How to tell a child their grandparent has died

When a Loved One Dies: How to Help Your Child (for Parents)

When a loved one dies, children feel and show their grief in different ways. How kids cope with the loss depends on things like their age, how close they felt to the person who died, and the support they receive.

Here are some things parents can do to help a child who has lost a loved one:

Use simple words to talk about death. Be calm and caring when you tell your child that someone has died. Use words that are clear and direct. "I have some sad news to tell you. Grandma died today." Pause to give your child a moment to take in your words.

Listen and comfort. Every child reacts in their own way when they learn that a loved one has died. Some kids cry. Some ask questions. Others seem not to react at all. That's OK. Stay with your child to offer hugs or comfort. Answer your child's questions. Or just be together for a few minutes. It's OK if your child sees your sadness or tears.

Put feelings into words. Ask kids to say what they're thinking and feeling. Label some of your own feelings. This makes it easier for kids to share theirs. Say things like, "I know you're feeling very sad. I'm sad, too. We both loved Grandma so much, and she loved us too."

Tell your child what to expect. If the death of a loved one means changes in your child's life or routine, explain what will happen. This helps your child feel prepared. For example, "Aunt Sara will pick you up from school like Grandma used to." Or, "I need to stay with Grandpa for a few days. That means you and Dad will be home taking care of each other. But I'll talk to you every day, and I'll be back on Sunday."

Explain events that will happen. Allow children to join in rituals like viewings, funerals, or memorial services. Tell them ahead of time what will happen. For example, "Lots of people who loved Grandma will be there. We will sing, pray, and talk about Grandma's life. People might cry and hug. They might say to us, 'I'm sorry for your loss.' We can say, 'Thank you,' or, 'Thanks for coming.' You can stay near me and hold my hand if you want."

People might cry and hug. They might say to us, 'I'm sorry for your loss.' We can say, 'Thank you,' or, 'Thanks for coming.' You can stay near me and hold my hand if you want."

You might need to explain burial or cremation. For example, "After the funeral, there is a burial at a cemetery. The person's body is in a casket (or coffin) that gets buried in the ground with a special ceremony. This can feel like a sad goodbye, and people might cry." Share your family's beliefs about what happens to a person's soul or spirit after death.

Explain what will happen after the service, too. For example, "We all will go eat food together. People will laugh, talk, and hug some more. Talking about happy times with Grandma and being together helps people start to feel better."

Give your child a role. Having a small, active role lets kids feel part of things and helps them cope. You might invite your child to read a poem, pick a song to be played, gather some photos to display, or make something. Let kids decide if they want to take part, and how.

Let kids decide if they want to take part, and how.

Help your child remember the person. In the days and weeks ahead, encourage your child to draw pictures or write down stories of their loved one. Don't avoid talking about the person who died. Sharing happy memories helps heal grief.

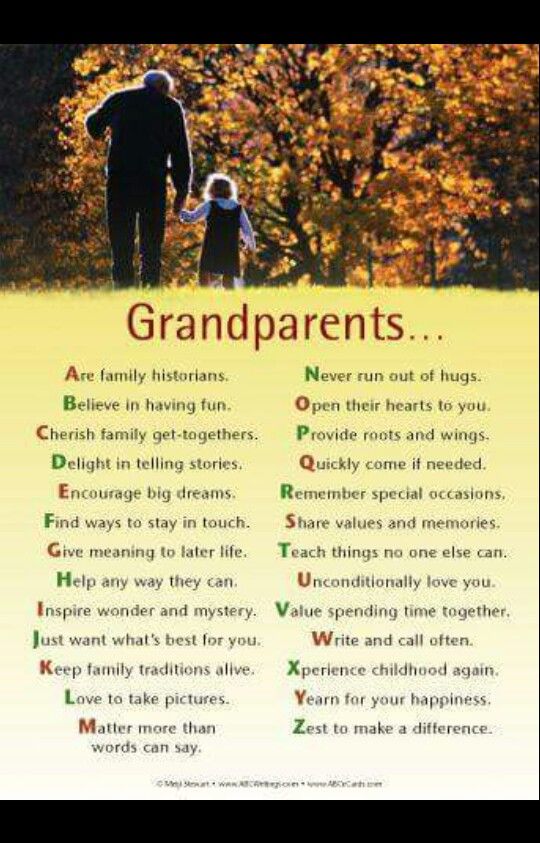

Give comfort and reassure your child. Notice if your child seems sad, worried, or upset in other ways. Ask about feelings and listen. Let your child know that it takes time to feel better after a loved one dies. Some kids may have trouble sleeping or have fears or worries. Let kids know these things will get better. Give them extra time and care. Support groups and counseling can help kids who need more support.

Help your child feel better. Provide the comfort your child needs but don't dwell on sad feelings. After a few minutes of talking and listening, shift to an activity or topic that helps your child feel a little better. Play, make art, cook, or go somewhere together.

Give your child time to heal from the loss. Grief is a process that happens over time. Be sure to talk often and listen to see how your child is feeling and doing. Healing doesn't mean forgetting about your loved one. It means remembering the person with love. Loving memories stir good feelings that support us as we go on to enjoy life.

Get more help if needed. If a loved one's death was sudden, deeply stressful, or violent, a child may need therapy to help them heal. If your child's distress lasts for more than a few weeks, or if you think your family needs more help, talk with your child's doctor. They can help you find the right therapist to work with.

Reviewed by: D'Arcy Lyness, PhD

Date reviewed: September 2021

How to Tell a Child Their Grandparent Died

Cake values integrity and transparency. We follow a strict editorial process to provide you with the best content possible. We also may earn commission from purchases made through affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Learn more in our affiliate disclosure.

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Learn more in our affiliate disclosure.

When you lose one of your parents, you may not know how to tell a child about the death of a grandparent. Your instincts may be to shelter them from the truth or to sugarcoat things to make the loss more bearable. But, it is possible to talk to kids about death in a clear and loving way that they'll understand.

Jump ahead to these sections:

- Step 1: Talk About the Death

- Step 2: What Happens Next

- Step 3: Ease Their Fear of Death

- Step 4: Spirituality and Death

- Step 5: Allow Time to Heal

Before having this conversation, consider the child's age, maturity level, and relationship to their grandparent who has died.

You can gauge the tone of the conversation by what you think your child is capable of accepting and understanding. It's useful to consider their emotional maturity level when deciding which words to use. Allow your child to ask questions as the conversation develops, and respond with clear and honest answers.

Allow your child to ask questions as the conversation develops, and respond with clear and honest answers.

Speaking clearly will help to avoid confusion and mixed emotions as your child processes that their grandparent has died. Below are some useful steps to help you work through this when the time is right.

Tip: Talking to your children about the death of their grandparent is one of many challenging tasks you might be facing. Our post-loss checklist can help guide you through the rest of that process.

Step 1: Talk About the Death

It may take a while for the news to sink in that your child's grandparent has died. Allow time for them to digest the information without overloading them with too much detail all at once. Depending on your child’s age, you may have to explain it a few times until they fully grasp that their grandparent is not coming back.

Take care not to use language that can be taken to mean that the grandparent is only temporarily away. For example, saying things like “Grandma has left us,” or “We’ll see her again soon,” may set the expectation that grandma will return at a future date.

For example, saying things like “Grandma has left us,” or “We’ll see her again soon,” may set the expectation that grandma will return at a future date.

» Did you know? Caskets can be bought online, without the funeral home markup. Find the perfect casket

Use clear language

Use comforting words. Don’t worry if you feel as if you don't know how to console someone. It’s understandable if you can’t find the right words to say, especially if you’ve never had to do it before.

When dealing with a child who has lost their grandparent, it’s useful if you choose words that comfort and reassure them. This doesn’t mean telling them that everything will be okay, or that things will go back to normal. It may be that things are not okay for a little while, and maybe things will never go back to “normal” for them.

Avoid euphemisms. Another thing to look out for is calling death by a name other than what it is. Using flowery language or softening what has happened may leave your child confused. This confusion may lead to later resentment because your child may think that you were keeping something from them as they mature and begin to understand death.

This confusion may lead to later resentment because your child may think that you were keeping something from them as they mature and begin to understand death.

Be clear and direct when explaining to your child that their grandparent has died. It may be difficult for them to process at first, but with time, they will begin to accept and understand their loss.

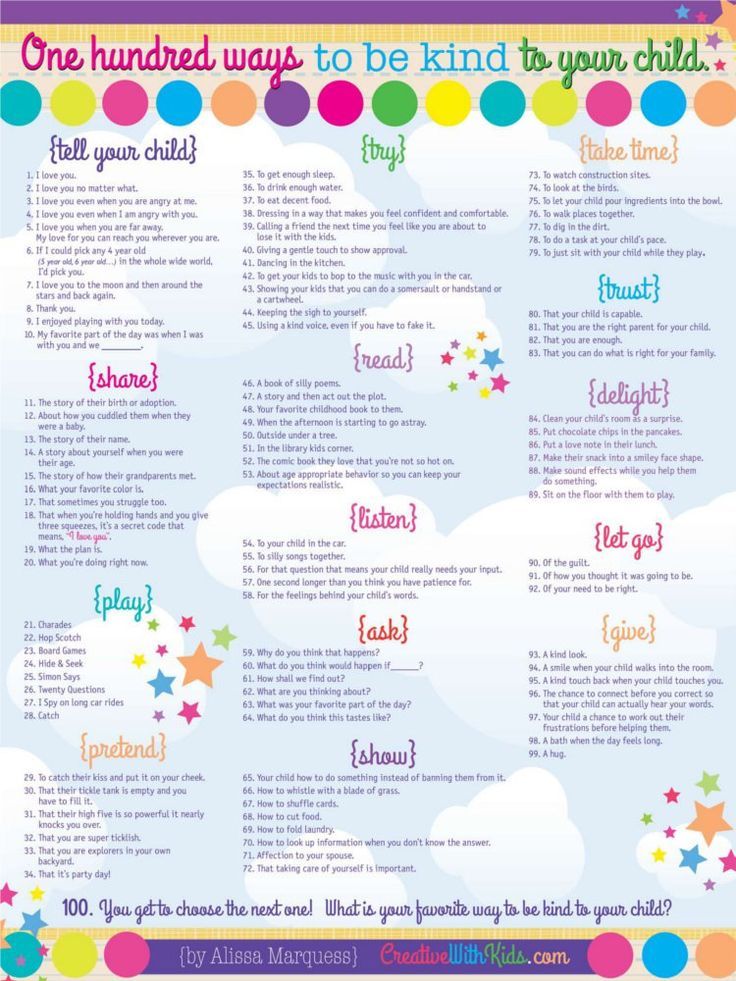

Explain feelings. One way of allowing your child to explore their feelings about the death of their grandparent is to encourage them to read children’s books about death.

There are free resources on death and dying available at your local public library suitable for young readers. You may consider sitting and reading these books to your child, or if they’re old enough, allowing them the time and space to read them whenever they’re ready.

It’s important to understand how your child wants to proceed with exploring their feelings toward death. They may prefer to sit and talk with you about it instead of reading it in a book. If this is the case, consider using the books as a conversation starter, or as a way to follow up on your discussion.

If this is the case, consider using the books as a conversation starter, or as a way to follow up on your discussion.

Set expectations

A child may not understand what is happening even after you sit and explain what death is to them. You can use other ways of easing them to show them how their life has changed.

For example, if their grandparent used to come to every dance recital, explain to them that is no longer possible and why. Give them alternatives as to who will now be there to watch their performances. It’s important to maintain your child’s schedule as normal as possible when going through your own grieving process.

Listen

It may be that your child starts to show signs of withdrawal, aggression, or acting out in ways that are unusual for them. These things are a normal part of grieving.

Sit with your child and try to determine what they're feeling and going through. Allow them the time and space needed for them to feel comfortable opening up to you. Sometimes all it takes is for them to know that they can count on you to listen whenever they feel like talking.

Sometimes all it takes is for them to know that they can count on you to listen whenever they feel like talking.

Not ready to start your will?

It's a big step and we get it! Share your email and we'll remind you in a few days.

Thank you for subscribing. Expect an email soon!

Step 2: What Happens Next

Depending on your child’s age, consider explaining what happens after death. When you explain to your child what a funeral is, it makes the entire process a little less scary.

Try explaining to them in words that they’ll understand what a viewing is, and why there'll be people there who are sad and may be crying. The more you prepare your child for what happens at a funeral, the less intimidated they will feel when the time comes.

If it helps to involve your child in the funeral planning process, assign them a simple yet important task like handing out pamphlets or water bottles to guests. Try not to force your child into doing anything at the funeral. They may not yet be emotionally mature enough to handle the responsibility when they are still trying to process their loss.

They may not yet be emotionally mature enough to handle the responsibility when they are still trying to process their loss.

Step 3: Ease Their Fear of Death

After everyone has gone home from the funeral, your child may be experiencing difficulties in accepting or understanding death in the days and weeks that follow. Try and understand that the way a child processes death is limited to their narrow experience with death and dying. They may ask a lot of questions that you aren’t prepared to answer or talk about when dealing with grief.

You may also be confronted with your child’s fear of dying or of mom and dad dying next. They may interpret their grandparent's death as being a precursor to their own death or that of their parents.

Your child may be feeling overwhelmed with grief and may have an elevated and irrational fear of death at this time. It helps to reassure them that this isn't how death happens. No one stands in line to be next, and that they won’t be placed on any list.

Step 4: Spirituality and Death

Explaining death to children from a spiritual standpoint will depend on your family’s spiritual and religious beliefs. Relying on faith-based texts to tell the story about what happens to us after we die may help guide you in what to say to your child to ease their fear of death.

They may also be experiencing death anxiety right about now. Explaining death through stories and parables may help ease those fears. These basic teachings may help you to further explain to your child what happens to us after we die.

You may want to take care not to plant a seed in your child’s mind of who “God chooses” to take from this earth. This may make them develop a fear of being “God’s chosen one,” and they may begin to act out in ways that are opposite of whatever that may be.

» MORE: You don't have to pay expensive funeral home prices for a casket! 10 Popular Places You Can Buy Caskets Online

Step 5: Allow Time to Heal

Although a child may be too young to fully grasp the concept of grief and loss, and needing time to go through a grieving process in order to heal — they will be faced with many of the same emotions that you might be feeling. It helps to continue having open talks with your child about having lost their grandparent, how they are feeling, and about how you might be able to help them cope with their grief.

It helps to continue having open talks with your child about having lost their grandparent, how they are feeling, and about how you might be able to help them cope with their grief.

You and your child can sit together and write personal letters to the grandparent that has died. You may want to encourage your child to write about their feelings, and encourage them to tell their grandparent how much they love and miss them. This can be a way for them to continue the bond they had with their grandparent and will help them in their healing process.

Another way to help your child with their grieving is to encourage them to draw pictures of their grandparent, how they remember them, and how they are feeling now that their grandparent has died. Sit and discuss these drawings with your child.

Allow them a chance to explain what they have drawn and what it means to them. Try not to criticize them or correct them in any way as they tell you about what they have been experiencing.

If you think that your child’s suffering and mourning is more than they can handle on their own or through the use of these types of healing activities, consider seeking professional counseling - either individually or in a group with other members of your immediate family.

Finding the Right Words to Say to a Child

Explaining the concept of death to a child can be complicated. Sometimes children will hide their true feelings and emotions thinking that they need to be strong for their mommies and daddies, especially if they witness their parents’ own suffering.

It’s okay to let your child know how much the death of their grandparent hurts you as well. Being open and honest about death and your own feelings of loss will help your child process their grief and accept their loss in time.

If you're looking to read more about kids and grief, read our guide on taking kids to funerals or memorial services.

How to talk to children about death: a brief instruction

How to answer a child's questions about death, why is it important not to bypass this topic and how not traumatic to explain to children that parents are also dying? Afisha Daily asked these and other questions to child psychologist Anfisa Belova.

Why is it important to explain to a child what death is?

Because death is an integral part of our lives. Every child encounters this sooner or later: in cartoons, books or real life, and he has questions. If he does not receive answers, then he starts to think on his own, and since he does not have the proper experience and knowledge, he uses only his own logic. Most often, the lack of answers causes a variety of fears : fear of one's own death, the death of loved ones, the unknown, something otherworldly (if he received answers on the topic of death from available sources - for example, mystical films). The child may have the feeling that something is being hidden from him or that he is being deceived.

At what age is it better to start a conversation?

Questions about life and death arise in children at the age of six or seven. When they appear, then it makes sense to talk about it. There are situations when a child faces death earlier - for example, if someone from relatives or a pet dies. Then, of course, you can start a conversation earlier.

Then, of course, you can start a conversation earlier.

How can I tell my child about the death of a loved one?

It is worth talking about this carefully, without any details and in the paradigm that the parent himself believes in. It is easier for someone to accept death through religion, for someone through theories about the soul, for someone through love and memory.

It is important to make the child understand that death is not something to be feared.

Despite the fact that a person is no longer in reality, he still remains in our memory.

It is necessary to explain to the child that you and he feel similar emotions: you can cry together, ask him how he feels. Sometimes it happens that there is anger at a person who is not around, both in adults and in children. These are emotions motivated by thoughts: “why did he leave us”, “why did he leave”, “I need him to be there, but he is not”. And that's okay too.

You can save some things of a loved one and explain the loss to the child through magical or even fabulous theses: for example, that a part of a loved one lives in these things or your memory of him. But by no means these conversations must not be hushed up and avoided, otherwise the child will have to experience this alone .

But by no means these conversations must not be hushed up and avoided, otherwise the child will have to experience this alone .

Sometimes parents say, "It's too early for you to know." And the child is left alone with this, because he cannot stop asking himself questions, especially if he sees sad parents or crying relatives around. And in this case, he is likely to experience much more fear than if the parent carefully explains to him what happened.

What are the best words and phrases to use?

At receptions with children, I talk about the concept of the soul - that when a person dies in the real world, he continues to live in us, in our love for him and our memory. Yes, we miss him, but we must understand that this person is not bad and not hurt, he is just somewhere not nearby. I try to set up the child so that sadness and sadness are translated into something bright - into memories, for example.

There are parents who do not believe in the concept of the soul and life after death, then you can explain from a biological point of view: this is how nature works, this is part of our life, and no one knows what will happen next. The main thing is to tell in such a way as not to cause a feeling of hopelessness in the child.

The main thing is to tell in such a way as not to cause a feeling of hopelessness in the child.

Why can't you lie to a child?

Some parents, fearing for their child, choose to lie. They say that a relative has gone somewhere far away and will not return. But you can't do that. The child can immediately understand that you are not telling him or deceiving him, then he will simply begin to lose confidence in you. And if after some time he finds out the truth, he may consider your act as a betrayal .

Will the child be afraid of such a conversation?

The bottom line is that parents are more afraid of questions about life and death. For adults, this topic is taboo because it causes pain, grief, a sense of loss. The child does not yet have such associations. If you present information to him calmly, competently, accurately, it will be just another answer to one of the many questions. And he won't be afraid of it.

Should I take my child to the funeral?

Everything is very individual: it depends on the traditions and worldviews of the family and on the personality of the child himself. In general, a funeral is far from a mandatory event for children; they can really scare. Moreover, this is not the only way to say goodbye to a person. That is, it is worth understanding why it is necessary to take a child to a funeral and whether there is any sense in this.

In general, a funeral is far from a mandatory event for children; they can really scare. Moreover, this is not the only way to say goodbye to a person. That is, it is worth understanding why it is necessary to take a child to a funeral and whether there is any sense in this.

On the other hand, for some children (usually those who are older) this can be a really important moment in saying goodbye to a loved one, and they themselves will show interest in the funeral.

How to tell a child about his inevitable death in the future?

Probably most often you have to talk about it if the child asks. And here, of course, there is no need to lie either. It is worth carefully explaining, for example, using the phrases: “Yes, this is a natural process, everyone dies, but it will not be soon”; “We will be together for a very long time”; "I won't leave you alone." It is important to make it clear that you will be with the child until he grows up and starts his own family, but even then you will still be there for him. You can shift the focus to conversations about life, about how much everything beautiful and amazing is in it.

You can shift the focus to conversations about life, about how much everything beautiful and amazing is in it.

In conversations with young children on serious topics, it is important to give information in doses, as they grow up, and not to overload immediately. In addition, a lot depends on what questions they ask. If you immediately say: “I don’t know when I will die, maybe tomorrow I will get hit by a car,” this can cause fear. At the same time, if it still seems like a hoax, it can always be formulated more accurately: "No one can know exactly when he will die, but usually this happens already in old age, when a person's life comes to an end."

At the first stages, it may be enough to believe that the parent will be around for a very long time and death will not happen soon. When, after some time, the child learns that people die not only from old age, that sometimes they die quite early, then this is a reason to answer the following questions.

How to tell a child about the death of a loved one?

105,219

Parents Teenagers

If a member of the family has died, the child should be told the truth. As life shows, all options like “Dad went on a business trip for six months” or “Grandma has moved to another city” can have negative consequences.

As life shows, all options like “Dad went on a business trip for six months” or “Grandma has moved to another city” can have negative consequences.

At first, the child simply won't believe you or think you're not telling the truth. Because he sees that something is wrong, that something has happened in the house: for some reason people are crying, mirrors are curtained, you can’t laugh out loud.

Children's fantasy is rich, and the fears it creates are quite real for the child. The child will decide that either he or someone in the family is in danger of something terrible. Real grief is clearer and easier than all the horrors that a child can imagine.

Secondly, the child will still be told the truth by “kind” uncles, other children or compassionate grandmothers in the yard. And it is still unknown in what form. And then the feeling that his relatives lied to him will be added to grief.

Who better to talk to?

The first condition: a person close to the child, the closest of all the remaining; the one who lived and will continue to live with the child; one who knows him well.

The second condition: the one who will speak must control himself in order to speak calmly, not break into hysterics or uncontrollable tears (those tears that well up in the eyes are not a hindrance). He will have to finish talking to the end and still be with the child until he realizes the bitter news.

To perform this task, choose a time and place when you will be "in a state of resource", and do not do this by relieving tension with alcohol. You can use light natural sedatives, such as valerian.

Adults are often afraid of being "black messengers"

It seems to them that they will hurt the child, cause pain. Another fear is that the reaction that the news will provoke will be unpredictable and terrible. For example, a scream or tears that an adult won't know how to deal with. All this is not true.

Alas, what happened happened. It was fate that struck, not the herald. The child will not blame the one who tells him about what happened: even small children distinguish between the event and the one who talks about it. As a rule, children are grateful to the one who brought them out of the unknown and provided support in a difficult moment.

As a rule, children are grateful to the one who brought them out of the unknown and provided support in a difficult moment.

Acute reactions are extremely rare, because the realization that something irreversible has happened, pain and longing come later, when the deceased begins to be missed in everyday life. The first reaction is, as a rule, amazement and attempts to imagine how it is: “died” or “died” ...

When and how to talk about death

It's better not to delay. Sometimes you have to take a little pause, because the speaker must calm down a little himself. But still, speak as quickly after the event as you can. The longer the child remains in the feeling that something bad and incomprehensible has happened, that he is alone with this unknown danger, the worse it is for him.

Choose a time when the child will not be overworked: when he has slept, eaten and does not experience physical discomfort. When the situation is as calm as possible under the circumstances.

Do it where you won't be interrupted or disturbed, where you can talk quietly. Do this in a familiar and safe place for the child (for example, at home), so that later he has the opportunity to be alone or use familiar and favorite things.

A favorite toy or other object can sometimes soothe a child better than words. A teenager can be hugged by the shoulders or taken by the hand. The main thing is that this contact should not be unpleasant for the child, and also that it should not be something out of the ordinary. If hugging is not accepted in your family, then it is better not to do anything unusual in this situation.It is important that at the same time he sees and listens to you, and does not look at the TV or the window with one eye. Establish eye-to-eye contact. Be short and simple.

In this case, the main information in your message should be duplicated. “Mom died, she is no more” or “Grandfather was sick, and the doctors could not help.

He died". Do not say “gone”, “fell asleep forever”, “left” - these are all euphemisms, metaphors that are not very clear to the child.

After that, pause. No more need to be said. Everything that the child still needs to know, he will ask himself.

What can the children ask?

Young children may be interested in technical details. Buried or not buried? Will the worms eat it? And then he suddenly asks: “Will he come to my birthday?” Or: “Dead? Where is he now?"

No matter how strange a question a child asks, do not be surprised, do not resent, and do not consider that these are signs of disrespect. It is difficult for a small child to immediately understand what death is. Therefore, he "puts in his head" what it is. Sometimes it gets pretty weird.

To the question: “Died - how is it? And what is he now? you can answer according to your own ideas about life after death. But in any case, do not be afraid. Do not say that death is a punishment for sins, and avoid explaining that it is “like falling asleep and not waking up”: the child may become afraid to sleep or watch other adults so that they do not sleep.

Children tend to ask anxiously, "Are you going to die too?" Answer honestly that yes, but not now and not soon, but later, “when you are big, big, when you have many more people in your life who will love you and whom you will love ...”.

Draw your child's attention to the fact that he has relatives, friends, that he is not alone, that he is loved by many people besides you. Say that with age there will be even more such people. For example, he will have a loved one, his own children.

The first days after the loss

After you have said the main thing - just silently stay by his side. Give your child time to absorb what they hear and respond. In the future, act in accordance with the reaction of the child:

- If he reacted to the message with questions, then answer them directly and sincerely, no matter how strange or inappropriate these questions may seem to you.

- If he sits down to play or draw, slowly join in and play or draw with him.

Do not offer anything, play, act according to his rules, the way he needs.

- If he cries, hug him or take his hand. If repulsive, say "I'm there" and sit next to you without saying or doing anything. Then slowly start a conversation. Say sympathetic words. Tell us about what will happen in the near future - today and in the coming days.

- If he runs away, don't go after him right away. Look at what he is doing in a short time, in 20-30 minutes. Whatever he does, try to determine if he wants your presence. People have the right to mourn alone, even very small ones. But this should be checked.

Don’t change your daily routine on this day, and in general at firstholidays. Let the food be ordinary and also the one that the child will eat. Neither you nor he has the strength to argue about “tasteless but healthy” on this day.

Sit with him a little longer before going to bed or, if necessary, until he falls asleep.

Let me leave the lights on if he's afraid. If the child is scared and asks to go to bed with you, you can take him to your place on the first night, but do not offer it yourself and try not to make it a habit: it’s better to sit next to him until he falls asleep.

Tell him what life will be like next: what will happen tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, in a week, in a month. Fame is comforting. Make plans and carry them out.

Participation in wakes and funerals

It is worth taking a child to funerals and wakes only if there is a person next to him whom the child trusts and who can only take care of him: take him away in time, calm him down if he cries.

Someone who can calmly explain to the child what is happening and protect (if necessary) from too insistent sympathy. If they begin to lament over the child “oh you are an orphan” or “how are you now” - this is useless.

In addition, you must be sure that the funeral (or commemoration) will take place in a moderate atmosphere - someone's tantrum can frighten a child.

Finally, you should take your child with you only if he wants to

Finally, you should take your child with you only if he wants toIt is quite possible to ask a child how he would like to say goodbye: to go to the funeral, or maybe it would be better for him to go to the grave with you later?

If you think it is better for the child not to attend the funeral and want to send him to another place, for example, to relatives, then tell him where he will go, why, who will be there with him and when you will pick him up. For example: “Tomorrow you will stay with your grandmother, because here a lot of different people will come to us, they will cry, and this is hard. I'll pick you up at 8 o'clock."

Of course, the people with whom the child stays should be, as far as possible, “their own”: those acquaintances or relatives to whom the child often visits and is familiar with their daily routine. Also agree that they treat the child “as always”, that is, they do not regret, do not cry over him.

The deceased member of the family performed some functions in relation to the child. Maybe he bathed or took away from kindergarten, or maybe it was he who read a fairy tale to the child before going to bed. Do not try to replace the deceased and return to the child all the lost pleasant activities. But try to save the most important, the lack of which will be especially noticeable.

Most likely, at these very moments, the longing for the departed will be more acute than usual. Therefore, be tolerant of irritability, crying, anger. To the fact that the child is unhappy with the way you do it, to the fact that the child wants to be alone and will avoid you.

A child has the right to grieve

Do not avoid talking about death. As the topic of death is “processed”, the child will come up and ask questions. This is fine. The child is trying to understand and accept very complex things, using the mental arsenal that he has.

The theme of death may appear in his games, for example, he will bury toys, in drawings.

Do not be afraid that at first these games or drawings will have an aggressive character: cruel “tearing off” the arms and legs of toys; blood, skulls, the predominance of dark colors in the drawings. Death has taken away a loved one from the child, and he has the right to be angry and “speak” with her in his own language.

Do not rush to turn off the TV if the theme of death flashes in a program or cartoon. Do not specifically remove books in which this topic is present. It may even be better if you have a "starting point" to talk to him again.

Do not try to distract from such conversations and questions. The questions will not disappear, but the child will go with them not to you or decide that something terrible is being hidden from him that threatens you or him.

Do not be afraid if a child suddenly starts saying something evil or bad about the deceasedEven in the crying of adults, the motif “whom did you leave us for” slips through.

Therefore, do not forbid the child to express his anger. Let him speak out, and only then repeat to him that the deceased did not want to leave him, but it just so happened. That no one is to blame. That the deceased loved him and, if he could, would never leave him.

On average, the period of acute grief lasts 6-8 weeks. If, after this time, the child does not leave fears, if he urinates in bed, grinds his teeth in a dream, sucks or bites his fingers, twists, tears his eyebrows or hair, swings in a chair, runs on tiptoe for a long time, is afraid to be without you even on a short time - all these are signals for contacting specialists.

If a child has become aggressive, pugnacious, or has begun to get minor injuries, if, on the contrary, he is too obedient, tries to stay near you, often says nice things to you or fawns - these are also reasons for alarm.

The main message: life goes on

Everything you say and do should carry one main message: “The grief has happened.

It's scary, it hurts, it's bad. And yet life goes on and everything will get better.” Reread this phrase again and say it to yourself, even if the deceased is so dear to you that you refuse to believe in life without him.

If you are reading this, you are a person who is not indifferent to children's grief. You have someone to support and something to live for. And you, too, have the right to your acute grief, you have the right to support, to medical and psychological assistance.

No one has yet died from grief itself: any grief, even the most terrible one, passes sooner or later, it is inherent in us by nature. But it happens that grief seems unbearable and life is given with great difficulty. Don't forget to take care of yourself too.

About the expert

Marina Travkova — psychologist, systemic family psychotherapist, member of the Society of Family Counselors and Psychotherapists.

The material was prepared on the basis of lectures by psychologist and psychotherapist Varvara Sidorova.