when you will actually give birth to your baby.

Afterbirth

The third stage is the point when you deliver the placenta. This is also called afterbirth.

During these stages, your body prepares for childbirth by going through dilation and effacement.

- Dilation: This is a process where your cervix stretches and opens to make way for your baby’s birth. Dilation is measured from 1 to 10 centimeters.

Your provider will do a vaginal exam to check how dilated you are throughout your labor. You’ll be 10 centimeters dilated in the second stage of labor for the delivery of your baby.

Your provider will do a vaginal exam to check how dilated you are throughout your labor. You’ll be 10 centimeters dilated in the second stage of labor for the delivery of your baby. - Effacement: The cervix not only stretches during labor but it also becomes thinner. The shortening and thinning of your cervix are measured in percentages. You’ll progress from 0% to 100% effacement during your labor.

Think of your cervix as a round doorway that needs to stretch outward and get thinner before your baby can pass through it. This stretching and thinning are caused by contractions. Contractions can be described in a variety of ways ranging from uncomfortable, period-like cramps to a painful tightening of your abdomen. You might also feel a dull ache in your back and lower abdomen, as well as pressure in your pelvis.

When you have a contraction, it’s actually the muscles of your uterus tightening at regular intervals to dilate and efface (open and thin) your cervix. During contractions, your abdomen becomes hard. Between contractions, your uterus relaxes and your abdomen becomes soft. Even though they can be painful, each contraction helps move you forward through your labor.

During contractions, your abdomen becomes hard. Between contractions, your uterus relaxes and your abdomen becomes soft. Even though they can be painful, each contraction helps move you forward through your labor.

How will I know I’m in labor?

It can be difficult to know when you’re in true labor. First-time parents, in particular, might mistake other symptoms or irregular practice contractions (called Braxton Hicks contractions) for true labor. True labor has a pattern and progresses steadily over time.

When you’re in true labor, you’ll notice a pattern in your contractions. Instead of the irregular Braxton Hicks contractions you might have felt during your pregnancy that showed up and then went away randomly, these contractions will keep coming for an extended period of time. There are three things you’ll want to look for when you are in true labor.

- Frequency: How often are your contractions happening? Keep track of them with a journal or labor app on your phone to make sure they're coming at regular intervals.

- Duration: How long are each of your contractions? As your labor continues, your contractions will last longer and longer. Use a stopwatch, watch a clock or keep the timer on your phone handy so you can record the length of each contraction.

- Intensity: Are your contractions getting stronger? Contractions can get stronger and you might feel them more intensely as you move through the stages of labor. Keep track of how your contractions feel over time.

Are there any signs that I will go into labor soon?

Many women have several pre-labor signs that might hint that labor will start soon. These signs of labor include:

- Backaches.

- Diarrhea.

- Weight loss.

- Nesting (cleaning and organizing your home).

No one knows for sure what causes labor to start, but several hormonal and physical changes may point to the beginning of labor.

What are Braxton Hicks contractions?

Often called practice contractions, Braxton Hicks are irregular contractions that don’t cause cervical change. Think of them as a test run for the real thing. They can start happening at the end of your pregnancy and can startle people into thinking they’re in labor. This is called false labor.

Think of them as a test run for the real thing. They can start happening at the end of your pregnancy and can startle people into thinking they’re in labor. This is called false labor.

A Braxton Hicks contraction will feel like a sudden, sharp tightening of your abdominal muscles. Even though this is very similar to how a contraction feels, Braxton Hicks contractions don’t follow a pattern or progress over time. They may also stop when you lay down or relax. When you start to experience these practice contractions, keep track of them. Writing them down is the best way to tell the difference between true and false labor.

What is lightening?

Lightening is the process where your baby settles or lowers into your pelvis. This can happen a few weeks or a few hours before labor. When this happens, you may experience some increased lower pelvic pressure. Because your uterus rests on your bladder more after lightening, you might also feel the need to urinate more frequently. You might notice that you’re not as short of breath once your baby drops.

You might notice that you’re not as short of breath once your baby drops.

What’s the mucus plug and what does it mean when it falls out?

During pregnancy, a thick piece of mucus called a plug blocks the cervical opening. This plug keeps your uterus closed off from the birth canal and the outside of your body and prevents bacteria from traveling into your uterus. When your cervix begins to soften, thin, and open, the mucus is expelled into your vagina. Not every mucus plug will look the same. Possible colors of the mucus plug can include:

- Clear.

- Pink.

- Slightly bloody.

Labor could start shortly after you lose your mucus plug or it could begin several weeks later.

How do I time my contractions?

Once you’re in labor, it’s important to keep track of your contractions. Your healthcare provider will need to know how long your contractions are lasting (duration), how often they’re happening (frequency) and how intense they are. When you’re timing your contractions, you will want to have a way to record each one – pen and paper or through an app on your phone – and a timer or clock. Make sure you keep track of each contraction from start to end, as well as the time between each contraction. This second measurement will help your provider know the frequency of your contractions.

When you’re timing your contractions, you will want to have a way to record each one – pen and paper or through an app on your phone – and a timer or clock. Make sure you keep track of each contraction from start to end, as well as the time between each contraction. This second measurement will help your provider know the frequency of your contractions.

It can be difficult to record the intensity of your contractions. This can really vary from person to person. Often, an easy way to keep track of the intensity of your contractions is to record when you cannot walk, talk or laugh during contractions.

Is there anything I can do to cope with contractions?

As you approach the end of your pregnancy, it’s a good idea to talk to your healthcare provider about different ways to deal with pain and discomfort during labor. There are several options your provider will discuss with you to relieve pain.

There are also ways to deal with the discomforts of labor at home or without medication, including:

- Distract yourself by taking a walk, going shopping or watching a movie.

- Soak in a warm tub or take a warm shower. Make sure to ask your healthcare provider if you should take a tub bath if your bag of water has broken.

- Sit on a birth ball.

- Listen to music.

- Dim the lights.

- Use aromatherapy.

- Get a massage.

- Stay in an upright position. This can help with the descent and rotation of your baby.

- Try to sleep if it’s evening. You’ll want to store up your energy before active labor and delivery.

How will I know when my water breaks?

You may be familiar with the common phrase “my water broke.” This is actually the rupturing of your amniotic membrane. During pregnancy, your baby is inside a fluid-filled sac, also called your bag of water. When this membrane breaks, you might feel a sudden gush or trickle of fluid. Like many parts of labor and childbirth, this experience can be different for each person. The fluid is usually odorless and may look clear or straw-colored.

Unlike urine leakage that some pregnant women experience, this won’t stop. The amniotic fluid will often continue to leak.

The amniotic fluid will often continue to leak.

If your water breaks, call your healthcare provider. Let your provider know what time your water broke, the amount (trickle or gush), the color of the fluid and the odor. Don't use tampons if your water has broken. Your labor might start right after your water breaks. Some women are already in labor when their water breaks while others don’t experience the first stage of labor for a while after their water breaks.

When should I call my healthcare provider or go to the hospital?

If you ever have any questions, it’s always a good idea to call your healthcare provider. Your provider can answer any questions you have about true labor versus false labor and discuss how you’re feeling. When you start to notice that you’re having regular contractions, call your provider to talk about when you should go to the hospital. Some women are able to stay home throughout early labor, while others may need to come in sooner.

You should also call your healthcare provider if you:

- Think your water has broken.

This could be a sudden gush of fluid or a trickle of fluid that leaks steadily.

This could be a sudden gush of fluid or a trickle of fluid that leaks steadily. - Are bleeding (more than spotting).

- Experience contractions that are very uncomfortable and have been coming every five minutes, lasting for one minute and have been like this for one hour.

What happens when I get to the hospital?

When you get to the hospital, you will check in at the labor and delivery desk. Most people will be seen in a triage room first. This is part of the admission process. It’s usually recommended that you only bring one person with you to the triage room.

From the triage room, you will be taken to the labor, delivery and recovery (LDR) room. You’ll be asked to wear a hospital gown. Your pulse, blood pressure and temperature will be checked. An external fetal monitor will be placed on your abdomen for a short time to check for uterine contractions and measure your baby’s heart rate. Your healthcare provider will also examine your cervix to see how far labor has progressed. An intravenous (IV) line might be placed into a vein in your arm to deliver fluids and medications.

An intravenous (IV) line might be placed into a vein in your arm to deliver fluids and medications.

What does it mean to have labor induced?

Labor doesn’t always start naturally or progress as it should. In these cases, your provider might talk to you about inducing labor. This is a medical procedure where labor is started by your healthcare provider. This could happen if you:

- Are past your due date.

- Have health complications like high blood pressure, preeclampsia, infection or diabetes.

- Had your water break but labor didn’t start.

- Have low levels of amniotic fluid.

Your labor can be advanced or induced in several ways. Your provider will advise you about the best and safest option depending on your health. Inducing labor can be done by using:

- Medications (oxytocin) given through an IV (directly into your vein).

- Breaking your amniotic sac (water).

- Separating the amniotic membrane (the sac of fluid the baby is inside within your uterus) from your uterine wall.

This is also called sweeping the membrane.

This is also called sweeping the membrane. - Softening your cervix and encouraging it to open with a medication that can be placed directly in your vagina.

Labor induction can take longer than spontaneous labor because the cervical ripening process takes time.

What are the different types of delivery?

There are two main types of delivery: vaginal and cesarean section (C-section). During vaginal birth, your baby will pass naturally through the birth canal. A C-section is a surgical procedure where your provider makes an incision (cut) in your abdomen and delivers the baby in an operating room. Vaginal delivery is the most common type of birth. However, sometimes you might need a C-section for a variety of reasons, including:

- If your baby is not in the head-down position.

- If your baby is too large to naturally pass through your pelvis.

- If your baby is in distress.

- If the placenta blocks your cervix (a condition called placenta previa).

- If you have health issues or complications that make a C-section the safest option.

- If there’s an emergency situation that requires your baby to be delivered quickly.

In many cases, a cesarean delivery is not determined until after labor begins.

How long will I be in the hospital?

The length of your hospital stay can depend on the hospital where you deliver your baby and the type of delivery you have. Typically, you will stay in the hospital longer if you have a C-section delivery because it's a surgical procedure. You may also need to stay in the hospital for a longer period of time if you experience any complications or health issues during your delivery.

A note from Cleveland Clinic:

You're bound to a lot of feelings as you prepare to deliver your baby. It's normal to feel both excited and nervous. Discussing the signs and symptoms with your healthcare provider can help you know what to expect. Your partner and healthcare team are here to support you and will help you remain as comfortable as possible through the delivery process.

Training center "PROGRESS"

STD Petrovich LLC

Federal State Unitary Enterprise Research Institute of Industrial and Marine Medicine of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency

JSC Russian Post

Municipal state institution "Center for ensuring the functioning of municipal institutions"

St. Petersburg State Budgetary Institution "Directorate for the management of the hotel and restaurant complex"

St. Petersburg named after V.B. Bobkov branch of the state state educational institution of higher education "Russian Customs Academy"

Interregional branch of FKU "TsOKR" in St. Petersburg

Petersburg

FKU "SZTsMTO Rosgvardia"

FKU "SZOUMTS of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia"

Research Institute "Center of command devices"

St. Petersburg State Institution "Research and Development Center for the General Plan of St. Petersburg"

GKU "AVS"

Russian State Institute of Performing Arts (RGISI)

Boarding house "White Sun" of the Federal Customs Service of Russia

LOGKU Lenobles

GBOU "Baltic Coast"

GBU DO "Youth Creative Forum Kitezh Plus"

SPB GKU "MFC"

St. Petersburg State Budgetary Institution "CCKTR"

Petersburg State Budgetary Institution "CCKTR"

NRC "Kurchatov Institute" - PNPI

St. Petersburg State Budgetary Institution "Pension "Zarya"

Housing Committee

SPb GKU "Organizer of Transportation"

RGPU them. A. I. Herzen

Legislative Assembly of St. Petersburg

Children's Clinical Hospital

Toksovo Interdistrict Hospital

Committee on Labor and Employment of the Population of St. Petersburg

Petersburg

St. Petersburg State Unitary Enterprise "Gorelectrotrans"

St. Petersburg Customs

Committee for Physical Culture and Sports

EKS - branch of CEKTU St. Petersburg

LLC Unicosmetics

Sevenergostroy

OOO STIS

General contracting company STEP

Committee for Science and Higher Education

Ministry of Health and Social Development of Russia

Rolf

VIP Pulkovo

Industrial Safety North-West

ELCO

University of Film and Television

Sevzammorgidrostroy

soviet star

BO Old Mill

Baltic house

northern dawn

UM 260

OOO Armatek

OOO Kurant

Federal Service for Environmental Technological and Nuclear Supervision

Department of Private Security

Saint Petersburg University of Engineering and Economics

Enekos

Dagvino

BFA Development

Federal Center of Heart, Blood and Endocrinology. Almazova

Almazova

Kelly

Administration of Perm

Administration of Norilsk

Saint Petersburg State University

Petmol

Valio

Danone Russia

GK EFESk

TsPKO them. Kirov

St. Petersburg State Unitary Enterprise Passazhiravtotrans

Petersburg State Unitary Enterprise Passazhiravtotrans

OJSC Plant of Radio Equipment

St. Petersburg Circus

Goznak

Megaphone

Heineken

Capital Repair Fund

Russian Railways

Primorsky commercial port

FBUZ "Center for Hygiene and Epidemiology in St. Petersburg"

Petersburg"

SPb GBU Mostotrest

Gazprom Neft

Russian telephone company

Seaport of St. Petersburg

Petroholod

Kirov Plant

Petersburg Metro

Eco Service

british american tobacco

Baltic

Holding company "Adamant"

Children's psychiatry. S.S. Mnukhin

S.S. Mnukhin

Accounting Center

Search and Rescue Service of St. Petersburg

Housing agency of the Nevsky district

Housing agency of Pushkinsky district

Hospice №4

Lomonosov City House of Culture

Maternity hospital №10

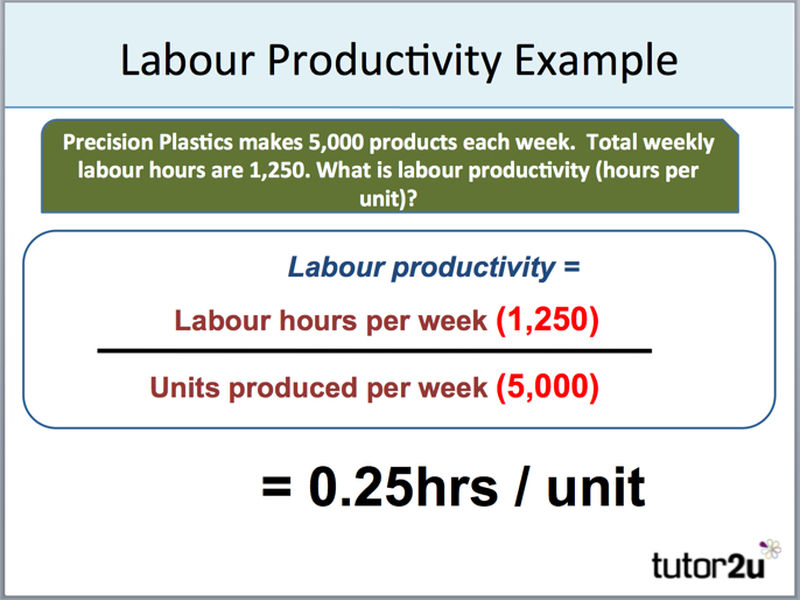

Online course Labor rationing. Management of factors affecting labor productivity

PR. Press Service

Press Service

Hotels. Restaurants. Catering

Engineering networks: construction and repair

The medicine

Organization of activities of cultural institutions

Organization of transportation. Transport

Office. Office work. Archives

AHHO. Office

Office

Occupational Safety and Health. Safety

Right. FEA

Production

Social protection

Trainings

Services

Energy. energy saving

Industry

Lean

State defense order

Procurement. Supply. Stock

Supply. Stock

Import substitution

Intellectual property

Light industry

Materials, technologies, equipment

food industry

Standardization. Metrology

Transport

Transport logistics

Railway transportation

Motor transport

Innovation management

Quality control

Manufacturing control

Safety

Control systems security

Information Security

Personnel risks

Comprehensive Security

Occupational Safety and Health

Fire safety

Industrial Safety

Environmental Safety

Economic and legal

Energy

Legal regulation in the energy sector

Economy and investment in energy

Operation of fuel and energy facilities

energy saving

Construction and engineering networks

road construction

Engineering networks: design and construction

Low-current system

Gas supply

Water supply and sanitation

Heat supply and ventilation

Power supply

Legal regulation of construction activities

Design. research

research

Estimated business

Building materials and technologies

Construction: organization and management

Construction economics

housing and communal services. Municipal economy

Housing and communal services. Urban economy

Repair and operation of buildings and structures

Real estate

Management and operation of real estate

Ecology and land use

Subsoil use. Land law, cadastral activities

Land law, cadastral activities

Ecology

Human Resources

HR technologies. Personnel Management

Labor law. HR records management

Office services

Archives

office work

Working with a leader

Management

General management

Special management

Sports management

Management of administrative and economic activities

Marketing.

PR

PR Marketing. Sales

Advertising. PR

Economics. Finance. Accounting

Accounting

budget accounting

Industry accounting

Accounting in commercial organizations

Taxation

Labor rationing

Pay and motivation

Financial management. Economy

Economy

Law. FEA

Foreign economic activity

Civil and procedural law

Contract work

Other branches of law

Corporate law

Right by type of activity

Information technology

Process automation, application software

IT infrastructure management

Communication

Design and construction of communication facilities

Legal support and FCD

State and municipal administration

Budget financing

Non-Profit Organizations

Organization of activities of institutions and authorities

Social protection

Organization of work of bodies of social protection of the population

Social service technologies

Medicine

Health Organization

Law in healthcare

Pharmacy

Economics and finance in healthcare

Veterinary

Veterinary

Education

Higher education

Additional professional education

Secondary general and special (correctional) education

Secondary vocational education

Culture

Museums.