How to help child with executive function disorder

Your Child's 7 Executive Functions — and How to Boost Them

Mom helping her ADHD daughter with homework1 of 11

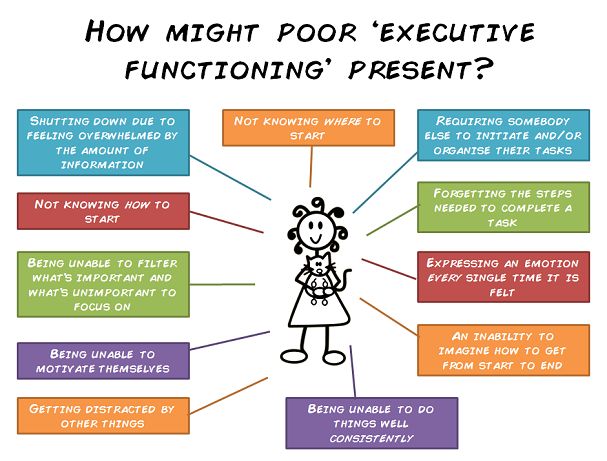

Understanding Executive Dysfunction

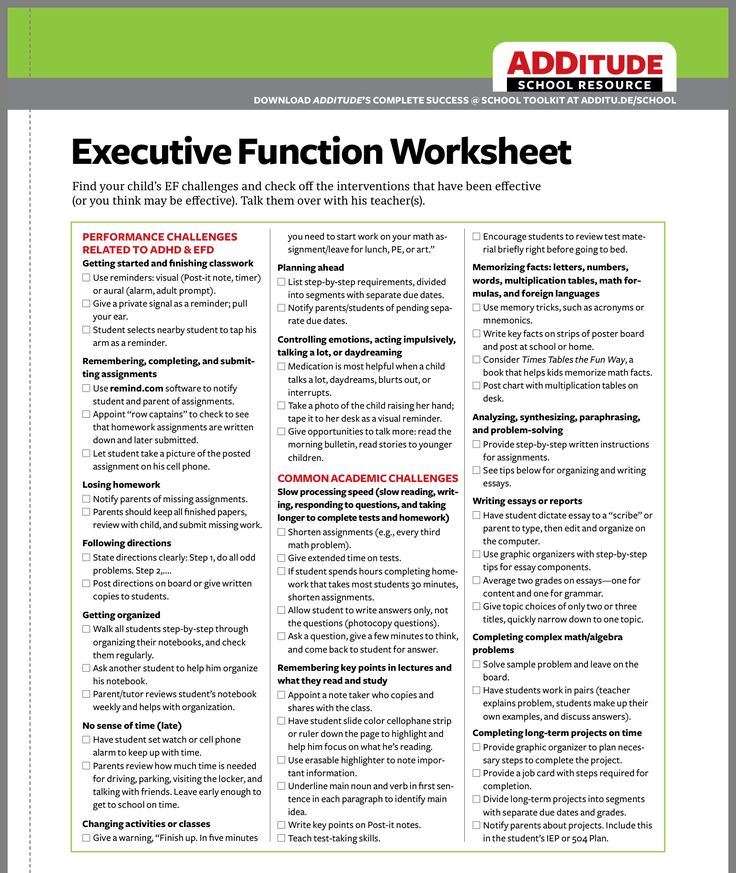

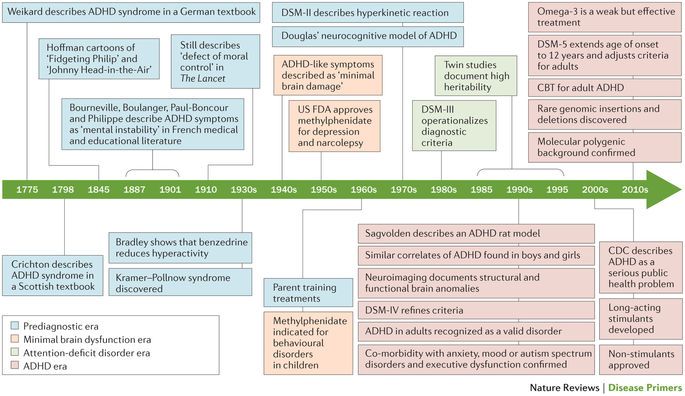

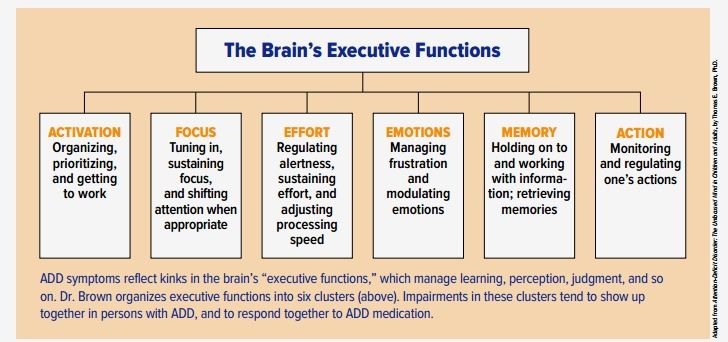

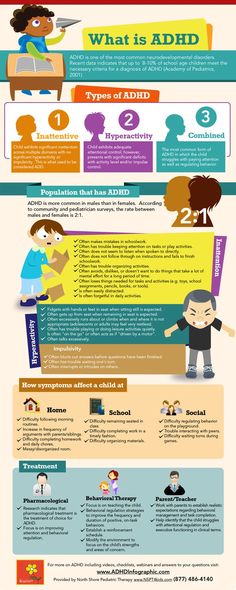

Children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD or ADD) tend to struggle with these 7 core executive dyfunctions:

- Self-awareness

- Inhibition

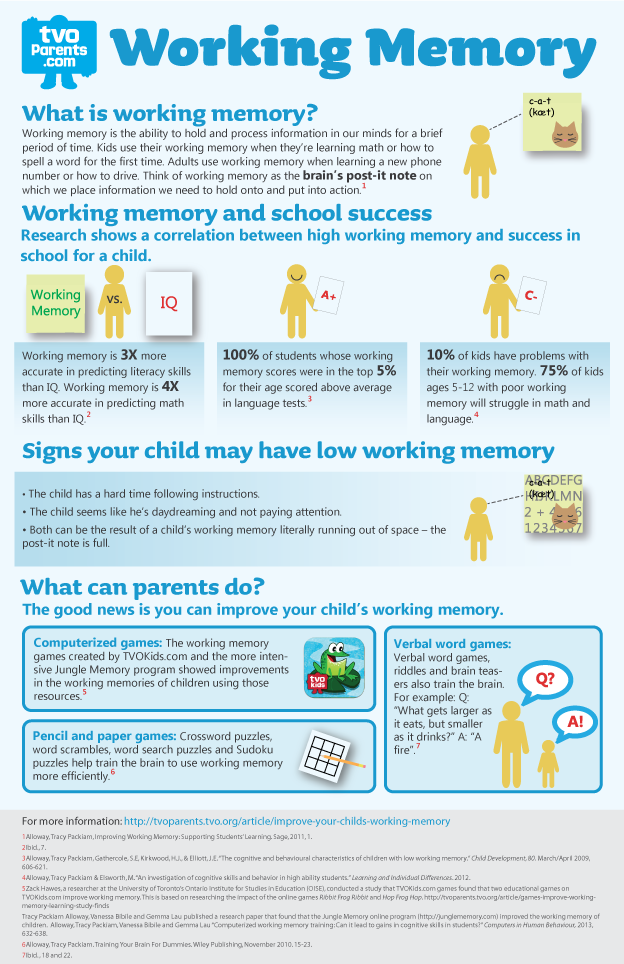

- Non-verbal working memory

- Verbal working memory

- Emotional self-regulation

- Self-motivation

- Planning and problem solving

Here's how you can help your child build up these muscles, gaining more control over their ADHD symptoms and taking strides toward independence along the way.

A father sits in the grass under a tree and talks with his son about executive function2 of 11

1. Enforce Accountability

A lot of parents wonder how much accountability is appropriate. If ADHD is a disability outside of my child’s control, should she be held accountable for her actions?

My answer is an unequivocal yes. The problem with ADHD is not with failure to understand consequences; it’s with timing. With the steps that follow, you can help your child bolster her executive functions — but the first step is to not excuse her from accountability. If anything, make her more accountable — show her you have faith in her abilities by expecting her to do what is needed.

3 of 11

2. Write It Down

Compensate for working memory deficits by making information visible, using notes cards, signs, sticky notes, lists, journals — anything at all! Once your child can see the information right in front of him, it’ll be easier to jog his executive functions and help him build his working memory.

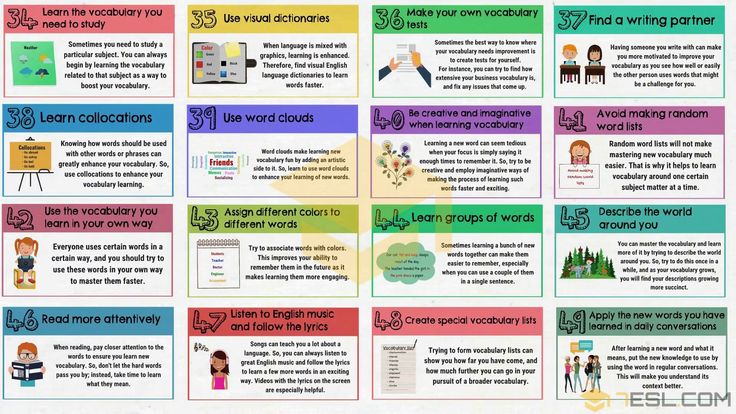

[Download This Free Checklist: Common Executive Function Challenges — and Solutions]

Three pocket watches in sand. People with impaired executive function need them to keep track of time.

4 of 11

3. Make Time External

Make time a physical, measurable thing by using clocks, timers, counters, or apps — there are tons of options! Helping your child see how much time has passed, how much is left, and how quickly it’s passing is a great way to beat that classic ADHD struggle, “time blindness.”

A doctor gives a girl a lollipop after teaching her about executive function.5 of 11

4. Offer Rewards

Use rewards to make motivation external. Someone who struggles with executive functions will have trouble motivating herself to complete tasks that don’t have immediate rewards. In these cases, it’s best to create artificial forms of motivation, like token systems or daily report cards. Reinforcing long- term goals with short-term rewards strengthens a child’s sense of self-motivation.

A child with ADHD holds 1,2,3 stacked blocks – close up6 of 11

5.

Make Learning Hands On

Make Learning Hands OnPut the problem in their hands! Making problems as physical as possible — like using jelly beans or colored blocks to teach simple adding and subtracting, or utilizing word magnets to work on sentence structure — helps children reconcile their verbal and non-verbal working memories, and build their executive functions in the process.

A mom reads a book about executive function to her daughter laying in her lap on the couch7 of 11

6. Stop to Refuel

Self-regulation and executive functions come in limited quantities. They can be depleted very quickly when your child works too hard over too short a time (like while taking a test). Give your child a chance to refuel by encouraging frequent breaks during tasks that stress the executive system. Breaks work best if they’re 3 to 10 minutes long, and can help your child get the fuel they need to tackle an assignment without getting distracted and losing track.

[Take This Test: Could Your Child Have an Executive Function Disorder?]

A baseball coach and his players with ADHD cheer after winning a game8 of 11

7.

Practice Pep Talks

Practice Pep TalksYou know that locker room pep talk before a big game? Your child needs one every day — sometimes more often. Teach your child to pump herself up by practicing saying “You can do this!” Positive self-statements push kids to try harder and put them one step closer to accomplishing their goals. Visualizing success and talking themselves through the steps needed to achieve it is another great way to replenish the system and boost planning skills.

A boy with ADHD holds a soccer ball and leans against a tree in a park9 of 11

8. Get Physical

Physical exercise has tons of well-known benefits — including giving a boost to your child’s executive functioning! Routine physical exercise throughout the week can help refuel the tank (even make the tank bigger!) and help him cope better with his ADHD symptoms. Exercise can be found anywhere — try an organized sport, a bi-weekly park playdate, or a spur-of-the-moment run around the backyard!

A boy drinks juice with his cereal to boost executive function with sugar10 of 11

9.

Sip on Sugar (Yes, Really)

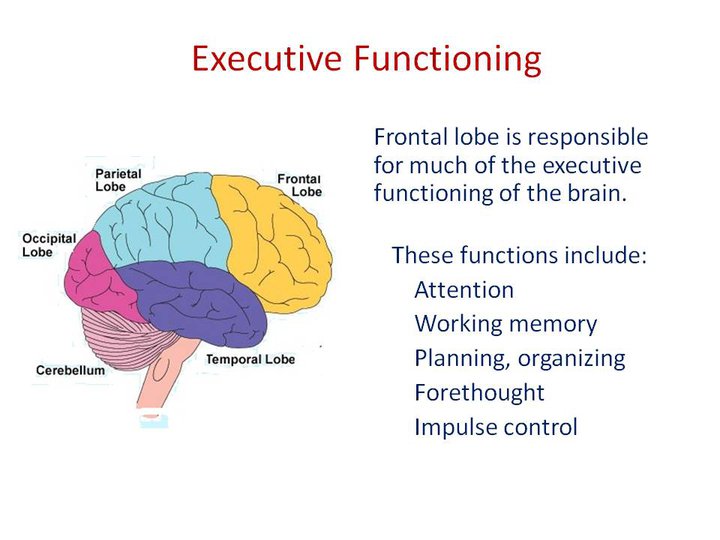

Sip on Sugar (Yes, Really)Sugar has sometimes been known to exacerbate ADHD symptoms, but when your child is doing a lot of executive functioning (like taking an exam or finishing a big project), it may be a good idea to have her sip on some sugar-containing fluids, like lemonade or a sports drink. The glucose in these drinks fuels the frontal lobe, where the executive functions come from. The operative word here is “sip” — just a little should be able to keep your child’s blood glucose up enough to get the job done.

A boy with ADHD hugs his father after a hard day11 of 11

10. Show Compassion

This is a big one, folks. In most cases, individuals with ADHD are just as smart as their peers, but their executive function problems keep them from showing what they know. The key to treatment ischanging their environment to help them do that. So it’s important that the people in their lives — especially parents — show compassion and willingness to help them learn. When your child messes up, don’t go straight to yelling. Try to understand what went wrong — and how you can help him learn from his mistake.

When your child messes up, don’t go straight to yelling. Try to understand what went wrong — and how you can help him learn from his mistake.

[Read This Next: Treatments for Weak Executive Functions]

Help for Executive Functions | Child Mind Institute

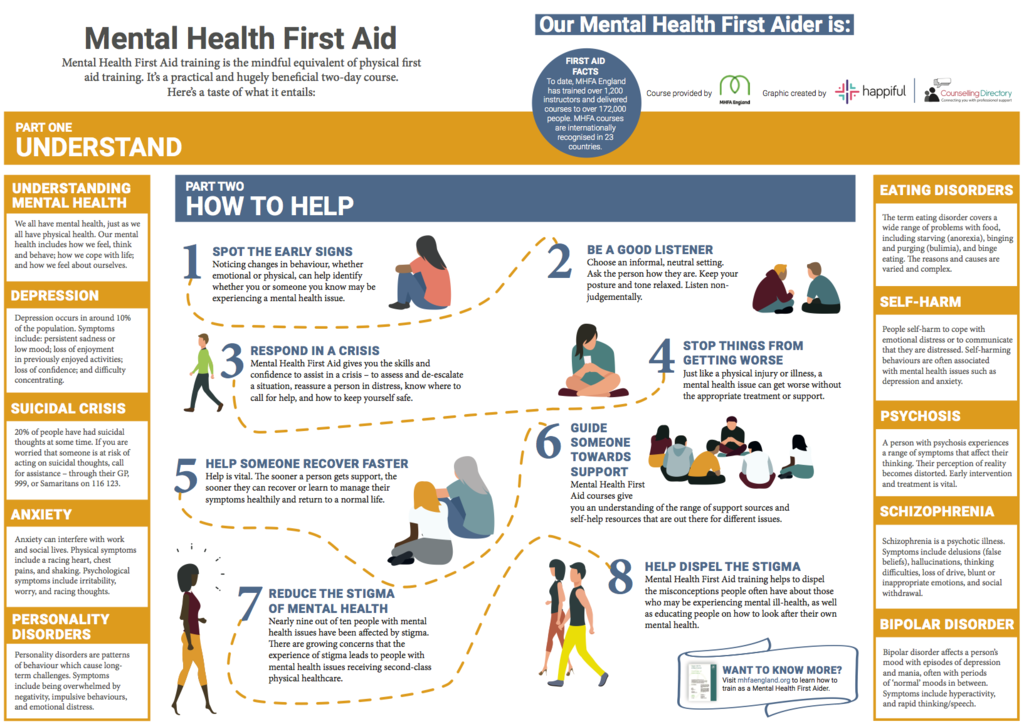

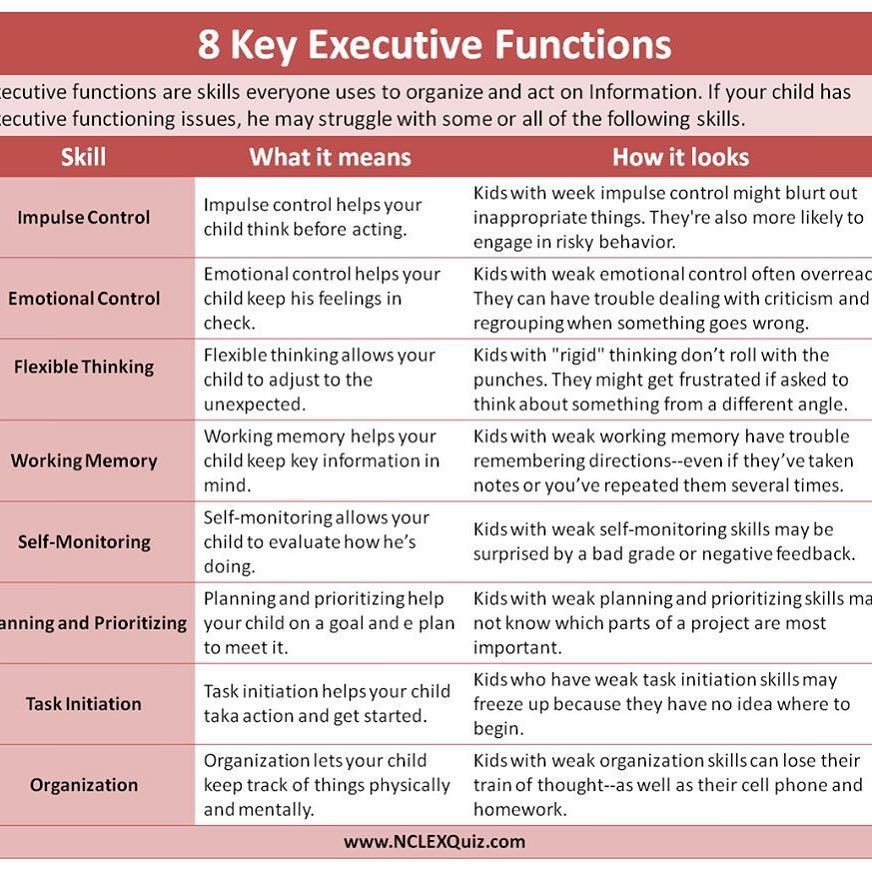

The first time you hear that your 7-year-old son is weak in “executive functions” it sounds like a joke. No kidding—that’s why he’s a first grader, not a CEO. But executive functions are the essential self-regulating skills that we all use every day to accomplish just about everything. They help us plan, organize, make decisions, shift between situations or thoughts, control our emotions and impulsivity, and learn from past mistakes. Kids rely on their executive functions for everything from taking a shower to packing a backpack and picking priorities.

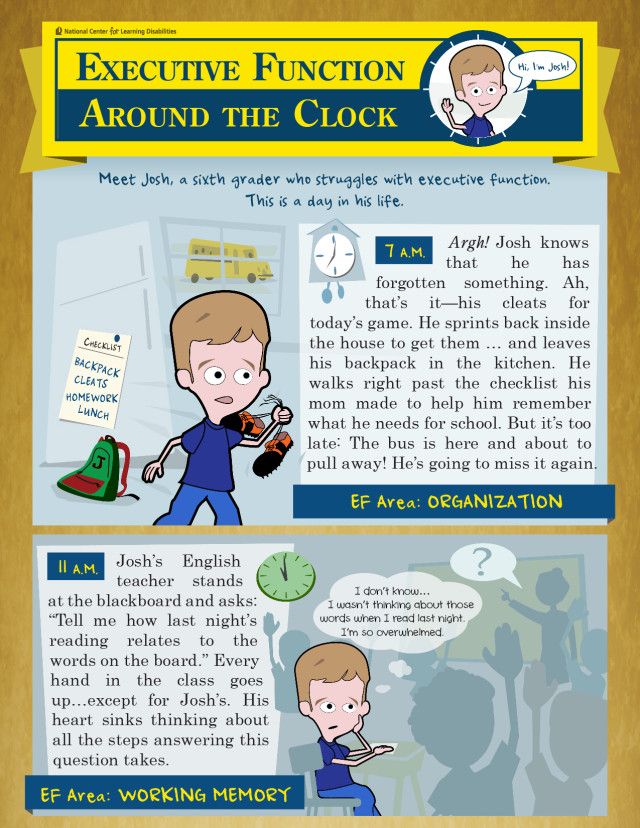

Children who have poor executive functioning, including many with ADHD, are more disorganized than other kids. They might take an extraordinarily long time to get dressed or become overwhelmed while doing simple chores around the house. Schoolwork can become a nightmare because they regularly lose papers or start weeklong assignments the night before they are due.

Schoolwork can become a nightmare because they regularly lose papers or start weeklong assignments the night before they are due.

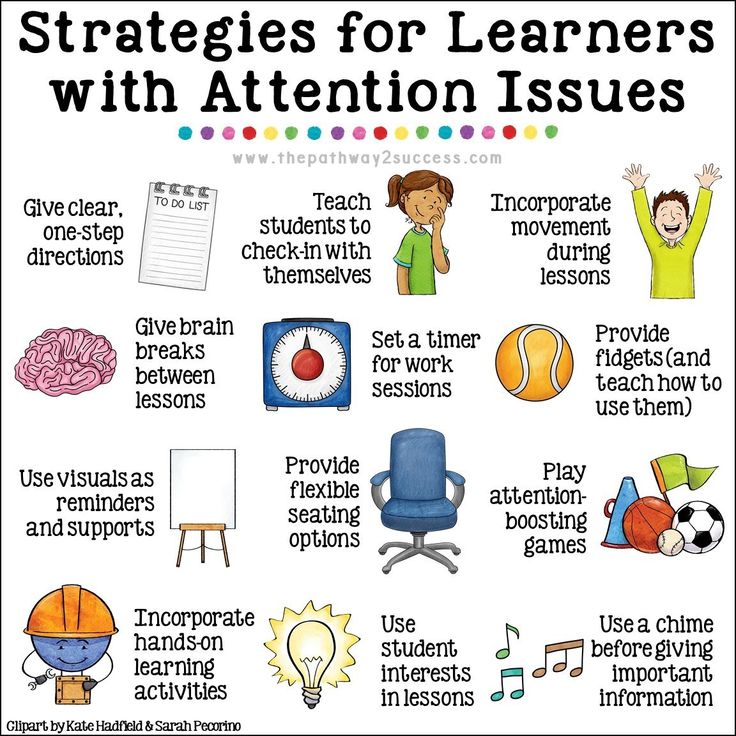

Learning disorder specialists have devised ways to bolster the organizational skills that don’t come naturally to a child with poor executive functioning. They teach a mix of specific strategies and alternative learning styles that complement or enhance a child’s particular abilities. Here are some of the tools they teach kids—and parents—to help them tackle school work as well as other responsibilities that take organization and follow-through.

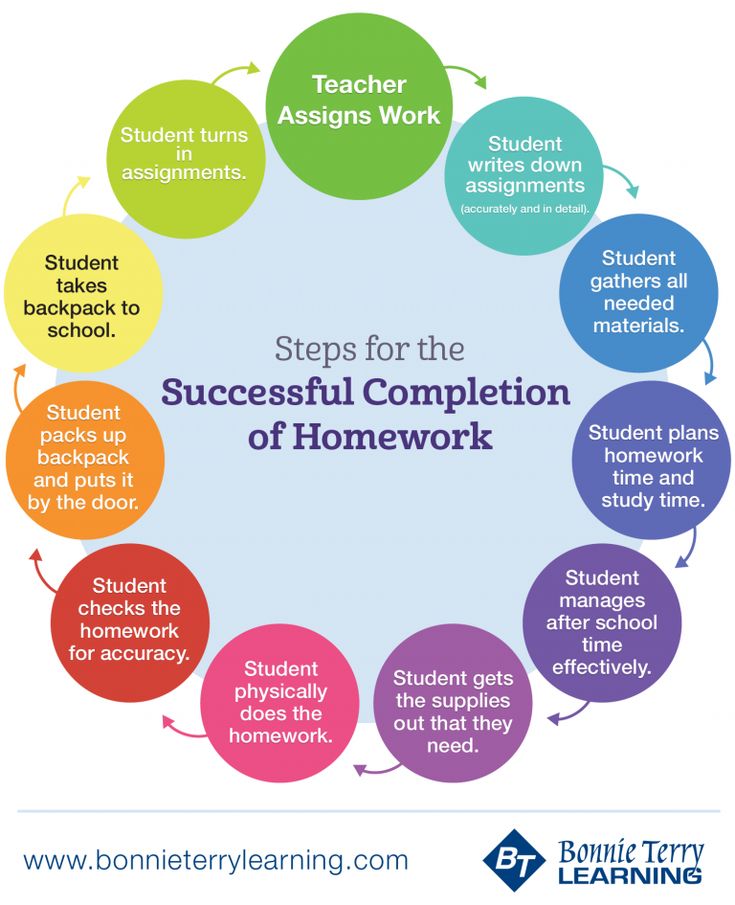

Checklists

The steps necessary for completing a task often aren’t obvious to kids with executive dysfunction, and defining them clearly ahead of time makes a task less daunting and more achievable. Following a checklist of steps also minimizes the mental and emotional strain many kids with executive dysfunction experience while trying to make decisions. Ruth Lee, an educational therapist, explains, “Often these kids will get so wrapped up in the decision-making process that they never even start the task. Or, if they do begin, they’re constantly starting and restarting because they’ve thought of a better way to do it. In the end they’re exhausted when the time comes to actually follow though.” With a checklist, kids can focus their mental energy on the task at hand.

Or, if they do begin, they’re constantly starting and restarting because they’ve thought of a better way to do it. In the end they’re exhausted when the time comes to actually follow though.” With a checklist, kids can focus their mental energy on the task at hand.

You can make a checklist for nearly anything, Lee notes, including how to get out of the house on time each morning—often a daily struggle for kids with executive dysfunction. Some parents say posting a checklist of the morning routine can be a sanity saver: make your bed, brush your teeth, get dressed, have breakfast, grab your lunch, get your backpack. Lee also recommends completing as many of the morning tasks as possible the night before. Lunches can be made ahead of time, clothes can be laid out, and backpacks can be packed and waiting by the door. It takes a little extra planning, she adds, but doing the work ahead of time can prevents a lot of drama the next day.

Set time limits

When making a checklist, many educational therapists also recommend assigning a time limit for each step, particularly if it is a bigger, longer-term project. Matthew Cruger, PhD, Director of the Child Mind Institute Learning and Development Center, likes to practice breaking down different kinds of homework assignments with kids to get them used to the steps required—and how long they might take. He describes recently working with a fifth grader who could think of only two steps required to complete a book report—writing the report and then turning it in. The time involved in reading the book slipped his mind.

Matthew Cruger, PhD, Director of the Child Mind Institute Learning and Development Center, likes to practice breaking down different kinds of homework assignments with kids to get them used to the steps required—and how long they might take. He describes recently working with a fifth grader who could think of only two steps required to complete a book report—writing the report and then turning it in. The time involved in reading the book slipped his mind.

Use that planner

Educational specialists also highlight the cardinal importance of using a planner. Most schools require students to use a planner these days, but they often don’t teach children how to use them, and it won’t be obvious to a child who is overwhelmed by—or uninterested in—organization and planning. This is unfortunate because kids who struggle with executive functioning issues have poor working memory, which means it is hard for them to remember things like homework assignments. And working memory issues tend to snowball. Dr. Cruger explains, “Kids don’t remember that they won’t remember their homework if they don’t write it down. It doesn’t matter how many times they forget. Once a frustrated father told me, ‘It’s like he has this delusion that he’ll remember it!’” As a backup to planners, many schools are also using software platforms like eChalk to create webpages teachers use to post homework assignments and handouts—giving kids with executive dysfunction one less thing to worry about.

Dr. Cruger explains, “Kids don’t remember that they won’t remember their homework if they don’t write it down. It doesn’t matter how many times they forget. Once a frustrated father told me, ‘It’s like he has this delusion that he’ll remember it!’” As a backup to planners, many schools are also using software platforms like eChalk to create webpages teachers use to post homework assignments and handouts—giving kids with executive dysfunction one less thing to worry about.

Spell out the rationale

While a child is learning new skills, it is essential that he understand the rationale behind them, or things like planning might feel like a waste of time or needless energy drain. Kids with poor organizational skills often feel pressured by their time commitments and responsibilities, and can be very averse to delay. “It’s almost like they’re making neuroeconomical decisions,” Dr. Cruger says. “They’re constantly weighing things to see if it’s worth their effort, and planning can feel like a waste of time if you don’t understand the rationale behind it. ” Older kids are particularly resistant because they’re more stuck in their ways. “They’ll say, ‘This is what works for me,’ even if their method really isn’t working,” says Dr. Cruger. Explaining the rationale behind a particular strategy makes a child much more likely to commit to doing it.

” Older kids are particularly resistant because they’re more stuck in their ways. “They’ll say, ‘This is what works for me,’ even if their method really isn’t working,” says Dr. Cruger. Explaining the rationale behind a particular strategy makes a child much more likely to commit to doing it.

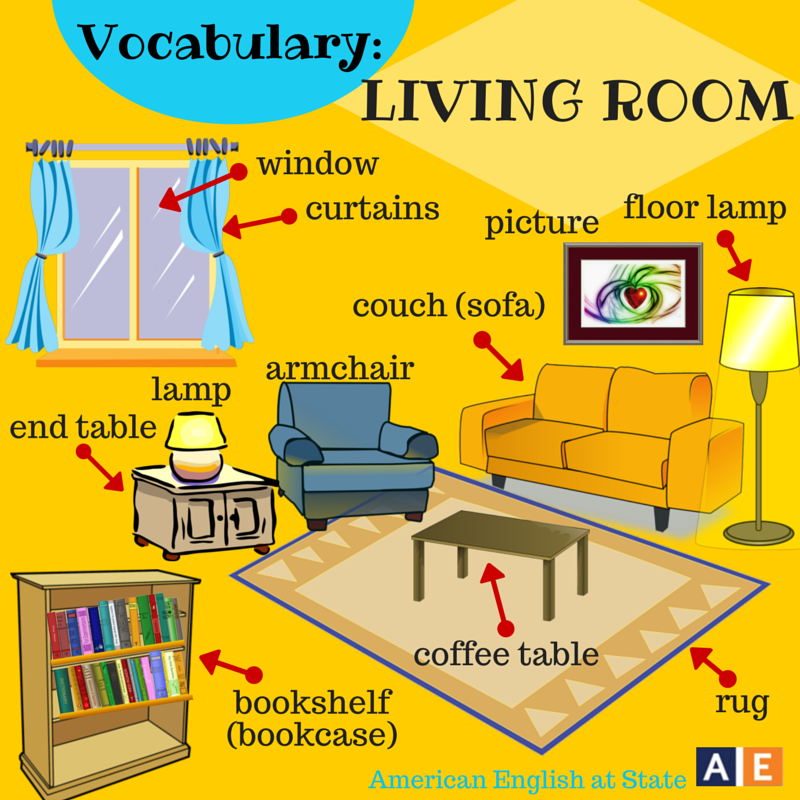

Explore different ways of learning

Educational specialists like Mara Koffman, MA, who founded Braintrust, a tutoring service for kids with learning issues, advocate using a variety of strategies to help kids understand—and remember—important concepts. Visual learners, for example, benefit from using graphic organizers as a reference. Students learning how to write a paragraph might follow the hamburger paragraph model, a diagramed drawing of a hamburger in which each sandwich component matches a part of a paragraph—the top bun is the thesis, the three supporting sentences are the lettuce, tomato, and patty, and the bottom bun is the conclusion sentence. Some versions of the hamburger paragraph act as a visual aid while others double as forms that a child can fill in.

Other kids remember things better if there is a motion supporting it, like counting on their fingers, which is good for visual and tactile learners. Younger children benefit from self-talking to reduce anxiety and Social Stories, which are narratives about a child successfully performing a certain task or learning a particular skill. Social Stories are told from a child’s first-person perspective and are similar to self-talk, but they can also double as a checklist because they break tasks into clear steps and can be referred to later.

As kids get older and are expected to memorize a lot of dry factual information, Koffman recommends mnemonic devices as a way to structure information in a more memorable way. But with all of the different learning strategies out there, Dr. Cruger stresses the importance of not overwhelming kids. Ideally the educational specialist should be working with your child on one new skill at a time, and spending at least two weeks practicing before evaluating how effective or ineffective it is and moving on to anything new.

This is particularly important for older kids, who typically struggle more to get started with their homework. Educational specialists recommend starting homework at the same time every day. Expect some resistance from older kids, who often prefer to wait until they feel like doing their work. Dr. Cruger strongly advises against waiting to start homework. “Realistically, the desire to start homework probably isn’t going to come. A kid who is waiting for inspiration to strike will still be forced to start his homework eventually, but it will probably be at 11 o’clock. That’s clearly a bad work model.” Ideally, kids should come home, unpack their bag, have a snack, and then get started. Homework is best done in a quiet, well-lit space fully stocked with paper and pencils because a search for supplies can quickly derail homework time. Any space with minimal distractions is good. Some families find doing homework on the kitchen table works best for their child, particularly if a parent is nearby to supervise and answer questions.

Use rewards

For younger kids, Koffman recommends putting a reward system in place. “Younger kids need external motivators to highlight the value of these new strategies. Something like a star chart, where kids see the connection between practicing their skills and working towards a reward, works very well.” Besides, Koffman notes, “It’s also a good way to communicate to kids that their parents and their teacher also value this skill.” If you’re using a reward chart, hanging it in the designated homework area can be a good incentive. For older kids who aren’t as motivated by things like rewards, parents should still be encouraging. Koffman recommends parents checking in with older kids. “Ask how things are going or offer help. Tell them you appreciate all the hard work they’re doing. School is really hard for a lot of kids—it shouldn’t be a given that learning these things is easy.”

Developing new strategies for learning isn’t easy either. Initially, it can put kids who are already self-conscious even further outside their comfort zone, but it’s worth the effort. We use our organizational skills every day in a million ways, and they are essential to our success in school and later as adults. Getting organized even gives us more time to play videogames.

We use our organizational skills every day in a million ways, and they are essential to our success in school and later as adults. Getting organized even gives us more time to play videogames.

Development of Executive Functions in Children - Child Development

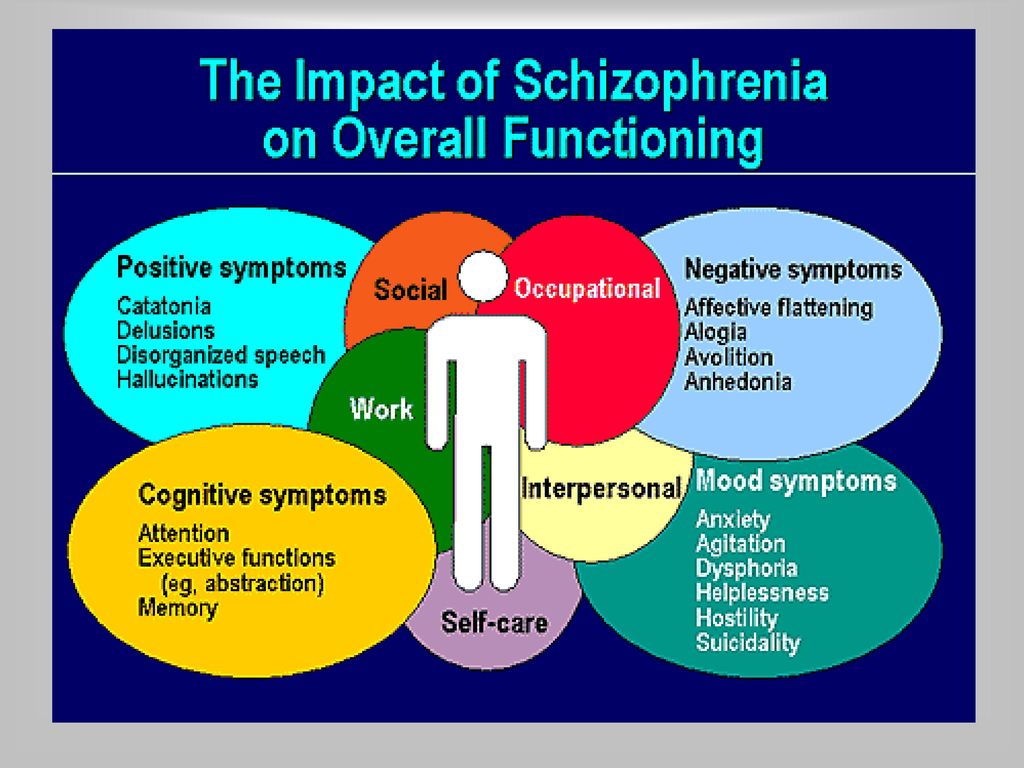

Executive functions are cognitive skills that we need in order to control and regulate our thoughts, emotions and actions in moments of conflict or under the influence of distractions. Psychologists sometimes distinguish between "cold" executive functions, which are strictly cognitive skills (such as mental numeracy), and "hot" executive functions that help regulate emotions (such as the ability to manage anger). nine0003

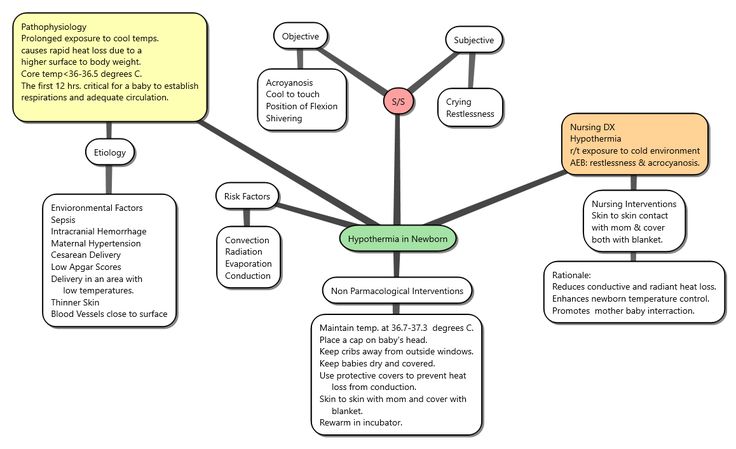

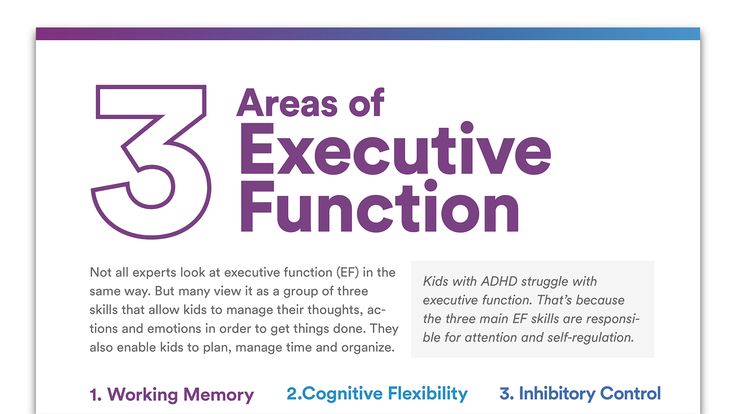

There are three types of executive functions:

1. Self-control - the ability to resist temptation and do the right thing instead. Self-control helps children focus, act less impulsively, and stay focused while doing work.

2. Working memory - the ability to remember information, guess where it might be used, connect ideas, and prioritize.

3. Cognitive flexibility - the ability to think creatively and change one's behavior in accordance with changing circumstances. Cognitive flexibility allows us to use our imagination and creativity to solve problems. nine0003

How important is this?

Executive functions are very important for a child's development. This is evidenced by the fact that by the extent to which the child's executive functions are developed at an early age, it can be assumed with a high degree of certainty how high his school performance will be, how much he will be able to adapt in society, how much he will adhere to a healthy lifestyle and etc.

Therefore, it is extremely important for parents to find ways to support the development of executive functions in the first years of a child's life. nine0003

What is known already and ?

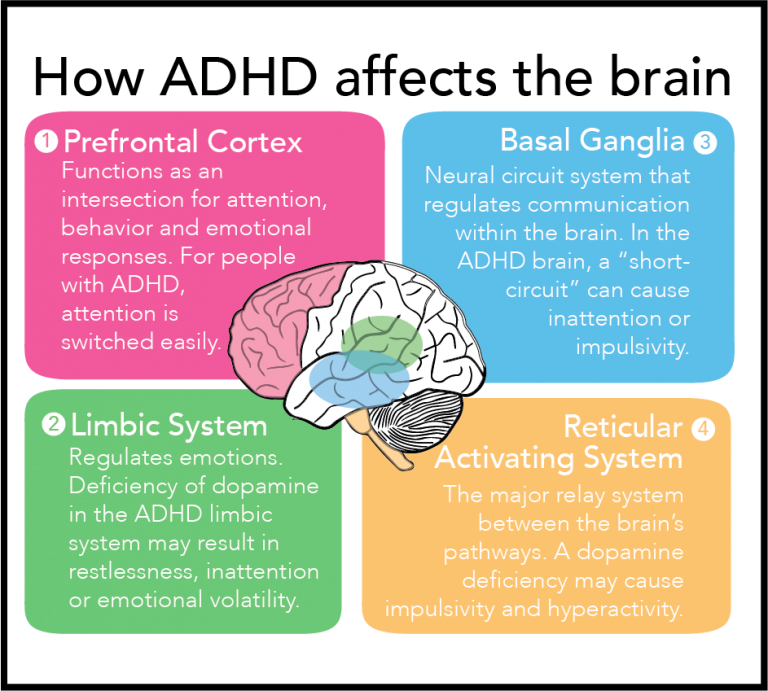

It takes time for a child to fully develop executive functions. This is partly due to the slow maturation of the prefrontal cortex. Development of executive functions becomes noticeable when children remind themselves of important goals (for example, when they refuse to watch TV in order to do their homework).

Development of executive functions becomes noticeable when children remind themselves of important goals (for example, when they refuse to watch TV in order to do their homework).

Also, development of executive functions occurs when children learn to analyze their environment in order to decide how to act in a given situation (for example, they understand that they need to learn lessons in order to pass an exam, and therefore refuse to watch TV). Lack of executive development may explain, for example, why young children seem stubborn and refuse to follow their parents' logical directions (eg, refuse to wear a hat in winter). Often, executive functions are poorly developed in children raised in poor families. nine0003

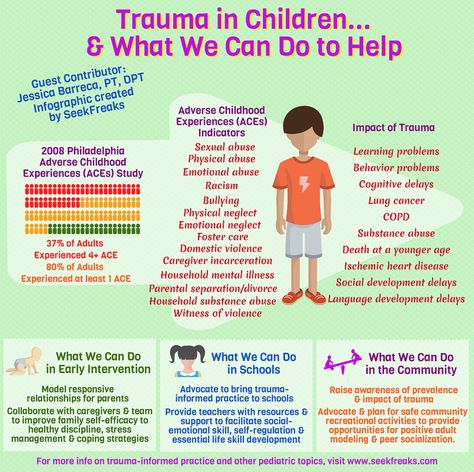

Children are very sensitive to early emotional experiences that may interfere with the development of executive functions or, conversely, contribute to it. For example, stress can be so detrimental to the development of a child's executive functions that their behavior may be similar to that of a child with ADHD (which is why children with impaired executive functions are often misdiagnosed as ADHD).

On the other hand, positive emotional experiences (eg, good relationships with parents at an early age) can protect the child from the negative impact of stressors (eg, difficult family conditions). Therefore, executive functions in such children develop normally. Children of responsive parents who use a gentle approach to parenting rather than strict discipline also tend to develop their executive functions better. nine0003

Well-developed executive functions lead to high academic achievement, well-developed social and emotional skills. In the early grades, executive functions have a stronger influence on a child's academic performance than intelligence and ability to read or count. Psychologists suggest that this is due to the fact that executive functions help the child navigate in an ever-changing environment. Therefore, their development is especially important for those children who grow up in disadvantaged conditions.

Separate executive functions are connected with the fact that the child understands the thoughts and actions of other people. For example, a child understands that other people may have ideas about the world that are different from their own. This is a necessary skill for successful social interaction.

For example, a child understands that other people may have ideas about the world that are different from their own. This is a necessary skill for successful social interaction.

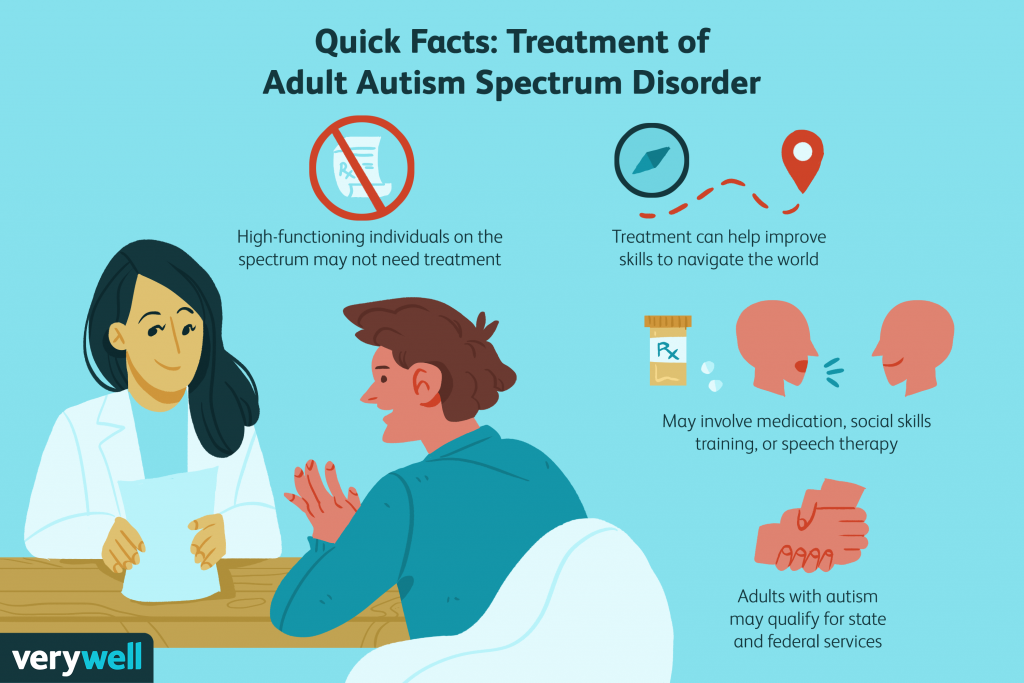

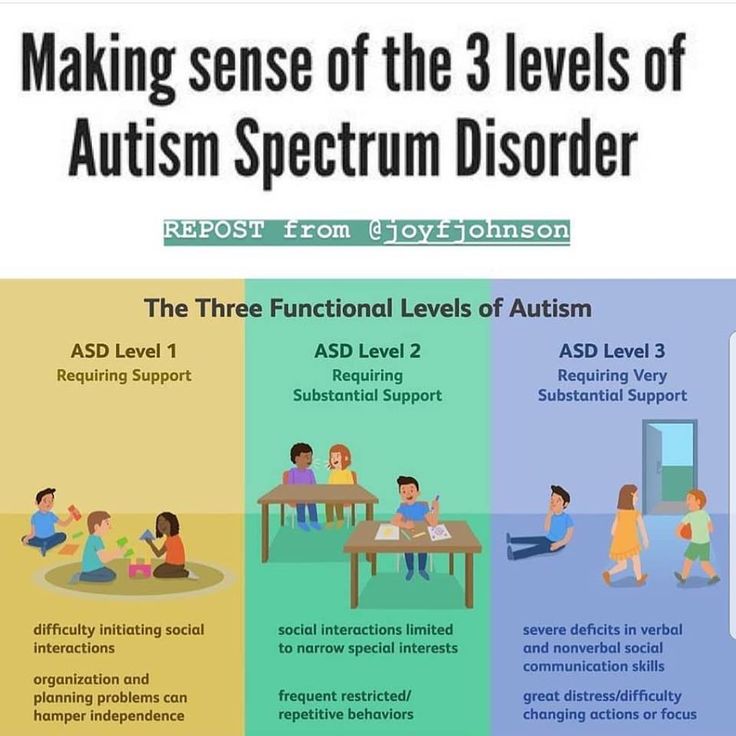

The benefits of well-developed executive functions are clear. At the same time, poor development of executive functions is characteristic of a number of disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, behavioral and learning disorders, autism, depression, etc. Early problems with the development of executive functions can persist throughout childhood and even adolescence. nine0003

What can do ?

Working with a child psychologist can help preschoolers develop their executive functions. Through this, they can improve academic performance, develop social and emotional skills, and create new neural connections. Early intervention can also reduce the difficulties associated with disorders such as ADHD and conduct disorders. Such classes give good results for children aged 4-5 years. In the course of such classes, the child learns the skills of self-regulation, most often in a playful way. nine0003

Such classes give good results for children aged 4-5 years. In the course of such classes, the child learns the skills of self-regulation, most often in a playful way. nine0003

There are also a number of activities that help develop the child's executive functions. Such activities include music, yoga, meditation, martial arts, etc.

It is also worth paying attention to the atmosphere in which learning takes place in the lower grades. Children should be more active during the lesson, so spend more time in small groups and less time in large groups. Children with well-developed executive functions require less intervention from teachers. It is also important to eliminate all stress factors in the learning process. Younger children should also be taught in a playful way. For example, you can role-play various social situations with him. So the child learns more about different social roles and learns to adapt to constantly changing situations. nine0003

It is important to understand that executive functions develop over many years. And even a highly motivated child finds it difficult to follow all the instructions of the parents (for example, not to eat cookies before dinner) or to focus on something for a long time. So give your child time.

And even a highly motivated child finds it difficult to follow all the instructions of the parents (for example, not to eat cookies before dinner) or to focus on something for a long time. So give your child time.

Development of executive function in children with autism

Translator/editor: Marina Lelyukhina

Original: https://www.autism-programs.com/articles-on-autism/improving-executive-function.htm

Our Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/specialtranslations

Our VKontakte public: https://vk.com/public57544087

Our telegram channel: https://t.me /specialtranslations

If you liked the material - help those who need help:

http://specialtranslations.ru/need-help/

Copying the full text for distribution in social networks and forums is possible only by quoting publications from official pages Special translations or through a link to the site. When quoting text on other sites, put the full translation heading at the beginning of the text. nine0014

When quoting text on other sites, put the full translation heading at the beginning of the text. nine0014

What is an executive function?

Infants and young children, when confronted with almost any environmental stimulus, respond impulsively, literally and immediately. They have not yet had time to learn organized play activity, so from birth they are included in a kind of drift from one stimulus to another, impulsively snatching various objects from the environment and tasting them. The play of children at this age is usually chaotic and repetitive. nine0003

However, as children grow older, they quickly learn to keep their attention on several aspects of a task, plan their actions, keep this plan in mind and act on it. They can also recognize that they are making a mistake and modify their actions in accordance with the experience gained. As children age, they learn more and more to engage in organized, planned, and purposeful activities.

The capacity for purposeful activity depends on a number of mental processes, including the ability to organize, suppress impulses, selective attention, retention in memory, the ability to switch and plan one's actions. The ability to engage in purposeful activity, along with mental processes that provide such an opportunity, underlies the executive function. nine0003

Problems with executive function are neurological in nature and arise from a disturbance or delay in normal neurological development. The prefrontal cortex is primarily responsible for the development of the executive function, but for everything to work as it should, a whole “network” of coordinated brain regions is needed.

Executive function and autism

Since the 1990s, research on executive function has explored links between executive function and autism spectrum disorders. In 2004, Elizabeth L. Hill summarized the results of her experiments and concluded that although many children with ASD have problems with executive function, such a violation cannot be considered as one of the features of the spectrum, because there are children with ASD who have normal executive function. As a result, autism intervention programs have moved away from working on executive development to focus on developing social and communication skills that everyone on the spectrum struggles with. nine0003

As a result, autism intervention programs have moved away from working on executive development to focus on developing social and communication skills that everyone on the spectrum struggles with. nine0003

Not all people with ASD have executive function problems, but many do

according to some estimates, it is about 80%). Many fail to make significant progress in social and communication skills without additional work on developing executive function. Because the child cannot progress without taking into account the existing problems with the executive function, his condition may be assessed as more severe, i.e. talk about deeper autism or come to the conclusion that in addition to the spectrum, the child is also mentally retarded. But in this case, the problem will not be in a more severe form of autism or mental retardation, but in the fact that the person does not have a well-developed executive function. nine0003

For some people, problems with social and communication skills are not major problems. In the Growing Minds program, we worked with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder who were socially included, maintained good eye contact and tried to communicate with others as often as possible. But at the same time, they were not able to respond in a timely and sufficiently organized manner to the requests of parents and teachers, as well as to turn on and initiate complex play activities, due to significant problems with the development of the executive function. nine0003

In the Growing Minds program, we worked with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder who were socially included, maintained good eye contact and tried to communicate with others as often as possible. But at the same time, they were not able to respond in a timely and sufficiently organized manner to the requests of parents and teachers, as well as to turn on and initiate complex play activities, due to significant problems with the development of the executive function. nine0003

While formulating a valid definition of executive dysfunction and its place in autism theory is an important topic for research, the primary purpose of the Growing Minds program is to help children. Thus, we are not so much interested in what difficulties people with autism spectrum disorders have in general, but the problems of the individual child and the intervention program that he needs, which may need to be designed to take into account a number of difficulties and advantages. Some of them may or may not be based on the child being on the autism spectrum. For example, some children diagnosed with ASD may have problems with executive function, movement disorders (motion dyspraxia), speech apraxia, and overlapping disorders. nine0003

For example, some children diagnosed with ASD may have problems with executive function, movement disorders (motion dyspraxia), speech apraxia, and overlapping disorders. nine0003

Executive function and movement problems (dyspraxia)

Movement dyspraxia (difficulties with motor control) and executive function disorders often overlap. However, some children with motor problems are able to organize complex activities very well, given their motor difficulties, and without giving rise to the suspicion that they may have problems with executive function. Other children with obvious impairments in executive function develop motor development appropriate for their age (although more careful investigations may reveal more subtle impairments in motor development). nine0003

In all the cases mentioned, individuals make the best progress when teaching methods are designed to suit their particular difficulties. For training to be truly effective, each client must be assessed individually. At Growing Minds, we make every effort to recognize movement dyspraxia in clients, as well as monitor possible impairments in the area of executive function and the processes included in this spectrum of disorders.

At Growing Minds, we make every effort to recognize movement dyspraxia in clients, as well as monitor possible impairments in the area of executive function and the processes included in this spectrum of disorders.

The level of intelligence has no correlation with the development of the executive function

Executive function problems are a lot like having a great computer with good software but a broken "output" device, causing the monitor to flicker and the printer to refuse to print.

A child may be smart enough, but his executive function will be underdeveloped, and as a result he will get very low scores in intelligence tests. As the development of executive function improves, a child's developmental level will be easier to assess and test scores will begin to rise. Many children are actually much smarter, and as their executive function development improves, their abilities become more apparent. nine0003

Identifying possible executive dysfunction in your child with autism

Here are a number of areas that may be a sign that your child has some degree of executive dysfunction.

Organization

We use this term to refer to the child's ability to produce an organized, sustained response to a stimulus. There are many children with ASD who can perform some actions spontaneously, but at the same time are not able to perform the same actions in response to a request. For example, a child quickly puts on shoes when he wants to go for a walk, but does it many times more slowly (or does not do it at all) if he is asked to do so. Often this problem is associated with a lack of cooperation or motivation, but it can also be a sign of problems with executive function. The child may not be able to organize in time all the stages of work in order to fulfill the requirement, even if he is physically able to do it. Children with this problem find it difficult to organize and remember all the steps needed to complete a task, and even simple tasks tend to have more than one step. nine0003

Example. A simple matching task, when the child is asked to match an object with an identical one (in a group of three) lying on the table in front of him, he must look at the stimulus that must be matched, identify it, remember what it is, look at the stimuli lying on the table, determine which of them corresponds to the one presented, stretch, take a stimulus for comparison and place it next to the "paired" one.

Some children in this situation "lose the thread": they forget to look carefully at the stimulus to be matched and put it where it is necessary. Their mistakes and correct hits are due to the fact that they cease to coordinate their eyes, hands and mind to complete the task. The observer can explain the errors as problems of understanding (i.e., saying that the child simply does not understand which stimulus is related to which) or cooperation (the child is not motivated enough), but in addition, such a problem can be caused by a violation of the organization of actions - a violation of the executive function. nine0003

Impulse control

Some children with ASD find it difficult to control themselves enough to participate in structured activities. Often they find it difficult to even just sit still long enough to get through the lesson. Instead, they get up time after time and go to whatever grabs their attention at the moment. Children who find it difficult to control their impulses are constantly stuffing, grabbing, pinching, biting, and hitting everything that comes their way into their mouths, and then run away. Such behavior interferes with the child himself, upsets the parents and nullifies all attempts at learning. nine0003

Such behavior interferes with the child himself, upsets the parents and nullifies all attempts at learning. nine0003

Planning

In children with poorly developed executive function, it can be difficult to assess the ability to plan their own actions. In such a case, you can see how the child literally forgets what to do in order to complete the task, even if he is very motivated. If you ask him to give two specific items to the teacher, who in return will treat him to his adored chocolate, such a child will give only one item, and simply will not remember the second.

Selective attention

We recently worked with a child who could name one object when held in front of him. In this case, he can look at it and say what it is. If he was asked to name the same object lying on the table among others, he could not do it. It was difficult for him to keep the task in his memory, to understand what exactly he should do, to compare the task with the objects lying in front of him and choose the right one. Disturbances in the field of selective attention can be the cause of many difficulties. nine0003

Disturbances in the field of selective attention can be the cause of many difficulties. nine0003

Maintaining activities

Many children find it difficult to maintain their activities for long periods of time and can only focus on a task for a short time. For example, if he needs to solve 10 examples, the last 6 will be solved incorrectly or not solved at all, but he will solve the first four perfectly.

Switching attention

Many children with ASD find it difficult to switch from one task to another. If for some time the child was silent, it is difficult for him to start a conversation. If he is sitting on the floor and is asked to come to the table, this task will take time and effort. It is difficult for him to move from one task to another, even if he likes the latter more. If such a child is asked to solve 10 examples, he will probably make many mistakes in the first of them, since he will need time to switch his thinking to solving the tasks. But the last 6 such a child will solve correctly, because. the topic is familiar to him and he can easily cope with it if he manages to switch. nine0003

But the last 6 such a child will solve correctly, because. the topic is familiar to him and he can easily cope with it if he manages to switch. nine0003

Initiating activities

Some children manage to learn a wide variety of games and activities. They can engage in such activities completely on their own, but they cannot initiate it themselves. Even if they are very bored, such children will wait until someone else tells them what to do.

Emotion control

Many children with autism experience and express every emotion tenfold. These children have no problem expressing their own feelings. On the contrary, they need to understand that not every emotion is worth splashing out on others. The ability to restrain one's own feelings directly depends on the development of the executive function. If your child knows that he won't be able to watch TV any time soon if he throws a temper tantrum and the temper tantrum still happens, he probably has problems with his ability to control his emotions, that is, even if he tries his best to control himself, he it just doesn't work. nine0003

nine0003

Motor control

A number of complex forms of motor control are also associated with the development of executive function. The sequence of complex motor actions, processes consisting of several steps, and other complex activities complicate problems with impulse control, maintaining activity, keeping goals in mind, and so on. Choreography, yoga, martial arts, and competitive swimming can help develop executive function in many children. Impulse-based and unorganized activities do not affect the development of executive function. For example, freestyle swimming will not help you, but if a child is asked to swim breaststroke one way and backstroke the other, it will help him to practice executive function. nine0003

What can help?

Perhaps there are still undiscovered biomedical interventions that can help the child develop executive function, but so far they have not been found, we have to rely on "activity-dependent plasticity" in working on the development of executive function. In accordance with this principle, the brain adapts to the requirements that are placed on it.

In accordance with this principle, the brain adapts to the requirements that are placed on it.

The nervous system is much more variable and "plastic" than ever thought. New brain scanning techniques such as PET, CPT, MRI or functional MRI have shown us that the brain and nervous system work much like muscles in their work. If for several months at the proper frequency the brain performs certain tasks / certain demands are made on the person, the nervous system gradually adapts to new conditions. nine0003

If it is difficult for a child to switch, it can become a problem for the entire environment. Over time, the child's loved ones may stop asking him to move from one activity to another until he wants to, or protect him as much as possible from all the difficulties in the process of switching from one task to another, doing most of the work for him. Over time, such a child gets less and less opportunity to practice switching between different activities, and this becomes even more difficult for him. However, if you help him train to switch at least a dozen times a day for several months, his brain may adapt to the new conditions. nine0003

However, if you help him train to switch at least a dozen times a day for several months, his brain may adapt to the new conditions. nine0003

If a child is unable to successfully respond to more than a couple of requests a day, and then with your help he performs hundreds of instructions daily for several months, there is a chance that his nervous system will change.

Unit education

Children cannot learn if they are not given the opportunity to do so. Block training is a method that provides a vast field for training executive function skills. "Block" contains a clear instruction, a pause, if necessary - a hint and reinforcement in case of a successful answer. Each block for such a child is an opportunity to form an organized response and practice switching. During well-planned block learning, children also learn to control their impulses. nine0003

In some programs we use a "clicker" to count the number of learning blocks a child completes during the day. If he has problems with executive function, there may be about five hundred such “training approaches” per day. When a child does not have enough opportunities for training, there is a stagnation or “plateau” in his development.

If he has problems with executive function, there may be about five hundred such “training approaches” per day. When a child does not have enough opportunities for training, there is a stagnation or “plateau” in his development.

Pleasant Fast Blocks and Mixed Blocks

With many children with executive function problems, we work with Vincent Carbon's fast trial/block method. Studying the rate of delivery of educational blocks, he noted that at a high pace of learning, many children with ASD are less likely to demonstrate unwanted behavior, give more correct answers and hold their attention longer. In the course of our work, we also noted that children look happier and initiate activities more often with this approach. Over time, this approach to learning causes an overall increase in executive function, especially in the areas of fluency, productivity, response speed, switching, and information processing. nine0003

Rapid blocks usually include skills that the child has already mastered. These can be tasks for imitation, for distinguishing stimuli, or for naming. Tasks are mixed and completed at a fast pace during one session. In our work, we often do 90-second inserts, each of which includes 40 to 60 training blocks. The speed of completing tasks is determined by the child and the adult together.

These can be tasks for imitation, for distinguishing stimuli, or for naming. Tasks are mixed and completed at a fast pace during one session. In our work, we often do 90-second inserts, each of which includes 40 to 60 training blocks. The speed of completing tasks is determined by the child and the adult together.

This approach allows you to achieve several things at once. In one 15-minute session per day, led by an experienced teacher, a child goes through hundreds of learning blocks. This is an amazing opportunity to practice responding to a request for an organized response on time. Since the blocks are mixed, he also has a lot of opportunities to learn how to switch. The child learns to respond better - the ability to stay in activity is strengthened. Selective attention is fully developed. The child has little opportunity to be distracted by extraneous impulses, so he learns to work without having to deal with his impulsivity. nine0003

Many children with executive disabilities enjoy fast paced work. We believe that they think faster than they react. Helping a child to react as quickly as he thinks, he will act more coherently and get more pleasure and satisfaction from his work. The focus is on being able to control your own reactions. If the child scribbles answers in a hurry, this indicates poor control of impulses, while quick and accurate answers, on the contrary, indicate good control and fluency of reactions. nine0003

We believe that they think faster than they react. Helping a child to react as quickly as he thinks, he will act more coherently and get more pleasure and satisfaction from his work. The focus is on being able to control your own reactions. If the child scribbles answers in a hurry, this indicates poor control of impulses, while quick and accurate answers, on the contrary, indicate good control and fluency of reactions. nine0003

Influence on the therapeutic process and learning

If you are working with such a child, understanding his difficulties will be very helpful. For example, if such a child is comfortably seated on the couch, and you ask him to sit down at the table, he will not move. Perhaps it is difficult for him to switch and for him the path from the sofa to the table is too big a task. But if you understand his difficulties, you can change the task and ask him to stand up first, and after he gets up, come and sit down. nine0003

Switching problems are often mistaken for lack of cooperation, lack of motivation, or disobedience. However, if you break the task down into smaller steps, many children suddenly respond much better, even if nothing else changes. For switching problems, visual schedules, timers, warning signs, etc. are also very helpful.

However, if you break the task down into smaller steps, many children suddenly respond much better, even if nothing else changes. For switching problems, visual schedules, timers, warning signs, etc. are also very helpful.

Some children are so poorly organized that they make mistakes all the time, even if they know the material well. Imagine that a child knows well the names of 50 objects, but when you put an image of three of them in front of him and ask him to name, he cannot. In the course of observation, it is not possible to discover what the problem is: the child does not listen to the instruction, does not consider the stimuli lying in front of him in search of the right one, does not reach out to indicate it. In some cases, he does not look at objects at all and points to the first one that catches his eye, or reaches out to show before he hears the instruction. Is it possible, with the help of a hint, to teach him to listen first, then look and show? Yes. nine0003

For example, sometimes we use a “screen”, cover everything on the table with a piece of cardboard, get the child's attention and make sure he hears the name of the target stimulus before he sees all the stimuli on the table. Then we remove the screen and let him give his answer. Some children with this approach increase the number of correct answers from 33% with a choice of three to 100%.

Then we remove the screen and let him give his answer. Some children with this approach increase the number of correct answers from 33% with a choice of three to 100%.

How to help children with ASD improve their competence

In the examples above, the problem was not that the child did not understand the instructions, did not know the answer, did not want to cooperate, or was not motivated enough. It was difficult for each of them to cope with the task, even if his cognitive abilities and knowledge allowed him to do it. In some programs, children are encouraged to repeat the same tasks over and over again until the children begin to give from 90-100% correct answers. For kids who know the right answer but have trouble developing executive function, the mismatch between task level and comprehension level makes learning insanely boring. As a result, motivation is reduced, which further complicates functioning problems.

The switching and attention problems described above are just two examples of how the underlying developmental problems with executive function can affect your child. There are hundreds of options for the difficulties a child may face and many ways to help him show his true level of cognitive development through special training techniques. nine0003

There are hundreds of options for the difficulties a child may face and many ways to help him show his true level of cognitive development through special training techniques. nine0003

If your child is not responding to learning, or is not responding well enough, it is important to put aside general ideas of what his or her difficulties might be. Take a closer look at him and try to consider each of his response movements in detail. Some people call this approach "micro analysis". Consider that the child may have basic difficulties with functioning and organizational skills. Your child may know and be able to do much more than they let on because of developmental problems with executive function. The training of relevant skills over time can qualitatively affect the level of his understanding and development. nine0003

Copyright © 2012 Steven R. Wertz

I There are several types of "switchover" problems that are considered in connection with executive dysfunction. The term "switching" is often used in a situation where a child starts a task following one rule, but in the process must switch to other criteria when evaluating and building his activity.