How to teach mild autistic child

6 Tips for Teaching Students With Autism

I remember pretty vividly the blank faces I would encounter when I was a kid and told people I had a family member with autism. This seemly changed overnight around the time I entered undergrad to embark on a career in special education. In the past decade or so, there’s been much more exposure and awareness of autism and its uniqueness. With the ever-growing population of children with autism, it's so important that all educators are well-versed on their needs. Here are six tips to help your students with autism thrive in the classroom.

Avoid sensory overload. Many unexpected things can be distracting to students with autism. Fluorescent lights, smells, and noises from other students can make it difficult for students with autism to concentrate. Using cool, calm colors in the classroom can help create a more relaxing atmosphere. Avoid covering the walls with too many posters or other things to look at. Some students may even benefit from their own center, where they can spend time away from any possible distractions.

Use visuals. Even individuals with autism who can read benefit from visuals. Visuals can serve as reminders about classroom rules, where certain things go, and resources that are available to students. Using pictures and modeling will mean more to students with autism than a lengthy explanation.

Be predictable. If you've ever been a substitute teacher, you know about the unspoken anxiety of being with a different class (sometimes in a different school) every day. Having predictability in the classroom eases anxiety for students with autism and will help avoid distraction. Students are less worried or curious about what will happen next and can better focus on the work at hand. Give your student a schedule that they can follow. If there are any unpredictable changes, it’s a great teaching moment to model how to handle changes appropriately.

Keep language concrete. Do any of you children of the 90’s remember the show “Bobby’s World” with Howie Mandell? Bobby would always overhear adults using figurative language and daydream of all these crazy scenarios about what he thought they meant. Many individuals with autism have trouble understanding figurative language and interpret it in very concrete terms. This may serve as a great opportunity to teach figurative language and hidden meanings in certain terms.

Many individuals with autism have trouble understanding figurative language and interpret it in very concrete terms. This may serve as a great opportunity to teach figurative language and hidden meanings in certain terms.

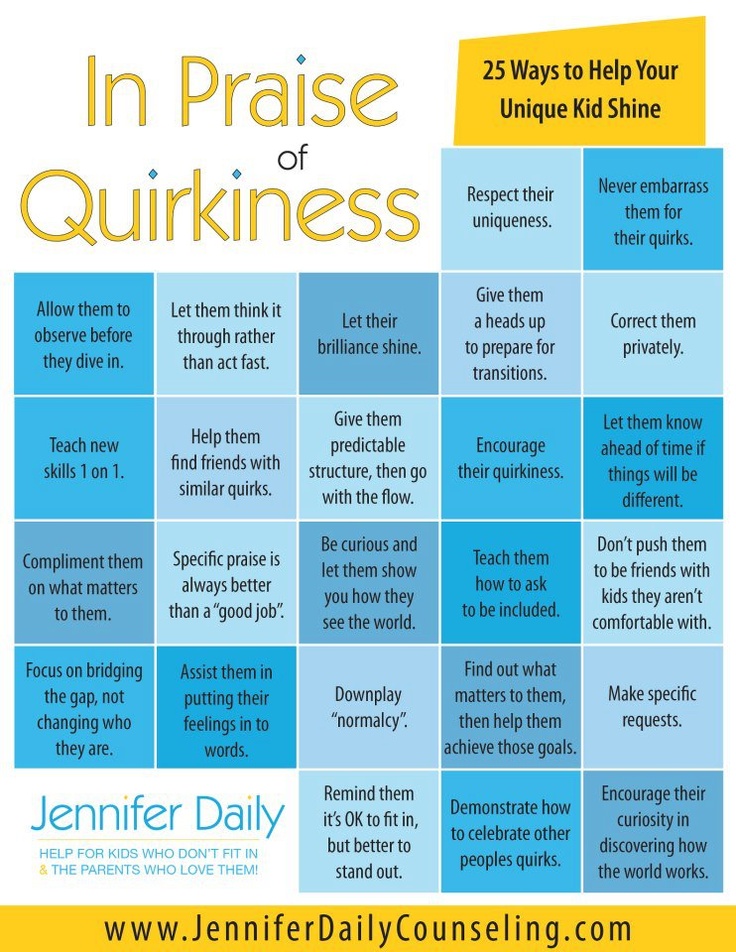

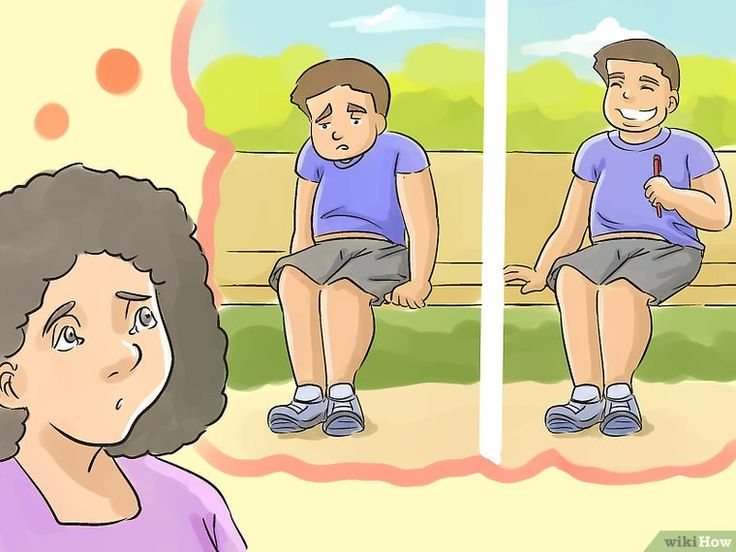

Directly teach social skills. The hidden curriculum may be too hidden for some individuals with autism. There are certain things that may have to be explicitly taught (like analogies). Model appropriate social skills and discuss how our behavior can make others feel. Social Thinking is a great curriculum with pictures books such as You Are a Social Detective that explain social skills in an easy to understand way.

Treat students as individuals. I’m sure this goes without saying, but I’m going to say it: It’s so important to model patience, understanding, and respect when working in a classroom with any special learners. Celebrate their success and don’t sweat it if some accommodations don’t conform to what you are used to in the classroom. Keep in mind that some of these recommendations may be super helpful for some students, while others may not need the same degree of consideration. Autism can affect individuals differently.

Keep in mind that some of these recommendations may be super helpful for some students, while others may not need the same degree of consideration. Autism can affect individuals differently.

To learn more about working with students with autism, visit The Autism Vault.

10 Effective Tips for Teaching Children With Autism in 2022

Feb 03 2021

Positive Action Staff

•

Special Education

“It’s impossible to handle her.”

“He’s totally disruptive and creates a ruckus in my class.”

“What an attention seeker!”

“Do you think she should be attending regular school?”

“He can’t sit still, even for a moment.”

“I don’t think he’s capable of learning.”

These are some of the commonly heard frustrations that come with teaching students with autism.

But what if we tried to understand how the student with autism feels? What if we attributed their behavior to a different brain wiring instead of deliberate disruption?

Not abnormal or dysfunctional – just different.

This better explains their hyperactivity, anxiety, and inability to connect with other children. These behaviors are a cry for help — your help.

At Positive Action, our committee partners with educators by providing schools with the right tools to develop special ed curriculums catered to students with autism.

“What I love most about Positive Action is the way it pertains to the real issues students face in today's world!” — Lori Kessinge, 5th Grade Teacher, Critzer Elementary School, Virginia

What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

ASD is a child developmental disorder that causes significant challenges in social skills, communication, and behavior in young children — and lasts into adulthood.

The learning, thinking, and problem-solving abilities of students with autism can range from gifted to severely challenged. Thus, some require more help in their daily lives while others need less.

An ASD diagnosis now includes several conditions that used to be diagnosed separately:

These conditions are now collectively referred to as autism spectrum disorder.

Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Students with autism have a wide range of abilities and characteristics — no two children appear or behave the same way. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and often change over time.

Characteristics of ASD fall into two categories:

Social Interaction and Communication Problems

-

Challenges with normal back-and-forth conversation

-

Decreased desire to share personal interests or emotions

-

Difficulty understanding or responding to social cues like eye contact and facial expressions

-

Challenges in developing/maintaining/understanding relationships (trouble building friendships)

Restricted and Repetitive Patterns of Behaviors, Interests, or Activities

-

Hand-flapping and toe-walking

-

Speaking in a unique way — using odd patterns or pitches in speaking or “scripting” from favorite shows

-

Exhibiting intense interest in activities that are uncommon for a similarly aged child

-

Expressing their sensual responses uncommonly or extremely, like indifference to pain/temperature

-

Excessive smelling/touching of objects

-

Fascination with lights and movement and being overwhelmed with loud noises

The truth is, while many children with autism have normal intelligence levels, many others have mild or significant intellectual delays.

This is where the right educators play a huge role in teaching students with ASD.

How Do You Teach Students With Autism Spectrum?

The number of students with autism is on the rise. So a deep understanding of the strategies and social skills needed to handle a class of autistic children is extremely important.

Listed are some tried and true strategies that will ensure every autistic child receives the best education possible.

These strategies apply to both the classroom and home environments.

-

Structure or routine is the name of the game when it comes to autism. Maintain the same daily routine, only making exceptions for special occasions. During such moments, place a distinct picture that depicts the day’s events in the child's personal planner.

-

Design an environment free of stimulating factors:

a. Avoid playing loud background music as it makes it difficult for the autistic child to concentrate.

b. Eliminate stress because autistic children quickly pick up on negative emotions. So for example, if you’re experiencing too much stress, leave the classroom until you feel better.

c. Maintain a low and clear voice when engaging the class. Students with autism get easily agitated and confused if a speaking voice is too loud.

d. Some autistic people find fluorescent lights distracting because they can see the flicker of the 60-cycle electricity. To mitigate this effect:

-

Place the child's desk near the window or try to avoid using fluorescent lights altogether.

-

If the lights are unavoidable, use the newest bulbs you have as they flicker less.

-

You can also place a lamp with an old-fashioned incandescent light bulb next to the child's desk.

e. Let students stand instead of sitting around a table for a class demonstration or during morning and evening meetings. Many students with autism tend to rock back and forth so standing allows them to repeat those movements while still listening to the teacher.

-

-

Keep verbal instructions short and to the point, because an autistic student may find it difficult to recall the entire sequence. Instead, write the instructions down on a piece of paper.

This seemingly small act matters; take this person with autism for instance:

“I am unable to remember sequences. If I ask for directions at a gas station, I can only remember three steps. Directions with more than three steps have to be written down.”

-

Go for repetitive motions when working on projects. For example, most autistic classrooms have an area for workbox tasks, such as putting away erasers and pencils. This kind of predictability helps autistic kids stay organized.

-

Use signs, pictures, and demonstrations for visual learners. For example:

a. When teaching up and down movements, attach cards with the words "up" and "down" to a toy airplane. The "up" card is attached when the plane takes off while the "down" card is attached when it lands.

b. Use a wooden apple cut up into four pieces and a wooden pear cut in half to help students with autism understand the concept of quarters and halves.

“I think in pictures. I do not think in language. All my thoughts are like videotapes running in my imagination. Pictures are my first language.”

-

Many autistic children hyperfocus on one subject like trains or maps so use that specific interest to motivate school work. With a child who likes trains, for instance, calculate how long it takes for a train to go between New York and Washington. And there you have it, you’ve just solved a math problem.

-

The fewer the choices, the easier decision-making is for an autistic kid. For instance, if you ask a student to pick a color, limit them to three choices.

-

Create a few structured one-on-one interactions between students to promote their social skills. Take note that autistic children can’t accurately interpret body language and touch, so minimal physical contact is best.

-

Parents and caregivers are the true experts on their autistic children. Therefore, to fully support the child in and out of school, teachers should coordinate and share knowledge with them. For example, you can exchange notes on interventions that have worked at home and in school then integrate accordingly.

-

Lastly, we can’t forget you, dear teacher. Even when you’re doing everything right, teaching students with autism can still be tough, so building resilience is important.

Here are some statements you can recite on difficult days:

-

“Building a relationship with autistic children doesn’t happen overnight — it takes time, dedication, and patience.”

-

“Every mistake I make is valuable feedback for figuring out what works.”

-

“I won’t always get things right off the bat and, ultimately, autistic children are still children, who can be a handful even at the best of times.

”

” -

“Autistic children aren’t difficult on purpose. They’re simply doing the best they can with their worldview and available support.”

-

“Good teachers helped me to achieve success. I was able to overcome autism because I had good teachers. At age 2 1/2 I was placed in a structured nursery school with experienced teachers. Children with autism need to have a structured day and teachers who know how to be firm but gentle.”

Rise to the Challenge

Positive Action recognizes the value of each and every person. We help special needs students integrate into mainstream classrooms while equipping them with the essential skills and motivation to thrive.

Positive Action can help you assess your special education students’ needs and plan how to meet them with Individualized Education Plans.

“I am very grateful for these lessons. They fulfill a need that so many children are lacking in the educational process today. ” — Linda Davis, 2nd Grade Teacher, Davis Elementary

” — Linda Davis, 2nd Grade Teacher, Davis Elementary

If you want to see how Positive Action can increase educational success at your institution or organization contact us by phone, chat, or email or schedule a webinar with us below.

How to teach a non-speaking child with autism to repeat sounds and words?

06/16/16

Several strategies for the development of basic skills for oral speech in children with autism

Source: bcotb.com

Author: Katherine Ganem / Catherine Ganem

9000 9000 9000

one of The main symptoms of autism are a lack of age-appropriate speech and communication skills. When teaching children with autism to speak, one of the first and most important skills is vocal imitation. Echo or vocal imitation is a type of speech where the speaker repeats the words of another speaker. For example, when a child says "bye" after his mother says "bye". It is obvious why vocal imitation is so important: if a child can repeat other people's words, then this will facilitate further learning in requests, naming objects and answering questions.

It is obvious why vocal imitation is so important: if a child can repeat other people's words, then this will facilitate further learning in requests, naming objects and answering questions.

The first step in learning vocal imitation is choosing a reward that is valuable to the child. It can be an edible reward, favorite toys, or some kind of action (for example, tickling).

The child's existing repertoire should be assessed next. How often does the child make any sounds, babble? Can he spontaneously make different sounds, or does he repeat the same speech sounds over and over again? What sounds did the child make in the past? Write it all down ahead of time to help you determine a strategy or strategies for furthering your child's education.

One or more of the following strategies can then be selected:

1. Stimulus-Stimulus Combination

Purpose: To form a link or association of speech sounds with a strong reward so that speech sounds themselves become rewards in the future and something pleasant for the child.

Practice: Choose speech sounds that the child has already made in the past, or those sounds that are easiest to pronounce (“ba”, “mmm”, etc.). Extend the encouragement to the child and say the desired sound. If the child makes or tries to make a sound, immediately reward him. If there are no sounds, then give him encouragement after a pause of one second. Remember, your goal now is to form an association between the sound and the reward, so the child doesn't have to say anything at all. However, if the child does repeat the sound after you, then reward him much more than when there were no sounds.

Rewards: For this program, the best rewards are those that don't have to be constantly taken back from the child. For example, it could be small bites of a child's favorite treat, or pleasurable adult activities such as tickling. It is best to avoid rewards that will have to be taken back (such as toys) unless the child has other types of rewards. Some children may become frustrated if a toy is taken away from them every five seconds.

Some children may become frustrated if a toy is taken away from them every five seconds.

Note: It usually takes hundreds of trials for a child to successfully imitate the sound of speech in this program. Gather data on what sounds your child is making to determine what sound should be the next target. Subsequently, from training in the "stimulus-stimulus" program, you can move on to training in requests. (See also How to Teach Your Child to Speak.)

2. Vocal play

Purpose: To combine or create an association between speech sounds and fun activities that the child prefers.

Practice: Start playing with your child or doing something he or she usually enjoys. While playing, as often as possible, make simple sounds and vocalizations that are usually associated with such a game (for example, "Beep-beep!", "Bang!"). If the child spontaneously repeats the sound after you or starts babbling, immediately praise him as much as possible and encourage him. However, do not ask or demand that the child say something.

However, do not ask or demand that the child say something.

Over time, the child will begin to associate funny sounds with play and will be more likely to imitate these sounds in the future.

Reward: Any game or favorite activity of the child. You can keep an extra reward (such as your child's favorite treat) handy just in case, to reward any spontaneous speech sounds.

Note: In this program, it is useful to set a timer for a certain time and count how many speech sounds the child makes so that you can track his progress.

3. Teaching requests with gestures simultaneously with words (total communication method)

Purpose: To create an association between speech sounds or words and specific rewards during teaching gesture requests.

Practice: When teaching gesture requests, always say the name of the item during each teaching step. If the child has already learned to ask with a gesture, then name the reward when you give it to the child. If the child is learning a new gesture, name the reward when prompting the child for the sign and then give the reward. Over time, the child will learn to associate the word with the reward, and this will increase the likelihood of word attempts and spontaneous verbal requests. (See also How to teach your child to ask with gestures.)

Reward: An item that the child asks for with a gesture.

4. Reward all sounds

Purpose: Reward all the sounds your child makes so that he is more likely to repeat them in the future.

Practice: Give your child encouragement and praise (Example: "Good job saying 'a'!") every time he or she makes a speech sound. This should be done throughout the day.

Reward: It is best to choose several rewards from different categories (eg different types of products, different activities, different toys). Otherwise, the child will quickly get fed up with the reward.

When the child can already imitate (or tries to imitate) basic speech sounds, other procedures can be used to form articulation and pronunciation of words. (Also see Vocal Imitation Teaching Technique and How to Help Your Child with Autism Speak More Clearly.)

Finally, some children learn different vocalizations faster than others. Babies who babble a lot are much faster at making different sounds than babies who don't babble. (See also "What does babbling mean in a non-speaking person with autism").

See also:

How to teach communication to a non-verbal child?

It's time to explore non-verbal autism not only in words

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

ABA Therapy and Behavior, Parenting with Autism, Communication and Speech

How to Toilet Train a Child with Autism

Toilet training a child with autism may require special approaches. We will tell about them.

We will tell about them.

The publication was prepared based on the results of a lecture by Lynn Farley, an autism specialist from the USA, who took part in the III International Scientific and Practical Conference "Autism: Support or Growing Together", held in Minsk.

Before embarking on toilet training, it is important to understand why toileting can be difficult for children with autism.

- Toilet training difficulties can be really difficult for children with ASD and may require more time and patience what is usually taught to normotypical children

- Every child with ASD is different

- Physiological (or medical) difficulties: these should be discussed with a doctor familiar with the child's history

- Language difficulties: difficulties understanding and using language when the child cannot ask to use the toilet

- Difficulties with dressing: problems with motor planning/certain movements (taking off/putting on pants)

- Fears: the child is afraid to sit on the toilet, afraid of the sound of running water and other similar reasons

- Body cues: The child with ASD may not be aware that he needs to go to the toilet, and may not feel that he has peed or pooped on.

any change in habits is difficult for him

any change in habits is difficult for him - Using different toilets: going to a different toilet is a change of routine for a child with ASD and is stressful for him

Study by Dalrymple and Ruble at 1992 found that, on average, children with ASD take 1.6 years of toilet training to stay dry throughout the day, and sometimes more than 2 years to achieve bowel control.

BABY TOILET READINESS

Before toilet training, it is important to identify signs that a child may be ready to be taught. Signs of toilet readiness (18 months to 3 years):

- Reports discomfort when peeing or pooping

- Reports when he wants to be changed

- Defecates regularly for a long period of time

- Can sit upright on the toilet for several minutes

- Regularly stays dry for more than 2 hours

- Tries to take off his pants and pull off his diaper

- Observes others and tries to imitate their actions in the toilet

- 1 Can follow simple one-step instructions

- Asks to go to the toilet before peeing or pooping

- Feeds in diaper at regular intervals

WHERE TO START TOILET TRAINING?

Start when your child shows signs of readiness. The child seems interested and wants to use the toilet on his water. Scheduled learning helps children learn skills faster and focus on a single task. Adults create a toilet schedule and help the child train his body to follow the schedule.

The child seems interested and wants to use the toilet on his water. Scheduled learning helps children learn skills faster and focus on a single task. Adults create a toilet schedule and help the child train his body to follow the schedule.

Don't ask your child if he needs to go to the toilet!

- Don't wait for your child to tell them they need to go to the bathroom

- Tell them it's time for a fun trip to the bathroom

- Make going to the bathroom fun

Schedule

- Fit toilet trips into your child's regular schedule ( 6 trips to the toilet per day)

- Avoid stressful periods when the child has other tasks

- Stick to the same schedule every day at home and outside the home

Communication

- Use simple words to communicate about the toilet

- Teach your child the “language of the toilet”: use the same words, signs and pictures every time

- Speak calmly, patiently and friendly

- who work with your child - educate them about your toilet training plan, ask them to stick to your schedule and toilet language

Decide on rewards/reinforcements

Praise your child for all his efforts, even the smallest ones. Make a list of your child's favorite things: food, toys, videos, etc. and decide what would be best for you to use as a reward (small portions of treats or time for a favorite activity after going to the toilet work well).

Make a list of your child's favorite things: food, toys, videos, etc. and decide what would be best for you to use as a reward (small portions of treats or time for a favorite activity after going to the toilet work well).

Schedule in pictures

Pictures can tell a child what to expect when going to the toilet. Take pictures of your toilet (toilet, toilet paper, sink, etc.). Glue the pictures on a sheet of paper in order, you can also use the objects directly if the pictures do not work.

Toilet training plans should include information about tasks, routines, language of communication with the child, setting, support materials, and reward options.

Tasks

Inform other adults involved with your child of their tasks. Explain to them what you are trying to achieve and provide a timetable. Example: "Tommy must go to the toilet 15 minutes after each meal and sit on the toilet for 10 seconds."

Daily routine

Includes: How often? What time? How long does a child stay in the toilet? Example: "Tommy has to go to the toilet every hour and sit on the toilet for 10 seconds. "

"

Language

Use words that your child understands. Example: "Tommy, it's time to write."

Location

Where: Where does your child go to the bathroom?

What: What can be changed in the environment to make your child more comfortable? (lighting (bright or dim), sounds (ventilation, light bulb buzzing, drain sounds, etc.), toilet paper (soft, hard, its color), doors (open or closed).

Who: Does your child want to be accompanied to the bathroom? (Adult to stay with child in the toilet or just nearby)

Resource Materials

Share with other adults the tools and hacks you use: picture schedule, special toy or song, listening to music while the child sits on the toilet.

Reward

List which actions/behaviors of the child are rewarded and which are not. Determine how to provide rewards for desired behaviors and what to do if the child does not deserve the reward. Example: “Johnny gets a sticker for 10 seconds of sitting on the toilet.