How to treat uti during pregnancy

Urinary Tract Infections During Pregnancy

JOHN E. DELZELL, JR., M.D., AND MICHAEL L. LEFEVRE, M.D., M.S.P.H.

This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(3):713-720

See related patient information handout on urinary tract infections during pregnancy, written by the authors of this article.

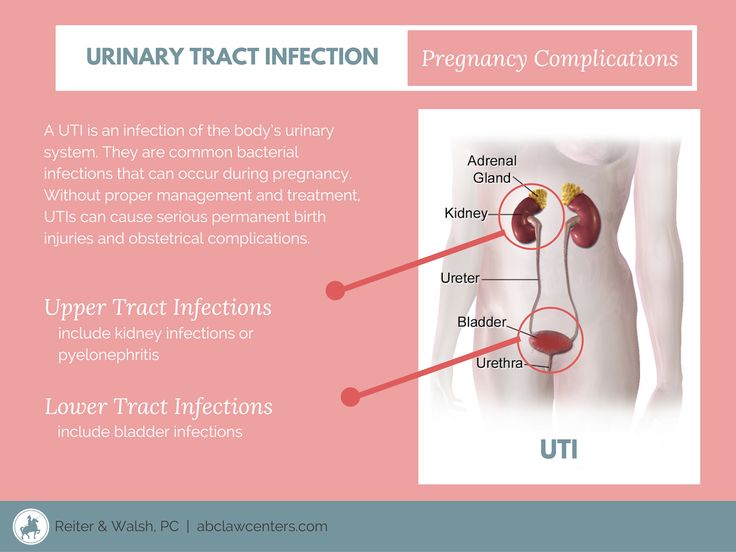

Urinary tract infections are common during pregnancy, and the most common causative organism is Escherichia coli. Asymptomatic bacteriuria can lead to the development of cystitis or pyelonephritis. All pregnant women should be screened for bacteriuria and subsequently treated with antibiotics such as nitrofurantoin, sulfisoxazole or cephalexin. Ampicillin should no longer be used in the treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria because of high rates of resistance. Pyelonephritis can be a life-threatening illness, with increased risk of perinatal and neonatal morbidity. Recurrent infections are common during pregnancy and require prophylactic treatment. Pregnant women with urinary group B streptococcal infection should be treated and should receive intrapartum prophylactic therapy.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are frequently encountered in the family physician's office. UTIs account for approximately 10 percent of office visits by women, and 15 percent of women will have a UTI at some time during their life. In pregnant women, the incidence of UTI can be as high as 8 percent. 1,2 This article briefly examines the pathogenesis and bacteriology of UTIs during pregnancy, as well as patient-oriented outcomes. We review the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis and pyelonephritis, plus the unique issues of group B streptococcus and recurrent infections.

1,2 This article briefly examines the pathogenesis and bacteriology of UTIs during pregnancy, as well as patient-oriented outcomes. We review the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis and pyelonephritis, plus the unique issues of group B streptococcus and recurrent infections.

Pathogenesis

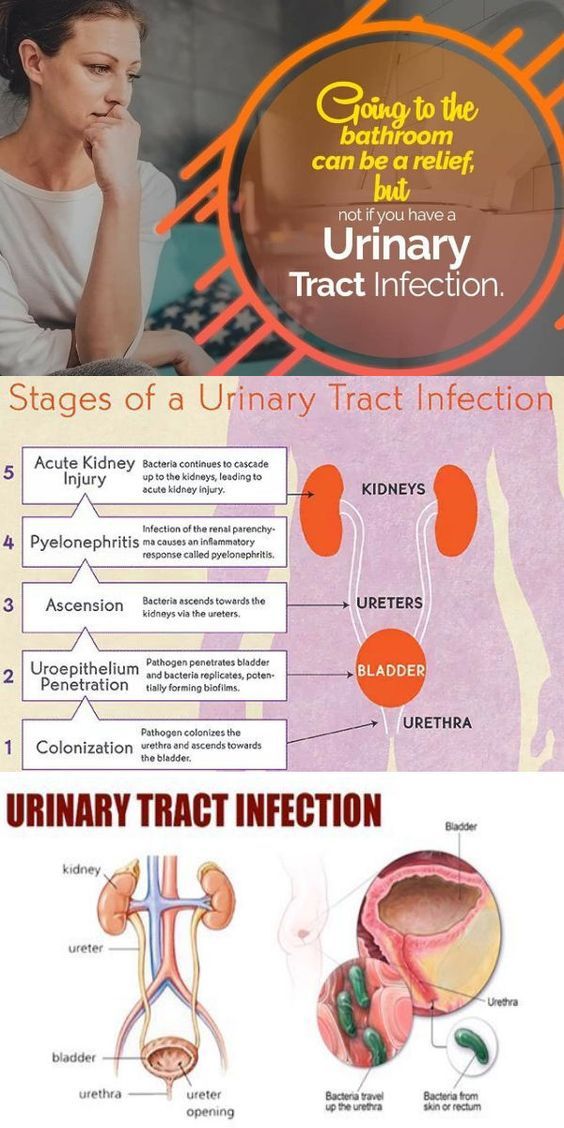

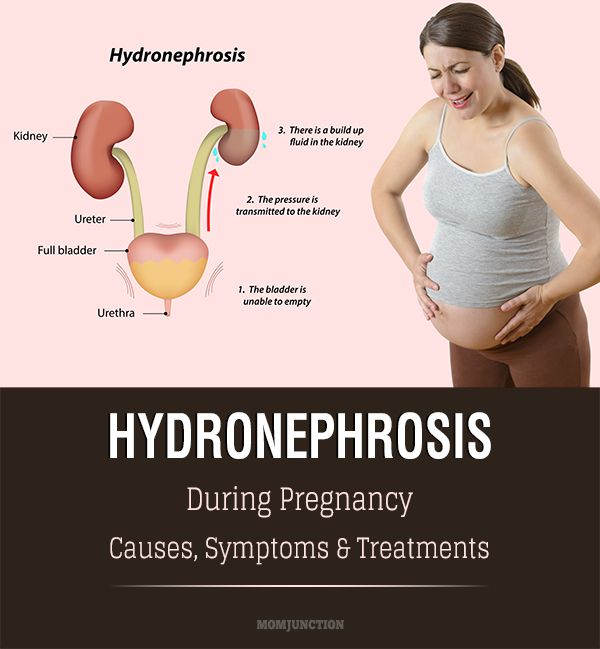

Pregnant women are at increased risk for UTIs. Beginning in week 6 and peaking during weeks 22 to 24, approximately 90 percent of pregnant women develop ureteral dilatation, which will remain until delivery (hydronephrosis of pregnancy). Increased bladder volume and decreased bladder tone, along with decreased ureteral tone, contribute to increased urinary stasis and ureterovesical reflux.1 Additionally, the physiologic increase in plasma volume during pregnancy decreases urine concentration. Up to 70 percent of pregnant women develop glycosuria, which encourages bacterial growth in the urine. Increases in urinary progestins and estrogens may lead to a decreased ability of the lower urinary tract to resist invading bacteria. This decreased ability may be caused by decreased ureteral tone or possibly by allowing some strains of bacteria to selectively grow.1,3 These factors may all contribute to the development of UTIs during pregnancy.

This decreased ability may be caused by decreased ureteral tone or possibly by allowing some strains of bacteria to selectively grow.1,3 These factors may all contribute to the development of UTIs during pregnancy.

Bacteriology

The organisms that cause UTIs during pregnancy are the same as those found in nonpregnant patients. Escherichia coli accounts for 80 to 90 percent of infections. Other gram-negative rods such as Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiella pneumoniae are also common. Gram-positive organisms such as group B streptococcus and Staphylococcus saprophyticus are less common causes of UTI. Group B streptococcus has important implications in the management of pregnancy and will be discussed further. Less common organisms that may cause UTI include enterococci, Gardnerella vaginalis and Ureaplasma ureolyticum.1,4,5

Diagnosis and Treatment of UTIs

UTIs have three principle presentations: asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis and pyelonephritis. The diagnosis and treatment of UTI depends on the presentation.

The diagnosis and treatment of UTI depends on the presentation.

ASYMPTOMATIC BACTERIURIA

[ corrected] Significant bacteriuria may exist in asymptomatic patients. In the 1960s, Kass6 noted the subsequent increased risk of developing pyelonephritis in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Significant bacteriuria has been historically defined as finding more than 105 colony-forming units per mL of urine.7 Recent studies of women with acute dysuria have shown the presence of significant bacteriuria with lower colony counts. This has not been studied in pregnant women, and finding more than 105 colony-forming units per mL of urine remains the commonly accepted standard. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is common, with a prevalence of 10 percent during pregnancy.6,8 Thus, routine screening for bacteriuria is advocated.

Untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria leads to the development of symptomatic cystitis in approximately 30 percent of patients and can lead to the development of pyelonephritis in up to 50 percent. 6 Asymptomatic bacteriuria is associated with an increased risk of intra-uterine growth retardation and low-birth-weight infants.9 The relatively high prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy, the significant consequences for women and for the pregnancy, plus the ability to avoid sequelae with treatment, justify screening pregnant women for bacteriuria.

6 Asymptomatic bacteriuria is associated with an increased risk of intra-uterine growth retardation and low-birth-weight infants.9 The relatively high prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy, the significant consequences for women and for the pregnancy, plus the ability to avoid sequelae with treatment, justify screening pregnant women for bacteriuria.

SCREENING

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends that a urine culture be obtained at the first prenatal visit.10 A repeat urine culture should be obtained during the third trimester, because the urine of treated patients may not remain sterile for the entire pregnancy.10 The recommendation of the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force is to obtain a urine culture between 12 and 16 weeks of gestation (an “A” recommendation).11

By screening for and aggressively treating pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria, it is possible to significantly decrease the annual incidence of pyelonephritis during pregnancy. 8,12 In randomized controlled trials, treatment of pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria has been shown to decrease the incidence of preterm birth and low-birth-weight infants.13

8,12 In randomized controlled trials, treatment of pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria has been shown to decrease the incidence of preterm birth and low-birth-weight infants.13

Rouse and colleagues14 performed a cost-benefit analysis of screening for bacteriuria in pregnant women versus inpatient treatment of pyelonephritis and found a substantial decrease in overall cost with screening. The cost of screening for bacteriuria to prevent the development of pyelonephritis in one patient was $1,605, while the cost of treating one patient with pyelonephritis was $2,485. Wadland and Plante15 performed a similar analysis in a family practice obstetric population and found screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria to be cost-effective.

The decision about how to screen asymptomatic women for bacteriuria is a balance between the cost of screening versus the sensitivity and specificity of each test. The gold standard for detection of bacteriuria is urine culture, but this test is costly and takes 24 to 48 hours to obtain results. The accuracy of faster screening methods (e.g., leukocyte esterase dipstick, nitrite dipstick, urinalysis and urine Gram staining) has been evaluated (Table 116). Bachman and associates16 compared these screening methods with urine culture and found that while it was more cost effective to screen for bacteriuria with the esterase dipstick for leukocytes, only one half of the patients with bacteriuria were identified compared with screening by urine culture. The increased number of false negatives and the relatively poor predictive value of a positive test make the faster methods less useful; therefore, a urine culture should be routinely obtained in pregnant women to screen for bacteriuria at the first prenatal visit and during the third trimester.10,11

The accuracy of faster screening methods (e.g., leukocyte esterase dipstick, nitrite dipstick, urinalysis and urine Gram staining) has been evaluated (Table 116). Bachman and associates16 compared these screening methods with urine culture and found that while it was more cost effective to screen for bacteriuria with the esterase dipstick for leukocytes, only one half of the patients with bacteriuria were identified compared with screening by urine culture. The increased number of false negatives and the relatively poor predictive value of a positive test make the faster methods less useful; therefore, a urine culture should be routinely obtained in pregnant women to screen for bacteriuria at the first prenatal visit and during the third trimester.10,11

The rightsholder did not grant rights to reproduce this item in electronic media. For the missing item, see the original print version of this publication.

TREATMENT

Pregnant women should be treated when bacteriuria is identified (Table 217,18). The choice of antibiotic should address the most common infecting organisms (i.e., gram-negative gastrointestinal organisms). The antibiotic should also be safe for the mother and fetus. Historically, ampicillin has been the drug of choice, but in recent years E. coli has become increasingly resistant to ampicillin.19 Ampicillin resistance is found in 20 to 30 percent of E. coli cultured from urine in the out-patient setting.20 Nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin) is a good choice because of its high urinary concentration. Alternatively, cephalosporins are well tolerated and adequately treat the important organisms. Fosfomycin (Monurol) is a new antibiotic that is taken as a single dose. Sulfonamides can be taken during the first and second trimesters but, during the third trimester, the use of sulfonamides carries a risk that the infant will develop kernicterus, especially preterm infants. Other common antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines) should not be prescribed during pregnancy because of possible toxic effects on the fetus.

The choice of antibiotic should address the most common infecting organisms (i.e., gram-negative gastrointestinal organisms). The antibiotic should also be safe for the mother and fetus. Historically, ampicillin has been the drug of choice, but in recent years E. coli has become increasingly resistant to ampicillin.19 Ampicillin resistance is found in 20 to 30 percent of E. coli cultured from urine in the out-patient setting.20 Nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin) is a good choice because of its high urinary concentration. Alternatively, cephalosporins are well tolerated and adequately treat the important organisms. Fosfomycin (Monurol) is a new antibiotic that is taken as a single dose. Sulfonamides can be taken during the first and second trimesters but, during the third trimester, the use of sulfonamides carries a risk that the infant will develop kernicterus, especially preterm infants. Other common antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines) should not be prescribed during pregnancy because of possible toxic effects on the fetus.

| Antibiotic | Pregnancy category | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Cephalexin (Keflex) | B | 250 mg two or four times daily |

| Erythromycin | B | 250 to 500 mg four times daily |

| Nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin) | B | 50 to 100 mg four times daily |

| Sulfisoxazole (Gantrisin) | C* | 1 g four times daily |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Augmentin) | B | 250 mg four times daily |

| Fosfomycin (Monurol) | B | One 3-g sachet |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) | C† | 160/180 mg twice daily |

A seven- to 10-day course of antibiotic treatment is usually sufficient to eradicate the infecting organism(s). Some authorities have advocated shorter courses of treatment—even single-day therapy. Conflicting evidence remains as to whether pregnant patients should be treated with shorter courses of antibiotics. Masterton21 demonstrated a cure rate of 88 percent with a single 3-g dose of ampicillin in ampicillin-sensitive isolates. Several other studies have found that a single dose of amoxicillin, cephalexin (Keflex) or nitrofurantoin was less successful in eradicating bacteriuria, with cure rates from 50 to 78 percent.1,22–24 Fosfomycin is effective when taken as a single, 3-g sachet.

Some authorities have advocated shorter courses of treatment—even single-day therapy. Conflicting evidence remains as to whether pregnant patients should be treated with shorter courses of antibiotics. Masterton21 demonstrated a cure rate of 88 percent with a single 3-g dose of ampicillin in ampicillin-sensitive isolates. Several other studies have found that a single dose of amoxicillin, cephalexin (Keflex) or nitrofurantoin was less successful in eradicating bacteriuria, with cure rates from 50 to 78 percent.1,22–24 Fosfomycin is effective when taken as a single, 3-g sachet.

Other antibiotics have not been extensively researched for use in UTIs, and further studies are necessary to determine whether a shorter course of other antibiotics would be as effective as the traditional treatment length.1 After patients have completed the treatment regimen, a repeat culture should be obtained to document successful eradication of bacteriuria.10

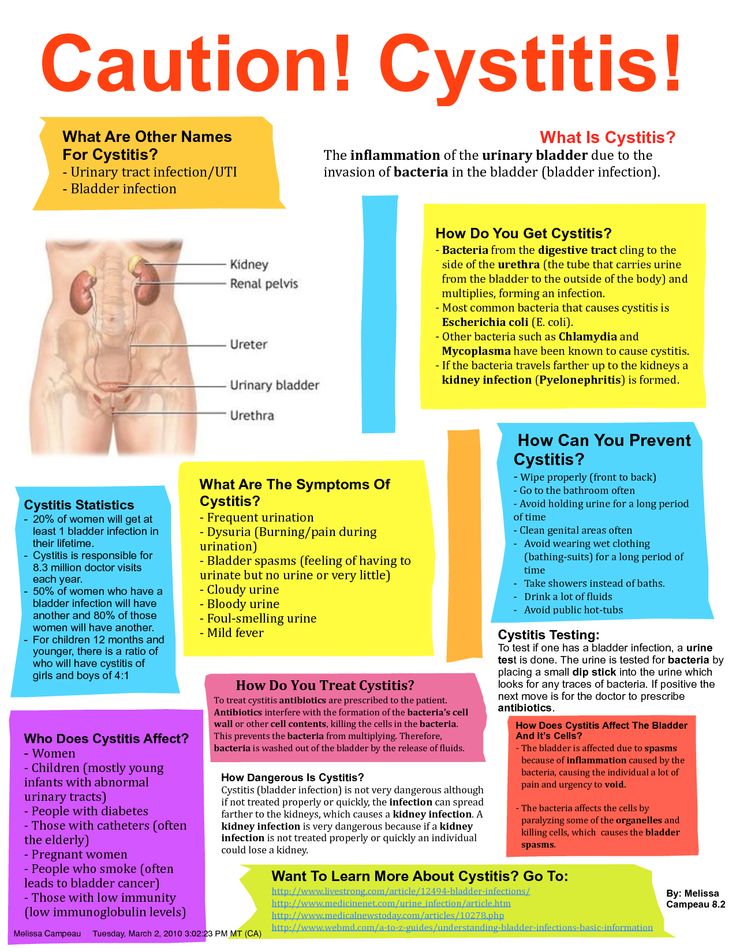

Acute Cystitis

Acute cystitis is distinguished from asymptomatic bacteriuria by the presence of symptoms such as dysuria, urgency and frequency in afebrile patients with no evidence of systemic illness. Up to 30 percent of patients with untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria later develop symptomatic cystitis.6 Over a six-year period, Harris and Gilstrap25 found that 1.3 percent of obstetric patients who delivered at a single hospital developed acute cystitis with no symptoms of pyelonephritis.

Up to 30 percent of patients with untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria later develop symptomatic cystitis.6 Over a six-year period, Harris and Gilstrap25 found that 1.3 percent of obstetric patients who delivered at a single hospital developed acute cystitis with no symptoms of pyelonephritis.

TREATMENT

In general, treatment of pregnant patients with acute cystitis is initiated before the results of the culture are available. Antibiotic choice, as in asymptomatic bacteriuria, should focus on coverage of the common pathogens and can be changed after the organism is identified and sensitivities are determined. A three-day treatment course in nonpregnant patients with acute cystitis has a cure rate similar to a treatment course of seven to 10 days, but this finding has not been studied in the obstetric population.1 Patients treated for a shorter time frame are more likely to have a recurrence of the infection. In the pregnant patient, this higher rate of recurrence with shorter treatment periods may have serious consequences. Table 217,18 lists oral antibiotics that are acceptable treatment choices. Group B streptococcus is generally susceptible to penicillin, but E. coli and other gram-negative rods typically have a high rate of resistance to this agent.

Table 217,18 lists oral antibiotics that are acceptable treatment choices. Group B streptococcus is generally susceptible to penicillin, but E. coli and other gram-negative rods typically have a high rate of resistance to this agent.

Pyelonephritis

Acute pyelonephritis during pregnancy is a serious systemic illness that can progress to maternal sepsis, preterm labor and premature delivery. The diagnosis is made when the presence of bacteriuria is accompanied by systemic symptoms or signs such as fever, chills, nausea, vomiting and flank pain. Symptoms of lower tract infection (i.e., frequency and dysuria) may or may not be present. Pyelonephritis occurs in 2 percent of pregnant women; up to 23 percent of these women have a recurrence during the same pregnancy.26

Early, aggressive treatment is important in preventing complications from pyelonephritis. Hospitalization, although often indicated, is not always necessary. However, hospitalization is indicated for patients who are exhibiting signs of sepsis, who are vomiting and unable to stay hydrated, and who are having contractions. A randomized study of 90 obstetric inpatients with pyelonephritis compared treatment with oral cephalexin to treatment with intravenous cephalothin (Keflin) and found no difference between the two groups in the success of therapy, infant birth weight or preterm deliveries.27

A randomized study of 90 obstetric inpatients with pyelonephritis compared treatment with oral cephalexin to treatment with intravenous cephalothin (Keflin) and found no difference between the two groups in the success of therapy, infant birth weight or preterm deliveries.27

Further support for outpatient therapy is provided in a randomized clinical trial that compared standard inpatient, intravenous treatment to outpatient treatment with intramuscular ceftriaxone (Rocephin) plus oral cephalexin.28 Response to antibiotic therapy in each group was similar, with no evident differences in the number of recurrent infections or preterm deliveries.

Antibiotic therapy (and intravenous fluids, if hospitalization is required) may be initiated before obtaining the results of urine culture and sensitivity. Several antibiotic regimens may be used. A clinical trial comparing three parenteral regimens found no differences in length of hospitalization, recurrence of pyelonephritis or preterm delivery. 29 Patients in this trial were randomized to receive treatment with intravenous cefazolin (Ancef), intravenous gentamycin plus ampicillin, or intramuscular ceftriaxone.

29 Patients in this trial were randomized to receive treatment with intravenous cefazolin (Ancef), intravenous gentamycin plus ampicillin, or intramuscular ceftriaxone.

Parenteral treatment of pyelonephritis should be continued until the patient becomes afebrile. Most patients respond to hydration and prompt antibiotic treatment within 24 to 48 hours. The most common reason for initial treatment failure is resistance of the infecting organism to the antibiotic. If fever continues or other signs of systemic illness remain after appropriate antibiotic therapy, the possibility of a structural or anatomic abnormality should be investigated. Persistent infection may be caused by urolithiasis, which occurs in one of 1,500 pregnancies,30 or less commonly, congenital renal abnormalities or a perinephric abscess.

Diagnostic tests may include renal ultrasonography or an abbreviated intravenous pyelogram. The indication to perform an intravenous pyelogram is persistent infection after appropriate antibiotic therapy when there is the suggestion of a structural abnormality not evident on ultrasonography. 30 Even the low-dose radiation involved in an intravenous pyelogram, however, may be dangerous to the fetus and should be avoided if possible.

30 Even the low-dose radiation involved in an intravenous pyelogram, however, may be dangerous to the fetus and should be avoided if possible.

Group B Streptococcal Infection

Group B streptococcal (GBS) vaginal colonization is known to be a cause of neonatal sepsis and is associated with preterm rupture of membranes, and preterm labor and delivery. GBS is found to be the causative organism in UTIs in approximately 5 percent of patients.31,32 Evidence that GBS bacteriuria increases patient risk of preterm rupture of membranes and premature delivery is mixed.33,34 A randomized, controlled trial35 compared the treatment of GBS bacteriuria with penicillin to treatment with placebo. Results indicated a significant reduction in rates of premature rupture of membranes and preterm delivery in the women who received antibiotics. It is unclear if GBS bacteriuria is equivalent to GBS vaginal colonization, but pregnant women with GBS bacteriuria should be treated as GBS carriers and should receive a prophylactic antibiotic during labor. 36

36

Recurrence and Prophylaxis

The majority of UTIs are caused by gastrointestinal organisms. Even with appropriate treatment, the patient may experience a reinfection of the urinary tract from the rectal reservoir. UTIs recur in approximately 4 to 5 percent of pregnancies, and the risk of developing pyelonephritis is the same as the risk with primary UTIs. A single, postcoital dose or daily suppression with cephalexin or nitrofurantoin in patients with recurrent UTIs is effective preventive therapy.37 A postpartum urologic evaluation may be necessary in patients with recurrent infections because they are more likely to have structural abnormalities of the renal system.26,30,38 Patients who are found to have urinary stones, who have more than one recurrent UTI or who have a recurrent UTI while on suppressive antibiotic therapy should undergo a postpartum evaluation.30,38

Outcomes

The maternal and neonatal complications of a UTI during pregnancy can be devastating. Thirty percent of patients with untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria develop symptomatic cystitis and up to 50 percent develop pyelonephritis.6 Asymptomatic bacteriuria is also associated with intrauterine growth retardation and low-birth-weight infants.9 Schieve and associates39 conducted a study involving 25,746 pregnant women and found that the presence of UTI was associated with premature labor (labor onset before 37 weeks of gestation), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (such as pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia), anemia (hematocrit level less than 30 percent) and amnionitis (Table 337). While this does not prove a cause and effect relationship, randomized trials have demonstrated that antibiotic treatment decreases the incidence of preterm birth and low-birth-weight infants.13 A risk of urosepsis and chronic pyelonephritis was also found.40 In addition, acute pyelonephritis has been associated with anemia.

Thirty percent of patients with untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria develop symptomatic cystitis and up to 50 percent develop pyelonephritis.6 Asymptomatic bacteriuria is also associated with intrauterine growth retardation and low-birth-weight infants.9 Schieve and associates39 conducted a study involving 25,746 pregnant women and found that the presence of UTI was associated with premature labor (labor onset before 37 weeks of gestation), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (such as pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia), anemia (hematocrit level less than 30 percent) and amnionitis (Table 337). While this does not prove a cause and effect relationship, randomized trials have demonstrated that antibiotic treatment decreases the incidence of preterm birth and low-birth-weight infants.13 A risk of urosepsis and chronic pyelonephritis was also found.40 In addition, acute pyelonephritis has been associated with anemia. 41

41

| Outcome | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal | ||||

| Low birth weight (weight less than 2,500 g [5 lb, 8 oz]) | 1.4 | 1.2 to 1.6 | ||

| Prematurity (less than 37 weeks of gestation at delivery) | 1.3 | 1.1 to 1.4 | ||

| Preterm low birth weight (weight less than 2,500 g and less than 37 weeks of gestation at delivery) | 1.5 | 1.2 to 1.7 | ||

| Maternal | ||||

| Premature labor (less than 37 weeks of gestation at delivery) | 1.6 | 1.4 to 1. 8 8 | ||

| Hypertension/preeclampsia | 1.4 | 1.2 to 1.7 | ||

| Anemia (hematocrit level less than 30%) | 1.6 | 1.3 to 2.0 | ||

| Amnionitis (chorioamnionitis, amnionitis) | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.9 | ||

Neonatal outcomes that are associated with UTI include sepsis and pneumonia (specifically, group B streptococcus infection).31,42 UTI increases the risk of low-birth-weight infants (weight less than 2,500 g [5 lb, 8 oz]), prematurity (less than 37 weeks of gestation at delivery) and preterm, low-birth-weight infants (weight less than 2,500 g and less than 37 weeks of gestation at delivery)39(Table 337).

Final Comment

UTIs during pregnancy are a common cause of serious maternal and perinatal morbidity; with appropriate screening and treatment, this morbidity can be limited. A UTI may manifest as asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis or pyelonephritis. All pregnant women should be screened for bacteriuria and subsequently treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy. Acute cystitis and pyelonephritis should be aggressively treated during pregnancy. Oral nitrofurantoin and cephalexin are good antibiotic choices for treatment in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis, but parenteral antibiotic therapy may be required in women with pyelonephritis.

A UTI may manifest as asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis or pyelonephritis. All pregnant women should be screened for bacteriuria and subsequently treated with appropriate antibiotic therapy. Acute cystitis and pyelonephritis should be aggressively treated during pregnancy. Oral nitrofurantoin and cephalexin are good antibiotic choices for treatment in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis, but parenteral antibiotic therapy may be required in women with pyelonephritis.

UTI During Pregnancy: How to Treat

UTI During Pregnancy: How to TreatMedically reviewed by Janine Kelbach, RNC-OB — By Chaunie Brusie on January 7, 2017

About halfway through my fourth pregnancy, my OB-GYN informed me that I had a urinary tract infection (UTI). I would need to be treated with antibiotics.

I was surprised I’d tested positive for a UTI. I had no symptoms, so I didn’t think that I could have an infection. The doctor discovered it based on my routine urine test.

After four pregnancies, I had started to think that they were just making us preggos pee in a cup for fun. But I guess there’s a purpose to it. Who knew?

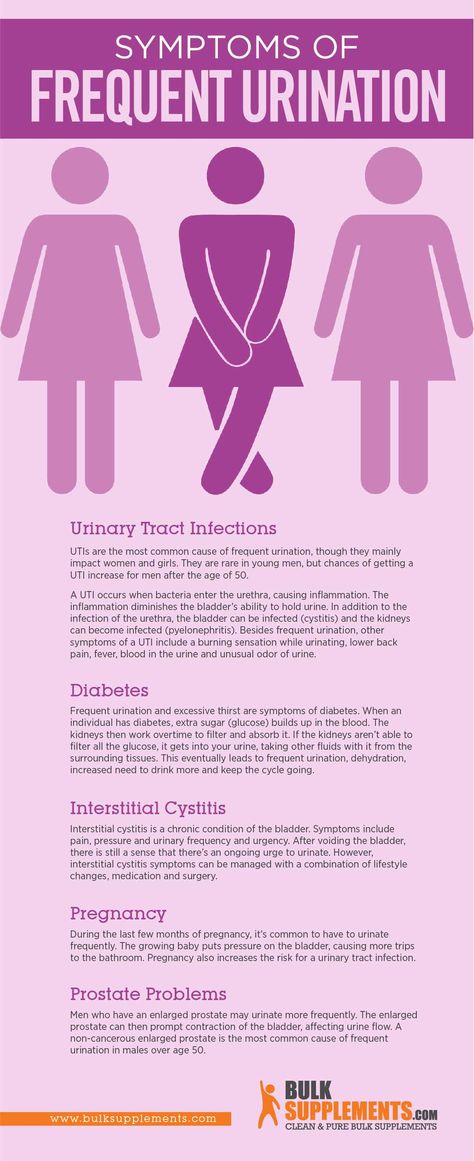

A UTI occurs when bacteria from somewhere outside of a woman’s body gets inside her urethra (basically the urinary tract) and causes an infection.

Women are more likely to get UTIs than men. The female anatomy makes it easy for bacteria from the vagina or rectal areas to get in the urinary tract because they are all close together.

UTIs are common during pregnancy. That’s because the growing fetus can put pressure on the bladder and urinary tract. This traps bacteria or causes urine to leak.

There are also physical changes to consider. As early as six weeks gestation, almost all pregnant women experience ureteral dilation, when the urethra expands and continues to expand until delivery.

The larger urinary tract, along with increased bladder volume and decreased bladder tone, all cause the urine to become more still in the urethra. This allows bacteria to grow.

This allows bacteria to grow.

To make matters worse, a pregnant woman’s urine gets more concentrated. It also has certain types of hormones and sugar. These can encourage bacterial growth and lower your body’s ability to fight off “bad” bacteria trying to get in.

Signs and symptoms of a UTI include:

- burning or painful urination

- cloudy or blood-tinged urine

- pelvic or lower back pain

- frequent urination

- feeling that you have to urinate frequently

- fever

- nausea or vomiting

Between 2 and 10 percent of pregnant women experience a UTI. Even more worrisome, UTIs tend to reoccur frequently during pregnancy.

Women who’ve had UTIs before are more prone to get them during pregnancy. The same goes for women who’ve had several children.

Any infection during pregnancy can be extremely dangerous for you and your baby. That’s because infections increase the risk of premature labor.

I found out the hard way that an untreated UTI during pregnancy can also wreak havoc after you deliver. After I had my first daughter, I woke up a mere 24 hours after coming home with a fever approaching 105˚F (41˚c).

After I had my first daughter, I woke up a mere 24 hours after coming home with a fever approaching 105˚F (41˚c).

I landed back in the hospital with a raging infection from an undiagnosed UTI, a condition called pyelonephritis. Pyelonephritis can be a life-threatening illness for both mother and baby. It had spread to my kidneys, and they suffered permanent damage as a result.

Moral of the story? Let your doctor know if you have any symptoms of a UTI during pregnancy. If you’re prescribed antibiotics, be sure to take every last pill to knock out that infection.

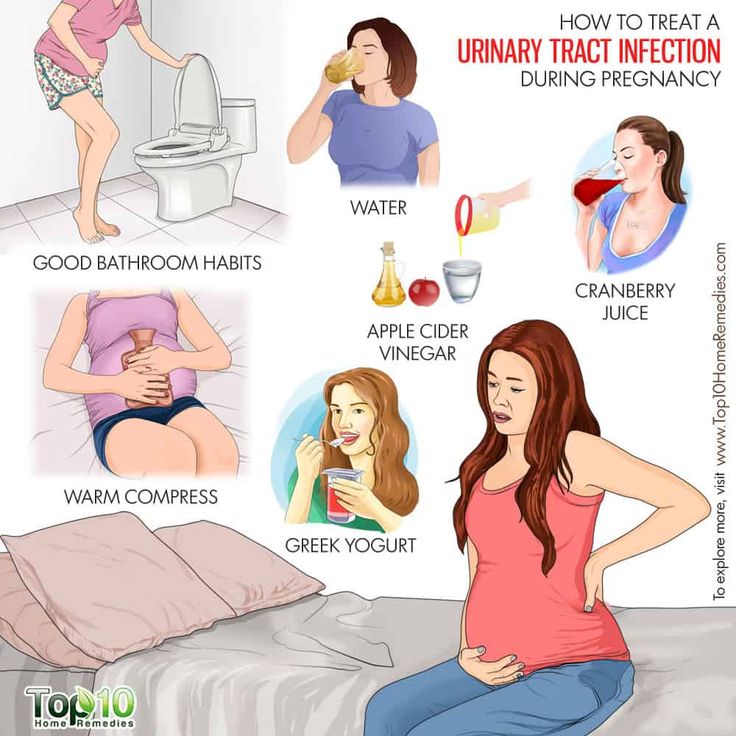

You can help prevent UTIs during your pregnancy by:

- emptying your bladder frequently, especially before and after sex

- wearing only cotton underwear

- nixing underwear at night

- avoiding douches, perfumes, or sprays

- drinking plenty of water to stay hydrated

- avoiding any harsh soaps or body wash in the genital area

Most UTIs during pregnancy are treated with a course of antibiotics. Your doctor will prescribe an antibiotic that is pregnancy-safe but still effective in killing off bacteria in your body.

Your doctor will prescribe an antibiotic that is pregnancy-safe but still effective in killing off bacteria in your body.

If your UTI has progressed to a kidney infection, you may need to take a stronger antibiotic or have an intravenous (IV) version administered.

Share on Pinterest

Last medically reviewed on January 8, 2017

- Parenthood

- Pregnancy

- Pregnancy Health

How we reviewed this article:

Healthline has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We avoid using tertiary references. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy.

- Chen YK, et al. (2010). No increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with urinary tract infections: A nationwide population‐based study. DOI:

10.3109/00016349.2010. 486826

486826 - Delzell JE, et al. (2000). Urinary tract infections during pregnancy.

aafp.org/afp/2000/0201/p713.html - Managing urinary tract infections in pregnancy. (2011).

bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2011/april/pregnant-uti.aspx - Matuszkiewicz-Rowinska J, et al. (2015). Urinary tract infections in pregnancy: Old and new unresolved diagnostic and therapeutic problems. DOOI:

10.5114/aoms.2013.39202 - Urinary tract infections (UTIs). (2015).

acog.org/~/media/For%20Patients/faq050.pdf/

Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available.

Share this article

Medically reviewed by Janine Kelbach, RNC-OB — By Chaunie Brusie on January 7, 2017

related stories

6 Home Remedies for Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Infections in Pregnancy

When to Be Concerned by Pregnancy Cramps

8 Ways To Get Rid of UTIs Without Antibiotics

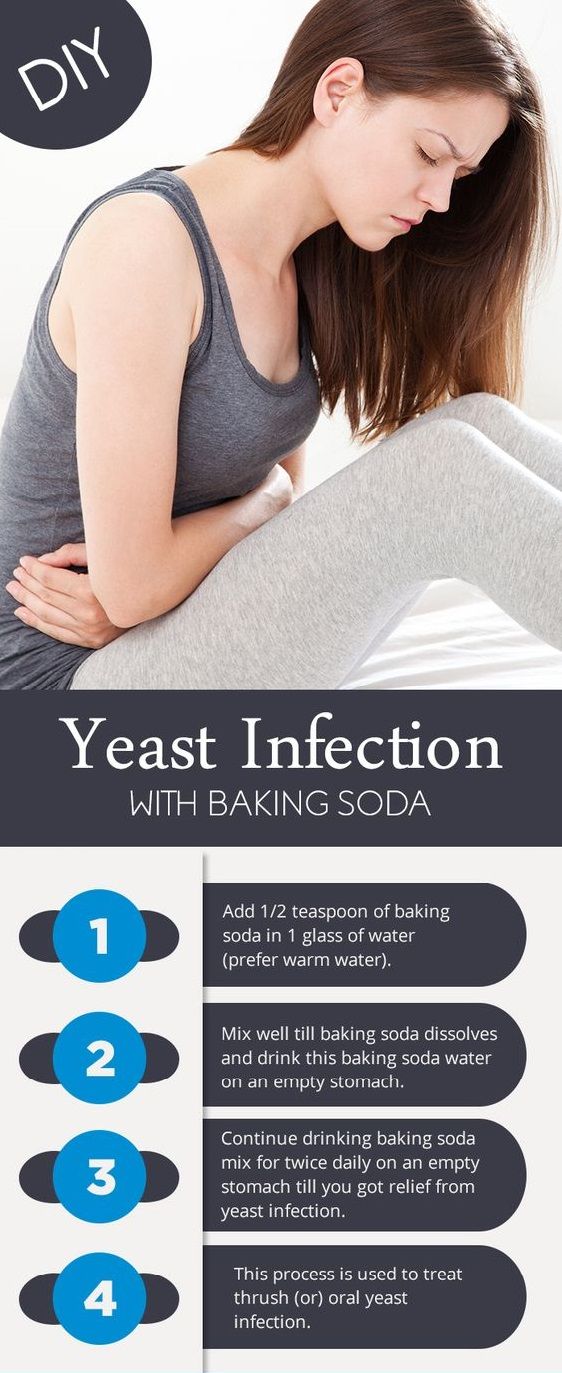

Can I Use Baking Soda to Treat a UTI?

Read this next

6 Home Remedies for Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Medically reviewed by Debra Sullivan, Ph.

D., MSN, R.N., CNE, COI

D., MSN, R.N., CNE, COILearn about six home remedies that can help prevent UTIs (urinary tract infections).

READ MORE

Infections in Pregnancy

Medically reviewed by Nicole Galan, RN

Pregnancy can make women more prone to infection. Here’s a list of common complications and options for treatment.

READ MORE

When to Be Concerned by Pregnancy Cramps

Medically reviewed by Debra Sullivan, Ph.D., MSN, R.N., CNE, COI

Normal stomach aches and pains are par for the course during pregnancy, but severe cramping can be dangerous. Here’s a look at when to be concerned.

READ MORE

8 Ways To Get Rid of UTIs Without Antibiotics

Medically reviewed by Alexandra Perez, PharmD, MBA, BCGP

Is treating a UTI without antibiotics possible? Because of antibiotic resistance, more and more people are seeking out alternative treatments for UTIs.

READ MORE

Can I Use Baking Soda to Treat a UTI?

Medically reviewed by Debra Rose Wilson, Ph.D., MSN, R.N., IBCLC, AHN-BC, CHT

Find out if baking soda can really help treat urinary infections, and learn why it may be dangerous.

READ MORE

Prenatal Care: Urinary Frequency and Thirst

Medically reviewed by University of Illinois

There are many symptoms that come with pregnancy. One is the seemingly never-ending urge to urinate – even if you’ve just gone a few minutes prior.

READ MORE

Irritable Uterus and Irritable Uterus Contractions: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment

Medically reviewed by Katie Mena, MD

Some women get regular contractions throughout pregnancy, meaning they have an irritable uterus. Here’s what’s normal and when to call your doctor.

READ MORE

Chronic Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

Medically reviewed by Graham Rogers, M.D.

Chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs) are infections of the urinary tract that don’t respond to treatment.

READ MORE

Why Am I Experiencing Urinary Incontinence?

Medically reviewed by Matt Coward, MD, FACS

Urinary incontinence happens when you lose control of your bladder. Discover potential causes, treatments, prevention tips, and more.

READ MORE

UTIs in Adults: Everything You Need to Know

Learn about different types and treatments of urinary tract infections, the risk factors, and prevention for both men and women.

READ MORE

Home - Seni

Home - Seni- Seni Club

- Where to buy

- Request a free sample

- Contacts

- Change country

- menu nine0004

Urological pads for women with mild to moderate urinary incontinence

More details

Urological pads for women with mild to moderate urinary incontinence

Urological inserts for men with mild to moderate urinary incontinence

More details

Urological inserts for men with mild to moderate urinary incontinence

A wide range of absorbent products for people in need of reliable protection. nine0027

nine0027

More

A wide range of absorbent products for people in need of reliable protection.

Absorbent briefs

Absorbent briefs for active people who need comfortable protection.

More

Absorbent briefs for active people who need comfortable protection.

skin care

Daily skin care products

More details

Cosmetics for daily skin care nine0027

A well-chosen product not only ensures the comfort of the person who uses it, but also avoids unnecessary costs.

Find product

It is important to choose the correct size of the product. An incorrectly selected size can lead not only to leakage, but even harm to health. Use the special "form" to select the correct size.

Find size

nine0026 Seni care products have been helping to properly care for skin that needs especially delicate care for many years. Depending on the purpose, conditions of use and individual characteristics of the skin, seni care cosmetics are conventionally divided into 2 areas: for specialized care and for the care of dry and sensitive skin. Informative packaging design, convenient color identification with special symbols make it easy to choose the right cosmetic product. nine0027Read more

Kegel exercises

MoreFrom problem to solution

Many men don't know where to start when they find themselves with urinary incontinence. Most often, they hide their problem by not going to the doctor or even telling their partner about it. nine0027

nine0027

Read more

MoreThe SeniControl mobile app is a handy tool with which you can easily monitor your urinary incontinence. The application will assess the degree of urinary incontinence and recommend the best urological product that will suit your needs.

Read more

Application available at:

nine0000 Bacteriuria, cystitis and pyelonephritis during pregnancy

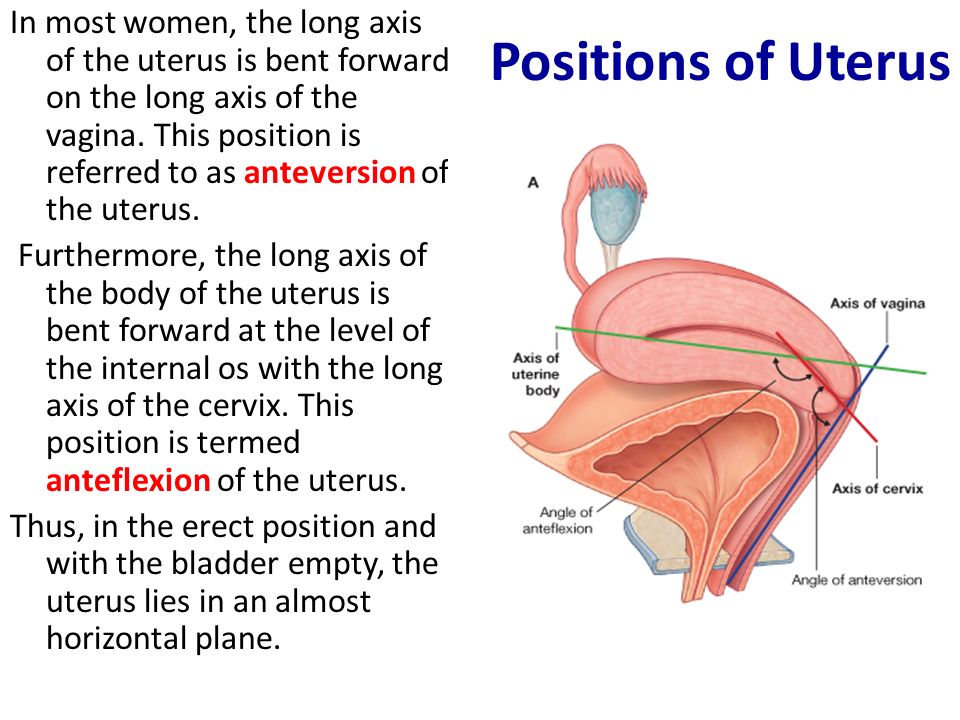

The human urinary system consists of two kidneys that filter the blood plasma and remove part of the liquid and some substances dissolved in it into the urine, two ureters that conduct urine from the kidneys to the bladder, the bladder that serves as a reservoir for urine, and the urethra through which urine is excreted from the body.

During pregnancy, several changes occur in the urinary system that increase the risk of urinary tract infections. The acidity of urine changes, urine becomes more alkaline (its pH rises), and this creates a more favorable environment for the development of bacteria, slows down the passage of urine and creates conditions for reflux (reverse reflux) of urine, so that bacteria can be transported with urine from the underlying sections to the overlying ones. , to the renal pelvis. In addition, perfectly normal during pregnancy changes in the functioning of the immune system also reduce the body's ability to fight infection.

The acidity of urine changes, urine becomes more alkaline (its pH rises), and this creates a more favorable environment for the development of bacteria, slows down the passage of urine and creates conditions for reflux (reverse reflux) of urine, so that bacteria can be transported with urine from the underlying sections to the overlying ones. , to the renal pelvis. In addition, perfectly normal during pregnancy changes in the functioning of the immune system also reduce the body's ability to fight infection.

Thus, we see that pregnant women are more predisposed to developing urinary tract infections than their non-pregnant peers.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the presence of bacteria in the urine without signs of inflammation.

Normally, our urine is sterile, and bacteria, even if they pass from the rectum to the bladder through the urethra, are washed out with the urine stream the next time we urinate. During pregnancy, very comfortable conditions are created for bacteria, and they can linger in the bladder, multiply, attach to the walls of the urinary tract, causing inflammation, and even throw into the renal pelvis. nine0027

During pregnancy, very comfortable conditions are created for bacteria, and they can linger in the bladder, multiply, attach to the walls of the urinary tract, causing inflammation, and even throw into the renal pelvis. nine0027

If bacteria and, in particular, nitrites, a product of the decomposition of urine urea by bacteria living in it, are detected in a general urine test during pregnancy, a urine culture is required to determine the pathogen, its amount (titer) and antibiotics to which it is sensitive.

Approximately thirty percent, that is, one in three pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria without treatment, develop gestational (pregnancy-related) pyelonephritis during the same pregnancy. Therefore, asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy always requires treatment. All urinary tract infections during pregnancy are treated antibacterial drugs.

Select drugs that are compatible with pregnancy and are safe enough for the fetus to be used at that time. The sensitivity of the pathogen to the antibiotic is also taken into account. Phytotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of urinary tract infections during pregnancy should not be used.

The sensitivity of the pathogen to the antibiotic is also taken into account. Phytotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of urinary tract infections during pregnancy should not be used.

Cystitis

Cystitis (inflammation of the bladder wall) during pregnancy usually manifests itself in a more erased form than outside it, less often there is very severe pain, less often cystitis is hemorrhagic - that is, blood in the urine is less often detected. Cystitis can also serve as the first step to the subsequent development of pyelonephritis, so cystitis during pregnancy also requires treatment with antibacterial drugs, herbal medicine in this case should not be used. nine0027

Gestational pyelonephritis

Gestational pyelonephritis, in which the inflammatory process is localized in the pelvis of the kidney or both kidneys, is a rather formidable disease that can lead to abortion, stillbirth and even threaten the life of the pregnant woman herself.