Immune system of newborn babies

How your baby's immune system develops

How your baby's immune system develops | Pregnancy Birth and Baby beginning of content6-minute read

Listen

Babies' immune systems are not as strong as those of adults. Breastfeeding and vaccinating your baby will help protect them from a serious illness.

What is the immune system?

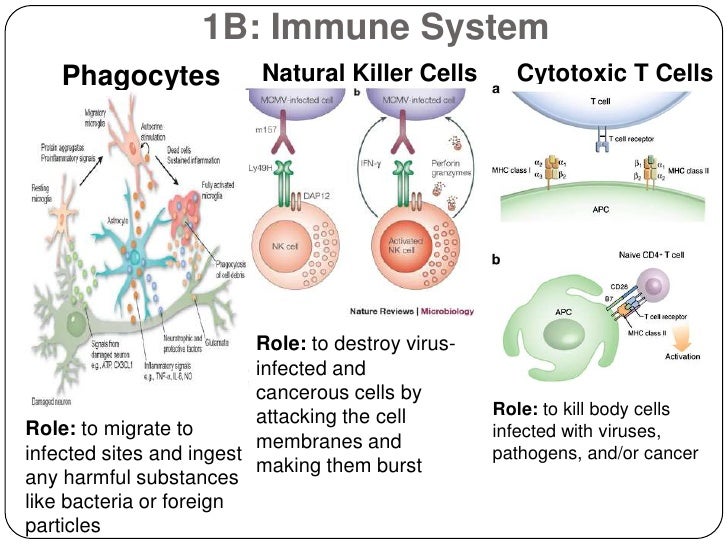

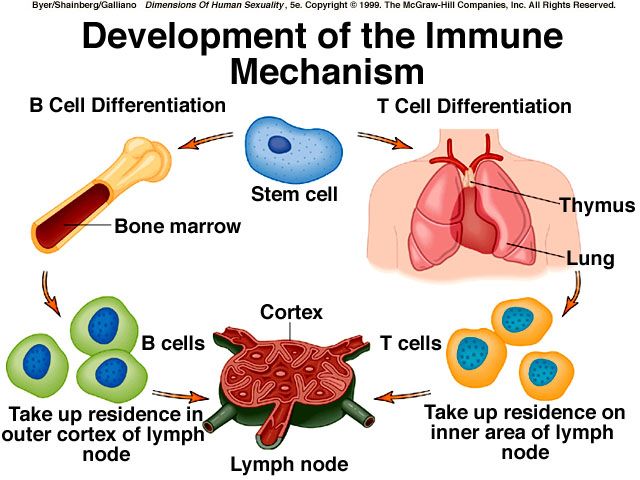

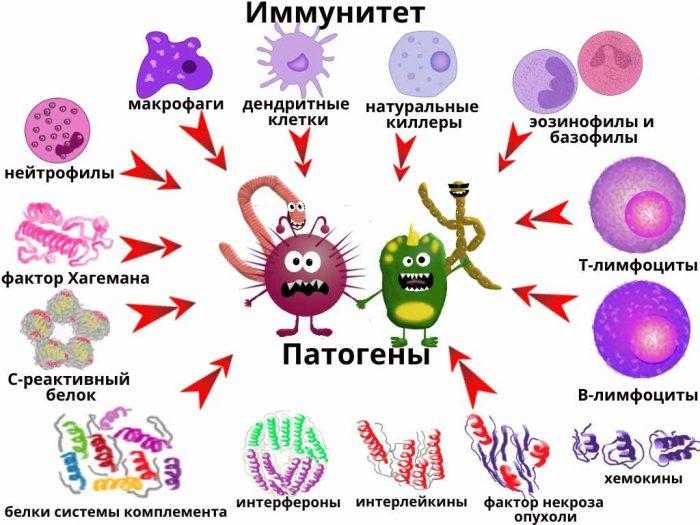

Your immune system is a network of cells and proteins that are found throughout your body. The immune system fights germs that cause infection.

Germs such as bacteria and viruses are sometimes described as ‘foreign’. This is because they don’t belong in our bodies. Germs can cause your baby to become sick.

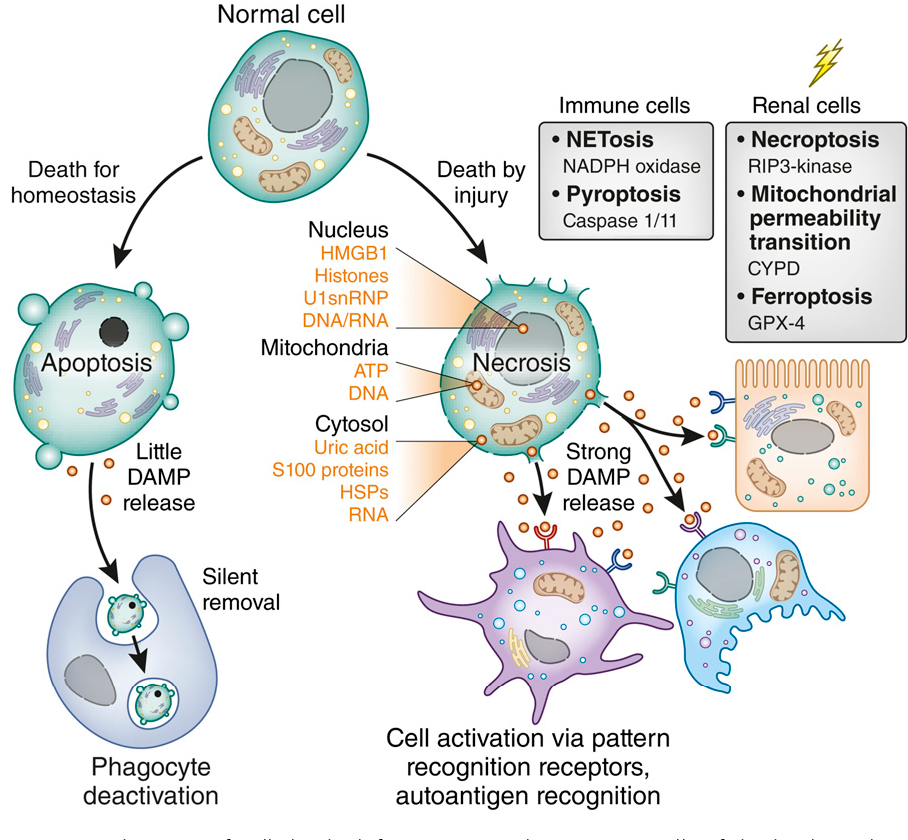

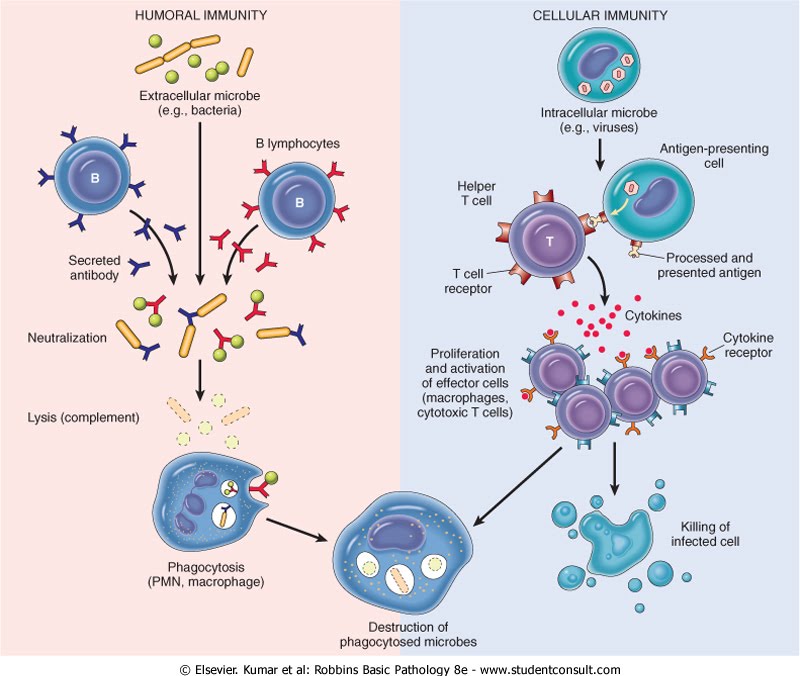

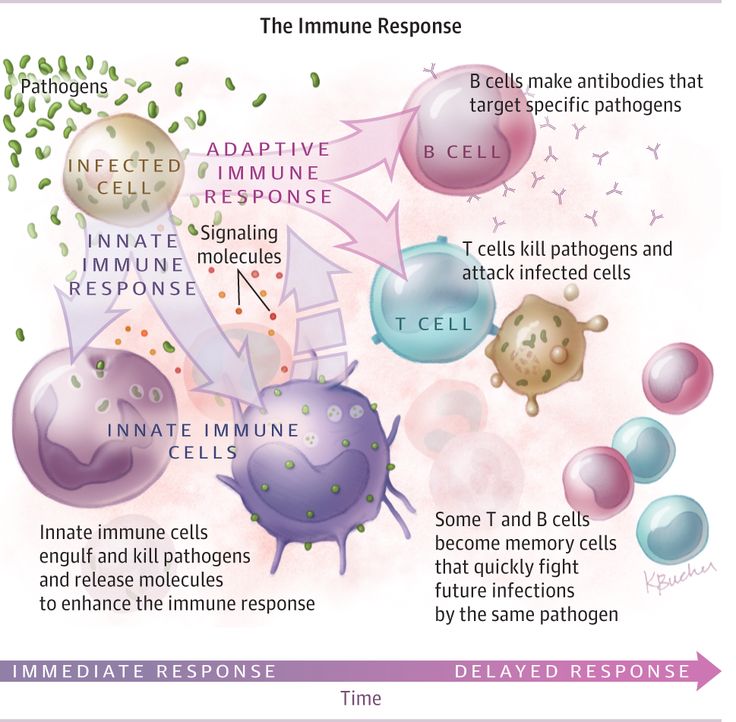

If bacteria, a virus or something foreign gets into your body, the immune system starts to act quickly. White blood cells notice that something foreign has entered your body. The white blood cells make special proteins called ‘antibodies’, and also switch on other parts of the immune system. This is called the ‘immune response’ and it fights the infection.

After antibodies have been made, the immune system can 'remember' the germ or virus. This helps the body to fight the germ more easily next time. This memory is called ‘immunity’.

The immune system in babies

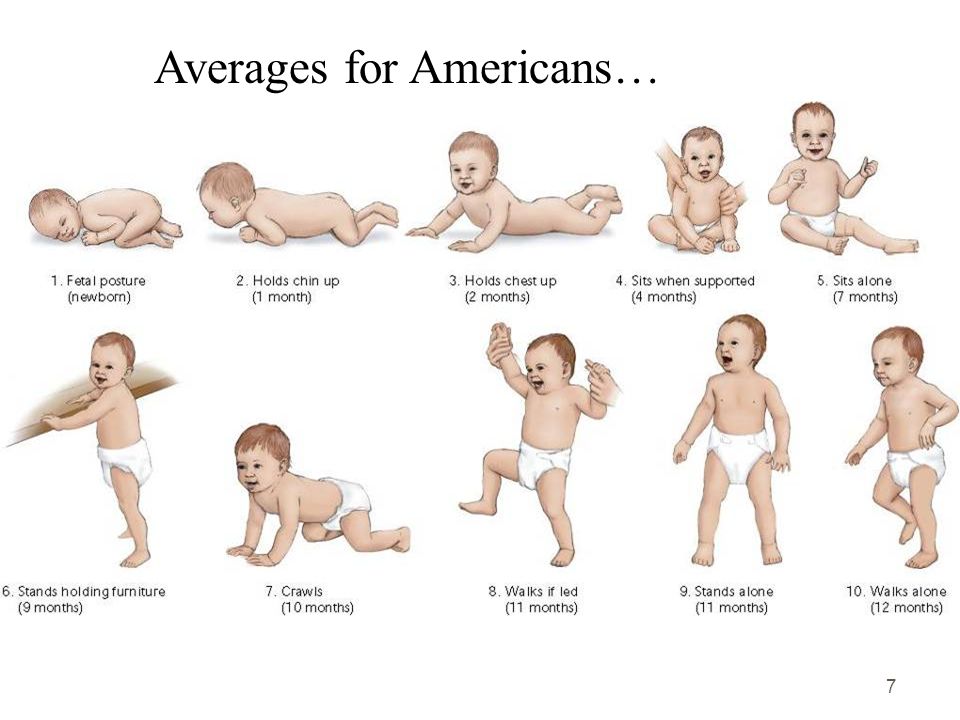

A baby’s immune system is not fully developed when they are born. It gets stronger as the baby gets older. The immune system works throughout our lives fighting germs that can cause disease.

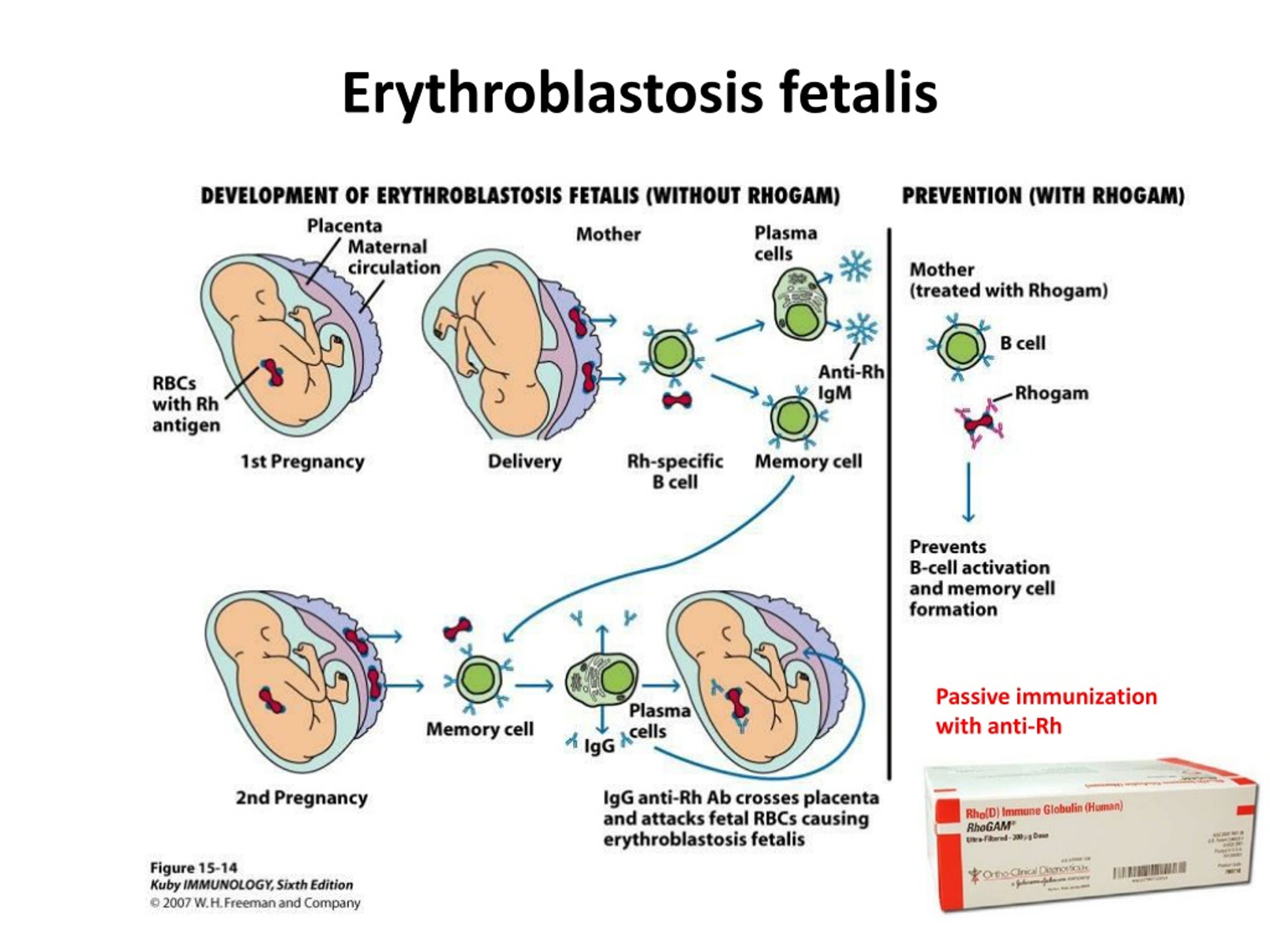

A mother’s antibodies are shared with their baby through the placenta during the third trimester (last 3 months) of pregnancy. The mother’s antibodies help protect the baby from illnesses when the baby is born. The type of antibodies passed from mother to baby depends on the mother’s own level of immunity.

Good bacteria in our gut help our immune system to work well. During birth, these good bacteria are in the vagina and are passed on to the baby. This helps good bacteria to start living in the baby’s gut.

This helps good bacteria to start living in the baby’s gut.

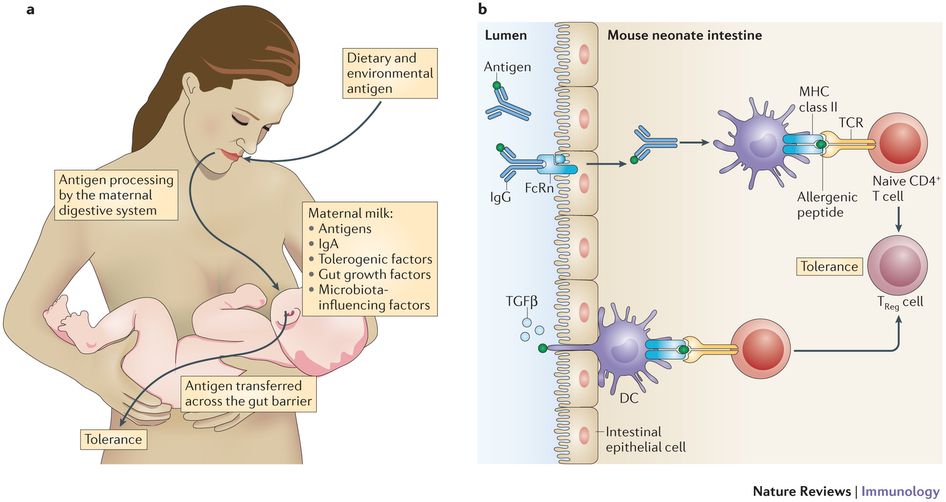

After birth, more antibodies are passed to your baby from the colostrum and in breast milk.

Premature babies

Premature babies do not receive as many antibodies from their mothers as full-term babies. Their immune systems are not very strong. Premature babies have a greater chance of getting sick from germs like bacteria and viruses.

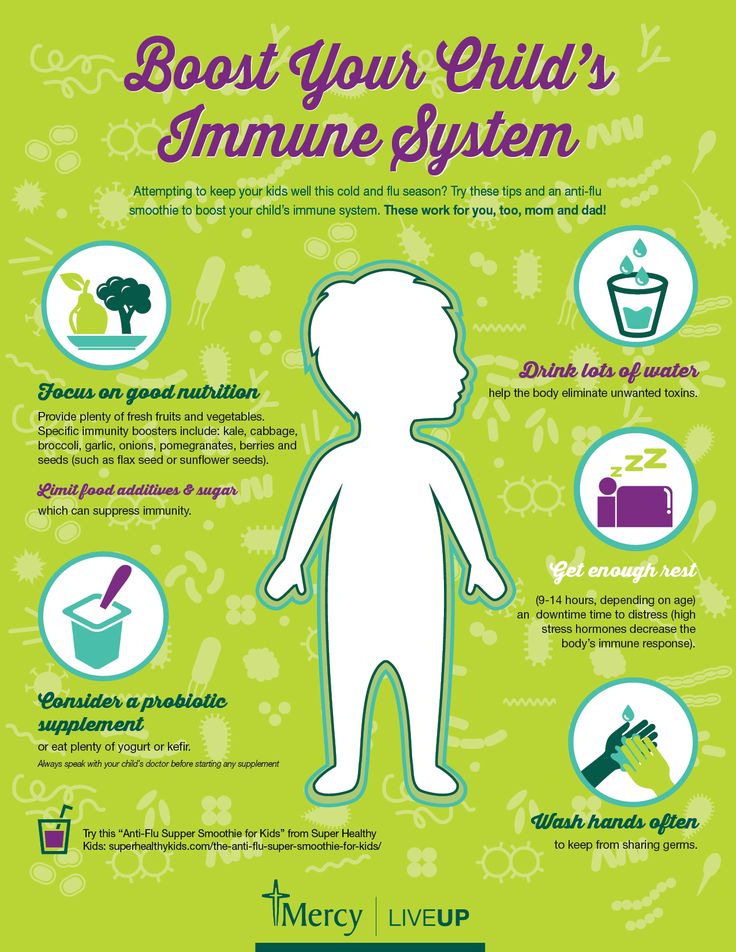

How to boost your baby’s immune system

The immunity that your baby receives from their mother at birth does not last long. It will gradually go away after a few weeks or months.

Babies make their own antibodies. Each time they get infected with a virus or other germ, their immune system starts to work. They make new antibodies that will protect them now and in the future.

But immunity in a baby is not as strong as in adults. And it takes time to fully develop. In the meantime, there are some important things you can do to protect your baby.

Breastfeeding

Breast milk contains many good things to help build your baby’s immune system. These include proteins, fats, and sugars, as well as antibodies and probiotics. When a mother comes into contact with germs, she makes antibodies to help her fight the infection. These are passed to the baby in breast milk. Because mothers and babies usually come into contact with the same germs, the mother’s breast milk can protect the baby.

These include proteins, fats, and sugars, as well as antibodies and probiotics. When a mother comes into contact with germs, she makes antibodies to help her fight the infection. These are passed to the baby in breast milk. Because mothers and babies usually come into contact with the same germs, the mother’s breast milk can protect the baby.

Breastfed babies have fewer infections and get better more quickly than formula-fed babies. However, for mothers who are unable to breastfeed or who choose not to, infant formula is a healthy option.

Breastfeeding cannot fully protect your baby from life-threatening infections like polio, diphtheria or measles. These diseases are very serious and can make your baby very sick. Fortunately, we now have vaccines that work with the immune system to protect your baby.

Vaccination

Vaccinating your children is the safest and most effective way to protect them against serious disease.

Vaccination causes an immune response in the same way that a virus or bacteria would. But it makes an immune response happen without the child actually getting sick. The vaccine makes your child ‘immune’. If your child catches the real disease in future, their immune system will remember the germ. The immune response will swing into action and fight off the disease, or prevent serious complications.

But it makes an immune response happen without the child actually getting sick. The vaccine makes your child ‘immune’. If your child catches the real disease in future, their immune system will remember the germ. The immune response will swing into action and fight off the disease, or prevent serious complications.

You can be vaccinated for whooping cough in your third trimester or pregnancy. This helps pass on your immunity against whooping cough to your baby.

You can also be vaccinated against influenza (the ‘flu’) when pregnant. This is recommended at any stage of pregnancy, but should happen before the ‘flu’ season starts. Your antibodies to the flu vaccine are also passed on to your baby.

Your baby’s first vaccines are given at birth, then at 6 weeks, 4 months and 6 months of age. Other vaccines and boosters are given over the first few years of life.

Diet and supplements

Taking antibiotics kills some of the good gut bacteria that are important for immunity. Some people think that probiotics can boost immunity after they have had antibiotics. Probiotics are safe for women to use in late pregnancy and after the baby is born. However, it is not clear if probiotics are useful for children or adults. Talk to your doctor before giving probiotics to your baby.

Some people think that probiotics can boost immunity after they have had antibiotics. Probiotics are safe for women to use in late pregnancy and after the baby is born. However, it is not clear if probiotics are useful for children or adults. Talk to your doctor before giving probiotics to your baby.

In most cases, breast milk and formula provide all the vitamins and minerals your baby needs. Giving extra vitamins is not recommended for babies.

Once your baby starts on solids, a range of fresh foods should be enough to keep their immune system healthy. This can include different types of pureed vegetables and fruits. Try to keep breastfeeding at the same time as starting solid food.

Speak to a maternal child health nurse

Call Pregnancy, Birth and Baby to speak to a maternal child health nurse on 1800 882 436 or video call. Available 7am to midnight (AET), 7 days a week.

Sources:

Australian Government Department of Health (Influenza vaccination in pregnancy)Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content.

Last reviewed: May 2022

Back To Top

Related pages

- Immunisation and vaccinations for your child

- Immunisation or vaccination - what's the difference?

- Vaccinations and pregnancy

- Breastfeeding your baby

Need more information?

COVID-19 vaccination, pregnancy and breastfeeding

COVID-19 vaccination is now available in Australia, but if you are pregnant or breastfeeding, you might be wondering whether it is safe for you to get vaccinated.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Breastfeeding Tips and Videos | Tresillian

Find videos and top breastfeeding tips to answer your questions, including how long to breastfeed, milk supply tips, and weaning your baby.

Read more on Tresillian website

Vaccines: how they stop infectious disease | Raising Children Network

Vaccines help the immune system recognise viruses and bacteria and destroy them quickly. This is how vaccines protect your family from infectious diseases.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Pregnancy and breastfeeding with hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that can damage the liver. It can be passed from mother to baby during birth so pregnant women are routinely tested.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Immunisation and vaccinations for your child

Immunisation is a simple, safe and effective way of protecting children against certain diseases. Discover more about childhood vaccinations.

Discover more about childhood vaccinations.

Read more on Pregnancy, Birth & Baby website

Breast feeding your baby - MyDr.com.au

Breast milk has long been known as the ideal food for babies and infants. Major health organisations recommend that women breast feed their babies exclusively until they are 6 months old, and continue breast feeding, along with solids, until they are 12 months old or more. Breast milk has many benefits.

Read more on myDr website

Getting vaccinated | Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care

Find out what to do when booking your appointment, and what to expect at your vaccination visit.

Read more on Department of Health and Aged Care website

Immunisation during pregnancy - Immunisation Coalition

Immunisation during pregnancy is vital to protect the mother and unborn child. We recommend pregnant women receive vaccines for whooping cough, influenza and now COVID-19.

We recommend pregnant women receive vaccines for whooping cough, influenza and now COVID-19.

Read more on Immunisation Coalition website

Who can be immunised? | Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care

Most people can be immunised, except for people with certain medical conditions and people who are severely allergic (anaphylactic) to vaccine ingredients.

Read more on Department of Health and Aged Care website

HIV and AIDS in children & teenagers | Raising Children Network

AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) is caused by HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). HIV and AIDS are very rare conditions in Australian children.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Disclaimer

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Need further advice or guidance from our maternal child health nurses?

1800 882 436

Video call

- Contact us

- About us

- A-Z topics

- Symptom Checker

- Service Finder

- Subscribe to newsletters

- Sign in

- Linking to us

- Information partners

- Terms of use

- Privacy

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby is funded by the Australian Government and operated by Healthdirect Australia.

Pregnancy, Birth and Baby’s information and advice are developed and managed within a rigorous clinical governance framework.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

This information is for your general information and use only and is not intended to be used as medical advice and should not be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any medical condition, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes.

The information is not a substitute for independent professional advice and should not be used as an alternative to professional health care. If you have a particular medical problem, please consult a healthcare professional.

Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, this publication or any part of it may not be reproduced, altered, adapted, stored and/or distributed in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Healthdirect Australia.

Support this browser is being discontinued for Pregnancy, Birth and Baby

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

Infant Immune Systems Are Stronger Than You Think

New study may help explain why infants are less affected by COVID than adults

December 10, 2021

Share this page

As any parent knows, infants are prone to getting respiratory infections.

But a new study shows that the infant immune system is stronger than most people think and beats adults at fighting off new pathogens.

The infant immune system has a reputation for being weak and underdeveloped when compared to the adult immune system, but the comparison isn’t quite fair, says Donna Farber, PhD, professor of microbiology & immunology and the George H. Humphreys II Professor of Surgical Sciences at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Watching T cells react to flu antigens helped the researchers identify why naive T cells from infant mice (shown above) responded faster and more robustly to the pathogen than the same cells from adult mice. The colors in the images represent different molecules involved in T cell activation. Images from the Farber laboratory/Columbia University Irving Medical Center.Babies do get a lot of respiratory illnesses from viruses, like influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, compared to adults. But unlike adults, babies are seeing these viruses for the first time. “Adults don’t get sick as often because we’ve recorded memories of these viruse, and the memories protect us,” Farber says, “whereas everything the baby encounters is new to them. ”

”

In the new study, Farber and colleagues leveled the playing field and only tested the immune system’s ability to respond to a new pathogen, essentially eliminating any contribution from immunological memories.

For the head-to-head comparison, the researchers collected naïve T cells—immune cells that have never encountered a pathogen—from both infant and adult mice. The cells were placed into an adult mouse infected with a virus.

In the competition to eradicate the virus, the infant T cells won handily: Naïve T cells from infant mice detect lower levels of the virus than adult cells and the infant cells proliferated faster and traveled in greater numbers to the site of infection, rapidly building a strong defense against the virus. A laboratory comparison found similar enhancements among human infant compared to adult T cells.

“We were looking at naïve T cells that have never been activated, so it was a surprise that they behaved differently based on age,” Farber says. “What this is saying is that the infant’s immune system is robust, it's efficient, and it can get rid of pathogens in early life. In some ways, it may be even better than the adult immune system, since it’s designed to respond to a multitude of new pathogens.”

“What this is saying is that the infant’s immune system is robust, it's efficient, and it can get rid of pathogens in early life. In some ways, it may be even better than the adult immune system, since it’s designed to respond to a multitude of new pathogens.”

That appears to be playing out in the case of COVID. “SARS-CoV-2 is new to absolutely everybody, so we’re now seeing a natural, side-by-side comparison of the adult and infant immune system,” Farber says. “And the kids are doing much better. Adults faced with a novel pathogen are slower to react. That gives the virus a chance to replicate more, and that’s when you get sick.”

The findings also help explain why vaccines are particularly effective in childhood, when T cells are very robust. “That is the time to get vaccines and you shouldn't worry about getting multiple vaccines in that window,” Farber says. “Any child living in the world, particularly before we started wearing masks, is exposed to a huge number of new antigens every day. They’re already handling multiple exposures.”

They’re already handling multiple exposures.”

The study could lead to better vaccine designs for children.

“Most vaccine formulations and doses are the same for all ages, but understanding the distinct immune responses in childhood suggests we can use lower doses for children and could help us design vaccines that are more effective for this age group,” Farber says.

References

More information

The paper, titled "Infant T cells are developmentally adapted for robust lung immune responses through enhanced T cell receptor signaling," was published Dec. 10 in Science Immunology.

Donna Farber also is chief of the Division of Surgical Sciences in the Department of Surgery, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, and principal investigator at the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology.

All authors (all from Columbia University unless noted): Puspa Thapa, Rebecca S. Guyer, Alexander Y. Yang, Christopher A. Parks, Todd M. Brusko (University of Florida), Maigan Brusko (University of Florida), Thomas J. Connors, and Donna L. Farber.

Brusko (University of Florida), Maigan Brusko (University of Florida), Thomas J. Connors, and Donna L. Farber.

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH grants AI100119, AI106697, K23 AI141686, and AI42288) and the Helmsley Charitable Trust. Studies were performed in the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology’s Flow Cytometry Core, supported by NIH grants S10RR027050 and S10OD020056, and the Columbia Stem Cell Initiative’s Flow Core, supported in part by NIH grant S10OD026845.

The authors declared no competing interests.

⚕ Do newborns have immunity?👼

When a baby is born, parents immediately worry about his health. One of the most common questions of young mothers and fathers is “Does a newborn have immunity?” It is answered by the pediatricians of the Pulse family clinic.

- Immune system is a system of organs and structures that is responsible for protecting the body from extraneous factors - bacteria, viruses, etc.

;

; - Immunity is the actual reaction of the immune system, that is, the response to stimuli.

The immune system itself is formed in a child in the womb of the mother. But immunity develops during the first years of life. This is because the baby's immune system has not yet been trained in all the subtleties.

Peculiarities of newborn immunity

- During 9 months of pregnancy, a large number of immunosuppressants are present in the baby's blood. These cells specifically weaken the child's own immunity so that its development does not conflict with the mother's body.

- Immediately after birth, a sterile baby faces the outside world. Passive protection in the first 29 days of life is given to him by IgG immunoglobulins, which he received from his mother. These are antibodies against all pathogens that the mother has encountered.

In the course of life, the amount of maternal antibodies in the baby's body decreases, and completely disappears by the 6th month.

In the course of life, the amount of maternal antibodies in the baby's body decreases, and completely disappears by the 6th month. - If a mother feeds a child with her own milk, then she gives him additional protection - IgA. They protect the mucous membranes from external attack by microorganisms. This applies to the nasopharynx, intestines, eyes and the like.

- Gradually, the baby's body adapts to the new world and forms its own immune response, producing its own immune system cells. A smooth transition occurs in the first year of life.

There are three critical periods for the formation of immunity

- The first month. During this period, the cells of the immune system are learning, so the baby's body is very vulnerable. It is protected only by maternal antibodies;

- 6 months.

At half a year, almost all maternal antibodies disappear, and the baby begins to get sick;

At half a year, almost all maternal antibodies disappear, and the baby begins to get sick; - 2 years. At this time, the baby actively gets acquainted with the world, goes to children's groups. Immunity trains, SARS and a runny nose occur.

The final immune protection in a child will be formed only in adolescence - at the age of 15, and work all his life.

We remind you that the best way to train the immune system and protect against dangerous diseases is vaccination. And advice on strengthening children's immunity can be provided by pediatricians of the Pulse family clinic. Looking forward to seeing your kids!

Features of the immune system of newborns

Doctor of laboratory diagnostics Shulga L.P.

Centralized immuno-toxicological laboratory

The development of the body's immune system continues throughout childhood. In the process of development of the child's immune system, "critical" periods are distinguished, i.e. periods of maximum risk of developing infectious diseases associated with insufficiency of the immune system.

In the process of development of the child's immune system, "critical" periods are distinguished, i.e. periods of maximum risk of developing infectious diseases associated with insufficiency of the immune system.

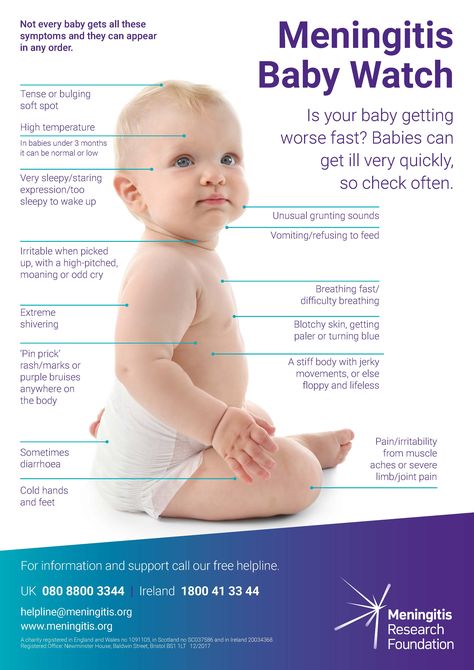

The first critical period is the neonatal period (up to 29days of life), when the child's body is protected almost exclusively by maternal antibodies obtained through the placenta and breast milk. The sensitivity of a newborn child to bacterial and viral infections during this period is very high. The group of increased risk of developing infections among newborns is made up of premature babies, and among them are small babies suffering from the most pronounced and persistent immunological defects.

The second critical period (4-6 months of life) is characterized by the loss of antibodies received from the mother. The ability to produce own antibodies during this period is limited by the weak synthesis of only immunoglobulins M, while immunoglobulins G are the main protective antibodies. Insufficiency of local mucosal protection is associated with a later accumulation of secretory immunoglobulin A. In this regard, the child's sensitivity to many airborne and intestinal infections during this period is very high.

Insufficiency of local mucosal protection is associated with a later accumulation of secretory immunoglobulin A. In this regard, the child's sensitivity to many airborne and intestinal infections during this period is very high.

The third critical period (the 2nd year of life), when the child's contacts with the outside world and infectious agents are significantly expanded.

The fourth critical period (6-7th years of life), when the absolute and relative number of lymphocytes in the child's blood decreases.

The fifth critical period is adolescence (in girls from 12-13 years old, in boys from 14-15 years old), when the growth spurt is combined with a relative decrease in the mass of lymphoid organs, and the onset of secretion of sex hormones causes suppression of cellular mechanisms of immunity

In each of these periods, the child's immune system is characterized by a number of features.

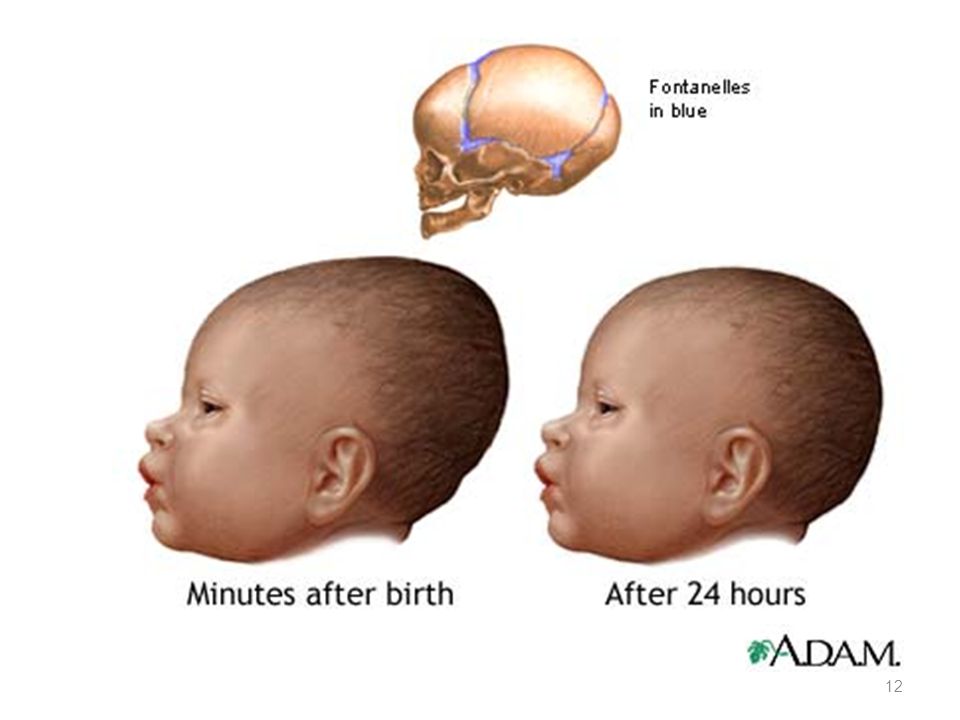

At birth, neutrophils predominate in the baby's blood. By the end of the first week of life, the number of neutrophils and lymphocytes levels off - the so-called "first cross" - with a subsequent increase in the number of lymphocytes, which in the next 4-5 years of life remain the predominant cells among the child's blood leukocytes. The "second crossover" occurs in a child aged 6-7 years, when the absolute and relative number of lymphocytes decreases and the leukocyte formula takes on the form characteristic of adults. When evaluating the data of a clinical blood test in children, these "crosses" must be taken into account.

The "second crossover" occurs in a child aged 6-7 years, when the absolute and relative number of lymphocytes decreases and the leukocyte formula takes on the form characteristic of adults. When evaluating the data of a clinical blood test in children, these "crosses" must be taken into account.

An increased number of granulocytes in the blood of newborns to some extent compensates for the insufficient activity of their protective functions. The absolute number of blood monocytes in newborns is higher than in older children, but they also have a low protective activity.

The content of the antibacterial enzyme lysozyme in the blood serum of a newborn exceeds the level of maternal blood already at birth, it increases during the first days of life, and by the 7-8th day of life it somewhat decreases and reaches the level of adults. And in the lacrimal fluid of newborns, the content of lysozyme is lower than in adults, which is the reason for the increased frequency of conjunctivitis in newborns.

In newborns, all the main mechanisms of nonspecific defense of the body against pathogenic bacteria and viruses are sharply weakened, which explains the high sensitivity of newborns and children of the first year of life to bacterial and viral infections. Defects in phagocytic cells are most pronounced in premature newborns and children with intrauterine growth retardation. These children are characterized by a protracted course of infections (for example, pneumonia) and the low effectiveness of antibiotic therapy.

After birth, the child's immune system receives a strong stimulus for rapid development in the form of a stream of foreign (microbial) antigens entering the child's body through the skin, mucous membranes of the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, actively populated by microflora in the first hours after birth. Microorganisms penetrating through the gastrointestinal tract are the main engines of the maturation of the entire immune system of the child. The rapid development of the immune system is manifested by an increase in the mass of lymph nodes, which are populated by T- and B-lymphocytes. After the birth of a child, the absolute number of lymphocytes in the blood rises sharply already at the 1st week of life (the first cross in the white blood formula). Physiological age-related lymphocytosis persists for 5-6 years of life and can be considered as compensatory.

The rapid development of the immune system is manifested by an increase in the mass of lymph nodes, which are populated by T- and B-lymphocytes. After the birth of a child, the absolute number of lymphocytes in the blood rises sharply already at the 1st week of life (the first cross in the white blood formula). Physiological age-related lymphocytosis persists for 5-6 years of life and can be considered as compensatory.

The relative number of T-lymphocytes in newborns is lower than in adults, but due to age-related lymphocytosis, the absolute number of T-lymphocytes in the blood of newborns is even higher than in adults. Features of T-lymphocytes of newborns are associated with the release of immature precursors into the bloodstream. The weakness of cellular defense mechanisms makes children particularly susceptible to viral and fungal infections, protection from which requires the participation of functionally complete T-lymphocytes.

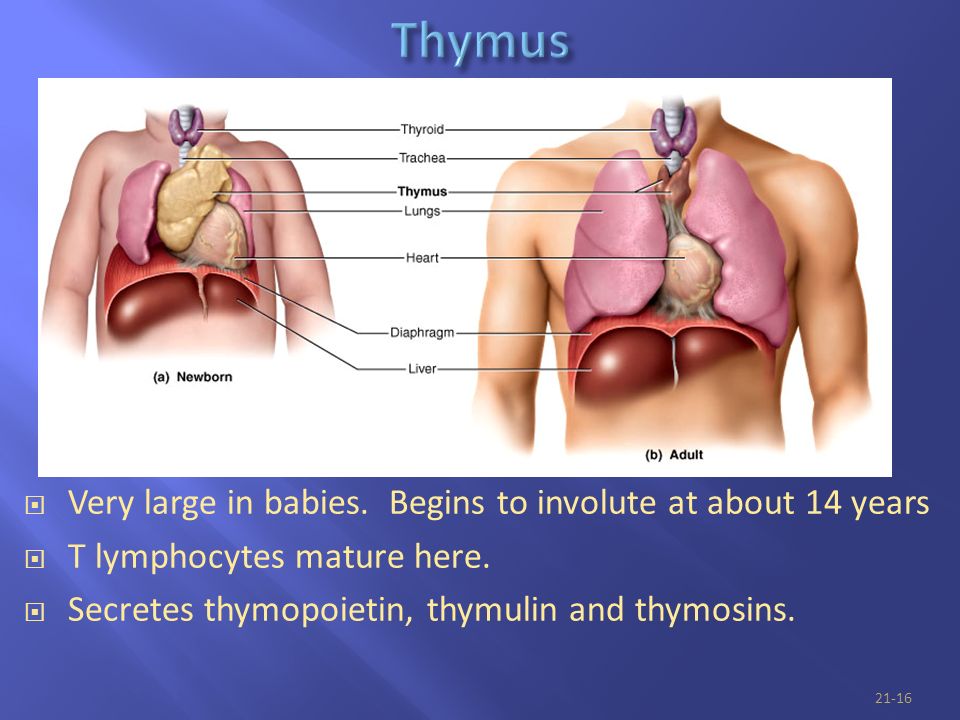

In a newborn, the thymus is fully formed and reaches its maximum size during the first year of life. The rapid increase in thymus mass in the first 3 months of life continues at a slower pace until the age of 6, after which the thymus mass begins to decline. From the age of two, the production of T-lymphocytes also begins to decline. The process of age-related involution of the thymus accelerates in adolescence. During the first half of life, true thymic tissue is gradually replaced by adipose and connective tissue. From this it follows that the thymus manages to carry out its main function of the formation of T-lymphocytes in the first years of life.

The rapid increase in thymus mass in the first 3 months of life continues at a slower pace until the age of 6, after which the thymus mass begins to decline. From the age of two, the production of T-lymphocytes also begins to decline. The process of age-related involution of the thymus accelerates in adolescence. During the first half of life, true thymic tissue is gradually replaced by adipose and connective tissue. From this it follows that the thymus manages to carry out its main function of the formation of T-lymphocytes in the first years of life.

Immunoglobulin A in the blood of newborns is either absent or present in a small amount (0.01 g/l), and only at a much older age reaches the level of adults (after 10-12 years). Secretory immunoglobulins A are absent in newborns, and appear in secrets after the 3rd month of life.

The newborn's body defense reserve is associated with breastfeeding. With mother's milk, ready-made antibacterial and antiviral antibodies enter the child's body - secretory immunoglobulins A and G. Secretory antibodies go directly to the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts and protect these mucous membranes of the child from infections. Due to the presence of special receptors on the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract of the newborn, immunoglobulins G penetrate from the gastrointestinal tract of the child into his bloodstream, where they replenish the supply of maternal antibodies that previously entered through the placenta. An increase in the reserves of the immune system and the prevention of infections in newborns is achieved by breastfeeding. Human milk contains not only a complex of nutritional components necessary for a child, but also the most important factors of nonspecific protection and products of a specific immune response in the form of class A secretory immunoglobulins. Secretory IgA supplied with breast milk improves local protection of the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal, respiratory and even urinary tract of the child. Breastfeeding through the introduction of ready-made antibacterial and antiviral antibodies of the SIgA class significantly increases the resistance of children to intestinal infections, respiratory infections, and otitis media.

Secretory antibodies go directly to the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts and protect these mucous membranes of the child from infections. Due to the presence of special receptors on the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract of the newborn, immunoglobulins G penetrate from the gastrointestinal tract of the child into his bloodstream, where they replenish the supply of maternal antibodies that previously entered through the placenta. An increase in the reserves of the immune system and the prevention of infections in newborns is achieved by breastfeeding. Human milk contains not only a complex of nutritional components necessary for a child, but also the most important factors of nonspecific protection and products of a specific immune response in the form of class A secretory immunoglobulins. Secretory IgA supplied with breast milk improves local protection of the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal, respiratory and even urinary tract of the child. Breastfeeding through the introduction of ready-made antibacterial and antiviral antibodies of the SIgA class significantly increases the resistance of children to intestinal infections, respiratory infections, and otitis media.