How to help child deal with anger

Helping your child with anger issues

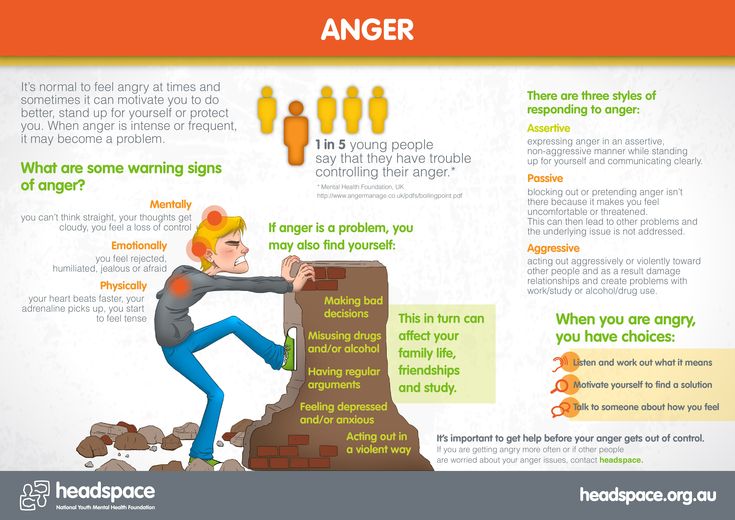

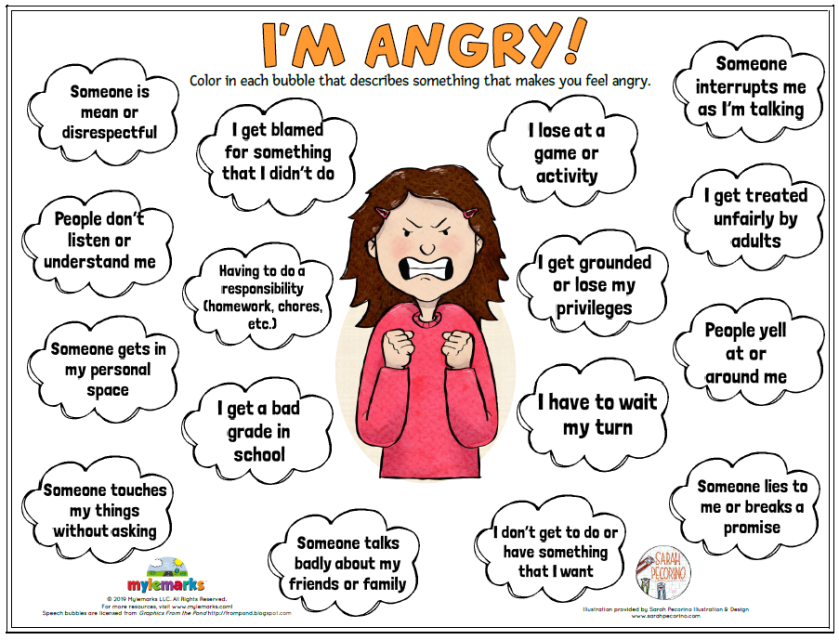

Anger is a normal and useful emotion. It can tell children when things are not fair or right.

But anger can become a problem if a child's angry behaviour becomes out of control or aggressive.

Why is your child so angry?

There are lots of reasons why your child may seem more angry than other children, including:

- seeing other family members arguing or being angry with each other

- friendship problems

- being bullied – the Anti-Bullying Alliance has information on bullying

- struggling with schoolwork or exams

- feeling very stressed, anxious or fearful about something

- coping with hormone changes during puberty

It may not be obvious to you or your child why they're feeling angry. If that's the case, it's important to help them work out what might be causing their anger.

Read our tips on talking to children about feelings.

Tackle anger together

Team up with your child to help them deal with their anger. This way, you let your child know that the anger is the problem, not them.

With younger children, this can be fun and creative. Give anger a name and try drawing it – for example, anger can be a volcano that eventually explodes.

How you respond to anger can influence how your child responds to anger. Making it something you tackle together can help you both.

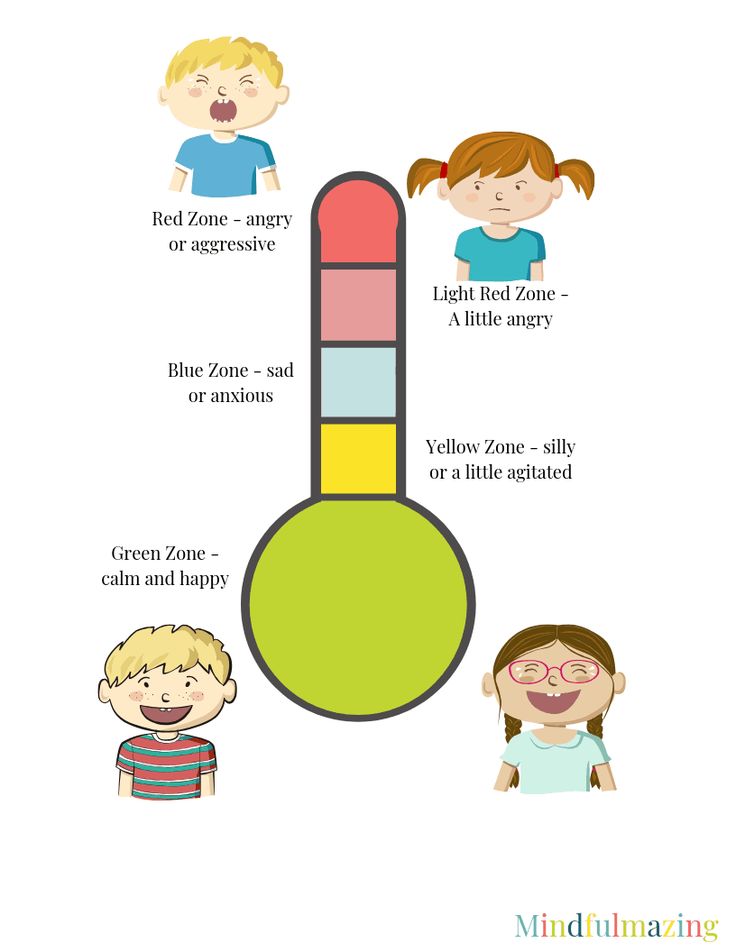

Help your child spot the signs of anger

Being able to spot the signs of anger early can help your child make more positive decisions about how to handle it.

Talk about what your child feels when they start to get angry. For example, they may notice that:

- their heart beats faster

- their muscles tense

- they clench their teeth

- they make a fist

- their stomach churns

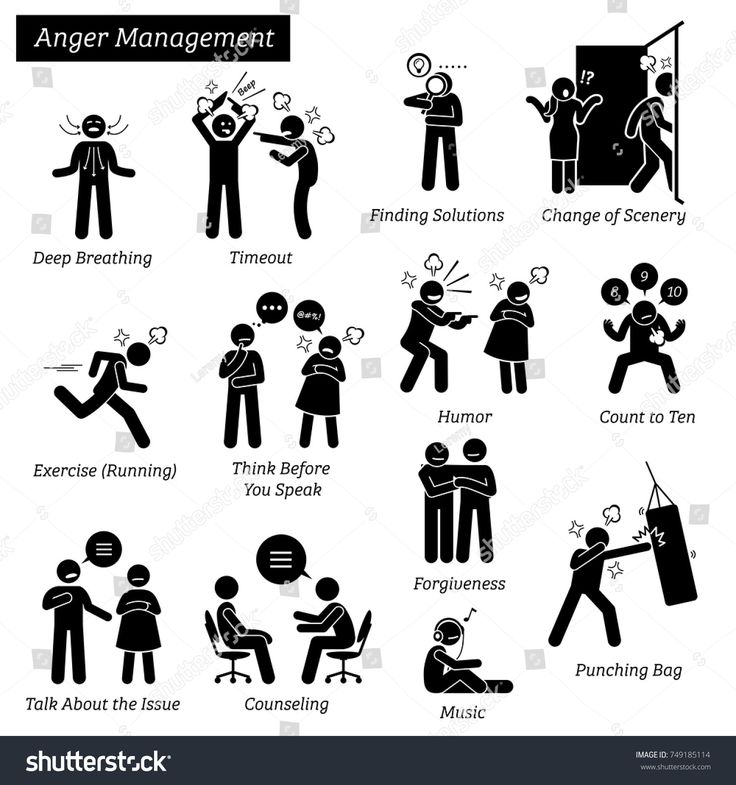

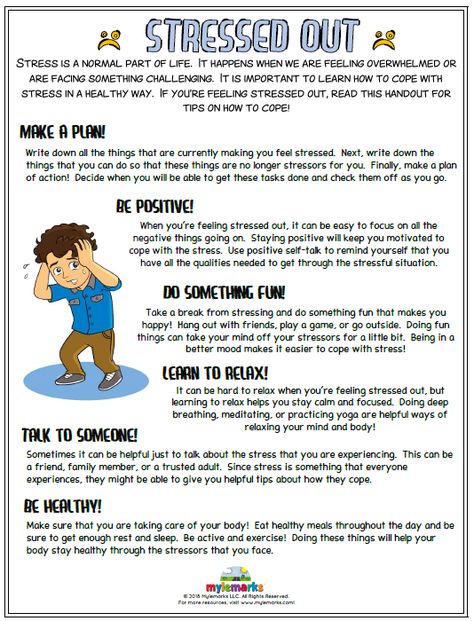

Anger tips for your child

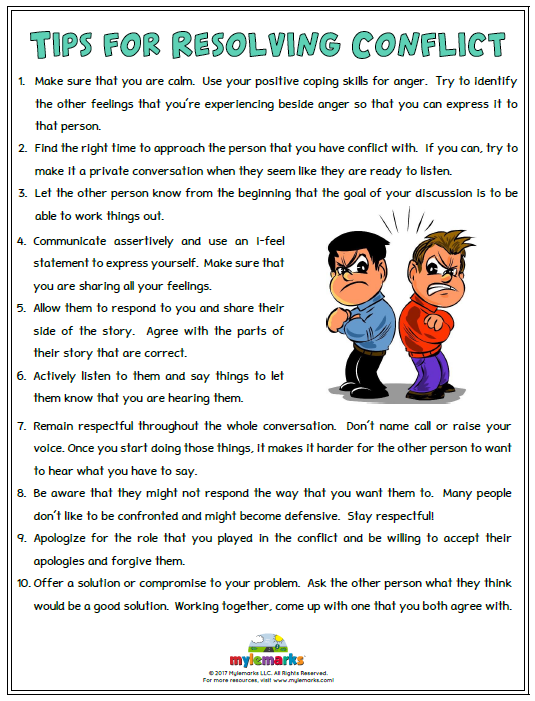

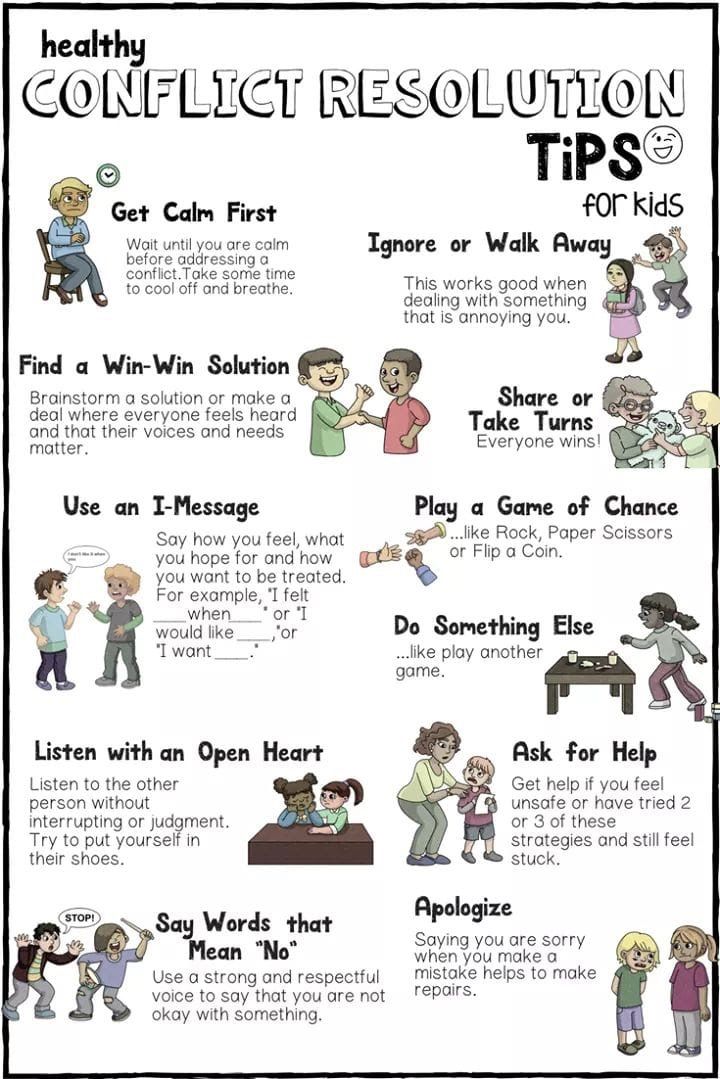

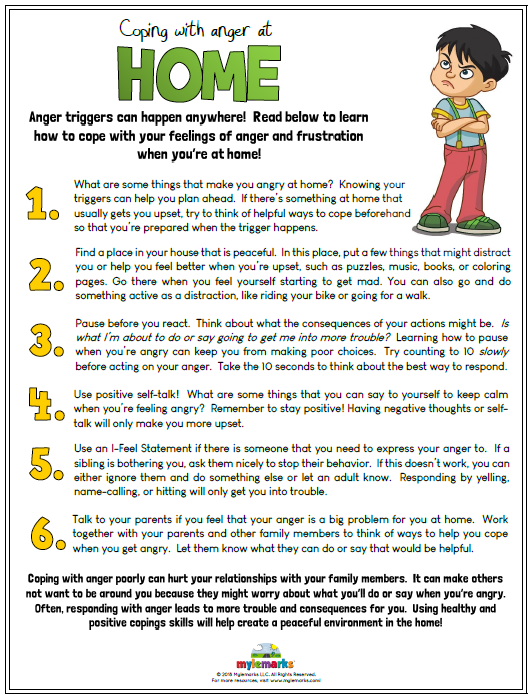

Work together to try to find out what triggers the anger. Talk about helpful strategies for managing anger.

You could encourage your child to:

- count to 10

- walk away from the situation

- breathe slowly and deeply

- clench and unclench their fists to ease tension

- talk to a trusted person

- go to a private place to calm down

If you see the early signs of anger in your child, say so. This gives them the chance to try their strategies.

This gives them the chance to try their strategies.

Encourage regular active play and exercise

Staying active can be a way to reduce or stop feelings of anger. It can also be a way to improve feelings of stress, anxiety or depression,

For older children or young people, this could be simple activities, such as:

- a short walk

- jogging or running

- cycling

Read more about physical activity for children and young people.

Be positive

Positive feedback is important. Praise your child's efforts and your own efforts, no matter how small.

This will build your child's confidence in their ability to manage their anger. It will also help them feel that you're both learning together.

It will also help them feel that you're both learning together.

When to seek help for anger in children

If you're concerned your child's anger is harmful to them or people around them, you could talk to a:

- GP

- health visitor

- school nurse

If necessary, a GP may refer your child to a local children and young people's mental health service (CYPMHS) for specialist help.

CYPMHS is used as a term for all services that work with children and young people who have difficulties with their emotional or behavioural wellbeing.

You may also be able to refer your child yourself without seeing a GP.

Read more about accessing mental health services.

Further help and support for anger in children

For more support with anger in children, you could phone the YoungMinds parents' helpline free on 0808 802 5544 (9. 30am to 4.00pm, Monday to Friday).

30am to 4.00pm, Monday to Friday).

Other sources of help and support include:

- YoungMinds: parent's guide to responding to anger

- YoungMinds: information for children about dealing with anger

- MindEd for families: anger and aggression in children

If you have older children, find out more about talking to teenagers and coping with your teenager.

The Health for Teens website also has more about anger management

Page last reviewed: 11 February 2020

Next review due: 11 February 2023

Anger Management for Kids & How to Deal With Anger

When a child—even a small child—melts down and becomes aggressive, they can pose a serious risk to themselves and others, including parents and siblings.

It’s not uncommon for kids who have trouble handling their emotions to lose control and direct their distress at a caregiver, screaming and cursing, throwing dangerous objects, or hitting and biting. It can be a scary, stressful experience for you and your child, too. Children often feel sorry after they’ve worn themselves out and calmed down.

It can be a scary, stressful experience for you and your child, too. Children often feel sorry after they’ve worn themselves out and calmed down.

So what are you to do?

It’s helpful to first understand that behavior is communication. A child who is so overwhelmed that they are lashing out is a distressed child. They don’t have the skill to manage their feelings and express them in a more mature way. They may lack language, or impulse control, or problem-solving abilities.

Sometimes parents see this kind of explosive behavior as manipulative. But kids who lash out are usually unable to handle frustration or anger in a more effective way—say, by talking and figuring out how to achieve what they want.

Nonetheless, how you react when a child lashes out has an effect on whether they will continue to respond to distress in the same way, or learn better ways to handle feelings so they don’t become overwhelming. Some pointers:

- Stay calm. Faced with a raging child, it’s easy to feel out of control and find yourself yelling at them.

But when you shout, you have less chance of reaching them. Instead, you will only be making them more aggressive and defiant. As hard as it may be, if you can stay calm and in control of your own emotions, you can be a model for your child and teach them to do the same thing.

But when you shout, you have less chance of reaching them. Instead, you will only be making them more aggressive and defiant. As hard as it may be, if you can stay calm and in control of your own emotions, you can be a model for your child and teach them to do the same thing.

- Don’t give in. Don’t encourage them to continue this behavior by agreeing to what they want in order to make it stop.

- Praise appropriate behavior. When they have calmed down, praise them for pulling themselves together. And when they do try to express their feelings verbally, calmly, or try to find a compromise on an area of disagreement, praise them for those efforts.

- Help them practice problem-solving skills. When your child is not upset is the time to help them try out communicating their feelings and coming up with solutions to conflicts before they escalate into aggressive outbursts. You can ask them how they feel, and how they think you might solve a problem.

- Time outs and reward systems. Time outs for nonviolent misbehavior can work well with children younger than 7 or 8 years old. If a child is too old for time outs, you want to move to a system of positive reinforcement for appropriate behavior—points or tokens toward something they want.

- Avoid triggers. Vasco Lopes, PsyD, a clinical psychologist, says most kids who have frequent meltdowns do it at very predictable times, like homework time, bedtime, or when it’s time to stop playing, whether it’s Legos or the Xbox. The trigger is usually being asked to do something they don’t like, or to stop doing something they do like. Time warnings (“we’re going in 10 minutes”), breaking tasks down into one-step directions (“first, put on your shoes”), and preparing your child for situations (“please ask to be excused before you leave Grandma’s table”) can all help avoid meltdowns.

What kind of tantrum is it?

How you respond to a tantrum also depends on its severity. The first rule in handling nonviolent tantrums is to ignore them as often as possible, since even negative attention, like telling the child to stop, can be encouraging.

The first rule in handling nonviolent tantrums is to ignore them as often as possible, since even negative attention, like telling the child to stop, can be encouraging.

But when a child is getting physical, ignoring is not recommended since it can result in harm to others as well as your child. In this situation, Dr. Lopes advises putting the child in a safe environment that does not give them access to you or any other potential rewards.

If the child is young (usually 7 or younger), try placing them in a time out chair. If they won’t stay in the chair, take them to a backup area where they can calm down on their own without anyone else in the room. Again, for this approach to work there shouldn’t be any toys or games in the area that might make it rewarding.

Your child should stay in that room for one minute, and must be calm before they are allowed out. Then they should come back to the chair for time out. “What this does is gives your child an immediate and consistent consequence for their aggression and it removes all access to reinforcing things in their environment,” explains Dr. Lopes.

Lopes.

If you have an older child who is being aggressive and you aren’t able to carry them into an isolated area to calm down, Dr. Lopes advises removing yourself from their vicinity. This ensures that they are not getting any attention or reinforcement from you and keeps you safe. In extreme instances, it may be necessary to call 911 to ensure your and your child’s safety.

Help with behavioral techniques

If your child is doing a lot of lashing out—enough that it is frequently frightening you and disrupting your family—it’s important to get some professional help. There are good behavioral therapies that can help you and your child get past the aggression, relieve your stress and improve your relationship. You can learn techniques for managing their behavior more effectively, and they can learn to rein in disruptive behavior and enjoy a much more positive relationship with you.

- Parent-child interaction therapy. PCIT has been shown to be very helpful for children between the ages of 2 and 7.

The parent and child work together through a set of exercises while a therapist coaches parents through an ear bud. You learn how to pay more attention to your child’s positive behavior, ignore minor misbehaviors, and provide consistent consequences for negative and aggressive behavior, all while remaining calm.

The parent and child work together through a set of exercises while a therapist coaches parents through an ear bud. You learn how to pay more attention to your child’s positive behavior, ignore minor misbehaviors, and provide consistent consequences for negative and aggressive behavior, all while remaining calm.

- Parent Management Training. PMT teaches similar techniques as PCIT, though the therapist usually works with parents, not the child.

- Collaborative and Proactive Solutions. CPS is a program based on the idea that explosive or disruptive behavior is the result of lagging skills rather than, say, an attempt to get attention or test limits. The idea is to teach children the skills they lack to respond to a situation in a more effective way than throwing a tantrum.

Figuring out explosive behavior

Tantrums and meltdowns are especially concerning when they occur more often, more intensely, or past the age in which they’re developmentally expected—those terrible twos up through preschool. As a child gets older, aggression becomes more and more dangerous to you, and the child. And it can become a big problem for them at school and with friends, too.

As a child gets older, aggression becomes more and more dangerous to you, and the child. And it can become a big problem for them at school and with friends, too.

If your child has a pattern of lashing out it may be because of an underlying problem that needs treatment. Some possible reasons for aggressive behavior include:

- ADHD: Kids with ADHD are frustrated easily, especially in certain situations, such as when they’re supposed to do homework or go to bed.

- Anxiety: An anxious child may keep their worries secret, then lash out when the demands at school or at home put pressure on them that they can’t handle. Often, a child who “keeps it together” at school loses it with one or both parents.

- Undiagnosed learning disability: When your child acts out repeatedly in school or during homework time, it could be because the work is very hard for them.

- Sensory processing issues: Some children have trouble processing the information they are taking in through their senses.

Things like too much noise, crowds and even “scratchy” clothes can make them anxious, uncomfortable, or overwhelmed. That can lead to actions that leave you mystified, including aggression.

Things like too much noise, crowds and even “scratchy” clothes can make them anxious, uncomfortable, or overwhelmed. That can lead to actions that leave you mystified, including aggression.

- Autism: Children on all points of the spectrum are often prone to major meltdowns when they are frustrated or faced with unexpected change. They also often have sensory issues that make them anxious and agitated.

Given that there are so many possible causes for emotional outbursts and aggression, an accurate diagnosis is key to getting the help you need. You may want to start with your pediatrician. They can rule out medical causes and then refer you to a specialist. A trained, experienced child psychologist or psychiatrist can help determine what, if any, underlying issues are present.

When behavioral plans aren’t enough

Professionals agree, the younger you can treat a child, the better. But what about older children and even younger kids who are so dangerous to themselves and others, behavioral techniques aren’t enough to keep them, and others around them, safe?

- Medication.

Medication for underlying conditions such as ADHD and anxiety may make your child more reachable and teachable. Kids with extreme behavior problems are often treated with antipsychotic medications like Risperdal or Abilify. But these medications should be partnered with behavioral techniques.

Medication for underlying conditions such as ADHD and anxiety may make your child more reachable and teachable. Kids with extreme behavior problems are often treated with antipsychotic medications like Risperdal or Abilify. But these medications should be partnered with behavioral techniques. - Holds. Parent training may, in fact, include learning how to use safe holds on your child, so that you can keep both them and yourself out of harm’s way.

- Residential settings. Children with extreme behaviors may need to spend time in a residential treatment facility, sometimes, but not always, in a hospital setting. There, they receive behavioral and, most likely, pharmaceutical treatment. Therapeutic boarding schools provide consistency and structure round the clock, seven days a week. The goal is for the child to internalize self-control so they can come back home with more appropriate behavior with you and the world at large.

- Day treatment.

With day treatment, a child with extreme behavioral problems lives at home but attends a school with a strict behavioral plan. Such schools should have trained staff prepared to safely handle crisis situations.

With day treatment, a child with extreme behavioral problems lives at home but attends a school with a strict behavioral plan. Such schools should have trained staff prepared to safely handle crisis situations.

Explosive children need calm, confident parents

It can be challenging work for parents to learn how to handle an aggressive child with behavioral approaches, but for many kids it can make a big difference. Parents who are confident, calm, and consistent can be very successful in helping children develop the skills they need to regulate their own behavior.

This may require more patience and willingness to try different techniques than you might with a typically developing child, but when the result is a better relationship and happier home, it’s well worth the effort.

Video Resources for Kids

Teach your kids mental health skills with video resources from The California Healthy Minds, Thriving Kids Project.

Start Watching

How to help your child cope with anger

In my work as a school counselor, I most often encounter a tendency to increase aggression and anger in almost all children. Whether we dare to admit it or not, the constant pressure to depict violence on television, in video games, on the Internet, in films, in music, and in our newspapers, is harming our children. As a result, too many children become insensitive to violence and begin to believe that anger is the only way to solve problems.

Whether we dare to admit it or not, the constant pressure to depict violence on television, in video games, on the Internet, in films, in music, and in our newspapers, is harming our children. As a result, too many children become insensitive to violence and begin to believe that anger is the only way to solve problems.

Although this may be considered bad news, there is good news: you can learn not only violence, but also calmness! Here are six secrets that will help your child learn a calmer, more constructive way to express their anger. These ideas have been presented in my consultations to hundreds of parents, and the response has been positive: they are simple methods, and if applied consistently, they will work. Teaching our children these techniques is the best way to prevent the aggressive behavior that so many children suffer from today. Here are six ideas to get you started.

1. Be calm. The best way to teach your child how to deal constructively with anger is to show him your own example. After all, you yourself learned to calm down, not by reading about it in a book, but by seeing how others do it. So use this annoying experience as "lessons in place" to teach your child to calm down.

After all, you yourself learned to calm down, not by reading about it in a book, but by seeing how others do it. So use this annoying experience as "lessons in place" to teach your child to calm down.

For example, let's say your auto repair shop calls you and tells you that the cost of repairing your car will double. You are annoyed by this message, but your child is standing nearby, who is watching you carefully. Gather as much calmness as you can and use this situation as an object lesson in anger management: "I'm so angry right now," you say calmly to your child. "The body shop just doubled the cost of fixing my car." And after that, a soothing solution is offered: "We need to take a walk in order to recover." It is your example that the child will copy.

2. Get out and calm down. One of the most difficult aspects of parenting has to do with children directing their anger at you. If you're not careful, you'll find that their anger will fuel your emotions that you didn't know you had. Be careful: anger is contagious. It is best to establish a rule in your house from the very beginning: "In this house we solve problems when we are calm and in control." And then steadily follow this rule.

Be careful: anger is contagious. It is best to establish a rule in your house from the very beginning: "In this house we solve problems when we are calm and in control." And then steadily follow this rule.

Here is an example of how you can use this. The next time your child gets angry and demands a quick solution, you can say, "I need a break. Let's talk about this later," and then calmly walk out without responding to the child's reaction. A mother came to me for counseling and told me that the only way for her to leave was to lock herself in the closet. The child continued to scream and kick the door, but she did not come out until he calmed down. It took several times to apply this approach, so that it dawned on the child that she was talking seriously. From that moment on, the child understood that his mother would discuss the problem with him only when he was calm and able to keep his feelings under control.

3. Build a vocabulary of words that describe feelings. Many children show anger only because they simply do not know how to express their irritation in another way. Kicking, screaming, swearing, hitting or throwing things may be the only way they know how to express their feelings. It is pointless to ask a child, "Tell me how you feel right now?", as he may not know the right words to describe his feelings. To help him verbally express his anger, create a list of words that describe feelings by asking him, "Let's think of all the words we can use to tell the other person we're really angry," and write down his ideas.

Many children show anger only because they simply do not know how to express their irritation in another way. Kicking, screaming, swearing, hitting or throwing things may be the only way they know how to express their feelings. It is pointless to ask a child, "Tell me how you feel right now?", as he may not know the right words to describe his feelings. To help him verbally express his anger, create a list of words that describe feelings by asking him, "Let's think of all the words we can use to tell the other person we're really angry," and write down his ideas.

For example, you could use words such as "anger", "fierce", "irritation", "fury", "displeasure", "rage". Write them down on a card, hang it on the wall, and try to use them. When your child gets angry, use these words so he can apply them in real life. "Looks like you're really angry. Do you want to talk about it?" Or "You look annoyed. Would you like to tell me what happened?" Keep adding new emotion words to this list each time such a new word appears in these "learning moments" throughout the day.

4. Make a calming poster. There are dozens of ways to help kids calm down when they get irritated. Unfortunately, many children are not given the opportunity to think about these possibilities. That is why they have problems. After all, the only behavior they know is the wrong way to express their own displeasure. Therefore, talk to your child about more acceptable "substitutes" for this behavior. You can make a great poster by listing them on it. Here are a few ideas fourth graders thought of: go away, think of a calming place, listen to music, hit a pillow, draw, talk to someone, sing a song. After the child chooses the "calming" method, encourage him to use the same strategy every time he gets angry.

5. Identify signs of early detection of anger. Explain to your child that we all have signals in our bodies that warn us when we get angry. We need to listen to these signals, as they keep us out of trouble. Then, help your child recognize what specific warning signals are telling them that they are getting angry. For example, "I speak louder, my cheeks start to burn, I clench my fists, my heart beats faster, my lips dry, I breathe faster." Once your child is aware of these signals, point them out at the first sign of irritation. "Look, it looks like you're starting to lose control," or "Your fists are clenched. Don't you think you're starting to get angry?" The more we help children learn to recognize these early signs of impending anger, the better they will be able to calm themselves. The appearance of the first signals is the time when the anger management strategy is most effective. Anger develops very quickly, and if you wait for the child to "melt", then it is too late to try to calm him down later.

For example, "I speak louder, my cheeks start to burn, I clench my fists, my heart beats faster, my lips dry, I breathe faster." Once your child is aware of these signals, point them out at the first sign of irritation. "Look, it looks like you're starting to lose control," or "Your fists are clenched. Don't you think you're starting to get angry?" The more we help children learn to recognize these early signs of impending anger, the better they will be able to calm themselves. The appearance of the first signals is the time when the anger management strategy is most effective. Anger develops very quickly, and if you wait for the child to "melt", then it is too late to try to calm him down later.

6. Teach your child anger management strategies. A very effective strategy for helping a child calm down is called "3 + 10". You can even write this formula on large sheets of paper and hang them around your house. Then explain to the child how to use this formula. "As soon as you feel like your body is sending you a warning signal that you're starting to lose control, do two things. First, take three deep, slow breaths into your belly. That's a 3. Then count to ten silently. It'll be 10. Together, it's 3+10 and it will help you calm down." It is necessary at the same time to show the child how to take deep and slow breaths.

First, take three deep, slow breaths into your belly. That's a 3. Then count to ten silently. It'll be 10. Together, it's 3+10 and it will help you calm down." It is necessary at the same time to show the child how to take deep and slow breaths.

Teaching children how to deal successfully with their anger is not an easy task, especially if they have previously used only aggressive display of their own irritation. Experts say that learning a new behavior requires at least 21 days of repetition. Based on this, I can recommend the following. Choose one technique that should be most successful for your child and use it every day for 21 days. Your child is much more likely to actually learn a new technique as they try to use it over and over again, which is how we learn new experiences. It is also the best way to deal with violence and help our children live more successful, peaceful lives.

-----------------

author: Michele Borba

source: "Parents"

How to help a child cope with anger?

Everyone experiences feelings of anger sometimes, including children. And that's okay. Feeling emotions is completely natural. And children, the younger they are, the more they react to the situation emotionally, and not rationally (“in an adult way”). And it must be admitted that the strong anger of the child and the accompanying behavior (shouting, throwing objects, falling on the floor) often confuses parents.

And that's okay. Feeling emotions is completely natural. And children, the younger they are, the more they react to the situation emotionally, and not rationally (“in an adult way”). And it must be admitted that the strong anger of the child and the accompanying behavior (shouting, throwing objects, falling on the floor) often confuses parents.

It is often difficult for children to cope with strong emotions and formulate in words the state they are in, so they can and should be taught this. It is important to understand that “coping” is not about “suppressing” or “denying” emotions. The task of adults is to help the child understand himself, to realize that experiencing anger is natural, but it must be done without harming others, in a socially acceptable way.

So how do you help a child cope with anger? Let's take this situation as an example:

A child of 4-5 years old plays on the playground. Mom comes up and says it's time to go home. The child does not react, the mother has to take away his toys, he gets very angry in response, starts shouting to the whole playground “Give it back! You are bad!" etc. , with one hand he tries to take away toys, with the other - to beat his mother.

, with one hand he tries to take away toys, with the other - to beat his mother.

In such a situation, the first thing to do is to remain calm yourself. Then, give the child time to calm down and/or help him with this. Say his feelings out loud (do it in an affirmative, not a question form, for example: “I see that you are very angry / angry / annoyed that I took your toys, and that we need to leave the playground, and you would like to play more ”) or “You really enjoyed playing on the court, and when I approached you, you were not ready to leave. But it was time to go home and I had to pick up the toys. You got very angry when I took them away, and it was so difficult for you to cope with this state that you started to beat me and scream at me.

You may ask: "Why talk about feelings?". Firstly, it helps the child feel that you understand what is happening to him, you hear him. Secondly, it is not obvious to the child how to name what he experiences. At the same time, there are studies that show that speaking out loud about your emotional state increases the ability to control your behavior.

Next, talk to your child about how to behave in such situations and suggest alternative ways of expressing anger and anger. For example: “You have the right to be angry, all people get angry sometimes, but you can’t offend others and fight. Let's think about what you can do when you're angry to make it easier for you?

Here are some socially acceptable behaviors that can help a child deal with anger:

- Express your emotions in words. “I’m angry!”, “I want to hit you”, “I’m so angry that I can hardly restrain myself from hitting you”, etc. You can suggest that the child try to practice and play the situation with him in different roles.

- Breathe consciously. You can tell your child that slow and deep breathing is relaxing. Explain that when he feels very angry, he can take a few slow deep breaths in and out. Practice doing this exercise with him.

- Exercise. Running, squatting, push-ups, cycling, jumping rope - any activity that brings pleasure to the child.

Of course, you should not expect that after one conversation the child will immediately begin to control his behavior and use all the methods that you suggested. Treat it more like forming any other skill or habit - in order for them to become an integral part of life, they need repeated repetition and time.

And here is what you should not do in any case:

Respond with aggression to aggression. So you will only reinforce the child's behavior, show him an example of unacceptable behavior, perhaps scare him, but will not help in the development of emotional regulation. After all, it is strange when they tell you not to do this, but they themselves do exactly that.

Saying you shouldn't be angry. The ban on emotion, which leads to its suppression, may later manifest itself in psychosomatic symptoms.

Take offense. If you tell a child that you are offended by him, this may make him feel guilty, but it certainly will not help to teach him to behave constructively in moments of anger.