Linguistic development in children

Language development: children 0-8 years

Language development in children: what you need to know

Language development is an important part of child development.

It supports your child’s ability to communicate. It also supports your child’s ability to:

- express and understand feelings

- think and learn

- solve problems

- develop and maintain relationships.

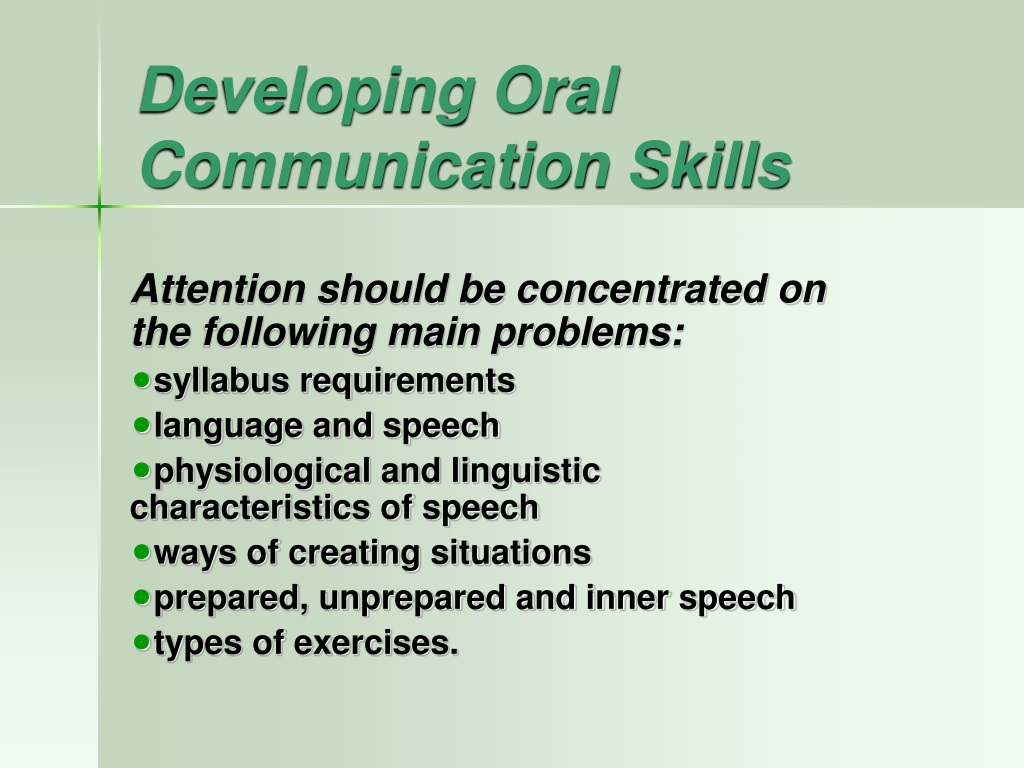

Learning to understand, use and enjoy language is the first step in literacy, and the basis for learning to read and write.

In their first few years, children develop many of the oral language skills that help them to learn to read when they go to school. And they keep developing language skills throughout childhood and adolescence.

How to encourage early language development in children

The best way to encourage your child’s language development is to do a lot of talking together about things that interest your child. It’s all about following your child’s lead as they show you what they’re interested in by waving, babbling or using words.

Talking with your child

From birth, talk with your child and treat them as a talker. The key is to use many different words in different contexts. For example, you can talk to your child about an orange ball and about cutting up an orange for lunch. This helps your child learn what words mean and how words work.

When you finish talking, pause and give your child a turn to respond.

As your child starts coo, gurgle, wave and point, you can respond to your child’s attempts to communicate. For example, if your baby coos and gurgles, you can coo back to them. Or if your toddler points to a toy, respond as if your child is saying, ‘Can I have that?’ For example, you could say ‘Do you want the block?’

When your child starts using words, you can repeat and build on what your child says. For example, if your child says, ‘Apple,’ you can say, ‘You want a red apple?’

For example, if your child says, ‘Apple,’ you can say, ‘You want a red apple?’

And it’s the same when your child starts making sentences. You can respond and encourage your child to expand their sentences. For example, your toddler might say ‘I go shop’. You might respond, ‘And what did you do at the shop?’

When you pay attention and respond to your child in these ways, it encourages them to keep communicating and developing their language skills.

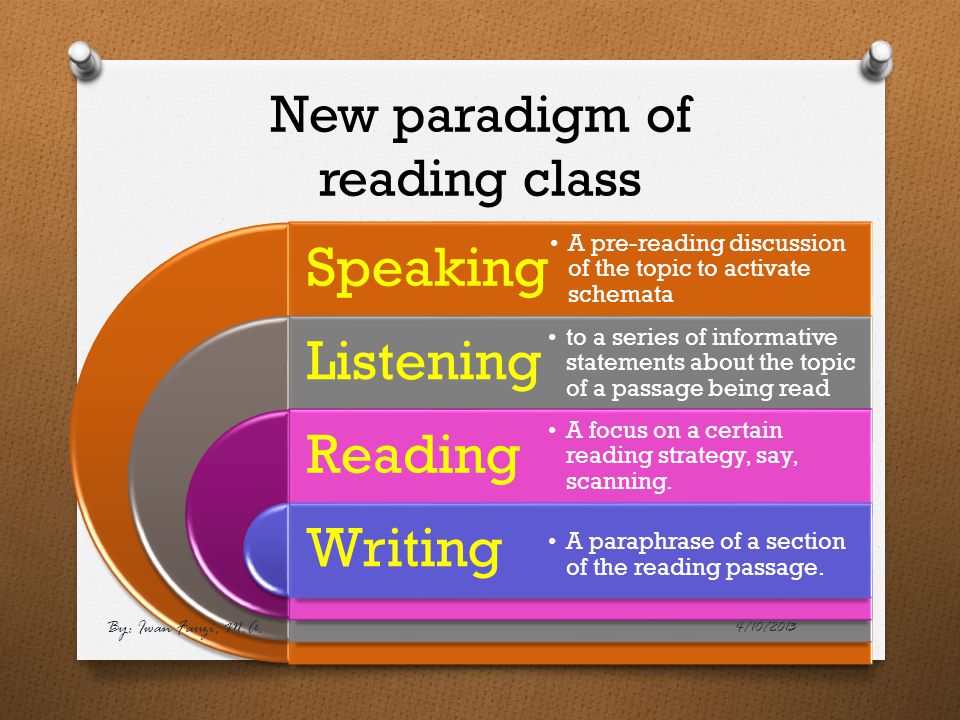

Reading with your child

Reading and sharing books about plenty of different topics lets your child hear words used in many different ways.

Linking what’s in the book to what’s happening in your child’s life is a good way to get your child talking. For example, you could say, ‘We went to the playground today, just like the boy in this book. What do you like to do at the playground?’ You can also encourage talking by chatting about interesting pictures in the books you read with your child.

When you read aloud with your child, you can point to words as you say them. This shows your child the link between spoken and written words, and helps your child learn that words are distinct parts of language. These are important concepts for developing literacy.

This shows your child the link between spoken and written words, and helps your child learn that words are distinct parts of language. These are important concepts for developing literacy.

Your local library or mobile library is a great source of books.

If your family speaks two languages, you can encourage your child’s language development in both languages – for example, English and Spanish. Bilingual children often have language skills similar to their peers by the time they’re in primary school.

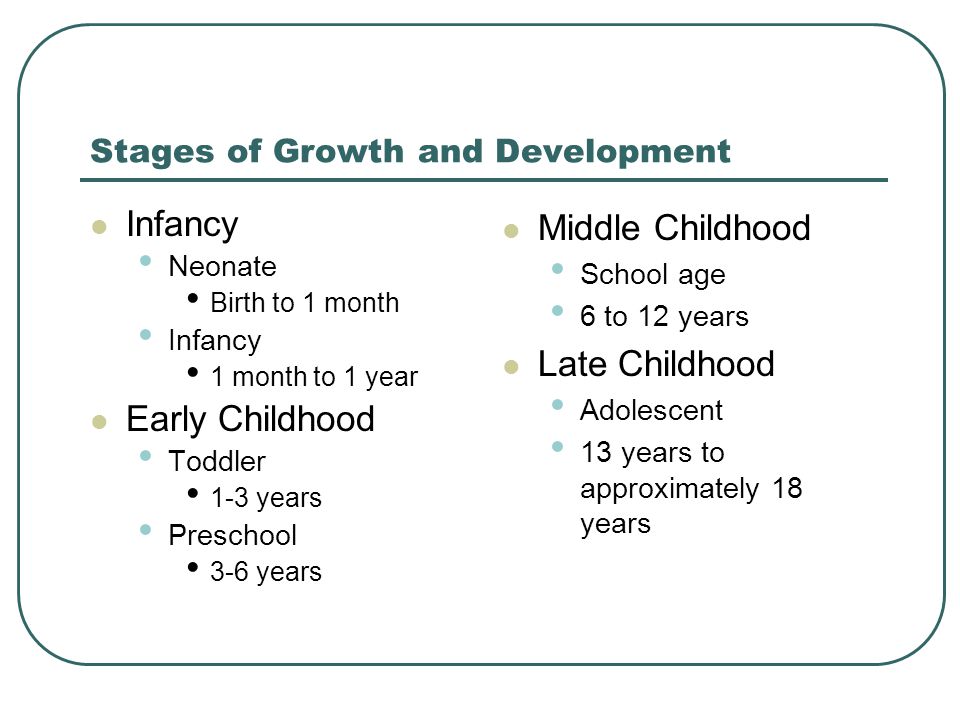

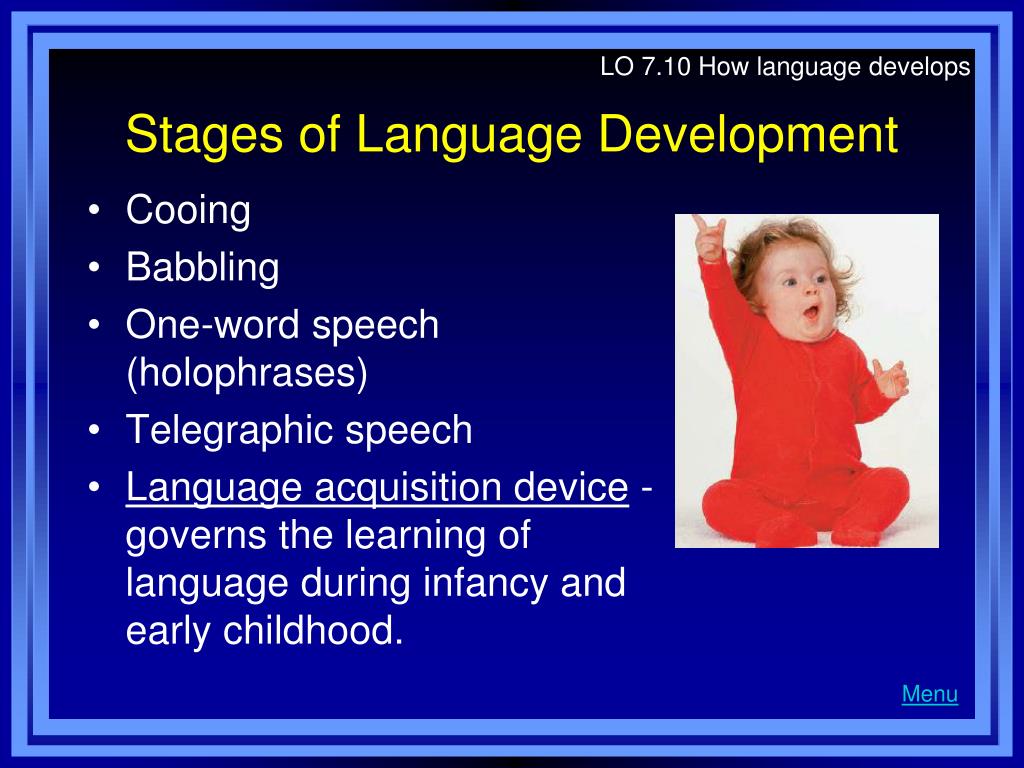

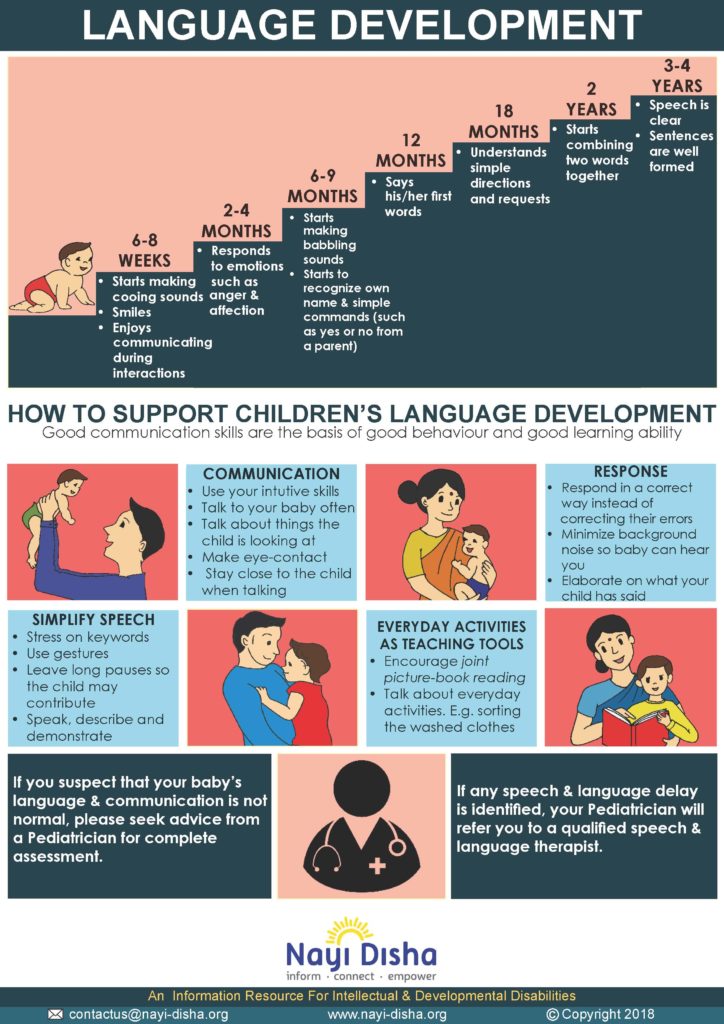

Language development: the first eight years

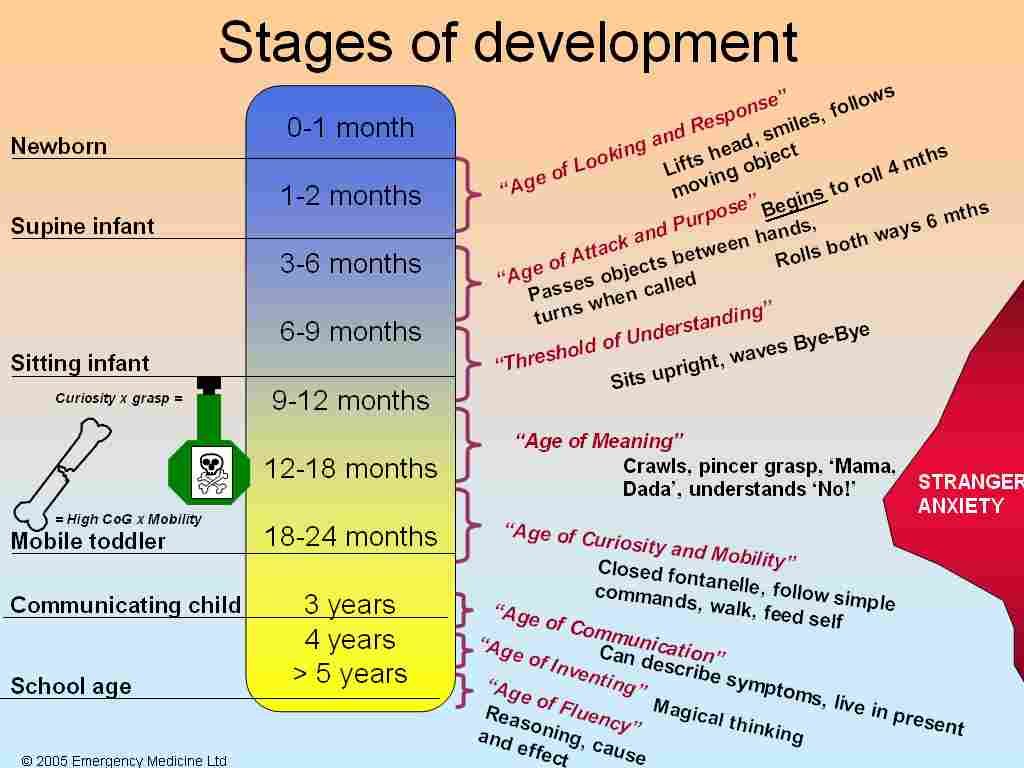

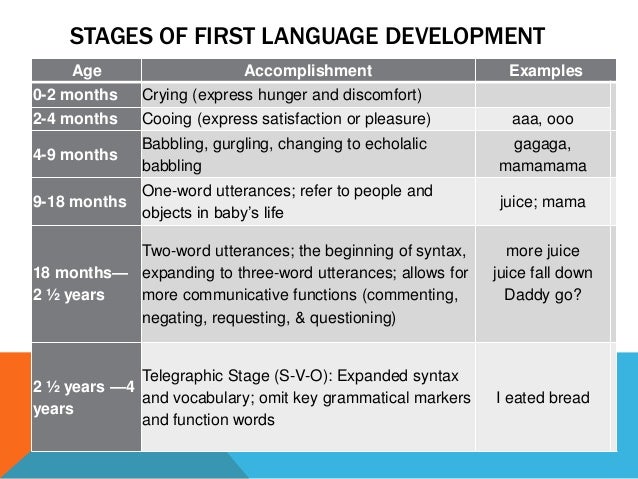

Here are just a few of the important things your child might achieve in language development between three months and eight years.

3-12 months

At three months, your baby will most likely coo, smile and laugh. As they grow, your baby will begin to play with sounds and communicate with gestures like waving and pointing.

At around 4-6 months, your baby will probably start babbling. Baby will make single-syllable sounds like ‘ba’ first, before repeating them – ‘ba ba ba’.

Babbling is followed by the ‘jargon phase’ where your child might sound like they’re telling you something, but their ‘speech’ won’t sound like recognisable words. First words with meaning often start at around 12 months or so.

If your baby isn’t babbling and isn’t using gestures by 12 months, talk to your GP or child and family health nurse.

Find out more about language development from 3-12 months.

12-18 months

At this age, children often say their first words with meaning. For example, when your child says ‘Dada’, your child is actually calling for dad. In the next few months, your child’s vocabulary will grow. Your child can understand more than they can say. They can also follow simple instructions like ‘Sit down’.

18 months to 2 years

Most children will start to put two words together into short ‘sentences’. Your child will understand much of what you say, and you can understand most of what your child says to you. Unfamiliar people will understand about half of what your child says.

Unfamiliar people will understand about half of what your child says.

If your child doesn’t have some words by around 18 months, talk to your GP or child and family health nurse or another health professional.

Find out more about language development from 1-2 years.

2-3 years

Your child most likely speaks in sentences of 3-4 words and is getting better at saying words correctly. Your child might play and talk at the same time. Strangers can probably understand about three-quarters of what your child says by the time your child is three.

Find out more about language development from 2-3 years.

3-5 years

You can expect longer, more complex conversations about your child’s thoughts and feelings. Your child might also ask about things, people and places that aren’t in front of them. For example, ‘Is it raining at grandma’s house, too?’

Your child will probably also want to talk about a wide range of topics, and their vocabulary will keep growing. Your child might show understanding of basic grammar and start using sentences with words like ‘because’, ‘if’, ‘so’ or ‘when’. And you can look forward to some entertaining stories too.

Your child might show understanding of basic grammar and start using sentences with words like ‘because’, ‘if’, ‘so’ or ‘when’. And you can look forward to some entertaining stories too.

Find out more about language development from 3-4 years and language development from 4-5 years.

5-8 years

During the early school years, your child will learn more words and start to understand how the sounds within language work together. Your child will also become a better storyteller, as they learn to put words together in different ways and build different types of sentences. These skills also let your child share ideas and opinions. By eight years, your child will be able to have adult-like conversations.

Find out more about language development from 5-8 years.

When to get help for language development

You know your child best. If you have any concerns about your child’s language development, ask your child and family health nurse, GP or paediatrician. They might refer you to a speech pathologist.

They might refer you to a speech pathologist.

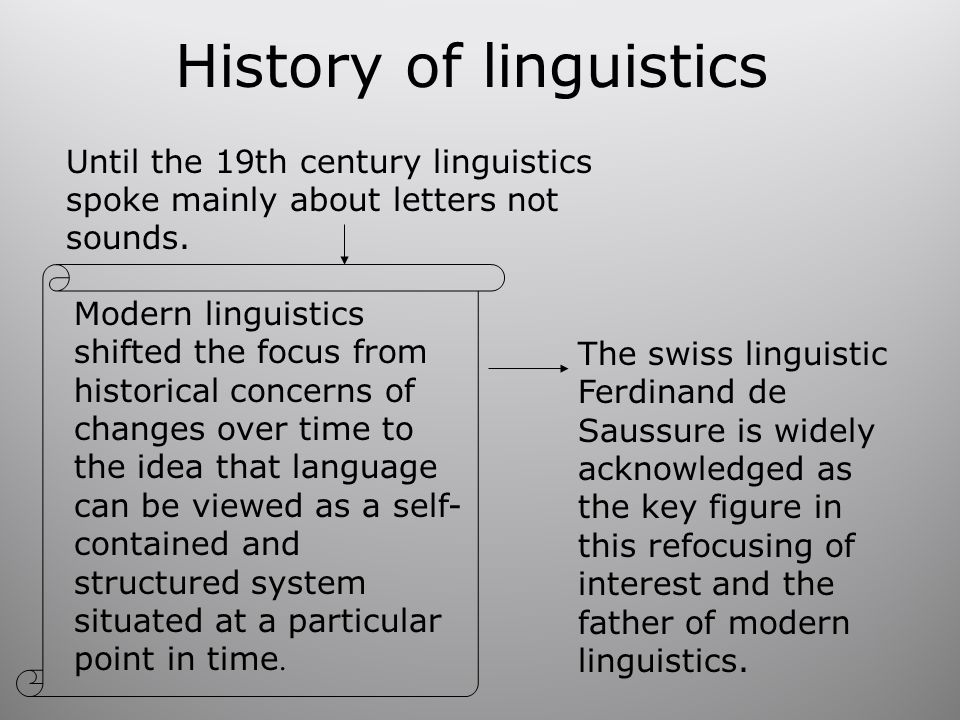

Speech and Language Developmental Milestones

How do speech and language develop?

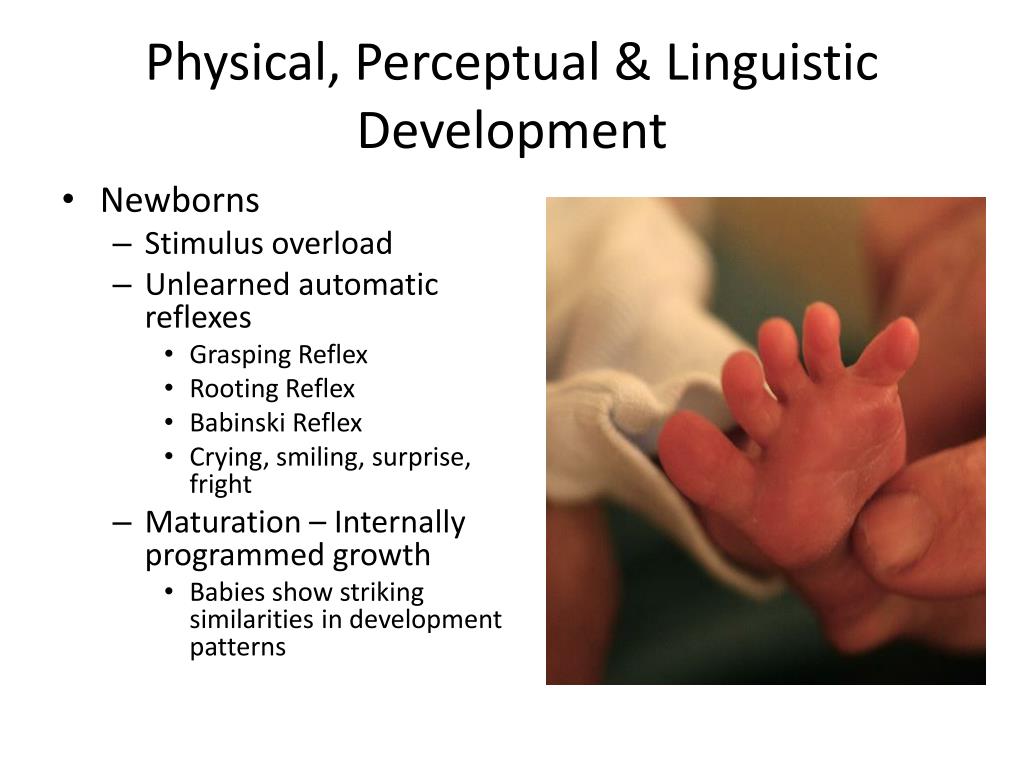

The first 3 years of life, when the brain is developing and maturing, is the most intensive period for acquiring speech and language skills. These skills develop best in a world that is rich with sounds, sights, and consistent exposure to the speech and language of others.

There appear to be critical periods for speech and language development in infants and young children when the brain is best able to absorb language. If these critical periods are allowed to pass without exposure to language, it will be more difficult to learn.

What are the milestones for speech and language development?

The first signs of communication occur when an infant learns that a cry will bring food, comfort, and companionship. Newborns also begin to recognize important sounds in their environment, such as the voice of their mother or primary caretaker. As they grow, babies begin to sort out the speech sounds that compose the words of their language. By 6 months of age, most babies recognize the basic sounds of their native language.

As they grow, babies begin to sort out the speech sounds that compose the words of their language. By 6 months of age, most babies recognize the basic sounds of their native language.

Children vary in their development of speech and language skills. However, they follow a natural progression or timetable for mastering the skills of language. A checklist of milestones for the normal development of speech and language skills in children from birth to 5 years of age is included below. These milestones help doctors and other health professionals determine if a child is on track or if he or she may need extra help. Sometimes a delay may be caused by hearing loss, while other times it may be due to a speech or language disorder.

What is the difference between a speech disorder and a language disorder?

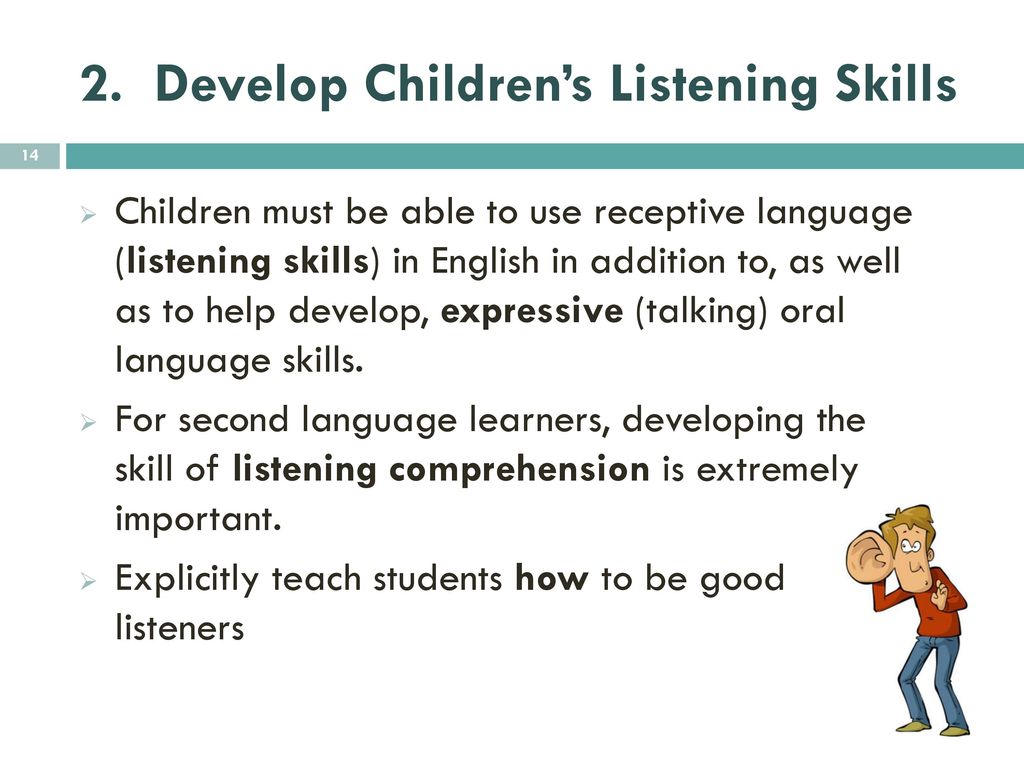

Children who have trouble understanding what others say (receptive language) or difficulty sharing their thoughts (expressive language) may have a language disorder. Developmental language disorder (DLD) is a language disorder that delays the mastery of language skills. Some children with DLD may not begin to talk until their third or fourth year.

Some children with DLD may not begin to talk until their third or fourth year.

Children who have trouble producing speech sounds correctly or who hesitate or stutter when talking may have a speech disorder. Apraxia of speech is a speech disorder that makes it difficult to put sounds and syllables together in the correct order to form words.

What should I do if my child’s speech or language appears to be delayed?

Talk to your child’s doctor if you have any concerns. Your doctor may refer you to a speech-language pathologist, who is a health professional trained to evaluate and treat people with speech or language disorders. The speech-language pathologist will talk to you about your child’s communication and general development. He or she will also use special spoken tests to evaluate your child. A hearing test is often included in the evaluation because a hearing problem can affect speech and language development. Depending on the result of the evaluation, the speech-language pathologist may suggest activities you can do at home to stimulate your child’s development. They might also recommend group or individual therapy or suggest further evaluation by an audiologist (a health care professional trained to identify and measure hearing loss), or a developmental psychologist (a health care professional with special expertise in the psychological development of infants and children).

They might also recommend group or individual therapy or suggest further evaluation by an audiologist (a health care professional trained to identify and measure hearing loss), or a developmental psychologist (a health care professional with special expertise in the psychological development of infants and children).

What research is being conducted on developmental speech and language problems?

The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) sponsors a broad range of research to better understand the development of speech and language disorders, improve diagnostic capabilities, and fine-tune more effective treatments. An ongoing area of study is the search for better ways to diagnose and differentiate among the various types of speech delay. A large study following approximately 4,000 children is gathering data as the children grow to establish reliable signs and symptoms for specific speech disorders, which can then be used to develop accurate diagnostic tests. Additional genetic studies are looking for matches between different genetic variations and specific speech deficits.

Additional genetic studies are looking for matches between different genetic variations and specific speech deficits.

Researchers sponsored by the NIDCD have discovered one genetic variant, in particular, that is linked to developmental language disorder (DLD), a disorder that delays children’s use of words and slows their mastery of language skills throughout their school years. The finding is the first to tie the presence of a distinct genetic mutation to any kind of inherited language impairment. Further research is exploring the role this genetic variant may also play in dyslexia, autism, and speech-sound disorders.

A long-term study looking at how deafness impacts the brain is exploring how the brain “rewires” itself to accommodate deafness. So far, the research has shown that adults who are deaf react faster and more accurately than hearing adults when they observe objects in motion. This ongoing research continues to explore the concept of “brain plasticity”—the ways in which the brain is influenced by health conditions or life experiences—and how it can be used to develop learning strategies that encourage healthy language and speech development in early childhood.

A recent workshop convened by the NIDCD drew together a group of experts to explore issues related to a subgroup of children with autism spectrum disorders who do not have functional verbal language by the age of 5. Because these children are so different from one another, with no set of defining characteristics or patterns of cognitive strengths or weaknesses, development of standard assessment tests or effective treatments has been difficult. The workshop featured a series of presentations to familiarize participants with the challenges facing these children and helped them to identify a number of research gaps and opportunities that could be addressed in future research studies.

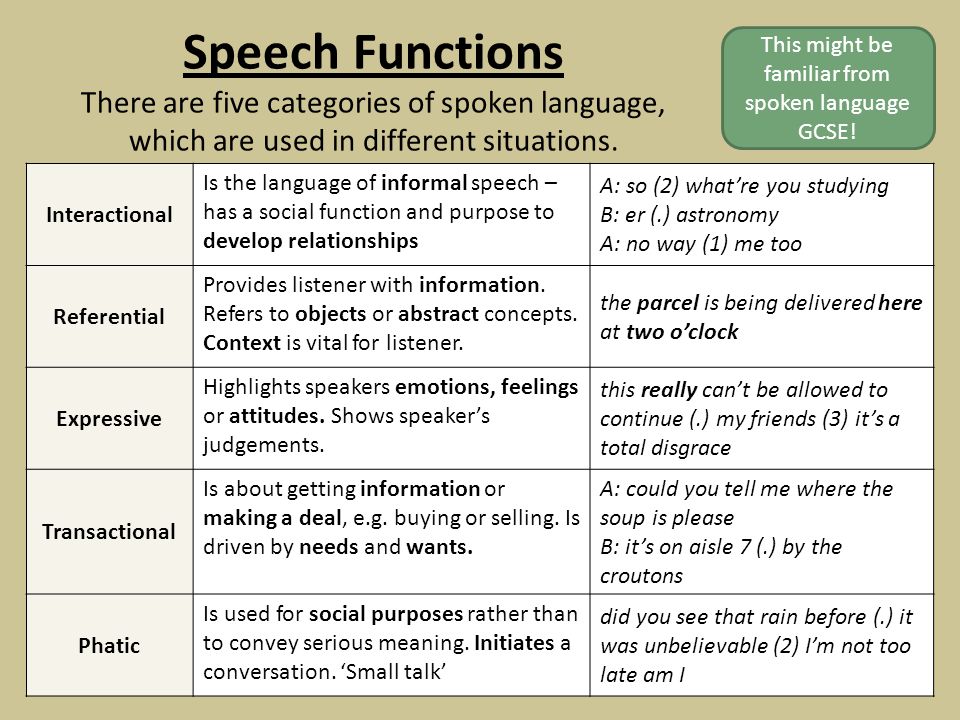

What are voice, speech, and language?

Voice, speech, and language are the tools we use to communicate with each other.

Voice is the sound we make as air from our lungs is pushed between vocal folds in our larynx, causing them to vibrate.

Speech is talking, which is one way to express language. It involves the precisely coordinated muscle actions of the tongue, lips, jaw, and vocal tract to produce the recognizable sounds that make up language.

It involves the precisely coordinated muscle actions of the tongue, lips, jaw, and vocal tract to produce the recognizable sounds that make up language.

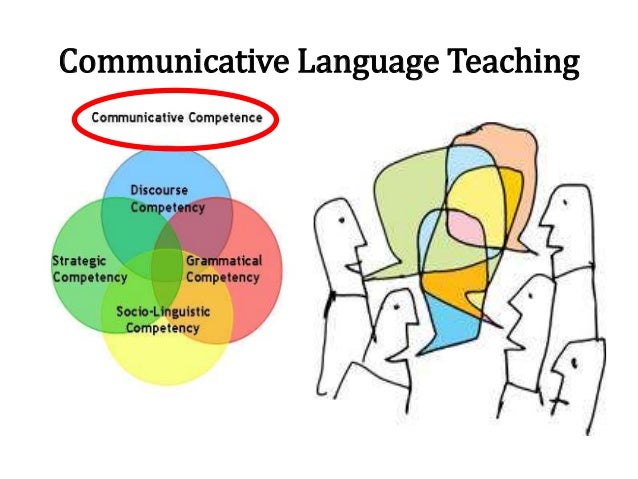

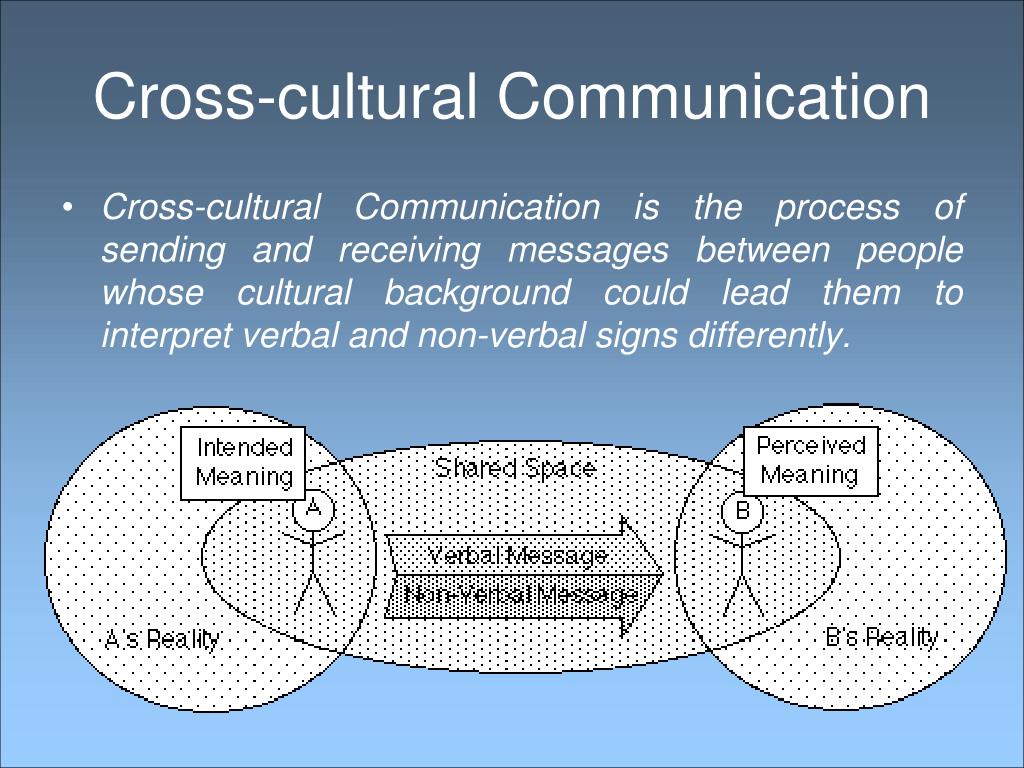

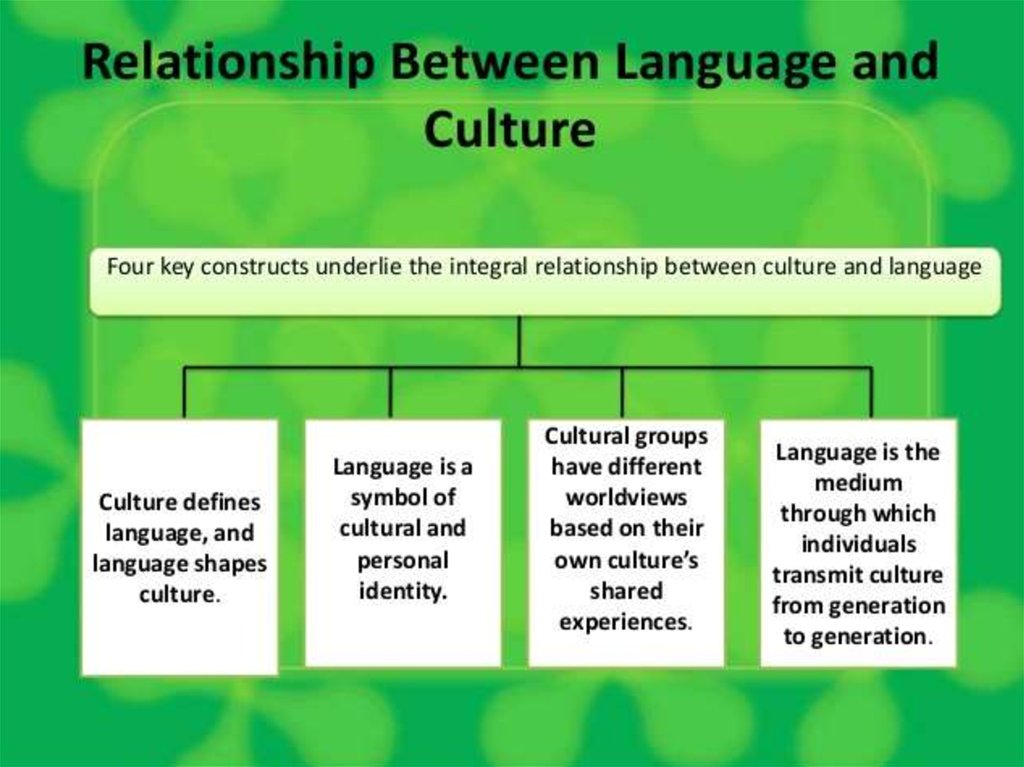

Language is a set of shared rules that allow people to express their ideas in a meaningful way. Language may be expressed verbally or by writing, signing, or making other gestures, such as eye blinking or mouth movements.

Your baby’s hearing and communicative development checklist

Birth to 3 Months

Reacts to loud sounds

YES NO

Calms down or smiles when spoken to

YES NO

Recognizes your voice and calms down if crying

YES NO

When feeding, starts or stops sucking in response to sound

YES NO

Coos and makes pleasure sounds

YES NO

Has a special way of crying for different needs

YES NO

Smiles when he or she sees you

YES NO

4 to 6 Months

Follows sounds with his or her eyes

YES NO

Responds to changes in the tone of your voice

YES NO

Notices toys that make sounds

YES NO

Pays attention to music

YES NO

Babbles in a speech-like way and uses many different sounds, including sounds that begin with p, b, and m

YES NO

Laughs

YES NO

Babbles when excited or unhappy

YES NO

Makes gurgling sounds when alone or playing

with you

YES NO

7 Months to 1 Year

Enjoys playing peek-a-boo and pat-a-cake

YES NO

Turns and looks in the direction of sounds

YES NO

Listens when spoken to

YES NO

Understands words for common items such as “cup,” “shoe,” or “juice”

YES NO

Responds to requests (“Come here”)

YES NO

Babbles using long and short groups of sounds (“tata, upup, bibibi”)

YES NO

Babbles to get and keep attention

YES NO

Communicates using gestures such as waving or holding up arms

YES NO

Imitates different speech sounds

YES NO

Has one or two words (“Hi,” “dog,” “Dada,” or “Mama”) by first birthday

YES NO

1 to 2 Years

Knows a few parts of the body and can point to them when asked

YES NO

Follows simple commands (“Roll the ball”) and understands simple questions (“Where’s your shoe?”)

YES NO

Enjoys simple stories, songs, and rhymes

YES NO

Points to pictures, when named, in books

YES NO

Acquires new words on a regular basis

YES NO

Uses some one- or two-word questions (“Where kitty?” or “Go bye-bye?”)

YES NO

Puts two words together (“More cookie”)

YES NO

Uses many different consonant sounds at the beginning of words

YES NO

2 to 3 Years

Has a word for almost everything

YES NO

Uses two- or three-word phrases to talk about and ask for things

YES NO

Uses k, g, f, t, d, and n sounds

YES NO

Speaks in a way that is understood by family members and friends

YES NO

Names objects to ask for them or to direct attention to them

YES NO

3 to 4 Years

Hears you when you call from another room

YES NO

Hears the television or radio at the same sound level as other

family members

YES NO

Answers simple “Who?” “What?” “Where?” and “Why?” questions

YES NO

Talks about activities at daycare, preschool, or friends’ homes

YES NO

Uses sentences with four or more words

YES NO

Speaks easily without having to repeat syllables or words

YES NO

4 to 5 Years

Pays attention to a short story and answers simple questions about it

YES NO

Hears and understands most of what is said at home and in school

YES NO

Uses sentences that give many details

YES NO

Tells stories that stay on topic

YES NO

Communicates easily with other children and adults

YES NO

Says most sounds correctly except for a few (l, s, r, v, z, ch, sh, and th)

YES NO

Uses rhyming words

YES NO

Names some letters and numbers

YES NO

Uses adult grammar

YES NO

This checklist is based upon How Does Your Child Hear and Talk?, courtesy of the American Speech–Language–Hearing Association.

Where can I find additional information about speech and language developmental milestones?

The NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that provide information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech, and language.

Use the following keywords to help you find organizations that can answer questions and provide information on speech and language development:

- Early identification of hearing loss in children

- Language

- Speech-language pathologists

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse

1 Communication Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20892-3456

Toll-free voice: (800) 241-1044

Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055

Email: [email protected]

Development of speech at an early age: mechanisms and results of learning from birth to five years

Erika Hoff, PhD

Department of Psychology, Florida Atlantic University, USA

(English). Translation: June 2016

Translation: June 2016

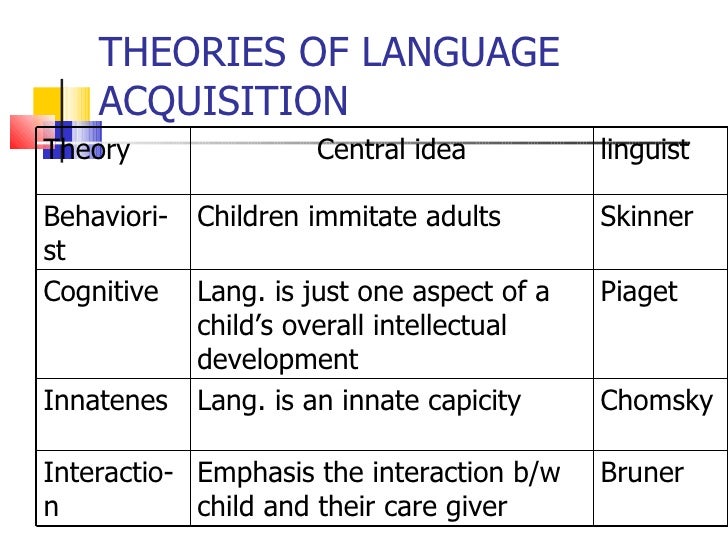

Language acquisition is one of the most outstanding achievements of early childhood. By the age of five, children have mastered the sound system and grammar of their native language to the required extent and master a vocabulary of several thousand words. This report describes the key milestones in language development that normally developing monolingual children go through in the first five years of life, and the mechanisms that have been proposed in science to explain these achievements.

Item

For young children, language proficiency is important for social and academic success. 1.2 Therefore, it is essential to have descriptions of normative development that allow the identification of children with language difficulties/impairments, as well as some understanding of those mechanisms of language acquisition that can serve as a basis for optimizing the development of all children.

Issues

Although naturally all normally developed children acquire the language(s) they hear, the rate at which children develop, and therefore their levels of language proficiency, vary considerably at each age. One of the goals of research in this area is to understand the role of innate abilities and environmental conditions in explaining the universality of language acquisition as a fact, as well as the variability in speech development. nine0020 3

Scientific context

Since ancient times, the language development of children has been a hot topic of study, and since the 1960s this problem has become central to a significant number of studies. 4 Although the frontiers of research in this area have expanded in recent years, there is still more work describing monolingual middle-class children learning English than other groups of children learning other languages. nine0008

Recent research results

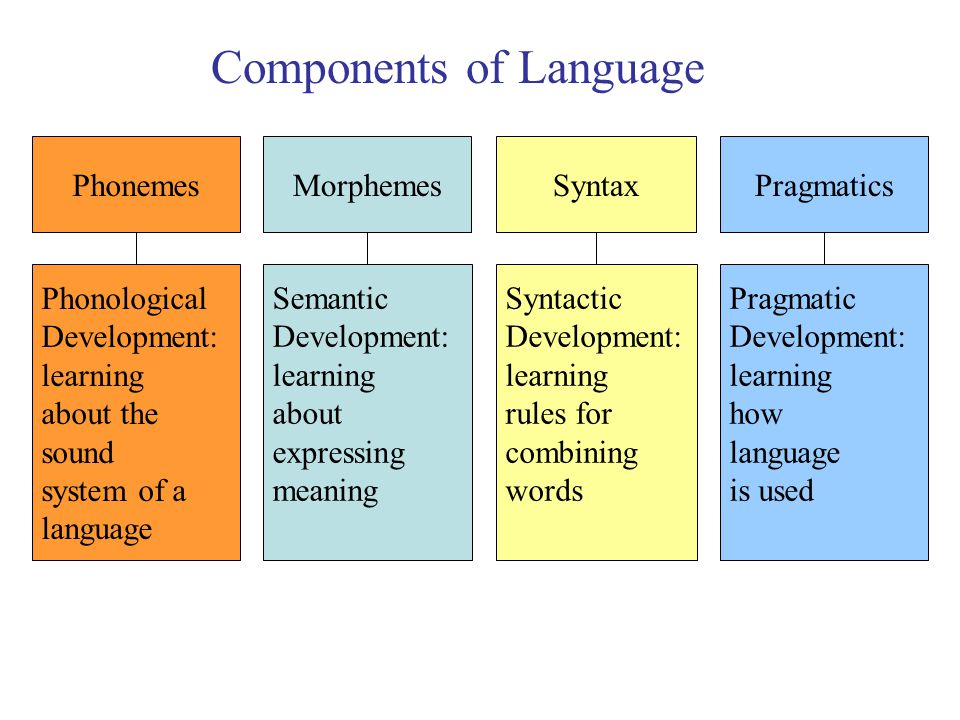

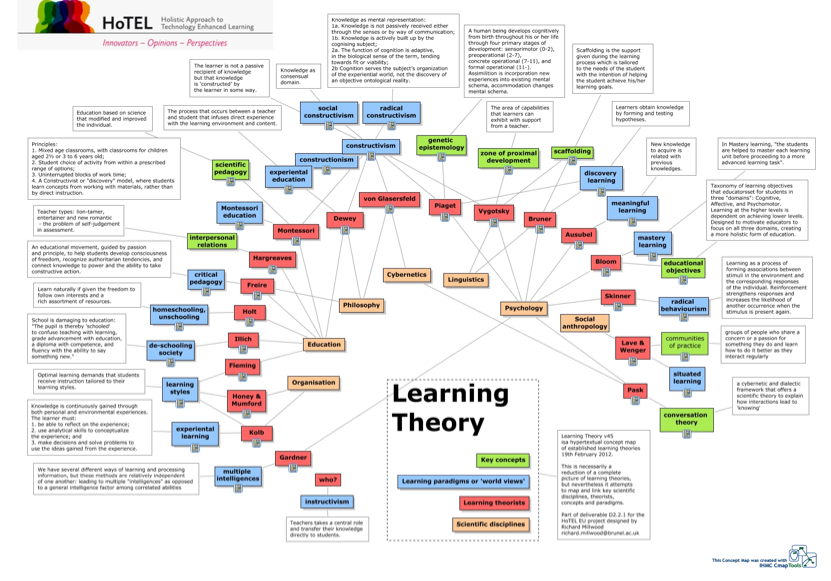

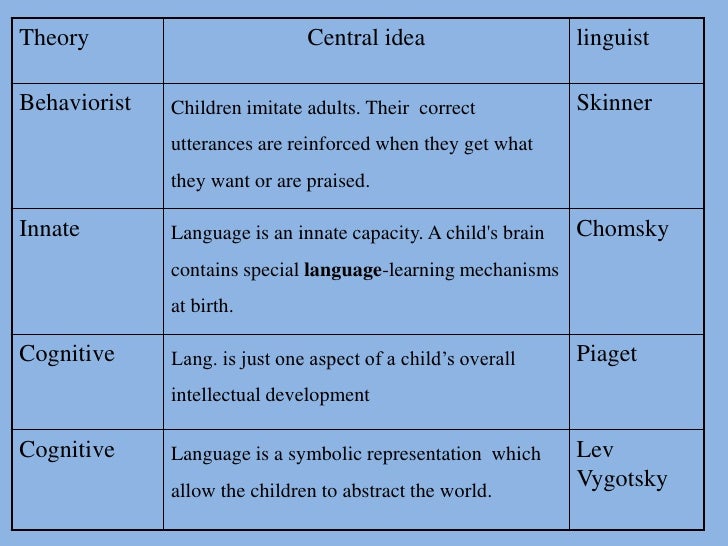

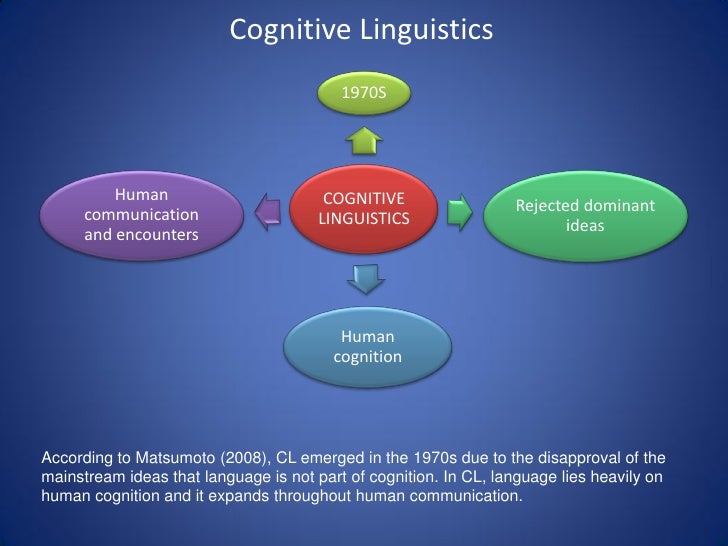

The course of language development and the mechanisms underlying it are usually described separately for each of the emerging sublevels: phonological (sound system), lexical (words), and morphosyntactic (grammar), despite that these areas are closely interrelated both in language development and in practical language proficiency.

Phonological development . Newborns have the ability to hear and distinguish speech sounds. nine0020 5 During the first year of life, they begin to better distinguish by ear the distinctive features of the sound structure of their language, and become insensitive to acoustic features that are not related to their language. This tuning of speech perception in relation to the language of the environment is the result of a learning process in which infants form mental categories of speech sounds around clusters of the most frequently occurring acoustic signals. These categories subsequently direct perception in such a way that variation within the category is ignored, and intercategory variation provokes an increase in attention. nine0020 6.7

The first sounds babies make are screams and noises that are not like speech sounds. Major milestones in the preverbal development of the vocal apparatus include the production of canonical syllables (well-formed combinations of consonants and vowels), which appear at 6-10 months of age; they are soon followed by a reduplicated coo (repetition of syllables). When the first words appear, they use the same sounds and contain the same number of sounds and syllables as the sound sequences in the previous humming stage. nine0020 8 One of the processes that seems to contribute to early phonological development is the active attempts of the infants themselves to reproduce the sounds they hear. It is possible that while cooing, babies learn to recognize the correspondence between the actions of their speech apparatus and the sounds that are produced. The conclusion about the significant role of feedback follows from the results of studies that demonstrate that children with hearing impairment master the canonical hum with a delay. As it turns out, by about 18 months, children develop some kind of mental system for representing the sounds of their native language and their production within the limits of articulatory possibilities available to them. At this stage, the production of speech sounds becomes consistent and uniform in various words, which contrasts with the previous period, in which the sound form of each word was a separate mental unit.

When the first words appear, they use the same sounds and contain the same number of sounds and syllables as the sound sequences in the previous humming stage. nine0020 8 One of the processes that seems to contribute to early phonological development is the active attempts of the infants themselves to reproduce the sounds they hear. It is possible that while cooing, babies learn to recognize the correspondence between the actions of their speech apparatus and the sounds that are produced. The conclusion about the significant role of feedback follows from the results of studies that demonstrate that children with hearing impairment master the canonical hum with a delay. As it turns out, by about 18 months, children develop some kind of mental system for representing the sounds of their native language and their production within the limits of articulatory possibilities available to them. At this stage, the production of speech sounds becomes consistent and uniform in various words, which contrasts with the previous period, in which the sound form of each word was a separate mental unit. nine0020 9 The processes underlying this development are not fully understood.

nine0020 9 The processes underlying this development are not fully understood.

Vocabulary development . Babies understand the first word as early as 5 months of age, speak their first words between 10 and 15 months, their active vocabulary reaches 50 words at about 18 months and increases to 100 words by 20 to 21 months. 10 Vocabulary development then proceeds so rapidly that keeping track of how many words children are learning becomes a difficult task. It has been estimated that the average six-year-old child has a vocabulary of 14,000 words. nine0020 11

Vocabulary acquisition has many components and mechanisms. 12 Infants use "statistical learning" procedures a to track the likelihood that sounds appear together and thereby segment a continuous stream of speech into individual words. 13 The ability to capture these sequences of sounds, known as phonological memory, comes into play as units of the mental lexicon are created. nine0020 14 In solving the task of matching a first encountered word with its intended referent, children are guided by their abilities to enable them to use socially determined inference mechanisms (i.e., speakers are likely to talk about things they look at), 15 cognitive representations of the world (learning some words required projecting new words onto existing concepts), 16 and one's own prior linguistic knowledge (i.e., the structure of the sentence in which the new word appears offers clues to the meaning of the word). nine0020 17 Full mastery of the meanings of words may also require the formation of new concepts. 18

nine0020 14 In solving the task of matching a first encountered word with its intended referent, children are guided by their abilities to enable them to use socially determined inference mechanisms (i.e., speakers are likely to talk about things they look at), 15 cognitive representations of the world (learning some words required projecting new words onto existing concepts), 16 and one's own prior linguistic knowledge (i.e., the structure of the sentence in which the new word appears offers clues to the meaning of the word). nine0020 17 Full mastery of the meanings of words may also require the formation of new concepts. 18

Development of the morphosyntactic sphere . Children begin to make short sentences of two, then three or more words around the age of 24 months. The first children's sentences are combinations of significant parts of speech, which often lack auxiliary parts of speech (for example, articles and prepositions) and word endings (for example, plural endings and tense markers). As children gradually master the grammar of their native language, they develop the ability to make longer and more grammatically complete sentences. Compound sentences (that is, sentences with multiple clauses) usually begin shortly before the child is 2 years old, and this skill is completed by the age of 4. As a rule, perception precedes production. nine0020 4

As children gradually master the grammar of their native language, they develop the ability to make longer and more grammatically complete sentences. Compound sentences (that is, sentences with multiple clauses) usually begin shortly before the child is 2 years old, and this skill is completed by the age of 4. As a rule, perception precedes production. nine0020 4

The mechanism responsible for development in the field of grammar is one of the most actively discussed topics in the field of children's language learning. There is an assertion that children begin language acquisition based on innate knowledge of the structure of the language, and that it is impossible to master the language in any other way. However, it is also clear that already in infancy, children are able to recognize abstract language constructs in the speech they hear. 19 There is strong evidence that children who hear speech more often and who hear structurally more complex speech acquire grammar faster than children who have less such experience 3. 20 - all this indicates that language experience plays a significant role in the development of speech in children.

20 - all this indicates that language experience plays a significant role in the development of speech in children.

Unexplored areas

A gap or inconsistency in this area is found between the desire to theoretically explain the universal fact of language acquisition and the need to understand the causes of individual differences in language development for applied purposes. Related to this is the fact that there is less research on linguistic minorities and research on bilingual development than on monolingual development done on middle-class samples. This is a major gap as most standardized assessment tools are not suitable for detecting organic developmental delay in minority, low socioeconomic or multilingual children. nine0008

Conclusions

The process of language development in different children, regardless of the language, is characterized by uniformity, which serves as an indication of the universal biological basis of this human ability. The pace of language development varies widely, but it depends on the amount and nature of children's language experience, as well as on the children's ability to use this experience.

The pace of language development varies widely, but it depends on the amount and nature of children's language experience, as well as on the children's ability to use this experience.

Recommendations

Children with normal developmental abilities need only the experience of conversational interaction in order to acquire language. However, many children may be missing out on conversational experiences that would maximize their language development. Parents should be encouraged to treat their young children as companions from infancy. Educators and policy makers need to understand that children's language skills reflect not only their cognitive abilities, but also the opportunities to hear and use language provided by those around them. nine0008

Literature

- Black B, Logan A. Links between communication patterns in mother-child, father-child, and child-peer interactions and children’s social status. Child Development 1995;66(1):255-271.

- Morrison F, Bachman H, Connor C. Improving literacy in America: Guidelines from research . New Haven: Yale University Press; 2005.

- Hoff E. How social contexts support and shape language development. nine0046 Developmental Review 2006;26(1):55-88.

- Hoff E. Language development . 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2009.

- Aslin RN, Jusczyk PW, Pisoni D. Speech and auditory processing during infancy: Constraints on and precursors to language. In: Damon W, ed-in-chief. Handbook of child psychology . 5 th Ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1998: 147-198. Kuhn D, Siegler RS, eds. Cognition, perception, and language. Vol 2.

- Kuhl PK, Conboy B, Padden D, Nelson T, Pruitt J. Early speech perception and later language development: Implications for the “critical period.” Language Learning and Development 2005;1(3-4):237-264.

- Werker JF, Curtin S. PRIMIR: A developmental framework of infant speech processing.

Language Learning and Development 2005;1(2):197-234.

Language Learning and Development 2005;1(2):197-234. - Fagan MK. Mean Length of Utterance before words and grammar: Longitudinal trends and developmental implications of infant vocalizations. nine0046 Journal of Child Language 2009; 36(3):495-527.

- Stoel-Gammon C, Sosa AV. Phonological development. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 238-256.

- Pine J M. Variation in vocabulary development as a function of birth order. Child Development 1995;66(1):272-281.

- Templin M. Certain language skills in children, their development and interrelationships. nine0047 Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1957.

- Diesendruck, G. Mechanisms of word learning. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 257-276.

- Saffran JR, Thiessen ED.

Domain-general learning capacities. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing LTD; 2007: 68-86.

Domain-general learning capacities. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing LTD; 2007: 68-86. - Gathercole SE. Nonword repetition and word learning: The nature of the relationship. nine0046 Applied Psycholinguistics 2006;27(4):513-543.

- Baldwin D, Meyer M. How inherently social is language? In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 87-106.

- Poulin-Dubois D, Graham SA. Cognitive processes in early word learning. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 191-211.

- Naigles LR, Swensen LD. Syntactic supports for word learning In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. nine0046 Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 212-232.

- Carey S. The origin of concepts .

New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009.

New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. - Gerken L. Acquiring linguistic structure. In: Hoff E, Shatz M, eds. Blackwell Handbook of Language Development . Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 173-190.

- Vasilyeva M, Waterfall H, Huttenlocher J. Emergence of syntax: Commonalities and differences across children. nine0046 Developmental Science 2008;11(1):84-97.

Note:

a “statistical learning” in infants is a theory put forward by Jenny Saffran and colleagues (Saffran, Aslin, & Newport, 1996) that infants have the ability to use statistical information from their environment to when self-learning language elements, for example, words.

Language development and its impact on children's psychosocial and emotional development

Joseph Beichman, MD, Elizabeth Brownlee, PhD

University of Toronto, Canada

, Rev. ed. (English). Translation: June 2016

ed. (English). Translation: June 2016

Introduction

Language is central to social life; Language and speech development is the cornerstone for successful outcomes later in life. At the same time, speech and language competence does not develop normally in a significant number of children, and studies show that these children are at greater risk of subsequent psychological problems than children who do not have speech or language disorders.

Research has provided compelling evidence that the psychosocial consequences of language disorders in childhood and adolescence are disproportionately problematic; some defects persist into adulthood. These consequences include ongoing defects in speech and language competence, intellectual functioning, school adjustment and achievement, psychosocial difficulties, and an increased likelihood of psychiatric disorder. The key findings of the studies highlighted in this evidence review imply the need for early detection of language disorders and effective interventions to address these disorders, as well as their associated cognitive, academic, behavioral and psychosocial problems, and to prevent victimization in this population. Support for children and adolescents who have language disabilities is especially important in the context of the school. nine0008

The key findings of the studies highlighted in this evidence review imply the need for early detection of language disorders and effective interventions to address these disorders, as well as their associated cognitive, academic, behavioral and psychosocial problems, and to prevent victimization in this population. Support for children and adolescents who have language disabilities is especially important in the context of the school. nine0008

Subject

There is strong evidence for an association between speech and language difficulties and psychiatric disorders. 1,2,3 Children with speech and language difficulties are more likely to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2,5,6,7 Weak verbal skills are associated with child delinquency and behavioral problems, especially in boys. 8.9 Children with language difficulties in early childhood are more likely to experience coexisting and late onset behavioral problems than children with normal language development. nine0020 10,11,12,13 Language difficulties, more than speech alone, are associated with persistent behavioral problems. 10.11 Adolescents with language difficulties often have social difficulties and may be bullied or socially isolated from their peers. 10,14,15 In follow-up studies of children with language difficulties referred to clinics, ongoing social problems in adulthood have been reported. nine0020 16

nine0020 10,11,12,13 Language difficulties, more than speech alone, are associated with persistent behavioral problems. 10.11 Adolescents with language difficulties often have social difficulties and may be bullied or socially isolated from their peers. 10,14,15 In follow-up studies of children with language difficulties referred to clinics, ongoing social problems in adulthood have been reported. nine0020 16

Language difficulties are strongly associated with poor academic performance in childhood and adolescence. Clinically registered children and young people with language difficulties are, on average, less successful than children in the general population; 17,18,19 these results were confirmed by longitudinal epidemiological studies. 20.21.22.23 Children with language difficulties at age five are eight times more likely to have learning difficulties at age 19years than children without language disorders. 21 Recent studies show that children with language difficulties differ from children with normal language abilities in intellectual development and in information processing processes, including short-term memory and auditory information processing. 24,25,26

24,25,26

Issues

Studies of the consequences of speech and language difficulties cannot be considered exhaustive. First, many of the studies describing the long-term effects of speech and language difficulties have used clinical samples instead of community-based samples. These studies do not represent the full spectrum of speech and language difficulties. Individuals referred for treatment tend to be severely impaired and/or have more prominent impairments than those who are not referred. They are more likely to have comorbid disorders, especially behavioral problems that draw attention to themselves and lead to visits to a doctor, 27 while individuals with more subtle problems, especially girls, may not be identified .27,28 language history. Third, very few non-clinical studies have published results beyond adolescence into adulthood. Fourth, some studies of samples of adults with the consequences of language impairment did not take into account data from matched controls, thus severely limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Fifth, available research rarely includes measurement of outcomes across multiple domains of performance. This is a critical omission, as problems in other areas of psychosocial function may persist even if speech and language difficulties are resolved. Extended surveys can also reveal strengths and similarities between individuals with language difficulties and individuals with normal language development. Finally, more attention needs to be paid to social contexts related to the consequences of speech/language difficulties. nine0020 28.29 For example, few studies have paid direct attention to gender in relation to the consequences of language impairments; most of what is done is focused on young children. 15.30

Fifth, available research rarely includes measurement of outcomes across multiple domains of performance. This is a critical omission, as problems in other areas of psychosocial function may persist even if speech and language difficulties are resolved. Extended surveys can also reveal strengths and similarities between individuals with language difficulties and individuals with normal language development. Finally, more attention needs to be paid to social contexts related to the consequences of speech/language difficulties. nine0020 28.29 For example, few studies have paid direct attention to gender in relation to the consequences of language impairments; most of what is done is focused on young children. 15.30

Scientific context

The Ottawa Language Study (OLS) is the first population-based study of children with speech/language difficulties followed up into adulthood. 31 Randomly selected from all five-year-old English-speaking children in the Ottawa-Carleton Regional Municipality of Ontario, Canada, one in three children had a speech and language screening procedure by qualified speech pathologists. nine0020 32 As a result of these procedures, a sample of 142 children with speech and/or language difficulties was recruited. At the same time, a control sample of 142 children was recruited, matched by age, gender, and from the same grade or school as the children with difficulties/impairments. Both samples were fully assessed for cognitive, age, emotional, behavioral and mental functioning. 6 Three follow-up surveys of original OLS participants were undertaken when participants were aged 12, 19and 25 years old. 2,7,31 The retention rate for each of these follow-up studies exceeded 85% of the original sample. The fourth study (age 31/32) is currently underway.

nine0020 32 As a result of these procedures, a sample of 142 children with speech and/or language difficulties was recruited. At the same time, a control sample of 142 children was recruited, matched by age, gender, and from the same grade or school as the children with difficulties/impairments. Both samples were fully assessed for cognitive, age, emotional, behavioral and mental functioning. 6 Three follow-up surveys of original OLS participants were undertaken when participants were aged 12, 19and 25 years old. 2,7,31 The retention rate for each of these follow-up studies exceeded 85% of the original sample. The fourth study (age 31/32) is currently underway.

Key questions

Some of the key questions raised by the OLS project: Do language impairments/disorders persist with age? Are language impairments/difficulties/disorders associated with behavioral problems in childhood, adolescence or adulthood? Do language difficulties predict academic performance, educational attainment, and professional outcomes? Are language difficulties in early childhood associated with a higher incidence of psychiatric disorders throughout life? Are the psychosocial consequences of language difficulties different for boys and girls? nine0008

Recent research results

Language difficulties often persist into adulthood. 33.34 Pure speech disorder disappears, as do most of the associated psychosocial problems. 2.33 In the OLS, children and adolescents with childhood language difficulties had a significantly increased rate of behavioral problems and psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety, compared with controls with normal language skills at ages 5, 12, and 19years old. 2,6,7 Social phobia was more common among the speech/language group/cohort; Difficulties in communication can represent one of the clear paths to social phobia. 35 Externalizing problems such as ADHD and delinquency have been associated with language difficulties in boys but not in girls; 11 Rates of antisocial personality disorder among men were almost three times higher than those of men with normal language skills in the control group. nine0020 2 Girls with language difficulties were three times more likely to experience sexual abuse during childhood or adolescence than girls without language problems; 28 this difference was not due to differences in socioeconomic status between the group with language difficulties and the group with normal language development.

33.34 Pure speech disorder disappears, as do most of the associated psychosocial problems. 2.33 In the OLS, children and adolescents with childhood language difficulties had a significantly increased rate of behavioral problems and psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety, compared with controls with normal language skills at ages 5, 12, and 19years old. 2,6,7 Social phobia was more common among the speech/language group/cohort; Difficulties in communication can represent one of the clear paths to social phobia. 35 Externalizing problems such as ADHD and delinquency have been associated with language difficulties in boys but not in girls; 11 Rates of antisocial personality disorder among men were almost three times higher than those of men with normal language skills in the control group. nine0020 2 Girls with language difficulties were three times more likely to experience sexual abuse during childhood or adolescence than girls without language problems; 28 this difference was not due to differences in socioeconomic status between the group with language difficulties and the group with normal language development.

By age 25, the incidence of mental impairment among participants with language difficulties and participants with normal language development was lower than at age 19years old. 36 In addition, quality of life, job satisfaction, and available social support were high in both the language-impaired and normal control group. 31 Participants with language difficulties were less likely than participants in the control group to receive or complete higher education; three-quarters have completed high school. Young people with language difficulties were just as employed as their peers in the control group, often choosing careers in areas that probably do not require advanced verbal skills. Women with language difficulties gave birth to children earlier than women with normal language development; half had children under the age of 25. nine0020 31 Early parenting may partly reflect low job opportunities for women without college education (excluding jobs traditionally held by men, such as construction).

Findings

The OLS has shown that during childhood and adolescence, outcomes for children with a history of language impairment are markedly more negative than outcomes for children with speech-only impairments or children without impairments. Children with language impairments showed marked comorbid and long-term impairments in language, cognitive, and academic areas compared with peers without early language difficulties and were less likely to complete education. Boys with language disorders were at risk for delinquent and antisocial behavior; girls with language impairments were more likely to experience sexual violence28 and become parents earlier.31 However, by age 25, youth with and without language impairments were equally likely to have a job, and the groups did not differ in quality of life or available social support. nine0008

Policy and service recommendations

Children with language difficulties have relatively poor outcomes in childhood through late adolescence. They are more likely to develop anxiety disorders that have a negative impact on the quality of life of adults around them and entail significant economic and medical costs. 37 In addition, language difficulties in early childhood tend to persist and their effects are observed from early childhood to adolescence. Researchers confirm the effectiveness of early intervention in language development. nine0020 38 Language and speech professionals should continue to educate the public and other professionals about the importance of early intervention in language development.

They are more likely to develop anxiety disorders that have a negative impact on the quality of life of adults around them and entail significant economic and medical costs. 37 In addition, language difficulties in early childhood tend to persist and their effects are observed from early childhood to adolescence. Researchers confirm the effectiveness of early intervention in language development. nine0020 38 Language and speech professionals should continue to educate the public and other professionals about the importance of early intervention in language development.

At the same time, improvements in the well-being of people aged 19 to 25, despite continued language difficulties, suggest that differences in social contexts may play an important role in the psychosocial problems of youth with language difficulties. In particular, the demands of the school environment can be stressors that exacerbate the problems of adolescents with language difficulties. For example, children with language disabilities may experience bullying at school, 14 and many teenagers with language difficulties experience fear when speaking in front of others. 35 Unlike young people in compulsory education, adults with a language disability have the opportunity to choose a profession according to their strengths, which is less dependent on verbal skills. 16.31 These results point to the need for active support systems for children with language difficulties in school and attention to all aspects of their school environment. Gender should also be taken into account in interventions targeting youth with language difficulties. In particular, prevention of victimization should be a necessary part of working with youth with language difficulties, especially girls. Children with a history of speech and language difficulties are more likely to have multiple problems than their healthy peers, and thus are most likely to benefit from early intervention. This demonstrates the relevance of early detection of language difficulties, development and maintenance of reliable treatment programs that affect the many adverse risk factors for this category of children, while at the same time supporting their participants' stress resistance and adaptation.

35 Unlike young people in compulsory education, adults with a language disability have the opportunity to choose a profession according to their strengths, which is less dependent on verbal skills. 16.31 These results point to the need for active support systems for children with language difficulties in school and attention to all aspects of their school environment. Gender should also be taken into account in interventions targeting youth with language difficulties. In particular, prevention of victimization should be a necessary part of working with youth with language difficulties, especially girls. Children with a history of speech and language difficulties are more likely to have multiple problems than their healthy peers, and thus are most likely to benefit from early intervention. This demonstrates the relevance of early detection of language difficulties, development and maintenance of reliable treatment programs that affect the many adverse risk factors for this category of children, while at the same time supporting their participants' stress resistance and adaptation. nine0008

nine0008

Literature

- Baker L, Cantwell DP. A prospective psychiatric follow-up of children with speech/language disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1987;26(4):546-553.

- Beitchman JH, Wilson B, Johnson CJ, Atkinson L, Young A, Adlaf A, Escobar M, Douglas L. Fourteen-year follow-up of speech/language-impaired and control children: Psychiatric outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2001;40(1):75-82.

- Benner GJ, Nelson JR, Epstein MH. Language skills of children with EBD: A literature review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 2002;10(1):43-59.

- Cohen NJ, Davine M, Horodezky N, Lipsett L, Isaacson L. Unsuspected language impairment in psychiatrically disturbed children: Prevalence and language and behavioral characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry .

1993;32(3):595-603.

1993;32(3):595-603. - Cantwell DP, Baker L. Psychiatric and developmental disorders in children with communication disorder. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1991.

- Beitchman JH, Nair R, Clegg M, Ferguson B, Patel PG. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in children with speech and language disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 1986;25(4):528-535.

- Beitchman JH, Brownlie EB, Inglis A, Wild J, Ferguson B, Schachter D, Lancee W. Wilson B. Mathews R. Seven-year follow-up of speech/language impaired and control children: Psychiatric outcome. nine0046 Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1996;37(8):961-970.

- Hinshaw SP. Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: Causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin 1992;111(1):127-155.

- Lynam D, Moffitt TE, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Explaining the relation between IQ and delinquency: class, race, test motivation, school failure, or self-control.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1993;102(2):187-196.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1993;102(2):187-196. - Beitchman JH, Wilson B, Brownlie EB, Walters H, Inglis A, Lancee W. Long-term consistency in speech/language profiles: II. Behavioral, emotional, and social outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1996;35(6):815-825.

- Brownlie EB, Beitchman JH, Escobar M, Young A, Atkinson A, Johnson C, Wilson B, Douglas L. Early language impairment and young adult delinquent and aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2004;32(4):453-467.

- Conti-Ramsden G, Botting N. Emotional health in adolescents with and without a history of specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2008;49(5):516-525.

- Snowling MJ, Bishop DVM, Stothard SE, Chipchase B, Kaplan C. Psychosocial outcomes at 15 years of children with a preschool history of speech-language impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2006;47(8):759-765.

nine0120 Conti-Ramsden G, Botting N. Social difficulties and victimization in children with SLI at 11 years of age. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 2004;47(1):145-161.

nine0120 Conti-Ramsden G, Botting N. Social difficulties and victimization in children with SLI at 11 years of age. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 2004;47(1):145-161. - Bonica C, Arnold DH, Fisher PH, Zeljo A, Yershova K. Relational aggression, relational victimization, and language development in preschoolers. Social Development 2003;12(4):551-562.

- Howlin P, Mawhood L, Rutter M. Autism and developmental receptive language disorder – a follow-up comparison in early adult life. II: Social, behavioral, and psychiatric outcomes. nine0046 Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2000;41(5):561-578.

- Botting N, Simkin Z, Conti-Ramsden G. Associated reading skills in children with a history of Specific Language Impairment (SLI). Reading and Writing 2006;19(1):77-98.

- Conti-Ramsden G, Durkin K, Simkin Z, Knox E. Specific language impairment and school outcomes. I: Identifying and explaining variability at the end of compulsory education.

International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 2009;44(1):15-35.

International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 2009;44(1):15-35. - Whitehouse AJO, Line EA, Watt HJ, Bishop DVM. Qualitative aspects of developmental language impairment relate to language and literacy outcome in adulthood. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 2009;44(4):489-510.

- Beitchman JH, Wilson B, Brownlie EB, Walters H, Lancee W. Long-term consistency in speech/language profiles: I. Developmental and academic outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1996;35(6):804-814.

- Young AR, Beitchman JH, Johnson C, Douglas L, Atkinson L. Young adult academic outcomes in a longitudinal sample of early identified language impaired and control children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2002;43(5):635-645.

- Catts HW, Fey ME, Tomblin JB, Zhang X. A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments.

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2002;45:1142-1157. nine0123

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2002;45:1142-1157. nine0123 - Puranik CS, Petscher Y, Al Otaiba S, Catts HW, Lonigan CJ. Development of oral reading fluency in children with speech or language impairments: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities 2008;41(6):545-560.

- Montgomery JW, Evans JL. Complex sentence comprehension and working memory in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 2009;52(2):269-288.

- Nickisch A, von Kries R. Short-term memory (STM) constraints in children with specific language impairment (SLI): Are there differences between receptive and expressive SLI? nine0046 Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 2009;52(3):578-595.

- McArthur G, Atkinson C, Ellis D. Atypical brain responses to sounds in children with specific language and reading impairments. Developmental Science 2009;12(5):768-783.

- Zhang X, Tomblin JB. The association of intervention receipt with speech-language profiles and social-demographic variables. A merican Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2000;9(4):345-357. nine0123

- Brownlie EB, Jabbar A, Beitchman J, Vida R, Atkinson L. Language impairment and sexual assault of girls and women: Findings from a community sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2007;35(4):618-626.

- La Paro KM, Justice L, Skibbe LE, Pianta RC. Relations among maternal, child, and demographic factors and the persistence of preschool language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2004;13(4):291-303.

- Stowe RM, Arnold DH, Ortiz C. Gender differences in the relationship of language development to disruptive behavior and peer relationships in preschoolers. nine0046 Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 1999;20(4):521-536.

- Johnson, CJ, Beitchman JH, Browlie EB. Twenty-year follow-up of children with and without speech-language impairments.

Am erican J ournal of Speech Lang uage Pathology . In press.

Am erican J ournal of Speech Lang uage Pathology . In press. - Beitchman JH, Nair R, Clegg M, Patel PG. Prevalence of speech and language disorders in 5-year-old kindergarten-children in the Ottawa-Carleton region. nine0046 Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 1986;51(2):98-110.

- Johnson CJ, Beitchman JH, Young A, Escobar M, Atkinson L, Wilson B, Browlie EB, Douglas L, Taback N, Lam I, Wang M. Fourteen-year follow-up of children with and without speech language impairments: Speech language stability and outcomes. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 1999;42(3):744-760.

- Beitchman JH, Jiang H, Koyama E, Johnson C, Escobar M, Atkinson L, Brownlie EB, Vida R. Models and determinants of vocabulary growth from kindergarten to adulthood. nine0046 Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2008;49(6):626-634.

- Voci SC, Beitchman JH, Brownlie EB, Wilson B.

Social anxiety in late adolescence: The importance of early childhood language impairment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2006;20(7):915-930.

Social anxiety in late adolescence: The importance of early childhood language impairment. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2006;20(7):915-930. - Vida R, Brownlie EB, Beitchman JH, Adlaf E, Atkinson L, Escobar M, Johnson CJ, Jiang H, Koyama E, Bender B. Emerging adult outcomes of adolescent psychiatric and substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors 2009;34(10):800-805.

- Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JRT, Ballenger JC, Fyer AJ. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1999;60(7):427-435.

- Leonard LB. Children with specific language impairment . Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1998.

For citation:

Beichman D, Brownlee E. Language development and its impact on children's psychosocial and emotional development. In: Tremblay RE, Buavan M, Peters RDeV, eds. Rvachev S, red. themes.