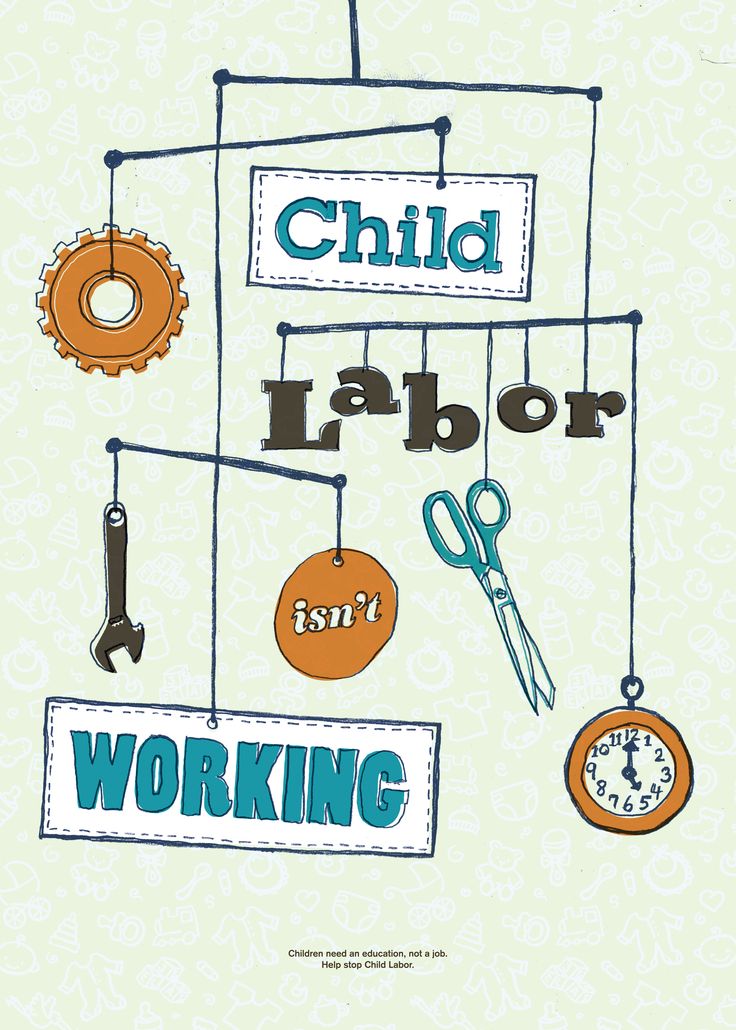

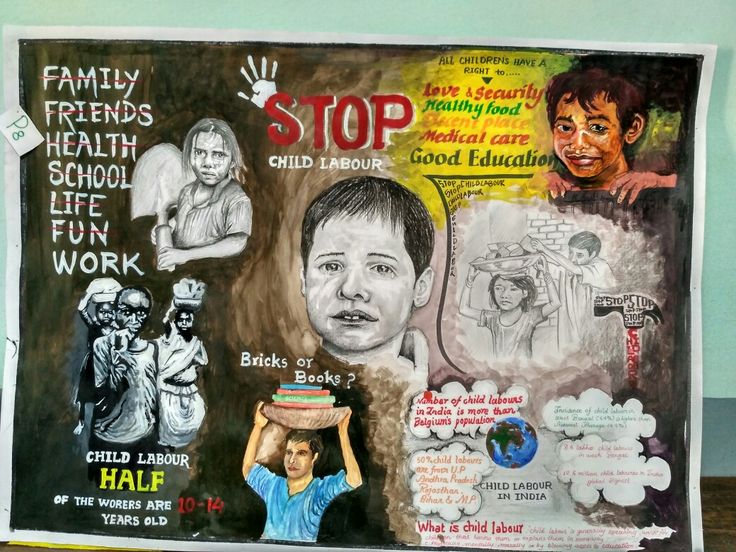

How can we help prevent child labour

Ending Child Labor | The University of Iowa Labor Center

Unions and grassroots groups are increasingly recognizing direct connections between worker rights and the fight against child labor. Recognizing child labor as a violation of children's and workers' rights, trade unions are joining with families and community organizations to combat child labor, to move children out of work and into school, and to support core labor standards. Historically and in today’s global economy:

- strong unions are an important protection against child labor

- when parents are able to improve conditions through effective unions, children are much less likely to have to work

- active struggles against child labor tend to strengthen unions and workers’ rights in general

Many workers and unions in the U.S. and other countries are supporting efforts to end child labor by forging alliances with unions in other countries. These alliances work to achieve enforceable global labor standards, such as ILO Convention 182, and hold transnational companies accountable for labor practices.

History’s Strategies Still Apply:

- Union and Community Organizing

- Free Education for All Children

- Campaigns to Change Public Opinion

- Universal Minimum Standards

Examples of Effective Child Labor Solidarity

Global March against Child Labor

Supporting workers’ struggles to organize unions and reject child labor

In 2001 factory monitors confirmed illegal union-busting and other violations—including employment of 13-15 year-old children—at a Mexican factory sewing clothing with university logos for Nike and other U.S. companies. Thousands of American students, workers, and consumers wrote letters to corporate CEOs protesting worker treatment. The international solidarity campaign helped factory workers overcome violence, intimidation, and mass firings when they tried to organize, and after months of struggle, workers won an independent union.

In 2002, as news of child labor abuses and attacks on workers in Ecuador’s banana plantations spread around the world, workers, consumers, and students contacted Los Alamos plantation owner Alvaro Noboa to demand that he recognize the workers’ union and cease using illegal child labor. Presidents of the AFL-CIO, the International Union of Food and Allied Workers (IUF), the Teamsters, and many other labor leaders also issued letters in support of Los Alamos workers’ struggle.

Presidents of the AFL-CIO, the International Union of Food and Allied Workers (IUF), the Teamsters, and many other labor leaders also issued letters in support of Los Alamos workers’ struggle.

Campaigning for institutions to adopt and enforce codes of conduct

When the 2000 Olympics were held in Sydney, Australia, Australian labor federations created and signed an agreement with the Olympic organizing committee requiring all sponsors and licensees to adhere to minimum labor standards, including international conventions on child labor.

Pressure from human rights groups, consumers, and international trade unions led the group overseeing the World Cup (FIFA—Federation Internationale de Football Association) to adopt a Code in 1998 stating it would cease using soccer balls made with child labor. This year, when reports indicated that children were still working in the soccer ball industry and that adult workers were not being paid a living wage, activists launched a new publicity and letter-writing campaign, mobilizing soccer fans, consumers, and politicians to demand FIFA improve factory monitoring and live up to the promises in its Code.

Implementing and supporting fair trade or labeling initiatives

Through programs developed by non-profit organizations, export goods like coffee or cocoa can now be certified as “Fair Trade” products if producers adhere to basic labor standards—including ILO conventions on child labor—and pay farmers fair prices so families can meet basic living needs without having children work for wages. Groups like TransFair USA and others help to publicize Fair Trade initiatives and educate consumers about Fair Trade products.

When the use of child labor in the rug-making industries of Pakistan and India gained international publicity in the 1990s, consumer groups—building on the history of effective “union label” initiatives—worked with manufacturers to begin phasing out the use of child labor and licensing companies to use “no child labor” labels if production facilities were regularly inspected by independent monitors. The resulting “RUGMARK” label program, now known as "GOODWEAVE", uses licensing fees to fund monitoring programs and education and rehabilitation for children removed from carpet jobs. Consumer groups and unions play a role in educating the public about the label program and ensuring it maintains strict standards for licensed companies.

Consumer groups and unions play a role in educating the public about the label program and ensuring it maintains strict standards for licensed companies.

Using collective bargaining strategies

The International Federation of Chemical, Energy, Mine and General Workers’ Unions (ICEM) signed in 2000 and recently renewed a “global agreement” with the multinational Freudenberg corporation, which owns chemical and rubber manufacturing plants all over the world. Freudenberg is headquartered in Germany/Japan, but the agreement covers all Freudenberg workers in the U.S. and 40 other countries. Among other recognitions of workers’ rights, the agreement commits Freudenberg to a ban on “child labour according to the definitions included in ILO Convention 138.”

Promoting global labor standards in trade agreements

The International Confederation of Free Trade Unions continues to propose adding a “social clause” covering seven core labor standards, including prohibitions on child labor, to WTO rules governing international trade; this proposal has so far been rejected by WTO leaders.

Garment Workers at a Union Solidarity Center Meeting

Cambodia

Trade agreements between the U.S. and Cambodia have successfully included incentives for garment manufacturers to improve factory working conditions. Agreements require factory owners to respect core labor standards, including eliminating child labor and respecting workers’ rights to organize unions and collectively bargain.

Filing suit against corporations for labor rights abuses abroad

The International Labor Rights Fund and other groups have begun pursuing legal action against companies for alleged labor abuses in other countries. In 1996, for example, ILRF filed a suit against Unocal for using slave labor to build pipelines in Burma; and with the support of U.S. labor unions, ILRF recently filed a suit against Coca-Cola for using paramilitary forces to suppress organizing and assassinate union leaders in Colombia (these suits are still pending). If effective, this strategy could be used in the future to hold transnational corporations accountable for child labor abuses.

Promoting access to education

Increasing children’s access to public education is a fundamental strategy for ending child labor. An example of promoting access to education is the Bangladesh Building and Woodworkers’ Federation and the Metal Workers’ Union that seeks to remove children from hazardous workplaces and enroll children in education and assistance programs. On a larger scale, the Global Campaign for Education is a coalition involving teachers’ unions, Global March Against Child Labor, Oxfam, and Action Aid.

Educational materials containing more information on Ending Child Labor are available through this web site:

- Workshop Materials—Core Workshop on Child Labor

- Workshop Materials—Health and Child Labor

- Workshop Materials—International Trade and Child Labor

- Workshop Materials—International Workers’ Rights and Child Labor

- K-12 Teachers’ Materials

These materials include Power Point presentations, instructors’ manuals, activities, and handouts. You may adapt these materials to your group’s needs.

You may adapt these materials to your group’s needs.

10 Tips for Helping End Child Labor

by Marsha Rakestraw

Last updated January 31, 2019.“The change starts within each one of us, and ends only when all children are free to be children.” – Craig Kielburger

Have you recently purchased a soccer ball?

Something embroidered? Something made from cotton? Chocolate? Clothes? Produce?

If so, there’s a good chance you’ve purchased something made from child labor. Child labor and slavery are so entrenched in the production of goods and services from so many countries, that it can be an enormous challenge to avoid it.

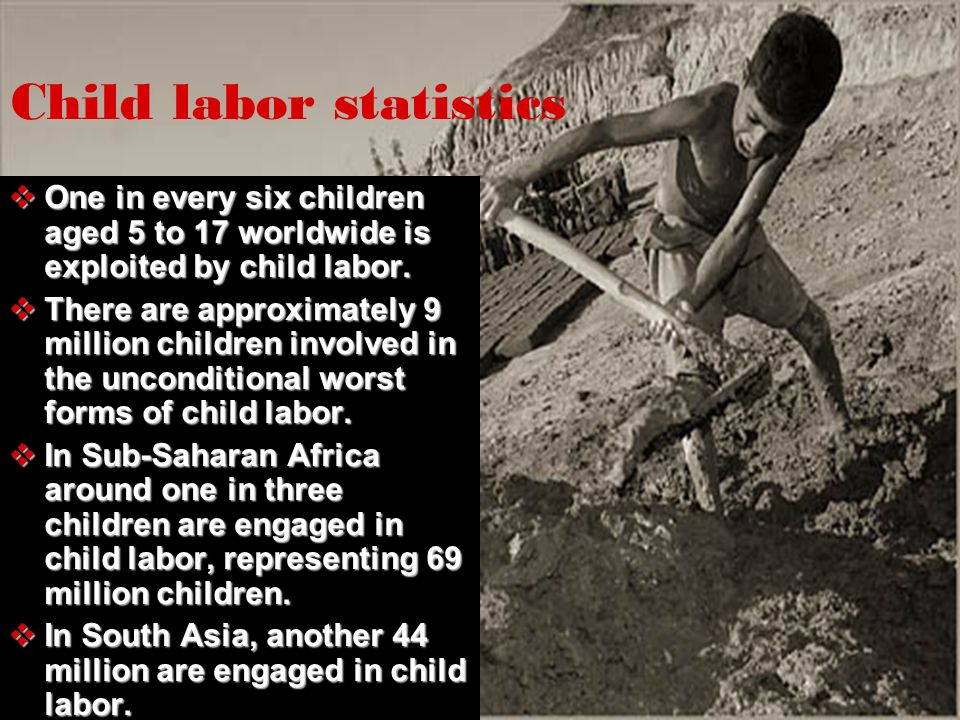

It’s estimated that more than 200 million children around the world are engaged in child labor, and more than half of those (ages 5-17) are involved in some sort of hazardous or dangerous work.

Child labor has existed in some form for thousands of years.

But, as our population has grown, as poverty has risen, as economic globalization has spread, the exploitation, oppression and violation of children has increased. As the editors of Child Labor: A Global Perspective mention, “Poverty is the major precipitating factor, but education, rigid social and cultural roles, economic greed, family size, geography, and global economics all contribute.”

As the editors of Child Labor: A Global Perspective mention, “Poverty is the major precipitating factor, but education, rigid social and cultural roles, economic greed, family size, geography, and global economics all contribute.”

Part of the issue is that there is no clear, global definition of child labor.

Is it all work that a child does? Only work that is oppressive or exploitative? Does working with your family count? How young is too young to work?

One book, Living as a Child Laborer, made this distinction:

Child Work is “work that does not interfere in any way with the development of children or their education.”

Child Labor is “work that is mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful to children or interferes with their education. It is work, therefore, that deprives children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity.”

The International Labor Organization defines child labor as work that:

- is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children; and interferes with their schooling by:

- depriving them of the opportunity to attend school;

- obliging them to leave school prematurely; or

- requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.

As the ILO says:

“In its most extreme forms, child labour involves children being enslaved, separated from their families, exposed to serious hazards and illnesses and/or left to fend for themselves on the streets of large cities – often at a very early age. Whether or not particular forms of ‘work’ can be called ‘child labour’ depends on the child’s age, the type and hours of work performed, the conditions under which it is performed and the objectives pursued by individual countries.”

Some people also argue that definitions of “child” and “labor” often have developed from a Western perspective that doesn’t reflect the views of other cultures.

Regardless of the blurriness of definitions, most countries have some laws that limit the amount and types of work children can do. But, that doesn’t mean that they are acknowledged or enforced.

What kind of “work” are children engaged in that could be considered child labor?

Weaving rugs, making bricks, farming, taking apart toxic electronics, selling, cooking, diving for fish, or serving as child prostitutes, domestic workers, child soldiers, etc. There’s no end to the list.

There’s no end to the list.

World Day Against Child Labor is observed each year on June 12.

Here are a few tips for helping end child labor:

- Educate yourself.

Use resources such as those suggested here, and then share what you learn with friends, family, co-workers, and others, and work together to increase your “voting” power. - Contact retail stores, manufacturers, and importers.

Kindly ask them questions about the origins of their products. Let them know you want to buy products that don’t involve child labor, and give them suggestions for ethical products and services they can offer instead. - Buy fair trade and sweatshop-free products whenever possible.

Buy used when you can’t. Or borrow, share, trade, make it yourself, etc. Look for certified fair trade labels such as Fair Trade Certified, Fairtrade America, and the Goodweave label to ensure that you’re supporting positive practices that don’t involve child labor.

Also be sure to use Food Empowerment Project’s Chocolate List to ensure that the chocolate you’re purchasing wasn’t made using child labor. - Grow more of your own food.

Buy from farmer’s markets (verify their labor practices first), Community Supported Agriculture, and U-Pick farms. - Share your time and money.

Forgo that daily latte or expensive make-up or go out to eat a bit less, and funnel that money toward supporting reputable groups that are helping free children from exploitative labor and helping them get a good education. Volunteer your time when you can. - Contact local, regional, and national legislators.

Ask them to pass laws that ensure no products in your city/state/country are made with child labor, and encourage them to adopt “codes of conduct” which include concern for humane, sustainable, just practices. - Contact businesses that do business in countries that have child labor.

Encourage them to put pressure on government officials to take appropriate action and on businesses that use child labor to use sustainable, fair-trade practices. - Invest ethically.

If you’re a shareholder, use your voice to ensure that your companies support humane, sustainable, just practices that don’t include child labor. - Contact government leaders.

Write letters to the heads of countries that permit any form of child slavery/forced labor and ask them to strengthen and enforce their laws, and to increase educational opportunities for children and humane, sustainable business opportunities for adults. - Educate others.

Give presentations to schools, communities of faith, nonprofits, and other groups to educate them about child labor issues and encourage positive action.

Stopping such insidious practices isn’t easy, but there are choices that all of us can make to improve conditions for children, to reduce our contribution to child labor, and to facilitate an end to the oppression and exploitation of children.

Image via ILO/Phan Hien/Flickr.

We would love to hear from you. Let us know what you think about our content by leaving us a comment or by emailing us at [email protected].

Save

How to prevent the exploitation of children in conflict? |

Archive audio

Download

Millions of children around the world are forced to work - often in very difficult and unsafe conditions. On June 12 - World Day against Child Labor - remind the UN. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has released new guidance on preventing the exploitation of children in times of crisis. Learn more about what amounts to exploitation and how to help children remain children, even in situations of armed conflict, with FAO Representative Jacqueline Demeranville.

*****

“Exploitation of child labor is work that poses a threat to the health, safety, morale of the child, as well as work that does not allow the child to receive an education. It is also the involvement of children under a certain age in the work.

In short, from the point of view of international law and the legislation of most countries, a teenager who sprays pesticides, or a child who cannot go to school because he has to work, are victims of exploitation. At the same time, says FAO's Jacqueline Demeranville, in certain cases, the involvement of children in labor is acceptable.

“Working in a safe environment, work that does not interfere with the child's education and is appropriate for the child's age may be considered legitimate. In rural areas, working "on the ground" can be beneficial for children. It helps them acquire the skills they will need in the future.”

However, working conditions in the fields rarely meet these acceptance criteria. Sometimes children are forced to do very hard work, replacing adults. Most often, children living in a conflict zone or caught in the epicenter of a natural disaster find themselves in such a situation.

Sometimes children are forced to do very hard work, replacing adults. Most often, children living in a conflict zone or caught in the epicenter of a natural disaster find themselves in such a situation.

“Natural disasters and armed conflicts destroy the habitual life of people, destroy their property, for example, livestock. In such conditions, children stop going to school, because they have to help their families survive, earn money, get food. Some children lose loved ones during war or natural disasters. They have to work so as not to die of hunger.”

Children who were exploited before the outbreak of conflict face new threats to life and health in the context of hostilities. They may come under fire in open areas, or run into mines and unexploded ordnance while working in the field.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reminds that child labor is just one of the many problems people face in armed conflict. FAO's new leadership should help affected communities cope with the impact of the crisis and prevent the emergence of a "lost generation".

“Social institutions that protect children's rights and educational institutions play a very important role in times of conflict. But it is also important that various agricultural organizations and programs do their best to protect children from exploitation. They should help families to quickly restore the economy and return to normal life. Thanks to programs to support farmers and develop agriculture, children will be able not to overwork and go to school.”

Photo Credit

Photo Credit

ILO Photo

itunes

Children

Interviews

Human Rights

Reports

reviewme-pro

me-audio-audio

Child labor for survival - News of Uzbekistan - Gazeta.uz

It is not the first year in the center of Tashkent that children have been selling wet wipes to restaurant and cafe visitors and passers-by. Not only teenagers are involved in the work. Many of them have not yet reached school age. Gazeta.uz, using the example of one family, tried to figure out why children are forced to work, what their parents do, and what measures are being taken by the authorities to prevent child labor.

Gazeta.uz, using the example of one family, tried to figure out why children are forced to work, what their parents do, and what measures are being taken by the authorities to prevent child labor.

Shameful labor

Malika (names of children and their relatives hereinafter changed) 11 years old. She's already used to selling napkins. The girl looks blankly into space through the visitors of the cafe and offers to buy them a pack of wet wipes at a gold price. Seven-year-old Nigora trudges behind Malika. She hardly speaks and does not respond to questions.

While the children are waiting for dessert, I find out that they live in the Sergeli region and need clothes. The girls' mother sits around the corner of the cafe with their 1.5-year-old younger sister. Their three-year-old brother, a pregnant aunt with a child, grandparents are waiting for them at home.

Advertisement on Gazeta.uz

Nigora and Malika attend a school near their house. The eldest girl began to study at the age of 8 and has already changed more than one educational institution. Because of work, children do not always get enough sleep and do their homework.

The eldest girl began to study at the age of 8 and has already changed more than one educational institution. Because of work, children do not always get enough sleep and do their homework.

Malika and Nigora go to work three or four times a week with their mother or grandmother. The working day lasts about five hours, and closer to midnight the family returns home.

The girls' mother Saodat shakes bottles of sweet tea for one and a half year old Amalia. The evening sun paints the walls of her new kitchen a golden hue.

Saodat says that after 13 years of struggling to get social housing, her family finally managed to get a two-room apartment in a new neighborhood. Together with Saodat and her children, four more people live in the apartment.

Saodat was about to lose hope. She had to spend the night at the building of the Sergeli hokimiyat for several months. For a young woman, there is no greater happiness than living with children under the same roof.

Previously, out of desperation, Saodat was forced to send her children to a transit center. Usually, children live in the center for no more than a month. From there, they can be assigned to an orphanage or placed under the care of relatives.

Saodat is only 30 years old, she has four children abandoned by her fathers and a water hernia in her stomach. She has been begging since the age of five.

“We used to beg, and then I found out that you can sell napkins. I myself cannot sell, because no one will buy from me, so I have to take older daughters. I hope younger children don’t have to live like this anymore,” she says.

Heavy physical activity is contraindicated for Saodat, so she cannot get a low-skilled job as a cleaner or janitor. She didn't go to school, she can't write and only reads by syllables, so she doesn't dream of a better job. Saodat says that she was offered an easy job that would not harm her health, but her family could not survive on a salary of 50,000 soums a day.

“I don't know what we'll do when the cold comes. Now the children don't even have jackets. Probably, we will sit at home and eat whatever we have,” the woman worries.

In one evening, her children manage to earn an average of 200,000 soums ((minus the cost of napkins). The family cannot work more than 15-17 days a month. They have to return from work by taxi. Almost all the earnings go to food. Utilities and accumulated debts for buying used furniture. Furniture had to be bought on credit from neighbors. Saodat's new apartment had nothing but a gas stove and a small refrigerator.

At the mahalla gathering of citizens at the place of residence of Saodat, Gazeta.uz was informed that the labor exchange monthly provides a list of open vacancies, and women are helped to draw up documents for receiving child benefits.

However, according to Saodat, she has not yet received a residence permit in her new apartment, and without a residence permit for state work, she will not be able to get a job, nor will she receive benefits for her children.

Police officers know about the troubles and problems of Saodat and her children. However, according to the woman, while they are limited to moralizing, they shame her and do not offer real ways to cope with the current situation.

“If a child works during class, find out why he sells napkins during class. It turns out whether the situation in the family is really difficult," Gazeta.uz was told in the press service of the Tashkent police department. — There were cases when parents did not know that their children were working. There was a specific case when the mother of the children was ill. Then the Central Internal Affairs Directorate contributed to the allocation of material assistance and a warrant for free treatment.

“Often the fathers of these children live their lives,” added the press service of the Central Internal Affairs Directorate. “Children grow up in dysfunctional families where parents don’t care about their children. In such cases, the parents are subject to measures in accordance with Article 47 of the Administrative Code - failure to fulfill the duties of raising and educating children.

In such cases, the parents are subject to measures in accordance with Article 47 of the Administrative Code - failure to fulfill the duties of raising and educating children.

The police department emphasized that in order to solve the problem, it is necessary to increase the responsibility of parents for raising children and work with them.

Mahalla committees, ministries of labor and public education are involved in the case of children selling napkins, the police department noted.

Invisible problem

State labor inspector of the Ministry of Employment and Labor Relations Gulrukh Niyazmetova could not confirm to Gazeta.uz that the ministry is dealing with child labor issues in this context. She referred to Article 7 of the Labor Code (prohibition of forced labor) and the International Labor Organization (ILO) convention on forced labor and its abolition.

Gulrukh Niyazmetova noted that according to the monitoring of the Ministry of Labor, 7 cases of forced child labor were revealed in 10 months of this year. There are no reports of incidents with inspection napkins.

There are no reports of incidents with inspection napkins.

She advised the Gazeta.uz correspondent to apply to the social department for the care of minors under the Tashkent City Department of Public Education (GUNO). However, the editors could not get through to the number given by the receptionist of the GUNO.

The city interdepartmental commission for work with minors under the khokimiyat of Tashkent told Gazeta.uz that the issues of children selling napkins should be dealt with by the Main Department of Internal Affairs.

Social roots

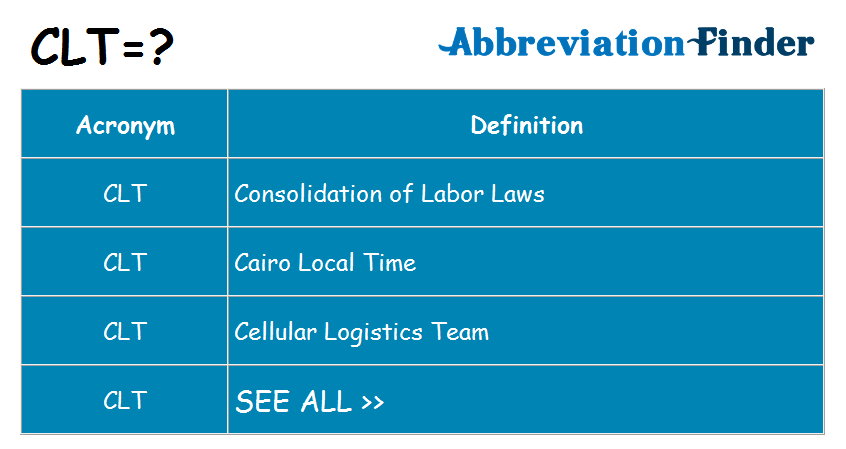

The minimum age for employment established by the Labor Code of Uzbekistan is 15 years. This is in line with international standards, namely the 138th ILO Convention, which Uzbekistan ratified in 2009.

Despite the adopted regulations, the problem of child labor remains unresolved. Without offering families an alternative, eradicating the problem of child labor seems unlikely.

Columbia University expert, social worker with experience in Uzbekistan Ludmila Kim believes that to solve the problems of families in difficult life situations, there should be services and organizations that provide professional assistance.

“A lot of departments are involved in supporting families in the social system of Uzbekistan. These are the ministries of public education, health, labor relations, internal affairs. These are the Women's Committee and the Oila Center. But when one child has ten nannies, it turns out that there is not one,” says Lyudmila Kim.

In her opinion, Saodat is a client of all institutions. However, her unresolved problems are related to the lack of professional social workers, although some work is being done in this direction.

Lyudmila Kim noted that families in difficult situations face a range of problems. These problems are related individually to each family member and to the family as a system. In this case, it is necessary to consider not only the problems of Saodat and her children, but also the relatives of the woman who share housing with her. It is also necessary to consider the environment of the family in the face of the mahalla gathering of citizens, schools and clinics, the society in which the family lives.

In this case, it is necessary to consider not only the problems of Saodat and her children, but also the relatives of the woman who share housing with her. It is also necessary to consider the environment of the family in the face of the mahalla gathering of citizens, schools and clinics, the society in which the family lives.

Saodat is faced with the need to meet the basic needs of his family: food and clothing. And only after satisfying the basic needs, Saodat will be able to move on to solving the problem of treatment, employment, and education of his children, notes Lyudmila Kim.

“Saodat is trying to be with his children. She is a good mom. She is trying to be a good mother, as she knows how, based on her life experience. She sees no other way out. And the labor of children is the survival strategy that she found, ”the expert insists.

Ludmila Kim emphasized that Saodat has many strengths. The woman fought for an apartment for many years and was successful in this. She stays with her children despite being forced to temporarily take them to a transit center.

She stays with her children despite being forced to temporarily take them to a transit center.

“The main model of social work is to identify the strengths of the client. Institutional establishment is the last measure that can be resorted to. And now the main thing is that children do not end up in these institutions. Research and practice show that institutional forms cause irreparable harm to the development of the child, his psycho-emotional health and have very long-term and negative effects in adult life,” said Lyudmila Kim.

She noted that the tasks of a social worker in solving client problems are problem identification and prioritization. The social worker draws up an action plan and helps the family implement it. He acts in an interdisciplinary team of specialists working individually with each case. They find needed services, coordinate the family, monitor outcomes, and intercede for clients. Moreover, the social worker teaches the client how to cope with their own difficulties. His task is not only to solve the problem, but also to prevent difficult life situations in the future.

Moreover, the social worker teaches the client how to cope with their own difficulties. His task is not only to solve the problem, but also to prevent difficult life situations in the future.

“The most important element of social work is the formation of human relations between an employee and a client. Social work is based on global ethical principles and values that underlie the professional code of ethics of social workers. Respect for human dignity and human rights, social justice, acceptance of human value, respect for confidentiality and relationships based on acceptance and empathy are integral elements of the social worker's activities that make this profession unique among other professions, ”the expert emphasized.

Ludmila Kim believes that the Saodat case has a very serious level of complexity, requiring a professional approach using scientific methods based on evidence, practice and research.

The expert noted the professional work of the Republican Center for Social Adaptation of Children (RCSAD) and the SOS-Children's Villages Association, which have programs to prevent the separation of children from families and their placement in institutional institutions.