Htn in pregnancy

High Blood Pressure During Pregnancy

- What are high blood pressure complications during pregnancy?

- What should I do if I have high blood pressure before, during, or after pregnancy?

- What are types of high blood pressure conditions before, during, and after pregnancy?

- More Information

Some women have high blood pressure during pregnancy. This can put the mother and her baby at risk for problems during the pregnancy. High blood pressure can also cause problems during and after delivery.1,2 The good news is that high blood pressure is preventable and treatable.

High blood pressure, also called hypertension, is very common. In the United States, high blood pressure happens in 1 in every 12 to 17 pregnancies among women ages 20 to 44.3

High blood pressure in pregnancy has become more common. However, with good blood pressure control, you and your baby are more likely to stay healthy.

The most important thing to do is talk with your health care team about any blood pressure problems so you can get the right treatment and control your blood pressure—before you get pregnant. Getting treatment for high blood pressure is important before, during, and after pregnancy.

What are high blood pressure complications during pregnancy?

Complications from high blood pressure for the mother and infant can include the following:

- For the mother: preeclampsiaexternal icon, eclampsiaexternal icon, stroke, the need for labor induction (giving medicine to start labor to give birth), and placental abruption (the placenta separating from the wall of the uterus).1,4,5

- For the baby: preterm delivery (birth that happens before 37 weeks of pregnancy) and low birth weight (when a baby is born weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces).1,6 The mother’s high blood pressure makes it more difficult for the baby to get enough oxygen and nutrients to grow, so the mother may have to deliver the baby early.

Discuss blood pressure problems with your health care team before, during, and after pregnancy.

Learn what to do if you have high blood pressure before, during, or after pregnancy.

What should I do if I have high blood pressure before, during, or after pregnancy?

Before Pregnancy

- Make a plan for pregnancy and talk with your doctor or health care team about the following:

- Any health problems you have or had and any medicines you are taking. If you are planning to become pregnant, talk to your doctor.7 Your doctor or health care team can help you find medicines that are safe to take during pregnancy.

- Ways to keep a healthy weight through healthy eating and regular physical activity.1,7

During Pregnancy

- Get early and regular prenatal careexternal icon. Go to every appointment with your doctor or health care professional.

- Talk to your doctor about any medicines you take and which ones are safe.

Do not stop or start taking any type of medicine, including over-the-counter medicines, without first talking with your doctor.7

Do not stop or start taking any type of medicine, including over-the-counter medicines, without first talking with your doctor.7 - Keep track of your blood pressure at home with a home blood pressure monitorexternal icon. Contact your doctor if your blood pressure is higher than usual or if you have symptoms of preeclampsia. Talk to your doctor or insurance company about getting a home monitor.

- Continue to choose healthy foods and keep a healthy weight.8

After Pregnancy

- Pay attention to how you feel after you give birth. If you had high blood pressure during pregnancy, you have a higher risk for stroke and other problems after delivery. Tell your doctor or call 9-1-1 right away if you have symptoms of preeclampsia after delivery. You might need emergency medical care.9,10

What are types of high blood pressure conditions before, during, and after pregnancy?

Your doctor or nurse should look for these conditions before, during, and after pregnancy:1,11

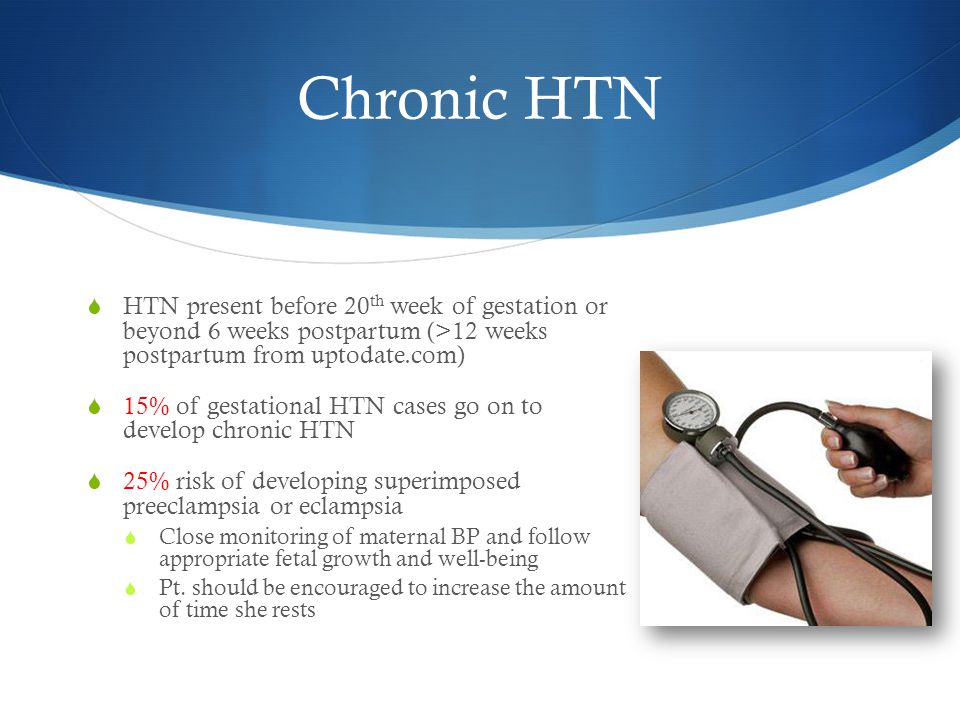

Chronic Hypertension

Chronic hypertension means having high blood pressure* before you get pregnant or before 20 weeks of pregnancy. 1 Women who have chronic hypertension can also get preeclampsia in the second or third trimester of pregnancy.1

1 Women who have chronic hypertension can also get preeclampsia in the second or third trimester of pregnancy.1

Gestational Hypertension

This condition happens when you only have high blood pressure* during pregnancy and do not have protein in your urine or other heart or kidney problems. It is typically diagnosed after 20 weeks of pregnancy or close to delivery. Gestational hypertension usually goes away after you give birth. However, some women with gestational hypertension have a higher risk of developing chronic hypertension in the future.1,12

Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Preeclampsia happens when a woman who previously had normal blood pressure suddenly develops high blood pressure* and protein in her urine or other problems after 20 weeks of pregnancy. Women who have chronic hypertension can also get preeclampsia.

Preeclampsia happens in about 1 in 25 pregnancies in the United States.1,13 Some women with preeclampsia can develop seizures. This is called eclampsia, which is a medical emergency.1,11

This is called eclampsia, which is a medical emergency.1,11

Symptoms of preeclampsia include:

- A headache that will not go away

- Changes in vision, including blurry vision, seeing spots, or having changes in eyesight

- Pain in the upper stomach area

- Nausea or vomiting

- Swelling of the face or hands

- Sudden weight gain

- Trouble breathing

Some women have no symptoms of preeclampsia, which is why it is important to visit your health care team regularly, especially during pregnancy.

You are more at risk for preeclampsia if:1

- This is the first time you have given birth.

- You had preeclampsia during a previous pregnancy.

- You have chronic (long-term) high blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, or both.

- You have a history of thrombophilia (a condition that increases risk of blood clots).

- You are pregnant with multiple babies (such as twins or triplets).

- You became pregnant using in vitro fertilization.

- You have a family history of preeclampsia.

- You have type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

- You have obesity.

- You have lupus (an autoimmune disease).

- You are older than 40.

In rare cases, preeclampsia can happen after you have given birth. This is a serious medical condition known as postpartum preeclampsia. It can happen in women without any history of preeclampsia during pregnancy.14 The symptoms for postpartum preeclampsia are similar to the symptoms of preeclampsiaexternal icon. Postpartum preeclampsia is typically diagnosed within 48 hours after delivery but can happen up to 6 weeks later.9

Tell your health care provider or call 9-1-1 right away if you have symptoms of postpartum preeclampsia. You might need emergency medical care.9,10

*In November 2017, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) updated the definition of chronic stage 2 hypertension to mean having blood pressure at or above 140/90 mmHg. 15 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendations on hypertension in pregnancy predate the 2017 ACC/AHA’s guideline and definition of hypertension and stage 2 hypertension.

15 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendations on hypertension in pregnancy predate the 2017 ACC/AHA’s guideline and definition of hypertension and stage 2 hypertension.

More Information

For more information about high blood pressure during pregnancy, see the following resources:

- Pregnancy Complications (CDC)

- Treating for Two: Medicine and Pregnancy (CDC)

- Heart Health and Pregnancyexternal icon (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute)

- Preeclampsia and Eclampsiaexternal icon (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development)

- Pregnancy Complicationsexternal icon (Office on Women’s Health)

- Preeclampsia and High Blood Pressure During Pregnancyexternal icon (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists)

- High Blood Pressure During Pregnancyexternal icon (March of Dimes)

- Preeclampsia Foundationexternal icon

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy.

Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancyexternal icon. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–31.

Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancyexternal icon. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–31. - Hutcheon JA, Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and the other hypertensive disorders of pregnancyexternal icon. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(4):391–403.

- Bateman BT, Shaw KM, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM, Seely EW, Hernandez-Diaz S. Hypertension in women of reproductive age in the United States: NHANES 1999-2008external icon. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e36171.

- Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United Statesexternal icon. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1029–36.

- Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Bruce FC, et al. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now?external icon J Womens Health (Larchmt).

2014;23(1):3–9.

2014;23(1):3–9. - Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Fraser A, Nelson SM, Lawlor DA. Associations of blood pressure change in pregnancy with fetal growth and gestational age at delivery: findings from a prospective cohortexternal icon. 2014;64(1):36–44.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treating for two: medicine and pregnancy. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- Liu Y, Croft JB, Wheaton AG, Kanny D, Cunningham TJ, Lu H, et al. Clustering of five health-related behaviors for chronic disease prevention among adults, United States, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:160054.

- Mayo Clinic. Postpartum preeclampsiaexternal icon. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- Matthys LA, Coppage KH, Lambers DS, Barton JR, Sibai BM. Delayed postpartum preeclampsia: an experience of 151 casesexternal icon. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1464–6.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data on selected pregnancy complications in the United States. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricans and Gynecologists. Preeclampsia and high blood pressure during pregnancyexternal icon. Accessed May 22, 2019.

- S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for preeclampsia: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statementexternal icon. JAMA. 2017;317(16):1661–67.

- Bigelow CA, Pereira GA, Warmsley A, Cohen J, Getrajdman C, Moshier E, et al. Risk factors for new-onset late postpartum preeclampsia in women without a history of preeclampsiaexternal icon. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(4):338.e1–8.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelinesexternal icon. 2017;71(6):e13–115.

Hypertension In Pregnancy - StatPearls

Richard K. Luger; Benjamin P. Kight.

Luger; Benjamin P. Kight.

Last Update: October 3, 2022.

Continuing Education Activity

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including chronic hypertension with or without superimposed pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia with or without severe feature, Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes and Low Platelet Count (HELLP) syndrome or eclampsia present a significant risk of morbidity to both mother and fetus. Although appropriate prenatal care with close observation to detect signs of end organ damage and prompt delivery to reduce or avoid adverse effects have produced reduced morbidity and mortality, morbidity and mortality still do occur. While hypertension itself presents concerns during pregnancy, adverse effects from progression to pre-eclampsia/eclampsia along with HELLP syndrome present the primary concern. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of hypertension in pregnancy and highlights the role of an interprofessional team in evaluating and improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe hypertension in pregnancy,

Explain the causes of hypertension in pregnancy.

Outline the management strategies for the different causes of hypertension in pregnancy.

Summarize a structured interprofessional team approach to provide effective care to and appropriate surveillance of pregnant patients with hypertension.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including chronic hypertension, with or without superimposed pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, gestational hypertension, HELLP syndrome, preeclampsia with or without severe features or eclampsia present a significant risk of morbidity to both mother and fetus. Although appropriate prenatal care with close observation to detect signs of pre-eclampsia and prompt delivery to reduce or avoid adverse effects have produced reduced morbidity and mortality, they still exist. While hypertension itself presents concerns during pregnancy, adverse effects from progression to pre-eclampsia/eclampsia present the primary concern. [1][2][3]

While hypertension itself presents concerns during pregnancy, adverse effects from progression to pre-eclampsia/eclampsia present the primary concern. [1][2][3]

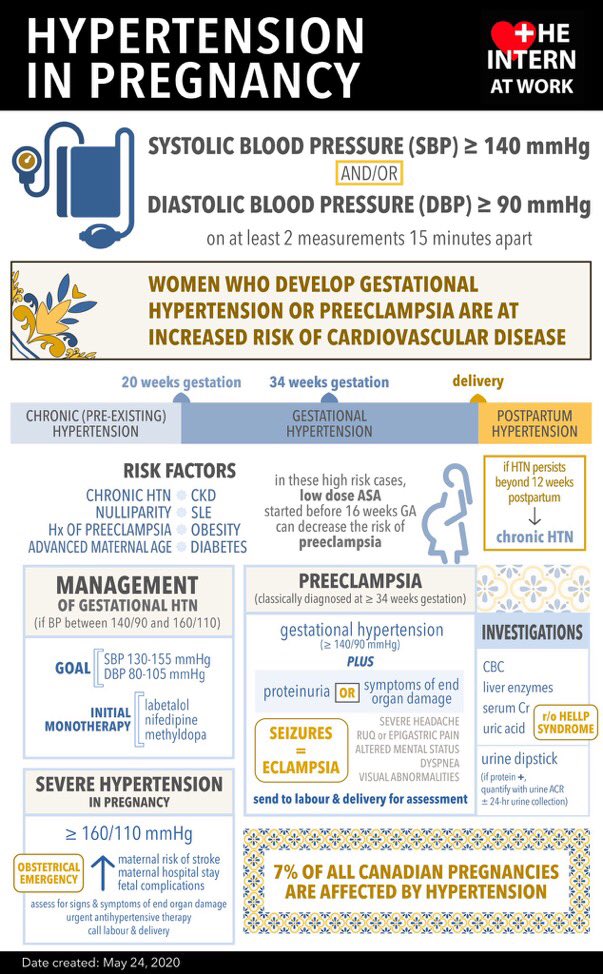

Etiology

Conditions that reduce uteroplacental blood flow and vascular insufficiency including pre-existing hypertension, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, OSA, thrombophilia, and autoimmune disease have demonstrated an increased risk for hypertensive disease in pregnancy. Additionally, women with a previous history of preeclampsia, previous history of HELLP syndrome, twin or other multiple pregnancies, BMI >30, autoimmune disease, are women who are more than 35 years of age, are first-time mothers, or have a mother or sister who has had gestational hypertension have been shown to be at higher risk for developing gestational hypertension and are at an elevated risk of progressing to pre-eclampsia.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Hypertensive disorders complicate between 5% and 10% of all pregnancies. Pre-eclampsia complicates 2-8% of all pregnancies worldwide. In the US, the rate of pre-eclampsia increaased 25% between 1987-2004. The incidence of hypertension is increasing due to changes in maternal demographics (e.g. advancing maternal age, increased pre-pregnancy weight). Eclampsia, however, has declined due to improved prenatal care, and the increased use of antenatal therapies (e.g. blood pressure control, magnesium seizure prophylaxis) as well as timely delivery by induction of labor or cesarean section which serve as a cure for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia.[7][8]

In the US, the rate of pre-eclampsia increaased 25% between 1987-2004. The incidence of hypertension is increasing due to changes in maternal demographics (e.g. advancing maternal age, increased pre-pregnancy weight). Eclampsia, however, has declined due to improved prenatal care, and the increased use of antenatal therapies (e.g. blood pressure control, magnesium seizure prophylaxis) as well as timely delivery by induction of labor or cesarean section which serve as a cure for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia.[7][8]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of hypertension in pregnancy is not completely understood. Current research demonstrates that improper trophoblast differentiation during endothelial invasion due to abnormal regulation and/or production of cytokines, adhesion molecules, major histocompatibility complex molecules, and metalloproteinases plays a key role in the development of a gestational hypertensive disease. Abnormal regulation and/or production of these molecules leads to abnormal development and remodeling of spiral arteries in the deep myometrial tissues. This leads to placental hypoperfusion and ischemia. More recent research shows role of antiangiogenic factors that are released by placental tissue cause systemic endothelial dysfunction which can result in systemic hypertension. Organ hypoperfusion from endothelial dysfunction is most commonly seen in the eyes, lungs, liver, kidneys and peripheral vasculature. Overall, most experts agree underlying reason is multifactorial [9]

This leads to placental hypoperfusion and ischemia. More recent research shows role of antiangiogenic factors that are released by placental tissue cause systemic endothelial dysfunction which can result in systemic hypertension. Organ hypoperfusion from endothelial dysfunction is most commonly seen in the eyes, lungs, liver, kidneys and peripheral vasculature. Overall, most experts agree underlying reason is multifactorial [9]

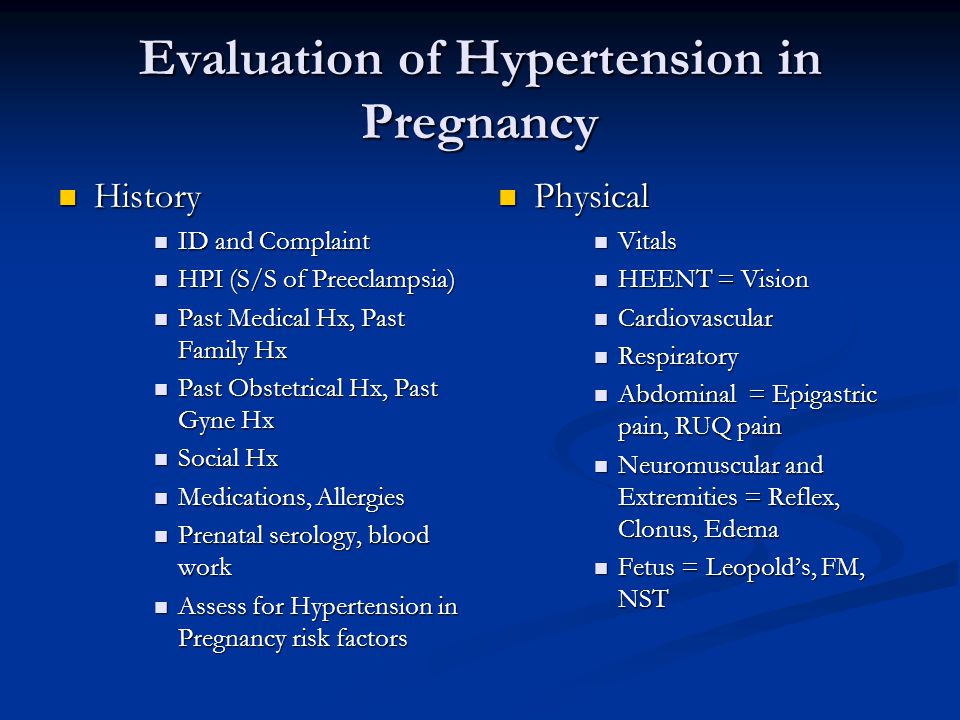

History and Physical

Physical exam findings commonly noted with both chronic and gestational hypertension are limited to systolic blood pressure above 140mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure above 90mmHg. Severe range blood pressures are above 160mmHg systolic and/or 110mmHg diastolic. An increase in edema is frequently noted in women with pre-eclampsia. Those demonstrating severe features may demonstrate cerebral symptoms (unremitting/severe headache, altered mental status), visual symptoms (scotomata, photophobia, blurred vision, or temporary blindness/visual field defect), pulmonary edema (dyspnea or rales on examination), renal impairement (water retention causing peripheral edema)or hepatic impairment (right upper quadrant pain). In HELLP syndrome malaise and right upper quadrant pain occur in up to 90% of cases. Vomiting is also common [10]

In HELLP syndrome malaise and right upper quadrant pain occur in up to 90% of cases. Vomiting is also common [10]

Evaluation

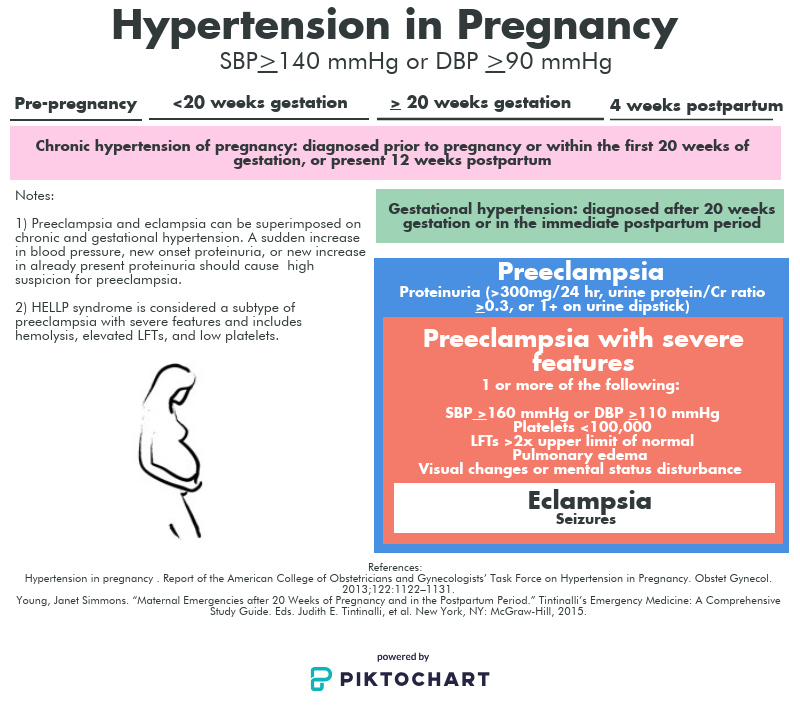

Chronic hypertension is diagnosed per ACC/AHA and ACOG guidelines as an in-office measurement with systolic blood pressure greater than 140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 90mmHg confirmed with either ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, home blood pressure monitoring, or blood pressure evaluation with serial office visits, with elevated pressures at least 4 hours apart prior to 20 weeks gestation. [11][12][13][14]

Gestational hypertension is defined per ACOG guidelines as blood pressure greater than or equal to 140mmHg systolic or 90mmHg diastolic on two separate occasions at least four hours apart after 20 weeks of pregnancy when previous blood pressure was normal. Alternatively, a patient with systolic blood pressure greater than 160mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 110mmHg can be confirmed to have gestational hypertension if they have a similar pressure after a short interval. This is in order to ensure timely antihypertensive treatment. As above, clinical symptoms are usually only noted when blood pressure is greater than 160/110 and may signify end-organ damage.

This is in order to ensure timely antihypertensive treatment. As above, clinical symptoms are usually only noted when blood pressure is greater than 160/110 and may signify end-organ damage.

Pre-eclampsia is defined per ACOG guidelines as meeting either above hypertension criteria with greater than or equal to 300mg urine protein excretion in a 24-hour period or a protein/creatinine ratio of greater than or equal to 0.3. Urine dipstick can be used if the other methods are not available and proteinuria is defined as protein reading of at least 1+.

The criteria for pre-eclampsia can also be met in the absence of proteinuria if one has new-onset hypertension with thrombocytopenia(platelets less than 100,000 x10(9)/L, renal insufficiency(double of baseline serum creatine or serum creatine >1.1mg/dL), pulmonary edema, impaired liver function (AST/ALT greater than twice upper limit of normal), or new-onset headache unresponsive to medications with no alternative cause.Pre-eclampsia can be superimposed with chronic hypertension, or as advancement along the spectrum of gestational hypertensive disease. Per ACOG guidelines, systolic blood pressure of greater than 160mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 110mmHg on two separate readings 4 hours apart or any severe range pressure that requires antihypertensive medication which by treatment guidelines is severe pressures seperated by minutes(10-30 minutes). [15]

Per ACOG guidelines, systolic blood pressure of greater than 160mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 110mmHg on two separate readings 4 hours apart or any severe range pressure that requires antihypertensive medication which by treatment guidelines is severe pressures seperated by minutes(10-30 minutes). [15]

Eclampsia refers to the pre-eclamptic patient who progresses to have generalized tonic-clonic seizures (typically intrapartum through up to 72 hours postpartum) secondary to her untreated/undertreated pre-eclampsia. Eclampsia occurs in approximately 2-3% of women with severe features who are not receiving anti-seizure prophylaxis. Up to 0.6% of women with preeclampsia without severe features develop eclampsia. Maternal complications occur in up to 70% of women experiencing eclamptic seizures with maternal morbidity as high as 14%.HELLP syndrome is a severe form of pre-eclampsia with the definition also being its namesake: hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. ACOG uses the following criteria: hemolysis as evident by LDH >600IU/L, liver injury from AST and/or AST >2 times upper limit of normal, and thrombocytopenia of less than 100,000 x 10(9)/L.

ACOG uses the following criteria: hemolysis as evident by LDH >600IU/L, liver injury from AST and/or AST >2 times upper limit of normal, and thrombocytopenia of less than 100,000 x 10(9)/L.

Treatment / Management

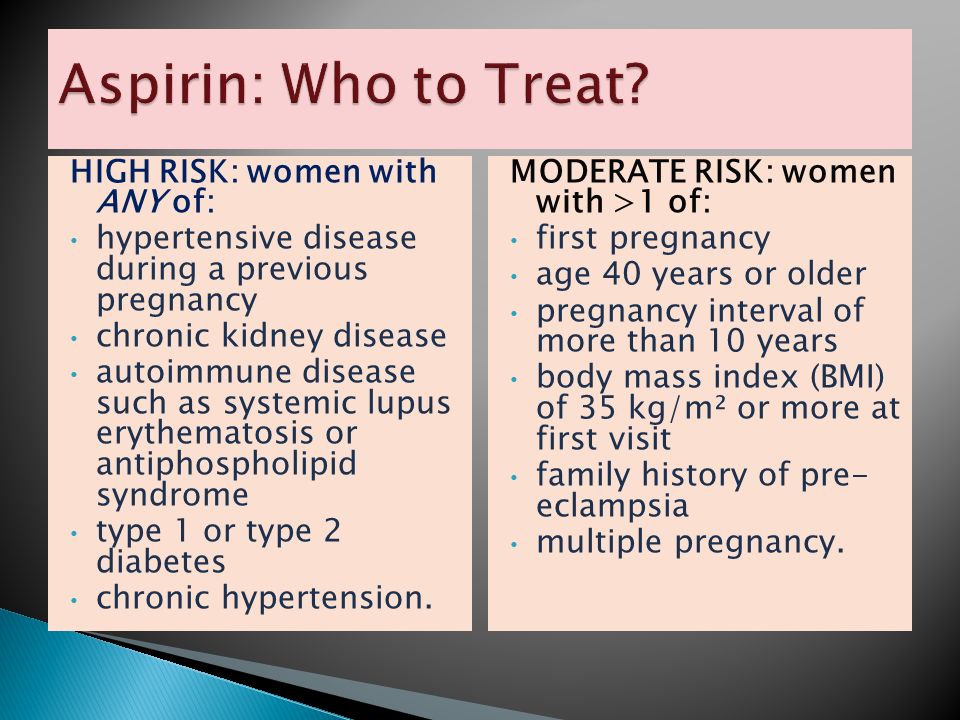

Prophylaxis with 81mg aspirin is indicated for prevention initiated between 12-28 weeks and continued until delivery when 1 high-risk factor or 2 or more moderate risk factors. High-risk factors include: history of pre-eclampsia, chronic hypertension, diabetes type 1 or 2, renal disease, autoimmune disease especially systemic lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid syndrome, or multifetal gestation. Moderate risk factors include nulliparity, more than 10 years pregnant interval, BMI >30, low socioeconomic status, African American Race, family history in 1st degree relative of preeclampsia, advanced maternal age(35+ at time of delivery), IUGR, or previous adverse pregnancy outcome. [16]

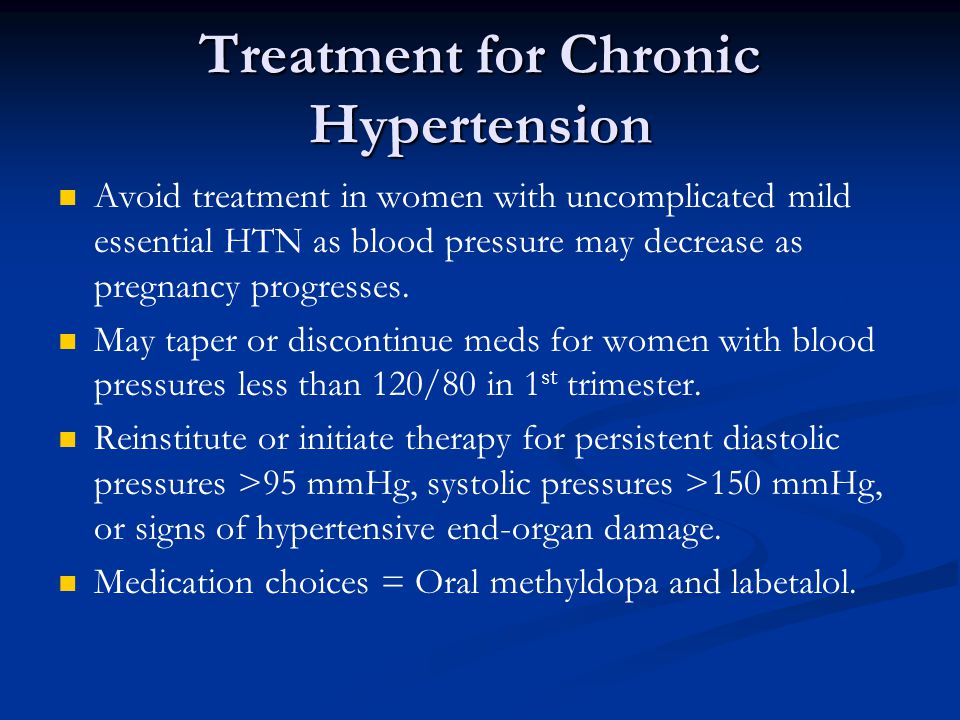

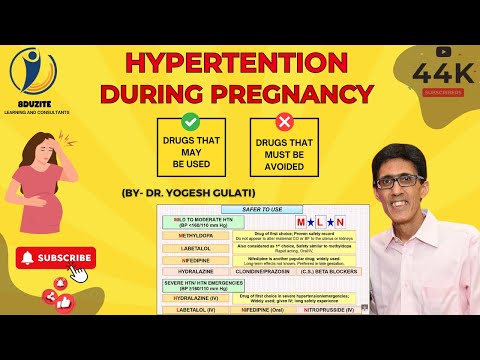

Treatment/management of gestational and chronic hypertension in pregnancy is always indicated when blood pressures are in the severe range (>160/110) last at least 15 minutes apart. ACOG does not recommend treatment with antihypertensives for mild range pressures unless they were on the medication for pre-gestational hypertension (chronic hypertension) prior to pregnancy. The treatment indication for chronic hypertension is 140/90 per ACOG. First-line therapies include labetolol, hydralazine, or nifedipine. Nifedipine is preferred if oral medication for acute oral treatment and Nifedipine or oral labetalol preferred in the outpatient setting. Thiazide diuretics can be continued if used to treat chronic hypertension before pregnancy. Hydralazine and clonidine have been used in certain circumstances, but are not commonly used in the longitudinal treatment of gestational or chronic hypertension. ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and nitroprusside, are teratogenic and thus contraindicated in pregnancy. Nitroprusside can be used as a last resort in treatment-resistant hypertension. The treatment goal is to 140-150/90-100mm Hg.

ACOG does not recommend treatment with antihypertensives for mild range pressures unless they were on the medication for pre-gestational hypertension (chronic hypertension) prior to pregnancy. The treatment indication for chronic hypertension is 140/90 per ACOG. First-line therapies include labetolol, hydralazine, or nifedipine. Nifedipine is preferred if oral medication for acute oral treatment and Nifedipine or oral labetalol preferred in the outpatient setting. Thiazide diuretics can be continued if used to treat chronic hypertension before pregnancy. Hydralazine and clonidine have been used in certain circumstances, but are not commonly used in the longitudinal treatment of gestational or chronic hypertension. ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and nitroprusside, are teratogenic and thus contraindicated in pregnancy. Nitroprusside can be used as a last resort in treatment-resistant hypertension. The treatment goal is to 140-150/90-100mm Hg. [2][17][18]

[2][17][18]

If a patient is experiencing pre-eclampsia with severe features, magnesium seizure prophylaxis is indicated until after delivery, and the appropriate diuretic response is seen. If the EGA is between 24 0/7 weeks and 33 6/7 weeks and delivery are imminent due to pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, or other concerns, antenatal steroid therapy is indicated to promote fetal lung maturity. (note - some providers will administer steroids in pregnancies up to 35 6/7 weeks EGA.) [18]

When patients are diagnosed with chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, or pre-eclampsia, increased monitoring is recommended as concern for intrauterine growth retardation, placental abruption and poor placental/umbilical blood flow are concerns. Up to twice weekly BP monitoring, frequently combined with the fetal non-stress test, amniotic fluid index evaluation, and laboratory evaluations may be indicated. Abnormal findings on any of these evaluations may indicate the need for early delivery. [18]

[18]

Definitive treatment of gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and eclampsia is delivery. Maternal sequelae of gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, and eclampsia resolve rapidly after delivery. Fetal development/maturity must be weighed against potential hypertensive/pre-eclamptic risks when determining that preterm delivery is indicated. ACOG guidelines recommending scheduled delivery timing vary depending on the diagnosis. Delivery is indicated as early as at diagnosis after 34+0/7 weeks estimated gestational age (WEGA) in patients with pre-eclampsia with severe features or immediately if unstable maternal or fetal condition. Patients with gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia without severe features might safely delay delivery until 37+0/7 WEGA or time of diagnosis if after 37+0/7 WEGA with reassuring antepartum testing. Induction for chronic hypertension is recommended from 38 0/7 to 39 6/7 weeks gestation. [18][18]

Differential Diagnosis

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Aortic coarctation

Cushing syndrome

Eclampsia

Glomerulonephritis

Hydatiform mole

Conn syndrome

Hyperthyroidism

Malignant hypertension

Complications

Eclamptic seizures

Intracranial hemorrhage

Pulmonary edema

Renal failure

Coagulopathy

Hemolysis

Liver injury

Thrombocytopenia

Intra-uterine growth restriction

Oligohydramnios

Placental abruption

Nonreassuring fetal status

[18]

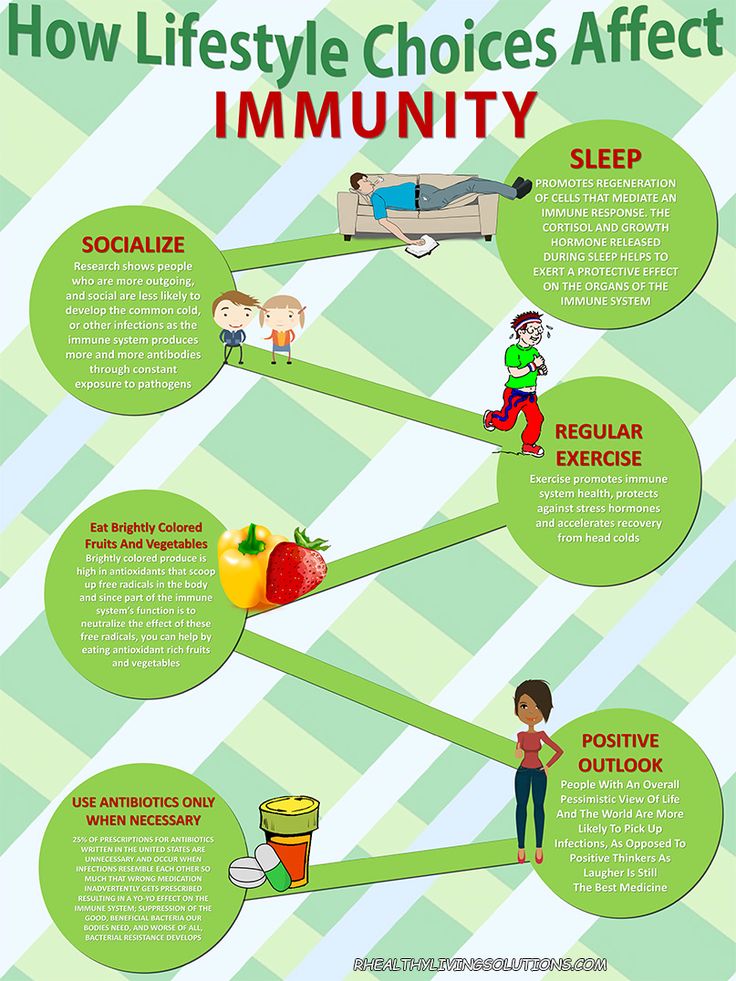

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of hypertension in pregnancy is best done in an interprofessional team that consists of a cardiologist, obstetrician, dietitian, physical therapist, and nurse. The key is to prevent hypertension in the first place. While there is no one absolute way to prevent hypertension during pregnancy, it should encourage the patient to change lifestyle and become more physically active. The patient should eat healthy and avoid excess gain in weight. Regular follow up with the obstetrician is recommended and the patient should be taught how to monitor blood pressure at home. Smoking and alcohol should be avoided and the patient should try and avoid eating too many sugary foods. [14][19](Level V)

The key is to prevent hypertension in the first place. While there is no one absolute way to prevent hypertension during pregnancy, it should encourage the patient to change lifestyle and become more physically active. The patient should eat healthy and avoid excess gain in weight. Regular follow up with the obstetrician is recommended and the patient should be taught how to monitor blood pressure at home. Smoking and alcohol should be avoided and the patient should try and avoid eating too many sugary foods. [14][19](Level V)

Outcomes

Development of hypertension during pregnancy is associated with high maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. In the US, hypertension during pregnancy results in maternal mortality rates of 2-7% each year. Transient hypertension during pregnancy can lead to chronic hypertension development after pregnancy. Data also indicate that hypertension during pregnancy is associated with fetal growth restriction and placental abruption. [20][4](Level V)

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Fisher SC, Van Zutphen AR, Werler MM, Romitti PA, Cunniff C, Browne ML., National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Maternal antihypertensive medication use and selected birth defects in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Birth Defects Res. 2018 Nov 15;110(19):1433-1442. [PubMed: 30260586]

- 2.

Spiro L, Scemons D. Management of Chronic and Gestational Hypertension of Pregnancy: A Guide for Primary Care Nurse Practitioners. Open Nurs J. 2018;12:180-183. [PMC free article: PMC6128013] [PubMed: 30258507]

- 3.

Holm L, Stucke-Brander T, Wagner S, Sandager P, Schlütter J, Lindahl C, Uldbjerg N. Automated blood pressure self-measurement station compared to office blood pressure measurement for first trimester screening of pre-eclampsia. Health Informatics J. 2019 Dec;25(4):1815-1824. [PubMed: 30253712]

- 4.

Miller MJ, Butler P, Gilchriest J, Taylor A, Lutgendorf MA.

Implementation of a standardized nurse initiated protocol to manage severe hypertension in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 Mar;33(6):1008-1014. [PubMed: 30231657]

Implementation of a standardized nurse initiated protocol to manage severe hypertension in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 Mar;33(6):1008-1014. [PubMed: 30231657]- 5.

Dymara-Konopka W, Laskowska M, Oleszczuk J. Preeclampsia - Current Management and Future Approach. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2018;19(10):786-796. [PubMed: 30255751]

- 6.

Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin Summary, Number 222. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jun;135(6):1492-1495. [PubMed: 32443077]

- 7.

Timpka S, Markovitz A, Schyman T, Mogren I, Fraser A, Franks PW, Rich-Edwards JW. Midlife development of type 2 diabetes and hypertension in women by history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018 Sep 10;17(1):124. [PMC free article: PMC6130069] [PubMed: 30200989]

- 8.

Catov JM, Countouris M, Hauspurg A. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and CVD Prediction: Accounting for Risk Accrual During the Reproductive Years.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 11;72(11):1264-1266. [PubMed: 30190004]

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 11;72(11):1264-1266. [PubMed: 30190004]- 9.

Yang YY, Fang YH, Wang X, Zhang Y, Liu XJ, Yin ZZ. A retrospective cohort study of risk factors and pregnancy outcomes in 14,014 Chinese pregnant women. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Aug;97(33):e11748. [PMC free article: PMC6113036] [PubMed: 30113460]

- 10.

Colussi G, Catena C, Driul L, Pezzutto F, Fagotto V, Darsiè D, Badillo-Pazmay GV, Romano G, Cogo PE, Sechi LA. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is associated with postpartum blood pressure in preeclamptic women and normal pregnancies. J Hypertens. 2021 Mar 01;39(3):563-572. [PubMed: 33031174]

- 11.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203: Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan;133(1):e26-e50. [PubMed: 30575676]

- 12.

Ishikawa T, Obara T, Nishigori H, Miyakoda K, Ishikuro M, Metoki H, Ohkubo T, Sugawara J, Yaegashi N, Akazawa M, Kuriyama S, Mano N.

Antihypertensives prescribed for pregnant women in Japan: Prevalence and timing determined from a database of health insurance claims. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018 Dec;27(12):1325-1334. [PubMed: 30252182]

Antihypertensives prescribed for pregnant women in Japan: Prevalence and timing determined from a database of health insurance claims. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018 Dec;27(12):1325-1334. [PubMed: 30252182]- 13.

Gonzalez Suarez ML, Kattah A, Grande JP, Garovic V. Renal Disorders in Pregnancy: Core Curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019 Jan;73(1):119-130. [PMC free article: PMC6309641] [PubMed: 30122546]

- 14.

Katigbak C, Fontenot HB. A Primer on the New Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of Hypertension. Nurs Womens Health. 2018 Aug;22(4):346-354. [PubMed: 30077241]

- 15.

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Jan;133(1):1. [PubMed: 30575675]

- 16.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 743: Low-Dose Aspirin Use During Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jul;132(1):e44-e52. [PubMed: 29939940]

- 17.

Smith GN, Pudwell J, Saade GR.

Impact of the New American Hypertension Guidelines on the Prevalence of Postpartum Hypertension. Am J Perinatol. 2019 Mar;36(4):440-442. [PubMed: 30170330]

Impact of the New American Hypertension Guidelines on the Prevalence of Postpartum Hypertension. Am J Perinatol. 2019 Mar;36(4):440-442. [PubMed: 30170330]- 18.

Hauspurg A, Sutton EF, Catov JM, Caritis SN. Aspirin Effect on Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Associated With Stage 1 Hypertension in a High-Risk Cohort. Hypertension. 2018 Jul;72(1):202-207. [PMC free article: PMC6002947] [PubMed: 29802215]

- 19.

Hitti J, Sienas L, Walker S, Benedetti TJ, Easterling T. Contribution of hypertension to severe maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;219(4):405.e1-405.e7. [PubMed: 30012335]

- 20.

Du MC, Ouyang YQ, Nie XF, Huang Y, Redding SR. Effects of physical exercise during pregnancy on maternal and infant outcomes in overweight and obese pregnant women: A meta-analysis. Birth. 2019 Jun;46(2):211-221. [PubMed: 30240042]

Anticancer drug treatment for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) that does not respond to first-line treatment or recurs

This review focuses on anticancer drug treatment for women with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN) that does not respond to first-line treatment or recurs. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is the name for a type of cancer that arises from the placental tissue after pregnancy, most commonly in molar pregnancies (chorionadenoma). Chorionadenoma is a benign pathological growth of placental tissue inside the uterus. Most of them can be cured by evacuation (expansion and curettage) of the uterus, however, up to 20% of cases become malignant. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is generally very sensitive to anticancer drugs (chemotherapy), however, these drugs can be toxic, so the goal of treatment is to achieve a cure with the fewest side effects. In order to help physicians choose the most appropriate treatment for women with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, the disease is classified into low or high risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia according to specific risk factors.

Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is the name for a type of cancer that arises from the placental tissue after pregnancy, most commonly in molar pregnancies (chorionadenoma). Chorionadenoma is a benign pathological growth of placental tissue inside the uterus. Most of them can be cured by evacuation (expansion and curettage) of the uterus, however, up to 20% of cases become malignant. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is generally very sensitive to anticancer drugs (chemotherapy), however, these drugs can be toxic, so the goal of treatment is to achieve a cure with the fewest side effects. In order to help physicians choose the most appropriate treatment for women with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, the disease is classified into low or high risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia according to specific risk factors.

Chemotherapy for low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia usually requires only one drug, while high-risk tumors are treated with a combination of drugs. The most commonly used five-drug combination is abbreviated as EMA/CO (etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, vincristine). Doctors assess response to treatment by checking blood levels of the pregnancy hormone (hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin). If chemotherapy does not appear to be working, an alternative (or rescue) treatment should be started. This is necessary in about 25% of cases, and then various combinations of drugs are used.

The most commonly used five-drug combination is abbreviated as EMA/CO (etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, vincristine). Doctors assess response to treatment by checking blood levels of the pregnancy hormone (hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin). If chemotherapy does not appear to be working, an alternative (or rescue) treatment should be started. This is necessary in about 25% of cases, and then various combinations of drugs are used.

We undertook this review because it was not clear which of the various rescue combinations, if any, were the most effective and least toxic. We conducted a literature search through November 2015 to find all relevant studies. Unfortunately, we were unable to find any high-quality studies comparing different salvage treatment options. This is partly because the disease has a high cure rate with multiple combination chemotherapy options, but also because the disease is rare, making it difficult to recruit patients for large trials. Therefore, we were unable to draw conclusions about the possible comparison of these drug combinations in terms of their efficacy and side effects, and we encourage researchers in the field to collaborate to provide this important evidence.

Therefore, we were unable to draw conclusions about the possible comparison of these drug combinations in terms of their efficacy and side effects, and we encourage researchers in the field to collaborate to provide this important evidence.

Translation notes:

Translation: Ziganshina Dina Airatovna. Editing: Ziganshina Lilia Evgenievna. Project coordination for translation into Russian: Cochrane Russia - Cochrane Russia (branch of the Northern Cochrane Center on the basis of Kazan Federal University). For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]

How to optimize the treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease in the era of COVID-19?

Original: American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Author: Antonio Braga et al.

Published: April 28, 2020, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Yana Belysheva, Cancer Prevention Foundation

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the entire global health system has been mobilized to help patients with this disease . This situation has had a significant impact on the management of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTB), both hydatidiform mole (MO) and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). In this article, we review the main changes in the management of GTB using the example of the two largest centers of expertise in the Western Hemisphere, where COVID-19 is prevalent.(USA and Brazil).

This situation has had a significant impact on the management of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTB), both hydatidiform mole (MO) and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). In this article, we review the main changes in the management of GTB using the example of the two largest centers of expertise in the Western Hemisphere, where COVID-19 is prevalent.(USA and Brazil).

The biggest impact of COVID-19 is the imposition of lockdowns with only essential health services fully operational. Given the limited use of diagnostic imaging techniques, a delayed diagnosis of PT is expected, leading to medical complications historically observed at 12 weeks of gestation and beyond [1]. Even asymptomatic PZ should be regarded as an emergency. Once the diagnosis is made, the PZ should be evacuated as soon as possible to avoid complications.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, follow-up after the FH evacuation consisted of weekly monitoring of serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels and periodic physical examinations. During a pandemic, we consider it appropriate to use telemedicine to monitor uncomplicated cases. To minimize the risk of viral exposure during hCG blood draws, we suggest biweekly monitoring if hCG levels are gradually declining. In cases where the hCG level lingers on a plateau or rises again, weekly hormonal testing should be resumed. In addition, we suggest early discontinuation of hCG monitoring in patients with PZ: in case of incomplete PZ, monitoring is stopped with a single reception of a normal hCG level one month after achieving remission (remission = 3 previous weekly measurements of hCG <5 IU / L), and with complete PZ - when receiving 3 normal monthly hCG values after achieving remission, in contrast to the current monitoring standard of 6 months [2].

During a pandemic, we consider it appropriate to use telemedicine to monitor uncomplicated cases. To minimize the risk of viral exposure during hCG blood draws, we suggest biweekly monitoring if hCG levels are gradually declining. In cases where the hCG level lingers on a plateau or rises again, weekly hormonal testing should be resumed. In addition, we suggest early discontinuation of hCG monitoring in patients with PZ: in case of incomplete PZ, monitoring is stopped with a single reception of a normal hCG level one month after achieving remission (remission = 3 previous weekly measurements of hCG <5 IU / L), and with complete PZ - when receiving 3 normal monthly hCG values after achieving remission, in contrast to the current monitoring standard of 6 months [2].

Patients with asymptomatic GTN should not delay starting chemotherapy because of the theoretical risk of infection; but if they are COVID-19 positive and have symptoms during treatment, then chemotherapy should be delayed until at least the resolution of respiratory symptoms [3,4].

During a pandemic, we recommend starting treatment with a bolus of actinomycin-D (Act-D) 1.25 mg/m2 twice weekly for patients with low-risk GTN. This regimen requires fewer doctor visits, may result in a higher response rate, and a shorter time to remission compared to methotrexate (MTX) [4].

Multi-agent chemotherapy (usually includes etoposide, MTX, Act-D, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine) is used as the primary treatment for high-risk GTN. In patients receiving a multi-agent regimen, neutropenia and immunosuppression should be carefully monitored and treated, as cancer patients are more susceptible to COVID-19 and are at higher risk of severe disease, admission to the intensive care unit, and death [5]. In order to avoid immunosuppression in the treatment of multi-agent chemotherapy, we recommend the routine use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [3].

During chemotherapy, and especially in the first 14 days after it, pneumonia can be the most severe manifestation of COVID-19 infection. In general, we do not recommend chemotherapy during treatment for COVID-19, with the possible exception of patients with significant lung metastases, whose treatment may improve respiratory function.

In general, we do not recommend chemotherapy during treatment for COVID-19, with the possible exception of patients with significant lung metastases, whose treatment may improve respiratory function.

While there are significant challenges in managing HDB patients during a pandemic, the proposed recommendations aim to maximize the quality of care provided to these patients.

Ref:

1. Sun SY, Melamed A, Goldstein DP, et al. Changing presentation of complete hydatidiform mole at the New England Trophoblastic Disease Center over the past three decades: does early alter diagnosis risk for gestational trophoblastic neoplasia? Gynecol Oncol 138:46–9, 2015

2. Horowitz NS, Berkowitz RS, Elias KM. Considering Changes in the Recommended Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Monitoring After Molar Evacuation. Obstet Gynecol 135:9–11, 2020

3. American Society of Clinical Oncology. COVID-19 Patient Care Information. 2020 April 23. Available in: https://www.asco.org/asco-coronavirus-information/care-individuals109 cancer-during-covid-19 Accessed in April 28, 2020

4.