How to help an over emotional child

12 Tips for Dealing with an Overly Emotional Child

Home » Parenting » From the Mouths of Moms » 12 Tips to Deal With an Overly Emotional Child

By Krissy of B-Inspired Mama 42 Comments

Disclosure: This site contains affiliate links; as an affiliate and Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Read my full disclosure policy for more information.

Sharing is caring!

8.7K shares

Have an Overly Emotional Child?

Can’t find time to read all of those parenting books and magazines? Don’t have a lot of mommy friends to bounce ideas off of? Kids go crazy every time you get on the phone to ask a friend their advice? No problem; I’ll do the work for you! I’m bringing you kid-tested parenting tips for specific parenting challenges “from the mouths of moms.” We’ve already shared lots of tips for dealing with picky eaters, getting kids to sleep better, ensuring stress-free play dates, cooking with kids, potty training success, promoting sibling bonding, teaching good touch bad touch, and taming toddler aggression. Now here are direct quotes from a diverse group of moms (with kids of all ages and tons of experience) on dealing with an overly emotional child…

Alright, Mamas, how do you deal with an overly emotional child?

1. Make Eye Contact

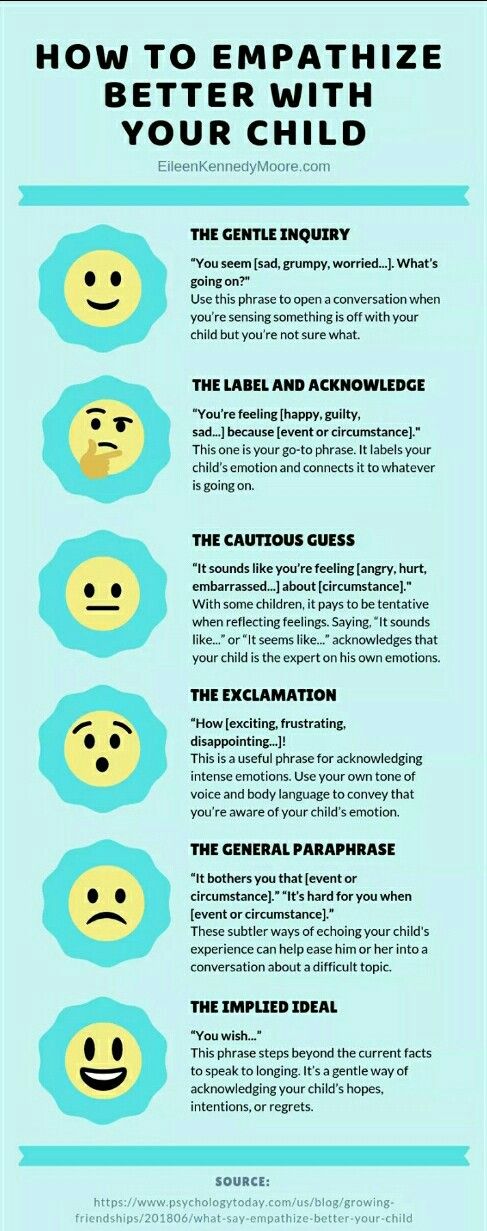

“I get down to his level (as in physically bend down to make eye contact) and acknowledge how he is feeling. Keep my voice calm and try to help him through it until he feels calm again.” Ness from One Perfect Day

2. Validate Their Emotions

“I think one important thing to do (that I have such a hard time remembering to do sometimes) is to validate their emotions. Make sure they know that you understand what they are feeling before immediately redirecting or reprimanding.” Krissy from B-Inspired Mama

[Tweet “Tip for Calming an Emotional Child: Validate her feelings first. “]

3. Keep A Routine

“I try to keep things predictable, talk to my son about what is going to happen today, talk him through changes to plans or routines so there’s no surprises that could trigger an emotional meltdown. ” Ness from One Perfect Day

” Ness from One Perfect Day

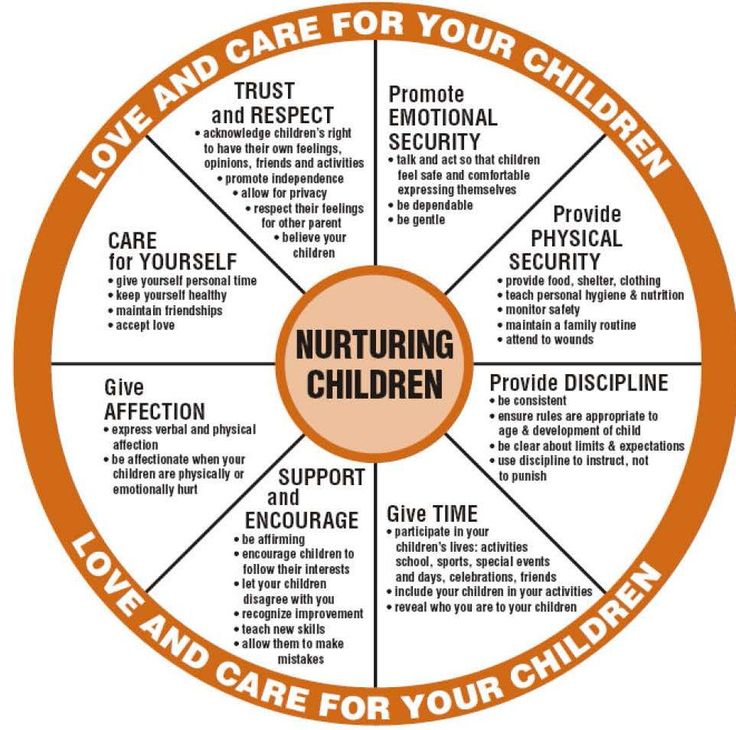

4. Give Them A Supportive Environment

“I used to try and figure out ways to try and avoid [my daughter’s] tears; I can see now that it is just the way she naturally expresses herself. She ‘breaks down’ in many different situations. I give her a supportive environment where she knows that it is okay to release her emotions. The wave of emotions will pass in a few minutes and with a warm hug. I have no idea how her deeply felt emotions will impact her as she grows into her teen years. I hope my support is teaching her that it is better to release the emotion than to bottle it up inside.” Jennifer from Kitchen Counter Chronicles

5. Ease Transitions

“Make sure you give them as much info as you can … ‘We will be going to leave in 10 minutes to go ______. This is what we will be doing there. This is who will be there.’” Laura from PlayDrMom

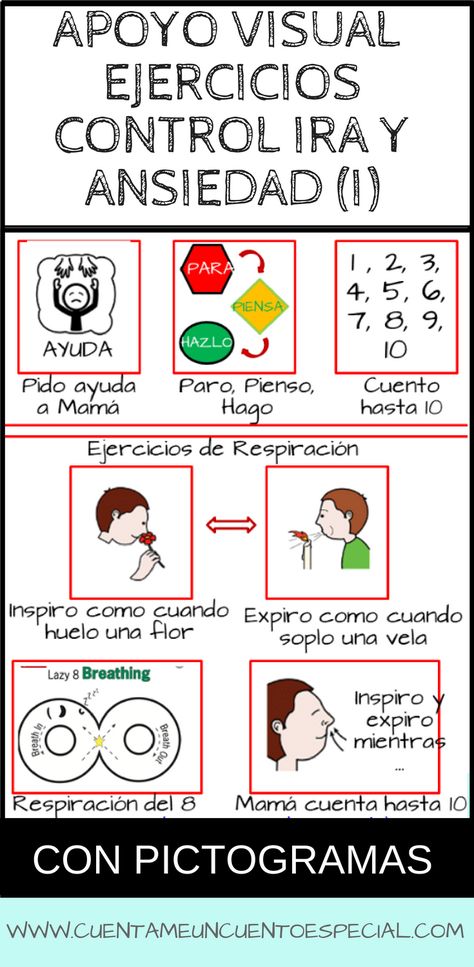

6. Distract Them With Counting

“We validate his feelings first – ‘I know you miss daddy but he’s had to go to work so that we can have nice toys and food,’ etc… then when they are starting to calm down I have found that counting to 20 with me really calms him down – it seems to focus him and then we can talk about where Daddy is. ” Cerys from Rainy Day Mum

” Cerys from Rainy Day Mum

[Tweet “Tip for Calming an Emotional Child: Try counting with them to 20. “]

7. Give Them Time to Calm Down

“Also, I’ve learned that if they get really upset it can help to give them some time to calm down before trying to talk about what they are upset about – validate the emotion and then discuss it later.” MaryAnne from Mama Smiles

8. Try a Tickle

“We call it ‘tickle torture’ but it is really just a way to make your child laugh. We say, “If you aren’t able to calm down, you have three options: 1) tickles, 2) boops or 3) kisses.” 9 times out of 10 this alone gets him to snap out of his bit of crazy. Then we can address the behavior if we feel we need to do so.” Marnie from Carrots Are Orange (Check out lots more alternatives to “time out” from Marnie!)

9. Give a Big Hug

“I find what works is telling her I understand why she feels this way, but I don’t understand why she is acting this way. When we are mad, we don’t hit. When we are sad, we don’t throw ourselves on the ground. I also take her aside and give her a very big, deep pressure hug. That sometimes helps her, too.” Danielle from 52 Brand New

When we are mad, we don’t hit. When we are sad, we don’t throw ourselves on the ground. I also take her aside and give her a very big, deep pressure hug. That sometimes helps her, too.” Danielle from 52 Brand New

[Tweet “Tip for Calming an Emotional Child: Try a deep pressure hug. “]

10. Teach Them to Use Their Words

“We’ve focused a lot on talking about our feelings and using our words to express how we feel. As it’s something we’ve done from birth, if we’re ever having a melt down I can generally just remind my daughter to use her words and that usually works to start to calm her down. I remind her that I can’t understand her but that I can understand that she’s upset and to tell me about it.” Deborah from Learn with Play @ Home

11. Make Sure They’re Basic Needs Are Met

“[My kids] seem to peak if they are tired or hungry. We make sure to have healthy, well balanced meals on a fairly scheduled basis AND have the kids get enough sleep. This doesn’t always help, but is worth a go!” Amanda from The Educators’ Spin On It

This doesn’t always help, but is worth a go!” Amanda from The Educators’ Spin On It

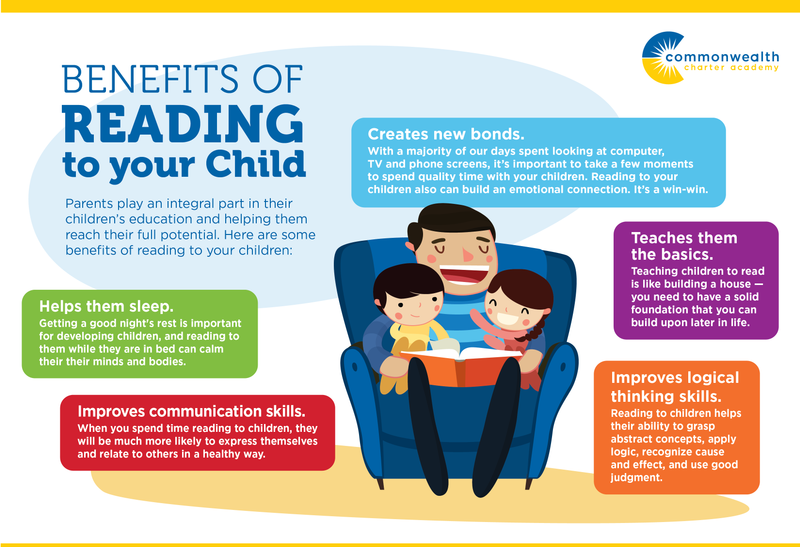

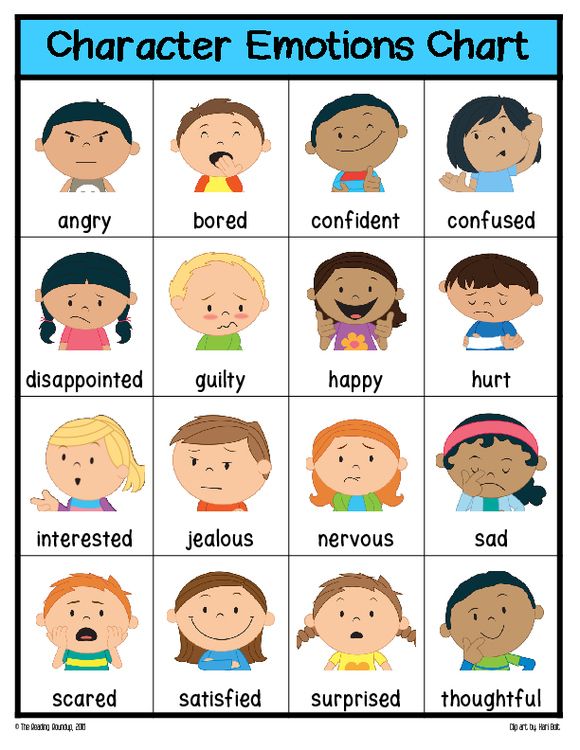

12. Teach Them About Emotions

“We just participated in a children’s book swap with Laura from PlayDrMom and received the children’s book Today I Feel Silly: And Other Moods That Make My Day by Jamie Lee Curtis. It’s a great book to teach kids about emotions and start a conversation about how to appropriately express them.” Krissy from B-Inspired Mama

[Tweet “Tip for Calming an Emotional Child: Read children’s books about emotions. “]

Do you have a child who you would consider “overly emotional”? How do you handle it? Join the conversation in the comments below!

More Parenting Tips “From the Mouths of Moms”:

If you like this, get lots more by signing up to get B-Inspired Weekly right in your inbox. And follow B-Inspired Mama on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Google+, and Pinterest! Also check out these link ups where B-Inspired Mama loves to share and find inspiration! This post may have affiliate or sponsored links.

Please see my disclosure policy.

Please see my disclosure policy. Sharing is caring!

8.7K shares

Filed Under: From the Mouths of Moms, Parenting Tagged With: From the Mouths of Moms, Kids Emotions, Parenting

About Krissy of B-Inspired Mama

Former M.Ed Art Teacher. Current Blogger & Social Media Influencer. Always Crazy & Creative Mama of 3.

Reader Interactions

6 Steps for Helping Your Child Handle Emotions

When my daughter was a preschooler, I remember joking about her future: “If she’s got a 13-year-old’s attitude now, how am I going to handle her when she’s actually a teenager?” Her emotions seemed bigger than she was, far too big for her tiny body. Surely she would be able to handle them better when she was older!

If only it were that easy, right? As our children grow, so do their feelings. Add to that the pitfalls of puberty, friendship drama, and kids who are desperately trying to be adults, and we have a minefield of feelings to navigate.

We might sometimes wish to return to the simplicity of toddler tantrums, but we must instead forge new ground as we walk alongside our kids. Emotions for kids can be difficult. Here’s how to help your child handle their emotions.

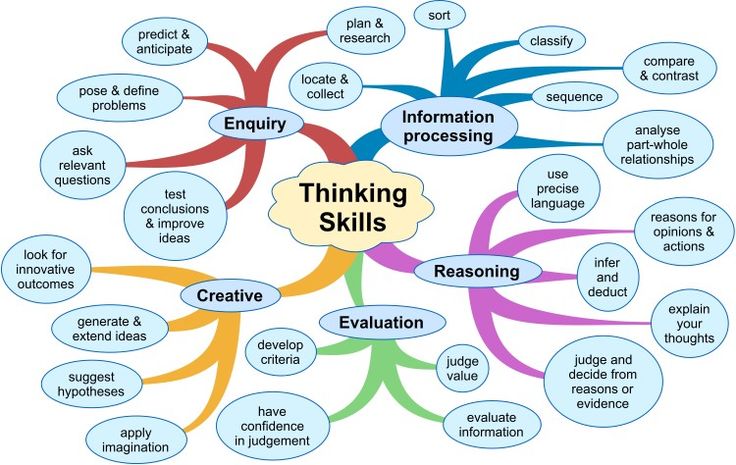

Why Emotional Understanding is Important for Your Child:

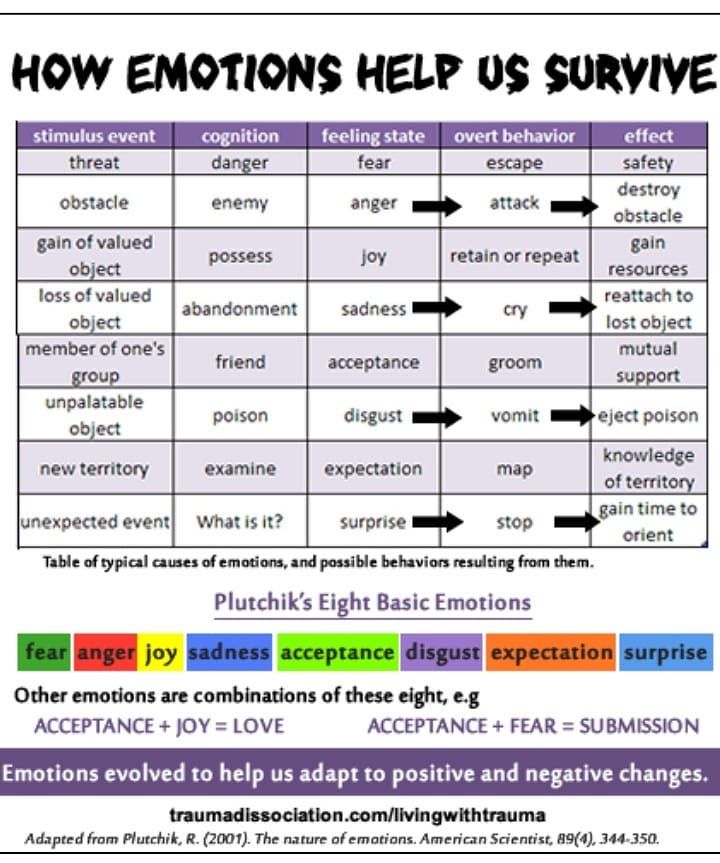

One of the certainties of parenting is that your children will experience all sorts of emotions (sometimes all in one day!) and will routinely face circumstances they don’t like. Helping your child to grow emotionally involves teaching them to recognize certain emotional responses in themselves and then to express those feelings appropriately.

Developing skills in this area will help your child to relate better to others, manage his or her behavior, and cope with situations of all kinds. It may also be a great benefit to your parent-child relationship, as your child grows in his capacity to explain his disappointments or frustrations with words, rather than acting out.

As parents, we can’t insulate our children from the ups and downs of life. What we can do is teach them to navigate those experiences in a way that grows their personal character as well as preserves and enhances the relationships in their lives.

What You Can Do:

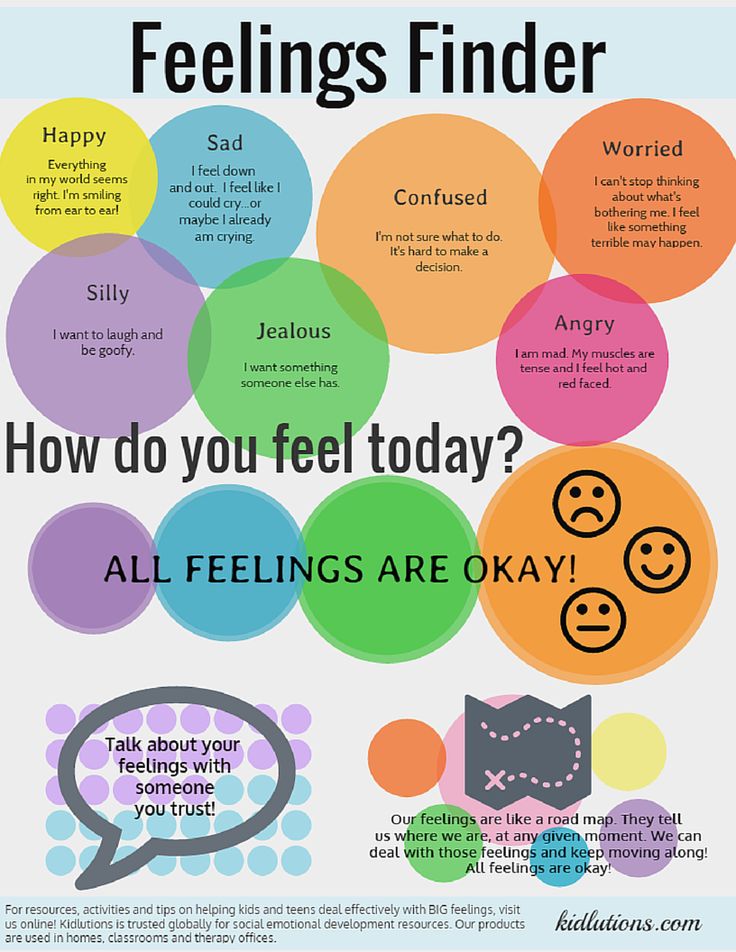

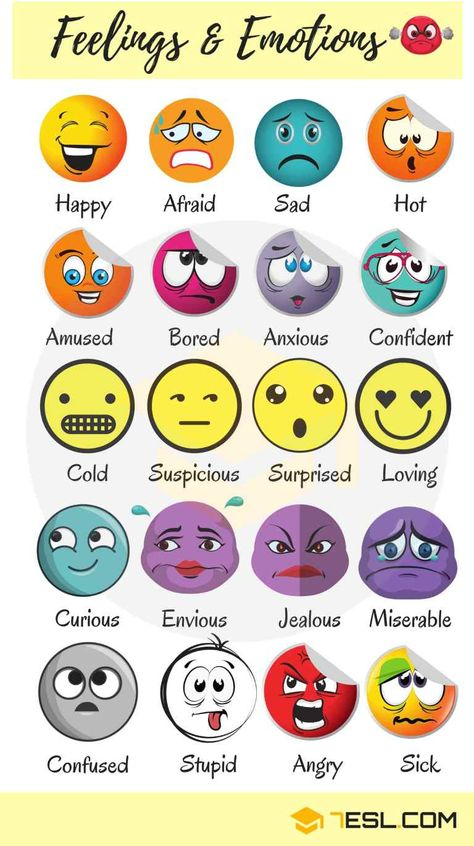

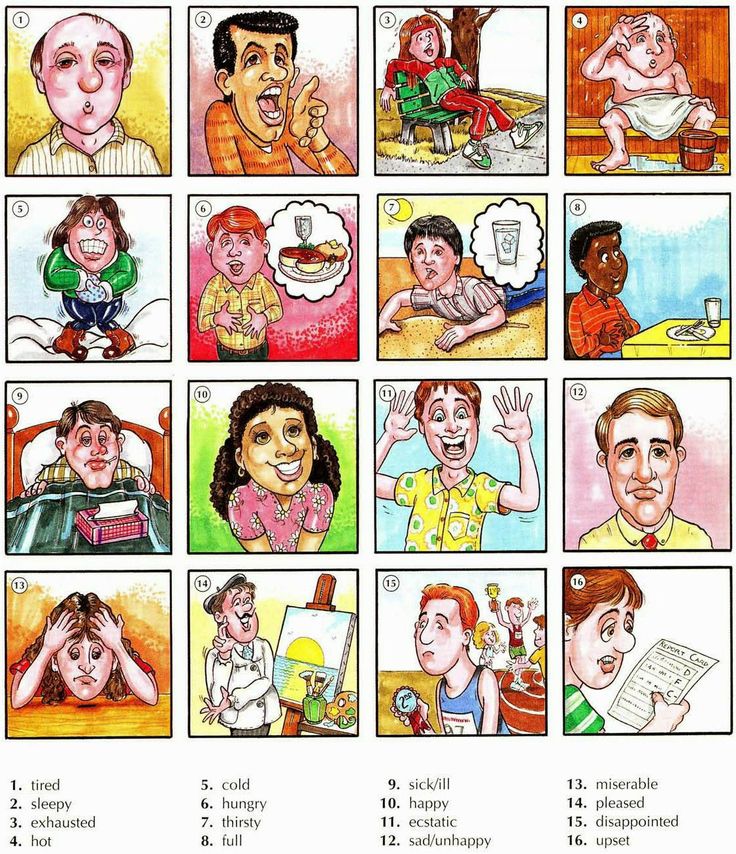

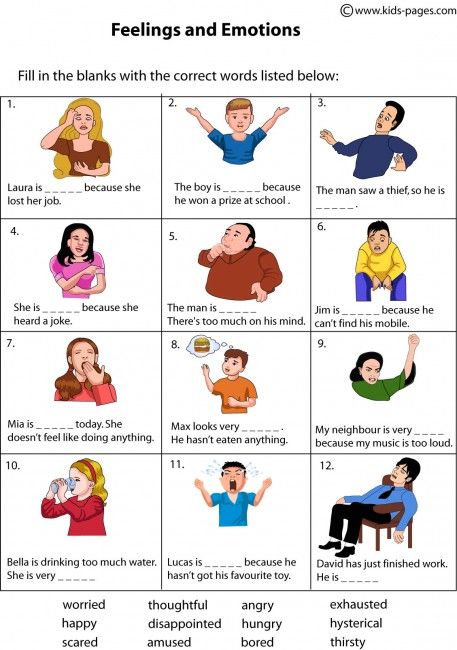

1. Give feelings a label.

For your younger child, these names will be as basic as mad, sad, and happy. As your child grows, those terms will become more specific and refined, such as frustrated, disappointed, or anxious. Identifying and naming feelings is essential to learning how to cope with them.

2. Discover the trigger.

Help your child back up and identify what led to feeling this way. It might have been when you said “No” to something he asked to do or something said or done by a sibling or friend.

3. Affirm the right to talk it out.

Let your child know that everyone feels these emotions sometimes and that there’s a right and a wrong way to express them. Let them know that they may not be able to help feeling how they do, but they can and should manage how they express that feeling. Your child must learn to be responsible for his or her words and reactions, regardless of the situation.

Let them know that they may not be able to help feeling how they do, but they can and should manage how they express that feeling. Your child must learn to be responsible for his or her words and reactions, regardless of the situation.

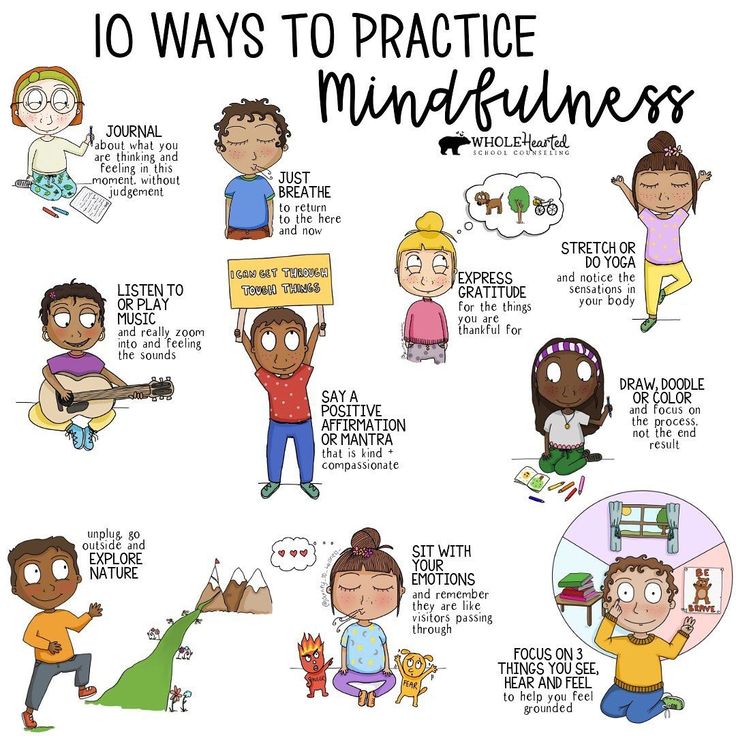

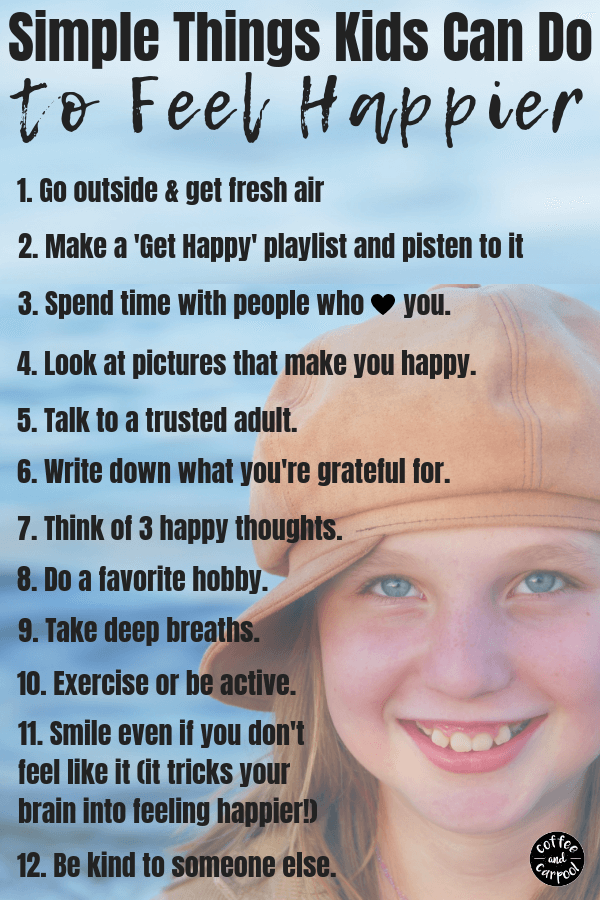

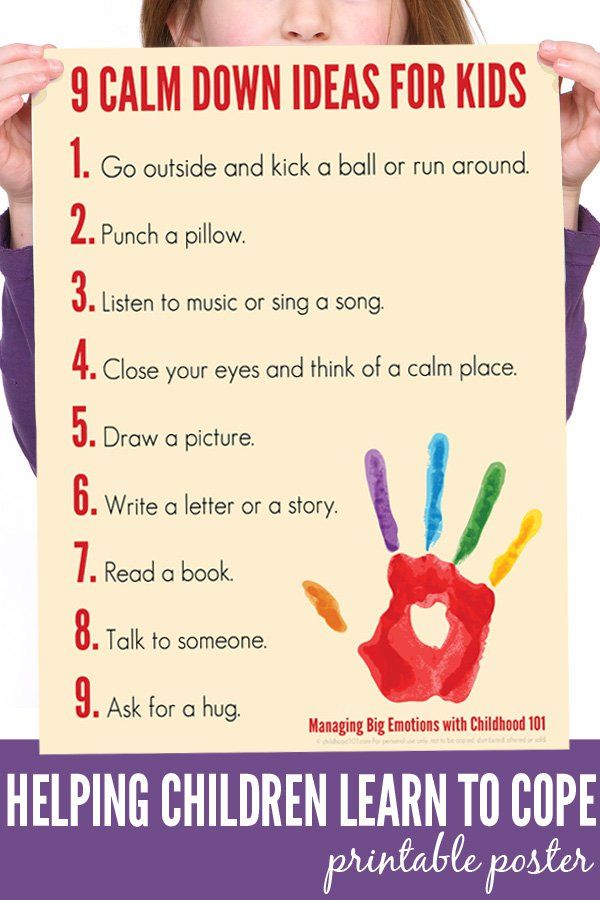

4. Teach specific coping skills.

It may be helpful to your child to learn to remove herself from a situation or take some time to think before responding. For a younger child, it might be as simple as counting to 10 before reacting.

5. Don’t try to fix everything.

The idea is to help your children learn to work through the problem, not to simply remove the problem. Why? Because as they get older, you’ll be less and less able to manipulate the world around your children and insulate them from a crisis. Good parenting means training them to handle whatever they encounter with emotional maturity and integrity.

6. Give emotional support.

Often, all our children need is a good hug and an acknowledgment that we know how they feel. When your child is working through something, keep the standards of behavior high, but show lots of affection to help them along. Additionally, tell them how proud you are when you see them handling their emotions with increasing maturity and reacting appropriately to tough situations.

When your child is working through something, keep the standards of behavior high, but show lots of affection to help them along. Additionally, tell them how proud you are when you see them handling their emotions with increasing maturity and reacting appropriately to tough situations.

Here are some other resources for helping your child handle their emotions.

Moms, how do you help your child handle their emotions? We would love to hear from you!

How to teach a child to control his emotions

Manipulation and tantrums: identifying the problem

Often children's tantrums are not related to the level of emotionality, but are a kind of tool in achieving the desired. If screams, crying and aggression disappear at the moment when the baby has received what he wants (toy, sweetness, mother's attention), then manipulation takes place here.

Sometimes hysteria arises, it would seem, because of a trifle, and it is not easy to stop it. The real reasons often lie in the peculiarities of raising a child. You can often encounter cases when children's tantrums, whims become a response to a change in the usual course of events:

The real reasons often lie in the peculiarities of raising a child. You can often encounter cases when children's tantrums, whims become a response to a change in the usual course of events:

- non-compliance with the requirements of the baby by previously trouble-free parents;

- changes in daily routine or habitual environment.

At a young age, it is not easy for parents to cope with such a baby and establish contact, and in kindergarten and school this problem can result in communication difficulties and interfere with concentration on studies.

How can I help my child control his emotions?

Eliminate aggravating factors

The first step towards reducing a child's acute emotional reactions should be the elimination of irritating factors that provoke nervous excitability, tantrums and aggression. What can cause increased emotionality in a child?

- Lack of a unified approach to upbringing, for example: father allows everything, but mother categorically forbids;

- Inconsistency in upbringing: parents are not guided by rules that are understandable to the child, but by a changeable mood;

- Inconsistency of requirements with the child's abilities: school, parents demand more from the child than he can fulfill.

How to help an emotional child?

We are convinced that the problem of the “too emotional child” is not that he shows negative emotions, but that he is unable to express his feelings in the right way. Parents should and can help their children with these simple guidelines:

- Parents often provoke increased emotionality in a child by inconsistency in actions and inconsistency in upbringing. Try to agree, work out the basic rules and principles of education and stick to them;

- Watch not only the behavior of the child, but also control your own, not succumbing to a bad or good mood. For example, if you forbid children from watching cartoons before bed, do not make exceptions even when you are in a good mood. Your behavior should be understandable and predictable;

- Measure your baby's abilities with the requirements for him. If the nervous state is caused by too much work at school, help him cope with them, and ensure proper rest;

Do not forget about proper nutrition and daily routine. A healthy child may respond with a tantrum to the stimulating activity of a chocolate bar before bed or the need to go to bed at the usual time for play.

A healthy child may respond with a tantrum to the stimulating activity of a chocolate bar before bed or the need to go to bed at the usual time for play.

Work with emotional children at the K.O.T.

Often it is impossible to cope with the problem on your own, and the help of specialists is required. In the center of child and youth development K.O.T. we stimulate the harmonious all-round development of children and solve psychological problems. Communication with personal growth coaches and child psychologists can be built in a format that is comfortable for the child and parents:

- Individual conversations with a child psychologist;

- Group courses, where the child is helped not only by trainers, but also by communication with peers with similar problems;

- Personal growth and emotion management training;

- Classes in the art laboratory, helping to relax and concentrate on creativity.

We do not teach a child to cope and suppress emotions. They are given to us by nature and in one form or another always find a way out. The task of parents and psychologists is that the “too emotional child” learns to detect, understand and correctly express the feelings that overwhelm him. This is the fundamental skill of a successful person - to manage their emotions.

They are given to us by nature and in one form or another always find a way out. The task of parents and psychologists is that the “too emotional child” learns to detect, understand and correctly express the feelings that overwhelm him. This is the fundamental skill of a successful person - to manage their emotions.

Thank you for your help in preparing the article child psychologist, author and host of children's programs at the Center for Child and Youth Development "K.O.T." Denis Vizer

The key to raising an emotionally developed child

Irina Balmanji

Over the past decade, scientists have found that success and happiness in all areas of life, including family relationships, is determined by awareness of one's emotions and the ability to cope with one's feelings.

This quality is called "emotional intelligence". From the point of view of education, it means that parents should understand the feelings of their children, be able to sympathize with them, calm them down and gently guide them.

"Emotional educators" teach the child the ability to cope with ups and downs. They allow him to express his negative emotions. They use emotional moments to teach him important life lessons and build a closer relationship with him.

In The Child's Emotional Intelligence, psychologist John Gottman explains what is "normal" and what issues are important at different ages. This information will allow you to better understand the feelings of your children and increase the effectiveness of emotional education.

First months

Child's emotional intelligence

When does a child's emotional relationship with parents begin? Some believe that in the womb, when the child feels her excitement or, conversely, calmness. Others - that immediately after birth, when his parents feed him, rock him to sleep and soothe him. Still others believe that this magical moment occurs a few weeks after birth, when the child for the first time truly smiles at his mother or father.

But most parents would agree that the real fun begins around three months of age, when babies develop an interest in social interaction.

No matter how small a three-month-old child, by observing and imitating, he acquires a huge amount of knowledge how to understand and express emotions. This means that by showing responsiveness and attention, parents can begin an active process of emotional education of their children.

Typically, parents go to great lengths to get and keep their babies' attention in the early stages of emotional communication. For example, parents often use the speech pattern described as "mother language" (although dads can speak it fluently).

It includes raising the voice and slow repeated repetitions, accompanied by exaggerated facial expressions. Such a conversation with a child may seem ridiculous and excessive, but parents use it for a reason - it works! When infants are interacted with in this way, they perk up and pay closer attention to the adult.

Source

Most parents also have non-verbal "talks" with their babies. For example, a child sticks out his tongue - and the mother does the same. The baby coos or gurgles - the mother repeats the sound using the same pitch or rhythm.

Imitative talk is very important because it tells the child that the parent is paying close attention to him and responding to his feelings. At such moments, for the first time, the baby feels that the other person understands him, and this lays the foundation for an emotional connection.

As children learn to recognize and imitate their parents' emotional cues, they also develop another important developmental component: the ability to regulate the physiological arousal that results from social contact. Many psychologists believe that children do this by alternating phases of active communication. For some time they pay close attention to others and respond to their game, and then turn away and ignore any adult attempts to entertain them with toys.

Parents are perplexed by this variability, but there is some evidence that children switch off because they need to. For example, he may feel an increase in heart rate, and this physiological state suppresses him. Therefore, the child averts his eyes, turns his head away and does everything possible to avoid further contact. This is how he learns to calm down.

Advice to those who want to raise a child correctly: pay attention and respond to the baby's moods.

If your child suddenly loses interest in play, give him time to rest. If he starts acting up in a situation where there is a lot of talk around and he is often picked up, take him to a separate room where he can calm down.

If the child cannot calm himself, do everything you can to help him. You have to try and fail until you find the strategy that best suits your child's temperament. Common methods include dimming lights, motion sickness, and gentle conversation.

Those parents who understand that children need to switch from active stimulation to more quiet activities increase the emotional intelligence of their children more effectively.

Parents who help children cope with feelings of discomfort teach them important lessons. Firstly, children learn that their strong negative emotions affect the world around them (parents react to crying), and secondly, that having experienced a strong emotion, you can calm down.

Six to eight months

For babies, this is a period of great exploration, a time when they discover a vast world of objects, people and places. At the same time, they find new ways to express themselves and share feelings such as joy, curiosity, fear, and disappointment with the world around them. This opens up new possibilities for emotional education.

One of the major developmental leaps that usually occurs by six months is the baby's ability to divert attention by keeping in mind an image of an object or person that he is no longer looking at.

In the past, he could only think about the object or person on which his attention was focused. Now he can look at the toy clown with pleasure, and then look at his parents to see if they share his pleasure.

To stimulate the development of emotional intelligence, respond to your child's suggestions to play with objects and imitate his emotional reactions. He will increasingly share his feelings and emotions with you.

Retrieved

By eight months, babies usually begin to crawl and explore their immediate surroundings. They already distinguish between the people they encounter, along with this, the first fears appear. Most likely, it is at this time that you will notice the first cases of "anxiety because of someone else." Just yesterday, the child smiled at strangers at the checkout in the store, and now he hides his face, buried in his mother's shoulder.

Between six and eight months, the baby begins to understand the words you speak much better. And although there are still a few months left before he speaks, the baby already understands a lot and fulfills such requests as: "Go get a polar bear and bring it to me."

All of these new abilities—physical mobility and the ability to switch attention, the child’s special attachment to parents, understanding of spoken language, and fear of the unknown—appear together with a skill that psychologists call “response to social cues”: a child, faced with a certain object or phenomenon, turns to parents for emotional information.

For example, approaching an unfamiliar dog, he may hear his mother say: “No, don’t go there!” He already knows how to understand the combination of the mother's words, her tone of voice and facial expression and concludes that his action is potentially dangerous. Or, heading towards a robot that makes loud noises, he can look back at his mother and see that she is smiling. So the child understands that the robot is safe and can be played with.

Parents occupy a unique place in the child's emotional life: they become a "criterion of his safety", so the child explores the world around him more actively. He knows he can trust parental cues such as facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language.

To strengthen the emotional connection with infants of this age, you must become a mirror for your children, that is, return to them the feelings that they express.

It is equally important to help the child learn the names of his feelings. Watch your child closely and don't forget to say things like, "You're sad (fun, scared, etc. ) right now, aren't you?" or: “You are very tired. Would you like to sit on my lap for a while?" If you correctly recognized his feelings, he will understand you and show it.

) right now, aren't you?" or: “You are very tired. Would you like to sit on my lap for a while?" If you correctly recognized his feelings, he will understand you and show it.

Be prepared that you won't always understand your child, but don't worry, this is normal and fortunately children are very tolerant. Remember that your baby is looking at you and waiting for emotional signals from you.

Nine to twelve months

This is the period when children begin to understand that people can share their thoughts and feelings. For example, handing a broken toy to dad and hearing from him: “Oh, the balloon burst. This is very bad. You're sad, aren't you?" the child realizes that his father knows how he feels.

Now he understands that he and his dad can have the same thoughts and feelings and that he can share them with his parents. This undoubtedly strengthens the emerging emotional bond between parents and the child.

At the same time, the child begins to realize that the people and objects in his life have a certain permanence. For example, a baby understands that if a ball rolls under a chair and is not visible, this does not mean that it does not exist; if mom left the room and does not hear me, she remains a part of my world and will return soon.

For example, a baby understands that if a ball rolls under a chair and is not visible, this does not mean that it does not exist; if mom left the room and does not hear me, she remains a part of my world and will return soon.

An emerging understanding of the permanence of objects and people affects an important aspect of your child's development: his growing attachment to specific people, namely his parents. Now that he is sure that his parents exist, even if they are not around, he can miss them and demand that they stay.

The child may start crying and screaming a lot if he sees that you, for example, put on a coat and are about to leave. When you leave, he feels that you must be somewhere, but he doesn't know exactly where, and this can upset him. In addition, children at this age still have a poorly developed sense of time, so it is difficult for a child to understand how long you will be gone.

Retrieved

You can help a child of this age cope with the anxiety he feels about leaving you by simply assuring him that you will return when you are about to leave. Remember: a one-year-old baby, although not yet able to speak, already understands a lot, so your assurances can help him.

Remember: a one-year-old baby, although not yet able to speak, already understands a lot, so your assurances can help him.

Don't forget that he is watching your emotions, so if you are anxious or afraid to leave him, he can pick up your feelings and feel the same way.

You can also teach your child to be away from you. To do this, allow him to explore the premises of your house on his own. For example, if he crawls into another (safe from your point of view) room, do not immediately run to see what is happening there, let him be alone.

If you are in one room and need to go to another, tell your child where you are going and that you will be back very soon. Gradually, he must understand that his parents can leave, that nothing terrible will happen, and if they say they will return, they can be trusted.

Remember to constantly show your child that you understand his feelings. This way you make him feel safe and strengthen the emotional connection.

Toddler (1 to 3)

Toddler is a fun and exciting time when your child develops a sense of self and starts to be independent. But this period is also called the two-year crisis: children become much more confident in themselves and begin to contradict you.

But this period is also called the two-year crisis: children become much more confident in themselves and begin to contradict you.

At this time, their speech skills are actively developing, but the words you will most often hear are “No!”, “Mine!”, “I myself!” or "I will!" At this time, emotional education becomes an important tool with which parents can help the baby cope with the emerging feelings of disappointment and anger.

As with all stages of development, parents need to look at conflicts and problems from the child's point of view. The main task of the development of the baby at this age is to assert himself as an independent being, so try to avoid situations that will make him feel that he has no power and no control.

At this age, children should be given the opportunity to make a choice several times a day.

Instead of saying, "It's cold outside, you should put on your coat," say, "What would you like to wear today? Jacket or sweater? Set boundaries so that your baby is safe and you are calm.

Simultaneously with self-affirmation, babies become more and more interested in other children. Toddlers older than a year old may be very attracted to each other, but they do not yet have the necessary social skills to play well together. Attempts to play together are often problematic given the "baby ownership rules" which state: 1) if I see it, it's mine; 2) if it's yours and I want it, then it's mine and 3) if it's mine, then it's mine forever.

Parents should understand that this is not greed, but an expression of the baby's developing sense of self. Children of this age can only consider their own point of view and do not understand that others may think differently. So the idea of having to share just doesn't make sense to them.

Source

There is a positive side to toddler conflicts over toys and the emotional fireworks they usually lead to. Episodes like this offer amazing opportunities for emotional upbringing.

You can help your child recognize and verbalize anger or frustration. (“You go crazy when someone takes your doll,” or “You are frustrated that you can’t get that ball right now.”) You can then work with your child to look for ways to solve the problem (for example, introduce him to the idea of playing queues).

(“You go crazy when someone takes your doll,” or “You are frustrated that you can’t get that ball right now.”) You can then work with your child to look for ways to solve the problem (for example, introduce him to the idea of playing queues).

At the same time, it is important to set limits on inappropriate behavior. If the conflict escalates into a fight, the fighter can be told that "we don't hit or hurt our buddies because we're angry" and then sympathize with the victim and reassure her.

Remember to praise and reward your baby every time he makes even the slightest attempt at an exchange, but especially don't expect him to do it often. At this age, as a rule, parallel games are more successful, where each child has his own space and can play separately from other children.

You can never completely avoid toddler conflicts over toys. But for the sake of peace of mind, you can keep these episodes to a minimum. Explain to your children that they can take toys to a friend or kindergarten only if they share them.

If your baby is waiting for friends at home, take with him some toys that are especially dear to him, which he does not want to give to others. Then, before the guest arrives, solemnly hide them. This will give the child a sense of power and control that he aspires to.

Preschool (from four to seven years old)

By the age of four, children are already "on you" with the world around them. They meet new friends, actively explore the environment and learn a lot of new and interesting things.

With experience comes new challenges: Kindergarten is fun, but caregivers generally expect the child to sit quietly in the group and focus on the task. The child already knows how to behave with friends, but sometimes they still drive him crazy and hurt his feelings. And now, when he is old enough to understand the horrors of fire, war, robbers and death, he tries his best not to be crushed by fear of these events.

To cope with new problems, the child needs to be able to manage his emotions. One of the most important tasks that children face at this age is the need to learn how to suppress inappropriate behavior, focus and motivate themselves to achieve a goal.

One of the most important tasks that children face at this age is the need to learn how to suppress inappropriate behavior, focus and motivate themselves to achieve a goal.

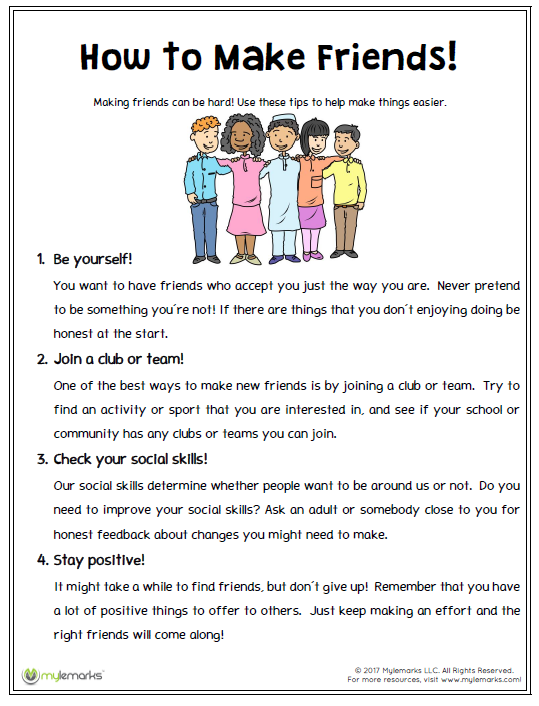

Nowhere do children develop the skills to manage their emotions as well as in relationships with peers. It is here that they learn to accurately formulate their thoughts in order to exchange information, and to clarify them if others do not understand them. They learn to speak and play in turn, to share. They learn how to find a common language during the game, to enter into conflicts and resolve them, how to understand the feelings, desires and aspirations of other people.

Friendship is a fertile ground for the emotional development of babies, so give your children more opportunities to connect with friends one on one.

Retrieved

Play activities for children of this age are best done in pairs. This is because children between the ages of four and seven often find it difficult to figure out how to manage relationships with more than one person at the same time.

As a parent, this can be frustrating, especially if you see two children rejecting a third who tries to join the game. But you must understand that rejection does not necessarily mean ill will.

It's just that the kids want to protect the game they've created as a couple, and because they can't put their feelings into words that a third child can understand and accept ("I'm sorry, Billy, but a couple is the biggest social unit we can cope at this stage of their development”), they tend to resort to more rude and harsh tactics: “Go away, Billy. We don't play with you!"

Some children may do the same to their parents, saying, “Go away, dad! I do not love you anymore. I love only my mother!” In fact, this means that he enjoys the closeness that he currently has with his mother. Dad shouldn't take this rudeness to heart.

In fact, young children can be very fickle. It is not uncommon for two children to reject a third, and a few minutes later regroup and invite the newly rejected child to join in their new game.

What is the best way to react if you see that your child is excluding a third person from the game? If you want to instill in him kindness and sensitivity to the feelings of other people, then you should tell him how to manage your social relations as politely as possible. Teach your child simple words he can use to explain the situation. For example: “Now I only want to play with someone. But then I can play with you."

If your child is the one currently expelled, it is important that you acknowledge their feelings, especially if they are upset or angry about the situation. Then help him think of ways to solve the problem, such as inviting another child to play or finding something fun to do alone.

In addition to teaching important social skills, friendship between young children gives them the opportunity to fantasize: create characters and act out life situations.

Young friends often use fantasies to help each other work through complicated problems and cope with experiences from everyday life. This contributes to their emotional development, helping to access hidden feelings.

This contributes to their emotional development, helping to access hidden feelings.

Knowing that fantasy can open the door to a young child's thoughts and concerns, parents of children of this age involved in emotional education can use games.

Children usually project their ideas, wishes, frustrations and fears onto dolls. Parents can encourage the child to explore their feelings and convince him of something, simply by responding to the words of the toy. Here is an example of such a conversation.

Child: This bear is an orphan because his parents no longer need him.

Papa: Are mama and papa bear gone?

Child: Yes, they are gone.

Dad: Will they come back?

Child: Never.

Dad: Why did they leave?

Child: The bear was bad.

Dad: What did he do?

Child: He got angry with the mother bear.

Dad: I think it's okay to get angry sometimes. She will be back.

Child: Yes. She's already on her way.

Dad (takes another bear and speaks in the voice of a mother bear): I went to take out the garbage. I'm already back.

Child: Hello, Mom!

Dad: You were crazy, and that's okay. Sometimes I go crazy too.

Child: I know that.

Source

Another example. Your child wants to be bigger and stronger, so he says: “I used to be small, but now I can lift the crib from one side. Do you know that Superman can even fly?" This means that the child practically asked permission to become Superman in order to explore feelings such as strength and self-confidence. You can contribute and encourage his fantasy by simply saying, “Nice to meet you, Superman. Are you going to fly right now?"

Children can incorporate real-life situations into their play. Don't be surprised if, in the midst of playing with a Barbie doll or imitating superheroes, your child suddenly says: "I'm afraid to stay with this nanny again" or: "How old will I be when I die?"

The origin of children's ideas will most likely remain a mystery to you, but one thing is clear - something in the game scenario stirred up the child's emotions, and he wants to share them. The intimacy and spontaneity of the game allows him to feel safe next to you and raise one or another delicate issue to the surface.

The intimacy and spontaneity of the game allows him to feel safe next to you and raise one or another delicate issue to the surface.

If the child pauses the play in order to explore the emotion, then you should also pause the play and talk to him about the fear involved.

When talking to your children about their fears, remember to use basic emotional education techniques: help them recognize and label their fear when it comes up, talk about it empathetically and sensitively, and come up with ways to deal with various threats together.

For example, if your child is afraid of fire, say, “House fire is really scary. That's why we have a smoke detector that will alert us if something catches fire."

Primary school age (eight to twelve years old)

At this time, children begin to enter into large social groups and fall under their influence. Now they notice which peers are in and who are not in the group. At this age, children actively develop cognitive abilities and they learn about the power of intellect over emotions.

Your child is becoming more and more influenced by peers, and you may notice that one of the main motivations of his life is the desire to avoid awkwardness at all costs.

Children of this age begin to worry about the style of their clothes, the type of backpack, and how their peers feel about what they are doing. The child will go to any lengths not to draw attention to himself, especially if his friends tease him or criticize his actions.

Source

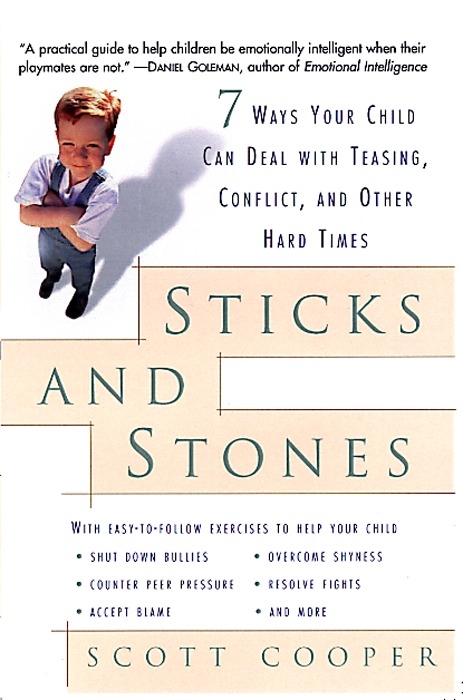

Conformity at this age is quite healthy, although it often irritates parents who want their children to be leaders, not performers. It means that your child is getting better at recognizing social cues and acquiring a skill that will serve him throughout his life. Between eight and twelve, this is especially important because children in this age group can tease and humiliate mercilessly.

Children quickly learn that if they are teased, it is best not to react emotionally at all. Protesting, yelling, complaining to a teacher, or getting angry when a hat is stolen or called names can lead to further humiliation or expulsion from the group. Therefore, in order to maintain dignity, it is better to turn the other cheek.

Protesting, yelling, complaining to a teacher, or getting angry when a hat is stolen or called names can lead to further humiliation or expulsion from the group. Therefore, in order to maintain dignity, it is better to turn the other cheek.

Understanding the situation, children perform an "ectomy of emotions", removing feelings from the sphere of relationships with peers. Most children master this skill, but those who learn to control their emotions at an early age achieve the greatest success.

A "cold-blooded" attitude towards peer relationships can mislead parents who were good emotional educators.

Mothers and fathers often mistakenly believe that all their children need to do in case of conflict with peers is to share their feelings with another child and come to an agreement. This strategy works well in preschool, but in school, when showing emotion is considered a social nuisance, it can end in disaster.

Children who have been emotionally trained become perceptive enough to understand this. They are able to recognize the signals of their peers and act accordingly.

They are able to recognize the signals of their peers and act accordingly.

Closer to the age of ten, many children become much more capable of logical reasoning. They often react as if they don't have heads, but computers. Tell a nine-year-old child to "pick up your socks" - and he can pick them up, and then put them back, explaining this by saying that he "was not told to put them away."

Insolence and mockery of the adult world are characteristic of children who see life in black and white or divide everything into right and wrong. Think about it: a ten-year-old child suddenly becomes aware of all the arbitrary and illogical standards of life, and life begins to seem crazy to him. He considers adults to be hypocrites.

At this age, your child is concerned about morality and justice, so he can come up with "pure worlds" for himself, where all people are equal, there is no place for war and where there can be no tyranny. The child may begin to despise the adult world with its atrocities. He doubts, he challenges, he starts to think for himself.

He doubts, he challenges, he starts to think for himself.

The irony is that at the same time the child adheres to the unreasonable and tyrannical standards of his peer group. For example, your daughter may stand up for the human right to freedom of expression and at the same time limit her wardrobe to one style of sweater. She may be deeply concerned about animal cruelty and at the same time take part in a conspiracy to keep a classmate out of a basketball game.

How should parents respond to such inconsistency? Pay no attention and consider this time as a period of research. Know that strict adherence to the often arbitrary rules dictated by peers is part of normal and healthy development. Your child's behavior means that he is able to recognize the standards and values accepted in the peer group, and this allows him to become part of it.

If you find out that your child is involved in the bullying of another child, which you consider unfair, tell him how you feel. Use this precedent to convey to him your values of kindness and honesty. If your child has not shown cruelty, you should not be especially harsh or severely punish him.

Use this precedent to convey to him your values of kindness and honesty. If your child has not shown cruelty, you should not be especially harsh or severely punish him.

If your child is complaining about being excluded from a group or being treated unfairly by peers, you can use emotional coaching techniques to help them deal with feelings of sadness and anger. After overcoming negative emotions, try to look for a solution to the problem together. For example, you can explore the ways in which a person creates and maintains friendships.

Do not try to prove to your child that his desire to dress and act like other children is stupid. Recognize his desire to be accepted by his peers and help him achieve this.

If your child makes fun of the rules of the adult world, don't take that criticism to heart. Brashness, sarcasm, and contempt for adult values are normal behavior at this age.

If your child is really rude to you, tell him about it, but in a special way. (“When you laugh at my hair, I feel that you do not respect me.”) This way you can instill in him such values as kindness and mutual respect in the family. Frondering notwithstanding, children at this age, like everyone else, want to feel emotionally connected to their parents and need their loving guidance.

(“When you laugh at my hair, I feel that you do not respect me.”) This way you can instill in him such values as kindness and mutual respect in the family. Frondering notwithstanding, children at this age, like everyone else, want to feel emotionally connected to their parents and need their loving guidance.

Adolescence

In adolescence, children are concerned with the question of self-identification: who am I? who am I becoming? who am I supposed to be? Therefore, do not be surprised if at some point your child loses interest in family affairs, and relationships with friends come to the fore. In the end, it is through friendship outside the usual boundaries of the house that he finds out who he is.

The path of self-exploration is not always smooth. Hormonal changes can cause uncontrolled and drastic mood changes. At this age, children are very vulnerable and exposed to many dangers. But since this is a natural and inevitable part of human development, the study continues.

One of the major challenges adolescents face in their research is the integration of mind and emotions. If the rational character of Star Trek, Mr. Spock, can serve as a symbol of children of primary school age, then Captain Kirk in the role of commander of the starship Enterprise can be a symbol of teenagers. Kirk is constantly faced with situations where his very sensitive, human side is opposed to logic and experience.

Most often, adolescents face a similar situation in matters of sexuality and self-esteem. A girl is attracted to a boy whom she doesn't really respect. (“He’s so cute. Unfortunately, as soon as he opens his mouth, he ruins everything.”) And the boy catches himself expressing an opinion that he protested against when he heard it from his father. (“I can’t believe it! I talk just like my dad!”)

Suddenly a teenager realizes that the world is not only black and white, that it consists of many shades of gray.

Adolescence is a difficult period for both a child who is looking for his own way, and for his parents. Now your child is forced to do most of the research without you.

Now your child is forced to do most of the research without you.

Source

Social educator Michael Riera writes: “Until now, you have played the role of a manager in a child’s life: arranging trips and visits to doctors, scheduling extracurricular activities and weekends, helping with and checking homework. He told you about school life, and you were usually the first person he approached with "important" questions. And suddenly, without warning or explanation, you were dismissed from your position. Now, if you want to continue to have a meaningful impact, you have to fight, develop new strategies and put in a lot of effort to get hired again, but already as a consultant.”

How should you play the role of consultant? How can you stay close enough to be an emotional nurturer and still allow your child to develop independently as a fully-fledged adult needs? Here are some tips.

1. Recognize that adolescence is a time when children move away from their parents. Parents need to understand that teenagers need privacy. Eavesdropping on conversations, reading a diary, or too many leading questions sends the message to your child that you don't trust him and creates a barrier to communication.

Parents need to understand that teenagers need privacy. Eavesdropping on conversations, reading a diary, or too many leading questions sends the message to your child that you don't trust him and creates a barrier to communication.

As well as respecting your child's privacy, you must respect the child's right to feel anxious and dissatisfied from time to time. Give your child space to experience deep feelings, let him feel sad, angry, anxious, or discouraged, and don't ask questions like "What's wrong with you?" because they imply that you don't approve of his emotions.

There is another danger: if a teenager suddenly opens his heart to you, try not to show that you instantly understood everything. Your child has encountered a problem for the first time, it seems to him that his experience is unique, and if adults show that they are well aware of the motives of his behavior, the child feels offended. So take the time to listen and hear your teenager. Do not assume that you already know and understand everything he wants to say.

Adolescence is also a time when individuality develops. Your child may choose a style of clothing, hairstyle, music, art and language that you do not like, so always remember that you do not need to approve his choice, you just need to accept it.

2. Be respectful. Imagine for a moment that your best friend began to treat you the way many parents treat their children. How do you feel when you are constantly corrected, reminded of shortcomings, or teased about the most sensitive topics? What should you do if your friend gives you long-winded lectures and explains with condemnation what and how you should do with your life? Most likely, you will decide that this person does not respect you too much and does not care about your feelings.

Of course, you shouldn't treat teenagers as friends (child-parent relationships are much more complicated), but your children certainly deserve as much respect as your buddies. So don't tease, criticize or hurt your children. Communicate your values concisely and without judgment.

Communicate your values concisely and without judgment.

If you have conflicts about your child's behavior, don't label them with common labels (lazy, greedy, careless, selfish). Speak in terms of specific actions. For example, tell him how his actions affected you. (“You hurt me a lot when you leave without washing the dishes because I have to do your job.”)

3. Encourage independent decision making and continue to be your child's emotional educator . Choosing the right degree of participation in a teenager's life is one of the most difficult tasks that parents face.

A teenager should say more often: “The choice is yours”, express confidence in the correctness of his judgments and try not to show hidden resistance under the guise of warning a possible unfavorable outcome of the case.

You should encourage his independence and from time to time allow the teenager to make unwise (but not dangerous) decisions.

Remember that a teenager can learn not only from his successes, but also from his mistakes.