How to help a child with cancer

Supporting a Child With Cancer

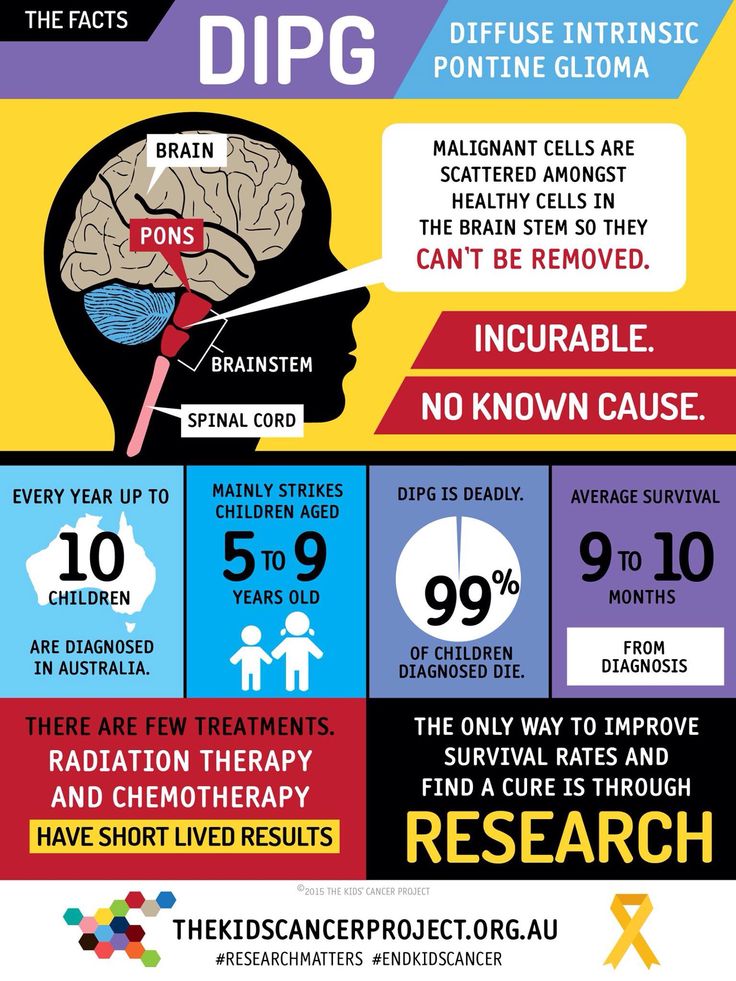

Cancer has a significant impact on anyone, but especially on children who have been diagnosed. Children face unique challenges and adjustments, but can be very resilient. It helps to talk to your child about what they can expect and encourage them to share their feelings. Here are some tips on how to support your child during this time.

Talk to your child. Give age-appropriate and honest information about their diagnosis. Don’t be afraid to use the word “cancer.” While adults often associate fear with the word, children feel secure knowing what their illness is called.

You can be realistic while remaining hopeful. Encourage your child to ask questions throughout their treatment. If you do not know the answer to a question, don’t be afraid to say “I don’t know. That’s a good question and I will try to find out.” Hospital social workers will have examples of appropriate language to use, and may be helpful when explaining details about the cancer.

Prepare your child. Go over the treatment plan and how it will affect their life. Prepare your child for physical changes they may experience during treatment (for instance, hair loss, fatigue or weight loss). Make a list of questions they have and bring them to the medical team if you do not have the answers at the time.

Reassure your child. Let your child know that their medical team will take care of them and you will provide support. During this time they may ask for or need more reassurance since they are feeling vulnerable. Continue to let your child know that you are there to take care of them and that you and their doctors will be working to help them.

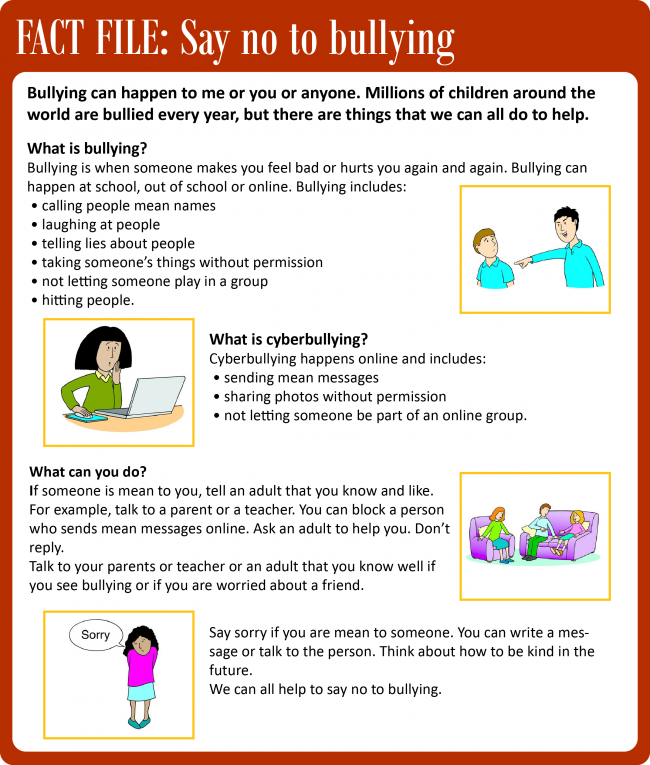

What to say. Discuss ways your child can respond to questions from their peers. Your child’s classmates and friends may ask them questions about their illness. Cancer has a significant impact on anyone, but especially on children who have been diagnosed. Children face unique challenges and adjustments, but can be very resilient. It helps to talk to your child about what they can expect and encourage them to share their feelings. Here are some tips on how to support your child during this time.

It helps to talk to your child about what they can expect and encourage them to share their feelings. Here are some tips on how to support your child during this time.

You can prepare your child for this by discussing how they are most comfortable responding. While some children would rather not discuss their diagnosis with classmates, others may wish to be more open. Respecting your child’s specific wishes can help them maintain a sense of control over who knows their story.

Encourage your child to express their feelings. Explain that feelings can be expressed in many different ways such as talking, writing in a journal, drawing or sports. All feelings are acceptable and understandable. Let them know that it’s also okay to say, “I don’t want to talk right now,” and that you’ll still support them.

It’s a team effort. Work with your child’s teachers, school social worker and nurses. Meet with them to discuss your child’s medical and educational needs. A school liaison help coordinate information about your child’s school work and health matters.

A school liaison help coordinate information about your child’s school work and health matters.

The school liaison can also be in contact with your child’s medical team. Speak with the school about the necessary process should your child become sick. Explore remote learning options, if they are available.

Support for you. As a caregiver, it can be easy to forget about your own needs. Remember that in order to be there for your child, you need to take care of your own physical and emotional needs. Find time to practice self-care, even in small ways such as taking a walk, talking with a friend or wearing your favorite clothes. By caring for yourself, you will also be modeling healthy behavior for your child, and can share in some of those self-care activities together.

Reach out. Help your child identify the adults who can offer support. These people may include your spouse or partner, relatives, friends, clergy, teachers, coaches and members of your child’s health care team. You may also want to speak with your hospital social worker about local counseling and support services for children with cancer. Talk with your child about ways they want to be supported, and things they find helpful.

You may also want to speak with your hospital social worker about local counseling and support services for children with cancer. Talk with your child about ways they want to be supported, and things they find helpful.

Support options. Connecting with other children who have cancer can help your child feel less alone with their diagnosis. Some organizations have peer-mentoring for children diagnosed with cancer, as well as caregivers caring for a child with cancer. Joining a support group for parents who have a child with cancer can help you feel less alone in your journey as well. Speak to your hospital social worker about local support groups or call 800-813-HOPE (4673) to speak with a CancerCare oncology social worker about support services available to you.

Edited by Charlotte Ference, LMSW

Similar to This Publication

- Talking to Children When a Loved One Has Cancer

- Caring Advice for Caregivers: Caring for Yourself When Your Child Has Cancer

- Helping Your Loved One or Child Cope with Hair Loss

- Helping the Siblings of a Child with Cancer

- Helping Children Understand Cancer: Talking to Your Kids About Your Diagnosis

This Publication Is Tagged With

Tags:

childhood cancerschildrensiblings

Browse by Diagnosis

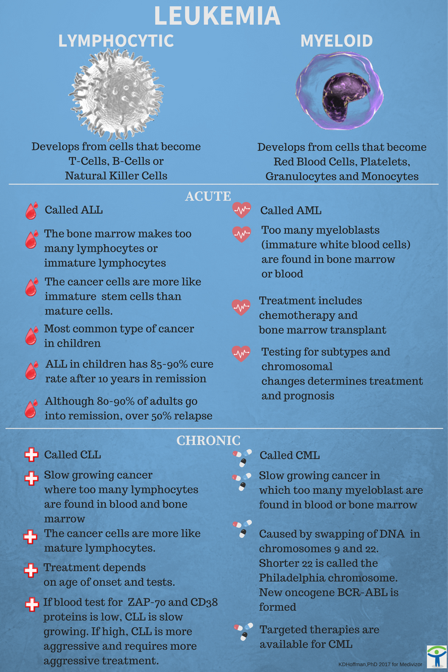

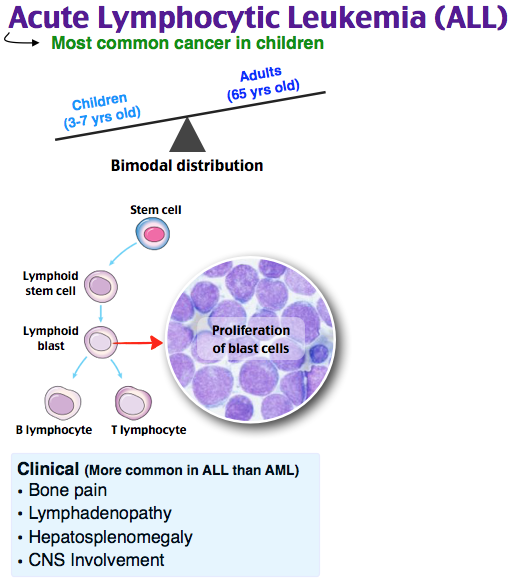

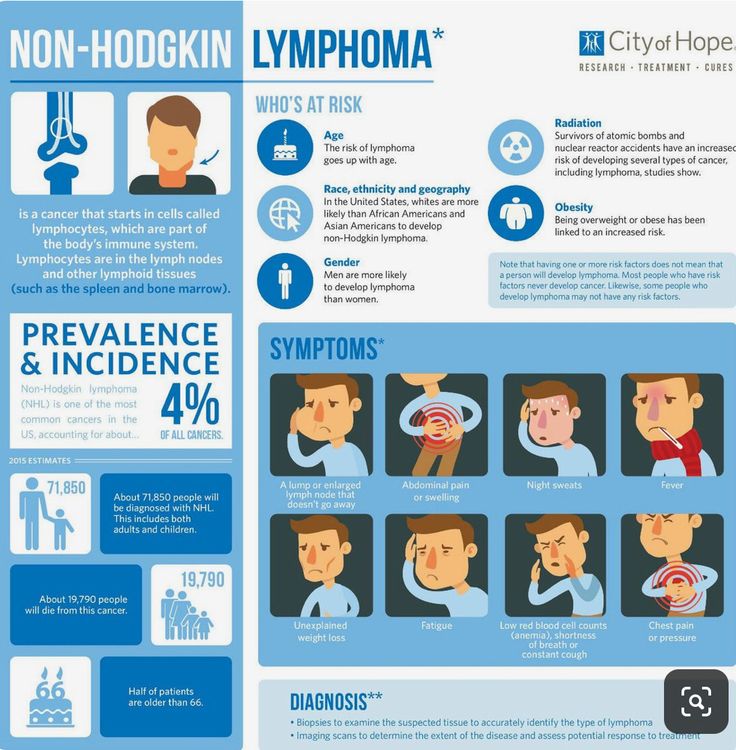

Please selectAcute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaAcute Myeloid LeukemiaAnal CancerBasal Cell CancerBladder CancerBone CancerBrain CancerBreast CancerCancer of Unknown PrimaryCarcinoid TumorCervical CancerChronic Lymphocytic LeukemiaChronic Myelogenous LeukemiaColorectal CancerCutaneous T-Cell LymphomaDiffuse Large B-Cell LymphomaEndometrial CancerEsophageal CancerEye CancersFollicular LymphomaGastric CancerGastrointestinal Stromal TumorsGlioblastomaHead and Neck CancerHodgkin LymphomaKidney CancerLeukemiaLiver CancerLung CancerLymphomaMantle Cell LymphomaMarginal Zone LymphomaMelanomaMerkel Cell CarcinomaMesotheliomaMetastatic Breast CancerMultiple MyelomaMyelodysplastic SyndromesMyelofibrosisMyeloproliferative NeoplasmsNeuroendocrine TumorsNon-Hodgkin LymphomaOvarian CancerPancreatic CancerPeripheral T-Cell LymphomaPolycythemia VeraProstate CancerRare CancersRenal Cell CancerSarcomaSkin CancerSmall Lymphocytic LymphomaSquamous Cell CancerStomach CancerTesticular CancerThyroid CancerTriple Negative Breast CancerUterine CancerVaginal CancerWaldenstrom’s MacroglobulinemiaBrowse by Topic

Please selectAdherenceAdolescents and Young AdultsAdvanced CancerAdvocacyAffordable Care ActAnxietyAppsBiomarkersBiosimilarsBlack or African AmericanBlood ClotsBody ImageBone HealthBone Marrow TransplantCAR T-Cell TherapyCamps and RetreatsCare PlanningCaregivingChemobrainChemotherapyChildhood CancersChildrenClinical TrialsColostomyCopingCoronavirusCounselingDental HealthDiagnostic TestsDiarrheaDisaster ReliefDoctor-Patient CommunicationDry MouthDry SkinExerciseFatigueFertilityFinancial AssistanceGeneticsGrief and LossHair LossHealth Care DisparitiesHealth Care ProfessionalsHolidaysHospice and End-of-LifeImmunotherapyInfectionInsuranceIntimacyJournalingLGBTQ+Legal AssistanceLodgingLymphedemaMastectomyMedical MarijuanaMedicareMeditationMind-BodyMouth SoresNausea and VomitingNeuropathyNutritionOlder AdultsPainPalliative CarePatient and Peer MatchingPersonalized MedicinePetsPost-Treatment SurvivorshipProsthesesRashRecurrenceRelaxation TechniquesScreening and PreventionSensory DisruptionsSiblingsSide EffectsSleepSocial SecuritySpiritualityStressSupport GroupsTargeted TreatmentsTeensTransportationTreatmentVeteransVision IssuesWeightWigsWorkplace IssuesYogaYoung AdultsDownload a PDF(519 KB) of this publication or order a free print copy.

This fact sheet is made possible by Takeda Oncology.

Last updated June 10, 2021

The information presented in this publication is provided for your general information only. It is not intended as medical advice and should not be relied upon as a substitute for consultations with qualified health professionals who are aware of your specific situation. We encourage you to take information and questions back to your individual health care provider as a way of creating a dialogue and partnership about your cancer and your treatment.

Support for Families When a Child Has Cancer

When a child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Parents often feel shocked and overwhelmed following their child’s cancer diagnosis. Honest and calm conversations build trust as you talk with your child and his or her siblings. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important; it’s not selfish. As you dig deep for strength, reach out to your child’s treatment team and to people in your family and community for support.

How to Talk to Children about Cancer by Age

As you talk with your child, begin with the knowledge that you know your child best. Your child depends on you for helpful, accurate, and truthful information. Your child will learn a lot from your tone of voice and facial expressions, so stay calm when you talk with your child.

When Your Child Is Diagnosed with Cancer

Watch this video to hear how parents moved forward after their child was diagnosed with cancer and found a hospital with expertise in treating children with cancer.

Access an audio described version of the video

The age-related suggestions below may be helpful as you work with the health care team, so your child knows what to expect during treatment, copes well with procedures, and feels supported.

If your child is less than 1 year old: Comfort your baby by holding and gently touching her. Skin to skin contact is ideal. Bring familiar items from home, such as toys or a blanket. Talk or sing to your child, since the sound of your voice is soothing. Try to keep up feeding and bedtime routines as much as possible.

Talk or sing to your child, since the sound of your voice is soothing. Try to keep up feeding and bedtime routines as much as possible.

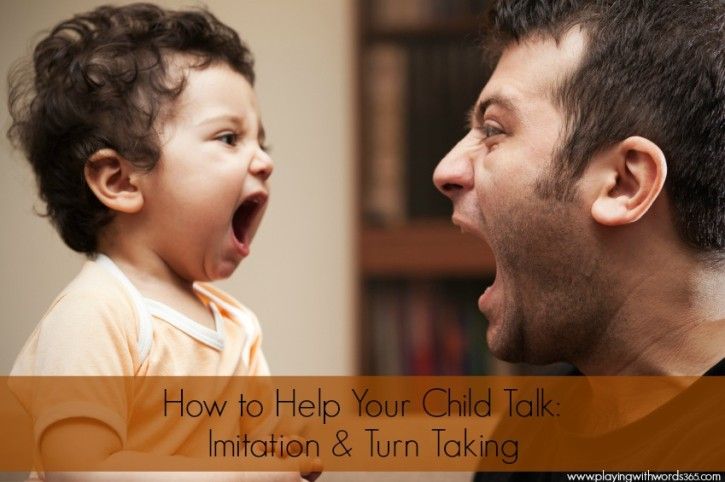

If your child is 1 to 2 years old: Very young children understand things they can see and touch. Toddlers like to play, so find safe ways to let your child play. Toddlers also like to start making choices, so let your child choose a sticker or a flavor of medicine when possible. Prepare your child ahead of time if something will hurt. Not doing so may cause your child to become fearful and anxious.

If your child is 3 to 5 years old: To help your child understand his treatment better, ask the doctor if he can touch the models, machines, or supplies (tubes, bandages, or ports) ahead of time. If a procedure will hurt, prepare your child in advance. You can help to distract your child by reading a story or giving her a stuffed animal to hold.

If your child is 6 to 12 years old: School-aged children understand that medicines and treatment help them get better. They are able to cooperate with treatment but want to know what to expect. Children this age often have many questions, so be ready to answer them or to find the answers together. Relationships are important, so help your child to stay in touch with friends and family.

They are able to cooperate with treatment but want to know what to expect. Children this age often have many questions, so be ready to answer them or to find the answers together. Relationships are important, so help your child to stay in touch with friends and family.

If your child is a teenager: Teens often focus on how cancer changes their lives—their friendships, their appearance, and their activities. They may be scared and angry about how cancer has isolated them from their friends. Look for ways to help your teen stay connected to friends. Give your teen some of the space and freedom he had before treatment and include him in treatment decisions.

Information to help you choose a hospital and learn more about your child’s treatment plan is included in the Diagnosis section of our childhood cancer guide for parents.

Tips for Parents of a Child with Cancer

Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents

Practical information about childhood cancer, treatment, coping, and more for parents and health care providers.

Talk with your child’s health care team to get your questions answered. You may also find the suggestions below helpful:

Who should tell my child?

Many parents receive their child’s diagnosis from the doctor at the same time that their child learns of it. However, if you choose to be the one to tell your child, the doctor or nurse can help you decide what to say and how to answer her questions.

When should my child be told?

Your child should be told as soon as possible. This will help build trust between you and your child. It does not mean that your child needs to hear everything all at once.

What should I tell my child?

The information you share with your child depends on his age and what he can understand. Children of all ages need clear, simple information that makes sense to them. As much as possible, help him know what to expect by using ideas and words that he understands. Tell your child how treatment will make him feel and when something will hurt. Explain that strong medicine and treatments have helped other children.

Explain that strong medicine and treatments have helped other children.

How much should I tell my child?

Help your child to understand the basic facts about the illness, the treatment, and what to expect. It may be hard for many children to process too many details or information given too far in advance. Start with small amounts of information that your child can understand. Children often use their imaginations to make up answers to unanswered questions and may fear the worst. Answering questions honestly and having ongoing conversations can help your child. Telling untruths can cause your child to distrust you or people on their health care team.

How might my child react?

Each child is different. Some worry. Others get upset or become quiet, afraid, or defiant. Some express their feelings in words, others in actions. Some children regress to behaviors they had when they were younger. These are normal reactions to changes in life as they know it. Their schedule, the way they look and feel, and their friendships may all be changing. Expect that some days will be rough, and others will be easier. Tell your child, and find ways to show her, that you will always be there for her.

Expect that some days will be rough, and others will be easier. Tell your child, and find ways to show her, that you will always be there for her.

What can I do to help my child cope?

Children take cues from their parents, so being calm and hopeful can help your child. Show your love. Think about how your child and family have handled difficult times in the past. Some children feel better after talking. Others prefer to draw, write, play games, or listen to music.

How to Explain Cancer to a Child at Diagnosis

Talk with your child’s health care team about how to answer questions your child may have. You may also find these suggestions helpful:

What is cancer?

When talking about cancer with your child, start with simple words and concepts. Explain that cancer is not contagious—it’s not an illness that children catch from someone or that they can give to someone else. Young children may understand that they have a lump (tumor) that is making them sick or that their blood is not working the way it should. Parents and older children may want to read about different types of childhood cancer in the Diagnosis section of our childhood cancer guide for parents.

Why did I get cancer?

Some children think they did something bad or wrong to cause the cancer. Others wonder why they got sick. Tell your child that nothing he—or anyone else—did caused the cancer, and that doctors are working to learn more about what causes cancer in children.

- You may tell your child: I don't know. Not even doctors know exactly why one child gets cancer and another doesn't. We do know that you didn’t do anything wrong, you didn't catch it from someone, and it’s not contagious.

Will I get better?

Being in the hospital or having many medical appointments can be scary for a child. Some children may know or have heard about a person who has died from cancer. Your child may wonder if she will get better.

- You may tell your child: Cancer is a serious illness, and your doctors and nurses are giving you treatments that have helped other children.

We are going to do all we can to help you get better. Let's talk with your doctor and nurse to learn more about the type of cancer you have.

How will I feel during treatment?

Your child may wonder how he may feel during treatment. Children with cancer often see others who have lost their hair or are very sick. Talk with the nurse or social worker to learn how your child’s treatment may affect how your child looks and feels, and about side effects that he may have.

- You may tell your child: Even when two children have the same type of cancer, what happens to one child may not happen to the other. Your doctors and I will talk with you and explain what we know. We will all work together as a team to help you feel as comfortable as possible during treatment.

Ways to Help Children with Cancer

Cancer treatment brings many changes to a child’s life and outlook. You can help your child by letting her live as normal a life as possible. Talk with the health care team to learn what to expect, as your child goes through treatment, so your child and family can prepare.

Supporting Your Child with Cancer

Listen to insights from pediatric oncology experts and parents on how to help your child when they are going through treatment for childhood cancer.

Access an audio described version of the video

Helping Your Child Adjust to Physical ChangesChildren can be sensitive about how they look and how others respond to them. Here are ways to help your child:

- Prepare for physical changes: If treatment will cause your child's hair to fall out, let your child pick out a fun cap, scarf, and/or wig ahead of time. Some treatments may cause changes in weight. Meeting with a registered dietitian can help your child get the nutrients her body needs to stay strong during treatment.

- Side effects: Your child’s nurse will talk with you and your child about supportive care. This is care that is given to manage side effects and improve your child’s quality of life.

Information to help lower pain, provide good nutrition, prevent infection, and manage common health problems during treatment is also in the Treatment section of our childhood cancer guide for parents.

Information to help lower pain, provide good nutrition, prevent infection, and manage common health problems during treatment is also in the Treatment section of our childhood cancer guide for parents. - Help your child know how to respond: Sometimes people will stare, mistake your child's gender, or ask personal questions. Talk with your child and come up with an approach that works. Your child may choose to respond or to ignore comments.

Your child's friendships are tested and may change during a serious illness, like cancer. Sometimes it may seem as though old friends are no longer “there for them.” It may help if your child takes the first step and reaches out to friends. Children may also make new friends through this experience. Here are some steps you can take with your child:

- Help your child stay in touch with friends: You can encourage or help your child connect with friends through text messages, video chats, phone calls, and/or social media.

- Get tips and advice: A social worker or child-life specialist can help your child think through what they would and would not like to share with friends. If possible, and when your child is up to it, friends may be able to visit. Your child may also be able to participate in school and other activities, based on the advice of their doctor.

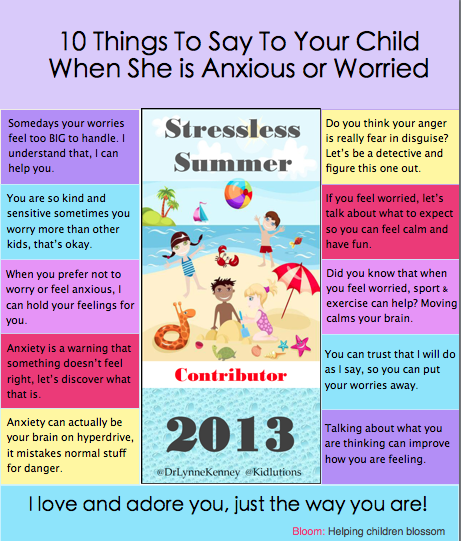

Although over time many children with cancer cope well, your child may feel anxious, sad, stressed, scared, or become withdrawn at times. Talk with your child about what she is feeling and help her find ways to cope. Your child can also meet with a child-life specialist or psychologist about feelings that don’t have easy solutions or seem to be getting worse over time. These tips may help your child cope with difficult emotions:

- Find ways to distract and entertain your child: Playing video games or watching movies can help your child to relax.

You can also learn about other practice that can support your child during treatment, such as: art therapy, biofeedback, guided imagery, hypnosis, laughter therapy, massage therapy, meditation, music therapy, and relaxation therapy, among others. Learn more about integrative medicine practices that help children in the Resources section of our childhood cancer guide for parents.

You can also learn about other practice that can support your child during treatment, such as: art therapy, biofeedback, guided imagery, hypnosis, laughter therapy, massage therapy, meditation, music therapy, and relaxation therapy, among others. Learn more about integrative medicine practices that help children in the Resources section of our childhood cancer guide for parents. - Stay calm but do not hide your feelings: Your child can feel your emotions. If you often feel sad or anxious, talk with your doctor and child's health care team so you can manage these emotions. Yet keep in mind that if you often hide your feelings, your child may also hide their feelings from you.

- Get help if you see emotional changes in your child: While it’s normal for your child to feel down or sad at times, if these feelings happen on most days over a long period of time, they may be signs that your child needs extra support. Meeting with your child's nurse, child-life specialist, and/or psychologist can help your child learn how to manage stress, and they can assess your child for mental health conditions such as an anxiety disorder and depression.

Your child may spend more time in the hospital and at home, during treatment. Here are ways to help your child cope with periods of isolation and time away from friends.

Hospital stays: Being in the hospital can especially difficult for children. It’s a different setting, with new people and routines, large machines, and sometimes painful procedures.

- Bring in comfort items. Let your child choose favorite things from home, such as photos, games, and music. These items can comfort children and help them to relax.

- Visit game rooms, playrooms, and teen rooms. Many hospitals have places where patients can play, relax, and spend time with other patients. These rooms often have toys, games, crafts, music, and computers. Encourage your child to take part in social events and activities that are offered at the hospital.

Isolation at home: While your child is receiving treatment, she may need to stay at home for extended periods of time, due to the side effects of cancer treatment such as fatigue, risk of infection, pain, and gastrointestinal complications, for example.

- Decorate your child’s room. Posters, pictures, and other decorations may brighten the room and help cheer up your child. Window markers are a fun way to decorate. Check to see if any items should be removed from your child’s room, since there are sometimes medical restrictions.

- Explore new activities. If sports are off-limits, learn about other activities that can help your child stay active and have fun. Your child may also enjoy listening to music, reading, playing games, or writing. Some children with cancer discover new skills and interests they never knew they had.

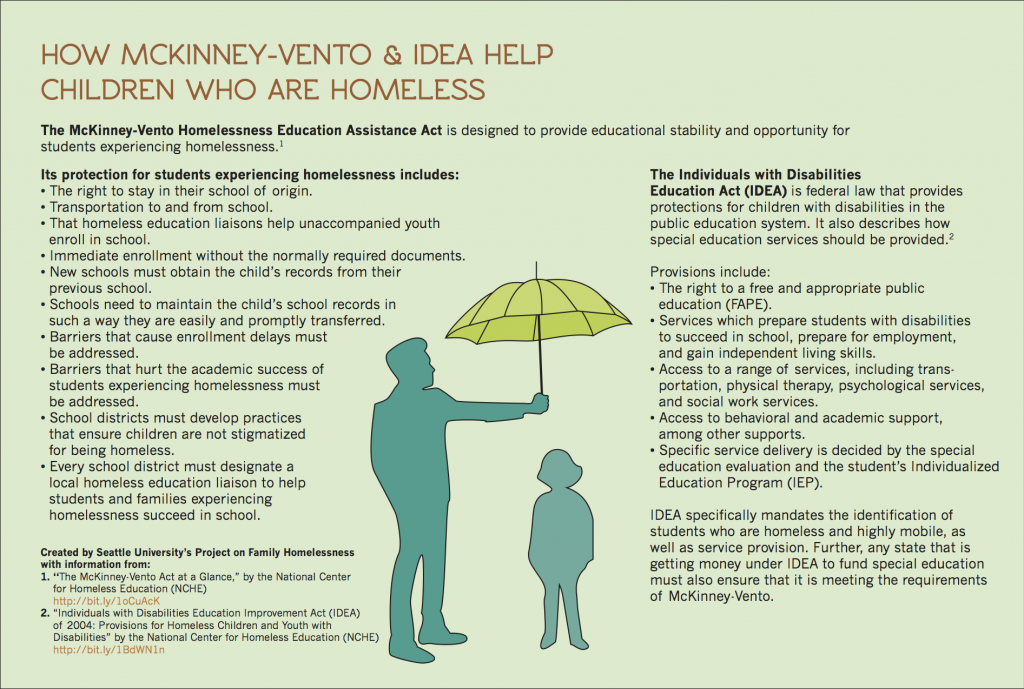

Missing school: While some children with cancer are able to attend school, many need to take a leave of absence for short or long periods of time. Here are ways to get the academic support your child needs during this time:

- Meet with your child's doctor to learn more about how treatment may affect your child's energy level and ability to keep up with schoolwork. Ask the doctor to write a letter to your child’s teachers that describes your child’s medical situation, limitations, and how much time your child is likely to miss.

- Keep your child's teachers updated. Tell your child's teachers and principal about your child's medical situation. Share the letter from your child's doctor. Learn what schoolwork your child will miss and about ways for your child to keep up, as they are able.

- Learn about assistance from the hospital and your child's school. Hospitals have education coordinators or nurses who can talk with you about academic resources and assistance for your child. You will also want to ask about an individualized education plan (IEP), also called a 504 plan, for your child.

Learn more about ways to help your child cope in the Support section of our childhood cancer guide for parents.

How to Cope as Parents and Siblings of Children with Cancer

These suggestions can help you care for yourself, your children, and your family. Parents often say that their child’s diagnosis feels like a family diagnosis. Here is practical advice to help families cope and stay connected during this challenging time.

Support for Your Family When a Child Has Cancer

Everyone in the family needs support when a child has cancer. Get tips related to self-care, marriage, and support for siblings from oncology experts and parents.

Access an audio described version of the video

Work to Keep Relationships StrongRelationships and partnerships are strained and under pressure when a child has cancer. However, marriages can also grow stronger during this time. Here’s what parents said helped:

- Keep lines of communication open: Talk about how you each deal best with stress. Make time to connect, even when time is limited.

- Remember that no two people cope the same way: Couples often have different coping strategies. If your spouse or partner does not seem as distraught as you, it does not mean he or she is suffering any less than you are.

- Make time: Even a quick call, text message, or handwritten note can go a long way in making your spouse’s or child’s day a better one.

Research shows what you most likely already know—that help from others strengthens and encourages your child and family. Family and friends may want to assist but might not know what you need. It may help to:

- Find an easy way to update family and friends: Consider posting updates and getting practical support through sites such as Caring Bridge, My Cancer Circle, MyLifeLine, or Lotsa Helping Hands. Share only what you feel comfortable sharing.

- Be specific about how people can support your family: Keep a list handy of things that others can do for your family. For example, people can cook, clean, grocery shop, or drive siblings to their activities.

- Join a support group: Some groups meet in person, whereas others meet online. Many parents benefit from the experiences and information shared by other parents.

- Seek professional help: If you are not sleeping well or are depressed, talk with your primary care doctor or people on your child’s health care team.

Ask them to recommend a mental health specialist such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, counselor, or social worker.

Ask them to recommend a mental health specialist such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, counselor, or social worker.

It can be tempting to put your own needs on hold and focus solely on your sick child. However, it’s essential that you make time for yourself. Doing so can also give you energy to care for your child. Here are some tips to help get you started:

- Find ways to relax and lower stress: Some parents try something new, such as a yoga or deep-breathing class at the hospital. Others are refreshed by being outdoors, even for short periods. Whatever the method or place, find one that feels peaceful to you. Here are techniques you can use to relax, from a page that’s helpful for both patients and parents alike.

- Fill waiting time: Pick a few activities that you enjoy and can do at the hospital, such as playing a game, reading, writing, or listening to music.

- Stay physically active: Plan to walk, jog, go to the gym, or follow a workout app.

Exercising with a friend or family member can make it easier to keep up the routine. If it’s hard to stay physically active at the hospital, try walking up and down the stairs or around the hospital or unit. Physical activity helps to lower stress and can also help you to sleep better at night.

Exercising with a friend or family member can make it easier to keep up the routine. If it’s hard to stay physically active at the hospital, try walking up and down the stairs or around the hospital or unit. Physical activity helps to lower stress and can also help you to sleep better at night.

Learn more about ways to cope and stay strong in the Support section of our childhood cancer guide for parents and in Support for Caregivers of Cancer Patients.

Support Siblings When a Brother or Sister has CancerWhen Your Brother or Sister Has Cancer

Information for teens and children who have a sibling with cancer.

As a parent, you want to be there for all your children, yet this can be challenging when a child is being treated for cancer. You may notice that siblings are having a difficult time yet struggle to address their needs. Insights and suggestions on strategies to help siblings are shared in the video above.

Here are some more ways you can help siblings during this difficult time:

- Listen to and connect with siblings: Set aside some time every day, even if it’s just a few minutes, to spend with your other children. Check in and ask how they are doing, even if you do not have an easy solution to every challenge they may be facing. It’s important to connect with and listen to them.

- Keep siblings informed and involved: Talk with your children about their sibling’s cancer and tell them what to expect during treatment. If possible, find ways to include them in hospital visits. If you are far from home, find ways to connect through video chat, text messages, and phone calls, for example.

- Keep things as normal as you can: Arrange to keep siblings involved in school-related events and activities that are important to them. Ask friends and neighbors for support. Most people want to help and will appreciate being asked.

This booklet When Your Brother or Sister Has Cancer has quotes from siblings about their experiences, checklists to help siblings get support, and a section of related organizations and resources. It can be printed or viewed as a booklet, an ePub, or a Kindle book. A hard copy of the booklet can also be ordered, for no charge.

It can be printed or viewed as a booklet, an ePub, or a Kindle book. A hard copy of the booklet can also be ordered, for no charge.

What Parents Can Do during Treatment for Children with Cancer

These suggestions can help you and your child to establish strong and effective relationships with your child’s health care team.

- Build strong partnerships

Give and expect to receive respect from the people on your child’s health care team. Open and honest communication will also make it easier for you to ask questions, discuss options, and feel confident that your child is in good hands. - Take advantage of the many specialists who can help your child

Work with them to help your child learn about cancer, how it will be treated, prepare for tests, manage side effects, and cope. - If you get information online, make sure the source is credible

It’s important to get accurate information that you understand and can use to make decisions. Share what you find with the health care team to confirm that it applies to your child.

Share what you find with the health care team to confirm that it applies to your child. - Make sure you understand what your child’s health care team tells you

Speak up when something is confusing or unclear, especially when decisions need to be made. Ask to see pictures or videos to help understand new medical information. - Keep your child’s pediatrician updated

Ask for updates to be sent to your child’s regular pediatrician.

Managing Cancer Information During Your Child’s Treatment

Parents and pediatric oncology experts discuss how to find credible information and work together as active partners on a child’s treatment team.

You may also want to watch this video: Treatment Considerations for Children with Cancer in which parents and pediatric oncology experts discuss childhood cancer treatment-related decisions, side effects, clinical trials, and strategies to care for children.

Talking to your child about cancer

Remember three principles when talking to your child about cancer:

- Be honest and open.

- Use words that the child can understand to describe illness and treatment.

- Provide details appropriate to the child's age and developmental level.

-

Child friendly definitions

-

Age-appropriate information

A sick child needs to know that he is loved, supported and surrounded by people who care for him.

The Importance of Honesty and Openness

Being honest and open with your child will help build trust and strengthen your relationship. You may want to hide from your child that he has cancer, or try to protect him from negative information. To seek to protect children from something unpleasant is a natural desire.

However, children are very observant. Even if they don't seem to be paying attention, they watch their parents, doctors, and other family members or adults to find out what's going on. It is very likely that during treatment the child will hear the word cancer (from staff, another child in the hospital, or even relatives and friends), even if you have asked people not to say it. Many parents say that it is easier to explain a situation to a child than to prevent other people from talking about it. An explanation can relieve the tension that comes with constantly trying to hush up a situation.

Even if they don't seem to be paying attention, they watch their parents, doctors, and other family members or adults to find out what's going on. It is very likely that during treatment the child will hear the word cancer (from staff, another child in the hospital, or even relatives and friends), even if you have asked people not to say it. Many parents say that it is easier to explain a situation to a child than to prevent other people from talking about it. An explanation can relieve the tension that comes with constantly trying to hush up a situation.

- Choosing to communicate openly is important for a number of reasons: even young children can feel that something is wrong. If you don't tell your child what's going on, he's more likely to make assumptions or use his imagination. Often what they imagine turns out to be worse than the truth.

- Children tend to blame themselves when something bad happens to them. They should know that they are not to blame for their illness.

- The more the child understands, the less frightening the situation seems to him. Children are usually more willing to accept treatment if they know how it can help them.

- Honesty will help reduce the child's anxiety, embarrassment and guilt due to misunderstanding of the situation.

Plan what and how to say

Speak in advance what you are going to tell the child. Seek advice from doctors or another parent who has been in a similar situation.

The way information is exchanged is also important. The child will understand a lot by the tone of your voice and facial expression. Remain calm when talking to your child. If you can't hold back your tears, don't be upset - this is normal, explain why you are crying. You might say that it's natural for parents to feel sad when their child is sick, or that people can get upset when their life changes so much. Tears are a way of expressing emotions. It is important for children to be sure that cancer is not the result of their actions and that people get upset through no fault of their own.

It is important how you talk to your child about the diagnosis. Remain calm while talking.

Decide who and when will tell the child

Many parents learn the diagnosis from the doctor at the same moment when the child learns it too. However, if you want to share this information with your child, the treatment team can help you decide what to say and how to answer questions.

Tell the child as soon as possible. This will help build trust.

Consider asking another person to be with you during the first conversation. It could be another family member or close friend who can be supportive. Or it could be a doctor, nurse, child adjustment specialist, or social worker who can describe the illness in more detail.

What to tell your child about cancer

The basic questions for most children and adolescents are the same:

- What is cancer?

- Why did I have it?

- Will I get better?

- What will happen now?

- When can we return home?

- What about school?

Children need information to endure procedures, cope with feelings, and stay in control of situations. Most of all, they need to know that they are loved, supported and surrounded by people who care about them.

Most of all, they need to know that they are loved, supported and surrounded by people who care about them.

Trust your instincts. You know your child better than anyone else. You know the best way to talk to him. Here are some helpful tips.

- Consider the child's age. You may need to talk to the child adaptation specialists at the oncology center. They understand child development. They can help you describe the illness in age-appropriate terms and, given the child's stage of development, help him or her accept the information. They can explain concepts through therapeutic play and visual aids. In addition, social workers, psychologists and priests can provide support.

- Think carefully about how many details you want to share in one conversation. As a rule, it is recommended to start with general information that gives an idea of the situation as a whole. Try not to overwhelm your child by giving too much at once. Have a few short conversations. Many children may find it difficult to absorb too many details.

Over time, you will be able to say more. Watch the child's reaction. If he changes the subject or gets distracted, it's probably enough for him for now. Pause so your child can ask questions and participate in the conversation. The opportunity to ask questions is a great way for your child to show that he needs more information, and for you to understand what exactly he wants to know.

Over time, you will be able to say more. Watch the child's reaction. If he changes the subject or gets distracted, it's probably enough for him for now. Pause so your child can ask questions and participate in the conversation. The opportunity to ask questions is a great way for your child to show that he needs more information, and for you to understand what exactly he wants to know. - Help to understand the basic facts about the disease, treatment and what to expect.

- Explain common terms the child will hear regularly, such as cancer , tumor , chemotherapy and side effects .

- Encourage the desire to share your feelings and ask questions. Answering your child's questions and having honest conversations can help them deal with the situation.

- Remember that sometimes children are afraid to ask questions. Watch their reactions in different situations. For example, if a child gets upset when he sees another child without hair, ask him how he feels and if there is anything he wants to know.

- Confirm correct information and correct incorrect information. The child may have already formed ideas about cancer from what they saw on TV or heard from relatives or friends before the diagnosis. Ask him what he already knows about cancer.

- Express hope. Doctors will help him fight cancer. There are many cancer treatments that you can try.

- Don't forget other children in the family. Remember that they need explanations too.

Typical reactions of children when they learn about cancer

All children are different. Children's reactions and how they perceive a cancer diagnosis depend on age, developmental level and personality traits.

- Some children react violently, crying or outbursts of anger.

- Others may become unusually quiet.

- Some express their feelings in words, others in actions.

- Some children begin to act like they did at a younger age.

- Every day will not be the same as the previous one.

The daily routine of the child, appearance and well-being, friendships can change.

The daily routine of the child, appearance and well-being, friendships can change. - Some days will be hard, others will be calmer.

Children will follow your example. Try to remain calm and confident. Find ways to tell and show your children (including siblings of a sick child) that you will always support them.

Common fears and misconceptions about cancer

There are several common fears that many children have when they learn about cancer. The child may be afraid to talk about them. Perhaps you yourself will touch them in a conversation. Start with phrases such as: Some children think... , Have you heard...?... ?

- Delusion 1. It's my fault. Young children often believe that cancer was caused by something they said, did, or thought was bad. Reassure the child that nothing he did, said, or thought caused cancer. Cancer is not a punishment.

- Misconception 2. Cancer is contagious. Explain to your child that people cannot "catch" cancer from another person.

Given the age of the child, tell him about the cancer.

Given the age of the child, tell him about the cancer. - Fallacy 3. Everyone dies of cancer. You can explain that cancer is a serious disease, but millions of people survive from it. If the children know that someone has died of cancer, say that there are different types of cancer. Each case is unique, different types of cancer have different names, and different types of cancer require different drugs to treat. This may need to be repeated several times during the course of treatment.

When encouraging your child to share their feelings and ask questions, be open and honest about your own feelings and questions.

You can be your child's most important source of information and support.

-

Modified June 2018

Talking to your child about cancer

Remember three principles when talking to your child about cancer:

- Be honest and open.

- Use words that the child can understand to describe illness and treatment.

- Provide details appropriate to the child's age and developmental level.

-

Child friendly definitions

-

Age-appropriate information

A sick child needs to know that he is loved, supported and surrounded by people who care for him.

The Importance of Honesty and Openness

Being honest and open with your child will help build trust and strengthen your relationship. You may want to hide from your child that he has cancer, or try to protect him from negative information. To seek to protect children from something unpleasant is a natural desire.

However, children are very observant. Even if they don't seem to be paying attention, they watch their parents, doctors, and other family members or adults to find out what's going on. It is highly likely that during treatment, the child will hear the word cancer (from staff, another child in the hospital, or even from relatives and friends), even if you have asked people not to say it. Many parents say that it is easier to explain a situation to a child than to prevent other people from talking about it. An explanation can relieve the tension that comes with constantly trying to hush up a situation.

Many parents say that it is easier to explain a situation to a child than to prevent other people from talking about it. An explanation can relieve the tension that comes with constantly trying to hush up a situation.

- Choosing to communicate openly is important for a number of reasons: even young children can feel that something is wrong. If you don't tell your child what's going on, he's more likely to make assumptions or use his imagination. Often what they imagine turns out to be worse than the truth.

- Children tend to blame themselves when something bad happens to them. They should know that they are not to blame for their illness.

- The more the child understands, the less frightening the situation seems to him. Children are usually more willing to accept treatment if they know how it can help them.

- Honesty will help reduce the child's anxiety, embarrassment and guilt due to misunderstanding of the situation.

Plan what and how to say

Speak in advance what you are going to tell the child. Seek advice from doctors or another parent who has been in a similar situation.

Seek advice from doctors or another parent who has been in a similar situation.

The way information is exchanged is also important. The child will understand a lot by the tone of your voice and facial expression. Remain calm when talking to your child. If you can't hold back your tears, don't be upset - this is normal, explain why you are crying. You might say that it's natural for parents to feel sad when their child is sick, or that people can get upset when their life changes so much. Tears are a way of expressing emotions. It is important for children to be sure that cancer is not the result of their actions and that people get upset through no fault of their own.

It is important how you talk to your child about the diagnosis. Remain calm while talking.

Decide who and when will tell the child

Many parents learn the diagnosis from the doctor at the same moment when the child learns it too. However, if you want to share this information with your child, the treatment team can help you decide what to say and how to answer questions.

Tell the child as soon as possible. This will help build trust.

Consider asking another person to be with you during the first conversation. It could be another family member or close friend who can be supportive. Or it could be a doctor, nurse, child adjustment specialist, or social worker who can describe the illness in more detail.

What to tell your child about cancer

The basic questions for most children and adolescents are the same:

- What is cancer?

- Why did I have it?

- Will I get better?

- What will happen now?

- When can we return home?

- What about school?

Children need information to endure procedures, cope with feelings, and stay in control of situations. Most of all, they need to know that they are loved, supported and surrounded by people who care about them.

Trust your instincts. You know your child better than anyone else. You know the best way to talk to him. Here are some helpful tips.

Here are some helpful tips.

- Consider the child's age. You may need to talk to the child adaptation specialists at the oncology center. They understand child development. They can help you describe the illness in age-appropriate terms and, given the child's stage of development, help him or her accept the information. They can explain concepts through therapeutic play and visual aids. In addition, social workers, psychologists and priests can provide support.

- Think carefully about how many details you want to share in one conversation. As a rule, it is recommended to start with general information that gives an idea of the situation as a whole. Try not to overwhelm your child by giving too much at once. Have a few short conversations. Many children may find it difficult to absorb too many details. Over time, you will be able to say more. Watch the child's reaction. If he changes the subject or gets distracted, it's probably enough for him for now. Pause so your child can ask questions and participate in the conversation.

The opportunity to ask questions is a great way for your child to show that he needs more information, and for you to understand what exactly he wants to know.

The opportunity to ask questions is a great way for your child to show that he needs more information, and for you to understand what exactly he wants to know. - Help to understand the basic facts about the disease, treatment and what to expect.

- Explain common terms the child will hear regularly, such as cancer , tumor , chemotherapy and side effects .

- Encourage the desire to share your feelings and ask questions. Answering your child's questions and having honest conversations can help them deal with the situation.

- Remember that sometimes children are afraid to ask questions. Watch their reactions in different situations. For example, if a child gets upset when he sees another child without hair, ask him how he feels and if there is anything he wants to know.

- Confirm correct information and correct incorrect information. The child may have already formed ideas about cancer from what they saw on TV or heard from relatives or friends before the diagnosis.

Ask him what he already knows about cancer.

Ask him what he already knows about cancer. - Express hope. Doctors will help him fight cancer. There are many cancer treatments that you can try.

- Don't forget other children in the family. Remember that they need explanations too.

Typical reactions of children when they learn about cancer

All children are different. Children's reactions and how they perceive a cancer diagnosis depend on age, developmental level and personality traits.

- Some children react violently, crying or outbursts of anger.

- Others may become unusually quiet.

- Some express their feelings in words, others in actions.

- Some children begin to act like they did at a younger age.

- Every day will not be the same as the previous one. The daily routine of the child, appearance and well-being, friendships can change.

- Some days will be hard, others will be calmer.

Children will follow your example. Try to remain calm and confident. Find ways to tell and show your children (including siblings of a sick child) that you will always support them.

Try to remain calm and confident. Find ways to tell and show your children (including siblings of a sick child) that you will always support them.

Common fears and misconceptions about cancer

There are several common fears that many children have when they learn about cancer. The child may be afraid to talk about them. Perhaps you yourself will touch them in a conversation. Start with phrases such as: Some children think... , Have you heard...?... ?

- Delusion 1. It's my fault. Young children often believe that cancer was caused by something they said, did, or thought was bad. Reassure the child that nothing he did, said, or thought caused cancer. Cancer is not a punishment.

- Misconception 2. Cancer is contagious. Explain to your child that people cannot "catch" cancer from another person. Given the age of the child, tell him about the cancer.

- Fallacy 3. Everyone dies of cancer. You can explain that cancer is a serious disease, but millions of people survive from it.