How to help a lonely child

How to Help Kids Who Are Lonely

We all want our children to be socially successful. While they don’t need to be the most popular kid in the class, we do hope that they will have friends.

Friendships are one of the biggest sources of fun in a kid’s life, which is reason enough to value them. But they are also critical to development. They lay the groundwork for lifelong skills like listening to others, solving problems and self-expression. They are also an important source of confidence. As kids get older their friendships start playing an even bigger role in their emotional and personal lives.

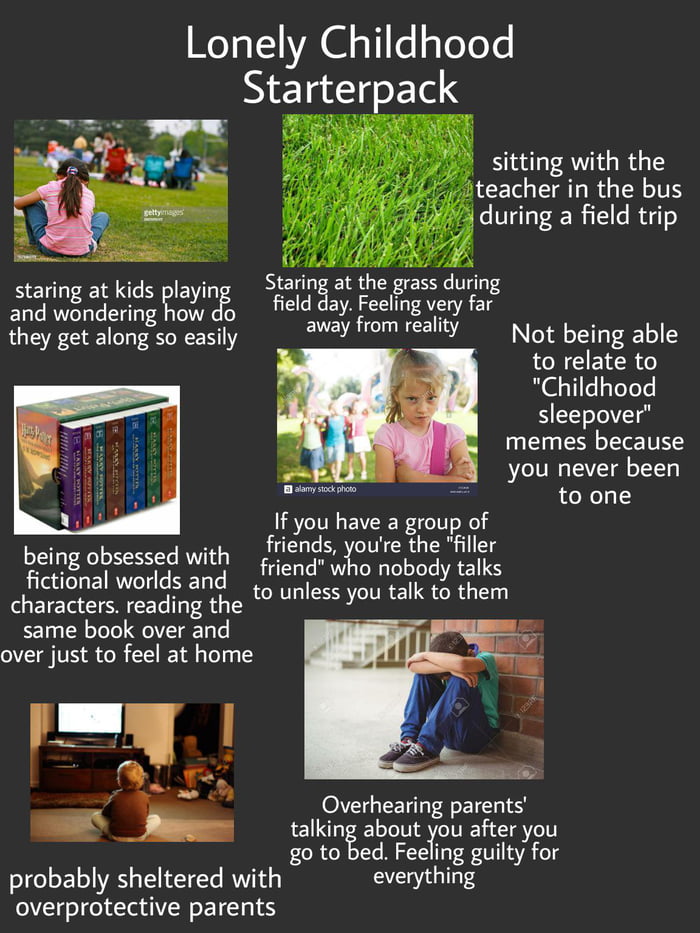

When kids don’t have these relationships, it can have a serious impact on their mood, confidence and functioning. Going to school every day can be a trial. Using social media can be depressing. Kids who are lonely often feel rejected, invisible or like something is wrong with them. And parents watching from the sidelines wonder what they can do to help.

It hurts when you see that your child isn’t making friends, and you can’t figure out why — or how to help. Here are some potential reasons why a child may be striking out on connecting with other kids:

They don’t understand how to socialize. The rules of social interaction might seem obvious to you, but they do need to be learned. And while most kids pick up social cues and patterns so easily it seems automatic, some don’t, and need more support — and practice. This is particularly true for kids with ADHD, autism and non-verbal learning disorder. When one child isn’t understanding their peers’ expectations about how to decide what to play, how to share, when to talk and how to show that they’re listening, they’re going to find it harder to make friends.

They’re anxious. It is common for kids — and adults — to feel anxiety when they come into a new social situation or join a group. This shows up in young kids who can’t join in activities on the playground, or at birthday parties that are supposed to be fun but are actually overwhelming. Social anxiety gets more common as kids get older. Some kids with severe social anxiety may be paralyzed with worry that others are judging them. They might weigh every word in a text message and worry so much about how they look or what they say that they stop hanging out with friends. They may be so self-conscious they even stop eating in the school cafeteria.

Some kids with severe social anxiety may be paralyzed with worry that others are judging them. They might weigh every word in a text message and worry so much about how they look or what they say that they stop hanging out with friends. They may be so self-conscious they even stop eating in the school cafeteria.

They’re depressed. A major symptom of depression is a tendency to withdraw from others. While they might have fun with friends once they’re hanging out, a kid with depression will first need to be compelled to leave their room. Kids who are depressed are also more likely to interpret things negatively and assume other people don’t want to see them.

They don’t “fit in.” For some children, the problem is more environmental. “Something we talk about with some kids is the idea of being a rose in a tulip garden,” says Lauren Allerhand, PsyD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute. “So maybe it’s not a lack of skills, but you’re just in an environment where people don’t have the same ideas or interests as you, and you’re just having a real challenge finding your group of people. ”

”

They’re immature. Kids may struggle to fit in when they are younger than their classmates or just slower to mature. They might not have developed the same social skills as their peers yet, or they might just have different interests. As kids get older they tend to catch up, but in the meantime they may be feeling confused and lonely.

How to tell if your child is lonely

When kids spend a lot of time alone, you might suspect they are lonely. But unless they complain that they don’t have friends or are obviously unhappy, parents can be left to wonder how much it’s upsetting them.

Kids might not volunteer to discuss it with you. This is particularly the case with teenagers, but kids of all ages might feel some reluctance about admitting how they feel. It can help if you start the conversation by talking about times in your life when you have felt lonely, says Dr. Allerhand. “Sharing a little bit can open the door for kids to express some of what they’re feeling. But I wouldn’t push too hard. If they don’t want to tell you, give it a try again in the next day or two.”

But I wouldn’t push too hard. If they don’t want to tell you, give it a try again in the next day or two.”

Other kids, especially very young children and kids on the spectrum, might not know how to explain what they’re feeling. “For individuals with autism, sometimes communicating their own experiences can be quite challenging. They often can have a hard time linking what they’re feeling and what their experience is with a specific word that others may use for that experience,” says Bethany Vibert, PsyD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute. When asked point blank if they are lonely an autistic child might say no, but if you probed a little deeper you might find that they do actually wish they had friends.

For kids who are younger or struggle with emotion identification, first teaching what loneliness is can help. Sharing your own experience of feeling lonely is also a good strategy here. Dr. Vibert recommends that you might say something simple like, “When I haven’t been around people for a while, sometimes I want to spend time with somebody. That means I’m feeling lonely.” Dr. Vibert also suggests asking kids what they’d want to do if they could be doing anything. What they have to say could give you clues about what they might be missing out on.

That means I’m feeling lonely.” Dr. Vibert also suggests asking kids what they’d want to do if they could be doing anything. What they have to say could give you clues about what they might be missing out on.

What to say (and what not to say)

As parents we often want to immediately jump into problem solving mode whenever our child is having an issue. But it’s a better idea to slow down and just listen to what your kid has to say, first. Giving kids the space to open up and feel heard lets them know that it’s okay to talk about emotions — and that you’re a good person to turn to whenever they need help. For kids who might be feeling rejected or invisible, showing that you care will also be particularly meaningful to them. Waiting to hear more will help you be more supportive later, too. “If we don’t give them space to just talk, we might be coming up with a solution that’s not really a good fit for the actual problem,” points out Dr. Vibert.

Here are some strategies for a good conversation:

Ask open-ended questions. For example, if your child says they miss spending time with someone they used to see a lot, you can ask questions about that. “What did you really like doing with her? What do you miss the most about seeing her?”

For example, if your child says they miss spending time with someone they used to see a lot, you can ask questions about that. “What did you really like doing with her? What do you miss the most about seeing her?”

Make observations. Sometimes comments are a good alternative to questions. So, if you notice that your child isn’t spending time with people as much as they used to, you might point that out. Then leave space for them to talk.

Validate their experiences. Showing genuine interest goes a long way. Do your best to listen without judgment (or visible panic) to whatever they have to say. Try also to avoid overreacting with too much sympathy or emotion, since that might make them feel even worse. You can show that you’re listening by reflecting back what they’re saying (“It sounds like you’re having a hard time”), or saying supportive things like “That sounds tough. Would you tell me more about that?”

Make a plan. When something is confusing or intimidating it is often helpful to break it into smaller steps. So if your child is struggling to ask someone if they want to hang out, for example, you can work with them to come up with a plan for how to do it. Dr. Vibert recommends having a plan A and a plan B just in case. “If the child is already feeling lonely and then they’re putting themselves in a vulnerable position to reach out to somebody, I think it’s helpful for a parent to have them work through what to do if it doesn’t work out.” Having a plan B can help kids feel more confident going in, too.

When something is confusing or intimidating it is often helpful to break it into smaller steps. So if your child is struggling to ask someone if they want to hang out, for example, you can work with them to come up with a plan for how to do it. Dr. Vibert recommends having a plan A and a plan B just in case. “If the child is already feeling lonely and then they’re putting themselves in a vulnerable position to reach out to somebody, I think it’s helpful for a parent to have them work through what to do if it doesn’t work out.” Having a plan B can help kids feel more confident going in, too.

Practice social skills. For kids who are struggling with their social skills, try to give them plenty of opportunity to practice at their own pace in a supportive environment. Coach your child on the things they find challenging — maybe settling conflict, taking turns or noticing when someone is losing interest in an activity — and try role playing to give them experience. Relatives and family friends can also help so they get practice with multiple people.

Relatives and family friends can also help so they get practice with multiple people.

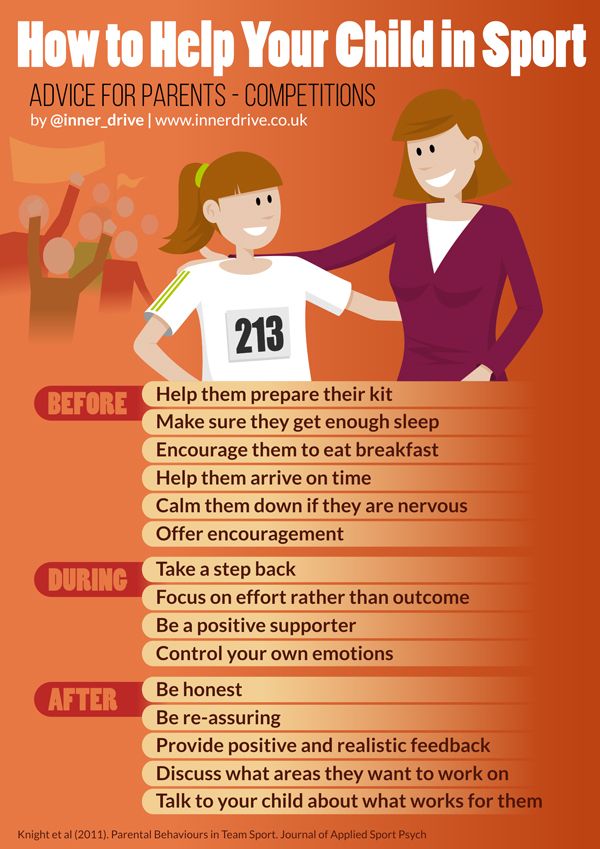

Give encouragement. Kids who are feeling anxious or depressed are less inclined to put themselves out there. “When kids say they want to stay home, it’s a challenge to figure out how much to push,” acknowledges Michelle Kaplan, LCSW, a licensed social worker. “But generally, kids are able to reflect afterward that ‘Oh, that was a little less awkward than I thought,’ or ‘I had more fun than I thought I was going to.’” Validate how kids are feeling by acknowledging that going to see people might be difficult for them. Then remind them that they’re probably going to have a good time once they’re there and offer lots of support and praise for doing something challenging.

Give a reality check. Kids can sometimes struggle socially because they are prone to misunderstanding situations. This is especially easy to do with text messages, big group chats, and social media. Kids who are depressed are also more prone to interpreting things negatively even when it isn’t warranted. Dr. Allerhand has worked with teens on maintaining relationships and says that helping kids “check the facts” on a situation is important. “I think a lot of teenagers are self-focused, so they think if a relationship has fallen off, it’s because of something they’ve done. But maybe there are other interpretations.” Dr. Allerhand recommends talking it through: “‘Okay, so you haven’t spoken with Jimmy in a while. Do you have any evidence that he’s mad at you? Could there be any other reasons why you haven’t talked?’”

Kids who are depressed are also more prone to interpreting things negatively even when it isn’t warranted. Dr. Allerhand has worked with teens on maintaining relationships and says that helping kids “check the facts” on a situation is important. “I think a lot of teenagers are self-focused, so they think if a relationship has fallen off, it’s because of something they’ve done. But maybe there are other interpretations.” Dr. Allerhand recommends talking it through: “‘Okay, so you haven’t spoken with Jimmy in a while. Do you have any evidence that he’s mad at you? Could there be any other reasons why you haven’t talked?’”

For kids who tend to interpret things negatively a lot, helping them notice that tendency, and reminding them when they’re doing it, can help them break the pattern.

Look elsewhere for friendships. When kids just aren’t fitting in, they might be looking in the wrong places. “Maybe they’ve done a lot of sports groups before, but they’re not actually into sports,” points out Kaplan. Try to find a group or activity that is more interesting to them. Getting involved in something they genuinely find exciting will also likely improve their confidence and sense of self-worth.

Try to find a group or activity that is more interesting to them. Getting involved in something they genuinely find exciting will also likely improve their confidence and sense of self-worth.

Many kids also find success turning to the internet to explore niche interests or just connect with a larger pool of kids. “One positive thing to come out of the pandemic is there are more and more virtual groups for kids to come online and meet with other kids that have similar interests to them,” says Kaplan.

But if your child does turn to the internet, make sure they stay safe. “Children with autism and developmental disabilities may have more difficulty determining if a situation is dangerous,” notes Dr. Vibert. “It’s very important that parents be not only involved, but proactive in providing education to their child about safety and danger online.”

How to evaluate screen time

If you’re worried that all your child seems to want to do is stare at a screen, keep in mind that screens have become a major way that kids interact with each other. While they don’t make up for in-person socializing, your child may be socializing more than you realize. Thanks to social media kids are often in closer communication with their peers than parents realize. Video games can also be a lot more social than they may initially seem.

While they don’t make up for in-person socializing, your child may be socializing more than you realize. Thanks to social media kids are often in closer communication with their peers than parents realize. Video games can also be a lot more social than they may initially seem.

“I often suggest that parents sit by kids while they’re playing games and try to gauge how much they’re connecting with peers,” Kaplan explains. “Don’t ask a ton of questions, but maybe you can ask things like: Is there anyone else you’re playing with? Who are those kids? What are you guys working on? Do you see those kids each time you play? Are there new kids that come on? These kinds of questions can help you assess how much socializing is happening.”

Some kids tend to be more comfortable socializing online and find a lot of fulfillment that way. But while the internet can be a lifesaver for kids who are struggling to fit in otherwise, socializing offline is still important. So if your child is struggling with in-person socialization, talking to a clinician who specializes in children’s mental health about how to get your child more comfortable with other people is important.

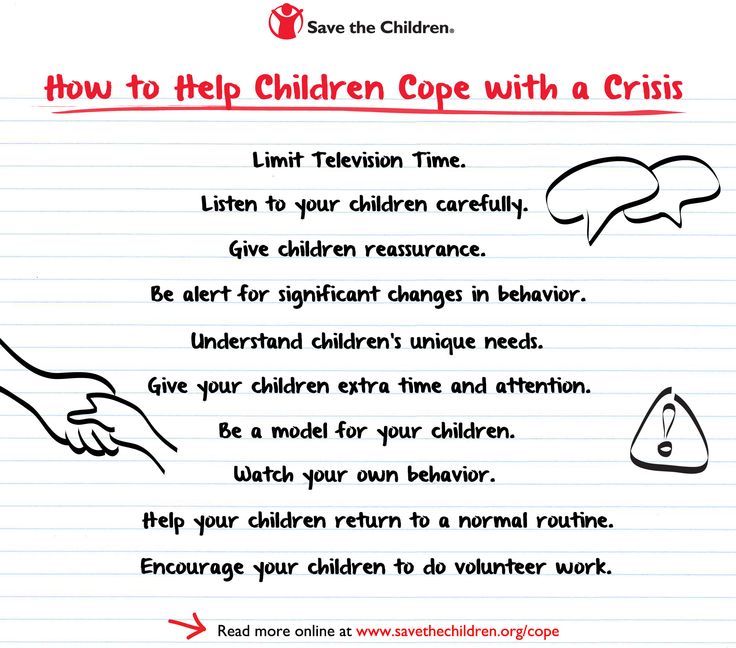

10 Ways Parents Can Be There For a Lonely Child

It’s hard out there for an isolated kid. If you have children in the 2-to-5-year-old age range, you’ve likely been without childcare for extended periods — whether that’s separation from your nanny, daycare, or even a grandparent. You’ve also probably stopped playdates, or cut way back; in many areas, children museums, zoos, and playgrounds have closed. Hosting or being hosted at other people’s houses is a big COVID no-no. In all likelihood you’ve worried about your lonely child and the impact the COVID pandemic has had on their mental health and social development.

So what are the signs of loneliness in children, what is and isn’t a cause of concern, and what can you do to help a lonely child? Here’s what you can do better understand the signs and to mitigate loneliness at home.

Signs of Loneliness in Young ChildrenYes, your child misses their friends and family members. “We used to think that infants and very young people didn’t form connections, but we know from research that they do,” says Jane Timmons-Mitchell, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University. “Kids may remember the names of their friends and give their stuffed animals or imaginary friends their real friends’ names.”

“Kids may remember the names of their friends and give their stuffed animals or imaginary friends their real friends’ names.”

Four- and five-year-olds may be able to talk about these feelings, though they might not explicitly call it loneliness. “Loneliness is a complex emotion,” says Dr. Polina Umylny, Assistant Director, Pediatric Behavioral Health Integration Program, Montefiore Medical Group and Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. “The words may be, ‘I miss Grandma,’ or ‘I wish I could go back to daycare or art class.’” Parents should keep an ear out for such phrases. As children express themselves through play, parents should also pay attention when their child is playing with stuffed animals or action figures.

For older children, loneliness may present itself as withdrawal. “One of the benefits of being with your kids more is you’ll have a better baseline, so you’ll know if there’s an increase in loneliness,” says Timmons-Mitchell. “They could be withdrawing from things they usually like to be doing, which could manifest as irritability. ” Timmons Mitchell says to look for them not doing or engaging in something they normally like to do, like playing games.

” Timmons Mitchell says to look for them not doing or engaging in something they normally like to do, like playing games.

Changes in behavior are also the primary sign of loneliness in younger children. “At two-to-three, they’re different from older kids cognitively,” says Rachel Annunziato, Professor of Psychology, Fordham University. “They’ll experience it more somatically with aches and pains, or they’ll be more irritable. Look for mood shifts — changes in their energy levels that indicate they’re out of sorts.”

As far as more serious issues, such as anxiety or depression, parents should be on the lookout for dramatic changes in behavior. Annunziato says to look at changes in eating and sleep habits a bit more seriously. “They could be indicative of other things, but if they’re more than transient, give a call to your pediatrician and ask, ‘Could this be some sort of manifestation of loneliness or stress?’”

Also, check for the severity of the behavior. “If the behavior is increasingly aggressive, for example, that’s a red flag,” Umylny says.

For the most part, no, you don’t need to worry if your young child is lonely. According to the experts we spoke to, kids ages 2-5 experience loneliness differently than older kids and adults — and aren’t likely to miss their friends and family members to a detrimental degree so long as they have you around.

“Children are resilient,” Annunziato says. “Even with long-term separation from their friends or preschool, they’ll bounce back when things start to reopen.”

In the long run, your kids aren’t missing out on anything developmentally they won’t get back. “They’ll develop interpersonal skills with their siblings and parents,” Umylny says. If your kids regress, like with potty training, she adds, don’t stress that this is a skill that they had a few months ago and lost — they’ll master it again.

“It’s hard to predict the impact of the past year on children — it’s unprecedented,” Umylny says. “It’s important that children aren’t entirely isolated and that they do have social interactions. They just won’t be at the same level as before.”

They just won’t be at the same level as before.”

The experts we spoke to assured us that what kids are missing out on in terms of time with friends and family is more than made up for by all the extra time they’re spending with you. All the same, there are a few things you can do to help your kids through this un-social time.

1. Prompt Them to Talk About Their Feelings

Gently encouraging your child to talk about their feelings gets them into the habit of putting their emotions into words and allows them to be heard. “Say, ‘I was thinking it’s been a long time since you’ve been with your friends,’” Umylny suggests. “’I wish we could go to their house the way we used to.’” She understands that parents may be reluctant to bring such topics up, fearing they’ll introduce emotions their child might not be feeling. But, she assures, it’s validating for children. “Let them know it’s okay to have those feelings and that they are loved and supported no matter what feelings they may have. ”

”

2. Normalize Their Loneliness

Speaking of validation, make sure your kids understand they’re not alone in missing their friends. “Saying they’re missing someone they can’t see — that makes perfect sense,” Timmons-Michell says. “Empathize with them.” Try saying: ‘Yes, there are people that I miss, too.’ Then link it to the positive. But ‘I’m really happy that we get to spend all this extra time together. Look at the cool things we’re doing!’ “Link it to something great you’re enjoying together,” Timmons-Mitchell says.

3. Schedule Virtual PlaydatesZoom and FaceTime can help connect your kids with their friends. Of course, how well they interact with other kids via screens depends on attention spans, tech-savviness, and age. “Some kids dive right in,” Annunziato says. “For other kids, it’s more giggling or playing with the device rather than interacting. We can pop in, or do a joint playdate with the parents, which can be helpful for us, too. ” How long the video conference sessions go will vary, but plan for half an hour and adjust timing as needed. Include plans for specific activities, like showing off toys or listening to a story together.

” How long the video conference sessions go will vary, but plan for half an hour and adjust timing as needed. Include plans for specific activities, like showing off toys or listening to a story together.

4. Schedule Calls and Video Calls with Relatives

As travel and visits with family have been severely curtailed this year, many kids miss their grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, to name a few. Make calls or video chats with family members a part of your weekly routine. “It’s something everyone can look forward to and can be a regular engagement,” Annunziato says. Remember that your older relatives are likely experiencing isolation and loneliness, too — they could benefit as much or more to hear from your kids (and you).

5. Have Them Send Letters and Cards

Go old school and connect with your children’s friends and family with mail. “There are all sorts of things that you can do for outreach,” Timmons-Mitchell says. “While you’re creating the letter or card, you can talk about who it is you’re making it for, what things your children like about them, what they remember about them, and what they can do together in the future. ”

”

As with calls to older relatives, sending letters and cards to people in isolation is an act of kindness. “Isolation is one of the toughest things about this year, with family members who can’t see their families,” Timmons-Mitchell says. “Target loneliness by having your children draw a picture and put it in a card — something that reaches out to others who are lonely now.”

6. Keep (or add) Structure, Routine, and Traditions

At this point, you’ve likely established new daily and weekly routines since COVID began. Given the ever-changing nature of COVID restrictions, it’s essential to be flexible with schedules — but do try to keep to regular routines, as children crave consistency. Keep mealtimes, nap or quiet times, and bedtimes roughly the same every day. “Regular schedules create structure and safety for kids,” Annunziato says.

The holidays are opportunities for traditions — and for creating new ones. “Parents may feel a lot of disappointment and guilt about not being able to provide the holiday experience they may want to,” Umylny says. “So establish new traditions for your family.” Seasonal activities include holiday baking and making ornaments — activities for you to unplug and give your kids your undivided attention.

“So establish new traditions for your family.” Seasonal activities include holiday baking and making ornaments — activities for you to unplug and give your kids your undivided attention.

All experts agreed that kids need physical activity and time outdoors for their well-being and emotional health. If a playdate at the park can be socially distanced and safe, great. But even just you and them kicking a ball back and forth or running around an empty baseball diamond will help you both feel better.

8. Take Care of Yourself

Your concerns about your children’s lack of social interaction are legitimate — and also a reflection of your feelings of isolation, possibly. “Parents are filling in the gaps in a lot of ways,” Annunziato says. “As parents, we need to make sure we’re taking care of ourselves to optimize our interactions with our children.”

“The most important thing for parents is to acknowledge it’s been an extraordinarily difficult year,” Umylny says. “You may be feeling the loss of a loved one, you may be scared about finances, you may feel a sense of hopelessness that we’ll never return to a pre-COVID world. Acknowledge what effects the last year have had on you. Children pick up on what their parents are feeling, if their parents are anxious or sad. Make sure you address your own struggles and get whatever mental health support you need.”

“You may be feeling the loss of a loved one, you may be scared about finances, you may feel a sense of hopelessness that we’ll never return to a pre-COVID world. Acknowledge what effects the last year have had on you. Children pick up on what their parents are feeling, if their parents are anxious or sad. Make sure you address your own struggles and get whatever mental health support you need.”

9. Worry Better

As part of self care, cut yourself some slack. “Just because your kids were seeing other kids five days a week at daycare doesn’t mean you need to plan five days’ worth of virtual playdates,” Timmons-Mitchell says. “Once a week, or once a month — it’s enough.

“It’s just too much, trying to do all the stuff you need to do for your job and be your child’s teacher and social director,” she notes. It’s helpful not to put undue expectations on yourself. Parents are questioning themselves and beating themselves up, but it’s important not to. “Your kids need you to be available, and you can’t be available if you’re worrying,” she adds. “As much as possible, be present and don’t worry.” If anything, set aside a specific 15 minutes to worry and then move on.

“As much as possible, be present and don’t worry.” If anything, set aside a specific 15 minutes to worry and then move on.

10. Focus on Gratitude and Helping Others

This year, it’s been easy to focus on all the things we haven’t been able to do. But for your kids’ development, set an example of focusing on gratitude. Ask your kids to mention one thing they’re grateful for as part of their bedtime routine. Then connect it with someone in need.

“It’s useful to teach kids to give back,” Timmons-Mitchell says. “It lets them know we’re all in this together, and that we can help someone who has more need. Food and toy drives may be limited right now, and money donations may not make sense to young children, but you could think about doing something for the grandparents in nursing homes — giving as a way to reduce the loneliness of other people.” Something like this, she says, generates a lot of energy. “It’s surprising how good it makes someone feel to do something good for other people. ”

”

How to help a child who feels lonely

home

Parents

How to raise a child?

How to help a child who feels lonely

- Tags:

- Expert advice

- 1-3 years

- 3-7 years

- 7-12 years old

- teenager

- child in society

- family

- parents

- family relationships

In the company of their peers, children who play or do their own thing stand out - this is how they unconsciously choose a comfort zone for themselves. They are not alone. If a person is pleased to be with himself, then this is not loneliness. If you want to communicate, but not with anyone - then trouble.

The first sensations associated with a feeling of loneliness come to children during periods when they drop out of their usual social circle, being separated from people close to them. This is the time when they start kindergarten, go to school or go to summer camp. And especially acutely - during conflicts that often arise in an unfamiliar team. The task of parents at this time is to teach children to share their experiences, to pronounce their feelings. It is this skill that can protect the child from neurosis and loneliness in the circle of peers. The child must be sure that his relatives really need him, that his interests, fantasies, dreams and feelings are important to them.

The task of parents at this time is to teach children to share their experiences, to pronounce their feelings. It is this skill that can protect the child from neurosis and loneliness in the circle of peers. The child must be sure that his relatives really need him, that his interests, fantasies, dreams and feelings are important to them.

Prerequisites for loneliness

Loneliness is a multifaceted phenomenon, and only one of them has a positive side: when it is dictated by a certain warehouse of a child's character. Such children are comfortable alone with themselves and the lack of communication is their voluntary choice. Everything else is a tragic story. Let's consider the possible reasons for this phenomenon.

1. Loneliness at home. Parents are busy, you can't go out alone. Even when adults are at home, you hear: “find yourself something to do” or “don’t interfere.” Children feel their uselessness and at the same time loneliness. If a child does not feel like a part of the family, part of the world around him, then it will be very difficult for him to establish contact with others. Loneliness is experienced differently if there is a loving family behind you.

Loneliness is experienced differently if there is a loving family behind you.

2. Choice of friends. Parents often force a child to be alone by constantly criticizing his friends and dictating with whom he can be friends and with whom he cannot. But everything is not so simple. Some people are not interested, others are not friends themselves. And again loneliness.

3. Disregard for the interests of the group of peers is also manifested in the separation of the child from the group. Modern parents load their children with extra classes so much that they tear them away from the general school affairs. A child is not like everyone else, he cannot clean the school yard along with everyone else, because he has chess or ballet. Thus, social ties are destroyed at the stage of their formation.

4. Unformed communication skills. Children do not know how to communicate: they are rude, they do not know how to give in, share, play. Peers avoid communicating with such guys.

Read also

Child's loneliness - vagaries or child depression?

What to do if a child has no friends

How to help a child

The true causes of loneliness may not be seen. A child may not take part in peer games for years, and his lonely drawing may be perceived as a penchant for artistic activity. Perhaps the source of alienation was the old clothes that you put on your child in kindergarten, the lack of a telephone in elementary school for your fundamental reasons, a large number of tutors, refusal to social activities, a ban on communicating with someone. It's hard to admit your mistake, even harder to correct it. But it needs to be done.

- Be sensitive. Try to understand what is happening with the child right now: he does not need communication or his peers do not accept him. Do this delicately, observing the child, communicating with him. Pay attention to children's self-esteem. If a child shares a problem, then do not rush to solve it by mocking or calling the teacher, but think about how to fix the situation.

- Start with the child's self-assessment. It is important to instill confidence in him. Just do it gently and patiently. Increasing self-esteem is a complex and lengthy process.

- Tell us about your experience: about friends and girlfriends, give an example of maintaining friendship with dad and mom. Start teaching your child to value friendship.

- Think about possible friends. Surely there are children in the classroom, in the yard, in the dance group who are cute to the child, he reaches out to them, but there is no way to be friends. Think about how to start a friendship: invite guests, drive home, share a treat. Friendship means giving. Support the child's initiative.

- Teach your child to communicate, form communication skills. Your child should become interesting for his peers, and then he will have friends.

If a child is loved and respected in the family, his needs are listened to, respect for others is brought up, communication skills are developed, then he will avoid the problems of loneliness. He is loved in the family, and is no longer alone. And temporary difficulties can be overcome.

He is loved in the family, and is no longer alone. And temporary difficulties can be overcome.

Svetlana Sadovnikova

Photo from houstonfamilymagazine.com

Does the child feel good at school

Often parents do not know what happens to the child while he is at school, whether he likes it in class. After passing this test, you will find out what kind of relationship your child has with classmates and whether he likes school life.

Take the test

More on the topic

The holiday is coming to us: children's crafts for the New Year

How to grow a boor - anti-advice

Games for the emotional growth of children

How to help a child who feels lonely

The need for communication, emotional intimacy is one of the basic needs for any person, including a child. All parents want their kids to have real friends in childhood. But what if the child fails to make friends? How can you help a child who feels lonely? Let's figure it out together with psychologist Svetlana Pyatnitskaya.

Svetlana Pyatnitskaya, preschool teacher, child and perinatal psychologist, author of educational programs for preschool children

Why a child is lonely

To help a child experiencing loneliness, it is important to understand why there are no people close to him among his peers.

Moving to another place, moving to a new school or class

Finding himself in a new environment, losing his usual social circle, the child will initially feel loneliness especially acutely. But over time, this will pass, because he will make new friends.

Features in behavior and appearance

In a children's team, a child who is not like the others is often chosen as a target for mockery. If the baby has a nervous tic or stuttering, severe lameness, excessive emotionality, unfortunately, he can easily become the object of ridicule of peers.

Differences in views, life principles, priorities

A child can be brought up in such a way that it will be difficult for him to find common ground with other children.

There are children who are taken care of by the older generation with "outdated" ideals, and they adopt the gestures and manner of communication of such adults. You can immediately see such kids: they use turns and expressions that have not been used for a long time, sigh, lament, shuffle, look like little old people, are too, not childish, principled in some matters.

Other children broadcast the values of their family to the world, which may cause rejection in other children: “You have an antediluvian car”, “Books are for idlers, that’s what my mother says.”

Influence of parents

Mom or dad can speak negatively about other children: “Don’t be friends with this boy, he is not worthy of your attention”, “This girl will teach you bad things, you don’t need to communicate with her.”

Influence of the teacher

Kindergarteners and elementary school students have a very authoritative figure of an adult, and they often agree with the teacher's opinion simply because he "set the tone". “You, as always, did not cope with the task,” children may treat a child who hears this from a teacher worse.

“You, as always, did not cope with the task,” children may treat a child who hears this from a teacher worse.

Self-esteem

It is difficult for a child to get close to someone if he considers himself inferior to others, and therefore unworthy. Inflated self-esteem also prevents you from making friends. Children do not like those who turn up their noses, nor those who desperately need their attention and try to please with sweets.

Be sensitive the situation is a temporary difficulty that can be dealt with. Just refrain from depreciating expressions: “Come on, you still know how many such friends you will have! Is it worth getting upset over such nonsense?" If the child shared this, then he trusts you. Appreciate this desire to tell you about the innermost and respect the feelings of the baby.

Use "I-messages"

Start a conversation like this: "I see that you are upset about something, something is bothering you all day." If you correctly caught the mood of the child and hit the sore spot, he will tell you everything. But if he doesn't want to talk, don't be persistent, otherwise he will shut up.

But if he doesn't want to talk, don't be persistent, otherwise he will shut up.

Tell about your experience

Share your personal story, without giving advice, without preaching: “I think I understand what you are talking about. I had a similar case in my childhood. I'll tell you if you want, and you'll tell me if I understand you correctly." By doing this, you will show the child that you understand his pain, share it, because you have experienced the same, but everything will pass.

Consult literature

Read works with similar themes. For example, Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale "The Ugly Duckling". But without moralizing! Do not tell your child: "The main character is smart, and the rest are stupid!". Here it is important to explain to the kid that we are all different: “There are inconspicuous people who have a good heart. Not everyone can see it. Each of us has different interests, and some of us are close to us right away, while others we let in over time. There are people who you like at first sight, but then you realize that your interests do not converge. And at first you don’t like someone, and then you realize that you share his views.” Ask the child how he understands the meaning of the fairy tale.

There are people who you like at first sight, but then you realize that your interests do not converge. And at first you don’t like someone, and then you realize that you share his views.” Ask the child how he understands the meaning of the fairy tale.

Discuss specific situations

A child may feel rejected and very distressed if one of their peers invited half of the class to their birthday party and was not invited. To help your child cope with this situation, explain to him why this might have happened. For example, because everyone has different opportunities, it is not always possible to invite all, all friends to your home or apartment for your birthday. Talk about how if our options are limited, we have to limit our desires.

Ask your child who they would invite to their party if they could only invite five people. What would he say to those guys whom he could not call? Perhaps it would be easier for him to survive the situation if he knew why he was not invited. And after this conversation, he will begin to understand that the reason may not be in him, and there is no reason to be sad.

And after this conversation, he will begin to understand that the reason may not be in him, and there is no reason to be sad.

How to find friends

If your child has been feeling lonely for a long time, think about how this is related to your family. What do you, as a parent, do to ensure that he does not feel lonely? What is the attitude towards material values in your family? Does the child consider himself inferior to others because you do not buy him fashionable smartphones and expensive toys?

The kid may not be friends with anyone also because he does not like his peers, and this also needs to be dealt with. If he does not have the same interests and level of development with the guys he knows, it makes no sense to strive to start relationships with them at all costs. You can find a group of interests, for example, a sports section, and look for new friends there. When there is some activity that the child likes, when he makes progress in it, it is easy for him to find like-minded people outside the school.