Pregnant with chlamydia false positive

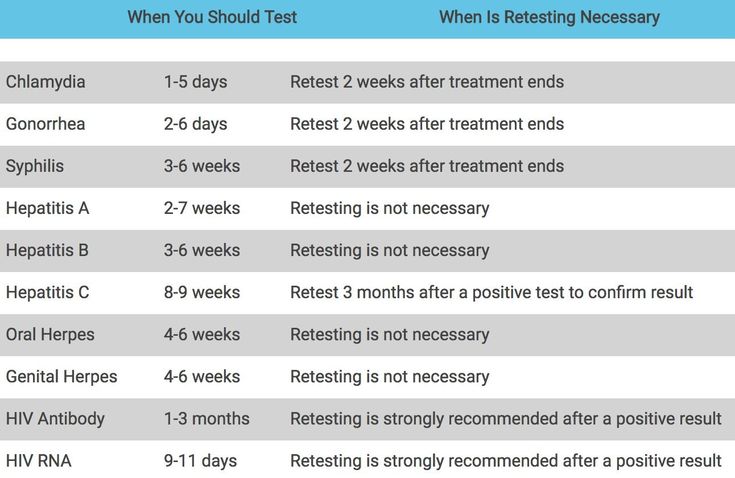

High rates of persistent and recurrent chlamydia in pregnant women after treatment with azithromycin

1. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/STDSurveillance2018-full-report.pdf. Accessed May 29, 2020.

2. Williams CL, Harrison LL, Llata E, Smith RA, Meites E. Sexually transmitted diseases among pregnant women: 5 states, United States, 2009-2011. Matern Child Health J 2018;22:538–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Torrone E, Papp J, Weinstock H; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection among persons aged 14-39 years–United States, 2007-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:834–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Cha S, Newman DR, Rahman M, Peterman TA. High rates of repeat chlamydial infections among young women-Louisiana, 2000-2015. Sex Transm Dis 2019;46:52–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Martin DH, Koutsky L, Eschenbach DA, et al. Prematurity and perinatal mortality in pregnancies complicated by maternal Chlamydia trachomatis infections. JAMA 1982;247:1585–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Voskakis I, Tsekoura C, Keramitsoglou T, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in women with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Am J Reprod Immunol 2016;76:358–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Ahmadi A, Ramazanzadeh R, Sayehmiri K, Sayehmiri F, Amirmozafari N. Association of Chlamydia trachomatis infections with preterm delivery; a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Olson-Chen C, Balaram K, Hackney DN. Chlamydia trachomatis and adverse pregnancy outcomes: meta-analysis of patients with and without infection. Matern Child Health J 2018;22:812–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Hill AV, Perez-Patron M, Tekwe CD, Menon R, Hairrell D, Taylor BD. Chlamydia trachomatis is associated with medically indicated preterm birth and preeclampsia in young pregnant women. Sex Transm Dis 2020;47:246–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chlamydia trachomatis is associated with medically indicated preterm birth and preeclampsia in young pregnant women. Sex Transm Dis 2020;47:246–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Reekie J, Roberts C, Preen D, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis and the risk of spontaneous preterm birth, babies who are born small for gestational age, and stillbirth: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:452–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Cluver C, Novikova N, Eriksson DO, Bengtsson K, Lingman GK. Interventions for treating genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9:CD010485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Blatt AJ, Lieberman JM, Hoover DR, Kaufman HW. Chlamydial and gonococcal testing during pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:55.e1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Workowski KA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(Suppl 8):S759–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(Suppl 8):S759–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

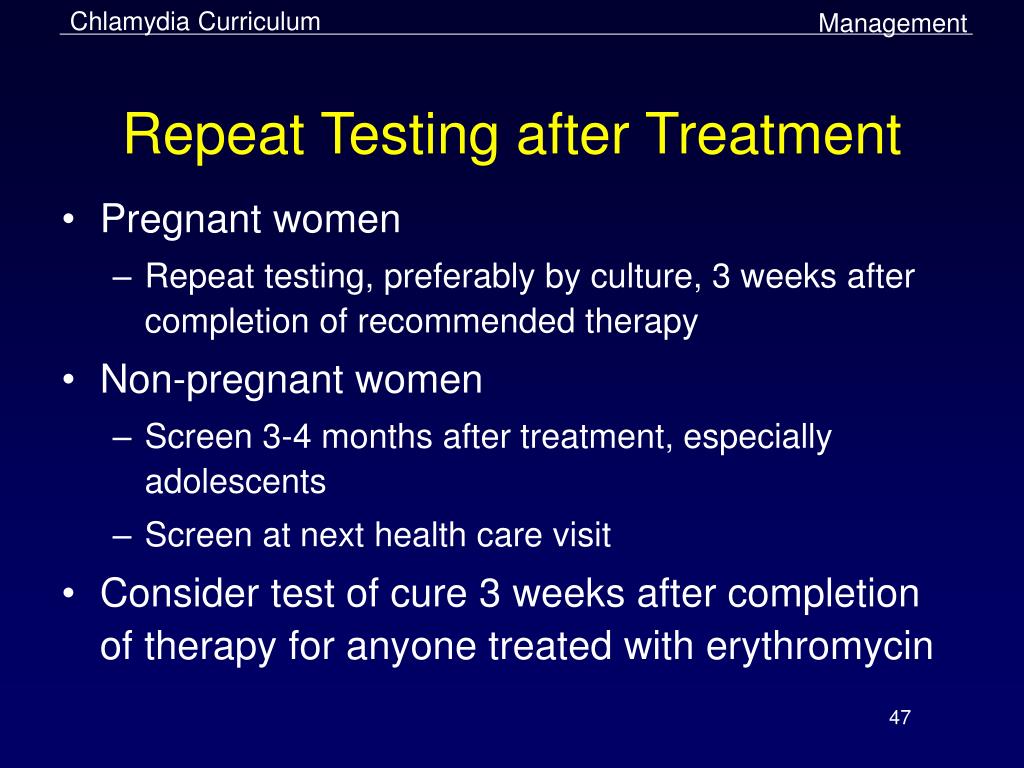

14. Lazenby GB, Korte JE, Tillman S, Brown FK, Soper DE. A recommendation for timing of repeat Chlamydia trachomatis test following infection and treatment in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Int J STD AIDS 2017;28:902–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, et al. Repeat infection with Chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: a systematic review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:478–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Khosropour CM, Bell TR, Hughes JP, Manhart LE, Golden MR. A population-based study to compare treatment outcomes among women with urogenital chlamydial infection in Washington State, 1992 to 2015. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:319–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Owings AJ, Clark LL, Rohrbeck P. Incident and recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2010-2014. MSMR 2016;23:20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MSMR 2016;23:20–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. van der Helm JJ, Koekenbier RH, van Rooijen MS, Schim van der Loeff MF, de Vries HJC. What is the optimal time to retest patients with a urogenital Chlamydia infection? A randomized controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:132–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Berggren EK, Patchen L. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae and repeat infection among pregnant urban adolescents. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:172–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Mestrovic T, Ljubin-Sternak S. Molecular mechanisms of Chlamydia trachomatis resistance to antimicrobial drugs. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2018;23:656–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Somani J, Bhullar VB, Workowski KA, Farshy CE, Black CM. Multiple drug-resistant Chlamydia trachomatis associated with clinical treatment failure. J Infect Dis 2000;181:1421–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Kirkcaldy RD, Soge O, Papp JR, et al. Analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae azithromycin susceptibility in the United States by the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 2005 to 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59:998–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Analysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae azithromycin susceptibility in the United States by the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project, 2005 to 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015;59:998–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed May 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

24. Salman S, Rogerson SJ, Kose K, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of azithromycin in pregnancy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:360–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Kong FYS, Horner P, Unemo M, Hocking JS. Pharmacokinetic considerations regarding the treatment of bacterial sexually transmitted infections with azithromycin: a review. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019;74:1157–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Kong FY, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, et al. Higher organism load associated with failure of azithromycin to treat rectal chlamydia. Epidemiol Infect 2016;144:2587–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Epidemiol Infect 2016;144:2587–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Dukers-Muijrers NH, Speksnijder AG, Morré SA, et al. Detection of anorectal and cervicovaginal Chlamydia trachomatis infections following azithromycin treatment: prospective cohort study with multiple time-sequential measures of rRNA, DNA, quantitative load and symptoms. PLoS One 2013;8:e81236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Zakher B, Cantor AG, Pappas M, Daeges M, Nelson HD. Screening for gonorrhea and Chlamydia: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:884–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae–2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014;63(RR-02):1–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Van Der Pol B, Taylor SN, Liesenfeld O, Williams JA, Hook EW 3rd. Vaginal swabs are the optimal specimen for detection of genital Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae using the Cobas 4800 CT/NG test. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Rönn MM, Mc Grath-Lone L, Davies B, Wilson JD, Ward H. Evaluation of the performance of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) in detection of chlamydia and gonorrhoea infection in vaginal specimens relative to patient infection status: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e022510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. 2019 Annual Report. America’s Health Rankings. 2019. Available at: https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2019-annual-report. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

33. A profile of prematurity in Alabama. Peristats. March of Dimes Foundation. 2018. Available at: https://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/tools/prematurityprofile.aspx?reg=01. Accessed July 28, 2020. [Google Scholar]

34. Aggarwal A, Spitzer RF, Caccia N, Stephens D, Johnstone J, Allen L. Repeat screening for sexually transmitted infection in adolescent obstetric patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32:956–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Newman LM, Warner L, Weinstock HS. Predicting subsequent infection in patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:737–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Jamison CD, Coleman JS, Mmeje O. Improving women’s health and combatting sexually transmitted infections through expedited partner therapy. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:416–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Unger JA, Matemo D, Pintye J, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment for Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Trichomonas infection among pregnant and postpartum women in Kenya. Sex Transm Dis 2015;42:637–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Cramer R, Leichliter JS, Stenger MR, Loosier PS, Slive L; SSuN Working Group. The legal aspects of expedited partner therapy practice: do state laws and policies really matter? Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:657–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Oliver A, Rogers M, Schillinger JA. The impact of prescriptions on sex partner treatment using expedited partner therapy for Chlamydia trachomatis infection, New York City, 2014-2015. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:673–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The impact of prescriptions on sex partner treatment using expedited partner therapy for Chlamydia trachomatis infection, New York City, 2014-2015. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:673–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 737: expedited partner therapy. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e190–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Mmeje O, Wallett S, Kolenic G, Bell J. Impact of expedited partner therapy (EPT) implementation on chlamydia incidence in the USA. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94:545–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Mmeje O, Coleman JS. Concurrent patient-partner treatment in pregnancy: an alternative to expedited partner therapy? Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:665–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Fischer MA, Stedman MR, Lii J, et al. Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:284–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Wehbeh H, Fleisher JM, Coasino M, Ayoub A, Margossian H, Zarou D. Erythromycin for chlamydiasis in pregnant women. Assessing adherence to a standard multiday, multidose course. J Reprod Med 2000;45:465–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Assessing adherence to a standard multiday, multidose course. J Reprod Med 2000;45:465–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Williams JA, Ofner S, Batteiger BE, Fortenberry JD, Van Der Pol B. Duration of polymerase chain reaction-detectable DNA after treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis infections in women. Sex Transm Dis 2014;41:215–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Cross R, Ling C, Day NPJ, McGready R, Paris DH. Revisiting doxycycline in pregnancy and early childhood-time to rebuild its reputation? Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016;15:367–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Kacmar J, Cheh E, Montagno A, Peipert JF. A randomized trial of azithromycin versus amoxicillin for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis in pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2001;9:197–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Pitsouni E, Iavazzo C, Athanasiou S, Falagas ME. Single-dose azithromycin versus erythromycin or amoxicillin for Chlamydia trachomatis infection during pregnancy: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007;30:213–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007;30:213–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Geisler WM. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis infections in adolescents and adults: summary of evidence reviewed for the 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(Suppl 8):S774–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Hook EW, Newman L, Drusano G, et al. Development of new antimicrobials for urogenital gonorrhea therapy: clinical trial design considerations. Clin Infect Dis 2020;70:1495–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Olson KM, Tang J, Brown L, Press CG, Geisler WM. HLA-DQB1*06 is a risk marker for chlamydia reinfection in African American women. Genes Immun 2019;20:69–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Tamarelle J, Ma B, Gajer P, et al. Nonoptimal vaginal microbiota after azithromycin treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Infect Dis 2020;221:627–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

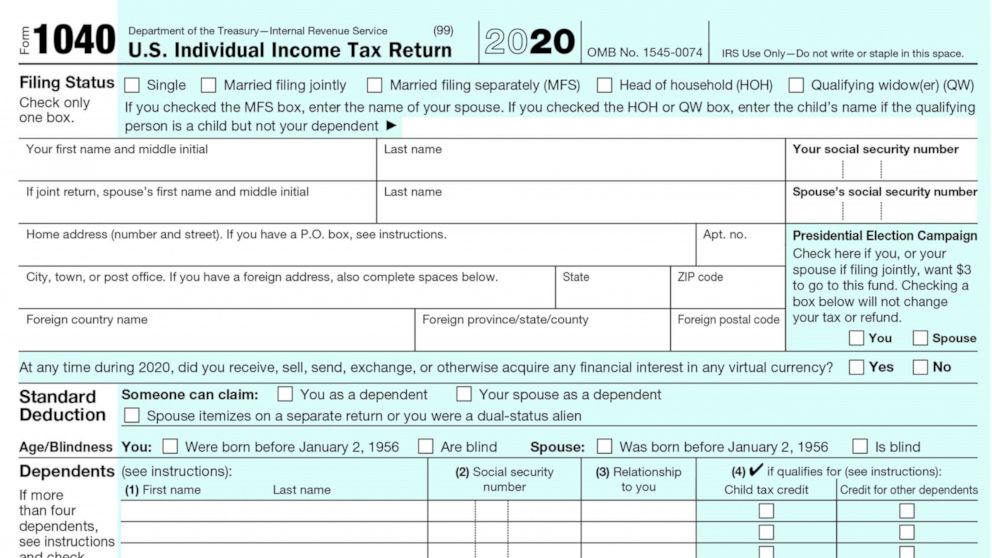

Testing for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea in Pregnancy | 2012-10-01

The authors performed a retrospective cohort study of 1,293,423 pregnant women aged 16 to 40 in the United States from June 1, 2005 to May 30, 2008, using data from the Quest Diagnostics Informatics Data Warehouse.

October 1, 2012

Reprints

Testing for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea in Pregnancy

Abstract & Commentary

By Rebecca H. Allen, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Women and Infants Hospital, Providence, RI, is Associate Editor for OB/GYN Clinical Alert.

Dr. Allen reports no financial relationships relevant to this field of study.

Synopsis: In this national retrospective study, 59% and 57% of women were tested at least once during pregnancy for Chlamydia trachomatis or for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, respectively. Of those women testing positive, 78% and 76% underwent a test of cure for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae, respectively.

Of those women testing positive, 78% and 76% underwent a test of cure for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae, respectively.

Source: Blatt AJ, et al. Chlamydial and gonococcal testing during pregnancy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:55.e1-8.

The authors performed a retrospective cohort study of 1,293,423 pregnant women aged 16 to 40 in the United States from June 1, 2005 to May 30, 2008, using data from the Quest Diagnostics Informatics Data Warehouse. Women aged 16-40 years who had an obstetrical panel (that included a rubella antibody test) performed at Quest Diagnostics were assumed to be pregnant, and those who had any further laboratory tests at Quest Diagnostics during what was estimated to be the third trimester (to ensure continuity) were enrolled as subjects. Of these women, 525,258 (41%) had race data available through the maternal serum screen test. In addition, the authors identified Medicaid insurance as a marker of socioeconomic status. Chlamydial and gonoccocal testing results were then extracted, and testing was determined to be at the first prenatal visit if it occurred shortly before or during the visit when the obstetric lab panel test was performed.

Chlamydial and gonoccocal testing results were then extracted, and testing was determined to be at the first prenatal visit if it occurred shortly before or during the visit when the obstetric lab panel test was performed.

The study population was similar in race and proportion on Medicaid (18.1%) to the total U.S. pregnant population. Although the study population was older than the total U.S. pregnant population, the authors adjusted for this in the results. The authors found that 761,315 (59%) and 730,796 (57%) of women were tested at least once during pregnancy for Chlamydia trachomatis or for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, respectively (the age-adjusted rates were 60% and 58%, respectively). In addition, 37% of women were tested for C. trachomatis during the first prenatal visit. Testing rates for chlamydia were highest for younger women (71.5% for age 16 to 24 compared to 58.5% for age 35 to 40) and African American women (74% compared to 59.2% for whites). Of those tested at least once, the prevalence of C. trachomatis was 3.5% and the prevalence of N gonorrhoeae was 0.6% (the age-adjusted rates were 4.6% and 0.8%, respectively). Not surprisingly, the prevalence of infection was highest among younger ages with 16% of 16-year-olds testing positive compared to < 1% of women older than age 35 years. A test of cure was performed for 78% of chlamydia-positive women and 76% for gonorrhea-positive women. Test of cures were positive among 6% of women with chlamydia and 3.8% of women with gonorrhea.

Of those tested at least once, the prevalence of C. trachomatis was 3.5% and the prevalence of N gonorrhoeae was 0.6% (the age-adjusted rates were 4.6% and 0.8%, respectively). Not surprisingly, the prevalence of infection was highest among younger ages with 16% of 16-year-olds testing positive compared to < 1% of women older than age 35 years. A test of cure was performed for 78% of chlamydia-positive women and 76% for gonorrhea-positive women. Test of cures were positive among 6% of women with chlamydia and 3.8% of women with gonorrhea.

Commentary

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all pregnant women be screened for chlamydial infection during their first prenatal care visit.1 The rationale for universal screening is the relatively high prevalence of infection (2 -13%), the existence of effective treatment options, and the negative sequelae of chlamydial infection for the pregnancy and neonate. If negative, the test should be repeated for pregnant women at increased risk (women aged 25 years or younger, or women who have a new, or more than one, sexual partner) in the third trimester. If positive, a test of cure should be performed 3 weeks after completing therapy to confirm successful treatment, and the woman should be rescreened in the third trimester. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued similar recommendations.2 For gonorrhea, ACOG and the CDC recommend screening only for pregnant women at increased risk for infection.1,2 However, in clinical practice, commercially available assays most frequently test for both infections simultaneously. Therefore, testing rates for both infections are usually identical, as this study demonstrates.

If negative, the test should be repeated for pregnant women at increased risk (women aged 25 years or younger, or women who have a new, or more than one, sexual partner) in the third trimester. If positive, a test of cure should be performed 3 weeks after completing therapy to confirm successful treatment, and the woman should be rescreened in the third trimester. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued similar recommendations.2 For gonorrhea, ACOG and the CDC recommend screening only for pregnant women at increased risk for infection.1,2 However, in clinical practice, commercially available assays most frequently test for both infections simultaneously. Therefore, testing rates for both infections are usually identical, as this study demonstrates.

The authors of this study report the prevalence of chlamydia and gonorrhea among pregnant women and compliance with ACOG and CDC recommendations. The study population was similar to the population of pregnant women in the United States; therefore, the results are generalizable to those women with access to health care. As a retrospective study, the most important limitation is lack of access to the clinical records of participants to determine why they were not screened or whether follow-up took place at another laboratory. Nevertheless, the report provides a picture of compliance, with ACOG and CDC recommendations among insured pregnant women. Unfortunately, compliance was not ideal with 40% of pregnant women not tested at all for chlamydia. Test of cures also were not performed according to recommendations. The fact that younger women were more likely to be tested indicates that clinicians were probably using a risk-based screening strategy, which was ACOG's position prior to 2007 and is the recommendation for non-pregnant women. In defense of these clinicians, screening guidelines were changed during the study period.

As a retrospective study, the most important limitation is lack of access to the clinical records of participants to determine why they were not screened or whether follow-up took place at another laboratory. Nevertheless, the report provides a picture of compliance, with ACOG and CDC recommendations among insured pregnant women. Unfortunately, compliance was not ideal with 40% of pregnant women not tested at all for chlamydia. Test of cures also were not performed according to recommendations. The fact that younger women were more likely to be tested indicates that clinicians were probably using a risk-based screening strategy, which was ACOG's position prior to 2007 and is the recommendation for non-pregnant women. In defense of these clinicians, screening guidelines were changed during the study period.

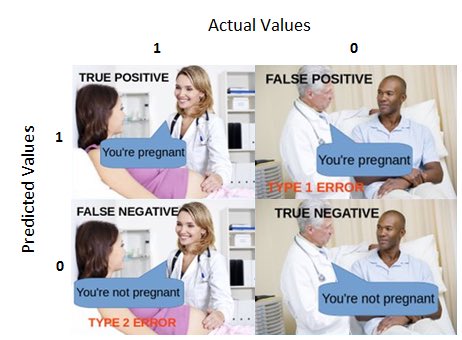

Not all organizations agree with ACOG and the CDC regarding universal testing for chlamydia among pregnant women. One might ask whether a 36-year-old, pregnant woman in a monogamous sexual relationship really needs to be screened for chlamydia. There is a significant harm from a false-positive diagnosis for the pregnant woman's relationship, and false-positive results increase when the prevalence is low. This study showed a very low prevalence in older women. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) only recommends chlamydial screening among pregnant women aged 24 and younger and among older pregnant women at increased risk.3 The USPSTF recommends against routine screening of women age 25 and older, whether pregnant or not, who have no risk factors. Clinical practice likely varies within and between communities. In our hospital, the low-income prenatal care clinic where I work always has screened universally for chlamydia. In contrast, a few of the private OB/GYN practices are only now beginning to adopt universal testing of pregnant women. Which testing strategy you employ depends on which organization you adhere to, with ACOG and the CDC on one side and the more conservative USPSTF on the other. Clinical judgment is paramount and screening can be individualized according to the USPSTF.

There is a significant harm from a false-positive diagnosis for the pregnant woman's relationship, and false-positive results increase when the prevalence is low. This study showed a very low prevalence in older women. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) only recommends chlamydial screening among pregnant women aged 24 and younger and among older pregnant women at increased risk.3 The USPSTF recommends against routine screening of women age 25 and older, whether pregnant or not, who have no risk factors. Clinical practice likely varies within and between communities. In our hospital, the low-income prenatal care clinic where I work always has screened universally for chlamydia. In contrast, a few of the private OB/GYN practices are only now beginning to adopt universal testing of pregnant women. Which testing strategy you employ depends on which organization you adhere to, with ACOG and the CDC on one side and the more conservative USPSTF on the other. Clinical judgment is paramount and screening can be individualized according to the USPSTF. Nonetheless, since a pelvic exam is routinely performed at the first prenatal visit, it is not difficult to collect a cervical sample for chlamydia (and gonorrhea).

Nonetheless, since a pelvic exam is routinely performed at the first prenatal visit, it is not difficult to collect a cervical sample for chlamydia (and gonorrhea).

References

- Guidelines for Perinatal Care, 6th ed. Washington DC: American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetrician Gynecologists; 2007.

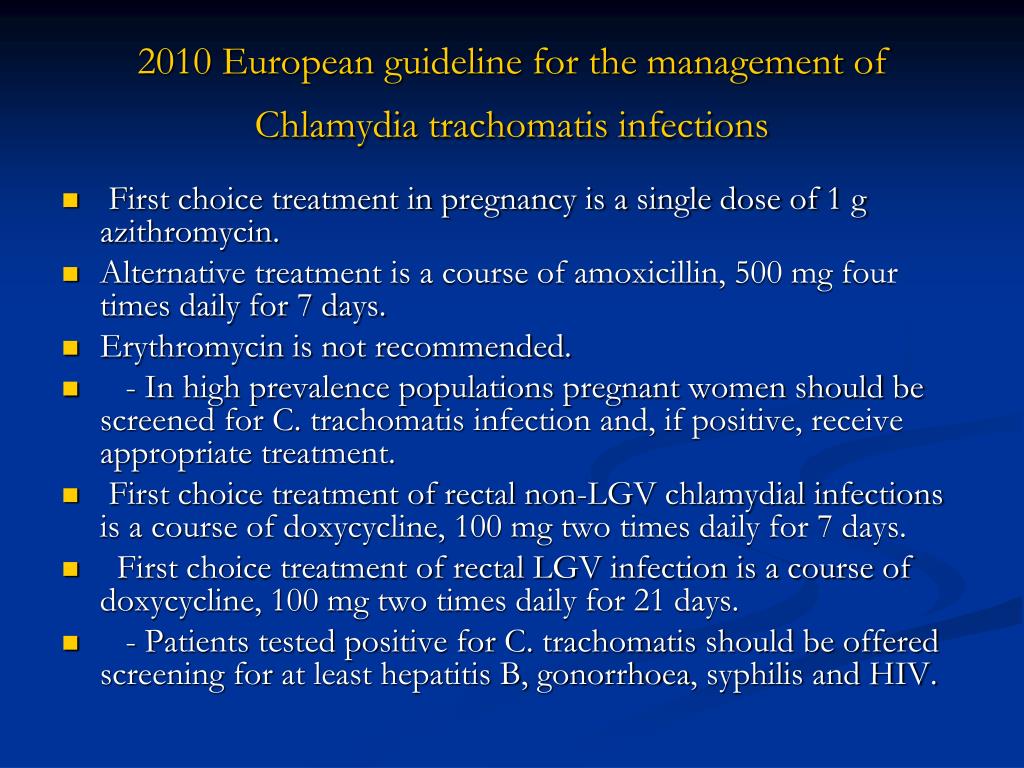

- Workowski KA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010;59:1-110.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydial infection. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspschlm.htm. Accessed Aug. 24, 2012.

You have reached your article limit for the month. We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.

We hope you found our articles both enjoyable and insightful. For information on new subscriptions, product trials, alternative billing arrangements or group and site discounts please call 800-688-2421. We look forward to having you as a long-term member of the Relias Media community.

Chlamydia and pregnancy

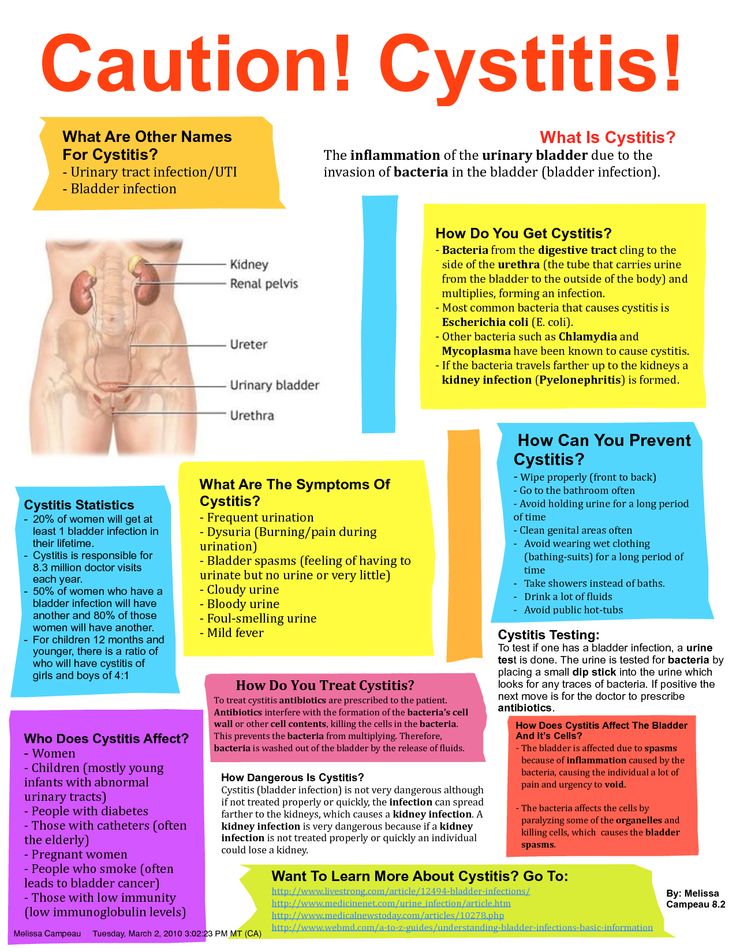

Their favorite habitat is the cervix (more precisely, the mucous membrane of the cervical canal). It is there that they are located in colonies, i.e. are not found throughout. Such frequent cases are associated with this fact, when one doctor takes a smear from the cervical canal and chlamydia is found in it, and the other one also takes a smear a day later, but chlamydia is not found again. That is why the diagnostic value of swabs for chlamydia is quite low - about 30%.

How chlamydia manifests itself

During an exacerbation of the infectious process, women's complaints may be different, depending on the level of chlamydia spread.

When chlamydia is found in the cervix, there may be slight discharge from the vagina, accompanied by moderate pulling pains in the lower abdomen, which is typical with local exacerbation of the process (there are practically no complaints in the chronic form). If the infection spreads higher (uterine cavity, tubes), then the complaints are more pronounced, because, for example, inflammation of the appendages may begin.

Exacerbation of chlamydial infection is especially dangerous during pregnancy, as it can lead to various complications.

Possible complications:

- early miscarriages are possible,

- late term premature amniotic fluid and preterm labor,

- in childbirth, there is a high probability of infection of the fetus (conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, otitis and even pneumonia).

Chlamydia diagnostics

The most informative method is a blood test for antibodies (immunoglobulins) to chlamydia. If a small concentration of these antibodies is detected, then they speak of a chronic carriage of chlamydia. If the concentration is high, there is an exacerbation of chlamydial infection.

The diagnosis of "chlamydia" is legitimate when it is confirmed by two fundamentally different diagnostic methods: smear (microscopy) and blood for antibodies to chlamydia (biochemical method). Only when the titer (concentration) of antibodies is high and / or in the presence of complaints specific to this infection, a course of treatment is indicated.

Digits must be multiples, i.e. more or less than twice, from the previous one (IgA 1:40 and IgG 1:80). Titers of 1:5 and less are doubtful and negative. Elevated IgG numbers indicate that the process is chronic. In this case, treatment is indicated if there are certain complaints, or if before that, the person has never been treated for this infection. High numbers of IgA are mainly found in an acute process (primary infection) or during an exacerbation of a chronic one that needs treatment.

High numbers of IgA are mainly found in an acute process (primary infection) or during an exacerbation of a chronic one that needs treatment.

What to do if the test is positive?

It must be remembered that today there are almost no 100% reliable methods, including the ELISA method (enzymatic immunoassay) is no exception. Quite often there are “false positive” results - you have to do either repeated tests or use other, fundamentally different methods.

These can be:

- taking smears for the PIF method (examination with a luminescent microscope) - where there may also be “false positive” answers,

- PCR blood test (based on the principle of genetic engineering, the study of DNA or its fragments) - today, its reliability is very high.

In the search for the truth of the diagnosis, quite often, everything can rest either on the financial capabilities of patients, or on the insufficient equipment of a particular laboratory. The better the body's defenses, the less likely it is to contract chlamydia. In which case, only “carriage” threatens you, it is not dangerous for you (only IgG, in low titers, will be determined in the blood test).

The better the body's defenses, the less likely it is to contract chlamydia. In which case, only “carriage” threatens you, it is not dangerous for you (only IgG, in low titers, will be determined in the blood test).

It is considered optimal if the whole family is examined at the same time (all interested persons, including children), because in this case, it is possible to identify who is at what stage and monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

In most cases, the pathogens of ureplasmosis and mycoplasmosis do not manifest themselves (hidden bacteriocarrier), and only when the process is exacerbated, they cause pregnancy complications similar to chlamydia and infection of the fetus. Therefore, when examining women who have had the above problems in the past, swabs and blood are taken at least immediately for these three pathogens. By the way, studies have shown that taking hormonal birth control pills reduces the risk of chlamydia infection, this effect is associated with an increase in the protective properties of cervical mucus (its permeability to bacteria decreases). As mentioned above, chlamydia is dangerous for pregnant women.

As mentioned above, chlamydia is dangerous for pregnant women.

What to do?

But what to do if, after all, doctors found chlamydia in the acute stage in the expectant mother?

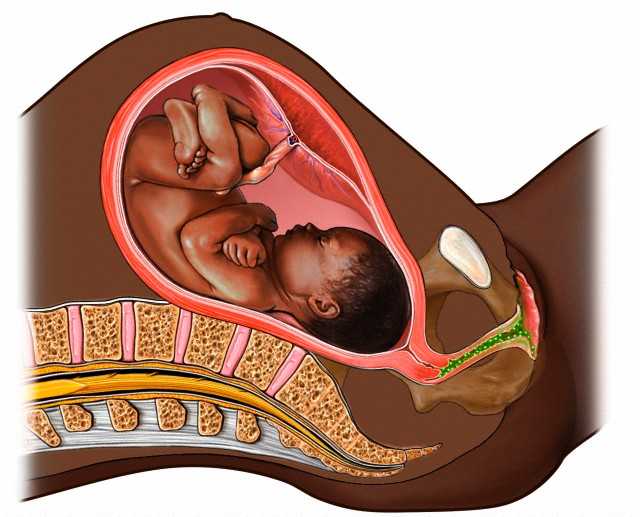

The placenta can be thought of as a mesh filter through which large molecules cannot pass (they remain in the mother's body). Therefore, in the treatment of a pregnant woman, antibiotics are used that are harmless to the fetus (i.e. those that do not pass through the placenta). These include drugs whose molecular weight is greater than the "capacity" of the capillaries. However, when taking these drugs, the effect on the fetus is still possible. The antibiotic acts primarily on the mother's body, however, during the period of treatment, it changes the metabolism in the body, which in turn affects the metabolism of the fetus. Antibiotics are always prescribed in short courses so that the effects are minimal.

References

- Zofkie AC., Fomina YY., Roberts SW., McIntire DD.

, Nelson DB., Adhikari EH. Effectiveness of Chlamydia Trachomatis expedited partner therapy in pregnancy. // Am J Obstet Gynecol - 2021 - Vol - NNULL - p.; PMID:33894150

, Nelson DB., Adhikari EH. Effectiveness of Chlamydia Trachomatis expedited partner therapy in pregnancy. // Am J Obstet Gynecol - 2021 - Vol - NNULL - p.; PMID:33894150 - Zofkie AC., Fomina YY., Roberts SW., McIntire DD., Nelson DB., Adhikari EH. Effectiveness of Chlamydia Trachomatis expedited partner therapy in pregnancy. // Am J Obstet Gynecol - 2021 - Vol - NNULL - p.; PMID:33894147

- Shilling HS., Garland SM., Costa AM., Marceglia A., Fethers K., Danielewski J., Murray G., Bradshaw C., Vodstrcil L., Hocking JS., Kaldor J., Guy R., Machalek D.A. Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence and associated factors among women presenting to a pregnancy termination and contraception clinic, 2009-2019. // Sex Transm Infect - 2021 - Vol - NNULL - p.; PMID:33782146

- Vercruysse J., Mekasha S., Stropp LM., Moroney J., He X., Liang Y., Vragovic O., Valle E., Ballard J., Pudney J., Kuohung W., Ingalls RR. Chlamydia trachomatis Infection, when Treated during Pregnancy, Is Not Associated with Preterm Birth in an Urban Safety-Net Hospital.

// Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol - 2020 - Vol2020 - NNULL - p.8890619; PMID:33082702

// Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol - 2020 - Vol2020 - NNULL - p.8890619; PMID:33082702 - Olaleye AO., Babah OA., Osuagwu CS., Ogunsola FT., Afolabi BB. Sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy - An update on Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. // Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol - 2020 - Vol255 - NNULL - p.1-12; PMID:33059307

- Hoenderboom BM., van Bergen JEAM., Dukers-Muijrers NHTM., Götz HM., Hoebe CJPA., de Vries HJC., van den Broek IVF., de Vries F., Land JA., van der Sande MAB., Morré SA., van Benthem BHB. Pregnancies and Time to Pregnancy in Women With and Without a Previous Chlamydia trachomatis Infection. // Sex Transm Dis - 2020 - Vol47 - N11 - p.739-747; PMID:32701764

- He W., Jin Y., Zhu H., Zheng Y., Qian J. Effect of Chlamydia trachomatis on adverse pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. // Arch Gynecol Obstet - 2020 - Vol302 - N3 - p.553-567; PMID:32643040

- Freeman J., Pettit J., Howe C. Chlamydia test-of-cure in pregnancy.

// Can Fam Physician - 2020 - Vol66 - N6 - p.427-428; PMID:32532724

// Can Fam Physician - 2020 - Vol66 - N6 - p.427-428; PMID:32532724 - Rajabpour M., Emamie AD., Pourmand MR., Goodarzi NN., Asbagh FA., Whiley DM. Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis among women with genitourinary infection and pregnancy-related complications in Tehran: A cross-sectional study. // Int J STD AIDS - 2020 - Vol31 - N8 - p.773-780; PMID:32517577

- Goggins ER., Chamberlain AT., Kim TG., Young MR., Jamieson DJ., Haddad LB. Patterns of Screening, Infection, and Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea in Pregnancy. // Obstet Gynecol - 2020 - Vol135 - N4 - p.799-807; PMID:32168225

Actual problems of treatment of pregnant women with recurrent chlamydial infection | #10/07

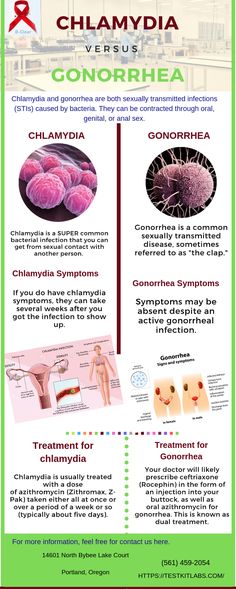

Specific infectious diseases of the genital tract in pregnant women significantly increase the incidence of maternal and perinatal complications. An infection such as chlamydia associated with mycoplasmas, cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus infections, as well as their combination with bacterial lesions are one of the leading causes of perinatal mortality (Koroleva A. I., 2000; Strizhakov A.N. et al., 2003). In recent years, the number of chlamydial, viral, mycoplasmal and mixed infections has increased, the fight against which presents significant difficulties due to the developing resistance of microorganisms to antibiotics and the characteristics of the body's responses (Glazkova L.K., 1999; Ryumin D.V., 1999; Semenov V. M., 2000; Khryanin A. A., 2001; Johnson R.A., 2000).

I., 2000; Strizhakov A.N. et al., 2003). In recent years, the number of chlamydial, viral, mycoplasmal and mixed infections has increased, the fight against which presents significant difficulties due to the developing resistance of microorganisms to antibiotics and the characteristics of the body's responses (Glazkova L.K., 1999; Ryumin D.V., 1999; Semenov V. M., 2000; Khryanin A. A., 2001; Johnson R.A., 2000).

The frequency of urogenital chlamydia in pregnant women remains high, ranging from 3% to 74% according to various authors (Astsaturova O.R., 2001; Prilepskaya V.N. et al., 1998; Semenov V.M., 2000; Hiltunen-Back E., 2001; Stamm W. E., 1999).

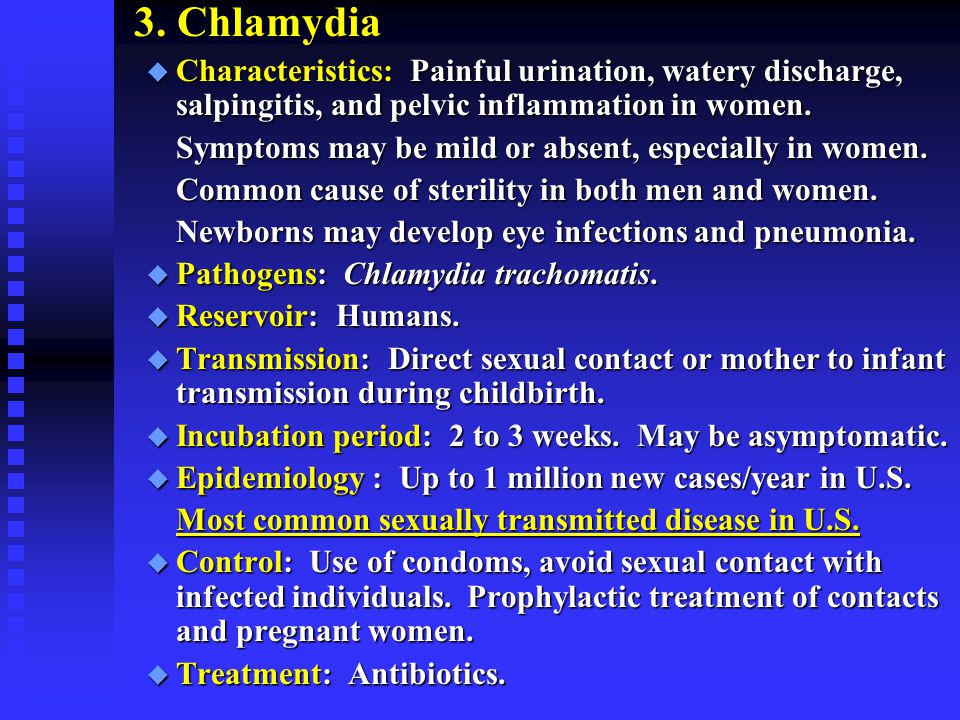

Chlamydia trachomatis has now been proven to be an obligate human parasite. Infection occurs through sexual contact, rarely through domestic contact (Plieva Z. A., 2000; Morion R. S., Kinghom G. R., 1999).

Chlamydia infection leads to abortion, miscarriage, development of fetoplacental insufficiency, intrauterine infection (IUI) of the fetus, postpartum inflammatory diseases, neonatal infections.

In the first trimester of pregnancy, the most characteristic complication is threatened miscarriage, non-developing pregnancy and spontaneous abortion. In the II and III trimesters, the threat of abortion has a long course, and tocolytic therapy, as a rule, gives an unstable effect. This is due to infection of the amnion with chlamydia, which occurs in 65% of pregnant women. Taurus Chlamydia trachomatis were found in all tissue structures of the placenta of women with genital chlamydia. It was noted that cells affected by chlamydia were found in the lumen of the capillaries of the chorionic villi, which indicates a possible hematogenous route of infection transmission from mother to fetus. In the placentas of women with genital chlamydia, there is a violation of immune homeostasis with the formation of pathogenic immune complexes (PIC), including IgM, IgG, IgA and fixing the complement C3 fraction as a marker of pathogenicity. It has been shown that the fixation of PIC on the membrane structures of the placenta leads to the destruction of the syncytium membranes and the placental barrier. The latter causes the development of placental insufficiency and damage to the feto-placental system.

The latter causes the development of placental insufficiency and damage to the feto-placental system.

In cases of infection of the amniotic membranes, polyhydramnios, a specific lesion of the placenta (placentitis), placental insufficiency, hypotrophy and fetal hypoxia may develop. True fetal malformations are not pathognomonic for chlamydial infection.

In the process of an echographic examination of pregnant women with intrauterine infection, the following echographic signs are significantly more common: polyhydramnios, oligohydramnios, hyperechoic suspension in the amniotic fluid, changes in the placenta. When conducting ultrasound placenography in women with infectious pathology of the genitals, the following changes are detected: thickening of the placenta, heterogeneous echogenicity of the parenchyma of the placenta, premature "aging" of the placenta, expansion of the intervillous spaces, expansion of the subchorionic space, thickening / doubling of the contour of the basal plate. In 75% there is a combination of two or more options for changing the echographic structure of the placenta.

In 75% there is a combination of two or more options for changing the echographic structure of the placenta.

It should be noted that in the presence of more than two echographic markers in a newborn, intrauterine infection is diagnosed postnatally in 82% of cases.

For pregnant women with chlamydial infection and fetoplacental insufficiency, its primary manifestations are disturbances in intraplacental blood flow.

The mechanisms of IUI in chlamydial infection include the following routes of infection:

- ascending - in the presence of a specific lesion of the lower genital tract;

- descending - with the localization of the inflammatory focus in the area of the uterine appendages;

- transdecidual - in the presence of infection in the endometrium;

- hematogenous - in most cases due to the ability of chlamydia to persist for a long time in peripheral blood lymphocytes;

- contagious - direct contamination of the newborn when passing through the birth canal.

In the absence of fetal hypoxia and aspiration of the infected contents of the birth canal, the risk of developing a severe infection in a newborn is lower than with prolonged contact of the fetus with an infected environment during pregnancy. So, almost half of newborns from mothers with chlamydia have a clinically significant infection.

Neonatal manifestations of chlamydial infection include lesions of the skin and mucous membranes (conjunctivitis), pneumonia, otitis, vulvitis, urethritis. Premature babies may develop specific myocarditis after chlamydial pneumonia; cases of chlamydial meningitis and encephalitis have been described.

Depending on the route of infection and the infectious dose, manifestations of perinatal chlamydial infection can occur not only in the first 168 hours of a newborn's life (early neonatal period), but also occur during the first months of a child's life.

The main method of dealing with such complications is the timely conduct of rational etiotropic antibiotic therapy.

At the same time, the vast majority (62-84%) of genital infections have a mixed etiology. Among the concomitant pathogens, mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas, viruses, anaerobes and fungi (causative agents of vaginal microcenosis disorders) are most often detected. In this regard, for the treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), antibacterial drugs with high bioavailability and activity against other bacterial pathogens with intracellular persistence should be used. A different spectrum of pregnancy complications associated with the infectious process and multifocal lesions inherent in chlamydia require complex approaches to therapy.

Patients with bacterial STIs are most often prescribed systemic antibiotic therapy, taking into account the estimated or determined sensitivity of the pathogen.

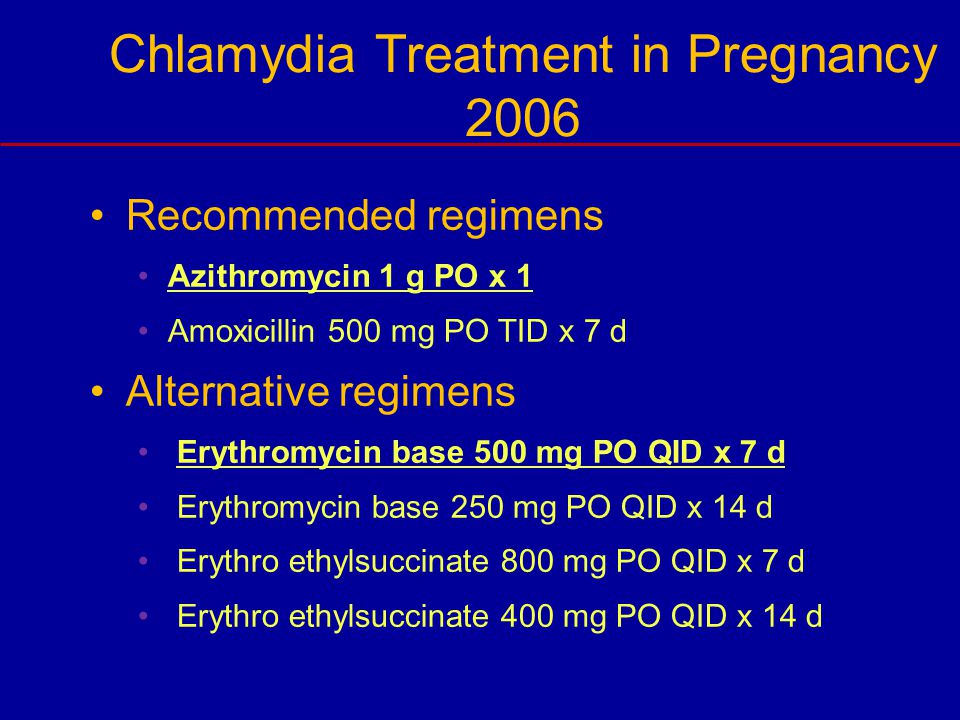

The general provisions are the predominant use of macrolides as drugs of choice for the treatment of chlamydial, mycoplasmal and ureaplasma infections in pregnant women, the start of treatment after 20 weeks of gestation or in the third trimester of pregnancy.

For the treatment of urogenital chlamydia in gynecological practice, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones and macrolides are used. The use of tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones during pregnancy and lactation is contraindicated due to the presence of adverse effects on the embryo, fetus and newborn.

For the treatment of pregnant women with genital infections, macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin, spiromycin and josamycin are used, the use of which, taking into account the gestational age, is safe for the mother and fetus.

One of the most studied in terms of safety in pregnant women is the macrolide antibiotic josamycin (Vilprafen). Of great clinical importance is its high activity against such intracellular pathogens as C. trachomatis, M. hominis, M. genitalium, U. Ureallyticum. Josamycin is quickly and completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), creating a maximum concentration in blood plasma after 1 hour. An important aspect that determines the success of treatment is the achievement of high concentrations of the drug in tissues compared to blood plasma. The ability of josamycin to accumulate predominantly in phagocytic cells is especially important for the elimination of intracellular pathogens. It has been proven that phagocytes deliver josamycin to the localization sites of the infectious agent, where the active substance is released during phagocytosis, and the concentration of josamycin in the focus of infection is 30% higher than in healthy tissues. Unlike a number of drugs of this class, josamycin does not stimulate intestinal motility and does not inhibit such important components of the liver metabolic system as cytochrome P 450 and NADP-cytochrome C reductase. Thus, josamycin is distinguished by an optimal spectrum of activity against urogenital pathogens, favorable pharmacokinetics and high safety, including in pregnant women.

The ability of josamycin to accumulate predominantly in phagocytic cells is especially important for the elimination of intracellular pathogens. It has been proven that phagocytes deliver josamycin to the localization sites of the infectious agent, where the active substance is released during phagocytosis, and the concentration of josamycin in the focus of infection is 30% higher than in healthy tissues. Unlike a number of drugs of this class, josamycin does not stimulate intestinal motility and does not inhibit such important components of the liver metabolic system as cytochrome P 450 and NADP-cytochrome C reductase. Thus, josamycin is distinguished by an optimal spectrum of activity against urogenital pathogens, favorable pharmacokinetics and high safety, including in pregnant women.

It should be noted that at present, the bacteriostatic antibiotic erythromycin is practically not used to treat urogenital chlamydia, since its microbiological efficacy often does not exceed 30% (Astsaturova O. R. et al., 2001; Strachunsky L. S., 1998; Ridgway G. L. , 1995).

R. et al., 2001; Strachunsky L. S., 1998; Ridgway G. L. , 1995).

In order to identify the frequency of genital infections, risk factors for their development, leading to complications of pregnancy, childbirth and their outcomes for the newborn, a survey of 5430 pregnant women was conducted on the basis of the maternity hospital and the consultative and diagnostic center at City Clinical Hospital No. 7 from 1997 to 2005

The control group consisted of 200 women with no history of genital infections and during pregnancy, whose children were not diagnosed with infectious and inflammatory diseases in the early neonatal period.

The incidence of sexually transmitted diseases was 17.85% (969). The structure of STIs in pregnant women was represented by chlamydia (24.56%), mycoplasma (8.36%), ureaplasma (3.1%), trichomonas (4.85%), mixed (5913%) infections.

Acute and exacerbations of chronic viral diseases were observed in 10.24% (556 cases) and were represented by herpetic lesions in 8. 34%, cytomegalovirus infection in 0.78% and human papillomavirus infection in 1.12%.

34%, cytomegalovirus infection in 0.78% and human papillomavirus infection in 1.12%.

The high frequency of mixed infections in chlamydia, the presence of an asymptomatic and latent course leads to the need for a comprehensive diagnosis of STIs and disorders of the vaginal microcenosis.

None of the modern methods of diagnosing chlamydia provides 100% reliability. Therefore, laboratory diagnostics should be based on a combination of at least two methods, one of which should be the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method.

Direct identification of elementary bodies (ET) and reticular bodies (RT) of chlamydia is possible with microscopy of smears stained according to Romanovsky–Giemsa. Cytoplasmic inclusions are defined as microcolonies stained in dark blue or pink (Halberstadter-Prowaczek bodies). The sensitivity of the cytological method for detecting chlamydia does not exceed 10-12%. The method allows to assess the state of vaginal microcenosis, the number of leukocytes, to identify the presence of yeast-like fungi, Trichomonas vaginalis.

The most common method for diagnosing chlamydial infection - immunocytological - is based on the reaction of direct or indirect immunofluorescence (determination of the C. trachomatis antigen).

When it is used, fluorescein-labeled monoclonal antibodies are added to the biological material. The resulting smears are evaluated under a fluorescent microscope. The sensitivity of the method ranges from 65–90%, and the specificity is 85–90%. The main disadvantages of the method are its subjectivity and low sensitivity.

ELISA is based on the identification of chlamydia antigens by binding them with antibodies. Quantification of antigen-antibody complexes is carried out using automated determination of the severity of the color reaction. The advantage of the method is the ability to determine soluble antigens, the duration (4-6 hours), the disadvantage is the possibility of obtaining false negative and false positive reactions.

PCR has advantages over immunological methods: high specificity - 95%; maximum sensitivity; speed of conduction (4-5 hours). The disadvantage of PCR diagnostics of chlamydia is that the DNA amplification method does not allow assessing the viability of the cell, it gives positive results with small amounts of the pathogen and the presence of individual fragments of its genome. Despite this, PCR should be the primary method for assessing chlamydia elimination. Upon receipt of a positive result, a microbiological study is indicated, and if the latter is impossible, a repeated PCR after 5-6 weeks.

The disadvantage of PCR diagnostics of chlamydia is that the DNA amplification method does not allow assessing the viability of the cell, it gives positive results with small amounts of the pathogen and the presence of individual fragments of its genome. Despite this, PCR should be the primary method for assessing chlamydia elimination. Upon receipt of a positive result, a microbiological study is indicated, and if the latter is impossible, a repeated PCR after 5-6 weeks.

The most reliable method for diagnosing chlamydia is a combination of culture and PCR.

Methods for indirect diagnosis of chlamydial infection include determining the level of specific antibodies. The accumulation of antibodies of classes M, G and A occurs at different intervals and depends on the nature of the infection (primary infection, reinfection). During primary infection, IgM appears first, then G, then A. In secondary infection, there is a rapid increase in antibodies of classes G and A against the background of the absence of IgM. This research method allows you to determine the stage of the disease, evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment, prove the chlamydial etiology of extragenital lesions.

This research method allows you to determine the stage of the disease, evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment, prove the chlamydial etiology of extragenital lesions.

Determination of DNA Chlamidia trachomatis was carried out by PCR. Scraping from the cervical canal, from mucous membranes, saliva, urine and blood of newborns served as materials for research. All scrapings were taken using disposable sterile cytological brushes from PathFinder (USA). A Tertsik™ multichannel DNA amplifier and reagent kits for it (JSC Petrovax, Institute of Immunology, Moscow) were used.

In 238 pregnant women, acute chlamydial infection (disease duration less than 2 months) was present in 79(33.19%), chronic (more than 2 months) — in 159 (66.8%). The majority of patients with chronic infection (62%) had anamnestic data indicating the duration of the disease for more than six months and inadequate previous therapy.

Under our observation in the course of the prospective part of the study were 72 pregnant women with a gestational age of 29-41 weeks, in 33 (45. 83%) of which the previous etiological therapy for acute or chronic chlamydial infection was ineffective, as well as 28 (38.89%) of women with chronic recurrent infection and 11 (15.28%) pregnant women who prematurely discontinued previously started therapy. Prior to inclusion in the study, patients received various antibiotic therapy: in the first subgroup, 16 (57.14%) pregnant women for chlamydial infection took erythromycin 1-3 g/day, 9 - azithromycin 0.25 g/day, 8 - spiramycin 9 million units/day It should be noted the inadequacy of the daily dose of erythromycin and azithromycin for the treatment of chlamydia.

83%) of which the previous etiological therapy for acute or chronic chlamydial infection was ineffective, as well as 28 (38.89%) of women with chronic recurrent infection and 11 (15.28%) pregnant women who prematurely discontinued previously started therapy. Prior to inclusion in the study, patients received various antibiotic therapy: in the first subgroup, 16 (57.14%) pregnant women for chlamydial infection took erythromycin 1-3 g/day, 9 - azithromycin 0.25 g/day, 8 - spiramycin 9 million units/day It should be noted the inadequacy of the daily dose of erythromycin and azithromycin for the treatment of chlamydia.

Interesting is the fact that 9Of the 11 pregnant women who stopped the started treatment on their own (81%), they received erythromycin and spiramycin. On purposeful questioning, the present study found that they motivated the refusal of therapy by "danger to the child" when taking "such high doses" of the antibiotic.

All patients, after explaining the characteristics of the course of chlamydial infection, its danger to the pregnant woman and the fetus, the need for antibiotic therapy and treatment aimed at stopping pregnancy complications, the action of the drug josamycin (Vilprafen) and the regimen for its use, were prescribed therapy, which included taking 1 tablet (500 mg ) Vilprafen 3 times / day for 10 days. All sexual partners of the patients were examined and treated for genital infections. After therapy with Vilprafen, pregnant women recorded possible side effects of the drug (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, changes in the nature of the stool, flatulence, rash, pruritus) for 3 days.

All sexual partners of the patients were examined and treated for genital infections. After therapy with Vilprafen, pregnant women recorded possible side effects of the drug (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, changes in the nature of the stool, flatulence, rash, pruritus) for 3 days.

The effectiveness of therapy was monitored based on the results of PCR 4 weeks after taking Vilprafen. Treatment was considered effective in the absence of detection of the Chlamydia trachomatis genome. If the results of the first PCR were positive, a culture study was performed (or PCR after 5–6 weeks).

The microbiological efficacy of josamycin in pregnant women with chlamydial infection, according to the results of the first follow-up examination, was 93.06%. In three cases, with positive results of the first PCR, no growth of C. trachomatis was found on the McCoy cell culture. Within 3 months of observation, microbiologically verified persistence of chlamydia after treatment persisted in 2 women (2. 78%).

78%).

Compared with the data obtained in the control group, there are significant differences in the incidence of obstetric and gynecological pathology during pregnancy in chlamydia (Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1. Complications of pregnancy in women of the control group and with chlamydial infection |

Complications of the gestational process associated with chlamydial infection were considered the threat of abortion, premature birth, fetoplacental insufficiency and fetal growth retardation, echographic markers of intrauterine infection (changes in echogenicity of the placenta, polyhydramnios and oligohydramnios, structural defects in the development of the fetus). In addition, a high frequency of combination of chlamydia with pathology of the cervix and urinary tract infection was noted.

After treatment with Vilprafen according to the indicated scheme (1500 mg/day for 10 days), a significant decrease in the incidence of complications of pregnancy, childbirth, general and infectious morbidity in newborns was registered (Fig. 2).

2).

| Fig. 2. The frequency of complications of pregnancy, childbirth and neonatal morbidity after treatment of chlamydia with Vilprafen |

The use of Vilprafen for the treatment of urogenital chlamydia during pregnancy, including after ineffective therapy with other antibiotics, leads to microbiological cure in 97.22% of patients. It is important to note that such high treatment success rates were achieved in the group of women with recurrent and chronic chlamydial infection. In addition, the use of josamycin is possible regardless of the gestational age.

There were no reported refusals of the recommended treatment. Adverse events while taking Vilprafen in the form of nausea were noted by 2 pregnant women and in the form of "heaviness" in the abdomen - by 1 woman (4.17% in total).

A feature of chronic chlamydial infection is poor symptoms or the complete absence of clinical manifestations of the disease, which leads to late diagnosis. At the same time, irrational antibiotic therapy not only causes the emergence of pathogen resistance, but also leads to a late start of adequate treatment. The high frequency of infection-associated complications requires highly informative methods for diagnosing chlamydia and the appointment of etiotropic therapy in the complex treatment of pregnant women.

At the same time, irrational antibiotic therapy not only causes the emergence of pathogen resistance, but also leads to a late start of adequate treatment. The high frequency of infection-associated complications requires highly informative methods for diagnosing chlamydia and the appointment of etiotropic therapy in the complex treatment of pregnant women.

The frequency of perinatal infections after using Vilprafen during pregnancy decreased by 2.4 times. There were no cases of chlamydial pneumonia and generalized infection in newborns whose mothers received josamycin therapy.

Thus, in pregnant women with STIs, echographic markers of infection are found in almost 30%. The frequency of placental insufficiency in these women increases by almost 2 times. Hemodynamic disorders in pregnant women with ascending infection of the fetus are mainly recorded in the fetal-placental link of blood circulation.

Since chronic and recurrent chlamydial infection leads to changes in the fetoplacental complex, it is necessary to diagnose chlamydial lesions in a timely manner and carry out complex therapy, taking into account the extent of the process, gestational age and the presence of concomitant complications.