Milk allergy and diaper rash

Cow's Milk Allergy Is a Major Contributor in Recurrent Perianal Dermatitis of Infants

ISRN Pediatr. 2012; 2012: 408769.

Published online 2012 Sep 3. doi: 10.5402/2012/408769

, 1 ,*, 1 , 1 and 2

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Background. Recurrent perianal inflammation has great etiologic diversity. A possible cause is cow's milk allergy (CMA). The aim was to assess the magnitude of this cause. Subjects and Methods. This follow up clinical study was carried out on 63 infants with perianal dermatitis of more than 3 weeks with history of recurrence. Definitive diagnosis was made for each infant through medical history taking, clinical examination and investigations including stool analysis and culture, stool pH and reducing substances, perianal swab for different cultures and staining for Candida albicans. Complete blood count and quantitative determination of cow's milk-specific serum IgE concentration were done for all patients. CMA was confirmed through an open withdrawal-rechallenge procedure. Serum immunoglobulins and CD markers as well as gastrointestinal endoscopies were done for some patients. Results. Causes of perianal dermatitis included CMA (47.6%), bacterial dermatitis (17.46%), moniliasis (15.87%), enterobiasis (9.52%) and lactose intolerance (9.5%). Predictors of CMA included presence of bloody and/or mucoid stool, other atopic manifestations, anal fissures, or recurrent vomiting. Conclusion. We can conclude that cow's milk allergy is a common cause of recurrent perianal dermatitis. Mucoid or bloody stool, anal fissures or ulcers, vomiting and atopic manifestations can predict this etiology.

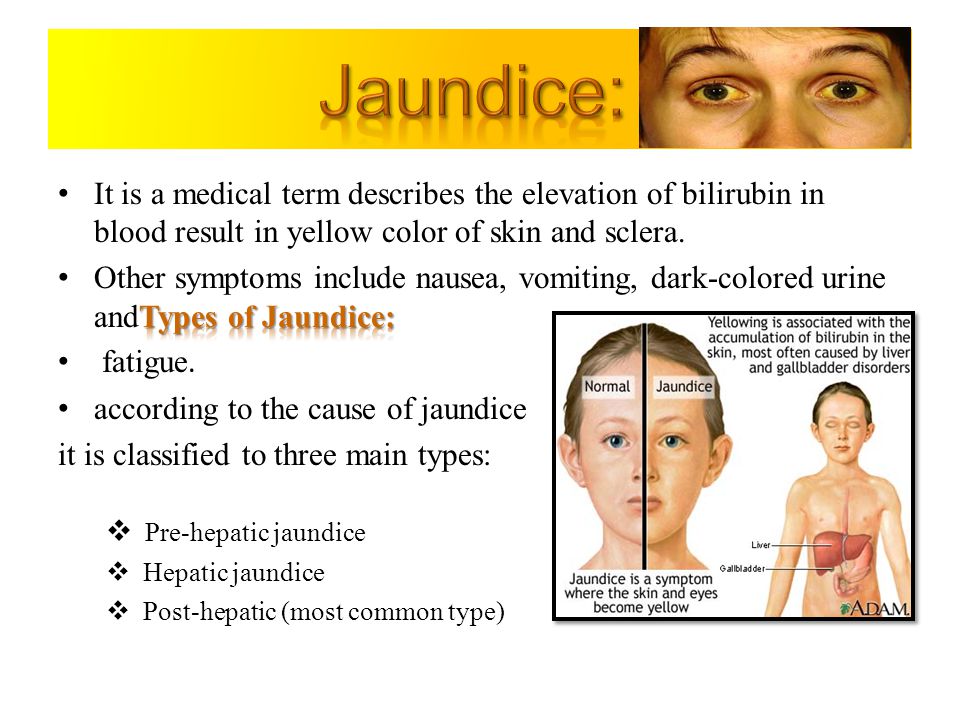

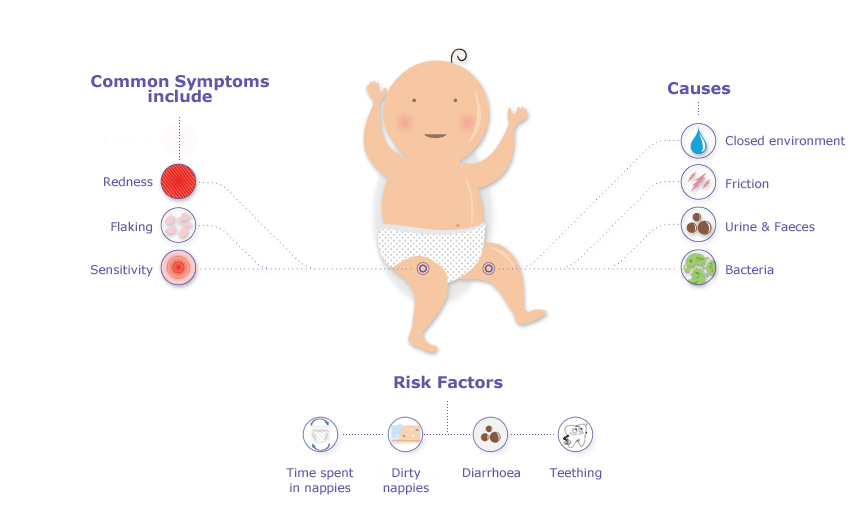

Perianal dermatitis is probably the most common cutaneous disorder of the genitoanal area [1]. Diaper dermatitis is observed most frequently in infants at 9–12 months of age [2]. It has a multifactorial etiology and high chronicity [3, 4]. Its prevalence is not greatly different between genders or among races [5]. Signs of diaper dermatitis including erosions have been noted as early as the first 4 days of life [6–8].

Signs of diaper dermatitis including erosions have been noted as early as the first 4 days of life [6–8].

There have been only a few studies on the etiology and causative factors in anal eczema [9–11]. The patient's diet may be a factor in the development of diaper dermatitis [12]. Breastfed infants are less likely to develop moderate to severe diaper dermatitis relative to formula-fed infants [2, 13]. Adverse reactions to cow's milk are frequent (2–7%) in the first year of life and may include cutaneous (50–60%), gastrointestinal (50–60%), or respiratory (20–30%) affection [14]. Streptococcal perianal infections were reported as a frequent cause of such a recurrent condition [15].

The aim of this work was to find out the different causes of recurrent perianal dermatitis with focus on the magnitude of cow's milk allergy and the possible clinical or laboratory predictors of this etiology.

This follow-up clinical study was carried out on 63 infants with perianal dermatitis that persisted for more than 3 weeks and with history of recurrence. They represented 5.16% of 1220 patients presenting with the main complaint of perianal inflammation. They were seen among 42234 infants presenting to the Out-Patient Clinics, Children's Hospital, Ain Shams University (2.89%). They were 33 males and 30 females. All of them received different systemic and local remedies for the dermatitis including steroids, antifungal, and/or soothing agents prior to presentation with recurrence of their problem after either full or partial response. The study was conducted between January 2009 and December 2010. Study group was diagnosed and followed up in the Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit, Children's Hospital, Ain Shams University.

They represented 5.16% of 1220 patients presenting with the main complaint of perianal inflammation. They were seen among 42234 infants presenting to the Out-Patient Clinics, Children's Hospital, Ain Shams University (2.89%). They were 33 males and 30 females. All of them received different systemic and local remedies for the dermatitis including steroids, antifungal, and/or soothing agents prior to presentation with recurrence of their problem after either full or partial response. The study was conducted between January 2009 and December 2010. Study group was diagnosed and followed up in the Pediatric Gastroenterology Unit, Children's Hospital, Ain Shams University.

Inclusion criteria:

age between 1–24 months,

perianal erythema for more than 3 weeks,

recurrent nature (more than 2 occasions).

Exclusion criteria:

surgical anorectal procedures,

napkin dermatitis not reaching the anal verge.

After approval of the ethics committee, the informed consents were taken from parents or guardians with explanation of the study and its procedures.

Each patient was subjected to the following.

(1) Medical history taking with special emphasis on description of perianal lesions regarding age of onset, duration of last attack, recurrence rate. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms included vomiting, constipation defined according to Hyams et al., [16], diarrhea defined according to Gishan [17], abdominal distension, presence of blood or mucus in the stools by naked eyes. History of recurrent infections, atopic features in the patients, and family history of erythema, atopy, and immune deficiency were also included.

(2) Careful clinical examination was conducted including weight and length (that were plotted against growth charts), description of perianal erythema (diameter in centimeters from anal verge to the farthest outer point not including satellites, presence of satellites, ulcers or anal fissures).

(3) Laboratory investigations at presentation include the following.

Stool analysis for microscopic pus cells, red blood cells, and stool culture on aerobic and anaerobic media.

Stool for culture as obtained through an anal swab to avoid contamination from the perianal area.

Stool for culture as obtained through an anal swab to avoid contamination from the perianal area.Stool pH and reducing substances.

Perianal swab from the erythematous lesion with culture and sensitivity with staining for Candida albicans.

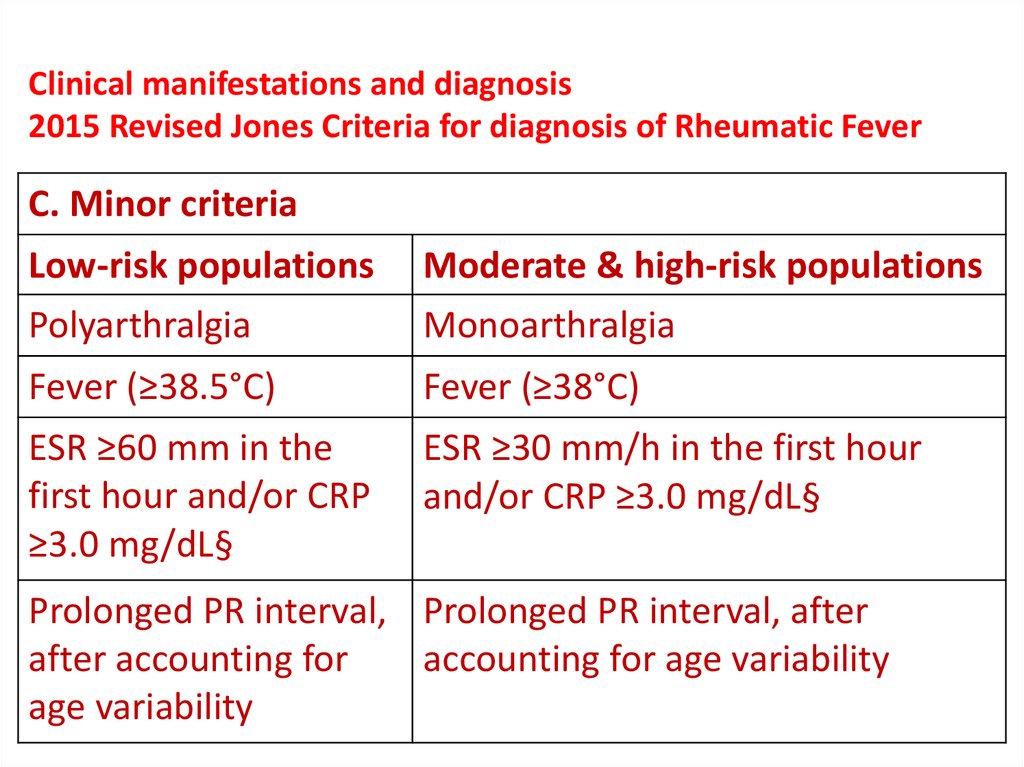

Complete blood count (CBC) (By Coulter 1660) and ESR.

Serum Immunoglobulins A, G, and M

CD markers 3, 4, and 8 when indicated in lymphopenic patients.

(4) Quantitative determination of allergen specific IgE concentration in serum against whole cow milk protein [18] was performed by enzyme-allergosorbent-test (DR-Fooke, laboratories GmbH, Mainstrable 85).

(5) Colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy in cases suspected of having Crohn's disease in presence of significant growth failure (weight and length below 5th centile for age) mucoid and/or bloody diarrhea or elevated ESR.

Diagnosis of cow milk allergy (CMA) was based on the results of withdrawal rechallenge [19]. Before getting the test results, cow's milk elimination diet was instituted to all patients and their lactating mothers (if breast fed) for 4 weeks with clinical assessment of erythema and other clinical features. An open rechallenge was started and patients were followed up for another 4 weeks with assessment of recurrence of dermatitis and other clinical features. The list of foods and food ingredients that are avoided were described according to Zeiger et al., [20]. In infants below one year of age, a hypoallergic amino-acid-based formula was prescribed when breast feeding was not possible.

Before getting the test results, cow's milk elimination diet was instituted to all patients and their lactating mothers (if breast fed) for 4 weeks with clinical assessment of erythema and other clinical features. An open rechallenge was started and patients were followed up for another 4 weeks with assessment of recurrence of dermatitis and other clinical features. The list of foods and food ingredients that are avoided were described according to Zeiger et al., [20]. In infants below one year of age, a hypoallergic amino-acid-based formula was prescribed when breast feeding was not possible.

Diagnosis of candidal infection was based on Dixon et al. [21] and Taschdjian et al., [22]. Diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) was based on Ghoshal et al. [23]. Diagnosis of lactose intolerance was done through breath hydrogen test and stool pH and reducing substances [24, 25].

The collected data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 15.0. 1 for windows; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, 2001). Student's t-test was used to compare mean values of different groups and X 2 test was used to compare frequency of qualitative variables of different groups. Regression analysis was used to find out the most important predictive parameters for the diagnosis of underlying cow's milk allergy.

1 for windows; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, 2001). Student's t-test was used to compare mean values of different groups and X 2 test was used to compare frequency of qualitative variables of different groups. Regression analysis was used to find out the most important predictive parameters for the diagnosis of underlying cow's milk allergy.

The present study was conducted on 63 infants with a mean age of 15.01 ± 3.26 months. They were 33 males and 30 females.

Duration of the last attack ranged between 12 and 30 days with a mean of 20.1 ± 3.5 days. Number of recurrences ranged between 2 and 6 with a mean of 3.6 ± 1.3 attacks. Age at onset of erythema ranged between 4 and 20 months with a mean of 11.2 ± 3.7 months. There was a positive history of vomiting in 33 patients (52.4 %), diarrhea in 30 patients (47.6%), constipation in 4 patients (6.3%), and abdominal distension in 27 patients (42.8%). Macroscopic assessment of stool showed blood in 32 patients (50. 8%), pus in 40 patients (63.5%), and mucus in 42 patients (66.7%). Atopic features were present in 25 patients (39.7%), family history of erythema in 19 patients (30.1%), and family history of atopy in 23 patients (36.5%).

8%), pus in 40 patients (63.5%), and mucus in 42 patients (66.7%). Atopic features were present in 25 patients (39.7%), family history of erythema in 19 patients (30.1%), and family history of atopy in 23 patients (36.5%).

On examination of the perianal area, extent of erythema from anal verge ranged between 1.5 and 6 cm with a mean of 3.6 ± 1.2 cm. Ulcers were present in 42 patients (66.7%), satellites in 20 patients (31.7%), and anal fissures in 27 patients (42.8%).

Microscopic stool assessment showed pus cells in 30 patients (47.6%) and RBCs in 34 patients (54%). Test for reducing substances in stools was positive in 12 patients (19%). Stool culture revealed growth of pathogenic organisms in 15 patients (23.8%).

The definite causes of perianal erythema included cow's milk allergy in 30 patients 47.6%, monilial napkin dermatitis in 10 patients 15.87%, lactose intolerance in 6 patients 9.5%, bacterial dermatitis in 11 patients 17.46% (primary immune deficiency in 2 patients 3. 22%, small bowel bacterial overgrowth in 3 patients 4.76% and without an evident cause in 6 cases 9.52%). Six patients (9.52%) showed Entrobius vermicularis infestation with full recovery of dermatitis after eradication of infestation and recovered. In the 16 patients with monilial napkin dermatitis, only 4 cases were positive for oral moniliasis. All cases with bacterial dermatitis were positive for stool culture as well. 8/11 patients had beta hemolytic streptococci (50% concordance with stool culture) and 3 patients had Klebsiella (100% concordance with stool culture)

22%, small bowel bacterial overgrowth in 3 patients 4.76% and without an evident cause in 6 cases 9.52%). Six patients (9.52%) showed Entrobius vermicularis infestation with full recovery of dermatitis after eradication of infestation and recovered. In the 16 patients with monilial napkin dermatitis, only 4 cases were positive for oral moniliasis. All cases with bacterial dermatitis were positive for stool culture as well. 8/11 patients had beta hemolytic streptococci (50% concordance with stool culture) and 3 patients had Klebsiella (100% concordance with stool culture)

Hygienic awareness for parents of patients with recurrent monilial napkin dermatitis led to improvement in 8/10 patients. However, 2 patients continued to have the recurrence for 6 months and improved spontaneously without a clear explanation. Patients with lactose intolerance responded immediately to oral lactase therapy and discontinued the enzyme after 6 months without recurrence. This means that pathology was secondary rather than primary. The 2 patients with severe combined immunodeficiency unfortunately died within 6 months. Patients with small bowel bacterial overgrowth responded adequately to medical therapy. Other bacterial dermatitis responded permanently to treatment with specific culture reported systemic antibiotics.

The 2 patients with severe combined immunodeficiency unfortunately died within 6 months. Patients with small bowel bacterial overgrowth responded adequately to medical therapy. Other bacterial dermatitis responded permanently to treatment with specific culture reported systemic antibiotics.

Vomiting, abdominal distension, atopic features in patients, ulcers, anal fissures, macroscopic and microscopic pus and blood as well as absence of satellites, reducing substances and pathogenic bacteria are all significantly in favor of CMA as a cause of perianal dermatitis ().

Table 1

Comparison of qualitative clinical and laboratory data between CMA group and other causes.

| CMA (30) | Others (33) | X 2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FH of erythema | 11 | 8 | 1. 15 15 | 0.2832 |

| FH of atopy | 11 | 12 | 0.0001 | 0.9801 |

| Vomiting | 25 | 8 | 22.00 | 0.0001 |

| Diarrhea | 27 | 28 | 0.38 | 0.5397 |

| Constipation | 3 | 1 | 1. 28 28 | 0.2572 |

| Abdominal distension | 21 | 6 | 17.23 | <0.0001 |

| Atopic features in patients | 23 | 2 | 32.73 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of ulcers | 26 | 16 | 10.31 | 0.0013 |

| Presence of satellites | 1 | 19 | 21. 34 34 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of anal fissures | 24 | 3 | 32.26 | <0.000 |

| Presence of macroscopic pus | 28 | 12 | 22.00 | <0.0001 |

| Presence of macroscopic blood | 27 | 5 | 35.22 | <0.0001 |

| Microscopic pus cells | 22 | 8 | 15. 18 18 | <0.0001 |

| Microscopic RBCS | 28 | 6 | 35.73 | <0.0001 |

| Stool reducing substances | 1 | 11 | 9.17 | 0.0025 |

| Pathogenic organisms | 2 | 13 | 9.28 | 0.0023 |

Open in a separate window

Serum level of IgE specific to cow's milk proteins was significantly higher in CMA compared to other groups (P < 0. 0001). Similarly stool pH was higher in CMA group compared to all other entities (P = 0.007). On the other hand, size of ulcers was smaller in CMA compared to others (P < 0.0001) ().

0001). Similarly stool pH was higher in CMA group compared to all other entities (P = 0.007). On the other hand, size of ulcers was smaller in CMA compared to others (P < 0.0001) ().

Table 2

Comparison of quantitative clinical and laboratory data between CMA group and other causes.

| CMA | Others | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.10 ± 0.75 | 15.09 ± 2.79 | 0.01 | 0.991 |

| Age of onset | 11. 10 ± 4.47 10 ± 4.47 | 11.24 ± 2.94 | −0.15 | 0.881 |

| RAST | 4.26 ± 1.28 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 18.15 | <0.0001 |

| Size of erythema | 2.69 ± 0.59 | 4.03 ± 1.20 | −5.50 | <0.0001 |

| Duration of last attack | 20.33 ± 3.58 | 20.00 ± 3.54 | 0. 37 37 | 0.712 |

| Recurrence rate of erythema | 3.56 ± 1.54 | 3.66 ± 1.16 | −0.29 | 0.772 |

| pH of stool | 6.68 ± 0.61 | 5.68 ± 1.87 | 2.782 | 0.007 |

Open in a separate window

The multiregression analysis showed that presence of microscopic or macroscopic blood in stool, presence of other atopic manifestations, anal fissures, presence of mucus in stool and occurrence of recurrent vomiting are the most important predictors of underlying cow's milk allergy as a cause of recurrent perianal dermatitis ().

Table 3

Regression analysis (logistic regression) of predictors of CMA as an underlying cause of perianal dermatitis.

| Score | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Age of onset of first lesion | 0.165 | 0.684 |

| Age at presentation | 0.135 | 0.713 |

| Family history of atopy | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Recurrent vomiting | 9. 000 000 | 0.003 |

| Abdominal distension | 3.571 | 0.059 |

| Atopic associations | 16.026 | <0.0001 |

| Ulcers | 8.048 | 0.005 |

| Satellites | 5.818 | 0.016 |

| Fissures | 16.000 | <0.0001 |

| Mucus | 15. 696 696 | <0.0001 |

| Blood | 25.138 | <0.0001 |

Open in a separate window

The outcome of the studied patients varied. So, tolerance was achieved 1 year after elimination of cow's milk in allergic patients with no more recurrence of dermatitis in all of them.

In the present work, cow's milk allergy was the most common cause of recurrent perianal inflammation (47.6%). This may be indirectly supported with the work of Doganci and Cengizlier [26] that perianal erythema was found among 58% of children with chronic constipation related to cow's milk allergy, 10.34% of whom improved on strict dietary elimination of cow's milk products in their nutrition. Intolerance of cow's milk can cause severe perianal lesions with pain on defecation and consequent constipation and that, in such cases, a diet free of cow's milk can rapidly resolve both the constipation and related disorders [27].

The protective role of breast feeding was described by Berg et al., [28], but they ascribed the effect to the lower stool pH and less irritating levels of fecal enzymes of infants who were breastfed.

The other definite causes of perianal erythema included in order bacterial dermatitis with its different underlying causes, monilial napkin dermatitis with or without oral affection, lactose intolerance regardless its cause and Entrobius vermicularis infestation.

These values are different from Kränke et al., [4] who found that, among 126 patients, the primary diagnosis in 68 patients was intertrigo/candidiasis (42.9%), atopic dermatitis (6.3%), pruritus ani (5.6%), psoriasis (3.2%), skin atrophy from steroid use (2.4%), lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (n = 2), herpes simplex (n = 1), and condylomata acuminata (n = 1). However, they included children and adults as well as acute and protracted cases in contrast with our study where we included infants with recurrent prolonged disease only.

The high frequency of candidal dermatitis agrees with Dixon et al., [21] who found that forty-one percent of 117 cases with napkin rash compared to 1 of 68 infants with normal skin grew Candida albicans in culture. A correlation between the severity of primary irritant diaper dermatitis and the level of Candida albicans in the feces has been reported [2, 29, 30].

Candidal infection, in our work, was not significantly associated with oral moniliasis. Singalavanija and Frieden [31] found that infants with candidal diaper dermatitis may also have Candida albicans in the oral mucosa. Moreover, Rasmussen [32] mentioned that candidal infection is a common complication of diaper dermatitis. This may explain the higher frequency of this pathology as it is not only a primary problem but also can complicate other causes.

The lack of contact dermatitis in our study may be based on the selection of those having perianal dermatitis only. Moreover, Shin [12] thought that as a result of the immaturity of the immunologic system of infants, true allergic contact dermatitis is rare in the diaper area.

Reporting of immunodeficiency in some cases in contrast to Kränke et al. [4] may be related to involvement of recurrent prolonged cases in our study. Paller [33] mentioned that if the condition is severe and persists, it may be the presenting feature of an immunodeficiency.

Shin [12] mentioned that perianal streptococcal disease shows sharply demarcated, bright erythema, and sometimes perirectal fissuring. In a hospital-based study performed by Mostafa et al. [34], in Egypt on 150 children with perianal dermatitis, hemolytic streptococci was found in 35.3% of the cases, half of which were of the group A hemolytic strain (17.3%) and half of which were nongroup A (18%).

The age range of patients in the current study was between 8 and 23 months (a mean age of 15.01 ± 3.26 months). This was higher than the age of diaper dermatitis observed by Jordan et al., [2] which was 9–12 months. This difference may be due to our inclusion of perianal inflammation rather than all cases of diaper dermatitis and inclusion of recurrent rather than nonrecurrent ones.

In our study, slight male preponderance was found (52.38%). This was similar to Kränke et al. [4] who reported a male preponderance of 57.1%.

Age at onset of first episode of dermatitis ranged between 4 and 20 months (a mean of 11.2 ± 3.7 months). Number of recurrences ranged between 2 and 6 (a mean of 3.6 ± 1.3 attacks). Duration of the last attack ranged between 12 and 30 days (a mean of 20.1 ± 3.5 days). The duration of dermatitis from first diagnosis till time of definitive diagnosis ranged between 3–7 months (a mean of 3.92 ± 2.81 months). This seems lower than that reported by Kränke et al. [4] who found that half of the patients (51.6%) had complaints for more than 12 months.

From the clinical point of view, vomiting, abdominal distension and atopic diseases were more commonly encountered in the group of cow's milk allergy (83.3%, 70%, and 76.7%, resp.) compared to other patients (24.24%, 18.18%, and 6%, resp.). They can be considered clinical predictors of the possibility of cow's milk allergy.

The higher frequency of atopic diseases in CMA group can be supported by finding of Isolauri et al. [35] that a history of atopy is more common in children with cow's milk protein allergy. Yet, in another study by Doganci and Cengizlier [26], only 2% of children with CMA had atopic diseases. This difference can be explained by difference in pathogenic basis of CMA disease in different population. Doganci and Cengizlier included constipation only. This may be related to the nature of the disease whether it was IgE or non-IgE mediated.

No significant difference was found between children with CMA and other causes as regards family history of atopy (P = 0.9801). Matching with this result, Doganci and Cengizlier [26] found that none of children with CMA had history of familial atopic diseases. On the contrary, Iacono et al. [27] demonstrated a higher frequency of family histories of atopy among patients with cow's milk allergy related chronic constipation. These discrepant results may reflect either a nonunified way of diagnosis of cow's milk allergy or difference in rate of consanguinity in various countries.

Diarrhea and constipation were not different between both groups (P > 0.05). Perianal ulceration and anal fissuring were more commonly encountered with cow's milk allergy group (P < 0.05).

A common cause in our study was lactose intolerance. Radlović et al. [25] found that strict diet eliminating gluten as well as contemporary elimination of lactose for only 2-3 weeks in the patient's nutrition helped to improve the perianal erythema noticed in patients with gluten sensitive enteropathy.

In the present work, small bowel bacterial overgrowth was associated with perianal bacterial dermatitis. We cannot set an answer whether the problem was only bacterial infection from the start or initiated a state of lactose intolerance that triggered the dermatitis. Zhao et al. [36] concluded that small intestinal bacterial overgrowth increases the likelihood of lactose intolerance.

On multiregression analysis it was found that recurrent vomiting, other atopic manifestations, anal fissures, perianal ulcers as well as presence of blood and/or mucus in stool are the most important predictors of underlying cow's milk allergy as a cause of recurrent perianal dermatitis. The age of presentation was not a significant determinant of cow's milk allergy as other etiologies of the current problem are common below 1 year age similar to cow's milk allergy.

The age of presentation was not a significant determinant of cow's milk allergy as other etiologies of the current problem are common below 1 year age similar to cow's milk allergy.

We can conclude that recurrent perianal dermatitis is a multifactorial problem with cow's milk allergy being the most common cause. Recurrent vomiting, other atopic features, fissures and ulcers as well as presence of mucus or blood in stool are significant predictors of this etiology in such a clinical context.

Authors have no conflict of interests with any of the authorities or companies related to the current topic.

1. Hayden GF. Skin diseases encountered in a pediatric clinic. A one-year prospective study. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1985;139(1):36–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Jordan WE, Lawson KD, Berg RW, Franxman JJ, Marrer AM. Diaper dermatitis: frequency and severity among a general infant population. Pediatric Dermatology. 1986;3(3):198–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Amren DP, Anderson AS, Wannamaker LW. Perianal cellulitis associated with group A streptococci. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1966;112(6):546–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Kränke B, Trummer M, Brabek E, Komericki P, Turek TD, Aberer W. Etiologic and causative factors in perianal dermatitis: results of a prospective study in 126 patients. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 2006;118(3-4):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Ward DB, Fleischer AB, Jr., Feldman SR, Krowchuk DP. Characterization of diaper dermatitis in the United States. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154(9):943–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Lane AT, Rehder PA, Helm K. Evaluations of diapers containing absorbent gelling material with conventional disposable diapers in newborn infants. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1990;144(3):315–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Philipp R, Hughes A, Golding J. Getting to the bottom of nappy rash. ALSPAC Survey Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. The British Journal of General Practice. 1997;47:493–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Getting to the bottom of nappy rash. ALSPAC Survey Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. The British Journal of General Practice. 1997;47:493–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Visscher MO, Chatterjee R, Munson KA, Bare DE, Hoath SB. Development of diaper rash in the newborn. Pediatric Dermatology. 2000;17(1):52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Goldsmith PC, Rycroft RJG, White IR, Ridley CM, Neill SM, Mcfadden JP. Contact sensitivity in women with anogenital dermatoses. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;36(3):174–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Bauer A, Geier J, Elsner P. Allergic contact dermatitis in patients with anogenital complaints. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2000;45(8):649–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Wilkinson JD, Hambly EM, Wilkinson DS. Comparison of patch test results in two adjacent areas of England. II. Medicaments. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1980;60(3):245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Shin HT. Diaper dermatitis that does not quit. Dermatologic Therapy. 2005;18(2):124–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Pratt AG, Read WT., Jr. Influence of type of feeding on pH of stool, pH of skin, and incidence of perianal dermatitis in the newborn infant. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1955;46(5):539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Høst A. Frequency of cow’s milk allergy in childhood. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2002;89(6, supplement 1):33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Wright JE, Butt HL. Perianal infection with β haemolytic streptococcus. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1994;70(2):145–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Hyams J, Colletti R, Faure C, Gabriel-Martinez E, Verna M. Functional gastrointestinal disorders. Working group report of the first World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2002;35(supplement 2):S110–S117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2002;35(supplement 2):S110–S117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Gishan FK. Chronic diarrhea. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th edition. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: WB Saunders; 2004. pp. 1276–1281. [Google Scholar]

18. Ahlstedt S, Holmquist I, Kober A, Perborn H. Accuracy of specific IgE antibody assays for diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2002;89(6, supplement 1):21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Taylor SL, Hefle SL, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Factors affecting the determination of threshold doses for allergenic foods: how much is too much? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2002;109(1):24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Zeiger RS, Heller S, Mellon MH, et al. Effect of combined maternal and infant food-allergen avoidance on development of atopy in early infancy: a randomized study. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1989;84(1):72–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Dixon PN, Warin RP, English MP. Role of Candida albicans infection in napkin rashes. British Medical Journal. 1969;2(648):23–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Taschdjian CL, Burchall JJ, Kozinn PJ. Rapid identification of Candida albicans by filamentation on serum and serum substitutes. A.M.A. Journal of Diseases of Children. 1960;99:212–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Ghoshal UC, Ghoshal U, Das K, Misra A. Utility of hydrogen breath tests in diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in malabsorption syndrome, and its relationship with orocecal transit time. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;25(1):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Heyman MB, Committee on Nutrition Lactose intolerance in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):1279–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Radlović N, Mladenović M, Leković Z. Lactose intolerance in infants with gluten-sensitive enteropathy: frequency and clinical characteristics. Srpski Arhiv Za Celokupno Lekarstvo. 2009;137(1-2):33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Srpski Arhiv Za Celokupno Lekarstvo. 2009;137(1-2):33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Doganci T, Cengizlier R. Role of cow’s milk allergy in children with chronic constipation. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;16:8–12. [Google Scholar]

27. Iacono G, Cavataio F, Montalto G, et al. Intolerance of cow’s milk and chronic constipation in children. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(16):1100–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Berg RW, Buckingham KW, Stewart RL. Etiologic factors in diaper dermatitis: the role of urine. Pediatric Dermatology. 1986;3(2):102–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Ferrazzini G, Kaiser RR, Hirsig Cheng SK, et al. Microbiological aspects of diaper dermatitis. Dermatology. 2003;206(2):136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Honig PJ, Gribetz B, Leyden JJ, McGinley KJ, Burke LA. Amoxicillin and diaper dermatitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1988;19(2):275–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Singalavanija S, Frieden IJ. Diaper dermatitis. Pediatrics in Review. 1995;16(4):142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Rasmussen JE. Classification of diaper dermatitis: an overview. Pediatrician. 1987;14(supplement 1):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Paller AS. Immunodeficiency syndromes. In: Harper J, Oranje A, Prose N, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 2000. pp. 1678–1699. [Google Scholar]

34. Mostafa WZ, Arnaout HH, El-Lawindi MI, Zein El-Abidin YM. An epidemiologic study of perianal dermatitis among children in Egypt. Pediatric Dermatology. 1997;14(5):351–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Isolauri E, Tahvanainen A, Peltola T, Arvola T. Breast-feeding of allergic infants. Journal of Pediatrics. 1999;134(1):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Zhao J, Fox M, Cong Y, et al. Lactose intolerance in patients with chronic functional diarrhoea: the role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2010;31(8):892–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2010;31(8):892–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

What's Behind Your Baby's Diaper Rash? – Cleveland Clinic

If you have a baby, you know about unpleasant occurrence of diaper rash. While it’s a common problem, even a mild case can upset you — and irritate your little one.

When you’re changing a diaper and find a red, painful-looking bottom, it’s not only important to know how to treat it, but also how to avoid recurrence. Often, this involves basic care adjustments, but sometimes, it can be harder to pinpoint the source of the problem, especially if it’s related to food or skin allergies.

Pediatrician Jacqueline Kaari, DO, explains what to watch for, how to avoid making diaper rash worse and when you should suspect that allergies are involved.

Deciphering the diaper rash: first steps

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “more than half of all babies between 4 to 15 months of age will develop diaper rash at least once in a two-month period. ” So you’re not alone if you and your baby are occasionally struggling with an outbreak.

” So you’re not alone if you and your baby are occasionally struggling with an outbreak.

“It’s a quality-of-life issue for the child who is miserable, and for the parents who want to help but are not getting any sleep,” Dr. Kaari says.

She says to first look for the most common cause of diaper rash, which is a baby wearing a wet or soiled diaper for too long. It’s important to pay attention to a few diapering basics before looking for other causes.

Basic care tips for your baby’s diaper rash

Research suggests that diaper rash is less common with disposable diapers, but what’s more important than the type of diaper is how often you change it.

Before you consider allergies as a culprit, check to see if you are doing the following:

Advertising Policy

- Change your baby’s wet or soiled diaper as soon as possible. “That’s the best strategy to prevent diaper rash,” Dr. Kaari says. Be especially vigilant if your child has diarrhea or is taking an antibiotic (or if you’re a nursing mother taking an antibiotic).

Antibiotics can cause loose stools and extra irritation.

Antibiotics can cause loose stools and extra irritation. - Apply a protective ointment or cream. Look for products containing zinc oxide or petroleum jelly to use and apply when changing a diaper.

- Let your baby go without a diaper at home whenever possible. This exposes their bottom to fresh air.

Watch for allergies and other factors

Besides the most obvious, there are several other factors that may leave your baby with a red bottom:

1. Disagreeable diapers or wipes. A certain brand of disposable diaper or baby wipe could irritate the skin.

Tip: “While they may outgrow the irritant, the best thing is to try a different product,” Dr. Kaari says. “The simplest strategy is trial and error — eliminate one variable at a time.” Use water wipes or a soft cloth with water to clean their bottom. If your baby’s bottom is red, try to avoid using regular baby wipes to clean the area. These may cause further irritation.

2. Irritating detergent. The laundry detergent used to wash cloth diapers is sometimes the culprit, but if this is the case, your child is also likely to have a rash elsewhere on the body.

Tip: Use detergents labeled scent/fragrance-free and dye-free to wash your baby’s diapers and clothes. Stick with one brand if you suspect soap is irritating your child’s skin.

3. Harmful heat. Hot, humid weather or overdressing a child for the weather can cause a heat rash in the groin area. However, as with detergent, the rash is likely to also show up elsewhere, particularly on the neck, armpits and elbow creases.

Tip: Of course you want to keep your baby warm enough, but it’s possible to overdo it.

In cold weather, check on your baby and loosen clothing as needed when you’re moving from your car to stores or restaurants and back. In hot weather, a diaper is often enough, but use sunscreen and shade when you’re outside. And bring an outfit for air-conditioned spaces.

And bring an outfit for air-conditioned spaces.

Advertising Policy

4. Unfriendly food. Your child may have a food sensitivity or allergy, but other symptoms besides diaper rash are also likely in this case.

“For instance, a child having an adverse reaction to cow’s milk is likely to also have blood in the stool, hives, swollen lips and/or wheezing,” says Dr. Kaari.

Tip: To prevent food allergies, doctors recommend that children avoid milk before age 1 and eggs before age 2.

Know when to call for help

Despite all your best efforts, a child can still develop a diaper rash, either gradually or suddenly. If that happens, clean the area gently with soap and a soft cloth. Avoid rubbing and always be sure to pat the area completely dry.

Call your pediatrician if the rash:

- Persists for three days or gets worse.

- Is more red-dotted than solid red, indicating a possible yeast infection.

- Contains skin that is breaking down and not intact.

- Is accompanied by a fever.

“If there’s any question in your mind, bring them in to see their pediatrician,” says Dr. Kaari, adding, “I tell my parents that about anything.”

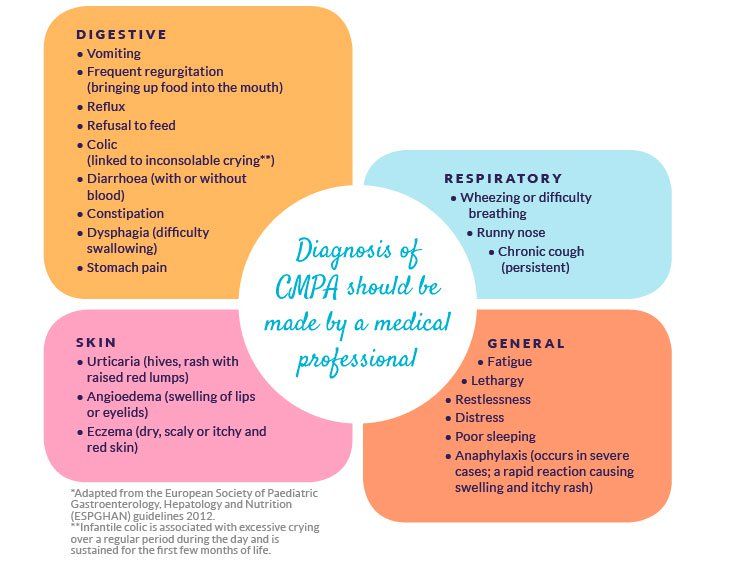

Good to know about MILK ALLERGY (melk)

MILK ALLERGY

Useful information about milk allergy – Information sheet of the Norwegian Asthma and Allergy Association

What is milk allergy?

When allergic to cow's milk protein, a strong reaction of the body's immune system may be the production of antibodies (IgE), or the activation of inflammatory cells. With every meal containing milk proteins, an allergic reaction of the immune system is observed in the form of the production of mediators, such as histamine, or a T-cell inflammatory reaction. Histamine is produced in several places in the body and leads to symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, or skin lesions (urticaria, eczema).

Cow's milk contains over 25 different proteins that can cause a reaction in "milk" allergies. For most people, an allergic reaction can be caused by more than one type of protein. The milk of other artiodactyls such as goat, horse and buffalo contains many of the same proteins. Therefore, allergy sufferers should not consume artiodactyl milk at all.

For most people, an allergic reaction can be caused by more than one type of protein. The milk of other artiodactyls such as goat, horse and buffalo contains many of the same proteins. Therefore, allergy sufferers should not consume artiodactyl milk at all.

If a breastfeeding mother consumes cow's milk herself, some proteins may be transferred with breast milk to the baby's body and lead to negative consequences. Therefore, a breastfeeding mother should follow a dairy-free diet.

Cow's milk allergy is not the same as lactose intolerance. The latter occurs due to the reduced ability of the body to digest milk sugar (lactose). Lactose intolerance leads to stomach pain and diarrhea as a consequence of eating large amounts of dairy products with high levels of lactose (sweet milk, brown (goat) cheese, ice cream and cream).

Symptoms

The symptoms of a milk allergy are very individual. For some, they are minor and harmless, while for others, a severe allergic reaction can occur, even when drinking a small amount of milk. Gastrointestinal tract disorder is common. Not so often there is itching in the mouth and throat, swelling of the mucous membrane and breathing problems, which is especially true for young children. It is also common for them to develop eczema and hives on the skin.

Gastrointestinal tract disorder is common. Not so often there is itching in the mouth and throat, swelling of the mucous membrane and breathing problems, which is especially true for young children. It is also common for them to develop eczema and hives on the skin.

Who is affected?

Milk allergy is the most common type of allergy in young children, which is explained by the early introduction of cow's milk into the diet of infants (eg cereals or mother's milk substitute). About 2-5% of Norwegian babies (0-3 years old) suffer from this type of allergy.

Diagnosis

In order to determine the presence of milk allergy, the doctor must read the patient's medical history, as well as take a blood test for allergic antibodies and a Pirquet test. Not all milk allergy sufferers will show positive results from these tests. This is especially true for infants with symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, or blood in the stool. The only reliable way to find out if milk causes these symptoms is to eliminate milk from the diet for a period of time. When in doubt, reintroduce it back into the diet and see if symptoms return. For children who have not received milk for some time due to allergies, a control test using cow's milk should be performed to ensure that there is no allergic reaction.

When in doubt, reintroduce it back into the diet and see if symptoms return. For children who have not received milk for some time due to allergies, a control test using cow's milk should be performed to ensure that there is no allergic reaction.

Predictions

Generally, cow's milk allergy has a fairly good prognosis. Most of the children get rid of it before reaching school age. Babies who have had negative test results are often allowed to resume milk intake after half a year or a year. It is not known how many adults suffer from milk allergy, but it is estimated that this number does not exceed one percent of the population.

Where is milk protein found?

Milk is found in many processed and prepared industrial foods. Therefore, when buying a product, it is important to familiarize yourself with the list of substances contained in it. The goods declaration must list all ingredients containing milk. A certain group of words used in such lists indicates the content of milk protein in the product: butter, yogurt, yogurt powder.

Cocoa butter, lactic acids and group E substances do not contain milk protein.

Diet

Milk is an important source of nutrients in the Norwegian diet. 25% of the protein given to children, 70% of the iodine and about 70% of the calcium are obtained from dairy products. That is why, in cases of exclusion of dairy products from the diet, these products should be replaced with others that will provide the intake of the above nutrients. Alternatively, specially formulated additives can be used.

What can replace milk?

- Drinks: For small children, a hypoallergenic milk substitute is recommended, available from a pharmacy. These products can be purchased at a pharmacy or obtained from a blue prescription (prescription prescription). Because older children can be difficult to accustom to these milk substitutes due to their taste, it is recommended to start using substitutes as early as possible, for example during breastfeeding. Youth and adults can consume milk substitutes such as rice milk, oat milk, etc. The amount of calcium contained in these products corresponds to the calcium content in cow's milk, however, these drinks often contain less protein and nutrients.

Youth and adults can consume milk substitutes such as rice milk, oat milk, etc. The amount of calcium contained in these products corresponds to the calcium content in cow's milk, however, these drinks often contain less protein and nutrients.

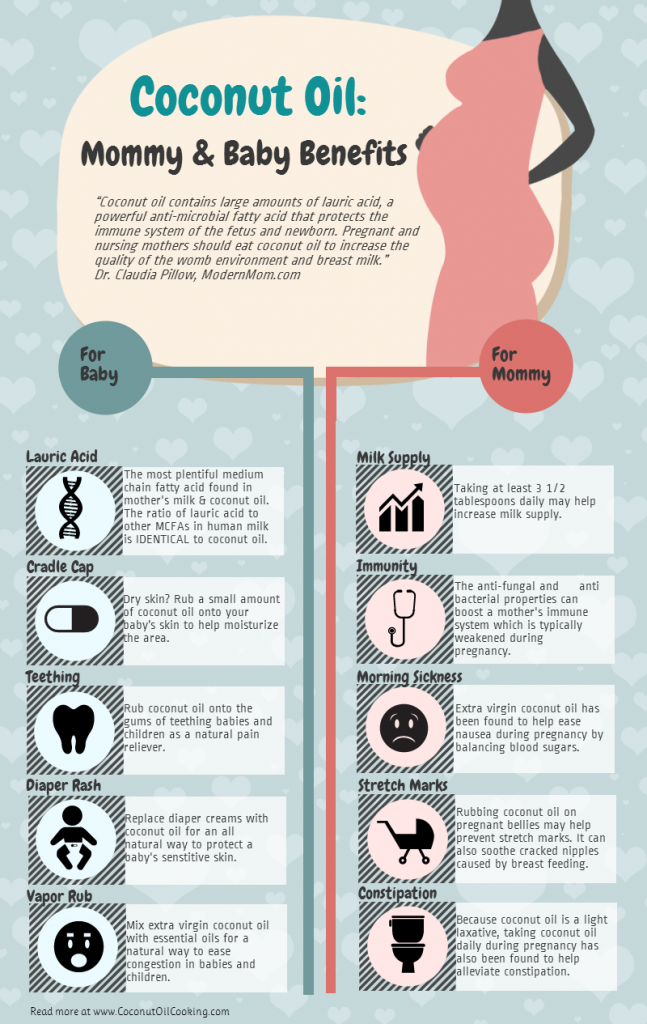

- Cooking: Pharmaceutical-purchased milk substitutes can be used in most meals. Depending on what you are cooking, you can use soy, rice or coconut milk.

- Other substitutes: The following products are available in a dairy-free version - margarine, sour cream, yogurt, ice cream and cream substitutes based on soy, rice or oats.

Food allergy. Doctor's advice. | Ministry of Health of the Chuvash Republic

The New Year is coming soon, the most favorite holiday for children and adults. New Year is fun round dances, delicious gifts. But, unfortunately, often, our adults, carried away by the feast, leave the children unattended, and then the holiday turns into a nightmare.

Traditionally on holidays the number of patients with signs of food allergy and food intolerance (urticaria, Quincke's edema, allergic dermatitis) and with exacerbation of bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis increases.

1. What is food allergy.

Food allergy is an increased sensitivity of the body to food products, which develops when the immune system is disturbed.

Most often, allergies are observed in children, adults usually suffer from it since childhood.

Among people with diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, biliary tract, the prevalence of food allergy is wider than among people who do not suffer from this pathology, and ranges from 5 to 50%.

Food allergy is also common in patients with other allergic diseases, in particular hay fever.

Food allergy must be distinguished from another very similar condition, food intolerance.

2. What is the difference between "food allergy" and "food intolerance"?

With food intolerance, unlike food allergies, there are no changes in the immune system, and the causes of the development of intolerance reactions are often associated with the presence of various concomitant diseases in a person, for example, the stomach, intestines, liver, nervous and endocrine systems.

In addition, food allergies persist throughout a person's life, and food intolerance may disappear after the causes that caused it are eliminated.

3. What are the symptoms of a food allergy?

The most common clinical manifestations of food allergy with a primary lesion of the gastrointestinal tract include: vomiting, colic with lack of appetite, refusal to eat, constipation, loose stools, itching in the mouth or throat.

Skin manifestations of food allergies, or allergic dermatoses, are among the most common in both adults and children. In children under 1 year old, one of the first signs of a food allergy can be diaper rash, symptoms of skin irritation, itching that occur after feeding.

Respiratory manifestations of food allergy (allergic rhinitis, laryngitis). Allergic rhinitis with food allergies is characterized by the appearance of profuse, mucous discharge from the nose, sometimes congestion, sneezing, itching of the skin around the nose or in the nose.

Changes in the nervous system in food allergies are headache, migraine.

4. Which foods are more likely to cause food allergies?

Food allergies can develop after taking almost any food product, however, there are foods that have pronounced allergenic properties and have special allergenic activity:

- fish, especially marine

- seafood (oysters, crustaceans, mollusks, etc.) e.)

- nuts (peanuts, hazelnuts)

- eggs

- milk

- stone fruits (apricots, red varieties of apples, etc.) etc.)

Food intolerance develops most often when eating foods rich in biologically active substances (histamine, tyramine). This is after eating cheese, wine, sauerkraut, spinach, tomatoes, ham, sausages, canned foods, smoked meats, marinades, avocados. Often the cause of the development of food intolerance is not the product itself, but various chemical additives (dyes, flavors, antioxidants, emulsifiers, enzymes)

If you do not know exactly (the culprit of the allergy), it is recommended to follow a general hypoallergenic diet during the holidays.

General non-specific hypoallergenic diet.

Recommended to be excluded from the diet

- Citrus fruits (oranges, tangerines, lemons, grapefruits, etc.)

- Nuts (hazelnuts, almonds, peanuts, etc.).

- Fish and fish products (fresh and salted fish, fish broths, canned fish, caviar, etc.).

- Poultry (goose, duck, turkey, chicken, etc.) and products from them.

- Chocolate and chocolate products.

- Coffee.

- Smoked products.

- Vinegar, mustard, mayonnaise and other spices.

- Horseradish, radish, radish.

- Tomatoes, eggplants.

- Mushrooms.

- Eggs.

- Fresh milk.

- Strawberry, strawberry, melon, pineapple.

- Sweet pastry.

- Honey.

- It is strictly forbidden to consume all alcoholic beverages.

You can eat

- Lean boiled beef meat.

- Soups: cereal, vegetable:

- Secondary beef broth

- Vegetarian

- Butter, olive, sunflower.

- Boiled potatoes.

- Porridge: buckwheat, oatmeal, rice.

- Lactic acid products - one-day (cottage cheese, curdled milk).

- Fresh cucumbers, parsley, dill.

- Baked apples, watermelon.

- Tea, sugar.

- Compotes from apples, plums, currants, cherries, dried fruits.

5. How parents can help with food allergy symptoms.

1. Elimination (removal) of the food allergen suspected of causing the reaction.

2. Enterosorbents (activated carbon, smecta, polyphepan, enterosgel, lactofiltrum)

3. Cleansing enema.

4. Antihistamines.

5. In case of worsening symptoms, consult a pediatrician.

6. Practical advice.

To make the New Year the most favorite holiday, carefully read the labels on imported and domestic food products containing basic information about the quantitative and qualitative composition.