How to restrain a child safely

How To Restrain a Child Who Is Out Of Control? 2 Safer Ways

WARNING: Physical restraint or seclusion should only be used if the child’s behavior poses imminent threat of serious physical harm to themself or to others and if other modes of intervention has been ineffective. However, it should be discontinued as soon as the child calms down and changes their behavior. *Before reading this article please make sure to read our Medical Disclaimer*

The idea of physically restraining someone as young and vulnerable as a child should seem appalling for good reason. It’s the very last resort for when your child’s tantrums escalate to becoming a credible threat, putting themselves and others at risk of harm. That’s precisely why you should learn how to restrain them properly and mitigate as many potential risks as possible.

Restraint isn’t inherently bad, and physical restraint is indeed warranted in some urgent situations. When physically restraining a child that’s out of control, your priority is to limit their means of receiving/inflicting bodily harm until they eventually calm down.

Only use physical restraint when the child poses a threat, and don’t endanger their well-being while restraining them. This should never be used as a tool for discipline or compliance. Lastly, after the situation passes, focus on discerning what triggered this response, along with the best way to prevent these cases from reoccurring.

We sincerely hope that you’d never have to restrain a child who’s out of control, but it’s better to be safe than sorry. Restraining anyone, much less a child, can’t be done in a safe way: only in safer ways. We’ll share every trick and tool at our disposal to make sure your child’s episode can be managed with the least risk possible – on everyone’s part!

Clarifications on Restraint

A note: restraint isn’t just pinning your child down with all your might, hoping they’ll stop making a scene. Restraint is simply stopping your child from exacerbating a situation that could cause harm, using as little force as possible. It’s a physical action, but it isn’t inherently violent.

It’s a physical action, but it isn’t inherently violent.

Do you grab your child when you see them try to run around recklessly in a parking lot? That’s restraint too. You apply restraint on a pretty regular basis to safeguard your child’s well-being. There’s no denying that this type of action is needed in some cases.

That said, the type of physical exertion needed to fully restrain a child lashing out carries notable dangers. There isn’t a 100% guaranteed way to contain their episode safely and consistently – it’s the last resort for a reason. They could get hurt even if you follow the guidelines to the letter.

How this turns out would also depend on the intensity of their tantrum, your child’s immediate environment, and the type of preventative/restraint measures taken.

WARNING: Physical restraint or seclusion should only be used if the child’s behavior poses imminent threat of serious physical harm to themself or to others and if other modes of intervention has been ineffective.

However, it should be discontinued as soon as the child calms down and changes their behavior.

Keep Your Emotions In Check

Physically restraining a child involves firmly exerting only the bare minimum force needed to prevent them from endangering themselves. You need to have a calm, reassuring presence while doing so, which is much easier said than done.

Keeping one’s emotions in check during such an ordeal is difficult, and you might be overcome with anxiety or some other compromising emotion. These greatly inhibit your ability to respond, heightening the risk carried by these already-dangerous situations.

For some people, these feelings may not abate in time to allow a proper response to handling a child physically lashing out. If that’s the case, it would be better for one to extricate themselves from the scene rather than act in a manner they aren’t capable of sustaining.

There are two key emotions to be wary of when handling an out-of-control child: fear and anger.

Fear

Fear could leave you unable to respond decisively, putting both you and your child in harm’s way. Most professionals trained to physically restrain children operate in pairs or groups – this way, they ensure that:

a) the decision of physical restraint was justified.

b) the application of restraint was appropriate.

c) the situation is handled objectively.

If you’re administering physical restraint on your own, the last thing you want to be is emotionally compromised.

If you can’t guarantee everyone’s safety (you, your child, and bystanders, if any) to a reasonable extent, it would be a better course of action to leave and let the tantrum die down. That said, this may not be an option in certain cases (i.e. child actively seeking to harm you or themselves, fragile or dangerous environment near your child).

Mentally prepare yourself for this eventuality to avoid being rendered ineffectual. If you find yourself in just this situation, focus on getting your bearings. Calm yourself down with deep breathing exercises, then act according to your best judgment.

If you find yourself in just this situation, focus on getting your bearings. Calm yourself down with deep breathing exercises, then act according to your best judgment.

Anger

Alternatively, you might meet your child’s display with indignance or even rage. Keep your fury in check, as you run a serious risk of utilizing excessive force and subsequently harming your child. Physical restraint is a tool only used in emergencies, and should not be done with even the slightest hint of anger on your mind.

An investigation into Illinois public schools that permitted physical restraint drew jarring results. Thousands of cases had school children forcibly restrained for disobedience, with this last-ditch technique to protect everyone’s safety being utilized inappropriately as a disciplinary tool. Many of these children suffered from abrasions, bruising, and psychological trauma due to heavy-handed misapplication of physical restraint by frustrated authority figures.

Physical restraint is not a disciplinary tool, and should never be used to force compliance. Don’t let frustration or anger seep into your actions – keep the child’s safety at the forefront of your thoughts. Physical restraint is a tool meant to MINIMIZE harm, not cause it.

Don’t let frustration or anger seep into your actions – keep the child’s safety at the forefront of your thoughts. Physical restraint is a tool meant to MINIMIZE harm, not cause it.

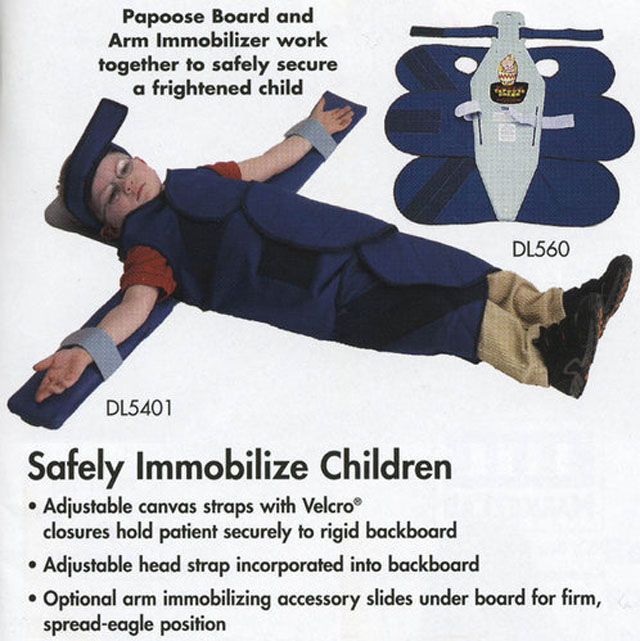

Standing Restraints (Wrist)

This restraint is a technique that aims to pacify someone standing up, and doing so requires the following steps:

- Approach the child in question (preferably from behind or from their side)

- Grab onto the child’s wrists (your right hand holding onto their left wrist, and your left hand holding onto their right wrist)

- Cross the child’s arms over their chest (so that both their hands are now near the opposite shoulder)

- Pull backward, so that the child is leaning back onto you

- Release child immediately after they settle down

Seated Restraints (Arms)

This restraint technique is much easier to manage, though it works best with another set of hands helping out. The proper procedure to follow is down below:

- Using both hands, grab hold of one of the child’s arms

- (After partner grabs hold of the other arm) guide subject to sit on the chair

- Release child immediately once they settle down

Life-Threatening Actions To Avoid

Physically restraining a child is very dangerous. Don’t ever forget that you’re pitting an adult’s strength and weight against a child’s fragile, developing body. It’s easy to make devastating mistakes in the heat of the moment, and these could seriously harm or even cripple your child.

Don’t ever forget that you’re pitting an adult’s strength and weight against a child’s fragile, developing body. It’s easy to make devastating mistakes in the heat of the moment, and these could seriously harm or even cripple your child.

Don’t put pressure on joints

Pressure on joints can cause a significant amount of pain, which is the last thing you want when physically restraining someone. It can take upwards of thirty minutes for someone being restrained to stop lashing out, and excess pain will needlessly extend the duration of this grueling process.

Misplaced pressure could also lead to pinched nerves, which when left untreated lead to long-term nerve damage. It could easily lead to cases of bad bruising, sprains, or even fractures. In certain cases, you may even permanently compromise your child’s range of motion.

In the heat of the moment, it’s hard to tell if you’re applying more pressure than you need to restrain them. Be extra mindful of this concern and keep clear of their joints.

Don’t touch their neck

The degree of uncontrolled movement is very high in these situations, making any contact with the neck dangerous. The neck is a tight network that houses nerve bundles, muscles, and bones working in very close proximity to one another. It’s very vulnerable to any sort of compression damage, creating a high risk of long-term harm.

Keep your hands away from their neck. There’s no reason to apply pressure there – focus on limbs and other extremities lashing out. It’s also extremely easy to accidentally scratch someone’s neck while restraining them, leading to further agitation and potential for infection.

Don’t obstruct their airway

The moment the person being subdued shows ANY signs of breathing difficulty, you need to release them promptly. There are no exceptions here, and ignoring this sign could very well cause permanent brain damage or even kill the subject being restrained.

They might be suffering from something known as compression asphyxia. This is a form of suffocation caused by significant pressure or weight being forced onto a person’s upper body. Physical restraint techniques focus on inhibiting the person’s means to lash out (i.e. arms, legs, waist) rather than forcing them to remain in one place.

This is a form of suffocation caused by significant pressure or weight being forced onto a person’s upper body. Physical restraint techniques focus on inhibiting the person’s means to lash out (i.e. arms, legs, waist) rather than forcing them to remain in one place.

We repeat: there is no reason to leverage your weight onto the child’s upper body. This was especially horrendous with prone restraint techniques, which had individuals pinned face-up on the ground. The technique was barred from use against restraining children for good reason, as it carried needless risk and no real safety advantage over standing and seated restraints.

Another threat you may encounter is positional asphyxia, which is a form of suffocation that comes from the environment obstructing one’s airways. This is common with babies falling asleep with their faces covered, but can also occur when one is pushed to the ground.

Supine restraints had subjects pinned down face-first onto the ground and carried a significant risk of positional asphyxia. Like prone restraints, this technique was eventually deemed inappropriate and needlessly cruel for usage against children lashing out.

Like prone restraints, this technique was eventually deemed inappropriate and needlessly cruel for usage against children lashing out.

WARNING: Physical restraint or seclusion should only be used if the child’s behavior poses imminent threat of serious physical harm to themself or to others and if other modes of intervention has been ineffective. However, it should be discontinued as soon as the child calms down and changes their behavior.

Don’t Make Physical Restraint a Frequent Occurrence

Having to be forcibly restrained from an outburst can be a traumatizing experience, and your child’s mind will race to find ways to reconcile what happened with what they did. The last thing you want them to do is normalize this experience.

Children won’t implicitly understand that physically restraining them was done for their safety. They might see it as something you’d do when they act out, so be quick to clarify the mistaken assumption. They shouldn’t see it as something they deserve for bad behavior.

After they cool down, make sure you set time aside for a proper conversation. Talk about what transpired, why physical restraint was necessary, and how the two of you can avoid it moving forward. Your child must understand the incident was not their fault, and that the measures taken aren’t intended to be a disciplinary method.

More cases of physical restraint also mean more chances for your child to get hurt. They’ll eventually learn to accept it, and may even expect this behavior in their daily lives. They might even begin physically restraining other children when they start to act up! You must convey to them that this isn’t something one does, except for the most urgent safety situations.

Look Into What Led To This Event (Short and Long Term!)

Prevention is key to minimizing the physical and emotional toll of this ordeal for everyone involved. Your child’s outburst likely had some warning signs crop up, so be sure to reflect on anything you might have missed. Pay close attention to how things escalated, why they escalated, and what might be done to keep things under control.

Pay close attention to how things escalated, why they escalated, and what might be done to keep things under control.

We’ve included a few examples for you to look out for down below.

- Were there any types of medication (introduction or removal) involved?

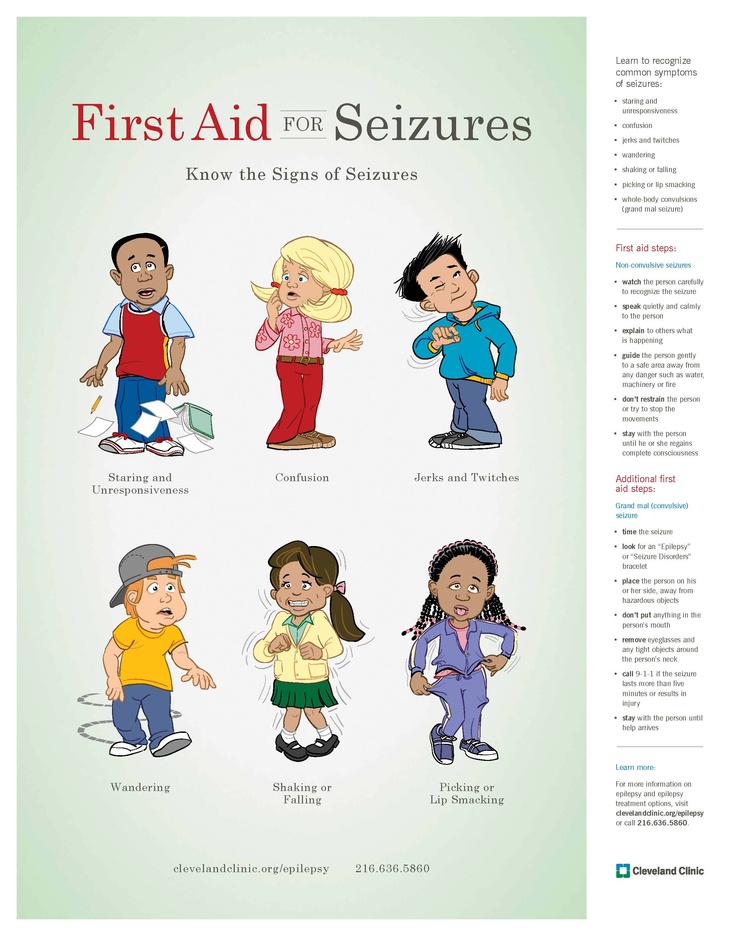

- Did your child experience any signs of a panic attack (i.e. difficulty breathing, dizziness, chills) before or during the incident?

- Was there any type of environmental (i.e. loud noises) or emotional (i.e. anger directed at them) stimuli involved that might have exacerbated the situation?

- Have they shown signs of emotional duress before this episode? When did the first few signs appear? What were the last signs before the incident?

Try to think about what else could have triggered their troubling response, and be sure to ask your child plenty of questions to fill in any knowledge gaps (once they’ve calmed down).

Final Thoughts

Physically restraining a child is a last-resort effort to prevent them from causing or experiencing harm, and should never be done lightly. Your priority while restraining them should be minimizing the risk of bodily harm, not restricting their movement.

Your priority while restraining them should be minimizing the risk of bodily harm, not restricting their movement.

Clarify that this was done for their own good, not as a disciplinary method. Be sure to look into what caused their episode to begin with, and look for measures you can take to mitigate them.

Things to think about before restraining your child SEND VCB Blog 6

Parents of children who have an additional need and who also can be violent at home often ask me how to best restrain their child, or if I know of any training providers who could train them in restraint methods. Restraining children is such a difficult issue, and everyone understandably has very strong views on it.

Broadly speaking, there are two opposing points of view among parents of children with SEND VCB (Special Educational Needs and Disability, Violent and Challenging Behaviour). One set believe that their child’s violence and self-injurious behaviour is so extreme that restraint is, at times, an absolute necessity. The other group of parents believe that restraint should never ever be used, and if it is used, it should only ever be as an absolute last resort when there is imminent and significant danger to life.

The other group of parents believe that restraint should never ever be used, and if it is used, it should only ever be as an absolute last resort when there is imminent and significant danger to life.

The two viewpoints can seem so diametrically opposed that there is no, or very little common ground, and this can lead to disagreements, conflicts and heated debate which is always sad. Parents can find these disagreements very hurtful and divisive, when ideally we should all be pulling together in the same direction and supporting each other.

However, “restraint” as a word is very emotive, and can conjure up images of big burly blokes pinning a child to the ground, and sometimes by using that word parents are giving completely the wrong impression of what they are actually doing. Sometimes it’s a parent’s role to prevent our children doing something, and most parents have physically held on tightly to a small child near traffic to keep them safe. If by “restraint” what you really mean is “I had to hold him back to stop him kicking his brother” it’s probably better if you explain exactly what you did and why, and don’t actually use the word “restraint” in case it wrongly rings alarm bells in others.

Restraint training is now increasingly called “Safe Handling”, and training is generally only available to staff members from organisations such as schools, local authorities, play schemes, respite centres or similar facilities. It is very difficult for parents to access this sort of training, and there are some very good reasons for this. Here are just some of them.

1. When children are in the midst of a SEND VCB episode, they are not misbehaving, they are in the deepest distress possible. Their behaviour is a direct result of their “Fight and Flight” response being triggered by extreme anxiety and fear. At that moment, they are not aware that they are lashing out at those they love the most, instead, they believe that they are fighting for their very survival. To restrain a child who is already in the deepest of distress will only escalate their fears and anxieties, and is more likely to escalate the situation rather than to calm it down.

2. A good way to think of it is to compare a child in the middle of a SEND VCB episode with an injured wild animal, who will also have had their “fight or flight” response activated. The wild animal is hurt and scared, and you only want to help, but if you approach and try to “restrain” them to take them to the vet for help, they will panic even more, and kick and bite and scratch all the more, trying to escape.

The wild animal is hurt and scared, and you only want to help, but if you approach and try to “restrain” them to take them to the vet for help, they will panic even more, and kick and bite and scratch all the more, trying to escape.

3. When staff restrain a child, they are working as part of a team. They would be unlikely to restrain alone, or to take a decision to restrain on their own either. During the act of restraining, there are likely to be colleagues in the vicinity who will witness what is happening, and who can corroborate that such actions were justified, that they were carried out according to policy, and that undue force was not used. Every incident that restraint is used is recorded. Organisations also have robust insurance policies which are likely to include legal cover for staff members who are accused of wrong-doing in relation to restraining. Parents have none of these safeguards, checks and balances.

4. A family home is a completely different environment which makes it a very different situation regarding restraint. Often during SEND VCB episodes, there is only one adult present, which means there are no witnesses to corroborate that it was done fairly, with no undue force being used. Acting alone makes parents incredibly vulnerable to accusations of abuse. How can a parent defend themselves if a bruise is noticed on a child a few days later, and the child tells their teacher that “mummy did it”? Sadly though, it may not just be a bruise. Restraint injuries can be much more serious, including broken bones or dislocated joints, and tragically sometimes, even death. Restraint can and does go wrong, with catastrophic results sometimes, even when it’s being carried out by members of staff who have been highly trained in safe methods of restraint or safe handling.

Often during SEND VCB episodes, there is only one adult present, which means there are no witnesses to corroborate that it was done fairly, with no undue force being used. Acting alone makes parents incredibly vulnerable to accusations of abuse. How can a parent defend themselves if a bruise is noticed on a child a few days later, and the child tells their teacher that “mummy did it”? Sadly though, it may not just be a bruise. Restraint injuries can be much more serious, including broken bones or dislocated joints, and tragically sometimes, even death. Restraint can and does go wrong, with catastrophic results sometimes, even when it’s being carried out by members of staff who have been highly trained in safe methods of restraint or safe handling.

5. We are emotionally involved with our children, and our relationship with them is entirely different. This means that restraining an already highly distressed child risks breaking down their trust in us, or their belief that we love them. It also means that when our children are in the middle of a SEND VCB episode, we are likely to also be triggering our own “Fight and Flight” responses. When that happens, we are unable to access the frontal lobe part of our brain which is responsible for our judgement, problem solving, self-control and rational thinking. Basically, if we restrain a child in this “heat of the moment” situation when we are unable to use these essential skills or to think on our feet, we inadvertently put both ourselves and our child at risk of physical injury.

It also means that when our children are in the middle of a SEND VCB episode, we are likely to also be triggering our own “Fight and Flight” responses. When that happens, we are unable to access the frontal lobe part of our brain which is responsible for our judgement, problem solving, self-control and rational thinking. Basically, if we restrain a child in this “heat of the moment” situation when we are unable to use these essential skills or to think on our feet, we inadvertently put both ourselves and our child at risk of physical injury.

6. A child may be able to accept a staff member restraining them, but they may never fully understand why their parent did it to them, and this can have a long term and detrimental effect on the parent/child relationship, when it is of paramount importance to strengthen this bond and relationship as part of being able to support them to overcome their violent behaviours. A child will not have the maturity to understand that a parent restrained them to protect them from harm, they are likely to remember the incident in terms of that mummy or daddy “tried to hurt me”.

7. In that moment of restraining our own child, we are teaching them that physical force is legitimate and can be used to get our own way. This is exactly the lesson we do not wish to teach a child who has SEND VCB.

8. To attend a course on restraint or on “safe handling” normalises and legitimises doing this to our children. With the best intentions in the world, it changes the landscape so that restraint is often no longer seen as the absolute last resort, it can start to feel that it’s OK to use it as the first resort, or perhaps the only resort.

9. Most reputable safe handling training providers won’t accept parents onto their courses because they know that there can be no on-going workplace support nor a team approach or implemented policies and procedures to be followed. They can’t take the risk of an unsupervised lone parent restraining a child and it could also have an impact on their insurance.

10. A small child of perhaps seven years old or under can be relatively easy to restrain. However, children grow up and get bigger and stronger. Ideally, we should be working with our children when they are still small on strategies, techniques, emotional regulation and lots of other life skills that can help them find other ways to express their unmet needs besides resorting to violence. If we concentrate on restraint as a primary method of controlling them when they are small, what happens when they are sixteen years old, bigger and stronger than we are, and restraint is no longer an option?

However, children grow up and get bigger and stronger. Ideally, we should be working with our children when they are still small on strategies, techniques, emotional regulation and lots of other life skills that can help them find other ways to express their unmet needs besides resorting to violence. If we concentrate on restraint as a primary method of controlling them when they are small, what happens when they are sixteen years old, bigger and stronger than we are, and restraint is no longer an option?

11. When we restrain, we are actively seeking to solve the situation from an adult perspective, instead of imparting the essential tools and practice time that a child needs to be able to find their own solutions to self-regulate their emotions.

12. Would you ever restrain an adult stranger in the street? If so, what set of circumstances would there have to be for you to actively seek to stop an adult moving around of their free will? Perhaps they are wielding a knife, or threatening to push someone under traffic? It would have to be extreme circumstances for you to even consider intervening to restrain a fellow-adult. It would also help to have witnesses to speak up for why you did it, and you would also need to have enough of a reason to hold up in a court of law if the person you were restraining accused you of assault. It would be a one-off, once in a lifetime event, and something that you would wish you hadn’t had to get involved in. When you are considering restraining a child, it can be a good idea to use the same set of criteria that you would use before making a decision to be a “have-a-go-hero” in the street. Is anybody’s life in imminent danger? Is there any other way I could solve this crisis? Are there witnesses who can stand up for me? What can I say to a judge in court to absolutely prove to him or her without a shadow of doubt that I had no choice? With our children, and in our own homes, there is nearly always a choice, although when our brains are not functioning correctly due to the fight and flight instinct, those choices are not always obvious. In the same way that I can’t tell you that you must never restrain a stranger in the street under any circumstances, it would be equally irresponsible of me to say “never” in relation to a child.

It would also help to have witnesses to speak up for why you did it, and you would also need to have enough of a reason to hold up in a court of law if the person you were restraining accused you of assault. It would be a one-off, once in a lifetime event, and something that you would wish you hadn’t had to get involved in. When you are considering restraining a child, it can be a good idea to use the same set of criteria that you would use before making a decision to be a “have-a-go-hero” in the street. Is anybody’s life in imminent danger? Is there any other way I could solve this crisis? Are there witnesses who can stand up for me? What can I say to a judge in court to absolutely prove to him or her without a shadow of doubt that I had no choice? With our children, and in our own homes, there is nearly always a choice, although when our brains are not functioning correctly due to the fight and flight instinct, those choices are not always obvious. In the same way that I can’t tell you that you must never restrain a stranger in the street under any circumstances, it would be equally irresponsible of me to say “never” in relation to a child. However, please be aware that you are making yourself very vulnerable to child protection proceedings, and please be sure that there really is no other choice. I would also strongly advise that you write down everything that happened, and sign and date it so that you have a clear record of the incident from your perspective.

However, please be aware that you are making yourself very vulnerable to child protection proceedings, and please be sure that there really is no other choice. I would also strongly advise that you write down everything that happened, and sign and date it so that you have a clear record of the incident from your perspective.

The reality is that there are many parents who may read this who are using restraint with their children, and if that’s you, the last thing I want is that you feel blamed or judged for using restraint. When our children first develop violent behaviours at home it is so bewildering and shocking that we will instinctively do whatever we can to stop it happening, and that often means that restraint becomes an established pattern and response. When SEND VCB first starts happening very few parents understand that it is due to anxiety, distress and fear, and so it gets treated as a “behaviour” issue, with traditional “carrot and stick” parenting techniques used to try to curtail it. It can be years before parents understand that it’s about anxiety rather than naughtiness, and then a parent has to make a huge adjustment in their parenting approaches to be able to implement the sort of strategies that can work well to turn children’s behaviour around.

It can be years before parents understand that it’s about anxiety rather than naughtiness, and then a parent has to make a huge adjustment in their parenting approaches to be able to implement the sort of strategies that can work well to turn children’s behaviour around.

At the start of a family’s journey with SEND VCB, restraint can seem like the only thing that can stop the violence in its tracks. It takes time to learn about different approaches, and to learn new skills that we can use instead. So many families will feel they may need a lot of time while they learn and then implement other strategies before they feel able to move away from restraining,If that’s where you and your family are now, it would be great if you can aspire towards a time when restraint is no longer used at home, as much to protect you as to protect your child.

It’s also easy for some parents in the thick of things with SEND VCB as a daily occurence to think that maybe other parents don’t need to use restraint. They may think that maybe other people’s children aren’t as extreme, or as frighteningly violent as their own are, but I promise you that isn’t the case. It takes time, there are no easy solutions or overnight quick fixes, but you can turn things around for your child. There are now numerous families I know who have successfully made huge progress with their children’s SEND VCB. Some of them a year ago were using restraint methods every day or even several times a day and now they simply don’t need to at all. It has taken enormous effort, tenacity and gritty determination, and there are some days, or even weeks, when nothing seems to work and things seem to be going backwards. Yet they have persevered, and there are now a significant number of families who have moved on from restraint, and are leading their children into calmer, happier and safer futures. This time last year they didn’t believe it was possible either.

They may think that maybe other people’s children aren’t as extreme, or as frighteningly violent as their own are, but I promise you that isn’t the case. It takes time, there are no easy solutions or overnight quick fixes, but you can turn things around for your child. There are now numerous families I know who have successfully made huge progress with their children’s SEND VCB. Some of them a year ago were using restraint methods every day or even several times a day and now they simply don’t need to at all. It has taken enormous effort, tenacity and gritty determination, and there are some days, or even weeks, when nothing seems to work and things seem to be going backwards. Yet they have persevered, and there are now a significant number of families who have moved on from restraint, and are leading their children into calmer, happier and safer futures. This time last year they didn’t believe it was possible either.

If you want to do it too we’re all here to help. See below for links to other resources, join our closed FB support group for parents or come to one of our Workshops. You aren’t alone and things can and do get better.

You aren’t alone and things can and do get better.

More Support

Webinars and training, Facebook Support, resources to read or watch

Have you been to one of Yvonne’s webinars yet?They cover a range of topics relating to behaviour issues in children with additional needs, and are packed full of insights and strategies that can help you to support a child in moving beyond their extreme behaviour patterns towards much happier and calmer times with a brighter and much more hopeful future to look forward to. Due to NHS England Funding, current webinars only cost £2.50 each, with free places for families in financial hardship. For more information please click this link – https://yvonnenewbold.com/webinars-workshops-courses-and-books/

Yvonne runs a Facebook Page called The SEND Parent’s Handbook for parents of children with disabilities and the professionals who work with their families.

If you are a parent of a child who has SEND VCB, Yvonne also runs a closed Facebook Support group, which you would be welcome to join, called The SEND VCB Project – Support Group for Families

There is another Facebook Page called The SEND VCB Project – Public Page which is for anyone to find out more about this and closely related issues, and it’s open to everyone

Resources on SEND VCB – for families and professionals who work with children or vulnerable adults

If you’d like to buy a copy of “The Special Parent’s Handbook”, which is the book I wish someone had been able to give me on the day Toby was born.

Here’s

the link to order yoursAlternatively you can order it from Amazon – here’s the link to the page

Yvonne is a member of the Amazon Affiliates Program which means that if you click on an Amazon link from this website and subsequently make a purchase, she will be paid a small commission.

Like this:

Like Loading...

How not to lose your child in the crowd - Child safety

At concerts, during mass celebrations, and just in shopping centers, it is not uncommon for children to suddenly disappear from sight. How not to lose your baby in a crowd of people? Follow a few simple guidelines.

Dress your child in bright clothes

The more visible your baby's outfit, the better. Due to their small stature, children may simply not be visible in the crowd, although they may be very close. Give your child an umbrella or a flag - anything that can be held high above their head will do. Explain to the child in advance - if you missed each other, he needs to stay in place and raise his inventory up.

Give your child an umbrella or a flag - anything that can be held high above their head will do. Explain to the child in advance - if you missed each other, he needs to stay in place and raise his inventory up.

Take a photo of your baby before going out

Make taking a photo before leaving home a good tradition. The loss of a child is an acute stressful situation for any person, so there are often cases when a parent, out of excitement, could not remember what exactly his child was wearing. In case the situation goes too far, this photo will be the most recent image that the police, rescuers and volunteers can use when conducting searches.

Designate a meeting place in advance

To avoid a situation in which you and your child are unsuccessfully running around looking for each other, it is worth agreeing in advance where you will meet if you get lost. The landmark should be noticeable, understandable and accessible to the child. Do not use toilets or retail outlets as collection points - there may be several on site. It is best to immediately go with the child to a noticeable monument or fountain to make sure that the baby sees it and understands what it is about. If you are not sure that the child will be able to get to the collection point on his own, teach him to stay where he is and wait for you.

It is best to immediately go with the child to a noticeable monument or fountain to make sure that the baby sees it and understands what it is about. If you are not sure that the child will be able to get to the collection point on his own, teach him to stay where he is and wait for you.

Make sure that the child knows important information by heart

Fright can make the child forget not only your name, but also his own. Information about his name, how old he is, the names and surnames of the parents can help if someone finds the child. Put notes with your contacts in the pockets of children's clothes. By the way, this is also true for older people.

Tell us about the rules of safe behavior. Yes, again

Not every adult who volunteers to help wishes well for your child. As numerous social experiments show, children continue to leave with strangers, despite the fact that they know that this is not to be done. To gain the child's trust, the attacker may introduce himself as a "friend of the mother" and say that you asked to take him home. In such a case, come up with a password that will allow the baby to understand who he can really trust. Only the closest people of the child should know this password.

In such a case, come up with a password that will allow the baby to understand who he can really trust. Only the closest people of the child should know this password.

Show someone to ask for help

Yes, you can't go out with strangers. But the child should also know where he can ask for help. Show your child pictures of emergency workers and volunteers, tell them what uniforms they have. Be sure to do it "live" at the event itself! Teach your child to dial 112, while explaining in what situations it can be called.

Practice

Rehearse your child in an emergency in a playful way. By roles, you can act out a dialogue with the policeman, to whom the child turned for help. In a calm environment, make sure your little one can find a collection point in the store. Such training will help the child not to get lost if he really gets lost.

Don't panic

If you've lost each other, it's important not to panic. Tell the child in advance that in this situation you will definitely find him, the main thing is to follow all the instructions. Try to keep calm yourself. It is important for you to think clearly and think through all possible search scenarios.

Try to keep calm yourself. It is important for you to think clearly and think through all possible search scenarios.

Proper and safe movement of a child with cerebral palsy

04/26/2018

The article was prepared by Svetlana Nailevna Aryapova, an ergotherapist at ANO MIBC Elizabethan Garden, for the Resource Center for providing information and methodological assistance on the education, development and habilitation of children with cerebral palsy.

Hello, I'm an ergotherapist!

Today I will tell you about the correct and safe movement of a child with cerebral palsy.

Recently, much attention has been paid to this issue. This is due to the need to prevent back pain and damage to the musculoskeletal system among parents and specialists who are forced to manually move children with motor impairments during the day.

Back pain is a common cause of partial or complete disability of social workers and health care workers. For example, in the UK, back pain that nurses develop as a result of performing their duties in 35% of cases is associated with the movement of patients. Back pain occurs most often as a result of moving the patient manually or alone. According to studies, most often (in 26%) back pain occurred when moving from bed to chair, to a wheelchair or bedside toilet and back, when moving from a wheelchair to a toilet, chair and back.

Back pain occurs most often as a result of moving the patient manually or alone. According to studies, most often (in 26%) back pain occurred when moving from bed to chair, to a wheelchair or bedside toilet and back, when moving from a wheelchair to a toilet, chair and back.

The second most common cause of back pain is pulling the child up to the head of the bed. People who, due to the specifics of their duties, are forced to move children and adults with cerebral palsy injure their backs more often than people working in the extraction of metal ores. Tension in the back occurs after the first minute of the bend.

So, let's talk about what kind of work we do when we move certain loads, what kind of load our body experiences and what the risk is when moving. Load types can be divided into static and dynamic. Dynamic ones arise when we move an object in space. This includes transferring the client from bed to chair, when lifting the client to a standing position, at

pulling the recumbent to the head of the bed, even with the help of a sliding sheet. In the case of a static load, we keep the moving object in a certain position, and here the main task is to maintain the original position, and not move the object. Examples of static loads, holding the client in a sitting position while dressing.

In the case of a static load, we keep the moving object in a certain position, and here the main task is to maintain the original position, and not move the object. Examples of static loads, holding the client in a sitting position while dressing.

The guideline for the safe movement of goods in industry indicates the weight allowed for movement by one person: from 6 to 25 kilograms - depending on the initial position of the mover and the position of the object being moved. So, if you lift a load with outstretched arms, i.e. at a distance from you, you experience a stronger dynamic load than if you were lifting the load with your arms bent, i.e. holding directly next to the body. Also, lifting from the floor is fraught with more load than lifting from the level of the hips. Despite all this, we must firmly grasp that the total or partial lifting of any objects should be minimized or completely eliminated.

Lifting loads in pairs also carries many risks.

1. Both movers are forced to be in non-optimal postures (bending or turning the torso). Otherwise, it will be difficult to keep the object of movement.

Both movers are forced to be in non-optimal postures (bending or turning the torso). Otherwise, it will be difficult to keep the object of movement.

2. Mismatch between the height of the movers and their physical capabilities creates additional dynamic loads, as well as the risk of damage. Inconsistent actions when moving lead to the same. Therefore, this method of movement cannot be recommended as safe either.

Consider the dynamic loads that occur when moving away from yourself and towards yourself.

1. The object has inertia. Therefore, by pulling or pushing it, we give it acceleration, and then, at the end of the movement, we are forced to dampen the object’s speed in order to prevent uncontrolled movement.

2. When moving an object on wheels, uncontrolled movement (excessive acceleration) is also possible, which also causes an increase in the dynamic load that occurs when the object’s speed is reduced.

What to do? It is necessary to control the speed of the object and thereby prevent uncontrolled movement of the object. When turning the client in bed, it is more expedient to turn him towards you, while placing his closest foot on the bed, which in turn frees the person moving from the effort to slow down the client's movement.

When turning the client in bed, it is more expedient to turn him towards you, while placing his closest foot on the bed, which in turn frees the person moving from the effort to slow down the client's movement.

Our body is designed for constant movement, it is movement that allows muscles and joints to work in different modes and not get tired.

Consider static loads. In vain underestimate static loads. Our back is not designed to stay in a bent or extended state for a long time. It works without tension and is more efficient if we keep it straight and maintain the natural curves of the spine. Studies have shown that tension in the back occurs after a minute, when we hold the body in a forward bend position. In addition, if you were standing in a crouch and then decided to hold an object lifted in front of you, then the back muscles will not be able to develop effective tension and hold the pose so that it is not traumatic. The muscles of the back contract effectively if we keep our back straight. Static muscle tension is also affected by the stability of the lifting posture. However, static loads are common for caregivers. Some studies have shown that they account for 20-25% of working time.

Static muscle tension is also affected by the stability of the lifting posture. However, static loads are common for caregivers. Some studies have shown that they account for 20-25% of working time.

Do not bend your back more than 30% for more than a minute. Choose the right height for furniture and objects to be held.

Tips for moving children with cerebral palsy on special equipment on wheels

1. Work only on serviceable equipment!

2. Use your body weight: lean forward slightly when pushing the object away from you and slightly back when pushing towards you.

3. Never push an object away from you at the same time as turning it. If it is not necessary to change the direction of movement, then first slow down and then turn.

4. Never rotate an object around you! If you need to rotate an object, give yourself room to maneuver and rotate the object smoothly 360 degrees while pushing the object away from you.

5.Move the object smoothly and evenly. Use the 3 second rule. Brake and accelerate evenly for at least three seconds.

Use the 3 second rule. Brake and accelerate evenly for at least three seconds.

6. If you need to move over a long distance, then it is better and more correct to move at a uniform speed than to accelerate and brake.

Characteristics of the load carried by parents and professionals

A person, as an object of movement, is characterized by a number of features that increase the risks when moving.

1. A person is a rather heavy and bulky load. Never pick up or lift a client alone. This is beyond the power of anyone.

2. The human body consists of the torso, head and limbs. The limbs and head can move relative to the body and thus affect the movement of the client's center of gravity.

3. The person you are moving has desires, certain likes and dislikes for certain situations. You started moving the client, and he started talking to you about something interesting, turns to you. At this time, its center of gravity changes significantly.

4. It is necessary to take into account the individual characteristics of the client. Skin conditions, presence of bandages, medical devices.

What movements occur in the group

Moving a child to a stroller

Starting position of the child: lies on the couch.

Drive the child seat to the sofa, set the desired height, put the brake on the seat. Raise the footrests, for those children who can lean on their feet. Attention! Plan your move. Tell your child about it. Ask him to perform actions that are feasible for him. Sit the child down, turning him on his side, dangling his legs from the sofa. Grasp behind the shoulders and, holding, plant next to you. Place the child on their feet in the gap between the raised footrests. Having unfolded it, put the booty on a chair.

If the child cannot rest on his feet. Place the child on the buttocks, holding the child by the shoulders with your hand and supporting the neck. Pull the child to your knees, grouping him as much as possible. Hold him close to you and stand up. Sit the child in a chair.

Pull the child to your knees, grouping him as much as possible. Hold him close to you and stand up. Sit the child in a chair.

Impossible! Lower the legs of a child who is lying on his back. This creates a lot of tension in the lower back. Grab and hold the child by the shoulders when lifting. To take for lifting by the hands and lift the child on his outstretched arms.

For movers, do not lift the child in a standing position from the sofa to avoid unnecessary weight load on the back. If you are standing and the child is sitting on the surface at the level of your stomach, then you need to press him and remove him from the surface.

Transferring a child from chair to bed

Look around the area. Is there enough room to move? Roll the chair with the child as close as possible. Set the level of the stroller at the level of the bed.

Lock the brake. Attention! Before moving, unfasten all straps that secure the child in the seat, otherwise you will have to lift not only the child, but also the stroller.

If the child is resting on their feet, raise the footrests. Lift the child out of the chair, letting him rest on his feet. Unfold him and put him on the bed. Turn it on its side. Raise his legs up on the bed. Lay it on your back.

Baby on back

Those places that hang down should be supported. If the head is on a pillow, then a towel roll should be placed under the neck. To raise your head, you can put two additional pillows under it in the shape of the letter A. Place a roller under your knees, an angle of 120 degrees. Then the tension is removed from the lower back. Shoulders slightly forward. Also give support under the feet.

It is necessary to have 6 pillows for a bedridden patient. Of these, two are the same for an elevated position of the head.

To slightly change the position, you can place a rolled towel under one side. This is done in order to slightly shift the center of gravity. When placing a roller, you should press the mattress, and not lift the child. If the hips fall apart to the sides, you can bring them to the level of the width of the shoulders with a scarf from the sheet. In this case, the ends of the sheet must be fastened together. You can also achieve this position with the help of an elastic bandage. Bandage "eight".

If the hips fall apart to the sides, you can bring them to the level of the width of the shoulders with a scarf from the sheet. In this case, the ends of the sheet must be fastened together. You can also achieve this position with the help of an elastic bandage. Bandage "eight".

Baby on the side

The position on the side is unstable. Pull the lower arm forward. You need to put your head in such a way that your nose does not stick into the pillow, i.e. put on the edge of the pillow. Straighten the lower leg, and bend the upper one at the knee and place a pillow under it. Give support to your back. Roll up two towels with a roller, wring out the mattress and lay in shape. Under the arm that was on top, also put a support.

If it is possible to raise the top of the bed, do not raise it more than 5 degrees.

To slightly change the position of the body, the shoulder that turned out to be on top must be taken back.

Tummy time

Place a pillow under your stomach so that it reaches your shoulders. Thus, we transfer the weight to the legs. Lay your head on the pillow as if lying on your side. Place a roller under the feet.

Thus, we transfer the weight to the legs. Lay your head on the pillow as if lying on your side. Place a roller under the feet.

Place the child on mats (floor)

Bring the chair with the child as close as possible to the place of laying out on the floor and let the chair go. Fix the brake.

Unfasten all reinforcing straps, raise the footrests and inform the child about what to do and ask for help. Raise the child from the chair, let him lean on his feet. Holding the child, stand on one knee, give the child support on the knee. Get on your knees and put the child on the floor. Depending on the position, give the child support with pillows.

How to pick up a child from the floor?

Sit on your knees next to your child. Turn him on his side, holding him from behind by the shoulders, sit him on his ass and pull him towards you. Put one foot on your knee. Pressing the child to yourself, put him on your knee. Group it as much as possible. Stand up on feet.