Losing your baby

Experiencing a pregnancy loss | Pregnancy Birth and Baby

Experiencing a pregnancy loss | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content5-minute read

Listen

It can be devastating to lose a baby at any stage of pregnancy. Even though you probably feel very alone, pregnancy loss is more common than you probably think — and it’s not your fault. This article aims to help you deal with the many emotions you will be feeling.

Experiencing a miscarriage, stillbirth, blighted ovum, molar or ectopic pregnancy can be very traumatic for both parents. Society underestimates how painful it is. Losing a baby is a death that you need to grieve, just as when you lose any other loved one.

Pregnancy loss can happen very quickly, and it can take a while to make sense of what is happening. You will need to mentally adjust to life without the future you expected. You may grieve not just for the baby you’ve lost, but also for your sense of yourself as a parent, and your plans and hopes for the future.

You will likely experience many different emotions and these might last for months or years. Everyone is different and there is no right or wrong way to grieve a lost pregnancy.

Feelings you might have

When you lose a baby, you will experience a wide range of different emotions. You might feel numb at first, or find it hard to believe it’s true. You might go through anger, sadness, confusion and depression. You might also have physical symptoms like trouble sleeping or wanting to sleep all the time, difficulty concentrating, loss of appetite, and crying a lot.

Many women say they feel guilty when they lose a baby, or they feel jealous and bitter. All of these emotions are completely normal. It can help to acknowledge all of your emotions but also to remember that these feelings won’t last for ever.

What’s important is to give yourself time to grieve so you can heal both physically and emotionally.

Finding out why it happened

It’s natural to want answers about why it happened – but the truth is, often no one knows why pregnancy loss happens. You might feel guilty or angry, and replay the events in your head to try to work out whether it was something you did. This is normal. Talking to a health professional can help you work through these feelings. Ask as many questions as you need to.

If you lost the baby when it was fully formed, an autopsy or other tests might be done to try to find the cause of the miscarriage or stillbirth, such as an infection or chromosomal abnormalities. This information can help you in future pregnancies.

Partners grieve too

Partners can be devastated by pregnancy loss too. At the time they might be busy helping you deal with the physical side of the pregnancy loss, and they might suppress their own grief. It might not hit them until much later, such as after another baby is born.

Some men might show their grief as anger. It’s important to understand that you are both grieving in different ways, and to treat each other with respect while you’re recovering.

Dealing with social situations

You will probably find that reminders of your lost baby are everywhere – Mother’s Day, other people’s baby announcements and pictures on social media can all trigger your sadness.

It’s a good idea to be prepared in advance and take the time to look after yourself. You don’t have to go to social functions for a while, especially if you know other people will be there with their babies. Consider going on holiday with your partner over Christmas, or attending family functions for just a short time. It can really help to remove yourself from social media for a while too.

You might find one of the hardest things is dealing with how other people react. They might not realise how painful it’s been for you, or they might not talk about your loss because they think it will upset you. Remember, other people can also find it hard to deal with your pregnancy loss, even health professionals. It can help if you are open and honest about how you are feeling. Be prepared for questions and have standard answers ready.

Remember, other people can also find it hard to deal with your pregnancy loss, even health professionals. It can help if you are open and honest about how you are feeling. Be prepared for questions and have standard answers ready.

Don't forget that children need to grieve and deal with loss too, so if you have other children it’s important to explain to them honestly what happened, and to answer all of their questions openly.

Trying again

Everyone is different and the time it takes to feel better can vary a lot from person to person. Many people feel like they need to try for another baby as soon as possible, but falling pregnant again won’t take away your grief. It may be a good idea to give yourself time to grieve first.

If you fall pregnant again, it’s normal to feel anxious. It’s a good idea to talk your feelings through with your doctor or midwife, especially if you feel like your fears and worries are taking over.

Where to seek help

You can talk to your doctor or midwife about where to get support.

The SANDS Australia website provides support for people who have experienced miscarriage, stillbirth and newborn death. You can call them on 1300 072 637, 24 hours a day.

The Pink Elephants Support Network website provides information and support for people who have experienced a miscarriage.

Please call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby on 1800 882 436 if you would like to discuss pregnancy loss further.

Sources:

Sands Australia (Stillbirth and Newborn Death), COPE Centre of Perinatal Excellence (Coping with pregnancy loss), Pink Elephants Support Network (Sorry for your loss), Raising Children Network (Miscarriage: what it is and how to cope)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: December 2020

Back To Top

Related pages

- Emotional support after miscarriage

Need more information?

Pregnancy: miscarriage & stillbirth | Raising Children Network

Have you experienced a miscarriage or stillbirth? Find articles and videos about coping with the grief of losing a pregnancy or having a stillbirth.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Coping with grief | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

Not-for-profit for bereaved parents from pregnancy loss from miscarriage stillbirth newborn death

Read more on Sands Australia website

Remembering your baby | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

Resources that will help you incorporate your baby's memory into your everyday life.

Read more on Sands Australia website

Planning another pregnancy | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

We know how lonely and isolating pregnancy after loss can feel and how difficult it can be to find your ‘tribe’ who understand what you’re going through.

Read more on Sands Australia website

Miscarriage | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

Helping you understand the complex range of emotions you may experience during fertility treatment or after miscarriage or early pregnancy loss

Read more on Sands Australia website

Fathers Support Services | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

Grief support for men, fathers, grandfathers following pregnancy and infant loss, through miscarriage, stillbirth or newborn death.

Read more on Sands Australia website

Stillbirth and newborn death | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

Support after the death of a baby through stillbirth or newborn death

Read more on Sands Australia website

A Father's Grief | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

No father expects his baby to die, and when the unthinkable does happen, a father's grief can often feel overlooked. This is a very challenging time for you, but you are not alone. There are many sources of support available for dads like you.

This is a very challenging time for you, but you are not alone. There are many sources of support available for dads like you.

Read more on Sands Australia website

A partner's grief | SANDS - MISCARRIAGE STILLBIRTH NEWBORN DEATH SUPPORT

How partners can look after themselves whilst supporting the rest of their family through grief.

Read more on Sands Australia website

Death of a baby - Better Health Channel

Miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death is a shattering event for those expecting a baby, and for their families. Grief, relationship stresses and anxiety about subsequent pregnancies are common in these circumstances.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is provided on behalf of the Department of Health

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework. This website is certified by the Health On The Net (HON) foundation, the standard for trustworthy health information.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Why we need to talk about losing a baby

Why we need to talk about losing a baby- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Home/

- Newsroom/

- Spotlight/

- Why we need to talk about losing a baby

Why we need to talk about losing a baby

WHO/M. Purdie

Purdie

© Credits

Losing a baby in pregnancy through miscarriage or stillbirth is still a taboo subject worldwide, linked to stigma and shame. Many women still do not receive appropriate and respectful care when their baby dies during pregnancy or childbirth. Here, we share your stories from around the globe.

Miscarriage is the most common reason for losing a baby during pregnancy. Estimates vary, although March of Dimes, an organization that works on maternal and child health, indicates a miscarriage rate of 10-15% in women who knew they were pregnant. Pregnancy loss is defined differently around the world, but in general a baby who dies before 28 weeks of pregnancy is referred to as a miscarriage, and babies who die at or after 28 weeks are stillbirths. Every year, nearly 2 million babies are stillborn, and many of these deaths are preventable. However, miscarriages and stillbirths are not systematically recorded, even in developed countries, suggesting that the numbers could be even higher.

Around the world, women have varied access to healthcare services, and hospitals and clinics in many countries are very often under-resourced and understaffed. As varied as the experience of losing a baby may be, around the world, stigma, shame and guilt emerge as common themes. As these first-person accounts show, women who lose their babies are made to feel that should stay silent about their grief, either because miscarriage and stillbirth are still so common, or because they are perceived to be unavoidable.

Jessica Zucker, clinical psychologist and writer, USA

"As a clinical psychologist, I specialise in women's reproductive and maternal mental health and have done so for over a decade. It wasn't until I experienced this 16-week miscarriage first-hand that I could truly grasp the anguish and the circuitousness of grief I had heard my patients speak of for so many years. After my miscarriage, I poured over the research which shows that a majority of women report experiencing feelings of shame, self-blame and guilt following pregnancy loss. "

"

Jessica's story

All of this takes an enormous toll on women. Many women who lose a baby in pregnancy can go on to develop mental health issues that last for months or years– even when they have gone on to have healthy babies.

Cultural and societal attitudes to losing a baby can vary tremendously around the globe. In sub-Saharan Africa, a common belief is that a baby might be stillborn because of witchcraft or evil spirits.

Larai, 44, pharmacist, Nigeria

“Coping with my miscarriage was traumatic. The medical staff contributed a lot to my grief despite the fact that I am a doctor too. The other issue is the cultural attitude. In most traditional African cultures, people think you can lose a baby because of a curse or witchcraft. Here, child loss is surrounded by stigma because some people believe there is something wrong with a woman who has had recurrent losses, that she may have been promiscuous, and so the loss is seen as a punishment from God. "

"

Larai’s story

People, especially those with high profiles, are taking to social media to share their experiences, like in the case of Kimberly Van Der Beek and her husband, actor James Van Der Beek, best known for his role in American television series Dawson’s Creek. The couple recently shared a heartfelt post on Instagram where they opened up about the painful process of suffering multiple miscarriages — and then learning how to move past it.

Kimberly Van Der Beek, USA

"I’ve had three miscarriages, all around 10 weeks gestation. I let them all happen naturally. I had a loving husband, a compassionate birthing team and I felt spiritually grounded about them. And even in the best of circumstances, I was devastated every single time. After one of them I sat in the shower crying for almost five hours. What I find disheartening is that not all women, or fathers for that matter, are treated with the same compassion or have support during this gut wrenching time".

Kimberly's story

There are many reasons why a miscarriage may happen, including fetal abnormalities, the age of the mother, and infections, many of which are preventable such as malaria and syphilis, though pinpointing the exact reason is often challenging.

General advice on preventing miscarriage focuses on eating healthily, exercising, avoiding smoking, drugs and alcohol, limiting caffeine, controlling stress, and being of a healthy weight. This places the emphasis on lifestyle factors, which, in the absence of specific answers, can lead to women feeling guilty that they have caused their miscarriage.

Lisa, 40, marketing manager, UK

“I’ve had four miscarriages. Each time it happens, a piece of you dies. The most traumatic was the first one. We were so excited about our new baby. But when we went in for the 12-week scan, I was told I had a missed miscarriage, also called a silent miscarriage, which meant the baby died a long time ago but my body hadn't showed any signs. I was devastated. I also couldn’t believe that they were going to just send me home with my dead baby inside me, and no advice about what to do."

I was devastated. I also couldn’t believe that they were going to just send me home with my dead baby inside me, and no advice about what to do."

Lisa’s story

As with other health issues such as mental health, around which there is tremendous taboo still, many women report that no matter their culture, education or upbringing, their friends and family do not want to talk about their loss. This seems to connect with the silence that shrouds talking about grief in general.

Susan, 34, writer, USA

“I’ve been on the fertility train for nearly 5 years. As my own IVF began, I quickly learned that I had no idea what I was in for; it was so physically and emotionally exhausting. Thankfully, I did get pregnant, and my husband and I were so excited. However, after 7 weeks, the baby stopped growing. I then quit IVF hormones, and after 2 more weeks, the miscarriage began. It lasted 19 days. I didn’t realize miscarriages were a long process of pain and heavy bleeding. That the realities of fertility and miscarriage are so shrouded behind shame and silence. "

"

Susan's story

Stillbirths happen later in pregnancy, and more than 40% occur during labour, many of which are preventable. Around 84% of stillbirths take place in low- and lower middle-income countries. Providing better quality of care during pregnancy and childbirth could prevent over half a million stillbirths worldwide. Even in high-income countries, substandard care is a significant factor in stillbirths.

There are clear ways in which to reduce the number of babies who die in pregnancy – improving access to antenatal care (in some areas in the world, women do not see a health care worker until they are several months pregnant), introducing continuity of care through midwife-led care, and introducing community care where possible.

Integrating the treatment of infections in pregnancy, fetal heart rate monitoring and labour surveillance, as part of an integrated care package could save 832 000 who would otherwise have been stillborn.

How women are treated during pregnancy is linked to their sexual and reproductive rights, over which many women around the world do not have autonomy.

Societal pressures in many parts of the world can mean that women get pregnant when they are not physically or mentally ready. Even in 2019, 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy have no access to modern contraception. And when they do get pregnant, 30 million women do not give birth in a health facility and 45 million women receive inadequate or no antenatal care, putting both mother and baby at much greater risk of complications and death.

Emilia, 36, retailer, Colombia

"When I had a stillbirth at 32 weeks, my baby already had a name. I rushed to the clinic with very high blood pressure. After a checkup, the doctor told me to take some rest and prescribed a medication to lower my blood pressure. After a week I still had the same symptoms. The doctor rushed me to take an ultrasound and he told me that the baby had no vital signs. If I had been given more information from the very beginning, and received more medical attention at critical moments, my baby could have been saved. "

"

Emilia’s story

How women are treated during pregnancy is linked to their sexual and reproductive rights, over which many women around the world do not have autonomy.

Societal pressures in many parts of the world can mean that women get pregnant when they are not physically or mentally ready. Even in 2019, 200 million women who want to avoid pregnancy have no access to modern contraception. And when they do get pregnant, 30 million women do not give birth in a health facility and 45 million women receive inadequate or no antenatal care, putting both mother and baby at much greater risk of complications and death.

Divya Samson Panabakam, 30, consultant, India

"In 2013 I had my first miscarriage. As soon as I started bleeding I went to the hospital and I was sent to get a sonogram, but the person in charge thought that I wasn’t married and made me wait. I asked her: “Even if I wasn’t married, why would you want to treat someone who is losing a baby this way?”. She just looked at me and replied: 'It’s not an emergency, only a woman over 60 would be treated as an emergency case'."

She just looked at me and replied: 'It’s not an emergency, only a woman over 60 would be treated as an emergency case'."

Read More

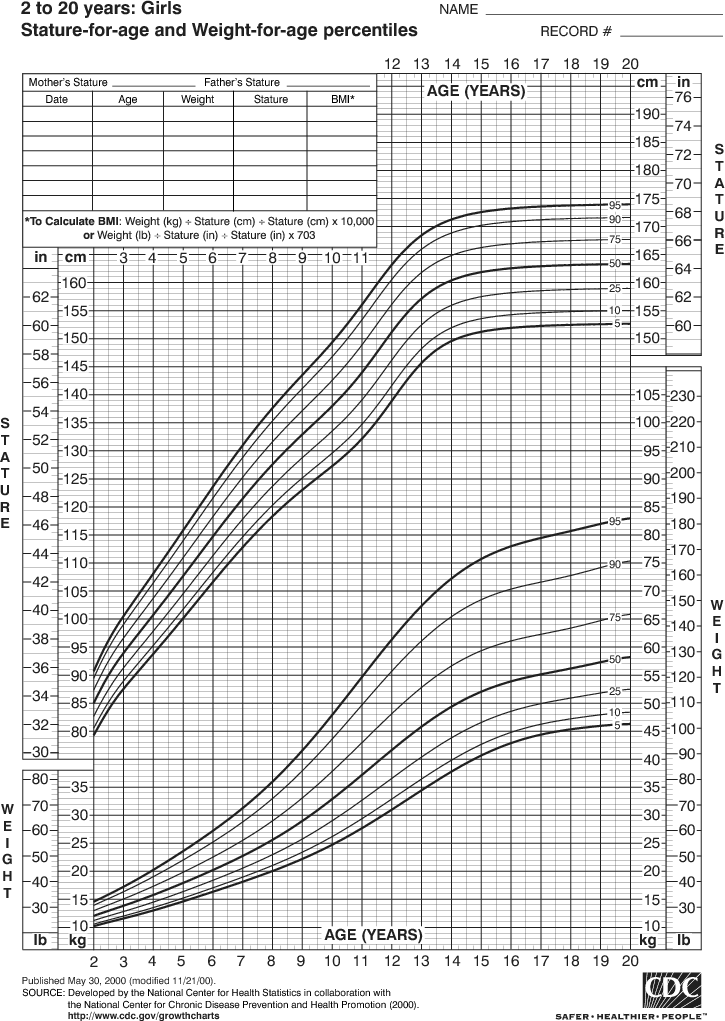

Cultural practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage are hugely damaging to girls’ sexual and reproductive health, and the health of their babies. Having babies too young can be dangerous for both the mothers and the babies. Adolescent mothers (aged 10 – 19 years) are far more likely to have eclampsia or uterine infections than women aged 20-24 years, which can increase the risk of stillbirth. Babies born to women younger than 20 years are also more likely to be of low birthweight, preterm, or have severe neonatal conditions, all of which can increase the risk of stillbirth.

FGM increases a woman’s risk of prolonged and obstructed labour, haemorrhage, severe tearing and a need for instrumental delivery. Her baby is much more likely to need resuscitation at delivery and faces a high risk of death during labour or after birth.

Putting women at the centre of their care is vital to a positive pregnancy experience – biomedical and physiological aspects of care need to be joined with social, cultural, emotional and psychological support.

Yet many women, even in developed countries with access to the best healthcare, receive inadequate care after losing a baby. The language used around miscarriage and stillbirth can be traumatic in itself – terminology referring to an “incompetent cervix” or a “blighted ovum” can be distressing.

Andrea, 28, stylist, Colombia

"When I was 12 weeks pregnant, I went for a check-up and had an ultrasound. The doctor told me that something was wrong without specifying what it was. The next day I woke up and noticed that the bed sheet were stained with blood. I did not receive any information on why I had a miscarriage. The nurses were very cold and unfriendly and they behaved as if it was just a medical procedure. Among all the staff at the hospital the only one who had a bit of humanity was the doctor, who later reassured me that I could try again to get pregnant. "

"

Andrea's story

Depending on the policy of the hospital, the babies’ bodies may be treated as clinical waste and incinerated. Sometimes when a woman finds out her baby has died, she is required to carry the dead baby for several weeks before she can give birth. Though there may be clinical reasons for this delay, this is distressing to the woman and her partner. Even in developed countries, women may birth their dead baby in maternity units, surrounded by women with healthy babies.

Not all hospitals or clinics can adopt new policies or provide more services. This is a reality of overburdened health care systems. Yet encouraging more sensitivity in dealing with bereaved couples, and removing the taboo and stigma around talking about baby loss does not need to cost money. This is reflected in some of the stories featured here.

Becky, 38, primary school teacher, Viet Nam/UK

"My husband and I were over the moon when I fell pregnant with twin girls and were devastated to lose one of them – we called her Isla - at 34 weeks. I was terrified that we were going to lose our other baby too, and insisted on staying in hospital. The next day I delivered our girls via caesarean section. Overall the hospital was incredibly supportive and we were given a private room and time to spend with Isla. However a number of doctors showed complete insensitivity with one even asking why I was crying and telling me to cheer up".

I was terrified that we were going to lose our other baby too, and insisted on staying in hospital. The next day I delivered our girls via caesarean section. Overall the hospital was incredibly supportive and we were given a private room and time to spend with Isla. However a number of doctors showed complete insensitivity with one even asking why I was crying and telling me to cheer up".

Becky's story

Healthcare staff can show sensitivity and empathy, acknowledge how the parents feel, provide clear information, and understand that the parents may need specific support both in dealing with their loss and in potentially trying to have another baby. Providing human rights based care, that is socioculturally relevant, respectful and dignified is as much a requirement for competent maternal and newborn care as clinical competence.

Sarah, 40, civil servant, Australia

"Stillbirth is so common in Australia when it happens to you or someone you know. It’s suddenly everywhere. Stillbirth affects around 2000 Australian families each year. Our rate of stillbirth hasn’t changed in 20 years and for Indigenous Australians it’s twice as high. Yet before it happened to me and I became that one in six, I never considered that babies could die in utero. It’s never spoken about. The doctor told me about my increased risk of cord prolapse with polyhydramnios but no one mentioned I was at an increased risk of fetal death".

It’s suddenly everywhere. Stillbirth affects around 2000 Australian families each year. Our rate of stillbirth hasn’t changed in 20 years and for Indigenous Australians it’s twice as high. Yet before it happened to me and I became that one in six, I never considered that babies could die in utero. It’s never spoken about. The doctor told me about my increased risk of cord prolapse with polyhydramnios but no one mentioned I was at an increased risk of fetal death".

Sarah's story

Key messages around support

The Unacceptable Stigma And Shame Women Face After Baby Loss Must End

Op-ed by Dr Princess Nothemba Simelela, Assistant director-general for family, women, children and adolescents, WHO

Find out more

More on WHO's work

More on WHO's work with partners

All illustrations WHO/M. Purdie

Join WHO in action

Coping with the loss of a child - together

There is nothing more devastating in the world than the death of a child. It is difficult for families to imagine how to cope with such a loss. While parents never stop thinking about and missing their child, grief changes over time. According to parents, the acute and deep feelings of grief become less pronounced and more manageable over time. However, each person experiences grief differently. Grief does not follow a set schedule or pattern. Today you can feel progress, and tomorrow the simplest tasks seem impossible. Sometimes family members are surprised or even guilty to find that they have regained the ability to laugh at something. These feelings and reactions are natural.

It is difficult for families to imagine how to cope with such a loss. While parents never stop thinking about and missing their child, grief changes over time. According to parents, the acute and deep feelings of grief become less pronounced and more manageable over time. However, each person experiences grief differently. Grief does not follow a set schedule or pattern. Today you can feel progress, and tomorrow the simplest tasks seem impossible. Sometimes family members are surprised or even guilty to find that they have regained the ability to laugh at something. These feelings and reactions are natural.

Watch this video

Grief

Grief is a natural reaction to the loss of a loved one. This feeling is individual. Everyone experiences grief in their own way, with different strengths and for different times. There is no standard set of emotions that you should feel after losing a child. Common feelings and reactions include:

- shock

- sadness

- fear

- anger

- guilt

- sadness

- feeling of loneliness

- anxiety and constant agitation

- unwillingness to contact others

- constant thoughts and memories of the child

- dreams of spending a little more time with the child and longing for missed moments

- trouble falling asleep and insomnia

- excessive sleepiness

- changes in appetite

- loss of interest in entertainment

- trouble concentrating

Everyone can experience grief, but everyone experiences it in their own way. Even in the same family, spouses can have completely different reactions. Children and teens also experience grief in their own way, with different emotions and behaviors ranging from tears and sadness to disobedience and guilt. All these feelings are normal.

Even in the same family, spouses can have completely different reactions. Children and teens also experience grief in their own way, with different emotions and behaviors ranging from tears and sadness to disobedience and guilt. All these feelings are normal.

Watch this video

When to seek help

Counseling professionals—psychologists, counselors, and social workers—can be a source of support during bereavement. If a person asks for help, this does not mean that he somehow experiences his grief incorrectly. For some families, a mental health professional simply provides additional support. Parents and siblings of a departed child are often afraid that their friends and relatives will get tired of hearing about their grief. With a consultant, you can calmly share your experiences. A mental health professional creates a safe environment in which to talk about feelings and helps parents and siblings cope with grief.

In some cases, family members may present with symptoms of mental disorders such as anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Specific thoughts and feelings to discuss with a mental health professional:

Specific thoughts and feelings to discuss with a mental health professional:

- thoughts about reuniting with the child

- thoughts of hurting yourself or someone else

- sense of worthlessness

- slow movement

- auditory and visual hallucinations

- severe anxiety or anxiety

- sleep problems, nightmares

- difficulty doing daily activities

- refusal to believe in the death of a child

- avoiding baby reminders

- indignation

- loss of meaning and purpose in life after the death of a child

- sense of detachment

- sudden frightening memories that make you feel like you are reliving them

If you have thoughts of harming yourself or others, seek help immediately.

- Call the emergency number (112 in Russia, 911 in the US) and report such thoughts.

- Call the number of the Unified Helpline 8-800-2000-122 or the Emergencies Ministry's emergency psychological help line 8(495)989-50-50.

- Go to the nearest emergency room.

Grief is a natural reaction to the loss of a loved one. This feeling is individual. Everyone experiences grief in their own way, with different strengths and for different times.

-

Modified June 2018

Death of a child: how to help a family survive grief

The death of a loved one is always difficult to survive. But when a child dies, it is a terrible loss for his parents. It was on working with such losses that the psychologists of the St. Petersburg public organization of social assistance "Family Information Center" focused. The loss of a child can be a deep life-long trauma for both parents - for those who drown themselves in this trauma, in despair, relationships both within the family and connections with external society collapse or are distorted. The center's psychologist, Nadezhda Stepanova, tells how the Family Information Center specialists help parents and other family members to survive the death of a child and find new hopes.

"Family Information Center" helps women who have suffered perinatal loss and their families, families who have lost a child, as well as when a premature or disabled child is born.

— Who experiences the loss more severely – a family that has lost a baby, or a family that has lost an older child?

- If we talk about the fact that it is harder to lose an older child than a newborn, then I agree and no. Each family, each situation has its own characteristics. But yes, more and more social and psychological connections are formed with parents as the child grows, these are mugs, a kindergarten, friends, relatives ... all these people and communities came into contact with the child, the family. These parents thus had more memories, more hopes. And even after the appearance of another child in the family, the parents still have memories of the lost one, but this is natural. Another question is if the parents did not subtly burn out this loss, and this may be for various reasons. For example, one of the parents was indirectly to blame for the fact that the child died in an accident.

For example, one of the parents was indirectly to blame for the fact that the child died in an accident.

— It turns out that egoism prevails in people's experiences: “I worry because my expectations have not come true”, “My grief”, and so on. But then there is very little room left for the departed children themselves...

— But this is what most often happens with the loss of any loved one, not necessarily a child. More often we worry not about him, but about the fact that we were left without him and now we need to rebuild our world. We cry about ourselves, our unfulfilled dreams, plans, expectations….

— Do many parents who have lost children suffer from feelings of guilt? And how do you work with people if this guilt is real?

Everyone suffers. And how to work is a very difficult question. When a young woman eight months pregnant jumps with a parachute and loses her baby, it is, of course, very difficult to work with her - she understands that it is her fault that her actions provoked the loss. But here we must admit the fact - yes, the act was rash. Perhaps the woman was not very ready for motherhood, in her picture of the world it was not at all assumed that children could die. Or the family was preparing for the birth of a child, they did everything that was necessary and possible, but the feeling of guilt is still present. How to work? Depending on the situation. It is impossible to say that the feeling of guilt goes away quickly and forever. Sometimes this takes a long time.

But here we must admit the fact - yes, the act was rash. Perhaps the woman was not very ready for motherhood, in her picture of the world it was not at all assumed that children could die. Or the family was preparing for the birth of a child, they did everything that was necessary and possible, but the feeling of guilt is still present. How to work? Depending on the situation. It is impossible to say that the feeling of guilt goes away quickly and forever. Sometimes this takes a long time.

6 documentaries about survivors of the death of loved ones

- The funeral of a deceased child - how do you discuss this problem with clients? Especially when it comes to newborn babies.

— Often mothers sometimes do not even want to look at their dead newborn children, they do not want to take them away to bury them. Until a certain time, there was such a practice among doctors - to say: “Why do you need to look?” But if a woman did not bury her child, all sorts of terrible pictures line up in her in the future. For example, a woman came already about her grandchildren (she is a fairly young grandmother), but it turned out that her child died in her first marriage, but she did not look at him, did not begin to take him away, and then she began to imagine his appearance, then I began to search the Internet for information about what happens to the bodies of such babies - someone says that they are used as a biomaterial, someone says that they are thrown into a common pit, and so on. And she says: “I began to imagine all this. And how can I live with it now? Families who have already made a decision come to me, the woman left the hospital and now she is looking for confirmation from me that she did the right thing by refusing to look at the child and bury him. But for believers, the question of whether or not to bury a child does not arise at all. Therefore, it is important that psychologists working with such families have a unified approach and understand the necessity and importance of this stage.

For example, a woman came already about her grandchildren (she is a fairly young grandmother), but it turned out that her child died in her first marriage, but she did not look at him, did not begin to take him away, and then she began to imagine his appearance, then I began to search the Internet for information about what happens to the bodies of such babies - someone says that they are used as a biomaterial, someone says that they are thrown into a common pit, and so on. And she says: “I began to imagine all this. And how can I live with it now? Families who have already made a decision come to me, the woman left the hospital and now she is looking for confirmation from me that she did the right thing by refusing to look at the child and bury him. But for believers, the question of whether or not to bury a child does not arise at all. Therefore, it is important that psychologists working with such families have a unified approach and understand the necessity and importance of this stage. In Germany, if at first the family does not want to look at the child and bury him, she is given some time to comprehend her desires and actions, for which the family can change her mind. It would be great if we adopted their practice.

In Germany, if at first the family does not want to look at the child and bury him, she is given some time to comprehend her desires and actions, for which the family can change her mind. It would be great if we adopted their practice.

— If there are other children in the family, do you also work with them?

- Yes. You have to work with children. After all, children understand what is happening. If parents do not tell them about what happened, they develop neuroses, fears, and sometimes not directly related to death. And parents often do not tell their children about the death of a sibling. They explain it like this: “Why?” Especially if a newborn baby dies, they come up with some kind of story or generally impose a ban on this topic. At the same time, the child sees that everyone is crying, that mom and dad are not up to him, he can be sent to his grandparents. The child feels isolated from the family, in a kind of isolation zone. And he has some fantasies of his own, with which he then has to cope on his own, the fantasies of a child are sometimes worse than reality. So I think that the child should definitely be told about the death of his brother or sister, but find the right time for this and think about what words to say.

So I think that the child should definitely be told about the death of his brother or sister, but find the right time for this and think about what words to say.

— But even a child himself can feel acutely the death of a brother or sister.

- Of course. Again, especially if there is already some history of their communication. And most importantly: in any case, a child can also become depressed because of such events in the family. It is believed that if a child jumps and jumps, it means that he is having fun and well. But he can in such a way draw the attention of his parents to himself so that they switch and they become fun, and the child thus receives for himself the “former” parents, such as they were before the loss.

— How should other neighbors of those who are experiencing the loss of a child behave? What can not be said, and what can and should be said?

- Rather, I will say that it is impossible. You can’t say immediately after it happened: “You will have more children. ” After all, the parents have not yet cried, they have not burned out. You can’t offer to go to work, forget yourself, stop crying - that is, you can’t offer any kind of blocking of emotions. Moreover, you can’t say: “I’m tired of you crying.” It is impossible to blame, even if objectively the parents are to blame for the death of the child. You can’t devalue the loss: “the pregnancy was not on time”, “whatever is done, everything is for the better” and the like ... The parents themselves already have enough guilt, you just need to support them. In general, you can touch these topics only when the parents themselves want to talk about it. What needs to be done? Give the opportunity to cry as much as necessary. But at the same time, look at whether a person closes in on himself or not. If he leaves society, this is an alarming sign. In this case, you need to call, come, do not leave your attention. To talk and, most importantly, to listen, keeping oneself from advice and comparisons: one cannot say that everything is much worse for someone, this is also a depreciation.

” After all, the parents have not yet cried, they have not burned out. You can’t offer to go to work, forget yourself, stop crying - that is, you can’t offer any kind of blocking of emotions. Moreover, you can’t say: “I’m tired of you crying.” It is impossible to blame, even if objectively the parents are to blame for the death of the child. You can’t devalue the loss: “the pregnancy was not on time”, “whatever is done, everything is for the better” and the like ... The parents themselves already have enough guilt, you just need to support them. In general, you can touch these topics only when the parents themselves want to talk about it. What needs to be done? Give the opportunity to cry as much as necessary. But at the same time, look at whether a person closes in on himself or not. If he leaves society, this is an alarming sign. In this case, you need to call, come, do not leave your attention. To talk and, most importantly, to listen, keeping oneself from advice and comparisons: one cannot say that everything is much worse for someone, this is also a depreciation.

— And if a person abruptly refuses to communicate?

- If a person lives alone, then you still need to call sometimes, just to say: "I'm here, you can call me at any time." You can write SMS, write messages on the Internet, on Skype. Today there are many opportunities to let a person know that he is not alone.

A woman should be allowed to cry. What about a man?

Men also cry. And it's great when a man can afford it. For men, I suggest, if possible, to take a joint vacation - in order to be with yourself, with your wife. Some families leave - not for fun, but in order to jump out of the familiar and traumatic space. It is important for a man to know how he can help his wife, how to answer questions from others, for example: “Yes, we lost a child, but now I don’t want to talk about it.” But this does not mean that he is not worried and the man does not need time to live the loss.

— Do people come to you years after the loss?

- I must say that they rarely come right away, that is, in an acute state of grief. But it happens that they come after a very long time. Sometimes they come with other questions related to family relations, and when I start asking about the family's past, it turns out that there was a loss of a child. And here, if a person is ready to talk about it, then either this is a lived story, and he tells it in the same way as I can tell my story, or these are strong feelings, emotions, grief is re-experienced, people say: “We didn’t tell anyone about this ".

But it happens that they come after a very long time. Sometimes they come with other questions related to family relations, and when I start asking about the family's past, it turns out that there was a loss of a child. And here, if a person is ready to talk about it, then either this is a lived story, and he tells it in the same way as I can tell my story, or these are strong feelings, emotions, grief is re-experienced, people say: “We didn’t tell anyone about this ".

— Older people who once experienced a loss can somehow support young people with the same problem?

- Of course. An older person might say, “Look at me, I'm 75 years old. It’s hard for you now, you can’t forget it, but you can survive it. ” Now I will say a phrase that can shock many in this context: one way or another, any experience enriches a person. Suffering also makes our picture of the world richer. And here the elderly can show this by their own examples. But when the only grandson or granddaughter dies, grandparents experience no less strong feelings than the parents of the child. After all, this is also connected with their unfulfilled expectations, they think that other grandchildren may not wait.

After all, this is also connected with their unfulfilled expectations, they think that other grandchildren may not wait.

— Perhaps, in general, one of the main problems is that we expect too much from each other?

- Yes. And when our expectations and our fantasies do not come true, it becomes a disaster for us. There are people who are ready to quickly rebuild, and there are people who are not ready. Of course, in a crisis situation, any discrepancies are exacerbated.

— There is an old saying: “God gave, God took”. In fact, this is a summary of a fragment from the biblical Book of Job. Do you think people used to take easier the deaths of their children?

- I think so. There was more hope in God and understanding that a person is not able to fully manage his life and death. And I also have to tell clients that each of us has his own deadline.

— Doesn't the lack of such an understanding give rise to hyper-responsibility?

- I talk about this all the time at seminars and webinars - not only on loss, but on issues related to children in general. Still, parents need to be easier in certain matters. Sorry, but in the 50s and 60s, a child often had a single enamel pot. And now they are arguing: "Here, the child does not go to the blue pot, let's buy him a red one." And the mother is told that if her child does not go to the potty at the age of one and a half, then she is a bad mother. And there is another point: before women gave birth to how many children? How much God has given. And now? Most are one or two. Moreover, social and economic conditions could have been much worse before. Therefore, I often say that it is not necessary to neuroticize parents - they also have a life besides the child. For a child, it is a disaster when the life of his parents is focused only on him. Parents of children with special needs are more susceptible to this. I remember one family in which the youngest child had very severe symptoms - lying down, with mental retardation. He lived to be 10 years old and at that age he could only lie down and ride - nothing more.

Still, parents need to be easier in certain matters. Sorry, but in the 50s and 60s, a child often had a single enamel pot. And now they are arguing: "Here, the child does not go to the blue pot, let's buy him a red one." And the mother is told that if her child does not go to the potty at the age of one and a half, then she is a bad mother. And there is another point: before women gave birth to how many children? How much God has given. And now? Most are one or two. Moreover, social and economic conditions could have been much worse before. Therefore, I often say that it is not necessary to neuroticize parents - they also have a life besides the child. For a child, it is a disaster when the life of his parents is focused only on him. Parents of children with special needs are more susceptible to this. I remember one family in which the youngest child had very severe symptoms - lying down, with mental retardation. He lived to be 10 years old and at that age he could only lie down and ride - nothing more. But his father is a doctor, his mother is a teacher, both worked and work, they did not stop their lives, but they did not send the child to a boarding school either. The child lived with them. What did they do? They secured the space in which he was, for example, made him a sleeping place practically on the floor - so that he would not fall and hit.

But his father is a doctor, his mother is a teacher, both worked and work, they did not stop their lives, but they did not send the child to a boarding school either. The child lived with them. What did they do? They secured the space in which he was, for example, made him a sleeping place practically on the floor - so that he would not fall and hit.

— Didn't this couple feel guilty about the fact that they should have taken more care of the child, and then he would have reached at least a slightly higher level of development?

— You know, I think that such thoughts can arise in any parent - it does not matter if his child is healthy or sick, whether he is alive or dead. There is always a feeling that you didn’t finish something, didn’t finish it, didn’t have time, overlooked it ... But this couple still tried to give their child a lot - they continued to engage in his rehabilitation even when experts told them that there would be no progress. Parents answered: “But he is alive, so we will do it. ”

”

— You also work with families with children with disabilities. Can a family who is still only afraid that a child will either be born with developmental disabilities or not survive come to you?

— Our project provides that we pick up a family when, at the stage of pregnancy, doctors reveal that the child may have some kind of pathology. Here it is very important to let a woman understand that she is not God, but a mother, and is doing the maximum that she can. If during this period the whole family applies, then it is very important to help everyone decide what and how each of them can do in this situation. When the family comes out of the state of disorientation and moves on to real action, it gives people the opportunity to see both these actions themselves and their results, which ultimately gives hope. After all, there is such a problem: often, if a woman gives birth to a child with certain developmental disorders, she fences herself off from society: “No one will understand me.