Most common week to give birth

How Many Weeks Early Can You Safely Give Birth?

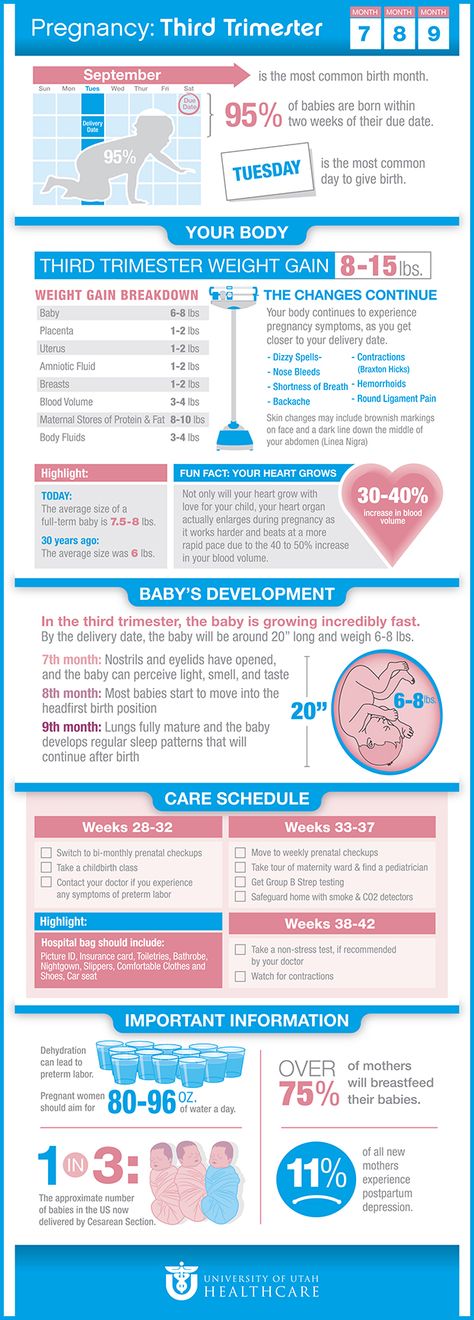

The end of the third trimester of pregnancy is typically full of both excitement and anxiety for baby’s arrival. It can also be physically uncomfortable and emotionally draining.

If you’re in this stage of pregnancy now, you might be experiencing swelling ankles, increased pressure in your lower abdomen and pelvis, and circling thoughts, such as, when will I go into labor?

By the time you reach 37 weeks, labor induction might seem like a beautiful gift from the universe, but researchers recommend waiting until your baby is full term, unless there are major health concerns for you or your baby.

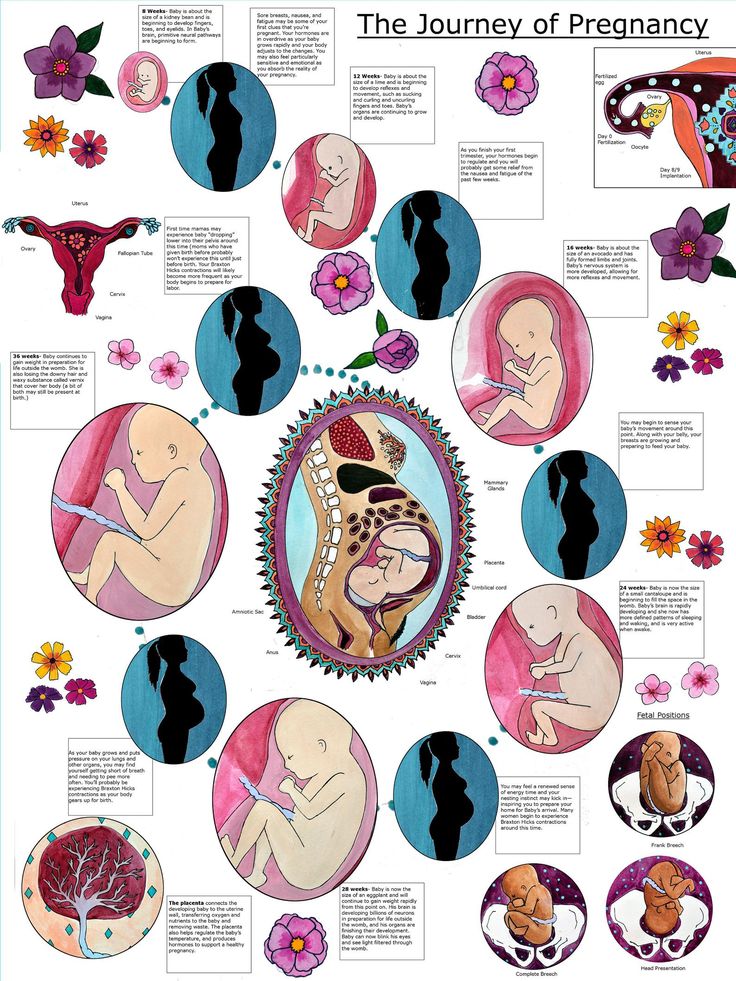

A full-term pregnancy is 40 weeks long. Although health practitioners once considered “term” to be from week 37 to week 42, those last few weeks are too vital to ignore.

It’s in this final crunch time that your body makes its final preparations for childbirth, while your baby completes the development of necessary organs (like the brain and lungs) and reaches a healthy birth weight.

The risk for neonatal complications is lowest in uncomplicated pregnancies delivered between 39 and 41 weeks.

To give your baby the healthiest start possible, it’s important to remain patient. Elected labor inductions before week 39 can pose short- and long-term health risks for the baby. Deliveries occurring at week 41 or later can have increased complications too.

No two women — no two pregnancies — are the same. Some babies will naturally arrive early, others late, without any major complications.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists categorize deliveries from week 37 to 42 as follows:

- Early term: 37 weeks through 38 weeks, 6 days

- Full term: 39 weeks through 40 weeks, 6 days

- Late term: 41 weeks through 41 weeks, 6 days

- Post-term: 42 weeks and beyond

The earlier your baby is born, the greater the risks to their health and survival.

If born before week 37, your baby is considered a “preterm” or “premature” baby. If born before week 28, your baby is considered “extremely premature.”

Babies born between weeks 20 to 25 have a very low chance of surviving without neurodevelopmental impairment. Babies delivered before week 23 have only a 5 to 6 percent chance of survival.

Nowadays, preterm and extremely preterm babies have the benefit of medical advances to help support the continued development of organs until their level of health is equivalent to that of a term baby.

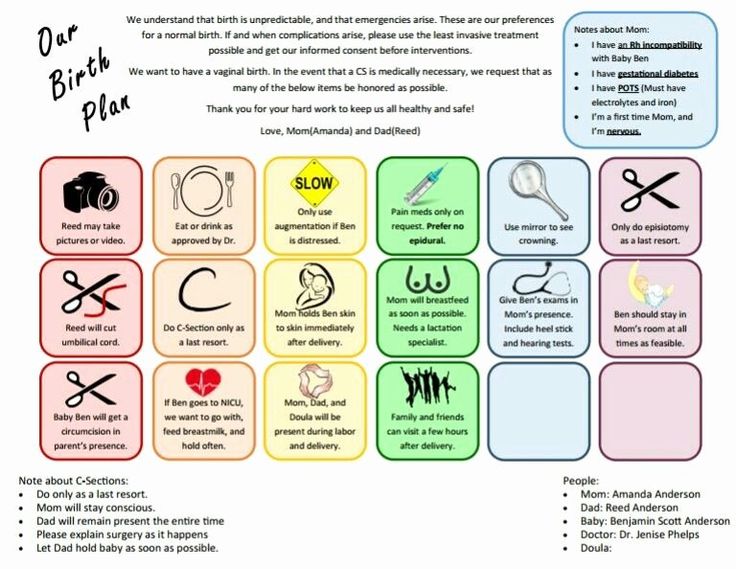

If you know you’ll have an extremely preterm delivery, you can work with your healthcare practitioner to create a plan for the care you and your baby will receive. It’s important to talk openly with your doctor or midwife to learn all of the risks and complications that may arise.

One of the most important reasons you want to reach full term in pregnancy is to ensure the complete development of the baby’s lungs.

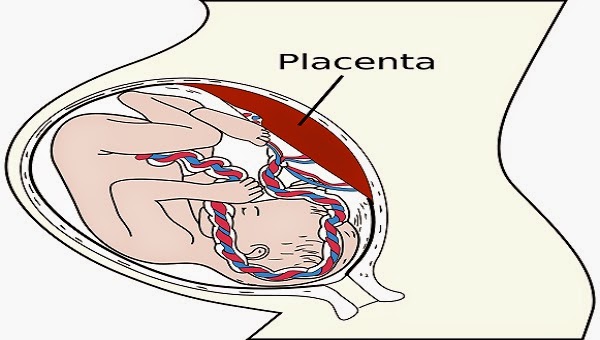

However, there are many factors related to the mom, baby, and placenta which will require the healthcare practitioner, doctor, or midwife to balance the risks associated with reaching full term against the benefit of full lung maturity.

Some of these factors include placenta previa, a prior cesarean or myomectomy, preeclampsia, twins or triplets, chronic hypertension, diabetes, and HIV.

In some cases, delivery earlier than 39 weeks is necessary. If you go into labor early or if your healthcare provider recommends labor induction, it’s still possible to have a positive, healthy experience.

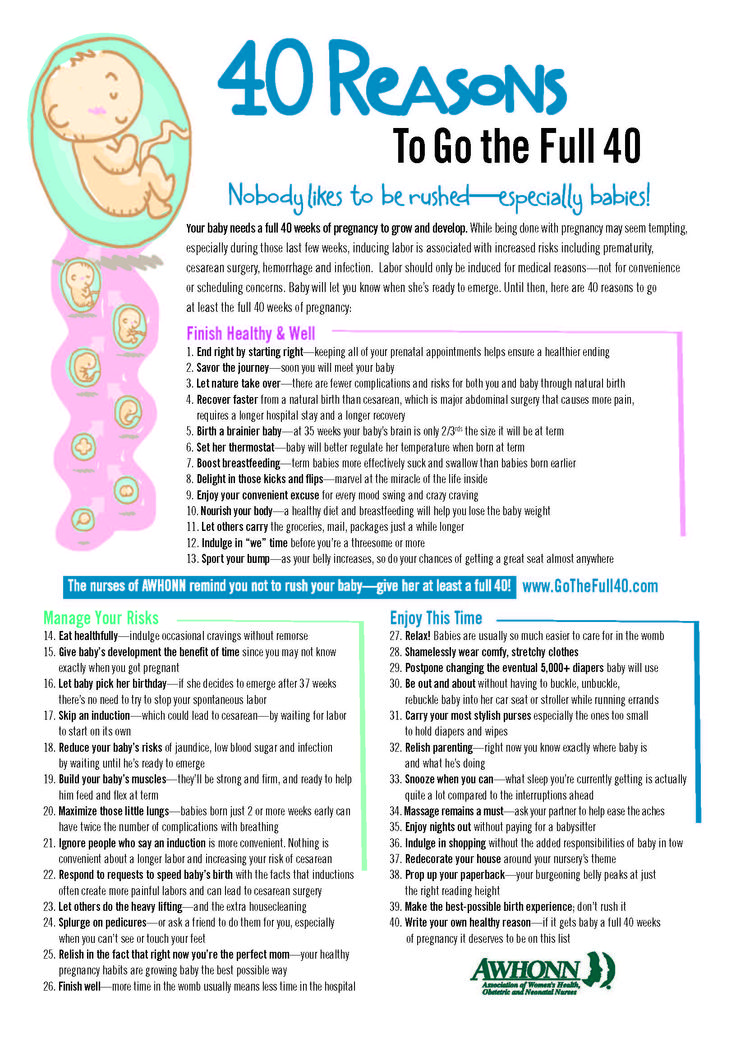

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, most babies are born full term. To be specific:

- 57.5 percent of all recorded births occur between 39 and 41 weeks.

- 26 percent of births occur at 37 to 38 weeks.

- About 7 percent of births occur at weeks 34 to 36

- About 6.5 percent of births occur at week 41 or later

- About 3 percent of births occur before 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Some women experience recurrent preterm deliveries (having two or more deliveries before 37 weeks).

Just like having a previous preterm baby is a risk factor for having another preterm baby, women with a prior post-term delivery are more likely to have another post-term delivery.

The odds of having a post-term birth increase if you are a first-time mother, having a baby boy, or obese (BMI greater than 30).

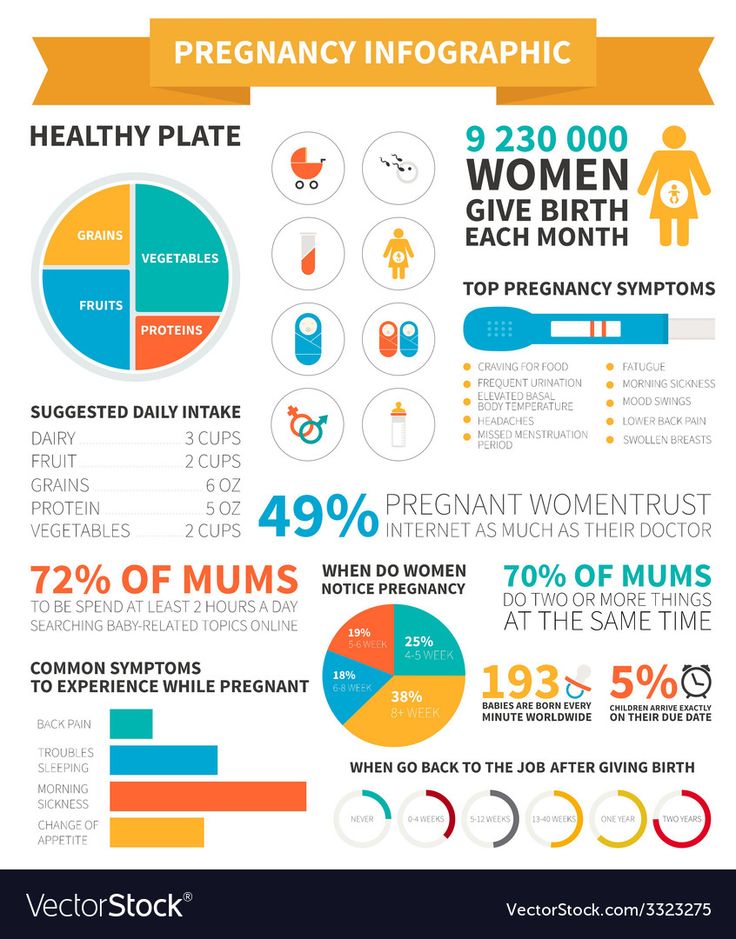

Most of the time, the cause of a premature birth remains unknown. However, women with a history of diabetes, heart disease, kidney disease, or high blood pressure are more likely to experience preterm deliveries. Other risk factors and causes include:

- pregnant with multiple babies

- bleeding during pregnancy

- misusing drugs

- getting a urinary tract infection

- smoking tobacco

- drinking alcohol during pregnancy

- premature birth in a previous pregnancy

- having an abnormal uterus

- developing an amniotic membrane infection

- not eating healthy before and during pregnancy

- a weak cervix

- a history of an eating disorder

- being overweight or underweight

- having too much stress

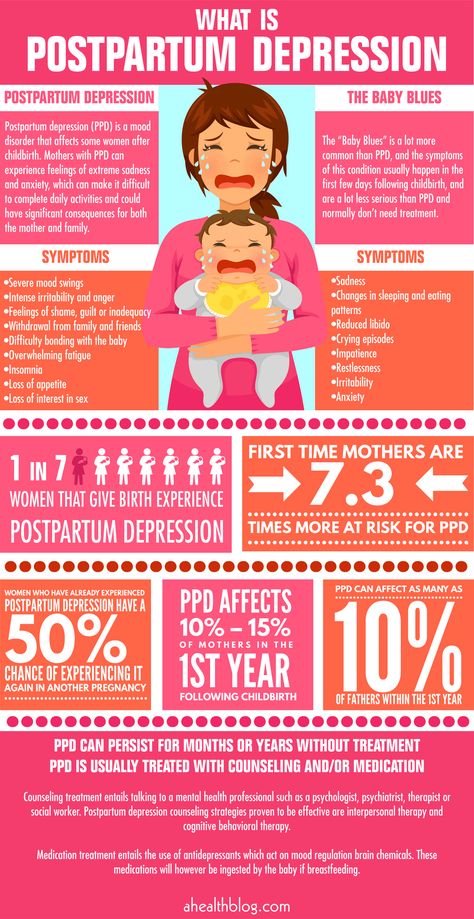

There are many health risks for preterm babies. Major life-threatening issues, like bleeding in the brain or lungs, patent ductus arteriosus, and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, can sometimes be successfully treated in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) but often require long-term treatment.

Other risks involved with preterm deliveries include:

- developmental delays

- trouble breathing

- vision and hearing problems

- low birth weight

- difficulties latching onto the breast and feeding

- jaundice

- difficulty regulating body temperature

Most of these conditions will require specialized care in a NICU. This is where the healthcare professionals will perform tests, provide treatments, assist breathing, and help feed premature infants. The care a newborn receives in the NICU will help ensure the best quality of life as possible for your baby.

Things to know about the NICU

For families who do end up with a baby in the NICU, there are a few simple things that can make a huge difference for baby’s overall health and recovery.

First, practicing kangaroo care, or holding baby directly skin to skin has been shown to reduce rates of mortality, infection, illness, and the length of hospital stay. It can also help parents and babies bond.

Second, receiving human breast milk in the NICU has been found to improve survival rates and dramatically reduce rates of a severe gastrointestinal infection called necrotizing entercolitis compared to babies who receive formula.

Moms who give birth to a preterm baby should start pumping breast milk as soon as possible after birth, and pump 8 to 12 times per day. Donor milk from a milk bank is also an option.

Doctors and nurses will watch your baby as they grow to ensure proper care and treatment, if it’s necessary. It’s important to stay informed, find the appropriate specialized care, and remain consistent with any future treatments and appointments.

Though there are no magical spells to ensure full-term pregnancies, there are a few things you can do on your own to lower your risk of early labor and birth.

Before getting pregnant

Get healthy! Are you at a healthy weight? Are you taking prenatal vitamins? You’ll also want to cut back on alcohol, try to stop smoking, and not misuse any drugs.

Exercise regularly and try to eliminate any unnecessary sources of stress from your life. If you have any chronic health conditions, get treated and remain consistent with treatments.

During pregnancy

Follow the rules. Eat healthy and get the proper amount of sleep. Exercise regularly (be sure to check with your healthcare provider before beginning any new exercise routine during pregnancy).

Go to every scheduled prenatal appointment, give an honest and thorough health history to your healthcare provider, and follow their advice. Protect yourself from potential infections and sickness. Make an effort to gain the appropriate amount of weight (again, talk to your OB about what’s ideal for you).

Seek medical attention for any warning signs of preterm labor, such as contractions, constant low back pain, water breaking, abdominal cramps, and any changes in vaginal discharge.

After delivery

Wait at least 18 months before trying to conceive again. The shorter the time is between pregnancies, the greater the risk for a preterm delivery, according to the March of Dimes.

The shorter the time is between pregnancies, the greater the risk for a preterm delivery, according to the March of Dimes.

If you’re older than 35, talk to your healthcare provider about the appropriate amount of time to wait before trying again.

Giving birth unexpectedly to a premature or post-term baby can be stressful and complicated, especially when it can’t be prevented. Talk with your doctor or midwife and stay informed.

Learning as much as you can about the procedures and treatments available to you and your baby will help lower anxieties and give you a sense of control.

Keep in mind that the options and support for premature babies have improved over the years, and the odds of leaving the hospital with a healthy baby are higher than ever before. The more you know, the better prepared you’ll be to provide your little one with all of the love and care they deserve.

Evidence on: Due Dates - Evidence Based Birth®

How do you figure out your estimated due date?Almost everyone—including doctors, midwives, and online due date calculators—uses Naegele’s rule (listen to the pronunciation here to figure out an estimated due date (EDD).

Naegele’s rule assumes that you had a 28-day menstrual cycle, and that you ovulated exactly on the 14th day of your cycle (Note: some health care providers will adjust your due date for longer or shorter menstrual cycles).

To calculate your EDD according to Naegele’s rule, you add 7 days to the first day of your last period, and then count forward 9 months (or count backwards 3 months). This is equal to counting forward 280 days from the date of your last period.

For example, if your last menstrual period was on April 4 you would add seven days (April 11) and subtract 3 months = an estimated due date of January 11.

Another way to look at it is to say that your EDD is 40 weeks after the first day of your last period.

In cases where the date of conception is known precisely, such as with in vitro fertilization or fertility tracking where people know their ovulation day, the EDD is calculated by adding 266 days to the date of conception (or subtracting 7 days and adding 9 months). This increases the accuracy of the EDD because it no longer assumes a Day 14 ovulation based on the first day of the last menstrual period.

This increases the accuracy of the EDD because it no longer assumes a Day 14 ovulation based on the first day of the last menstrual period.

In 1744, a professor from the Netherlands named Hermann Boerhaave explained how to calculate an estimated due date. Based on the records of 100 pregnant women, Boerhaave figured out the estimated due date by adding 7 days to the last period, and then adding nine months (Baskett & Nagele, 2000).

However, Boerhaave never explained whether you should add 7 days to the first day of the last period, or to the last day of the last period.

In 1812, a professor from Germany named Carl Naegele quoted Professor Boerhaave, and added some of his own thoughts. (This is how Naegele’s rule got its name!) However, Naegele, like Boerhaave, did not say when you should start counting—from the beginning of the last period, or the last day of the last period.

His text can be interpreted one of two ways: either you add 7 days to the first day of the last period, or you add 7 days to the last day of the last period.

As the 1800s went on, different doctors interpreted Naegele’s rule in different ways. Most added 7 days to the last day of the last period.

However, by the 1900s, for some unknown reason, American textbooks adopted a form of Naegele’s rule that added 7 days to the first day of the last period (Baskett & Nagele, 2000).

And so this brings us to today, where almost all doctors use a form of Naegele’s rule that adds 7 days to the first day of your last period, and then counts forward 9 months—a rule that is not based on any current evidence, and may not have even been intended by Naegele.

What is the most accurate way to tell how far along you are?Doctors started using ultrasound in the 1970s. Soon after, ultrasound measurement replaced last menstrual period (LMP) as the most reliable way to define gestational age (Morken et al., 2014).

A large body of evidence shows that ultrasounds done in early pregnancy are more accurate than using LMP to date a pregnancy. In a 2015 Cochrane review, researchers combined the results from 11 randomized clinical trials that compared routine early ultrasound to a policy of not routinely offering ultrasound (Whitworth et al. 2015).

In a 2015 Cochrane review, researchers combined the results from 11 randomized clinical trials that compared routine early ultrasound to a policy of not routinely offering ultrasound (Whitworth et al. 2015).

The researchers found that people who had an early ultrasound to date the pregnancy were less likely to be induced for a post-term pregnancy.

In other words, using the LMP to estimate your due date makes it more likely that you will be mislabeled as “post-term” and experience an unnecessary induction.

In a large observational study that enrolled more than 17,000 pregnant people in Finland, researchers found that ultrasound at any time point between 8 and 16 weeks was more accurate than the LMP. When ultrasound was used instead of a “certain” LMP (in other words, the mother is “certain” about the date she had her last period), the number of “post-term” pregnancies decreased from 10.3% to 2.7% (Taipale & Hiilesmaa, 2001).

Why is LMP less accurate than using ultrasound?There are several reasons why the LMP is usually less accurate than an ultrasound (Savitz et al. , 2002; Jukic et al., 2013; ACOG, 2017). LMP is less accurate because it can have these problems:

, 2002; Jukic et al., 2013; ACOG, 2017). LMP is less accurate because it can have these problems:

- People can have irregular menstrual cycles, or cycles that are not 28 days

- People may be uncertain about the date of their LMP

- Many people do not ovulate on the 14th day of their cycle

- The embryo may take longer to implant in the uterus for some people

- Research indicates that some people are more likely to recall a date that includes the number 5, or even numbers, so they may inaccurately recall that the first day of their LMP has one of these numbers in it.

In a 2013 study, researchers grouped ultrasound scans by <7 weeks, 7-10 weeks, 11-14 weeks, 14-19 weeks, and 20-27 weeks (Khambalia et al., 2013).

The authors found that the most accurate time to perform an ultrasound to determine the gestational age was 11-14 weeks. About 68% of people gave birth ±11 days of their estimated due date as calculated by ultrasound at 11-14 weeks. This was a more accurate result than any of the other ultrasound scans, and more accurate than the LMP.

About 68% of people gave birth ±11 days of their estimated due date as calculated by ultrasound at 11-14 weeks. This was a more accurate result than any of the other ultrasound scans, and more accurate than the LMP.

The accuracy of the ultrasound saw a significant decline starting at about 20 weeks. Using an estimated due date from either the LMP or an ultrasound at 20-27 weeks led to a higher rate of pre- and post-term births.

Should a due date be changed based on a third trimester ultrasound?In the Listening to Mothers III study, one in four mothers (26%) reported that their care provider changed their estimated due date based on a late pregnancy ultrasound. For 66% of the mothers, the estimated due date was moved up to an earlier date, while for 34% of the mothers, the date was moved back to a later date (Declercq et al., 2013).

Ultrasounds in the third trimester are less accurate than earlier ultrasounds or the LMP at predicting gestational age. Ultrasounds in the third trimester are not as accurate because they are measuring the size of the baby and comparing him or her to a “standard” sized baby. All babies are about the same size early in pregnancy. But if your baby will be larger than average, it will be perceived as “closer to done” when the ultrasound is done, and your due date will be moved up (incorrectly).

Ultrasounds in the third trimester are not as accurate because they are measuring the size of the baby and comparing him or her to a “standard” sized baby. All babies are about the same size early in pregnancy. But if your baby will be larger than average, it will be perceived as “closer to done” when the ultrasound is done, and your due date will be moved up (incorrectly).

The reverse is also true for babies that will be smaller than average at term—their due date might be moved to a later date. This could be risky if the baby is experiencing growth restriction, as growth-restricted babies have a higher risk of stillbirth towards the end of pregnancy. Because of these problems with third trimester ultrasounds, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that due dates should only be changed in the third trimester in very rare circumstances (2017).

They suggest that the due date should only be changed after a third trimester pregnancy ultrasound if 1) it is the pregnant person’s first ultrasound, and 2) it is more than 21 days different than the due date suggested by the LMP (ACOG, 2017).

In the U.S. and other Western countries, induction is common at or even before 40 weeks, so it is impossible to know exactly what percentage of people today would naturally go into labor and give birth before, on, or after their estimated due date.

In the past, researchers figured out the average length of a normal pregnancy by looking at a large group of pregnant people, and measuring the time from ovulation (or the last menstrual period, or an ultrasound) until the date the person gave birth—and calculating the average. However, this method is wrong and does not give us accurate results.

Why is this method wrong?This method does not work because many people are induced when they reach 39, 40, 41, or 42 weeks.

If you do include these induced people in your average, then you are including people who gave birth earlier than they would have otherwise, because they were not given time to go into labor on their own.

But this puts researchers in a bind, because if you exclude a person who was induced at 42 weeks from your study, then you are ignoring a pregnancy that was induced because it went longer—and by excluding that case, you artificially make the average length of pregnancy too short.

So how can we deal with this problem?Researchers today use a method called “survival analysis” or “time to event analysis.” This is a special method that allows you to include all of these people in your study, and still get an accurate picture of how long it takes the average person to go into spontaneous labor. There have been two studies that measured the average length of pregnancy using survival analysis:

Study finds that estimated due date is 3 to 5 days AFTER 40 weeksIn a very important study published in 2001, Smith looked at the length of pregnancy in 1,514 healthy women whose estimated due dates, as calculated by the first day of the last menstrual period, were perfect matches with estimated due dates from their first trimester ultrasound (Smith, 2001a).

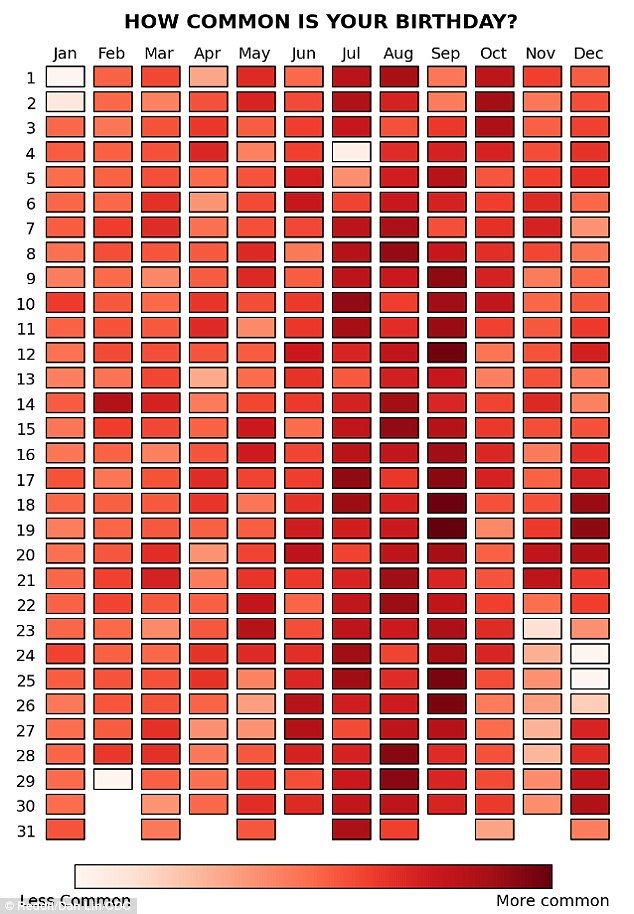

The researchers found that 50% of all women giving birth for the first time gave birth by 40 weeks and 5 days, while 75% gave birth by 41 weeks and 2 days.

Meanwhile, 50% of all women who had given birth at least once before gave birth by 40 weeks and 3 days, while 75% gave birth by 41 weeks.

This means that for both first-time and experienced mothers in Smith’s study, the traditional “estimated due date” of 40 weeks was wrong!

The actual pregnancy was about 5 days longer than the traditional due date (using Naegele’s rule) in a first-time mother, and 3 days longer than the traditional due date in a mother who has given birth before.

Study finds that estimated due date should be closer to 40 weeks and 5 daysIn 2013, Jukic et al. used survival analysis to look at the normal length of a pregnancy. This was a smaller study—there were only 125 healthy women, and they all gave birth between the years 1982 and 1985. However, this was also an important study, because researchers followed the participants even before conception and measured their hormones daily for six months (Jukic et al. , 2013).

, 2013).

This means that the researchers knew the exact days that the participants ovulated, conceived, and even when their pregnancies implanted!

So what was the average length of a pregnancy in this study?

After excluding women who had preterm births or pregnancy-related medical conditions, the final sample of 113 women had a median time from ovulation to birth of 268 days (38 weeks, 2 days after ovulation).

The median time from the first day of the last menstrual period to birth was 285 days (or 40 weeks, 5 days after the last menstrual period).

The length of pregnancy ranged from 36 weeks and 6 days to one person who gave birth 45 weeks and 6 days after the last menstrual period. The 45 weeks and 6 days sounds really long… but this particular person actually gave birth 40 weeks and 4 days after ovulation. Her ovulation did not fit the normal pattern, so we know her LMP due date was not accurate.

The researchers also found that:

- 10% gave birth by 38 weeks and 5 days after the LMP

- 25% gave birth by 39 weeks and 5 days after the LMP

- 50% gave birth by 40 weeks and 5 days after the LMP

- 75% gave birth by 41 weeks and 2 days after the LMP

- 90% gave birth by 44 weeks and zero days after the LMP

Remember though, some of the participants did not ovulate on the 14th day of their period (that’s why you saw the statistic that 10% still haven’t given birth by 44 weeks after the LMP!) So if we look at when people give birth after ovulation, you’ll see this pattern:

- 10% gave birth by 36 weeks and 4 days after ovulation

- 25% gave birth by 37 weeks and 3 days after ovulation

- 50% gave birth by 38 weeks and 2 days after ovulation

- 75% gave birth by 39 weeks and 2 days after ovulation

- 90% gave birth by 40 weeks and zero days after ovulation

Women who had embryos that took longer to implant were more likely to have longer pregnancies. Also, women who had a specific sort of hormonal reaction right after getting pregnant (a late rise in progesterone) had a pregnancy that was 12 days shorter, on average.

Also, women who had a specific sort of hormonal reaction right after getting pregnant (a late rise in progesterone) had a pregnancy that was 12 days shorter, on average.

Based on the best evidence, there is no such thing as an exact “due date,” and the estimated due date of 40 weeks is not accurate. Instead, it would be more appropriate to say that there is a normal range of time in which most people give birth. About half of all pregnant people will go into labor on their own by 40 weeks and 5 days (for first-time mothers) or 40 weeks and 3 days (for mothers who have given birth before). The other half will not.

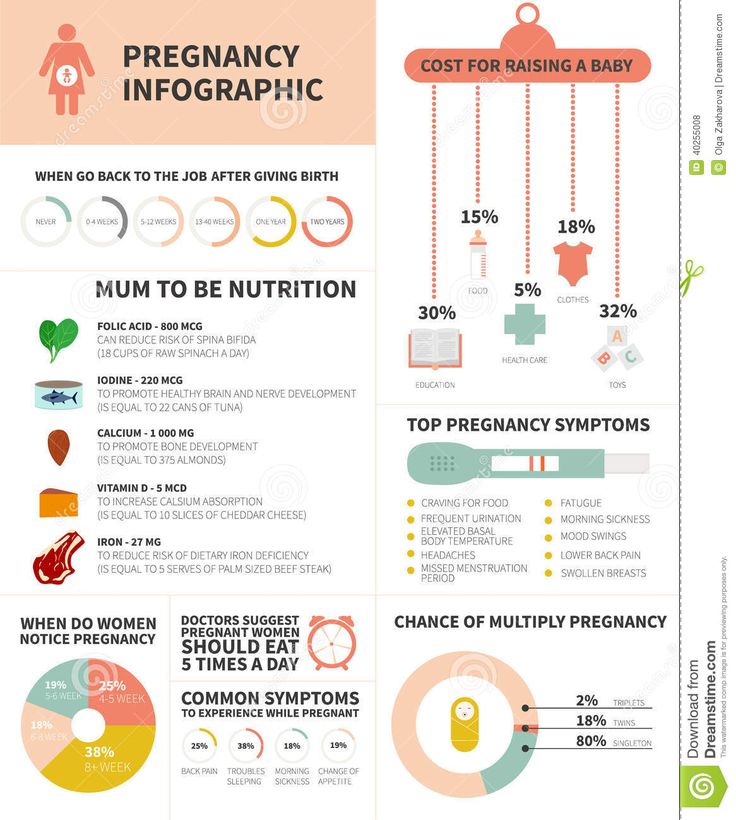

Are there some things that can make your pregnancy longer?By far, the most important predictor of a longer pregnancy is a family history of long pregnancies— including your own personal history, your mother and sisters’ history, and your baby’s biological father’s family history (Jukic et al. , 2013; Oberg et al., 2013; Mogren et al., 1999; Olesen, et al., 1999; Olesen et al., 2003).

, 2013; Oberg et al., 2013; Mogren et al., 1999; Olesen, et al., 1999; Olesen et al., 2003).

In 2013, Oberg et al. published a large study that looked at more than 475,000 Swedish births, most of which were dated with an ultrasound before 20 weeks. They found that genetics has an incredibly strong influence on your chance of having a birth after 42 weeks:

- If you’ve had a post-term birth before, you have 4.4 times the chance of having another post-term birth with the same partner

- If you’ve had a post-term birth before, and then you switch partners, you have 3.4 times the chance of having another post-term birth with your new partner

- If your sister had a post-term birth, you have 1.8 times the chance of having a post-term birth

Overall, researchers found that half of your chance for having a post-term birth comes from genetics. This includes the baby’s genetic tendency to gestate longer (due to genes the baby inherited from the mother and the father), and the mother’s genetic tendency to carry a pregnancy longer. The Swedish researchers even proposed that you could call some pregnancies “resistant,” because these mothers and/or fetuses have a genetically decreased tendency to start labor.

The Swedish researchers even proposed that you could call some pregnancies “resistant,” because these mothers and/or fetuses have a genetically decreased tendency to start labor.

Other factors that may make your pregnancy more likely to go longer include:

- Higher body mass index before you get pregnant (Halloran et al., 2012; Jukic et al., 2013; Oberg et al., 2013)

- Higher weight gain during pregnancy (Halloran et al., 2012)

- Longer time between when you ovulated and when your pregnancy implanted (Jukic et al., 2013)

- Older maternal age (Oberg et al., 2013; Jukic et al., 2013)

- Heavier birth weight of the mother (Jukic et al., 2013)

- Higher education level of the mother (Oberg et al., 2013)

- Being pregnant for the first time (Oberg et al., 2013)

- Being pregnant with a male baby (Divon et al., 2002; Oberg et al., 2013)

- Your mother had a post-term birth (Mogren et al., 1999; Olesen et al., 1999; Olesen et al.

, 2003)

, 2003) - The baby is measuring small by ultrasound at 10–24 weeks (Johnsen et al., 2008)

- Experiencing environmental stress towards the end of pregnancy (at 33-36 weeks) (Margerison-Zilko et al., 2015)

The risks of some complications go up as you go past your due date, and there are at least three important studies that have shown us what the risks are.

- In 2003, Caughey et al. looked at 135,560 people who gave birth at term in California between the years 1995 and 1999 (Caughey et al., 2003). The participants in this sample all gave birth at Kaiser Permanente hospitals in northern California. The overall use of interventions (Cesareans and inductions) in this sample was not listed.

- In 2004, Caughey et al. looked at the records of 45,673 people who gave birth in a single hospital in California from 1992 to 2002 (Caughey & Musci, 2004). The participants in this study were mostly well-educated.

As far as intervention rates go, 18% gave birth by Cesarean and 16% with the help of vacuum or forceps. The rate of inductions was not listed.

As far as intervention rates go, 18% gave birth by Cesarean and 16% with the help of vacuum or forceps. The rate of inductions was not listed. - In 2007, Caughey et al. studied the medical records of 119,254 people who gave birth after 37 weeks at Kaiser Permanente between the years of 1995 and 1999. This was the same time period and same hospital as his 2003 study, but this time the researchers only looked at low-risk people who had health insurance. The overall Cesarean rate was 13.8%, and 9.3% gave birth with the help of vacuum or forceps. The authors also took whether or not people had inductions into account when they calculated the risks of going past your due date (Caughey et al., 2007).

- The risk of chorioamnionitis (infection of the membranes) was lowest at 37 weeks (0.16%) and increased every week after that to a high of 6.15% at ≥ 42 weeks (Caughey et al., 2003)

- The risk of endomyometritis (infection of the uterus) was lowest at 38 weeks (0.

64%) and increased every week after that to a high of 2.2% at ≥ 42 weeks (Caughey & Musci, 2004)

64%) and increased every week after that to a high of 2.2% at ≥ 42 weeks (Caughey & Musci, 2004) - The risk of having a placenta abruption (placenta separates prematurely from the uterus) was lowest at 37 weeks (0.09%), and increased every week to a high of 0.44% at ≥ 42 weeks (Caughey et al., 2003)

- The risk of preeclampsia was lowest at 37 weeks (0.4%) and highest at 40 weeks (1.5%), after which the risk did not change (Caughey et al., 2003)

- The risk of postpartum hemorrhage was lowest at 37 weeks (1.1%) and increased almost every week to a high of 5% at 42 weeks (Caughey et al., 2007)

- The risk of a primary Cesarean (in people who have never had a Cesarean before) increased from 14.2% at 39 weeks to a high of 25% at ≥42 weeks (Caughey & Musci, 2004)

- The risk of having a primary Cesarean for a non-reassuring fetal heart rate was lowest at 37-39 weeks (13.3-14.5%) and reached a high of 27.5% at 42 weeks (Caughey et al., 2007)

- The risk of receiving forceps or vacuum assistance increased from 14.

1% at 38 weeks to a high of 18.5% at 41 weeks (Caughey & Musci, 2004)

1% at 38 weeks to a high of 18.5% at 41 weeks (Caughey & Musci, 2004) - The risk of having a 3rd or 4th degree tear was lowest at 37 weeks (3.4%) and increased every week to a high of 9.1% at 42 weeks. However, these numbers are much higher than are typically seen, and are partially related to the high use of vacuum and forceps in this study.

In their 2007 study, Caughey et al. reported that high use of induction, Cesareans, and vacuum/forceps for people with increasing gestational age may contribute to an increase in maternal risks. However, when the researchers used a statistical method to control for the use of interventions, the risks still increased with gestational age.

Risks for infants:- The risk of moderate or thick meconium increased every week starting at 38 weeks, and peaked at ≥42 weeks (3% at 37 weeks, 5% at 38 weeks, 8% at 39 weeks, 13% at 40 weeks, 17% at 41 weeks, and 18% at >42 weeks) (Caughey & Musci, 2004)

- Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission rates were lowest at 39 weeks (3.

9%) and rose to 5% at 40 weeks and 7.2% at ≥42 weeks (Caughey & Musci, 2004)

9%) and rose to 5% at 40 weeks and 7.2% at ≥42 weeks (Caughey & Musci, 2004) - The risk of the baby being large at birth (>9 lbs 15 oz or >4500 grams) rose starting at 38 weeks (0.5%), and doubled every week after that up until 42 weeks (6%) (Caughey & Musci, 2004)

- The odds of having a low 5-minute Apgar score went up starting at 40 weeks and increased each week until ≥42 weeks (exact numbers not reported; Caughey & Musci, 2004)

Other risks for post-term pregnancy include having low fluid, and something called dysmaturity syndrome (growth restriction plus muscle wasting), which happens in about 10% of babies who go past 42 weeks. For more information about meconium, see this article by Midwife Thinking about meconium stained waters.

What about the risk of stillbirth?In this section, we will talk about how the risk of stillbirth increases towards the end of pregnancy.

There are two very important things for you to understand when learning about stillbirth rates.

First, there is a difference between absolute risk and relative risk.

Absolute risk is the actual risk of something happening to you.For example, if the absolute risk of having a stillbirth at 41 weeks was 1.7 out of 1,000, then that means that 1.7 mothers out of 1,000 (or 17 out of 10,000) will experience a stillbirth.

Relative risk is the risk of something happening to you in comparison to somebody else.If someone said that the risk of having a stillbirth at 42 weeks compared to 41 weeks is 94% higher, then that sounds like a lot. But some people may consider the actual (or absolute) risk to still be low—1.7 per 1,000 versus 3.2 per 1,000.

Yes—3.2 is about 94% higher than 1.7, if you do the math! So, while it is a true statement to say “the risk of stillbirth increases by 94%,” it can be a little misleading if you are not looking at the actual numbers behind it.

Please see our handout on Talking about Due Dates for Providers for tips on how providers can discuss the risk of stillbirth.

The second important thing that you need to understand is that there are different ways of measuring stillbirth rates. Depending on how the rate is calculated, you can end up with different rates.

How do you measure stillbirth rates?Up until the 1980s, some researchers thought that the risk of stillbirth past 41-42 weeks was similar to the risk of stillbirth earlier in pregnancy. So, they did not think there was any increase in risk with going past your due date.

However, in 1987, a researcher named Dr. Yudkin published a paper introducing a new way to measure stillbirth rates. Dr. Yudkin said that earlier researchers used the wrong math when they calculated stillbirth rates—they used the wrong denominator! (Yudkin, Wood et al., 1987).

Here’s why this formula is wrong: We don’t need to know how many stillbirths happen out of every 1,000 births at 41 weeks. Instead, we need to know how many stillbirths happen at 41 weeks compared to all pregnancies and births at 41 weeks. In other words, you have to include the healthy, living babies that have not been born yet in your denominator.

In other words, you have to include the healthy, living babies that have not been born yet in your denominator.

When researchers began using this new formula to figure out stillbirth rates, they found something very surprising—the risk of stillbirth decreased throughout pregnancy, until it reached a low point at 37-38 weeks, after which the risk started to rise again.

This finding—that the risk of stillbirth decreases throughout pregnancy, and then increases sometime after 37-38 weeks—has been found many times by different researchers in different countries. This phenomenon is called the “U-shaped curve” of stillbirth. In other words, there are higher rates of stillbirth earlier in pregnancy, then they go down until around 37-38 weeks, after which they rise again.

Because the risk of stillbirth starts to go up even more at 40, 41, and 42 weeks, some researchers argue that although 40 weeks and 3-5 days may be the physiological length of pregnancy, 40 weeks may be the functional length of a pregnancy.

In other words, the average pregnancy normally lasts about 40 weeks and 5 days, but in some researchers’ opinion, because of the increased risk of stillbirth and newborn death, 40 weeks may be as long as a pregnancy should go.

And although the stillbirth rates may seem low overall, if you happen to be a parent who experiences the 1 in 315 event at 42 weeks (Muglu et al. 2019), then the risk doesn’t seem so low anymore.

Actual stillbirth rates vs. open-ended stillbirth ratesEven after researchers began using the new way of calculating stillbirth rates, there was still controversy about the best way to calculate this new formula for measuring stillbirth rates.

Different than what Yudkin proposed in 1987, some researchers preferred an “open-ended” stillbirth rate (also known as the “prospective risk of stillbirth”). An open-ended stillbirth rate at 40 weeks would tell us what a pregnant person’s risk of stillbirth was for any time after 40 weeks, if she let the pregnancy continue indefinitely.

Other researchers argued that most people (and doctors!) don’t want to know what the risk of stillbirth would be if a pregnant person chose to let the pregnancy continue on and on! (Hilder et al., 2000). They just want to know what the risk would be if they waited one more week until the next appointment, or even a few days.

But the “open-ended” stillbirth rate tells you what your risk of stillbirth at 40 weeks would be if you include babies born not just at 40 weeks, but 41 weeks, 42 weeks, 43 weeks, and on! (Boulvain et al., 2000).

In the end, you will find that stillbirth rates vary from study to study, depending on whether the researchers report the actual stillbirth rate, or the open-ended stillbirth rate.

So what is the risk of stillbirth as you go past your due date?Since the late 1980’s, there have been at least 12 large studies that looked at the risk of stillbirth during each week of pregnancy. Some of the researchers used open-ended stillbirth rates, and some of them used actual stillbirth rates.

All of the researchers found a relative increase in the risk of stillbirth as pregnancy advanced.

To get an accurate picture of stillbirth in people who go past their due date, it would be best to look at studies that took place in more recent times. I’ve chosen 3 of the most recent studies to show you from Norway, Germany, and the U.S. To see all of the other studies, click to view the entire table here.

All 3 of these studies used the actual stillbirth rate—not the open-ended stillbirth rate. Two studies used ultrasound to calculate gestational age, and one study used the LMP.

The largest meta-analysis to date on risks of stillbirth and newborn death at each week of term pregnancies was published in 2019 (Muglu et al. 2019). A meta-analysis is when researchers take multiple studies and combine all the data together into one big “meta” study. The researchers included 13 studies (15 million pregnancies, nearly 18,000 stillbirths). All of the studies were conducted in countries defined as “high-income” by the World Bank.

The risk of stillbirth per 1,000 was 0.11, 0.16, 0.42, 0.69, 1.66, and 3.18 at 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, and 42 weeks of pregnancy, respectively. Based on their data, Muglu et al. (2019) calculated the “number needed to harm” by waiting for labor for one more week in order to experience one additional stillbirth. To experience one additional stillbirth, there would need to be at least 2,367 people waiting for labor for one more week starting at 39 weeks. At 40 weeks, 1,449 people would have to wait for labor for one more week to experience one additional stillbirth. At 41 and 42 weeks, only 604 and 315 people, respectively, would have to wait for labor for one more week to experience one additional stillbirth.

The researchers also found evidence that health care systems are failing Black mothers and babies—an alarming but common theme in health care research. Black mothers were 1.5 to 2 times more likely than White mothers to have a stillbirth at every week of pregnancy.

When they looked only at low-risk pregnancies, the risk of stillbirth was 0. 12, 0.14, 0.33, 0.80, and 0.88 at 38, 39, 40, 41, and 42 weeks of pregnancy. Low-risk pregnancy was defined as pregnancies with a single baby, no congenital abnormalities, and no medical conditions in the mother.

12, 0.14, 0.33, 0.80, and 0.88 at 38, 39, 40, 41, and 42 weeks of pregnancy. Low-risk pregnancy was defined as pregnancies with a single baby, no congenital abnormalities, and no medical conditions in the mother.

There was no additional risk of newborn death when giving birth between 38 and 41 weeks, but the risk of newborn death did increase beyond 41 weeks.

So, although most researchers have found an increase in stillbirth rates in the late term and post term period, some might consider the “absolute” increase in risk to be small until 41 weeks, after which it reaches about 0.80-1.66 out of 1,000, depending on the mother’s risk factors for stillbirth.

What factors can increase the risk of stillbirth?Researchers have found several factors are related to a higher risk of stillbirth:

Post-term babies who are small for gestational age (body weight <10th percentile) have a 6-7 times higher chance of stillbirth and newborn death than post-term babies who are not small for gestational age.

- Also, small for gestational age babies are often growth restricted at the 18-week ultrasound. So, the gestational age for these babies is often under-estimated.

- This means that babies who are small for gestational age may be more post-term than we realize they are—increasing their risk while also leaving us unaware of their true gestational age (Morken et al., 2014).

Other factors that do not necessarily cause stillbirth but may increase the risk of stillbirth, in general, include:

- Belonging to an ethnic group at increased risk for stillbirth* (Ananth et al., 2009; Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011)

- Being pregnant with your first baby (Huang et al., 2000; Smith, 2001b; Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011; Flenady et al., 2011)

- Fewer than four prenatal visits or no prenatal care (Huang et al., 2000; Flenady et al., 2011)

- Low socioeconomic status (Huang et al., 2000; Flenady et al., 2011)

- A body mass index (BMI) over 25 to 30 (Huang et al.

, 2000; Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011; Flenady et al., 2011)

, 2000; Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011; Flenady et al., 2011) - Smoking (Morken et al., 2014; Flenady et al., 2011)

- Pre-existing diabetes (Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011; Flenady et al., 2011)

- Pre-existing hypertension (Flenady et al., 2011)

- Older maternal age (≥40 years) (Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011)

- Not living with a partner (Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011)

- History of previous stillbirth (Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011)

- Being pregnant with multiples (Stillbirth Collaborative, 2011)

* Racism, including the effects of prejudice and institutional racism, can increase the risk of poor outcomes, including stillbirth, in certain populations (Giscombe and Lobel, 2005).

Of course, parents can still experience the stillbirth of a child even when none of these risk factors are present. As many as a third of all stillbirths that take place before labor have no known cause (Warland & Mitchell, 2014). To read more about theories of unexplained stillbirth, read this article here.

To read more about theories of unexplained stillbirth, read this article here.

We have heard some clinicians state that the “aging of the placenta” is a potential cause of stillbirths with no official known cause. However, up until recently, there was no research on this topic.

In 2017, researchers published the first study looking at biological markers of aging in placentas. In this study, researchers in Australia collected placentas from 34 people who gave birth between 37-39 weeks of pregnancy, 28 people who gave birth between 41-42 weeks, and 4 people who experienced stillbirths between 32 and 41 weeks (Maiti et al. 2017).

Five or more tissue samples were removed from each placenta, and the samples were analyzed using a variety of biochemical tests. For example, one of the tests looked for a marker of DNA/RNA damage that was previously observed in other aging tissues, such as the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. There was a significant increase in DNA/RNA damage in late-term and stillbirth placentas compared to the placentas from 37-39 weeks.

Overall, the analysis of the placentas from the 41-42 week pregnancies and from the stillbirths showed increased signs of aging, with decreased ability to transport nutrients to the baby and waste products away from the baby, compared to the placentas from the earlier term births. The rate of placental aging varied in different pregnancies, and the authors stated that not all of the 41-42 week placentas showed signs of aging. We reached out to the authors to find out more, and they told us that one-third of the 41-42 week placentas showed increased signs of aging compared to the 37-39 week placentas. This means that two-thirds of the 41-42 week placentas did not show signs of aging.

Interestingly, the authors say that in the future it may be possible to predict which babies are at increased risk of stillbirth by measuring markers of placental aging in the mother’s blood. You can watch a 10-minute video describing the findings of this emerging research here.

Induction for Going Past Your Due DateCheck out our Signature Article on Inducing for Due Dates here for more information about the Pros/Cons of induction versus waiting for labor.

Makarov I.O. • Prematurity

Ultrasound Scanner WS80

An ideal instrument for prenatal examinations. Unique image quality and a full range of diagnostic programs for an expert assessment of a woman's health.

Premature births are those that occur between 28 and 37 weeks of gestation and the fetus weighs between 1000 and 2500 g.

and the fetal weight is 500 g or more, and the newborn survives for 7 days, then the birth is considered premature with an extremely low fetal weight.

Causes of preterm birth

Risk factors for preterm birth are: low socioeconomic status; unsettled family life; young age; abuse of nicotine, alcohol, drugs; previous abortions, premature births and spontaneous miscarriages; urinary tract infections; inflammatory diseases of the genital organs; severe somatic diseases; violations of the structure and function of the genital organs. The complicated course of this pregnancy also plays an important role in the occurrence of premature birth. Particular attention should also be paid to infectious diseases suffered during this pregnancy.

Particular attention should also be paid to infectious diseases suffered during this pregnancy.

Prematurity, which occurs at 22-27 weeks, accounts for 5% of their total. First of all, these births are caused by isthmic-cervical insufficiency, infection of the fetal membranes by their premature rupture. In this situation, the lungs of the fetus do not yet reach the necessary maturity, which does not allow to adequately provide the respiratory function of the newborn. It is not always possible to achieve acceleration of lung maturation with the help of drugs. As a result, the outcome of childbirth for a newborn in such a situation is the most unfavorable.

Prematurity at 28-33 weeks' gestation has a wider range of causes. The lungs of the fetus in these terms are also not yet mature enough, however, the appointment of certain medications in a number of cases makes it possible to accelerate their maturation. In this regard, accordingly, the outcome of childbirth for a newborn in these terms of pregnancy may be more favorable. The prognosis of more favorable outcomes of preterm birth increases at 34-37 weeks of gestation.

The prognosis of more favorable outcomes of preterm birth increases at 34-37 weeks of gestation.

Symptoms of preterm labor

Distinguish between threatening, incipient and incipient preterm labor. Threatening preterm birth is characterized by intermittent pain in the lower back and lower abdomen against the background of increased uterine tone. In this case, the cervix remains closed. When starting premature birth, there are usually cramping pains in the lower abdomen, accompanied by a regular increase in the tone of the uterus (contractions). The cervix is shortened and opened. Often there is a premature rupture of amniotic fluid.

Preterm birth is characterized by: untimely discharge of amniotic fluid; weakness of labor activity, discoordination or excessively strong labor activity; fast or rapid childbirth or, conversely, an increase in the duration of labor; bleeding due to placental abruption; bleeding in the afterbirth and early postpartum periods due to retention of parts of the placenta; inflammatory complications, both during childbirth and in the postpartum period; fetal hypoxia.

Treatment of pregnant women

If symptoms appear that indicate the possibility of preterm labor, treatment should be differentiated, since in the beginning of labor, treatment can be carried out aimed at maintaining the pregnancy, and with the onset of labor, such treatment is no longer effective. To reduce the excitability of the uterus and reduce its contractile activity, the following is prescribed: bed rest; sedatives; antispasmodic drugs. To reduce the direct contractile activity of the uterus, magnesium sulfate and ?-mimetics (partusisten, ginipral) are prescribed.

For the treatment of pregnant women who have threatened preterm labor, non-drug physiotherapy can also be used, such as electrorelaxation of the uterus by exposing it to an alternating sinusoidal current with a frequency in the range from 50 to 500 Hz and a current strength of up to 10 mA. Electrorelaxation is carried out using the apparatus "Amplipulse-4". This one is highly effective and is considered safe for mother and fetus. With threatening premature birth, acupuncture is also successfully used as an independent method in combination with drugs. With the threat of preterm birth, it is also important to prevent respiratory disorders (respiratory distress syndrome) in newborns by prescribing glucocorticoid drugs to the pregnant woman. The fact is that in premature newborns, respiratory problems occur due to a lack of surfactant in the immature lungs. Surfactant is a substance that coats the alveoli of the lungs, promotes their opening during inhalation and prevents the alveoli from collapsing during exhalation. A small amount of surfactant is produced already from 22-24 weeks of intrauterine life, however, it is very quickly consumed after preterm birth, and its more or less adequate reproduction is possible only after 35 weeks under the influence of glucocorticoids administered to the pregnant woman or acceleration of surfactant synthesis is observed. Contraindications for the appointment of dexamethasone are: peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum, circulatory failure III degree, endocarditis, nephritis, active form of tuberculosis, severe forms of diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, severe preeclampsia.

With threatening premature birth, acupuncture is also successfully used as an independent method in combination with drugs. With the threat of preterm birth, it is also important to prevent respiratory disorders (respiratory distress syndrome) in newborns by prescribing glucocorticoid drugs to the pregnant woman. The fact is that in premature newborns, respiratory problems occur due to a lack of surfactant in the immature lungs. Surfactant is a substance that coats the alveoli of the lungs, promotes their opening during inhalation and prevents the alveoli from collapsing during exhalation. A small amount of surfactant is produced already from 22-24 weeks of intrauterine life, however, it is very quickly consumed after preterm birth, and its more or less adequate reproduction is possible only after 35 weeks under the influence of glucocorticoids administered to the pregnant woman or acceleration of surfactant synthesis is observed. Contraindications for the appointment of dexamethasone are: peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum, circulatory failure III degree, endocarditis, nephritis, active form of tuberculosis, severe forms of diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, severe preeclampsia. Such prevention of respiratory disorders makes sense at gestational ages of 28-35 weeks. Prevention is repeated after 7 days 2-3 times.

Such prevention of respiratory disorders makes sense at gestational ages of 28-35 weeks. Prevention is repeated after 7 days 2-3 times.

Management of preterm labor

Adequate analgesia is essential in the management of preterm labor. Due to the fact that most of the complications in preterm birth, both in the mother and the fetus, are due to a violation of the contractile activity of the uterus, constant monitoring of uterine contractions and the condition of the fetus is mandatory. The duration of preterm labor is usually less than timely labor due to the increased rate of cervical dilatation. This is mainly due to the fact that in such situations isthmic-cervical insufficiency occurs more often, and with a small mass of the child, high uterine activity and intensity of contractions are not required for his birth. If the contractile activity of the uterus during preterm labor is normal, then expectant tactics are used in the management of labor. Prevention of fetal hypoxia is regularly carried out, epidural anesthesia is used. In order to reduce birth trauma during the period of exile, they provide benefits without perineal protection.

In order to reduce birth trauma during the period of exile, they provide benefits without perineal protection.

Detection of premature rupture of membranes in preterm pregnancy can be somewhat difficult due to oligohydramnios and due to heavy discharge due to concomitant colpitis. In this regard, it is advisable to use the express method - amnitest. In case of premature rupture of membranes, expectant management is usually followed, controlling the possible development of infection, since the most important fact to be taken into account in such a situation is, first of all, the possibility of infection, which has a decisive influence on the management of pregnancy. Expectant tactics are most preferable at small terms of pregnancy.

If a premature rupture of the membranes is detected in the case of a premature pregnancy, the pregnant woman is hospitalized. The patient needs bed rest with a daily change of linen and good nutrition. Doctors exercise strict control over the health of the mother and fetus. They measure the circumference of the abdomen and the height of the fundus of the uterus above the womb, assess the quantity and quality of leaking water, determine the pulse rate, body temperature and heart rate of the fetus every 4 hours. It is necessary to determine the content of leukocytes every 12 hours with an analysis of the leukocyte blood count. Cervical cultures and vaginal swabs are monitored every 5 days. Tocolytic drugs are usually prescribed for premature rupture of the membranes in the case of threatened and incipient preterm labor. If labor activity has already begun on its own, then it is not advisable to suppress it. Antibiotics for premature rupture of the membranes are used in case of a risk of developing inflammatory complications, as well as with prolonged use of glucocorticoids, with isthmic-cervical insufficiency, if a pregnant woman has anemia, pyelonephritis and other chronic infectious diseases.

They measure the circumference of the abdomen and the height of the fundus of the uterus above the womb, assess the quantity and quality of leaking water, determine the pulse rate, body temperature and heart rate of the fetus every 4 hours. It is necessary to determine the content of leukocytes every 12 hours with an analysis of the leukocyte blood count. Cervical cultures and vaginal swabs are monitored every 5 days. Tocolytic drugs are usually prescribed for premature rupture of the membranes in the case of threatened and incipient preterm labor. If labor activity has already begun on its own, then it is not advisable to suppress it. Antibiotics for premature rupture of the membranes are used in case of a risk of developing inflammatory complications, as well as with prolonged use of glucocorticoids, with isthmic-cervical insufficiency, if a pregnant woman has anemia, pyelonephritis and other chronic infectious diseases.

Peculiarities of premature newborns

A child, after premature birth, has signs of immaturity: a lot of cheesy lubrication, insufficient development of subcutaneous adipose tissue, fluff on the body, short hair on the head, soft ear and nasal cartilages, nails do not go beyond the fingertips, the umbilical ring is located closer to the pubis, in boys the testicles are not lowered into the scrotum, in girls the clitoris and labia minora are not covered by large ones, the cry of the child is weak. Premature newborns do not tolerate various stressful situations that arise in connection with the onset of extrauterine life. Their lungs are not yet mature enough to carry out adequate breathing, the digestive tract cannot yet fully assimilate some of the necessary substances contained in milk.

Premature newborns do not tolerate various stressful situations that arise in connection with the onset of extrauterine life. Their lungs are not yet mature enough to carry out adequate breathing, the digestive tract cannot yet fully assimilate some of the necessary substances contained in milk.

The resistance of premature newborns to infection is also weak, due to an increase in the rate of heat loss, thermoregulation is disturbed. Increased fragility of blood vessels is a prerequisite for the occurrence of hemorrhages, especially in the ventricles of the brain and the cervical spinal cord. The most common and severe complications for preterm infants are respiratory distress syndrome, intracranial hemorrhage, infections, and asphyxia. In children born to mothers with various extragenital diseases, preeclampsia or fetoplacental insufficiency, there may be signs of intrauterine growth retardation.

However, modern methods of diagnosis and intensive care of newborns allow in a number of cases to optimize the nature of perinatal outcomes in preterm birth.

WS80 Ultrasound Scanner

The ideal instrument for prenatal examinations. Unique image quality and a full range of diagnostic programs for an expert assessment of a woman's health.

Premature birth. What do you need to know about them?

According to the recommendations of the World Health Organization, preterm births are considered to occur between the 22nd and 38th weeks of pregnancy.

If we talk about the prevalence of this pathology, then its frequency ranges from 4 to 8% in countries with a developed healthcare system and up to 10-12% in countries that are somewhat lagging behind in terms of the level of medicine. Specifically, in the city of Minsk, the frequency of preterm birth is approximately 3-4%.

Where is the problem?

Of course, the etiology of triggering the mechanism of preterm labor has not been fully studied. The nature of this phenomenon is very diverse and many-sided. However, experts identify a number of factors that play a leading role in the occurrence of this pathology.

The most common cause of preterm labor is infectious factor . That is, any, even the most banal, for example, a respiratory infection, can trigger the mechanism of premature birth. How does this happen? As a result of the infection in the body, a large amount of biologically active substances are released, which trigger a cascade of various reactions leading to contractile activity of the uterus. Also, the infection can lead to chorioamnionitis (inflammation of the membranes), which provokes premature opening of the membranes and the outflow of amniotic fluid.

Against the background of intrauterine infection, polyhydramnios often occurs, which also provokes premature outflow of water.

The next most common cause of preterm birth is endocrine disorders . The most common is the pathology of the thyroid gland (especially hypofunction), then the pancreas. Also recently there has been an increase in the incidence of gestational diabetes (diabetes that first occurs during pregnancy). In addition, dysfunction of the placenta can be associated with a violation of its structure, improper attachment, and even more often with extragenital pathologies of the mother, leading to feto-placental insufficiency.

In addition, dysfunction of the placenta can be associated with a violation of its structure, improper attachment, and even more often with extragenital pathologies of the mother, leading to feto-placental insufficiency.

The so-called uterine factors occupy a separate niche in the causes of premature birth. These include fibroids (the myomatous node prevents the normal growth of the uterus), intrauterine synechia, anomalies in the development of the uterus, etc. Often, the cause of premature birth is isthmic-cervical insufficiency. Normally, the muscular ring of the cervix (internal and external os) holds the fetus in the uterine cavity during the gestation period. However, with the development of isthmic-cervical insufficiency (ICI), the muscular ring does not cope with this important function, resulting in the opening of the cervix. The dilated cervix, in turn, cannot hold a growing fetal egg, which poses a threat of miscarriage or premature birth.

Other causes include central placenta previa, pelvic or incorrect (transverse or oblique) position of the fetus, intoxication of the woman's body, immunological factors that are currently least studied. In rare cases, premature birth can be caused by genetic abnormalities, severe extragenital pathologies of the mother.

In rare cases, premature birth can be caused by genetic abnormalities, severe extragenital pathologies of the mother.

The social factor also plays an important role: alcohol, smoking, unhealthy lifestyle are very often the cause of premature birth.

It is worth noting that in most cases you have to deal with a combination of the above reasons.

When the need arises

In some cases, for medical reasons, doctors have to decide on early delivery. This can be caused by both indications from the mother and from the fetus. The indications on the part of the woman in labor are the conditions in which the further continuation of the pregnancy may pose a threat to her life and health. Such situations may arise in connection with severe preeclampsia, arterial hypertension, long-term treatment-resistant pyelonephritis, retinal detachment, etc.

As for indications from the fetus, these will be all situations in which it is in a state of acute or decompensated chronic hypoxia.

Preterm delivery is very common in multiple pregnancies: about 40-45% of twins and 100% of triplets. However, here we are talking about planned medical intervention.

Symptoms and course of preterm labor

Clinical symptoms of preterm labor are usually pain in the lower abdomen and in the lumbar region, which can be both permanent and cramping. A sign of the onset of labor can also be abundant mucous discharge from the vagina, which can sometimes be slightly stained with blood.

On palpation, the uterus may be toned or excitable. During vaginal examination, the cervix may be shortened, softened. The cervical canal can be either closed or open.

When childbirth is already in progress, a woman feels cramping pains in the lower abdomen, the intensity and duration of which is constantly increasing. The cervix gradually shortens, softens and opens.

Premature rupture of amniotic fluid occurs with or without cervical dilatation. Often it precedes the development of contractions.

Often it precedes the development of contractions.

As a rule, preterm labor lasts longer than usual, which is due to the unpreparedness of the internal mechanisms of the female body that regulate labor forces and determine the normal course of urgent labor.

In preterm labor, weakness and incoordination of labor are often observed. The rapid course of preterm labor is less common, usually with intrauterine infection of the fetus.

Complications also occur more frequently in the postpartum period than in urgent deliveries. The most common are hypotonic bleeding (impaired uterine contractility), retention of parts of the placenta in the uterus, complications of an infectious nature (metroendometritis, thrombophlebitis).

Important to know! At the onset of preterm labor, it is very important to be in the hospital as soon as possible, as doctors need to prevent the respiratory distress syndrome of the newborn - intrauterine prevention of respiratory disorders.

Management of preterm labor

Management of preterm labor turns out to be more gentle to the fetus and the mother's birth canal.

During childbirth, all violations of labor activity are regulated. Anesthetization of childbirth, including medical sleep, is often used. With signs of chronic infection, prevention of intrauterine infection is carried out. There is also continuous monitoring of laboratory tests and dynamic cardiomonitoring of the fetus.

Why is preterm birth dangerous?

The main danger of preterm birth is that babies are born prematurely. That is, further we are faced with the problem of premature babies, the risk of dying or acquiring any disease is higher in them than in full-term ones.

All organs and systems of such babies: brain, respiratory organs, liver, etc. still immature. The digestive tract is not yet able to fully absorb the necessary nutrients. Premature babies are very susceptible to infections, their blood vessels are characterized by increased fragility, their thermoregulatory function does not work at all, and immunity is not fully formed.

Naturally, the earlier a child is born, the more he is unfit for life in the outside world.

It is most difficult for children who were born with extremely low body weight: from 500 g to 1 kg. These are births from the 22nd to the 28th week of pregnancy. Most of these babies may suffer from disorders of the musculoskeletal system, diseases of the psycho-neurological profile. In addition, premature babies are at risk for developing blindness and deafness.

Better prospects for babies born with low birth weight: 1 to 1.5 kg (delivery after 28 weeks of gestation). With a developed healthcare system and proper care, such children almost always survive, and health problems rarely occur.

After childbirth

After preterm birth, it is required to find out their cause, for this various additional examinations are carried out: microbiological studies, histological examination of the placenta, genetic examination, etc.

family planning center.