How to help my autistic child communicate

Teaching nonverbal autistic children to talk

March 19, 2013

Still among our most popular advice posts, the following article was co-authored by Autism Speaks's first chief science officer, Geri Dawson, who is now director of the Duke University Center for Autism and Brain Development; and clinical psychologist Lauren Elder.

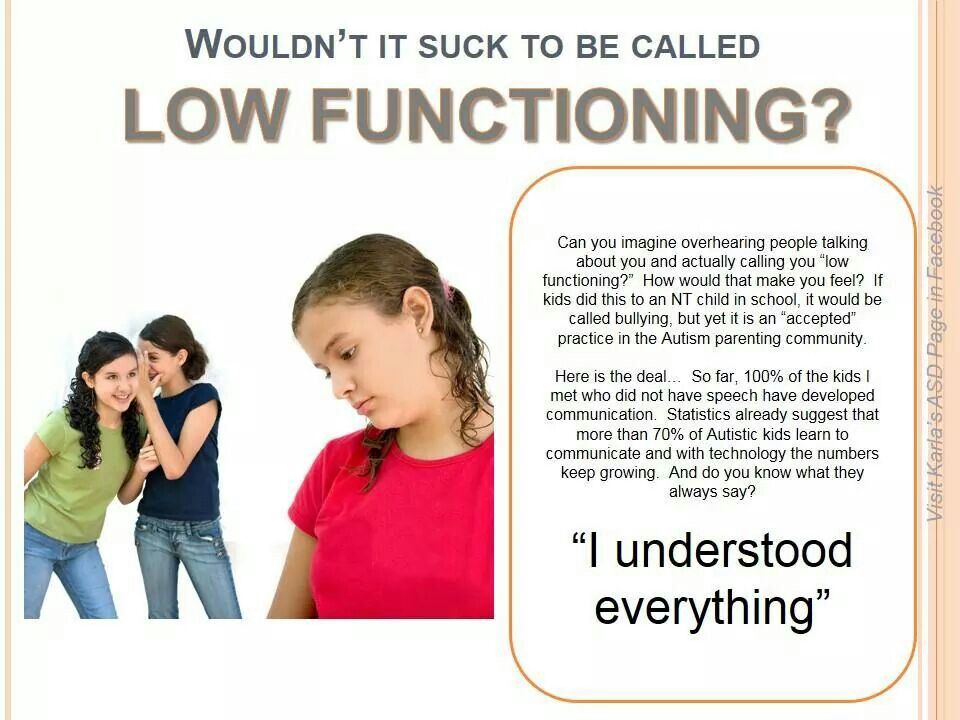

Researchers published the hopeful findings that, even after age 4, many nonverbal children with autism eventually develop language.

For good reason, families, teachers and others want to know how they can promote language development in nonverbal children or teenagers with autism. The good news is that research has produced a number of effective strategies.

But before we share our “top tips,” it’s important to remember that each person with autism is unique. Even with tremendous effort, a strategy that works well with one child or teenager may not work with another. And even though every person with autism can learn to communicate, it’s not always through spoken language. Nonverbal individuals with autism have much to contribute to society and can live fulfilling lives with the help of visual supports and assistive technologies.

Here are our top seven strategies for promoting language development in nonverbal children and adolescents with autism:

- Encourage play and social interaction. Children learn through play, and that includes learning language. Interactive play provides enjoyable opportunities for you and your child to communicate. Try a variety of games to find those your child enjoys. Also try playful activities that promote social interaction. Examples include singing, reciting nursery rhymes and gentle roughhousing. During your interactions, position yourself in front of your child and close to eye level – so it’s easier for your child to see and hear you.

- Imitate your child. Mimicking your child’s sounds and play behaviors will encourage more vocalizing and interaction.

It also encourages your child to copy you and take turns. Make sure you imitate how your child is playing – so long as it’s a positive behavior. For example, when your child rolls a car, you roll a car. If he or she crashes the car, you crash yours too. But don’t imitate throwing the car!

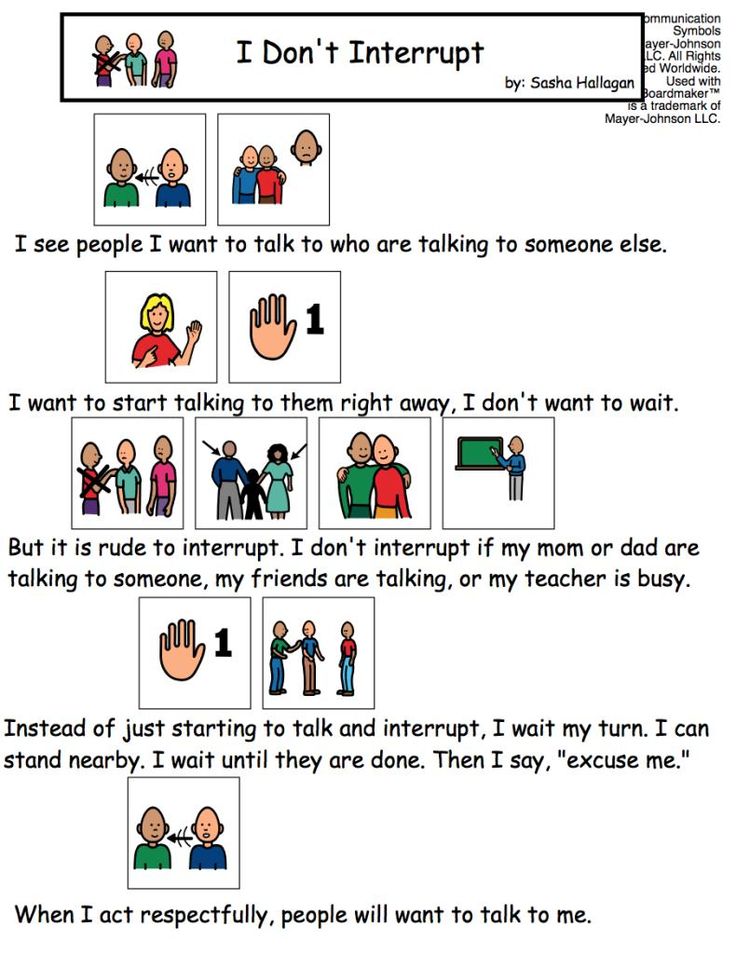

It also encourages your child to copy you and take turns. Make sure you imitate how your child is playing – so long as it’s a positive behavior. For example, when your child rolls a car, you roll a car. If he or she crashes the car, you crash yours too. But don’t imitate throwing the car! - Focus on nonverbal communication. Gestures and eye contact can build a foundation for language. Encourage your child by modeling and responding these behaviors. Exaggerate your gestures. Use both your body and your voice when communicating – for example, by extending your hand to point when you say “look” and nodding your head when you say “yes.” Use gestures that are easy for your child to imitate. Examples include clapping, opening hands, reaching out arms, etc. Respond to your child’s gestures: When she looks at or points to a toy, hand it to her or take the cue for you to play with it. Similarly, point to a toy you want before picking it up.

- Leave “space” for your child to talk.

It’s natural to feel the urge to fill in language when a child doesn’t immediately respond. But it’s so important to give your child lots of opportunities to communicate, even if he isn’t talking. When you ask a question or see that your child wants something, pause for several seconds while looking at him expectantly. Watch for any sound or body movement and respond promptly. The promptness of your response helps your child feel the power of communication.

It’s natural to feel the urge to fill in language when a child doesn’t immediately respond. But it’s so important to give your child lots of opportunities to communicate, even if he isn’t talking. When you ask a question or see that your child wants something, pause for several seconds while looking at him expectantly. Watch for any sound or body movement and respond promptly. The promptness of your response helps your child feel the power of communication. - Simplify your language. Doing so helps your child follow what you’re saying. It also makes it easier for her to imitate your speech. If your child is nonverbal, try speaking mostly in single words. (If she’s playing with a ball, you say “ball” or “roll.”) If your child is speaking single words, up the ante. Speak in short phrases, such as “roll ball” or “throw ball.” Keep following this “one-up” rule: Generally use phrases with one more word than your child is using.

- Follow your child’s interests.

Rather than interrupting your child’s focus, follow along with words. Using the one-up rule, narrate what your child is doing. If he’s playing with a shape sorter, you might say the word “in” when he puts a shape in its slot. You might say “shape” when he holds up the shape and “dump shapes” when he dumps them out to start over. By talking about what engages your child, you’ll help him learn the associated vocabulary.

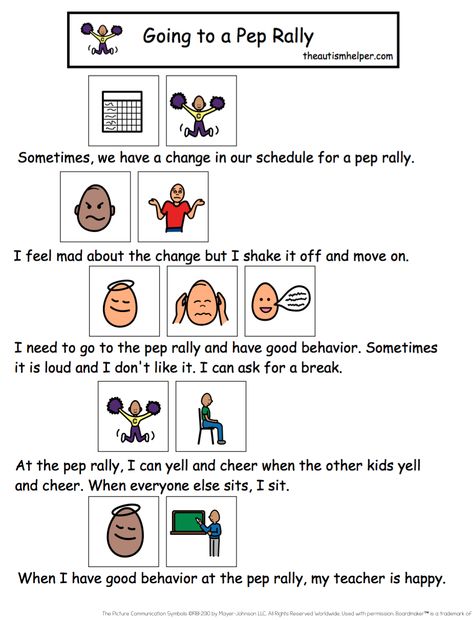

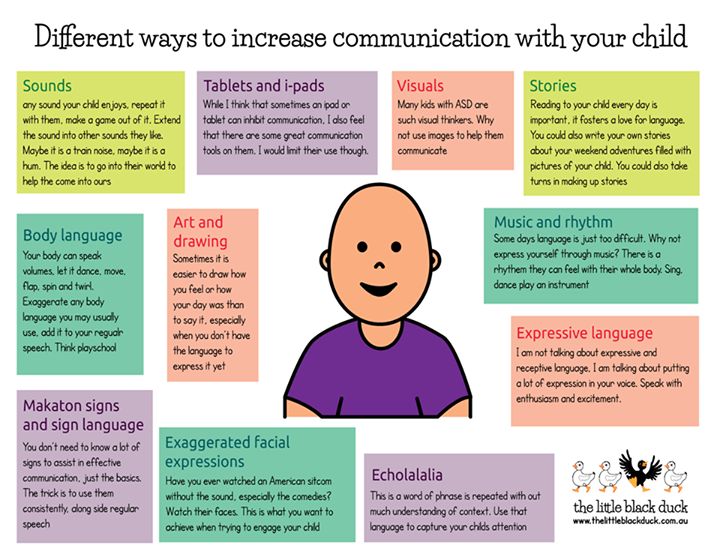

Rather than interrupting your child’s focus, follow along with words. Using the one-up rule, narrate what your child is doing. If he’s playing with a shape sorter, you might say the word “in” when he puts a shape in its slot. You might say “shape” when he holds up the shape and “dump shapes” when he dumps them out to start over. By talking about what engages your child, you’ll help him learn the associated vocabulary. - Consider assistive devices and visual supports. Assistive technologies and visual supports can do more than take the place of speech. They can foster its development. Examples include devices and apps with pictures that your child touches to produce words. On a simpler level, visual supports can include pictures and groups of pictures that your child can use to indicate requests and thoughts. For more guidance on using visual supports, see Autism Speaks ATN/AIR-P Visual Supports Tool Kit.

Your child’s therapists are uniquely qualified to help you select and use these and other strategies for encouraging language development. Tell the therapist about your successes as well as any difficulties you’re having. By working with your child’s intervention team, you can help provide the support your child needs to find his or her unique “voice.”

Tell the therapist about your successes as well as any difficulties you’re having. By working with your child’s intervention team, you can help provide the support your child needs to find his or her unique “voice.”

Blog

How to make the holidays more meaningful for yourself and your autistic loved ones

Blog

Giving Thanks: Autistic adult credits his family, friends and therapy for his good life

Expert Opinion

Tips for creating an autism-friendly Thanksgiving

Blog

In Our Own Words: Embracing empathy and individuality to overcome bullying

Blog

Expert Q&A: Dr. Ryan Adams shares tips and resources to end bullying

Blog

Catching up with Kaitlyn Y.

Blog

Expert Q&A: Supporting siblings of autistic children with aggressive behaviors

Podcast

Adulting on the Spectrum: Constructed language, job hunting and Pokémon

Helping Children With Autism Learn to Communicate

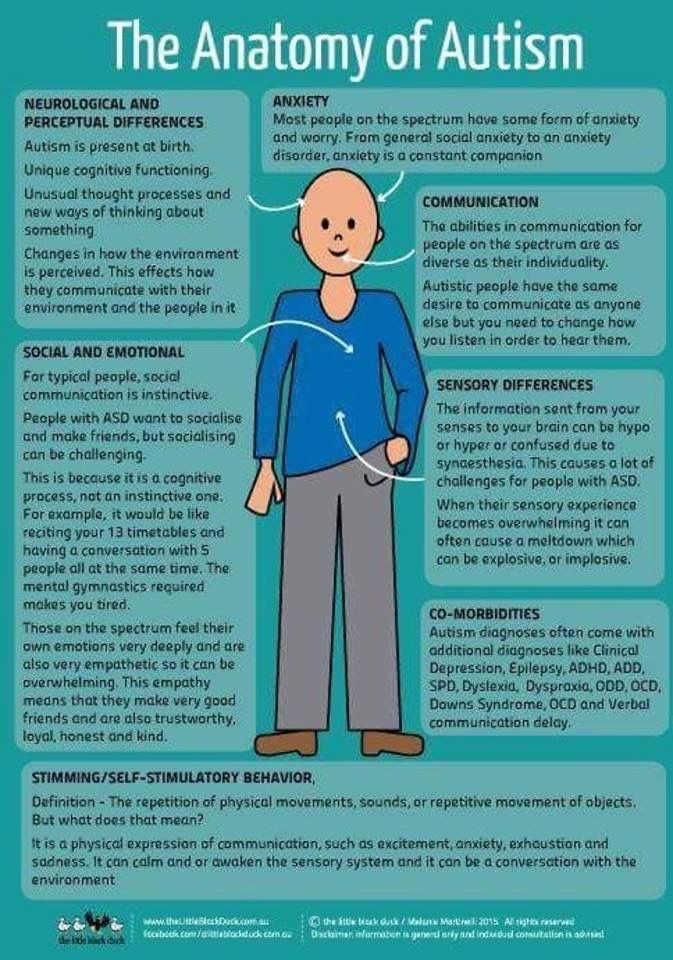

One of the most urgent goals in treating children on the autism spectrum is to help them develop communication skills. When children don’t have typically developing language skills, they may not have an effective way to convey their wants and needs. As a result, they are at risk of developing tantrums, aggression or self-injurious behaviors as a replacement. These behaviors are not only potentially harmful, they often aren’t understood.

That’s where functional communication training (FCT) comes in. FCT involves teaching an individual a reliable way of conveying information with language, signs, and/or images to achieve a desired end. It’s called “functional” because it doesn’t just teach kids to label an item (ie associating the word RED to a picture of an apple) but focuses on using words or signs to get something needed or desired — a food, a toy, an activity, a trip to the bathroom, a break from something.

FCT involves the use of positive reinforcement to teach children about language and communication, to increase their ability to interact effectively with others to get their needs met.

How functional communication training works

Stephanie Lee, PsyD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute, explains how a clinician implementing FCT works. She begins, Dr. Lee says, by identifying something the child is highly motivated to achieve — say, a favorite food, toy or activity. That will serve as the natural reward for using a sign or picture that represents that thing.

“So if a child really, really likes his Ninja Turtles or Thomas the Tank engine, or a child’s favorite, favorite thing to eat is Cheetos,” she says, “we would take that item and then teach the child either a sign or a picture that represents that item.”

Initially, the child is set up for what Dr. Lee calls “errorless learning,” in which the therapist guides the child to use the sign or picture and obtain the reward. This supported communication is repeated, each time resulting in the earned reward, until the child is able to succeed with less and less prompting from the therapist.

This supported communication is repeated, each time resulting in the earned reward, until the child is able to succeed with less and less prompting from the therapist.

“As we fade that prompting, the child becomes more and more independent in their communication,” says Dr. Lee.

Once kids are reliably using the word, sign or picture for that item when the item is present, the next step is for them to “generalize,” or use it outside the specific situation in which it’s been taught. For example, if a child is watching TV and wanting some chips, she might use the sign as a way to get those chips, Dr. Lee notes. That kind of spontaneous or sporadic use of the skill also needs to be reinforced across time. After a particular word or sign is being used consistently, new ones can be added to gradually build the child’s repertoire.

“Once the child has learned this system of communication — that the sign or the picture that they’re using needs to be received by someone else, in order for them to get their item — then slowly but surely we can teach a new sign or introduce a new picture,”explains Dr. Lee.

Lee.

Goals in FCT

How quickly children progress with FCT often depends on their functioning, or cognitive level. For children with more complex needs or more significant language impairment, many, many trials might be needed for them to gain a few signs or pictures. “They may end up with a small repertoire of functional communication,” Dr. Lee notes, “but it’s the repertoire that they need most — the foods that they like, using the bathroom, that type of thing. Children with less complex needs and whose level of functioning is higher might actually end up gaining just as much language — if not more — than their typically developing peers.”

Some kids will be able to speak in full sentences, using an assistive tech device. Others will acquire only single words. “With the latter we would be looking to determine the most appropriate goals for them,” notes Dr. Lee. The benefit would be weighed against the effort it would take to achieve it. It is important to remember that treatment is tailored to the specific needs and abilities of each child.

Functional communication training is often taught one-on-one with a clinician who is either a speech and language pathologist or a behavioral psychologist trained in applied behavior analysis (ABA). Parents have an important role in reinforcing the training, practicing what the child has learned, and using it in a variety of situations. When FCT is done at school, teachers would need to help kids practice the signs they’ve learned.

FCT and problem behaviors

Functional communication training was originally developed, in the 1980s, as a way to reduce the troubling behaviors associated with autism, including self-injury and aggression. The idea was that these behaviors result from an inability to communicate needs effectively.

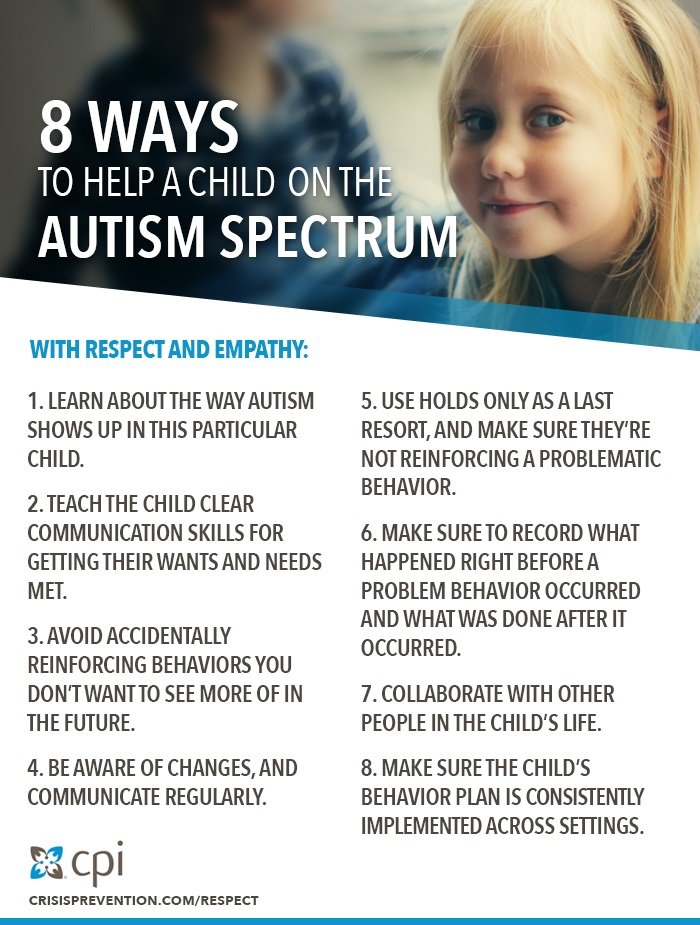

To use FCT to mitigate problem behavior, Dr. Lee explains, the starting point is to look at the function of those behaviors — what clinicians call a “functional assessment.” That requires close observation of the child. If a child is banging his head on the wall, or slapping himself, or hitting another child, what is the function of this behavior? “To get to the bottom of these behaviors we look at the antecedents and the consequences. What sets the stage for the behavior? When does it happen? When doesn’t it happen? Who does it happen with? What tends to happen afterwards?”

What sets the stage for the behavior? When does it happen? When doesn’t it happen? Who does it happen with? What tends to happen afterwards?”

If the catalyst for the problem behaviors seems to be something the child is unable to communicate, then teaching the child a more reliable way to communicate his needs can extinguish that behavior.

Dr. Lee stresses that FCT only works to reduce problem behavior if you can correctly assess the function of the behavior for that individual. “The type of behavior or typography — that’s the technical term — really varies based on the individual,” she explains. “And it can vary for one individual at different points. For instance, someone might start with self-injurious behavior and then become aggressive, if he finds that aggression is more efficient.”

Replacing self-injury with language

Self-injurious behavior — like all behavior — serves a function, usually one of these:

- To get attention

- To access a desired item or activity

- To escape an undesired task

- To serve a sensory need

When head hitting or face slapping results in a child getting attention, getting something she wants, getting out of something she doesn’t want to do, or escaping an uncomfortable situation, the behavior is accidentally being reinforced. FCT can help break these unhealthy behavioral patterns.

FCT can help break these unhealthy behavioral patterns.

Once children learn to ask for a break with a word, a sign or a picture, and get results quickly and efficiently, they are likely to choose the appropriate behavior rather than the self-injurious behavior.

Functional communication training can and has been applied to every age, from preschool to adulthood, but experts like to see it start as early as possible. “What we know about language development is that the earlier the intervention, the better,” notes Dr. Lee. “So the quicker we can get on these things and the quicker we can build the child’s communication repertoire the better off he is going to be.”

But Dr. Lee adds that she’s seen FCT work very effectively with adults who didn’t have this type of training earlier, and some gain skills quickly. “I’ve also seen adults who took a very long time to develop a very small repertoire of words,” she adds, “but that small repertoire was very, very important to them, and to the people around them in terms of better understanding what they’re needing and wanting. ”

”

How to communicate with a child with autism?

21.12.13

Recommendations to parents on the development of positive relations with a child

Source: Living well with autism

Use the declarative language

,9000 declarative statements allow you to share or divide the topics want, but do not require a verbal response from your child. This approach models for the child the natural language spoken by other children, which can increase the child's desire to communicate with you. Use declarative language to compliment, secret, surprise, comment, and share your emotions. nine0003- Share experiences and emotions: "I'm so hungry", "I'm not having fun at all", "Wow, look at this!", "I wonder if it will snow today?"

- Invite the child to do something with you: "Let's go to the playground", "Here come the soap bubbles!"

- Celebrate the child's victories: "Excellent!", "High five!", "We did it!"

- Encourage or offer solutions: "Can you do it!", "Let's take a break?"

- Reminisce about past experiences (use a photo album with photos of specific situations for this): "We had so much fun", "This trip is my favorite. " nine0003

" nine0003

- Describe actions (instead of instructions): "We'll put on our boots", "Run together, run so fast!".

The child does not have to respond to declarative statements in any way, but he may do so verbally or non-verbally. In my experience, declarative statements expand my child's social language skills, increase their willingness to cooperate and desire to communicate.

On the other hand, imperative statements and questions put pressure on the child - they require response communication from him, they tell him what to do, they force him to make a choice, they demand the right answer. nine0003

Examples of imperative phrases: How old are you? What is color? Say thank you". What do you want to play? Put on your boots.

Teachers almost always speak to students in imperative phrases. Such phrases are simple and allow you to achieve quick results. But unlike a declarative language, they do not model natural communication. Almost any imperative statement can be formulated as declarative if you get creative.

In some situations, imperative phrases are necessary, but it is necessary to reduce the proportion of imperative language in your speech. Imperative phrases should make up no more than 20% of your entire communication. nine0003

Model social communication

Use the forms of communication with your child that you would like to hear from him. If you want to hear "please", "thank you" and "sorry", then do not forget to say these words yourself in relation to your child.

Communication zone

Stand in close proximity to the child before speaking. Be at eye level (bend over, sit down, lift the child higher), no further than at arm's length, with the maximum level of contact. Do not try to get the child's attention from across the room! nine0003

Don't go beyond your child's abilities

Children with autism may be good in one area but delayed in other areas. For example, your child may find it very difficult to throw or even roll a ball, but they may enjoy jumping on an exercise ball.

A common mistake is overestimating the child's ability to complete simple tasks or take part in a game. Look for ways to make the task easier. When communicating with a child, rely on what he definitely knows how to do. nine0003

Do simple, short, everyday activities together, such as brushing your teeth together at the same time, or sealing and mailing letters. Modeling such actions by adults helps the child learn.

Then you will understand that it is time to move on to the next level. Make it fun.

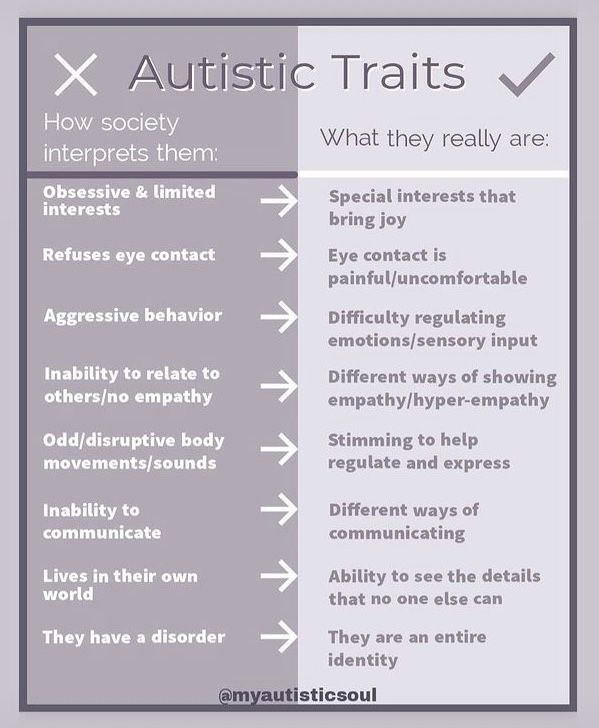

Respect eye contact features

Do not insist on eye contact with commands such as "Look at me" and do not praise for "Good look". Research shows that direct eye contact can be uncomfortable for some people with autism, and that it can cause anxiety. In my experience, natural, social eye contact develops over time as a child learns to pay attention to other people's faces while interacting. nine0003

Accompany your speech with non-verbal and alternative communication

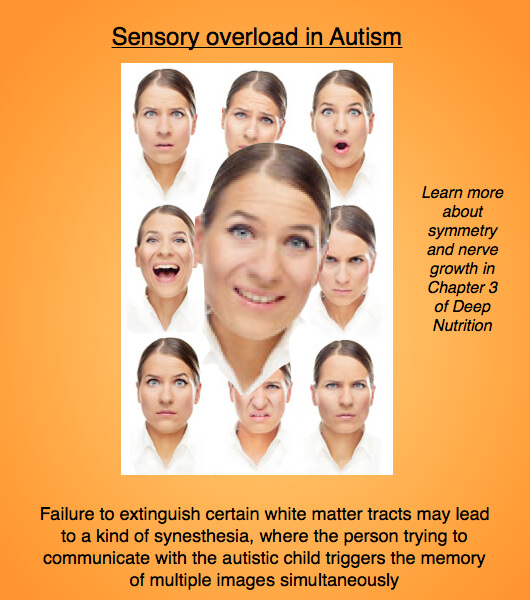

Many children with autism find it difficult to process other people's spoken language and may be constantly distracted by other stimuli from the outside world. When communicating with a child, do not just talk - use your whole body, including facial expressions, movements of your arms and legs.

When communicating with a child, do not just talk - use your whole body, including facial expressions, movements of your arms and legs.

Accompany your speech with photographs and drawings that reflect what you are talking about. Learn a few signs from sign language and accompany them with the appropriate words (this can be very helpful). nine0003

Try to be "numb" for a while and, as a game, communicate with your child exclusively non-verbally and through alternative means. Your child's reaction may surprise you!

Visual attention, pointing, and the theory of the mind

One of the classic symptoms of autism is that children do not point to objects to draw attention to them. It is believed that children with autism have problems with the theory of mind - it can be difficult for them to understand that you think differently than they do. nine0003

However, you can encourage the development of this skill. For example, if your face will show the information that the child needs, then you will teach the child to visually pay attention to other people's faces. To do this, make your face more cheerful and interesting for attention. Increase your facial expressions and gestures. Use makeup, a hat, or glasses to make your face an interesting subject for a child.

To do this, make your face more cheerful and interesting for attention. Increase your facial expressions and gestures. Use makeup, a hat, or glasses to make your face an interesting subject for a child.

It is hardly useful to constantly tell a child with autism that your experience and thoughts are desperate when the child does not have the skills to understand it. I saw my son begin to tell the teachers about his birthday party: “Do you remember…” To which the teachers replied: “No, I don’t remember, because I wasn’t there.” This only caused confusion in the son, and he stopped talking. Before the development of the theory of the mind, one could answer: “It must have been a lot of fun! I love birthday cake." Or: “Are you talking about your birthday? It must have been a lot of fun." And then wait for the child to continue sharing the experience. nine0003

Make your speech important

If you want to get a child's attention, you don't have to repeat his name all the time. Try to get attention with a gesture or a cough. Say his name once and then pat him on the shoulder. No need to repeat the name several times in a row, the child will simply learn to ignore it, including in situations where you need him to respond to the name.

Try to get attention with a gesture or a cough. Say his name once and then pat him on the shoulder. No need to repeat the name several times in a row, the child will simply learn to ignore it, including in situations where you need him to respond to the name.

Do not overload the child with too long phrases, let the length of the sentences in your speech correspond to the capabilities of your child. Perhaps a child can only take in a few words at a time! Do not "lisp", do not talk to the child like a baby, just simplify your speech. nine0003

Make your speech important by emphasizing key words in sentences with volume, pauses, intonation, emphasis, and more. The following rules are recommended when talking to a child with autism: speak less, emphasize key words, speak slowly and show what you mean with gestures or visual materials.

Parenting, Communication and Speech

How to communicate with an autistic person? 15 tips for every day

Five ways to show acceptance towards autistic children

1. Be patient. In fact, this applies to any children without exception. Children have the right to be with you in this world, they have the right to fully participate in this world, which will soon be theirs. Children in general, but especially children with special needs, can only learn proper social behavior, they can make noise in the library (but if they love books loudly, how can you be mad at them?), they can constantly fidget around you in airplane, they might burst into tears in line at the supermarket checkout because they saw that chocolate bar (maybe you need it too, you just learned how to express your desires in a socially acceptable way). Without a doubt, we all misbehaved at least occasionally (or often), and if we were lucky, then there were patient and understanding adults next to us, even if we ourselves lacked patience. nine0003

Be patient. In fact, this applies to any children without exception. Children have the right to be with you in this world, they have the right to fully participate in this world, which will soon be theirs. Children in general, but especially children with special needs, can only learn proper social behavior, they can make noise in the library (but if they love books loudly, how can you be mad at them?), they can constantly fidget around you in airplane, they might burst into tears in line at the supermarket checkout because they saw that chocolate bar (maybe you need it too, you just learned how to express your desires in a socially acceptable way). Without a doubt, we all misbehaved at least occasionally (or often), and if we were lucky, then there were patient and understanding adults next to us, even if we ourselves lacked patience. nine0003

2. Ask and listen. My son is speaking. This is our blessing, and this is what we have worked long and hard for. What he says is usually full of meaning (although sometimes this meaning is known only to himself) and an unusual way of looking at things. My son speaks slowly, extremely slowly, he often repeats parts of a sentence several times, he speaks in a quiet monotonous voice, practically without facial expressions, without gestures, without looking into his eyes. Stop, sit down to be at his level, listen to him, give him time to find his words, give him the opportunity to speak - he really has something to say. He taught me a lot, and I learned to trust him, even when I think he's making things up, like that pink concrete mixer, but he actually saw it at the construction site down the street. nine0003

My son speaks slowly, extremely slowly, he often repeats parts of a sentence several times, he speaks in a quiet monotonous voice, practically without facial expressions, without gestures, without looking into his eyes. Stop, sit down to be at his level, listen to him, give him time to find his words, give him the opportunity to speak - he really has something to say. He taught me a lot, and I learned to trust him, even when I think he's making things up, like that pink concrete mixer, but he actually saw it at the construction site down the street. nine0003

3. Discuss their interests with them. A quote from Temple Grandin recently made me think about children and their personal understanding of their autism: are we encouraging them to think too much about their differences from other people? While it seems to me important that we as adults show understanding for these children, they are not limited to their diagnoses, impairments, and neurological differences. It seems to me that this is the moment when "acceptance" becomes more important than "informing about the problem. " True acceptance means that you accept that something is part of your world and your life, but you don't have to think about it all the time. Many children on the autism spectrum have very surprising interests, or interests that only they can see something amazing in, these interests allow them to maintain peace of mind and peace of mind, and sometimes, with the right support and encouragement, they can become experts in the field. your interest and make it your career. Ask my daughter anything about condors and you'll have a very long (and very informative) conversation that I'm sure you'll enjoy just as much as she did. Join my son as he collects little pebbles in the park. This is soothing, and you will immediately establish a relationship with him that cannot be achieved with words alone. nine0003

" True acceptance means that you accept that something is part of your world and your life, but you don't have to think about it all the time. Many children on the autism spectrum have very surprising interests, or interests that only they can see something amazing in, these interests allow them to maintain peace of mind and peace of mind, and sometimes, with the right support and encouragement, they can become experts in the field. your interest and make it your career. Ask my daughter anything about condors and you'll have a very long (and very informative) conversation that I'm sure you'll enjoy just as much as she did. Join my son as he collects little pebbles in the park. This is soothing, and you will immediately establish a relationship with him that cannot be achieved with words alone. nine0003

4. Communicate with them and accept their communication with you. Most children on the autism spectrum have some form of communication problem, ranging from severe to subtle. If the child does not speak and does not have other means of communication, then you can observe his behavior, what he does, what gives him pleasure - communicate at this level or just be around without the usual communication, for many this is already a very big step . I don't have much experience with non-speaking children, but I know that behavior is communication, and if you are accepting of a child and comfortable in their presence, then this is also a form of communication that can be very useful for you. both. Children who can speak also have differences in communication, so we must be aware that when communicating with them, some stereotypical aspects of communication may be missing (for example, very often it is eye contact), in addition, they may interpret language differently ( see point 2). nine0003

If the child does not speak and does not have other means of communication, then you can observe his behavior, what he does, what gives him pleasure - communicate at this level or just be around without the usual communication, for many this is already a very big step . I don't have much experience with non-speaking children, but I know that behavior is communication, and if you are accepting of a child and comfortable in their presence, then this is also a form of communication that can be very useful for you. both. Children who can speak also have differences in communication, so we must be aware that when communicating with them, some stereotypical aspects of communication may be missing (for example, very often it is eye contact), in addition, they may interpret language differently ( see point 2). nine0003

5. Love them. Because what else do all children need if not love and acceptance? (Besides oxygen, food, water and a roof over your head, but you get my point).

Five ways to show acceptance towards autistic adults

1. Show respect. Whether a person has a visible disability or not, whether communication is difficult or not, everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. It seems to me that there is no point in explaining this point, but it does not prevent us all from thinking it over. nine0003

Show respect. Whether a person has a visible disability or not, whether communication is difficult or not, everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. It seems to me that there is no point in explaining this point, but it does not prevent us all from thinking it over. nine0003

2. Communicate with them. No matter how the person communicates with you, including if they use an iPad, computer, SMS, typing, or spoken language to communicate, listen to them, ask questions, and listen for answers. Autistic people are the ultimate experts on their experiences, and there is something for everyone to learn from them. Many adults on the autism spectrum work very hard to share their ideas and important experiences with others about autism as part of our world. There are plenty of examples of this: this is the new book by Carly Fleischman, and the biography of Temple Grandin and the funny comics “Dude, I’m an Aspie!” nine0003

3. Analyze your own behavior. Do you do anything strange when you are alone? Does it happen that you interrupt other people? Don't you have a habit of tapping your foot on the floor or your fingers on the table when you're nervous or bored? Each of us has self-stimulating or self-regulating behaviors. The repetitive behavior in autism may get more attention, it may be much more intense or stereotyped, but the essence is the same. And we all make social mistakes from time to time and are unwittingly rude or annoying. Everyone breaks the unwritten social rules from time to time. nine0003

The repetitive behavior in autism may get more attention, it may be much more intense or stereotyped, but the essence is the same. And we all make social mistakes from time to time and are unwittingly rude or annoying. Everyone breaks the unwritten social rules from time to time. nine0003

4. Think of an apology. As Muslims, our family follows the "make up an apology" rule (or at least they should). Some people complain that autistic people are rude or annoying, but if we know that the person is autistic (and even if we don't), we should "think of excuses" for their actions before getting offended and ignoring the other person. Someone may seem impolite, for example, as John Elder Robinson describes in his book Be Different, a person can change the TV channel even though there are other people in the room watching it. But is there malicious intent in such behavior? Or has the person really not noticed that other people are watching TV, or that they are even present in the room? nine0003

5. Give up pity. Pity involves speculation about other people's failures and feeling superior due to one's own good fortune. One can feel sorry for someone who has suffered a sudden misfortune - the loss of a family member, cancer, the destruction of a house during a natural disaster. These are sudden events that we have no control over. Pitying a person just because their mind or body has evolved differently than yours means that you consider that person helpless and that you ignore their attempts to use their existing abilities and strengths to control their life as much as possible. Pity is the exact opposite of acceptance, give it up. nine0003

Give up pity. Pity involves speculation about other people's failures and feeling superior due to one's own good fortune. One can feel sorry for someone who has suffered a sudden misfortune - the loss of a family member, cancer, the destruction of a house during a natural disaster. These are sudden events that we have no control over. Pitying a person just because their mind or body has evolved differently than yours means that you consider that person helpless and that you ignore their attempts to use their existing abilities and strengths to control their life as much as possible. Pity is the exact opposite of acceptance, give it up. nine0003

Five ways to show acceptance towards parents of autistic children

1. Stop using catastrophic language. This is dangerous. We can control how we react and how we communicate with parents, and the media bears the lion's share of the responsibility for this. Do not escalate the situation, do not say that you are sorry, because despair has a dangerous effect on parents, because of such views, children were killed!

2. Stay close. This is the most reliable way to help. If parents suffer from stress or chronic fatigue, listen to them. Offer them ready meals, washing dishes, babysitting. And at the same time, do not forget about point 1.

Stay close. This is the most reliable way to help. If parents suffer from stress or chronic fatigue, listen to them. Offer them ready meals, washing dishes, babysitting. And at the same time, do not forget about point 1.

3. Do not judge or give "good advice". "I've been reading about diet/theory/research/treatment", "Have you heard that Jenny McCarthy...", "I'm sure he'll outgrow it", "You need to be more consistent." You want the best, we understand that, but we've heard it all before, it's just another media hysteria, just another legacy of accusations against parents. I have learned to ask questions rather than offer advice or opinions about things I don't know: "What therapies are you planning to try?" Tell me what will happen! or simply “I would like to offer you some solution. If you want to talk, then let me know, at least I will always listen. nine0003

4. Invite them. That party that is sure to be too intense for their special child? Invite them anyway.