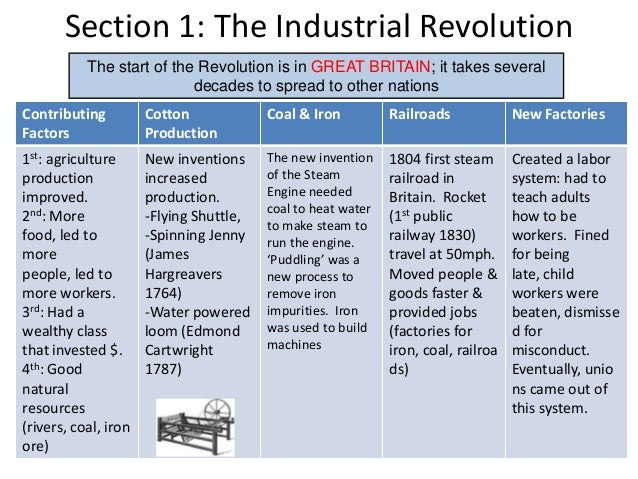

How was child labor stopped in the industrial revolution

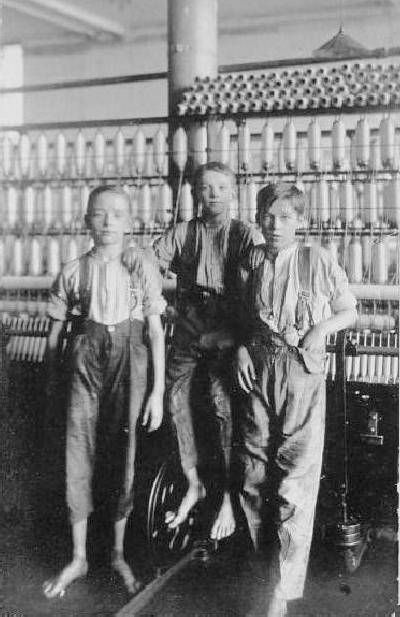

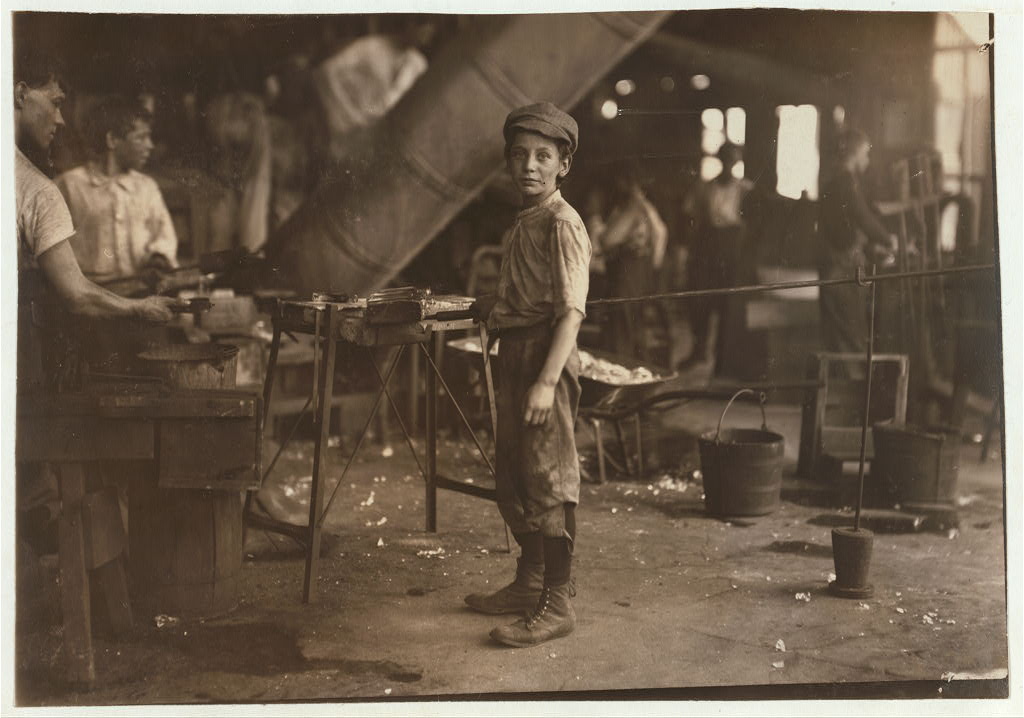

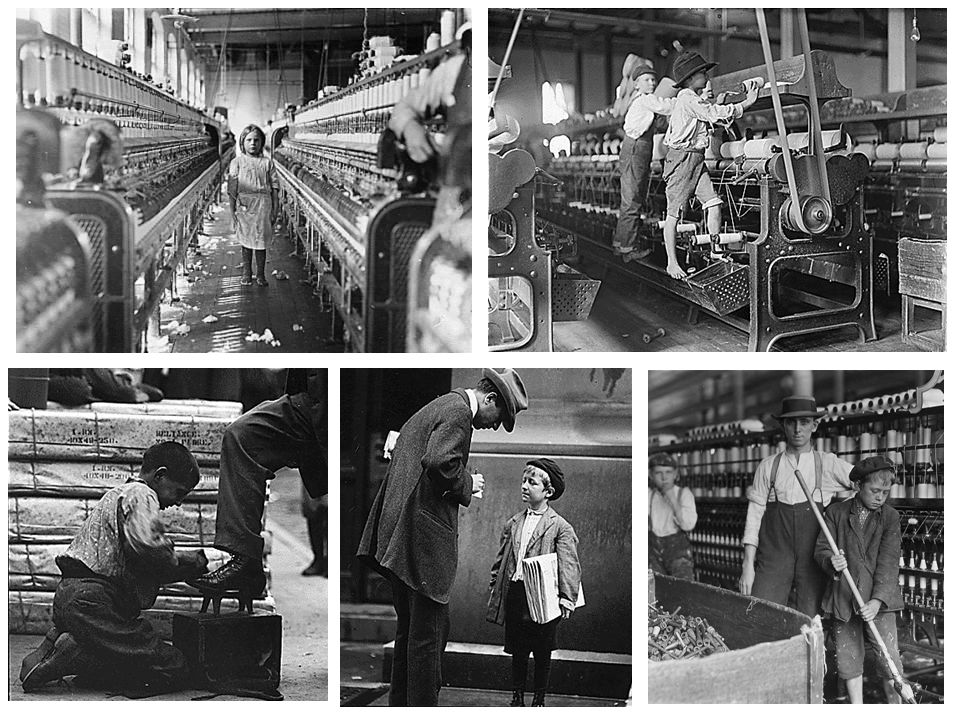

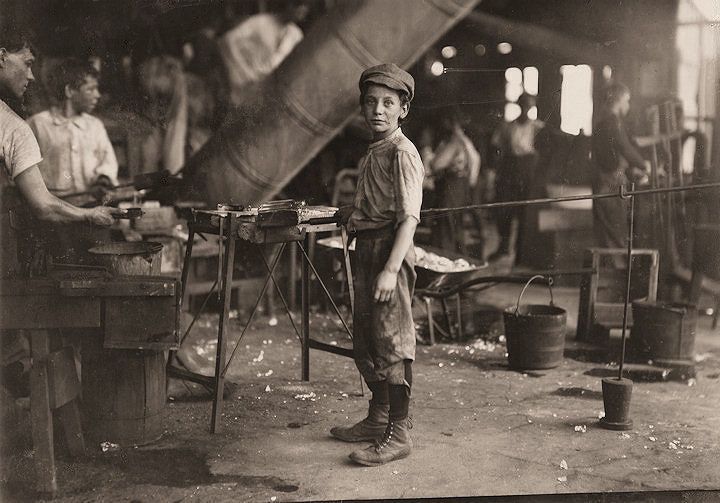

Child Labor in U.S. History

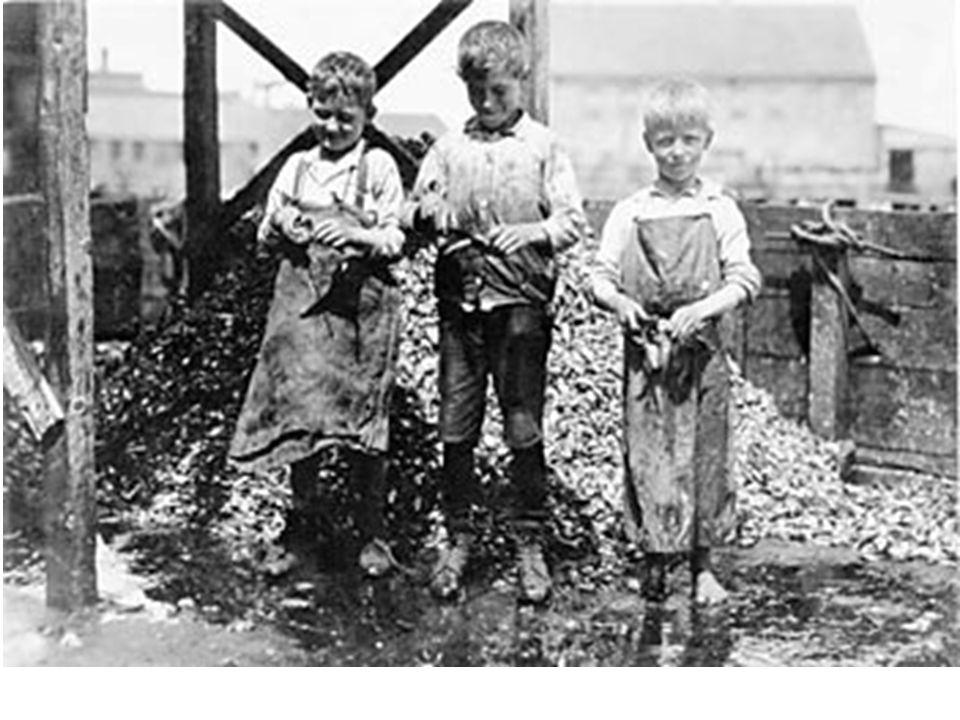

Breaker Boys

Hughestown Borough Pa. Coal Co.

Pittston, Pa.

Photo: Lewis Hine

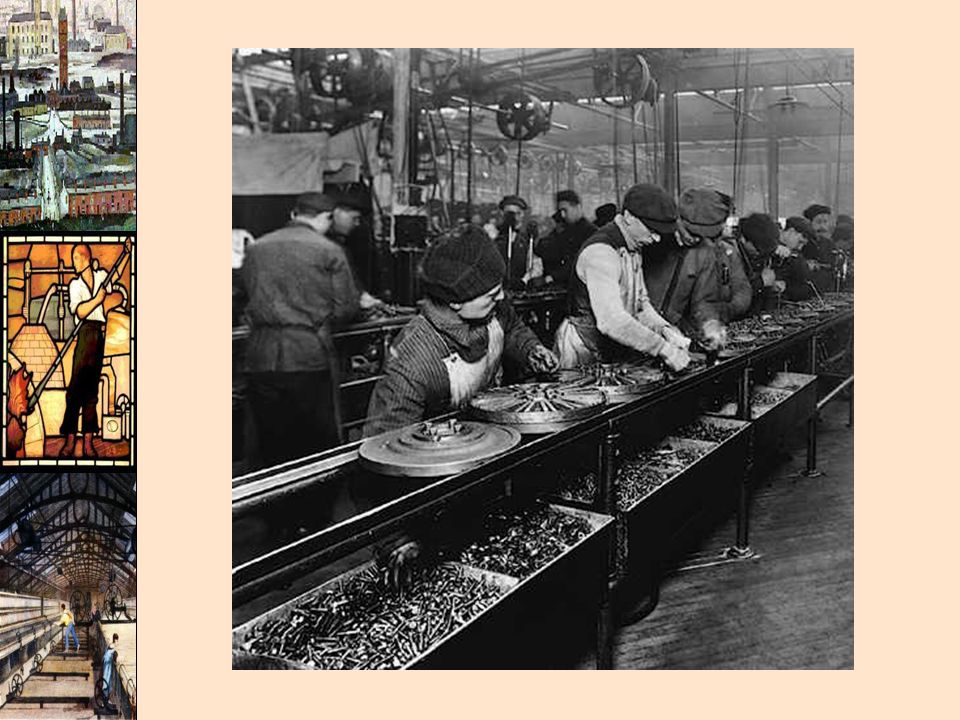

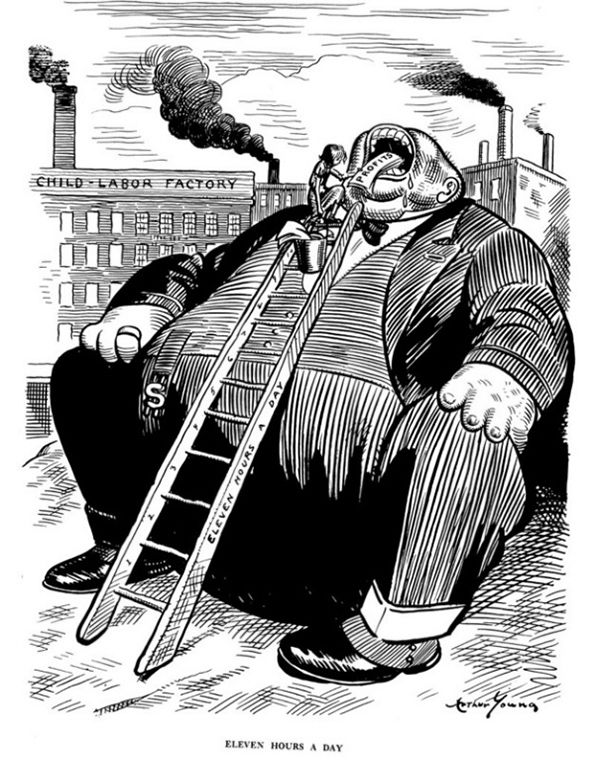

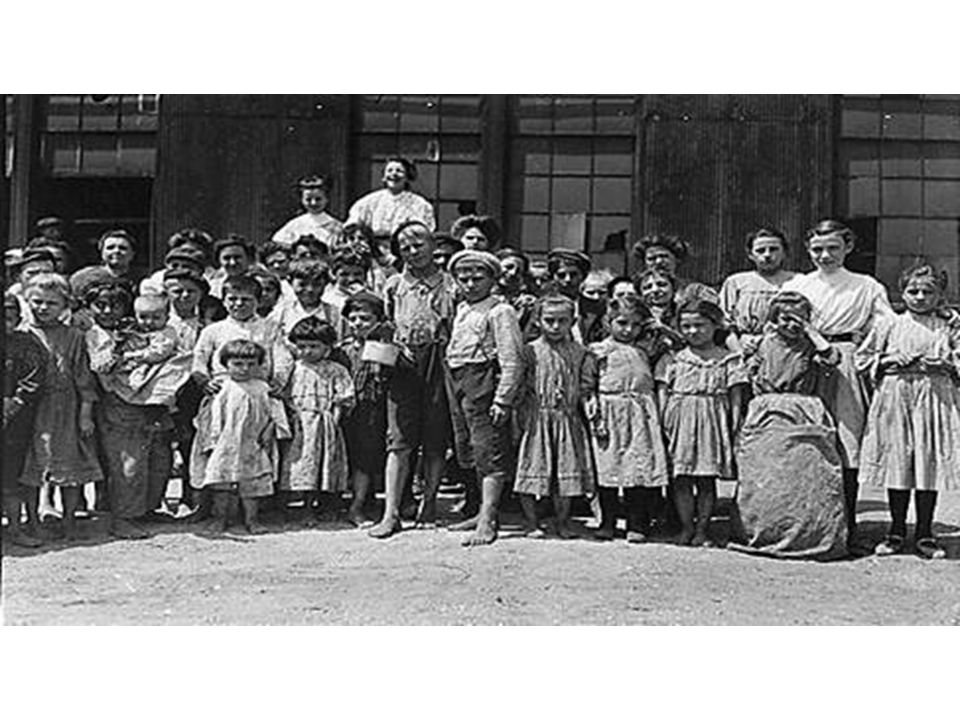

Forms of child labor, including indentured servitude and child slavery, have existed throughout American history. As industrialization moved workers from farms and home workshops into urban areas and factory work, children were often preferred, because factory owners viewed them as more manageable, cheaper, and less likely to strike. Growing opposition to child labor in the North caused many factories to move to the South. By 1900, states varied considerably in whether they had child labor standards and in their content and degree of enforcement. By then, American children worked in large numbers in mines, glass factories, textiles, agriculture, canneries, home industries, and as newsboys, messengers, bootblacks, and peddlers.

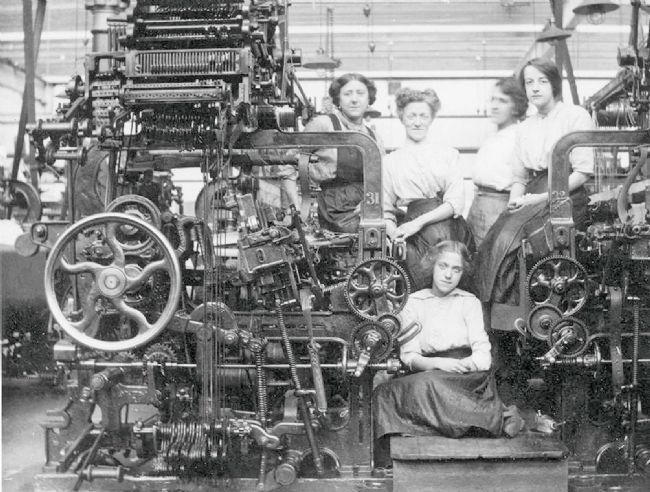

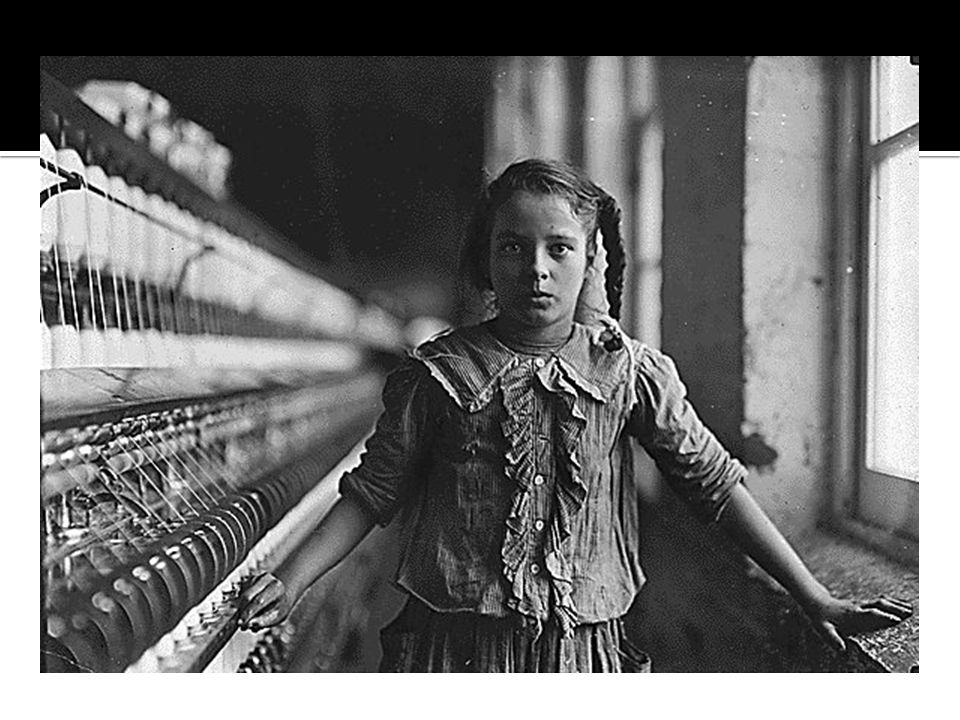

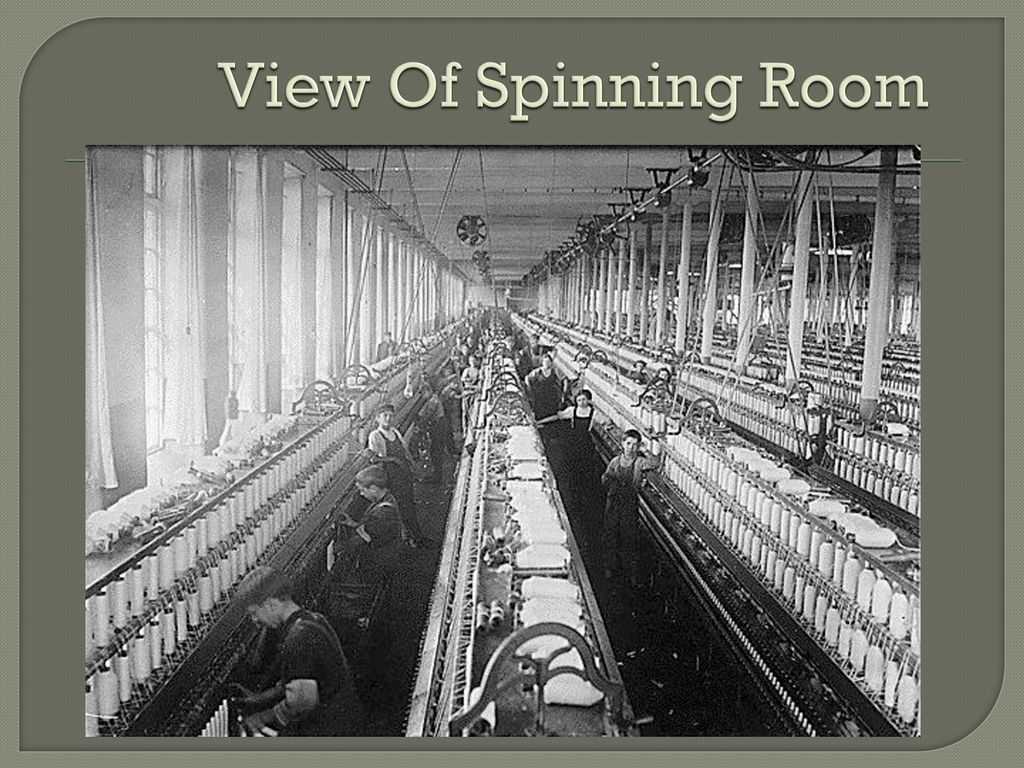

Spinning Room

Cornell Mill

Fall River, Mass.

Photo: Lewis Hine

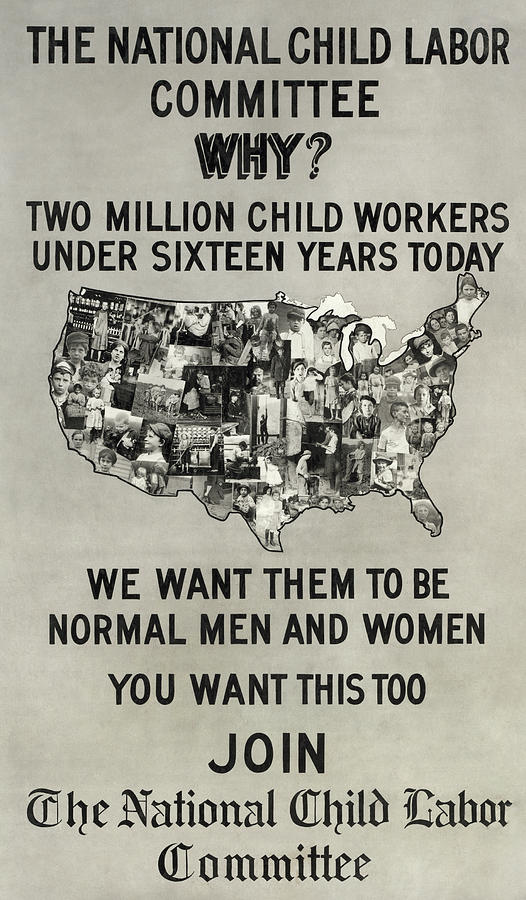

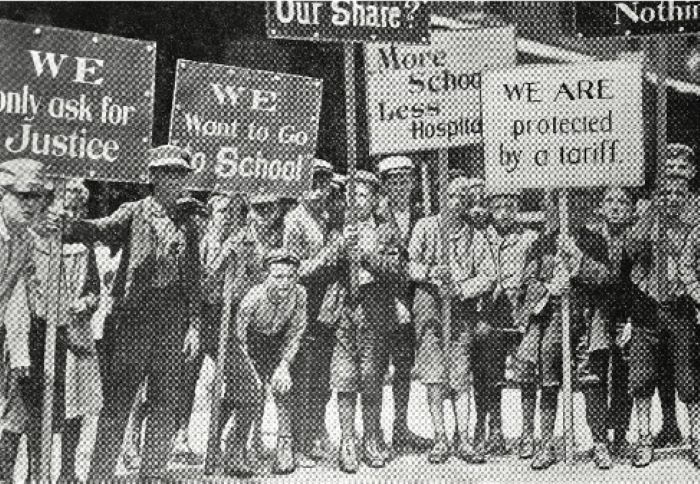

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the numbers of child laborers in the U. S. peaked. Child labor began to decline as the labor and reform movements grew and labor standards in general began improving, increasing the political power of working people and other social reformers to demand legislation regulating child labor. Union organizing and child labor reform were often intertwined, and common initiatives were conducted by organizations led by working women and middle class consumers, such as state Consumers’ Leagues and Working Women’s Societies. These organizations generated the National Consumers’ League in 1899 and the National Child Labor Committee in 1904, which shared goals of challenging child labor, including through anti-sweatshop campaigns and labeling programs. The National Child Labor Committee’s work to end child labor was combined with efforts to provide free, compulsory education for all children, and culminated in the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, which set federal standards for child labor.

1832 New England unions condemn child labor

The New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workingmen resolve that “Children should not be allowed to labor in the factories from morning till night, without any time for healthy recreation and mental culture,” for it “endangers their . . . well-being and health”

. . well-being and health”

Women's Trade Union League of New York

1836 Early trade unions propose state minimum age laws

Union members at the National Trades’ Union Convention make the first formal, public proposal recommending that states establish minimum ages for factory work

1836 First state child labor law

Massachusetts requires children under 15 working in factories to attend school at least 3 months/year

1842 States begin limiting children’s work days

Massachusetts limits children’s work days to 10 hours; other states soon pass similar laws—but most of these laws are not consistently enforced

1876 Labor movement urges minimum age law

Working Men’s Party proposes banning the employment of children under the age of 14

1881 Newly formed AFL supports state minimum age laws

The first national convention of the American Federation of Labor passes a resolution calling on states to ban children under 14 from all gainful employment

1883 New York unions win state reform

Led by Samuel Gompers, the New York labor movement successfully sponsors legislation prohibiting cigar making in tenements, where thousands of young children work in the trade

1892 Democrats adopt union recommendations

Democratic Party adopts platform plank based on union recommendations to ban factory employment for children under 15

National Child Labor Committee

1904 National Child Labor Committee forms

Aggressive national campaign for federal child labor law reform begins

1916 New federal law sanctions state violators

First federal child labor law prohibits movement of goods across state lines if minimum age laws are violated (law in effect only until 1918, when it’s declared unconstitutional, then revised, passed, and declared unconstitutional again)

1924 First attempt to gain federal regulation fails

Congress passes a constitutional amendment giving the federal government authority to regulate child labor, but too few states ratify it and it never takes effect

1936 Federal purchasing law passes

Walsh-Healey Act states U. S. government will not purchase goods made by underage children

S. government will not purchase goods made by underage children

1937 Second attempt to gain federal regulation fails

Second attempt to ratify constitutional amendment giving federal government authority to regulate child labor falls just short of getting necessary votes

1937 New federal law sanctions growers

Sugar Act makes sugar beet growers ineligible for benefit payments if they violate state minimum age and hours of work standards

1938 Federal regulation of child labor achieved in Fair Labor Standards Act

For the first time, minimum ages of employment and hours of work for children are regulated by federal law

Educational materials containing more information on Child Labor in U.S. History and Causes of Child Labor, including Workshop Materials—Core Workshop on Child Labor and K-12 Teachers’ Materials, are available through this web site. These materials include Power Point presentations, instructors’ manuals, activities, and handouts. You may adapt these materials to your group’s needs.

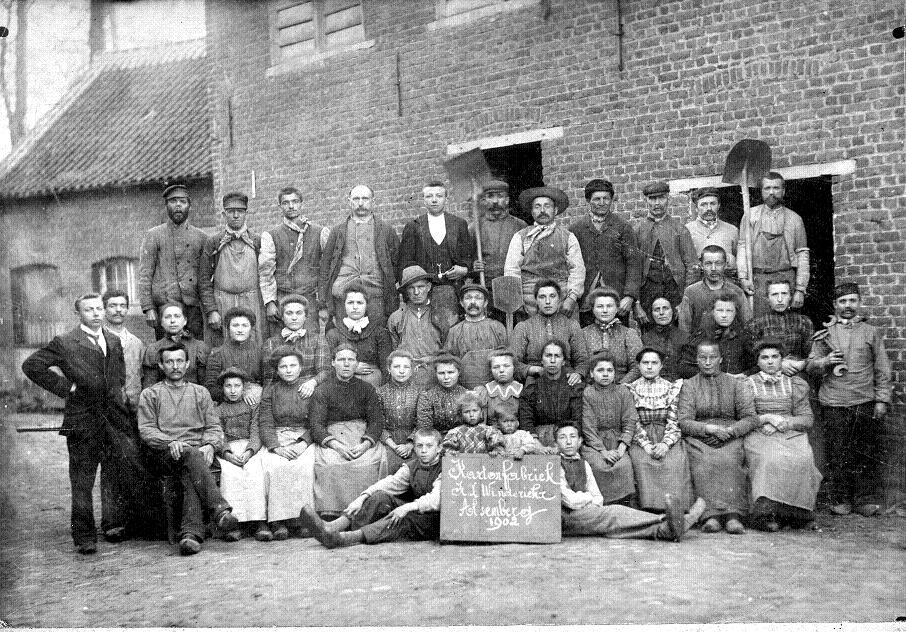

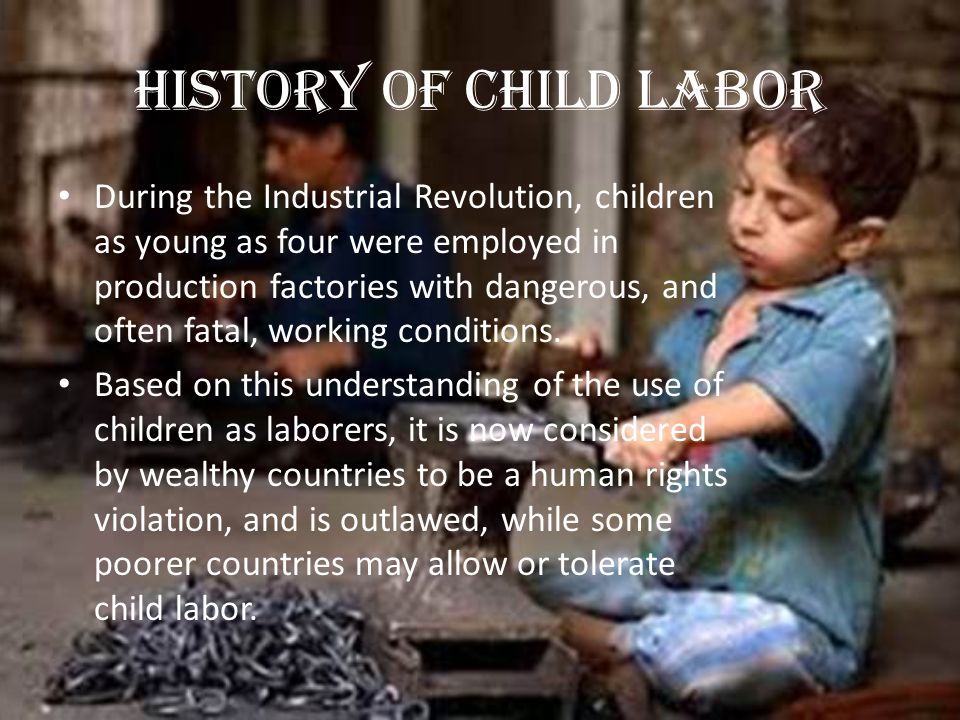

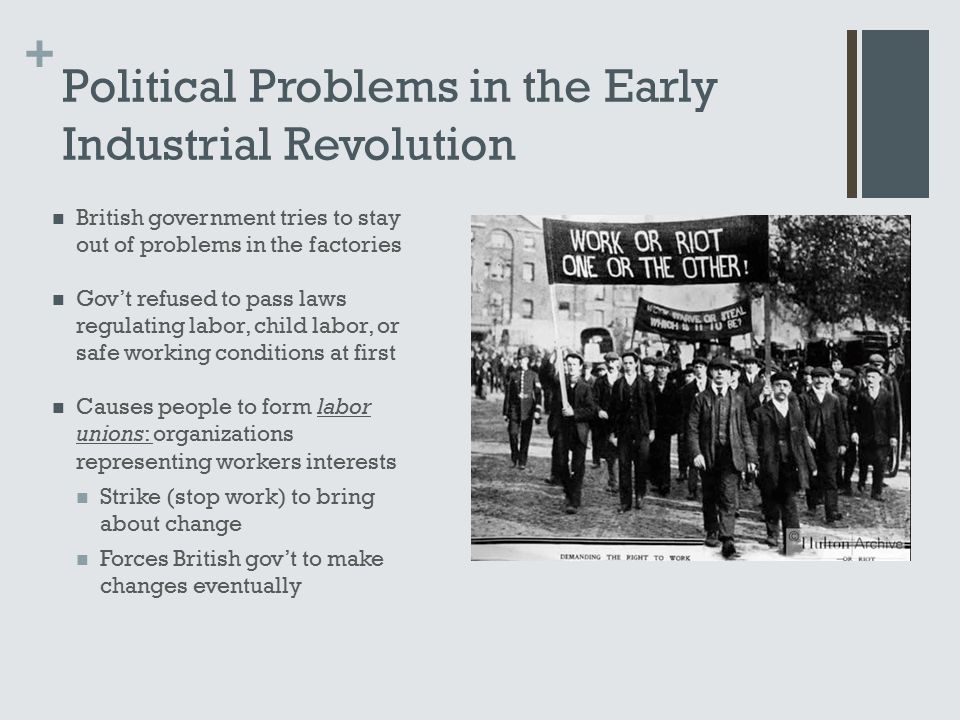

Child Labor during the British Industrial Revolution

Carolyn Tuttle, Lake Forest College

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Great Britain became the first country to industrialize. Because of this, it was also the first country where the nature of children’s work changed so dramatically that child labor became seen as a social problem and a political issue.

This article examines the historical debate about child labor in Britain, Britain’s political response to problems with child labor, quantitative evidence about child labor during the 1800s, and economic explanations of the practice of child labor.

The Historical Debate about Child Labor in Britain

Child Labor before Industrialization

Children of poor and working-class families had worked for centuries before industrialization – helping around the house or assisting in the family’s enterprise when they were able. The practice of putting children to work was first documented in the Medieval era when fathers had their children spin thread for them to weave on the loom. Children performed a variety of tasks that were auxiliary to their parents but critical to the family economy. The family’s household needs determined the family’s supply of labor and “the interdependence of work and residence, of household labor needs, subsidence requirements, and family relationships constituted the ‘family economy'” [Tilly and Scott (1978, 12)].

Children performed a variety of tasks that were auxiliary to their parents but critical to the family economy. The family’s household needs determined the family’s supply of labor and “the interdependence of work and residence, of household labor needs, subsidence requirements, and family relationships constituted the ‘family economy'” [Tilly and Scott (1978, 12)].

Definitions of Child Labor

The term “child labor” generally refers to children who work to produce a good or a service which can be sold for money in the marketplace regardless of whether or not they are paid for their work. A “child” is usually defined as a person who is dependent upon other individuals (parents, relatives, or government officials) for his or her livelihood. The exact ages of “childhood” differ by country and time period.

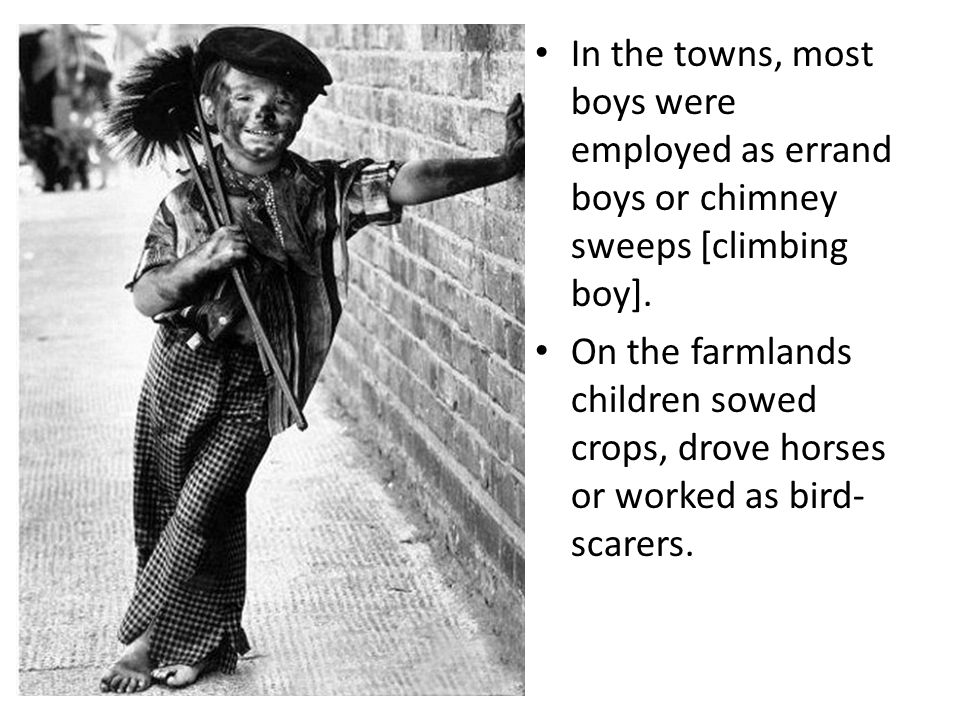

Preindustrial Jobs

Children who lived on farms worked with the animals or in the fields planting seeds, pulling weeds and picking the ripe crop. Ann Kussmaul’s (1981) research uncovered a high percentage of youths working as servants in husbandry in the sixteenth century. Boys looked after the draught animals, cattle and sheep while girls milked the cows and cared for the chickens. Children who worked in homes were either apprentices, chimney sweeps, domestic servants, or assistants in the family business. As apprentices, children lived and worked with their master who established a workshop in his home or attached to the back of his cottage. The children received training in the trade instead of wages. Once they became fairly skilled in the trade they became journeymen. By the time they reached the age of twenty-one, most could start their own business because they had become highly skilled masters. Both parents and children considered this a fair arrangement unless the master was abusive. The infamous chimney sweeps, however, had apprenticeships considered especially harmful and exploitative. Boys as young as four would work for a master sweep who would send them up the narrow chimneys of British homes to scrape the soot off the sides. The first labor law passed in Britain to protect children from poor working conditions, the Act of 1788, attempted to improve the plight of these “climbing boys.

Boys looked after the draught animals, cattle and sheep while girls milked the cows and cared for the chickens. Children who worked in homes were either apprentices, chimney sweeps, domestic servants, or assistants in the family business. As apprentices, children lived and worked with their master who established a workshop in his home or attached to the back of his cottage. The children received training in the trade instead of wages. Once they became fairly skilled in the trade they became journeymen. By the time they reached the age of twenty-one, most could start their own business because they had become highly skilled masters. Both parents and children considered this a fair arrangement unless the master was abusive. The infamous chimney sweeps, however, had apprenticeships considered especially harmful and exploitative. Boys as young as four would work for a master sweep who would send them up the narrow chimneys of British homes to scrape the soot off the sides. The first labor law passed in Britain to protect children from poor working conditions, the Act of 1788, attempted to improve the plight of these “climbing boys. ” Around age twelve many girls left home to become domestic servants in the homes of artisans, traders, shopkeepers and manufacturers. They received a low wage, and room and board in exchange for doing household chores (cleaning, cooking, caring for children and shopping).

” Around age twelve many girls left home to become domestic servants in the homes of artisans, traders, shopkeepers and manufacturers. They received a low wage, and room and board in exchange for doing household chores (cleaning, cooking, caring for children and shopping).

Children who were employed as assistants in domestic production (or what is also called the cottage industry) were in the best situation because they worked at home for their parents. Children who were helpers in the family business received training in a trade and their work directly increased the productivity of the family and hence the family’s income. Girls helped with dressmaking, hat making and button making while boys assisted with shoemaking, pottery making and horse shoeing. Although hours varied from trade to trade and family to family, children usually worked twelve hours per day with time out for meals and tea. These hours, moreover, were not regular over the year or consistent from day-to-day. The weather and family events affected the number of hours in a month children worked. This form of child labor was not viewed by society as cruel or abusive but was accepted as necessary for the survival of the family and development of the child.

This form of child labor was not viewed by society as cruel or abusive but was accepted as necessary for the survival of the family and development of the child.

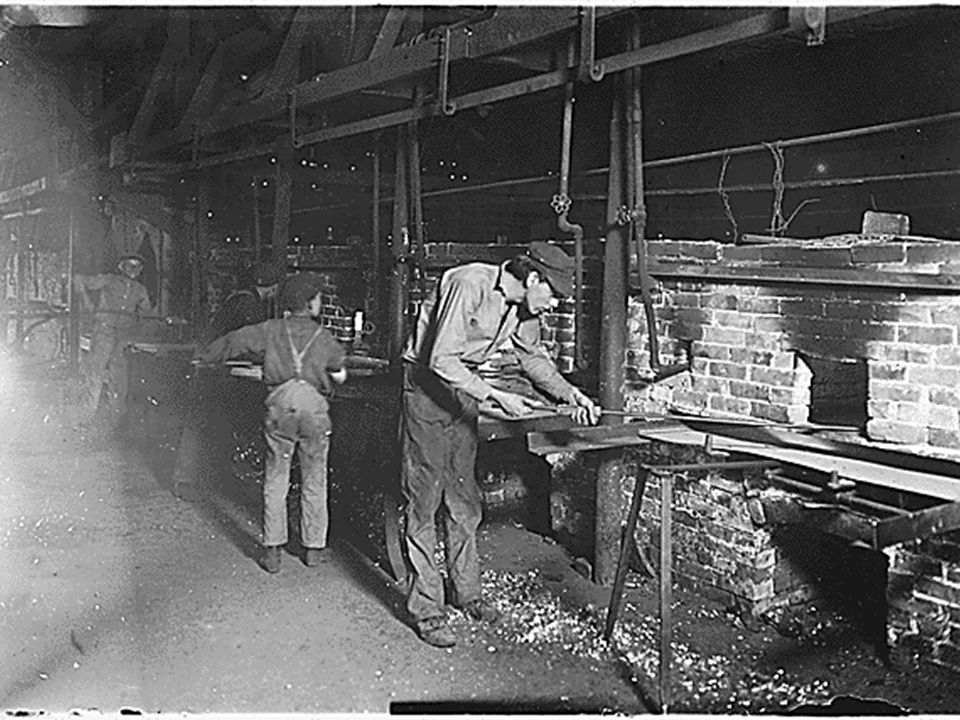

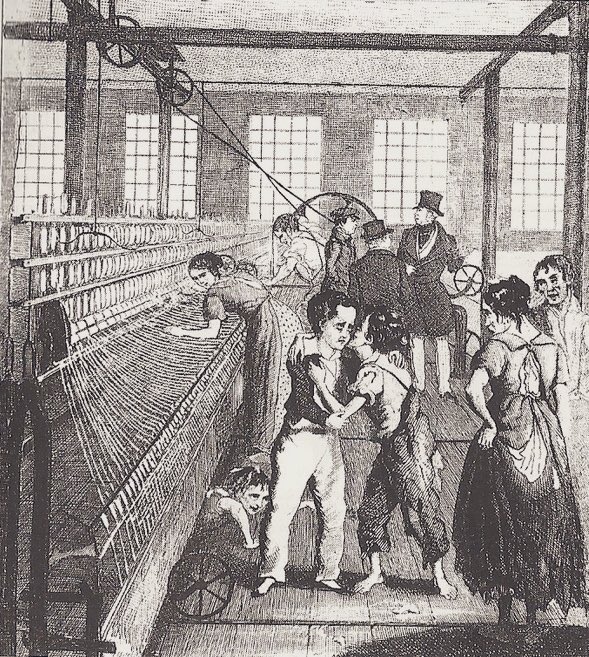

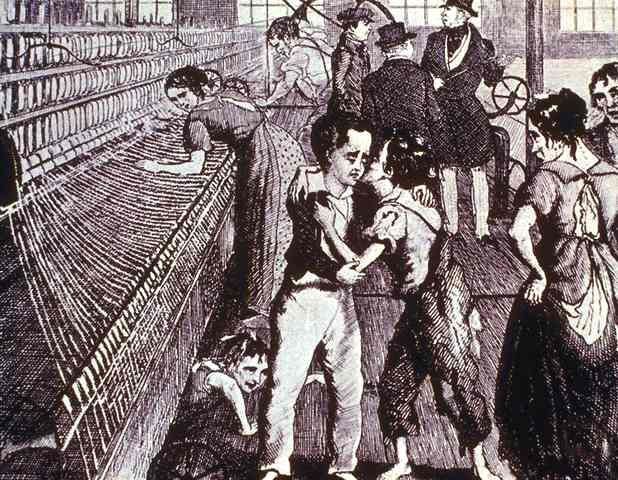

Early Industrial Work

Once the first rural textile mills were built (1769) and child apprentices were hired as primary workers, the connotation of “child labor” began to change. Charles Dickens called these places of work the “dark satanic mills” and E. P. Thompson described them as “places of sexual license, foul language, cruelty, violent accidents, and alien manners” (1966, 307). Although long hours had been the custom for agricultural and domestic workers for generations, the factory system was criticized for strict discipline, harsh punishment, unhealthy working conditions, low wages, and inflexible work hours. The factory depersonalized the employer-employee relationship and was attacked for stripping the worker’s freedom, dignity and creativity. These child apprentices were paupers taken from orphanages and workhouses and were housed, clothed and fed but received no wages for their long day of work in the mill. A conservative estimate is that around 1784 one-third of the total workers in country mills were apprentices and that their numbers reached 80 to 90% in some individual mills (Collier, 1964). Despite the First Factory Act of 1802 (which attempted to improve the conditions of parish apprentices), several mill owners were in the same situation as Sir Robert Peel and Samuel Greg who solved their labor shortage by employing parish apprentices.

A conservative estimate is that around 1784 one-third of the total workers in country mills were apprentices and that their numbers reached 80 to 90% in some individual mills (Collier, 1964). Despite the First Factory Act of 1802 (which attempted to improve the conditions of parish apprentices), several mill owners were in the same situation as Sir Robert Peel and Samuel Greg who solved their labor shortage by employing parish apprentices.

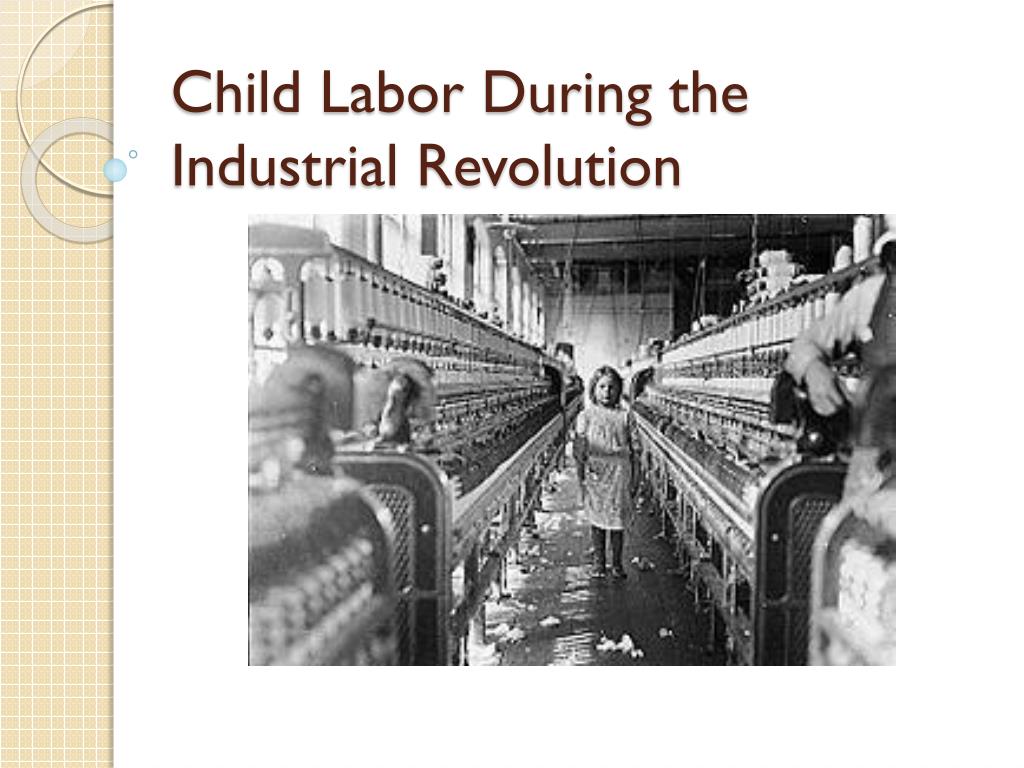

After the invention and adoption of Watt’s steam engine, mills no longer had to locate near water and rely on apprenticed orphans – hundreds of factory towns and villages developed in Lancashire, Manchester, Yorkshire and Cheshire. The factory owners began to hire children from poor and working-class families to work in these factories preparing and spinning cotton, flax, wool and silk.

The Child Labor Debate

What happened to children within these factory walls became a matter of intense social and political debate that continues today. Pessimists such as Alfred (1857), Engels (1926), Marx (1909), and Webb and Webb (1898) argued that children worked under deplorable conditions and were being exploited by the industrialists. A picture was painted of the “dark satanic mill” where children as young as five and six years old worked for twelve to sixteen hours a day, six days a week without recess for meals in hot, stuffy, poorly lit, overcrowded factories to earn as little as four shillings per week. Reformers called for child labor laws and after considerable debate, Parliament took action and set up a Royal Commission of Inquiry into children’s employment. Optimists, on the other hand, argued that the employment of children in these factories was beneficial to the child, family and country and that the conditions were no worse than they had been on farms, in cottages or up chimneys. Ure (1835) and Clapham (1926) argued that the work was easy for children and helped them make a necessary contribution to their family’s income.

Pessimists such as Alfred (1857), Engels (1926), Marx (1909), and Webb and Webb (1898) argued that children worked under deplorable conditions and were being exploited by the industrialists. A picture was painted of the “dark satanic mill” where children as young as five and six years old worked for twelve to sixteen hours a day, six days a week without recess for meals in hot, stuffy, poorly lit, overcrowded factories to earn as little as four shillings per week. Reformers called for child labor laws and after considerable debate, Parliament took action and set up a Royal Commission of Inquiry into children’s employment. Optimists, on the other hand, argued that the employment of children in these factories was beneficial to the child, family and country and that the conditions were no worse than they had been on farms, in cottages or up chimneys. Ure (1835) and Clapham (1926) argued that the work was easy for children and helped them make a necessary contribution to their family’s income. Many factory owners claimed that employing children was necessary for production to run smoothly and for their products to remain competitive. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, recommended child labor as a means of preventing youthful idleness and vice. Ivy Pinchbeck (1930) pointed out, moreover, that working hours and conditions had been as bad in the older domestic industries as they were in the industrial factories.

Many factory owners claimed that employing children was necessary for production to run smoothly and for their products to remain competitive. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, recommended child labor as a means of preventing youthful idleness and vice. Ivy Pinchbeck (1930) pointed out, moreover, that working hours and conditions had been as bad in the older domestic industries as they were in the industrial factories.

Factory Acts

Although the debate over whether children were exploited during the British Industrial Revolution continues today [see Nardinelli (1988) and Tuttle (1998)], Parliament passed several child labor laws after hearing the evidence collected. The three laws which most impacted the employment of children in the textile industry were the Cotton Factories Regulation Act of 1819 (which set the minimum working age at 9 and maximum working hours at 12), the Regulation of Child Labor Law of 1833 (which established paid inspectors to enforce the laws) and the Ten Hours Bill of 1847 (which limited working hours to 10 for children and women).

The Extent of Child Labor

The significance of child labor during the Industrial Revolution was attached to both the changes in the nature of child labor and the extent to which children were employed in the factories. Cunningham (1990) argues that the idleness of children was more a problem during the Industrial Revolution than the exploitation resulting from employment. He examines the Report on the Poor Laws in 1834 and finds that in parish after parish there was very little employment for children. In contrast, Cruickshank (1981), Hammond and Hammond (1937), Nardinelli (1990), Redford (1926), Rule (1981), and Tuttle (1999) claim that a large number of children were employed in the textile factories. These two seemingly contradictory claims can be reconciled because the labor market for child labor was not a national market. Instead, child labor was a regional phenomenon where a high incidence of child labor existed in the manufacturing districts while a low incidence of children were employed in rural and farming districts.

Since the first reliable British Census that inquired about children’s work was in 1841, it is impossible to compare the number of children employed on the farms and in cottage industry with the number of children employed in the factories during the heart of the British industrial revolution. It is possible, however, to get a sense of how many children were employed by the industries considered the “leaders” of the Industrial Revolution – textiles and coal mining. Although there is still not a consensus on the degree to which industrial manufacturers depended on child labor, research by several economic historians have uncovered several facts.

Estimates of Child Labor in Textiles

Using data from an early British Parliamentary Report (1819[HL.24]CX), Freuenberger, Mather and Nardinelli concluded that “children formed a substantial part of the labor force” in the textile mills (1984, 1087). They calculated that while only 4.5% of the cotton workers were under 10, 54. 5% were under the age of 19 – confirmation that the employment of children and youths was pervasive in cotton textile factories (1984, 1087). Tuttle’s research using a later British Parliamentary Report (1834(167)XIX) shows this trend continued. She calculated that children under 13 comprised roughly 10 to 20 % of the work forces in the cotton, wool, flax, and silk mills in 1833. The employment of youths between the age of 13 and 18 was higher than for younger children, comprising roughly 23 to 57% of the work forces in cotton, wool, flax, and silk mills. Cruickshank also confirms that the contribution of children to textile work forces was significant. She showed that the growth of the factory system meant that from one-sixth to one-fifth of the total work force in the textile towns in 1833 were children under 14. There were 4,000 children in the mills of Manchester; 1,600 in Stockport; 1,500 in Bolton and 1,300 in Hyde (1981, 51).

5% were under the age of 19 – confirmation that the employment of children and youths was pervasive in cotton textile factories (1984, 1087). Tuttle’s research using a later British Parliamentary Report (1834(167)XIX) shows this trend continued. She calculated that children under 13 comprised roughly 10 to 20 % of the work forces in the cotton, wool, flax, and silk mills in 1833. The employment of youths between the age of 13 and 18 was higher than for younger children, comprising roughly 23 to 57% of the work forces in cotton, wool, flax, and silk mills. Cruickshank also confirms that the contribution of children to textile work forces was significant. She showed that the growth of the factory system meant that from one-sixth to one-fifth of the total work force in the textile towns in 1833 were children under 14. There were 4,000 children in the mills of Manchester; 1,600 in Stockport; 1,500 in Bolton and 1,300 in Hyde (1981, 51).

The employment of children in textile factories continued to be high until mid-nineteenth century. According to the British Census, in 1841 the three most common occupations of boys were Agricultural Labourer, Domestic Servant and Cotton Manufacture with 196,640; 90,464 and 44,833 boys under 20 employed, respectively. Similarly for girls the three most common occupations include Cotton Manufacture. In 1841, 346,079 girls were Domestic Servants; 62,131 were employed in Cotton Manufacture and 22,174 were Dress-makers. By 1851 the three most common occupations for boys under 15 were Agricultural Labourer (82,259), Messenger (43,922) and Cotton Manufacture (33,228) and for girls it was Domestic Servant (58,933), Cotton Manufacture (37,058) and Indoor Farm Servant (12,809) (1852-53[1691-I]LXXXVIII, pt.1). It is clear from these findings that children made up a large portion of the work force in textile mills during the nineteenth century. Using returns from the Factory Inspectors, S. J. Chapman’s (1904) calculations reveal that the percentage of child operatives under 13 had a downward trend for the first half of the century from 13.

According to the British Census, in 1841 the three most common occupations of boys were Agricultural Labourer, Domestic Servant and Cotton Manufacture with 196,640; 90,464 and 44,833 boys under 20 employed, respectively. Similarly for girls the three most common occupations include Cotton Manufacture. In 1841, 346,079 girls were Domestic Servants; 62,131 were employed in Cotton Manufacture and 22,174 were Dress-makers. By 1851 the three most common occupations for boys under 15 were Agricultural Labourer (82,259), Messenger (43,922) and Cotton Manufacture (33,228) and for girls it was Domestic Servant (58,933), Cotton Manufacture (37,058) and Indoor Farm Servant (12,809) (1852-53[1691-I]LXXXVIII, pt.1). It is clear from these findings that children made up a large portion of the work force in textile mills during the nineteenth century. Using returns from the Factory Inspectors, S. J. Chapman’s (1904) calculations reveal that the percentage of child operatives under 13 had a downward trend for the first half of the century from 13. 4% in 1835 to 4.7% in 1838 to 5.8% in 1847 and 4.6% by 1850 and then rose again to 6.5% in 1856, 8.8% in 1867, 10.4% in 1869 and 9.6% in 1870 (1904, 112).

4% in 1835 to 4.7% in 1838 to 5.8% in 1847 and 4.6% by 1850 and then rose again to 6.5% in 1856, 8.8% in 1867, 10.4% in 1869 and 9.6% in 1870 (1904, 112).

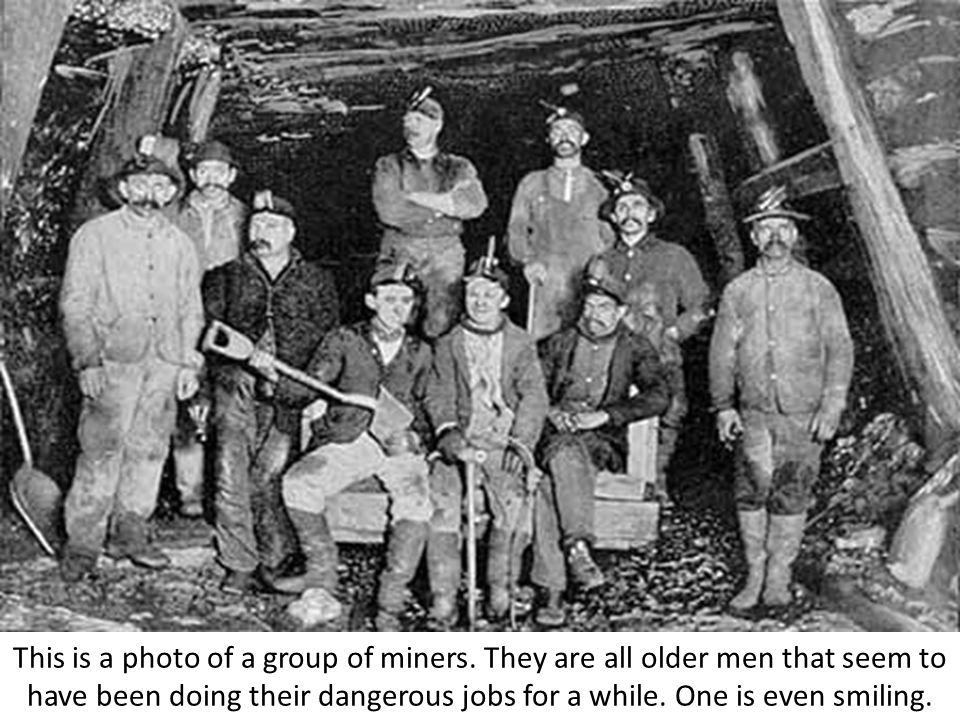

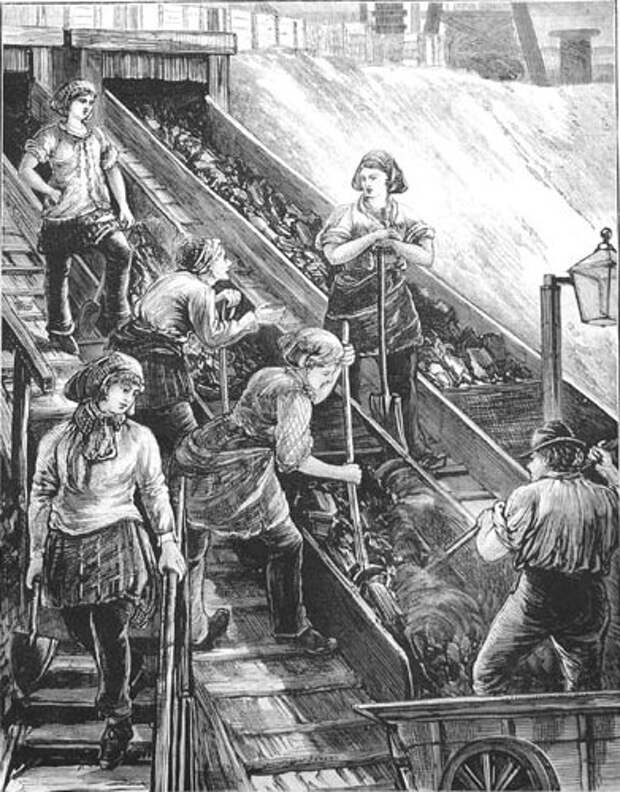

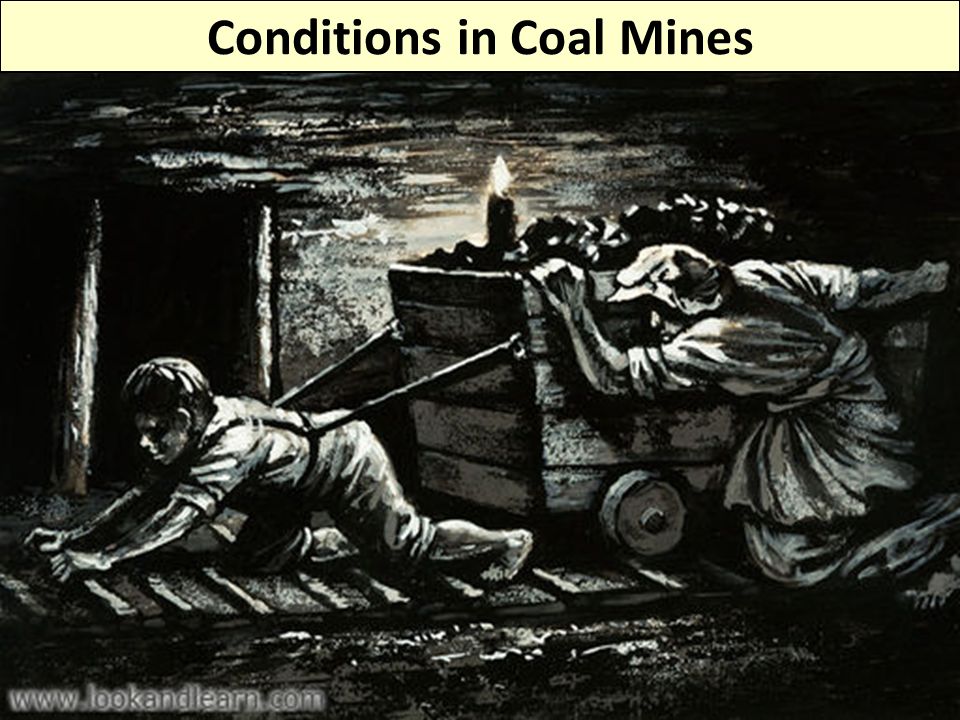

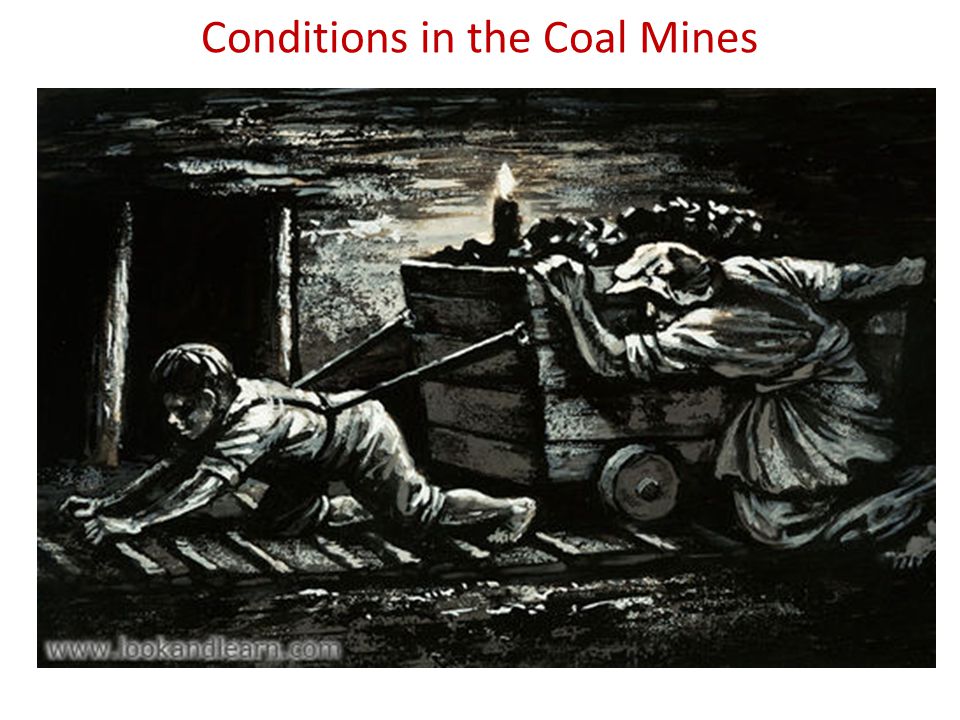

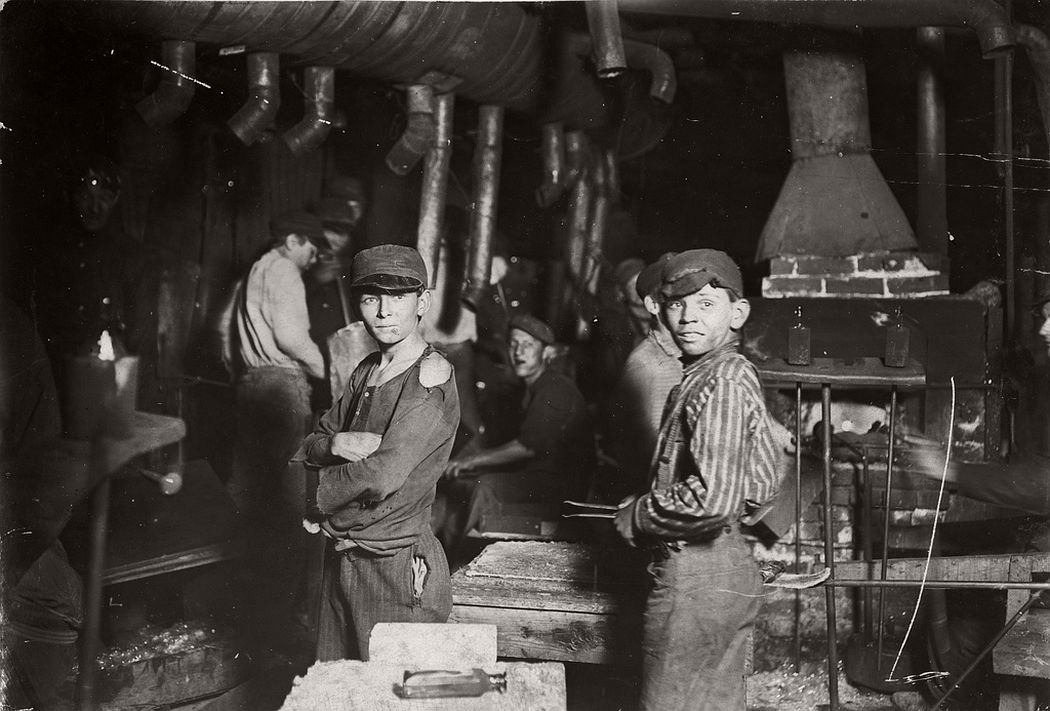

Estimates of Child Labor in Mining

Children and youth also comprised a relatively large proportion of the work forces in coal and metal mines in Britain. In 1842, the proportion of the work forces that were children and youth in coal and metal mines ranged from 19 to 40%. A larger proportion of the work forces of coal mines used child labor underground while more children were found on the surface of metal mines “dressing the ores” (a process of separating the ore from the dirt and rock). By 1842 one-third of the underground work force of coal mines was under the age of 18 and one-fourth of the work force of metal mines were children and youth (1842[380]XV). In 1851 children and youth (under 20) comprised 30% of the total population of coal miners in Great Britain. After the Mining Act of 1842 was passed which prohibited girls and women from working in mines, fewer children worked in mines. The Reports on Sessions 1847-48 and 1849 Mining Districts I (1847-48[993]XXVI and 1849[1109]XXII) and The Reports on Sessions 1850 and 1857-58 Mining Districts II (1850[1248]XXIII and 1857-58[2424]XXXII) contain statements from mining commissioners that the number of young children employed underground had diminished.

The Reports on Sessions 1847-48 and 1849 Mining Districts I (1847-48[993]XXVI and 1849[1109]XXII) and The Reports on Sessions 1850 and 1857-58 Mining Districts II (1850[1248]XXIII and 1857-58[2424]XXXII) contain statements from mining commissioners that the number of young children employed underground had diminished.

In 1838, Jenkin (1927) estimates that roughly 5,000 children were employed in the metal mines of Cornwall and by 1842 the returns from The First Report show as many as 5,378 children and youth worked in the mines. In 1838 Lemon collected data from 124 tin, copper and lead mines in Cornwall and found that 85% employed children. In the 105 mines that employed child labor, children comprised from as little as 2% to as much as 50% of the work force with a mean of 20% (Lemon, 1838). According to Jenkin the employment of children in copper and tin mines in Cornwall began to decline by 1870 (1927, 309).

Explanations for Child Labor

The Supply of Child Labor

Given the role of child labor in the British Industrial Revolution, many economic historians have tried to explain why child labor became so prevalent. A competitive model of the labor market for children has been used to examine the factors that influenced the demand for children by employers and the supply of children from families. The majority of scholars argue that it was the plentiful supply of children that increased employment in industrial work places turning child labor into a social problem. The most common explanation for the increase in supply is poverty – the family sent their children to work because they desperately needed the income. Another common explanation is that work was a traditional and customary component of ordinary people’s lives. Parents had worked when they were young and required their children to do the same. The prevailing view of childhood for the working-class was that children were considered “little adults” and were expected to contribute to the family’s income or enterprise. Other less commonly argued sources of an increase in the supply of child labor were that parents either sent their children to work because they were greedy and wanted more income to spend on themselves or that children wanted out of the house because their parents were emotionally and physically abusive.

A competitive model of the labor market for children has been used to examine the factors that influenced the demand for children by employers and the supply of children from families. The majority of scholars argue that it was the plentiful supply of children that increased employment in industrial work places turning child labor into a social problem. The most common explanation for the increase in supply is poverty – the family sent their children to work because they desperately needed the income. Another common explanation is that work was a traditional and customary component of ordinary people’s lives. Parents had worked when they were young and required their children to do the same. The prevailing view of childhood for the working-class was that children were considered “little adults” and were expected to contribute to the family’s income or enterprise. Other less commonly argued sources of an increase in the supply of child labor were that parents either sent their children to work because they were greedy and wanted more income to spend on themselves or that children wanted out of the house because their parents were emotionally and physically abusive. Whatever the reason for the increase in supply, scholars agree that since mandatory schooling laws were not passed until 1876, even well-intentioned parents had few alternatives.

Whatever the reason for the increase in supply, scholars agree that since mandatory schooling laws were not passed until 1876, even well-intentioned parents had few alternatives.

The Demand for Child Labor

Other compelling explanations argue that it was demand, not supply, that increased the use of child labor during the Industrial Revolution. One explanation came from the industrialists and factory owners – children were a cheap source of labor that allowed them to stay competitive. Managers and overseers saw other advantages to hiring children and pointed out that children were ideal factory workers because they were obedient, submissive, likely to respond to punishment and unlikely to form unions. In addition, since the machines had reduced many procedures to simple one-step tasks, unskilled workers could replace skilled workers. Finally, a few scholars argue that the nimble fingers, small stature and suppleness of children were especially suited to the new machinery and work situations. They argue children had a comparative advantage with the machines that were small and built low to the ground as well as in the narrow underground tunnels of coal and metal mines. The Industrial Revolution, in this case, increased the demand for child labor by creating work situations where they could be very productive.

They argue children had a comparative advantage with the machines that were small and built low to the ground as well as in the narrow underground tunnels of coal and metal mines. The Industrial Revolution, in this case, increased the demand for child labor by creating work situations where they could be very productive.

Influence of Child Labor Laws

Whether it was an increase in demand or an increase in supply, the argument that child labor laws were not considered much of a deterrent to employers or families is fairly convincing. Since fines were not large and enforcement was not strict, the implicit tax placed on the employer or family was quite low in comparison to the wages or profits the children generated [Nardinelli (1980)]. On the other hand, some scholars believe that the laws reduced the number of younger children working and reduced labor hours in general [Chapman (1904) and Plener (1873)].

Despite the laws there were still many children and youth employed in textiles and mining by mid-century. Booth calculated there were still 58,900 boys and 82,600 girls under 15 employed in textiles and dyeing in 1881. In mining the number did not show a steady decline during this period, but by 1881 there were 30,400 boys under 15 still employed and 500 girls under 15. See below.

Booth calculated there were still 58,900 boys and 82,600 girls under 15 employed in textiles and dyeing in 1881. In mining the number did not show a steady decline during this period, but by 1881 there were 30,400 boys under 15 still employed and 500 girls under 15. See below.

Table 1: Child Employment, 1851-1881

| Industry & Age Cohort | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 |

| Mining Males under 15 | 37,300 | 45,100 | 43,100 | 30,400 |

| Females under 15 | 1,400 | 500 | 900 | 500 |

| Males 15-20 | 50,100 | 65,300 | 74,900 | 87,300 |

| Females over 15 | 5,400 | 4,900 | 5,300 | 5,700 |

| Total under 15 as % of work force | 13% | 12% | 10% | 6% |

| Textiles and Dyeing Males under 15 | 93,800 | 80,700 | 78,500 | 58,900 |

| Females under 15 | 147,700 | 115,700 | 119,800 | 82,600 |

| Males 15-20 | 92,600 | 92,600 | 90,500 | 93,200 |

| Females over 15 | 780,900 | 739,300 | 729,700 | 699,900 |

| Total under 15 as % of work force | 15% | 19% | 14% | 11% |

Source: Booth (1886, 353-399).

Explanations for the Decline in Child Labor

There are many opinions regarding the reason(s) for the diminished role of child labor in these industries. Social historians believe it was the rise of the domestic ideology of the father as breadwinner and the mother as housewife, that was imbedded in the upper and middle classes and spread to the working-class. Economic historians argue it was the rise in the standard of living that accompanied the Industrial Revolution that allowed parents to keep their children home. Although mandatory schooling laws did not play a role because they were so late, other scholars argue that families started showing an interest in education and began sending their children to school voluntarily. Finally, others claim that it was the advances in technology and the new heavier and more complicated machinery, which required the strength of skilled adult males, that lead to the decline in child labor in Great Britain. Although child labor has become a fading memory for Britons, it still remains a social problem and political issue for developing countries today.

References

Alfred (Samuel Kydd). The History of the Factory Movement. London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1857.

Booth, C. “On the Occupations of the People of the United Kingdom, 1801-81.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (J.S.S.) XLIX (1886): 314-436.

Chapman, S. J. The Lancashire Cotton Industry. Manchester: Manchester University Publications, 1904.

Clapham, Sir John. An Economic History of Modern Britain. Vol. I and II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1926.

Collier, Francis. The Family Economy of the Working Classes in the Cotton Industry, 1784-1833. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1964.

Cruickshank, Marjorie. Children and Industry. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1981.

Cunningham, Hugh. “The Employment and Unemployment of Children in England, c. 1680-1851.” Past and Present 126 (1990): 115-150.

Engels, Frederick. The Condition of the Working Class in England. Translated by the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, Moscow. London: E. J. Hobsbaum, 1969[1926].

Translated by the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, Moscow. London: E. J. Hobsbaum, 1969[1926].

Freudenberger, Herman, Francis J. Mather, and Clark Nardinelli. “A New Look at the Early Factory Labour Force.” Journal of Economic History 44 (1984): 1085-90.

Hammond, J. L. and Barbara Hammond. The Town Labourer, 1760-1832. New York: A Doubleday Anchor Book, 1937.

House of Commons Papers (British Parliamentary Papers):

1833(450)XX Factories, employment of children. R. Com. 1st rep.

1833(519)XXI Factories, employment of children. R. Com. 2nd rep.

1834(44)XXVII Administration and Operation of Poor Laws, App. A, pt.1.

1834(44)XXXVI Administration and Operation of Poor Laws. App. B.2, pts. III,IV,V.

1834 (167)XX Factories, employment of children. Supplementary Report.

1842[380]XV Children’s employment (mines). R. Com. 1st rep.

1847-48[993]XXVI Mines and Collieries, Mining Districts. Commissioner’s rep.

1849[1109]XXII Mines and Collieries, Mining Districts. Commissioner’s rep.

Commissioner’s rep.

1850[1248]XXIII Mining Districts. Commissioner’s rep.

1857-58[2424]XXXII Mines and Minerals. Commissioner’s rep.

House of Lords Papers:

1819(24)CX

Jenkin, A. K. Hamilton. The Cornish Miner: An Account of His Life Above and Underground From Early Times. London: George Allen and Unwin, Ltd., 1927.

Kussmaul, Ann. A General View of the Rural Economy of England, 1538-1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Lemon, Sir Charles. “The Statistics of the Copper Mines of Cornwall.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society I (1838): 65-84.

Marx. Karl. Capital. vol. I. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1909.

Nardinelli, Clark. Child Labor and the Industrial Revolution. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Nardinelli, Clark. “Were Children Exploited During the Industrial Revolution?” Research in Economic History 2 (1988): 243-276.

Nardinelli, Clark. “Child Labor and the Factory Acts.” Journal of Economic History. 40, no. 4 (1980): 739-755.

“Child Labor and the Factory Acts.” Journal of Economic History. 40, no. 4 (1980): 739-755.

Pinchbeck, Ivy. Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1800. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1930.

Plener, Ernst Elder Von. English Factory Legislation. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Redford, Arthur. Labour Migration in England, 1800-1850. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1926.

Rule, John. The Experience of Labour in Eighteenth Century English Industry. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981.

Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books, 1966.

Tilly, L. A. and Scott, J. W. Women, Work and Family. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1978.

Tuttle, Carolyn. “A Revival of the Pessimist View: Child Labor and the Industrial Revolution.” Research in Economic History 18 (1998): 53-82.

Tuttle, Carolyn. Hard at Work in Factories and Mines: The Economics of Child Labor During the British Industrial Revolution. Oxford: Westview Press, 1999.

Oxford: Westview Press, 1999.

Ure, Andrew. The Philosophy of Manufactures. London, 1835.

Webb, Sidney and Webb, Beatrice. Problems of Modern Industry. London: Longmanns, Green, 1898.

Citation: Tuttle, Carolyn. “Child Labor during the British Industrial Revolution”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. August 14, 2001. URL

http://eh.net/encyclopedia/child-labor-during-the-british-industrial-revolution/

Struggle for happy slavery - Money - Kommersant

90 years ago in the United States, the Hammer v. Dagenhart trial ended, as a result of which the country's first federal law prohibiting the use of child labor in enterprises was repealed. The most striking thing was that the initiator of its abolition was not a bourgeois exploiter, but a simple inhabitant of one-story America, who wanted his sons to work at the factory. The struggle against the exploitation of children has been going on with varying success for about 200 years, but so far it has been possible to eradicate it only in those countries where the industrial revolution has fully completed.

Labor reserves

At one time, stories about difficult working childhood were an integral part of the biography of Soviet figures of various levels. If the future responsible worker did not herd geese as a child or did not stand at the barre until late at night, it looked suspiciously bourgeois, so that the corresponding episodes were invented, even if they were not there. All the horrors of the exploitation of minors were unconditionally attributed to the inhuman cruelty of the tsarist regime and the bourgeois system. Soviet children, on the other hand, could study at school, and not work from morning to night, only thanks to the wisdom of the Soviet leadership. Meanwhile, the history of child labor in Europe and North America suggests that the most brutal exploitation of children occurred during the years of early industrialization. When the industry developed to a certain level, the use of child labor under the pressure of society came to naught. So the point here is in the general laws of development, and not in the innate defects of capitalism.

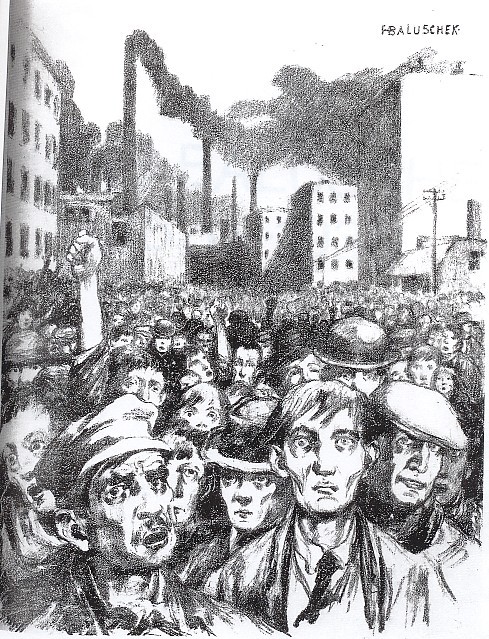

Children have been forced to work since time immemorial, but this work was usually quite feasible and even beneficial for health and general development. Picking up mushrooms and berries, grazing cattle, fetching water and other joys of rural life were, in fact, not so burdensome. But the beginning of the industrial revolution turned all European ideas about barefoot childhood upside down. This revolution began in England in the second half of the 18th century, and not everyone liked what it brought with it. English workers often grumbled against low wages, broke expensive factory machines in protest, or even crushed the sides of the manager. Employers dreamed of more obedient, more defenseless and, if possible, physically weak workers. The children were the best fit, and British entrepreneurs soon moved on to the mass recruitment of children between the ages of eight and fourteen.

Children got to the factories in two ways: either they were sent there by their parents, or, if there were no father and mother, shelters or workhouses were arranged with employers. Parents sent their children to the shops, of course, not from a good life, just poor families had nothing to live on. Even the children of more or less prosperous parents were not insured against employment. This happened, for example, with the future great writer Charles Dickens. The writer's father, John Dickens, was a clerk in a state institution and, as a person of an intelligent profession, was considered a gentleman. As befits a middle-class son, Charles went to school and could look forward to further education. But in 1824, John Dickens was unable to pay off his creditors and was thrown into the Marshalsea debtor's prison. To make ends meet, the family, which had eight children, sent Charles to work in a wax factory, where the future writer spent ten hours a day sticking labels on boxes of shoe polish for 6 shillings a week. Soon, however, the father was released from prison and took the boy from the factory, but difficult memories haunted Dickens all his life.

Parents sent their children to the shops, of course, not from a good life, just poor families had nothing to live on. Even the children of more or less prosperous parents were not insured against employment. This happened, for example, with the future great writer Charles Dickens. The writer's father, John Dickens, was a clerk in a state institution and, as a person of an intelligent profession, was considered a gentleman. As befits a middle-class son, Charles went to school and could look forward to further education. But in 1824, John Dickens was unable to pay off his creditors and was thrown into the Marshalsea debtor's prison. To make ends meet, the family, which had eight children, sent Charles to work in a wax factory, where the future writer spent ten hours a day sticking labels on boxes of shoe polish for 6 shillings a week. Soon, however, the father was released from prison and took the boy from the factory, but difficult memories haunted Dickens all his life.

In the case of the orphans, things were much simpler. Entrepreneurs practically bought them from workhouses and signed enslaving contracts with them, in fact turning them into slaves. So did, for example, George Cortold, the owner of a silk mill in Essex and a great liberal. Cortold was a zealous Protestant and a staunch opponent of all tyranny. He, being an Englishman, enthusiastically welcomed the American Revolution and even lived for several years in the USA, and later, having already returned to his homeland, supported the French Revolution in the same way. But all this did not prevent him from becoming a real slave owner. Cortold bought children, mostly girls, from workhouses in London, preferring to take them between the ages of 10 and 13. The businessman paid £5 per child immediately upon purchase, and then paid £5 a year later if the child was still alive. The workhouse undertook to provide the child with "a complete change of ordinary clothes." Having obtained another girl, Kortold entered into a separate contract with her, according to which the orphan was obliged to work in the factory until she was 21 years old, and the wages were 1 shilling 5d per week, while the adult worker received 7 shillings 2d.

Entrepreneurs practically bought them from workhouses and signed enslaving contracts with them, in fact turning them into slaves. So did, for example, George Cortold, the owner of a silk mill in Essex and a great liberal. Cortold was a zealous Protestant and a staunch opponent of all tyranny. He, being an Englishman, enthusiastically welcomed the American Revolution and even lived for several years in the USA, and later, having already returned to his homeland, supported the French Revolution in the same way. But all this did not prevent him from becoming a real slave owner. Cortold bought children, mostly girls, from workhouses in London, preferring to take them between the ages of 10 and 13. The businessman paid £5 per child immediately upon purchase, and then paid £5 a year later if the child was still alive. The workhouse undertook to provide the child with "a complete change of ordinary clothes." Having obtained another girl, Kortold entered into a separate contract with her, according to which the orphan was obliged to work in the factory until she was 21 years old, and the wages were 1 shilling 5d per week, while the adult worker received 7 shillings 2d. The well-established system failed only once. In 1814, several girls ran away from the factory and told about the brutal beatings that the factory clerk arranged. Kortold extinguished the scandal that had begun by firing the perpetrator of the beatings, and put his four daughters to oversee the labor process. It is not known whether the beatings have stopped at the factory, but the conversations there have definitely stopped. Cortold's daughters were as pious as he was, and therefore forced the workers to sing religious hymns during work and categorically forbade them to talk to each other. No one talked more about running away from the factory.

The well-established system failed only once. In 1814, several girls ran away from the factory and told about the brutal beatings that the factory clerk arranged. Kortold extinguished the scandal that had begun by firing the perpetrator of the beatings, and put his four daughters to oversee the labor process. It is not known whether the beatings have stopped at the factory, but the conversations there have definitely stopped. Cortold's daughters were as pious as he was, and therefore forced the workers to sing religious hymns during work and categorically forbade them to talk to each other. No one talked more about running away from the factory.

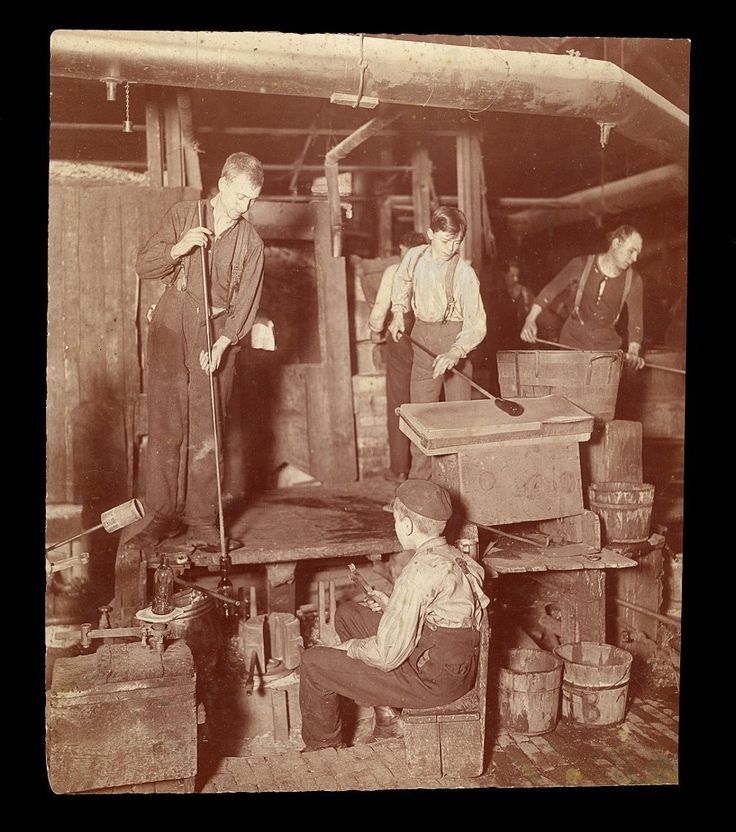

Happy childhood

Child labor was made possible by machines that even physically weak people could work with. At the same time, the technologies were so imperfect that it was possible to do without high qualification. For example, in cotton mills there were special professions - scavengers and knotters, which were almost entirely reserved for children. In general, only a child could be a scavenger, since the owner of this profession had to be small and agile. The scavengers had to crawl under the spinning looms all day and pick up pieces of cotton that fell on the floor. The newspaper The Lion wrote about one of these juvenile scavengers in 1828: “The first task of Robert Blinkow was to pick up cotton that fell on the floor. It would seem that it could be easier ... But the boy was very frightened by the movement and noise of the mechanisms. he did not like the cotton dust that hung in the air, because of which he quickly began to suffocate. He soon felt ill, and his back hurt. Blinkow tried to sit up, but this, as it turned out, was strictly prohibited in cotton mills. Manager Mr. Smith ordered him to stay on his feet. This work was not only tedious, but also quite dangerous. A juvenile scavenger from Manchester, David Rowland, said in 1832: “The scavenger has to sweep with a brush under the wheels ... I often had to crawl under the wheels, but they are moving all the time, and I could get into the car.

In general, only a child could be a scavenger, since the owner of this profession had to be small and agile. The scavengers had to crawl under the spinning looms all day and pick up pieces of cotton that fell on the floor. The newspaper The Lion wrote about one of these juvenile scavengers in 1828: “The first task of Robert Blinkow was to pick up cotton that fell on the floor. It would seem that it could be easier ... But the boy was very frightened by the movement and noise of the mechanisms. he did not like the cotton dust that hung in the air, because of which he quickly began to suffocate. He soon felt ill, and his back hurt. Blinkow tried to sit up, but this, as it turned out, was strictly prohibited in cotton mills. Manager Mr. Smith ordered him to stay on his feet. This work was not only tedious, but also quite dangerous. A juvenile scavenger from Manchester, David Rowland, said in 1832: “The scavenger has to sweep with a brush under the wheels ... I often had to crawl under the wheels, but they are moving all the time, and I could get into the car. I often had to lie down on my face so that I would not dragged on." Rowland began working as a scavenger at the age of six. The knotters walked around the workshop and sorted out the threads that went along the loom, and, as a contemporary calculated, in a day a child working in this position, moving around the workshop, walked about 24 miles.

I often had to lie down on my face so that I would not dragged on." Rowland began working as a scavenger at the age of six. The knotters walked around the workshop and sorted out the threads that went along the loom, and, as a contemporary calculated, in a day a child working in this position, moving around the workshop, walked about 24 miles.

Not only in the Cortold factory, but everywhere, children were paid significantly less than adults. One boy talked about the pay system that existed in his factory: “Eight-year-olds used to get 3 or 4 pence a day. Now an adult’s salary is divided into eight eighths: at 11 years old you are paid two eighths, at 13 three eighths, at 15 four, and at 20 already as an adult - 15 shillings. At the same time, the manufacturers insisted that the children should be grateful to them, since they provided them with food and clothing. The quality of the food, however, was debatable. A contemporary wrote: "The children were led into a spacious room with long narrow tables and wooden benches. They were ordered to sit at the tables, boys and girls separately. They were brought dinner - milk porridge, which for some reason looked completely blue."

They were ordered to sit at the tables, boys and girls separately. They were brought dinner - milk porridge, which for some reason looked completely blue."

Working conditions were also very difficult, although not more difficult than for adults. First of all, children suffered from a lack of safety, which was the difference between almost all enterprises in the first half of the 19th century. In 1832, 53-year-old worker John Ollet said: “As far as I know, accidents happen more often at the beginning of the day than in the evening. I saw one such case with my own eyes. The child worked with wool, that is, he prepared wool for the machine, but here his belt caught because he was half asleep, and dragged him into the car. Well, then we found him: one piece there, the other here. His whole body went through the car, cut him into pieces. "

In spite of all this, of course, the children did not grumble, they did not break cars and did not go on strikes. And yet, the factory administration sometimes applied very cruel measures to them. One young worker, for example, said: "When I was seven years old, I went to the factory of Mr. Marshals in Shrubary. If any boy was sleepy, the clerk would take him by the shoulder and say:" Come here. "And in the corner There was an iron tank with water in the room, he brings the boy to the tank, grabs him by the legs and dips his head into the tank, and then sends him back to work. Perhaps such a seemingly cruel procedure saved more than one young life from a terrible death, because sleepy workers really often died, but sometimes real sadists came across among the factory authorities. In 1849In 1999, the Ashton Chronicle published an interview with underage Sarah Carpenter, who spoke a lot about her managers: "The master carder was called Thomas Birx, but everyone called him Tom the Devil. how he lifted the skirts of adult girls 17 and 18 years old, threw them over his knee and flogged them in front of men and boys. Everyone was afraid of him ... One day he fell ill, and we hoped that he would die.

One young worker, for example, said: "When I was seven years old, I went to the factory of Mr. Marshals in Shrubary. If any boy was sleepy, the clerk would take him by the shoulder and say:" Come here. "And in the corner There was an iron tank with water in the room, he brings the boy to the tank, grabs him by the legs and dips his head into the tank, and then sends him back to work. Perhaps such a seemingly cruel procedure saved more than one young life from a terrible death, because sleepy workers really often died, but sometimes real sadists came across among the factory authorities. In 1849In 1999, the Ashton Chronicle published an interview with underage Sarah Carpenter, who spoke a lot about her managers: "The master carder was called Thomas Birx, but everyone called him Tom the Devil. how he lifted the skirts of adult girls 17 and 18 years old, threw them over his knee and flogged them in front of men and boys. Everyone was afraid of him ... One day he fell ill, and we hoped that he would die. While he was ill, they appointed him instead clerk William Hughes. He came up to me and asked why the machine stopped. I said I didn’t know, because I didn’t stop it. Hughes began to beat me with a cane, and I told him that I would tell all my mothers. Then he called the master. The master began to beat me on the head with a stick, so that I was covered in blood." Managers from that factory killed one woman after all, kicking her "where you can't kick."

While he was ill, they appointed him instead clerk William Hughes. He came up to me and asked why the machine stopped. I said I didn’t know, because I didn’t stop it. Hughes began to beat me with a cane, and I told him that I would tell all my mothers. Then he called the master. The master began to beat me on the head with a stick, so that I was covered in blood." Managers from that factory killed one woman after all, kicking her "where you can't kick."

Principle and the beggars

It cannot be said that the British public was completely uninterested in the conditions of life of working children. On the contrary, their position was regularly debated in Parliament from the early years of the 19th century. Already in 1802, a law was passed that limited the working day of orphans working in cotton spinning factories to 12 hours. Such solicitude was largely due to the fact that the landed aristocracy, who ruled in those years in British politics, was not too worried about the problems of the manufacturers, who were looked upon by many lords in those years as upstarts with dubious origins, who made a fortune in no less dubious ways. On the other hand, the aristocrats were sensitive to issues related to public morality, and the factory atmosphere, as many believed, had a corrupting effect on the youth. One doctor, in particular, wrote: "The combination under one factory roof of many young people of both sexes is an inexhaustible source of moral decay. Exposure to heated air, contacts between members of opposite sexes, observed examples of the manifestation of animal passions - all this contributes to the development of an extremely early sexual desire" . So factories in high society were viewed with great suspicion and, on occasion, were ready to come up with some kind of prohibition for their owners.

On the other hand, the aristocrats were sensitive to issues related to public morality, and the factory atmosphere, as many believed, had a corrupting effect on the youth. One doctor, in particular, wrote: "The combination under one factory roof of many young people of both sexes is an inexhaustible source of moral decay. Exposure to heated air, contacts between members of opposite sexes, observed examples of the manifestation of animal passions - all this contributes to the development of an extremely early sexual desire" . So factories in high society were viewed with great suspicion and, on occasion, were ready to come up with some kind of prohibition for their owners.

In 1818, another public campaign for the defense of morals led to the fact that the issue of child labor was considered in Parliament in detail. Doctors invited to the meetings of the special committee of the House of Lords, who had practice in industrial regions, reported on the state of health of working children. Doctors unanimously claimed that the children in the factories were as healthy as everyone else. For example, Dr. Edward Holm said that factory children are "no less healthy than other children from working families", and Dr. Thomas Turner assured that children working in cotton mills "make a generally good and healthy impression." Such medical unanimity was easily explained, because the called-up doctors conducted regular medical examinations in factories and received money from their owners for this. And yet in 1819In 1999, Parliament passed a law banning the employment of children under the age of 9 in cotton mills and establishing a 12-hour working day for those under 16 years of age.

Doctors unanimously claimed that the children in the factories were as healthy as everyone else. For example, Dr. Edward Holm said that factory children are "no less healthy than other children from working families", and Dr. Thomas Turner assured that children working in cotton mills "make a generally good and healthy impression." Such medical unanimity was easily explained, because the called-up doctors conducted regular medical examinations in factories and received money from their owners for this. And yet in 1819In 1999, Parliament passed a law banning the employment of children under the age of 9 in cotton mills and establishing a 12-hour working day for those under 16 years of age.

Finally, in the early 1830s, a movement began in the country to limit child labor. Among his inspirers, oddly enough, was the owner of the factory for the production of worsted fabric, John Wood, who could not expect any benefits from the campaign that had begun. One of the activists of the movement, Richard Oaster, recalled how it all began: “John Wood turned to me, shook my hand warmly and said: “Today I did not sleep all night. I read the Bible and every page condemned me. I won't let you leave until you promise to use all your influence to rid the factory system of all the cruelties we practice in our factories." Many, especially evangelicals, joined the movement for purely religious reasons, many for political reasons, such as MP John Hobhouse, who held radical views. Hobhouse introduced a bill in Parliament extending the provisions of the 1819 Actyears for all industries. The law was not passed then, but the struggle continued. Many members of the middle class, who were inspired by the novels of Charles Dickens, whose young heroes regularly suffered from the cruelty of the adult world, began to advocate for the restriction of child labor. Finally, workers who had an obvious economic interest joined the movement. Child labor was cheap, which brought down the price of adult labor, so that child care was beneficial to everyone who lived on one salary.

I read the Bible and every page condemned me. I won't let you leave until you promise to use all your influence to rid the factory system of all the cruelties we practice in our factories." Many, especially evangelicals, joined the movement for purely religious reasons, many for political reasons, such as MP John Hobhouse, who held radical views. Hobhouse introduced a bill in Parliament extending the provisions of the 1819 Actyears for all industries. The law was not passed then, but the struggle continued. Many members of the middle class, who were inspired by the novels of Charles Dickens, whose young heroes regularly suffered from the cruelty of the adult world, began to advocate for the restriction of child labor. Finally, workers who had an obvious economic interest joined the movement. Child labor was cheap, which brought down the price of adult labor, so that child care was beneficial to everyone who lived on one salary.

Soon, the children's protection movement had a clear leader - MP Michael Sadler. This man was perfect for this job. He was a Tory, that is, a defender of the interests of the aristocracy, so that the interests of the manufacturers did not bother him much. He had a strongly developed religious feeling. Suffice it to say that even in his youth he preached from the positions of the Methodist Church, for which representatives of the Anglican Church stoned him. Finally, he was a professional politician who had made a career of promoting socially oriented "poor laws" so that the workers knew and respected him. In 1832, Sadler headed a parliamentary commission investigating the state of child labor. The commission did a colossal job: factories were examined, children were interviewed, doctors were invited, ready to tell the truth. The final report was shocking, and in 1833 Parliament passed a law that limited the working day for the smallest (9-13 years old) 8 hours, and for seniors (14-18 years old) - 12 hours. But it extended only to the textile industry, so there was no complete victory.

This man was perfect for this job. He was a Tory, that is, a defender of the interests of the aristocracy, so that the interests of the manufacturers did not bother him much. He had a strongly developed religious feeling. Suffice it to say that even in his youth he preached from the positions of the Methodist Church, for which representatives of the Anglican Church stoned him. Finally, he was a professional politician who had made a career of promoting socially oriented "poor laws" so that the workers knew and respected him. In 1832, Sadler headed a parliamentary commission investigating the state of child labor. The commission did a colossal job: factories were examined, children were interviewed, doctors were invited, ready to tell the truth. The final report was shocking, and in 1833 Parliament passed a law that limited the working day for the smallest (9-13 years old) 8 hours, and for seniors (14-18 years old) - 12 hours. But it extended only to the textile industry, so there was no complete victory. And yet, since then, almost every five years, a law has been passed in England that in one way or another protected children from predatory exploitation. Finally, in 1878, the Factories and Workshops Act was passed, which for the first time forbade the employment of children under 10 years of age and extended this rule to all sectors of the British economy. At the same time, children under 14 could work no more than half the working day.

And yet, since then, almost every five years, a law has been passed in England that in one way or another protected children from predatory exploitation. Finally, in 1878, the Factories and Workshops Act was passed, which for the first time forbade the employment of children under 10 years of age and extended this rule to all sectors of the British economy. At the same time, children under 14 could work no more than half the working day.

This did not result in an economic collapse. Moreover, in the second half of the 19th century, the British economy felt very confident, and the wages of workers slowly but surely increased. Working parents could now provide their children with a piece of bread, and the need for child labor began to gradually disappear. All this, however, did not become possible until Britain had passed the initial stage of the industrial revolution.

Assembly salvo

Countries that lagged behind the UK in terms of industrial development later encountered the problem of child labor and later responded to it. Prussia was the first to regulate child employment, which banned in 1839employ children under 9 years of age. Other countries were not so quick: for example, the industrialized Belgium introduced such restrictions only in 1891. On the other side of the Atlantic, laws relating to child labor appeared a little earlier, but if in Prussia they were always strictly enforced, in the USA they were observed only when they really wanted to. For example, in Massachusetts, back in 1836, a law was passed according to which children under 15 years of age must spend at least three months a year in school. Naturally, no one followed the implementation of the law, just as no one followed the implementation of the law of the same state of 1842, which limited the work of children to 10 hours a day.

Prussia was the first to regulate child employment, which banned in 1839employ children under 9 years of age. Other countries were not so quick: for example, the industrialized Belgium introduced such restrictions only in 1891. On the other side of the Atlantic, laws relating to child labor appeared a little earlier, but if in Prussia they were always strictly enforced, in the USA they were observed only when they really wanted to. For example, in Massachusetts, back in 1836, a law was passed according to which children under 15 years of age must spend at least three months a year in school. Naturally, no one followed the implementation of the law, just as no one followed the implementation of the law of the same state of 1842, which limited the work of children to 10 hours a day.

The struggle for children's rights in the USA was dictated by approximately the same considerations as in England. There were religious moralists and ambitious politicians, but the main participants in campaigns for the protection of children were all the same hired workers who did not want underage competitors to bring down the price of labor. The initiative to restrict the labor of minors was taken up by the Working People Party, which in 1876 proposed a ban on the exploitation of children under 14 years old, the American Federation of Labor, which put forward a similar proposal in 1881, and many other organizations with frankly proletarian names. Individual states adopted separate laws, but in general, the matter did not move forward for a long time. Thus, the census of 1900 showed that half a million Americans aged 10 to 14 can neither read nor write, but are employed in the production process.

The initiative to restrict the labor of minors was taken up by the Working People Party, which in 1876 proposed a ban on the exploitation of children under 14 years old, the American Federation of Labor, which put forward a similar proposal in 1881, and many other organizations with frankly proletarian names. Individual states adopted separate laws, but in general, the matter did not move forward for a long time. Thus, the census of 1900 showed that half a million Americans aged 10 to 14 can neither read nor write, but are employed in the production process.

The public, as it should be, was indignant. In 1904, the National Committee on Child Labor was created in the United States, which fought for a happy childhood for all Americans. In 1908, the committee made an exceptional propaganda coup by sending an unknown schoolteacher, Lewis Hine, on a tour of the country. Hine was an amateur photographer, and during his two years of travel he collected a whole album of young textile workers, newspaper sellers, miners, shoe shiners and representatives of other professions. The captions under the photographs spoke for themselves: "Ferman Owens, 12 years old. Can't read. Doesn't know the ABCs. Says: 'Yes, I would like to study, but I can't because I'm at work all the time.'" Another caption read: “Some boys and girls are so small they have to climb onto looms,” and in the photograph itself, two boys of primary school age were balancing on a ledge of a loom that was twice their size. The photographs made a strong impression on contemporaries, and soon laws were passed in several states that limited the wage labor of minors. At 19In 16, the US Congress passed the Keating-Owen Act, which prohibited the sale of any goods in the production of which child labor was used. It was a major but temporary victory.

The captions under the photographs spoke for themselves: "Ferman Owens, 12 years old. Can't read. Doesn't know the ABCs. Says: 'Yes, I would like to study, but I can't because I'm at work all the time.'" Another caption read: “Some boys and girls are so small they have to climb onto looms,” and in the photograph itself, two boys of primary school age were balancing on a ledge of a loom that was twice their size. The photographs made a strong impression on contemporaries, and soon laws were passed in several states that limited the wage labor of minors. At 19In 16, the US Congress passed the Keating-Owen Act, which prohibited the sale of any goods in the production of which child labor was used. It was a major but temporary victory.

Not all Americans at that time believed that child labor was such a terrible evil. Least of all, of course, were the manufacturers, and especially the textile workers, inclined to agree with this. For example, the president of the Merchants Woolen Company, Charles Harding, believed that children belonged in a factory, not in a school: “There is a certain type of work that does not require much muscle strength and which a child can handle as well as an adult . .. Sometimes workers are too educated "I have seen many cases where an excess of education only spoils young workers." But among the supporters of child labor there were also indigenous proletarians. At 19In 1918, Roland Dagenhart, a North Carolina resident, challenged the Keating-Owen Act, which forbade his underage sons from working at the plant, through the courts. Dagenhart argued that Congress had violated his sons' constitutional right to work if they wanted to. The case reached the US Supreme Court, which found the act unconstitutional and overturned it, allowing thousands of children to return to their jobs.

.. Sometimes workers are too educated "I have seen many cases where an excess of education only spoils young workers." But among the supporters of child labor there were also indigenous proletarians. At 19In 1918, Roland Dagenhart, a North Carolina resident, challenged the Keating-Owen Act, which forbade his underage sons from working at the plant, through the courts. Dagenhart argued that Congress had violated his sons' constitutional right to work if they wanted to. The case reached the US Supreme Court, which found the act unconstitutional and overturned it, allowing thousands of children to return to their jobs.

The reason for the temporary defeat of the American fighters for the limitation of child labor was the same that prevented their English brethren from winning until 1878. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the United States had not yet reached a high level of industrial development, the country remained half agrarian, and it was too early to talk about the end of the industrial revolution. And while the industrial revolution is in full swing, no economy will want to abandon child labor. Only at 19In 1941, the decision in the Dagenhart case was reviewed and changed, and child labor was outlawed in the United States. But that was already a completely different era and a completely different America.

And while the industrial revolution is in full swing, no economy will want to abandon child labor. Only at 19In 1941, the decision in the Dagenhart case was reviewed and changed, and child labor was outlawed in the United States. But that was already a completely different era and a completely different America.

Call of the Jungle

After the Second World War, conventions and agreements came into fashion, which, according to their authors, are important for all mankind. In 1956, the UN adopted the Convention for the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Equivalent to Slavery, which included, in particular, the abolition of debt slavery. Indeed, in many of the then colonial states, children were given into debt slavery. However, after the adoption of the convention, the custom remained, as it remained after the independence of these countries. At 19In 1996, the well-known human rights organization Human Rights Watch released a report under the touching title "Little Hands of Slavery: Child Debt Slavery in India", and seven years later a new report - "Not Much Has Changed: Debt Slavery in India's Silk Industry". In general, child labor flourishes where it flourished in the time of Charles Dickens, in countries undergoing an industrial revolution.

In general, child labor flourishes where it flourished in the time of Charles Dickens, in countries undergoing an industrial revolution.

However, in countries where a full-fledged industrial revolution is still very far away, child labor is also intensively used. And some state child labor laws are so cleverly written that they can be easily circumvented. In Kenya, for example, the law strictly prohibits the employment of children under 16 in industrial enterprises, but allows them to be employed in the agricultural sector. Considering that there are not so many industrial enterprises in this country, the ban does not apply to anyone. Nepal is following the same path, where it is forbidden to hire persons under the age of 14, but the ban does not apply to plantations and brick-making enterprises. In addition to bricks, this country produces little.

Finally, on the world map there are countries like Togo, where children are not only forced to work, but even exported to neighboring countries. A human rights report states: "Togolese boys said they couldn't pay for school and agreed to go to farm work in Nigeria. According to them, they cleared land, plowed and sowed fields for 13 hours a day, complained of fatigue, they were beaten.Some were forced to cut tree branches with machetes, and many were seriously injured.After a period of eight months to two years, they were given a bicycle and ordered to go home to Togo.Boys were robbed by bandits, they had to bribe soldiers, and they returned home empty-handed. Some died and were buried along the road."

A human rights report states: "Togolese boys said they couldn't pay for school and agreed to go to farm work in Nigeria. According to them, they cleared land, plowed and sowed fields for 13 hours a day, complained of fatigue, they were beaten.Some were forced to cut tree branches with machetes, and many were seriously injured.After a period of eight months to two years, they were given a bicycle and ordered to go home to Togo.Boys were robbed by bandits, they had to bribe soldiers, and they returned home empty-handed. Some died and were buried along the road."

In a word, where there is poverty, there is also child labor, and no laws can help eradicate it. On the other hand, all industrialized countries that today can afford to do without it once went through the most brutal exploitation of their most vulnerable citizens.

KIRILL NOVIKOV

Child labor and the industrial revolution. Capitalism: An Unfamiliar Ideal

Child labor and the industrial revolution

Child labor is the most misunderstood and misunderstood aspect of the history of capitalism.

It is impossible to appreciate the phenomenon of child labor in England during the industrial revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries without realizing that the emergence of factories provided a livelihood, and therefore the opportunity to survive, for tens of thousands of children who in the pre-capitalist era were not destined to live to youth.

The factory system provided an increase in the general standard of living, a sharp drop in the death rate in cities, including children - and became the cause of an unprecedented population growth.

In 1750, the population of England was 6 million, in 1800 - 9 million, and in 1820 - 12 million: such growth has not been seen in any era. The age composition of the population has also changed enormously: the proportion of children and young people has increased dramatically. "The proportion of children born in London who died before reaching the age of five" fell from 74.5% in 1730-1749. up to 31.8% in 1810-1829. Children who were previously destined to die in infancy now have a chance.

Children who were previously destined to die in infancy now have a chance.

Population growth, as well as rising life expectancy, prove the falsity of the claims of socialists and fascists who criticize the capitalist system and claim that during the industrial revolution the standard of living of the working class fell significantly.

Capitalism's accusations of the poor living conditions of children during the industrial revolution are dishonest and historically illiterate: after all, it was capitalism that made it possible to significantly improve their living conditions compared to the previous era. The source of such injustice lies in the works of writers and poets as emotional as they are illiterate, like Dickens and Mrs. Browning, out of touch with the reality of the adepts of the Middle Ages like Southey, and political treatises, positioning themselves as experts in the history of economics, such as Marx and Engels. They all paint a vague and inviting image of the lost "golden age" of the working class, which they claim was destroyed by the Industrial Revolution. However, historians disagree with their claims. Both research and common sense have long since stripped the romantic veil from the pre-factory handicraft system. Under this system, the worker either had to make a substantial investment from the outset, or pay high rents for a loom or other machinery, while taking all the speculative risks. His diet was poor and monotonous, and survival often depended on whether his wife and children could find work. Not worth the envy and devoid of any romance, living together and working with the whole family in a poorly lit, insufficiently ventilated, poorly built house.