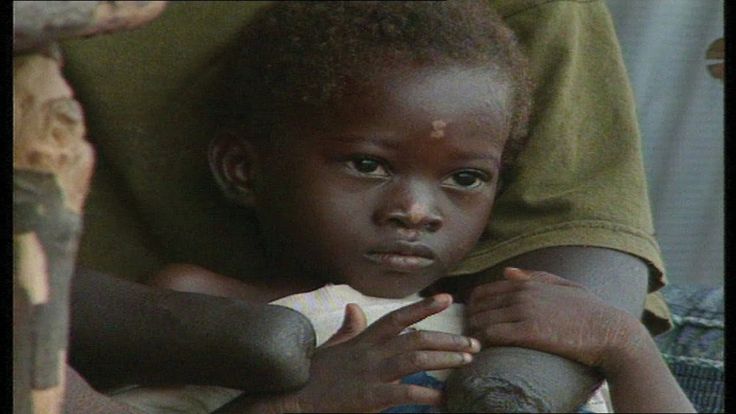

How does being a child soldier affect them

Child soldiers: What you need to know

The United Nations reports that 250 million girls and boys live in areas of the world affected by armed conflict.

Despite being least responsible for the outbreak of violent conflict, children are disproportionately at risk of being affected by the violence and exploitation that occurs in war zones.

Recognising the devastating impact of conflict on children, the UN defined six grave violations of children’s rights – including the recruitment and use of children.

In 2002, the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict (OPAC) came into force, defining the recruitment and use of children in conflict as a violation international law.

While there can appear to be an element of “choice” involved in a child’s actions that result in joining an armed group, this choice is almost always a product of coercion, lack of safe alternatives, and out of fear created by the conflict itself.

When trying to end the scourge of child soldiers, it's necessary to work not only with armed forced and groups to end their recruitment practices, but also tackle the root causes and factors driving these push factors

Former child soldier Mary sews her way to healing and recovery

Today, 170 States have signed and ratified the OPAC. Despite this, the UN verified in its most recent report that 8,521 children were recruited and used in conflicts around the world. Some child soldiers were as young as six years old.

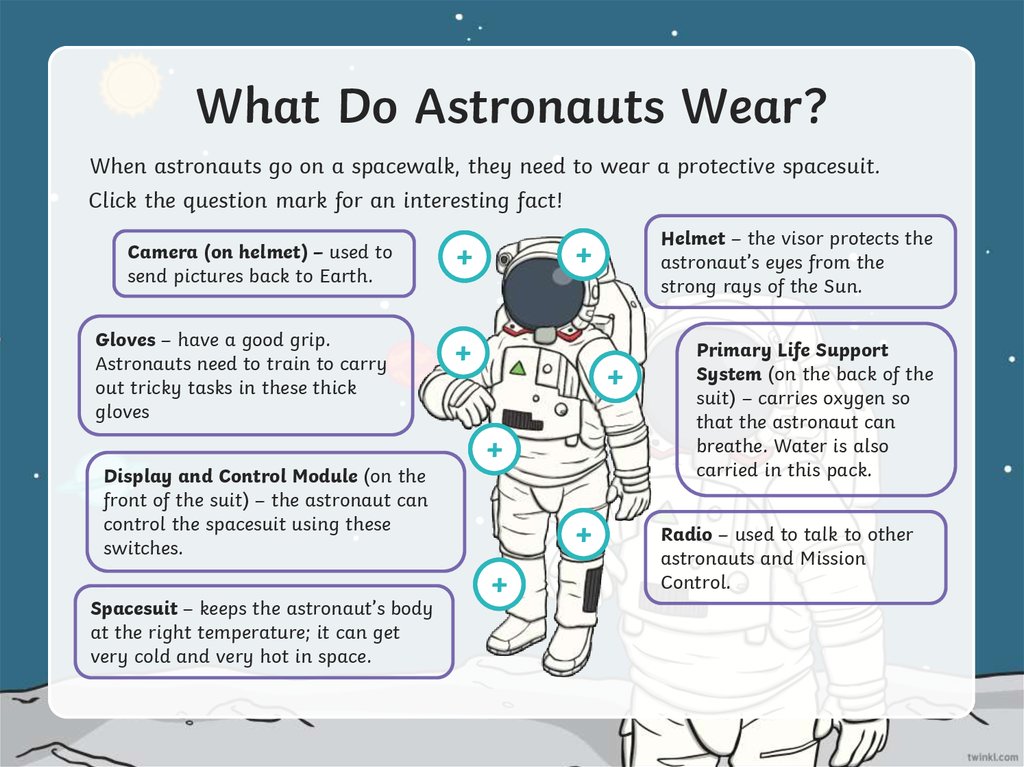

Children can become involved in armed conflicts in direct combat roles, but also in supporting roles – being forced or coerced to become cooks, cleaners, porters, intelligence gatherers and spies, wives, sex slaves, or used in acts of terror. Regardless of their role, the experience for girls and boys is devastating.

While many children are still forcibly recruited and used by armed forces or groups, research has found that socio-economic and circumstantial factors can push boys and girls into joining an armed group, left with no choice.

Our research found these coercive "push" factors are most often related to the sense of safety or need for protection perceived by a child and his or her family, extreme poverty, hunger, lack of access to education, and lack of hope for the future – particularly in protracted conflicts.

As the world looks to end and prevent the use of child soldiers, it is crucial to address all the factors – including those that push children into armed groups.

Strengthening the protective environment for children in fragile and conflict contexts and ensuring adequate resourcing of child reintegration programmes are both key factors to ending the recruitment and use of children.

Read our full policy recommendations here.

Jacob has been haunted by his time as a child soldier

1. What is a child soldier?

According to the Paris Principles on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (2007), a child associated with an armed force (State military or security force) or armed group (non-State actors with arms engaged in conflict) refers to any person below 18 years of age who is, or who has been, recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including, but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, spies or for sexual purposes.

2. How are child soldiers recruited?

Although child soldiers are often forcefully recruited, in a number of armed conflicts it is common for boys and girls to be "pushed" to join an armed force or group, out of fear, coerced, or when left with few other choices.

While there can appear to be an element of “choice” involved in a child’s actions that result in joining an armed group, this choice is almost always a product of coercion, lack of safe alternatives, and out of fear created by the conflict itself.

When trying to end the scourge of child soldiers, it's necessary to work not only with armed forced and groups to end their recruitment practices, but also tackle the root causes and factors driving these push factors.

These factors can include:

Ongoing insecurity and displacement

During times of protracted violence, when families are internally displaced or have to cross borders as refugees, communities are attacked, destroyed or occupied, or as families are internally displaced, their lives become chaotic and disruptive.

This chaos can result in separation between family members, including children from their parents.

The delicate networks that once offered protection and support to families are often irreparably damaged.

This separation leaves children without any means of safety or security, so they choose to become child soldiers as a form of protection.

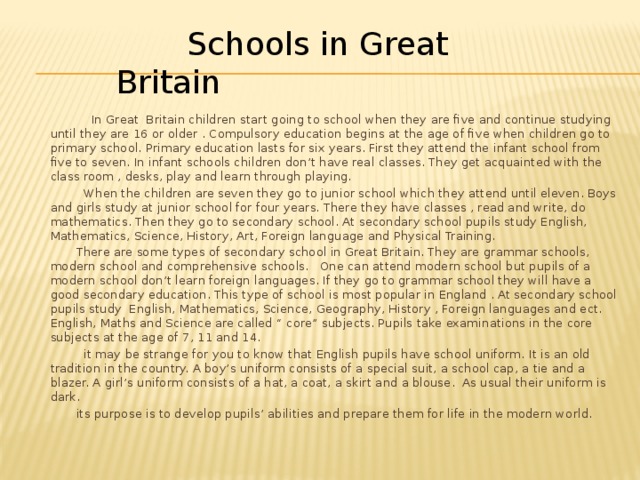

Lack of educational and employment opportunities

In situations areas of armed conflict, education facilities and personnel routinely face attack. Schools often face interruptions or close entirely.

Where families are displaced by conflict, access to education may be even more limited or non-existent.

We commissioned interviews with children affected by armed conflict, and found that when girls and boys can no longer safely access learning, they can begin to feel there is no hope for a job opportunity when they are older or for the future.

A boy in the farm. Child soldiers can be boys or girls.

Poverty, lack of basic necessities and economic factors

For child soldiers, personal financial or familial economic situations rank high as a reason to join. When food and other resources become scarce, the alluring promise of barracks that offer a warm bed and readily available food is difficult to resist.

Conflict can destroy local economies and livelihoods. When families suffer loss of income, the pressure to survive can push parents and caregivers to urge their children to join an armed group – as a hope for the child to be fed by the group or earn an income to contribute to the family.

In some contexts, bride price arrangements with armed groups can be a driving factor for girls’ recruitment, as the family seeks a source of income to survive.

Poor sense of belonging or lack of familial relationships

In times of uncertainty or displacement due to armed conflict, children often leave school, their homes, villages and even countries. These circumstances can lead to a sense of isolation.

These circumstances can lead to a sense of isolation.

When this happens, children may experience a loss of personal identity because a child’s sense of self is directly connected with his or her social surroundings. Joining an armed group and becoming a child soldier provides a sense of identity in that they now belong to a community, despite the level of risk and violence a child often knows they will experience.

Community and family expectations

In situations of armed conflict, particularly at the local level communities can feel the need to protect themselves because of the mere presence of the armed force/group, or because the armed force/group may stand for a belief that is shared and supported by that community.

Community members often feel pressure, or may even want, to play their part. As a result, elders, leaders, families or parents can pressure children to join an armed group – to gain protection, or to support a cause.

As well, other family members may already be involved in a conflict situation and children will recognise this as an opportunity for deeper connection.

3. How many child soldiers are there?

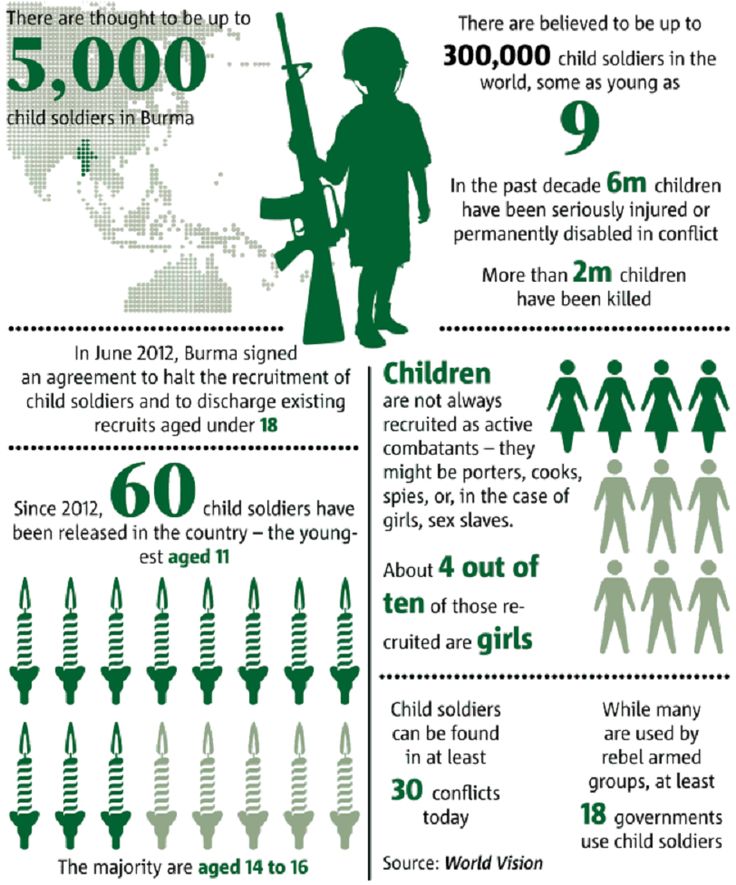

Although there are tens of thousands of boys and girls who have been recruited as child soldiers, statistics are difficult to come by. The exact number is unknown as most data dates back nearly two decades. However, we do know that:

- In 2020, the United Nations Secretary General reported that 8,521 children, some as young as six years old, had been recruited as child soldiers in the previous year.

4. What are the effects of being a child soldier?

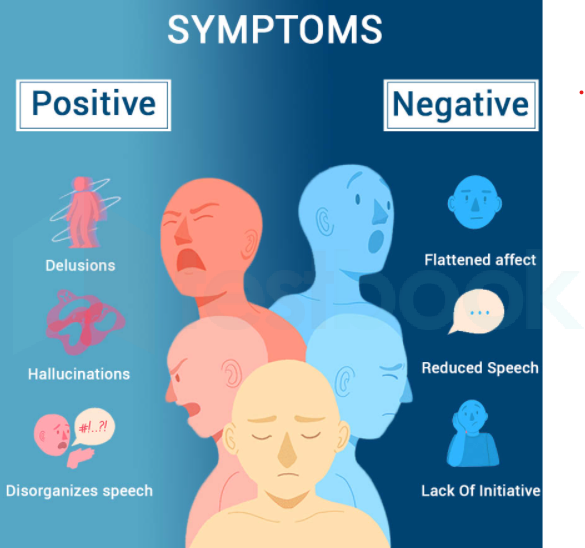

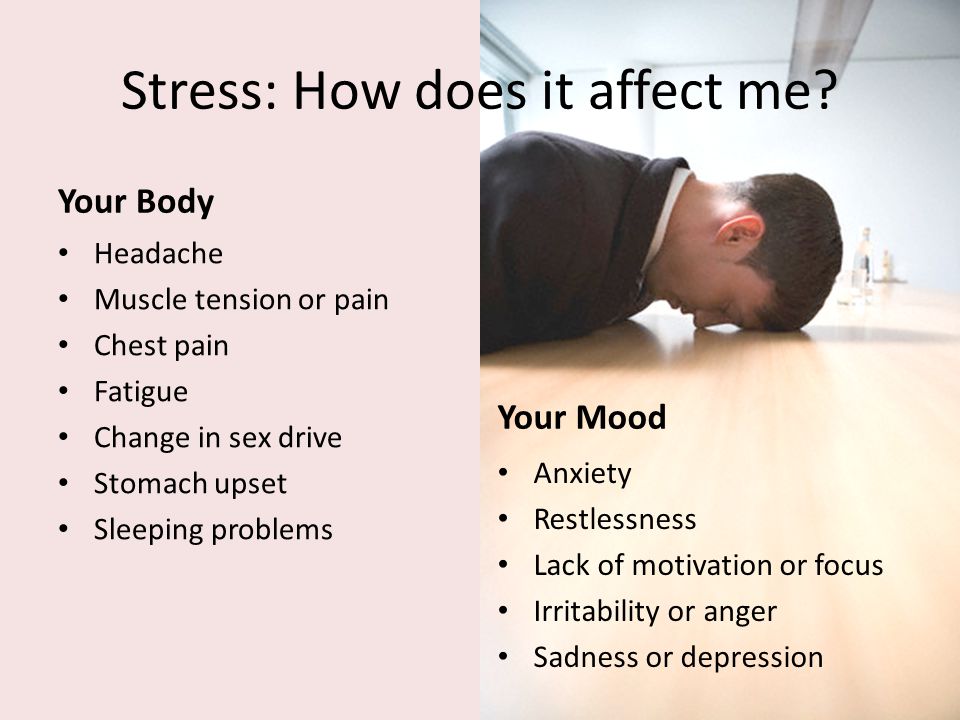

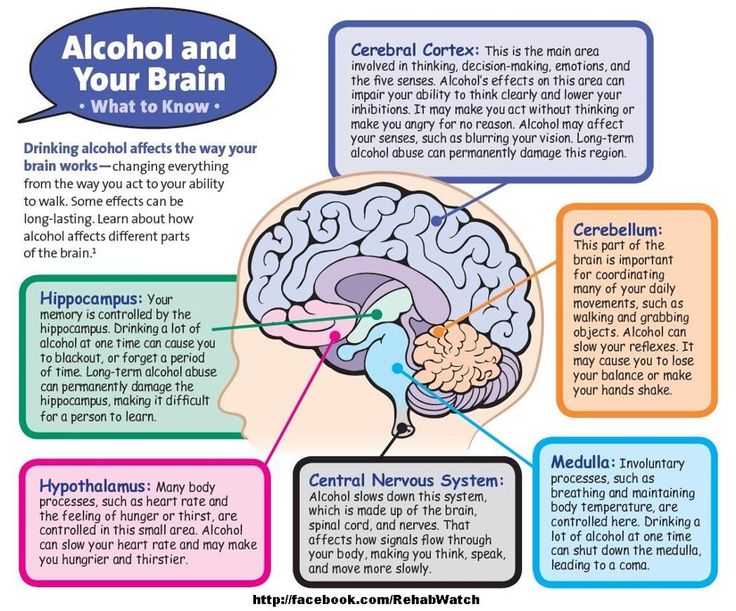

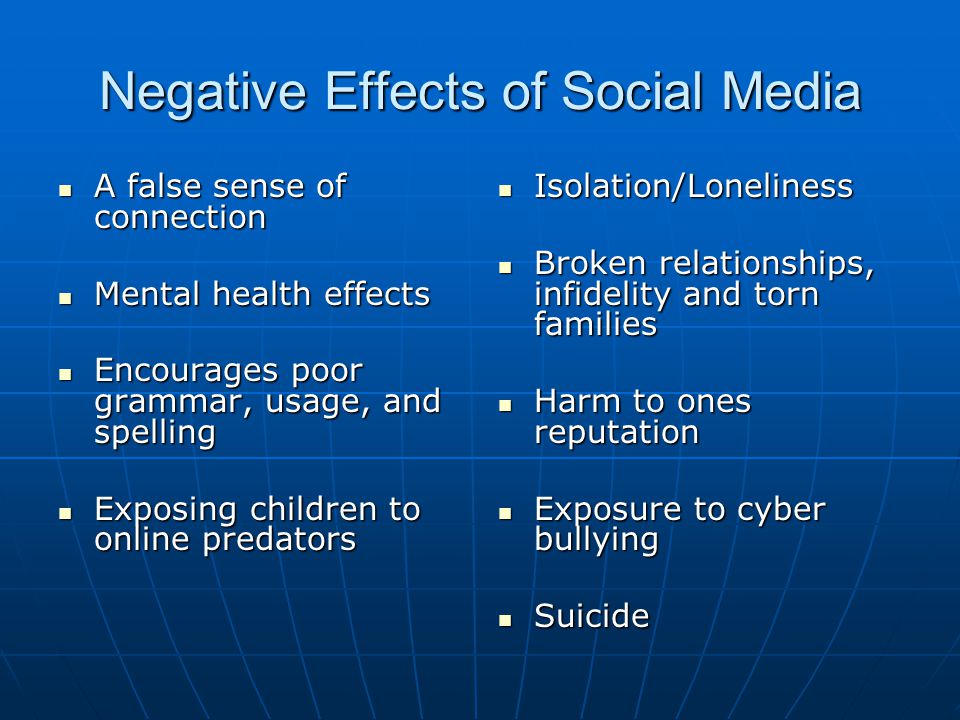

While the physical effects of being a child soldier are varied, the horrors of armed conflict leave long-lasting psychological, sociological and emotional effects on girls and boys.

As a child soldier, girls and boys will be forced to take actions and experience things in a way that denies their childhood and forces adulthood – actions and experiences that can lead psychological trauma for any individual, including adults.

Children will often require substantial mental health and psychosocial support upon exiting an armed force or group, due to the violence they may participate in or witness, directly or indirectly.

Child soldiers can be ostracised by their parents, caregivers, families and communities, depending on the situation of their recruitment and their actions during the conflict.

Rose spent six months in an armed group’s camp in the bush.

It is common to experience extreme forms of stigma that cut these children off from reuniting with their families and reintegrating back into society later.

Girls will almost always experience some form of sexual or gender-based violence, and can face the "double" stigma as a child soldier and survivor.

These effects – physical and mental – and the barriers to services and support that stigma can create, can be devastating and lifelong without intervention or care.

6. What is World Vision doing about child soldiers?

At World Vision, we believe that all children should have the opportunity to experience life in all its fullness.

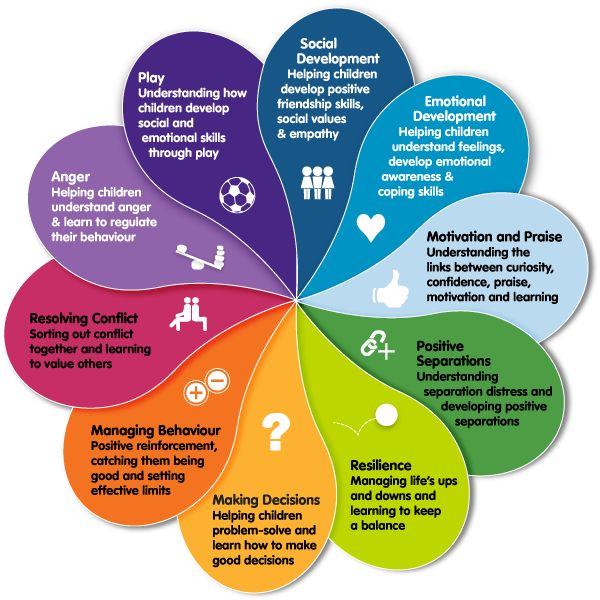

Our strategies to end the recruitment and use of children by armed forces and armed groups are most effective when they are part of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach focused on the protection of the safety and rights of the child.

World Vision programming focuses on prevention by addressing the primary drivers of recruitment and strengthening the protective environment around children.

By doing so, children are less susceptible to not only recruitment, but also other forms of violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation. We offer reintegration programming to support former child soldiers, in line with our general child protection approach.

Former child soldiers in Kasais, DRC.

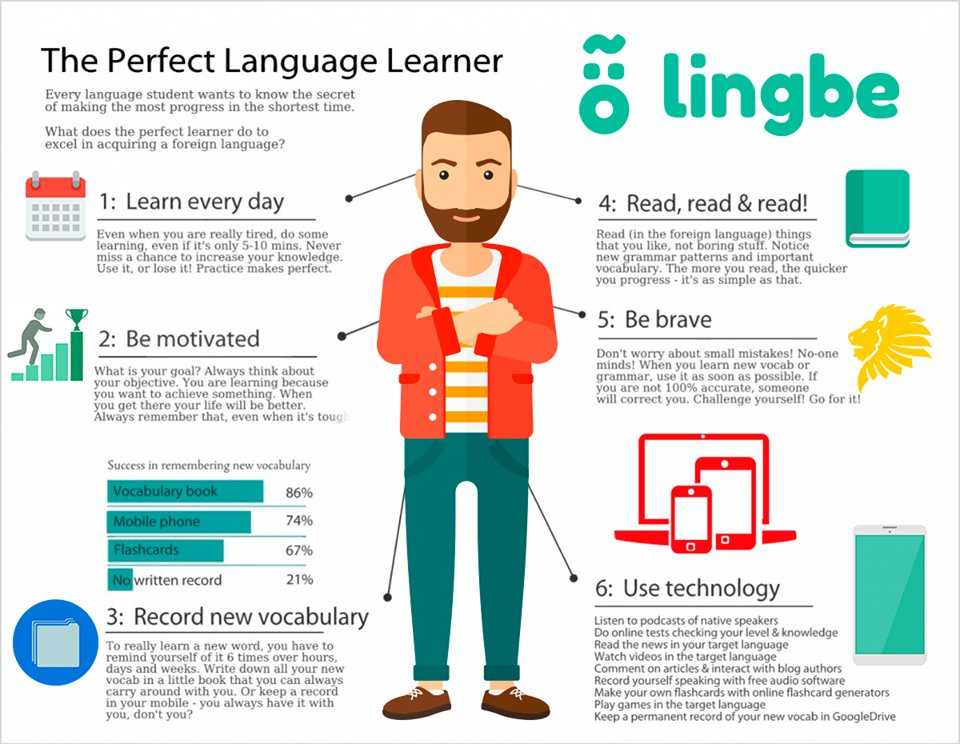

Prevention

We work to prevent children from being recruited into armed forces by strengthening child protection systems, promoting peacebuilding and increasing access to education and livelihood opportunities for entire communities. We take a holistic, rights-based systems approach, addressing the root causes that can contribute to recruitment and use.

We accomplish this through a variety of approaches, including:

- Prioritising Child Protection in humanitarian response, investing in community-based child protection systems that empower community and faith leaders, families, parents and children to monitor, report and refer child protection issues and concerns, and working to ensure comprehensive child protection services are available at local level to respond when children experience risks or forms of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation.

- Educating and empowering girls and boys as powerful agents of change, by providing opportunities for children to increase their decision-making and coping skills, and by promoting peace and social cohesion.

- Strengthening families and caregivers to be the first line of protection and care for children by growing social support networks, and linking them to humanitarian assistance, including food and economic support, and services and systems designed to help families cope in situations of conflict and crisis.

- Partnering with communities to address the root causes of violence against children, including inequality, inadequate social protection systems, lack of economic opportunity, conflict and instability, and harmful attitudes, beliefs and practices that tolerate and spread violence.

Reintegration

The reintegration of children formerly associated with armed forces or armed groups into their families and communities is a crucial step for the well-being of former child soldiers and help prevent re-recruitment.

Some examples of World Vision’s international programming include:

- In South Sudan, World Vision supported over 700 girls and boys to reunite with their families and reintegrate into their communities, providing case management services through qualified social workers, tailored counselling and psychosocial support for child survivors of sexual violence, and supporting their re-entry to primary and secondary education.

Older children were also supported with vocational training to help open doors for the future.

Older children were also supported with vocational training to help open doors for the future. - In Central African Republic, World Vision has connected with peer NGOs, academia and the private sector in a ground-breaking partnership to protect children from the worst forms of labour, including child recruitment and use, supporting local communities to advocate and act to create change.

- In the Democratic Republic of Congo, through the Rebound Project children were supported to reintegrate into community life through the provision of psychosocial support, life skills classes and basic vocational training. At the end of the programme, participants were provided with small grants to start businesses.

How can I help?

While solutions are complex, making a difference is not.

Help advocate for change!

Check if your country has signed and ratified the OPAC and the Paris Principles. Urge your government to take actions to implement this important international agreement.

Urge your government to take actions to implement this important international agreement.

You can also support vulnerable children and their families through our Childhood Rescue initiative.

#ChildSoldiers #ChildProtection #ChildSponsorship

Your donation will help provide life-saving essentials and support to children and families under the threat of abuse and exploitation in the world's most dangerous places.

Find out more about Childhood Rescue here.

The effects of being a child soldier can last a lifetime - News

It’s almost impossible to know the exact figure but it’s estimated there are tens of thousands of children in armed groups around the world.

The UN defines child soldiers as 'children associated with armed forces and groups', or 'CAAFAG' for short.

Not all children have armed roles in these groups, so referring them as 'child soldiers' isn't always accurate:

"A child associated with an armed force or armed group refers to any person below 18 years of age who is, or who has been, recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys and girls, used as fighters, cooks, porters, spies or for sexual purposes."

Some children are abducted by armed groups, but some are lured in by promises of education, security, money and status, and others are indoctrinated or forced.

Most people think that children are only exploited by rebel militias—they are often also recruited by state armed forces.

In reality the risks to children in armed groups is huge, and the after-effects can last a lifetime.

Even if children are released or escape, they may find their families have been killed in conflict—or sometimes the children are rejected by their own communities, especially girls who have had babies with soldiers.

Given the increase of children associated with armed groups and forces in the latest warfare trends, War Child UK has decided to deepen the knowledge around root causes and programming that could prevent the recruitment and support reintegration of children back into communities.

What we're doing

We help reunite children with their families.

We are committed to helping release children from armed groups and supporting them to go back to their families, schools and communities.

Children need safety and appropriate care while their families are being traced or a long-term solution found. Otherwise there’s a serious risk of abduction or re-recruitment.

In the Central African Republic we’re supporting children who have been released from armed groups by finding interim foster carers while their families are being traced.

The children are encouraged to participate in psychosocial support, such as group activities with other boys or girls who have been in armed groups. They can share experiences and develop life-skills, such as conflict resolution, positive decision-making and planning for a positive future. Children who need more in-depth psychological support are referred to specialist services.

Education and training is key so that children have a chance at a future.

School-age children are helped to return to formal education, while older children are given vocational or work-skills training.

We work closely with community-based child protection groups who often see the challenges on the ground first-hand.

Spaces to play, communicate, and to make friends allow children to build bonds with others and recover.

This collaboration can help reduce stigma and rejection of the children by their community.

They can share experiences and develop life-skills, such as conflict resolution, positive decision-making and planning for a positive future. Children who need more in-depth psychological support are referred to specialist services.

Education and training is key so that children have a chance at a future.

School-age children are helped to return to formal education, while older children are given vocational or work-skills training.

We work closely with community-based child protection groups who often see the challenges on the ground first-hand.

Spaces to play, communicate, and to make friends allow children to build bonds with others and recover.

This collaboration can help reduce stigma and rejection of the children by their community.

Disarmament, Demobilisation, and Reintegration (DDR) is the main framework aimed at helping child soldiers safely leave armed groups.

The reintegration process, which War Child UK focuses on, helps children get access to social and economic opportunities to provide them with more prospects for their future.

But the DDR process is not perfect. There is no one-size-fits-all answer.

Children have different experiences: their friends and family may be a part of the group, or they may have no stable family environment to reconnect with.

Support from parents and the feeling of facing challenges together, as a family, can be effective in preventing children from joining an armed group.

But some children may not have any family.

The little support present at a community level is vital in providing guidance, activities, and opportunities to prevent further recruitment.

Without a programme that can consider all of these aspects the effects of the horrifying things these children have experienced can last a lifetime.

War and children are seemingly incompatible concepts...

Time is rapidly moving forward. The Great Patriotic War has become history, and this year marks the 70th anniversary of its end. Over the years, several generations have grown up who have not heard the thunder of guns and bomb explosions.

Over the years, several generations have grown up who have not heard the thunder of guns and bomb explosions.

But the war has not been erased from people's memory. Then it was unbearably difficult for everyone - both the old and the young, and the soldiers who fought at the front, and their loved ones. But the children suffered the most. They suffered from hunger and cold, from the inability to return to childhood, from the sheer hell of bombings and the terrible silence of orphanhood...

Time is rapidly moving forward. The Great Patriotic War has become history, and this year marks the 70th anniversary of its end. Over the years, several generations have grown up who have not heard the thunder of guns and bomb explosions.

But the war has not been erased from people's memory. Then it was unbearably difficult for everyone - both the old and the young, and the soldiers who fought at the front, and their loved ones. But the children suffered the most. They suffered from hunger and cold, from the inability to return to childhood, from the sheer hell of bombings and the terrible silence of orphanhood. ..

..

In 1941-1942, the number of young people in defense enterprises increased dramatically. If in 1940 the proportion of teenagers was six percent, then in 1942 it was three times more, and in heavy industry almost half of the workers were minors.

On June 27, 1941, the Pravda newspaper reported that about 2,000 Moscow schoolchildren came to industrial enterprises to replace those who had gone to the front. In early July, more than 1.5 thousand schoolchildren of Tomsk stood up for machine tools instead of those who went to the active army. December 19For 41 years, schoolchildren from the city of Gorky made a commitment to help light industry enterprises without interrupting their studies. After lessons, they worked at clothing factories, shoe shops, took home orders and made spoons, mittens, socks, scarves, balaclavas, and sewed uniforms.

What kind of military professions did the little soldiers of the Great Patriotic War master! From a trench postman on the front line to a pilot. Children, like adults, did everything in the name of Victory. Documentary evidence reflects the best qualities of the younger generation, reveals its aspirations and desires to be in no way inferior to adults, grandfathers, fathers, mothers, older brothers and sisters in the fight against fascism both at the front and in the rear.

Children, like adults, did everything in the name of Victory. Documentary evidence reflects the best qualities of the younger generation, reveals its aspirations and desires to be in no way inferior to adults, grandfathers, fathers, mothers, older brothers and sisters in the fight against fascism both at the front and in the rear.

There couldn't be many fighting guys. War is not childish. But even those children who had to go through the roads of the war inscribed their glorious page in the military chronicle. It turns out that even at the age of ten you can endure all the horrors of torture in the Gestapo dungeon and not give out the location of the partisan detachment. Or sleep after a shift at the lathe to save time on the way from home to the factory.

There is a saying: “There are no children in war”. This is true, since the convergence of these concepts themselves is unnatural. Those who got into the war had to part with their childhood.

Each person keeps in memory some moment of his life, which seems to him a second birth, a turning point in his entire future destiny. It is this memory that the war lives in the soul of everyone who survived it.

It is this memory that the war lives in the soul of everyone who survived it.

In our time, with talk about children's rights and the adoption of international conventions, childhood is practically deprived of the status of inviolability. Children are increasingly drawn into military conflicts, become victims or accomplices of heinous crimes. In Sarajevo, more than half of the children were injured, in Angola, 67 percent of the children witnessed torture, beatings and injuries. In Rwanda, almost all children were orphaned, 16 percent of them survived hiding under the corpses of their loved ones. After the massacre of the Tutsi people in Rwanda, children said in interviews that they did not care whether they grew up or died. More recently, 10 years ago, in Chechnya, ten-year-old boys proudly walk around with machine guns.

A few years ago in the Chechen Republic there was a massive mental epidemic among children, mostly girls. From time to time they had brief attacks of suffocation, convulsions, they screamed in horror. The victims had the effect of psychological infection. When one child became ill, another, who was nearby, fainted, then he began to have convulsions. The phenomenon of "children of the Chechen war" has not yet been studied and understood. They were born during the war, grew up surrounded by people who experienced prolonged stress. It is impossible to imagine their state of mind when an epidemic of a mysterious disease suddenly arose among them with suffocation, convulsions, hysteria and a state of horror.

The victims had the effect of psychological infection. When one child became ill, another, who was nearby, fainted, then he began to have convulsions. The phenomenon of "children of the Chechen war" has not yet been studied and understood. They were born during the war, grew up surrounded by people who experienced prolonged stress. It is impossible to imagine their state of mind when an epidemic of a mysterious disease suddenly arose among them with suffocation, convulsions, hysteria and a state of horror.

I was told a story: last summer, several fourteen-year-old boys, sent by their parents from the south-east of Ukraine to rest in the Crimean camp, ran away. They were detained at the Simferopol railway station: the guys were going to go home and fight the punishers on their land.

Now these children could still be stopped by adults, but in a few years they will grow up, and no one will be able to prevent them from taking a machine gun and going to fight against the hated "junta". No matter who wins this war, these children will never forgive the country under the yellow and blue flag of their childhood nightmares.

No matter who wins this war, these children will never forgive the country under the yellow and blue flag of their childhood nightmares.

War and forced flight is a strong blow to the psyche of an adult, to say nothing of a child whose psyche is still being formed. As a “bonus”, all these children will receive the widest range of phobias that will interfere with their future life.

Someone will cope with their fears on their own, someone will be helped by psychologists, but someone will not, and will become one more indirect victim of an undeclared civil war. Someone will grow up in a foreign land, listening to the stories of adults about a peaceful lost land. Someone will have to grow up under the roar of guns, the pop of shots and the howling of the warning system.

But both of them will grow up and one day they will want to ask for their stolen childhood with interest.

Thousands of children are still being recruited to participate in hostilities

Children have no place in war

“The Optional Protocol, which has been ratified by 172 countries, each of which has pledged not to involve in hostilities under 18 years of age, is the expression of a global consensus that children have no place in war,” read a statement delivered by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict and members of the Human Rights Committee on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the entry into force of the protocol. They called for universal ratification of this document.

They called for universal ratification of this document.

Today, however, children still fight. Since 2005, more than a third of all serious violations of the rights of children have been related to their recruitment as soldiers and the use of parties to conflicts as sex slaves, infiltrators and servants. Since 2005, more than 93,000 children have taken part in hostilities.

Soldiers, spies, servants and child brides

According to the latest annual report of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict, in 2020 alone, the armed forces recruited approximately 8,500 children as soldiers. More than 85 percent of them are teenagers who fought on the front lines. The belligerents did not spare girls either, using them in secondary roles, including as servants, sex slaves or child brides.

“From spies to cooks, from combatants to sex slaves, whatever their roles, children used by parties to conflict are subjected to unimaginable violence,” read a joint statement on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Optional Protocol. Its authors note that the children who survived this nightmare remain "with the scars of war for the rest of their lives."

Its authors note that the children who survived this nightmare remain "with the scars of war for the rest of their lives."

In accordance with Security Council resolutions and the Paris Principles, States must take all necessary measures to ensure the release of children from armed forces and their reintegration into society, including providing them with access to education and health services and providing psychosocial support.

“Today, as we celebrate the 20th anniversary of the entry into force of the Optional Protocol, we call on States that have not yet done so to ratify this instrument and end and criminalize the recruitment of children by armed forces,” reads in a statement. Its authors called on the states that ratified the Protocol to fulfill their obligations.

Convention on the Rights of the Child

The Convention on the Rights of the Child has become one of the most universal treaties in the world. It was adopted by the UN General Assembly at 1989 and entered into force in 1990.