How to teach a nonverbal child

Teaching nonverbal autistic children to talk

March 19, 2013

Still among our most popular advice posts, the following article was co-authored by Autism Speaks's first chief science officer, Geri Dawson, who is now director of the Duke University Center for Autism and Brain Development; and clinical psychologist Lauren Elder.

Researchers published the hopeful findings that, even after age 4, many nonverbal children with autism eventually develop language.

For good reason, families, teachers and others want to know how they can promote language development in nonverbal children or teenagers with autism. The good news is that research has produced a number of effective strategies.

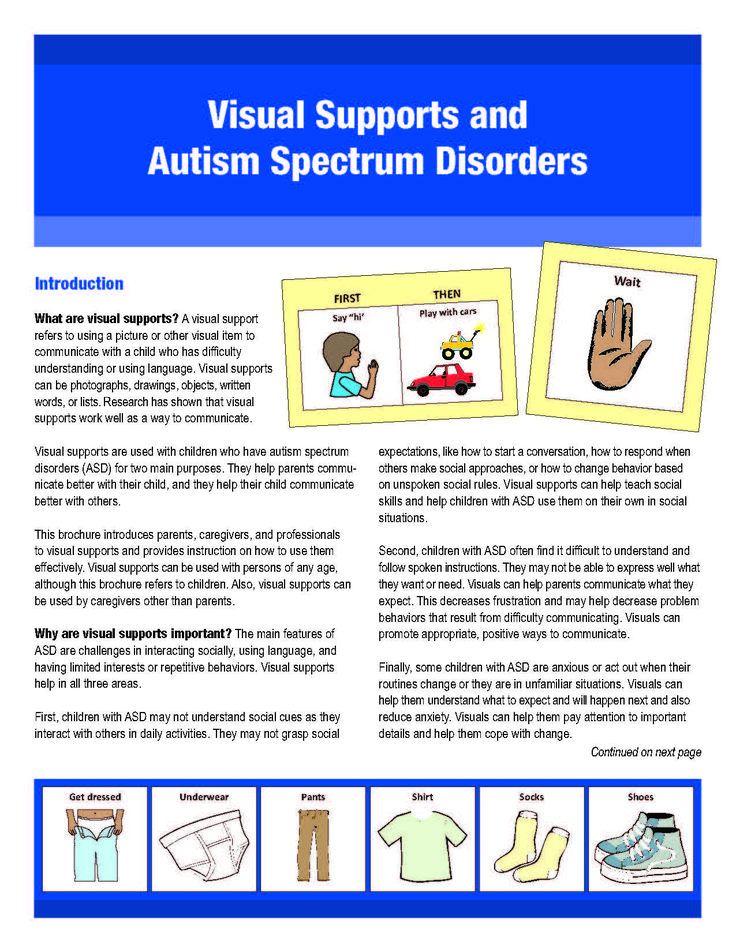

But before we share our “top tips,” it’s important to remember that each person with autism is unique. Even with tremendous effort, a strategy that works well with one child or teenager may not work with another. And even though every person with autism can learn to communicate, it’s not always through spoken language. Nonverbal individuals with autism have much to contribute to society and can live fulfilling lives with the help of visual supports and assistive technologies.

Here are our top seven strategies for promoting language development in nonverbal children and adolescents with autism:

- Encourage play and social interaction. Children learn through play, and that includes learning language. Interactive play provides enjoyable opportunities for you and your child to communicate. Try a variety of games to find those your child enjoys. Also try playful activities that promote social interaction. Examples include singing, reciting nursery rhymes and gentle roughhousing. During your interactions, position yourself in front of your child and close to eye level – so it’s easier for your child to see and hear you.

- Imitate your child. Mimicking your child’s sounds and play behaviors will encourage more vocalizing and interaction.

It also encourages your child to copy you and take turns. Make sure you imitate how your child is playing – so long as it’s a positive behavior. For example, when your child rolls a car, you roll a car. If he or she crashes the car, you crash yours too. But don’t imitate throwing the car!

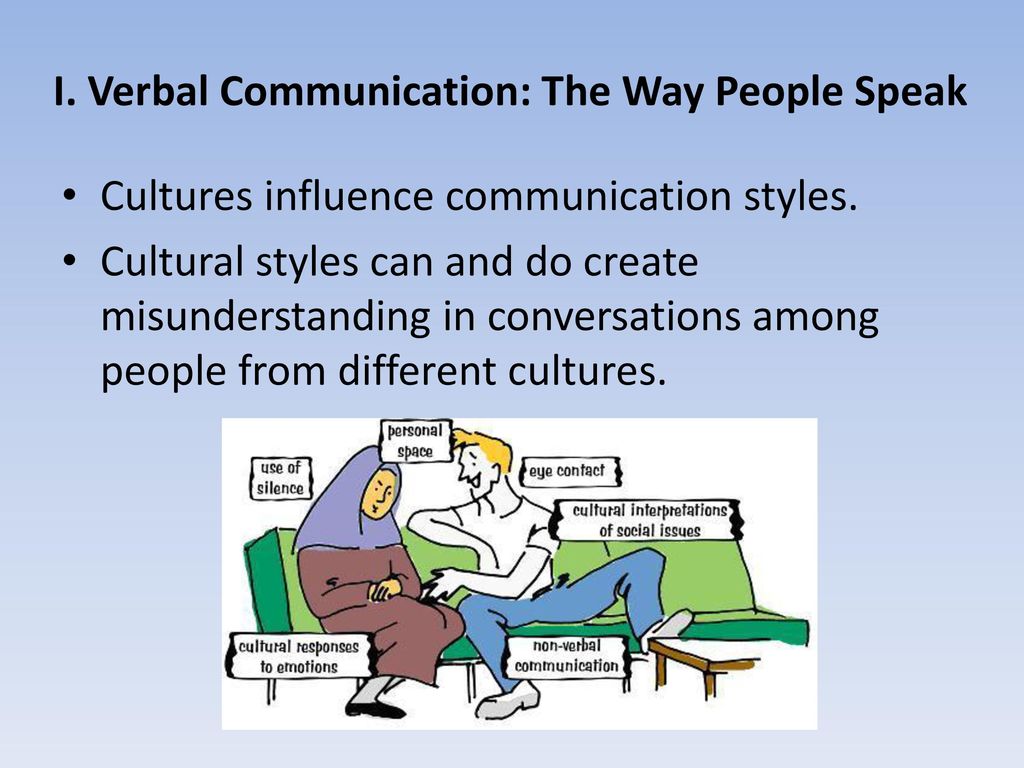

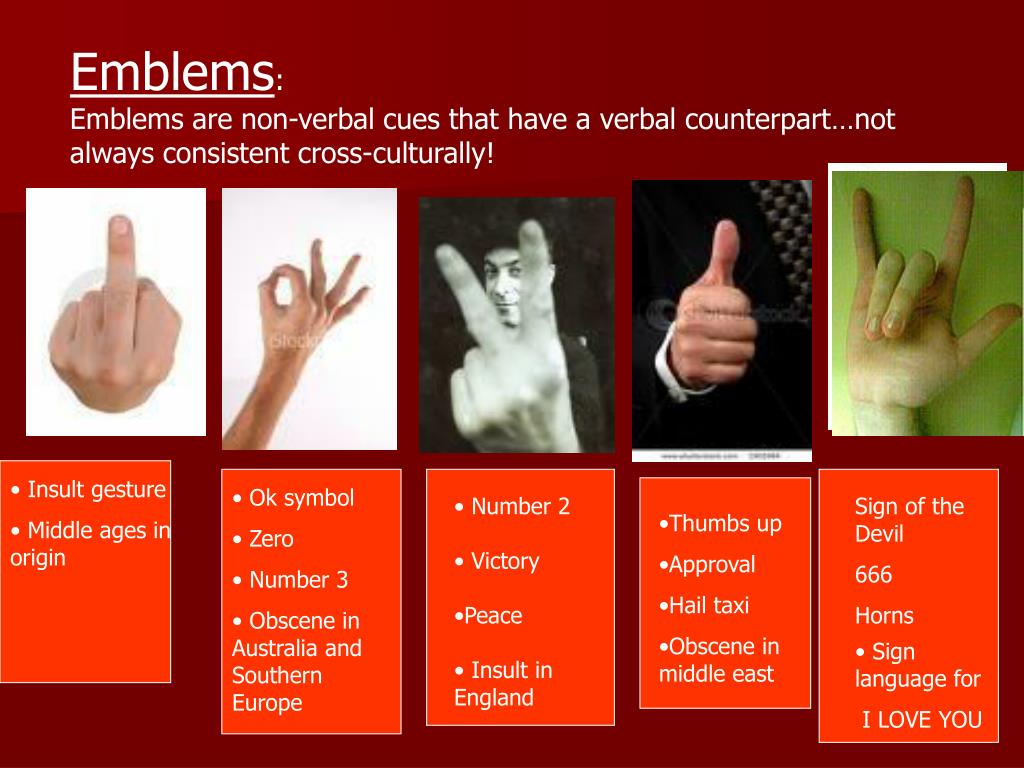

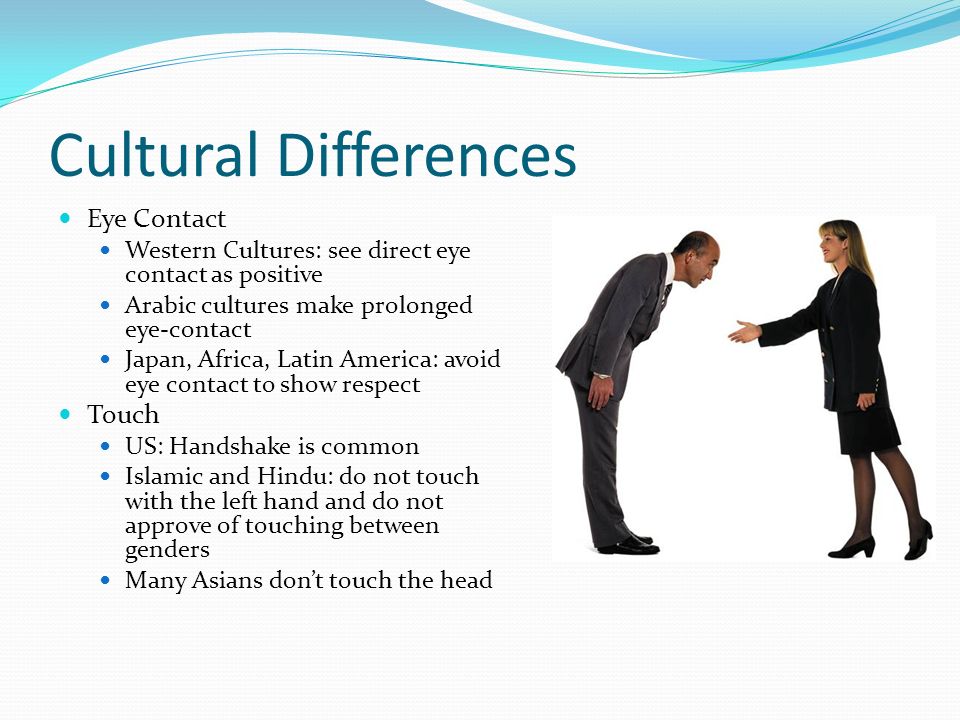

It also encourages your child to copy you and take turns. Make sure you imitate how your child is playing – so long as it’s a positive behavior. For example, when your child rolls a car, you roll a car. If he or she crashes the car, you crash yours too. But don’t imitate throwing the car! - Focus on nonverbal communication. Gestures and eye contact can build a foundation for language. Encourage your child by modeling and responding these behaviors. Exaggerate your gestures. Use both your body and your voice when communicating – for example, by extending your hand to point when you say “look” and nodding your head when you say “yes.” Use gestures that are easy for your child to imitate. Examples include clapping, opening hands, reaching out arms, etc. Respond to your child’s gestures: When she looks at or points to a toy, hand it to her or take the cue for you to play with it. Similarly, point to a toy you want before picking it up.

- Leave “space” for your child to talk.

It’s natural to feel the urge to fill in language when a child doesn’t immediately respond. But it’s so important to give your child lots of opportunities to communicate, even if he isn’t talking. When you ask a question or see that your child wants something, pause for several seconds while looking at him expectantly. Watch for any sound or body movement and respond promptly. The promptness of your response helps your child feel the power of communication.

It’s natural to feel the urge to fill in language when a child doesn’t immediately respond. But it’s so important to give your child lots of opportunities to communicate, even if he isn’t talking. When you ask a question or see that your child wants something, pause for several seconds while looking at him expectantly. Watch for any sound or body movement and respond promptly. The promptness of your response helps your child feel the power of communication. - Simplify your language. Doing so helps your child follow what you’re saying. It also makes it easier for her to imitate your speech. If your child is nonverbal, try speaking mostly in single words. (If she’s playing with a ball, you say “ball” or “roll.”) If your child is speaking single words, up the ante. Speak in short phrases, such as “roll ball” or “throw ball.” Keep following this “one-up” rule: Generally use phrases with one more word than your child is using.

- Follow your child’s interests.

Rather than interrupting your child’s focus, follow along with words. Using the one-up rule, narrate what your child is doing. If he’s playing with a shape sorter, you might say the word “in” when he puts a shape in its slot. You might say “shape” when he holds up the shape and “dump shapes” when he dumps them out to start over. By talking about what engages your child, you’ll help him learn the associated vocabulary.

Rather than interrupting your child’s focus, follow along with words. Using the one-up rule, narrate what your child is doing. If he’s playing with a shape sorter, you might say the word “in” when he puts a shape in its slot. You might say “shape” when he holds up the shape and “dump shapes” when he dumps them out to start over. By talking about what engages your child, you’ll help him learn the associated vocabulary. - Consider assistive devices and visual supports. Assistive technologies and visual supports can do more than take the place of speech. They can foster its development. Examples include devices and apps with pictures that your child touches to produce words. On a simpler level, visual supports can include pictures and groups of pictures that your child can use to indicate requests and thoughts. For more guidance on using visual supports, see Autism Speaks ATN/AIR-P Visual Supports Tool Kit.

Your child’s therapists are uniquely qualified to help you select and use these and other strategies for encouraging language development. Tell the therapist about your successes as well as any difficulties you’re having. By working with your child’s intervention team, you can help provide the support your child needs to find his or her unique “voice.”

Tell the therapist about your successes as well as any difficulties you’re having. By working with your child’s intervention team, you can help provide the support your child needs to find his or her unique “voice.”

Blog

Expert Q&A: Tips for an active and healthy lifestyle

Blog

How to make the holidays more meaningful for yourself and your autistic loved ones

Blog

Giving Thanks: Autistic adult credits his family, friends and therapy for his good life

Expert Opinion

Tips for creating an autism-friendly Thanksgiving

Blog

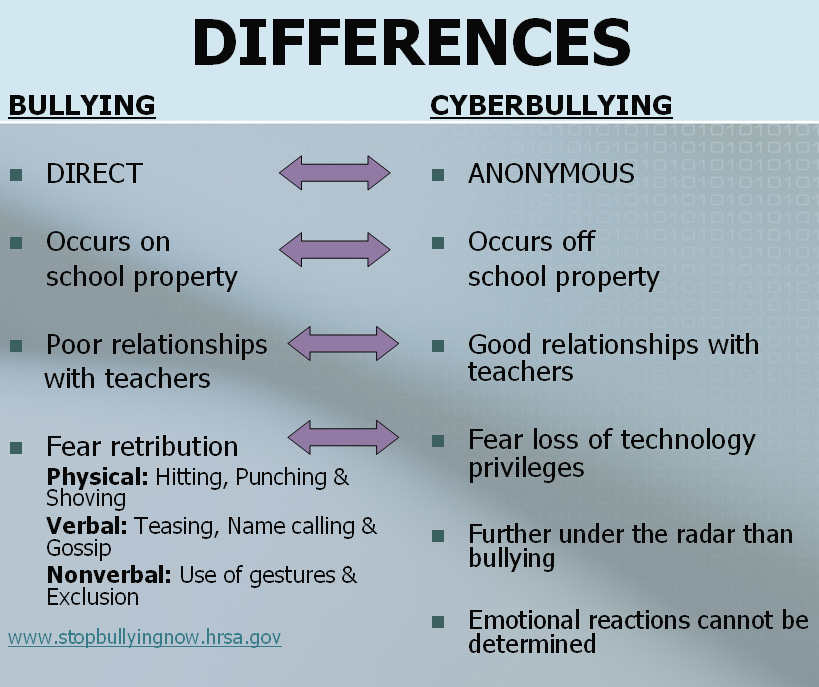

In Our Own Words: Embracing empathy and individuality to overcome bullying

Blog

Expert Q&A: Dr. Ryan Adams shares tips and resources to end bullying

Ryan Adams shares tips and resources to end bullying

Blog

Catching up with Kaitlyn Y.

Blog

Expert Q&A: Supporting siblings of autistic children with aggressive behaviors

Teaching Children with Nonverbal Autism to Read

This week’s “Got Questions?” response is by psychologist Charlotte DiStefano, an Autism Speaks Meixner Postdoctoral Fellow in Translational Science, at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. DiStefano’s Autism Speak Meixner Fellowship in Translational Research involves identifying brain activity patterns that relate to language and literacy abilities in minimally verbal children with autism. The hope is to guide the development of individualized therapy and educational programs that best address each child’s needs.

“Any suggestions for teaching a nonverbal 8-year-old to read? He can form sentences using augmentative communication.”I’m so glad you’ve asked this question. Many people wrongly assume that children who don’t speak can’t learn to read. But that’s definitely not true!

Many people wrongly assume that children who don’t speak can’t learn to read. But that’s definitely not true!

Two years ago, I published the results of a small study on the effectiveness of a reading program adapted for minimally verbal 5 and 6 year olds. All the students showed increased story comprehension and engagement. Unfortunately we have little other research on reading ability – or literacy – among minimally verbal kids with autism. As a result, we really don’t know how many nonverbal or minimally verbal children with autism can read or have the ability to learn how to read.

But many parents and professionals can tell you of children who can read despite not using spoken language. So we know it’s possible. What I find especially amazing is that many of these children seem to figure out how to read on their own – because no one ever gave them direct literacy instruction.

I’ve worked with several minimally verbal and non-verbal kids who showed me that they could read. They did so in various ways: matching words and sentences to pictures, typing words and/or following written text with a finger as an adult reads a book.

They did so in various ways: matching words and sentences to pictures, typing words and/or following written text with a finger as an adult reads a book.

One of the major challenges to teaching reading to minimally verbal kids is that traditional literacy instruction relies heavily on spoken language. As you’ll probably recall from your own first grade experience, learning to read usually involves a big focus on phonics: Teachers have children enunciate the sounds of letters. Then the children learn how these sounds combine to form words.

For kids who use no or minimal spoken language, this obviously presents some difficulty. How can a child learn to “sound out” words when he or she has difficulty making sounds?

Fortunately there are many ways to teach reading that don’t depend on a child using spoken language.

1. First and foremost, I recommend spending lots of time reading with your child!First and foremost, I recommend spending lots of time reading with your child! We know that reading with children encourages their development of language and reading. One of the most beneficial aspects of shared reading is the dialogue between the adult and child, as they discuss the book that they are reading.

One of the most beneficial aspects of shared reading is the dialogue between the adult and child, as they discuss the book that they are reading.

Although minimally verbal kids won’t be able to have a verbal conversation about the book, they can very much engage non-verbally with the book and the reader.

2. Nonverbal interactive reading

As you read with your child, give him opportunities to interact nonverbally. Here are some activities you can share as you read:

* Run your finger just under the text as you read. Then ask your child do the pointing.

* Ask your child to turn the pages at the right time.

* Give your child some story props so he can act out the story as it unfolds.

* Take turns imitating what the characters are doing.

These and similar activities will help your child engage with a book without relying on spoken language.

3. Discuss stories using assisted communicationIt’s great to hear that your child uses an augmentative and assistive communication (AAC) device. The device can provide your child with added opportunities to interact with you and the book you’re reading together. Before reading a new book, make sure that the system has a good array of symbols related to the story. For example, if you’re reading a book about a birthday party, make sure you have downloaded symbols for, say, “party,” “presents,” “cake” and “balloons.” As you read a story or book, use the symbols to discuss the characters and actions.

The device can provide your child with added opportunities to interact with you and the book you’re reading together. Before reading a new book, make sure that the system has a good array of symbols related to the story. For example, if you’re reading a book about a birthday party, make sure you have downloaded symbols for, say, “party,” “presents,” “cake” and “balloons.” As you read a story or book, use the symbols to discuss the characters and actions.

The AAC system itself offers great opportunities for developing literacy. Make sure that the device is set to display the words that go with each picture symbol. This will help your child associate written words with objects and actions.

As your child becomes more familiar with the printed words, I suggest gradually reducing the size of the accompanying pictures while increasing the size of the text. Once he’s comfortably recognizing the text, you may be able to remove the pictures entirely!

4. Reading and writing with speech-generating devicesThe typing function on speech-generating devices is another wonderful avenue for developing literacy. I’ve worked with minimally verbal children who, after watching me program new words into their device, suddenly start choosing their own symbols and typing in what they want to say!

I’ve worked with minimally verbal children who, after watching me program new words into their device, suddenly start choosing their own symbols and typing in what they want to say!

Since we didn’t know these kids could read, we were certainly surprised! And once they figured out that they could type in words of their choosing, they became much more independent communicators.

Though your child may not yet be able to type and spell words, let him watch as you program new words into the device. Explain what you’re doing. You never know when he’ll surprise you and start typing the words he wants to say.

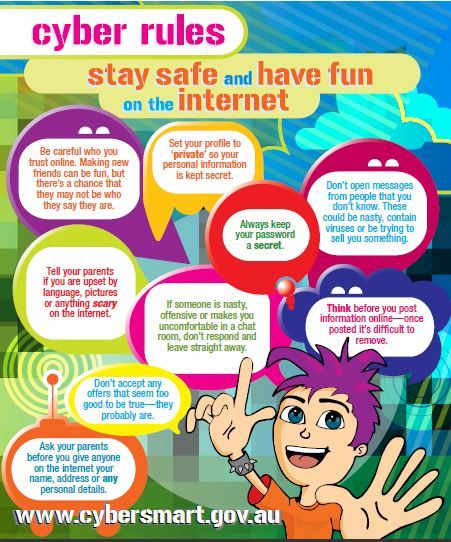

5. Practice literacy when you’re out and aboutI also encourage you to read signs with your child – especially safety-related signage. This can become a natural part of your day when you walk and drive through your community. Reading a stop sign is an important example. The same goes for the street sign or signs that will help your child identify the block where you live. Then there are crosswalk signs, exit and entrance signs. You get the idea.

Then there are crosswalk signs, exit and entrance signs. You get the idea.

To summarize, we can all support literacy development in minimally verbal and non-verbal kids with autism by

* reading together

* giving them opportunities to interact with a story or other written information in whatever way they’re able

* teaching them to recognize words paired with pictures or symbols

* showing them how we set up symbols in their AAC devices and

* giving them opportunities to type their own words when they’re ready

* reading signage – especially safety signage – when out in the community

I want to thank you again for your question. I hope these tips prove helpful for you, your son and many other readers. Please let us know how you’re doing in the comment section below or by emailing us again at [email protected].

How to teach communication to a non-verbal child?

12. 10.14

10.14

Description of the main and most effective approaches to the development of speech in non -verbal children with autism

Translation: Yana Shalimova

Source: I Love Aba

9000 9000

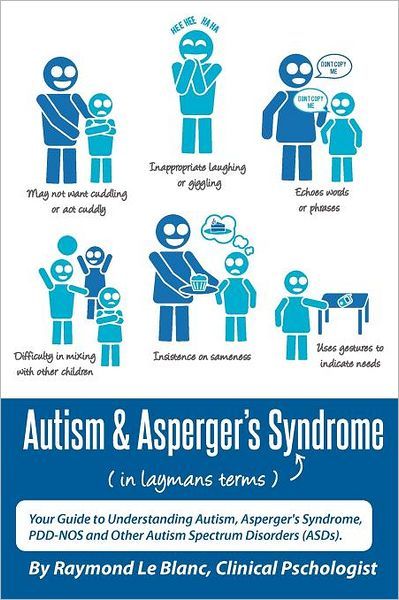

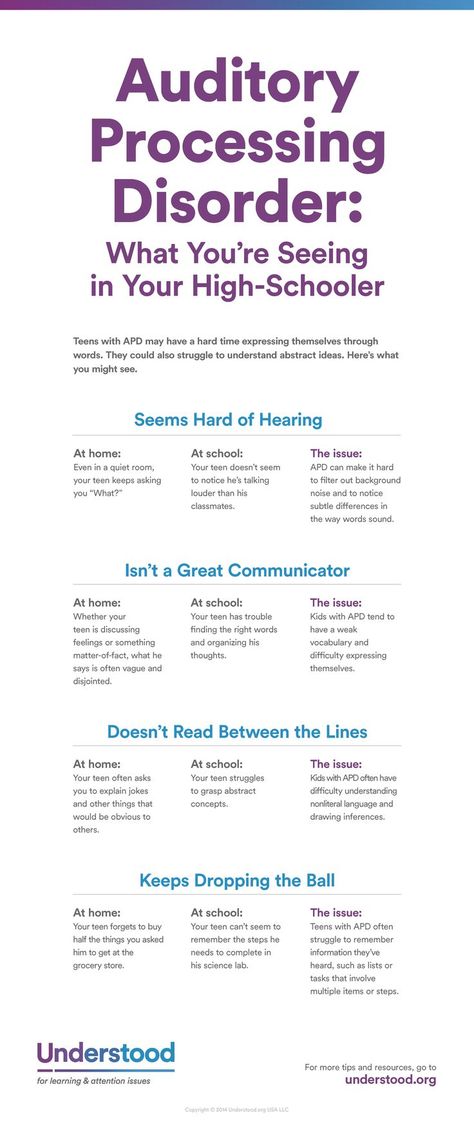

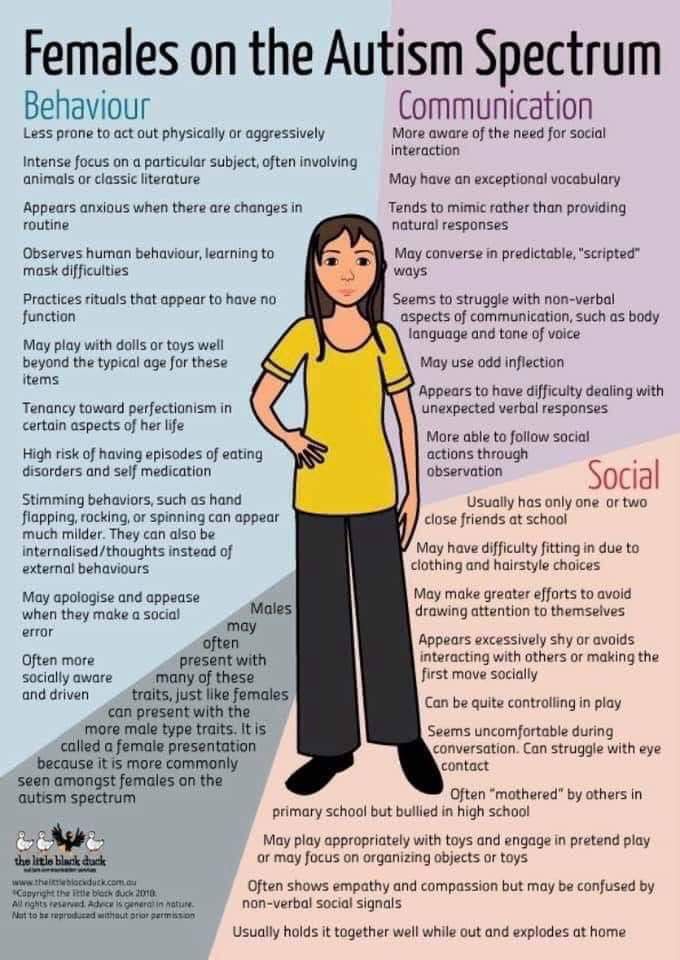

Quite often children with children. with autism, they do not speak at all, or their speech develops with a long delay. Sometimes this is due to medical problems such as tongue problems or apraxia. However, much more often this is due to impairments in the areas of motivation and social interaction. Speech delays can also be caused by advanced ear infections, which can lead to hearing loss and hamper speech development at a critical time.

The term "non-verbal" refers to a person who does not use voice to communicate (the clinical term is "non-vocal" because verbal behavior may include communication without sounds, such as sign language). In most cases, instead of language, these children use ineffective or inappropriate ways of communicating. Most of the guys I worked with were non-verbal when we met. Typically, these children communicated by pointing fingers, guiding me to the right place, or (most often) expressing their needs through behavior. In my practice, I have observed several babies who, without saying a word, could get everything they wanted. Parents understood that two shouts meant “turn on the TV”, crying meant “take me in your arms”, and pushing away a brother or sister meant “I don’t want to play”, etc.

Most of the guys I worked with were non-verbal when we met. Typically, these children communicated by pointing fingers, guiding me to the right place, or (most often) expressing their needs through behavior. In my practice, I have observed several babies who, without saying a word, could get everything they wanted. Parents understood that two shouts meant “turn on the TV”, crying meant “take me in your arms”, and pushing away a brother or sister meant “I don’t want to play”, etc.

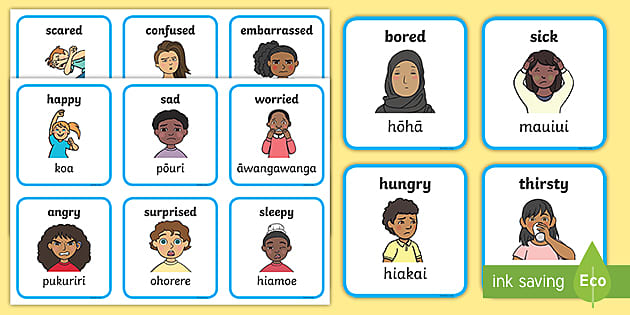

When working with non-verbal children, your goal is not to get the child to speak. The main task is to teach the child effective communication . Even verbal children are not always capable of communication. If I teach a five-year-old child to name colors and body parts, but he is not able to tell me that he wants to eat, then this is an example of a child who can speak, but does not use speech to communicate.

It is important to realize that "non-verbal" is not just someone who cannot speak. How does the child communicate? Do you get the impression that he understands a lot more by ear than he can say? Does the child hum to himself, name parts of words, sing songs or melodies? Does the child scream when upset or make mute sounds? I can say from my experience that if a non-verbal child has vocal stereotypes or echolalia (repetition of other people's words and phrases), then this increases the likelihood that he will become verbal. A child who echoes words, sings, or babbles is more likely to be able to speak.

How does the child communicate? Do you get the impression that he understands a lot more by ear than he can say? Does the child hum to himself, name parts of words, sing songs or melodies? Does the child scream when upset or make mute sounds? I can say from my experience that if a non-verbal child has vocal stereotypes or echolalia (repetition of other people's words and phrases), then this increases the likelihood that he will become verbal. A child who echoes words, sings, or babbles is more likely to be able to speak.

Behavior work plays a huge role in the development of communication. This has to be repeated over and over again: non-verbal or non-communicative children are characterized by the most problematic and difficult to correct types of behavior. Why is it so? Try to imagine that you are in a society where no one speaks your language. If you speak English, then everyone around you speaks French. If you speak Arabic, then everyone around you speaks German. Now imagine that you are hungry, and you need to somehow convince these people to feed you. And how long can you point and gesticulate before you start pushing people and throwing things?

And how long can you point and gesticulate before you start pushing people and throwing things?

If a child lacks an innate motivation for social interaction, and the people around him do not additionally motivate him for this, then it will be much easier for him to get his own way with the help of unwanted behavior. A child who is allowed to throw a plate on the floor at the end of a meal, which means "I ate", has no reason to think about how to put it into words, how to pronounce it and communicate to others.

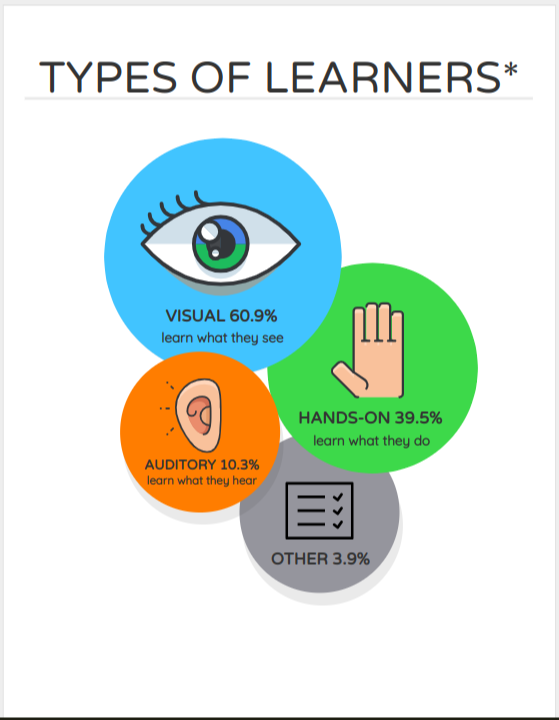

Encouragement for communication plays a huge role. When a child with autism learns to communicate with other people, you should always have at hand the rewards he desires. You might be thinking, “Why should I encourage my child to speak? Because my older kids just started talking and didn't get M&M's for it." A key feature of autism is qualitative impairments in the field of communication. This may mean that the child does not speak at all, has speech delays, or has a command of the language but no motivation to use it.

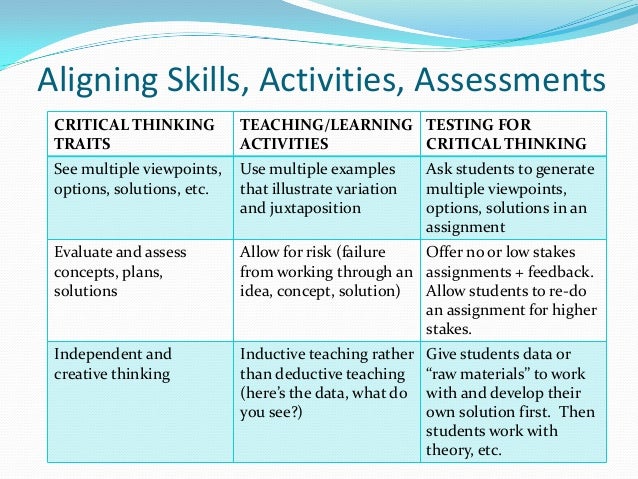

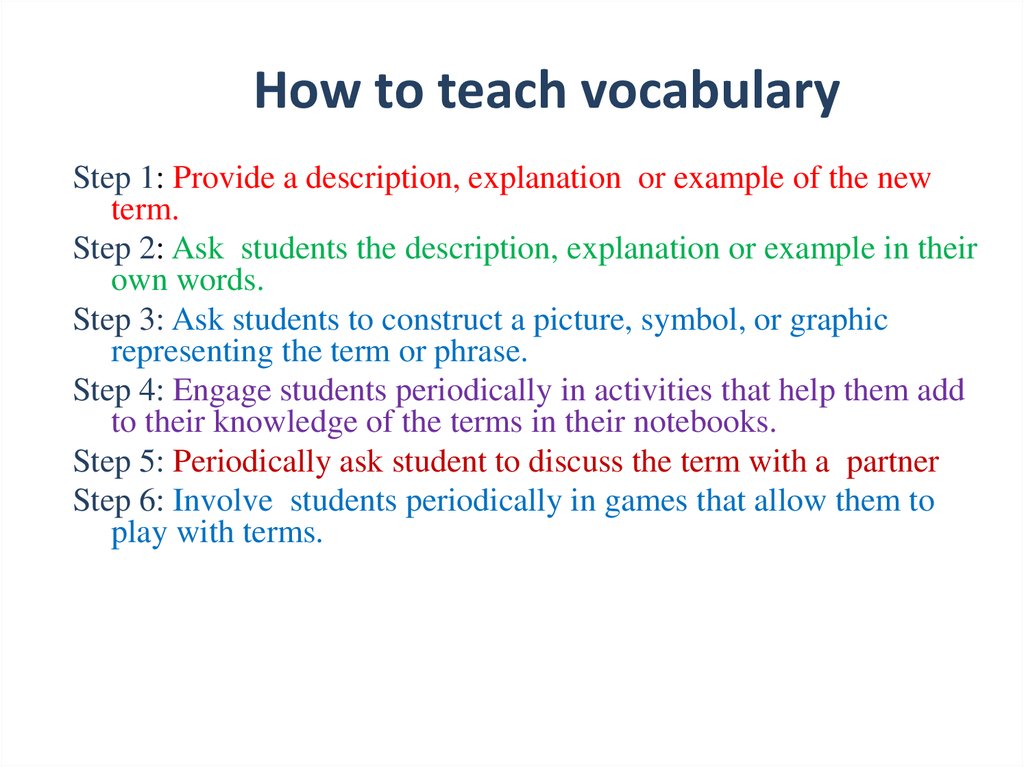

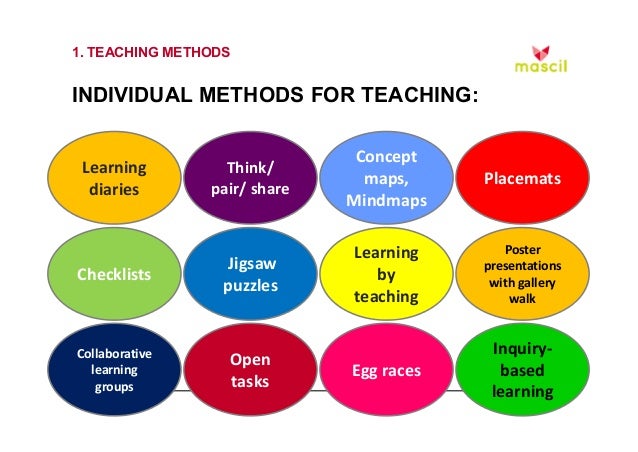

There are several approaches to teaching non-verbal children to communicate (and behavioral analysts/counselors often advise using several methods at once):

Methods of teaching communication

Verbal behavioral approach (ABA) There are many directions in the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA) , and the verbal behavioral approach is one of them. This method focuses on the development of functional speech. The starting point in this approach is the internal motivation of the child, who receives rewards to reinforce various types of communication (requests, naming, and so on). In this approach, language is taught just like any other behavior, and each component of speech is divided into small steps. For example, if a child loves ice cream very much, then the first thing they are taught is to pronounce the word "ice cream". Thus, the child's desire to get what he wants is used to stimulate his speech. You say ice cream, you get ice cream. The verbal behavioral approach also uses repetition, prompting, and the gradual formation of the desired response. If a child is taught to ask for a ball, then "ma" is accepted as a request first. Over time, with careful data collection and analysis, the criteria become more stringent until the child can clearly say "ball".

The verbal behavioral approach also uses repetition, prompting, and the gradual formation of the desired response. If a child is taught to ask for a ball, then "ma" is accepted as a request first. Over time, with careful data collection and analysis, the criteria become more stringent until the child can clearly say "ball".

Speech therapy. Of the ten clients I work with, 6-7 usually also visit a speech therapist. Many parents believe that speech therapy is the only way to help a non-verbal child speak. Speech therapists work with problems such as stuttering, articulation disorders, eating/swallowing difficulties, and the like. I know children who have made great strides with the help of a speech therapist, and I have worked with those who have not been affected by these services. They received speech therapy for years, and began to speak after a few months of ABA therapy. As a client, it is important for you to find a speech therapist who has knowledge and experience specifically in the field of autism or behavioral therapy. It is also important to pay attention to the intensity of training. Many of the children I work with only have an hour and a half a week with a speech therapist. For a non-verbal, low-functioning autistic child, such therapy is not enough to make any meaningful changes.

It is also important to pay attention to the intensity of training. Many of the children I work with only have an hour and a half a week with a speech therapist. For a non-verbal, low-functioning autistic child, such therapy is not enough to make any meaningful changes.

Sign language. When you name the surrounding objects, always accompany them with a gesture, so that when the child hears the word, he simultaneously learns the corresponding gesture. Considering sign language as a form of communication, one should always take into account the age of the child and his fine motor skills. If your child has fine motor skills and is unable to complete a sequence of complex gestures, sign language may not be the best option. Age is important because you need to consider the breadth of your child's social circle. If he's two years old and spends all day with his mom and dad, then sign language is probably fine. And if the child is 11 years old, he goes to school, an extended day group, and then to the karate section, then all the people with whom he communicates must understand his gestures. If a child walks up to a teacher on a school playground and gestures for a “red notebook,” will the teacher understand? In the event that children do not receive a prompt response to their gestures, they may simply stop using them. Another common mistake when teaching a child to sign language is getting stuck on the “more” gesture. Many specialists and parents teach the child the “more” gesture, and, unfortunately, he transfers this gesture to all situations. The child begins to approach everyone in a row and repeat the “more” gesture when others have no idea what he wants. "What more? Now imagine how upset a child is when he is not understood. If you decide to teach your child the “more” gesture, then be sure to teach him to use the gesture only in tandem with the name of what he wants.

If a child walks up to a teacher on a school playground and gestures for a “red notebook,” will the teacher understand? In the event that children do not receive a prompt response to their gestures, they may simply stop using them. Another common mistake when teaching a child to sign language is getting stuck on the “more” gesture. Many specialists and parents teach the child the “more” gesture, and, unfortunately, he transfers this gesture to all situations. The child begins to approach everyone in a row and repeat the “more” gesture when others have no idea what he wants. "What more? Now imagine how upset a child is when he is not understood. If you decide to teach your child the “more” gesture, then be sure to teach him to use the gesture only in tandem with the name of what he wants.

Communication Picture Exchange System (PECS). With the help of the PECS system, the child learns to exchange photos of the objects he needs for the objects themselves. PECS images are easy to use, take with you, and can describe in detail everything in the child's environment. With PECS, you can teach your child to make a request in a whole sentence, ask for several things at once, tell how the day went, just talk, etc. The advantage of PECS over gestures is that pictures or photographs can be understood by anyone. If a child inaccurately shows a gesture, then no one will understand what he wants. With the PECS system, you can use pictures or real photos of the items, whichever suits your child best. Another advantage of PECS compared to gestures is that this system is suitable for communicating with peers. A typical three-year-old child might not understand the "play" gesture, but they will definitely understand that a card with a picture of a doll house means "Do you want to play with a doll house?" Disadvantages of this system that parents have reported to me include the difficulty of constantly adding different photos/pictures, and if the child's interests change quickly, then the cards have to be changed quickly as well.

With PECS, you can teach your child to make a request in a whole sentence, ask for several things at once, tell how the day went, just talk, etc. The advantage of PECS over gestures is that pictures or photographs can be understood by anyone. If a child inaccurately shows a gesture, then no one will understand what he wants. With the PECS system, you can use pictures or real photos of the items, whichever suits your child best. Another advantage of PECS compared to gestures is that this system is suitable for communicating with peers. A typical three-year-old child might not understand the "play" gesture, but they will definitely understand that a card with a picture of a doll house means "Do you want to play with a doll house?" Disadvantages of this system that parents have reported to me include the difficulty of constantly adding different photos/pictures, and if the child's interests change quickly, then the cards have to be changed quickly as well.

Auxiliary communication devices. Using an assistive communication device will allow the child to create speech using a voice synthesizer. The child inserts pictures, types or presses buttons, and the device reproduces the corresponding words using an artificial voice. Since this is a technological device, it is necessary that the child has sufficient intellectual ability to use it independently of adults. However, if you have an iPad, there are excellent communication apps (such as Proloquo 2 Go) that allow non-verbal children to communicate with just a few finger movements. The advantage of such technologies is that they are suitable for people with different physical abilities, as they can be modified and adapted for children who have low vision, cannot type, or are hard of hearing. These apps and devices are easy to take with you and allow your child to quickly communicate what they want, what they think, how they feel about things, and what they need. Some devices can be programmed on an as-needed basis, filling in specific information that cannot be matched with a photo (such as the long knock-knock joke).

Using an assistive communication device will allow the child to create speech using a voice synthesizer. The child inserts pictures, types or presses buttons, and the device reproduces the corresponding words using an artificial voice. Since this is a technological device, it is necessary that the child has sufficient intellectual ability to use it independently of adults. However, if you have an iPad, there are excellent communication apps (such as Proloquo 2 Go) that allow non-verbal children to communicate with just a few finger movements. The advantage of such technologies is that they are suitable for people with different physical abilities, as they can be modified and adapted for children who have low vision, cannot type, or are hard of hearing. These apps and devices are easy to take with you and allow your child to quickly communicate what they want, what they think, how they feel about things, and what they need. Some devices can be programmed on an as-needed basis, filling in specific information that cannot be matched with a photo (such as the long knock-knock joke). Other devices are more limited and difficult to program for extended conversations or dialogue.

Other devices are more limited and difficult to program for extended conversations or dialogue.

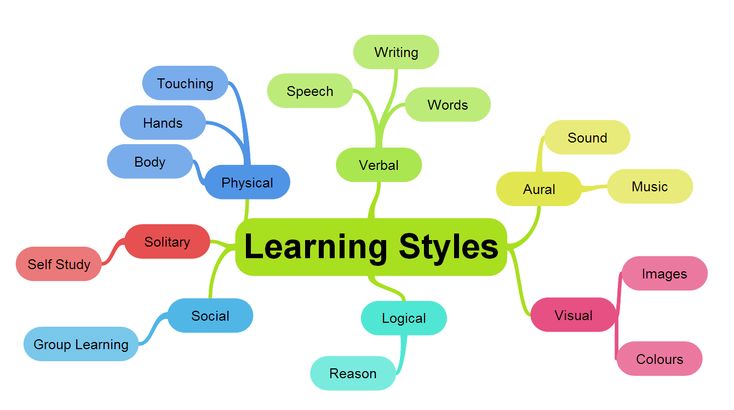

Language immersion. This method is commonly used in preschools or kindergartens that accept children with special needs. Throughout the day in the group, the child is immersed in an environment that motivates him to speak. Each item is clearly named and each child engages in conversation even if they cannot speak (“David, is my jacket blue? Nod if my jacket is blue”). Teachers work individually with each child, teaching him to play in turn, maintain eye contact and pay attention to the same thing as the other person. In my opinion, such classes are very similar to the Kegel method or training in basic reactions, one of the ABA approaches. The advantage of language immersion, as well as teaching basic communication skills, is that parents can easily use this method with their child. Such techniques focus on those stages of development that usually lead to the first words, such as babbling, distinguishing sounds, imitation, responding to oral instructions, and communicating through gestures. Individual work with a child includes natural communication and encouragement. For example, you can respond to a child's babble as if it were words and keep the conversation going. Describe your actions and what the child is doing, even if he does not answer you in any way ("We are going up the stairs. Let's count the steps: 1, 2, 3, 4 ..."). When you say this, keep eye contact, build on common interests with your child, and make learning fun.

Individual work with a child includes natural communication and encouragement. For example, you can respond to a child's babble as if it were words and keep the conversation going. Describe your actions and what the child is doing, even if he does not answer you in any way ("We are going up the stairs. Let's count the steps: 1, 2, 3, 4 ..."). When you say this, keep eye contact, build on common interests with your child, and make learning fun.

The sheer variety of programs, books, resources, and clinics that promise to teach autistic children to speak can be confusing for parents. Choose a program very responsibly and trust only those methods that have been researched and approved, as well as those that clearly and clearly describe how this method works and what it includes. If you need to pay for treatment or order a book to figure out how the method works, then this is a reason to be suspicious.

Whatever option you choose to teach your child to communicate will only be effective in different places and with different people if you provide support for the desired behavior. The child must learn that from now on, others will not accept anything other than his communication system. This means that if you taught a child to ask for cookies with a gesture, then he can no longer climb onto the kitchen table to get a jar of cookies from the refrigerator. Make communication with you a requirement, or the child will never communicate.

The child must learn that from now on, others will not accept anything other than his communication system. This means that if you taught a child to ask for cookies with a gesture, then he can no longer climb onto the kitchen table to get a jar of cookies from the refrigerator. Make communication with you a requirement, or the child will never communicate.

The child must also understand that communication with people leads to good results. If the child has just learned the request for "juice", then every time he says "juice", you need to give him some juice. The child must see that through communication you can quickly get what he needs or wants.

If you have started using a communication system for a child with autism, but the results are not satisfactory, then ask yourself the question: “Is this communication system the only way for the child to get what he wants/needs?” If not, then perhaps this is the reason for the lack of improvement.

** Important tip: It is very important for the learning and development of speech to start the intervention at the earliest stages. If you want to achieve the best results, then you need to start exercising with your child as early as possible. However, research shows that hope is not lost for older non-verbal children with autism. It will be more difficult for an older child to learn to speak, but, nevertheless, it is possible. The most effective methods for working with children over 5 years of age include the use of speech-generating devices (which do not suppress language) and developmental approaches that aim to develop divided attention.

If you want to achieve the best results, then you need to start exercising with your child as early as possible. However, research shows that hope is not lost for older non-verbal children with autism. It will be more difficult for an older child to learn to speak, but, nevertheless, it is possible. The most effective methods for working with children over 5 years of age include the use of speech-generating devices (which do not suppress language) and developmental approaches that aim to develop divided attention.

See also:

Autism and alternative communication: what I would like to know much earlier

Notes of an autist. Autism, speech and assistive technology

How to help a non-verbal child to speak?

How to teach a child with autism to make verbal requests?

How to teach a child to use words instead of tantrums?

Three Key Speech Development Strategies

How do you teach a child with autism to make a request with a gesture?

How to choose a communication method for a non-verbal child with autism?

What is divided attention and how can it be developed in children with autism?

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

ABA Therapy and Behavior, Communication and Speech

How to teach a non-speaking child with autism to repeat sounds and words?

06/16/16

Several strategies for the development of basic skills for oral speech in children with autism

Source: bcotb.com

Author: Katherine Ganem / Catherine Ganem

9000 9000 9000

one of The main symptoms of autism are a lack of age-appropriate speech and communication skills. When teaching children with autism to speak, one of the first and most important skills is vocal imitation. Echo or vocal imitation is a type of speech where the speaker repeats the words of another speaker. For example, when a child says "bye" after his mother says "bye". It is obvious why vocal imitation is so important: if a child can repeat other people's words, then this will facilitate further learning in requests, naming objects and answering questions.

The first step in learning vocal imitation is choosing a reward that is valuable to the child. It can be an edible reward, favorite toys, or some kind of action (for example, tickling).

The child's existing repertoire should be assessed next. How often does the child make any sounds, babble? Can he spontaneously make different sounds, or does he repeat the same speech sounds over and over again? What sounds did the child make in the past? Write it all down ahead of time to help you determine a strategy or strategies for furthering your child's education.

One or more of the following strategies can then be selected:

1. Stimulus-Stimulus Combination

Purpose: To form a link or association of speech sounds with a strong reward so that speech sounds themselves become rewards in the future and something pleasant for the child.

Practice: Choose speech sounds that the child has already made in the past, or those sounds that are easiest to pronounce (“ba”, “mmm”, etc. ). Extend the encouragement to the child and say the desired sound. If the child makes or tries to make a sound, immediately reward him. If there are no sounds, then give him encouragement after a pause of one second. Remember, your goal now is to form an association between the sound and the reward, so the child doesn't have to say anything at all. However, if the child does repeat the sound after you, then reward him much more than when there were no sounds.

). Extend the encouragement to the child and say the desired sound. If the child makes or tries to make a sound, immediately reward him. If there are no sounds, then give him encouragement after a pause of one second. Remember, your goal now is to form an association between the sound and the reward, so the child doesn't have to say anything at all. However, if the child does repeat the sound after you, then reward him much more than when there were no sounds.

Rewards: For this program, the best rewards are those that don't have to be constantly taken back from the child. For example, it could be small bites of a child's favorite treat, or pleasurable adult activities such as tickling. It is best to avoid rewards that will have to be taken back (such as toys) unless the child has other types of rewards. Some children may become frustrated if a toy is taken away from them every five seconds.

Note: It usually takes hundreds of trials for a child to successfully imitate the sound of speech in this program. Gather data on what sounds your child is making to determine what sound should be the next target. Subsequently, from training in the "stimulus-stimulus" program, you can move on to training in requests. (See also How to Teach Your Child to Speak.)

Gather data on what sounds your child is making to determine what sound should be the next target. Subsequently, from training in the "stimulus-stimulus" program, you can move on to training in requests. (See also How to Teach Your Child to Speak.)

2. Vocal play

Purpose: To combine or create an association between speech sounds and fun activities that the child prefers.

Practice: Start playing with your child or doing something he or she usually enjoys. While playing, as often as possible, make simple sounds and vocalizations that are usually associated with such a game (for example, "Beep-beep!", "Bang!"). If the child spontaneously repeats the sound after you or starts babbling, immediately praise him as much as possible and encourage him. However, do not ask or demand that the child say something.

Over time, the child will begin to associate funny sounds with play and will be more likely to imitate these sounds in the future.

Reward: Any game or favorite activity of the child. You can keep an extra reward (such as your child's favorite treat) handy just in case, to reward any spontaneous speech sounds.

Note: In this program, it is useful to set a timer for a certain time and count how many speech sounds the child makes so that you can track his progress.

3. Teaching requests with gestures simultaneously with words (total communication method)

Purpose: To create an association between speech sounds or words and specific rewards during teaching gesture requests.

Practice: When teaching gesture requests, always say the name of the item during each teaching step. If the child has already learned to ask with a gesture, then name the reward when you give it to the child. If the child is learning a new gesture, name the reward when prompting the child for the sign and then give the reward. Over time, the child will learn to associate the word with the reward, and this will increase the likelihood of word attempts and spontaneous verbal requests. (See also How to teach your child to ask with gestures.)

(See also How to teach your child to ask with gestures.)

Reward: An item that the child asks for with a gesture.

4. Reward all sounds

Purpose: Reward all the sounds your child makes so that he is more likely to repeat them in the future.

Practice: Give your child encouragement and praise (Example: "Good job saying 'a'!") every time he or she makes a speech sound. This should be done throughout the day.

Reward: It is best to choose several rewards from different categories (eg different types of products, different activities, different toys). Otherwise, the child will quickly get fed up with the reward.

When the child can already imitate (or tries to imitate) basic speech sounds, other procedures can be used to form articulation and pronunciation of words. (Also see Vocal Imitation Teaching Technique and How to Help Your Child with Autism Speak More Clearly.