Pre eclampsia care plan

6 Preeclampsia & Gestational Hypertensive Disorders Nursing Care Plans

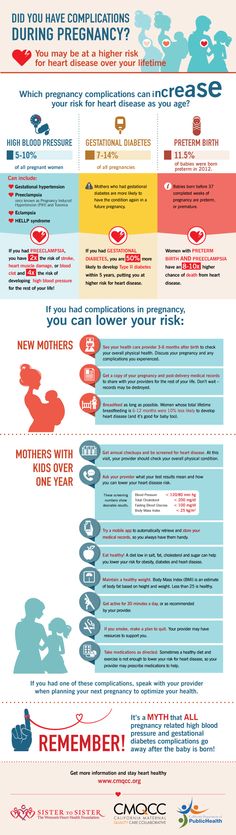

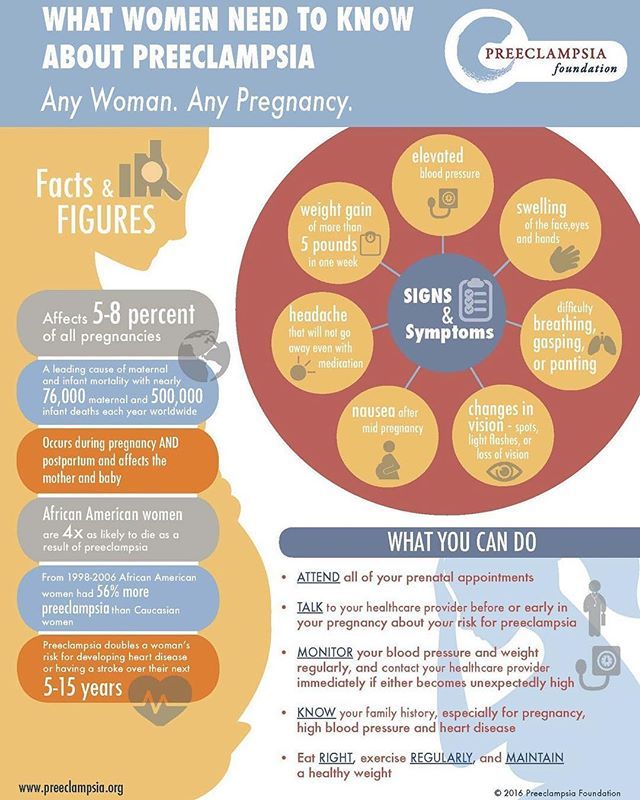

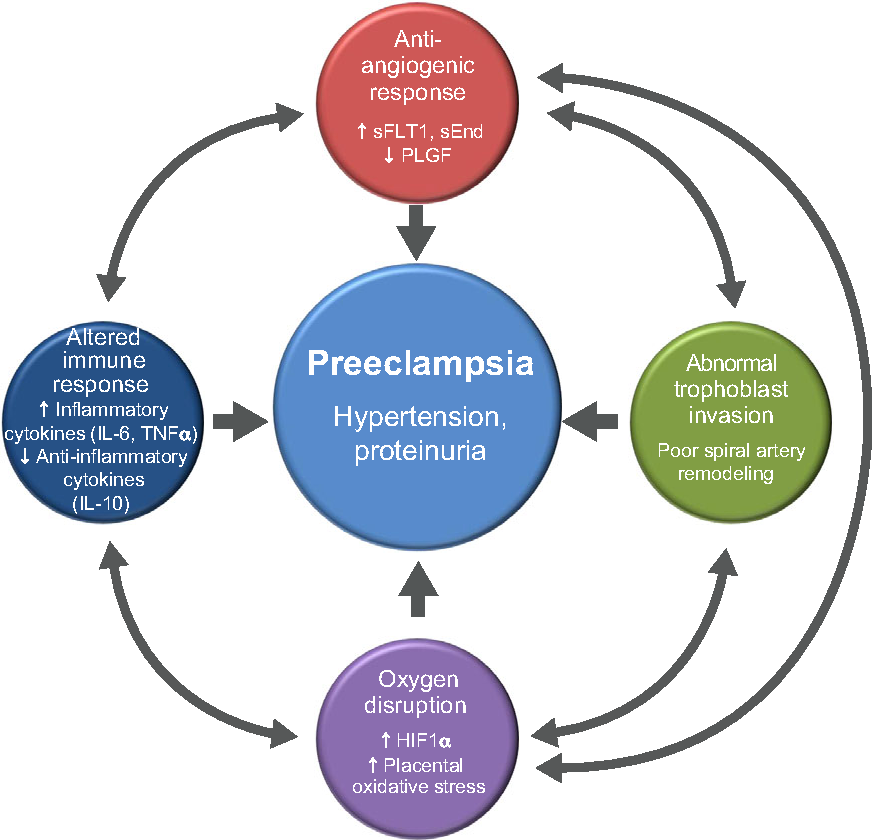

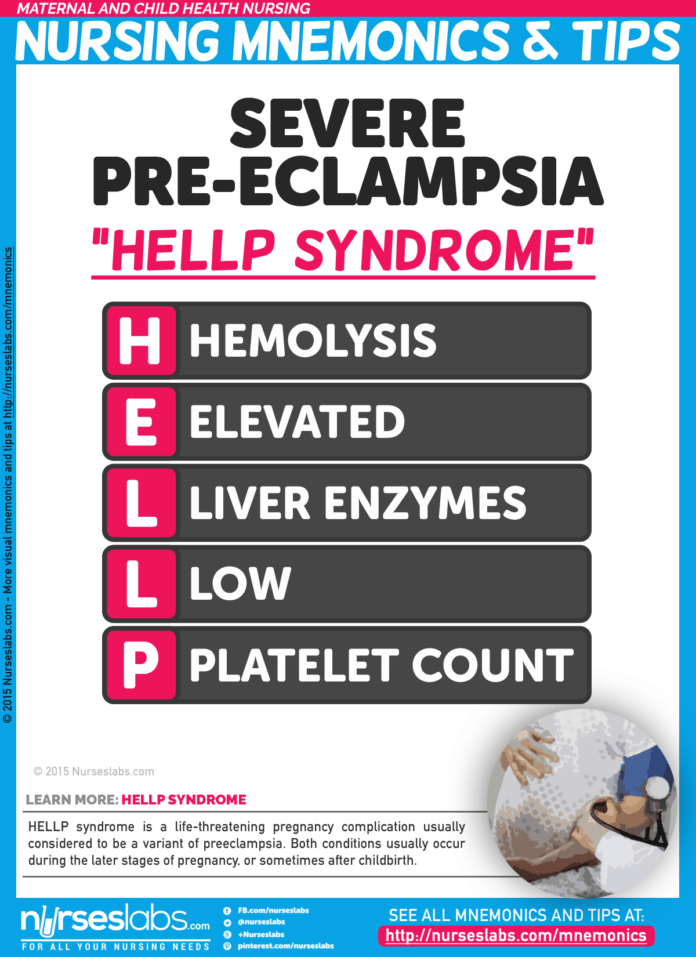

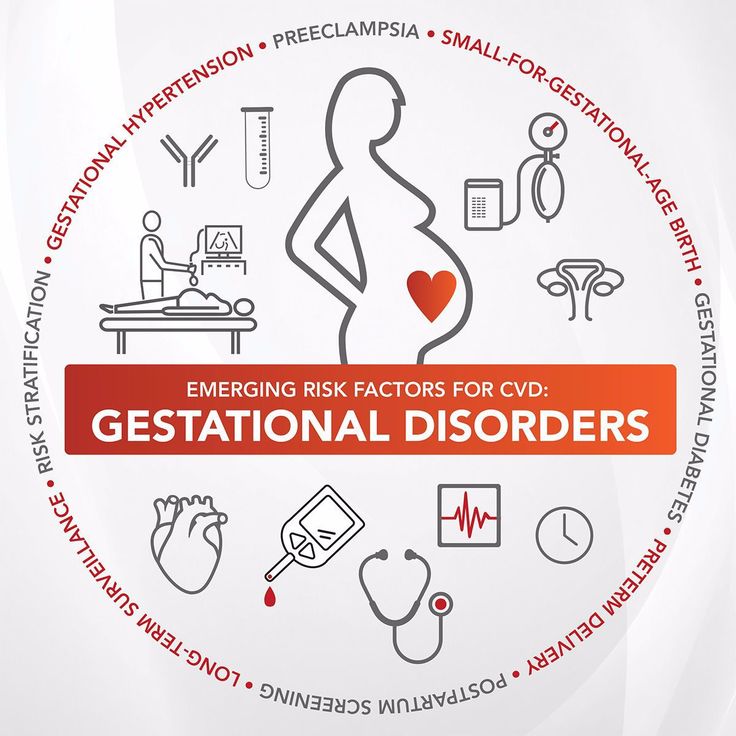

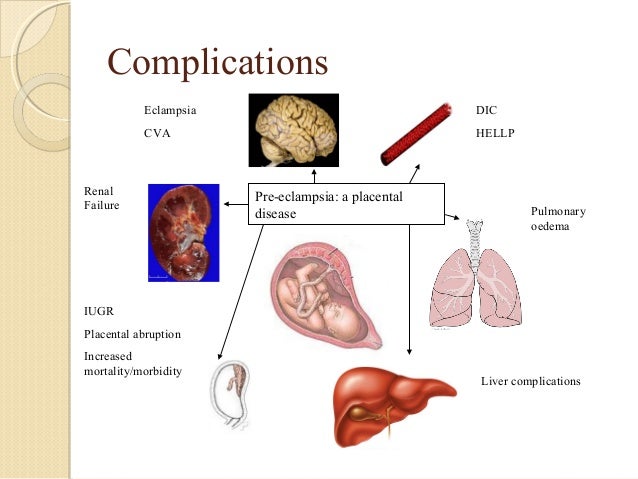

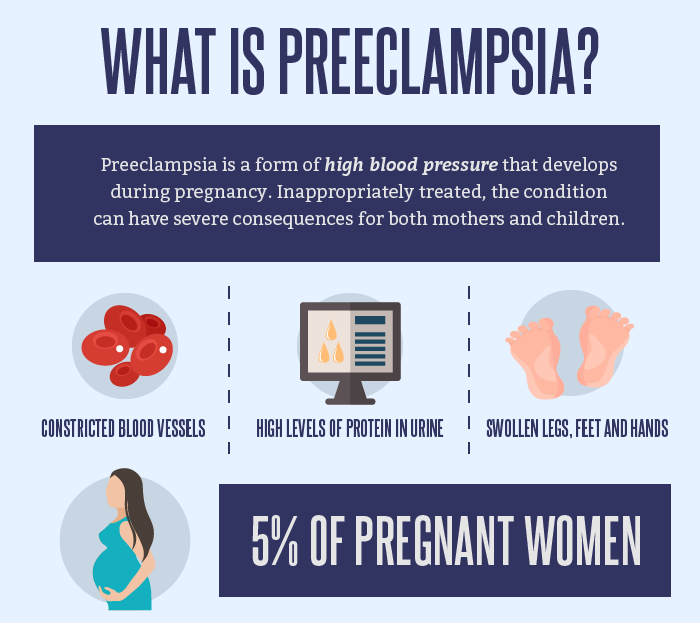

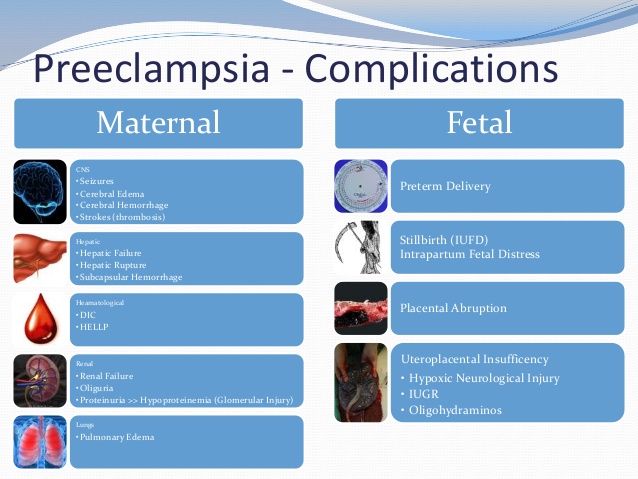

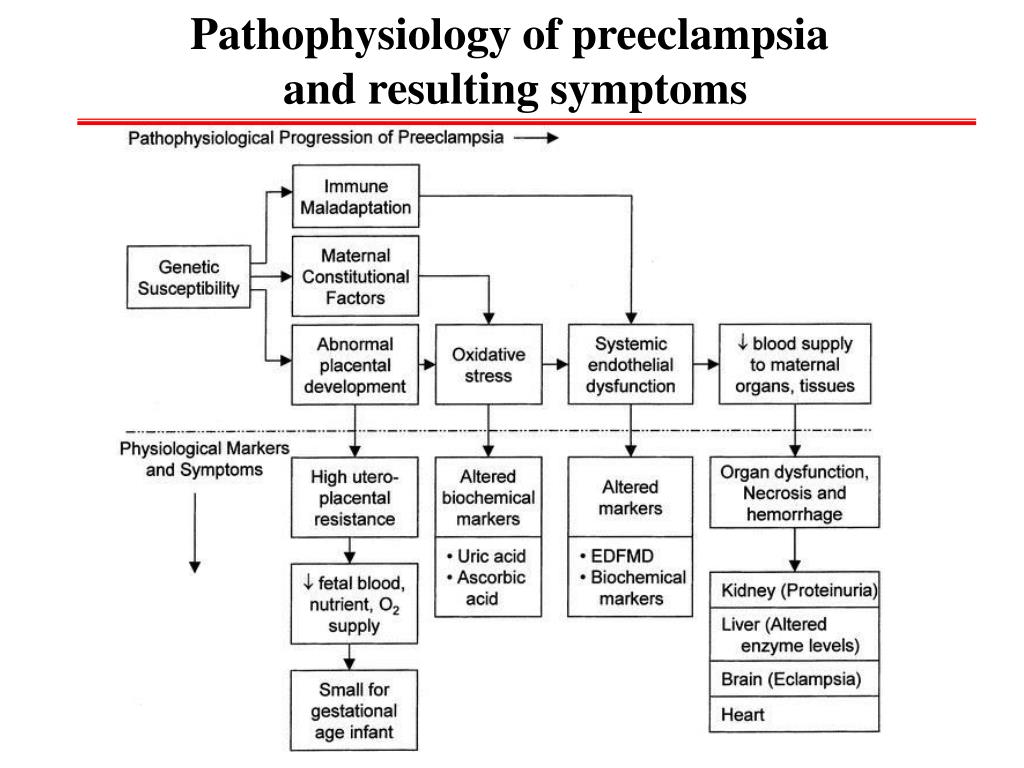

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (also known as pregnancy-associated hypertensive disorders, pregnancy induced hypertension) are the most common complications that occur during pregnancy and are a major cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. These disorders include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, chronic hypertension, and chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia. If left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to a life-threatening complication called HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome. It is estimated that preeclampsia alone complicates 2-8% of pregnancies globally.

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy include five categories of hypertension and are defined as such by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG):

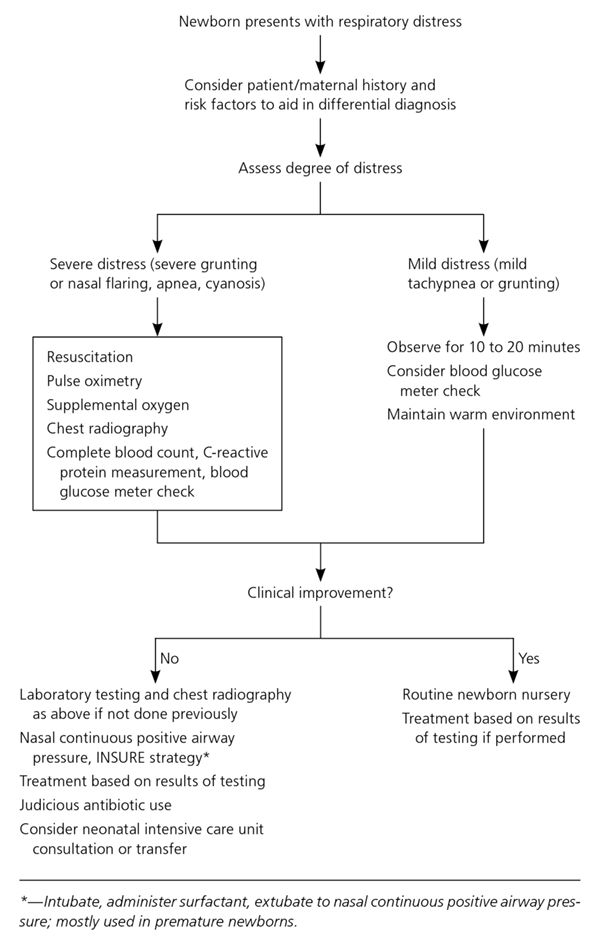

Nursing care planning and management for pregnant clients with hypertensive disorders or preeclampsia involve early detection, thorough assessment, and prompt treatment of preeclampsia. Another priority is to ensure the mother’s safety and deliver a healthy newborn as close to a full term as possible.

Here are six nursing diagnoses for your nursing care plans for pregnant patients with hypertensive disorders, focusing on managing clients with preeclampsia.

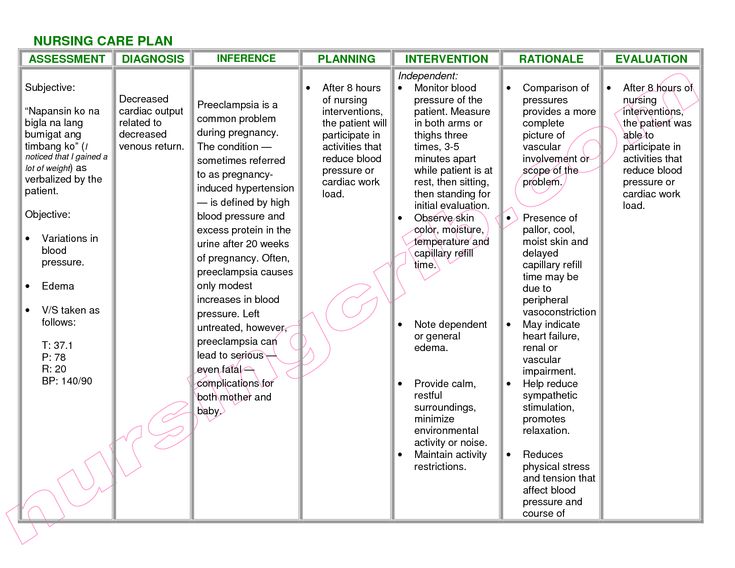

Decreased Cardiac OutputA decrease in circulating blood volume due to the shifting of fluid from the intravascular to the interstitial spaces occurs in a pregnant client with a hypertensive disorder due to the decrease of the circulating blood volume and the total vascular volume and an increase in the systemic vascular resistance, the heart rate decreases as well as the stroke volume. These mechanisms lead to a decrease in cardiac output seen among clients with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy.

Nursing Diagnosis- Decreased Cardiac Output

- Decreased venous return

- Increased systemic vascular resistance

- Change in blood pressure/hemodynamic readings

- Diminished peripheral pulses

- Tachycardia

- Edema

- Shortness of breath/dyspnea

- Alteration in mental status

- Decreased urine output

- The client remains normotensive throughout the remainder of the pregnancy.

- The client reports absence and/or decreased episodes of dyspnea.

- The client alters activity level as the condition warrants.

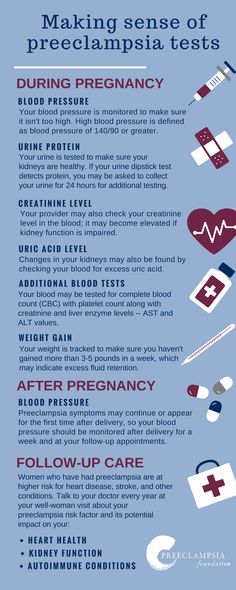

1. Assess blood pressure and pulse every one (1) hour or as indicated.

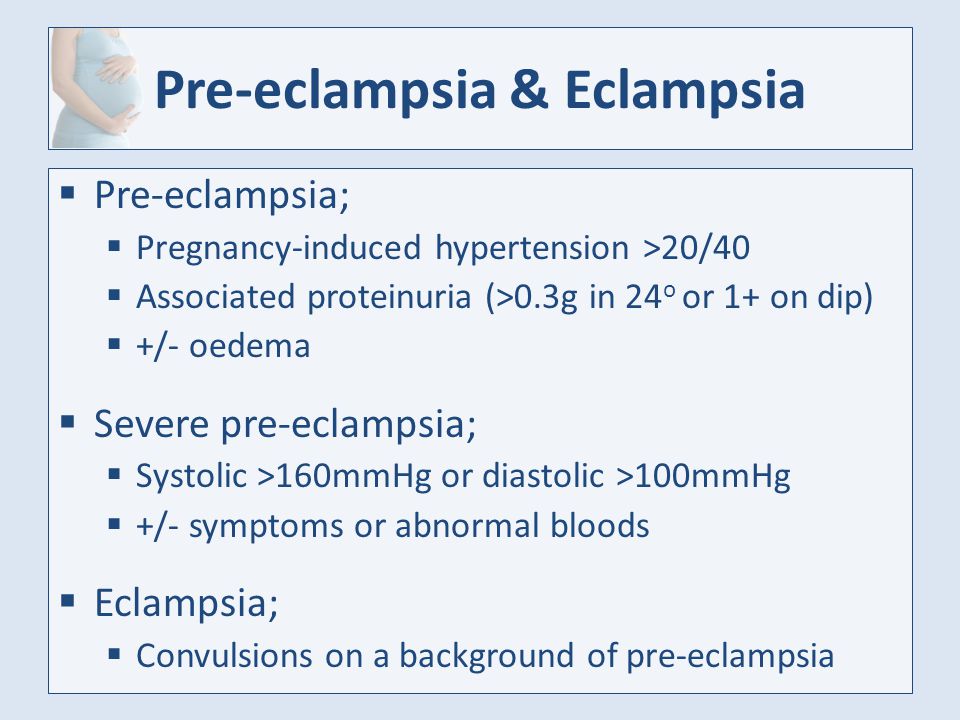

Accurate measurement of blood pressure is essential for the early detection of hypertensive disorders. Hypertension is defined as a systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mm Hg. Blood pressure may be elevated because of the increase in systemic vascular resistance whereas decreased cardiac output may also be reflected by diminished peripheral pulses. Rising blood pressure indicates the progression of preeclampsia. Use a consistent and standardized method when taking blood pressure measurements to maintain accuracy.

2. Assess the mean arterial pressure (MAP) at 11-13 and 20-24 weeks gestation. A pressure of 90 mm Hg is considered predictive of preeclampsia.

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) is the average arterial pressure throughout one cardiac cycle and is influenced by cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance. MAP prediction is best when measured during 11-13 weeks and at 20-24 weeks than at only one of these gestational ranges. MAP is increased from the first trimester in pregnancies developing preeclampsia (Gallo et al., 2014). Women with early-onset preeclampsia have higher mean arterial blood pressure levels at 20 weeks of gestation (Mayrink et al., 2019).

3. Assess for crackles, wheezes, and dyspnea; note respiratory rate/effort. Note client snoring.

Pulmonary edema may transpire with modification in peripheral vascular resistance and a drop in plasma colloid osmotic pressure. Fluid from the intravascular spaces shifts to the interstitial spaces, depleting the circulating blood volume but overwhelming the important organs of the body, especially the lungs. Pregnancy-onset snoring may also be a risk factor for developing gestational hypertension and preeclampsia (O’Brien et al. , 2012).

, 2012).

4. Auscultate for the apical pulse and assess the client’s heart rate and rhythm.

Tachycardia may be present when the body compensates for the decrease in circulating volume that can hardly reach the peripheries and distant tissues.

5. Assess the client’s neurological status.

Decreased cardiac output can precipitate alternations in the sensorium due to inadequate cerebral perfusion. Neurologic complications associated with preeclampsia may also manifest. These symptoms include cerebral edema, hemorrhage, irritability, headaches, hyperreflexia, seizures.

6. Assess the client for visual disturbances.

Alteration in the sensorium may indicate inadequate cerebral perfusion secondary to decreased cardiac output. Vision changes are due to arteriolar vasospasms and decreased blood circulation to the retina. These symptoms may include dimming of vision, blind or dark spots in the visual speed, blurring of vision, double vision.

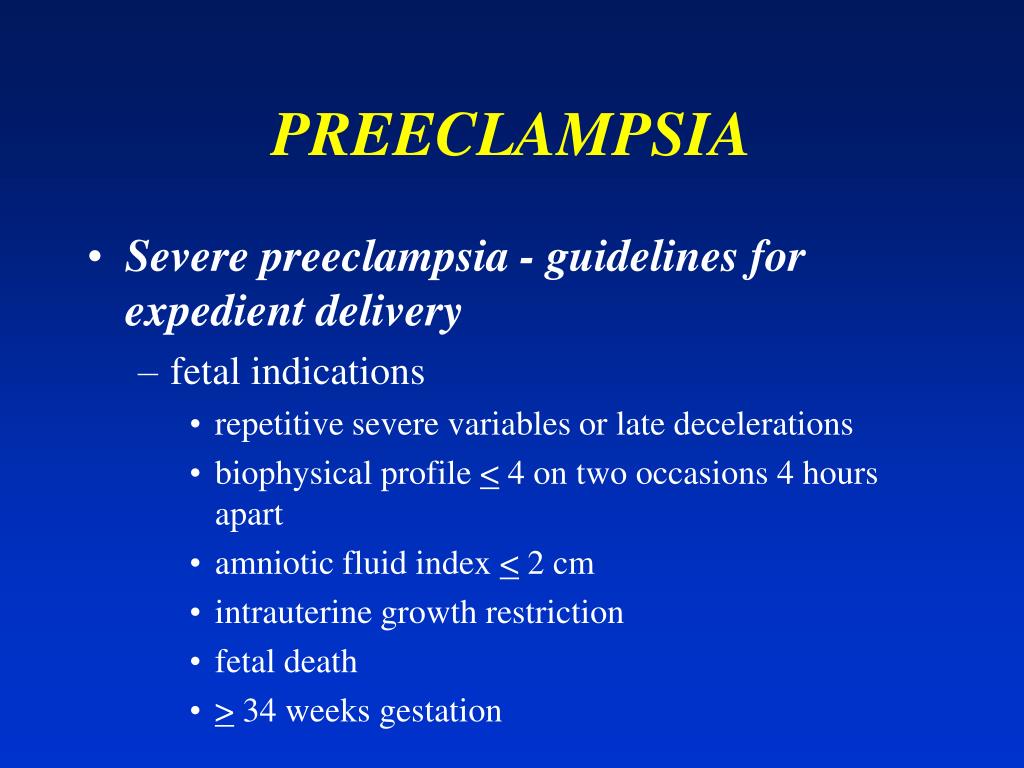

7. Assess the client for indications for an earlier delivery.

Worsening preeclampsia that may progress to eclampsia warrants the need for an emergency early delivery. The fetal blood supply can be cut off, resulting in fetal distress and ultimately fetal death if delivery is not hastened (Sinkey et al., 2020; Espinoza 2012). These symptoms include uncontrolled severe-range blood pressure, refractory headaches, upper abdominal pain, visual disturbances, stroke.

8. Monitor and measure the client’s urine output as per protocol. Maintain strict intake and output.

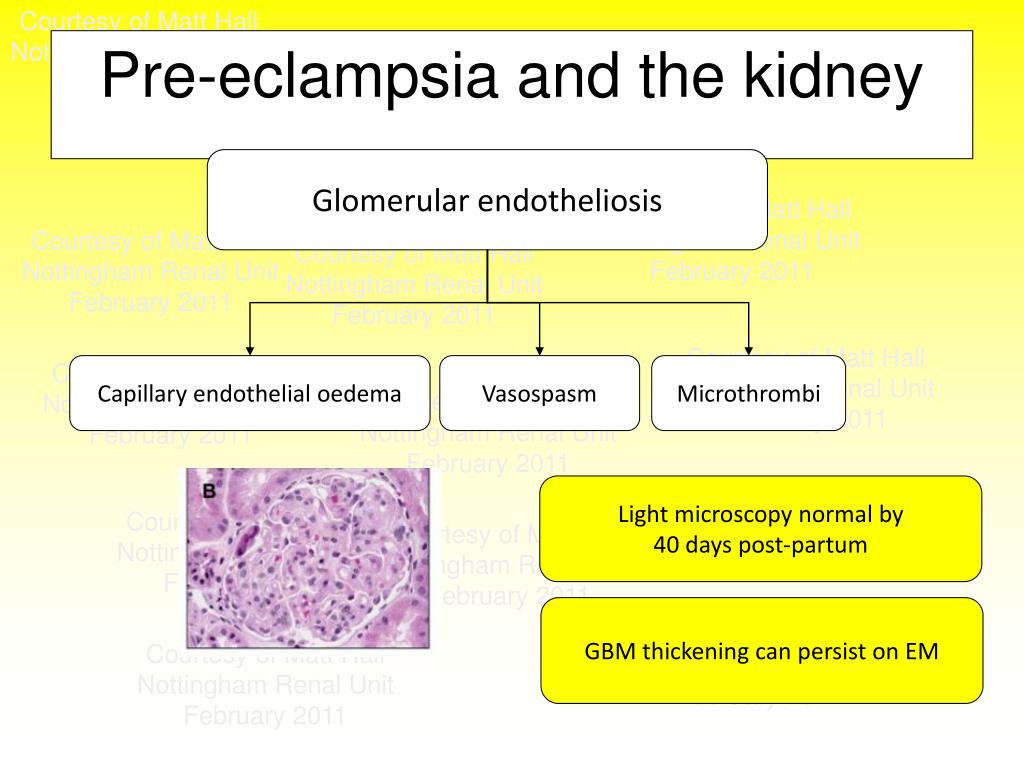

In preeclampsia, the kidneys respond to reduced cardiac output by retaining water and sodium. Intrarenal vasospasms cause oliguria in severe preeclampsia due to a reduction in glomerular filtration rate. Contraction of the intravascular space secondary to vasospasms worsens renal sodium and water retention (ACOG, 2020).

9. Monitor and measure the client’s 24-hour urine for proteinuria.

Proteinuria is ideally determined by the evaluation of a 24-hour urine collection. However, current guidelines state that massive proteinuria is not considered a severe feature of preeclampsia. Reduced kidney perfusion causes renal deterioration and damages glomerular endothelial cells allowing protein molecules to pass into the urine, causing proteinuria. In some instances where it may be difficult to collect a 24-hour urine sample, preeclampsia may be diagnosed as hypertension with either thrombocytopenia, renal insufficiency, impaired liver function, pulmonary edema.

1. Provide frequent rest periods with bed rest. Restrict activity rather than instituting complete bed rest.

Improves venous return, cardiac output, and renal-placental perfusion. Help the client understand the importance of reduced activity and frequent rest periods and plan ways to manage them. Activity diverts blood from the placenta, reducing the infant’s oxygen supply. Although frequently recommended by healthcare providers, no evidence has been found that complete bed rest improves pregnancy outcomes. Rather, prolonged bed rest can increase the risk of complications due to immobility (e.g., muscle atrophy, weight loss, cardiovascular deconditioning, psychologic stress, etc.). Therefore, restricted activity rather than complete bed rest is recommended (Ghulmiyyah et al., 2012).

Although frequently recommended by healthcare providers, no evidence has been found that complete bed rest improves pregnancy outcomes. Rather, prolonged bed rest can increase the risk of complications due to immobility (e.g., muscle atrophy, weight loss, cardiovascular deconditioning, psychologic stress, etc.). Therefore, restricted activity rather than complete bed rest is recommended (Ghulmiyyah et al., 2012).

2. Instruct the client to elevate legs when sitting or lying down.

Elevating the legs decreases venous stasis and may also reduce the incidence of thrombus and embolus formation in the client on bed rest.

3. Monitor the client’s BP and instruct monitoring of BP at home.

Monitor BP every 15 minutes during the critical phase and every 1 to 4 hours as the client’s condition improves. If the client is an outpatient, instruct both the client and a family member to monitor the BP two to four times per day in the same arm and the same position. A family member must be taught the technique to ensure accurate measurements. Rising blood pressure levels may indicate worsening preeclampsia.

A family member must be taught the technique to ensure accurate measurements. Rising blood pressure levels may indicate worsening preeclampsia.

4. Record and graph vital signs, especially BP and pulse.

The client with preeclampsia does not display the normal cardiovascular response to pregnancy (left ventricular hypertrophy, increased plasma volume, vascular relaxation with decreased peripheral resistance). Hypertension (the second manifestation of preeclampsia after edema) occurs due to increased sensitization to angiotensin II, which increases BP and promotes aldosterone release to increase sodium/water reabsorption from the renal tubules constricts blood vessels.

5. Monitor for invasive hemodynamic parameters such as cardiac output, as indicated.

Provides a precise picture of vascular changes and fluid volume. Prolonged vascular constriction, increased hemoconcentration, and fluid shifts decrease cardiac output.

6. Administer low-dose aspirin as indicated.

Administer low-dose aspirin as indicated.

When initiated before 16 weeks gestation, low-dose aspirin effectively prevents preeclampsia, severe preeclampsia, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction in patients with high-risk pregnancies (Fantasia, 2018; Xu et al., 2015). It is recommended that daily dose aspirin therapy be initiated late in the first trimester for women who have a history of early-onset preeclampsia and subsequent preterm birth at less than 34 weeks of gestation or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

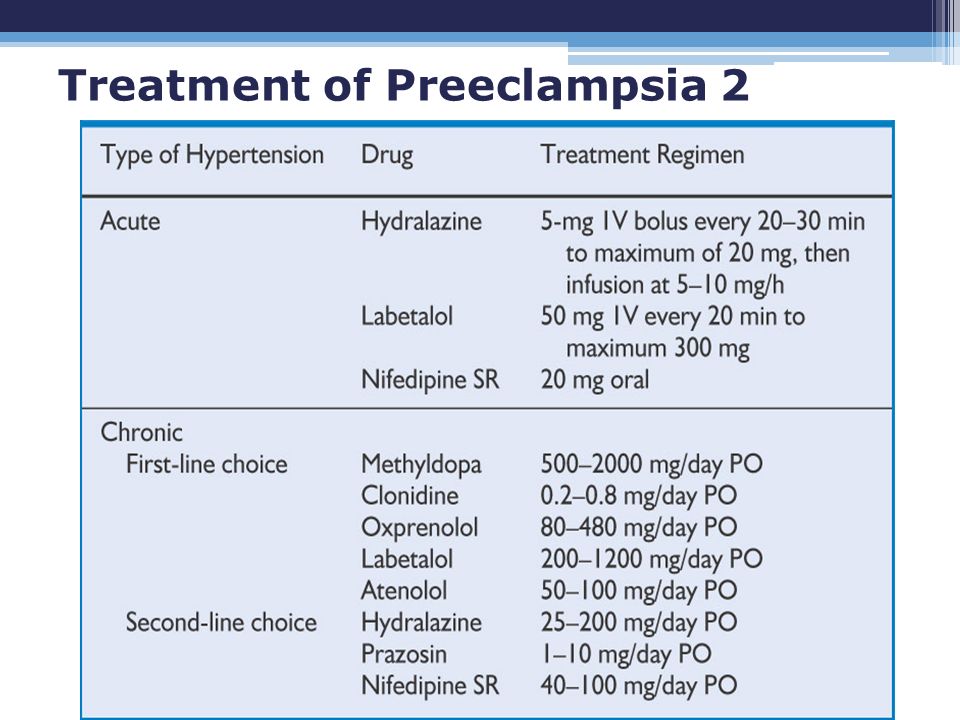

7. Administer antihypertensive medications as ordered. Observe for side effects of antihypertensive drugs.

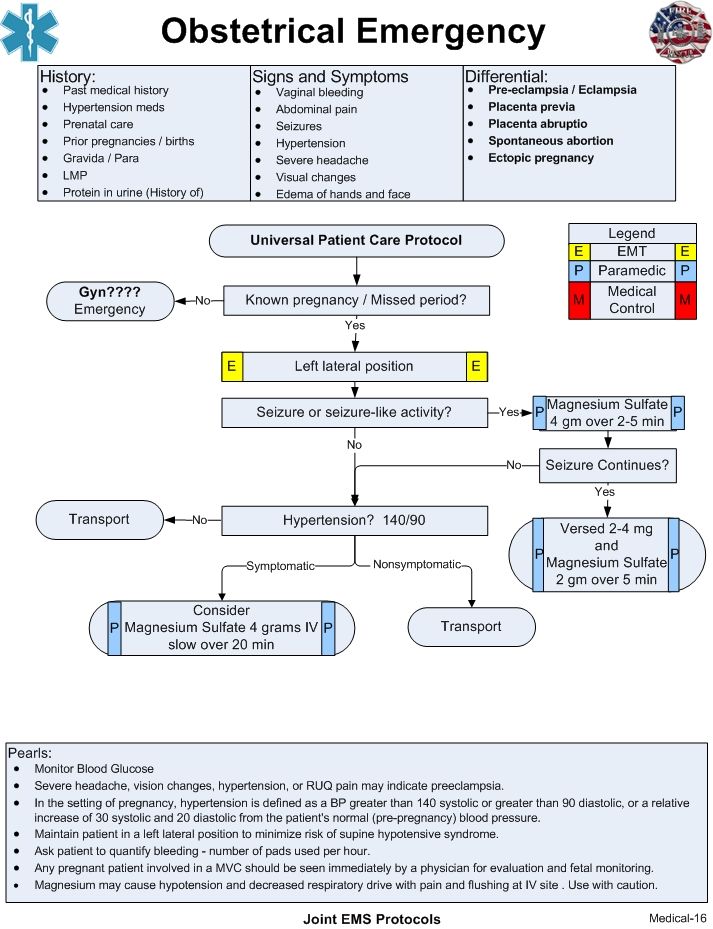

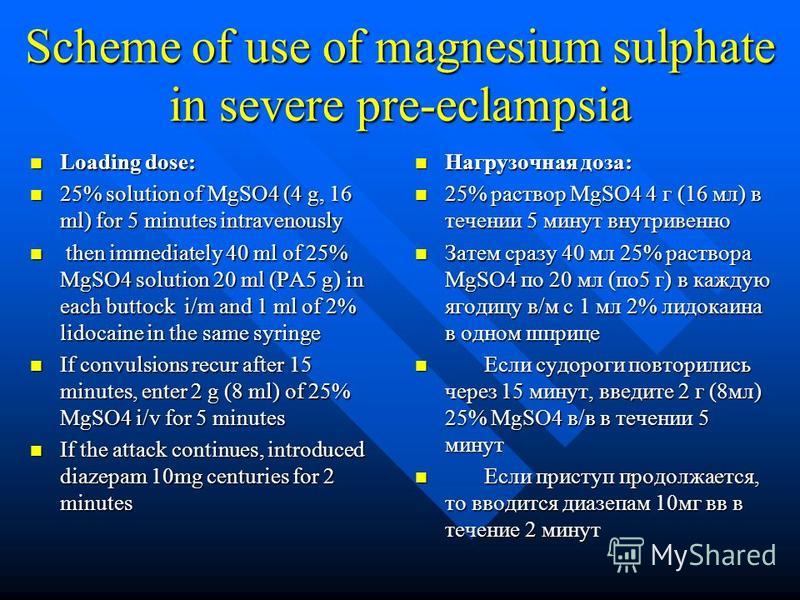

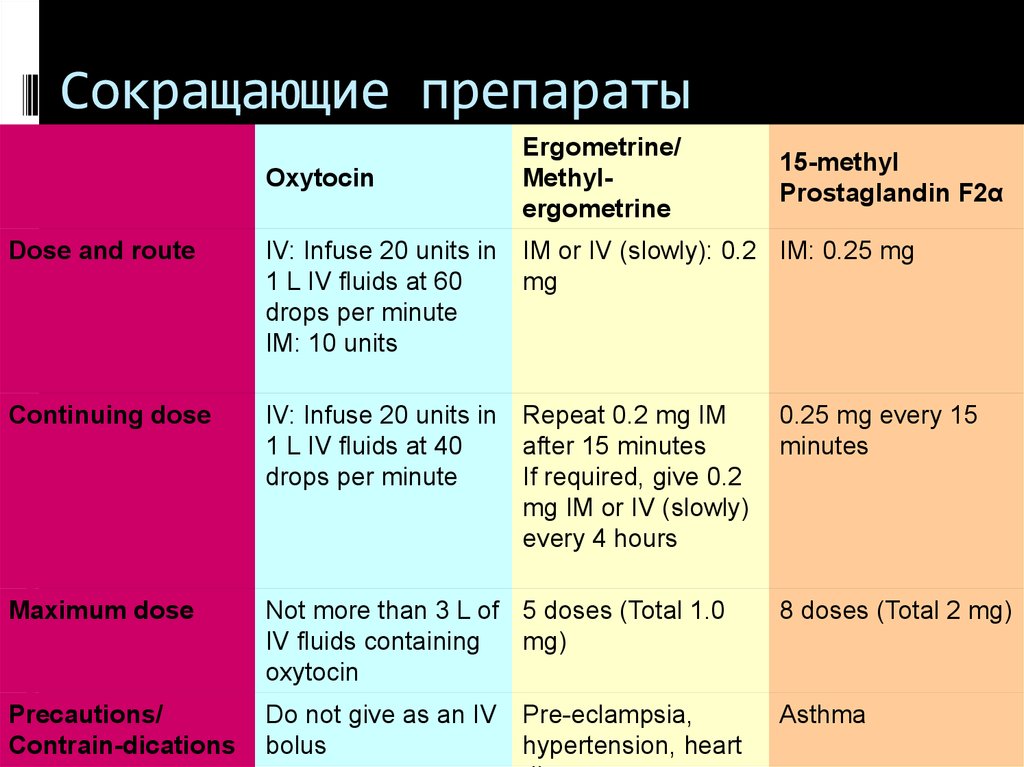

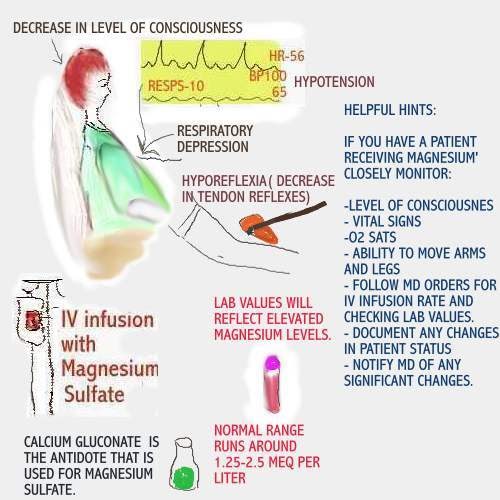

If blood pressure does not respond to conservative measures, short-term medication may be needed with other therapies (e.g., fluid replacement, magnesium sulfate). Antihypertensive treatment should be initiated as soon as reasonably possible for acute-onset severe hypertension that persists (ACOG, 2020). Antihypertensive drugs work directly on arterioles to promote relaxation of cardiovascular smooth muscles and help increase blood supply to the cerebrum, kidneys, uterus, and placenta (Lightstone, 2013). Intravenous hydralazine, or labetalol, and oral nifedipine are three agents commonly used to control hypertension in pregnancy.

Antihypertensive drugs work directly on arterioles to promote relaxation of cardiovascular smooth muscles and help increase blood supply to the cerebrum, kidneys, uterus, and placenta (Lightstone, 2013). Intravenous hydralazine, or labetalol, and oral nifedipine are three agents commonly used to control hypertension in pregnancy.

- 7.1. Hydralazine (Apresoline, Neopresol).

Administered intravenously, hydralazine reduces blood pressure by relaxing the smooth muscles. The vasodilating effect reduces peripheral vascular resistance. Check BP every minute for 5 mins then every 5 mins for 30 mins. - 7.2. Labetalol Hydrochloride (Normodyne, Trandate).

Given intravenously, labetalol is an alpha- and beta-blocker that decreases peripheral vascular resistance without significant change in cardiac output or causing tachycardia. Contraindicated with asthma and congestive heart failure. Closely monitor blood pressure after administration.

- 7.3. Methyldopa (Aldomet).

Interferes with chemical neurotransmission to reduce peripheral vascular resistance. Can cause CNS sedation, sleepiness, postural hypotension. - 7.4. Nifedipine (Adalat).

Calcium channel blocker that dilates arterioles and decreases systemic vascular resistance by relaxing arterial smooth muscle. Nifedipine can potentiate the CNS effects of magnesium sulfate. Closely monitor blood pressure after administration. - 7.5. Sodium Nitroprusside (Nitropress).

Used in rare scenarios where other antihypertensive agents have failed to control blood pressure.

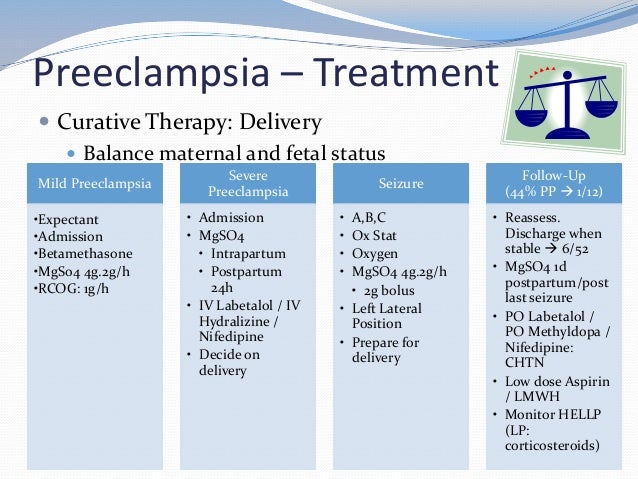

8. Prepare for the birth of fetus by cesarean delivery, labor when severe preeclamptic or eclamptic condition is stabilized, but vaginal delivery is not feasible.

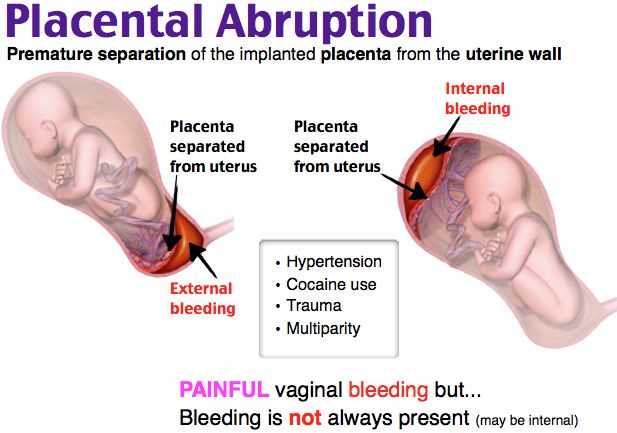

If conservative treatment is ineffective and labor induction is ruled out, then surgical procedure is the only means of halting the hypertensive problems. Delivery of the fetus is the cure for preeclampsia. If preeclampsia is severe, the fetus is often in greater danger from being in the uterus because its oxygen and nutritional supply may be cut off or its growth can be restricted. Fetal death sometimes can occur.

Delivery of the fetus is the cure for preeclampsia. If preeclampsia is severe, the fetus is often in greater danger from being in the uterus because its oxygen and nutritional supply may be cut off or its growth can be restricted. Fetal death sometimes can occur.

Disclosure: Included below are affiliate links from Amazon at no additional cost from you. We may earn a small commission from your purchase. For more information, check out our privacy policy.

References and sources for this nursing care plan for hypertensive disorders in pregnancy.

Preeclampsia Nursing Diagnosis & Care Plan

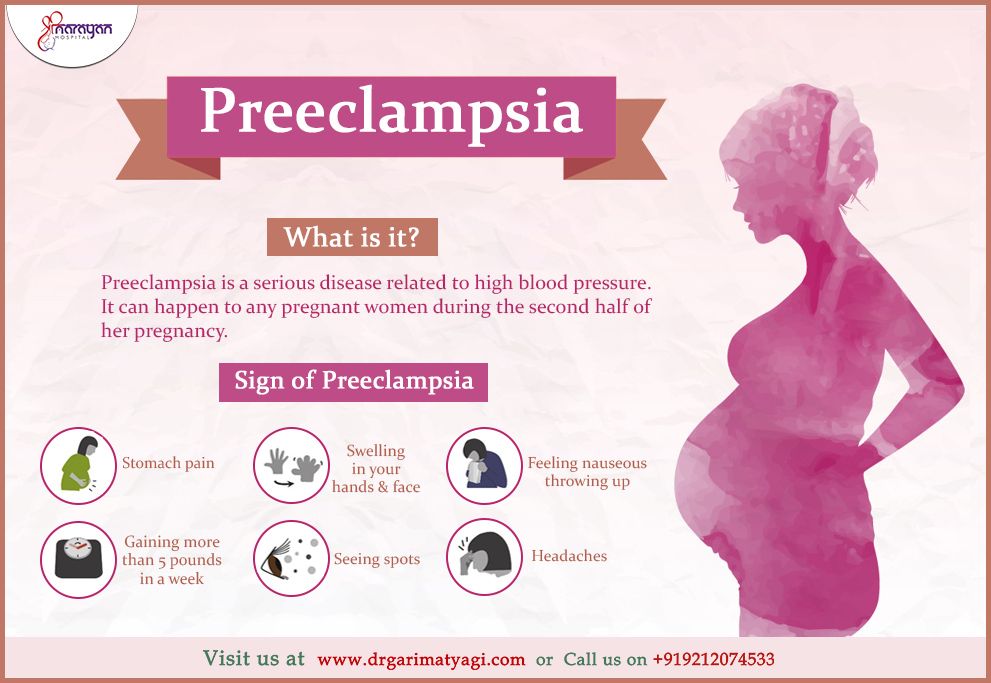

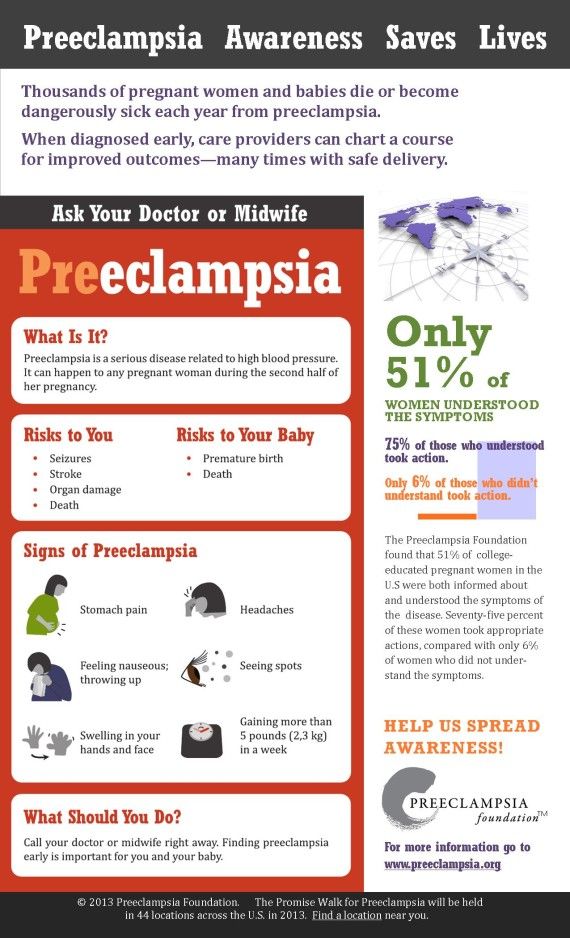

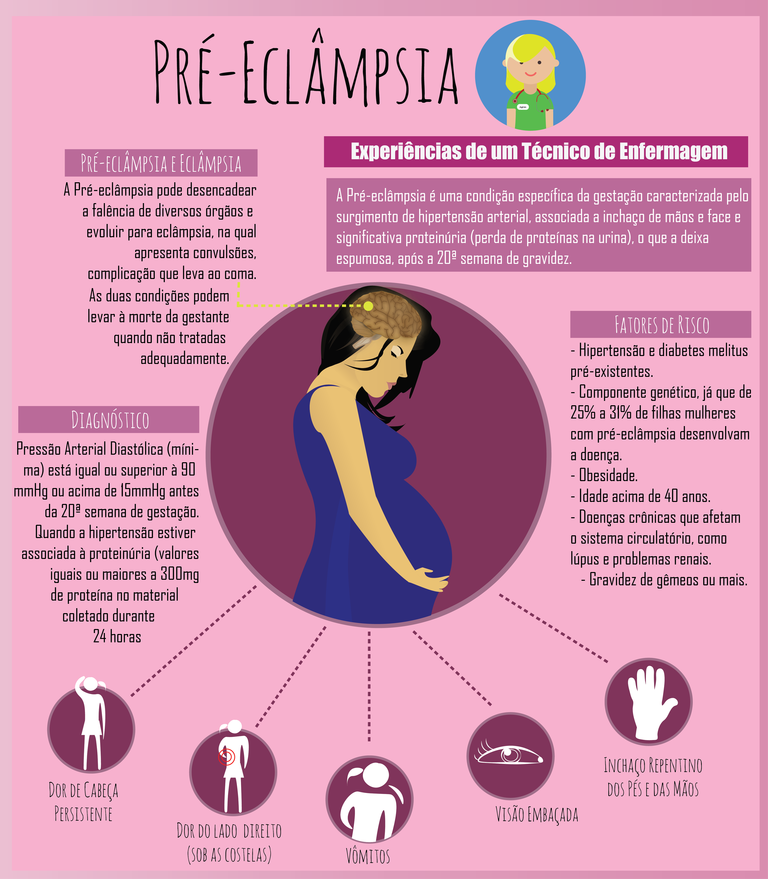

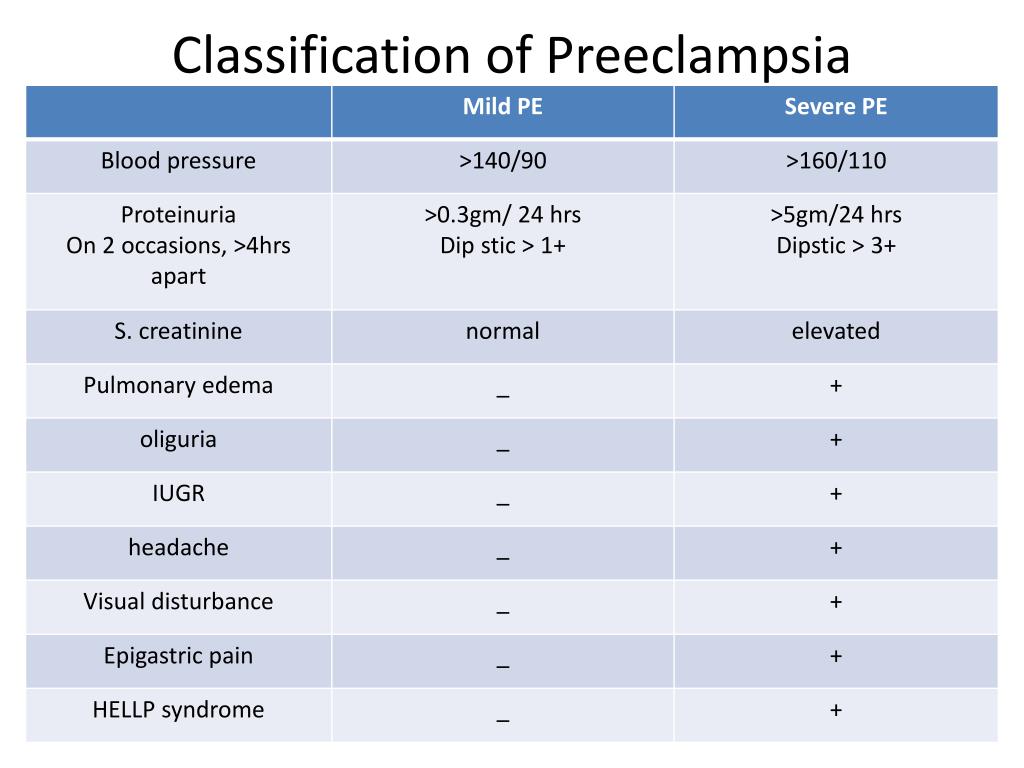

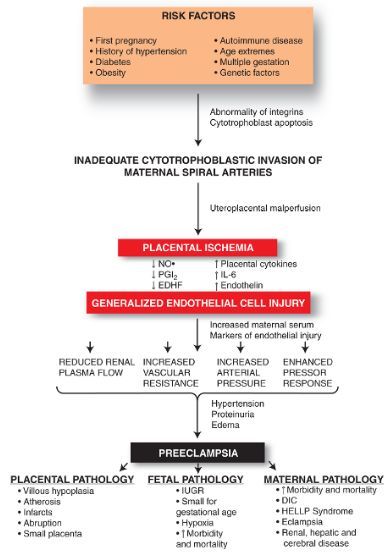

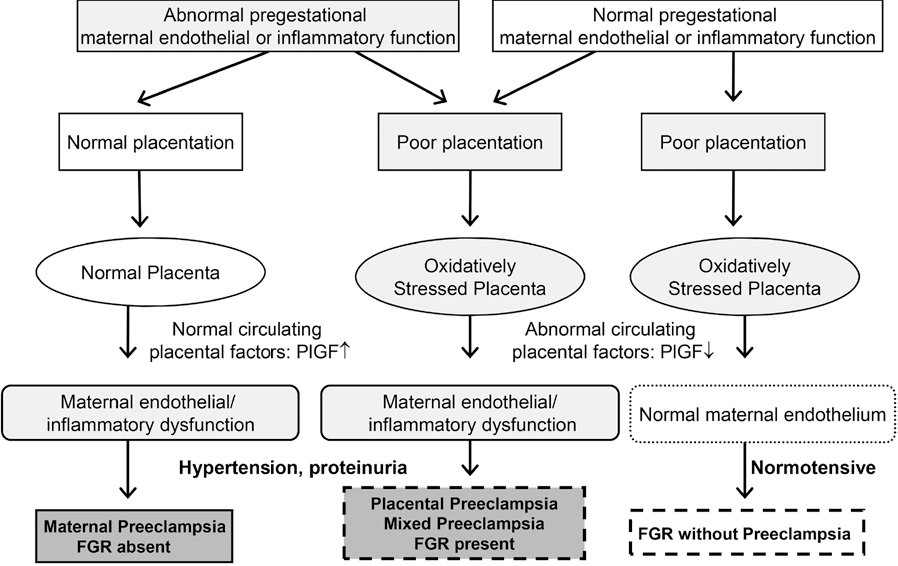

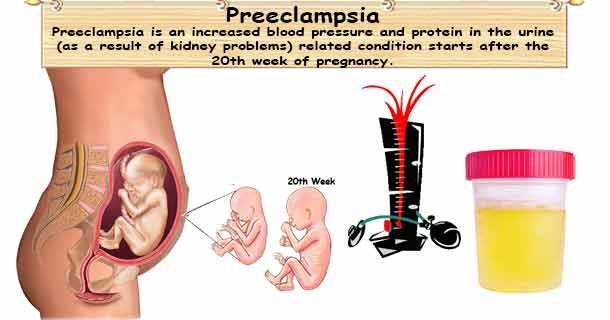

Preeclampsia is a serious complication that occurs during pregnancy and affects 5-7% of pregnancies worldwide. It is characterized by high blood pressure and protein in the urine (proteinuria). The exact cause is unknown though research shows genetics or blood vessel abnormalities with the placenta could be a potential cause.

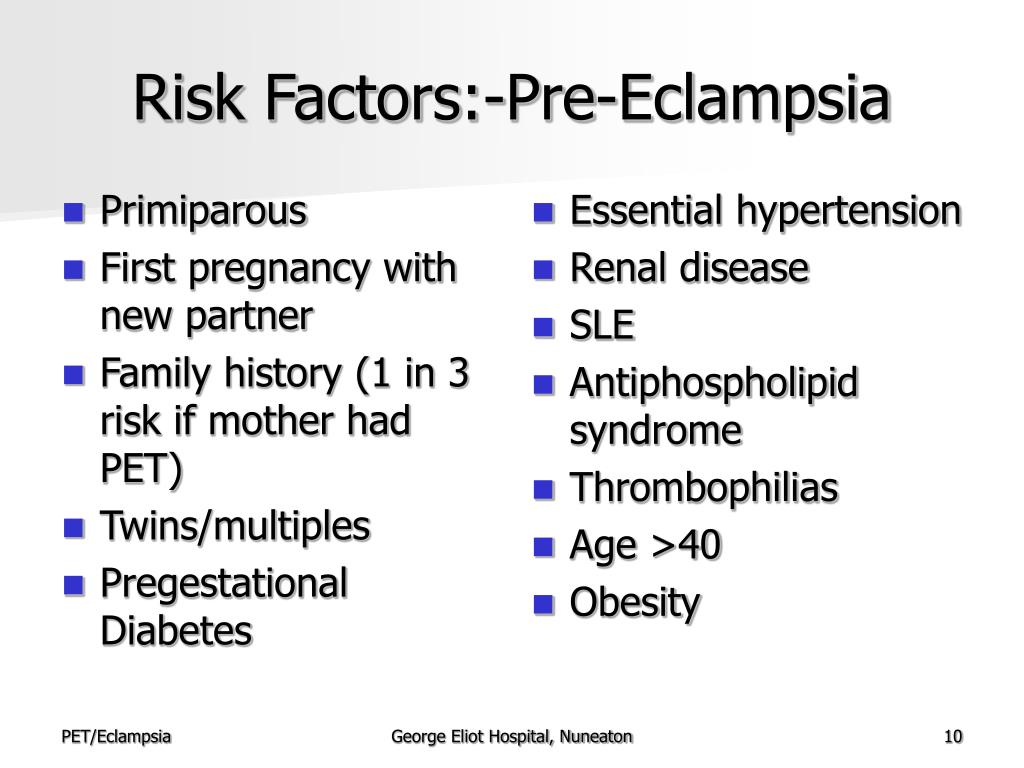

The following risk factors increase the chance of a woman developing preeclampsia:

- Multiple-gestation pregnancy

- Obesity

- Family history of preeclampsia

- Women giving birth for the first time

- Women younger than 20 years of age or older than 40 years of age

- Overproduction of amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios)

- Underlying diseases like hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, and autoimmune disorders

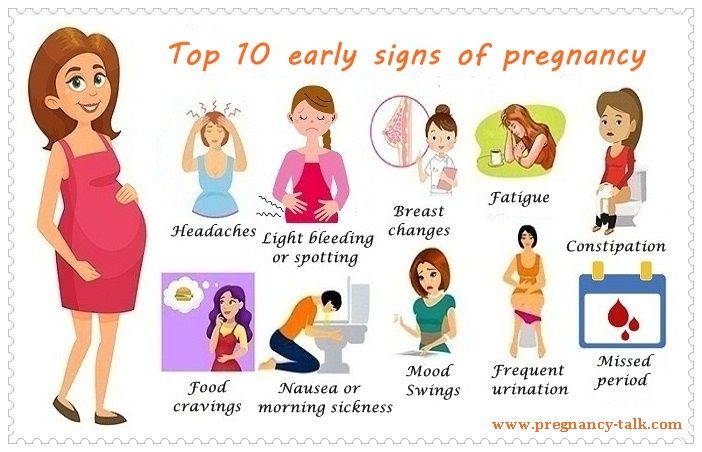

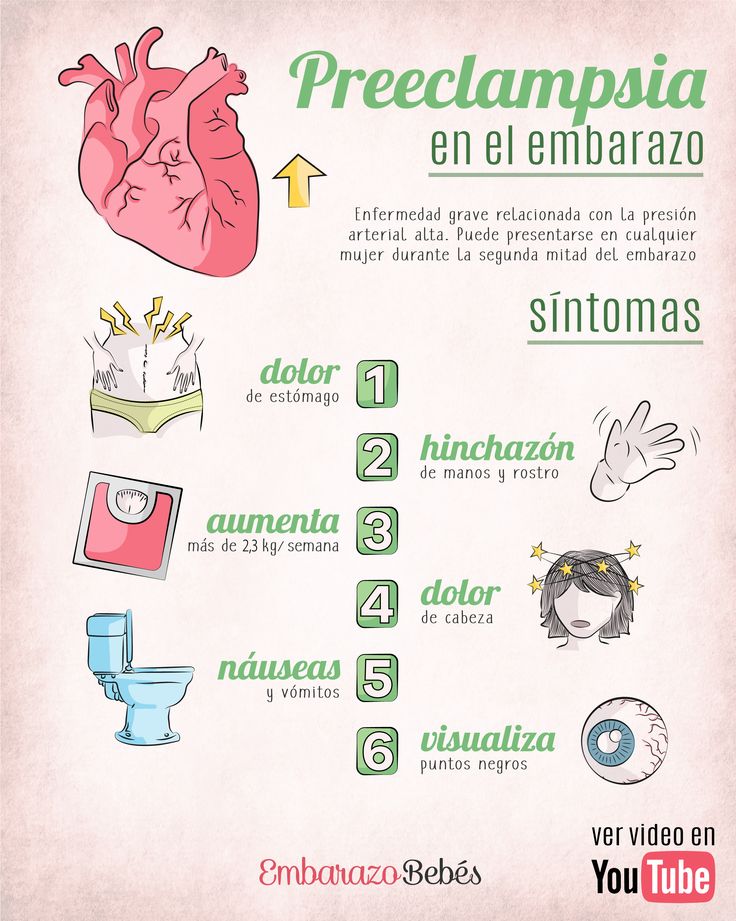

Hypertension, proteinuria, and edema are the classic triad symptoms of preeclampsia. Other symptoms include:

- Constant headaches

- Vision abnormalities

- Shortness of breath

- Epigastric pain

- Fluctuations in fetal heart rate

- Vaginal bleeding

Preeclampsia, if untreated, can hinder the baby’s growth and may develop into eclampsia. Eclampsia is a severe complication of preeclampsia that can lead to seizures.

The only way to treat preeclampsia is to deliver the baby. After delivery, preeclampsia usually resolves within days to weeks.

After delivery, preeclampsia usually resolves within days to weeks.

The Nursing Process

Nurses can first identify high-risk pregnancies to prevent preeclampsia. Focus on a thorough nursing assessment, education, and antenatal care.

The majority of cases are avoidable. Interventions include:

- Monitoring the patient’s blood pressure and symptoms

- Stress management

- Weight management

- Proper nutrition

- Monitoring fetal heart rate (FHR)

- Regular OB/GYN follow-ups and prenatal care

Nursing Care Plans Related to Preeclampsia

Risk for Imbalanced Fluid Volume Care Plan

Risk for imbalanced fluid volume associated with preeclampsia is caused by fluid shifts which can lead to overloading organs and tissues.

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Imbalanced Fluid Volume

Related to:

- Plasma protein loss

- Decreased osmotic pressure

- Fluid shifting out of the vascular space

- Narrowing of the blood vessels

- Highly concentrated blood (Hemoconcentration)

- Elevated blood flow resistance

- Body cell degeneration (for pregnant mothers of older age)

- Decreased kidney filtration

- Sodium retention

As evidenced by:

A risk diagnosis is not evidenced by signs and symptoms as the problem has not yet occurred. Nursing interventions are aimed at prevention.

Nursing interventions are aimed at prevention.

Expected outcomes:

- Patient will be able to maintain adequate fluid volume as evidenced by blood pressure within normal limits

- Patient will be able to demonstrate efficient fluid intake and output

- Patient will remain free from generalized or pulmonary edema

Imbalanced Fluid Volume Assessment

1. Monitor blood pressure.

High blood pressure during pregnancy causes a concern for preeclampsia. Increased blood pressure may cause the heart to have to work harder due to the additional fluid in the body.

2. Assess for edema, proteinuria, and weight gain.

Proteinuria, edema, and weight gain are symptoms of preeclampsia. Protein in the urine (proteinuria) occurs from impaired renal filtration. Weight gain is likely related to fluid retention.

Note the following symptoms:

- Proteinuria of 1+ to 2+ on a random sample

- Minor facial or upper extremity edema

- Weight gain of more than 2 pounds per week in the second trimester and less than 1 pound per week in the third trimester

3. Monitor fetal well-being and status.

Monitor fetal well-being and status.

Preeclampsia is a significant factor in fetal death. If fluid is not balanced, the fetus is at higher risk of hypoxia and growth retardation.

Imbalanced Fluid Volume Interventions

1. Manage preeclampsia.

Collaborate with the healthcare team in treating preeclampsia to manage symptoms of fluid volume imbalance and prevent further complications.

2. Administer fluids.

IV fluids are administered to expand the intravascular volume. Care must be taken to not worsen or cause pulmonary edema.

3. Instruct on diet recommendations.

Limiting sodium and taking calcium, magnesium, and potassium supplements prevent the progression of edema and hypertension in preeclampsia.

4. Monitor intake and output.

Oliguria or reduced urine output can signal decreased kidney function from poor circulatory blood volume.

Decreased Cardiac Output Care Plan

Decreased cardiac output associated with preeclampsia can be caused by increased cardiac demands and decreased blood supply.

Nursing Diagnosis: Decreased Cardiac Output

Related to:

- Hypovolemia

- Decreased venous return

- Increased systemic vascular resistance

As evidenced by:

- Alterations in blood pressure

- Alterations in hemodynamic readings

- Edema

- Dyspnea

- Alterations in mental status

Expected outcomes:

- Patient will be able to maintain adequate blood pressure within acceptable limits

Decreased Cardiac Output Assessment

1. Assess the patient’s blood pressure.

During pregnancy, hypertension is defined as blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg. Preeclampsia is diagnosed with new onset hypertension with proteinuria after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

2. Assess for indications of poor cardiac function and impending heart failure.

The nurse can assess for the following symptoms:

- Excessive fatigue

- Intolerance to exertion

- Sudden or rapid weight gain

- Edema in the extremities

- Progressive or worsening shortness of breath

4. Assess the patient’s platelet count.

In preeclamptic women, a low platelet count is linked to a higher risk of abnormal coagulation and decreased cardiac output.

5. Assess for fetal growth.

Preeclampsia reduces cardiac output and can affect the arteries that provide blood to the placenta. The fetus may not get enough oxygen or nutrients which may result in fetal growth restriction.

Decreased Cardiac Output Interventions

1. Position the patient comfortably on the left side-lying position.

Left side-lying promotes adequate circulation. This position makes it easier for nutrient-rich blood to flow from the heart to the placenta to support the fetus.

2. Administer oxygen as prescribed.

Increase the amount of oxygen available for heart function which will increase the blood supply to the placenta and fetus.

3. Administer antihypertensives.

Cardiac medications should be administered to reduce hypertension with precautions that are safe for the mother and the fetus.

4. Restrict fluids as ordered.

If there is the presence of edema and cardiopulmonary congestion, restrict fluid intake as ordered.

6. Encourage reduced activity.

Rest periods and reduced activity is recommended. Physical activity diverts blood away from the placenta. Complete bed rest is not necessary.

7. Prepare for cesarean section.

If complications of preeclampsia due to decreased cardiac output are present, an emergency cesarean section is performed. This is to prevent maternal and fetal death.

Deficient Knowledge Care Plan

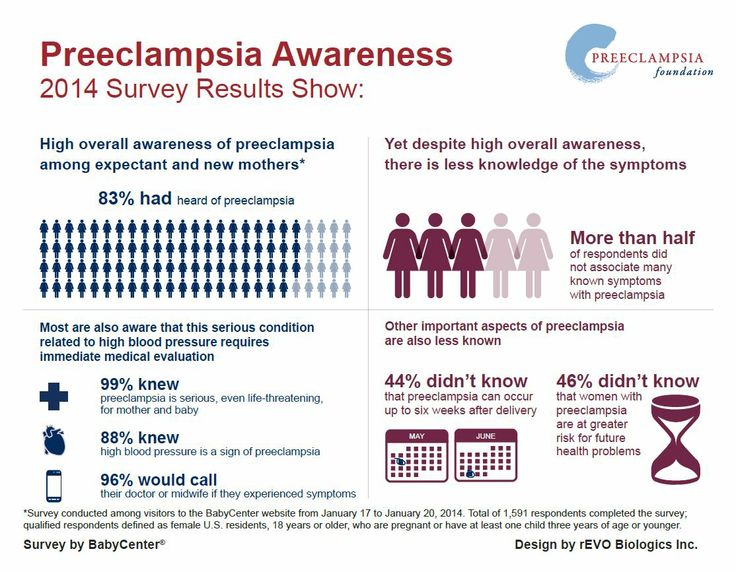

Deficient knowledge associated with preeclampsia can result in delayed recognition and treatment and poorer outcomes.

Nursing Diagnosis: Deficient Knowledge

Related to:

- Pathophysiology of preeclampsia

- Management of preeclampsia

- Risk factors for preeclampsia

- Self-care and nutritional needs of preeclampsia

- Complications of preeclampsia

- Lack of exposure to preeclampsia

- Inaccurate information about preeclampsia

- Misconceptions about preeclampsia

As evidenced by:

- Rapid progress of preeclampsia

- Development of preventable complications

- Unawareness of symptoms

- Inquiries about preeclampsia

- Misconceptions about preeclampsia

- Inaccurate or insufficient instructions in the prevention or management of preeclampsia

Expected outcomes:

- Patient will be able to verbalize understanding of preeclampsia and its management

- Patient will be able to verbalize possible complications and when to contact a healthcare provider

- Patient will be able to demonstrate behavior and lifestyle modifications in the prevention of preeclampsia

Deficient knowledge Assessment

1. Determine the patient’s knowledge level of preeclampsia.

Determine the patient’s knowledge level of preeclampsia.

Assessing the patient’s current knowledge and understanding of preeclampsia will help the nurse determine appropriate resources to guide learning.

2. Determine misconceptions about preeclampsia.

Preeclampsia can be misinterpreted by the patient due to past information or influences by family, friends, and cultures. Ask the patient directly about their understanding and clarify any questions as needed.

4. Assess readiness to learn.

Pregnancy can be an exciting and frightening journey, especially for first-time moms. Establish an uninterrupted time to provide information on preeclampsia that is not overwhelmed by other instructions.

Deficient knowledge Interventions

1. Instruct on symptoms to report.

Provide verbal and written instructions on symptoms to report to the healthcare provider such as blurred vision, headaches, epigastric pain, or difficulty breathing.

2. Involve the support system.

A mother requires support from her partner and family members. Information can be provided to support persons to monitor the patient and encourage healthy habits.

3. Encourage using positive reinforcement.

Positive reinforcement can be used to encourage behavior modification and teach new skills. It promotes motivation for further attempts at learning.

4. Instruct on appointments and tests.

Completing follow-up appointments, glucose monitoring, and blood pressure assessments will ensure a healthy pregnancy and delivery.

References and Sources

- Doenges, M. E., Moorhouse, M. F., & Murr, A. C. (2019). Nurse’s pocket guide: Diagnoses, interventions, and rationales (15th ed.). F A Davis Company.

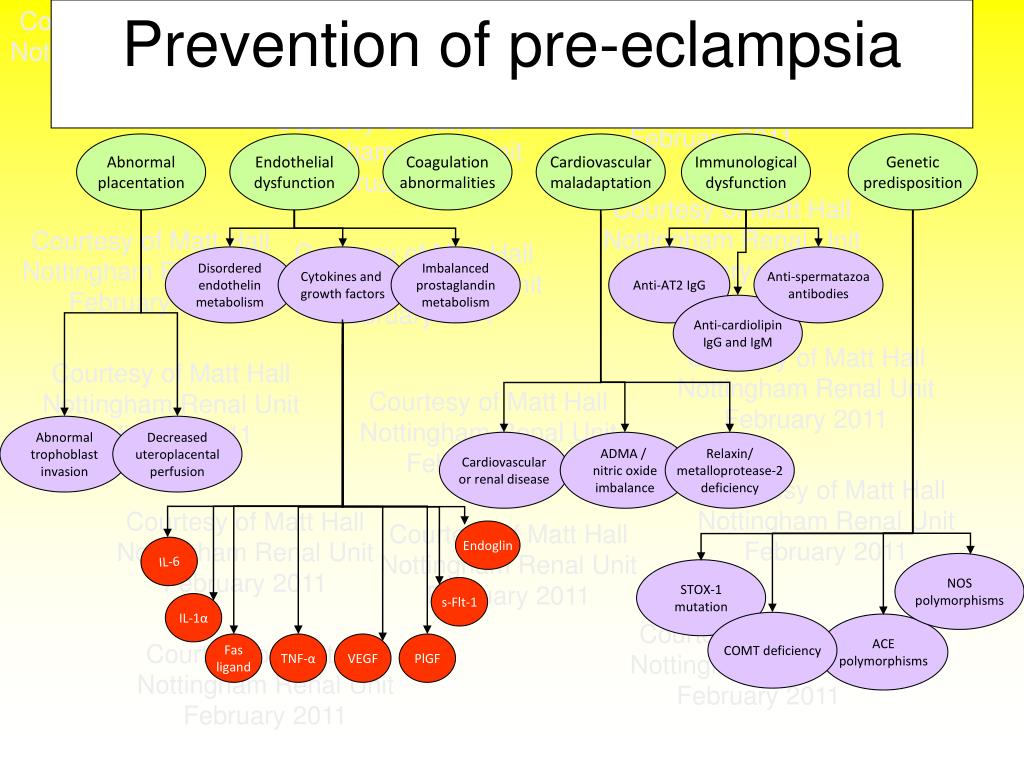

- Moura, S. B., Lopes, L. M., Murthi, P., & Costa, F. D. (2012, December 17). Prevention of Preeclampsia. PubMed Central (PMC).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3534321/

- Pillitteri, A., & Silbert-Flagg, J. (2015). Nursing Care of a Family Experiencing a Sudden Pregnancy Complication. In Maternal & child health nursing: Care of the childbearing & Childrearing family (8th ed., pp. 1210-1224). LWW.

- Silvestri, L. A., & CNE, A. E. (2019). Risk Conditions Related to Pregnancy. In Saunders comprehensive review for the NCLEX-RN examination (8th ed., pp. 687-688). Saunders.

Preeclampsia. Eclampsia. Anesthesia and intensive care in childbirth and the puerperium. Review

Preeclampsia. Eclampsia. Anesthesia and intensive care in childbirth and the puerperium. Review

- Register

- Login

Issue 1 (2020), ANESTHESIA AND INTENSIVE CARE IN OBSTETRICS

Issue 1 (2020)

ANESTHESIA AND INTENSIVE CARE IN OBSTETRICS

https://doi.org/10.21320/1818-474X-2020-1-41-52

Published 03/02/2020

- Natalia Yu.

Pylaeva + -

Pylaeva + - - E.M. Shifman + -

- A.V. Kulikov + -

- Natalya V. Artymuk + -

- T.E. Belokrinitskaya + −

- O.S. Phillipov + -

- T.Yu. Babich + -

Natalia Yu. Pylaeva

Medical Academy named after S.I. Georgievsky of Vernadsky CFU, Simferopol, Russia

E.M. Shifman

M.F.Vladimirsky Moscow Regional Research Clinical Institute, Moscow, Russia

A.V. Kulikov

Ural State Medical University, Yekaterinburg, Russia

Natalya V. Artymuk

Kemerovo State Medical Academy, Kemerovo, Russia

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7014-6492

T.E. Belokrinitskaya

Chita State Medical Academy, Chita, Russia

O.S. Phillipov

First Moscow State Medical University named after I. M. Sechenov, Moscow, Russia

M. Sechenov, Moscow, Russia

T.Yu. Babich

Medical Academy named after S.I. Georgievsky of Vernadsky CFU, Simferopol, Russia

keywords

gestational hypertensive disorders

preeclampsia

complications of preeclampsia

eclampsia

intensive care

How to Cite

1.

Pylaeva NY, Shifman EM, Kulikov AV, Artymuk NV, Belokrinitskaya TE, Phillipov OS, Babich TY. Preeclampsia. Eclampsia. Anesthesia and intensive care in childbirth and the puerperium. review. Annals of Critical Care . 2020;(1):41-52. doi:10.21320/1818-474X-2020-1-41-52

Language

Abstract

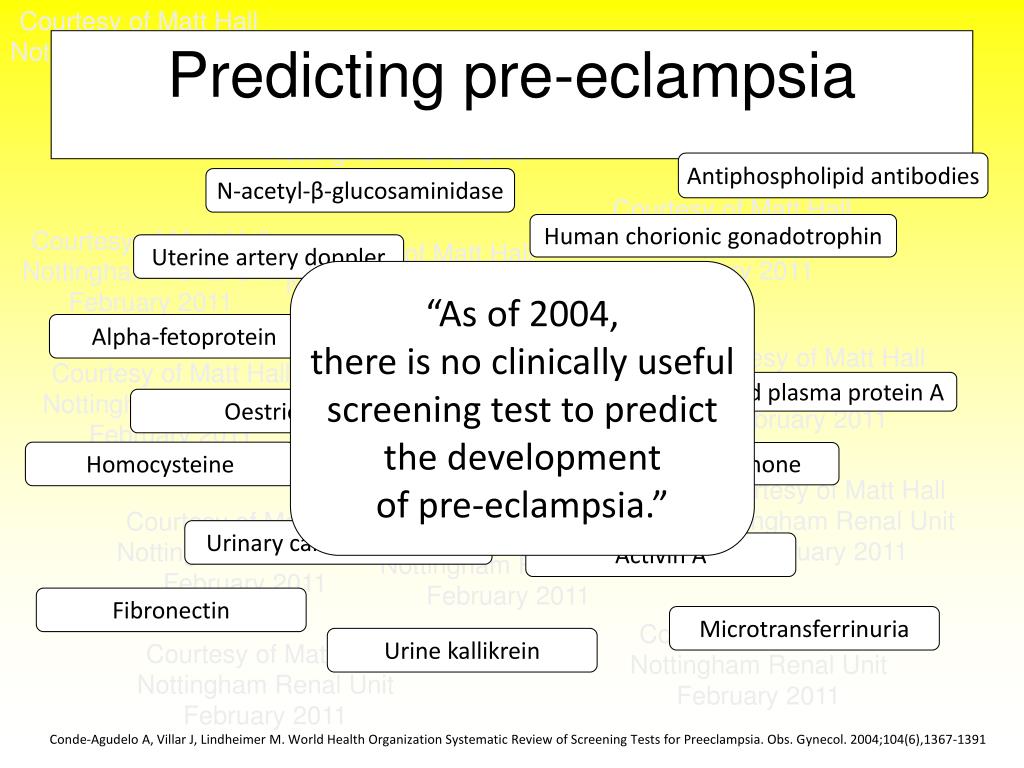

The review discusses the possibilities of predicting preeclampsia and its complications, modern criteria for the diagnosis of gestational hypertensive disorders and tactics of their intensive therapy. Particular attention was devoted to the anesthetic management for cesarean section in a woman with preeclampsia and its complications. The information proposed in the review makes it possible to define a unified terminology and form unified evidence-based interdisciplinary approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of preeclampsia, which will improve maternal and fetal outcome. nine0003

The information proposed in the review makes it possible to define a unified terminology and form unified evidence-based interdisciplinary approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of preeclampsia, which will improve maternal and fetal outcome. nine0003 https://doi.org/10.21320/1818-474X-2020-1-41-52

PDF_2020-01_41-52 (Russian)

HTML_2020-01_41-52 (Russian)

References

- Mol B.W.J., Roberts C.T., Thangaratinam S., et al. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016; 5(387): 999–1011. DOI: 10.1016/S0140–6736(15)00070–7

- Say L., Chou D., Gemmill A., et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2014; 2(6): 323–333. nine0006

- Maternal mortality in the Russian Federation in 2014 Methodological letter of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation dated 09.10.2015. [Maternal mortality in the Russian Federation in 2014. Methodical letter of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation of 09.10.

2015. (In Russ)]

2015. (In Russ)] - Bokslag A., van Weissenbruch M., Mol B.W., et al. preeclampsia; short and long-term consequences for mother and neonate. Early Hum Dev. 2016; 102:47–50. DOI: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.09.007

- Cífková R., Johnson M.R., Kahan T., et al. Peripartum management of hypertension. A position paper of the ESC Council on Hypertension and the European Society of Hypertension. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019; sixteen; pvz82. DOI: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvz082

- Brown M.A., Magee M.A., Kenny L.C., et al. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy ISSHP Classification, Diagnosis, and Management Recommendations for International Practice. hypertension. 2018; 72:24-43. DOI: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10803

- Tochio A., Obata S., Saigusa Y., et al. Does pre-eclampsia without proteinuria lead to different pregnancy outcomes than pre-eclampsia with proteinuria? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019; 45(8): 1576–1583. DOI: 10.1111/jog.14017

- Navolotskaya V.

K., Lyashko E.S., Shifman E.M. Uric acid is a “new” old marker of preeclampsia and its complications (literature review). reproduction problems. 2018; 24(4): 94–101. DOI: 10.17116/repro20182404194 [Navolotskaya V.K., Lyashko E.C., Shifman E.M., et al. Uric acid as an old “new” marker of preeclampsia and its commplications (a review). Problemi reproductions. 2018; 24(4): 94–101. (In Russ)]

K., Lyashko E.S., Shifman E.M. Uric acid is a “new” old marker of preeclampsia and its complications (literature review). reproduction problems. 2018; 24(4): 94–101. DOI: 10.17116/repro20182404194 [Navolotskaya V.K., Lyashko E.C., Shifman E.M., et al. Uric acid as an old “new” marker of preeclampsia and its commplications (a review). Problemi reproductions. 2018; 24(4): 94–101. (In Russ)] - Dong X., Gou W., Li C., et al. Proteinuria in preeclampsia: Not essential to diagnosis but related to disease severity and fetal outcomes. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017; 8:60–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.preghy

- Pylaeva N.Yu., Shifman E.M., Fedosov M.I., Pylaev I.A. The relationship of proteinuria recorded upon admission to the hospital, on the outcome of pregnancy and childbirth in patients with preeclampsia. Bulletin of Intensive Care. A.I. Saltanov. 2019; 4:98–105. [Pylaev N.Y., Shifman E.M., Fedosov M.I., Pylaev I.A. The relationship of proteinuria, recorded upon admission to the hospital, on the outcome of pregnancy and childbirth in patients with preeclampsia.

Vestnik intensivnoj terapii im. AI Saltanova. 2019; 4:98–105. (In Russ)]

Vestnik intensivnoj terapii im. AI Saltanova. 2019; 4:98–105. (In Russ)] - American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013; 122(5): 1122–1131. nine0006

- Magee L.A., Yong P.J., Espinosa V., et al. Expectant management of severe pre-eclampsia remote from term: a structured systematic review. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2009(3): 312–347.

- Witcher P.M. Preeclampsia: Acute Complications and Management Priorities. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2018; 29(3): 316–326. DOI: 10.4037/aacnacc2018710

- Sibai B.M. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 205(3): 191–198.

- Fong A., Chau C.T., Pan D., Ogunyemi D.A. Clinical morbidities, trends, and demographics of eclampsia: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 209(229): e221–e227.

- Hart L.A., Sibai B.M. Seizures in pregnancy: epilepsy, eclampsia, and stroke. Semin Perinatol. 2013; 37:207–224.

- Thornton C., Dahlen H., Korda A., Hennessy A. The incidence of preeclampsia and eclampsia and associated maternal mortality in Australia from population-linked datasets: 2000–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 208(476): e1–e5. nine0006

- Magee L.A., Pels A., Helewa M., et al. Canadian Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy Working Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: executive summary. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014; 36(5): 416–441.

- Bojja V., Keepanasseril A., Nair P.P., Sunitha V.C. Clinical and imaging profile of patients with new-onset seizures & a presumptive diagnosis of eclampsia — A prospective observational study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018; 12:35–39. DOI: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.02.008

- Sanghavi M., Rutherford J.D. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. circulation. 2014; 130:1003–1008.

- Kazma J.M., van den Anker J., Allegaert K., et al. Anatomical and physiological alterations of pregnancy. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2020; Feb 6. DOI: 10.1007/s10928-020-09677-1

- Liu S., Elkayam U., Naqvi T.Z. Echocardiography in pregnancy: Part 1. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016; 18:92.

- Melchiorre K., Sharma R., Thilaganathan B. Cardiovascular implications in pre-eclampsia: an overview. circulation. 2014; 130:703–714.

- Shahul S., Rhee J., Hacker M.R., et al. Subclinical left ventricular dysfunction in preeclamptic women with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a 2D speckle-tracking imaging study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012; 5:734–739.

- Shivananjiah C., Nayak A., Swarup A. Echo changes in hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2016; 26:94–96.

- Weiniger C.F., Sharoni L. The use of ultrasound in obstetric anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017; 30:306–312.

- Zieleskiewicz L., Contargyris C., Brun C.

, et al. Lung ultrasound predicts interstitial syndrome and hemodynamic profile in par- turients with severe pre-eclampsia. Anesthesiology. 2014; 120:906–914.

, et al. Lung ultrasound predicts interstitial syndrome and hemodynamic profile in par- turients with severe pre-eclampsia. Anesthesiology. 2014; 120:906–914. - Fang X., Wang H., Liu Z., et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in preeclampsia and eclampsia: The role of hypomagnesemia. Seizure. 2020; 76:12–16. DOI: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.01.003

- Chen Z., Zhang G., Lerner A., et al. Risk factors for poor outcome in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018; 8(4): 421–432. DOI: 10.21037/qims.2018.05.07

- Amirian I., Rørbye C., Due Buron B.M., et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome — an MRI diagnosis often missed in pregnancy. Ugeskr Laeger. 2018; 10: V01180049.

- Katsevman G.A., Turner R.C., Cheyuo C., et al. Post-partum posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome requiring decompressive craniectomy: case report and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien).

2019; 161(2): 217–224. DOI: 10.1007/s00701-019-03798-4

2019; 161(2): 217–224. DOI: 10.1007/s00701-019-03798-4 - GAIN. Management of Severe Pre-eclampsia and Eclampsia. Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network; 2012.

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Pre-Eclampsia and Eclampsia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Bezerra M.E., Moura H.S., Marques Lopes L., et al. Prevention of preeclampsia. J Pregnancy. 2012; 2012: 435090. DOI: 10.1155/2012/435090

- McLaughlin K., Scholten R.R., Parker J.D., et al. Low molecular weight heparin for the prevention of severe preeclampsia: where next? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018; 84(4): 673–678. DOI: 10.1111/bcp.13483

- Wang X., Gao H. Prevention of preeclampsia in high-risk patients with low-molecular-weight heparin: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018; Nov 20:1–7. DOI: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1543656 nine0005 Salles A.M., Galvao T.F., Silva M.T., et al. Antioxidants for preventing preeclampsia: a systematic review.

- Saccone G., Saccone I., Berghella V. Omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and fish oil supplementation during pregnancy: which evidence? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016; 29(15): 2389–2397. DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1086742

- Aalami-Harandi R., Karamali M., Asemi Z., et al. Neonatal Med. The favorable effects of garlic intake on metabolic profiles, hs-CRP, biomarkers of oxidative stress and pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women at risk for pre-eclampsia: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. 2015; 28(17): 2020–2027. DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2014.977248

- Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of the Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline. no. 307, May 2014 (Replaces No. 206, March 2008).

- Organization of medical evacuation of pregnant women, women in labor and childbirth in case of emergency. Clinical guidelines. Moscow, 2015 (approved by the Russian Ministry of Health on October 2, 2015 No.

15-4/10/2-5802). [Organization of medical evacuation of pregnant women, women in childbirth and puerperas in case of emergency. clinical recommendations. Moscow, 2015 (approved by the Russian Ministry of Health on October 2, 2015 No. 15-4/10/2-5802). (In Russ)]

15-4/10/2-5802). [Organization of medical evacuation of pregnant women, women in childbirth and puerperas in case of emergency. clinical recommendations. Moscow, 2015 (approved by the Russian Ministry of Health on October 2, 2015 No. 15-4/10/2-5802). (In Russ)] - Von Dadelszen P., Magee L. Pre-eclampsia: an update. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014; 16:1–14.

- Rucklidge M.W.M., Hughes R.D. Central venous pressure monitoring in severe preeclampsia: a survey of UK practice. IJOA. 2011; 20(3): 274.

- Moureau N., Lamperti M., Kelly L.J., et al. Evidence-based consensus on the insertion of central venous access devices: definition of minimal requirements for training. Br J Anaesth. 2013; 110(3): 347–356. nine0006

- Broadhurst D., Moureau N., Ullman A.J. Central venous access devices site care practices: an international survey of 34 countries. J Vasc Access. 2016; 17(1): 78–86. DOI: 10.5301/jva.500045

- Hunter L.A., Gibbins K.J. Magnesium sulfate: past, present, and future.

J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011; 56(6): 566–574.

J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011; 56(6): 566–574. - Graham N.M., Gimovsky A.C., Roman A., Berghella V. Blood loss at cesarean delivery in women on magnesium sulfate for preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015; 2:1–5. nine0006

- Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia and the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Anesthesiology. 2016; 124(2): 270–300.

- Mushambi M.C., Kinsella S.M., Popat M., et al. Obstetric Anaesthetistsʼ Association and Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 2015; 70(11): 1286–1306. DOI: 10.1111/anae.13260

- Kelly A., Tran Q. The Optimal Pain Management Approach for a Laboring Patient: A Review of Current Literature. Cureus. 2017; 9(5): e1240.

- Mhyre J.M., Healy D. The unanticipated difficult intubation in Obstetrics. Anesth Analg.

2011; 112:648–652.

2011; 112:648–652. - Mushambi M.C., Kinsella S.M., Popat M., et al. Obstetric Anaesthetistsʼ Association and Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics Anaesthesia. 2015; 70(11): 1286–1306. DOI: 10.1111/anae.13260

- Pascoal A.C.F., Katz L., Pinto M.H., et al. Serum magnesium levels during magnesium sulfate infusion at 1 gram/hour versus 2 grams/hour as a maintenance dose to prevent eclampsia in women with severe preeclampsia: A randomized clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98(32): e16779. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016779

- Poon L.C., Nicolaides K.H. Early prediction of preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2014; 297397: 11. DOI: /10.1155/2014/297397

- Lowe S.A., Bowyer L., Lust K., et al. SOMANZ guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol.

2015; 55(5): e1–e29.

2015; 55(5): e1–e29. - Makarov O.V., Tkacheva O.N., Volkova E.V. Preeclampsia and chronic arterial hypertension. Clinical aspects. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2010. [Makarov O.V., Tkacheva O.H., Volkova E.V. Preeclampsia and chronic arterial hypertension. clinical aspects. Moscow: GEOTAR-Media; 2010. (In Russ)]

- Patel K.P., Romagano M.P., Apuzzio J., et al. Maternal Morbidity in Patients With Preeclampsia With Severe Features at Less Than 34 Weeks Gestation [25N]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019; 133:157. DOI: 10.1097/01.aog.0000559331.11145.69

- Gordon R., Magee L.A., Payne B., et al. Magnesium sulphate for the management of preeclampsia and eclampsia in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of tested dosing regimens. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014; 36(2): 154–163. nine0006

- Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 623: Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 125(2): 521–525.

- Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 122:1112–1131.

- Anesthesia, intensive care and resuscitation in obstetrics and gynecology. Clinical guidelines. treatment protocols. 3rd ed., add. and reworked. Ed. A.V. Kulikova, E.M. Shifman. M.: Medicine; 2018. [Anesteziya, intensivnaya terapiya i reanimaciya v akusherstve i ginekologii. Klinicheskie rekomendacii. Protokoly treatment. Izdanie tretʼe, dopolnennee i pererabotannoe / Pod redakciej A.V. Kulikova, E.M. Shifmana. M.: Medicina, 2018. (In Russ)]

- McDonnell N.J., Muchatuta N.A., Paech M.J. Acute magnesium toxicity in an obstetric patient undergoing general anaesthesia for caesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010; 19:226–231.

- Dennis A.T., Chambers E., SerangK. Blood pressure assessment and first-line pharmacological agents in women with eclampsia. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia.

2015; 24:247–251.

2015; 24:247–251. - D’Angelo R., Smiley R.M., Riley E.T., Segal S. Serious complications related to obstetric anesthesia: the serious complication repository project of the society for obstetric anesthesia and perinatology. Anesthesiology. 2014; 120: 1505–1512. nine0006

- Duley L., Henderson-Smart D.J., Walker G.J., et al. Magnesium sulfate versus diazepam for eclampsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 12: CD000127. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000127.pub2

- Han C., Jiang X., Wu X., Ding Z. Application of dexmedetomidine combined with ropivacaine in the cesarean section under epidural anesthesia. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2014; 94(44): 3501–3505.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5): 1122–1131. nine0006

- Carles G., Helou J., Dallah F., et al.

Use of injectable urapidil in pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2012; 41(7): 645–649.

Use of injectable urapidil in pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2012; 41(7): 645–649. - Diemunsch P., Garcia V., Lyons G., et al. Urapidil versus nicardipine in preeclamptic toxaemia: A randomized feasibility study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015; 32(11): 822–823. DOI: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000303

- Yakoob M.Y., Bateman B.T., Ho E., et al. The risk of congenital malformations associated with exposure to b-blockers early in pregnancy: a meta-analysis. hypertension. 2013; 62:375–381. nine0006

- Koren G. Systematic review of the effects of maternal hypertension in pregnancy and antihypertensive therapies on child neurocognitive development. Reprod Toxicol. 2013; 39:1–5.

- Pretorius T., van Rensburg G., Dyer R.A., et al. The influence of fluid management on outcomes in preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2018; 34:85–95. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2017.12.004

- Claesson J., Freundlich M.

, Gunnarsson I., et al. Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Scandinavian clinical practice guideline on mechanical ventilation in adults with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015; 59(3): 286–297.

, Gunnarsson I., et al. Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Scandinavian clinical practice guideline on mechanical ventilation in adults with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015; 59(3): 286–297. - Villalain C., Herraiz I., Cantero B., et al. Angiogenesis biomarkers for the prediction of severe adverse outcomes in late-preterm preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2020; 19:74–80. DOI: 10.1016/j.preghy.2019.12.004

- Giorgi V.S., Witkin S.S., Bannwart-Castro C.F., et al. Elevated circulating adenosine deaminase activity in women with preeclampsia: association with pro-inflammatory cytokine production and uric acid levels. Pregnancy hypertension. 2016; 6(4): 400–405. DOI: 10.1016/j.preghy.2016.09.004

- Navolotskaya V.K., Lyashko E.S., Shifman E.M. Brain natriuretic peptide and its role in the prediction and early diagnosis of preeclampsia and its complications. Issues of gynecology, obstetrics and perinatology.

2018; 17(5): 63–72. DOI: 10.20953/1726-1678-2018-5-63-72. [Navolotskaya V.K., Lyashko E.S., Shifman E.M., et al. Brain natriuretic peptide and its role in predicting and early diagnosis of preeclampsia and its complications. Voprosy ginekologii, akusherstva i perinatologii. 2018; 17(5): 63–72. (In Russ)]

2018; 17(5): 63–72. DOI: 10.20953/1726-1678-2018-5-63-72. [Navolotskaya V.K., Lyashko E.S., Shifman E.M., et al. Brain natriuretic peptide and its role in predicting and early diagnosis of preeclampsia and its complications. Voprosy ginekologii, akusherstva i perinatologii. 2018; 17(5): 63–72. (In Russ)] - Borges V.T.M., Zanati S.G., Peraçoli M.T.S., et al. Maternal left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction and brain natriuretic peptideconcentration in early-and late-onset pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 51(4): 519–523.

- Pylaeva N.Yu., Shifman E.M., Pylaev A.V. and other Prediction of complications of preeclampsia. Tauride Medical and Biological Bulletin. 2019; 22(2): 108–117. [Pylaeva N.J., Shifman E.M., Pylaev A.V., et al. Prediction of complications of preeclampsia. Tavricheskij mediko-biologicheskij vestnik. 2019; 22(2): 108–117. (In Russ)]

- Ukah U.V., De Silva D.A., Payne B., et al. Prediction of adverse maternal outcomes from pre-eclampsia and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A systematic review.

Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018; 11:115–123. DOI: 10.1016/j.preghy.2017.11.006

Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018; 11:115–123. DOI: 10.1016/j.preghy.2017.11.006

Scientific World Journal. 2012; 2012: 243476. DOI: 10.1100/2012/243476

Scientific World Journal. 2012; 2012: 243476. DOI: 10.1100/2012/243476 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2020 ANNALS OF CRITICAL CARE

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Igor B. Zabolotskikh, M. Yu. Kirov, K.M. Lebedinsky, D.N. Protsenko, S.N. Avdeev, A.A. Andreenko, L.V. Arsentiev, V.S. Afonchikov, I.I. Afukov, A.A. Belkin E.A. Boeva, A. Yu. Bulanov, Ya.I. Vasiliev, A.V. Vlasenko, V.I. Gorbachev, E.V. Grigor'ev, S.V. Grigor'ev, A.I. Gritsan, A.A. Eremenko, E.N. Ershov, M.N. Zamyatin, A.N. Kuzovlev, A.V. Kulikov, R.E. Lakhin, I.N. Leiderman, A.I. Lenkin, V.A. mazurok, T.S. Musaeva, E.M. Nikolaenko, Yu.P. orlov, S.S. Petrikov, E.V. Roitman, A.M. Ronson, A.A. Smetkin, A.A. Sokolov, S.M. Stepanenko, V.V. subbotin, N.D. Ushakova, V.E. Khoronenko, S.V. Tsarenko, E.M. Shifman, D.L. Shukevich, A.V. Shchegolev, A.I. Yaroshetskiy, M.B. Yarustovsky, Anesthesia and intensive care for patients with COVID-19.

Russian Federation of anesthesiologists and reanimatologists guidelines , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 1 (2020) Supplement

Russian Federation of anesthesiologists and reanimatologists guidelines , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 1 (2020) Supplement - Igor B. Zabolotskikh, M. Yu. Kirov, K.M. Lebedinsky, D.N. Protsenko, S.N. Avdeev, A.A. Andreenko, L.V. Arsentiev, V.S. Afonchikov, I.I. Afukov, A.A. Belkin E.A. Boeva, A. Yu. Bulanov, Ya.I. Vasiliev, A.V. Vlasenko, V.I. Gorbachev, E.V. Grigor'ev, S.V. Grigor'ev, A.I. Gritsan, A.A. Eremenko, E.N. Ershov, M.N. Zamyatin, G.E. ivanova, A.N. Kuzovlev, A.V. Kulikov, R.E. Lakhin, I.N. Leiderman, A.I. Lenkin, V.A. mazurok, T.S. Musaeva, E.M. Nikolaenko, Yu.P. orlov, S.S. Petrikov, E.V. Roitman, A.M. Ronson, A.A. Smetkin, A.A. Sokolov, S.M. Stepanenko, V.V. subbotin, N.D. Ushakova, V.E. Khoronenko, S.V. Tsarenko, E.M. Shifman, D.L. Shukevich, A.V. Shchegolev, A.I. Yaroshetskiy, M.B. Yarustovsky, Anesthesia and intensive care for patients with COVID-19. Russian Federation of anesthesiologists and reanimatologists guidelines , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 1 (2021) Supplement

- L.

V. adamyan, N.V. artymuk, T.E. Belokrinickaya, A.V. Kulikov, Dmitry Marshalov, A.P. petrenko, I.A. salov, O.S. Filippov, E.M. Shifman, Intensive treatment of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Clinical guidelines (treatment protocol) , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 4 (2018) nine0006

V. adamyan, N.V. artymuk, T.E. Belokrinickaya, A.V. Kulikov, Dmitry Marshalov, A.P. petrenko, I.A. salov, O.S. Filippov, E.M. Shifman, Intensive treatment of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Clinical guidelines (treatment protocol) , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 4 (2018) nine0006 - Natalya V. Artymuk, T.E. Belokrinitskaya, O.S. Filippov, E.M. Shifman, COVID-19 in pregnant women of Siberia and the Far East. article , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 2 (2020)

- Igor B. Zabolotskikh, M.A. Anisimov, E.S. Gorobets, A.I. Gritsan, K.M. Lebedinsky, T.S. Musaeva, D.N. Protsenko, N.V. Trembach, R.V. Shadrin, E.M. Shifman, S.L. Epstein, Perioperative management of patients with concomitant morbid obesity. Guidelines of the All-Russian public organization “Federation of Anesthesiologists and Reanimatologists” , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 1 (2021) nine0006

- E.M. Shifman, A.V. Kulikov, Alexander M. Ronenson, I.S. Abazova, L.V. adamyan, M.D. andreeva, N.V. artymuk, O.R. Baev, S.

V. barinov, T.E. Belokrinitskaya, S.I. blauman, I.V. Bratishchev, A.A. bukhtin, V.Y. Vartanov, A.B. Volkov, V.S. Gorokhovskiy, N.V. Dolgushina, A.N. Drobinskaya, S.V. Kinzhalova, I.Z. Kitiashvili, I.Yu. kogan, A. Yu. Korolev, V.I. Krasnopolskii, I.I. Kukarskaya, M.A. Kurcer, D.V. marshalov, A.A. Matkovskiy, A.M. Ovezov, G.A. Penzhoyan, T.Yu. Pestrikova, V.A. petruhin, A.M. prihodko, N.V. Protopopova, D.N. Protsenko, A.V. Pyregov, Yu.S. Raspopin, O.V. Rogachevskiy, O.V. Ryazanova, G.M. Savelyeva, Yu.A. Semenov, S.I. Sitkin I.F. fatcullin, T.A. Fedorova, O.S. Filippov, M.V. shvechkova, R.G. Shmakov, A.V. Shchegolev, I.B. Zabolotskikh, Prevention, the algorithm of reference, anesthesia and intensive care for postpartum hemorrhage. Guidelines , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 3 (2019))

V. barinov, T.E. Belokrinitskaya, S.I. blauman, I.V. Bratishchev, A.A. bukhtin, V.Y. Vartanov, A.B. Volkov, V.S. Gorokhovskiy, N.V. Dolgushina, A.N. Drobinskaya, S.V. Kinzhalova, I.Z. Kitiashvili, I.Yu. kogan, A. Yu. Korolev, V.I. Krasnopolskii, I.I. Kukarskaya, M.A. Kurcer, D.V. marshalov, A.A. Matkovskiy, A.M. Ovezov, G.A. Penzhoyan, T.Yu. Pestrikova, V.A. petruhin, A.M. prihodko, N.V. Protopopova, D.N. Protsenko, A.V. Pyregov, Yu.S. Raspopin, O.V. Rogachevskiy, O.V. Ryazanova, G.M. Savelyeva, Yu.A. Semenov, S.I. Sitkin I.F. fatcullin, T.A. Fedorova, O.S. Filippov, M.V. shvechkova, R.G. Shmakov, A.V. Shchegolev, I.B. Zabolotskikh, Prevention, the algorithm of reference, anesthesia and intensive care for postpartum hemorrhage. Guidelines , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 3 (2019)) - Alexander M. Ronenson, E.M. Shifman, A.V. Kulikov, Assessment of volemic status in postpartum period: a pilot prospective cohort study , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 3 (2021)

- A.V.

Volkov, A.V. Ilyin, Konstantin M. Lebedinskii, I.B. Zabolotskikh, V.V. Lazarev, V.A. mazurok, A.M. Ovezov, E.M. Shifman, A.V. Shchegolev, G.N. Vasilyeva, Anesthesiologists-reanimatologists of Russia: a professional portrait of the community. A survey , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 4 (2021) nine0006

Volkov, A.V. Ilyin, Konstantin M. Lebedinskii, I.B. Zabolotskikh, V.V. Lazarev, V.A. mazurok, A.M. Ovezov, E.M. Shifman, A.V. Shchegolev, G.N. Vasilyeva, Anesthesiologists-reanimatologists of Russia: a professional portrait of the community. A survey , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 4 (2021) nine0006 - Yulya S. Mysovskaya, D.V. marshalov, E.M. Shifman, N.V. Shindyapina, A. Ioscovich, Differences in the views of obstetricians-gynecologists and intensivists based on the survey “Provision of medical care to patients with stillbirth”. original article , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 1 (2021)

- N.I. Ilyina, Igor B. Zabolotskikh, N.G. Astafieva, A. Zh. Bayalieva, A.V. Kulikov, T.V. Latysheva, K.M. Lebedinsky, T.S. Musaeva, T.N. Myasnikova, A.N. pampura, R.S. Fassakhov, L.G. Khludova, E.M. Shifman, Anaphylactic shock. Clinical guidelines of the Russian Association of Allergists and Clinical Immunologists and the All-Russian Public Organization “Federation of Anesthesiologists and Reanimatologists” , Annals of Critical Care: Issue 3 (2020) nine0006

1 2 > >>

Dr.