How to help your child deal with grief

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

How to help your child after the death of a parent

The information in this article explains how to help your child after the death of a parent.

back to top of pageUnderstanding a child's grief

For any child, the death of a parent is the hardest test. No matter how old your child is, you may want to protect him from the sadness and confusion that you are experiencing. Children, as well as adults, may need help in dealing with loss and adjusting to life after it. Remember that how a child experiences grief depends on their age, understanding of death, and the behavior of others.

Grief in young children

Young children express their grief differently than adults. After the death of a parent, they may have short and strong emotional outbursts. In addition, they may experience physical reactions, such as pain in the body or changes in sleep patterns. Some children may express grief through changes in their behavior. They may have difficulty completing daily tasks or behave in ways they have never behaved before. They may grieve for short periods of time with breaks in between. For example, a child may cry or appear sad, and shortly thereafter ask to go for a walk or start playing. Other children may not show any signs of sadness or grief.

Adolescents experience grief

While younger children may not fully understand death, adolescents have a more mature understanding of it. Adolescents are at a stage in their lives when their personality, way of thinking and emotions are being formed. After the death of a parent, they can experience a wide range of emotions. Some may feel that their place in the family has changed and take on adult responsibilities. Adolescents may need privacy to grieve. Let your child know that they can talk to you and ask for support.

Some may feel that their place in the family has changed and take on adult responsibilities. Adolescents may need privacy to grieve. Let your child know that they can talk to you and ask for support.

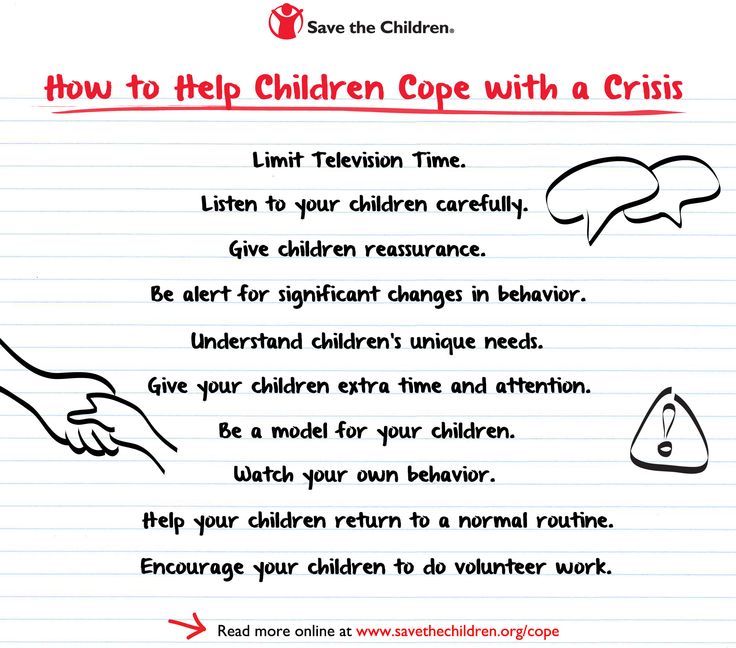

How to help your child

It may be difficult for you to help your child because you yourself are experiencing loss. If you are having trouble communicating with your child, ask for support and help from a family member, friend, social worker, psychologist, or religious or spiritual guide.

Here are some ways you can help your child cope with loss.

Share your own thoughts and feelings

It is natural not to cry in front of your child, but expressing your emotions can serve as an example for your child to cope with difficulties. Share your own feelings about the loss of a loved one. By telling your child how you feel, you will help your child express his feelings as well. If your family holds any religious or spiritual beliefs, it may help to mention your faith in the conversation.

Talk about death directly

When talking about death, avoid phrases such as "gone" or "left." This can mislead the child and make them think that their parent will soon wake up or return. Honesty and directness will help your child understand what happened and learn how to deal with grief. Some families use religious or spiritual beliefs to help the child understand that the parent is not physically present. If you think this might be helpful, ask a religious or spiritual guide for help.

Honor the memory of the deceased

Rituals to honor a loved one can have a calming effect on you and your child. By maintaining old family traditions or creating new ones, you and your family can keep in touch with your loved one. In different cultures and religions, there are rituals to honor someone's memory. Some families have their own rituals, such as getting together and preparing a special meal, planting a garden, visiting favorite places, or celebrating birthdays. Whatever you choose, remember that there is no right or wrong way to honor a loved one. Try to do what will be most comfortable for your family.

Whatever you choose, remember that there is no right or wrong way to honor a loved one. Try to do what will be most comfortable for your family.

Funeral participation

Whether your child attends a funeral or a farewell ceremony is a decision between you and your child. The opportunity to be present at the funeral will allow the child to experience grief with his family. If your child is attending a funeral, make sure they know what to expect beforehand. You may also want to consider having your child participate in the ceremony. The child can write a letter or draw something and put it in the coffin. He can also make a collage with photos of the parent for the funeral.

At the funeral, always remember the child's feelings and check his health. You may want to ask someone your child trusts to occasionally go out with your child for breaks. If the child wants to leave the room, let him do it. After the funeral or farewell ceremony, the child may have new questions about death.

Resources for you and your family

MSK resources

Support is available for you and your family, no matter where you are in the world. Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) offers a range of resources for grieving families and their friends. You can learn more about these resources at www.mskcc.org/experience/caregivers-support/support-grieving-family-friends

Talking with Children About Cancer

Talking about Cancer with Children is a program designed to support parents undergoing cancer treatment in raising their children and adolescents. Our social workers offer family support groups, individual and group counseling, access to resources, and guidance for professionals including school social workers, school psychologists, counselors, teachers, and other staff. For more information, visit www.mskcc.org/experience/patient-support/counseling/talking-with-children

Bereavement Program

646-888-4889

MSK offers services through the Bereavement Program to help bereaved family members and friends. People who have lost a loved one to cancer may find it helpful to talk to other grieving people. The Departments of Social Work, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Sciences offer support groups and educational programs for people who have lost a loved one to cancer. Services include short courses of individual counseling, resources for bereaved children, adult groups, and access to local resources.

People who have lost a loved one to cancer may find it helpful to talk to other grieving people. The Departments of Social Work, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Sciences offer support groups and educational programs for people who have lost a loved one to cancer. Services include short courses of individual counseling, resources for bereaved children, adult groups, and access to local resources.

For more information or to join a bereavement support group, call Social Work at 646-888-4889.

MSK Counseling Center

646-888-0200

Some bereaved families find they have benefited from expert advice. Our psychiatrists and psychologists work at the bereavement clinic, where they provide counseling and support for individuals, couples and families, and can prescribe medications to help manage depression.

Spiritual support

212-639-5982

Our chaplains are ready to listen and support family members, pray, reach out to local clergy or religious groups, simply offer comfort and extend a spiritual helping hand. Any person can apply for spiritual support, regardless of their formal religious affiliation.

Any person can apply for spiritual support, regardless of their formal religious affiliation.

Additional resources

Books, educational resources and local support programs are available for bereaved parents and children. For more information about these programs, call your social worker or visit www.mskcc.org/experience/patient-support/counseling/talking-with-children/resources

Useful websites

The Dougy Center: national center for children and families in grief

www.dougy.org

The Dougy Center provides support for grieving children, teens, young adults and families. The Center provides online resources and programs to support and assist families in grief.

Red Door Community

212-647-9700

www.reddoorcommunity.org

Provides meeting places for people living with cancer and their family and friends. Enables people to meet each other to build systems of mutual support. Provides free assistance and organizes communication groups, lectures, seminars and social events. The Red Door Community used to be called Gilda's Club.

The Red Door Community used to be called Gilda's Club.

Useful literature

Books for adults on how to help children and adolescents deal with grief

Guiding Your Child Through Grief

By James P. Emswiler

The Grieving Child: A Parent's Guide

By Helen Fitzgerald

Helping Children Cope with the Loss of a Loved One: A Guide for Grown Ups

By William C. Kroen

How Do We Tell the Children? A Step-by-Step Guide for Helping Children Two to Teen Cope When Someone Dies

By Dan Schaefer and Christine Lyons

Preparing Your Children for Goodbye: A Guidebook for Dying Parents

Author: Lori Hedderman

Take My Hand: Guiding Your Child Through Grief

Author: Sharon Marshall

Talking about Death: A Dialogue between Parent and Child

By Earl A. Grollman

Books for children about death and grief

Always by My Side (Always next to me)

For children aged 4 to 8

Author: Susan Kerner

Everett Anderson's Goodbye

For children aged 5 to 8

Author: Lucille Clifton

Gentle Willow: A Story for Children about Dying

For children aged 4 to 8

By Joyce C. Mills

Mills

The Fall of Freddie the Leaf

For children over 4 years of age

By Leo Buscaglia

The Goodbye Book

For children aged 3 to 6

Author: Todd Parr

Lifetimes: A Beautiful Way to Explain Death to Children

For children aged 5+

Author: Bryan Mellonie

The Memory Box: A Book about Grief

For children aged 4 to 9years

Author: Joanna Rowland

I Miss You: A First Look at Death

For children aged 4 to 8

By Pat Thomas and Leslie Harker

The Next Place (Better world

For children aged 5+

By Warren Hanson

Sad Isn't Bad: A Good-Grief Guidebook for Kids Dealing with Loss

For children aged 6 to 9

Author: Michelene Mundy

Samantha Jane's Missing Smile: A Story About Coping with the Loss of a Parent

For children aged 5 to 8

By Julie Kaplow and Donna Pincus

Saying Goodbye to Daddy

For children aged 4+

Author: Judith Vigna

Tear Soup: A Recipe for Healing After Loss

For children aged 8+

Author: Pat Schwiebert

What on Earth Do You Do When Someone Dies? (What do you do when someone dies?)

For children aged 5 to 10

Author: Trevor Romain

When Dinosaurs Die: A Guide to Understanding Death

For children aged 4 to 7

Posted by Laurie Kransy Brown and Marc Brown

Where Are You? A Child's Book about Loss (Where are you? Children's book about loss)

For children aged 4 to 8

Author: Laura Olivieri

Books for children with tasks for understanding death and dealing with grief

Help Me Say Goodbye: Activities for Helping Kids Cope When a Special Person Dies

For children aged 5 to 8

By Janis Silverman

When Someone Very Special Dies: Children Can Learn to Cope with Grief

For children aged 9 to 12

By Marge Heegaard

How to help a grieving child — Pro Palliative

To tell or not to tell a child about the death of a loved one? It often seems to people that it is better to protect the baby from difficult experiences, especially when it comes to parents. In fact, the decision to hide the truth from the child is wrong and, moreover, dangerous. About why - in an excerpt from the book of the publishing house "Nikeya" "A man died. What to do and how to survive?"

In fact, the decision to hide the truth from the child is wrong and, moreover, dangerous. About why - in an excerpt from the book of the publishing house "Nikeya" "A man died. What to do and how to survive?"

How to inform a child about tragic news

Children under six years of age form their life position, their attitude towards the world and other people. The child does not understand where mom (or dad) has gone, why everyone around is whispering about something and pitying him, although everything seems to be all right with him. Children are very sensitive to change. They see that “something is wrong” with adults, their mother is not around, something unintelligible answers his questions about her (she left, got sick).

The unknown causes fear . A child in such a situation can make two diametrically opposite decisions: I am bad, so my mother left me, I am not worthy of life (pleasure, joy) or my mother is bad, because she left me, and since the closest person did this to me, it means you can’t trust nobody.

Between these poles there are a thousand options for decisions that form a negative attitude towards oneself and the world, low self-esteem, hatred, anger, resentment. Therefore, no matter how painful it is, it is necessary to inform the child about the death of a loved one. And you need to do it right away.

If this difficult conversation is postponed until later (“I’ll tell you after the funeral, after the commemoration, after the mourning…”), a belated message can give rise to resentment against the remaining relatives (“They don’t trust me, otherwise they would have told me right away”), anger (“ How could dad hide it!”), distrust (“Since my close people didn’t tell me about it, it means that everyone around is deceivers and you can’t trust anyone”).

Who should tell the child the sad news? Of course, the closest of the remaining relatives, the one whom the baby trusts the most, with whom he can share his grief. The more faith and support he finds in this person, the better his adaptation to a new life situation will be.

Choose a place where you will not be disturbed, make sure you have enough time to talk. When speaking with the baby, it is very important to establish tactile contact (put him on your lap, hug, caress). Tell the truth. No matter how hard it is for you, do not use allegorical expressions. Say "dead", not "forever asleep" or "gone".

Children understand everything literally. Your words can provoke a fear of sleep (if I fall asleep, it means I will die), a fear of losing a loved one (my mother went to the store - she may not return either).

If the death was caused by an illness the child knew about, start there. If this is an accident, tell how it happened, perhaps starting from the moment when the child parted with the deceased: “You saw dad go to work in the morning ...” It’s hard for you at this moment too, but for the sake of the child you need to muster up courage. Watch his reactions, react to his words and feelings.

Children of three to six years old already know something about death, but, having a "magic" imagination, a child at this age believes that nothing like this can happen to him or his relatives.

It is necessary to talk to him about the grief that happened very tactfully, calmly, in an accessible form. It is very important to immediately explain all aspects of death that may cause fear in the child.

If death occurred as a result of illness , explain that not all illnesses lead to death, so that later, when sick, the child is not afraid to die: “Grandma was very sick, and the doctors could not cure her. Let's remember, you were sick last month and recovered. And I was sick recently, remember? And got better too. Yes, there are diseases for which there is no cure yet, but you can grow up, become a doctor and find a cure for the most dangerous disease.

If an accident occurs , explain the death without blaming anyone. The death of a loved one makes the child feel insecure, and he may ask: “Are you going to die too? And will I die? It’s better to answer honestly: “Yes, sometime in the future it will happen,” and only then reassure that people usually live long. If the child is frightened and cries, in no case should you give up your words and turn them into a joke. It is better to sit next to you, hug, let you cry and then help you return your thoughts to the life that goes on.

If the child is frightened and cries, in no case should you give up your words and turn them into a joke. It is better to sit next to you, hug, let you cry and then help you return your thoughts to the life that goes on.

Support for loved ones after the death of a relative: the German experience When should you talk to a person who has experienced the death of a loved one, and when should you leave it alone? Why can a grieving person be thrown from laughter to tears? How else can grief manifest itself?

It is very important to prevent feelings of guilt : “It's not your fault that your mother died. No matter how you behaved, it could not affect this situation. So let's talk about how we can live on." It is also appropriate here to let the child understand that he should reconsider his relationship with other relatives, see them as a source of support: “You always trusted your secrets only to your mother. I can't replace her in this. But I really want you to know that you can tell me about any of your difficulties and I will help you.”

I can't replace her in this. But I really want you to know that you can tell me about any of your difficulties and I will help you.”

In such a conversation, no matter how painful it is, the adult must accept any child's emotions that have arisen in connection with the death of a loved one. If this is sadness, it needs to be shared (“I am also sad because my grandmother is no longer with us. Let's look at the photos and remember what she was like”). If anger, let it vent (“I’d be terribly mad too that my dad died. Who are you mad at? It’s not dad’s fault. Will your anger help what happened? Let’s talk about dad better. What would did you want to tell him now? What would he say to you in response?").

If the child is too young and has little vocabulary, you can invite him to draw his feelings. For example, fear can be black, sadness blue, resentment green, anger purple.

The main thing is that the child must understand that he is not alone and has the right to freely express his feelings.

Unlived feelings of grief in a child are the basis for psychosomatic illnesses at an older age.

Do not tell the child what he should or should not feel and how he should or should not express his feelings (“Don’t cry, mom wouldn’t like it”; “Poor orphan, now you will feel very bad”; “Grandfather died, and you play as if nothing had happened. How do you not ashamed!"). Saying such things, we "program" the child to suppress true feelings. He may decide for himself that only desirable behavior can be demonstrated to others. Such a decision can lead to emotional coldness in adulthood.

Also it is dangerous to burden a child with your emotions . The tantrums of relatives, their withdrawal into themselves can scare.

It is impossible to “program” the future life of the family without joy and happiness (“Your sister has died, now we will never be happy”), as well as voluntarily or involuntarily use the image of the deceased to form in the child the desired behavior for adults (“Don’t shawl, mother now he looks at you from “out there” and gets upset”; “Don’t cry, dad always taught you to be a real man, he wouldn’t like it”). The child should not only hear, but also feel that next to him is a person who shares his grief.

The child should not only hear, but also feel that next to him is a person who shares his grief.

Photo: Arleen Wiese / Unsplash

You don't need to hide your emotions from your child, on the contrary, you can and should talk about them too. (“I also miss my mother very much. Let's talk about her”; “I am crying because I feel very bad. I am thinking now that my father has died. But I will not always be sad, and you are not to blame for my sadness. Grief passes sooner or later.”) At this moment it is very important to orient the child to activity, to explain how our deeds on earth can help the departed.

If the child is familiar with the basics of Christianity, it is easier, because he has already heard about the soul and what happens to it after death. If not, tell the kid in an accessible language that when a person dies, the soul remains, and we can help it with our prayer and good deeds. At this time, the child can realize that there is eternal life, that death is not the end, that the soul of a person is capable of experiencing joy and sadness even after death. This understanding reduces the fear of death in children. When talking about death from a religious point of view, it is important not to make the mistake of creating the image of a “terrible God” (“God took my mother, now she is better there than here”). The child may have a fear that he, too, will be “taken away”. The fact that “there” is better is also incomprehensible to children (“If “there” is better, then why is everyone crying? And if death is better than life, then why live?”).

This understanding reduces the fear of death in children. When talking about death from a religious point of view, it is important not to make the mistake of creating the image of a “terrible God” (“God took my mother, now she is better there than here”). The child may have a fear that he, too, will be “taken away”. The fact that “there” is better is also incomprehensible to children (“If “there” is better, then why is everyone crying? And if death is better than life, then why live?”).

The death they are waiting for Bishop Panteleimon (Shatov) - about his own experience of experiencing the death of a loved one, the Christian attitude to dying and the consolation of a believer

Having told the sad news, do not leave the child alone with his feelings. Let him cry or talk. Then ask for help with the upcoming chores. Of course, he will not be able to become a full-fledged assistant. But, excluded from the general process of preparing the funeral, he will feel abandoned, which will only increase the suffering. Therefore, it is necessary to come up with a feasible business for the child so that he remains in contact with loved ones.

Therefore, it is necessary to come up with a feasible business for the child so that he remains in contact with loved ones.

It's good if parents, despite their own worries, find the strength to take care of the child as usual: feed, put to bed and even, perhaps, play. So the baby will understand that life goes on.

If you are unable to talk to your child about the death of a loved one, contact mental health services (in person or by phone).

Whether to take children to the funeral

Participation in the funeral helps the child to recognize the reality of the loss, to realize that the deceased will not return. It is not uncommon for children to learn basic concepts about death during funerals and then use this knowledge to explore the issue of their own death.

In addition, without goodbye, the child's relationship with the deceased may remain incomplete, which often leads to the emergence of various fears.

So, after the death of her little brother, one girl was afraid to be at home alone, she turned on the light everywhere. In the conversation, it turned out that she was not taken to the funeral and now she is afraid to stumble upon his corpse in the apartment.

In the conversation, it turned out that she was not taken to the funeral and now she is afraid to stumble upon his corpse in the apartment.

Photo: Simon Wijers / Unsplash

After the mother told her daughter that her brother had been buried, the girl calmed down and her fears disappeared.

It is believed that children from the age of two and a half are able to understand the idea of farewell . However, it should be understood that the “last farewell” will fulfill its positive function only if the child is internally ready for such a ceremony. If he does not want to go to the funeral, in no case should he be forced or reproached. It is better to ask him to talk about his feelings and clarify possible misconceptions and fears.

On the eve of the funeral, talk to the child and tell him in detail what will happen. Be sure to warn that people may cry and even scream at the funeral, and this is normal. Your explanations will save the baby from possible traumatic surprises and dispel fears.

Be prepared to answer children's questions. For example, what does the coffin look like from the inside, is it scary to lie in the ground, is it cold below, that the deceased will eat there, etc. Explain to the baby that the deceased can no longer breathe, walk, talk or eat. If questions make parents feel uncomfortable, the child will notice and stop asking. So say in advance that you cannot know everything about death. Not knowing all the answers is okay. Children may well accept that adults also have difficulty understanding certain things.

Pay attention to what other adults tell your child . Their advice may conflict with yours. For example, one of the adults may say: “Be strong, don’t cry,” while you said that crying is normal, this indicates love for the deceased. It is necessary to come to the aid of a confused child in time, to try to explain why adults feel and behave differently.

Invite the child to say goodbye to the deceased in a special way, such as putting a memorial gift in the coffin: a drawing, a letter, or a flower. It is also helpful to find an adult who can be with the young children during the funeral. They may lose interest in what is happening after a short time, and then someone will need to leave the ceremony with them. It makes sense to tell the children themselves that they don't have to stay at the funeral if they don't want to.

It is also helpful to find an adult who can be with the young children during the funeral. They may lose interest in what is happening after a short time, and then someone will need to leave the ceremony with them. It makes sense to tell the children themselves that they don't have to stay at the funeral if they don't want to.

After the ceremony, children can play the funeral ritual or pretend to be sick or dying. This is normal, as children become aware of and assimilate their new experience.

Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh:

A child can get acquainted with death in an ugly way, and this will cripple him, or, on the contrary, sensibly, calmly, as the following example will show (it is taken from life, this is not a parable). A deeply beloved grandmother died after a long and difficult illness. They called me, and when I arrived, I found that the children had been taken away. The parents answered my question: “We couldn’t allow the children to stay in the same house with the deceased. ” - "But why?" “They know what death is.” “And what do they know about death?” I asked. "The other day they found a little rabbit in the garden, which was picked up by cats, so they saw what death is." I said that if children have such a picture of death, they are doomed to carry a feeling of horror through their whole lives. At every mention of death, at every funeral, every coffin in this wooden box will have an unspeakable horror for them... After a long argument, after parents told me that children would inevitably get mentally disturbed if they were allowed to see their grandmother and that it will be my responsibility, I brought the children. Their first question was, “So what happened to grandma?” I told them: “You have heard many times how she wanted to go to the Kingdom of God to her grandfather, where he went before her. That's what happened." "So she's happy?" one of the children asked. I said yes. And then we entered the room where the grandmother lay. There was an amazing silence.

” - "But why?" “They know what death is.” “And what do they know about death?” I asked. "The other day they found a little rabbit in the garden, which was picked up by cats, so they saw what death is." I said that if children have such a picture of death, they are doomed to carry a feeling of horror through their whole lives. At every mention of death, at every funeral, every coffin in this wooden box will have an unspeakable horror for them... After a long argument, after parents told me that children would inevitably get mentally disturbed if they were allowed to see their grandmother and that it will be my responsibility, I brought the children. Their first question was, “So what happened to grandma?” I told them: “You have heard many times how she wanted to go to the Kingdom of God to her grandfather, where he went before her. That's what happened." "So she's happy?" one of the children asked. I said yes. And then we entered the room where the grandmother lay. There was an amazing silence. The elderly woman, whose face had been distorted by suffering for many years, lay in perfect peace and quiet. One of the children said, "So that's what death is!" And another added: “How wonderful!” Here are two expressions of the same experience. Will we let children experience death as a bunny torn apart by cats in the garden, or will we show them the peace and beauty of death?

The elderly woman, whose face had been distorted by suffering for many years, lay in perfect peace and quiet. One of the children said, "So that's what death is!" And another added: “How wonderful!” Here are two expressions of the same experience. Will we let children experience death as a bunny torn apart by cats in the garden, or will we show them the peace and beauty of death?

From the book of Metropolitan Anthony of Surozh Life and Eternity. 15 Conversations about Death and Suffering”

Psychological features of childhood grief

Children's experience of the loss of a loved one does not always occur in a clear and understandable form for others. For example, a child may not openly express his pain (not cry or say how hard it is for him), but his behavior and reactions to things around him change dramatically.

In general, children's grief is characterized by such features as delay, secrecy, surprise, unevenness.

Children tend to express grief occasionally, in waves. A surge of emotions and a stream of tears are replaced by relative calm and even moments of fun. At the same time, an acute reaction to death is sometimes delayed for months. In some cases, real awareness of the loss comes under the influence of some significant event, for example, another loss.

In general, a child's grief, just like an adult's, goes through a series of stages. The initial - shock reaction - can have different manifestations: silent withdrawal into oneself, inactivity and lethargy, automatic movements, fussy activity. For some time, the child is simply unable to believe that he will never see his loved one again. Therefore, after this, he tries to find him, entering the search stage. Sometimes children experience this search as a game of hide-and-seek, visually imagining how the deceased enters the door. When the child realizes the impossibility of returning the deceased, despair sets in. He begins to cry, scream, reject others.

He begins to cry, scream, reject others.

The stage of anger is expressed in the fact that the child is angry with the parent who left him, or with God who "took" the father or mother. Kids can start to break toys, throw tantrums, teenagers stop communicating with their mother, beat their younger brother for no reason, and be rude to teachers. Anxiety and the accompanying guilt lead to depression.

Photo: Annie Spratt / Unsplash

In addition, a child may worry about various everyday problems: who will accompany him to school, who will help with the lessons? A resource has already been laid in these questions: the child thinks about how he will live after the loss. How much he will be able to adapt to new conditions depends largely on adults. Adults should help the child to talk about their experiences and fears. In some cases, a visit to a psychologist may be required. For example, if a child has irritability or physical overwork, sleep or nutrition disorders, enuresis, headaches and other pains.

How to help a family with grief and grief after a bereavement An excerpt from Justin Emery's The Truly Helpful Guide to Children's Palliative Care for Doctors and Nurses Worldwide about how children experience grief and whether they can attend funerals

Childhood grief can take on extreme forms. Adults should be alerted by the complete absence of emotions, too long or unusual mourning. Reasons to seek help from a psychologist: a sharp decline in school performance, persistent refusal to attend school, persistent disobedience or aggression, unexplained outbursts of anger, worsening mood, persistent anxiety or phobias, frequent panic attacks, persistent nightmares, severe difficulty falling asleep and other sleep disorders, inability to cope with daily activities. Situations when a child avoids talking and even mentioning the deceased or, on the contrary, constantly talks about the desire to unite with the deceased, should also not be ignored. The measure of children's grief primarily depends on the degree of kinship with the deceased. The most severe loss of parents, brothers and sisters. Very often, the feeling of abandonment and longing for the deceased parent persist throughout life, which cannot but affect the development of the individual.

The measure of children's grief primarily depends on the degree of kinship with the deceased. The most severe loss of parents, brothers and sisters. Very often, the feeling of abandonment and longing for the deceased parent persist throughout life, which cannot but affect the development of the individual.

In the event of the death of a brother or sister, the degree of grief depends on the age of the deceased and the relationship with him.

At the age of two, a child cannot yet realize the fact of the death of a parent or close relative, but notices his absence and changes in the behavior of adults. Often, babies become irritable, more noisy and restless.

Two-year-old children , as a rule, start calling and looking for the deceased, waiting for his return. It may take them a long time to realize that the person will never come. At this age, children need a secure, stable environment, regular eating and sleeping patterns, close attention, and love.

Children from three to five years old still do not understand what death is, some perceive it as a dream and hope that father (mother) will wake up soon. Someone may begin to be afraid of the dark, experience sadness, anger, anxiety. Headaches, skin rashes, mood swings, a return to past habits (thumb sucking, etc.) may occur. At this age, the child may have the idea that his words and actions caused the death of an adult. Adults need to dispel these fantasies by explaining what actually happened and why.

At primary school age (six to eight years old), children still have difficulty understanding the reality of death. Their behavior at school and at home changes: for example, they may show anger towards teachers or stop communicating with classmates. If you prepare a child for possible questions about the death of a loved one from other people, without going into details, then he will not have to avoid contacts and communication on these topics.

Nine to twelve years is characterized by a desire for independence, and the experience of loss leads to a feeling of helplessness. Children may hide their emotions, study poorly, fight at school, or rebel against the authority of their elders. Often they try to take on the role of a deceased adult - mother or father. This behavior should not be encouraged, but adults should still take into account that their family structure has changed and everyone will have to adapt to this.

It is impossible to ignore or suppress the desire of a teenager to support grieving loved ones, to help them, to share grief with them.

And, what is very important, no matter how old a child is, he must know that he has the right to be happy and enjoy life, that this does not offend or betray the memory of the deceased.

The situation when one of the children in the family dies has its own pitfalls. We all tend to idealize the deceased to some extent. Parents can unwittingly compare other children with him and thus awaken in them a sense of their own worthlessness. The other extreme is excessive custody of the remaining child. It is understandable that the loss of a child causes great concern for other children, but children's desire for independence should not be suppressed.

Parents can unwittingly compare other children with him and thus awaken in them a sense of their own worthlessness. The other extreme is excessive custody of the remaining child. It is understandable that the loss of a child causes great concern for other children, but children's desire for independence should not be suppressed.

Photo: Annie Spratt / Unsplash

Above all, attention, patience and compassion are required on the part of all adults. However, not every form of expression of sympathy is good for a child. Sometimes from the side of adults you can hear: "Poor thing, you are now left alone." Hearing such words, the child may feel even more alone and unhappy. Care should not be hypertrophied or intrusive, the most important thing is that it meets the real needs of the child.

It is important for a grieving child to feel positive emotions from adults - it is so important for children to feel significant, protected and loved during the period of mourning. It is especially important to maintain emotional and physical contact with the child, be attentive to his condition and desires, answer questions honestly, and be patient with the negative aspects of behavior.